1. Introduction

Near Surface Air Temperature (hereafter NSAT) is one of the most important meteorological parameters for forecasters and researchers. Its impact in every-day life and all kinds of socioeconomic activities cannot be overestimated. So, it is essential to have accurate and on-time readings of near surface air temperature at a high spatial resolution. Weather stations can provide such readings with a high level of accuracy, however the dense spatial coverage of the Earth’s surface is in many cases difficult due to a variety of reasons. For example, extreme topography could pose problems in the installation and correct operation of weather stations. In less developed countries of the planet, lack of funding often leads to significant deficiencies in coverage.

Environmental satellites can offer information on the Earth’s surface and atmosphere. The plethora of available data has different characteristics, strong points and deficiencies. Satellites in geostationary orbits, like the European Meteosat series, present the advantage of continuous observation of their field of view. Their scanning frequency varies but in general it is in the order of minutes. Meteosat Second Generation (MSG), operated by EUMETSAT (European Organisation for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites) is the primary meteorological geostationary satellite of Europe from 2004 to 2024. It scans its field of view every 15 minutes with a maximum horizontal resolution of 3 km in the infrared and 1 km in the visible spectrum (at nadir subsatellite point).

During the last decades, substantial efforts were made in the subject of estimation of air temperature close to the earth surface using satellite data as primary input. For example, Stisen et al. [

1] estimated the diurnal variation of air temperature in parts of Africa using Spinning Enhanced Visible and Infrared Imager (SEVIRI – onboard MSG satellites) data split windows techniques and the Temperature Deviation Index Method TVX [

2]. Amongst other limitations of their approach, a cloud free fraction of 90% within the window was necessary. The diurnal variation of air temperature was based on an interpolation scheme using the time of day as independent variable. A precision of about 3 °C and bias of -1.1 °C was achieved. The parameterization of air temperature through the combined use of SEVIRI and MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) instruments was attempted by Zakšek and Schroedter-Homscheidt [

3]. After a statistical downscaling of the SEVIRI data to one kilometer resolution, 2-m air temperature over parts of Central Europe was estimated from land surface temperature with an empirical parameterization, employing down-welling surface short-wave flux, relief characteristics and NDVI. LSA SAF and NWC SAF (Support to Nowcasting and Very Short Range Forecasting) data were used as satellite input except NDVI which was derived from MODIS measurements. Their analysis resulted in a RMSD of 2.00 °C, a bias of 0.01 °C and a correlation coefficient of 0.95. Only cloud-free pixels were considered.

The TVX empirical algorithm for air temperature estimation was calibrated and validated over the Iberian Peninsula by Nieto et al. [

4]. They used SEVIRI data and they applied the TVX algorithm only if 2/3 of the pixels were classified as non-cloudy. Their results showed a MAE of 2.8 °C, a RMSE of 3.7 °C and an overestimation of 1.0 °C when analyzing the hourly dataset. The daily maximum air temperature was adequately approximated with a RMSE of 5 °C. Shen and Leptoukh [

5] estimated the surface air temperature over central and eastern Eurasia from MODIS land surface temperature using a linear regression method. Only clear sky days were considered for the computation of the MODIS surface temperature. It was argued that the relationships between the maximum T

a and daytime T

s depend significantly on the land cover, but the relationships between the minimum T

a and nighttime T

s was weakly dependent on the land cover. Therefore, different linear regression equations of maximum T

a estimation were calculated for the several land cover groups while for the minimum T

a no distinction between land cover was made. The mean absolute error of the maximum T

a was found to range between 2.4 °C and 3.2 °C while for the minimum T

a MAE was about 3.0 °C. Hengl et al. [

6] using MODIS LST, topographical, time and insolation data employed principal component analysis formulated models of estimation of daily air temperature maps over Croatia. They achieved an average accuracy of ±2.4 °C. Parmentier et al. [

7] assessed a collection of methods and remote-sensing derived covariates for regional predictions of 1 km daily maximum air temperature. Mean elevation, MODIS LST, and distance to ocean were amongst the most frequently significant covariates besides latitude and longitude that were included by default in the models. Using the top set of covariates it was found that MAE ranged from 1.93 °C to 2.02 °C between the 3 interpolation methods while the ME was negative and did not exceed -0.11 °C. Stepwise regression analysis was employed by Janatian et al. [

8] in order to simulate average air temperature at daily and weekly scales over Iran. A series of predictors, including MODIS LST were examined for their importance in the formulation of temperature. The proposed model estimates average T

air with a mean absolute error of 2.3 °C and 1.8 °C at daily and weekly scales, respectively. Only cloud-free pixels were considered. Hooker et al. [

9] constructed a global dataset of air temperature at 0.05 ° horizontal resolution using MODIS LST monthly data and a statistical model that incorporates information on geographic and climatic similarity. The RMSE ranged from 1.14 °C to 1.55 °C. Historical minimum, maximum and average air temperature models at 1 km and 200 m resolution over France were constructed by Hough et al. [

10] using linear mixed models with MODIS and Landsat data in combination with spatial predictors. According to their validation, MAE ranged from 0.9 °C to 1.4 °C for the 1 km dataset. Nascetti et al. [

11] employed a Neural Network regression model to estimate the maximum air temperature in Puglia, Italy, using NDVI and LST Landsat-8 data. Pixels with cloud cover over 50% were excluded. They managed to reach an R

2 of 0.8, suggesting a quite successful fit.

Overall, most of these methods manage to calculate the desired temperature parameter (instantaneous, daily, mean, maximum, minimum, monthly mean etc) with an acceptable degree of accuracy. However, all these methods operate under non-cloudy conditions while most of them are not adequate for continuous real-time estimation of the air temperature. The use of a semi-predefined daily curve of air temperature is another shortcoming in some of those methodologies, as it limits the margin for strong short-term temperature variations during e.g. short periods of cloudiness or rain. Finally, some of these methods use relationships that are strongly dependent on region and therefore they are not suitable for use in other areas.

In this paper we present our research on the subject of continuous, near-real time estimation of NSAT under both cloudy and non-cloudy conditions. LSA SAF products and static topographic parameters are required for the estimation of NSAT. One of the main novel features of our approach is the ability to estimate NSAT under both cloudy and non-cloudy conditions, something that is accomplished for the first time, according to the authors’ knowledge. As stated earlier, there were several attempts to estimate air temperature with very good results however all of them were limited during non-cloudy periods. Such an innate deficiency renders them non-applicable during cloudy conditions which are obviously frequent during adverse weather. Our method overcomes the problem and performs under all kinds of weather. A second, quite important novel element is the ability of easy and fast near-real time estimation of NSAT, provided that the necessary data are available in near real-time.

NSAT can be used in nowcasting operations as an extra source of information and by authorities and policy makers in adapting quickly and facing challenges related to extreme heat or frost. Provided that the necessary LSA SAF data are available, the NSAT could be applied to create archives of NSAT datasets. Such archives could be employed in research studies that require reliable near surface air temperature data in areas where weather stations coverage is poor, or in cases where a homogenous dataset is required.

Finally, as most of the input data are derived from geostationary satellites products and freely accessible topography parameters, our method can easily offer continuous temperature information over regions where weather stations are sparse or absent. Such a strong potential for operational application makes our method a valuable source of weather data for every-day operational activities.

2. Data and Methodology

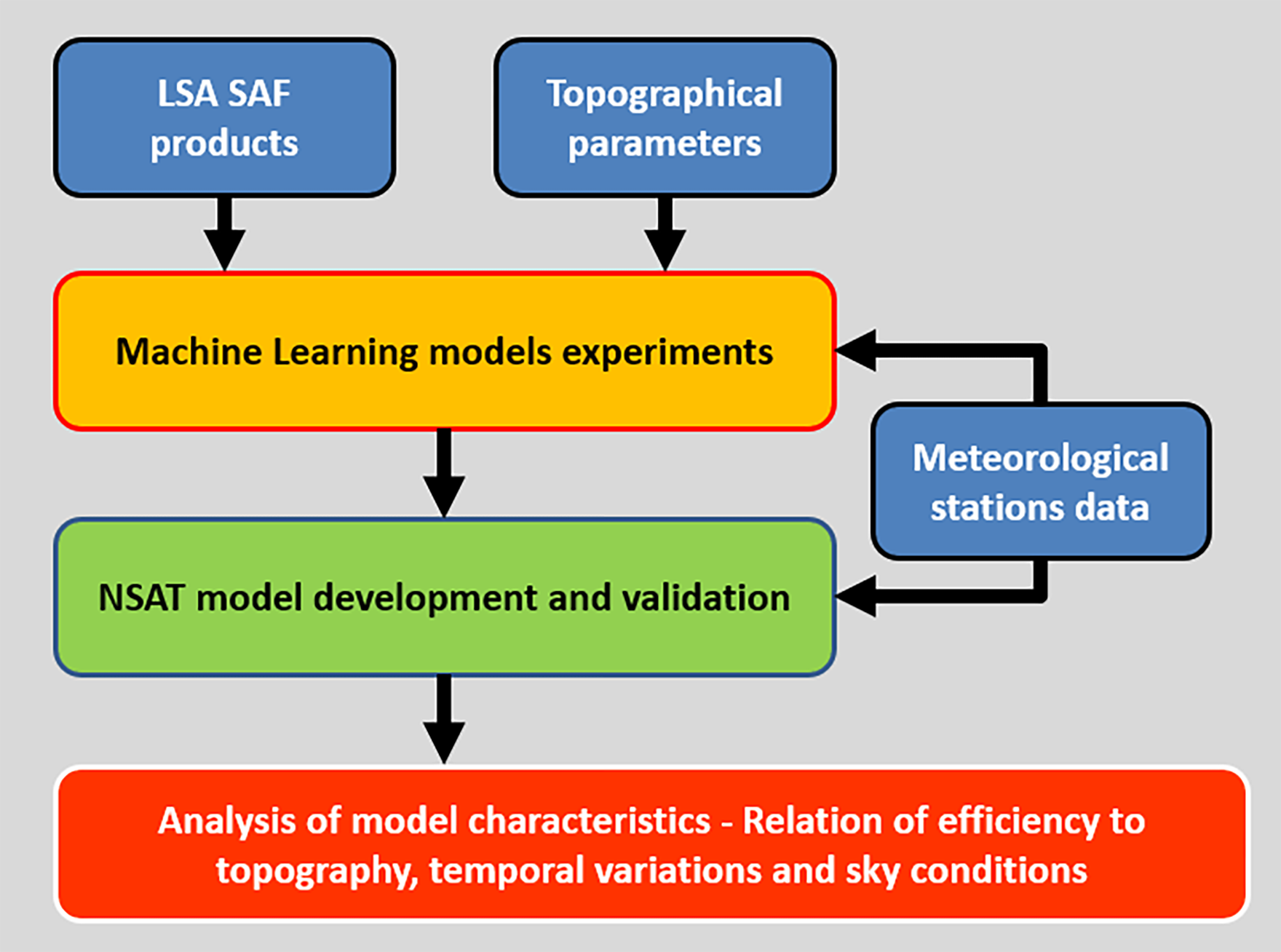

Three primary sources of data are utilized in the present analysis. Static topographic parameters and LSA SAF products are employed as predictors of the near surface air temperature while temperature data, derived from the network of surface weather stations operated by the METEO Unit at the National Observatory of Athens (METEO/NOA) will act as ground truth for the training and validation of the models. Their draft description follows.

2.1. Data

2.1.1. LSA SAF Satellite Derived Data

As stated in EUMETSAT’s website [

12], Satellite Application Facilities (SAFs) are dedicated centers of excellence for processing satellite data. EUMETSAT Secretariat supervises and coordinates the activities of the SAF network, ensuring that the SAFs in operations are providing reliable and timely operational services related to the meteorological and environmental issues. LSA SAF [

13] uses satellite observations to create a series of products focused on agriculture, forestry, land use planning and disaster management.

Archived LSA SAF products for the 2-year period from July 2020 to June 2022 were used for the training and validation of our models. Each of them is available in the MSG projection with an approximate horizontal resolution of 5 Km (over Greece). These parameters, along with their maximum temporal resolution and their abbreviations are presented in

Table 1. The sub-daily parameters are used at a 30 min temporal resolution while for the 4 daily parameters their daily value is assigned to all 30 min values of the respective day. Total (TOT), diffuse (DIF) and Direct (DIR) parts were extracted and analyzed from the Total and Diffuse Downward Surface Shortwave Flux (SSF) product. Broadband Shortwave Bi-Hemispherical (BB-BH), Shortwave Directional-Hemispherical (BB-DH), Near Infrared Directional-Hemispherical (NI-DH) and Visible Directional-Hemispherical (VI-DH) were extracted and analyzed from the MDAL product. 30 min differences were also computed and analyzed for the SSF, LF, LE, H and ET parameters (full names of Land SAF products are given in

Table 1). It should be noted here that the radiation and heat fluxes and the evapotranspiration parameters refer to the ground surface and therefore are considered relevant to the formulation of NSAT. Finally, the great advantage of the LSA SAF products used here is that they are computed for both cloudy and non-cloudy conditions. More about these products can be found in the LSA SAF website [

13].

To account for the period (noon, midnight, sunrise etc) of the day and more specifically the sun illumination conditions, the Sun Zenith Angle (SZA) of each pixel scan was also included in the analysis. SZA is a better indicator of the period of the day as it is irrelevant of time zone and the distance of a site to the prime meridian. These data were kindly provided by LSA SAF after request.

2.1.2. Static Topographic Parameters

Static topographic data computed from the Geodata.gov.gr shapefiles [

14], the Copernicus eu-dem-v1.1-25m, downloaded from the Copernicus website [

15] and finally location information of the weather stations are used for the training and validation of the models (more information follows later in the section).

Table 2 presents these parameters, along with their source, units and a very brief description.

2.1.3. Weather Stations Observed Temperatures

Finally, temperature data were extracted from the archive of the METEO/NOA weather stations network data archive [

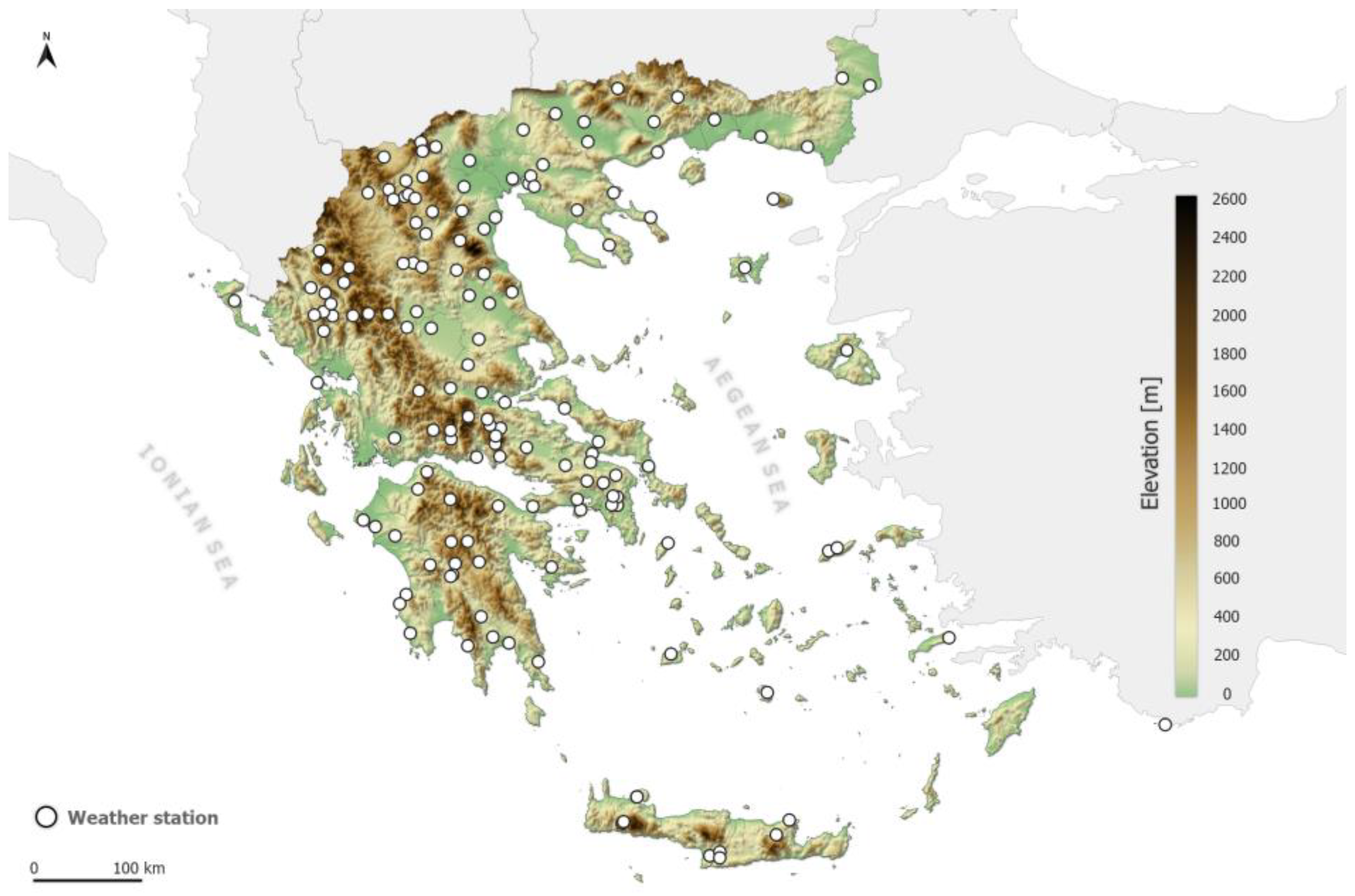

16]. 126 stations distributed over the Greek mainland and islands were used. Temperature is archived every 10 minutes. The offset between the nominal time of the scan of MSG and the actual scan time of the Greek area approaches 10 minutes. Following that, the HH:00 and HH:30 images actually scan the Greek area around HH:10 and HH:40 respectively. Therefore, the HH:10 and HH:40 temperature records were selected as corresponding ground truth.

Figure 1 shows the stations locations overlaid on the topography of the area.

2.2. Methodology

Three machine learning methods were employed to create NSAT estimation models: Random Forest (RF), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs). The models were trained using the Keras and scikit-learn libraries of the Python scripting language. The trained models were exported and saved so that they can be used to generate NSAT estimates/predictions straightforwardly when provided with the necessary static and dynamic parameters on which they were originally trained.

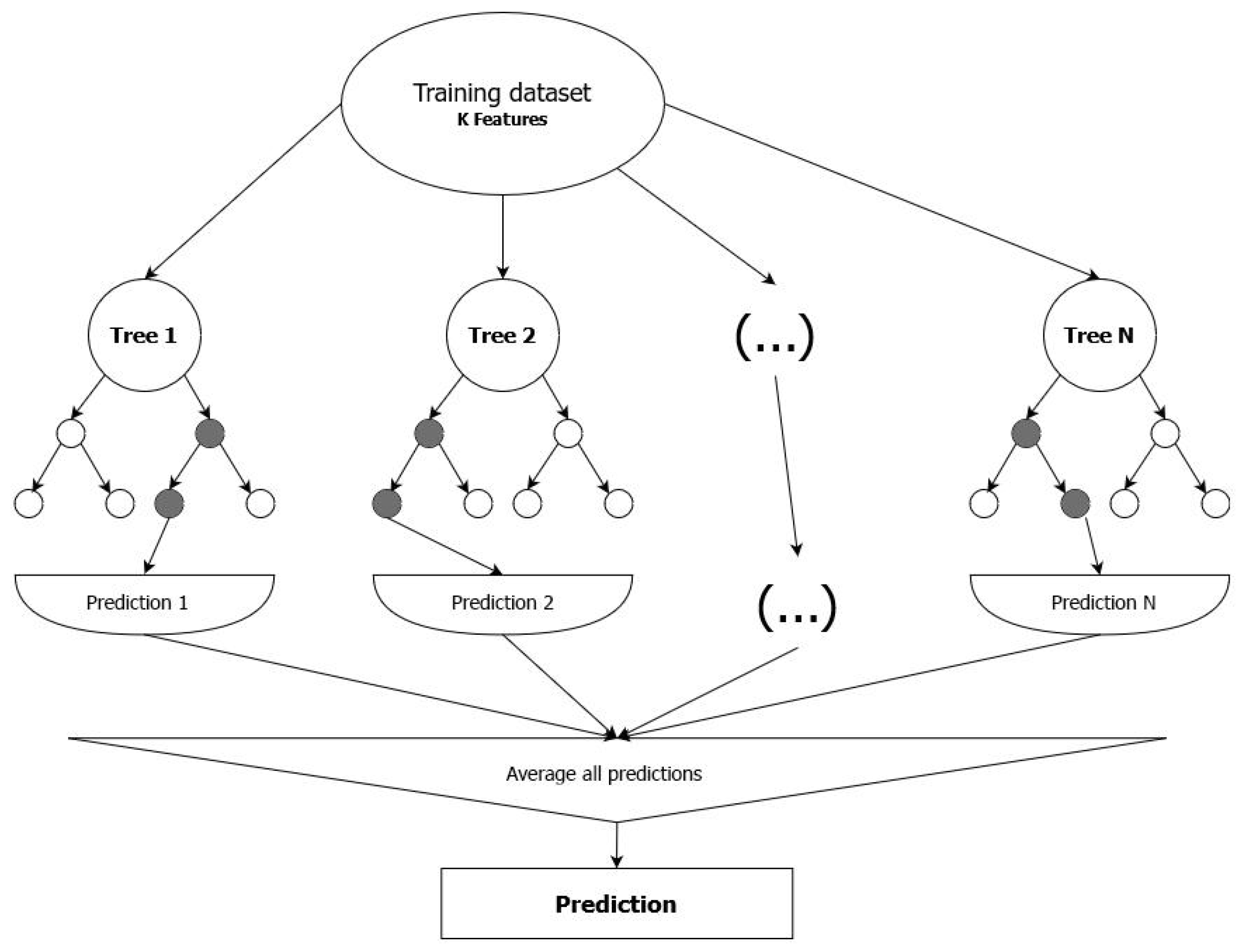

2.2.1. Random Forest

Random Forest is a supervised machine learning ensemble algorithm based on decision tree predictors [

17]. It can be applied to both classification and regression tasks. For analyzing large weather related datasets, the Random Forest algorithm is particularly well-suited [

18]. Due to its high prediction accuracy, this algorithm is widely used and provides insights into the importance of variables in both classification and regression. The primary parameter to tune is the number of trees [

19]. A conceptual schematic of RF is illustrated in

Figure 2. In Random Forest, all trees operate independently, with no interaction among them. The model works by constructing multiple decision trees during the training phase and producing a prediction by averaging the outputs of these trees for regression tasks or using a majority vote for classification tasks. In our work, we utilized the Random Forest Regressor with the following settings:

n_estimators: 60;

min_samples_split: 2;

min_samples_leaf: 2;

random_state: 42.

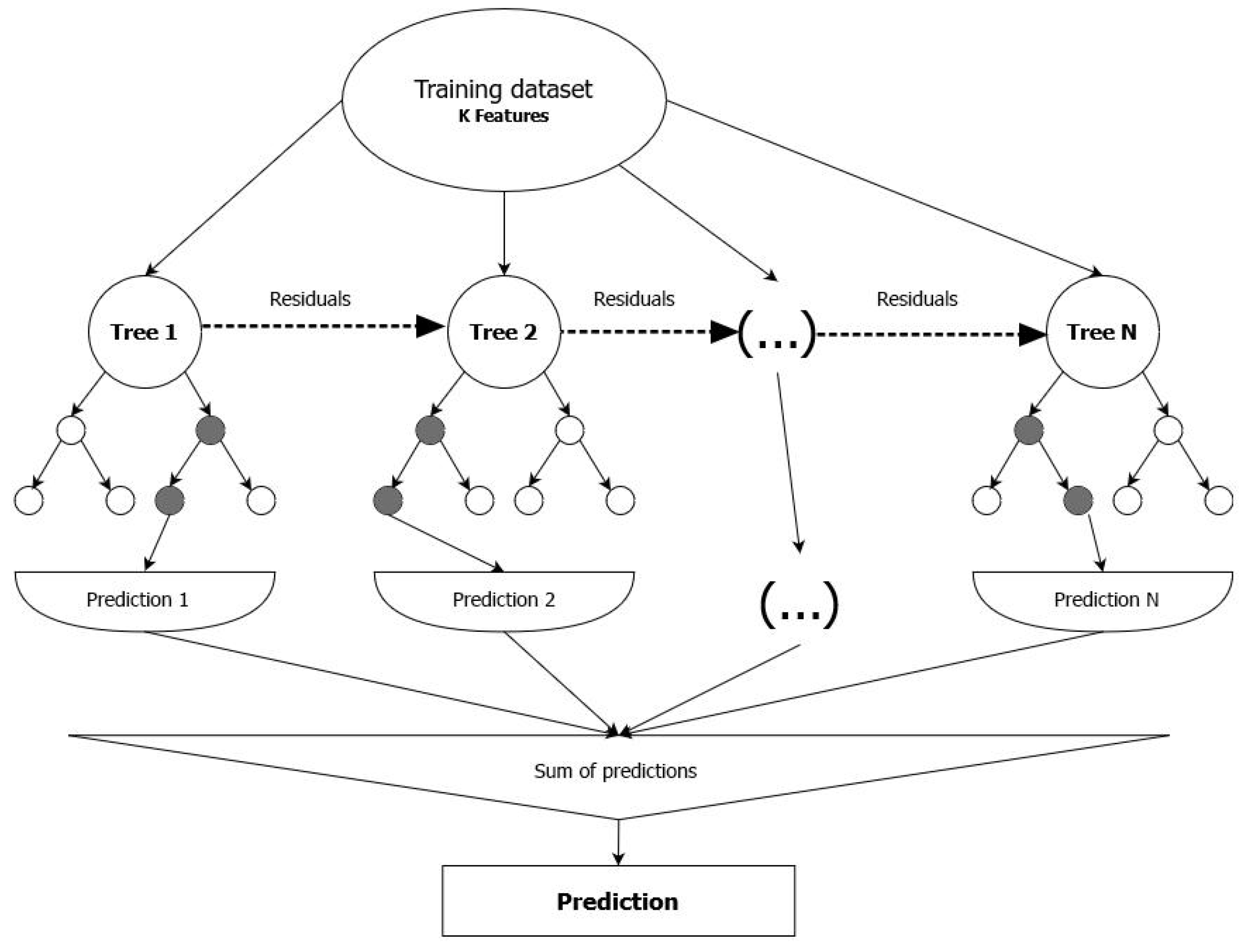

2.2.2. Extreme Gradient Boosting

XGBoost is a scalable machine learning system for tree boosting. It is a specific implementation of the Gradient Boosting method that uses more accurate approximations to find the optimal tree model. The key difference compared to Random Forest is that the models are trained sequentially: each model makes a prediction, and the residual errors from that prediction are used to train the next model. The final prediction is obtained by combining the outputs of all models. XGBoost can be applied to both regression and classification tasks and is preferred by data scientists due to its high execution speed and out-of-core computation capabilities [

20,

21]. A conceptual schematic of XGBoost is illustrated in

Figure 3. XGBoost optimizes a regularized objective function that combines a convex loss function (reflecting the difference between predicted and target outputs) with a penalty term to control model complexity, specifically for the regression tree functions. Training is performed iteratively by adding new trees that predict the residuals (errors) of previous trees, which are then combined with earlier trees to refine the predictions. The term 'gradient boosting' refers to the use of a gradient descent algorithm to minimize the loss function as new models are added. In our work, we utilized the XGBoost Regressor with the following settings:

n_estimators: 500;

max_depth: 5;

learning_rate: 0.1;

random_state: 42.

2.2.3. Artificial Neural Networks (ANN)

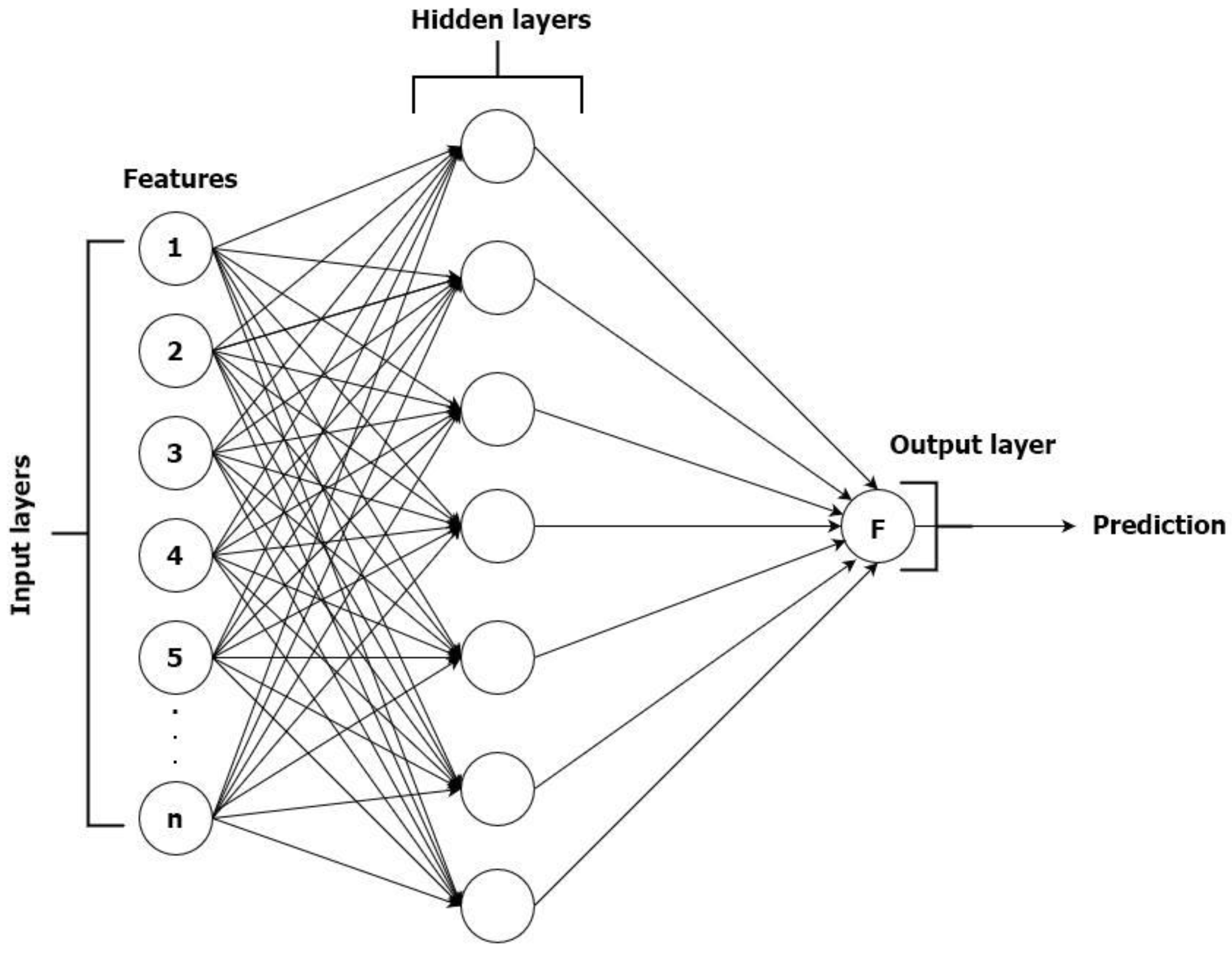

Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) are a class of artificial intelligence that mimic the biological structure of the human brain. In our work, we use and describe one of the commonly used types of ANNs, such as Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) [

22].

The Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) is a feed-forward Artificial Neural Network (ANN) that has been widely used for air temperature prediction [

23,

24] and other meteorological parameters. An MLP consists of an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer. The basic processing elements of the MLP are interconnected neurons, or nodes, which are connected by adaptable weights. Each neuron receives input signals from the outputs of other neurons. The output of a neuron is determined by a function of the weighted inputs, bias, and an activation function [

25].

Where

is an output from the neuron,

is the ith input to the neuron,

is the connection weight of the ith input,

is the bias, and

is the activation function. The conceptual schematic of Simple Multilayer Perceptron Neural Network is illustrated in

Figure 4. In our work, we implemented a deep feedforward neural network tailored for regression tasks. The architecture features six hidden layers with progressively decreasing neuron counts (ranging from 1000 to 50), each using ReLU activation to effectively capture complex data patterns. The output layer consists of a single neuron with a linear activation function, ideal for continuous value prediction. The model is optimized with the Adam algorithm and utilizes Mean Squared Error (MSE) as the loss function, while Mean Absolute Error (MAE) is tracked as an evaluation metric. To prevent overfitting, early stopping is employed, terminating training if the validation loss does not improve for 50 consecutive epochs. The model is trained for up to 15 epochs with a batch size of 50, leveraging validation data to monitor performance throughout training.

The dataset was divided in two parts; the training subset and the validation subset. The first one was used for the training of the models while the second one was used for the efficiency testing of the developed models. The validation subset consists of 20% of the total predictors/ground truth pairs. One every 5 consecutive (in terms of time) pairs was set aside for the validation procedures, in order to avoid any physical cycles making thus the validation subset independent of any daily, monthly or annual cycles.

A series of frequently used error metrics were computed to assess the degree of efficiency of each model.

Root Mean Square Error:

where

is the estimation of the algorithms,

is the temperature observations, N is the total number of estimation–observation pairs, and

is the average value of the observations. More information about the statistics used can be found in the WWRP/WGNE Joint Working Group on Forecast Verification Research webpage [

26].

The coefficient of determination

, which expresses the proportion of the variation in the dependent variable that is predictable from the independent variables, was computed and examined. The best possible score is 1.0 while it could also acquire negative values. The negative values occur when the model fits the data worse than the worst possible least-squares predictor. A constant model that always predicts the average value of the predictand, would get an

of 0.0. The coefficient of determination is computed according to the formula:

where

.

All metrics, in all cases, are computed using the validation dataset.

Each method and model has a set of hyperparameters that need to be initialized. In our work, to objectively select the initial values of the hyperparameters, we used the GridSearchCV method (an exhaustive search over specified parameter values for an estimator). This approach involved conducting multiple test scenarios with various combinations of hyperparameter values and evaluating the accuracy achieved in each case. However, a high number of predictors results in higher computation costs, complicated and non-robust models, and requirement of large amounts of input data. So, the final selection and tuning of the hyperparameters were based on the results of these tests and combinations, taking into account both the performance and the computational efficiency of each model during training.

In most models, only a small subset of the feature parameters contributes significantly to the overall variability of the target parameter. A ‘feature importance’ is calculated for each predictor of RF, XGBoost, and ANN (sum of weights for ANN), which effectively represents the weight each predictor carries in determining the estimated parameter. Therefore, it is logical to reduce the number of predictors by discarding those with lower importance. However, selecting a feature importance threshold can be subjective and arbitrary. To address this, we opted for a more objective selection procedure.

Initially, all models run using the full set of predictors, extracting at the same time the feature importance of each predictor. Then, for each of the models multiple runs are performed, adding in consecutive steps the predictors one-by-one, starting from those with the higher importance. The success metrics were recomputed in every step. Adding predictors was expected to improve in general the metrics and the goal was to identify a number of predictors beyond which the metrics presented only minor change. At the same time, the most efficient model was selected for the rest of analysis.

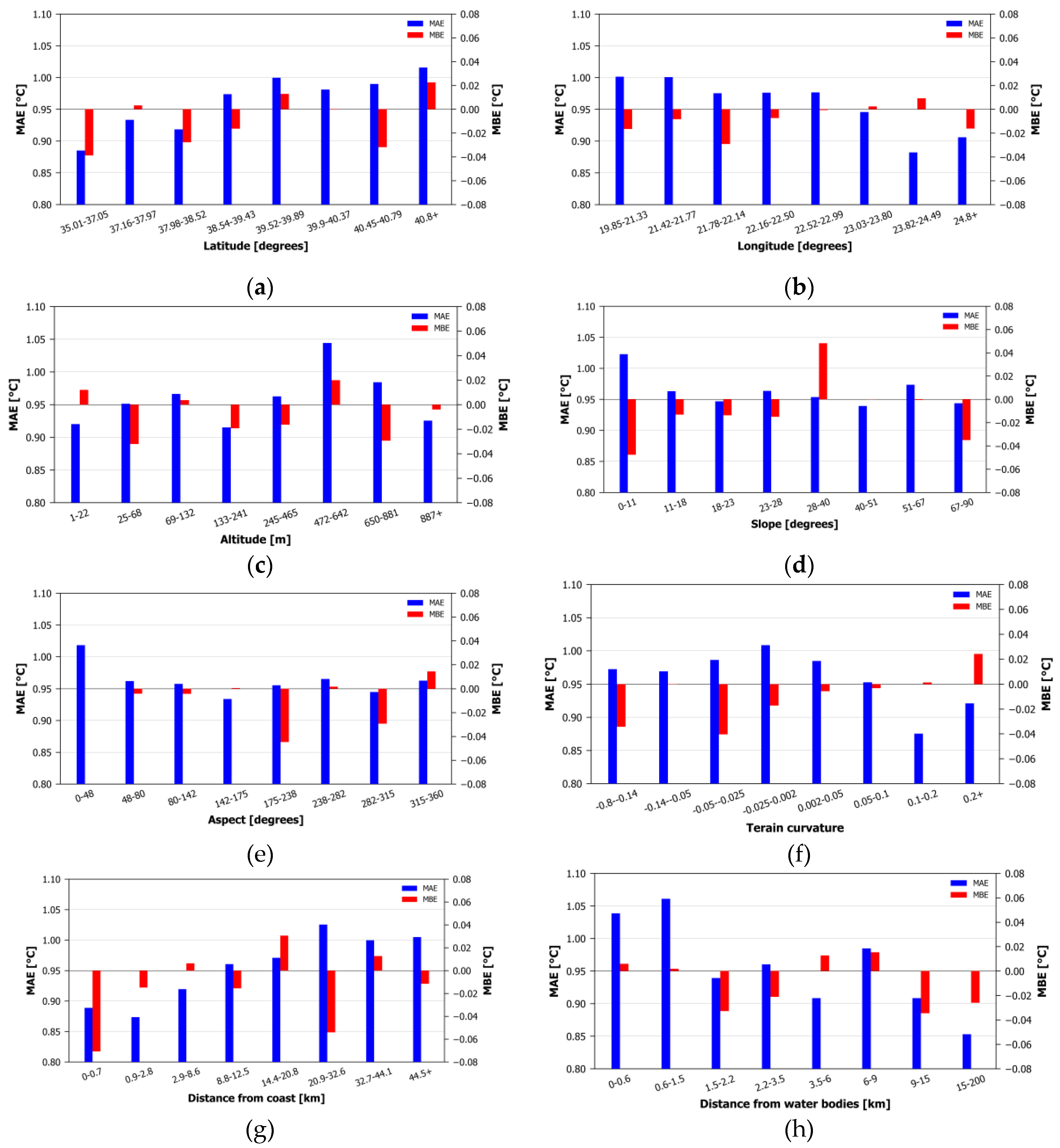

It is important to examine how our model behaves in relation to topography and time, in order to identify possible deficiencies and maybe advice caution when using it in such cases. All topography parameters, presented in

Table 2 were split in 8 bins (including a similar number of stations) and then MAE and MBE were computed for each of the bin. To identify seasonal and sub-daily changes, MAE and MBE were computed on a seasonal and hourly basis.

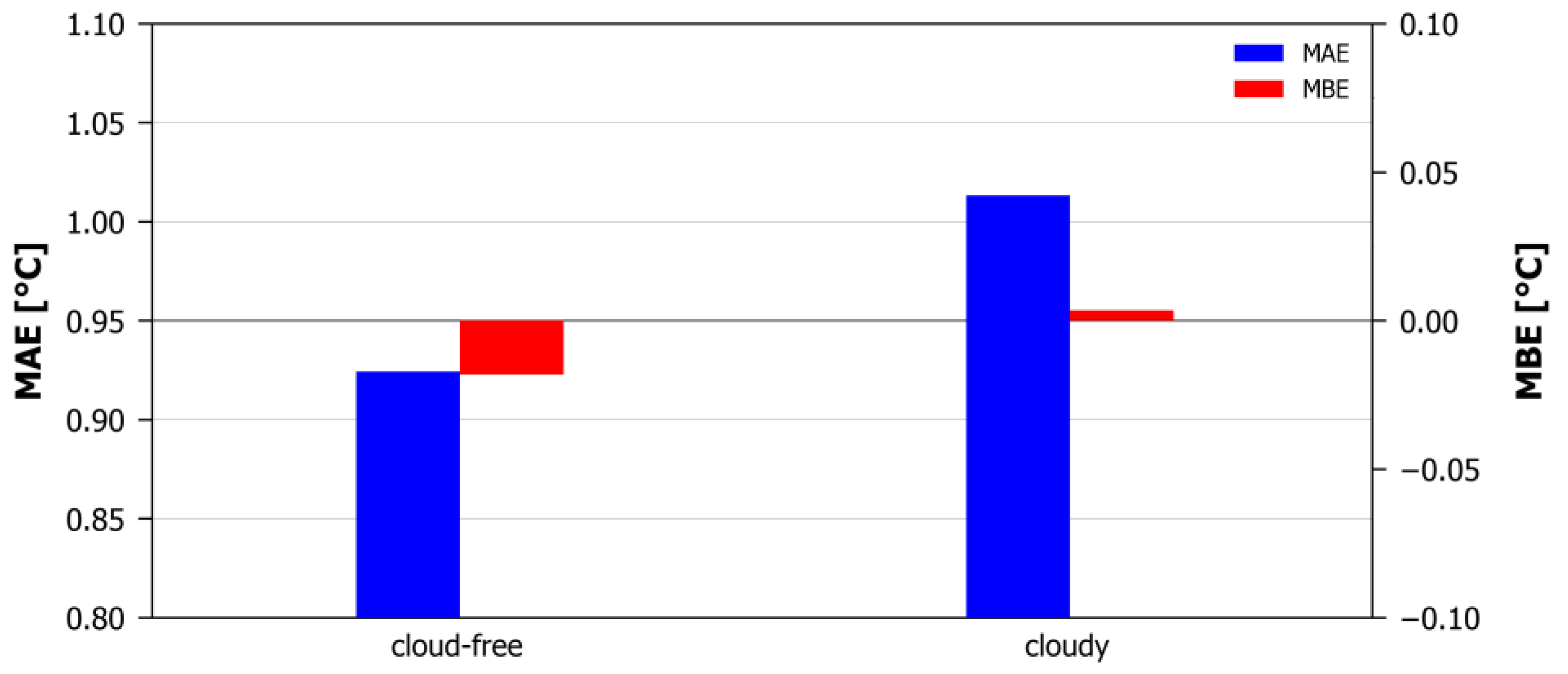

Finally, the efficiency of our model was examined under cloudy and non-cloudy conditions. The validation dataset was split in two parts. The first one comprises of the cloud-free cases while the second includes all fully or partially cloudy pixels. MAE and MBE were computed and analyzed for the two parts.

3. Results

As stated in the methodology section, our first goal was to select the most efficient method and at the same time the most important features/predictors that will be included in that model. Initially, as mentioned earlier, the GridSearchCV method was used to fine-tune the hyperparameters. By running 20 iterations and providing the hyperparameters of each method as inputs, we determined the optimal settings outlined in the models section. Additionally, our approach to model configuration during training aimed to minimize computational cost and reduce the size of the exported model files. Following this strategy, the hyperparameters were adjusted to achieve a balance between maintaining model performance and conserving storage space and computational resources.

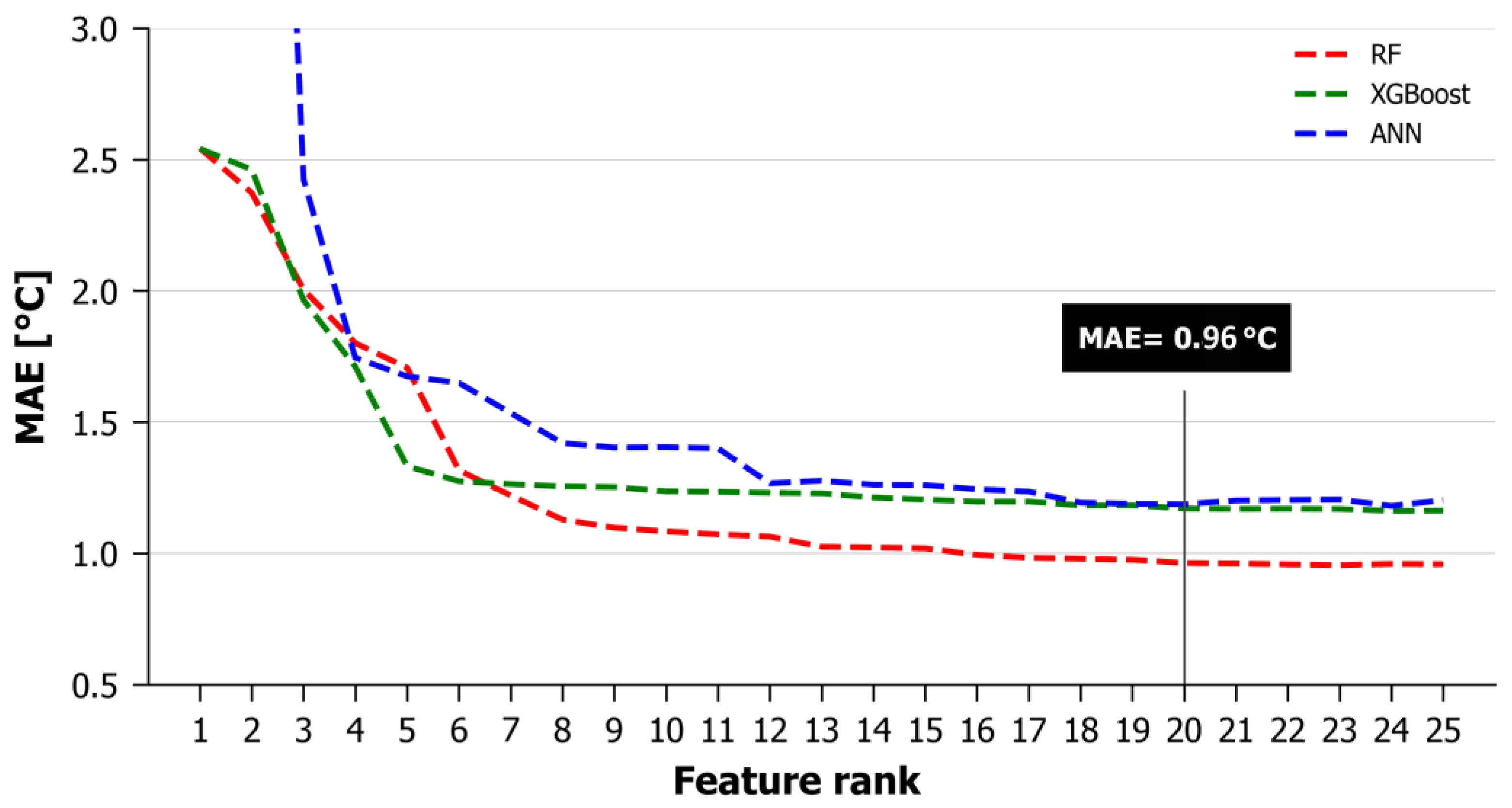

Next, each of the selected models was re-run by adding in consecutive steps the predictors starting from those with the higher importance. The success metrics were recomputed in every step. The results were introduced to metric vs predictor rank graphs and the curves produced were examined to identify a plateau in the metric value. All predictors after that plateau can be considered as non-essential and be discarded from the final models.

Figure 5 presents the graphs of MAE vs predictor rank for Random Forest (RF), XGBoost (XGB) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN). RF seems to be the most efficient model, with MAE smaller than XGBoost and ANN after the introduction of the 7

th predictor. It reaches values below 1 °C with the introduction of the 16

th predictor and after that point MAE continues to drop at clearly lower rates. So, an acceptable threshold selection could be anywhere after the 16

th or even the 7

th predictor. However, it is noted that MAE reaches a value of 0.96 °C with the introduction of the 20

th predictor and after that MAE fluctuations are negligible. MAE reaches a plateau of MAE values with the inclusion of the 20th predictor and introducing more predictors does not improve the model. Therefore, we argue that the Random Forest (RF) with 20 predictors is the most accurate and cost-efficient one, regarding the accuracy of estimations, the reduction of computational time and the limitation of input data requirements.

Regarding the rest of the metrics, and RMSE present similar behavior. MBE shows continuous fluctuations of small amplitude (smaller than 0.01 °C) for RF and XGBoost while ANN has a clearly higher MBE (in the order of 1 °C). The related figures are not presented, as they do not offer more insights or worth-mentioning information in the analysis.

The 20 predictors that were used in the Random Forest model are presented in

Table 3 in descending order of importance. As deduced from the inspection of the Feature Importance of the predictors, LST-AS dominates the formulation of NSAT, while H, SLF and Cma follow with values one order of magnitude smaller. The rest of the features present importance two orders of magnitude smaller than LST-AS and therefore their influence is rather limited.

The basic efficiency statistics of the developed model are presented in

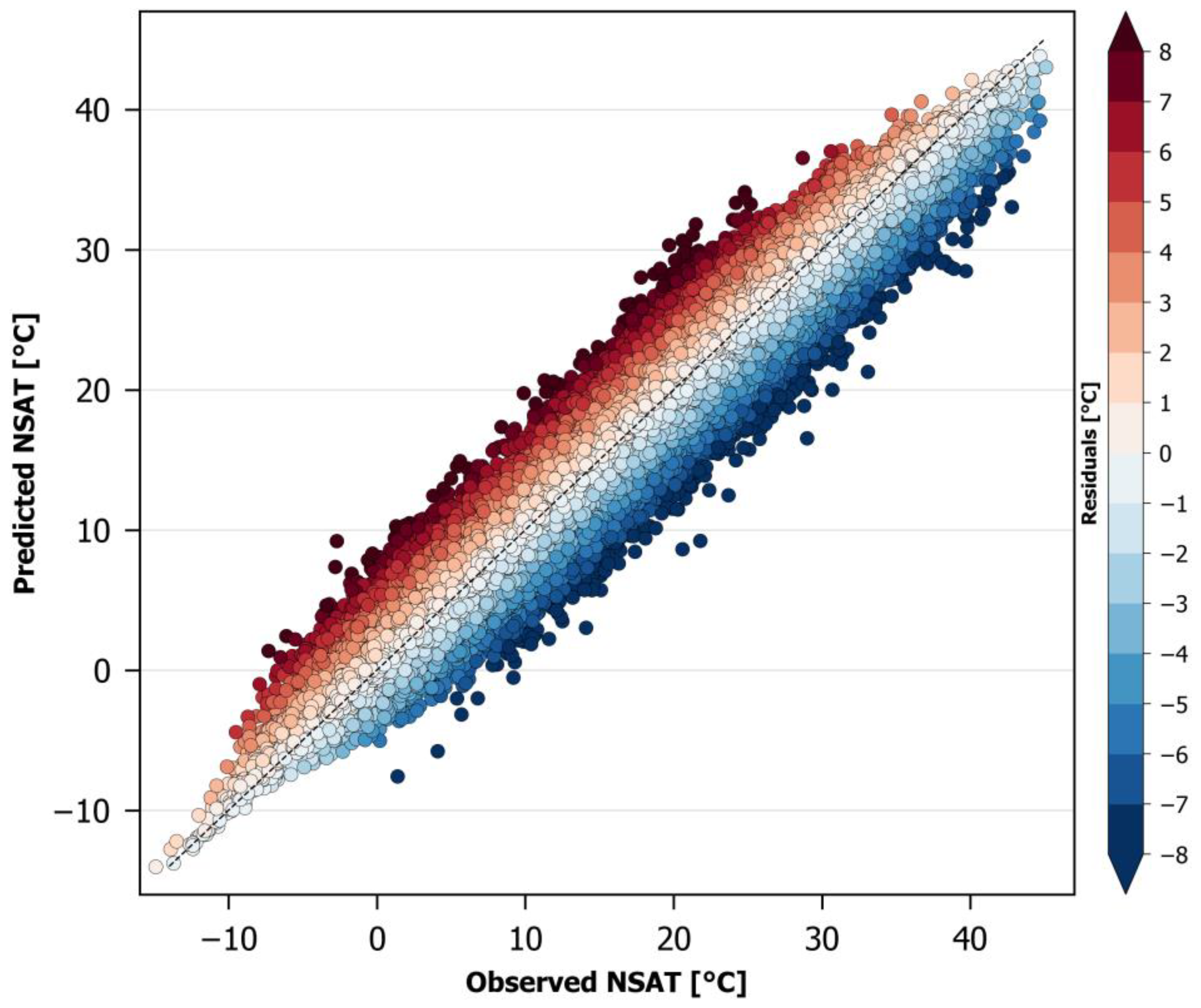

Table 4. MAE is below 1 °C (0.96 °C), indicating a quite successful model, especially when comparing to previous related works applicable only to cloud-free satellite data, where MAE ranged from 0.9 °C to over 3 °C. The MBE is -0.01 °C, suggesting a rather random dispersion of the errors above and below the diagonal (

Figure 6), with a negligible tendency for underestimation. RMSE is rather close to MAE indicating a limited influence of outliers and similar magnitudes of the individual errors, while the R

2 value that is close to 1 supports our argument that the selected model is quite efficient.

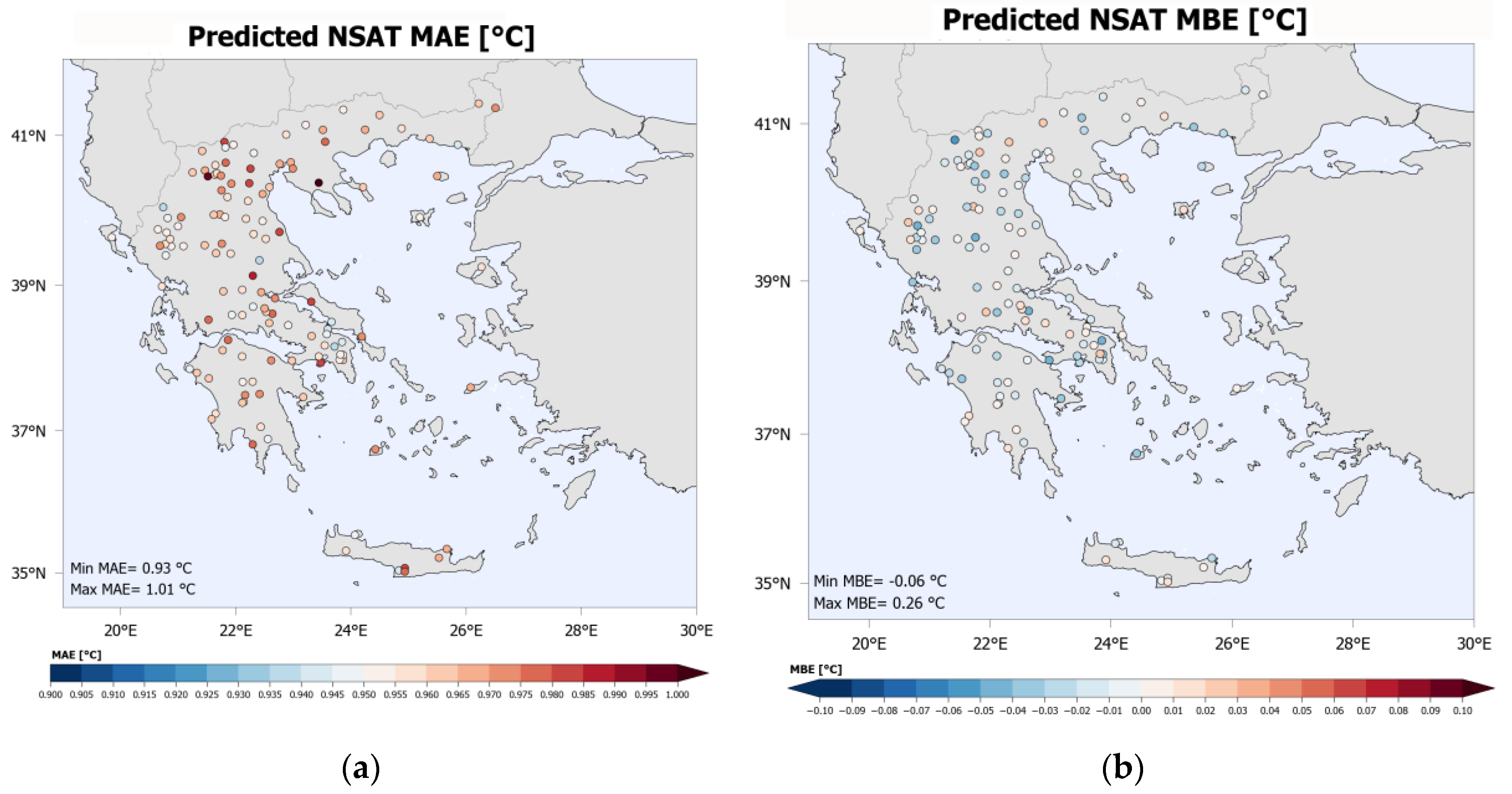

Figure 6 shows a scatter plot of the NSAT estimation errors of the Random Forest model for the complete validation dataset. The graph depicts quite clearly a balanced distribution of errors over and under the diagonal, supporting the minimal MBE (-0.01 °C).

Figure 7 illustrates (a) the MAE and (b) the MBE of the NSAT estimation per station, based, as always, only on the validation dataset. As shown in the MAE map, the absolute error ranges from 0.93 °C to 1.01 °C with fluctuations that seem to be rather unrelated to the most basic topographic features (e.g. latitude, longitude, distance to coast etc.). MBE per station ranges from -0.06 °C to 0.26 °C, again with no profound relevance to topography features. Overall, the maps and statistics presented in

Figure 7 indicate that the NSAT estimation errors are not significantly influenced by topography. However, in order to examine in some detail whether a relation between topography and estimation efficiency exists, further analysis is required.

A bin analysis was performed in order to highlight the possible influence of important topographical parameters, (namely elevation, latitude, longitude, distance to coast, distance to water bodies, slope aspect and terrain curvature) in the estimation efficiency. The validation subset was divided in 8 bins and the metrics were calculated for each bin. The bins were formulated in a manner that secured a similar number of stations for each one.

Figure 8 presents bar-charts illustrating the MAE and MBE for each of the 8 bins of the topographical parameters. Latitude and Longitude present small variations of MAE (ranging from 0.88 °C to 1.02 °C) and MBE (ranging from -0.04 °C to 0.02 °C). A limited increase of MAE is noted towards northern latitudes and western longitudes. Bias does not seem to be present a clear tendency of increase or decrease, neither preference for positive or negative sign with the increase of these two topographical parameters. MAE (ranging from 0.92 °C to 1.04 °C) and MBE (ranging from -0.03 °C to 0.02 °C) show small fluctuations with elevation change and no predominance of over- or under- estimation. Slope, MAE (ranging from 0.94 °C to 1.02 °C) shows a local maximum for slopes up to 11° followed by small fluctuations. MBE (ranging from -0.05 °C to 0.05 °C) does not show a preferred tendency. Aspect also shows a local MAE (ranging from 0.93 °C to 1.02 °C) maximum for values below 48o followed by small fluctuations afterwards. MBE (ranging from -0.04 °C to 0.01 °C) minimizes for the 175°-238° bin while for the rest of the bins, only fluctuations of varying signs exist. Terrain curvature MAE (ranging from 0.88 °C to 1.01 °C) presents a maximum around 0 with fluctuations for the rest of the bins. MBE (ranging from -0.04 °C to 0.02 °C) shows only fluctuations with no preference for over- or under- estimations. Increasing the distance to coast seems to slightly increase the MAE (ranging from 0.87 °C to 1.03 °C). MBE presents small fluctuations (ranging from -0.07 °C to 0.03 °C) with no clear preference for positive of negative bias. Regarding the distance to water bodies, MAE (ranging from 0.85 °C to 1.06 °C) is slightly higher close to the water bodies. No systematic bias (MBE is ranging from -0.03 to 0.01 °C) is noted as we approach water bodies.

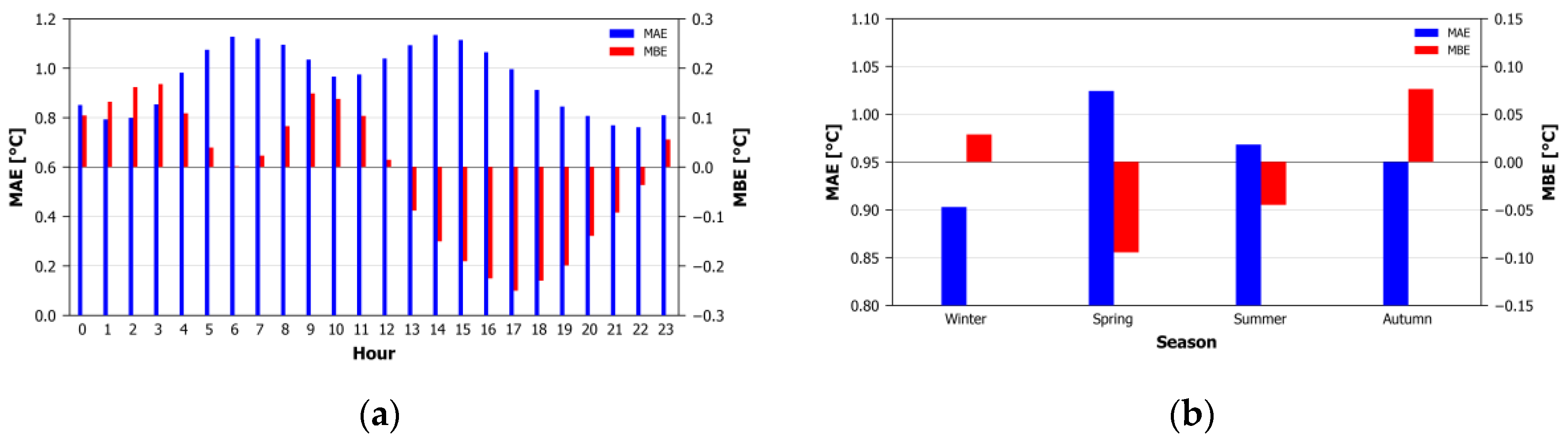

Next, in order to identify intra-daily and seasonal differences in the estimation efficiency, the validation subset was divided in 24 hourly and 4 season bins and the metrics were calculated.

Figure 9 presents bar-charts illustrating the MAE and MBE for each of the 24 hours and 4 seasonal bins. Regarding the intra-daily variation, MAE (ranging from 0.76 °C to 1.13 °C) presents two local maxima around at 06:00 and 14:00 UTC, possibly associated with the more rapid air temperature change during first morning and first afternoon hours. MBE (ranging from -0.25 °C to 0.17 °C) presents a general overestimation from the beginning of the 24-hour period until 12:00 UTC and underestimation afterwards (excepting the 23 hour bin). On the seasonal level, MAE ranges from 0.90 °C to 1.02 °C with winter presenting the lower errors and spring the higher. MBE ranges from -0.09 °C during spring to 0.08 °C during autumn, suggesting mild underestimations during spring and mild overestimations during autumn.

Finally, the possibility of accuracy degradation during cloudy conditions was examined, by splitting the evaluation dataset is cloudy and non-cloudy parts and recalculation the metrics. As seen in

Figure 10, under cloud-free conditions our model estimates NSAT with an MAE of 0.92 °C and MBE of -0.02 °C. Cloudy conditions result to a MAE of 1.01 °C and a MBE of 0.00 °C. So, as a general rule, NSAT estimations are slightly more accurate under cloud-free conditions although a marginally stronger underestimation exists compared to the negligible overestimation of the cloudy conditions. It should be noted however that the MBE is in both cases is quite small, overall suggesting that the bias of the model is negligible.

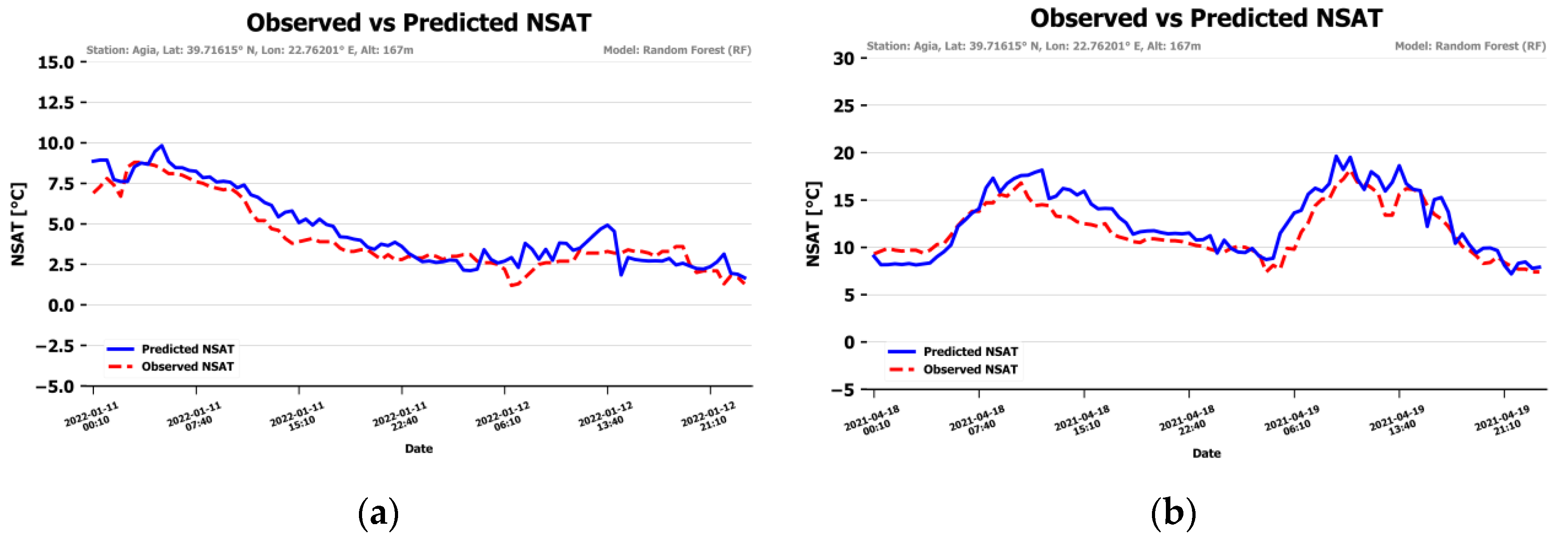

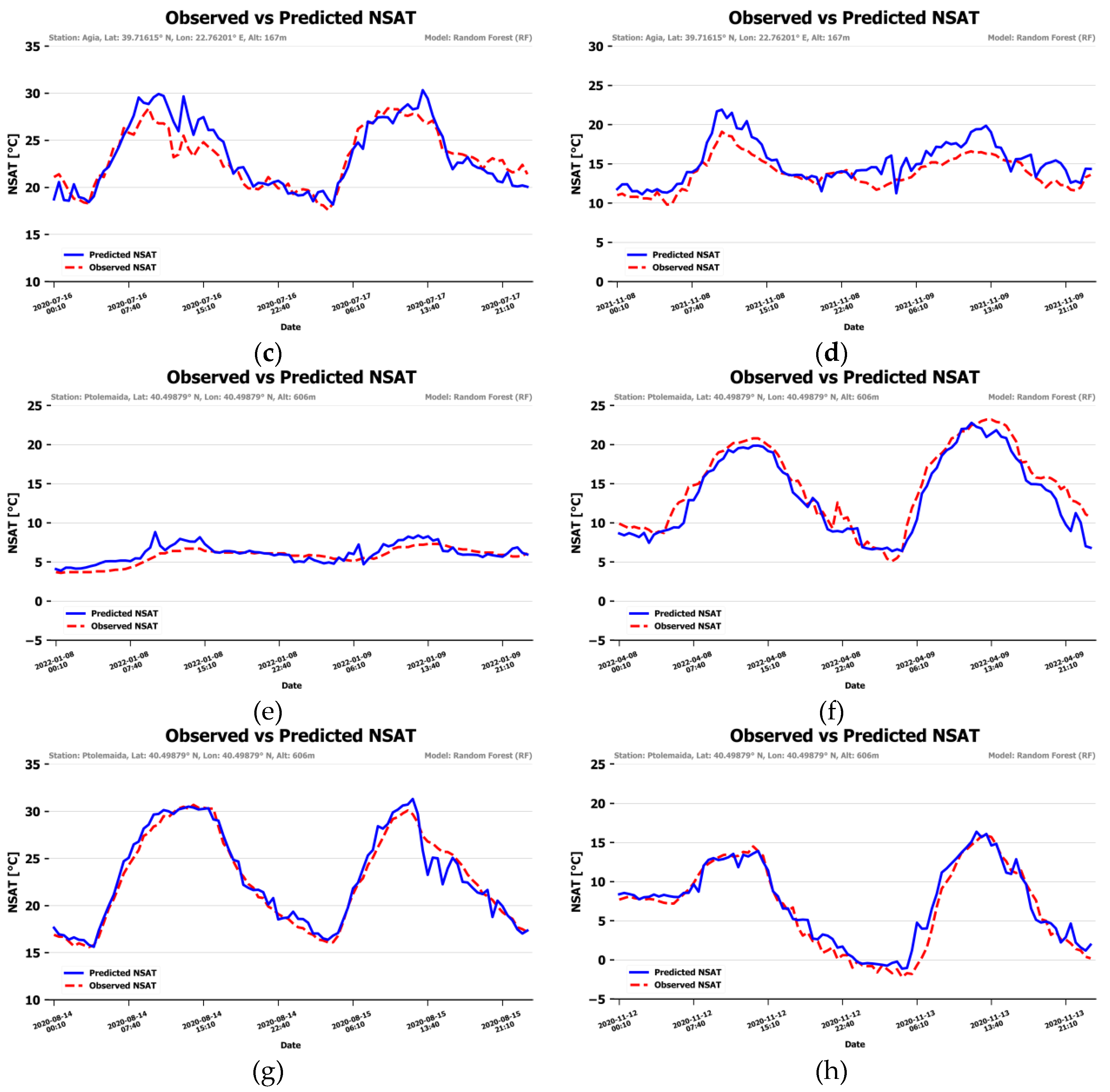

To get a visual impression of the accuracy of the NSAT consecutive days of data in winter, spring, summer and autumn were kept out of the training – validation procedure from 2 randomly selected stations (Agia and Ptolemaida). The model ran for these data and timelines of NSAT estimations and observed values were visualized.

Figure 11 presents the graphs. The blue line represents the NSAT estimation and the red dashed line represents the station observer NSAT. The predicted NSAT follows the observed one quite closely with slight deviations. Some stronger deviations are noted during the midday and afternoon hours of the first day of spring subset, the first day of summer subset and both days of autumn subset of Agia station.

4. Potential for Operational Application

Our method for near real-time estimation of NSAT under cloudy and cloud-free conditions using meteorological geostationary satellites data has significant potential for operational use. Areas covered by the LSA SAF required products can have near real-time estimations of NSAT that are completely independent from ground weather stations.

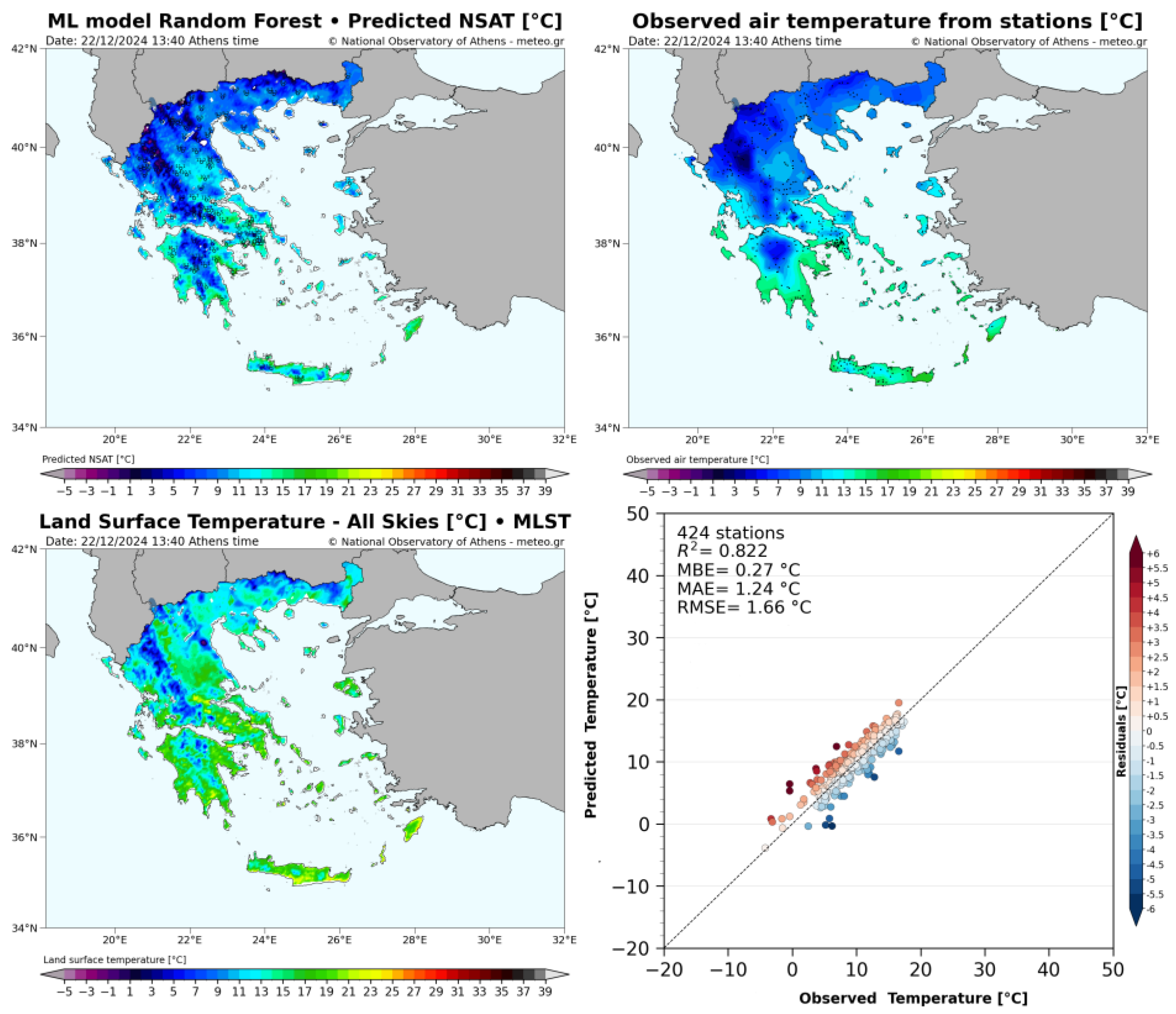

At the METEO Unit at NOA, we implemented such a near-time NSAT estimation procedure that is used at an experimental level by our forecasters. At the same time, everyday monitoring of the models’ behavior and estimation efficiency is performed, aiming to the improvement of the product through identification of strong points and deficiencies. The output of our procedure comprises, among others, of a 4-images panel (example for 22/12/2024, 13:40 Athens Time shown in

Figure 12) depicting: a map of the estimated NSAT along with selected weather stations observations (top left) a spatially interpolated map of the weather stations temperature observations (top right), a map of the most influential LSA SAF parameter of our model, the LST-AS (bottom left) and a scatter plot of the estimation errors, along with some major estimation efficiency statistics (bottom right). The spatially interpolated temperature observations field (top right) does not follow the surface topography, since information about the local differentiations is not included in the interpolation procedure. On the contrary, that information is included in the NSAT estimation procedure, resulting in a more realistic depiction of temperature. At the same time, a rather good accuracy is achieved. For the specific instance R

2, MAE and MBE equal to 0.822, 1.24 °C and 0.27 °C respectively.

The stability of the half-hourly production of that panel, using standard data acquisition methods for Eumetsat registered users, ensures us that our method could be used operationally for the estimation of NSAT in all areas, covered by the necessary LSA SAF products. National Meteorological Services, research institutes and all kinds of weather related agencies and organizations can apply and capitalize on similar real-time NSAT estimation procedures. As stated in the introduction, one major application and benefit of our method is that it could be applied over areas with sparse or absent weather station coverage to substitute temperature readings covered by the LSA SAF products.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Before presenting the main conclusions of our study and summarize the main characteristics of the NSAT model, an issue of special interest merits discussion. One of the meteorological parameters that may influence the formulation of NSAT is the horizontal wind. Air masses can transport sensible and latent heat, affecting air temperature at local scales. The exclusion of wind data from our model could be considered as a shortcoming. However, if wind data were to be included in the model, dense and high quality real-time observations would be required. Such data are not always available and even if found, they might not be representative of the sensible and latent heat transfers because low level wind is strongly affected by small-scale topography and anthropogenic constructions, especially in urban and suburban areas. It should be reminded that the temperature estimation is performed at a horizontal resolution around 5 km and small-scale wind data might not be representative of the grid-size circulation. Modeled data of comparable horizontal resolution levels could act as an alternative source of wind data. But modeled wind data are forecasts and not observations or even real-time estimations, unavoidably introducing uncertainties that will act as additional sources of errors. Moreover, modeled data may suffer from other innate deficiencies related to inaccurate representation of topography and human constructions, again especially in urban and suburban areas. Since our goal was to create an easy to apply model of NSAT estimation in near real-time mode, based on publicly available datasets we decided to exclude the hard to find and uncertainties ridden wind data. We should also keep in mind that certain algorithms of the LSA SAF products include ECMWF model 10 meters wind data, partially circumventing the problem.

As stated in the introduction, significant literature exists in the subject of estimating the near surface air temperature from satellite data. None of them is able to perform under cloudy conditions, which is a significant problem, especially regarding real-time nowcasting applications. During cyclonic conditions predominance, cloudiness is quite increased and clear sky methodologies fail to estimate temperature. Our model is able to deliver NSAT estimations regardless of cloudiness and moreover in near real-time mode, provided that access to the required LSA SAF data is secured. The analysis of the overall performance of the model showed only marginally more accurate estimations under cloud-free conditions, supporting our argument that the model is fit to be used regardless of sky conditions.

Regarding the predictors that seem to be the most influential, we should comment the following:

LST-AS is the predominant parameter. The well-known immediate thermal interaction of land surface and near surface air masses supports that finding;

H is the second most influential parameter, in agreement with the notion that sensitive heat flux directly affects air temperature;

SLF and its 30 min difference are also among the most important features. Incoming longwave radiation affects directly the air temperature, and has a significant role in the formulation of NSAT;

Cma participates in the formulation of NSAT, as expected, since the presence of clouds affects the energy budget;

The rest of the predictors contribute to a much lesser extent.

The validation dataset estimations of NSAT were divided in bins of topography and time parameters. MAE and MBE were computed for these bins, aiming to identify characteristics, strong points or shortcomings of our model. It was shown that our model is rather unaffected by most of them, with the exception of latitude and longitude, where mild increase of errors was noted towards north and west. Mild increase of errors was also noted as we move away from the coastline and towards water bodies. A limited seasonality exists, while during the day, the higher errors occur during the first morning and afternoon hours, when the most rapid temperature changes are usually noted. A tendency for overestimation was found until midday with an underestimation afterwards.

The machine learning models were trained using Python scripting. After training, the models were exported in their final form and saved. These pre-trained models can generate predictions straightforwardly when provided with the necessary static and dynamic parameters (such as LSA SAF products) on which they were originally trained. The computational time ranges from seconds to minutes, depending on the infrastructure. Generating air temperature estimates for a relatively small region, such as Greece, is efficient and fast. Applying the model to larger regions would require more time but, based on our estimation, should still be completed within several minutes. Overall, our model has a significant potential of operational use, as it is fast, straightforward and stable, provided that the necessary data are available.

Our model could be run in other mid-latitude regions of similar topography and climate characteristic with Greece. NSAT over Greece varies rather largely from values below zero in winter (-5 °C to -10 °C are often, especially in mountainous areas) to over 40 °C in summer (mainly in landlocked, low elevation areas). This results to a wide range of temperatures for training and validation and gives as the confidence that it could be applied with similar efficiency to other mid-latitude regions with similar temperature ranges. Nonetheless, a new training/validation over the desired region could be beneficial before application.

A challenging and highly desired next step would be to train and operate the model over poorly covered by weather stations areas around the world, inside the Meteosat field of view. The operation of the model over Africa for example, that lacks adequate coverage by weather stations (at least large parts of it) could be proved quite beneficial, for public authorities, environmental and health organizations, stakeholders and the general public of the continent. Moreover, the Meteosat Third Generation Imager 1 (MTG-I1) operational Flexible Combined Imager (FCI) data is now available. These data will offer higher horizontal and temporal resolution and more spectral channels. Near real-time LSA SAF products are also expected to be available in the FCI higher resolution. It is anticipated that all parameters (derived from MSG SEVIRI) that were used here as predictors for our model, will present higher accuracy when derived from FCI data. As a consequence, the re-training of the model over larger areas using FCI data could lead to even higher degrees of accuracy. In our future work it is planned to include such a retraining, using Central and Southern Europe and Africa weather stations observations as ground truth, towards the development of an even more accurate and widely applicable model of estimation of NSAT.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K.; methodology, A.K. and G.K.; software, A.K. and G.K.; validation, A.K. and G.K.; formal analysis, A.K., G.K. K.L, V.K.; investigation, A.K., G.K. K.L. and V.K; resources, L.K. and V.L.; data curation, A.K. and G.K; writing—original draft preparation, A.K. and G.K.; writing—review and editing, A.K, G.K., K.L. and V.K.; visualization, A.K. and G.K.; supervision, A.K., K.L. and V.K.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the General Secretariat of Research and Innovation (GSRI) under project “CLIMPACT: Support for upgrading the operation of the national network for climate change”, financed by the national section of the PDE National Development Program 2021-2025, Ministry of Development – General Secretariat of Research and Innovation.

Data Availability Statement

The LSA SAF data analyzed are publicly available through the LSA SAF website. No other publicly available datasets were used.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the contribution of the LSA SAF to this study for the provision of the publically available datasets and the sun zenith angle data. We also acknowledge partial funding of this research by project "Climpact: Support for upgrading the operation of the national network for climate change" financed by the national section of the PDE National Development Program 2021-2025, Ministry of Development – General Secretariat of Research and Innovation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Stisen, S.; Sandholt, I.; Nørgaard, A.; Fensholt, R.; Eklundh, L. Estimation of diurnal air temperature using MSG SEVIRI data in West Africa. Remote Sens. Environ. 2007, 110, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prihodko, L.; Goward, S.N. Estimation of air temperature from remotely sensed surface observations. Remote Sens. Environ. 1997, 60, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakšek, K.; Schroedter-Homscheidt, M. Parameterization of air temperature in high temporal and spatial resolution from a combination of the SEVIRI and MODIS instruments. ISPRS J. Photogramm Remote Sens. 2009, 64, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, H.; Sandholt, I.; Aguado, I.; Chuvieco, E.; Stisen, S. Air temperature estimation with MSG-SEVIRI data: Calibration and validation of the TVX algorithm for the Iberian Peninsula. Remote Sens. Environ 2011, 115, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Leptoukh, G.G. Estimation of surface air temperature over central and eastern Eurasia from MODIS land surface temperature. Environ. Res. Lett. 2011, 6, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Hengl, T.; Heuvelink, G.B.M.; Perčec Tadić, M.; Pebesma, E.J. Spatio-temporal prediction of daily temperatures using time-series of MODIS LST images. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2012, 107, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmentier, B.; McGill, B.; Wilson, A.M.; Regetz, J.; Jetz, W.; Guralnick, R.P.; Tuanmu, M.-N.; Robinson, N.; Schildhauer, M. An Assessment of Methods and Remote-Sensing Derived Covariates for Regional Predictions of 1 km Daily Maximum Air Temperature. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 8639–8670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janatian, N.; Sadeghi, M.; Sanaeinejad, S.H.; Bakhshian, E.; Farid, A.; Hasheminia, S.M.; Ghazanfari, S. A statistical framework for estimating air temperature using MODIS land surface temperature data. Int. J. Climatol. 2016, 3, 1181–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooker, J.; Duveiller, G.; Cescatti, A. A global dataset of air temperature derived from satellite remote sensing and weather stations. Sci. data 2018, 5.1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hough, I.; Just, A.C.; Zhou, B.; Dorman, M.; Lepeule, J.; Kloog, I. A multi-resolution air temperature model for France from MODIS and Landsat thermal data. Environ. Res. 2020, 183, 109244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascetti, A.; Monterisi, C.; Iurrilli, F.; Sonnessa, A. A neural network regression model for estimating maximum daily air temperature using Landsat-8 data. ISPRS Archives 2022, 43, 1273–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUMETSAT. Available online: https://www.eumetsat.int (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Land Surface Analysis SAF. Available online: https://landsaf.ipma.pt/en/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Geodata.gov.gr Datasets. Available online: https://geodata.gov.gr/en/dataset (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Copernicus. Available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/imagery-in-situ/eu-dem/eu-dem-v1.1 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Lagouvardos, K.; Kotroni, V.; Bezes, A.; Koletsis, I.; Kopania, T.; Lykoudis, S.; Mazarakis, N.; Papagiannaki, K.; Vougioukas, S. The automatic weather stations NOANN network of the National Observatory of Athens: Operation and database. Geosci. Data J. 2017, 4, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meenal, R.; Michael, P.A.; Pamela, D.; Rajasekaran, E. Weather prediction using random forest machine learning model. Indones. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2021, 22, 1208–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyros, G.; Manolas, I.; Diamantaras, K.; Dafis, S.; Lagouvardos, K. A machine learning approach for rainfall nowcasting using numerical model and observational data. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2023, 26, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Suthar, G.; Singh, S.; Kaul, N.; Khandelwal, S.; Singhal, R.P. Prediction of maximum air temperature for defining heat wave in Rajasthan and Karnataka states of India using Machine Learning Approach. Remote Sens. Appl. 2023, 32, 101048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost. In A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Osman, A.I.A.; Ahmed, A.N.; Chow, M.F.; Huang, Y.F.; El-Shafie, A. Extreme gradient boosting (Xgboost) model to predict the groundwater levels in Selangor Malaysia. Ain. Shams. Engineering Journal, 2021, 12, 1545–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.T.K.; Bateni, S.M.; Ki, S.J.; Vosoughifar, H. A review of neural networks for air temperature forecasting. Water, 2021, 13, 1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.S. Forecasting the air temperature at a weather station using deep neural networks. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 178, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, S.; Jhajharia, D.; Chattopadhyay, G. Univariate modelling of monthly maximum temperature time series over northeast India: neural network versus Yule–Walker equation based approach. Meteorol. Appl. 2021, 18, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjali, T.; Chandini, K.; Anoop, K.; Lajish, V.L. Temperature Prediction using Machine Learning Approaches. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Intelligent Computing, Instrumentation and Control Technologies (ICICICT), Kannur, Kerala, India, 5–6 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- WWRP/WGNE Joint Working Group on Forecast Verification Research: Forecast Verification methods Across Time and Space Scales (2015). Available online: https://www.cawcr.gov.au/projects/verification/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

Figure 1.

Locations of the 126 weather stations of the METEO/NOA network overlaid on the Greek topography.

Figure 1.

Locations of the 126 weather stations of the METEO/NOA network overlaid on the Greek topography.

Figure 2.

Conceptual schematic of Random Forest technique.

Figure 2.

Conceptual schematic of Random Forest technique.

Figure 3.

Conceptual schematic of the Extreme Gradient Boosting model.

Figure 3.

Conceptual schematic of the Extreme Gradient Boosting model.

Figure 4.

Conceptual schematic of the Simple Multilayer Perceptron Neural Network.

Figure 4.

Conceptual schematic of the Simple Multilayer Perceptron Neural Network.

Figure 5.

MAE vs predictor rank for the 3 models.

Figure 5.

MAE vs predictor rank for the 3 models.

Figure 6.

Scatter plot of the NSAT estimation errors of the Random Forest model.

Figure 6.

Scatter plot of the NSAT estimation errors of the Random Forest model.

Figure 7.

MAE (a) and MBE (b) of the NSAT estimation per station.

Figure 7.

MAE (a) and MBE (b) of the NSAT estimation per station.

Figure 8.

MAE and MBE for 8 different bins of the topography parameters.

Figure 8.

MAE and MBE for 8 different bins of the topography parameters.

Figure 9.

MAE and MBE for (a) the 4 seasonal and (b) the 24 hourly bins.

Figure 9.

MAE and MBE for (a) the 4 seasonal and (b) the 24 hourly bins.

Figure 10.

MAE and MBE for cloud-free and cloudy pixels.

Figure 10.

MAE and MBE for cloud-free and cloudy pixels.

Figure 11.

NSAT predictions vs temperature observations in winter, spring, summer and autumn for the “Agia” (a-d) and “Ptolemaida” (e-h) weather stations.

Figure 11.

NSAT predictions vs temperature observations in winter, spring, summer and autumn for the “Agia” (a-d) and “Ptolemaida” (e-h) weather stations.

Figure 12.

Operational NSAT estimation panel of NOA forecasting team: (top left) map of the estimated NSAT along with selected weather stations observations, (top right) map of spatially interpolated temperature observations, (bottom left) map of the most important parameter of our model, the LST-AS (bottom right) scatter plot of the estimation errors, along with major estimation efficiency statistics.

Figure 12.

Operational NSAT estimation panel of NOA forecasting team: (top left) map of the estimated NSAT along with selected weather stations observations, (top right) map of spatially interpolated temperature observations, (bottom left) map of the most important parameter of our model, the LST-AS (bottom right) scatter plot of the estimation errors, along with major estimation efficiency statistics.

Table 1.

Land SAF products, along with their maximum temporal resolution and their acronym.

Table 1.

Land SAF products, along with their maximum temporal resolution and their acronym.

| Land SAF product |

Maximum Temporal resolution |

Abbreviation |

| Total and Diffuse Downward Surface Shortwave Flux |

15 min |

SSF |

| Downward Surface Longwave Flux |

30 min |

SLF |

| Latent Heat Flux |

30 min |

LE |

| Sensible Heat Flux |

30 min |

H |

| Evapotranspiration |

30 min |

ET |

| Land Surface Temperature – All Sky |

30 min |

LST-AS |

| Cloud Mask from Land Surface Temperature – All Sky |

30 min |

Cma LST-AS |

| Daily Fraction of Vegetation Cover |

Daily |

FVC |

| Daily Leaf Index |

Daily |

LAI |

| Daily Fraction of Absorbed Photosynthetic Active Radiation |

Daily |

fAPAR |

| Daily Surface Albedo |

Daily |

AL |

Table 2.

Static topographic parameters, along with their source, units and description.

Table 2.

Static topographic parameters, along with their source, units and description.

| Static Parameter |

Acronym |

Source |

Units and description |

| Station latitude |

Lat |

METEO/NOA |

Latitude (°) of station |

| Station longitude |

Lon |

METEO/NOA |

Longitude (°) of station |

| Station elevation |

Ele |

METEO/NOA |

Elevation (m) of station |

| Distance to water bodies |

Dwb |

Geodata.gov.gr |

Station distance (m) to lakes and main rivers |

| Distance to coastline |

Dcl |

Geodata.gov.gr |

Station distance (m) to coastline |

| Slope |

Slo |

Copernicus / eu-dem-v1.1-25m |

Terrain slope (°) at the location of station |

| Aspect |

Asp |

Copernicus / eu-dem-v1.1-25m |

Terrain aspect (°) at the location of the station |

| Curvature |

Cur |

Copernicus / eu-dem-v1.1-25m |

Terrain curvature (1/100 z-units) at the location of the station |

Table 3.

Feature importance of the 20 predictors ingested in the RF model.

Table 3.

Feature importance of the 20 predictors ingested in the RF model.

| No |

Predictor |

Feature Importance |

No |

Predictor |

Feature Importance |

| 1 |

LST-AS |

0.851 |

11 |

Cur |

0.0023 |

| 2 |

H |

0.036 |

12 |

Dwb |

0.003 |

| 3 |

SLF |

0.035 |

13 |

AL (VI-DH) |

0.003 |

| 4 |

Cma LST-AS |

0.012 |

14 |

Dcl |

0.002 |

| 5 |

SLF 30min dif |

0.005 |

15 |

Lon |

0.002 |

| 6 |

Altitude |

0.005 |

16 |

FAPAR |

0.002 |

| 7 |

Slope |

0.004 |

17 |

AL (BB-BH) |

0.002 |

| 8 |

AL (NI-DH) |

0.003 |

18 |

ET 30 min dif |

0.002 |

| 9 |

Lat |

0.003 |

19 |

AL (BB-DH) |

0.002 |

| 10 |

SZA |

0.003 |

20 |

LAI |

0.002 |

Table 4.

Efficiency metrics of the 20 predictors of the Random Forest model of NSAT estimation.

Table 4.

Efficiency metrics of the 20 predictors of the Random Forest model of NSAT estimation.

| R2 |

0.976 |

| MAE |

0.96 °C |

| MBE |

-0.01 °C |

| RMSE |

1.34 °C |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).