Submitted:

29 May 2025

Posted:

29 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

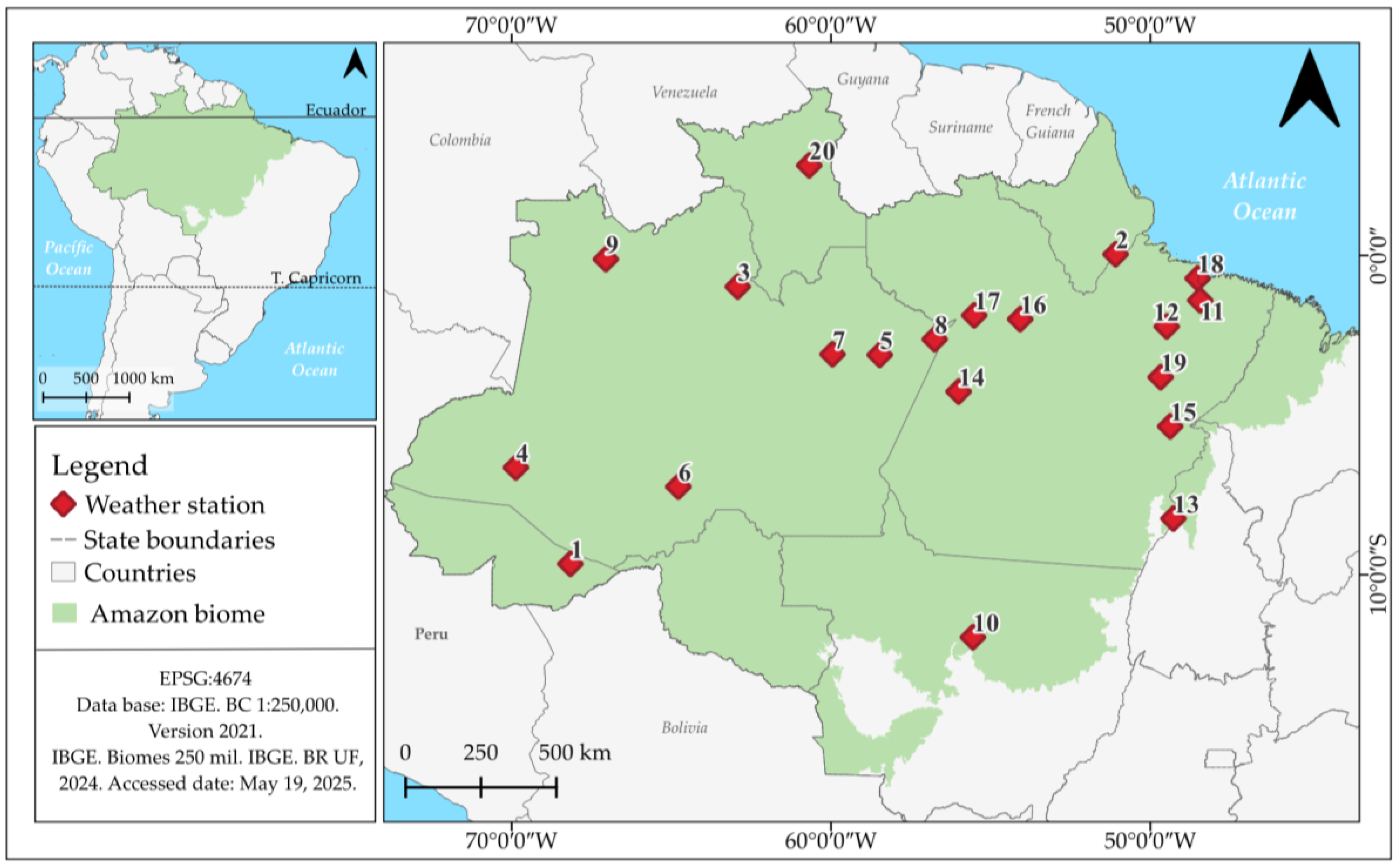

2.1. Study Area

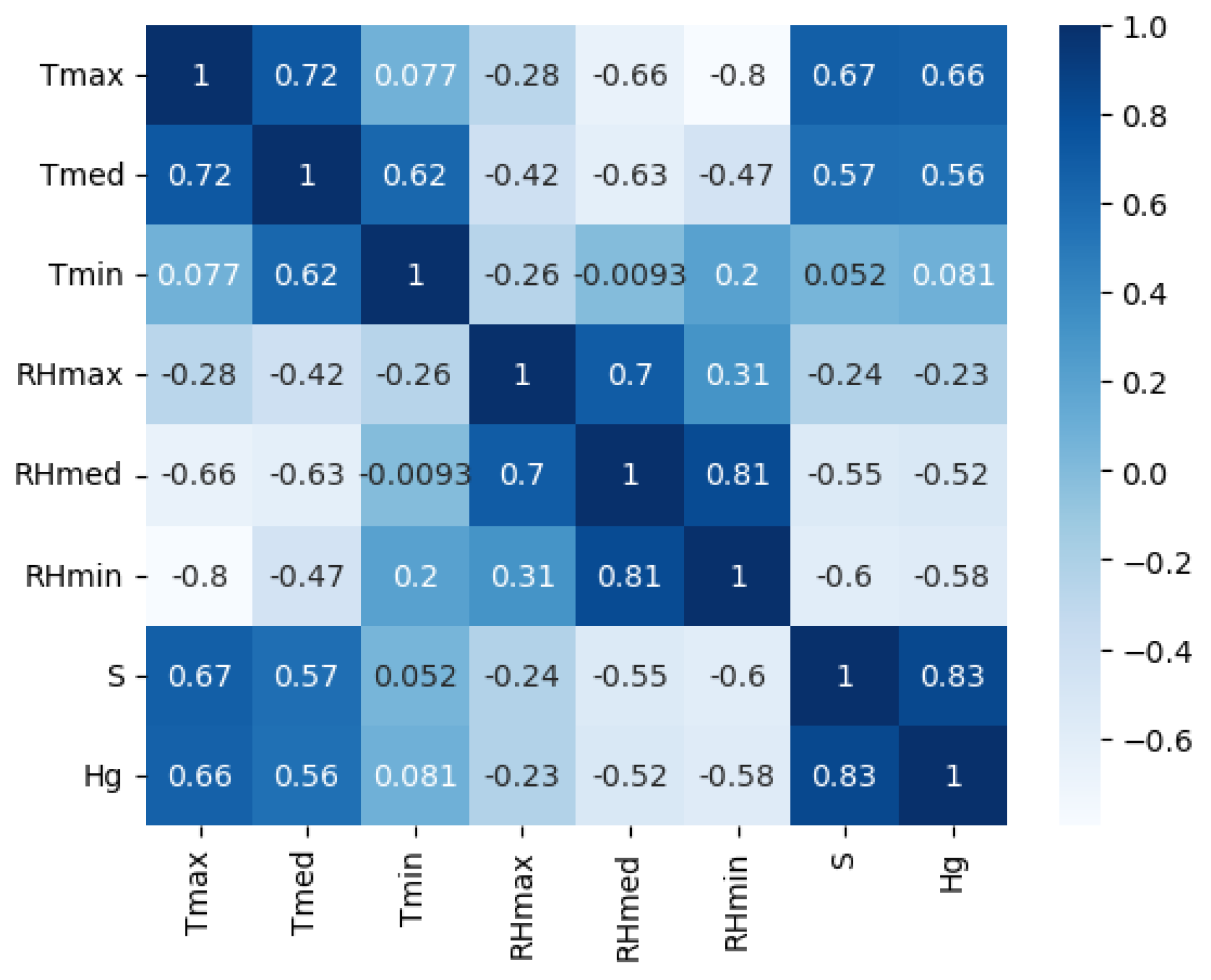

2.2. Data Analysis

2.3. Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML)

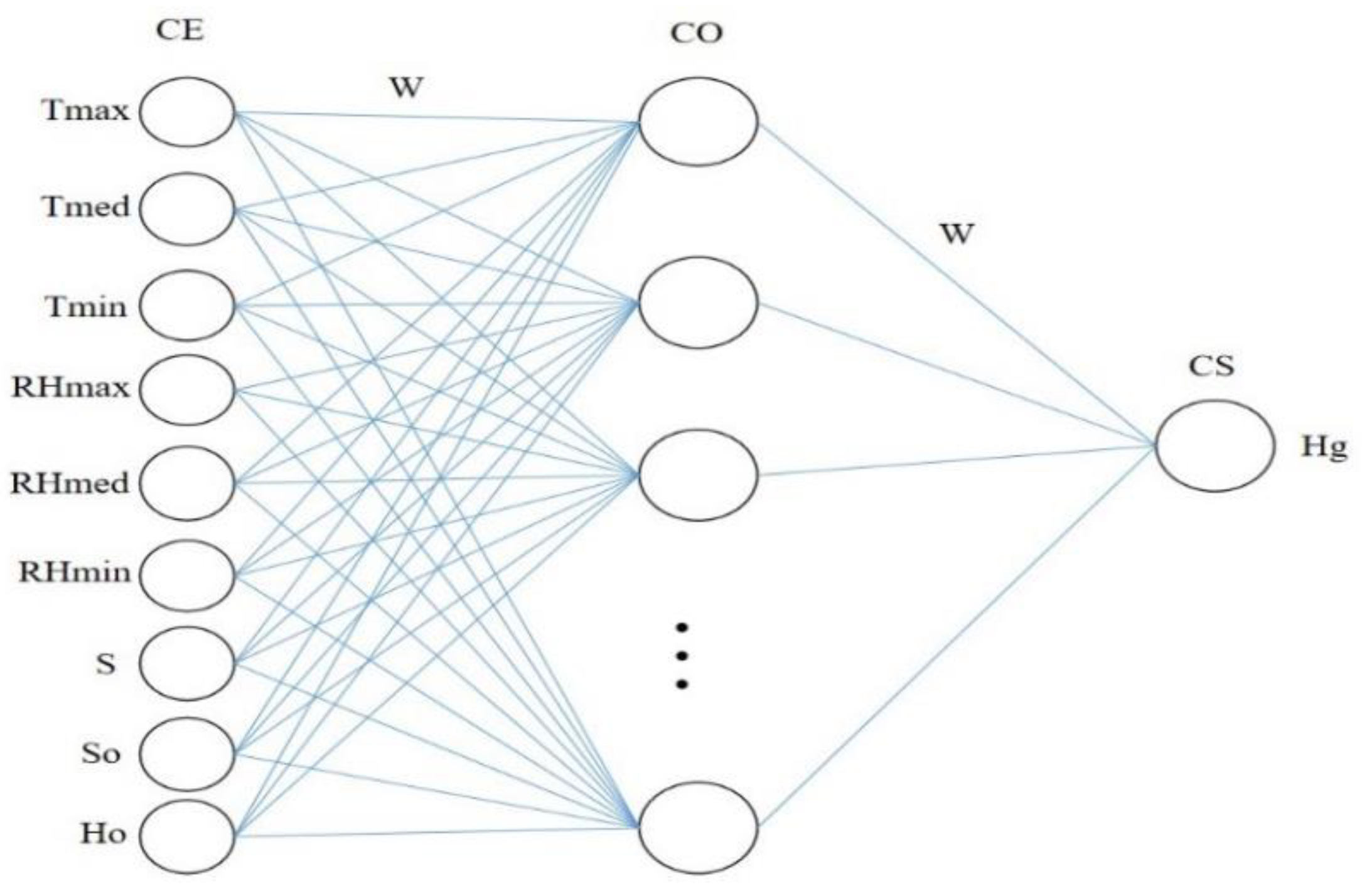

2.3.1. Artificial Neural Network (ANN) - Multilayer Perceptron (MLP)

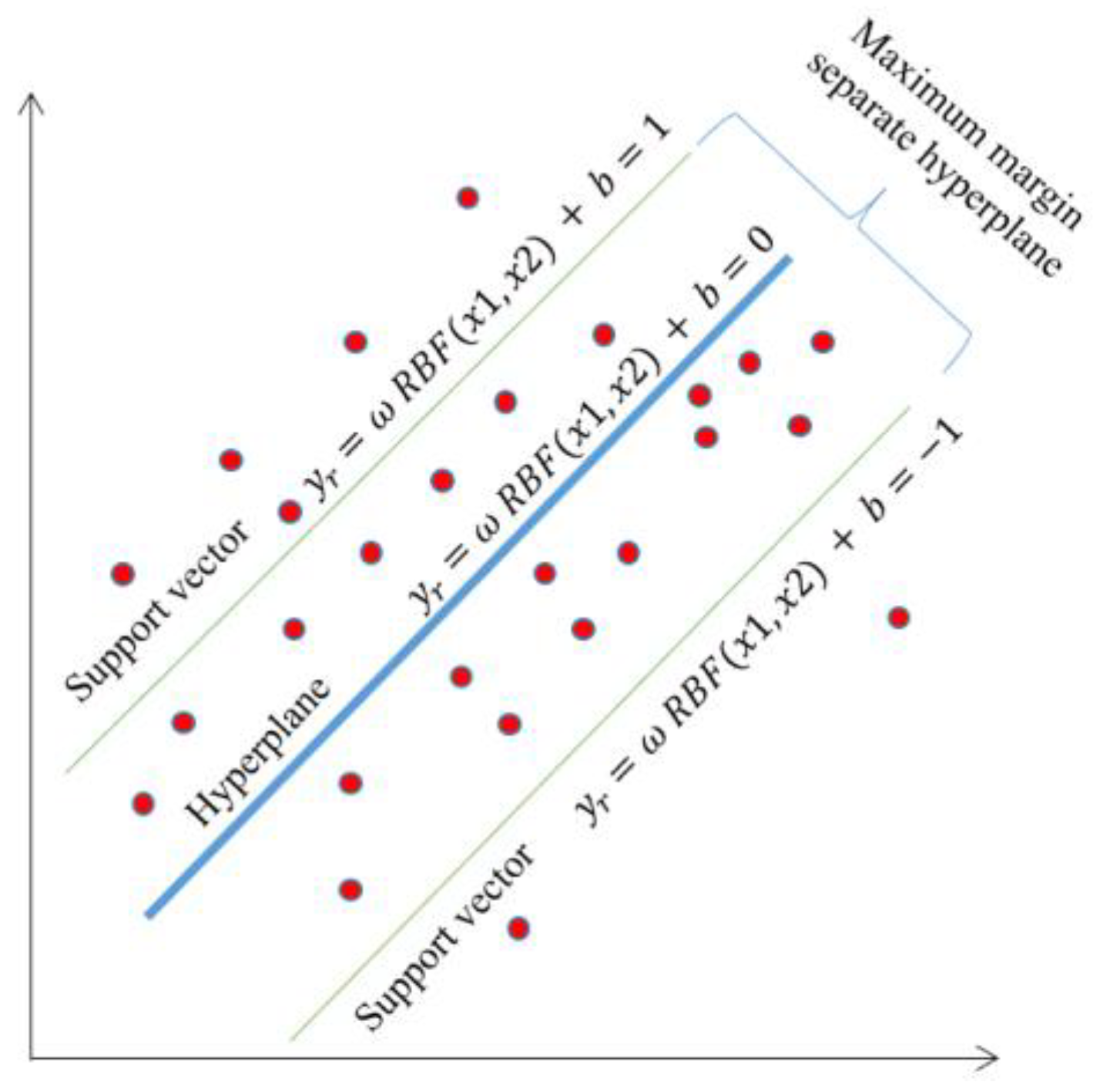

2.3.2. Support Vector Machine (SVM)

2.3.3. Structure of the Evaluated ML Models

2.4. Empirical Models of Hg Estimates

2.5. Performance Analysis and Statistical Indicators

- 1)

- Obtain the 10,000 residual samples of the analyzed models, , of size N, with replacement;

- 2)

- Construction of the bootstrap estimator, by constructing probability density functions of interest in each simulated bootstrap sample for residuals of the models in resamples (Equation 21);

- 3)

- Calculation of the mean () (Equation 22) and standard deviation () (Equation 23) statistics of the estimator :

- 4)

- Calculation of confidence intervals with 99% confidence for the estimate of the mean (), and with standard deviation () of the estimator , for each of the model residuals (Equation 24):

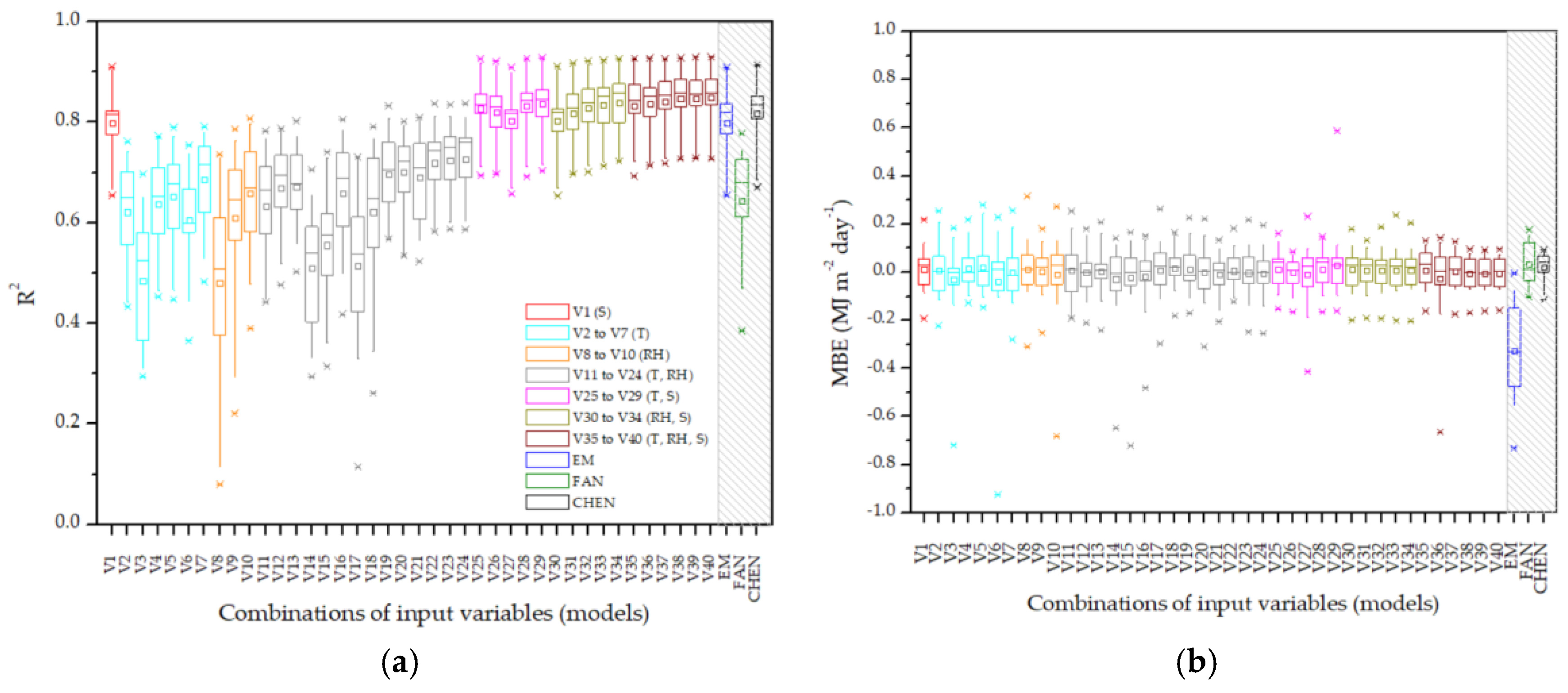

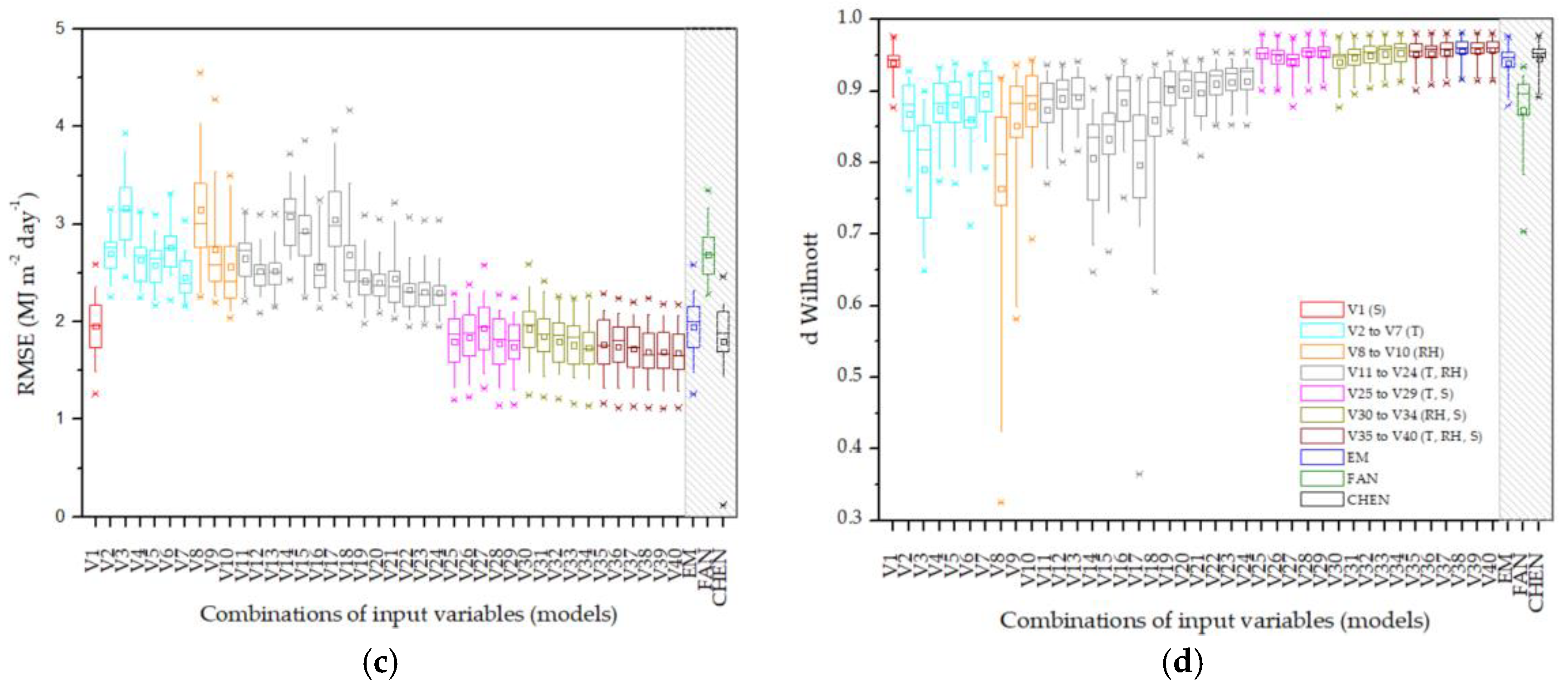

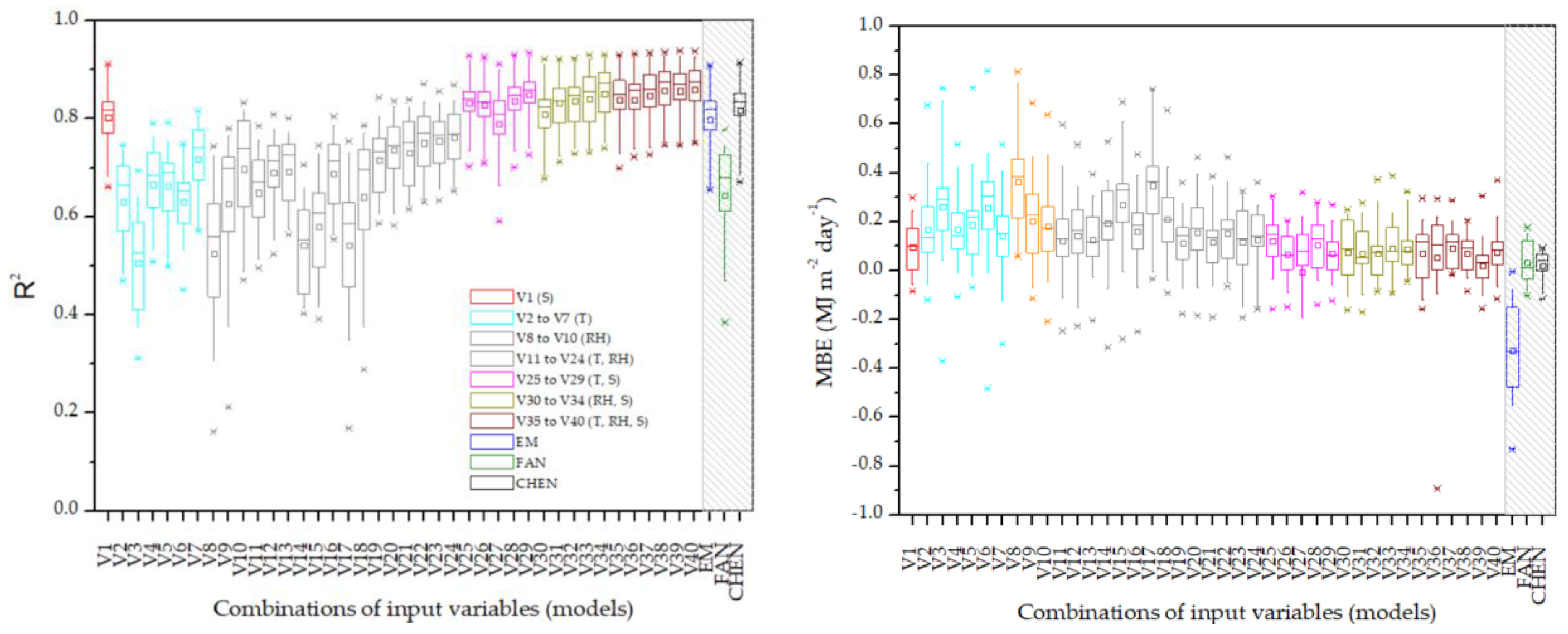

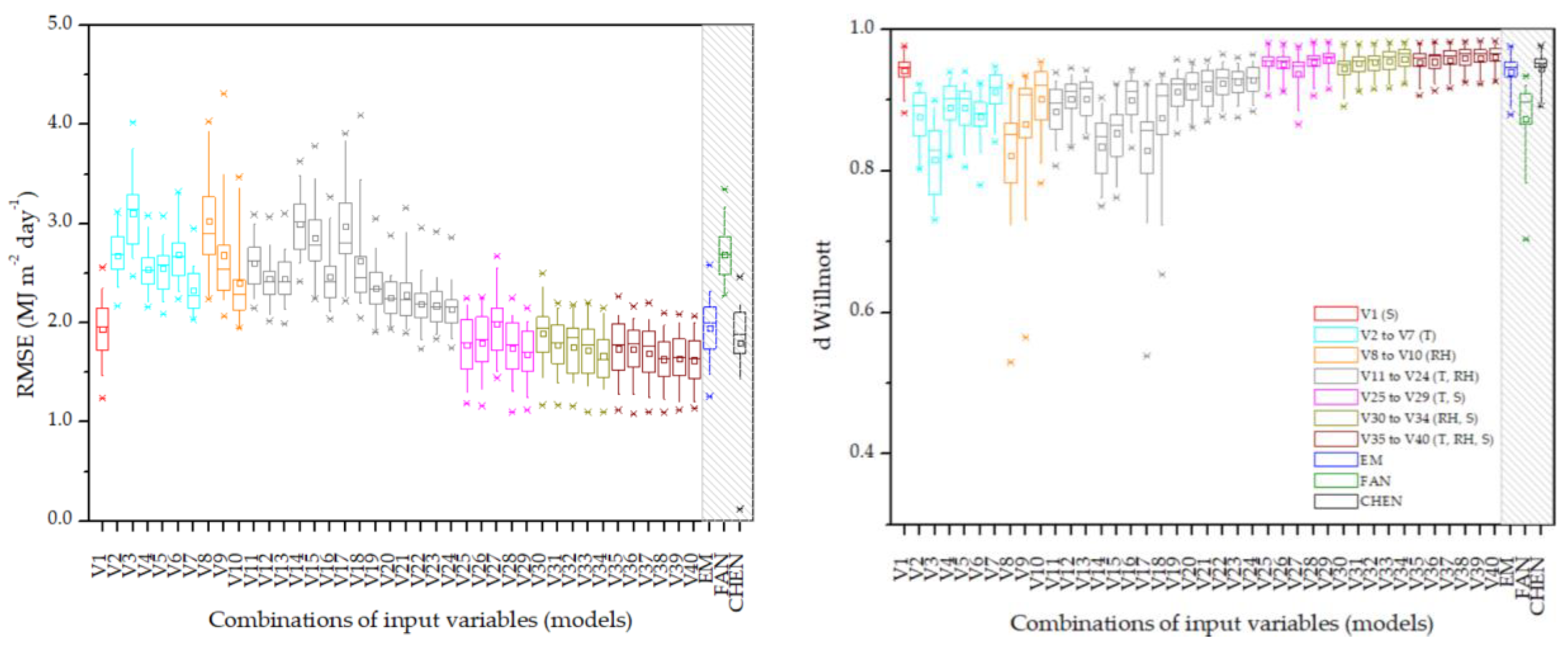

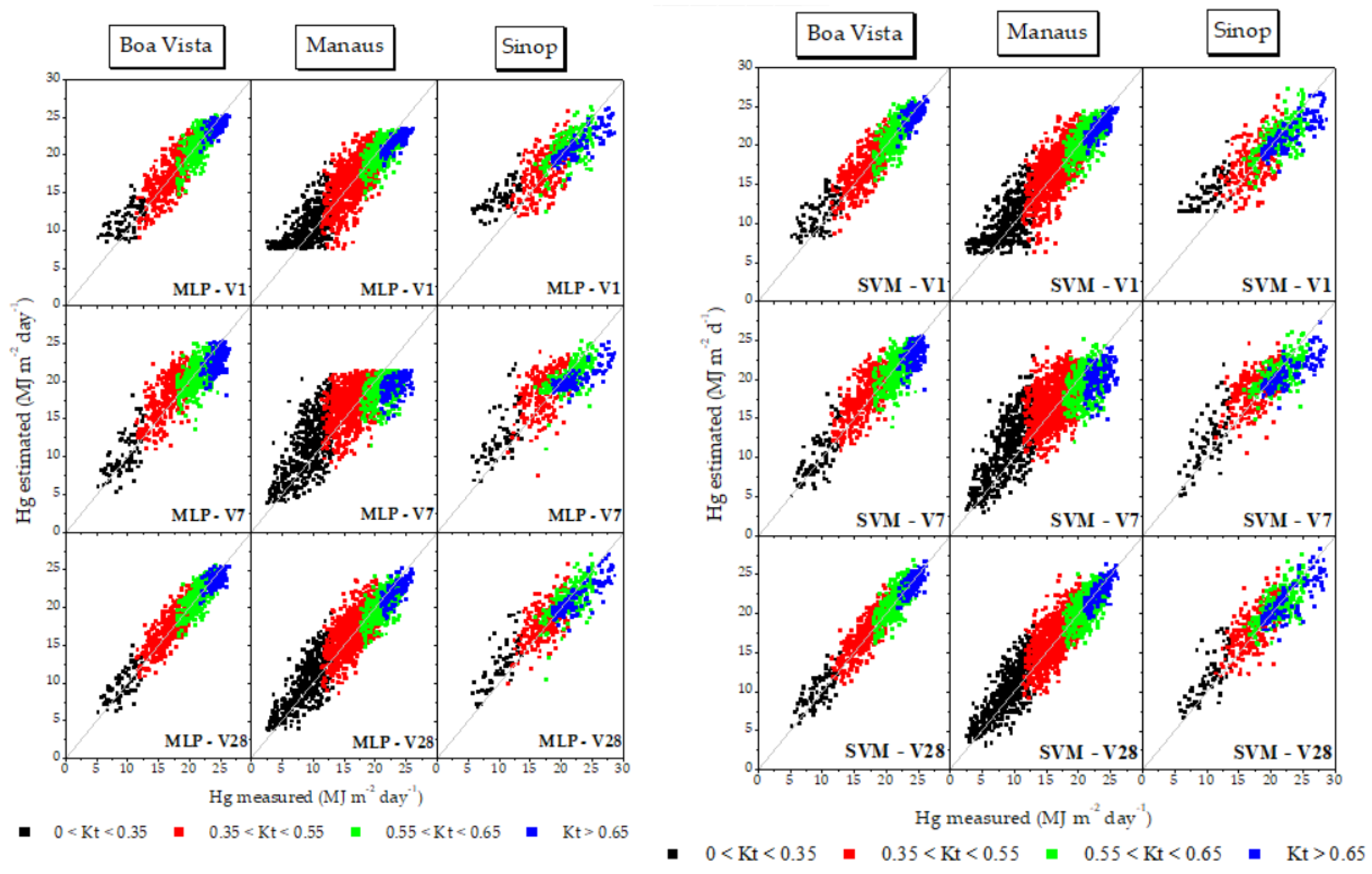

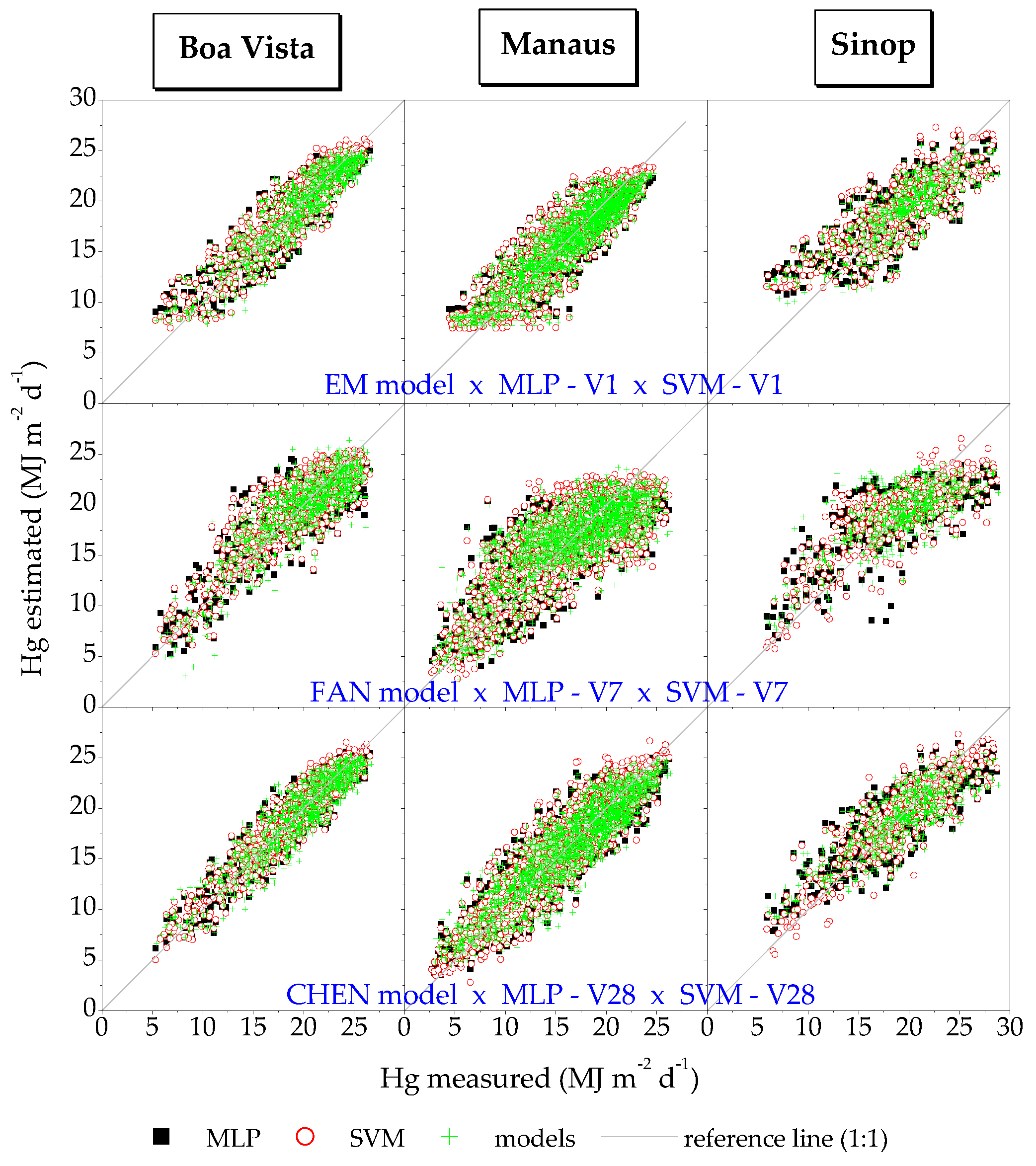

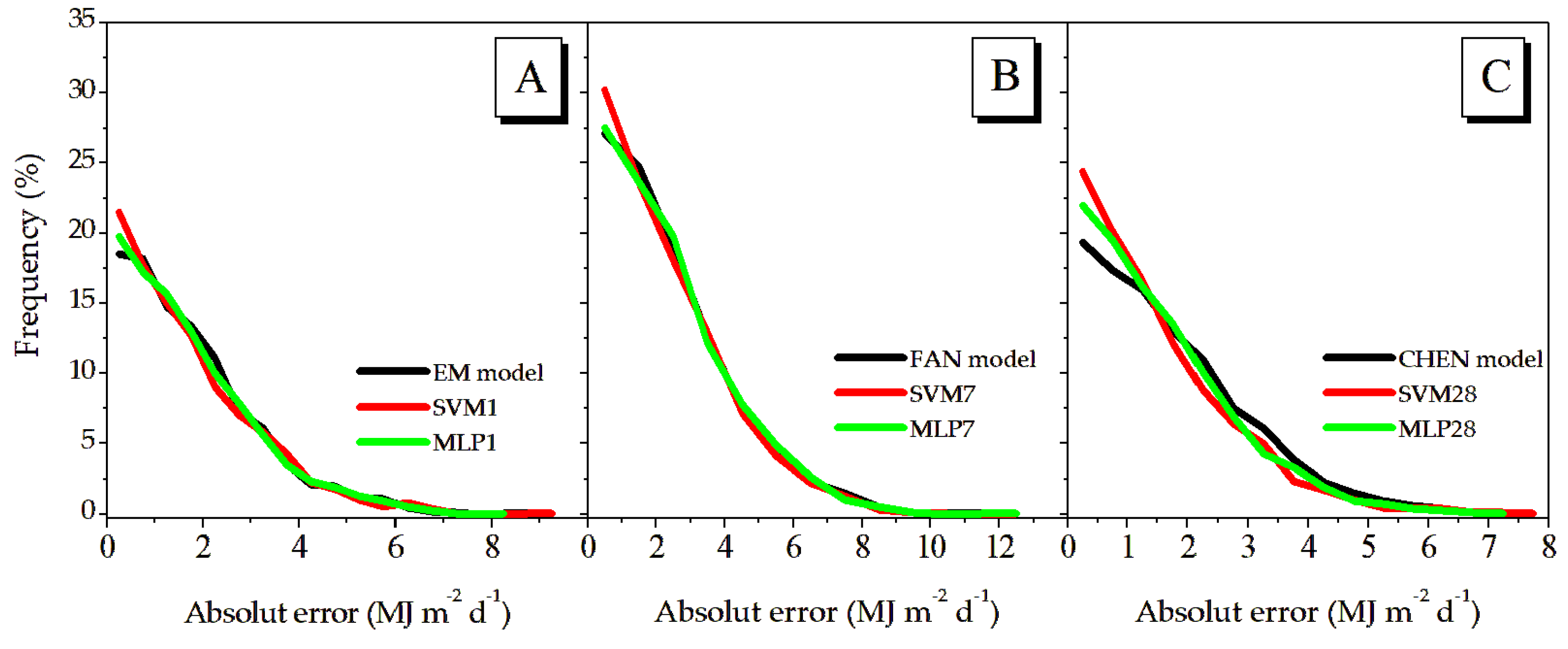

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Global Radiation in Agriculture

4.2. Machine Learning Estimates of Global Radiation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ABSOLAR. Associação Brasileira de Energia Fotovoltaica. Overview of solar photovoltaics in Brazil and the world. Available online: https://www.absolar.org.br/mercado/infografico/. Accessed 17 Apr 2025.

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop evapotranspiration guidelines for computing crop water requirements. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 1998. 333p. Available online: https://www.climasouth.eu/sites/default/files/FAO%2056.pdf. Accessed 17 Apr 2025. (FAO Irrigation and Drainage, 56).

- Fan, J.; Wu, L.; Zhang, F.; Cai, H.; Zeng, W.; Wang, X.; Zou, H. Empirical and machine learning models for predicting daily global solar radiation from sunshine duration: A review and case study in China. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2019, 100, 186-212. [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Liu, J.; Xu, F.; Zhang, T.; Chen, S.; Sun, Z.; Zheng, W.; Wang, R.; He, L.; Feng, H.; Yu, Q.; He, J. Improving solar radiation estimation in China based on regional optimal combination of meteorological factors with machine learning methods. Energy Conversion and Management 2020, 220, e113111. [CrossRef]

- Agbulut, Ü.; Gürel, A.E.; Biçen, Y. Prediction of daily global solar radiation using different machine learning algorithms: Evaluation and comparison. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 135, e110114. [CrossRef]

- Bellido-Jiménez, J.; Gualda, J.E.; García-Marín, A.P. Assessing new intra-daily temperature-based machine learning models to outperform solar radiation predictions in different conditions. Applied Energy 2021, 298, e117211. [CrossRef]

- Bounoua, Z.; Chahidi, L.O.; Mechaqrane, A. Estimation of daily global solar radiation using empirical and machine-learning methods: A case study of five Moroccan locations. Sustainable Materials and Technologies 2021, 28, e261. [CrossRef]

- Gürel, A.E.; Agbulut, Ü.; Bakir, H.; Ergün, A.; Yildiz, G. A state of art review on estimation of solar radiation with various models. Heliyon 2023, 9(2), e13167. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, D.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y. A review on global solar radiation prediction with machine learning models in a comprehensive perspective. Energy Conversion and Management 2021, 235(1), e113960. [CrossRef]

- Nawab, F.; Hamid, A.S.A.; Ibrahim, A.; Sopian, K.; Fazlizan, A.; Fauzan, M.F. Solar irradiation prediction using empirical and artificial intelligence methods: A comparative review. Heliyon 2023, 9(6), e17038. [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.L.F.; Teixeira, M.J.; Almeida, F.V.; Corrêa, P.L.P. Neural Networks Forecast Models Comparison for the Solar Energy Generation in Amazon Basin. IEEE Access 2024, 12, e3358339. [CrossRef]

- Quej, V.H.; Almorox, J.; Arnaldo, J.A.; Saito, L. ANFIS, SVM and ANN soft-computing techniques to estimate daily global solar radiation in a warm sub-humid environment. Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics 2017, 155, 62-70. [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.B.P.; Escobedo, J.F.; Rossi, T.J.; Santos, C.M.; Silva, S.H.M.G. Performance of the Angstrom-Prescott Model (A-P) and SVM and ANN techniques to estimate daily global solar irradiation in Botucatu/SP/Brazil. Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics 2017, 160, 11-23. [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulos, V.; Papamichail, D.M.; Aschonitis, V.G.; Antonopoulos, A.V. Solar radiation estimation methods using ANN and empirical models. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2019, 160, 160-167. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Gong, D.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, S.; Zhao, L.; Cui, N. Evaluation of temperature-based machine learning and empirical models for predicting daily global solar radiation. Energy Conversion and Management 2019, 198, e15. [CrossRef]

- Husain, S.; Khan, U.A. Machine Learning models to predict diffuse solar based on diffuse fraction and diffusion coefficient models for humid-subtropical climatic zone of India. Cleaner Engineering and Technology 2021, 5, e100262. [CrossRef]

- Voyant, C.; Notton, G.; Kalogirou, S.; Nivet, M-L.; Paoli, C.; Motte, F.; Fouilloy, A. Machine learning methods for solar radiation forecasting: A review. Renewable Energy 2017, 105, 569-582. [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.M.; Teramoto, É.T.; Souza, A.; Aristone, F.; Ihaddadene, R. Several models to estimate daily global solar irradiation adjustment and evaluation. Arabian Journal of Geosciences 2021, 14(4), e286. [CrossRef]

- Kaba, K.; Sarigül, M.; Avci, M.; Kandirmaz, H.M. Estimation of daily global solar radiation using deep learning model. Energy 2018, 162, 126-135. [CrossRef]

- Küçüktopçu, E.; Gemek, B.; Simsek, H. Comparative analysis of single and hybrid machine learning models for daily solar radiation. Energy Reports 2024, 11, 3256-3266. [CrossRef]

- Marzouq, M.; Bounoua, Z.; Fadili, H.E.; Mechaqrane, A.; Zenkouar, K. New daily global irradiation estimation model based on automatic selection of input parameters using evolutionary neural networks. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 209(1), 1105-1118, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Band, S.; Karami, H.; Ehteram, M.; Chau, K-W.; Zhang, Q. Solar radiation prediction using improved soft computing models for semi-arid, Slightly-arid and humid climates. Alexandria Engineering Journal 2022, 61, 10631-10657. [CrossRef]

- Woldegiyorgis, T.A.; Benti, N.E.; Chaka, N.E.; Semie, A.G.; Jemberie, A.A. Estimating solar radiation using artificial neural networks: A case study of Fiche, Oroma, Ethiopia. Cogent Engineering 2023, 10(1), e2220489. [CrossRef]

- Martim, C.C.; Paulista, R.S.; Castagna, D.; Borella, D.R.; Almeida, F.T.; Damian, J.G.R.; Souza, A.P. Daily Estimates of global radiation in the Brazilian Amazon from simplified models. Atmosphere 2024, 15(11), e1397. [CrossRef]

- Badescu, V. Assessing the performance of solar radiation computing models and model selection procedures. Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics 2013, 105-106, 119-134. [CrossRef]

- Teke, A.; Yıldırım, H.B.; Çelik, O. Evaluation and performance comparison of different models for the estimation of solar radiation. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2015, 50, 1097-1107. [CrossRef]

- IBGE (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics). Continuous cartographic bases [database]. (2021). Available online: https://downloads.ibge.gov.br/index.htm. Accessed: 19 May 2025.

- Alvares, C.A.; Stape, J.L.; Sentelhas, P.C.; Gonçalves, J.L.M.; Sparovek, G. Köppen’s climate classification map for Brazil. Meteorologische Zeitschrift 2013, 22(6), 711-728. [CrossRef]

- Vapnik, V.N. The nature of Statistical learning theory. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1995. 201p.

- Shevade, S.K.; Keerthi, S.S.; Bhattacharyya, C.; Murthy, K.R.K. Improvements to the SMO Algorithm for SVM Regression. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks 2000, 11(5), 1188-1193. [CrossRef]

- Elagib, N.A.; Mansell, M.G. New approaches for estimating global solar radiation across Sudan. Energy Conversion and Management 2000, 41, 419–434. [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Chen, B.; Wu, L.; Zhang, F.; Lu, X.; Xiang, Y. Evaluation and development of temperature-based empirical models for estimating daily global solar radiation in humid regions. Energy 2018, 144, 903–914. [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Ersi, K.; Yang, J.; Lu, S.; Zhao, W. Validation of five global radiation models with measured daily data in China. Energy Conversion and Management 2004, 45, 1759–1769. [CrossRef]

- Efron, B. Bootstrap Methods: Another Look at the Jackknife. In: Kotz, S., Johnson, N.L. (Eds) Breakthroughs in Statistics. Springer Series in Statistics. Springer, New York, NY. 1992. p. 569-593. [CrossRef]

- Thibshirani, R.; Leisch, F. bootstrap: Functions for the book An Introdution to the bootstrap. R package version 2019.6; 2019. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/bootstrap/index.html. Accessed: 27 May 2025.

- Canty, A.; Ripley, B. boot: Bootstrap R (S-Plus) functions. R package version 1.3-31 2021. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/bootstrap/index.html.

- Akaike, H.A. New Look at the Statistical Model identification. IEE Transactions on Automatic Control 1974, 19(6), 716-723. [CrossRef]

- Akaike, H. Information Theory and an Extension of the Maximum Likelihood Principle. In Selected Papers, Akaike. H.; Parzen, E.; Tanabe, K.; Kitagawa, G., Eds.; Springer Series in Statistics 1998, 199-213. [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, G. Estimating the Dimension of a Model. Annals of Statistics 1978, 6(2), 461-464. [CrossRef]

- Burnham, K.P.; Anderson, D.R. Model Selection and Inference: A Practical Information Theoretical Approach, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, USA, 2002; 512p. Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/b97636.

- Burnham, K.P.; Anderson, D.R. Multimodel Inference: Understanding AIC and BIC in Model Selection. Sociological Methods & Research 2004, 33(2), 261-304. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S.; Opper, M. Asymptotic Equivalence of Bayes Cross Validation and Widely Applicable Information Criterion in Singular Learning Theory. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2010, 11(12), 3571- 3594.

- Magnusson, M.; Andersen, M.R.; Jonasson, J.; Vehtari, A. Leave One Out Cross Validation for Bayesian Model Comparison in Large Data. In International conference on artificial intelligence and statistics 2020, 108, 341-351. Available online: https://proceedings.mlr.press/v108/magnusson20a.html.

- Craven, P.; Wahba, G. Smoothing noisy data with spline functions. Numerische Mathematik 1978, 31, 377-403. [CrossRef]

- Hastie T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J. The elements of statistical learning: data mining, inference, and prediction, 2009, 2. New York: Springer.

- Gueymard, C.A. A review of validation methodologies and statistical performance indicators for modeled solar radiation data: Towards better bankability of solar projects. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2014, 39, 1024-1034. [CrossRef]

- Marques Filho, E.P.; Oliveira, A.P.; Vita, W.A.; Mesquita, F.L.L.; Codato, G.; Escobedo, J.F.; Cassol, M.; França, J.R. Global, diffuse and direct solar radiation at the surface in the city of Rio de Janeiro: Observational characterization and empirical modeling. Renewable Energy 2016, 91, 64-74. [CrossRef]

- Elli, E.F.; Olivoto, T.; Schmidt, D.; Caron, B.O.; de Souza, V.Q. Precision of Growth Estimates and Sufficient Sample Size: Can Solar Radiation Level Change These Factors? Agronomy Journal 2018, 110, 155-163. [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, J.C.S.; Lopes, S.A.; Arenas, J.C.C.; da Silva, M.F.G. Flexible regression model for predicting the dissemination of Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus under variable climatic conditions. Infectious Disease Modelling 2025, 10, 60-74. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Ding, J. Information criteria for model selection. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews (WIREs) Computational Statistics 2023, 15, 1-27, e1607. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing 2025, Vienna, Austria. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed: 27 May 2025.

- Liu, F.; Wang, X.; Sun, F.; Wang, H. Correct and remap solar radiation and photovoltaic power in China based on machine learning models. Applied Energy 2022, 312, e118775. [CrossRef]

- Escobedo, J.F.; Gomes, E.N.; Oliveira, A.P.; Soares, J. Modeling hourly and daily fractions of UV, PAR and NIR to global solar radiation under various sky conditions at Botucatu, Brazil. Applied Energy 2009, 86(3), 299-309. [CrossRef]

- Weselek, A.; Ehmann, A.; Zikeli, S.; Lewandowski, I.; Schindele, S.; Högy, P. Agrophotovoltaic systems: applications, challenges, and opportunities. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 2019, 39, e35. [CrossRef]

- Wydra, K.; Vollmer, V.; Busch, C.; Prichta, S. Agrivoltaic: solar radiation for clean energy and sustainable agriculture with positive impact on nature. In: Aghaei, M.; Moazami, A. (Eds). Solar radiation – enabling technologies, recent innovations, and advancements for energy transition. Intechopen, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jain, S. Agrivoltaics: the synergy between solar panels and agricultural production. Darpan International Research Analysis 2024, 12(3), 137-149. [CrossRef]

- Giri, N.C.; Mohanty, R.C.; Shaw, R.N.; Poonia, S.; Bajaj, M.; Belkhier, Y. Agriphotovoltaic systems to improve land productivity and revenue of farmer. In: IEEE Global Conference on Computing, Power and Communications Technologies 2022, 1-5, . [CrossRef]

- Adeyanju, O.O.; Nabage, O.H.A.; Orimaye, O.S. Solar energy meteorology in agriculture – an X-ray of solar irradiance. International Journal of Current Science Research and Review 2022, 5(7), 2689-2697. [CrossRef]

- Yajima, D.; Toyoda, T.; Kirimura, M.; Araki, K.; Ota, Y.; Nishioka, K. Estimation model of agrivoltaic systems maximizing for both photovoltaic electricity generation and agricultural production. Energies 2023, 16(7), e3261. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Sarkar, A.; Mitra, A.; Das, A. Smart cropping based on predicted solar radiation using IoT and machine learning. In: IEEE International Conference on Advanced Trends in Multidisciplinary Research and Innovation 2020, 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Qian, H.; Goa, W.; Fukuda, H.; Zhou, W. Hourly global solar radiation prediction based on seasonal and stochastic feature. Heliyon 2023, 9(9), e19823. [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.; Yang, L.; Lv, T.; Liu, W.; Gao, X.; Zhou, J. Evaluation of machine learning models for predicting daily global and diffuse solar radiation under different weather/pollution conditions. Renewable Energy 2022, 187, 896-906. [CrossRef]

- Nematchoua, M.K.; Orosa, J.A.; Afaifia, M. Prediction of daily global solar radiation and air temperature using six machine learning algorithms; a case of 27 European countries. Ecological Informatics 2022, 69, e101643. [CrossRef]

| State | City or Station name | KCC* | Lat. | Lon. | Alt. | Operating period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acre | 1 - Rio Branco | Am | -9.67 | -68.16 | 163 | 2015-2022 |

| Amapá | 2 – Macapá | Am | 0.035 | -51.08 | 16 | 2013-2022 |

| Amazonas | 3 – Barcelos | Af | -0.98 | -62.92 | 29 | 2008-2022 |

| 4 – Eirunepé | Af | -6.65 | -69.87 | 121 | 2012-2022 | |

| 5 – Itacoatiara | Af | -3.12 | -58.47 | 41 | 2008-2022 | |

| 6 – Lábrea | Am | -7.25 | -64.78 | 61 | 2008-2018 | |

| 7 – Manaus | Af | -3.1 | -59.95 | 61 | 2000-2022 | |

| 8 – Parintins | Af | -2.63 | -56.75 | 18 | 2008-2018 | |

| 9 - São Gabriel da Cachoeira | Af | -0.12 | -67.05 | 79 | 2011-2022 | |

| Mato Grosso | 10 – Sinop | Aw | -11.97 | -55.55 | 366 | 2006-2017 |

| Pará | 11 - Belém | Af | -1.41 | -48.43 | 21 | 2003-2022 |

| 12 - Cametá | Af | -2.23 | -49.48 | 9 | 2008-2022 | |

| 13 - Conceição do Araguaia | Aw | -8.25 | -49.27 | 175 | 2008-2022 | |

| 14 - Itaituba | Af | -4.27 | -56.00 | 24 | 2008-2022 | |

| 15 - Marabá | Aw | -5.36 | -49.37 | 116 | 2009-2022 | |

| 16 - Monte Alegre | Am | -2.0 | -54.07 | 100 | 2012-2022 | |

| 17 - Óbidos | Am | -1.88 | -55.51 | 89 | 2012-2017 | |

| 18 - Soure | Am | -0.72 | -48.51 | 12 | 2008-2017 | |

| 19 - Tucuruí | Am | -3.82 | -49.67 | 137 | 2008-2017 | |

| Roraima | 20 - Boa Vista | Am | 2.82 | -60.68 | 82 | 2010-2022 |

| Nº | Meteorological variables | Nº | Meteorological variables |

| V1 | S, So, Ho | ||

| V2 | Tmax, So, Ho | V5 | Tmax, Tmin, So, Ho |

| V3 | Tmean, So, Ho | V6 | Tmean, Tmin, So, Ho |

| V4 | Tmax, Tmean, So, Ho | V7 | Tmax, Tmean, Tmin, So, Ho |

| V8 | RHmean, So, Ho | V10 | RHmax, RHmean, RHmin, So, Ho |

| V9 | RHmin, So, Ho | ||

| V11 | Tmax, RHmax, So, Ho | V18 | Tmin, RHmin, So, Ho |

| V12 | Tmax, RHmean, So, Ho | V19 | Tmax, Tmin, RHmax, RHmin, So, Ho |

| V13 | Tmax, RHmin, So, Ho | V20 | Tmax, Tmean, Tmin, RHmean, So, Ho |

| V14 | Tmean, RHmean, So, Ho | V21 | RHmax, RHmean, RHmin, Tmean, So, Ho |

| V15 | Tmean, RHmean, So, Ho | V22 | RHmax, RHmean, RHmin, Tmax, Tmin, So, Ho |

| V16 | Tmean, RHmin, So, Ho | V23 | Tmax, Tmean, Tmin, RHmax, RHmin, So, Ho |

| V17 | Tmin, RHmean, So, Ho | V24 | RHmax, RHmean, RHmin, Tmax, Tmean, Tmin, So, Ho |

| V25 | Tmax, S, So, Ho | V28 | Tmax, Tmin, S, So, Ho |

| V26 | Tmean, S, So, Ho | V29 | Tmax, Tmean, Tmin, S, So, Ho |

| V27 | Tmin, S, So, Ho | ||

| V30 | RHmax, S, So, Ho | V33 | RHmax, RHmin, S, So, Ho |

| V31 | RHmean, S, So, Ho | V34 | RHmax, RHmean, RHmin, S, So, Ho |

| V32 | RHmin, S, So, Ho | ||

| V35 | Tmax, Tmin, Rhmax, S, So, Ho | V38 | RHmax, RHmean, RHmin, Tmax, Tmin, S, So, Ho |

| V36 | Tmax, Tmin, Rhmin, S, So, Ho | V39 | RHmax, RHmin, Tmax, Tmean, Tmin, S, So, Ho |

| V37 | RHmax, RHmin, Tmax, Tmin, So, Ho | V40 | RHmax, RHmean, RHmin, Tmax, Tmean, Tmin, S, So, Ho |

| Station | Hg | Ho | S | Tmax | Tmean | Tmin | RHmax | RHmean | RHmin | Rainfall |

| 1 | 17.17±4.80 | 36.23±3.40 | 5.58±3.11 | 31.29±2.84 | 25.60±2.04 | 21.68±1.96 | 91.75±9.71 | 78.42±12.52 | 57.89±15.46 | 2954±139 |

| 2 | 19.86±5.28 | 36.12±1.35 | 6.95±3.23 | 31.76±1.65 | 27.54±1.22 | 23.97±0.73 | 92.67±2.44 | 76.56±1.22 | 55.95±9.10 | 2100±145 |

| 3 | 17.17±5.23 | 35.99±1.34 | 4.77±3.12 | 32.02±2.29 | 26.34±1.23 | 22.76±1.18 | 96.16±2.42 | 83.88±6.11 | 58.88±10.01 | 2443±72 |

| 4 | 15.64±4.25 | 36.36±2.55 | 3.94±2.70 | 31.55±2.27 | 25.92±1.48 | 22.24±1.39 | 86.59±14.76 | 70.16±14.29 | 45.52±16.55 | 1952±75 |

| 5 | 16.12±5.09 | 36.05±1.98 | 5.78±3.33 | 31.52±2.24 | 27.24±1.44 | 24.01±0.98 | 92.72±2.69 | 79.57±6.57 | 59.88±10.56 | 2339±104 |

| 6 | 17.15±3.84 | 35.76±2.95 | 5.24±3.30 | 32.75±2.10 | 26.70±1.30 | 22.57±1.51 | 94.28±1.43 | 78.86±5.96 | 51.90±10.34 | 2230±103 |

| 7 | 16.34±5.04 | 35.91±2.03 | 5.52±3.23 | 32.30±2.21 | 27.74±1.64 | 24.32±1.22 | 91.58±6.38 | 75.86±9.16 | 54.41±11.12 | 2206±99 |

| 8 | 17.52±5.41 | 35.88±1.84 | 6.17±3.41 | 31.29±2.07 | 27.15±1.43 | 24.24±1.09 | 92.66±3.67 | 81.09±6.72 | 62.05±9.19 | 2343±110 |

| 9 | 15.22±4.76 | 36.17±1.30 | 4.73±2.81 | 31.30±2.23 | 26.41±1.45 | 23.14±1.19 | 93.13±5.30 | 81.46±7.99 | 59.18±10.41 | 2867±46 |

| 10 | 19.13±4.19 | 35.95±3.96 | 6.03±3.04 | 32.35±2.81 | 25.41±1.63 | 20.16±2.11 | 91.69±8.05 | 72.04±15.78 | 44.38±16.82 | 1952±132 |

| 11 | 15.09±3.59 | 36.04±1.55 | 6.48±2.75 | 32.67±1.35 | 27.27±1.09 | 23.56±0.65 | 93.22±2.37 | 78.49±5.75 | 54.95±7.22 | 3205±129 |

| 12 | 20.16±3.78 | 35.91±1.79 | 7.57±2.59 | 32.47±1.21 | 27.75±1.13 | 24.23±1.02 | 88.92±4.04 | 74.36±6.15 | 53.30±6.81 | 2230±137 |

| 13 | 18.64±4.46 | 35.79±3.26 | 6.96±3.26 | 33.54±2.75 | 26.83±1.69 | 21.60±2.12 | 90.66±6.24 | 70.50±12.26 | 43.56±15.08 | 1686±104 |

| 14 | 18.75±4.71 | 36.03±2.25 | 6.24±3.18 | 32.67±2.17 | 27.58±1.46 | 23.85±0.96 | 86.22±10.94 | 74.87±7.16 | 60.38±12.95 | 2069±95 |

| 15 | 18.25±3.87 | 35.82±2.57 | 6.36±3.10 | 32.26±1.95 | 26.59±1.14 | 22.40±1.37 | 93.31±2.82 | 76.53±7.75 | 50.78±11.48 | 1885±123 |

| 16 | 20.61±4.19 | 36.13±1.71 | 7.53±2.79 | 31.66±1.69 | 27.54±1.29 | 23.97±1.05 | 87.92±5.38 | 75.30±6.98 | 55.21±8.88 | 1661±104 |

| 17 | 16.64±4.52 | 36.21±2.31 | 6.70±3.21 | 33.08±2.45 | 26.84±1.46 | 22.74±0.78 | 92.77±3.72 | 78.22±8.71 | 52.84±11.51 | 2572±107 |

| 18 | 19.82±4.30 | 35.96±1.38 | 6.89±3.55 | 30.94±0.95 | 27.71±1.04 | 25.34±1.51 | 86.30±6.78 | 76.98±6.03 | 64.05±5.21 | 2093±74 |

| 19 | 16.95±3.48 | 36.06±1.99 | 6.22±2.81 | 31.43±1.68 | 26.73±1.15 | 23.36±0.94 | 94.25±4.29 | 78.42±7.70 | 56.01±9.19 | 2400±157 |

| 20 | 19.35±4.35 | 35.99±1.77 | 6.49±2.87 | 33.51±2.22 | 27.83±1.56 | 23.70±1.07 | 86.69±7.71 | 68.54±10.17 | 45.03±10.41 | 1616±100 |

| Input variable | Weather station | Estimation model | ||

| EM model | SVM - V1 | MLP - V1 | ||

| Insolation | Boa Vista | - 0.054 ± 1.771 | -0.139 ± 1.664 | -0.051 ± 1.712 |

| Manaus | -0.079 ± 2.253 | -0.245 ± 2.246 | -0.122 ± 2.254 | |

| Sinop | -0.079 ± 2.253 | -0.245 ± 2.246 | -0.122 ± 2.254 | |

| FAN model | SVM - V7 | MLP - V7 | ||

| Air temperature | Boa Vista | -0.070 ± 2.281 | -0.238 ± 2.216 | -0.071 ± 2.380 |

| Manaus | -0.134 ± 3.170 | -0.122 ± 3.080 | -0.001 ± 3.112 | |

| Sinop | -0.323 ± 5.464 | -0.089 ± 2.767 | -0.048 ± 3.018 | |

| CHEN model | SVM - V28 | MLP - V28 | ||

| Hybrid combination | Boa Vista | -0.039 ± 1.720 | -0.119 ± 1.412 | -0.053 ± 1.440 |

| Manaus | -0.083 ± 2.186 | -0.289 ± 2.008 | -0.095 ± 2.046 | |

| Sinop | -0.549 ± 5.655 | 0.038 ± 2.097 | -0.076 ± 2.268 | |

| Station | Criteria | Models | Best model | Model ranking | |||

| Insolação | EM model | SVM 1 | MLP 1 | ||||

| Boa Vista | LL | -1435.480 | -1378.457 | -1402.883 | SVM 1 |

SVM 1 – 1º MLP 1 – 2º EM model – 3º |

|

| AIC | 2876.959 | 2764.914 | 2813.766 | SVM 1 | |||

| BIC | 2891.569 | 2784.394 | 2833.246 | SVM 1 | |||

| BICc | 2884.699 | 2777.524 | 2826.376 | SVM 1 | |||

| WAICa | 2878.959 | 2766.914 | 2815.766 | SVM 1 | |||

| GVC | 3038.945 | 2705.242 | 2845.960 | SVM1 | |||

| Manaus | LL | -3345.215 | -3349.631 | -3347.904 | EM model | EM model – 1º SVM 1 – 2º MLP 1 – 3º |

|

| AIC | 6696.430 | 6707.262 | 6703.808 | EM model | |||

| BIC | 6713.129 | 6729.527 | 6726.073 | EM model | |||

| BICc | 6705.563 | 6721.960 | 6718.507 | EM model | |||

| WAICa | 6698.430 | 6709.262 | 6705.808 | EM model | |||

| GVC | 9840.502 | 9896.006 | 9878.173 | EM model | |||

| Sinop | LL | -1651.183 | -1157.826 | -1164.173 | SVM 1 | SVM 1 – 1º MLP 1 – 2º Modelo 10 – 3º |

|

| AIC | 3308.366 | 2323.653 | 2336.346 | SVM 1 | |||

| BIC | 3321.670 | 2341.391 | 2354.084 | SVM 1 | |||

| BICc | 3315.235 | 2334.957 | 2347.650 | SVM 1 | |||

| WAICa | 3310.366 | 2325.653 | 2338.346 | SVM 1 | |||

| GVC | 20058.800 | 4129.290 | 4214.117 | SVM 1 | |||

| Air temperature | FAN model | SVM 7 | MLP 7 | ||||

| Boa Vista | LL | -1679.145 | -1656.547 | -1719.998 | SVM 7 | SVM 7 – 1º FAN model – 2º MLP 7 – 3º |

|

| AIC | 3368.290 | 3325.094 | 3451.997 | SVM 7 | |||

| BIC | 3392.640 | 3354.314 | 3481.217 | SVM 7 | |||

| BICc | 3385.770 | 3347.444 | 3474.347 | SVM 7 | |||

| WAICa | 3370.290 | 3327.094 | 3453.997 | SVM 7 | |||

| GVC | 5061.517 | 4839.849 | 5521.364 | SVM 7 | |||

| Manaus | LL | -4005.870 | -3950.230 | -3968.264 | SVM 7 | SVM 7 - 1º MLP 7 – 2º FAN model – 3º |

|

| AIC | 8021.740 | 7912.461 | 7948.527 | SVM 7 | |||

| BIC | 8049.572 | 7945.859 | 7981.925 | SVM 7 | |||

| BICc | 8042.006 | 7938.292 | 7974.359 | SVM 7 | |||

| WAICa | 8023.740 | 7914.461 | 7950.527 | SVM 7 | |||

| GVC | 19540.50 | 18465.86 | 18813.70 | SVM 7 | |||

| Sinop | LL | -1631.320 | -1206.492 | -1260.310 | SVM 7 | SVM 7 - 1º MLP 7 – 2º FAN model – 3º |

|

| AIC | 3272.639 | 2424.984 | 2532.620 | SVM 7 | |||

| BIC | 3294.812 | 2451.591 | 2559.228 | SVM 7 | |||

| BICc | 3288.378 | 2445.156 | 2552.793 | SVM 7 | |||

| WAICa | 3274.639 | 2426.984 | 2534.620 | SVM 7 | |||

| GVC | 18942.280 | 4859.383 | 5775.792 | SVM 7 | |||

| Hybrid combination (S x Tair) |

CHEN model | SVM 28 | MLP 28 | ||||

| Boa Vista | LL | -1407.025 | -1220.253 | -1236.760 | SVM 28 | SVM 28 – 1º MLP 28 – 2º CHEN model – 3º |

|

| AIC | 2822.051 | 2452.507 | 2485.520 | SVM 28 | |||

| BIC | 2841.531 | 2481.727 | 2514.740 | SVM 28 | |||

| BICc | 2834.661 | 2474.857 | 2507.870 | SVM 28 | |||

| WAICa | 2824.051 | 2454.507 | 2487.520 | SVM 28 | |||

| GVC | 2870.375 | 1955.652 | 2023.937 | SVM 28 | |||

| Manaus | LL | -3286.880 | -3141.678 | -3160.244 | SVM 28 | SVM 28 - 1º MLP 28 – 2º CHEN model – 3º |

|

| AIC | 6581.760 | 6295.356 | 6332.488 | SVM 28 | |||

| BIC | 6604.025 | 6328.754 | 6365.886 | SVM 28 | |||

| BICc | 6596.459 | 6321.187 | 6358.319 | SVM 28 | |||

| WAICa | 6583.760 | 6297.356 | 6334.488 | SVM 28 | |||

| GVC | 9273.421 | 7996.097 | 8150.956 | SVM 28 | |||

| Sinop | LL | -1654.476 | -1033.619 | -1082.725 | SVM 28 | SVM 28- 1º MLP 28 – 2º CHEN model – 3º |

|

| AIC | 3316.953 | 2079.238 | 2177.449 | SVM 28 | |||

| BIC | 3334.691 | 2105.845 | 2204.057 | SVM 28 | |||

| BICc | 3328.256 | 2099.410 | 2197.622 | SVM 28 | |||

| WAICa | 3318.953 | 2081.238 | 2179.449 | SVM 28 | |||

| GVC | 20337.850 | 2789.800 | 3265.582 | SVM 28 | |||

| Stations | Selected models/Ranking | 1º | 2º | 3º |

| Boa Vista | Insolation | SVM 1 | MLP 1 | EM model |

| Air temperature | SVM 7 | FAN model | MLP 7 | |

| Hybrid combination | SVM 28 | MLP 28 | CHEN model | |

| Prevailing model | SVM | MLP | Model | |

| Manaus | Insolation | EM model | SVM 1 | MLP 1 |

| Air temperature | SVM 7 | MLP 7 | FAN model | |

| Hybrid combination | SVM 28 | MLP 28 | CHEN model | |

| Prevailing model | SVM | MLP | Model | |

| Sinop | Insolation | SVM 1 | MLP 1 | EM model |

| Air temperature | SVM 7 | MLP 7 | FAN model | |

| Hybrid combination | SVM 28 | MLP 28 | CHEN model | |

| Prevailing model | SVM | MLP | Model |

| Stations | Criteria | SVM 1 | SVM 7 | SVM 28 | Best Model | Ranking models |

| Boa Vista | LL | -1378.457 | -1656.547 | -1220.253 | SVM 28 | SVM 28 – 1º SVM 1 – 2º SVM 7 – 3º |

| AIC | 2764.914 | 3325.094 | 2452.507 | SVM 28 | ||

| BIC | 2784.394 | 3354.314 | 2481.727 | SVM 28 | ||

| BICc | 2777.524 | 3347.444 | 2474.857 | SVM 28 | ||

| WAICa | 2766.914 | 3327.094 | 2454.507 | SVM 28 | ||

| GVC | 2705.242 | 4839.849 | 1955.652 | SVM 28 | ||

| Manaus | LL | -3349.631 | -3950.230 | -3141.678 | SVM 28 | SVM 28 – 1º SVM 1 – 2º SVM 7 – 3º |

| AIC | 6707.262 | 7912.461 | 6295.356 | SVM 28 | ||

| BIC | 6729.527 | 7945.859 | 6328.754 | SVM 28 | ||

| BICc | 6721.960 | 7938.292 | 6321.187 | SVM 28 | ||

| WAICa | 6709.262 | 7914.461 | 6297.356 | SVM 28 | ||

| GVC | 9896.006 | 18465.86 | 7996.097 | SVM 28 | ||

| Sinop | LL | -1157.826 | -1206.492 | -1033.619 | SVM 28 | SVM 28 – 1º SVM 1 – 2º SVM 7 – 3º |

| AIC | 2323.653 | 2424.984 | 2079.238 | SVM 28 | ||

| BIC | 2341.391 | 2451.591 | 2105.845 | SVM 28 | ||

| BICc | 2334.957 | 2445.156 | 2099.410 | SVM 28 | ||

| WAICa | 2325.653 | 2426.984 | 2081.238 | SVM 28 | ||

| GVC | 4129.290 | 4859.383 | 2789.800 | SVM 28 |

| Stations | Criterias | MLP 1 | MLP 7 | MLP 28 | Best model | Rankin model |

| Boa Vista | LL | -1402.883 | -1719.998 | -1236.760 | MLP 28 | MLP 28 – 1º MLP 1 – 2º MLP 7 – 3º |

| AIC | 2813.766 | 3451.997 | 2485.520 | MLP 28 | ||

| BIC | 2833.246 | 3481.217 | 2514.740 | MLP 28 | ||

| BICc | 2826.376 | 3474.347 | 2507.870 | MLP 28 | ||

| WAICa | 2815.766 | 3453.997 | 2487.520 | MLP 28 | ||

| GVC | 2845.960 | 5521.364 | 2023.937 | MLP 28 | ||

| Manaus | LL | -3347.904 | -3968.264 | -3160.244 | MLP 28 | MLP 28 – 1º MLP 1 – 2º MLP 7 – 3º |

| AIC | 6703.808 | 7948.527 | 6332.488 | MLP 28 | ||

| BIC | 6726.073 | 7981.925 | 6365.886 | MLP 28 | ||

| BICc | 6718.507 | 7974.359 | 6358.319 | MLP 28 | ||

| WAICa | 6705.808 | 7950.527 | 6334.488 | MLP 28 | ||

| GVC | 9878.173 | 18813.70 | 8150.956 | MLP 28 | ||

| Sinop | LL | -1164.173 | -1260.310 | -1082.725 | MLP 28 | MLP 28 – 1º MLP 1 – 2º MLP 7 – 3º |

| AIC | 2336.346 | 2532.620 | 2177.449 | MLP 28 | ||

| BIC | 2354.084 | 2559.228 | 2204.057 | MLP 28 | ||

| BICc | 2347.650 | 2552.793 | 2197.622 | MLP 28 | ||

| WAICa | 2338.346 | 2534.620 | 2179.449 | MLP 28 | ||

| GVC | 4214.117 | 5775.792 | 3265.582 | MLP 28 |

| Station | Criteria | EM model | FAN model | CHEN model | Best model | Ranking model |

| Boa Vista | LL | -1435.480 | -1679.145 | -1407.025 | CHEN model | CHEN model – 1º EM model – 2º FAN model – 3º |

| AIC | 2876.959 | 3368.290 | 2822.051 | CHEN model | ||

| BIC | 2891.569 | 3392.640 | 2841.531 | CHEN model | ||

| BICc | 2884.699 | 3385.770 | 2834.661 | CHEN model | ||

| WAICa | 2878.959 | 3370.290 | 2824.051 | CHEN model | ||

| GVC | 3038.945 | 5061.517 | 2870.375 | CHEN model | ||

| Manaus | LL | -3345.215 | -4005.870 | -3286.880 | CHEN model | CHEN model – 1º EM model – 2º FAN model – 3º |

| AIC | 6696.430 | 8021.740 | 6581.760 | CHEN model | ||

| BIC | 6713.129 | 8049.572 | 6604.025 | CHEN model | ||

| BICc | 6705.563 | 8042.006 | 6596.459 | CHEN model | ||

| WAICa | 6698.430 | 8023.740 | 6583.760 | CHEN model | ||

| GVC | 9840.502 | 19540.50 | 9273.421 | CHEN model | ||

| Sinop | LL | -1651.183 | -1631.320 | -1654.476 | FAN model | FAN model – 1º EM model – 2º CHEN model– 3º |

| AIC | 3308.366 | 3272.639 | 3316.953 | FAN model | ||

| BIC | 3321.670 | 3294.812 | 3334.691 | FAN model | ||

| BICc | 3315.235 | 3288.378 | 3328.256 | CHEN model | ||

| WAICa | 3310.366 | 3274.639 | 3318.953 | CHEN model | ||

| GVC | 20058.800 | 18942.280 | 20337.850 | CHEN model |

| Best Model Settings | Order of Models |

| 1º: Hybrid models | SVM -V28 – 1º; MLP -V28 – 2º; CHEN model – 3º |

| 2º: Models based on insolation | SVM - V1– 1º; MLP - V1 – 2º; EM model – 3º |

| 3º: Models based on air temperature | SVM - V7 – 1º; MLP - V7 – 2º; FAN model – 3º |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).