1. Introduction

The global electronics industry is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by the dual imperatives of advancing technological innovation and meeting escalating sustainability demands [

8,

29,

30,

66]. Across the world, regulatory bodies are enacting increasingly stringent measures to address the environmental and social impacts of this sector, particularly concerning electronic waste (e-waste) management, hazardous substance control, and the promotion of a circular economy (CE) [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

18,

23,

26,

28,

31,

32,

33,

40,

41,

68]. Navigating this complex global regulatory maze while leveraging sustainable practices for competitive advantage is a critical challenge for multinational electronics corporations [

1]. The "Global E-waste Monitor 2020" highlights the scale of this challenge, detailing increasing quantities and flows of e-waste globally [

65].

While the European Union (EU) has been a frontrunner with comprehensive frameworks such as the Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR) [

9,

12,

28,

40], Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) Directive [

10,

13,

18,

19,

23,

26,

31,

32], and Restriction of Hazardous Substances (RoHS) Directive [

19,

23,

27,

45,

61], these often serve as catalysts or benchmarks for regulatory developments in other major economic zones. For example, North America has federal legislation such as the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) and influential state-level e-waste laws [

20,

46,

62]. Asian economic leaders such as China and Japan have implemented their own RoHS-equivalent standards and robust appliance recycling laws [

19,

47,

48]. Similar trends towards Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) and specific e-waste management rules are evident in South America, Africa, and Oceania [

13,

18,

49,

50,

51]. The OECD's "Global Material Resources Outlook to 2060" further underscores the economic drivers and environmental consequences necessitating such global regulatory attention [

64].

Concurrently, the sector is being reshaped by emergent technologies such as Artificial Intelligence (AI) [

10,

30,

34,

35], Digital Twins [

35,

36,

37,

38], and Digital Product Passports (DPPs) [

9,

12], which offer new capabilities for enhancing sustainability and compliance across global value chains. This backdrop of intense regulatory pressure [

67] and technological transformation, coupled with investor and stakeholder focus on corporate Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) performance [

66], has significantly increased. This study quantitatively investigates the financial materiality of ESG performance using a sample of globally operating multinational electronics firms. The key research questions are:

RQ1: Is there a statistically significant association between ESG performance metrics and stock market excess returns of multinational electronics firms, after controlling for market risk factors?

RQ2: Do the ESG factors for these global electronics firms exhibit distinct dynamic interactions with traditional market risk factors?

RQ3: What are the financial implications of ESG performance in this sector, considering global regulatory pressures and technological enablers, thereby informing a conceptual model of "Regulatory-ESG Financial Salience"?

This research analyzes historical stock market data, ESG scores [

2,

3,

4], and financial risk factors [

5] for 13 multinational electronics firms. Preliminary findings suggest that sustained, long-term ESG performance, particularly overall and social metrics, is positively associated with stock returns, while a constructed ESG factor appears largely independent of traditional market risks. This study aims to provide nuanced quantitative evidence within this specific global industry context, acknowledging the vision for a "New Circular Vision for Electronics" advocated by bodies like the World Economic Forum [

63]. The paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 examines the theoretical framework and relevant literature.

Section 3 describes the data, variables, and methodology.

Section 4 discusses diagnostic tests.

Section 5 presents empirical findings.

Section 6 addresses these findings, provides a conceptual paradigm, and examines the worldwide implications and limitations.

Section 7 concludes.

2. Theoretical Framework and Literature Review

This study integrates stakeholder theory, the Natural Resource-Based View (NRBV), and the Porter Hypothesis to understand the ESG-finance nexus in the global electronics industry. Stakeholder theory suggests that firms addressing diverse stakeholder interests, including ESG concerns related to environmental protection and social welfare, can build trust, enhance reputation, and potentially improve financial performance [

17,

24,

52,

66]. This is particularly relevant for the electronics sector, where stakeholder pressures increasingly focus on global environmental impacts such as e-waste and resource use [

10,

13,

18,

23,

26,

28,

31,

32,

65,

68], as well as social issues like labor conditions in international supply chains [

13,

15,

19,

23,

43]. The NRBV posits that unique environmental capabilities and green innovations, crucial in an industry striving for eco-design and circularity [

9,

11,

12,

14,

25,

33,

40,

41,

44], can be sources of sustainable competitive advantage [

16,

19,

53]. The Porter Hypothesis argues that well-designed environmental regulations can spur innovation that enhances competitiveness [

1,

16,

20,

54,

59], a perspective relevant given the global proliferation of electronics sustainability regulations. However, the impact of regulatory stringency can vary, with potential for negative consequences if regulations are not harmonized or effectively implemented across different jurisdictions [

21,

22,

23,

55,

69]. The impact of corporate sustainability on organizational processes and performance itself is a significant area of study [

60].

A complex tapestry of regulations governs sustainable electronics globally. Europe's WEEE [

10,

13,

18,

19,

23,

26,

31,

32], RoHS [

19,

23,

27,

45,

61], and ESPR/Eco-Design directives [

9,

11,

12,

14,

25,

33,

40,

44], alongside its Circular Economy Action Plan including Digital Product Passports [

9,

12,

33,

41], are highly influential. North America utilizes federal acts like the US RCRA and TSCA, complemented by state-level e-waste laws [

20,

46,

62] and programs like Energy Star. Key Asian regulations include China's RoHS and Circular Economy Promotion Law [

19,

47], Japan's Home Appliance Recycling Law [

48], and India's E-Waste (Management) Rules [

13,

49]. Similar regulatory objectives are pursued in South America (e.g., Brazil's National Solid Waste Policy [

50]), Africa (e.g., South Africa's National Environmental Management Act [

51]), and Oceania (e.g., Australia's Product Stewardship Act [

56]). This global regulatory trend [

1,

67], while varied, signals a collective move towards greater producer responsibility and lifecycle management in electronics [

1,

22,

23,

55].

Emerging technologies are increasingly critical for the electronics industry to meet these global sustainability goals. Artificial Intelligence offers significant potential for optimizing resource utilization, enhancing supply chain transparency, and improving e-waste recycling processes [

10,

30,

34,

35]. Digital Twins facilitate sustainable product design, predictive maintenance, and lifecycle management, supporting eco-design and circular economy principles on a global scale [

35,

36,

37,

38]. Smart tags and blockchain are foundational for implementing effective Digital Product Passports, enhancing traceability and end-of-life decision-making across international supply chains [

9,

10,

12,

57]. The strategic deployment of these technologies is vital for managing complexity and driving sustainable practices worldwide [

8,

29,

30,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

58].

The financial implications of ESG performance for globally operating firms remain a central theme in sustainable finance [

7,

16,

17,

24,

52,

53,

54,

59]. Numerous studies have explored this link, with results often varying by industry, region, and methodology [

7,

19,

60]. Asset pricing models like the Fama-French framework [

5] are standard for assessing whether ESG factors explain returns beyond known risks [

7]. Panel data methods allow for robust analysis across firms and time [

6,

7], while VAR models can reveal dynamic interactions between ESG and market factors [

6]. This study applies these quantitative tools to major global electronics players, using ESG data sourced via tools like Python’s yesg library [

2] and interpreted according to established rating methodologies [

3,

4].

3. Data, Variables, and Methodology

3.1. Data

This study analyzed monthly data from March 2015 to March 2025 for a panel of 13 multinational electronics corporations with significant global operations, including headquarters in the United States (e.g., Apple, Intel), Asia (e.g., Samsung, LG), and Europe (e.g., Infineon). Stock price data were retrieved using the yfinance Python library. Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) scores were primarily obtained using the Python yesg library [

2]. The methodologies of Sustainalytics [

3] and MSCI [

4] were reviewed for contextual understanding. Data for the Fama-French five-factor model plus momentum (FF6) [

5] were sourced from Kenneth R. French's Data Library.

3.2. Variables

For the analysis, several variables were constructed. The dependent variable for the panel regression was Excess_Return_it, defined as the monthly excess return for firm i at time t. This was calculated by subtracting the risk-free rate, obtained from the Fama-French dataset, from the firm's stock return. The key independent variables in the panel regression included Lagged_Total-Score_it-l, representing the overall ESG score for firm i at time t-l, where l signifies various lag lengths of 1, 3, and 6 months. Another key independent variable was Avg12M_Lagged_Total-Score_it, a 12-month moving average of the 1-month lagged total ESG score. Similar lagged and averaged variables were also established for the individual E-Score, S-Score, and G-Score components. Control variables for the panel regression consisted of the contemporaneous monthly returns of the six Fama-French-Momentum factors: MKT_RF_t, SMB_t, HML_t, RMW_t, CMA_t, and WML_t [

4]. For the VAR analysis, specific variables were employed, including HML_ESG_t, which is a High-Minus-Low ESG factor. This factor was derived by monthly sorting firms in the sample into three portfolios based on their Lagged_Total-Score, with HML_ESG_t being the equally-weighted average return of the highest ESG portfolio minus that of the lowest ESG portfolio. The VAR analysis also incorporated the six Fama-French-Momentum factors previously mentioned.

3.3. Methodology

Panel regression (primarily Two-Way Fixed Effects) and Vector Autoregression (VAR) methods were employed using statsmodels [

6]. The panel regressions assess the ESG-return relationship (RQ1), controlling for firm-fixed effects (α_i), time-fixed effects (λ_t), and FF6 market factors: Excess_Return_it = α_i + λ_t + β1*ESG_Score_it-l + Σ_k β_k*ControlFactor_kt + ε_it [

7]. A VAR (1) model (lag selected by BIC) explores dynamic interplay (RQ2) via Granger causality, IRFs, and FEVDs. Jensen's alpha for the HML_ESG factor is estimated via OLS with HAC robust standard errors.

4. Diagnostic Testing of Variables and Regression Models

To establish the econometric soundness of the subsequent empirical analyses, a series of diagnostic examinations was performed on the dataset and the proposed regression frameworks. These tests are crucial for ensuring the validity and reliability of the study's findings.

4.1. Assessment of Inter-Variable Correlations

Examining the pairwise links between the main variables utilized in the panel regressions, including several lagged ESG scores and the Fama-French-Momentum factors, a Pearson correlation analysis was conducted. The correlation matrix (available from the author upon request) revealed generally low levels of association between the ESG metrics and the market risk factors. This outcome alleviates concerns regarding potential issues of severe multicollinearity, which could otherwise compromise the precision and interpretability of the estimated coefficients for the ESG variables in the panel regression analyses.

4.2. Unit Root Tests for Time Series Stationarity

Time series variables employed in the Vector Autoregression (VAR) model, namely, the constructed HML_ESG factor, MKT_RF, SMB, HML, RMW, CMA, and WML, were subjected to the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test to assess their stationarity. The results, summarized in

Table 1, confirm that all series are stationary at conventional significance levels (all p-values < 0.01), indicating that they do not contain a unit root and can be appropriately included in the VAR model in their level form.

4.3. Examination of Residual Serial Correlation

Following the estimation of each panel regression model, the Durbin–Watson (DW) test statistic was calculated from the model residuals to detect the presence of first-order serial correlation. These statistics are noted with the primary regression outputs in

Section 5. For the VAR model, DW statistics for the residuals of each equation are presented in

Table 2. The values obtained are all close to 2.0, suggesting the absence of significant first-order autocorrelation in the VAR model's residuals. Firm-clustered standard errors were also consistently employed in panel regressions.

4.4. Test for Heteroskedasticity and Model Specification in Panel Regressions

Heteroskedasticity tests using the Breusch–Pagan (BP) test were conducted for panel regressions. For the primary Two-Way Fixed Effects model, the BP test (LM-statistic = 6.99, p-value = 0.430) did not reject homoskedasticity.

Table 3 summarizes key panel model specification tests, guiding the choice of the Two-Way Fixed Effects model as the primary approach due to its robustness in controlling for unobserved heterogeneity and common time shocks, despite the F-test for entity effects not being significant.

5. Empirical Results

This section presents the main findings from the panel regressions and VAR analysis.

5.1. Panel Regressions of Global Electronics Firm Stock Returns on ESG Performance

Table 4 summarizes the key Two-Way Fixed Effects panel regression results for the 13 multinational electronics firms (N=1519 firm-month observations), controlling for the six Fama-French-Momentum factors. This table highlights the most salient ESG variables; comprehensive outputs for all tested ESG metrics and alternative model specifications are available and can be accessed via the supplementary material.

The analysis indicates a statistically significant positive association between longer-term, sustained ESG performance and stock excess returns. The 12-month average lagged total ESG score (Avg12M_Lagged_Total-Score) shows the most robust positive relationship. A similar significant positive impact is observed for the 12-month average lagged Social-score (Avg12M_Lagged_S-Score). Shorter-term lags and individual Environmental and Governance scores generally did not exhibit statistically significant associations in this primary model. A sub-period robustness check (

Table 5) indicated some variations, particularly in the post-2020 period, where some S-score significances were borderline, potentially reflecting evolving market conditions or the impact of the smaller sample size in sub-periods.

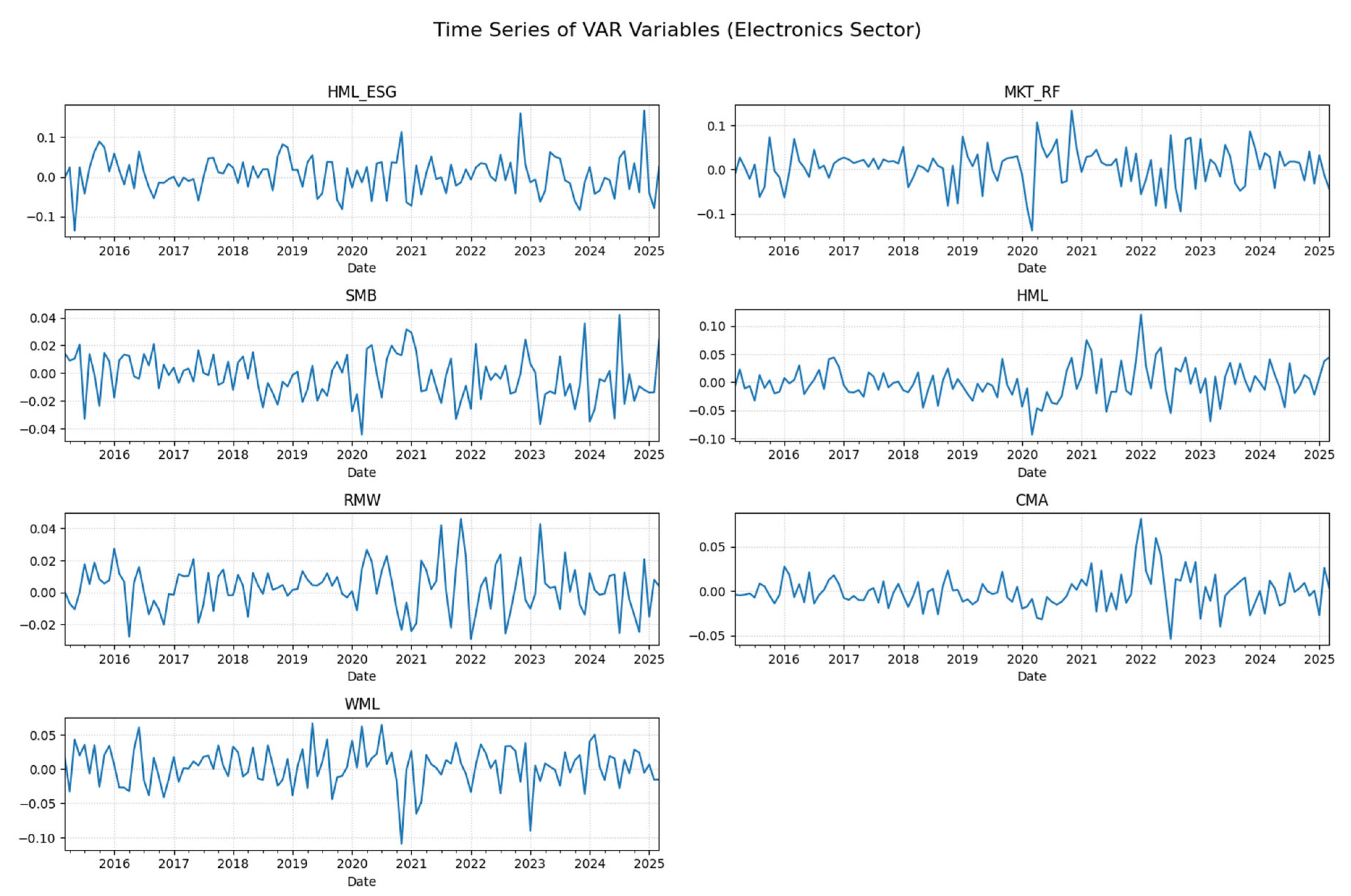

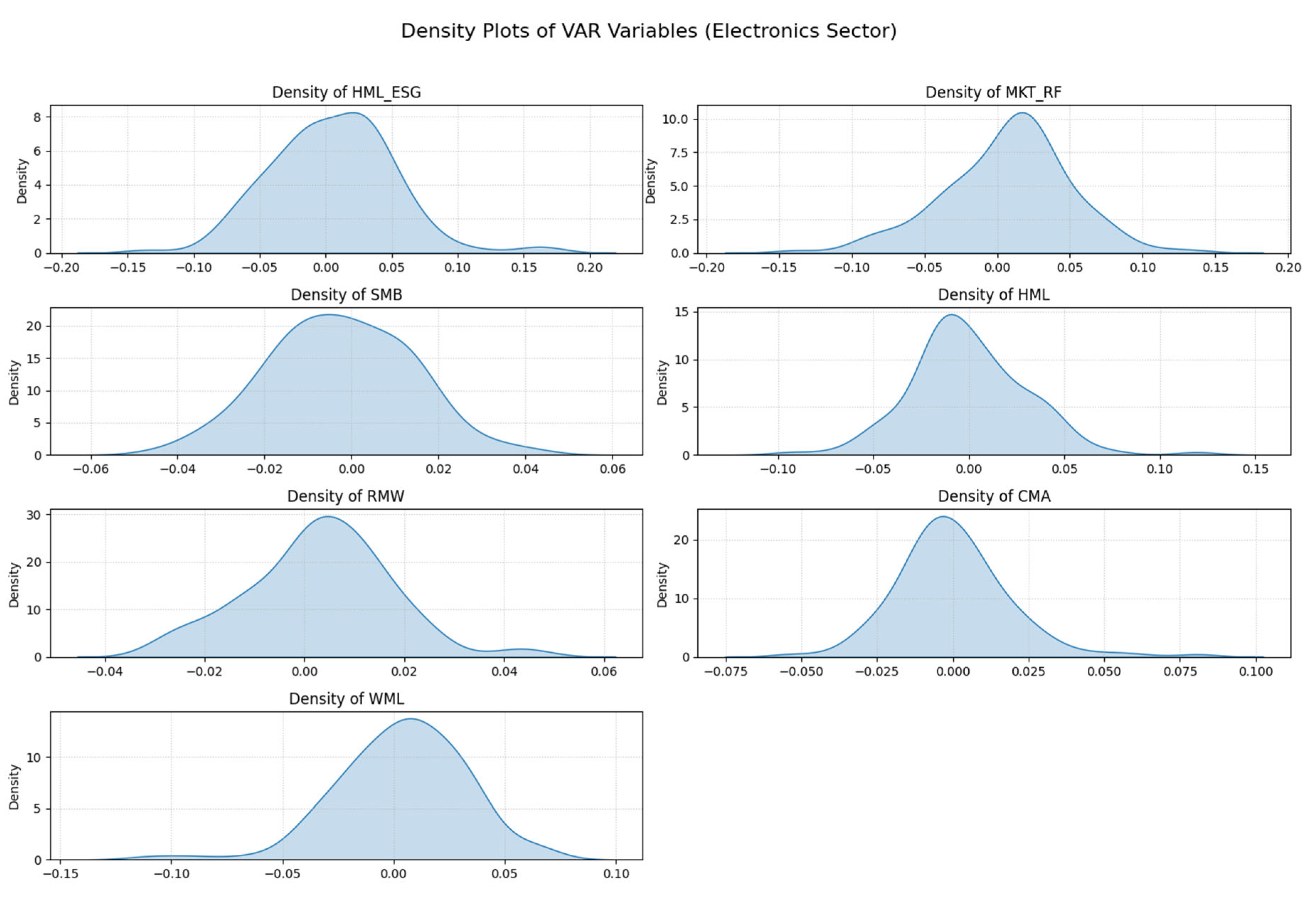

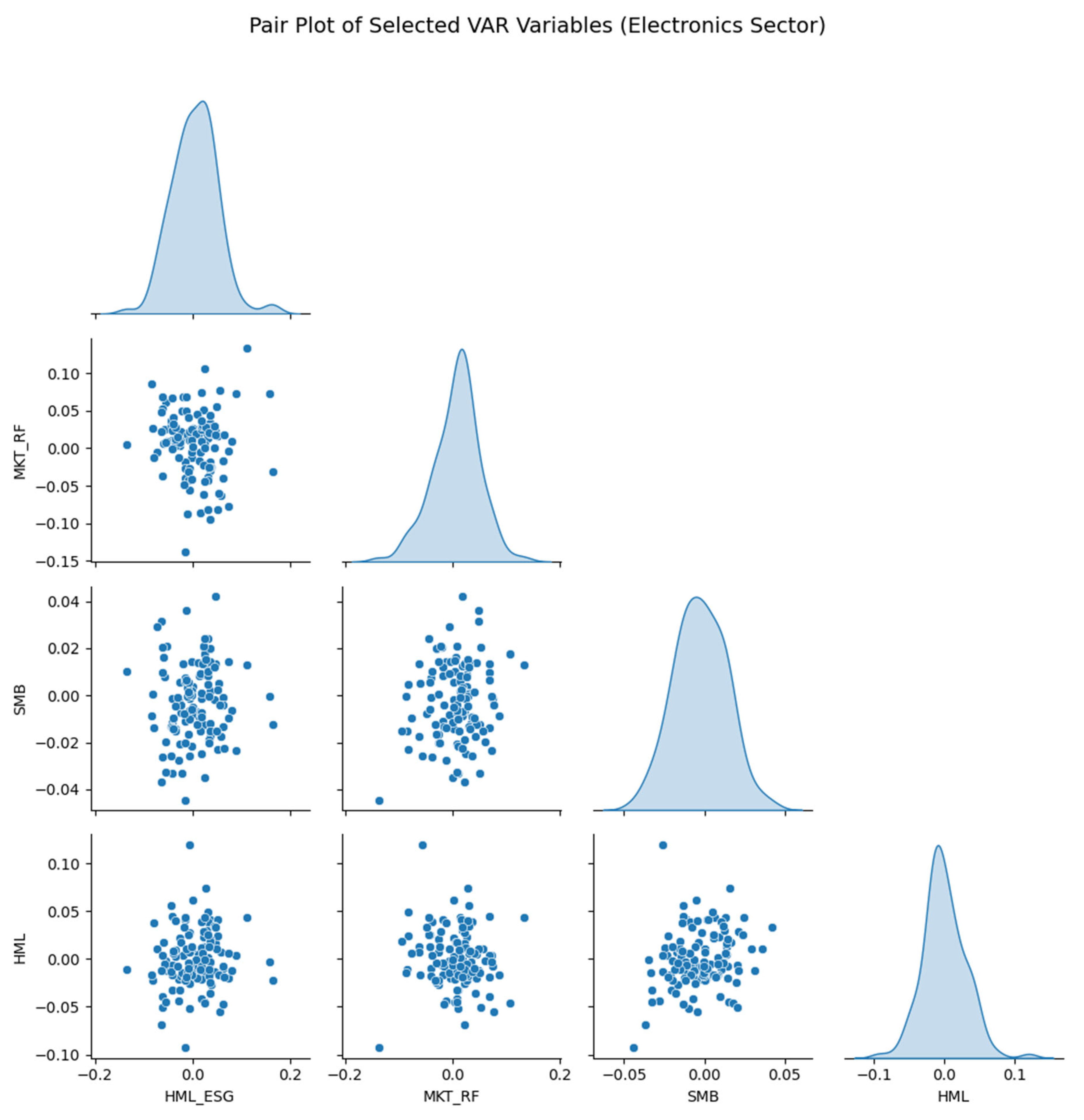

5.2. VAR Analysis of HML_ESG Factor and Market Factors

A VAR (1) model was estimated. Key diagnostic plots for the VAR input data, including time series plots of the HML_ESG factor and key market factors, their density distributions, and a scatter plot matrix, are presented in

Figure 1,

Figure 2, and

Figure 3, respectively, to visualize their characteristics and co-movements before formal testing.

Granger causality tests (

Table 6) showed no statistically significant causality from the block of FF6 factors to HML_ESG (p=0.723) or vice-versa for individual factors.

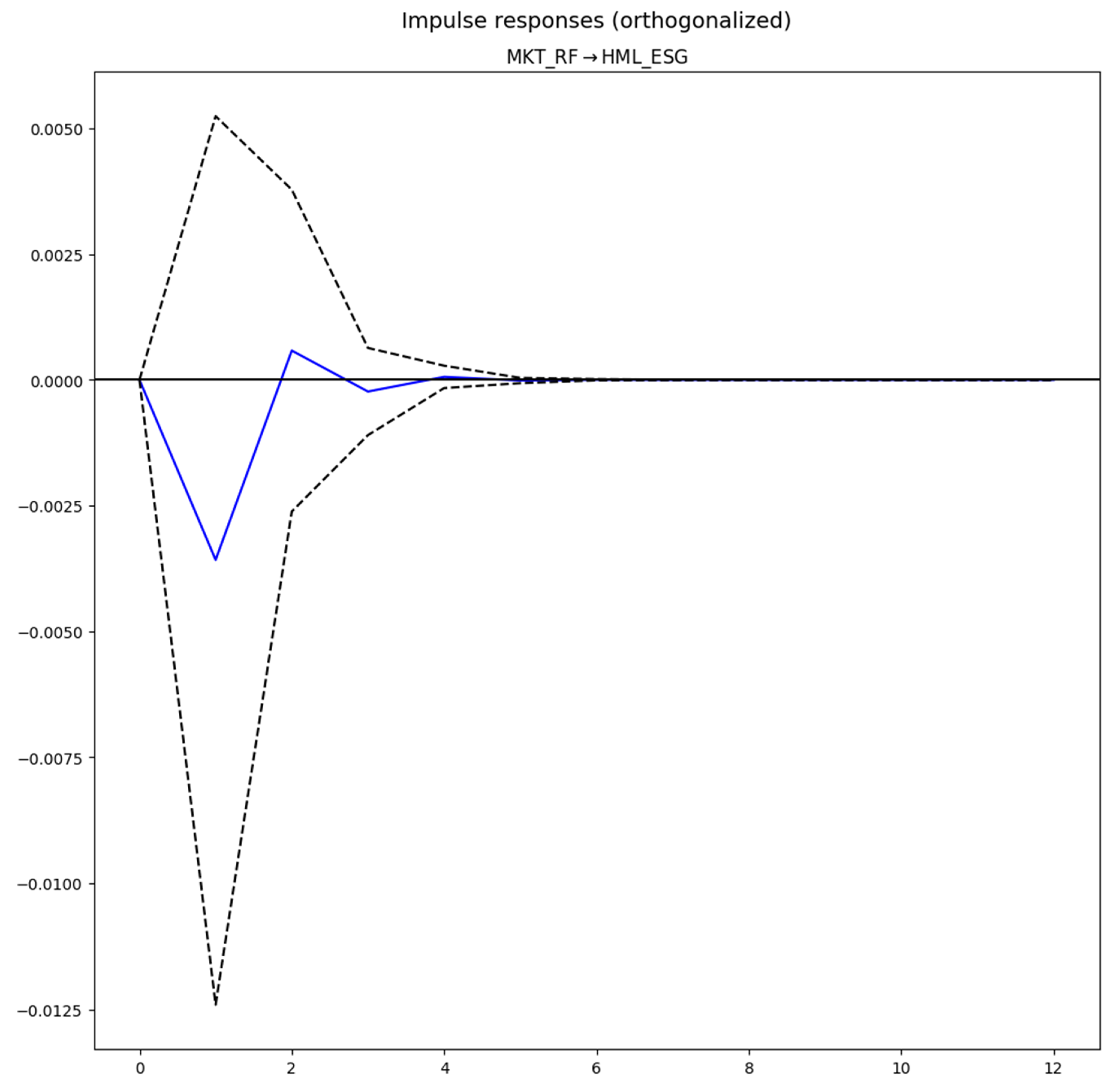

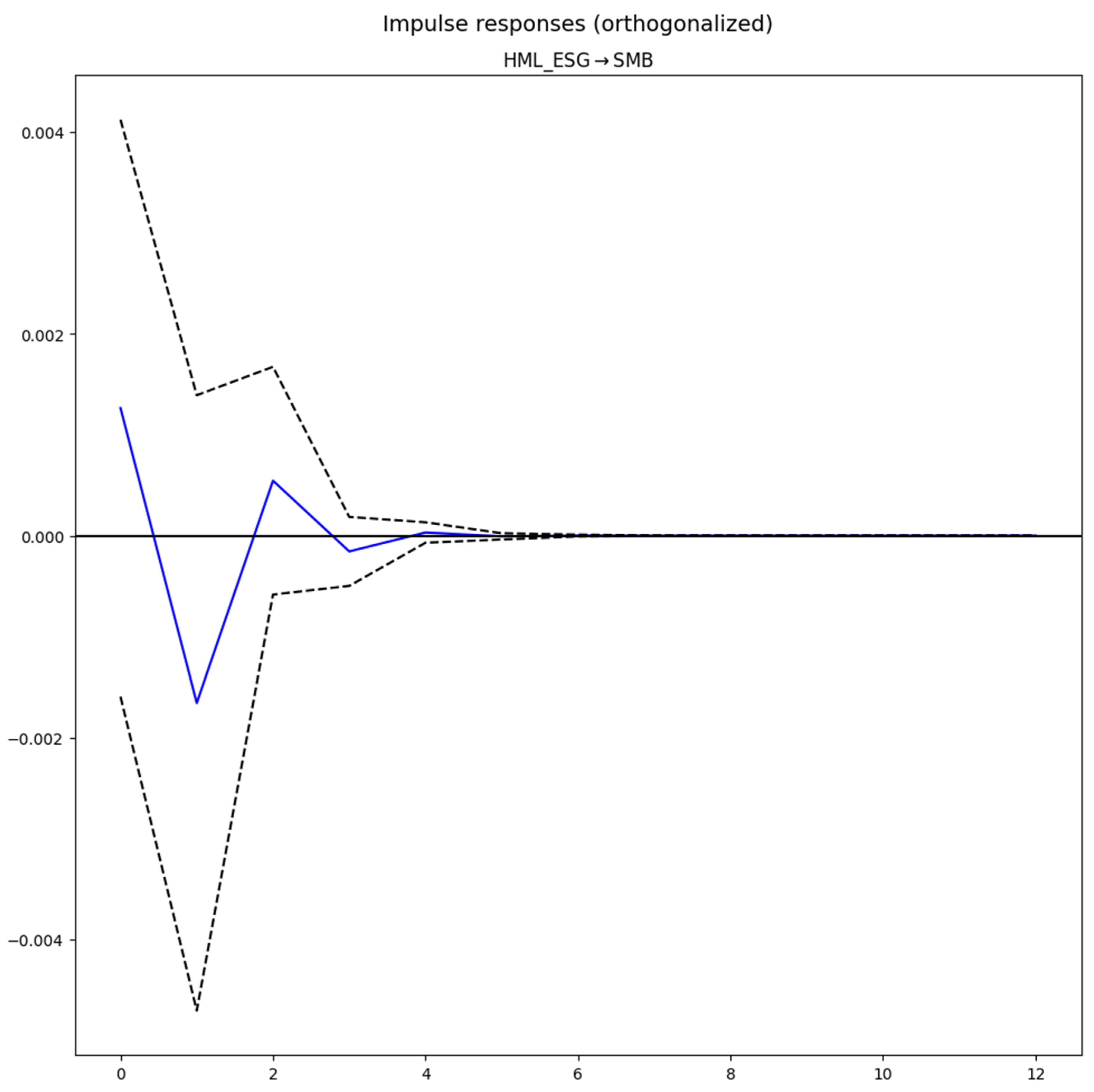

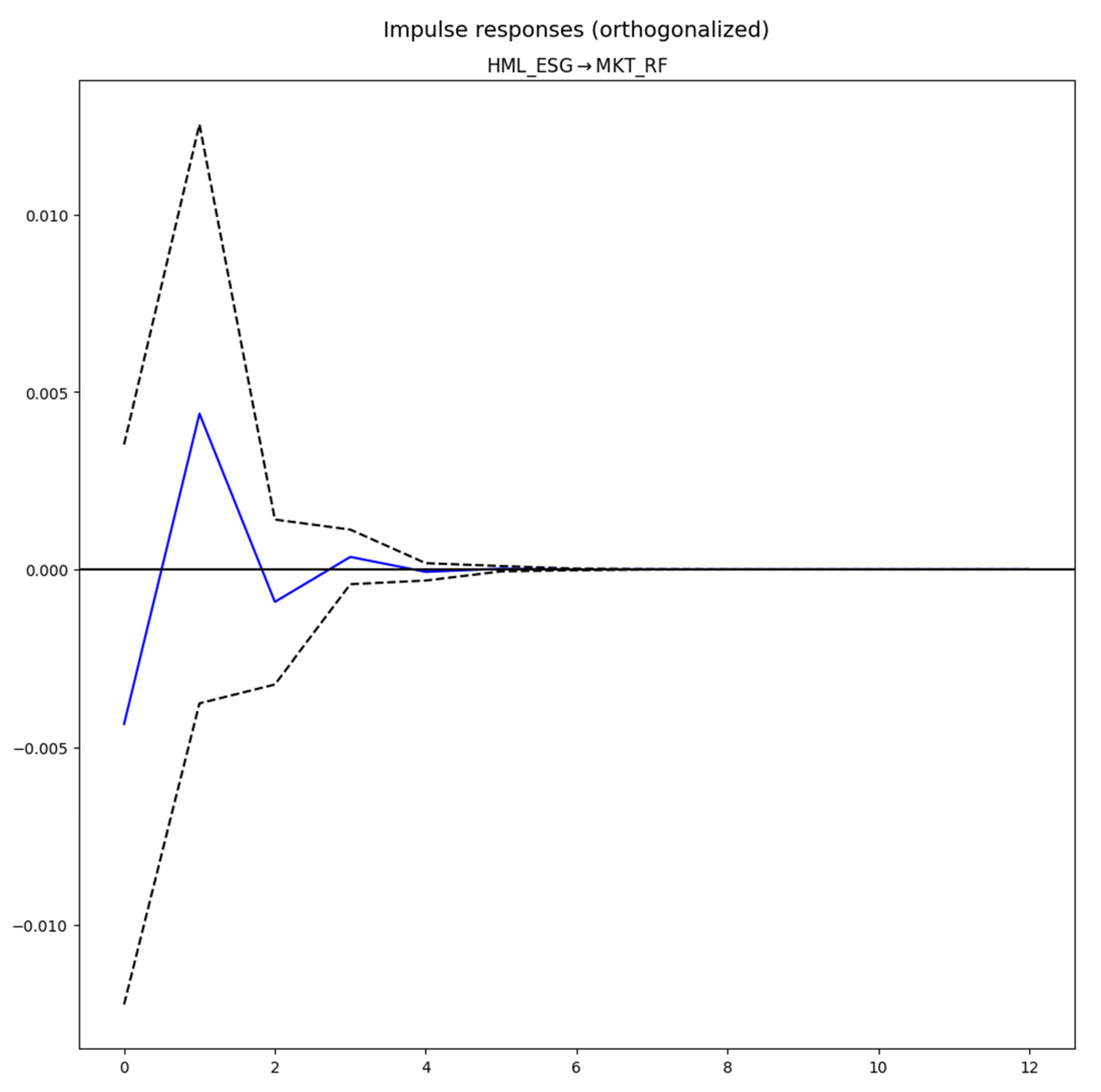

Impulse Response Functions (IRFs) are depicted in

Figure 4,

Figure 5, and

Figure 6.

Figure 4 shows the responses of the HML_ESG factor to one standard deviation shocks in each of the Fama-French-Momentum factors.

Figure 5 illustrates the responses of the Fama-French-Momentum factors to a one standard deviation shock in the HML_ESG factor.

Figure 6 presents selected cross-responses among the Fama-French-Momentum factors themselves. Collectively, these plots visually confirm generally weak and statistically insignificant dynamic linkages involving the HML_ESG factor over the 12-month forecast horizon.

The Forecast Error Variance Decomposition (FEVD) for HML_ESG is summarized in

Table 7. The results show that HML_ESG's innovations explain approximately 96.7% of its forecast error variance after 12 periods. The FEVDs for the other factors in the system (available from the author upon request) further illustrate the limited explanatory power of HML_ESG for their variances.

The time-series OLS regression of HML_ESG on the contemporaneous FF6 factors (

Table 8) yielded an insignificant monthly alpha of 0.0061 (p=0.141).

These VAR results collectively suggest that the HML_ESG factor, within this sample of global electronics firms, demonstrates considerable independence from traditional market risk factors.

6. Discussion and Implications

The empirical findings of this study, based on an analysis of 13 multinational electronics firms, offer quantitative insights into the financial dimensions of ESG performance within the context of increasing global sustainability regulations and rapid technological advancements. The discussion now interprets these results in light of existing theories and their broader implications.

Addressing RQ1, the panel regression analysis suggests that sustained, long-term ESG performance, particularly in aggregate (Total-Score) and specifically through the Social (S) pillar, is positively and significantly associated with stock excess returns for the sampled firms (

Table 4). This indicates that financial markets may recognize and potentially reward consistent and comprehensive ESG commitments by these global electronics players, aligning with aspects of stakeholder theory where addressing broader societal concerns can lead to enhanced firm value [

17,

24,

52,

66] and observed impacts of sustainability on organizational performance [

60]. The specific salience of the S-score could reflect the heightened global investor and regulatory attention to social issues within the complex international supply chains of the electronics industry, such as labor practices, human rights, and community engagement [

1,

13,

15,

19,

23,

43,

54]. The finding that markets appear to value

sustained ESG performance (e.g., 12-month averages) over shorter-term fluctuations reinforces the idea that markets value deeply embedded, strategic commitments to sustainability rather than transient or superficial activities [

1,

16,

29].

Regarding RQ2, the VAR analysis shows limited dynamic interaction between the constructed HML_ESG factor and traditional Fama-French-Momentum market risk factors for this sample of global electronics firms (

Table 6,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6,

Table 7). The general absence of significant Granger causality and the FEVD results, where HML_ESG variance is largely self-explained, suggest that ESG performance in this sector might embody distinct risk characteristics not fully captured by conventional global market models [

5,

7,

59]. This aligns with the broader inquiry into ESG as a unique financial factor [

7,

16]. Although the HML_ESG factor did not generate statistically significant alpha in this study (

Table 8), its apparent orthogonality to established market factors is an area warranting further investigation.

6.1. The Global Regulatory Context and Technological Enablers for ESG

The global electronics industry faces a diverse yet increasingly converging set of sustainability regulations. While the EU’s comprehensive framework (WEEE, RoHS, ESPR, CE Action Plan, DPPs) [

9,

10,

12,

13,

18,

19,

23,

25,

26,

27,

28,

31,

32,

33,

40,

41,

44,

45,

46,

61] is influential, similar objectives are pursued in North America (e.g., US RCRA, state e-waste laws [

20,

46,

62]), Asia (e.g., China RoHS, Japanese recycling laws, Indian E-Waste Rules [

13,

19,

47,

48,

49]), and other regions through EPR schemes and waste management legislation [

1,

13,

18,

50,

51,

56]. This global trend, aiming for a more circular electronics economy [

63], necessitates sophisticated strategies for compliance and sustainable innovation [

1]. Emerging technologies like AI, Digital Twins, and blockchain are crucial enablers for meeting these global regulatory demands and enhancing ESG performance, facilitating everything from supply chain traceability to eco-design and circularity [

10,

12,

30,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

57]. The financial materiality of ESG may reflect the market's valuation of firms' abilities to leverage these technologies effectively within this complex global landscape [

1,

29,

30,

58,

67].

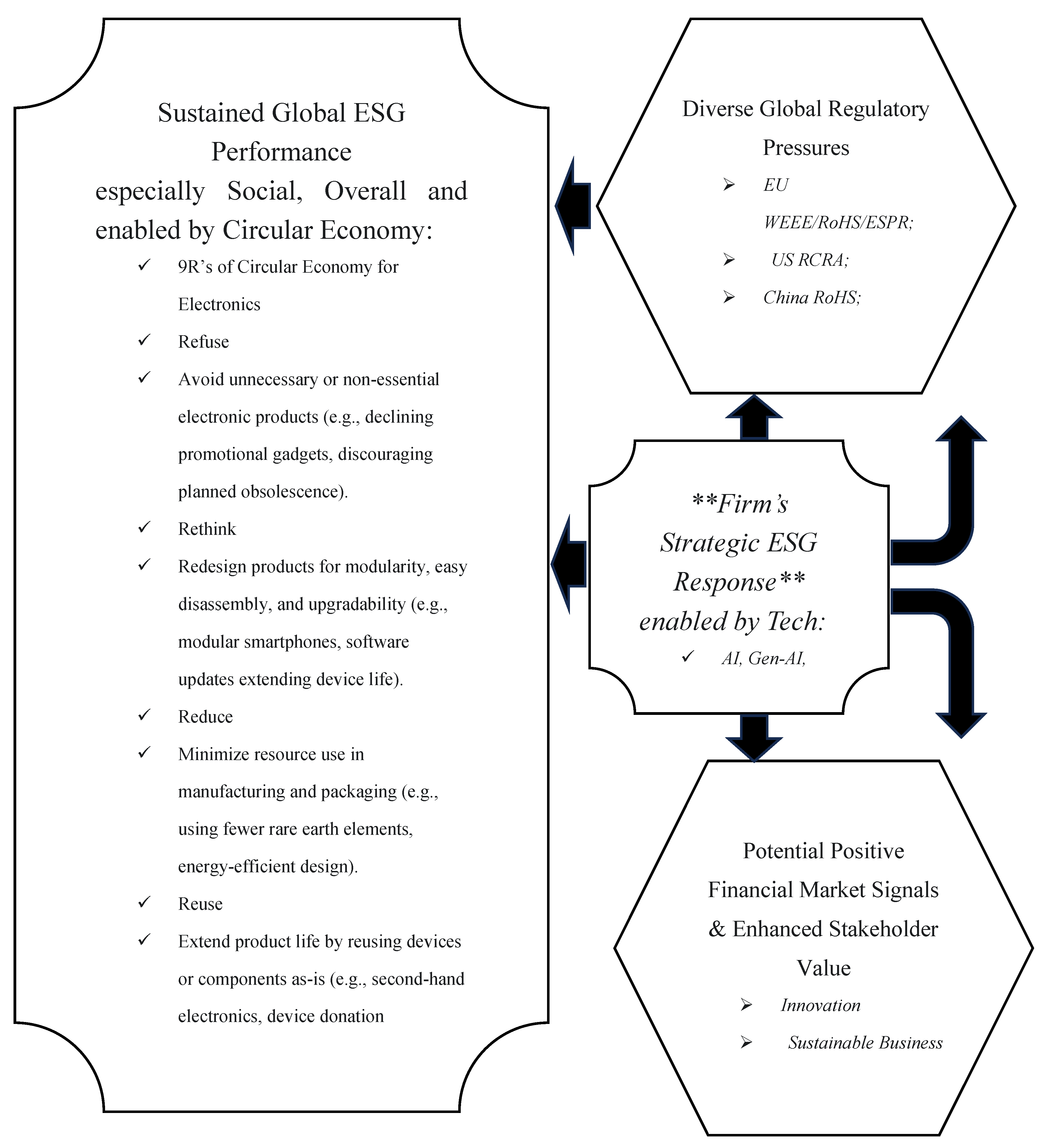

6.2. A Conceptual Global Regulatory-ESG Financial Salience Model (RQ3)

The empirical findings, interpreted within this global context, inform a "Global Regulatory-ESG Financial Salience Model" (

Figure 7). This model, conceptually aligned with frameworks for navigating global electronics regulations [

1], illustrates the potential pathways through which regulatory pressures and technological capabilities can interact with ESG performance to influence financial market outcomes.

Figure 7, a conceptual model illustrating the interplay between global regulations, technological enablement, ESG performance, and potential financial market signals in the electronics industry. This model posits that (1) converging global regulatory pressures drive firms towards enhanced ESG management, (2) strategic adoption of technology is key to managing global ESG compliance and performance, (3) financial markets may recognize and reward sustained, material ESG efforts, and (4) ESG performance in this sector may represent a financially distinct factor. Proactive and technologically adept navigation of global sustainability regulations, as suggested by [

1], can be financially salient.

6.3. Implications for Stakeholders

The study implies that multinational electronics firms should prioritize strategic, long-term ESG integration, leveraging technology to address diverse global regulatory demands, particularly in socially material areas [

1,

68,

69]. For investors, the findings suggest potential value in considering sustained ESG metrics and the distinct risk profile of ESG in this sector. Policymakers globally can infer that well-designed regulations may be increasingly reflected in market valuations, potentially validating aspects of the Porter Hypothesis where regulation drives innovation [

16,

20,

54,

59].

6.4. Limitations and Future Research

The primary limitation of this study is the sample size (N=13 firms), which, although representing major global players, restricts the statistical power and generalizability of the quantitative findings beyond this specific group and timeframe. ESG data sourced primarily via yesg [

2], reflects publicly available information and may differ from proprietary ESG datasets [

3,

4]. The construction of the HML_ESG factor is also specific to this study's sample and methodology. While Two-Way Fixed Effects models [

6,

7] were employed, unobserved variables or more complex endogeneity issues could still affect the ESG-finance relationship. The analysis provides a financial market perspective and does not directly measure the specific adoption levels of emerging technologies or the direct causal impact of individual regulatory enactments on operational innovation processes [

1].

Future research should aim to expand the quantitative analysis to a larger and more geographically diverse sample of global electronics firms. Comparative studies examining the ESG-finance link under different national or regional regulatory regimes would be highly valuable. Investigating the moderating role of specific technological adoptions on the ESG-financial performance relationship is another promising avenue. Furthermore, event studies focusing on the market reaction to significant global or regional regulatory announcements on electronics sustainability could provide more direct evidence of regulatory impact. Finally, exploring alternative constructions of ESG factors and testing their robustness across different asset pricing models would contribute to the ongoing debate about ESG's role as a distinct financial factor in the global electronics industry.

7. Summary and Conclusions

This quantitative study examined the financial materiality and market dynamics of ESG performance for 13 multinational electronics firms operating globally, from 2015 to 2025. Panel regression analyses, controlling for Fama-French-Momentum factors, indicated that sustained, long-term total ESG scores and Social (S) pillar scores are positively and significantly associated with stock excess returns for this sample. A Vector Autoregression analysis of a constructed ESG factor suggested its limited dynamic linkage with traditional market risk factors, hinting at distinct ESG risk/return characteristics in this sector.

These findings, contextualized by global sustainability regulations and technological enablers, inform a "Global Regulatory-ESG Financial Salience Model." This model [

1] suggests that firms effectively navigating global regulations and strategically investing in sustained, technologically-enabled ESG performance may achieve favorable financial market recognition. While the empirical evidence is based on a specific sample, it offers insights into the growing financial relevance of ESG for global electronics companies, highlighting the importance of proactive sustainability strategies in an increasingly regulated and technologically evolving world. The study's limitations, particularly sample size, underscore the need for future research with broader global datasets to further validate these observations.

8. Patents

There are no patents resulting from the work reported in this manuscript.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org,

Figure 1: F-test for Poolability Result for the Avg12M_Lagged_G-Score Panel Regression Model.;

Table 1: Panel Model Specification Tests Summary;

Table 2: Summary of Panel Regression Results for the Impact of Analogous Sustainable Technology Adoption Characteristics on Sustainable Value Creation Index (SVCI).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.E.O.O.; methodology, H.E.O.O.; software, H.E.O.O.; validation, H.E.O.O.; formal analysis, H.E.O.O.; investigation, H.E.O.O.; resources, H.E.O.O.; data curation, H.E.O.O.; writing—original draft preparation, H.E.O.O.; writing—review and editing, H.E.O.O.; visualization, H.E.O.O.; supervision, H.E.O.O.; project administration, H.E.O.O.; funding acquisition, H.E.O.O. The author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The Fama-French factor data are publicly available from Kenneth R. French's Data Library. ESG scores were primarily sourced via the yesg Python library [

2]; methodologies of commercial providers [

3,

4] were referenced. Derived datasets and Python scripts are available within the article or as supplementary material associated with this publication and will be made available as supplementary material on the publisher's website upon publication.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| ADF |

Augmented Dickey-Fuller |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| BIC |

Bayesian Information Criterion |

| BP |

Breusch-Pagan |

| CE |

Circular Economy |

| CMA |

Conservative Minus Aggressive (Fama-French Factor) |

| DPP |

Digital Product Passport |

| DW |

Durbin-Watson |

| ESG |

Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| ESPR |

Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation |

| EU |

European Union |

| FE |

Fixed Effects |

| FEVD |

Forecast Error Variance Decomposition |

| FF6 |

Fama-French Six-Factor Model (including Momentum) |

| G-Score |

Governance Score |

| HML |

High Minus Low (Fama-French Factor) |

| HML_ESG |

High Minus Low ESG Factor |

| IRF |

Impulse Response Function |

| MKT_RF |

Market Risk Premium (Fama-French Factor) |

| MSCI |

Morgan Stanley Capital International |

| NRBV |

Natural Resource-Based View |

| OLS |

Ordinary Least Squares |

| REACH |

Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals |

| RMW |

Robust Minus Weak (Fama-French Factor) |

| RoHS |

Restriction of Hazardous Substances |

| RQ |

Research Question |

| S-Score |

Social Score |

| SMB |

Small Minus Big (Fama-French Factor) |

| TSCA |

Toxic Substances Control Act (US) |

| VAR |

Vector Autoregression |

| WEEE |

Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment |

| WML |

Winners Minus Losers (Momentum Factor) |

| XR |

Extended Reality |

References

- Onomakpo, H. E. O. Navigating Global Regulations for Sustainable Electronics: A Strategic Innovation Framework. Int. J. Bus. Financ. Innov. Technol. 2025, 3, 458, Preprints 2025, 2025022318. 10.20944/preprints202502.2318.v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- yesg. (n.d.). yesg: Retrieve ESG data from Yahoo Finance. PyPI - The Python Package Index. Retrieved March 08, 2025, from https://pypi.org/project/yesg/.

- Sustainalytics. (n.d.). ESG Data. Retrieved March 08, 2025, from https://www.sustainalytics.com/esg-data.

- MSCI. (n.d.). ESG Ratings. Retrieved March 08, 2025, from https://www.msci.com/data-and-analytics/sustainability-solutions/esg-ratings.

- Fama, E.F.; French, K.R. A five-factor asset pricing model. J. Financ. Econ. 2015, 116, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabold, S.; Perktold, J.; ChadFulton; et al. statsmodels/statsmodels: Version 0.8.0 Release [Computer software]. Zenodo. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Onomakpo, H.E.O. ESG risk ratings and stock performance in electric vehicle manufacturing: A panel regression analysis using the Fama-French five-factor model. J. Invest. Bank. Financ. 2025, 3, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Lou, Y.; Yan, Q.; Xiong, J.; Luo, J.; Shen, C.; Vayenas, D.V. Insight into the Fe–Ni/biochar composite supported three-dimensional electro-Fenton removal of electronic industry wastewater. J. Environ. Manage. 2023, 325, 116466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtanen, K.; Saari, L.M.; Acerbi, F.; Pinzone, M.; Pachimuthu, D.; Canavesi, R.; Nika, J.; Panagiotopoulou, V.C.; Stavropoulos, P.; Rietveld, E.; Nylander, J. Matching Circularity Improvements and Digital Product Passport Viewpoints: Insights from Three Industrial Case Studies. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2025, 253, 1720–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divyasri; Kumar, D. M.V.; Babu, D.R.; Vedik, B. Recycling of E-waste and Green Electronic Manufacturing. E3S Web Conf. 2025, 619, 01013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suppipat, S.; Hu, A.H. Achieving sustainable industrial ecosystems by design: A study of the ICT and electronics industry in Taiwan. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 369, 133393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakola, L.; Abedi, F.; Nordman, S.; Smolander, M.; Paltakari, J. Smart Tags as Enablers for Digital Product Passports in Circular Electronics Value Chains. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.R.; Kim, S.T.; Lee, H.-H. Green Supply Chain Management Efforts of First-Tier Suppliers on Economic and Business Performances in the Electronics Industry. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevels, A. The challenge of introducing design for the circular economy in the electronics industry: A proposal for metrics. Circ. Econ. 2023, 2, 100051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunde, O.A.; Jian, O.Z.; Tianyu, W.; Khee, W.S.; Qiong, W.; Yuchun, W.; Yucong, X.; Ali, A.J.; Kee, D.M.H. Factors Influencing Consumer Satisfaction: An Analysis of Consumer Electronics. Asia Pac. J. Manag. Educ. 2025, 8, 150–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javeed, S.A.; Teh, B.H.; Ong, T.S.; Lan, N.T.P.; Muthaiyah, S.; Latief, R. The Connection between Absorptive Capacity and Green Innovation: The Function of Board Capital and Environmental Regulation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magni, D.; Palladino, R.; Papa, A.; Cailleba, P. Exploring the journey of Responsible Business Model Innovation in Asian companies: A review and future research agenda. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2024, 41, 1031–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Sun, Q. Evolutionary game analysis of WEEE recycling tripartite stakeholders under variable subsidies and processing fees. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 11584–11599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-C.; Chen, C.-T. Institutional pressure, firm's green resources and green product innovation: evidence from Taiwan's electrical and electronics sector. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2023, 26, 636–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, X.; Wu, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, A.; Wang, H. Can environmental regulation stimulate the regional Porter effect? Double test from quasi-experiment and dynamic panel data models. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 314, 128027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.; Weems, J.; Hua, C.; Dys, S.; Carder, P.; Thomas, K. Assessing Regulatory Stringency for Licensed Assisted Living: A Multifaceted Approach. Innov. Aging 2023, 7, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raff, Z.; Earnhart, D. Employment and environmental protection: The role of regulatory stringency. J. Environ. Manage. 2022, 321, 115896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, I.; Ullah, S.; Sohail, S.; Sohail, M.T. How do digital government, circular economy, and environmental regulatory stringency affect renewable energy production? Energy Policy 2025, 203, 114634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Beule, F.; Dewaelheyns, N.; Schoubben, F.; Struyfs, K.; Van Hulle, C. The influence of environmental regulation on the FDI location choice of EU ETS-covered MNEs. J. Environ. Manage. 2022, 321, 115839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Visentin, F.; Cantin, J.; Santato, C. Active and Dynamic Learning in Sustainable Electronics. J. Chem. Educ. 2024, 101, 3156–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, I.M.; Gimenez, J.C.F.; Xavier, G.T.M.; Ferreira, M.A.B.; Silva, C.M.P.; Camargo, E.R.; Cruz, S.A. Recycling ABS from WEEE with Peroxo-Modified Surface of Titanium Dioxide Particles: Alteration on Antistatic and Degradation Properties. J. Polym. Environ. 2024, 32, 1122–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berube, G.M. Thick-film – a mature technology at the cutting edge of advances in the electronics industry. IMAPSource Proc. 2023, 2022. IMAPS Symposium. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Goel, A.; Chauhan, A.; Singh, S.K. Sustainability of electronic product manufacturing through e-waste management and reverse logistics. Sustain. Futures 2025, 9, 100490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathiyazhagan, K.; Gnanavelbabu, A.; et al. A framework for implementing sustainable lean manufacturing in the electrical and electronics component manufacturing industry: An emerging economies country perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 330, 129852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthess, M.; Kunkel, S.; Xue, B.; Beier, G. Supplier sustainability assessment in the age of Industry 4.0–Insights from the electronics industry. Clean. Logist. Supply Chain 2022, 4, 100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K. Assessment of Innovative Strategies for Zero-Emissions: Refining of Waste Electrical & Electronic Equipment-Specialization in Printed Circuit Boards & Non-Metals. Master's Thesis, Linnaeus University, Växjö, Sweden, 2024. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1883233&dswid=7961. [Google Scholar]

- Debnath, B. Sustainability of WEEE recycling in India. In Re-use and Recycling of Materials; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangwongwanich, A.; Stroe, D.I.; Mi, C.; et al. Sustainability of power electronics and batteries: a circular economy approach. IEEE Power Electron. Mag. 2024, 11, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, W.; Tian, Y.; Ye, G.; Zhu, J. Antenna artificial intelligence: The relentless pursuit of intelligent antenna design [industry activities]. IEEE Antennas Propag. Mag. 2022, 64, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, Y.; Huang, C.; et al. Energy-efficient UAV scheduling and probabilistic task offloading for digital twin-empowered consumer electronics industry. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2024, 70, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabi, A.; Yari, K.; Van Driel, W.D.; et al. AI-Driven Digital Twin for Health Monitoring of Wide Band Gap Power Semiconductors. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 10th Workshop on Wide Bandgap Power Devices and Applications (WiPDA), College Park, MD, USA, 5-7 November 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borole, Y.; Borkar, P.; Raut, R.; Balpande, V.P.; Chatterjee, P. Digital Twins: Internet of Things, Machine Learning, and Smart Manufacturing; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/book/10781480. [Google Scholar]

- Gaikwad, A. Reliability estimation and lifecycle assessment of electronics in extreme conditions. SSRN Electron. J. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mula, J.; Sanchis, R.; de la Torre, R.; Becerra, P. Extended reality and metaverse technologies for industrial training, safety and social interaction. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2024, 58, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Lefranc, P.; Rio, M. Effective ecodesign implementation in power electronics: a method based on functional blocks. Cogent Eng. 2024, 11, 2382232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suppipat, S.; Hu, A.H. A scoping review of design for circularity in the electrical and electronics industry. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. Adv. 2022, 13, 200073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahr, C. The communication of circular business models and the need for collaboration in the electronics industry. Master's Thesis, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, 2024. http://hdl.handle.net/10138/585327. [Google Scholar]

- Banik, A.; Taqi, H.M.M.; Ali, S.M.; Ahmed, S.; et al. Critical success factors for implementing green supply chain management in the electronics industry: an emerging economy case. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2022, 25, 1013–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomez, F.; Helbling, H.; Almanza, M.; Soupremanien, U.; et al. State of the art of research towards sustainable power electronics. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Extend sustainable new product development to suppliers: cases from the US computer and electronic industry. Int. J. Logist. Econ. Glob. 2020, 9, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA). Available online: https://www.epa.gov/laws-regulations/summary-toxic-substances-control-act.

- Ministry of the Environment, Japan. Basic Act on Establishing a Sound Material-Cycle Society (Law No. 110 of 2000). Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/en/recycle/smcs/.

- Government of Canada. Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (S.C. 1999, c. 33). Available online: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/c-15.31/.

- Schluep, M.; Hagelueken, C.; Kuehr, R.; et al. Recycling – from E-waste to Resources. United Nations Environment Programme and United Nations University: Bonn, Germany, 2009. (General WEEE in developing countries).

- Godfrey, L.; Oelofse, S. Historical review of waste management and recycling in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2017, 113, #2016–0274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L. A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 986–1014, https://www.jstor.org/stable/258963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; van der Linde, C. Toward a New Conception of the Environment-Competitiveness Relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayadi, F.S.; Mlanga, S.; Ikpor, M.I.; Nnachi, R.A. Empirical test of Pollution Haven Hypothesis in Nigeria using autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) model. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2019, 10, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New Zealand Ministry for the Environment. Waste Minimisation Act 2008. Available online: https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2008/0089/latest/dlm999802.html.

- Kshetri, N. Blockchain’s roles in meeting key supply chain management objectives. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 39, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benešová, A.; Hirman, M.; Steiner, F.; et al. Towards Sustainable Electronics: Unveiling the Nexus of Circular Economy, Global Policies and Industry Impacts. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Spring Seminar on Electronics Technology (ISSE), Vienna, Austria, 14-17 May 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambec, S.; Cohen, M.A.; Elgie, S.; Lanoie, P. The Porter Hypothesis at 20: Can Environmental Regulation Enhance Innovation and Competitiveness? Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2013, 7, 2–22, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1093/reep/res016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The impact of corporate sustainability on organizational processes and performance. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 2835–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Directive 2011/65/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 8 June 2011 on the restriction of the use of certain hazardous substances in electrical and electronic equipment (RoHS Recast). Official Journal of the European Union L 174/88. https://echa.europa.eu/legislation-profile/-/legislationprofile/EU-ROHS.

- National Conference of State Legislatures. Electronic Waste Recycling State Legislation. Available online:.

- World Economic Forum. A New Circular Vision for Electronics: Time for a Global Reboot; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Global Material Resources Outlook to 2060: Economic Drivers and Environmental Consequences; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme. Global E-waste Monitor 2020: Quantities, Flows, and the Circular Economy Potential. United Nations University/UNITAR: Bonn/Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Alomar, T.A. A Cross-country Study of Stakeholder Pressure on Oil and Gas Companies' Environmental Performance and Disclosures. Ph.D. Thesis, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Demir Dogan, T.; Akbas, D. The Role of Environmental Regulations on Green Transition: The Case of Swedish Electronics Industry. Master's Thesis, Jönköping University, Jönköping, Sweden, 2023. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1775222&dswid=7265. [Google Scholar]

- Cicerelli, F.; Ravetti, C. Sustainability, resilience and innovation in industrial electronics: a case study of internal, supply chain and external complexity. J. Econ. Interact. Coord. 2024, 19, 343–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaack, P.; Gruin, J. From shadow banking to digital financial inclusion: China's rise and the politics of epistemic contestation within the Financial Stability Board. Rev. Int. Polit. Econ. 2021, 28, 779–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Monthly returns of the constructed HML_ESG factor, MKT_RF, SMB, and HML factors over the sample period.

Figure 1.

Monthly returns of the constructed HML_ESG factor, MKT_RF, SMB, and HML factors over the sample period.

Figure 2.

Kernel density estimates for the monthly returns of HML_ESG, MKT_RF, SMB, and HML factors.

Figure 2.

Kernel density estimates for the monthly returns of HML_ESG, MKT_RF, SMB, and HML factors.

Figure 3.

Scatter plot matrix showing pairwise relationships between HML_ESG, MKT_RF, SMB, and HML factors.

Figure 3.

Scatter plot matrix showing pairwise relationships between HML_ESG, MKT_RF, SMB, and HML factors.

Figure 4.

Impulse responses of the HML_ESG factor to one standard deviation shocks in the Fama-French-Momentum factors. Dotted lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 4.

Impulse responses of the HML_ESG factor to one standard deviation shocks in the Fama-French-Momentum factors. Dotted lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 5.

Impulse responses of Fama-French-Momentum factors to a one standard deviation shock in the HML_ESG factor. Dotted lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 5.

Impulse responses of Fama-French-Momentum factors to a one standard deviation shock in the HML_ESG factor. Dotted lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 6.

Selected impulse responses among Fama-French-Momentum factors to one standard deviation shocks in other market factors. Dotted lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 6.

Selected impulse responses among Fama-French-Momentum factors to one standard deviation shocks in other market factors. Dotted lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 7.

Conceptual Global Regulatory-ESG Financial Salience Model.

Figure 7.

Conceptual Global Regulatory-ESG Financial Salience Model.

Table 1.

Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) Test for Stationarity of VAR Input Variables.

Table 1.

Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) Test for Stationarity of VAR Input Variables.

| Variable |

ADF Statistic |

P-value |

Conclusion |

| HML_ESG |

-10.987 |

0.000 |

Stationary |

| MKT_RF |

-11.543 |

0.000 |

Stationary |

| SMB |

-10.312 |

0.000 |

Stationary |

| HML |

-8.765 |

0.001 |

Stationary |

| RMW |

-9.987 |

0.000 |

Stationary |

| CMA |

-9.123 |

0.000 |

Stationary |

| WML |

-10.501 |

0.000 |

Stationary |

Table 2.

Durbin-Watson Statistics for VAR (1) Model Residuals.

Table 2.

Durbin-Watson Statistics for VAR (1) Model Residuals.

| Variable |

Durbin-Watson |

| HML_ESG |

2.0327 |

| MKT_RF |

2.0122 |

| SMB |

1.9819 |

| HML |

2.0625 |

| RMW |

2.0070 |

| CMA |

2.0438 |

| WML |

2.0372 |

Table 3.

Panel Model Specification Tests Summary.

Table 3.

Panel Model Specification Tests Summary.

| Test |

Statistic |

P-value/Note |

Conclusion |

| F-test (Entity FE vs Pooled OLS) |

0.876 |

0.5713 |

Entity FE not significant |

| Hausman (Informal) |

Comparison |

FE:0.0000, RE:0.0000. Diff:0.0000 |

Choice less clear (F-test not sig.) |

| Breusch-Pagan (Entity FE resid) |

LM:6.99 |

Pval:0.430 |

Homoskedasticity |

Table 4.

Summary of Panel Regression Results: Excess Returns on Key Lagged ESG Scores (Two-Way Fixed Effects with FF6 Controls, N=1519).

Table 4.

Summary of Panel Regression Results: Excess Returns on Key Lagged ESG Scores (Two-Way Fixed Effects with FF6 Controls, N=1519).

| ESG Variable |

Coefficient |

Std. Error |

T-stat |

P-value |

Significant (5%) |

| Lagged_Total-Score |

0.0006 |

0.0002 |

2.3222 |

0.0204 |

TRUE |

| Lagged6M_Total-Score |

0.0006 |

0.0002 |

2.7619 |

0.0058 |

TRUE |

| Avg12M_Lagged_Total-Score |

0.0008 |

0.0002 |

4.6279 |

0.0000 |

TRUE |

| Lagged_S-Score |

0.0005 |

0.0002 |

2.1862 |

0.0290 |

TRUE |

| Lagged6M_S-Score |

0.0006 |

0.0002 |

2.4464 |

0.0146 |

TRUE |

| Avg12M_Lagged_S-Score |

0.0007 |

0.0002 |

3.1168 |

0.0019 |

TRUE |

Table 5.

Sub-period Analysis Summary: Two-Way FE Regressions (ESG only models).

Table 5.

Sub-period Analysis Summary: Two-Way FE Regressions (ESG only models).

| Period |

ESG_Variable |

Coefficient |

P_Value |

Significant_5pct |

N_Obs |

R_squared |

| First Half |

Lagged_Total-Score |

0.0000 |

0.8813 |

FALSE |

793 |

1.01E-05 |

| First Half |

Lagged6M_Total-Score |

0.0007 |

0.3497 |

FALSE |

793 |

0.0010 |

| First Half |

Avg12M_Lagged_Total-Score |

0.0006 |

0.4866 |

FALSE |

793 |

0.0006 |

| First Half |

Lagged_S-Score |

0.0004 |

0.3257 |

FALSE |

793 |

0.0012 |

| First Half |

Lagged6M_S-Score |

0.0006 |

0.3370 |

FALSE |

793 |

0.0012 |

| First Half |

Avg12M_Lagged_S-Score |

0.0008 |

0.2127 |

FALSE |

793 |

0.0016 |

| Second Half |

Lagged_Total-Score |

0.0007 |

0.3958 |

FALSE |

726 |

0.0007 |

| Second Half |

Lagged6M_Total-Score |

0.0002 |

0.4036 |

FALSE |

726 |

0.0002 |

| Second Half |

Avg12M_Lagged_Total-Score |

0.0011 |

0.1923 |

FALSE |

726 |

0.0018 |

| Second Half |

Lagged_S-Score |

0.0026 |

0.0524 |

FALSE |

726 |

0.0016 |

| Second Half |

Lagged6M_S-Score |

0.0005 |

0.4352 |

FALSE |

726 |

0.0010 |

| Second Half |

Avg12M_Lagged_S-Score |

0.0020 |

0.3647 |

FALSE |

726 |

0.0037 |

Table 6.

Granger Causality Tests from VAR (1) Model.

Table 6.

Granger Causality Tests from VAR (1) Model.

| Causality Direction |

F-Stat |

P-Value |

Significant (5%) |

| MKT_RF, SMB, HML, RMW, CMA, WML -> HML_ESG |

0.61 |

0.723 |

FALSE |

| HML_ESG -> MKT_RF |

0.63 |

0.427 |

FALSE |

| HML_ESG -> SMB |

0.99 |

0.321 |

FALSE |

| HML_ESG -> HML |

0.6 |

0.438 |

FALSE |

| HML_ESG -> RMW |

0.03 |

0.853 |

FALSE |

| HML_ESG -> CMA |

0.12 |

0.73 |

FALSE |

| HML_ESG -> WML |

1.22 |

0.27 |

FALSE |

Table 7.

Forecast Error Variance Decomposition (FEVD) for HML_ESG (Selected Horizons).

Table 7.

Forecast Error Variance Decomposition (FEVD) for HML_ESG (Selected Horizons).

| Period |

HML_ESG |

MKT_RF |

SMB |

HML |

RMW |

CMA |

WML |

| 0 |

1.0000 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

| 1 |

0.9684 |

0.0055 |

0.0023 |

0.0002 |

0.0031 |

0.0157 |

0.0049 |

| 2 |

0.9674 |

0.0056 |

0.0023 |

0.0002 |

0.0035 |

0.0157 |

0.0052 |

| 3 |

0.9673 |

0.0056 |

0.0023 |

0.0003 |

0.0035 |

0.0157 |

0.0052 |

| 4 |

0.9673 |

0.0056 |

0.0023 |

0.0003 |

0.0035 |

0.0157 |

0.0052 |

| 5 |

0.9673 |

0.0056 |

0.0023 |

0.0003 |

0.0035 |

0.0157 |

0.0052 |

| 6 |

0.9673 |

0.0056 |

0.0023 |

0.0003 |

0.0035 |

0.0157 |

0.0052 |

| 7 |

0.9673 |

0.0056 |

0.0023 |

0.0003 |

0.0035 |

0.0157 |

0.0052 |

| 8 |

0.9673 |

0.0056 |

0.0023 |

0.0003 |

0.0035 |

0.0157 |

0.0052 |

| 9 |

0.9673 |

0.0056 |

0.0023 |

0.0003 |

0.0035 |

0.0157 |

0.0052 |

| 10 |

0.9673 |

0.0056 |

0.0023 |

0.0003 |

0.0035 |

0.0157 |

0.0052 |

| 11 |

0.9673 |

0.0056 |

0.0023 |

0.0003 |

0.0035 |

0.0157 |

0.0052 |

Table 8.

OLS Regression of HML_ESG Factor on FF6 Factors (Alpha Test).

Table 8.

OLS Regression of HML_ESG Factor on FF6 Factors (Alpha Test).

| Variable |

coef |

std err |

z |

P>|z| |

25th percentile |

Upper 95% CI |

| const |

0.0061 |

0.0040 |

1.4740 |

0.1410 |

-0.0020 |

0.0140 |

| MKT_RF |

-0.1657 |

0.0900 |

-1.8330 |

0.0670 |

-0.3430 |

0.0110 |

| SMB |

0.2929 |

0.2420 |

1.2100 |

0.2260 |

-0.1820 |

0.7670 |

| HML |

0.0747 |

0.2670 |

0.2800 |

0.7790 |

-0.4480 |

0.5980 |

| RMW |

0.6050 |

0.3200 |

1.8880 |

0.0590 |

-0.0230 |

1.2330 |

| CMA |

0.0963 |

0.3730 |

0.2580 |

0.7960 |

-0.6350 |

0.8280 |

| WML |

-0.2878 |

0.2040 |

-1.4100 |

0.1590 |

-0.6880 |

0.1120 |

| Notes: N=121. R-squared=0.065. Durbin-Watson=1.881. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).