1. Introduction

Considerable progress has been made in developing new effective regimens for treating different cancer types. Drug resistance development is a major obstacle to successful cancer therapy [

1]. Great efforts have focused on elucidating the mechanisms responsible for the eventual failure of promising targeted therapies, even though they induce initial tumor shrinkage [

2].

DLBCL is the most common aggressive lymphoma, and it is the most prevalent (30-40%) non-Hodgkin lymphoma at diagnosis.

In a substantial proportion of DLBCL cases, durable remissions can be achieved by combined chemo-immunotherapy. However, about 30% of patients do not respond to therapy or relapse with a resistant disease. Thus, strategies to improve frontline treatment, specifically for high-risk patients, are needed.

New treatments studied in clinical trials (BiTE

® antibody, CART cells) for patients who do not respond to R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) first-line therapy represent a significant addition to the treatment of DLBCL. However, approximately 50% of cases do not respond to therapy [

3] and thus there is still a true need for a new kind of targeted therapy, particularly for those patients who do not benefit from conventional chemotherapy.

Doxorubicin (Dox) is a common chemotherapeutic agent used as first line therapy for numerous cancers. While the mechanism of action for Dox is still investigated, suggested mechanisms include DNA disrupting gene expression, generation of reactive oxygen species, and inhibition of topoisomerase II [

4] . Also Dox induce release of a membrane transcription factor, CREB3L1 [

5] tumor cells with an elevated level of CREB3L are sensitive to doxorubicin [

6] .

Remarkably, the delivery method may influence the pathway activated by Dox. For example, bolus injection caused G2 arrest, phosphorylation of p53, and increased levels of BAX and p21[

7] and significant apoptosis of treated cells. Cells exposed to constant levels of Dox showed decreased apoptosis.

The most serious side effect of Dox treatment is irreversible cardiomyopathy, which corresponding to the cumulative dose. About 4% of patients receiving dosages of 500–550 mg/m2 developed congestive heart failure, 18% with dosages of 551–600 mg/m2, and 36% with cumulative dosages higher than 601 mg/m2 [

8]. Efforts to prevent Dox cardiomyopathy and other side effects have been undertaken through liposomal drug delivery [

9,

10] .

Various types of polymers nanoparticles (NPs) were developed to minimize the loss and degradation of therapeutic agents, improve bio-distribution, control drug release and reduce unwanted side effects. Recently, there is a great interest in developing NPs based on biocompatible and biodegradable polymers such as glycolic acid, poly (lactide-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA).These polymers are degraded and eliminated through the normal metabolic pathways [

11].

Due to the “enhanced permeability and retention” (EPR) effect, NPs with diameters of <200 nm infiltrate from the leaky tumor blood vessels into tumor cells [

12,

13]. Nanoparticles (NP), including liposomes between 10 and 200 nm, are dependent on EPR for their accumulation in tumors. Pegylated (Doxil

®, Lipodox

®) and unpegylated (Myocet

®) formulations are being used in the clinic during recent years.

Several studies have shown that dox can boost antigen presentation by APCs and increase responses of CTLs and T helper cells. Also, DOX can inhibit myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and induce their apoptosis [

14].

Given the role of the immune system to eliminate cancer cells and to induce potent immune responses against the tumor, a combination of chemotherapy and immunotherapy was used in the present study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells.

OCI-LY19, a diffuse large B cell lymphoma cell line, was grown in IMDM. 293T (HEK) cells were grown in DMEM. Media were supplemented with 10% FCS, 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin and 1 mmol/L l-glutamine.

2.2. Apoptosis and Cell Death Analysis.

Cell death was determined using annexin-V and propidium iodide (PI). Cells (5x105) were incubated with various treatments (NPs, chemotherapy) for 48 hours. Cells were then stained using 1 µg/ml annexin V-FITC (Abcam), washed once in annexin-V-binding buffer, stained with 0.5 µg/ml PI and analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur, Becton Dickinson).

2.3. Caspase-3 Activity Assay.

Subcutaneous tumor samples were homogenized [

30] and Caspase-3 activity in 50 µg protein fractions was determined by the colorimetric CaspACE™ Assay System (Promega), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.4. Preparation of Poly (lactide-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) Nanoparticles (NPs).

Polymeric nanospheres, (nanoparticles, NPs) were prepared using a well-established interfacial deposition method [

31]. Briefly, the organic phase contained 150 mg of the polymer PLGA, MW 50,000 Dalton and 5 mg of the cross-linker OCA (oleylcysteineamide), synthesized and characterized according to Karra et al [

17], dissolved in 25 ml acetone prior to NP formation. For the preparation of nanoparticles, the organic phase was added to 50 ml of an aqueous solution containing 50 mg Solutol

® HS 15. The suspension was stirred at 900 rpm for 30 minutes and the acetone fraction was then evaporated with a rotor evaporator. The formulations were adjusted to pH 6.5-7.

2.5. Preparation of Doxorubicin Loaded NPs

200 ul of trimethylamine and 100 mg of DOX-HC was added to the organic phase. The suspension was stirred at 900 rpm for 30 minutes and subsequently, evaporated the acetone fraction by rotor evaporator. Following encapsulation, the non-capsulated DOX was separated, by vivaspin filters (300k) at 4500 rpm of centrifugation in three cycles of washings. The yield of the encapsulation was determined using UV detection method at wavelength of 475 nm.

2.6. In-Vivo DLBCL Subcutaneous Xenograft Model.

All experiments were approved by the institute animal care ethics committee (MD-16-14998-5). Male NOD/SCID mice, 7-8 weeks old, were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions. Mice were injected sub-cutaneously with tumorigenic OCI-LY19-GLuc cells in the right flank. These cells constitutively express GLuc, allowing photon flux detection by IVIS imaging. Mice were randomly divided into treatment groups that received the following formulations: MTV-NPs, CD40L-NPs, CD40L-MTV-NPs or PLGA-NPs. The formulations (200µl, 0.2 mg MTV/0.5 mg PLGA, 0.5 mg CD40L) were injected into the mouse tail vein at days 4, 11 and 20 post tumor cell injection.

Weight and tumor volume were measured every 2-3 days throughout the experiment. Tumors were measured with a caliper and under IVIS. Mice were sacrificed when the one-dimensional tumor diameter reached 1.5 cm (according to the animal ethics guidelines) and tumors were collected for analysis.

2.7. Statistical Analysis.

Data from mice were expressed as mean ± SE, and the results were analyzed using a two-tailed Student's t test to assess statistical significance. For comparison of mice survival, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and log-rank test were used (Origin 2020, OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA). Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

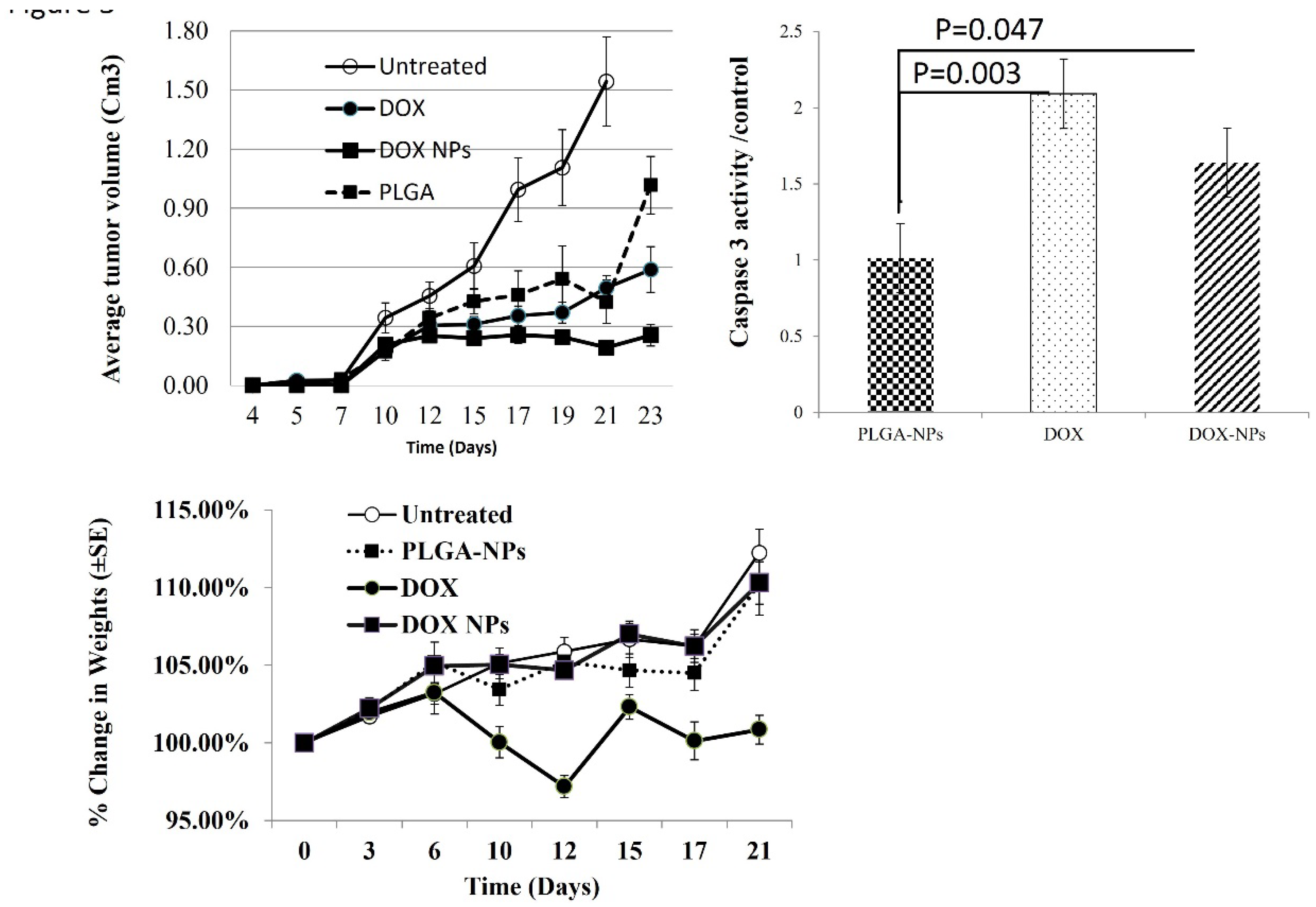

3.1. In Vivo Anticancer Activity and Cytotoxic Effect of Dox

Mice were injected subcutaneously with OCI-LY19-DLBCL cells and tumor volume was measured. In this model. Tumors develop 7 days after injection of cells [

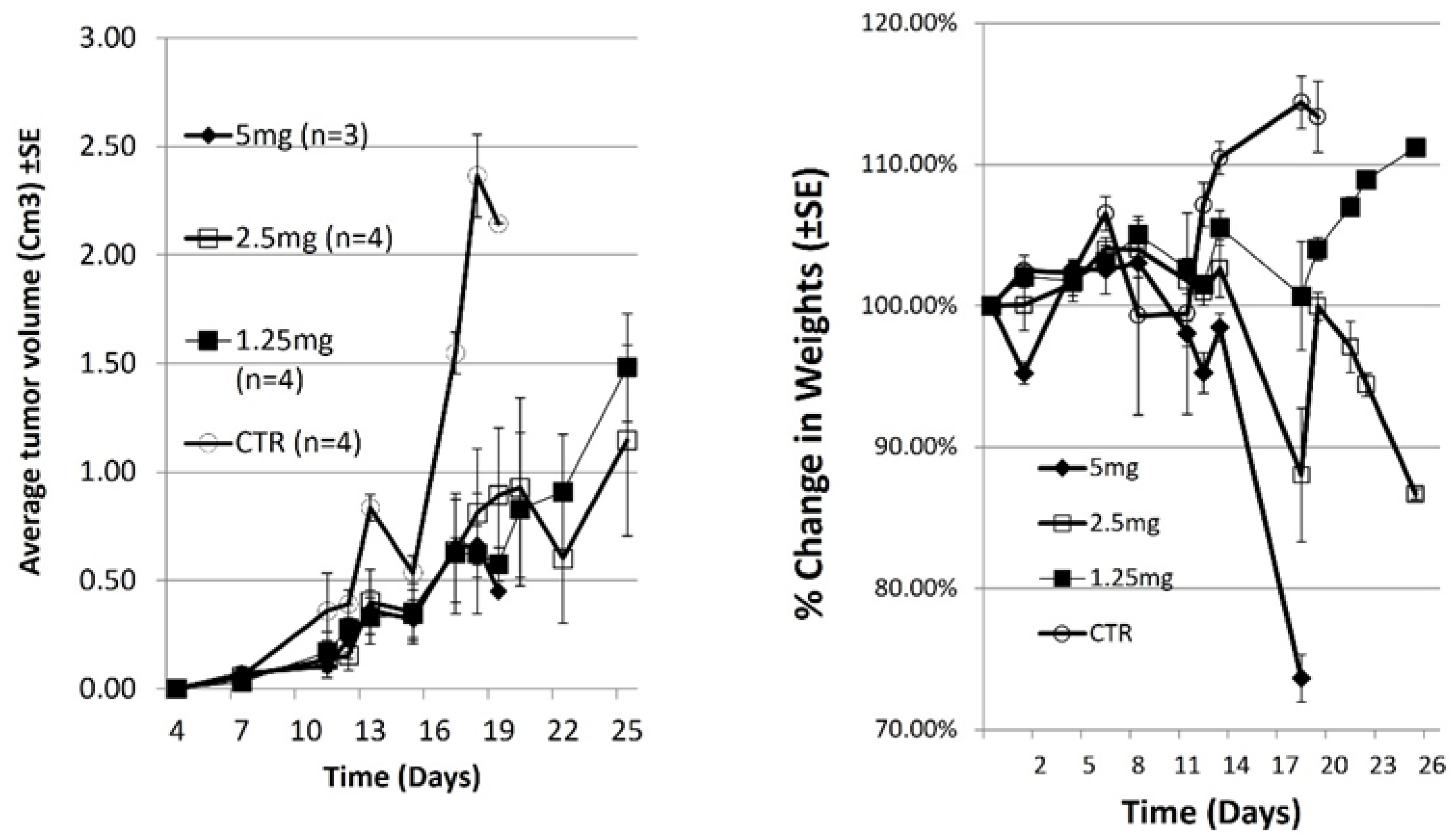

15]. On days 4, 11 and 19 post xenograft mice were treated with increasing dose of Doxorubicin (DOX). Tumor volume and body weight were measured at the indicated time points (

Figure 1A).

All Untreated mice were sacrificed at day 19 when tumor diameter >1.5 cm. In mice treated with 5, 2.5 or 1.25 mg/kg DOX, tumors grew slowly, and were significantly smaller than tumors in untreated mice (

p = 0.0081,0.0087 and 0.0044 respectively, n=4). Change in body weight is an important parameter to evaluate systemic toxicity. All mice treated with 5mg DOX were sacrificed by day 19due to body weight loss (>20%). The mice also exhibited weakened movement and vitality.

Figure 1B shows that the body weight of mice treated with 1.25mg/kg DOX increased throughout the experiment. The mice also remained vigorous and had a healthy appearance (not shown). In contrast, there was notable body weight loss in the 2.5mg/kg DOX-treated group (p= 0.047, n=4) (

Figure 1B). Moreover, the mice in this group exhibited weakened movement and vitality.

Our conclusions from this experiment are that toxicity of doxorubicin was high at 5mg/kg dose and intermediate toxicity was at 2.5mg/kg dose. Treatment of mice with DOX delayed tumor growth and 1.25mg/kg is the best concentration in terms of effectivity with low toxicity.

3.1. PLGA–OCA Enhance Immunity and Tumor Cell Death.

To improve the delivery and efficacy of DOX for the treatment of tumors, we chose to conjugate DOX onto PLGA surface-activated NPs.

We have previously used PLGA-NPs in vivo and evaluated their safety. PLGA-NPs [

16] and PLGA-NPs conjugated to a linker (OCA) [

17] did not elicit any toxic effect in mice according to blood sampling, clinical chemistry parameters and differential and histopathologic examination of mice organs [

16,

17].

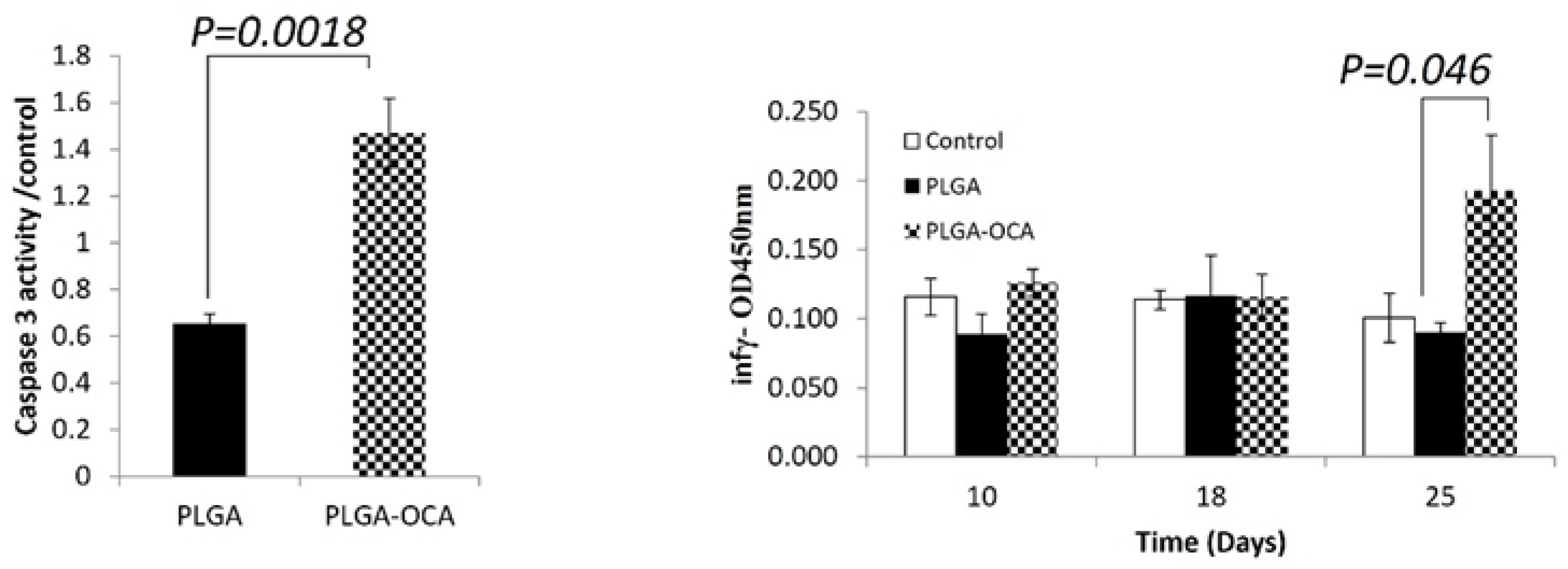

To test the effect of PLGA and PLGA-OCA in our model, Xenograft mice were treated once a week with PLGA or PLGA-OCA beginning at day 4 after xenograft for 4 weeks (total 4 injections). At day 23 mice were sacrificed, Subcutaneous tumors were removed and crude protein from tumor lysates was analyzed for caspase 3 activity, an indicator of apoptotic cell death. caspase 3 activity in tumors from mice that were treated with PLGA-OCA was 2.5 folds greater compared to mice treated with PLGA (

p = 0.0018) (

Figure 2A). This observation indicates that PLGA-OCA leads to induction of apoptotic cell death and destruction of tumor cells, and furthermore confirms the ability of the nanoparticles to target the tumors.

PLGA-OCA Treatments can induce immunological response in immunodeficient mice as measured by of interferon-γ levels, attributed to NK cells since these mice do not have other immune cells [

18]. At the end of the experiment (25 days), significantly High levels of interferon-γ were detected in the serum of mice treated with PLGA-OCA (

p=0.046 compared to PLGA-treated) while in PLGA-treated mice interferon-γ serum levels were the same as that of untreated mice (

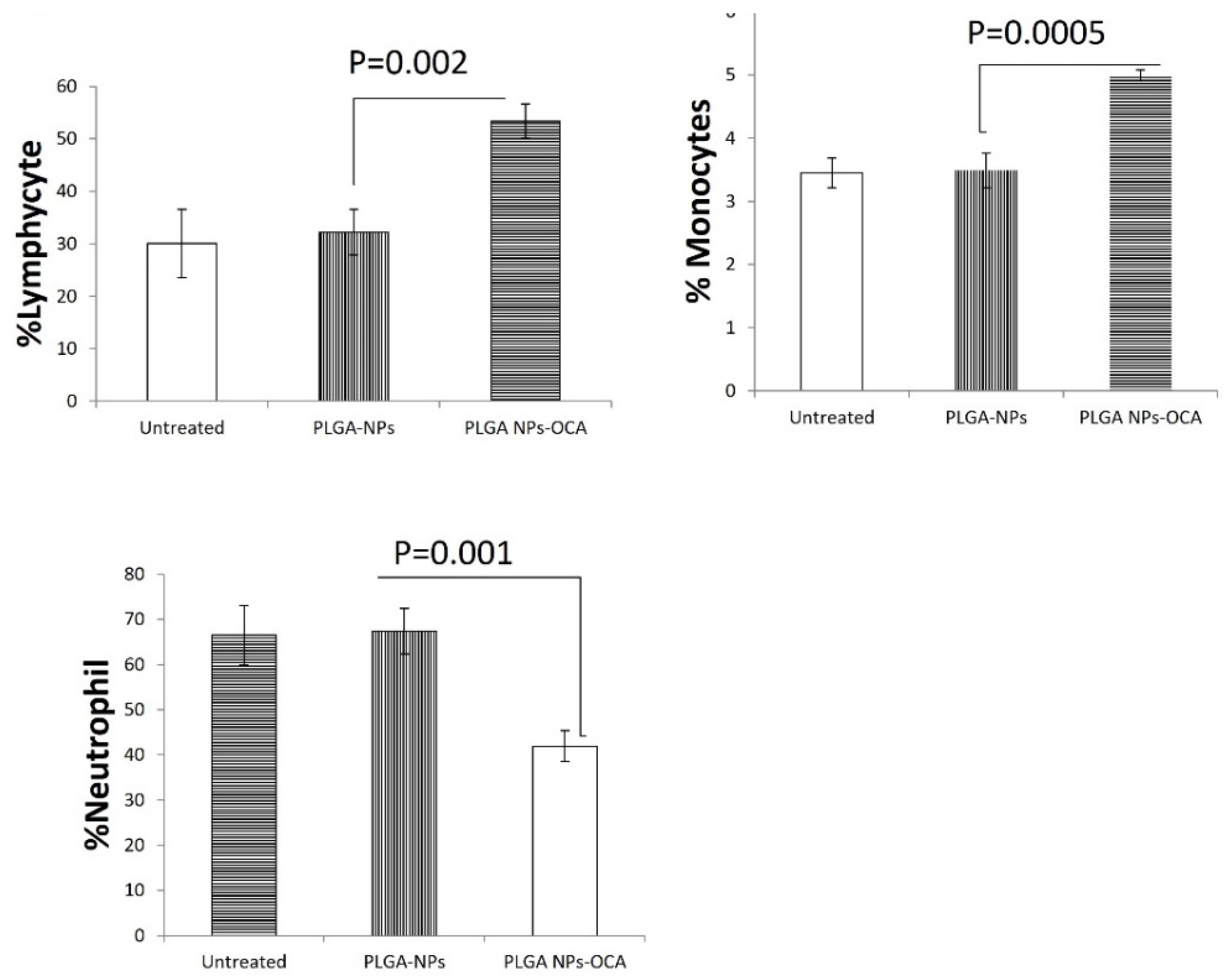

Figure 2B). Complete blood count (CBC) shows a percentage increase of lymphocytes and monocytes compared to decrease in neutrophils cells (

Figure 3). This result shows that INF-γ levels increment in PLGA-OCA-NPs treated mice were in association with immune system cells response,

3.2. DOX-NPs Induce Cell Death In-Vitro and In-Vivo.

To improve the delivery and efficacy of DOX for the treatment of tumors, we next conjugated DOX onto PLGA surface-activated NPs

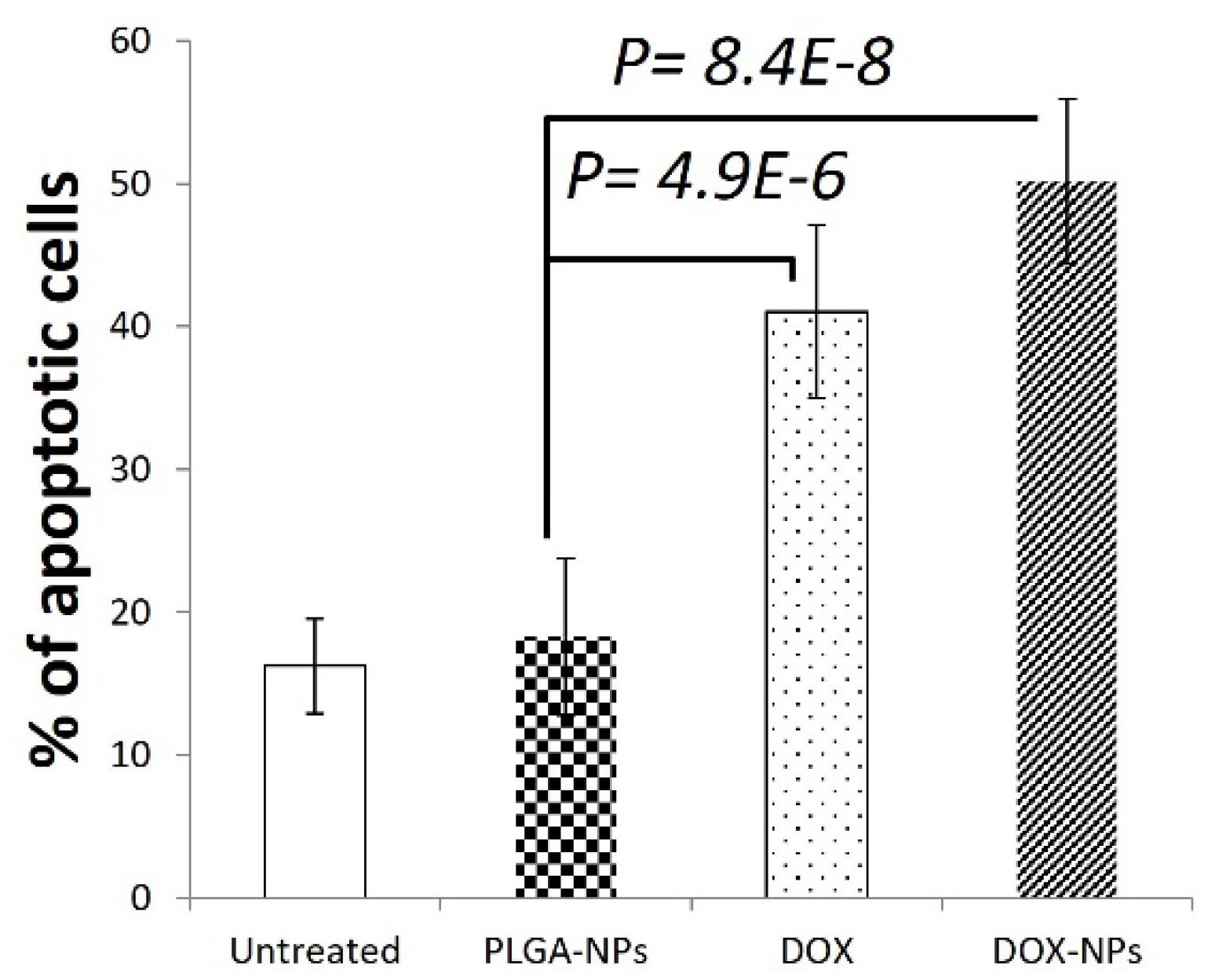

and OCI-LY19 DLBCL cells were used to evaluate the effect of DOX-NPs on cell survival. Treatment with DOX (2µM, 24h) significantly induces apoptosis in OCI-LY19 determined by annexin V staining and flow cytometry (

p=4.9E-6, n=5 replicates). DOX-NPs (xx, 24h) also induced highly significant apoptosis of OCI-LY19 (

p=8.4E-8, n=5 replicates) (

Figure 4).

The therapeutic potential of DOX-NPs treatment was evaluated

in-vivo using the DLBCL model [

15]. Mice were injected subcutaneously with OCI-LY19 cells and tumor volume was measured (N=10). On days 4, 11 and 20, mice were treated with PLGA-NPs (0.5 mg PLGA), DOX (1.25 mg/kg) and DOX-NPs (1.25mg/kg DOX/ 0.5 mg PLGA) (

Figure 5),

All untreated controls died due to tumor diameter exceeding 1.5 cm by 21 days after tumor cell inoculation, mice were sacrificed at days 21-23.

Significant antitumor activity was measured by tumor volume in mice treated with DOX-NPs compared to PLGA-NPs at day 21 and 23 (

p= 0.00196, n=6) (

Figure 5A).

DOX-NPs-treated tumors grew slowly, and 21- 23 days after injection they were significantly smaller than DOX (p =0.034, n=6).

Subcutaneous tumors were removed and crude protein from tumor lysates was analyzed for caspase 3 activity, an indicator of apoptotic cell death. High level of caspase 3 activity was found in tumors from mice treated with DOX and DOX-NPs (

p 0.030 and 0.047 compared to PLGA-NPs respectively, n=6) This observation indicates that DOX-PLGA leads to induction of apoptotic cell death and destruction of tumor cells, and importantly confirms the ability of the nanoparticles to target the tumors [

15] (

Figure 5).

Change in body weight is an important parameter to evaluate systemic toxicity of treatment, there was notable body weight loss in the DOX-treated group (

Figure 5) (p=2.7E-3, n=10). Moreover, the mice in this group exhibited weakened movement and vitality.

4. Discussion

Immunotherapy is an evolving field in the treatment of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) [

1]. Rituximab, a monoclonal antibody that targets CD20-positive B cells, is commonly used in combination with chemotherapy for DLBCL [

19]. Studies are exploring the efficacy of rituximab in various treatment regimens [

19]. Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, such as axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel) and tisagenlecleucel, has shown promising results in treating relapsed or refractory DLBCL [

20,

21]. Studies are being conducted to evaluate its role in frontline treatment [

20,

21] Identifying biomarkers that predict treatment response or prognosis allows for more personalized treatment approaches [

22]. Research is focusing on investigating more intensive chemotherapy regimens or dose-dense approaches to improve outcomes in high-risk patients [

23]. The role of targeted therapies, such as inhibitors of specific signaling pathways or genetic mutations, in combination with standard treatments is also being evaluated [

23]. Autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) is being studied as part of frontline treatment strategies for eligible patients [

23] The role and optimal use of radiotherapy in treating DLBCL, especially in high-risk patients, are also being examined [

23]. Various trials are investigating new drugs, combination therapies, and treatment strategies [

24].

This study using a DLBCL mice model highlights the dose-dependent effects of DOX on tumor growth. Slowed tumor progression and identification of the optimal 1.25 mg/kg concentration emphasize crucial considerations for clinical applications.

Conjugating DOX onto PLGA-OCA nanoparticles proves effective in inducing apoptotic cell death, showcasing potential in targeted DLBCL therapy. Elevated interferon-γ levels in PLGA-OCA-treated mice suggest a dual benefit of enhanced immune responses.

DOX-NPs demonstrate the ability to induce apoptosis in vitro and sustain antitumor activity in vivo, outperforming DOX alone. Caspase 3 activity measurement confirms their potential as an effective therapeutic intervention for DLBCL.

Contrasting body weight changes between DOX and DOX-NPs highlights the latter's potential for mitigating toxicity. Preservation of body weight and vitality in the DOX-NPs group suggests a more favorable side effect profile, crucial for patient tolerance.

Liposomal drug delivery systems for doxorubicin (Dox) have been developed to reduce cardiotoxicity and other side effects associated with the conventional form of the drug [

25]. Cardiomyopathy is a well-known side effect of Dox, and liposomal formulations are designed to enhance drug delivery to the tumor while minimizing exposure to normal tissues, including the heart [

25]

The encapsulation of Dox within liposomes can limit its release in the bloodstream, reducing the direct exposure of the heart to the drug [

26]

Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) has been extensively utilized in the development of drug delivery systems for various antitumor drugs. Some notable examples include the encapsulation of Doxorubicin (Dox), Paclitaxel, Cisplatin, Camptothecin, and Methotrexate within PLGA nanoparticles [

27]. These formulations aim to improve drug solubility, enable controlled release, and enhance targeted delivery to tumor sites, ultimately contributing to improved therapeutic efficacy and reduced systemic toxicity [

28]

PLGA's biodegradable and biocompatible nature makes it an attractive choice for designing nanocarriers that offer sustained release capabilities and protect the encapsulated drugs from premature degradation [

29]. Ongoing research in this field focuses on optimizing PLGA-based formulations to address challenges in cancer treatment, with the aim of achieving better treatment outcomes and minimizing adverse effects [

26].

This article provides comprehensive insights into DOX and innovative delivery systems (PLGA-OCA and DOX-NPs) for DLBCL treatment. The identified optimal dosage and promising outcomes of nanoparticle-based approaches contribute to ongoing efforts in refining cancer treatment strategies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Kamin incentive program, Israel Innovation Authority (DBY and SB), Eleanor Fox (DBY) and Aleen and David M. Epstein Fund for Hematology/Oncology Research (DBY).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Foo, J.; Michor, F. Evolution of acquired resistance to anti-cancer therapy. Journal of theoretical biology 2014, 355, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girotti, M.R.; Marais, R. Deja Vu: EGF receptors drive resistance to BRAF inhibitors. Cancer discovery 2013, 3, 487–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez, J.C.; Bachmeier, C.; Kharfan-Dabaja, M.A. CAR T-cell therapy for B-cell lymphomas: clinical trial results of available products. Therapeutic advances in hematology 2019, 10, 2040620719841581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, K.; Zhang, J.; Honbo, N.; Karliner, J.S. Doxorubicin cardiomyopathy. Cardiology 2010, 115, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denard, B.; Lee, C.; Ye, J. Doxorubicin blocks proliferation of cancer cells through proteolytic activation of CREB3L1. eLife 2012, 1, e00090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denard, B.; Pavia-Jimenez, A.; Chen, W.; Williams, N.S.; Naina, H.; Collins, R.; Brugarolas, J.; Ye, J. Identification of CREB3L1 as a Biomarker Predicting Doxorubicin Treatment Outcome. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0129233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lüpertz, R.; Wätjen, W.; Kahl, R.; Chovolou, Y. Dose- and time-dependent effects of doxorubicin on cytotoxicity, cell cycle and apoptotic cell death in human colon cancer cells. Toxicology 2010, 271, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singal, P.K.; Iliskovic, N. Doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 1998, 339, 900–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, C.; Santos, R.X.; Cardoso, S.; Correia, S.; Oliveira, P.J.; Santos, M.S.; Moreira, P.I. Doxorubicin: the good, the bad and the ugly effect. Curr Med Chem 2009, 16, 3267–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiyath, S.M.; Rasul, M.; Lee, B.; Wei, G.; Lamba, G.; Liu, D. Comparison of safety and toxicity of liposomal doxorubicin vs. conventional anthracyclines: a meta-analysis. Experimental hematology & oncology 2012, 1, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Chen, S.C. Micro and nano-fabrication of biodegradable polymers for drug delivery. Advanced drug delivery reviews 2004, 56, 1621–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, J.; Nakamura, H.; Maeda, H. The EPR effect: Unique features of tumor blood vessels for drug delivery, factors involved, and limitations and augmentation of the effect. Advanced drug delivery reviews 2011, 63, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, H. The enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect in tumor vasculature: the key role of tumor-selective macromolecular drug targeting. Advances in enzyme regulation 2001, 41, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alizadeh, D.; Trad, M.; Hanke, N.T.; Larmonier, C.B.; Janikashvili, N.; Bonnotte, B.; Katsanis, E.; Larmonier, N. Doxorubicin eliminates myeloid-derived suppressor cells and enhances the efficacy of adoptive T-cell transfer in breast cancer. Cancer Res 2014, 74, 104–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elrahman, I.; Nassar, T.; Khairi, N.; Perlman, R.; Benita, S.; Ben Yehuda, D. Novel targeted mtLivin nanoparticles treatment for disseminated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Oncogene 2021, 40, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harush-Frenkel, O.; Bivas-Benita, M.; Nassar, T.; Springer, C.; Sherman, Y.; Avital, A.; Altschuler, Y.; Borlak, J.; Benita, S. A safety and tolerability study of differently-charged nanoparticles for local pulmonary drug delivery. Toxicology and applied pharmacology 2010, 246, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karra, N.; Nassar, T.; Ripin, A.N.; Schwob, O.; Borlak, J.; Benita, S. Antibody conjugated PLGA nanoparticles for targeted delivery of paclitaxel palmitate: efficacy and biofate in a lung cancer mouse model. Small 2013, 9, 4221–4236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreno, B.M.; Garbow, J.R.; Kolar, G.R.; Jackson, E.N.; Engelbach, J.A.; Becker-Hapak, M.; Carayannopoulos, L.N.; Piwnica-Worms, D.; Linette, G.P. Immunodeficient mouse strains display marked variability in growth of human melanoma lung metastases. Clin Cancer Res 2009, 15, 3277–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coiffier, B.; Thieblemont, C.; Van Den Neste, E.; Lepeu, G.; Plantier, I.; Castaigne, S.; Lefort, S.; Marit, G.; Macro, M.; Sebban, C.; :, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. : Long-term outcome of patients in the LNH-98.5 trial, the first randomized study comparing rituximab-CHOP to standard CHOP chemotherapy in DLBCL patients: a study by the Groupe d'Etudes des Lymphomes de l'Adulte. Blood 2010, 116, 2040–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelapu, S.S.; Locke, F.L.; Bartlett, N.L.; Lekakis, L.J.; Miklos, D.B.; Jacobson, C.A.; Braunschweig, I.; Oluwole, O.O.; Siddiqi, T.; Lin, Y.; et al. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel CAR T-Cell Therapy in Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2017, 377, 2531–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, S.J.; Svoboda, J.; Chong, E.A.; Nasta, S.D.; Mato, A.R.; Anak, Ö.; Brogdon, J.L.; Pruteanu-Malinici, I.; Bhoj, V.; Landsburg, D.; et al. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells in Refractory B-Cell Lymphomas. N Engl J Med 2017, 377, 2545–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sehn, L.H.; Berry, B.; Chhanabhai, M.; Fitzgerald, C.; Gill, K.; Hoskins, P.; Klasa, R.; Savage, K.J.; Shenkier, T.; Sutherland, J.; et al. The revised International Prognostic Index (R-IPI) is a better predictor of outcome than the standard IPI for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. Blood 2007, 109, 1857–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipani, M.; Rivolta, G.M.; Margiotta-Casaluci, G.; Mahmoud, A.M.; Al Essa, W.; Gaidano, G.; Bruna, R. New Frontiers in Monoclonal Antibodies for Relapsed/Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morton, L.M.; Wang, S.S.; Devesa, S.S.; Hartge, P.; Weisenburger, D.D.; Linet, M.S. Lymphoma incidence patterns by WHO subtype in the United States, 1992-2001. Blood 2006, 107, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorostkar, H.; Haghiralsadat, B.F.; Hemati, M.; Safari, F.; Hassanpour, A.; Naghib, S.M.; Roozbahani, M.H.; Mozafari, M.R.; Moradi, A. Reduction of Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity by Co-Administration of Smart Liposomal Doxorubicin and Free Quercetin: In Vitro and In Vivo Studies. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehelgerdi, M.; Chehelgerdi, M.; Allela, O.Q.B.; Pecho, R.D.C.; Jayasankar, N.; Rao, D.P.; Thamaraikani, T.; Vasanthan, M.; Viktor, P.; Lakshmaiya, N.; et al. Progressing nanotechnology to improve targeted cancer treatment: overcoming hurdles in its clinical implementation. Mol Cancer 2023, 22, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Liu, H.; Ye, Y.; Lei, Y.; Islam, R.; Tan, S.; Tong, R.; Miao, Y.B.; Cai, L. Smart nanoparticles for cancer therapy. Signal transduction and targeted therapy 2023, 8, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, S.; Park, S.; Park, H.; Park, C.; Kim, W.C.; Thakur, D.; Won, Y.J.; Key, J. Clinical Trials for Oral, Inhaled and Intravenous Drug Delivery System for Lung Cancer and Emerging Nanomedicine-Based Approaches. International journal of nanomedicine 2023, 18, 7865–7888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.Y.; Hsieh, Y.S.; Wu, Y.T. Poly (Lactic-Co-Glycolic) Acid-Poly (Vinyl Pyrrolidone) Hybrid Nanoparticles to Improve the Efficiency of Oral Delivery of β-Carotene. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Xiong, Z.A.; Qin, Q.; Yao, C.G.; Zhao, X.Z. Picosecond pulsed electric fields induce apoptosis in a cervical cancer xenograft. Molecular medicine reports 2015, 11, 1623–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fessi, H.; Puisieux, F.; Devissaguet, J.P.; Ammoury, N.; Benita, S. NANOCAPSULE FORMATION BY INTERFACIAL POLYMER DEPOSITION FOLLOWING SOLVENT DISPLACEMENT. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 1989, 55, R1–R4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).