Submitted:

29 May 2025

Posted:

03 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

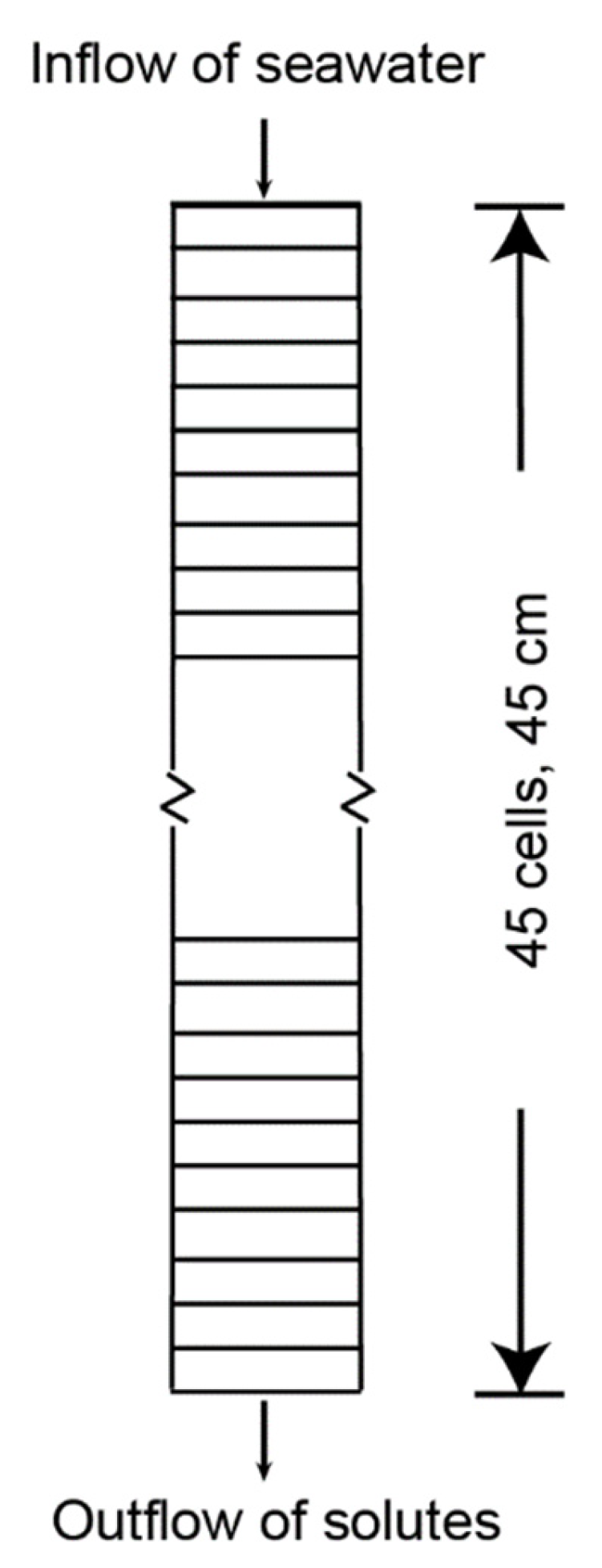

2.1. Geochemical Models of Microcosm Experiments

2.1.1. Sediment Cores

2.1.2. Organic Matter Reaction Rates

| Reaction number | Reaction | Reaction type | Equation | Rates (1/s)-determined by calibration for DF sediments | Rates (1/s)-determined by calibration for DD sediments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Oxidation of organic matter by reduction of Fe(III) [ammonium jarosite is source of the Fe(III) used in the model] | Redox, kinetically controlled | DOM1 + 4x Fe3+4xOH- = xCO2(g) +4x Fe2+ + 3/xH2O + y NH3 + z H3PO4 |

Rate = 3.5e-9 | Rate = 7e-9 |

| 2 | Oxidation of organic matter by reduction of SO42- | Redox, kinetically controlled | DOM1 + (x/2)SO4-2 + (y-2z)CO2 + (y-2z)H2O --------> (x/2)H2S + (x+y-2z)HCO3- + yNH4+ + zHPO42- | IF(tot(“Fe(+3)”) <= 2e-6, THEN rate = 2.5 e-10 | IF(tot(“Fe(+3)”) <= 2e-6, THEN rate = 1.76e-9 |

| 3 | Oxidation of organic matter by methanogenesis | Redox, kinetically controlled | DOM1 + (y-2z)H2O -------> x/2CH4 + (x-2y+4z/2)CO2 + (y-2z)HCO3- + yNH4+ + zHPO42- | IF (tot(“Fe(+3)”) <= 2e-6, AND (tot(“SO4-2)”) <= 2e-6, THEN rate = 3 e-11 | IF (tot(“Fe(+3)”) <= 2e-6, AND (tot(“SO4-2)”) <= 2e-6, THEN rate = 1.76e-10 |

| 4 | FeS precipitation | Equilibrium | FeS = Fe+2 + S-2 | NA | NA |

| 5 | Al(OH)3 (amorphous) precipitation and dissolution | Equilibrium | Al(OH)3 + 3H+ = Al+3 + 3 H2O | NA | NA |

| Constituent or property | DF solution 1-45 |

DD solution 1-45 |

Seawater composition, solution 0 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature °C | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| pH | 6.7 | 4 | 8.5b |

| pe | -- | -- | 8.45 |

| Na | 0.026a | 0.026a | 468d |

| Ca | 0.004a | 0.004a | 10.2d |

| Mg | 0.0015a | 0.0015a | 53.2d |

| K | 0.001a | -- | 10.2d |

| Cl | 0.040 | 0.715b | 545d |

| S(6), sulfate | -- | -- | 28.2d |

| Alkalinity as HCO3- | 4b | 0.1b | 2.3d |

| N(-3), ammonium | 0.001 | 0.075b | - |

| S2- | 0.1b | 0b | -- |

| P | 0.001c | 0.002b | -- |

| Fe(II) | 0.0001b | 0.1b | -- |

| Fe(III) | 0.0001b | 0.001 | -- |

| Si | -- | -- | 0.07d |

| O(0), diss. oxygen | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.75 |

| Al | 0.01b | 0.3b | -- |

| Parameter | DF biogeochemistry | DD biogeochemistry |

|---|---|---|

| Exchange concentrations (mol/L) | 0.50 | 0.85 |

| Surfaces sites (mol/L) | 0.027 | 0.2 |

| Equilibrium phases-- ammonium jarosite concentration (mol/L) | 0.0001 throughout (0.005 in basecase) | Varies with profile (Figure 4) |

| Rate of reaction | DF rates (Table 2) | DD rates (Table 2) |

| Solutions | DF freshwater; artificial seawater (Table 3) | DD freshwater; artificial seawater (Table 3) |

2.1.3. Solution Chemistry, Ion Exchange, and Surface Complexation (Sorption)

2.2. Basecase Geochemical Models

3. Results and Discussion

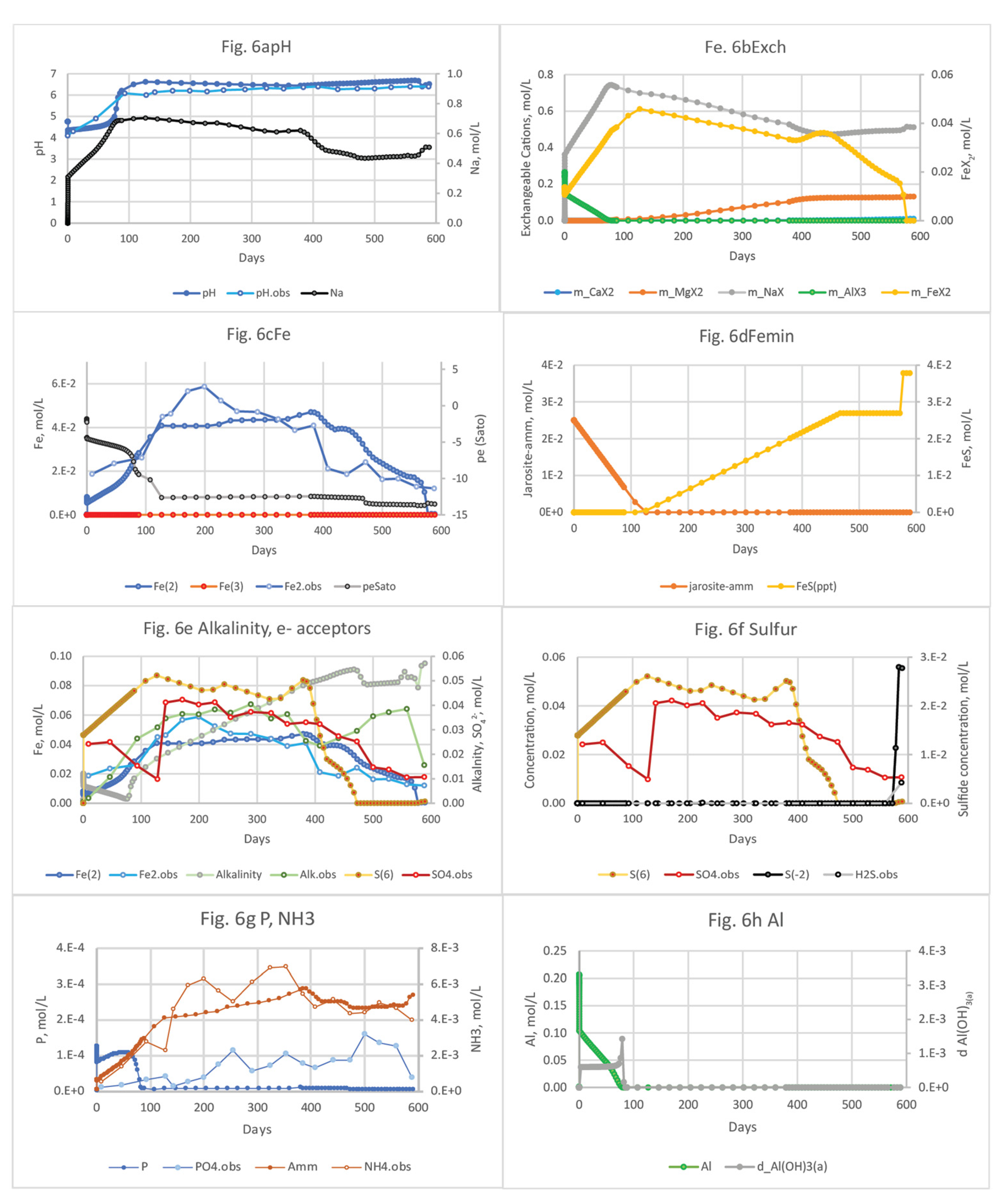

3.1. Geochemical Modeling of Microcosm Experiments

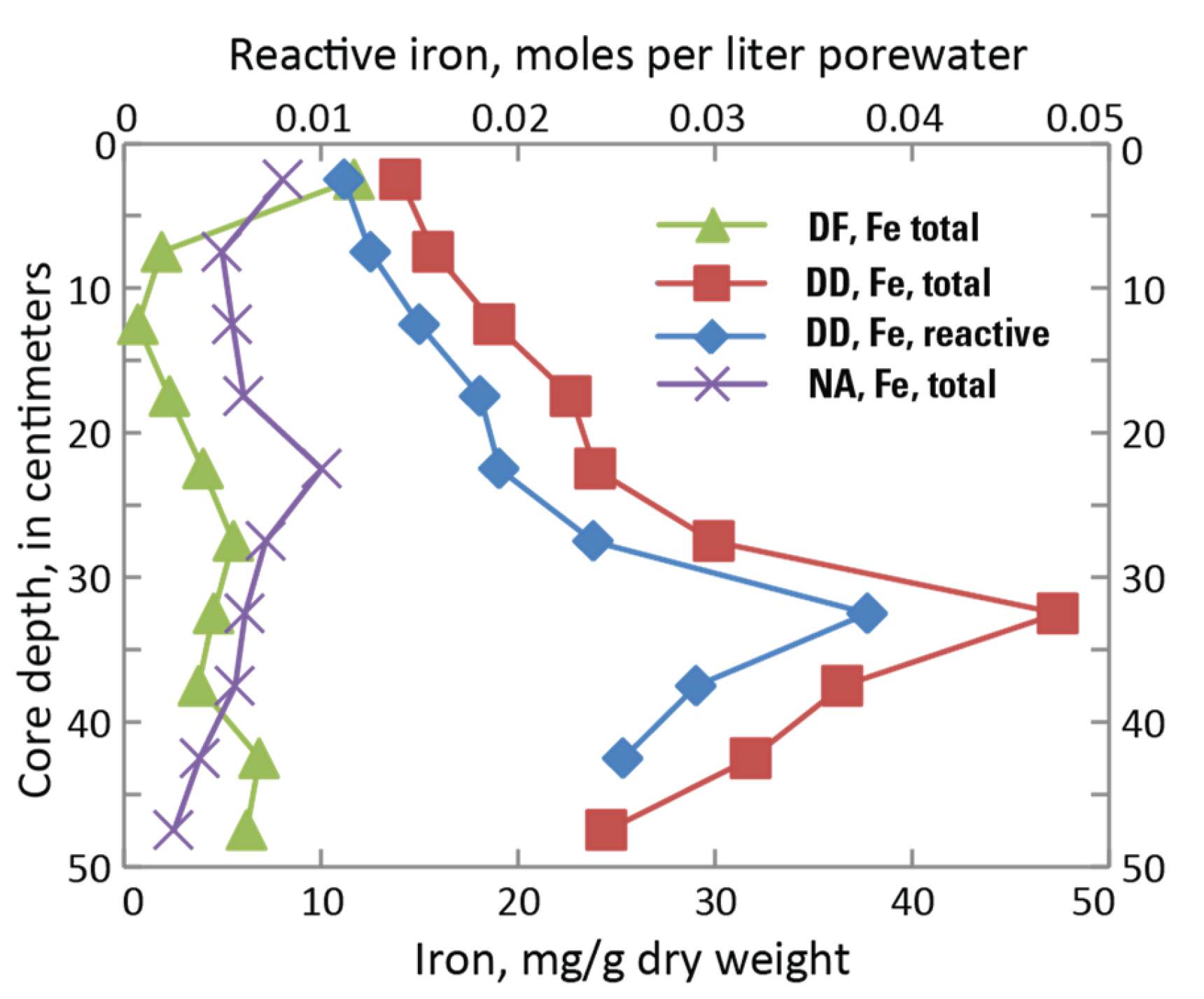

3.1.1. Calibration of Microcosm Models

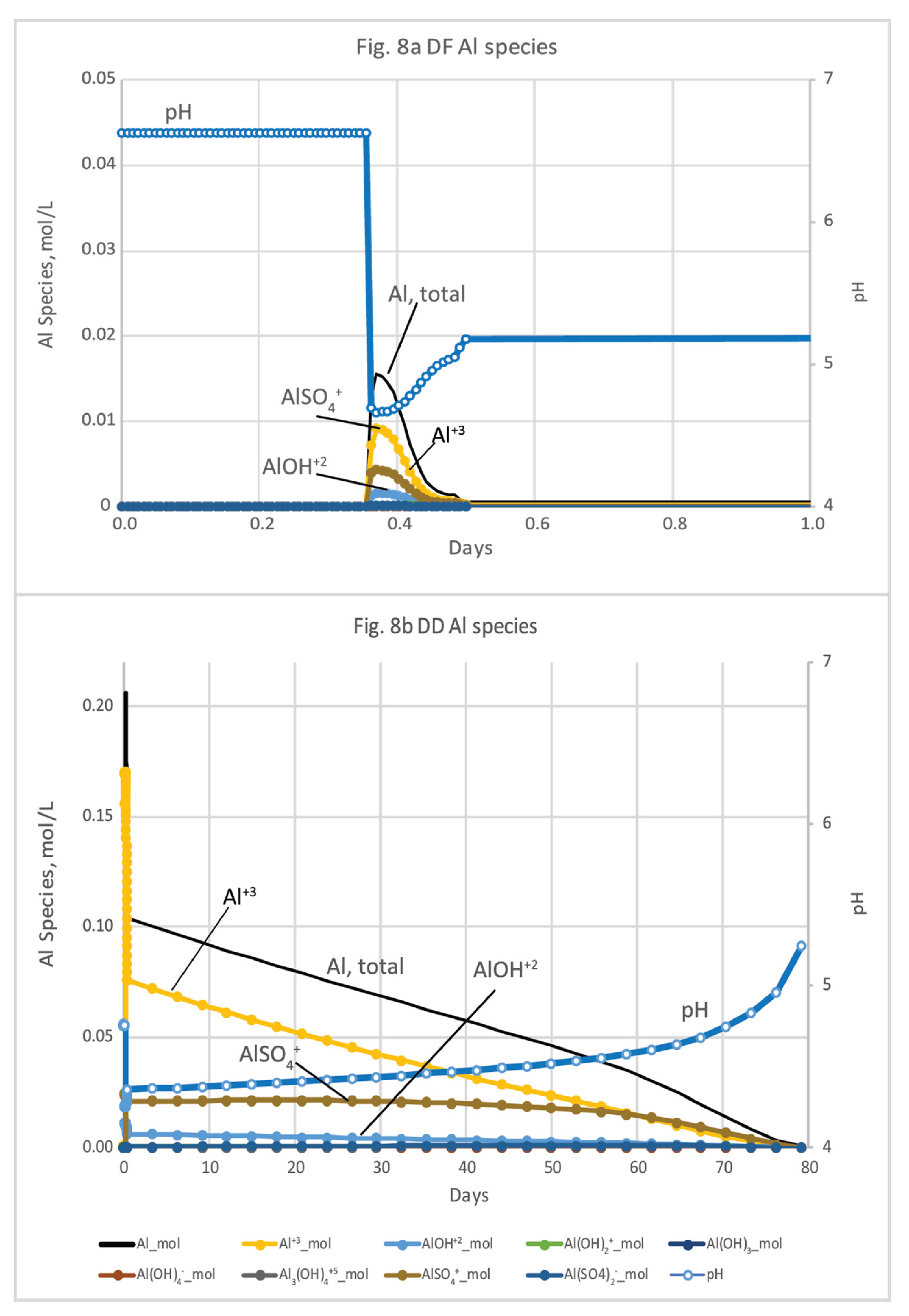

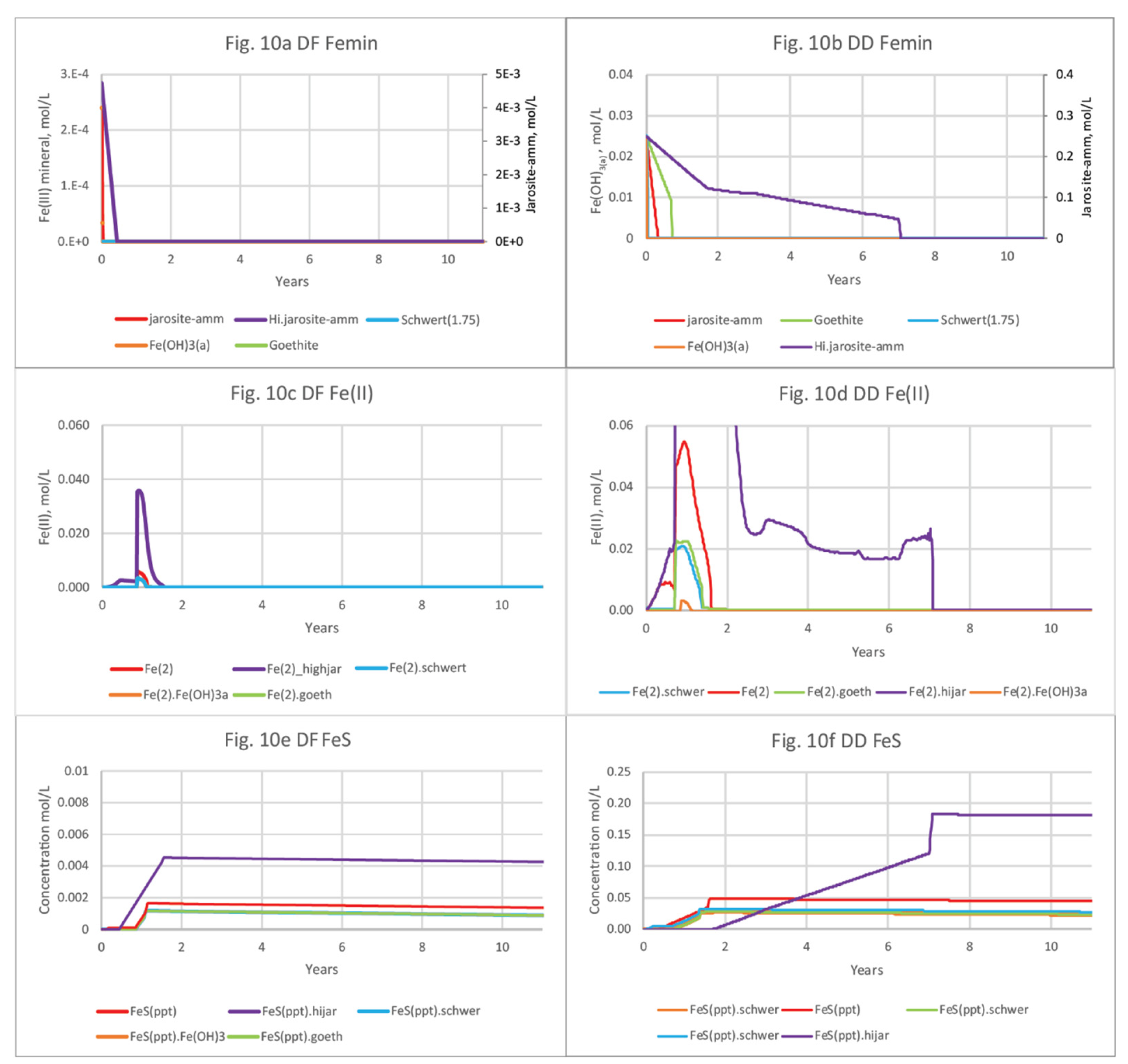

3.1.2. Biogeochemical Model of Diked, Flooded (DF) Sediments

3.1.3. Biogeochemical Model of Diked, Drained (DD) Sediments

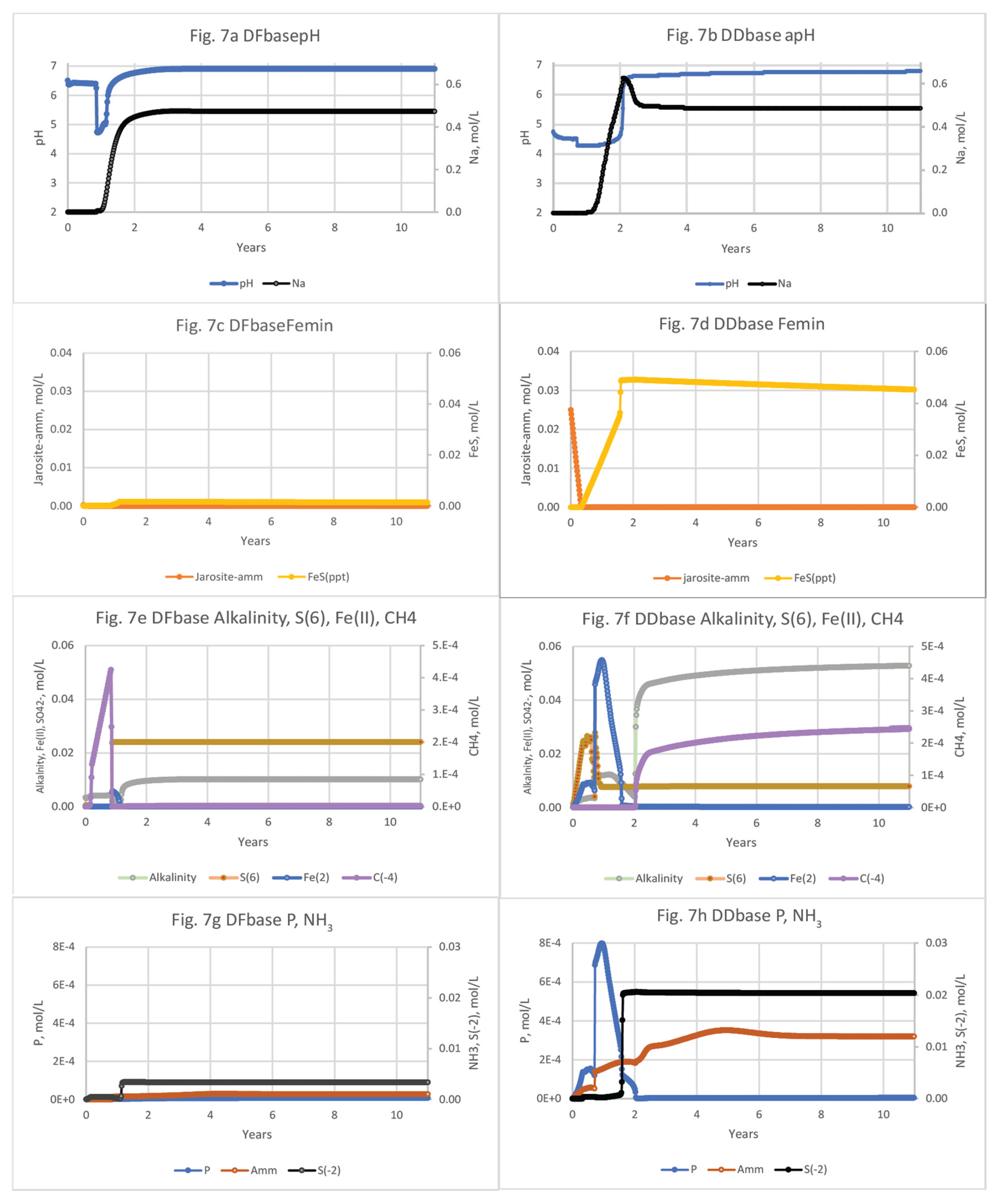

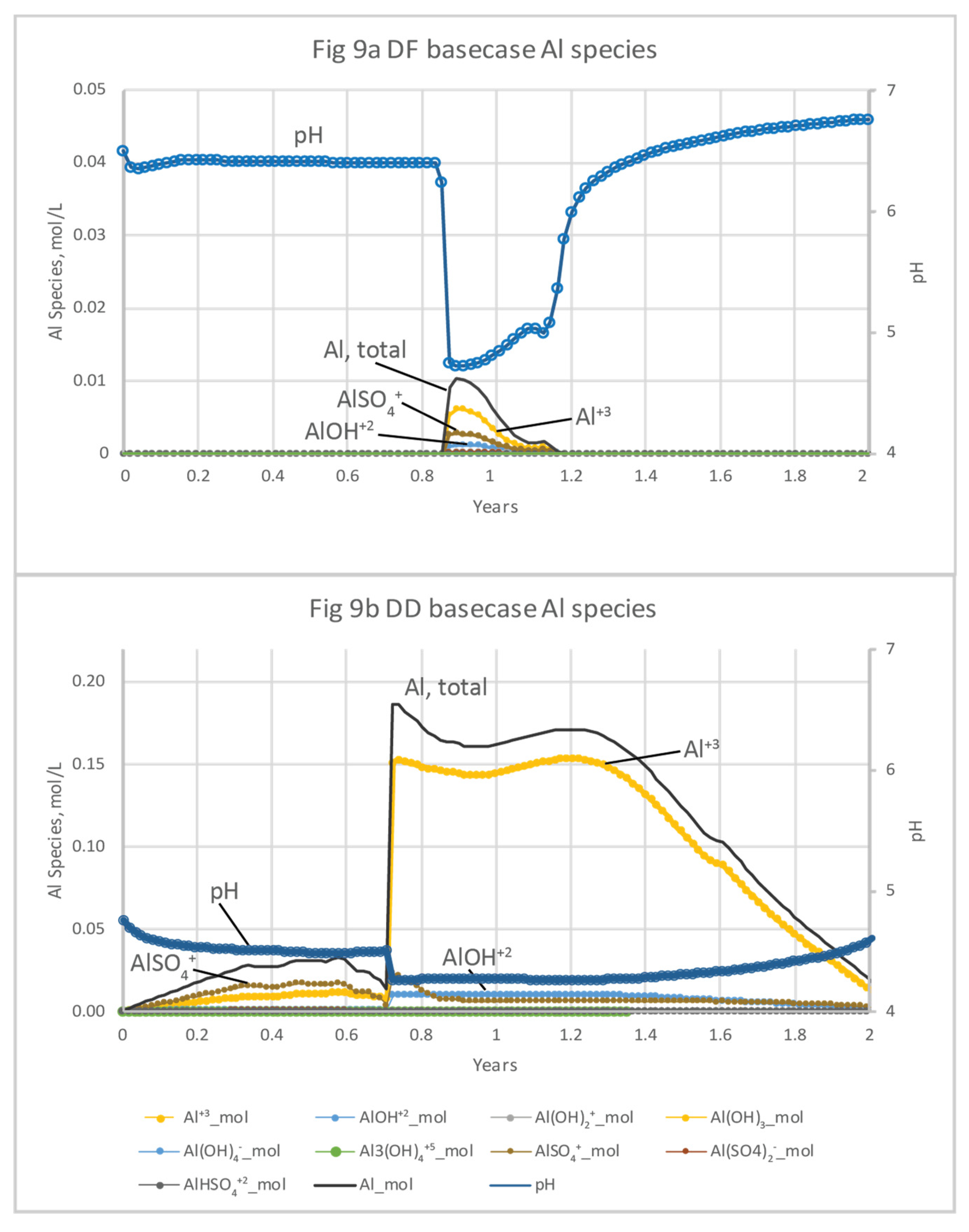

3.2. Basecase Simulations of Seawater Flooding in Diked Marsh Sediments

3.3. Biogeochemical Implications of Seawater Restoration

4. Summary and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

A.1. Previous Marsh Sediment Microcosm Experiments

| Diked, flooded (DF) | Diked, drained (DD) |

|---|---|

| Initial conditions | |

| •Freshwater-submerged marsh sediments, methanogenic | •Subaerially exposed marsh sediments, oxic at surface and reducing with depth |

| •Sedimentary organic matter buildup (absence of inorganic sediments from flood tides, and slow, methanogenic decomposition) | •SOM oxidation and subsidence; High N, P, Fe, H2S or S2-; high sorbed Fe(II), NH4+ |

| •Low dissolved Fe(II) (Fe <5 mg/g); low NH4+ | • FeS and FeS2 oxidation and release of H+ (pH<4), Fe(II), SO42- to create acid SO42- soils |

| •Mackinawite/ pyrite present | •High Fe(II) and Fe(III) content (0.2-0.7 mg/g Fe); most Fe(II) is sorbed; jarosite present as Fe(III) |

| Tidal restoration conditions | |

| Seawater restoration will increase SO42- levels, promote SO42--reducing conditions (oxic at the sediment surface) and acidity, and subsequent ion exchange and release of S2-, Fe, Al, and nutrients (Portnoy & Giblin 1997b). | |

| Re-entry of seawater into seasonally flooded and drained marshes results in significant die off of freshwater biomass and subsequent oxidation of organic matter coupled to the reduction of O2, Fe(III), SO42-, sediment subsides. | |

| •NH4+ and P released due to accelerated organic decomposition (and some NH4+ by ion exchange and desorption) | |

| • SO42--reduction, high H2S, FeS/ FeS2 formation | •FeS/FeS2 oxidation, acidic waters in beginning |

| •Increase in dissolved P | •Increase in dissolved P, Fe, Al |

| •Small peak of Fe(II), depleted by FeS/ FeS2 formation | •High Fe(II) rises to 60 mmol/L (exchanged by Na+ plus reductive dissolution of jarosite) then drops |

References

- Soukup, M.A.; Portnoy, J.W. Impacts from mosquito control-induced sulphur mobilization in a Cape Cod estuary. Environmental Conservation 1986, 13, 47-50.

- Dent, D.L.; Pons, L.J. A world perspective on acid sulphate soils. Geoderma 1995, 67, 263-276. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/001670619500013E. [CrossRef]

- Portnoy, J. Summer oxygen depletion in a diked New England estuary. Estuaries 1991, 14, 122-129.

- Portnoy, J.W.; Giblin, A.E. Biogeochemical effects of seawater restoration to diked salt marshes. Ecological applications 1997, 7, 1054-1063. [CrossRef]

- Portnoy, J.W.; Giblin, A.E. Effects of historic tidal restrictions on salt marsh sediment chemistry. Biogeochemistry 1997, 36, 275-303. [CrossRef]

- Anisfeld, S.C. Biogeochemical Responses to Tidal Restoration. In Tidal Marsh Restoration: A Synthesis of Science and Management; Roman, C.T., Burdick, D.M., Eds.; Island Press/Center for Resource Economics: Washington, DC, 2012; pp. 39-58, ISBN 978-1-61091-229-7. [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.B.; Niekerk, L.V. Ten principles to determine environmental flow requirements for temporarily closed estuaries. Water 2020, 12, 1944. [CrossRef]

- Gedan, K.B.; Silliman, B.R.; Bertness, M.D. Centuries of Human-Driven Change in Salt Marsh Ecosystems. Annual Review of Marine Science 2009, 1, 117-141. [CrossRef]

- Bromberg, K.D.; Bertness, M.D. Reconstructing New England salt marsh losses using historical maps. Estuaries 2005, 28, 823-832. [CrossRef]

- Niering, W.A.; Bowers, R.M. Our disappearing tidal marshes. Connecticut coastal marshes: A vanishing resource. Connecticut Arboretum Bull 1966, 36. https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/arbbulletins/12/.

- Holmquist, J.R.; Eagle, M.; Molinari, R.L.; Nick, S.K.; Stachowicz, L.C.; Kroeger, K.D. Mapping methane reduction potential of tidal wetland restoration in the United States. Communications Earth & Environment 2023, 4, 353. [CrossRef]

- Kroeger, K.D.; Crooks, S.; Moseman-Valtierra, S.; Tang, J. Restoring tides to reduce methane emissions in impounded wetlands: A new and potent Blue Carbon climate change intervention. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 11914. [CrossRef]

- Crooks, S.; Sutton-Grier, A.E.; Troxler, T.G.; Herold, N.; Bernal, B.; Schile-Beers, L.; Wirth, T. Coastal wetland management as a contribution to the US National Greenhouse Gas Inventory. Nature Climate Change 2018, 8, 1109-1112. [CrossRef]

- Sanders-DeMott, R.; Eagle, M.J.; Kroeger, K.D.; Wang, F.; Brooks, T.W.; O’Keefe Suttles, J.A.; Nick, S.K.; Mann, A.G.; Tang, J. Impoundment increases methane emissions in Phragmites-invaded coastal wetlands. Global Change Biology 2022, 28, 4539-4557. [CrossRef]

- Cape Cod National Seashore. East Harbor tidal restoration project. 2022. National Park Service Available online. http://www.nps.gov/caco/naturescience/east-harbor-tidal-restoration-project-page.htm (accessed on.

- DeLaune, R.; Patrick Jr, W.; Van Breemen, N. Processes governing marsh formation in a rapidly subsiding coastal environment. Catena 1990, 17, 277-288. [CrossRef]

- Nyman, J.A.; Carloss, M.; DeLaune, R.; Patrick Jr, W. Erosion rather than plant dieback as the mechanism of marsh loss in an estuarine marsh. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms 1994, 19, 69-84.

- Thom, R.M. Accretion rates of low intertidal salt marshes in the Pacific Northwest. Wetlands 1992, 12, 147-156. [CrossRef]

- Capone, D.G.; Kiene, R.P. Comparison of microbial dynamics in marine and freshwater sediments: Contrasts in anaerobic carbon catabolism 1. Limnology and oceanography 1988, 33, 725-749. [CrossRef]

- Burton, E.D.; Bush, R.T.; Johnston, S.G.; Sullivan, L.A.; Keene, A.F. Sulfur biogeochemical cycling and novel Fe-S mineralization pathways in a tidally re-flooded wetland. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 2011, 75, 3434-3451. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0016703711001773. [CrossRef]

- Wong, V.N.L.; Johnston, S.G.; Burton, E.D.; Bush, R.T.; Sullivan, L.A.; Slavich, P.G. Seawater causes rapid trace metal mobilisation in coastal lowland acid sulfate soils: Implications of sea level rise for water quality. Geoderma 2010, 160, 252-263. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0016706110003034.

- Yvanes-Giuliani, Y.A.M.; Waite, T.D.; Collins, R.N. Exchangeable and secondary mineral reactive pools of aluminium in coastal lowland acid sulfate soils. Science of The Total Environment 2014, 485-486, 232-240. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048969714003945. [CrossRef]

- Appelo, C.A.J.; Postma, D. Geochemistry, Groundwater, and Pollution, Second Edition; CRC Press: Boca Raton, Florida, USA, 2005; 649p.

- Davis, J.A.; Kent, D.B. Chapt. 5. Mineral-Water Interface Geochemistry. In Reviews in Mineralogy, Volume 23: Mineral-Water Interface Geochemistry; Hochella, M.F., Jr., White, A.F., Eds.; Mineralogical Society of America: Washington, D.C., 1990; pp. 177-260. http://www.minsocam.org/MSA/RIM/Rim23.html.

- Kent, D.B.; Wilkie, J.A.; Davis, J.A. Modeling the movement of a pH perturbation and its impact on adsorbed zinc and phosphate in a wastewater-contaminated aquifer. Water Resources Research 2007, 43. [CrossRef]

- Parkhurst, D.L.; Stollenwerk, K.G.; Colman, J.A. Reactive-transport simulation of phosphorus in the sewage plume at the Massachusetts Military Reservation, Cape Cod, Massachusetts; Water-Resources Investigations Report U. S. Geological Survey: 2003. [CrossRef]

- Dzombak, D.A.; Morel, F.M. Surface complexation modeling: hydrous ferric oxide; Wiley-Interscience: New York, 1990, ISBN 0471637319.

- Parkhurst, D.L.; Appelo, C.A.J. Description of input and examples for PHREEQC version 3: a computer program for speciation, batch-reaction, one-dimensional transport, and inverse geochemical calculations; U. S. Geological Survey Techniques and Methods 6-A43; Reston, VA, 2013; p. 519. [CrossRef]

- Hansel, C.M.; Lentini, C.J.; Tang, Y.; Johnston, D.T.; Wankel, S.D.; Jardine, P.M. Dominance of sulfur-fueled iron oxide reduction in low-sulfate freshwater sediments. The ISME Journal 2015, 9, 2400-2412. [CrossRef]

- Berner, R.A. Early diagenesis: a theoretical approach; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, 1980, ISBN 069108260X.

- Capooci, M.; Seyfferth, A.L.; Tobias, C.; Wozniak, A.S.; Hedgpeth, A.; Bowen, M.; Biddle, J.F.; McFarlane, K.J.; Vargas, R. High methane concentrations in tidal salt marsh soils: Where does the methane go? Global Change Biology 2024, 30, e17050. [CrossRef]

- Rickard, D. The composition of mackinawite. American Mineralogist 2024, 109, 401-407. [CrossRef]

- Rickard, D. Chapter 5 - Metastable Sedimentary Iron Sulfides. In Developments in Sedimentology; Rickard, D., Ed.; Elsevier 2012; Volume 65, pp. 195-231, ISBN 0070-4571. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780444529893000052. [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.; Butler, E.C. Monitoring the transformation of mackinawite to greigite and pyrite on polymer supports. Applied geochemistry 2014, 50, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Fanning, D.S.; Rabenhorst, M.C.; Fitzpatrick, R.W. Historical developments in the understanding of acid sulfate soils. Geoderma 2017, 308, 191-206. [CrossRef]

- Singer, P.C.; Stumm, W. Acidic mine drainage: The rate-determining step. Science 1970, 167, 1121-1123. [CrossRef]

- Moses, C.O.; Nordstrom, D.K.; Herman, J.S.; Mills, A.L. Aqueous pyrite oxidation by dissolved oxygen and by ferric iron. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 1987, 51, 1561-1571. [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.D.; Jurinak, J.J. Mechanism of Pyrite Oxidation in Aqueous Mixtures. Journal of Environmental Quality 1989, 18, 545-550. [CrossRef]

- Luther, G.W.; Kostka, J.E.; Church, T.M.; Sulzberger, B.; Stumm, W. Seasonal iron cycling in the salt-marsh sedimentary environment: the importance of ligand complexes with Fe(II) and Fe(III) in the dissolution of Fe(III) minerals and pyrite, respectively. Marine Chemistry 1992, 40, 81-103. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/030442039290049G. [CrossRef]

- Daoud, J.; Karamanev, D. Formation of jarosite during Fe2+ oxidation by Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. Minerals Engineering 2006, 19, 960-967. [CrossRef]

- Nordstrom, D.K.; Blowes, D.W.; Ptacek, C.J. Hydrogeochemistry and microbiology of mine drainage: An update. Applied Geochemistry 2015, 57, 3-16. [CrossRef]

- Appelo, C.A.J. Cation and proton exchange, pH variations, and carbonate reactions in a freshening aquifer. Water Resources Research 1994, 30, 2793-2805. https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/94WR01048. [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.J.; Misut, P.E. Aquifer geochemistry at potential aquifer storage and recovery sites in coastal plain aquifers in the New York city area, USA. Applied Geochemistry 2010, 25, 1431-1452. [CrossRef]

- Lombard, M.A.; Lombard, P.J.; Brown, C.J.; Degnan, J.R. A multi-model approach toward understanding iron fouling at rock-fill drainage sites along roadways in New Hampshire, USA. SN Applied Sciences 2020, 2. [CrossRef]

- USEPA. Aquatic Life Criteria and Methods for Toxics. 2023. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Available online. https://www.epa.gov/wqc/aquatic-life-criteria-and-methods-toxics (accessed on March 15, 2025).

- USEPA. Ambient water quality criteria for ammonia (saltwater). 1989. U.S. Federal Register. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2019-02/documents/ambient-wqc-ammonia-saltwater-1989.pdf.

- Ceazan, M.L.; Thurman, E.M.; Smith, R.S.U. Retardation of ammonium and potassium transport through a contaminated sand and gravel aquifer: The Role of cation exchange. ES & T 1989, 23, 1402-1408. https://pubs.usgs.gov/publication/70015061. [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.P.; Schofield, C.L. Aluminum toxicity to fish in acidic waters. Water, Air, and Soil Pollution 1982, 18, 289-309. [CrossRef]

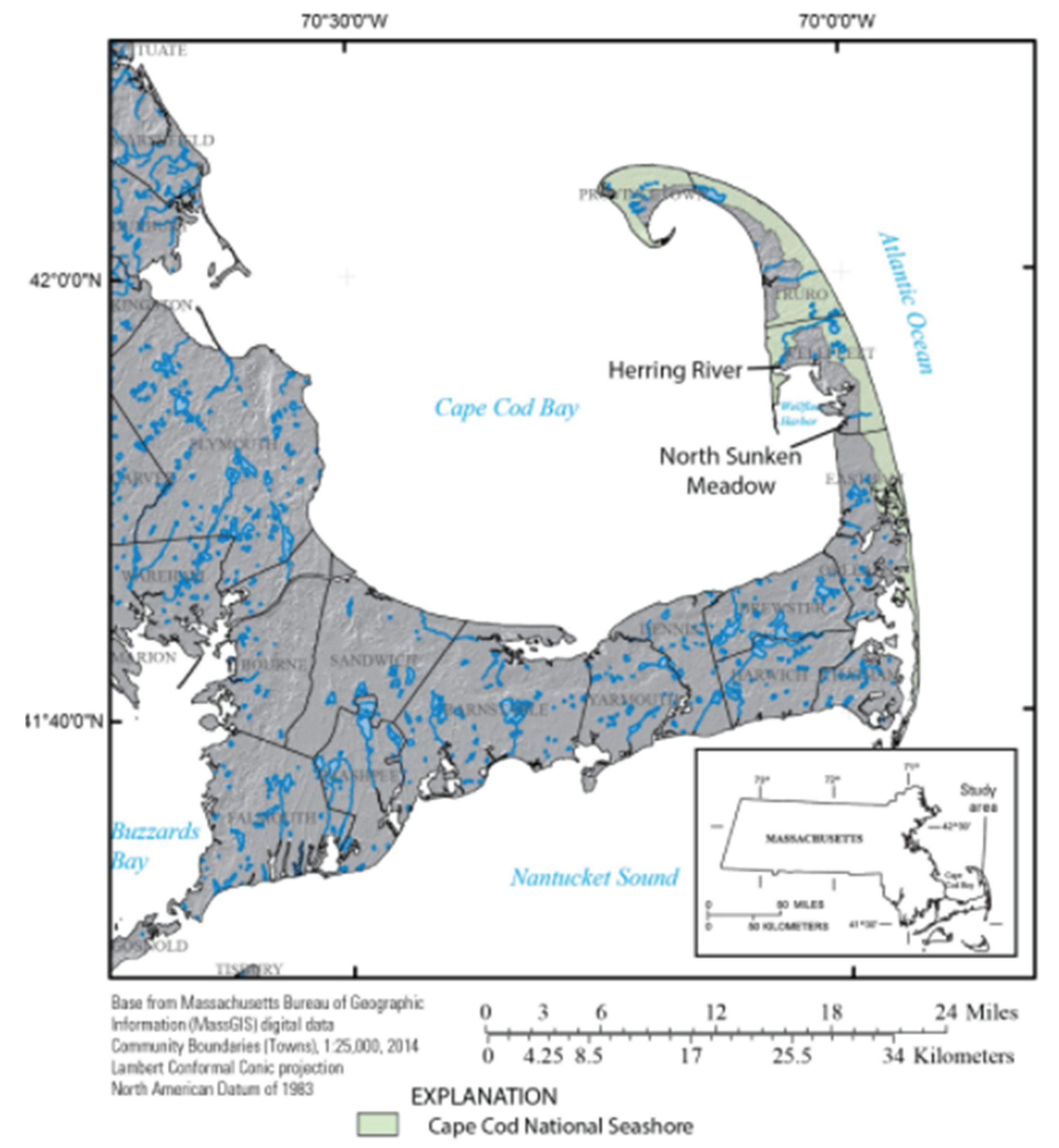

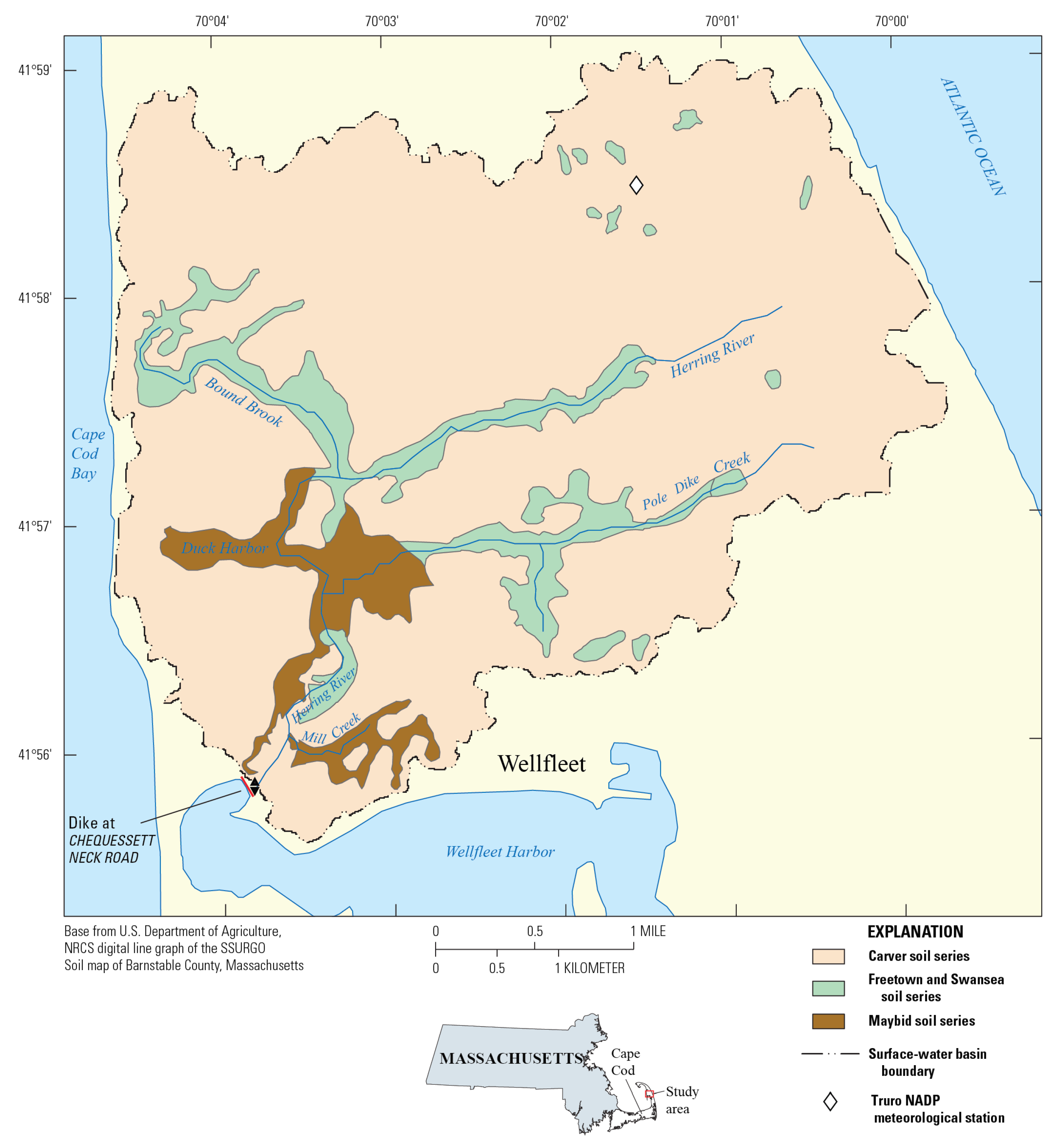

- Mullaney, J.R.; Barclay, J.R.; Laabs, K.L.; Lavallee, K.D. Hydrogeology and interactions of groundwater and surface water near Mill Creek and the Herring River, Wellfleet, Massachusetts, 2017-18. Scientific Investigations Report 2020, 60 p. [CrossRef]

- Friends of the Herring River. Transitioning flow to the Chequessett Neck Road Bridge. Project Updates. 2025. Available online. https://herringriver.org/news/restoration-updates/ (accessed on May 12, 2025).

- Hare, J.A.; Borggaard, D.L.; Alexander, M.A.; Bailey, M.M.; Bowden, A.A.; Damon-Randall, K.; Didden, J.T.; Hasselman, D.J.; Kerns, T.; McCrary, R.; et al. A review of river herring science in support of species conservation and ecosystem restoration. Marine and Coastal Fisheries 2021, 13, 627-664. [CrossRef]

- Portnoy, J.; Phipps, C.; Samora, B. Mitigating the effects of oxygen depletion on Cape Cod NS anadromous fish. Park Science 1987, 8, 12-13.

- MassDCR. Wellfleet Harbor Resource Summary, Area of Critical Environmental Concern (ACEC). Massachusetts Department of Conservation & Recreation 2003, 4 p.. https://www.mass.gov/doc/wellfleet-harbor-resource-summary.

- Brown, C.J. Data and model archive for simulations of seawater restoration on diked salt marshes. U.S. Geological Survey data release 2024, p.. [CrossRef]

- NRCS Soil Survey Staff. Official Soil Series Descriptions. Available online. 2024. Natural Resources Conservation Service, United States Department of Agriculture Available online. https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/resources/data-and-reports/official-soil-series-descriptions-osd (accessed on 11/8/2024).

- Huntington, T.G.; Spaetzel, A.B.; Colman, J.A.; Kroeger, K.D.; Bradley, R.T. Assessment of water quality and discharge in the Herring River, Wellfleet, Massachusetts, November 2015 to September 2017. Scientific Investigations Report 2021, 59 p.. [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, P.C. Soil Survey of Barnstable County, Massachusetts. 1993. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service. Volume 15. http://nesoil.com/barnstable/.

- Dent, D. Acid sulphate soils: a baseline for research and development; Institute for Land Reclamation and Improvement: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1986; 250p, ISBN 9070260980.

- Redfield, A.C. On the proportions of organic derivations in sea water and their relation to the composition of plankton (1934), In James Johnstone Memorial Volume. University Press of Liverpool 1934, 177-192.

- Van Cappellen, P.; Gaillard, J.-F. Biogeochemical dynamics in aquatic sediments. Reviews in Mineralogy 1996, 34, 335-376. [CrossRef]

- Wan, D.; Yu, P.; Kong, L.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, D.; Liu, J. Effects of inland salt marsh wetland degradation on plant community characteristics and soil properties. Ecological Indicators 2024, 159, 111582. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1470160X24000396. [CrossRef]

- Valiela, I.; Costa, J.E. Eutrophication of Buttermilk Bay, a Cape Cod coastal embayment: concentrations of nutrients and watershed nutrient budgets. Environmental Management 1988, 12, 539-553. [CrossRef]

- Nordstrom, D.; Plummer, L.; Wigley, T.; Wolery, T.; Ball, J.; Jenne, E.; Bassett, R.; Crerar, D.; Florence, T.; Fritz, B. A comparison of computerized chemical models for equilibrium calculations in aqueous systems. In Chemical modeling in aqueous systems—Speciation, sorption, solubility, and kinetics:; Jenne, E., Ed.; Series 93; American Chemical Society 1979; pp. 857–892, ISBN 0841204799. [CrossRef]

- Sato, M. Oxidation of sulfide ore bodies; 1, Geochemical environments in terms of Eh and pH. Economic Geology 1960, 55, 928-961. [CrossRef]

- Van Cappellen, P.; Wang, Y. STEADYSED1, A Steady-State Reaction-Transport Model for C, N, S, O, Fe and Mn in Surface Sediments-Version 1.0 User’s Manual. In School of Earth and Atmospheric Science, Georgia Inst. of Techn., Atlanta, Georgia: Atlanta, Georgia, 1995. [CrossRef]

- Harvey, J.W.; Chambers, R.M.; Hoelscher, J.R. Preferential flow and segregation of porewater solutes in wetland sediment. Estuaries 1995, 18, 568-578.

- Neubauer, S.C.; Givler, K.; Valentine, S.; Megonigal, J.P. Seasonal patterns and plant-mediated controls of subsurface wetland biogeochemistry. Ecology 2005, 86, 3334-3344. https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1890/04-1951. [CrossRef]

- Dutrizac, J. Factors affecting alkali jarosite precipitation. Metallurgical Transactions B 1983, 14, 531-539. [CrossRef]

- Howarth, R.; Chan, F.; Conley, D.J.; Garnier, J.; Doney, S.C.; Marino, R.; Billen, G. Coupled biogeochemical cycles: eutrophication and hypoxia in temperate estuaries and coastal marine ecosystems. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 2011, 9, 18-26. https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1890/100008. [CrossRef]

- Krairapanond, A.; Jugsujinda, A.; Patrick, W.H. Phosphorus sorption characteristics in acid sulfate soils of Thailand: Effect of uncontrolled and controlled soil redox potential (Eh) and pH. Plant and Soil 1993, 157, 227-237. [CrossRef]

- Blanc, P.; Lassin, A.; Piantone, P.; Azaroual, M.; Jacquemet, N.; Fabbri, A.; Gaucher, E.C. Thermoddem: A geochemical database focused on low temperature water/rock interactions and waste materials. Applied Geochemistry 2012, 27, 2107-2116. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0883292712001497. [CrossRef]

- Arndt, S.; Jørgensen, B.B.; LaRowe, D.E.; Middelburg, J.J.; Pancost, R.D.; Regnier, P. Quantifying the degradation of organic matter in marine sediments: A review and synthesis. Earth-Science Reviews 2013, 123, 53-86. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0012825213000512. [CrossRef]

- Sterling, S.M.; MacLeod, S.; Rotteveel, L.; Hart, K.; Clair, T.A.; Halfyard, E.A.; O’Brien, N.L. Ionic aluminium concentrations exceed thresholds for aquatic health in Nova Scotian rivers, even during conditions of high dissolved organic carbon and low flow. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 2020, 24, 4763-4775.

- USEPA. Quality criteria for water. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency 440/5-86-001 1986, p.. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2018-10/documents/quality-criteria-water-1986.pdf.

- Cadmus, P.; Brinkman, S.; May, M. Chronic Toxicity of Ferric Iron for North American Aquatic Organisms: Derivation of a Chronic Water Quality Criterion Using Single Species and Mesocosm Data. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 2018, 74, 605-615. [CrossRef]

- Romano, N.; Kumar, V.; Sinha, A.K. Implications of excessive water iron to fish health and some mitigation strategies. Global Seafood Alliance 2021, p.. https://www.globalseafood.org/advocate/implications-of-excessive-water-iron-to-fish-health-and-some-mitigation-strategies/.

- USEPA. Nutrient and Sediment Estimation Tools for Watershed Protection. 2018, p.. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2018-08/documents/loadreductionmodels2018.pdf.

- USEPA. Final Aquatic Life Ambient Water Quality Criteria For Ammonia-Freshwater 2013. 2013, 78 FR 52192p.. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2013/08/22/2013-20307/final-aquatic-life-ambient-water-quality-criteria-for-ammonia-freshwater-2013.

- DeForest, D.K.; Brix, K.V.; Tear, L.M.; Adams, W.J. Multiple linear regression models for predicting chronic aluminum toxicity to freshwater aquatic organisms and developing water quality guidelines. Environmental toxicology and chemistry 2018, 37, 80-90. https://doi.org.10.1002/etc.3922.

- Gensemer, R.W.; Playle, R.C. The bioavailability and toxicity of aluminum in aquatic environments. Critical reviews in environmental science and technology 1999, 29, 315-450. [CrossRef]

- Besser, J.; Cleveland, D.; Ivey, C.; Blake, L. Toxicity of Aluminum to Ceriodaphnia dubia in Low-Hardness Waters as Affected by Natural Dissolved Organic Matter. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 2019, 38, 2121-2127. https://setac.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/etc.4523. [CrossRef]

- Lind, C.J.; Hem, J.D. Effects of organic solutes on chemical reactions of aluminum. Water Supply Paper 1975, 83 p.. [CrossRef]

- Lydersen, E. The solubility and hydrolysis of aqueous aluminium hydroxides in dilute fresh waters at different temperatures. Hydrology Research 1990, 21, 195-204. [CrossRef]

- Schofield, C.L.; Trojnar, J.R. Aluminum toxicity to brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) in acidified waters. In Polluted rain. Environmental Science Research; Toribara, T.Y., Miller, M.W., Morrow, P.E., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, 1980; pp. 341-366, ISBN 1461330629. [CrossRef]

- USEPA. Final aquatic life ambient water quality criteria for aluminum. 2018. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. pp. 161. https://www.epa.gov/wqc/aquatic-life-criteria-and-methods-toxics.

- Driscoll, C.T.; Schecher, W.D. The chemistry of aluminum in the environment. Environmental Geochemistry and Health 1990, 12, 28-49. [CrossRef]

- Rozsa, R. An overview of wetland restoration projects in Connecticut. University of Connecticut, Storrs, 1988; pp. 1-11.

- Burdick, D.M.; Dionne, M.; Boumans, R.M.; Short, F.T. Ecological responses to tidal restorations of two northern New England salt marshes. Wetlands Ecology and Management 1996, 4, 129-144. [CrossRef]

- Mendelssohn, I.A.; McKee, K.L. Spartina Alterniflora Die-Back in Louisiana: Time-Course Investigation of Soil Waterlogging Effects. Journal of Ecology 1988, 76, 509-521. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2260609. [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Huang, J.-F.; Zhu, W.-F.; Tong, C. Impacts of increasing salinity and inundation on rates and pathways of organic carbon mineralization in tidal wetlands: a review. Hydrobiologia 2019, 827, 31-49. [CrossRef]

- Golding, L.A.; Angel, B.M.; Batley, G.E.; Apte, S.C.; Krassoi, R.; Doyle, C.J. Derivation of a water quality guideline for aluminium in marine waters. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 2014, 34, 141-151. https://setac.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/etc.2771. [CrossRef]

- Ruttenberg, K.C.; Sulak, D.J. Sorption and desorption of dissolved organic phosphorus onto iron (oxyhydr)oxides in seawater. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 2011, 75, 4095-4112. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0016703711002286. [CrossRef]

- Eftekhari, N.; Kargar, M.; Zamin, F.; Rastakhiz, N.; Manafi, Z. A Review on Various Aspects of Jarosite and Its Utilization Potentials. Annales de Chimie - Science des Matériaux 2020, 44, 43-52. [CrossRef]

- Stedmon, C.A.; Markager, S.; Søndergaard, M.; Vang, T.; Laubel, A.; Borch, N.H.; Windelin, A. Dissolved organic matter (DOM) export to a temperate estuary: seasonal variations and implications of land use. Estuaries and Coasts 2006, 29, 388-400. [CrossRef]

- Portnoy, J.W. Effects of diking, drainage and seawater restoration on biogeochemical cycling in New England salt marshes. Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts, USA, 1996.

- NADP. National Atmospheric Deposition Program annual precipitation data. 2021. Available online, https: //nadp.slh .wisc.edu/ data/ sites/ siteDetails.aspx? net= NTN&id= MA01 (accessed on October 15, 2024).

| Simula-tion | Microcosm flow, saltwater (solution 0) |

Porosity (%) | Number of pore volumes | Number of shifts | Time per shift (seconds) | Velocity1 (meters/second) | |

| Volume (liters) | Time period | DF / DD | |||||

| Microcosm column experiment models (Portnoy and Giblin, 1997a) | 10 | 12 hours | 90/ 55 | 1.38/ 2.29 | 62/ 103 | 687/ 419 | 1.4E-5/ 2.4E-5 |

| 3 | 3 months | 90/ 55 | 0.42/ 0.69 | 18.9/ 30.9 | 412,031/ 251,793 | 2.4E-8/ 3.97E-8 | |

| 1.5 | 10 months | 90/ 55 | 0.21/ 0.34 | 9.44/ 15.4 | 2,746,872/ 1,678,618 | 3.7E-9/ 5.96E-9 | |

| 3.5 | 7 months | 90/ 55 | 0.49/ 0.80 | 22/ 36 | 824,062/ 503,585 | 1.2E-8/ 1.99E-8 | |

| Basecase models |

72.9 | 12 years | 90/ 55 | 10.2/ 16.7 | 458/ 750 | 828,818/ 506,573 | 1.2E-8/ 1.97E-8 |

| 605 | 100 years | 90/ 55 | 9.9e4/ 1.6e5 | 3,808/ 6,230 |

828,718/ 506,543 |

1.2E-8/ 1.97E-8 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).