Submitted:

29 May 2025

Posted:

30 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Device Design

3. Device Fabrication and Material Characterization

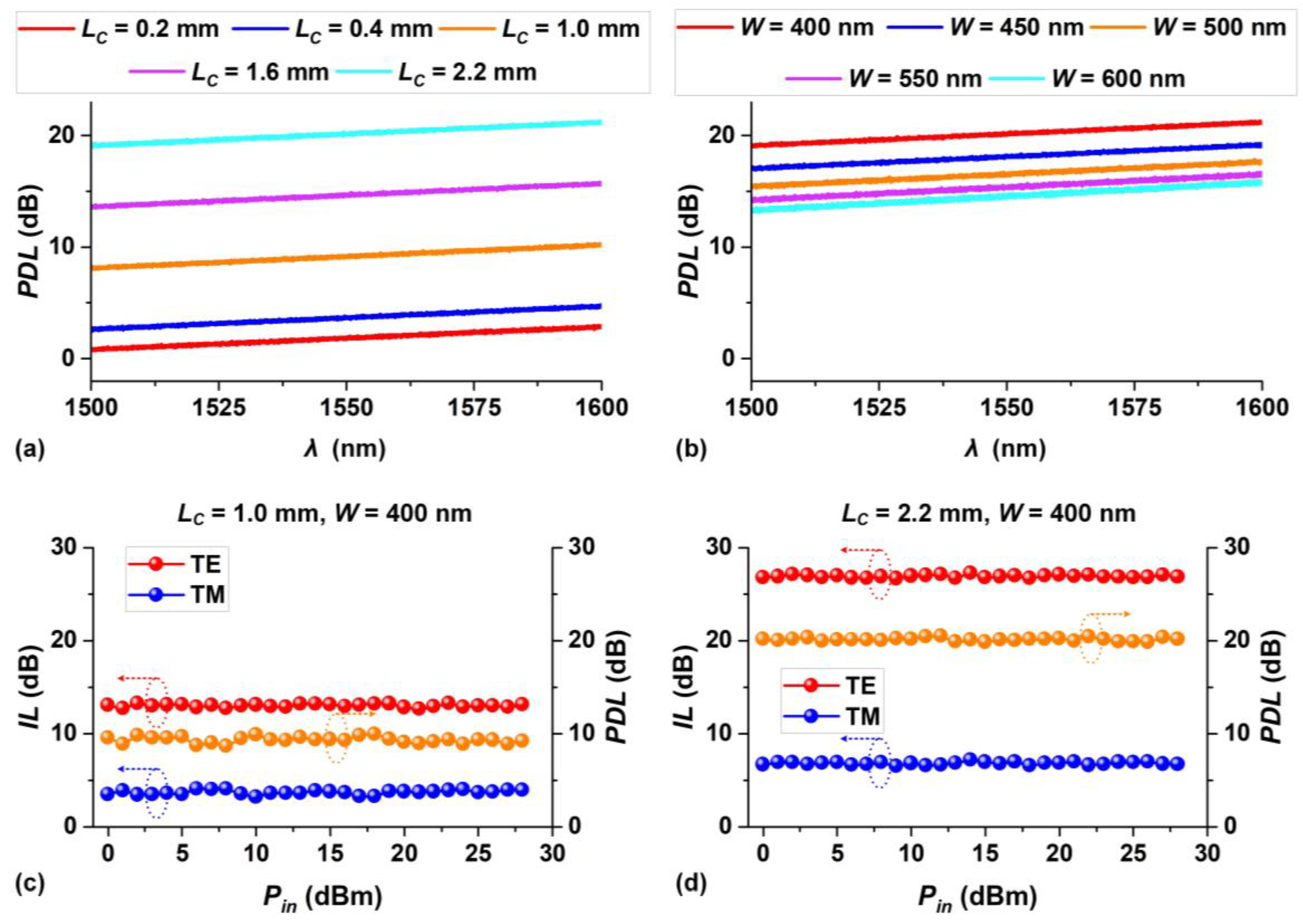

4. Polarization-Dependent Loss Measurements

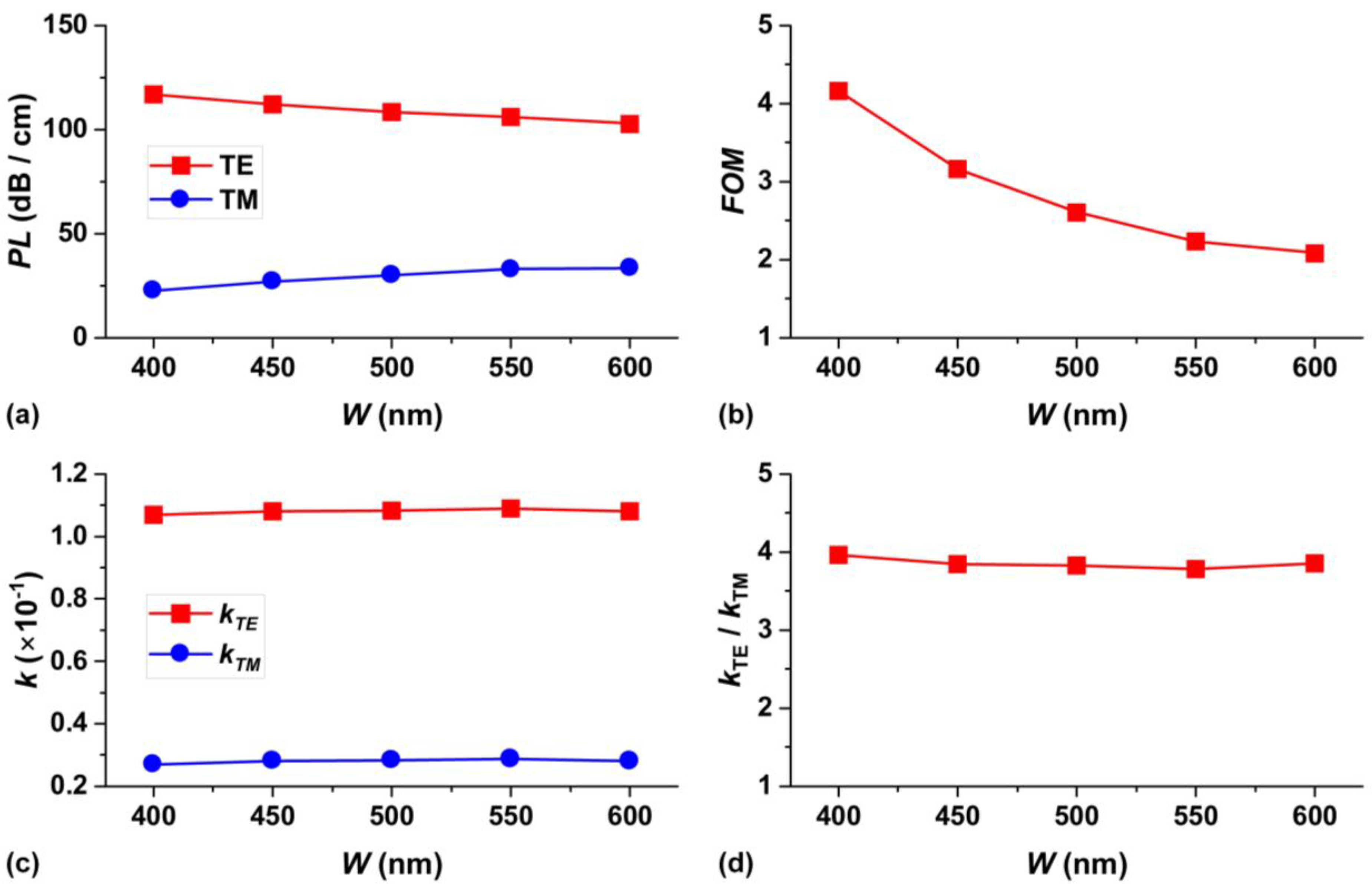

5. Discussion

6. Concluson

References

- Bao, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wang, B.; Ni, Z.; Lim, C.H.Y.X.; Wang, Y.; Tang, D.Y.; Loh, K.P. Broadband graphene polarizer. Nature Photonics 2011, 5, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Xie, G.; Lavery, M.P.J.; Huang, H.; Ahmed, N.; Bao, C.; Ren, Y.; Cao, Y.; Li, L.; Zhao, Z.; Molisch, A.F.; Tur, M.; Padgett, M.J.; Willner, A.E. High-capacity millimetre-wave communications with orbital angular momentum multiplexing. Nature Communications 2014, 5, 4876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, D.; Liu, L.; Gao, S.; Xu, D.-X.; He, S. Polarization management for silicon photonic integrated circuits. Laser & Photonics Reviews 2013, 7, 303–328. [Google Scholar]

- Serkowski, K.; Mathewson, D.S.; Ford, V.L. Wavelength dependence of interstellar polarization and ratio of total to selective extinction. The Astrophysical Journal 1975, 196, 261–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.J.; He, Q.Y.; Gao, J.Y.; Jiang, Y.; Kang, Z.H.; Sun, H.; Yu, L.S.; Yuan, X.F.; Wu, J. Efficient electrooptically Q-switched Er:Cr:YSGG laser oscillator-amplifier system with a Glan-Taylor prism polarizer. Laser Physics 2006, 16, 1605–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitoh, E.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Saitoh, K.; Koshiba, M. TE/TM-Pass Polarizer Based on Lithium Niobate on Insulator Ridge Waveguide. IEEE Photonics Journal 2013, 5, 6600610–6600610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahnama, A.; Dadalyan, T.; Aghdami, K.M.; Galstian, T.; Herman, P.R. In-Fiber Switchable Polarization Filter Based on Liquid Crystal Filled Hollow-Filament Bragg Gratings. Advanced Optical Materials 2021, 9, 2100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, J.-Y.; Fazal, I.M.; Ahmed, N.; Yan, Y.; Huang, H.; Ren, Y.; Yue, Y.; Dolinar, S.; Tur, M.; Willner, A.E. Terabit free-space data transmission employing orbital angular momentum multiplexing. Nature Photonics 2012, 6, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozinovic, N.; Yue, Y.; Ren, Y.; Tur, M.; Kristensen, P.; Huang, H.; Willner, A.E.; Ramachandran, S. Terabit-Scale Orbital Angular Momentum Mode Division Multiplexing in Fibers. Science 2013, 340, 1545–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.; Wang, Z.; Julian, N.; Bowers, J.E. Compact broadband polarizer based on shallowly-etched silicon-on-insulator ridge optical waveguides. Optics Express 2010, 18, 27404–27415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, H.; Liow, T.-Y.; Lo, G.-Q. CMOS compatible horizontal nanoplasmonic slot waveguides TE-pass polarizer on silicon-on-insulator platform. Optics Express 2013, 21, 12790–12796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Liu, Y.; Lin, L.; Li, S.; Cai, J.; Chen, J.; Huang, W.; Lin, Y.; Xu, J. Chromatic Plasmonic Polarizer-Based Synapse for All-Optical Convolutional Neural Network. Nano Letters 2023, 23, 9651–9656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wen, S.; Deng, Z.-L.; Li, X.; Yang, Y. Metasurface-Based Solid Poincaré Sphere Polarizer. Physical Review Letters 2023, 130, 123801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.; Song, Y.; Huang, Y.; Kita, D.; Deckoff-Jones, S.; Wang, K.; Li, L.; Li, J.; Zheng, H.; Luo, Z.; Wang, H.; Novak, S.; Yadav, A.; Huang, C.-C.; Shiue, R.-J.; Englund, D.; Gu, T.; Hewak, D.; Richardson, K.; Kong, J.; Hu, J. Chalcogenide glass-on-graphene photonics. Nature Photonics 2017, 11, 798–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.T.; Choi, H. Polarization Control in Graphene-Based Polymer Waveguide Polarizer. Laser & Photonics Reviews 2018, 12, 1800142. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.T.; Choi, C.-G. Graphene-based polymer waveguide polarizer. Optics Express 2012, 20, 3556–3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yang, Y.; Qu, Y.; Xu, X.; Liang, Y.; Chu, S.T.; Little, B.E.; Morandotti, R.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. Graphene Oxide Waveguide and Micro-Ring Resonator Polarizers. Laser & Photonics Reviews 2019, 13, 1900056. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, D.; Wu, J.; Hu, J.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Jia, L.; Huang, D.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. Silicon photonic waveguide and microring resonator polarizers incorporating 2D graphene oxide films. Applied Physics Letters 2024, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.H.; Yap, Y.K.; Chong, W.Y.; Pua, C.H.; Huang, N.M.; De La Rue, R.M.; Ahmad, H. Graphene oxide-based waveguide polariser: From thin film to quasi-bulk. Optics Express 2014, 22, 11090–11098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, L.; Li, D.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Lin, Z.; Zheng, H.; Zhu, W.; Zhong, Y.; Tang, J.; Lu, G.; Fang, W.; Yu, J.; Chen, Z. High performance multifunction-in-one optoelectronic device by integrating graphene/MoS2 heterostructures on side-polished fiber. Nanophotonics 2022, 11, 1137–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; He, R.; Cheng, C.; Wang, D.; Chen, Y.; Chen, F. Polarization-dependent optical absorption of MoS2 for refractive index sensing. Scientific Reports 2014, 4, 7523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathiyan, S.; Ahmad, H.; Chong, W.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Sivabalan, S. Evolution of the Polarizing Effect of MoS2. IEEE Photonics Journal 2015, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.H.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Kis, A.; Coleman, J.N.; Strano, M.S. Electronics and optoelectronics of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nature Nanotechnology 2012, 7, 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, F.; Wang, H.; Xiao, D.; Dubey, M.; Ramasubramaniam, A. Two-dimensional material nanophotonics. Nature Photonics 2014, 8, 899–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chee, S.-S.; Seo, D.; Kim, H.; Jang, H.; Lee, S.; Moon, S.P.; Lee, K.H.; Kim, S.W.; Choi, H.; Ham, M.-H. Lowering the Schottky Barrier Height by Graphene/Ag Electrodes for High-Mobility MoS2 Field-Effect Transistors. Advanced Materials 2019, 31, 1804422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radisavljevic, B.; Radenovic, A.; Brivio, J.; Giacometti, V.; Kis, A. Single-layer MoS2 transistors. Nature Nanotechnology 2011, 6, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Ling, C.; Xu, T.; Wang, W.; Niu, X.; Zafar, A.; Yan, Z.; Wang, X.; You, Y.; Sun, L.; Lu, J.; Wang, J.; Ni, Z. Defect Engineering for Modulating the Trap States in 2D Photoconductors. Advanced Materials 2018, 30, 1804332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Sanchez, O.; Lembke, D.; Kayci, M.; Radenovic, A.; Kis, A. Ultrasensitive photodetectors based on monolayer MoS2. Nature Nanotechnology 2013, 8, 497–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasani, A.; Tekalgne, M.; Le, Q.V.; Jang, H.W.; Kim, S.Y. Two-dimensional materials as catalysts for solar fuels: hydrogen evolution reaction and CO2 reduction. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2019, 7, 430–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, M.; Kim, K.; Liu, C.; Addepalli, A.V.; Abbasi, P.; Yasaei, P.; Phillips, P.; Behranginia, A.; Cerrato, J.M.; Haasch, R.; Zapol, P.; Kumar, B.; Klie, R.F.; Abiade, J.; Curtiss, L.A.; Salehi-Khojin, A. Nanostructured transition metal dichalcogenide electrocatalysts for CO<sub>2</sub> reduction in ionic liquid. Science 2016, 353, 467–470. [Google Scholar]

- Presolski, S.; Pumera, M. Covalent functionalization of MoS2. Materials Today 2016, 19, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.-M.; Kvashnin, D.G.; Najmaei, S.; Bando, Y.; Kimoto, K.; Koskinen, P.; Ajayan, P.M.; Yakobson, B.I.; Sorokin, P.B.; Lou, J.; Golberg, D. Nanomechanical cleavage of molybdenum disulphide atomic layers. Nature Communications 2014, 5, 3631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mak, K.F.; Lee, C.; Hone, J.; Shan, J.; Heinz, T.F. Atomically Thin MoS2: A New Direct-Gap Semiconductor. Physical Review Letters 2010, 105, 136805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abidi, I.H.; Giridhar, S.P.; Tollerud, J.O.; Limb, J.; Waqar, M.; Mazumder, A.; Mayes, E.L.; Murdoch, B.J.; Xu, C.; Bhoriya, A.; Ranjan, A.; Ahmed, T.; Li, Y.; Davis, J.A.; Bentley, C.L.; Russo, S.P.; Gaspera, E.D.; Walia, S. Oxygen Driven Defect Engineering of Monolayer MoS2 for Tunable Electronic, Optoelectronic, and Electrochemical Devices. Advanced Functional Materials 2024, 34, 2402402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidi, I.H.; Bhoriya, A.; Vashishtha, P.; Giridhar, S.P.; Mayes, E.L.H.; Sehrawat, M.; Verma, A.K.; Aggarwal, V.; Gupta, T.; Singh, H.K.; Ahmed, T.; Sharma, N.D.; Walia, S. Oxidation-induced modulation of photoresponsivity in monolayer MoS2 with sulfur vacancies. Nanoscale 2024, 16, 19834–19843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, K.M.; Synowicki, R.; Ismael, T.; Oguntoye, I.; Grinalds, N.; Escarra, M.D. In-Plane and Out-of-Plane Optical Properties of Monolayer, Few-Layer, and Thin-Film MoS2 from 190 to 1700 nm and Their Application in Photonic Device Design. Advanced Photonics Research 2021, 2, 2000180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermolaev, G.A.; Grudinin, D.V.; Stebunov, Y.V.; Voronin, K.V.; Kravets, V.G.; Duan, J.; Mazitov, A.B.; Tselikov, G.I.; Bylinkin, A.; Yakubovsky, D.I.; Novikov, S.M.; Baranov, D.G.; Nikitin, A.Y.; Kruglov, I.A.; Shegai, T.; Alonso-González, P.; Grigorenko, A.N.; Arsenin, A.V.; Novoselov, K.S.; Volkov, V.S. Giant optical anisotropy in transition metal dichalcogenides for next-generation photonics. Nature Communications 2021, 12, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Cong, H.; Zhang, B.; Wei, W.; Liang, Y.; Fang, S.; Wang, T.; Zhang, J. Enhanced optical Kerr nonlinearity of graphene/Si hybrid waveguide. Applied Physics Letters 2019, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Huang, Q.; Xia, J.; Barille, R.; Wang, Y. Enhanced linear absorption coefficient of in-plane monolayer graphene on a silicon microring resonator. Optics Express 2016, 24, 24105–24116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martella, C.; Mennucci, C.; Cinquanta, E.; Lamperti, A.; Cappelluti, E.; de Mongeot, F.B.; Molle, A. Anisotropic MoS2 Nanosheets Grown on Self-Organized Nanopatterned Substrates. Advanced Materials 2017, 29, 1605785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, G.-H.; He, Q.; Wang, X.; Yu, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, K.; Yang, Z.; Hu, D.; Lai, Z.; Li, B.; Xiong, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Gu, L.; Zhang, H. In-Plane Anisotropic Properties of 1T′-MoS2 Layers. Advanced Materials 2019, 31, 1807764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Jia, L.; Jin, D.; Jia, B.; Hu, X.; Moss, D.; Gong, Q. Advanced optical polarizers based on 2D materials. npj Nanophotonics 2024, 1, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Qu, Y.; Jia, B.; Chen, Z.; Moss, D.J. Fabrication Technologies for the On-Chip Integration of 2D Materials. Small Methods 2022, 6, 2101435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurarslan, A.; Yu, Y.; Su, L.; Yu, Y.; Suarez, F.; Yao, S.; Zhu, Y.; Ozturk, M.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, L. Surface-Energy-Assisted Perfect Transfer of Centimeter-Scale Monolayer and Few-Layer MoS2 Films onto Arbitrary Substrates. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 11522–11528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkin, W.M.; Balan, A.; Liang, L.; Das, P.M.; Lamparski, M.; Naylor, C.H.; Rodríguez-Manzo, J.A.; Johnson, A.T.C.; Meunier, V.; Drndić, M. Raman Shifts in Electron-Irradiated Monolayer MoS2. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 4134–4142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yu, H.; Chen, W.; Tian, X.; Liu, D.; Cheng, M.; Xie, G.; Yang, W.; Yang, R.; Bai, X.; Shi, D.; Zhang, G. Scalable Growth of High-Quality Polycrystalline MoS2 Monolayers on SiO2 with Tunable Grain Sizes. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 6024–6030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britnell, L.; Ribeiro, R.M.; Eckmann, A.; Jalil, R.; Belle, B.D.; Mishchenko, A.; Kim, Y.-J.; Gorbachev, R.V.; Georgiou, T.; Morozov, S.V.; Grigorenko, A.N.; Geim, A.K.; Casiraghi, C.; Neto, A.H.C.; Novoselov, K.S. Strong Light-Matter Interactions in Heterostructures of Atomically Thin Films. Science 2013, 340, 1311–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumcenco, D.; Ovchinnikov, D.; Marinov, K.; Lazić, P.; Gibertini, M.; Marzari, N.; Sanchez, O.L.; Kung, Y.-C.; Krasnozhon, D.; Chen, M.-W.; Bertolazzi, S.; Gillet, P.; Morral, A.F.I.; Radenovic, A.; Kis, A. Large-Area Epitaxial Monolayer MoS2. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 4611–4620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsberg, V.; Zhang, R.; Bäckström, J.; Dahlström, C.; Andres, B.; Norgren, M.; Andersson, M.; Hummelgård, M.; Olin, H. Exfoliated MoS2 in Water without Additives. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0154522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, T.; Hu, G.; Xu, C.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, Y. Controllable synthesis of self-assembled MoS2 hollow spheres for photocatalytic application. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics 2018, 29, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Su, D.; Zhou, R.; Sun, B.; Wang, G.; Qiao, S.Z. Highly Ordered Mesoporous MoS2 with Expanded Spacing of the (002) Crystal Plane for Ultrafast Lithium Ion Storage. Advanced Energy Materials 2012, 2, 970–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeramalai, C.P.; Li, F.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Guo, T.; Kim, T.W. Enhanced field emission properties of molybdenum disulphide few layer nanosheets synthesized by hydrothermal method. Applied Surface Science 2016, 389, 1017–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, H.; Wang, Z.; Wang, W.; Liang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Chen, Q.; He, D.; Tan, P.; Miao, F.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Ni, Z. Strong Photoluminescence Enhancement of MoS2 through Defect Engineering and Oxygen Bonding. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 5738–5745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chee, S.-S.; Lee, W.-J.; Jo, Y.-R.; Cho, M.K.; Chun, D.; Baik, H.; Kim, B.-J.; Yoon, M.-H.; Lee, K.; Ham, M.-H. Atomic Vacancy Control and Elemental Substitution in a Monolayer Molybdenum Disulfide for High Performance Optoelectronic Device Arrays. Advanced Functional Materials 2020, 30, 1908147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Arévalo, N.; Al Shuhaib, J.H.; Pacheco, R.B.; Marchiani, D.; Abdelnabi, M.M.S.; Frisenda, R.; Sbroscia, M.; Betti, M.G.; Mariani, C.; Manzanares-Negro, Y.; Navarro, C.G.; Martínez-Galera, A.J.; Ares, J.R.; Ferrer, I.J.; Leardini, F. MoS2 Photoelectrodes for Hydrogen Production: Tuning the S-Vacancy Content in Highly Homogeneous Ultrathin Nanocrystals. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2023, 15, 33514–33524. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, D.; Bauters, J.; Bowers, J.E. Passive technologies for future large-scale photonic integrated circuits on silicon: polarization handling, light non-reciprocity and loss reduction. Light: Science & Applications 2012, 1, e1. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, J.; Yang, Y.; Jin, D.; Liu, W.; Huang, D.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. 2D graphene oxide films expand functionality of photonic chips. Advanced Materials 2024, 2403659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tao, L.; Yi, D.; Xu, J.-B.; Tsang, H.K. Enhanced thermo-optic nonlinearities in a MoS2-on-silicon microring resonator. Applied Physics Express 2020, 13, 022004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Anugrah, Y.; Koester, S.J.; Li, M. Optical absorption in graphene integrated on silicon waveguides. Applied Physics Letters 2012, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Yang, Y.; Qu, Y.; Jia, L.; Moein, T.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. Enhanced Kerr Nonlinearity and Nonlinear Figure of Merit in Silicon Nanowires Integrated with 2D Graphene Oxide Films. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2020, 12, 33094–33103. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, C.; Yang, L.; Wang, G.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Hao, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, J. Broadband Graphene/Glass Hybrid Waveguide Polarizer. IEEE Photonics Technology Letters 2015, 27, 927–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Wu, J.; Jin, D.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Jia, L.; Wang, Y.; Huang, D.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. Integrated photonic polarizers with 2D reduced graphene oxide. Opto-Electronic Science 2025, 240032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickman, A. The commercialization of silicon photonics. Nature Photonics 2014, 8, 579–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuthold, J.; Koos, C.; Freude, W. Nonlinear silicon photonics. Nature Photonics 2010, 4, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, D.J.; Morandotti, R.; Gaeta, A.L.; Lipson, M. New CMOS-compatible platforms based on silicon nitride and Hydex for nonlinear optics. Nature Photonics 2013, 7, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzari, L.; et al. CMOS-compatible integrated optical hyper-parametric oscillator. Nature Photonics 2010, 4, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquazi, A.; et al. Sub-picosecond phase-sensitive optical pulse characterization on a chip. Nature Photonics 2011, 5, 618–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrera, M.; et al. On-Chip ultra-fast 1st and 2nd order CMOS compatible all-optical integration. Optics Express 2011, 19, 23153–23161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, C.; et al. Direct soliton generation in microresonators. Opt. Lett 2017, 42, 2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrera, M.; et al. CMOS compatible integrated all-optical RF spectrum analyzer. Optics Express 2014, 22, 21488–21498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kues, M.; et al. Passively modelocked laser with an ultra-narrow spectral width. Nature Photonics 2017, 11, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrera, M.; et al. Low-power continuous-wave nonlinear optics in doped silica glass integrated waveguide structures. Nature Photonics 2008, 2, 737–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrera, M.; et al. On-Chip ultra-fast 1st and 2nd order CMOS compatible all-optical integration. Opt. Express 2011, 19, 23153–23161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchesne, D.; Peccianti, M.; Lamont, M.R.E.; et al. Supercontinuum generation in a high index doped silica glass spiral waveguide. Optics Express 2010, 18, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, H.; Olivieri, L.; Rowley, M.; Chu, S.T.; Little, B.E.; Morandotti, R.; Moss, D.J.; et al. Turing patterns in a fiber laser with a nested microresonator: Robust and controllable microcomb generation. Physical Review Research 2020, 2, 023395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrera, M.; et al. On-chip CMOS-compatible all-optical integrator. Nature Communications 2010, 1, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasquazi, A.; et al. All-optical wavelength conversion in an integrated ring resonator. Optics Express 2010, 18, 3858–3863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasquazi; Park, Y. ; Azana, J.; et al. Efficient wavelength conversion and net parametric gain via Four Wave Mixing in a high index doped silica waveguide. Optics Express 2010, 18, 7634–7641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peccianti; Ferrera, M. ; Razzari, L.; et al. Subpicosecond optical pulse compression via an integrated nonlinear chirper. Optics Express 2010, 18, 7625–7633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrera, M.; Park, Y.; Razzari, L.; Little, B.E.; Chu, S.T.; Morandotti, R.; Moss, D.J.; et al. All-optical 1st and 2nd order integration on a chip. Optics Express 2011, 19, 23153–23161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrera, M.; et al. Low Power CW Parametric Mixing in a Low Dispersion High Index Doped Silica Glass Micro-Ring Resonator with Q-factor > 1 Million. Optics Express 2009, 17, 14098–14103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peccianti, M.; et al. Demonstration of an ultrafast nonlinear microcavity modelocked laser. Nature Communications 2012, 3, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasquazi, A.; et al. Self-locked optical parametric oscillation in a CMOS compatible microring resonator: a route to robust optical frequency comb generation on a chip. Optics Express 2013, 21, 13333–13341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasquazi, A.; et al. Stable, dual mode, high repetition rate mode-locked laser based on a microring resonator. Optics Express 2012, 20, 27355–27362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquazi, A.; et al. Micro-combs: a novel generation of optical sources. Physics Reports 2018, 729, 1–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, H.; et al. Laser cavity-soliton microcombs. Nature Photonics 2019, 13, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutrona, A.; Rowley, M.; Das, D.; Olivieri, L.; Peters, L.; Chu, S.T.; Little, B.L.; Morandotti, R.; Moss, D.J.; Gongora, J.S.T.; Peccianti, M.; Pasquazi, A. High Conversion Efficiency in Laser Cavity-Soliton Microcombs. Optics Express 2022, 30, 39816–39825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutrona, A.; Rowley, M.; Bendahmane, A.; Cecconi, V.; Olivieri, L.; Little, B.E.; Chu, S.T.; Stivala, S.; Morandotti, R.; Moss, D.J.; Totero-Gongora, J.S.; Peccianti, M.; Pasquazi, A. Nonlocal bonding of a soliton and a blue-detuned state in a microcomb laser. Nature Communications Physics 2023, 6, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, A.A.; Alamgir, I.; Di Lauro, L.; Fischer, B.; Perron, N.; Dmitriev, P.; Mazoukh, C.; Roztocki, P.; Rimoldi, C.; Chemnitz, M.; Eshaghi, A.; Viktorov, E.A.; Kovalev, A.V.; Little, B.E.; Chu, S.T.; Moss, D.J.; Morandotti, R. Mode-locked laser with multiple timescales in a microresonator-based nested cavity. APL Photonics 2024, 9, 031302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A.; Olivieri, L.; Cutrona, A.; Das, D.; Peters, L.; Chu, S.T.; Little, B.; Morandotti, R.; Moss, D.J.; Peccianti, M.; Pasquazi, A. Parametric interaction of laser cavity-solitons with an external CW pump. Optics Express 2024, 32, 21783–21794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutrona, A.; Rowley, M.; Bendahmane, A.; Cecconi, V.; Olivieri, L.; Little, B.E.; Chu, S.T.; Stivala, S.; Morandotti, R.; Moss, D.J.; Totero-Gongora, J.S.; Peccianti, M.; Pasquazi, A. Stability Properties of Laser Cavity-Solitons for Metrological Applications. Applied Physics Letters 2023, 122, 121104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.E.; Tan, M.; Prayoonyong, C.; Chu, S.T.; Little, B.E.; Morandotti, R.; Mitchell, A.; Moss, D.J.; Corcoran, B. Investigating the thermal robustness of soliton crystal microcombs. Optics Express 2023, 31, 37749–37762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Salamy, J.; Murry, C.E.; Little, B.E.; Chu, S.T.; Morandotti, R.; Mitchell, A.; Moss, D.J.; Corcoran, B. Enhancing laser temperature stability by passive self-injection locking to a micro-ring resonator. Optics Express 2024, 32, 23841–23855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Salamy, J.; Murray, C.E.; Zhu, X.; Little, B.E.; Morandotti, R.; Mitchell, A.; Chu, S.T.; Moss, D.J.; Corcoran, B. Self-locking of free-running DFB lasers to a single microring resonator for dense WDM. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2025, 43, 1995–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wu, J.; Shoeiby, M.; Nguyen, T.G.; Chu, S.T.; Little, B.E.; Morandotti, R.; Mitchell, A.; Moss, D.J. Reconfigurable broadband microwave photonic intensity differentiator based on an integrated optical frequency comb source. APL Photonics 2017, 2, 096104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; et al. Photonic microwave true time delays for phased array antennas using a 49 GHz FSR integrated micro-comb source. Photonics Research 2018, 6, B30–B36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Tan, M.; Wu, J.; Morandotti, R.; Mitchell, A.; Moss, D.J. Microcomb-based photonic RF signal processing. IEEE Photonics Technology Letters 2019, 31, 1854–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; et al. Advanced adaptive photonic RF filters with 80 taps based on an integrated optical micro-comb source. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2019, 37, 1288–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; et al. Photonic RF and microwave integrator with soliton crystal microcombs. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems II: Express Briefs 2020, 67, 3582–3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; et al. High performance RF filters via bandwidth scaling with Kerr micro-combs. APL Photonics 2019, 4, 026102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; et al. Microwave and RF photonic fractional Hilbert transformer based on a 50 GHz Kerr micro-comb. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2019, 37, 6097–6104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; et al. RF and microwave fractional differentiator based on photonics. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems: Express Briefs 2020, 67, 2767–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; et al. Photonic RF arbitrary waveform generator based on a soliton crystal micro-comb source. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2020, 38, 6221–6226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Xu, X.; Wu, J.; Morandotti, R.; Mitchell, A.; Moss, D.J. RF and microwave high bandwidth signal processing based on Kerr Micro-combs. Advances in Physics X 2021, 6, 1838946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; et al. Advanced RF and microwave functions based on an integrated optical frequency comb source. Opt. Express 2018, 26, 2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Xu, X.; Wu, J.; Corcoran, B.; Boes, A.; Nguyen, T.G.; Chu, S.T.; Little, B.E.; Morandotti, R.; Lowery, A.; Mitchell, A.; Moss, D.J. Highly Versatile Broadband RF Photonic Fractional Hilbert Transformer Based on a Kerr Soliton Crystal Microcomb. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2021, 39, 7581–7587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- et al. RF Photonics: An Optical Microcombs’ Perspective. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics 2018, 24, 6101020. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.G.; et al. Integrated frequency comb source-based Hilbert transformer for wideband microwave photonic phase analysis. Opt. Express 2015, 23, 22087–22097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; et al. Broadband RF channelizer based on an integrated optical frequency Kerr comb source. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2018, 36, 4519–4526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; et al. Continuously tunable orthogonally polarized RF optical single sideband generator based on micro-ring resonators. Journal of Optics 2018, 20, 115701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; et al. Orthogonally polarized RF optical single sideband generation and dual-channel equalization based on an integrated microring resonator. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2018, 36, 4808–4818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; et al. Photonic RF phase-encoded signal generation with a microcomb source. J. Lightwave Technology 2020, 38, 1722–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; et al. Broadband microwave frequency conversion based on an integrated optical micro-comb source. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2020, 38, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; et al. Photonic RF and microwave filters based on 49GHz and 200GHz Kerr microcombs. Optics Comm. 2020, 465, 125563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; et al. Broadband photonic RF channelizer with 90 channels based on a soliton crystal microcomb. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2020, 38, 5116–5121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; et al. Orthogonally polarized Photonic Radio Frequency single sideband generation with integrated micro-ring resonators. IOP Journal of Semiconductors 2021, 42, 041305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Xu, X.; Wu, J.; Nguyen, T.G.; Chu, S.T.; Little, B.E.; Morandotti, R.; Mitchell, A.; Moss, D.J. Photonic Radio Frequency Channelizers based on Kerr Optical Micro-combs. IOP Journal of Semiconductors 2021, 42, 041302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, B.; et al. Ultra-dense optical data transmission over standard fiber with a single chip source. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; et al. Photonic perceptron based on a Kerr microcomb for scalable high speed optical neural networks. Laser and Photonics Reviews 2020, 14, 2000070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; et al. 11 TOPs photonic convolutional accelerator for optical neural networks. Nature 2021, 589, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Han, W.; Tan, M.; Sun, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, J.; Morandotti, R.; Mitchell, A.; Xu, K.; Moss, D.J. Neuromorphic computing based on wavelength-division multiplexing. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics 2023, 29, 7400112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Xu, X.; Tan, M.; Sun, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, J.; Morandotti, R.; Mitchell, A.; Xu, K.; Moss, D.J. Photonic multiplexing techniques for neuromorphic computing. Nanophotonics 2023, 12, 795–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayoonyong, C.; Boes, A.; Xu, X.; Tan, M.; Chu, S.T.; Little, B.E.; Morandotti, R.; Mitchell, A.; Moss, D.J.; Corcoran, B. Frequency comb distillation for optical superchannel transmission. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2021, 39, 7383–7392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Xu, X.; Wu, J.; Corcoran, B.; Boes, A.; Nguyen, T.G.; Chu, S.T.; Little, B.E.; Morandotti, R.; Mitchell, A.; Moss, D.J. Integral order photonic RF signal processors based on a soliton crystal micro-comb source. IOP Journal of Optics 2021, 23, 125701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wu, J.; Li, Y.; Xu, X.; Ren, G.; Tan, M.; Chu, S.T.; Little, B.E.; Morandotti, R.; Mitchell, A.; Moss, D.J. Optimizing the performance of microcomb based microwave photonic transversal signal processors. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2023, 41, 7223–7237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Xu, X.; Boes, A.; Corcoran, B.; Nguyen, T.G.; Chu, S.T.; Little, B.E.; Morandotti, R.; Wu, J.; Mitchell, A.; Moss, D.J. Photonic signal processor for real-time video image processing based on a Kerr microcomb. Nature Communications Engineering 2023, 2, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Xu, X.; Wu, J.; Morandotti, R.; Mitchell, A.; Moss, D.J. Photonic RF and microwave filters based on 49GHz and 200GHz Kerr microcombs. Optics Communications 2020, 465, 125563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wu, J.; Li, Y.; Tan, M.; Xu, X.; Chu, S.; Little, B.; Morandotti, R.; Mitchell, A.; Moss, D.J. Quantifying the Accuracy of Microcomb-based Photonic RF Transversal Signal Processors. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics 2023, 29, 7500317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wu, J.; Ren, G.; Corcoran, B.; Xu, X.; Chu, S.T.; Little, B.E.; Morandotti, R.; Mitchell, A.; Moss, D.J. Processing accuracy of microcomb-based microwave photonic signal processors for different input signal waveforms. MDPI Photonics 2023, 10, 10111283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wu, J.; Li, Y.; Moss, D.J. Comparison of microcomb-based RF photonic transversal signal processors implemented with discrete components versus integrated chips. MDPI Micromachines 2023, 14, 1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Moss, D.J. The laser trick that could put an ultraprecise optical clock on a chip. Nature 2023, 624, 256–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, W.; Liu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Tan, M.; Huang, C.; Wu, J.; Xu, K.; Moss, D.J.; Xu, X. Photonic RF Channelization Based on Microcombs. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics 2024, 30, 7600417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wu, J.; Ren, G.; Xu, X.; Tan, M.; Chu, S.; Little, B.; Morandotti, R.; Mitchell, A.; Moss, D. Feedback control in micro-comb-based microwave photonic transversal filter systems. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics 2024, 30, 2900117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Liu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Tan, M.; Li, Y.; Zhu, X.; Ou, Y.; Yin, F.; Morandotti, R.; Little, B.E.; Chu, S.T.; Xu, X.; Moss, D.J.; Xu, K. Dual-polarization RF Channelizer Based on Microcombs. Optics Express 2024, 32, 11281–11295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Song, Y.; Zhu, X.; Bai, Y.; Tan, M.; Corcoran, B.; Murphy, C.; Chu, S.T.; Moss, D.J.; Xu, X.; Xu, K. Advances in Soliton Crystals Microcombs. Photonics 2024, 11, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazoukh, C.; Di Lauro, L.; Alamgir, I.; Aadhi, A.; Eshaghi, A.; Little, B.E.; Chu, S.T.; Moss, D.J.; Morandotti, R. Genetic algorithm-enhanced microcomb state generation. Nature Communications Physics 2024, 7, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zheng, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, X.; Huang, S.; Wang, S.; Xu, X.; Xia, C.; Liu, Z.; Huang, C.; Morandotti, R.; Chu, S.T.; Little, B.E.; Corcoran, B.; Liu, Y.; Bai, Y.; Moss, D.J.; Xu, X.; Xu, K. High-bit-efficiency TOPS optical tensor convolutional accelerator using micro-combs. Laser & Photonics Reviews 2025, 19, 2401975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Liu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Tan, M.; Li, Y.; Zhu, X.; Ou, Y.; Yin, F.; Morandotti, R.; Little, B.E.; Chu, S.T.; Moss, D.J.; Xu, X.; Xu, K. TOPS-speed complex-valued convolutional accelerator for feature extraction and inference. Nature Communications 2025, 16, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wu, J.; Ren, G.; Morandotti, R.; Xu, X.; Tan, M.; Mitchell, A.; Moss, D.J. Performance analysis of microwave photonic spectral filters based on optical microcombs. Advanced Physics Research 2025, 4, 2400084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- di Lauro, L.; Sciara, S.; Fischer, B.; Dong, J.; Alamgir, I.; Wetzel, B.; Genty, G.; Nichols, M.; Eshaghi, A.; Moss, D.J.; Morandotti, R. Optimization Methods for Integrated and Programmable Photonics in Next-Generation Classical and Quantum Smart Communication and Signal Processing. Advances in Optics and Photonics 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, B.; Mitchell, A.; Morandotti, R.; Oxenlowe, L.K.; Moss, D.J. Optical microcombs for ultrahigh-bandwidth communications. Nature Photonics 2025, 19, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Q.; Tan, M.; Feng, H.; Yang, X.; Xu, X.; Morandotti, R.; Mitchell, A.; Su, D.; Moss, D.J. Photonic real-time signal processing. Nanophotonics 2025, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Wang, J.; Zhu, X.; Xu, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhang, H.; Li, S.; Bai, Y.; Liu, Z.; Morandotti, R.; Little, B.E.; Lowery, A.J.; Moss, D.J.; Chu, S.T.; Xu, K. Microcomb-enabled parallel self- calibration optical convolution streaming processor. Light Science and Applications 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Zheng, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, X.; Huang, S.; Wang, S.; Xu, X.; Xia, C.; Liu, Z.; Huang, C.; Morandotti, R.; Chu, S.T.; Little, B.E.; Corcoran, B.; Liu, Y.; Bai, Y.; Moss, D.J.; Xu, X.; Xu, K. Integrated photonic neural networks. npj Nanophotonics 2025, 2, 28. [Google Scholar]

- M. Rowley, Pierre-Henry Hanzard, Antonio Cutrona, Hualong Bao, Sai T. Chu, Brent E. Little, Roberto Morandotti, David J. Moss, Gian-Luca Oppo, Juan Sebastian Totero Gongora, Marco Peccianti and Alessia Pasquazi, “Self-emergence of robust solitons in a micro-cavity”, Nature 608 (7922) 303 – 309 (2022).

- Arianfard, H.; Juodkazis, S.; Moss, D.J.; Wu, J. Sagnac interference in integrated photonics. Applied Physics Reviews 2023, 10, 011309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arianfard, H.; Wu, J.; Juodkazis, S.; Moss, D.J. Optical analogs of Rabi splitting in integrated waveguide-coupled resonators. Advanced Physics Research 2023, 2, 2200123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arianfard, H.; Wu, J.; Juodkazis, S.; Moss, D.J. Spectral shaping based on optical waveguides with advanced Sagnac loop reflectors. Paper No. PW22O-OE201-20, SPIE-Opto, Integrated Optics: Devices, Materials, and Technologies XXVI, SPIE Photonics West, San Francisco CA -27 (2022). 22 January. [CrossRef]

- Arianfard, H.; Wu, J.; Juodkazis, S.; Moss, D.J. Spectral Shaping Based on Integrated Coupled Sagnac Loop Reflectors Formed by a Self-Coupled Wire Waveguide. IEEE Photonics Technology Letters 2021, 33, 680–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arianfard, H.; Wu, J.; Juodkazis, S.; Moss, D.J. Three Waveguide Coupled Sagnac Loop Reflectors for Advanced Spectral Engineering. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2021, 39, 3478–3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arianfard, H.; Wu, J.; Juodkazis, S.; Moss, D.J. Advanced Multi-Functional Integrated Photonic Filters based on Coupled Sagnac Loop Reflectors. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2021, 39, 1400–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arianfard, H.; Wu, J.; Juodkazis, S.; Moss, D.J. Advanced multi-functional integrated photonic filters based on coupled Sagnac loop reflectors. Paper 11691-4, PW21O-OE203-44, Silicon Photonics XVI, SPIE Photonics West, San Francisco CA March 6-11 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Moein, T.; Xu, X.; Moss, D.J. Advanced photonic filters via cascaded Sagnac loop reflector resonators in silicon-on-insulator integrated nanowires. Applied Physics Letters Photonics 2018, 3, 046102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Lin, H.; Moss, D.J.; Loh, K.P.; Jia, B. Graphene oxide for photonics, electronics and optoelectronics. Nature Reviews Chemistry 2023, 7, 162–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Jia, L.; Qu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. Graphene Oxide for Nonlinear Integrated Photonics. Laser & Photonics Reviews 2023, 17, 2200512. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Wu, J.; Liu, W.; Jin, D.; Dirani, H.E.; Kerdiles, S.; Sciancalepore, C.; Demongodin, P.; Grillet, C.; Monat, C.; Huang, D.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. 2D graphene oxide: a versatile thermo-optic material. Advanced Functional Materials 2024, 34, 2406799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Jia, L.; Zhang, Y.; Qu, Y.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. Graphene Oxide for Integrated Photonics and Flat Optics. Advanced Materials 2021, 33, 2006415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Yang, Y.; Qu, Y.; Jia, L.; Moein, T.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. Enhanced Kerr Nonlinearity and Nonlinear Figure of Merit in Silicon Nanowires Integrated with 2D Graphene Oxide Films. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2020, 12, 33094–33103. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Wu, J.; Jin, D.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Jia, L.; Huang, D.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. Integrated waveguide and microring polarizers incorporating 2D reduced graphene oxide. Opto-Electronic Science 2025, 4, 240032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Wu, J.; Hu, J.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Jia, L.; Huang, D.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. Silicon photonic waveguide and microring resonator polarizers incorporating 2D graphene oxide films. Applied Physics Letters 2024, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arianfard, H.; Juodkazis, S.; Moss, D.J.; Wu, J. Sagnac interference in integrated photonics. Applied Physics Reviews 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Ren, S.; Hu, J.; Huang, D.; Moss, D.J.; Wu, J. Modeling of Complex Integrated Photonic Resonators Using the Scattering Matrix Method. Photonics 2024, 11, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yang, Y.; Qu, Y.; Xu, X.; Liang, Y.; Chu, S.T.; Little, B.E.; Morandotti, R.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. Graphene Oxide Waveguide and Micro-Ring Resonator Polarizers. Laser & Photonics Reviews 2019, 13, 1900056. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Wu, J.; Jin, D.; Chu, S.T.; Little, B.E.; Huang, D.; Morandotti, R.; Moss, D.J. Thermo-Optic Response and Optical Bistablility of Integrated High-Index Doped Silica Ring Resonators. Sensors 2023, 23, 9767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Wu, J.; Xu, X.; Chu, S.T.; Little, B.E.; Morandotti, R.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. Enhanced four-wave mixing in graphene oxide coated waveguides. Applied Physics Letters Photonics 2018, 3, 120803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; et al. Graphene oxide waveguide and micro-ring resonator polarizers. Laser and Photonics Reviews 2019, 13, 1900056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yang, Y.; Qu, Y.; Xu, X.; Liang, Y.; Chu, S.T.; Little, B.E.; Morandotti, R.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. Graphene oxide waveguide polarizers and polarization selective micro-ring resonators. Laser and Photonics Reviews 2019, 13, 1900056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; et al. 2D layered graphene oxide films integrated with micro-ring resonators for enhanced nonlinear optics. Small 2020, 16, 1906563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Wu, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, Y.; El Dirani, H.; Crochemore, R.; Demongodin, P.; Sciancalepore, C.; Grillet, C.; Monat, C.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. Enhanced nonlinear four-wave mixing in silicon nitride waveguides integrated with 2D layered graphene oxide films. Advanced Optical Materials 2020, 8, 2001048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yang, Y.; Qu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, L.; Xu, X.; Chu, S.T.; Little, B.E.; Morandotti, R.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. Enhanced nonlinear four-wave mixing in microring resonators integrated with layered graphene oxide films. Small 2020, 16, 1906563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yang, Y.; Qu, Y.; Xu, X.; Liang, Y.; Chu, S.T.; Little, B.E.; Morandotti, R.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. Graphene oxide waveguide polarizers and polarization selective micro-ring resonators. Paper 11282-29, SPIE Photonics West, San Francisco, CA, 4-7 February (2020). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Qu, Y.; Jia, L.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. Design and optimization of four-wave mixing in microring resonators integrated with 2D graphene oxide films. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2021, 39, 6553–6562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. Analysis of four-wave mixing in silicon nitride waveguides integrated with 2D layered graphene oxide films. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2021, 39, 2902–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, L.; Yang, Y.; Xu, X.; Chu, S.T.; Little, B.E.; Morandotti, R.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. Graphene oxide for enhanced optical nonlinear performance in CMOS compatible integrated devices. Paper No. 11688-30, PW21O-OE109-36, 2D Photonic Materials and Devices IV, SPIE Photonics West, San Francisco CA March 6-11 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Qu, Y.; Jia, L.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. Optimizing the Kerr nonlinear optical performance of silicon waveguides integrated with 2D graphene oxide films. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2021, 39, 4671–4683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Jia, L.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. Photo thermal tuning in GO-coated integrated waveguides. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang Y; Wu J; Qu Y; Jia L; Jia B; Moss, D. J. Graphene oxide-based waveguides for enhanced self-phase modulation. Annals of Mathematics and Physics 2022, 5, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Yang, Y.; Qu, Y.; Jia, L.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. Enhanced spectral broadening of femtosecond optical pulses in silicon nanowires integrated with 2D graphene oxide films. Micromachines 2022, 13, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Yang, Y.; Qu, Y.; Jia, L.; El Dirani, H.; Kerdiles, S.; Sciancalepore, C.; Demongodin, P.; Grillet, C.; Monat, C.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. Enhanced supercontinuum generated in SiN waveguides coated with GO films. Advanced Materials Technologies 2023, 8, 2201796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Yang, Y.; Qu, Y.; El Dirani, H.; Crochemore, R.; Sciancalepore, C.; Demongodin, P.; Grillet, C.; Monat, C.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. Enhanced self-phase modulation in silicon nitride waveguides integrated with 2D graphene oxide films. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics 2023, 29, 5100413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Jia, L.; El Dirani, H.; Kerdiles, S.; Sciancalepore, C.; Demongodin, P.; Grillet, C.; Monat, C.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. Integrated optical parametric amplifiers in silicon nitride waveguides incorporated with 2D graphene oxide films. Light: Advanced Manufacturing 2023, 4, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, J.; Yang, Y.; Jin, D.; Liu, W.; Huang, D.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. Novel functionality with 2D graphene oxide films integrated on silicon photonic chips. Advanced Materials 2024, 36, 2403659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Wu, J.; Hu, J.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Jia, L.; Huang, D.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. Silicon photonic waveguide and microring resonator polarizers incorporating 2D graphene oxide films. Applied Physics Letters 2024, 125, 053101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Jia, L.; Jin, D.; Jia, B.; Hu, X.; Moss, D.; Gong, Q. Advanced optical polarizers based on 2D materials. npj Nanophotonics 2024, 1, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Yang, Y.; Jia, L.; Grillet, C.; Monat, C.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. Graphene oxide for enhanced nonlinear optics in integrated photonic chips. Paper 12888-16, Conference OE109, 2D Photonic Materials and Devices VII, Chair(s): Arka Majmdar; Carlos M. Torres Jr.; Hui Deng, SPIE Photonics West, San Francisco CA, January 27 – February 1 (2024). Proceedings Volume 12888, 2D Photonic Materials and Devices VII; 1288805 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Liu, W.; Jia, L.; Hu, J.; Huang, D.; Wu, J.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. Thickness and Wavelength Dependent Nonlinear Optical Absorption in 2D Layered MXene Films. Small Science 2024, 4, 2400179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Hu, J.; Jia, L.; Jin, D.; Jia, B.; Hu, X.; Moss, D.J.; Gong, Q. 2D material integrated photonics: towards industrial manufacturing and commercialization. Applied Physics Letters Photonics 2025, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Qu, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. Third-order optical nonlinearities of 2D materials at telecommunications wavelengths. Micromachines 2023, 14, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Qu, Y.; Jia, B.; Chen, Z.; Moss, D.J. Fabrication Technologies for the On-Chip Integration of 2D Materials. Small: Methods 2022, 6, 2101435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Cui, D.; Wu, J.; Feng, H.; Yang, T.; Yang, Y.; Du, Y.; Hao, W.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. BiOBr nanoflakes with strong nonlinear optical properties towards hybrid integrated photonic devices. Applied Physics Letters Photonics 2019, 4, 090802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Wu, J.; Yang, Y.; Du, Y.; Jia, B.; Moss, D.J. Large Third-Order Optical Kerr Nonlinearity in Nanometer-Thick PdSe2 2D Dichalcogenide Films: Implications for Nonlinear Photonic Devices. ACS Applied Nano Materials 2020, 3, 6876–6883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kues, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. Quantum optical microcombs. Nature Photonics 2019, 13, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer; Caspani, L. ; Clerici, M.; et al. Integrated frequency comb source of heralded single photons. Optics Express 2014, 22, 6535–6546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, C.; et al. Cross-polarized photon-pair generation and bi-chromatically pumped optical parametric oscillation on a chip. Nature Communications 2015, 6, 8236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspani, L.; Reimer, C.; Kues, M.; et al. Multifrequency sources of quantum correlated photon pairs on-chip: a path toward integrated Quantum Frequency Combs. Nanophotonics 2016, 5, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, C.; et al. Generation of multiphoton entangled quantum states by means of integrated frequency combs. Science 2016, 351, 1176–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kues, M.; et al. On-chip generation of high-dimensional entangled quantum states and their coherent control. Nature 2017, 546, 622–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roztocki, P.; et al. Practical system for the generation of pulsed quantum frequency combs. Optics Express 2017, 25, 18940–18949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; et al. Induced photon correlations through superposition of two four-wave mixing processes in integrated cavities. Laser and Photonics Reviews 2020, 14, 2000128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, C.; et al. High-dimensional one-way quantum processing implemented on d-level cluster states. Nature Physics 2019, 15, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roztocki, P.; et al. Complex quantum state generation and coherent control based on integrated frequency combs. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2019, 37, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciara, S.; et al. Generation and Processing of Complex Photon States with Quantum Frequency Combs. IEEE Photonics Technology Letters 2019, 31, 1862–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaut, N.; George, A.; Monika, M.; Nosrati, F.; Yu, H.; Sciara, S.; Crockett, B.; Peschel, U.; Wang, Z.; Franco, R.L.; Chemnitz, M.; Munro, W.J.; Moss, D.J.; Azaña, J.; Morandotti, R. Progress in integrated and fiber optics for time-bin based quantum information processing. Advanced Optical Technologies 2025, 14, 1560084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Crockett, B.; Montaut, N.; Sciara, S.; Chemnitz, M.; Chu, S.T.; Little, B.E.; Moss, D.J.; Wang, Z.; Azaña, J.; Morandotti, A.R. Exploiting nonlocal correlations for dispersion-resilient quantum communications. Physical Review Letters 2025, 134. [Google Scholar]

- Sciara, S.; Roztocki, P.; Fisher, B.; Reimer, C.; Cortez, L.R.; Munro, W.J.; Moss, D.J.; Cino, A.C.; Caspani, L.; Kues, M.; Azana, J.; Morandotti, R. Scalable and effective multilevel entangled photon states: A promising tool to boost quantum technologies. Nanophotonics 2021, 10, 4447–4465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspani, L.; Reimer, C.; Kues, M.; et al. Multifrequency sources of quantum correlated photon pairs on-chip: a path toward integrated Quantum Frequency Combs. Nanophotonics 2016, 5, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Sciara, S.; Chemnitz, M.; Montaut, N.; Fischer, B.; Helsten, R.; Crockett, B.; Wetzel, B.; Göbel, T.A.; Krämer, R.; Little, B.E.; Chu, S.T.; Moss, D.J.; Nolte, S.; Munro, W.J.; Wang, Z.; Azaña, J.; Morandotti, R. Quantum key distribution implemented with d-level time-bin entangled photons. Nature Communications 2025, 16, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 2D Material |

Waveguide Material | 2D Material Thickness | WD (µm) |

PDL (dB) |

OBW (µm) |

FOM | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graphene | Polymer | ‒ a | 7.00 × 5.00 | ~19 | ‒ a | ~0.7 | [16] |

| Graphene | Glass | ‒ a | 11.50 × 2.60 | ~27 | ~1.23–1.61 | ~3.0 | [61] |

| Graphene | Chalcogenide | Monolayer | ‒ a | ~23 | ~0.94–1.60 | ~28.8 | [14] |

| Graphene | Polymer | > or < 10 nm b | 10.00 × 5.00 | ~6 | ‒ a | ~0.7 | [15] |

| MoS2 | Nd:YAG | ~6.5 nm | ‒ a | ~3 | ‒ a | ~7.5 | [21] |

| MoS2 | Polymer | ~2.5 nm | 8.00 × 8.00 | ~12.6 | ~0.65–0.98 | ‒ a | [22] |

| GO | Polymer | ~2000 nm | 10.00 × 5.00 | ~40 | ~1.53–1.63 | ~6.2 | [19] |

| GO | Doped silica | ~2–200 nm | 3.00 × 2.00 | ~54 | ~0.63–1.60 | ~7.2 | [17] |

| GO | Silicon | ~10 nm | 0.40 × 0.22 | ~17 | ~1.50–1.60 | ~1.7 | [18] |

| rGO | Silicon | Monolayer | 0.40 × 0.22 | ~47 | ~1.50–1.60 | ~3.0 | [62] |

| MoS2 | Silicon | Monolayer | 0.40 × 0.22 | ~21 | ~1.50–1.60 | ~4.2 | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).