Submitted:

29 May 2025

Posted:

30 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

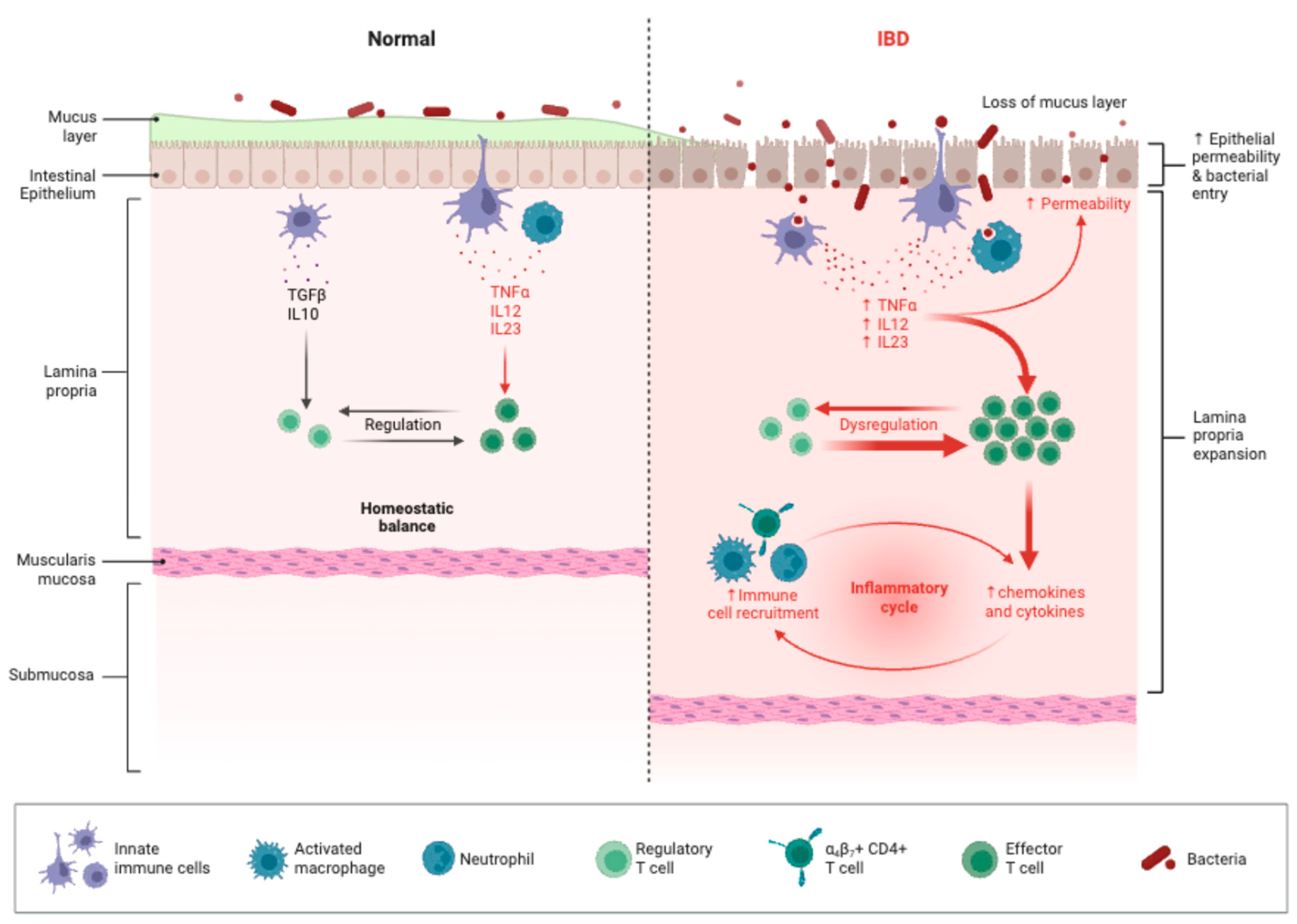

Pathophysiology of IBD and Dietary Interactions

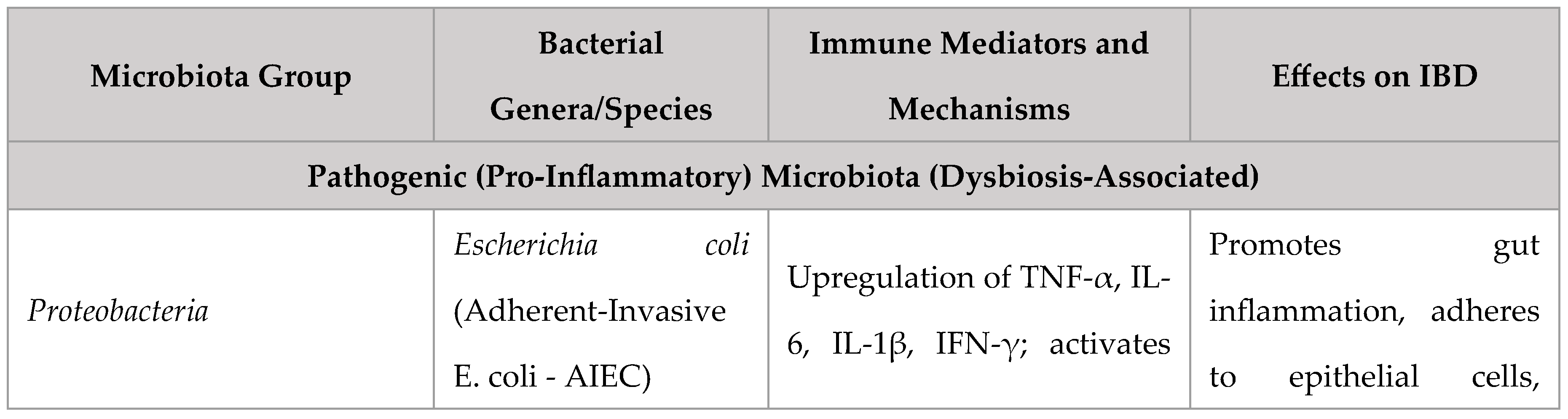

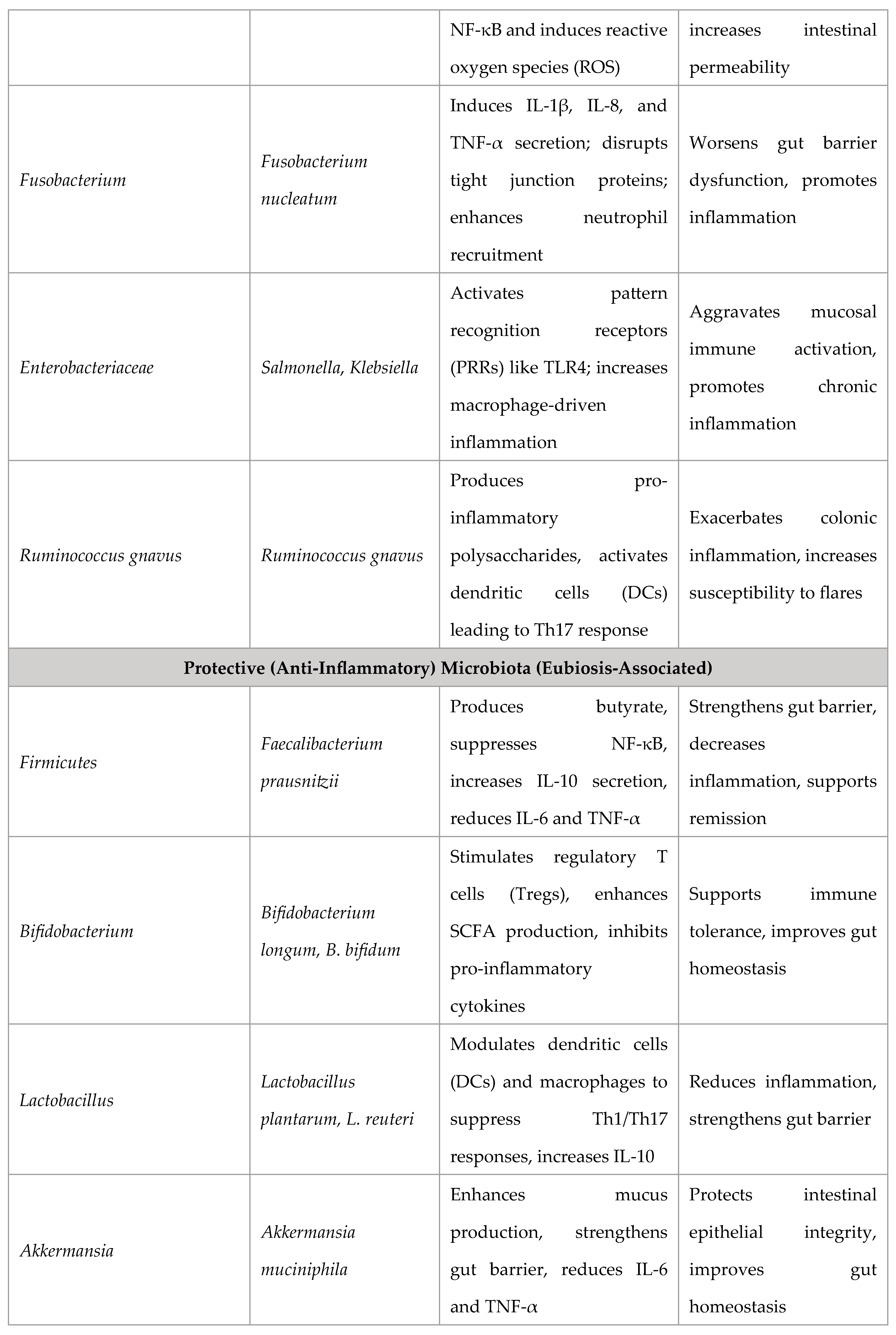

Role of Gut Microbiota and Dysbiosis

Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction and Immune Activation

Impact of Diet on Inflammatory Pathways

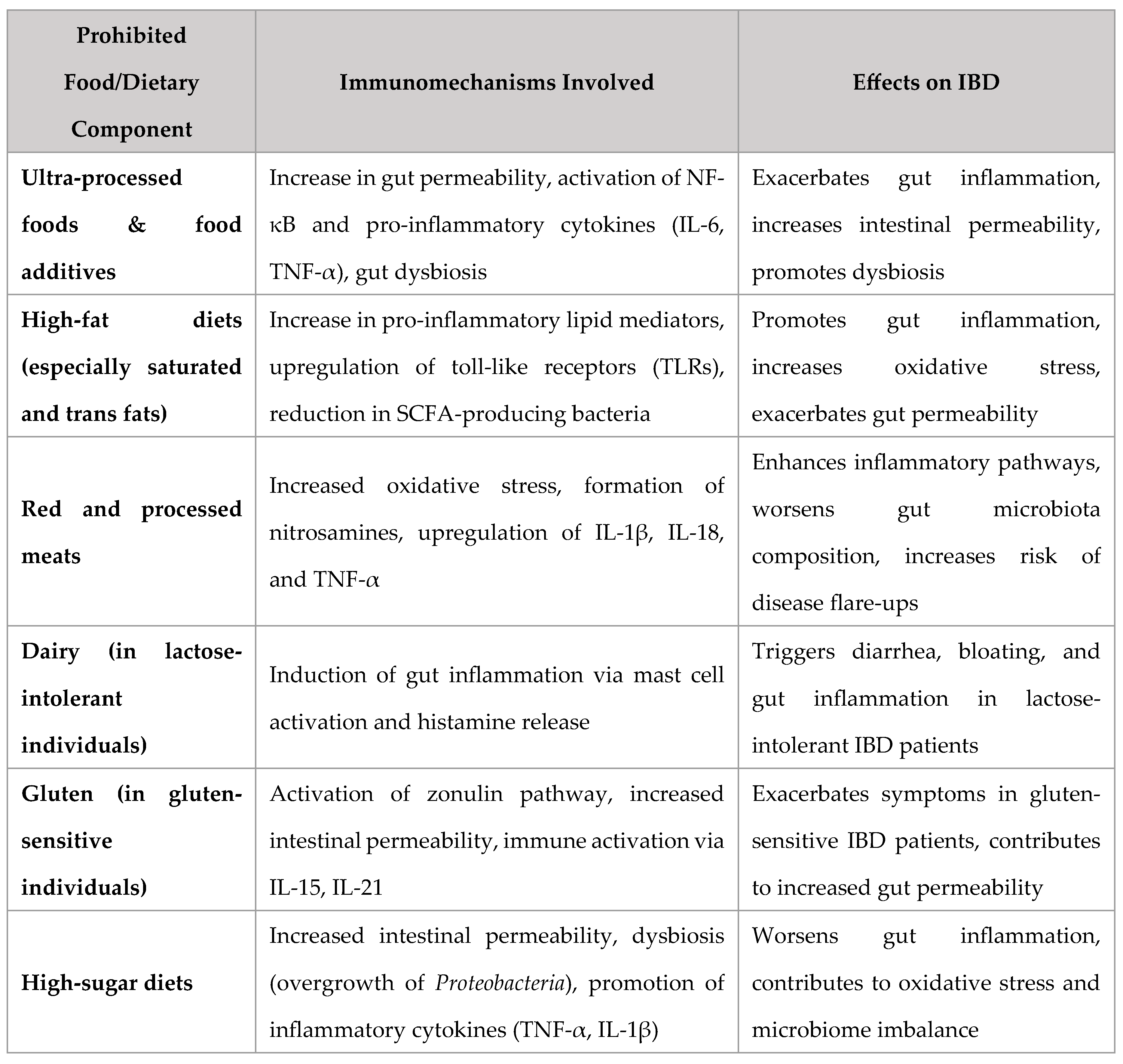

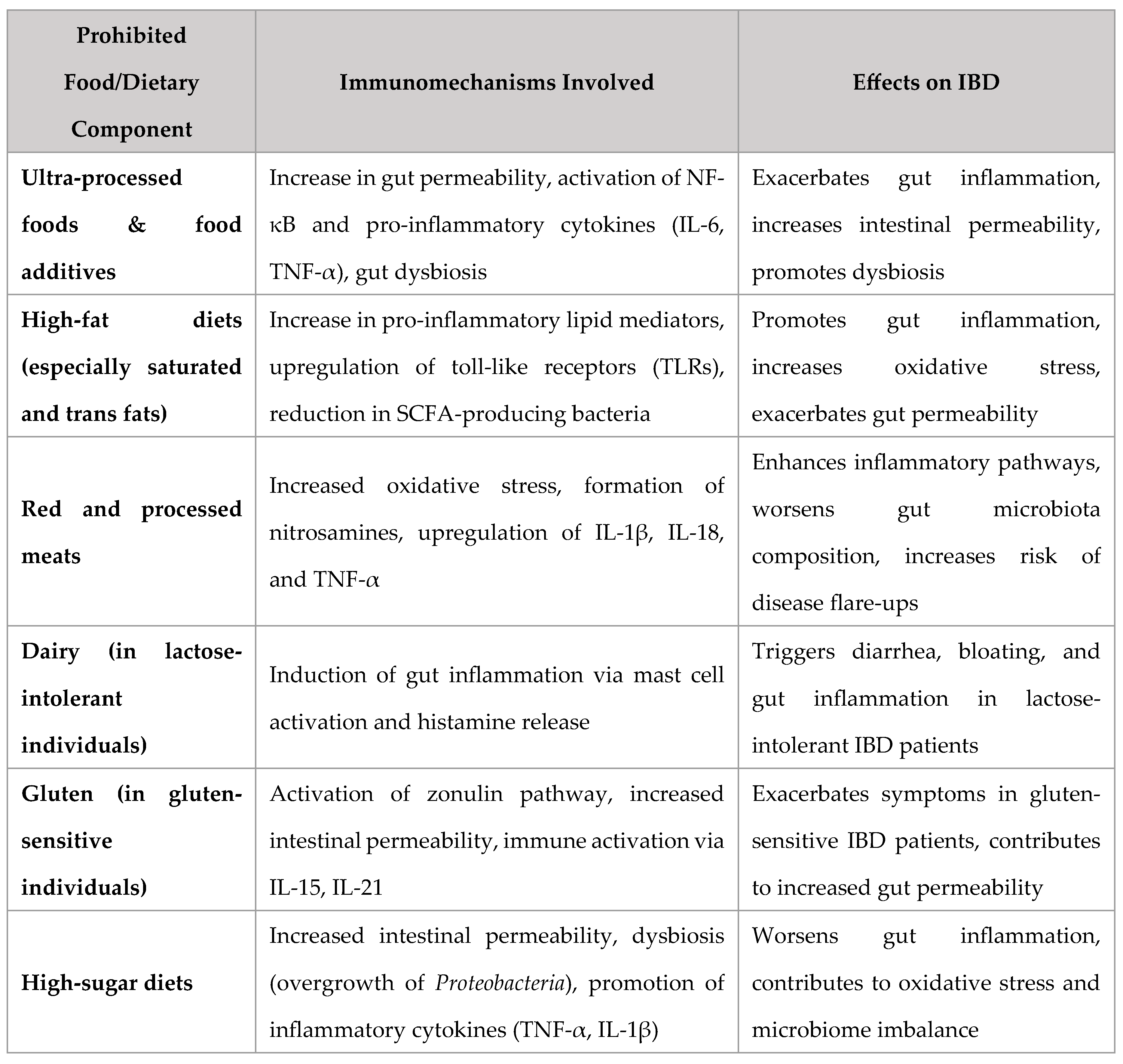

Foods to Avoid in IBD: Mechanistic and Clinical Evidence

Ultra-Processed Foods & Additives

High-Fat Diets

Red and Processed Meats

Dairy in Lactose-Intolerant Patients

Gluten in Sensitive Individuals

Foods Beneficial for IBD: Mechanistic and Clinical Evidence

Fiber & Prebiotics

Probiotics & Fermented Foods

Omega-3 Fatty Acids

Curcumin & Polyphenols

Exclusive Enteral Nutrition (EEN) in Crohn’s Disease

Commonly Asked Questions

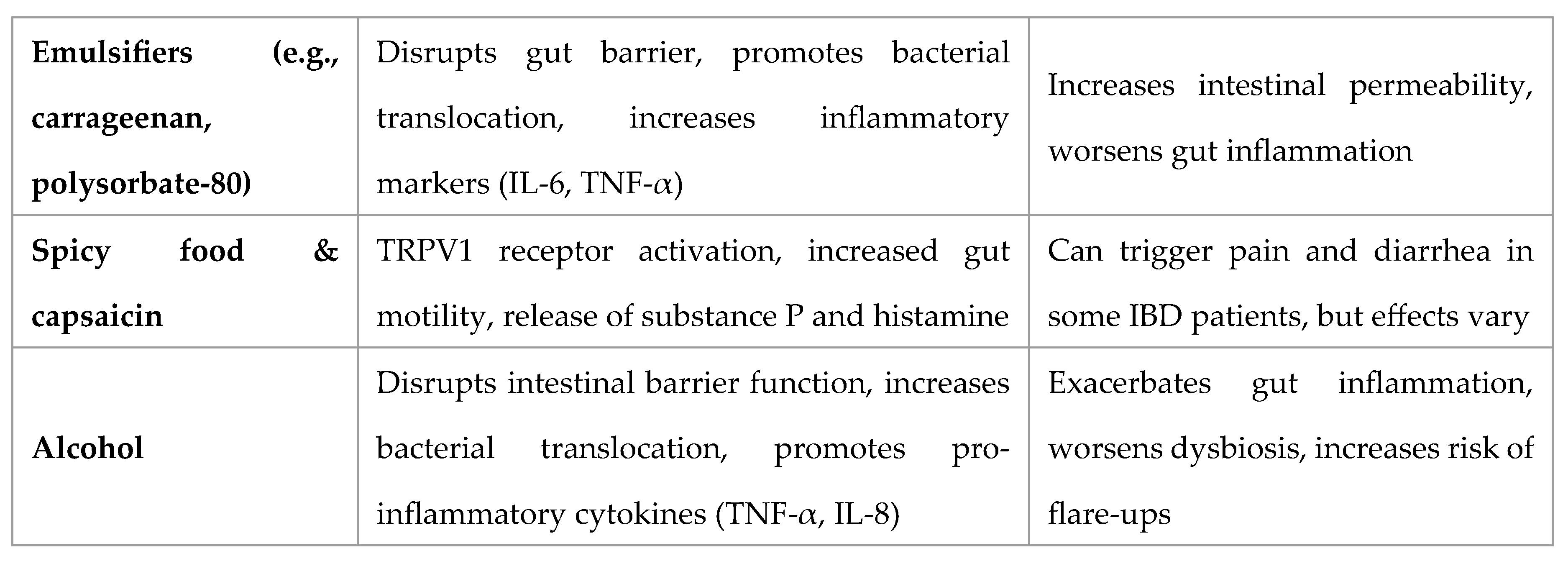

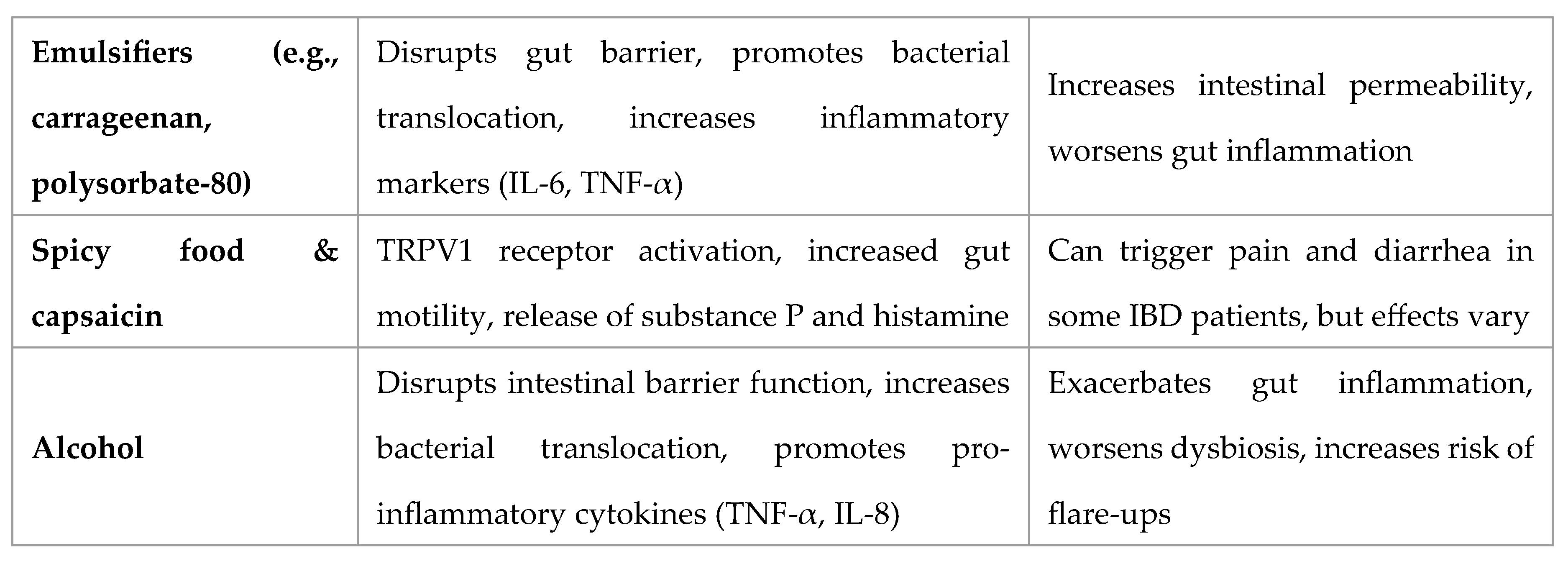

Spicy Food and Capsaicin in IBD

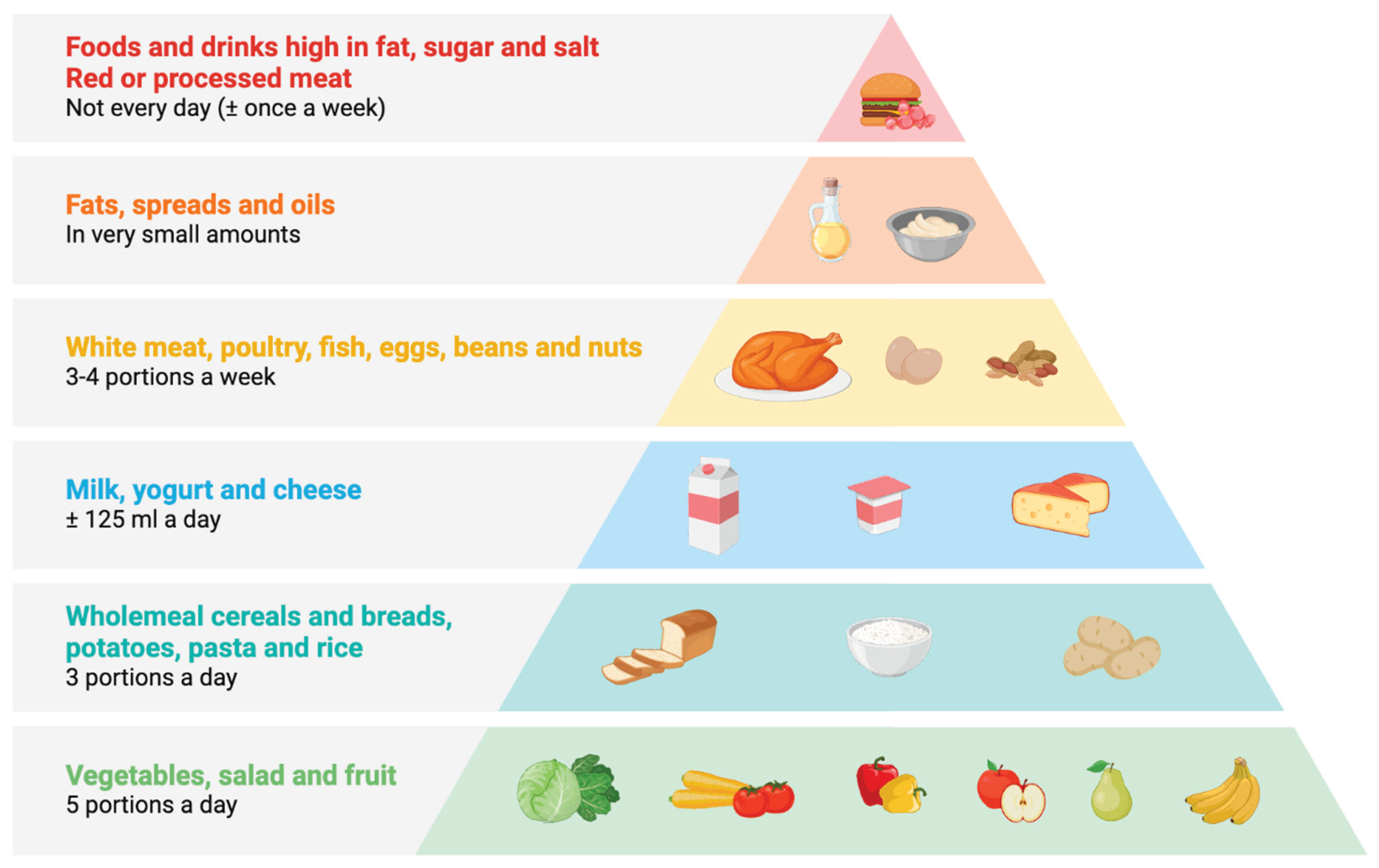

Portion Size and Meal Composition in IBD

Asian Diet, MSG, and Flavor Enhancers in IBD

Vitamins and Minerals in IBD

Types of Dairy Safe in IBD

Special Considerations and Emerging Research

Personalized Nutrition Approaches

Role of Elimination Diets

Ketogenic Diet and IBD

Intermittent Fasting and IBD

Ramadan Fasting and IBD

Future Directions in Dietary Intervention Trials

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Younge, L. An Overview of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nursing Standard 2019, 34, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumgart, D.C. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2009, 106, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianco, A.M.; Girardelli, M.; Tommasini, A. Genetics of Inflammatory Bowel Disease from Multifactorial to Monogenic Forms. World J Gastroenterol 2015, 21, 12296–12310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M’Koma, A.E. The Multifactorial Etiopathogeneses Interplay of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: An Overview. Gastrointestinal Disorders 2019, 1, 75–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight-Sepulveda, K.; Kais, S.; Santaolalla, R.; Abreu, M.T. Diet and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2015, 11, 511–520. [Google Scholar]

- Issokson, K.; Lee, D.Y.; Yarur, A.J.; Lewis, J.D.; Suskind, D.L. The Role of Diet in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Onset, Disease Management, and Surgical Optimization. Am J Gastroenterol 2025, 120, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, P.; Feagins, L.A. Dining With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Review of the Literature on Diet in the Pathogenesis and Management of IBD. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 2019, izz268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, P.; Kedia, S.; Ahuja, V.; Tandon, R.K. Diet and Nutrition in the Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Indian J Gastroenterol 2021, 40, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castro, M.M.; Pascoal, L.B.; Steigleder, K.M.; Siqueira, B.P.; Corona, L.P.; Ayrizono, M.D.L.S.; Milanski, M.; Leal, R.F. Role of Diet and Nutrition in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. WJEM 2021, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manski, S.; Noverati, N.; Policarpo, T.; Rubin, E.; Shivashankar, R. Diet and Nutrition in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Review of the Literature. Crohn’s & Colitis 360 2024, 6, otad077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghamdi, K.M.A.; Alrahma, H.A.; Alkanhal, F.A.; Alhamazani, F.T.; Aloraini, E.S.; Alqadiri, N.G.; Alhawsawi, M.Z.; Thabet, A.A.; Ajzaji, R.J.; Nasser, J.S.; et al. The Critical Role of Diet and Nutrition in Managing Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Int J Community Med Public Health 2023, 10, 5004–5008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutanto, H.; Elisa, E.; Rachma, B.; Fetarayani, D. Gut Microbiome Modulation in Allergy Treatment: The Role of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation. The American Journal of Medicine 2025, 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, R.; Shiva, Km.; Singh, R.; Sherawat, K.S.; Bhardwaj, P. Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis: Current Understanding and Future Direction. JBPR 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, A.; Inoue, R.; Inatomi, O.; Bamba, S.; Naito, Y.; Andoh, A. Gut Microbiota in the Pathogenesis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin J Gastroenterol 2018, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.O. Gut Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr 2013, 16, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haneishi, Y.; Furuya, Y.; Hasegawa, M.; Picarelli, A.; Rossi, M.; Miyamoto, J. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases and Gut Microbiota. IJMS 2023, 24, 3817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, H.; Rubab Ahmad; Sawar, M.U.N.; Ahmad, A.; Hareera; Khan, I. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Mechanisms, Therapeutic Targets, and Future Directions. IRABCS 2024, 2, 85–90. [CrossRef]

- Lavelle, A.; Sokol, H. The Gut Microbiome in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. In Molecular Genetics of Inflammatory Bowel Disease; Hedin, C., Rioux, J.D., D’Amato, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 347–377. ISBN 978-3-030-28702-3. [Google Scholar]

- McGuckin, M.A.; Eri, R.; Simms, L.A.; Florin, T.H.J.; Radford-Smith, G. Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 2009, 15, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Shen, L.; Clayburgh, D.R.; Nalle, S.C.; Sullivan, E.A.; Meddings, J.B.; Abraham, C.; Turner, J.R. Targeted Epithelial Tight Junction Dysfunction Causes Immune Activation and Contributes to Development of Experimental Colitis. Gastroenterology 2009, 136, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hering, N.A.; Fromm, M.; Schulzke, J. Determinants of Colonic Barrier Function in Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Potential Therapeutics. The Journal of Physiology 2012, 590, 1035–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, A.; Zhao, A.; Erickson, S.L.; Mukherjee, S.; Lau, A.J.; Alston, L.; Chang, T.K.H.; Mani, S.; Hirota, S.A. Pregnane X Receptor Activation Attenuates Inflammation-Associated Intestinal Epithelial Barrier Dysfunction by Inhibiting Cytokine-Induced Myosin Light-Chain Kinase Expression and c-Jun N-Terminal Kinase 1/2 Activation. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 2016, 359, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albenberg, L.G.; Lewis, J.D.; Wu, G.D. Food and the Gut Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Critical Connection. Current Opinion in Gastroenterology 2012, 28, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruemmele, F.M. Role of Diet in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Ann Nutr Metab 2016, 68, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman-Kiddell, C.A.; Davies, P.S.W.; Gillen, L.; Radford-Smith, G.L. Role of Diet in the Development of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 2010, 16, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugihara, K.; Morhardt, T.L.; Kamada, N. The Role of Dietary Nutrients in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front. Immunol. 2019, 9, 3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.K.; Lee, D.; Lewis, J. Diet and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Review of Patient-Targeted Recommendations. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2014, 12, 1592–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olednzki, B.; Bucci, V.; Cawley, C.; Maldonado-Contreras, A. A WHOLE FOOD, ANTI-INFLAMMATORY DIET ESTABLISHES A BENEFICIAL GUT MICROBIOME IN INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE PATIENTS. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, S51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godala, M.; Gaszyńska, E.; Zatorski, H.; Małecka-Wojciesko, E. Dietary Interventions in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, R.; Baldassano, R.N. Dietary Therapies for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. In Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease; Mamula, P., Grossman, A.B., Baldassano, R.N., Kelsen, J.R., Markowitz, J.E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; pp. 473–483. ISBN 978-3-319-49213-1. [Google Scholar]

- Calder, P.C. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Inflammatory Processes: Nutrition or Pharmacology? Br J Clin Pharmacol 2013, 75, 645–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marion-Letellier, R.; Amamou, A.; Savoye, G.; Ghosh, S. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases and Food Additives: To Add Fuel on the Flames! Nutrients 2019, 11, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedelha Sabino, J. OP33 Mechanistic Insights on the Role of Ultra Processed Foods as a Trigger/Fuel for IBD. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis 2024, 18, i59–i59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoul, P.; Cintoni, M.; Palombaro, M.; Basso, L.; Rinninella, E.; Gasbarrini, A.; Mele, M.C. Food Additives, a Key Environmental Factor in the Development of IBD through Gut Dysbiosis. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narula, N.; Wong, E.C.L.; Dehghan, M.; Mente, A.; Rangarajan, S.; Lanas, F.; Lopez-Jaramillo, P.; Rohatgi, P.; Lakshmi, P.V.M.; Varma, R.P.; et al. Association of Ultra-Processed Food Intake with Risk of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Prospective Cohort Study. BMJ 2021, n1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarbagili-Shabat, C.; Zelber-Sagi, S.; Isakov, N.F.; Hirsch, A.; Ron, Y.; Grinshpan, L.S.; Anbar, R.; Bromberg, A.; Thurm, T.; Maharshak, N. Ultra-Processed Foods Consumption Is Positively Associated with the Clinical Activity of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Cross-Sectional Single-Center Study. Inflamm Intest Dis 2024, 9, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaei, A.; Pourmotabbed, A.; Talebi, S.; Mehrabani, S.; Bagheri, R.; Ghoreishy, S.M.; Amirian, P.; Zarpoosh, M.; Mohammadi, H.; Kermani, M.A.H.; et al. The Association of Ultra-Processed Food Consumption with Adult Inflammatory Bowel Disease Risk: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of 4 035 694 Participants. Nutrition Reviews 2024, 82, 861–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Y.; Ma, C.; Chen, K.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, M.; Hu, K.; Li, L.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, H. The Effects of a High-Fat Diet on Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natividad, J.M.; Lamas, B.; Pham, H.P.; Michel, M.-L.; Rainteau, D.; Bridonneau, C.; da Costa, G.; van Hylckama Vlieg, J.; Sovran, B.; Chamignon, C.; et al. Bilophila Wadsworthia Aggravates High Fat Diet Induced Metabolic Dysfunctions in Mice. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik, J.; Fierce, Y.; Treuting, P.M.; Brabb, T.; Maggio-Price, L. High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity Exacerbates Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Genetically Susceptible Mdr1a Male Mice. The Journal of Nutrition 2013, 143, 1240–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wei, X.; Sun, Y.; Du, J.; Li, X.; Xun, Z.; Li, Y.C. High-Fat Diet Promotes Experimental Colitis by Inducing Oxidative Stress in the Colon. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 2019, 317, G453–G462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Dong, R.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Yu, M.; Li, X.; Wang, J. Multiomics Analysis Reveals the Potential Mechanism of High-fat Diet in Dextran Sulfate Sodium-induced Colitis Mice Model. Food Science & Nutrition 2024, 12, 8309–8323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.-H.; Yang, J.; Chen, L.; Du, C.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, S.-S.; Wang, X.-Y.; Yang, J.; Liu, Y.; Cai, D.; et al. Short-Term High-Fat Diet Fuels Colitis Progression in Mice Associated With Changes in Blood Metabolome and Intestinal Gene Expression. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 899829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, C.; Chan, S.S.M.; Jantchou, P.; Racine, A.; Oldenburg, B.; Weiderpass, E.; Heath, A.K.; Tong, T.Y.N.; Tjønneland, A.; Kyrø, C.; et al. Meat Intake Is Associated with a Higher Risk of Ulcerative Colitis in a Large European Prospective Cohort Studyø. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis 2022, 16, 1187–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Cui, M.; Tan, F.; Liu, X.; Yao, P. High Red Meat Intake Exacerbates Dextran Sulfate-Induced Colitis by Altering Gut Microbiota in Mice. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 646819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Fu, T.; Dan, L.; Chen, X.; Sun, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Hesketh, T. P003 Meat Consumption and All-Cause Mortality in 5763 Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients: A Prospective Cohort Study. Am J Gastroenterol 2021, 116, S1–S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albenberg, L.; Brensinger, C.M.; Wu, Q.; Gilroy, E.; Kappelman, M.D.; Sandler, R.S.; Lewis, J.D. A Diet Low in Red and Processed Meat Does Not Reduce Rate of Crohn’s Disease Flares. Gastroenterology 2019, 157, 128–136.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishkin, S. Dairy Sensitivity, Lactose Malabsorption, and Elimination Diets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 1997, 65, 564–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfari, M.M.; Sarmini, M.T.; Kendrick, K.; Hudgi, A.; Uy, P.; Sridhar, S.; Sifuentes, H. Association between Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Lactose Intolerance: Fact or Fiction. Korean J Gastroenterol 2020, 76, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardone, O.M.; Manfellotto, F.; D’Onofrio, C.; Rocco, A.; Annona, G.; Sasso, F.; De Luca, P.; Imperatore, N.; Testa, A.; De Sire, R.; et al. Lactose Intolerance Assessed by Analysis of Genetic Polymorphism, Breath Test and Symptoms in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishkin, S. Controversies Regarding the Role of Dairy Products in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology 1994, 8, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavinejad, P.; Nayebi, M.; Parsi, A.; Farsi, F.; Maghool, F.; Alipour, Z.; Alimadadi, M.; Ahmed, M.H.; Cheraghian, B.; Hang, D.V.; et al. IS DAIRY FOODS RESTRICTION MANDATORY FOR INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE PATIENTS: A MULTINATIONAL CROSS-SECTIONAL STUDY. Arq. Gastroenterol. 2022, 59, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szilagyi, A.; Galiatsatos, P.; Xue, X. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Lactose Digestion, Its Impact on Intolerance and Nutritional Effects of Dairy Food Restriction in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Nutr J 2015, 15, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almofarreh, A.M.; Sheerah, H.A.; Arafa, A.; Al Mubarak, A.S.; Ali, A.M.; Al-Otaibi, N.M.; Alzahrani, M.A.; Aljubayl, A.R.; Aleid, M.A.; Alhamed, S.S. Dairy Consumption and Inflammatory Bowel Disease among Arab Adults: A Case–Control Study and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casella, G.; Di Bella, C.; Salemme, M.; Villanacci, V.; Antonelli, E.; Baldini, V.; Bassotti, G. Celiac Disease, Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol 2015, 61, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Potter, M.D.; Walker, M.M.; Jones, M.P.; Koloski, N.A.; Keely, S.; Talley, N.J. Letter: Gluten Sensitivity in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018, 48, 1167–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, K.N.; Herfarth, H. Gluten-Free Diet in IBD: Time for a Recommendation? Molecular Nutrition Food Res 2021, 65, 1901274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limketkai, B.N.; Sepulveda, R.; Hing, T.; Shah, N.D.; Choe, M.; Limsui, D.; Shah, S. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Gluten Sensitivity in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology 2018, 53, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herfarth, H.H.; Martin, C.F.; Sandler, R.S.; Kappelman, M.D.; Long, M.D. Prevalence of a Gluten-Free Diet and Improvement of Clinical Symptoms in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 2014, 20, 1194–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, E.W.; Lebwohl, B.; Burke, K.E.; Ivey, K.L.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Lochhead, P.; Richter, J.M.; Ludvigsson, J.F.; Willett, W.C.; Chan, A.T.; et al. Dietary Gluten Intake Is Not Associated With Risk of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in US Adults Without Celiac Disease. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2022, 20, 303–313.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.; Harris, P.; Ferguson, L. Potential Benefits of Dietary Fibre Intervention in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. IJMS 2016, 17, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.K.; Macia, L.; Mackay, C.R. Dietary Fiber and SCFAs in the Regulation of Mucosal Immunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2023, 151, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferenc, K.; Jarmakiewicz-Czaja, S.; Filip, R. Components of the Fiber Diet in the Prevention and Treatment of IBD—An Update. Nutrients 2022, 15, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healey, G.R.; Celiberto, L.S.; Lee, S.M.; Jacobson, K. Fiber and Prebiotic Interventions in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease: What Role Does the Gut Microbiome Play? Nutrients 2020, 12, 3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, R.; Day, A.; Barrett, J.; Vanlint, A.; Andrews, J.M.; Costello, S.P.; Bryant, R.V. Habitual Dietary Fibre and Prebiotic Intake Is Inadequate in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Findings from a Multicentre Cross-sectional Study. J Human Nutrition Diet 2021, 34, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silveira, A.L.M.; Ferreira, A.V.M.; De Oliveira, M.C.; Rachid, M.A.; Da Cunha Sousa, L.F.; Dos Santos Martins, F.; Gomes-Santos, A.C.; Vieira, A.T.; Teixeira, M.M. Preventive Rather than Therapeutic Treatment with High Fiber Diet Attenuates Clinical and Inflammatory Markers of Acute and Chronic DSS-Induced Colitis in Mice. Eur J Nutr 2017, 56, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puvvada, S.R.; Luvsannyam, E.; Patel, D.; Hassan, Z.; Hamid, P. Probiotics in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Are We Back to Square One? Cureus 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prisciandaro, L.; Geier, M.; Butler, R.; Cummins, A.; Howarth, G. Probiotics and Their Derivatives as Treatments for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 2009, 15, 1906–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Chen, Z.; Liu, N.; Xia, C.; Zhou, Q.; Li, P. Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum ZJ316–Fermented Milk Ameliorates Dextran Sulfate Sodium–Induced Chronic Colitis by Improving the Inflammatory Response and Regulating Intestinal Microbiota. Journal of Dairy Science 2023, 106, 7352–7366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristofori, F.; Dargenio, V.N.; Dargenio, C.; Miniello, V.L.; Barone, M.; Francavilla, R. Anti-Inflammatory and Immunomodulatory Effects of Probiotics in Gut Inflammation: A Door to the Body. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 578386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbazi, R.; Sharifzad, F.; Bagheri, R.; Alsadi, N.; Yasavoli-Sharahi, H.; Matar, C. Anti-Inflammatory and Immunomodulatory Properties of Fermented Plant Foods. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saez-Lara, M.J.; Gomez-Llorente, C.; Plaza-Diaz, J.; Gil, A. The Role of Probiotic Lactic Acid Bacteria and Bifidobacteria in the Prevention and Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Other Related Diseases: A Systematic Review of Randomized Human Clinical Trials. Biomed Res Int 2015, 2015, 505878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolova, D. Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Diet: Is There a Place for Probiotics? Galenika Med J 2023, 2, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akutko, K.; Stawarski, A. Probiotics, Prebiotics and Synbiotics in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. JCM 2021, 10, 2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, G.; Sorrentino Dos Santos Campanari, G.; Barbalho, S.M.; Matias, J.N.; Lima, V.M.; Araújo, A.C.; Goulart, R.D.A.; Detregiachi, C.R.P.; Santos Haber, J.F.; Alves De Carvalho, A.C.; et al. Effects of Probiotics on Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review. Japanese J Gastroenterol Res 2021, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marton, L.T.; Goulart, R.D.A.; Carvalho, A.C.A.D.; Barbalho, S.M. Omega Fatty Acids and Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: An Overview. IJMS 2019, 20, 4851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbalho, S.M.; Goulart, R. de A.; Quesada, K.; Bechara, M.D.; de Carvalho, A. de C.A. Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Can Omega-3 Fatty Acids Really Help? Ann Gastroenterol 2016, 29, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Astore, C.; Nagpal, S.; Gibson, G. Mendelian Randomization Indicates a Causal Role for Omega-3 Fatty Acids in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. IJMS 2022, 23, 14380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajabnoor, S.M.; Thorpe, G.; Abdelhamid, A.; Hooper, L. Long-Term Effects of Increasing Omega-3, Omega-6 and Total Polyunsaturated Fats on Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Markers of Inflammation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Eur J Nutr 2021, 60, 2293–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrukh, A. Is There a Role for Fish Oil in Inflammatory Bowel Disease? WJC 2014, 2, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Luo, X.; Xin, H.; Lai, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Bai, Y. The Effects of Fatty Acids on Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Chai, C.; Chen, L.; Cai, M.; Ai, B.; Li, H.; Yuan, J.; Lin, H.; Zhang, Z. Associations of Fish and Fish Oil Consumption With Incident Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Population-Based Prospective Cohort Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2024, 30, 1812–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzaei, M.; Rahimi, R.; Abdollahi, M. The Role of Dietary Polyphenols in the Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. CPB 2015, 16, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanai, H.; Sugimoto, K. Curcumin Has Bright Prospects for the Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. CPD 2009, 15, 2087–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J.; Ye, X.; Huang, Z.; Jiang, S.; Lin, D. Curcumin@Fe/Tannic Acid Complex Nanoparticles for Inflammatory Bowel Disease Treatment. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 14316–14322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaghari-Tabari, M.; Alemi, F.; Zokaei, M.; Moein, S.; Qujeq, D.; Yousefi, B.; Farzami, P.; Hosseininasab, S.S. Polyphenols and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Natural Products with Therapeutic Effects? Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2024, 64, 4155–4178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Li, D.; Wang, X.; Cui, Y.; Li, X. Polyphenols Intervention Is an Effective Strategy to Ameliorate Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition 2021, 72, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nones, K.; Dommels, Y.E.M.; Martell, S.; Butts, C.; McNabb, W.C.; Park, Z.A.; Zhu, S.; Hedderley, D.; Barnett, M.P.G.; Roy, N.C. The Effects of Dietary Curcumin and Rutin on Colonic Inflammation and Gene Expression in Multidrug Resistance Gene-Deficient ( Mdr1a−/− ) Mice, a Model of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Br J Nutr 2008, 101, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, A.; Young, K.N.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Beyene, A.M.; Do, K.; Kalaiselvi, S.; Min, T. Curcumin and Its Modified Formulations on Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): The Story So Far and Future Outlook. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, J.J.; Gavin, J.; Beattie, R.M. Exclusive Enteral Nutrition in Crohn’s Disease: Evidence and Practicalities. Clinical Nutrition 2019, 38, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, B.; Curle, J.; Gervais, L.; Wands, D.; Nichols, B.; Hansen, R.; Russell, R.K.; Gerasimidis, K.; Milling, S. Exclusive Enteral Nutrition Impacts Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell Profile of Children with Crohn’s Disease. J. pediatr. gastroenterol. nutr. 2024, 79, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, B.; Curle, J.; Gervais, L.; Wands, D.; Nichols, B.; Hansen, R.; Russell, R.; Gerasmidis, K.; Milling, S. P976 Treatment with Exclusive Enteral Nutrition (EEN) Impacts the Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell Profile of Paediatric Patients with Crohn’s Disease. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis 2024, 18, i1769–i1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, A.; Wood, J.; Melton, S.; Bryant, R.V. Exclusive Enteral Nutrition: An Optimal Care Pathway for Use in Adult Patients with Active Crohn’s Disease. JGH Open 2020, 4, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutsekwa, R.N.; Edwards, J.T.; Angus, R.L. Exclusive Enteral Nutrition in the Management of Crohn’s Disease: A Qualitative Exploration of Experiences, Challenges and Enablers in Adult Patients. J Human Nutrition Diet 2021, 34, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.; Wu, R.; Zhu, W.; Gong, J.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; Gu, L.; Li, N.; Li, J. Effect of Exclusive Enteral Nutrition on Health-Related Quality of Life for Adults With Active Crohn’s Disease. Nut in Clin Prac 2013, 28, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wall, C.L.; McCombie, A.; Mulder, R.; Day, A.S.; Gearry, R.B. Adherence to Exclusive Enteral Nutrition by Adults with Active Crohn’s Disease Is Associated with Conscientiousness Personality Trait: A Sub-Study. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics 2020, 33, 752–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Torres, L.; Moreno-Álvarez, A.; Fernández-Lorenzo, A.E.; Leis, R.; Solar-Boga, A. The Role of Partial Enteral Nutrition for Induction of Remission in Crohn’s Disease: A Systematic Review of Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Wang, Z.; Mu, J.; Zhu, M.; Zhen, Y.; Zhang, H. Upregulation of the Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1 in Colonic Epithelium of Patients with Active Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2017, 10, 11335–11344. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhang, T.; Wu, X.; Fan, D.; Hu, Y.; Ding, J.; Yang, X.; Lou, J.; Du, Q.; et al. Beneficial Effects of Dietary Capsaicin in Gastrointestinal Health and Disease. Experimental Cell Research 2022, 417, 113227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ma, C.; Dang, Y.; Chen, K.; Shen, S.; Jiang, M.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, H. P082 Spicy Food Is a Vital Trigger for Relapse in Patient with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis 2020, 14, S176–S176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosca, A.E.; Iesanu, M.I.; Zahiu, C.D.M.; Voiculescu, S.E.; Paslaru, A.C.; Zagrean, A.-M. Capsaicin and Gut Microbiota in Health and Disease. Molecules 2020, 25, 5681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; An, N.; Ni, W.; Gao, Q.; Yu, Y. Capsaicin Affects Macrophage Anti-Inflammatory Activity via the MAPK and NF-κB Signaling Pathways. International Journal for Vitamin and Nutrition Research 2023, 93, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, J.; DiVincenzo, C.; Feagins, L.A. Optimizing Nutrition to Enhance the Treatment of Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2022, 18, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rondanelli, M.; Lamburghini, S.; Faliva, M.A.; Peroni, G.; Riva, A.; Allegrini, P.; Spadaccini, D.; Gasparri, C.; Iannello, G.; Infantino, V.; et al. A Food Pyramid, Based on a Review of the Emerging Literature, for Subjects with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Endocrinología, Diabetes y Nutrición 2021, 68, 17–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cucinotta, U.; Romano, C.; Dipasquale, V. Diet and Nutrition in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Nutrients 2021, 13, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugihara, K.; Kamada, N. Diet–Microbiota Interactions in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, D.; Shi, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhong, J.; Sun, J.; Gu, Y. Combined Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment and Body Composition Facilitates Nutritional Support in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: An Ambulatory Study in Shanghai. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2018, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, A.; Ahuja, V.; Kedia, S.; Midha, V.; Mahajan, R.; Mehta, V.; Sudhakar, R.; Singh, A.; Kumar, A.; Puri, A.S.; et al. Diet and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: The Asian Working Group Guidelines. Indian J Gastroenterol 2019, 38, 220–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Cheon, J.H. Incidence and Prevalence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease across Asia. Yonsei Med J 2021, 62, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijan, M.A.; Lim, B.O. Diets, Functional Foods, and Nutraceuticals as Alternative Therapies for Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Present Status and Future Trends. WJG 2018, 24, 2673–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooks, B.; Misra, R.; Arebi, N.; Kok, K.; Brookes, M.J.; McLaughlin, J.; Limdi, J.K. The Dietary Practices and Beliefs of British South Asian People Living with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Multicenter Study from the United Kingdom. Intest Res 2022, 20, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Li, T.; Wu, C.; Tao, L.; Blachier, F.; Yin, Y. Monosodium L-Glutamate and Dietary Fat Exert Opposite Effects on the Proximal and Distal Intestinal Health in Growing Pigs. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 40, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghishan, F.K.; Kiela, P.R. Vitamins and Minerals in IBD. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2017, 46, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parizadeh, S.M.; Jafarzadeh-Esfehani, R.; Hassanian, S.M.; Mottaghi-Moghaddam, A.; Ghazaghi, A.; Ghandehari, M.; Alizade-Noghani, M.; Khazaei, M.; Ghayour-Mobarhan, M.; Ferns, G.A.; et al. Vitamin D in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: From Biology to Clinical Implications. Complementary Therapies in Medicine 2019, 47, 102189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassan Mohammed, H.; Mirshafiey, A.; Vahedi, H.; Hemmasi, G.; Moussavi Nasl Khameneh, A.; Parastouei, K.; Saboor-Yaraghi, A.A. Immunoregulation of Inflammatory and Inhibitory Cytokines by Vitamin D3 in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology 2017, 85, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gold, S.L.; Manning, L.; Kohler, D.; Ungaro, R.; Sands, B.; Raman, M. Micronutrients and Their Role in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Function, Assessment, Supplementation, and Impact on Clinical Outcomes Including Muscle Health. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 2023, 29, 487–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhouri, R.H.; Hashmi, H.; Baker, R.D.; Gelfond, D.; Baker, S.S. Vitamin and Mineral Status in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. pediatr. gastroenterol. nutr. 2013, 56, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, S.; Iijima, H.; Egawa, S.; Shinzaki, S.; Kondo, J.; Inoue, T.; Hayashi, Y.; Ying, J.; Mukai, A.; Akasaka, T.; et al. Association of Vitamin K Deficiency with Bone Metabolism and Clinical Disease Activity in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nutrition 2011, 27, 1023–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laheij, R.L.H.; Van Knippenberg, Y.M.W.; Heil, A.L.J.; Mannaerts, B.J.W.; Bruin, K.F.; Lutgens, M.W.M.D.; Sikkema, M.; De Wit, U.; Laheij, R.J.F. The Efficacy of an Over-the-Counter Multivitamin and Mineral Supplement to Prevent Infections in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Remission With Immunomodulators and/or Biological Agents: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 2024, 30, 1510–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenley, R.N.; Stephens, K.A.; Nguyen, E.U.; Kunz, J.H.; Janas, L.; Goday, P.; Schurman, J.V. Vitamin and Mineral Supplement Adherence in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 2013, 38, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempinski, R.; Arabasz, D.; Neubauer, K. Effects of Milk and Dairy on the Risk and Course of Inflammatory Bowel Disease versus Patients’ Dietary Beliefs and Practices: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opstelten, J.L.; Leenders, M.; Dik, V.K.; Chan, S.S.M.; Van Schaik, F.D.M.; Khaw, K.-T.; Luben, R.; Hallmans, G.; Karling, P.; Lindgren, S.; et al. Dairy Products, Dietary Calcium, and Risk of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Results From a European Prospective Cohort Investigation. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 2016, 22, 1403–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, A.E.; Zawada, A.; Rychter, A.M.; Dobrowolska, A.; Krela-Kaźmierczak, I. Milk and Dairy Products: Good or Bad for Human Bone? Practical Dietary Recommendations for the Prevention and Management of Osteoporosis. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wellens, J.; Vissers, E.; Matthys, C.; Vermeire, S.; Sabino, J. Personalized Dietary Regimens for Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Current Knowledge and Future Perspectives. PGPM 2023, Volume 16, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, C.B.; Roche, H.M. Personalized Nutrition for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Crohn’s & Colitis 360 2020, 2, otaa042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Shimoyama, T. Nutrition and Diet in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Current Opinion in Gastroenterology 2023, 39, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarmakiewicz-Czaja, S.; Zielińska, M.; Sokal, A.; Filip, R. Genetic and Epigenetic Etiology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: An Update. Genes (Basel) 2022, 13, 2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, Z.; Hekmatdoost, A. Dietary Interventions and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. In Dietary Interventions in Gastrointestinal Diseases; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 33–42 ISBN 978-0-12-814468-8.

- Gleave, A.; Shah, A.; Tahir, U.; Blom, J.-J.; Dong, E.; Patel, A.; Marshall, J.K.; Narula, N. Using Diet to Treat Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review. Am J Gastroenterol 2025, 120, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakodkar, S.; Mutlu, E.A. Diet as a Therapeutic Option for Adult Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2017, 46, 745–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakodkar, S.; Farooqui, A.J.; Mikolaitis, S.L.; Mutlu, E.A. The Specific Carbohydrate Diet for Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Case Series. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 2015, 115, 1226–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, A.E.; Festa, S.; Aratari, A.; Papi, C.; Dobrowolska, A.; Krela-Kaźmierczak, I. Should the Mediterranean Diet Be Recommended for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases Patients? A Narrative Review. Front. Nutr. 2023, 9, 1088693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migdanis, A.; Migdanis, I.; Gkogkou, N.D.; Papadopoulou, S.K.; Giaginis, C.; Manouras, A.; Polyzou Konsta, M.A.; Kosti, R.I.; Oikonomou, K.A.; Argyriou, K.; et al. The Relationship of Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet with Disease Activity and Quality of Life in Crohn’s Disease Patients. Medicina (Kaunas) 2024, 60, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigall Boneh, R.; Assa, A.; Lev-Tzion, R.; Matar, M.; Shouval, D.; Shubeli, C.; Tsadok Perets, T.; Chodick, G.; Shamir, R. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet Is Associated with Decreased Fecal Calprotectin Levels in Children with Crohn’s Disease in Clinical Remission under Biological Therapy. Dig Dis 2024, 42, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, N.R.M.; McNichol, S.R.; Devine, B.; Phipps, A.I.; Roth, J.A.; Suskind, D.L. Assessing Barriers to Use of the Specific Carbohydrate Diet in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Qualitative Study. JPGN Rep 2022, 3, e239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Zhuge, A.; Wang, K.; Lv, L.; Bian, X.; Yang, L.; Xia, J.; Jiang, X.; Wu, W.; Wang, S.; et al. Ketogenic Diet Aggravates Colitis, Impairs Intestinal Barrier and Alters Gut Microbiota and Metabolism in DSS-Induced Mice. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 10210–10225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, C.; Yan, X.; Liu, Y.; Huang, L.; Zhu, Y.; He, J.; Gao, R.; Kalady, M.F.; Goel, A.; Qin, H.; et al. Ketogenic Diet Alleviates Colitis by Reduction of Colonic Group 3 Innate Lymphoid Cells through Altering Gut Microbiome. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2021, 6, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharairi, N.A. The Therapeutic Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids Mediated Very Low-Calorie Ketogenic Diet–Gut Microbiota Relationships in Paediatric Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norwitz, N.G.; Soto-Mota, A. Case Report: Carnivore–Ketogenic Diet for the Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Case Series of 10 Patients. Front Nutr 2024, 11, 1467475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luiskari, L.; Lindén, J.; Lehto, M.; Salmenkari, H.; Korpela, R. Ketogenic Diet Protects from Experimental Colitis in a Mouse Model Regardless of Dietary Fat Source. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavallee, C.M.; Bruno, A.; Ma, C.; Raman, M. A Review of the Role of Intermittent Fasting in the Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2023, 16, 17562848231171756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roco-Videla, Á.; Villota-Arcos, C.; Pino-Astorga, C.; Mendoza-Puga, D.; Bittner-Ortega, M.; Corbeaux-Ascui, T. Intermittent Fasting and Reduction of Inflammatory Response in a Patient with Ulcerative Colitis. Medicina 2023, 59, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangan, P.; Choi, I.; Wei, M.; Navarrete, G.; Guen, E.; Brandhorst, S.; Enyati, N.; Pasia, G.; Maesincee, D.; Ocon, V.; et al. Fasting-Mimicking Diet Modulates Microbiota and Promotes Intestinal Regeneration to Reduce Inflammatory Bowel Disease Pathology. Cell Reports 2019, 26, 2704–2719.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Bai, M.; Ling, Z.; Lin, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, Y. Intermittent Administration of a Fasting-Mimicking Diet Reduces Intestinal Inflammation and Promotes Repair to Ameliorate Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Mice. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 2021, 96, 108785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonsack, O.; Caron, B.; Baumann, C.; Heba, A.C.; Vieujean, S.; Arnone, D.; Netter, P.; Danese, S.; Quilliot, D.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Food Avoidance and Fasting in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Experience from the Nancy IBD Nutrition Clinic. UEG Journal 2023, 11, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavakkoli, H.; Haghdani, S.; Emami, M.H.; Adilipour, H.; Tavakkoli, M.; Tavakkoli, M. Ramadan Fasting and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Indian J Gastroenterol 2008, 27, 239–241. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tibi, S.; Ahmed, S.; Nizam, Y.; Aldoghmi, M.; Moosa, A.; Bourenane, K.; Yakub, M.; Mohsin, H. Implications of Ramadan Fasting in the Setting of Gastrointestinal Disorders. Cureus 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, S.; Rahmani, F.; Avan, A.; Nematy, M.; Parizadeh, S.M.; Hasanian Mehr, S.M.; Parizadeh, S.M.R. Effects of Ramadan Fasting on the Regulation of Inflammation. JFH 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghpour, S.; Hassanzadeh Keshteli, A.; Daneshpajouhnejad, P.; Jahangiri, P.; Adibi, P. Ramadan Fasting and Digestive Disorders: SEPAHAN Systematic Review No. 7. Journal of Research in Medical Sciences 2012, 17, S150–S158. [Google Scholar]

- Day, A.S.; Ballard, T.M.; Yao, C.K.; Gibson, P.R.; Bryant, R.V. Food-Based Interventions as Therapy for Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Important Steps in Diet Trial Design and Reporting of Outcomes. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 2024, izae185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, S.; Ekhator, C.; Abdelaziz, A.M.; Naveed, H.; Karski, A.; Cook, D.E.; Reddy, S.M.; Affaf, M.; Khan, S.J.; Bellegarde, S.B.; et al. Revolutionizing Inflammatory Bowel Disease Management: A Comprehensive Narrative Review of Innovative Dietary Strategies and Future Directions. Cureus 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, N.; Miller, T.; Suskind, D.; Lee, D. A Review of Dietary Therapy for IBD and a Vision for the Future. Nutrients 2019, 11, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, V.J.D.S.; Severo, J.S.; Mendes, P.H.M.; Da Silva, A.C.A.; De Oliveira, K.B.V.; Parente, J.M.L.; Lima, M.M.; Neto, E.M.M.; Aguiar Dos Santos, A.; Tolentino Bento Da Silva, M. Effect of Dietary Interventions on Inflammatory Biomarkers of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Systematic Review of Clinical Trials. Nutrition 2021, 91–92, 111457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reznikov, E.A.; Suskind, D.L. Current Nutritional Therapies in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Improving Clinical Remission Rates and Sustainability of Long-Term Dietary Therapies. Nutrients 2023, 15, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olendzki, B.; Bucci, V.; Cawley, C.; Maserati, R.; McManus, M.; Olednzki, E.; Madziar, C.; Chiang, D.; Ward, D.V.; Pellish, R.; et al. Dietary Manipulation of the Gut Microbiome in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients: Pilot Study. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2046244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).