1. Introduction

In recent times healthcare service delivery has greatly transformed, and this is driven by the extensive adoption of technology in the provision of patient care, medical research and the medical administration. No doubt. this digital explosion has brought about efficiency, better patient outcomes, and enabled sustained innovative approaches to healthcare delivery. However, it has also introduced significant vulnerabilities that threaten the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of sensitive healthcare data. Today, there is an increased reliance on electronic health records (EHRs), interconnected medical devices, and telehealth platforms, which has in turn expanded the attack surface for cyber threats, making robust privacy and security measures germane. As highlighted by the American Hospital Association, healthcare providers are faced with evolving cyber threats, like ransomware and phishing attacks, that can compromise patient safety and privacy, leading to financial losses, reputational damage, and legal repercussions. The protection of patient privacy, mandated by regulations such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) , stresses the great need for secure and privacy-focused software in healthcare systems. Therefore, there is an urgent need to secure the software that handle this data in an effort to sustain security and privacy by design.

However, even with the recognized importance of security in healthcare systems, existing datasets for vulnerability detection often fail to address the specific privacy concerns peculiar to this domain, such as compliance with HIPAA or the specific vulnerabilities in EHRs and Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) devices. Datasets such as those derived from the National Vulnerability Database (NVD), as seen in

Table 1, provide comprehensive vulnerability information but lack detailed mappings to privacy-specific threats, limiting their utility for healthcare applications [

1]. For example, the NVD includes vulnerabilities related to medical software and devices but does not systematically correlate these with privacy risks, such as unauthorized access to patient data. Similarly, intrusion detection datasets like KDD-Cup'99 and NSL-KDD, while valuable for general cyber security research, are outdated or not tailored to the healthcare context, relying on generic security labels that do not capture the nuances of privacy threats [

2,

3]. This gap in existing resources highlights the important need for a dataset that specifically focuses on privacy-aware vulnerability detection in healthcare systems.

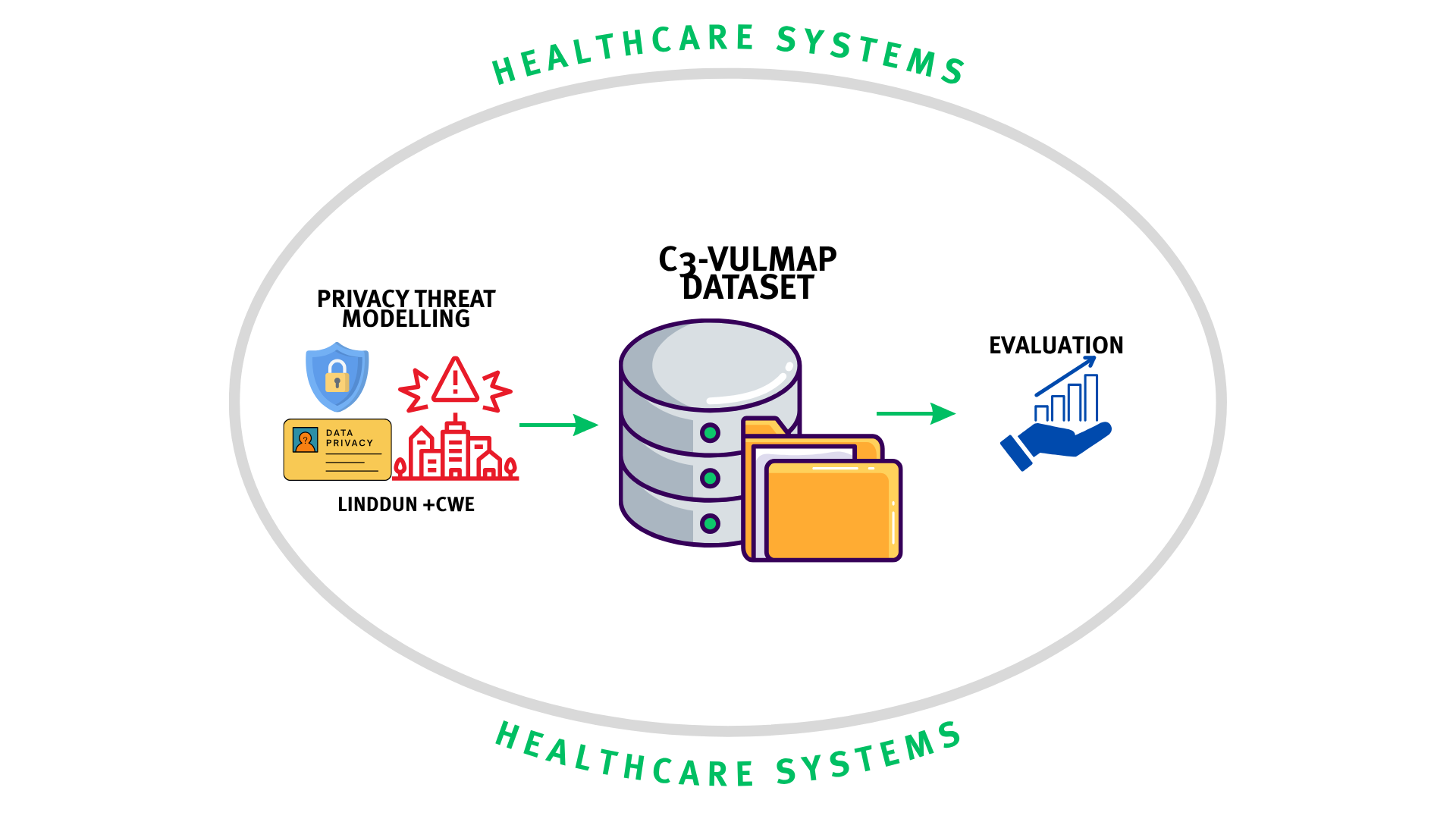

To fill this gap, we introduce C3-VULMAP, a niche dataset designed to facilitate the development and evaluation of privacy-focused security models in healthcare. This is motivated by the recognition that privacy breaches in healthcare can have severe consequences, not only for individual patients but also for public trust in healthcare institutions. Cyberattacks targeting healthcare systems, can lead to unauthorized disclosure of sensitive patient information, disrupt critical care delivery, and result in significant harm. By focusing on privacy-aware vulnerability detection, C3-VULMAP aims to enable the creation of more effective security measures that protect patient data while ensuring compliance with privacy regulations. The dataset is intended to serve as a foundational resource for researchers and practitioners in creating advanced and specific cybersecurity solutions for the healthcare sector.

The applicability and scope of C3-VULMAP includes a wide range of healthcare software and systems, including EHRs, medical device software, telehealth platforms, and other digital health technologies. Unlike existing datasets, C3-VULMAP includes software code vulnerabilities with direct implications for patient privacy, annotated with relevant privacy threats and mapped to corresponding Common Weakness Enumeration (CWE) types. These annotations are further correlated with the LINDDUN framework, a privacy threat modelling methodology. This systematic approach allows for a deeper understanding of how specific vulnerabilities can lead to privacy breaches, facilitating the development of targeted and effective security solutions. The dataset is designed to be applied in several ways, from training machine learning models for vulnerability detection to informing the design of secure healthcare software.

The contributions of this work are threefold, addressing both the practical and research needs of the healthcare cybersecurity community:

- i.

Dataset Creation: We present C3-VULMAP, a novel dataset specifically curated for privacy-aware vulnerability detection in healthcare systems.

- ii.

Systematic Correlation with LINDDUN and CWE: C3-VULMAP establishes a systematic correlation between its vulnerabilities and established frameworks, namely LINDDUN for privacy threat modelling and CWE for software weakness enumeration.

- iii.

Comprehensive Model Evaluations: We conduct extensive evaluations of various machine learning and security models using C3-VULMAP, demonstrating its utility in improving the detection and prevention of privacy breaches in healthcare systems.

By providing a dedicated resource for privacy-aware vulnerability detection, this dataset paves the way for more secure, trustworthy, and compliant healthcare systems. The rest of the paper covers the review of related works, followed by the evaluation methodology, and the presentation of the results, an in-depth discussion, limitations and closes with a conclusion.

2. Related Works

Vulnerabilities in software are a threat to the integrity of information systems, especially in healthcare. The rise of machine learning (ML) has prompted the development of automated vulnerability detection tools, but their effectiveness hinges on the quality and scope of training datasets [

4,

5]. Datasets for ML should go beyond the use for general vulnerability detection and more into privacy threat modelling, an important requirement in healthcare where patient data confidentiality is principal [

6,

7,

8].

2.1. Review of Existing Vulnerability Datasets

Vulnerability datasets are foundational to training ML-based detection tools, even so, their diversity in scope and methodology presents both opportunities and challenges. Several datasets have significantly contributed to vulnerability detection research, each with distinctive strengths and limitations. For instance, Big-Vul, a dataset that is prominently utilized for code-centric analysis [

9], has an expansive scope and general vulnerability focus that limits its direct applicability in privacy-sensitive domains such as healthcare. While DiverseVul, another remarkable dataset expands the dataset scale considerably, offering 18,945 vulnerable functions from diverse real-world security trackers, enhancing model performance across varied contexts [

10]. However, its lack of explicit integration with privacy frameworks similarly restricts its utility for privacy-focused applications. The ReposVul dataset innovatively addresses repository-level complexities, such as tangled patches and outdated fixes, using large language models (LLMs) for labelling. It covers 236 CWE types across four programming languages, significantly advancing inter-procedural vulnerability detection [

11]. However, its approach does not incorporate privacy threat modelling frameworks. In the CVEfixes dataset, encompassing 5,365 CVEs, there is a robust support for predictive modelling and automated vulnerability repair, demonstrating versatility for general cybersecurity applications [

12]. Like the previously mentioned datasets, CVEfixes neglects specific privacy considerations crucial in healthcare contexts.

Recent analyses emphasize the critical need for contextually relevant datasets. The authors [

5] introduced VALIDATE used to highlight issues such as dataset availability and feature diversity in vulnerability prediction. Similarly, [

13] identified persistent challenges, including imbalanced samples and the demand for domain-specific datasets, especially pertinent in sensitive sectors like healthcare [

14]. The foregoing is an indication for the need for specialized datasets that actively integrates privacy considerations with security in the healthcare domain.

2.2. Limitations Concerning Privacy Threat Modelling

Given the significant limitation of existing vulnerability datasets in integrating threat modelling frameworks that could identify and mitigate privacy risks, leaves much to be desired [

15]. The absence of privacy-aware datasets hinders the development of detection tools that comply with regulations like HIPAA and GDPR, increasing the risk of data breaches [

7]. Further, in healthcare, where the risks are significantly higher, the authors [

6] noted that big data analytics hold great potential for improving patient outcomes but require robust security measures to prevent unauthorized access. Similarly, [

7] highlight the growing frequency of cyberattacks on healthcare systems, advocating for sociotechnical solutions that embed privacy considerations.

The integration of privacy threat modelling into system development is an important approach for addressing the abundance of data protection related challenges, particularly as information systems become increasingly pervasive. Among the various methodologies available, LINDDUN, an acronym encapsulating seven categories of privacy threats: Linkability, Identifiability, Non-repudiation, Detectability, Disclosure of information, Unawareness, and Non-compliance, offers a robust and systematic framework. Developed at KU Leuven, LINDDUN provides a structured approach to identifying and mitigating privacy threats within system architectures, making it particularly suitable for contexts where data privacy is heralded [

16]. Unlike security-focused frameworks such as STRIDE, which primarily addresses threats like spoofing and tampering, LINDDUN is explicitly designed to tackle privacy concerns, thereby filling a critical gap in threat modelling methodologies. Its comprehensive categorization of privacy threats and its adaptability across diverse domains justify its selection as a preferred framework for privacy threat modelling, as it ensures a thorough analysis of potential vulnerabilities that might otherwise be overlooked [

17].

The strength of LINDDUN is apparent from its widespread application in recent academic research, where its versatility and robustness across various sectors is showcased. For instance, [

18] explored the application of LINDDUN GO, a streamlined variant of the framework, in the context of local renewable energy communities. Their findings showed how LINDDUN was able to effectively identify privacy threats in decentralized energy systems, where data sharing among community members could be a significant risk. Similarly, [

19] emphasized the importance of developing robust and reusable privacy threat knowledge bases, leveraging LINDDUN to enhance the consistency and scalability of threat modelling practices. Furthermore, [

20] tailored LINDDUN to the automotive industry, addressing privacy concerns in smart cars. By proposing domain-specific extensions to the methodology, they demonstrated its flexibility in accommodating the unique challenges of emerging technologies, such as connected vehicles, where personal data is continuously generated and transmitted.

In addition to its adaptability, the structured approach of LINDDUN has demonstrated effectiveness in complex, data-intensive environments. For instance, [

21] applied LINDDUN to model privacy threats in national identification systems, illustrating its utility in safeguarding large-scale identity management architectures. Their work demonstrates the capacity of LINDDUN to handle the intricate interplay of personal data in systems that serve millions of users, where breaches could have far-reaching societal implications. Similarly, [

22] developed a test bed for privacy threat analysis based on LINDDUN, focusing on patient communities. This application highlights the suitability of the framework for healthcare systems, where the confidentiality of sensitive medical data is critical.

The choice of LINDDUN, is further justified by its targeted focus on privacy threats, which are often inadequately addressed by security-centric frameworks. While STRIDE excels in identifying threats to system integrity and availability, it lacks the granularity required to address nuanced privacy concerns, such as linkability or unawareness [

23]. The comprehensive threat categories in LINDDUN enable analysts to systematically evaluate the privacy vulnerabilities in a system, ensuring that no aspect of data protection is overlooked. Additionally, its iterative process, which involves mapping system data flows, identifying threats, and proposing mitigations, aligns well with modern system development lifecycles, where privacy must be embedded from the design phase. Moreso, its adaptability of the framework to diverse domains, from energy systems to healthcare and automotive industries, further enhances its appeal, as it allows researchers and practitioners to tailor its application to specific contexts without sacrificing its core principles.

3. Dataset Construction

The construction of the dataset involved a methodical approach to aggregating, filtering, and processing vulnerability data specifically for healthcare systems. Our data collection methodology prioritized privacy-centric vulnerabilities while ensuring relevance to real-world healthcare applications, with particular attention to the nuanced requirements of healthcare privacy regulations and the technical specificity of medical software systems.

3.1. Modified LINDDUN Process

The foundation of our data collection process was built upon a modified LINDDUN privacy threat modelling methodology, specifically adapted for healthcare information systems (HIS). We began by constructing a high-level Data Flow Diagram (DFD) to represent patient journeys through healthcare facilities, from registration to follow-up care. This DFD captured the complex interactions between patients, medical staff, and various healthcare system components, including electronic health record (EHR) systems, diagnostic imaging systems, medication management platforms, vital sign monitoring devices, referral systems, remote monitoring solutions, and secure messaging infrastructure.

For each DFD element threat trees from the LINDDUN framework were then used to systematically evaluate the seven LINDDUN privacy threat categories: Linkability, Identifiability, Non-repudiation, Detectability, Data Disclosure, Unawareness, and Non-compliance. This evaluation required extensive domain expertise in both healthcare operations and privacy engineering. For example, when analysing the EHR system process node, we considered how patient data might be linked across disparate systems (Linkability), how anonymized data could be re-identified through correlation attacks (Identifiability), and how unauthorized data access might occur through various attack vectors (Data Disclosure). The evaluation produced a comprehensive threat mapping matrix that identified specific privacy vulnerabilities across all DFD elements.

This matrix served as the foundation for mapping privacy threats to corresponding Common Weakness Enumeration (CWE) categories. The mapping process was iterative and required significant manual verification using healthcare privacy and security standards and procedures. For instance, Linkability threats were mapped to vulnerabilities such as CWE-200 (Information Exposure), while Identifiability threats were associated with CWE-203 (Information Exposure Through Discrepancy). This meticulous mapping established a standardized framework for vulnerability classification that bridges privacy threats with concrete code-level weaknesses. Details of the modified approach can be found here.

3.2. Data Aggregation and Sources

The creation of a comprehensive vulnerability dataset required integration of multiple high-quality sources that provided diverse and representative vulnerability samples. We drew upon DiverseVul [

10], which contributed a wide range of vulnerability patterns across different codebases, particularly enhancing our coverage of memory safety issues prevalent in healthcare device firmware. ReposVul [

11] supplemented this with real-world vulnerability instances from repository analysis, prioritizing those found in healthcare-related projects. The StarCoder dataset [

24] provided additional context with its extensive source code collection spanning 86 programming languages, GitHub issues, Jupyter notebooks, and commit messages, yielding approximately 250 billion tokens that informed our understanding of coding patterns associated with privacy vulnerabilities.

The integration process of these feeder datasets required meticulous attention to detail, implemented through custom Python merging scripts specifically designed to handle the complexity of combining disparate vulnerability datasets. Our methodology focused exclusively on extracting C/C++ functions while preserving associated metadata fields. The initial automated integration phase employed pandas DataFrame operations with carefully crafted join conditions that maintained referential integrity between code samples and their corresponding CWE annotations. Following this automated processing, our team conducted extensive manual inspection of randomly sampled integration results, identifying edge cases where metadata conflicts or inconsistent formatting required manual handling. These insights informed the development of additional preprocessing routines that standardized field formats, resolved annotation conflicts, and verified the semantic consistency of the integrated records.

3.3. Filtering Methodology

Our filtering methodology used a multi-stage approach to ensure the relevance of the dataset to healthcare privacy concerns. The LINDDUN-CWE alignment filter derived from the modified threat methodology was applied on the aggregated dataset to retain only functions associated with privacy-relevant CWE categories. This filter was implemented as a semantic matching algorithm that compared code patterns with vulnerability signatures derived from our LINDDUN analysis. For example, functions exhibiting patterns consistent with improper anonymization techniques were flagged for retention based on their relevance to ‘Identifiability’ threats.

Identified privacy-relevant CWEs that were missing were synthesized with the OpenAI API, GPT-3.5-Turbo, representing vulnerable and non-vulnerable code functions. This synthesis process was guided by detailed prompts incorporating healthcare-specific contexts and privacy requirements. Approximately 12% of the final dataset consists of these synthetic examples, primarily addressing underrepresented privacy vulnerability categories that are particularly relevant to healthcare applications.

3.4. Dataset Structure

The final C3-VULMAP dataset comprises 30,112 vulnerable and 7,808,136 non-vulnerable C/C++ functions, covering 776 unique CWEs. This imbalance reflects the reality of software development, where vulnerable code represents a minority of implementations. The dataset structure was designed to facilitate both machine learning model training and human analysis. Each entry in the dataset consists of a code snippet at the function level, representing either a vulnerable or non-vulnerable implementation. The focus on function-level granularity was chosen after empirical evaluation of alternative granularities (line-level, block-level, file-level) for their effectiveness in capturing vulnerability contexts. Functions emerged as the optimal unit of analysis, providing sufficient context for understanding vulnerability patterns while remaining manageable for analysis. Function-level analysis aligns with typical code review and security assessment practices in healthcare software development, where functions often encapsulate specific data processing operations with clear security boundaries.

C/C++ was selected because it is considered a programming language for safety-critical systems [

25], and its manual memory management introduces unique privacy vulnerabilities like buffer overflows [

26] which align with LINDDUN categories and can cause unauthorized data exposure [

27]. In addition, C/C++ remains the dominant implementation language for performance-critical applications, including medical imaging systems, patient monitoring devices, and laboratory information systems [

28]. The manual memory management inherent to C/C++ introduces unique privacy vulnerability vectors such as buffer overflows, use-after-free errors, and memory leaks, which can lead to unauthorized data exposure [

29]. Moreso, the low-level features of C/C++, including pointer manipulation and direct memory access, expose privacy risk vectors that require systematic investigation in the healthcare context [

30]. For example, improper sanitization of patient identifiers before memory deallocation can leave residual protected health information (PHI) accessible to attackers, a vulnerability pattern well-represented in our dataset. Additionally, many healthcare systems rely on legacy C/C++ codebases designed for long-term reliability, making vulnerability detection in this language particularly valuable for maintaining privacy compliance in established healthcare infrastructure.

3.5. Feature Engineering and Metadata Schema

The dataset consists of a rich metadata schema of nine essential columns that provide multi-dimensional characterization of each vulnerability. The 'label' column contains the binary classification of vulnerable (1) or non-vulnerable (0), serving as the primary target for supervised learning models, while the 'code' column contains the actual C/C++ function implementation, preserved with consistent formatting while maintaining the semantic integrity of the original code.

For vulnerable entries, the 'cwe_id' column provides the specific Common Weakness Enumeration identifier, while 'cwe_description' offers a detailed explanation of the vulnerability type. The 'CWE-Name' column provides the standardized name of the weakness, facilitating cross-reference with external vulnerability databases and literature. Together, these fields enable precise categorization of vulnerability types and support targeted analysis of specific weakness categories.

The 'Privacy_Threat_Types' column represents a key innovation in our dataset, mapping each vulnerability to corresponding LINDDUN privacy threat categories. This mapping facilitates privacy-focused analysis by explicitly connecting code-level vulnerabilities to higher-level privacy implications. Distribution analysis reveals significant representation across privacy threat types, with Identifiability (1,128,726 instances) and Linkability (1,128,680 instances) being the most prevalent, followed by Unawareness (1,117,373), Detectability (1,117,164), Data Disclosure (1,116,341), Non-compliance (1,115,478), and Non-repudiation (1,114,486).

The hierarchical categorization of vulnerabilities is further supported by the 'CWE_CATEGORY', 'CWE_CATEGORY_NAME', and 'CWE_CATEGORY_NAME_DESCRIPTION' columns. These fields provide increasingly detailed information about the vulnerability's classification within the CWE hierarchy, enabling both broad categorical analysis and specific vulnerability targeting. The distribution of CWE categories reveals the predominance of Memory Buffer Errors (19,948 instances) and Data Neutralization Issues (4,896 instances), reflecting their critical importance in healthcare systems where data integrity and confidentiality are paramount. The comprehensive nature of this metadata schema supports diverse research applications, from training specialized models for detecting specific vulnerability types to conducting broader analyses of privacy vulnerability patterns in healthcare software. The explicit connection between code-level vulnerabilities and privacy threats through the LINDDUN framework represents a significant advancement in vulnerability dataset design, directly addressing the need for privacy-aware security analysis in healthcare applications.

4. Evaluation Methodology

4.1. Model Selection and Rationale

To assess the effectiveness of vulnerability detection using the C3-VULMAP dataset, diverse modelling approaches were selected spanning graph neural networks (GNNs), transformer-based models, and traditional machine learning (ML) techniques. Each category offers unique strengths and insights into vulnerability detection tasks, providing a foundation for comparative analysis.

4.1.1. Graph Neural Network (GNN)-Based Models

Graph neural networks ordinarily prevail at capturing structural relationships within data, making them highly suitable for representing complex dependencies within source code. Specifically, Reveal [

31] and Devign [

32] stand out as prominent GNN-based models widely recognized in vulnerability detection literature. Reveal employs a novel approach to explicitly model code semantics and structure by integrating graph-based representation learning and transforms source code into comprehensive graphs capturing data flow and control flow dependencies and thereby allowing the enriched representation to efficiently discern nuanced patterns indicative of vulnerabilities. Devign further advances this technique by combining graph convolutional networks with gated recurrent units, enabling both structural and sequential learning within code. Devign effectively addresses the shortcomings of simpler GNN models by incorporating temporal dependencies in code execution paths, significantly enhancing its capability to identify subtle vulnerability patterns across extensive codebases [

32].

4.1.2. Transformer-Based Models

Transformer architectures have transformed natural language processing tasks, demonstrating extraordinary capabilities in contextual learning and pattern recognition. Due to similarities between code and natural language, transformer-based models have become increasingly influential in code vulnerability detection. Models like CodeBERT, GraphCodeBERT, and CodeT5 exemplify this category and were selected for their proven effectiveness and innovation in leveraging large-scale contextual representations of code.

CodeBERT built on the robust RoBERTa architecture and pretrained on a large corpus of code and natural language data. Its strength lies in effectively capturing semantic relationships within code through masked language modelling and next sentence prediction tasks. This deep contextual understanding allows CodeBERT to detect vulnerabilities arising from nuanced semantic issues in source code [

33]. GraphCodeBERT extends the capabilities of CodeBERT by explicitly integrating structure-aware pretraining. It leverages abstract syntax tree (AST)-based representations alongside traditional token sequences to learn more precise structural-semantic embeddings of code. This dual-focus enables GraphCodeBERT to accurately detect vulnerabilities linked to complex structural patterns that simpler token-based models might overlook [

34]. For CodeT5, based on the T5 encoder-decoder architecture, introduces an advanced form of multitask pretraining specifically designed for programming languages. It encompasses code generation, summarization, and vulnerability detection tasks simultaneously, providing unparalleled flexibility and accuracy. Its ability to generalize across multiple tasks and contexts positions it uniquely for vulnerability detection, especially where vulnerabilities intersect with other code characteristics, such as readability or complexity [

35].

4.1.3. Traditional Machine Learning Models

Despite the popularity of deep learning methods, traditional machine learning approaches remain invaluable due to their interpretability, simplicity, and efficient training. To provide a comprehensive performance baseline, we selected classical algorithms, including Random Forest, Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machines (SVM), and XGBoost.

Random Forests excel at capturing complex, non-linear relationships through ensemble decision-tree voting, offering high predictive accuracy and robustness against overfitting. They also provide feature importance metrics, enabling insightful interpretations about influential code attributes contributing to vulnerabilities [

36]. Logistic Regression offers transparency and interpretability, ideal for baseline comparisons and situations requiring clear justifications. It allows straightforward identification of code features that significantly correlate with vulnerability risks, thereby facilitating effective feature engineering and practical vulnerability assessment strategies [

37]. Support Vector Machines (SVMs) effectively handle high-dimensional feature spaces, characteristic of code analysis datasets, by maximizing the margin of separation between vulnerability classes. Their kernel flexibility and ability to handle sparse datasets position them as valuable baseline models, particularly for evaluating the impacts of intricate feature interactions [

38]. XGBoost is popular for its enhanced predictive performance through gradient boosting, systematically correcting errors of previous weak learners to achieve exceptional accuracy. Its efficiency and scalability make it ideal for large-scale vulnerability datasets, enabling rapid model iteration and fine-tuning processes. Additionally, its feature importance capabilities further assist in detailed interpretability and vulnerability attribution analyses [

39].

4.2. Experimental Setup

A unified pipeline across was adopted for the four modelling paradigms to ensure fair and reproducible comparisons. All experiments draw on the same base corpus of labelled examples. We then partition each dataset into training, validation, and test sets—typically in an 80/10/10 split—using stratified sampling to preserve label distributions. This split underpins every downstream model, from traditional classifiers to graph neural networks (GNNs).

Our neural-text comparison centres on pre-trained Transformer encoders. We benchmarked both BERT-base (uncased) and GraphCodeBERT, loading each via AutoModelForSequenceClassification API from Hugging Face with two-class heads. Text (or code snippets) are tokenized in-batch with padding and truncation to a fixed maximum length, producing input_ids and attention_mask tensors. Fine-tuning follows the standard AdamW optimizer (learning rate ≈2×10⁻⁵) over multiple epochs, with checkpoints saved per epoch. Model outputs—the pooled [CLS] embeddings—are fed through a linear classification head, and we monitor precision, recall, and F1 on the validation set to select the best checkpoint. Under this regimen, GraphCodeBERT’s code-aware pre-training consistently outperformed vanilla BERT on code classification tasks.

In the CodeT5 experiments, we leveraged the Salesforce “codet5-base” seq2seq model repurposed for classification. After tokenizing code–docstring pairs with the CodeT5 tokenizer (padding/truncation to length 512), we fine-tuned AutoModelForSequenceClassification analogously to the BERT family. Training loops compute cross-entropy loss, back-propagate gradients, and save best models based on validation F1. Despite its encoder–decoder architecture, CodeT5 converged comparably to encoder-only models, showing strength in code summarization tasks where the decoder context aids disambiguation.

Finally, our graph-based approach converts each example into a program graph: nodes represent AST constructs or tokens, edges encode syntactic and data-flow relations, and node features comprise one-hot token-type vectors. We implemented three GNN variants—GCN, GraphSAGE, and GAT—each consisting of stacked message-passing layers, global pooling (mean or max), and an MLP classification head. Training uses standard PyTorch loops with Adam (lr ≈1×10⁻³) and cross-entropy loss. The GAT model, in particular, benefits from attention over code structure, yielding the highest F1 among graph-based models.

To evaluate performance, we ran inference on the held-out test fold for every model, compiling an “inference table” of true labels, predicted labels, and model confidences. From these, we computed accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 via Scikit-learn, alongside confusion matrices. We complemented scalar metrics with rich visualizations: bar charts for multi-model metric comparison, heatmaps of confusion matrices, boxplots of confidence distributions on correct versus incorrect predictions, and targeted error-confidence analyses highlighting high-confidence misclassifications. All figures and summary tables are saved in a structured outputs/ directory, ensuring transparency and ease of reproduction. Collectively, this cohesive framework illuminates the trade-offs between traditional, Transformer-based, generative, and graph-based approaches on code and text classification.

5. Results

This section presents the performance evaluation of three classes of models, traditional machine learning (ML), graph neural networks (GNNs), and Transformer-based models, across overall classification, production-scale inference, and granular vulnerability and privacy-threat metrics. The results are derived from a comprehensive evaluation on a validation set and a production-scale test set of 18,068 cases, with metrics including precision, recall, F1-score, accuracy, false positives/negatives, and average confidence scores. Granular performance is reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) across Common Weakness Enumeration (CWE) and privacy-threat categories, with the best-performing threat type highlighted for each model. The complete performance metrics and other results can be found in here.

5.1. Traditional Machine Learning Modules

We evaluated four traditional machine learning classifiers: Random Forest, Support Vector Machine (SVM), Logistic Regression, and XGBoost.

Table 3 presents their overall classification performance.

All four models demonstrated high effectiveness, with SVM achieving the best balance of recall (0.993) and F1-score (0.987), while Random Forest delivered the highest precision (0.985) but at the cost of lower recall. XGBoost attained the highest recall (0.995) among all models, suggesting superior sensitivity to vulnerability detection, though with slightly lower precision than the other approaches.

To assess practical deployment viability, we conducted inference testing on a production-scale dataset comprising 18,068 cases.

Table 4 summarizes these results.

SVM demonstrated the highest overall accuracy (0.987) with a balanced error profile, producing only 60 false negatives but 169 false positives. XGBoost showed a tendency toward false positives (205) while minimizing false negatives (49), indicating a more conservative security posture that favours vulnerability flagging. Random Forest exhibited the most false negatives (553), suggesting potential security risks in deployment scenarios where missed vulnerabilities could be costly.

We further analysed model consistency across vulnerability categories by computing mean and standard deviation of performance metrics for Common Weakness Enumeration (CWE) classes (

Table 5).

Both SVM and XGBoost achieved the highest mean F1-scores (0.987 ± 0.005 and 0.988 ± 0.004, respectively) with minimal variability across CWE classes, indicating robust performance regardless of vulnerability type. Random Forest showed slightly higher variability (σ = 0.011), suggesting less consistent performance across different vulnerability classes.

Finally, we evaluated model performance on privacy threat classification (

Table 6).

SVM again emerged as the top performer with an average F1-score of 0.9873 across privacy threat categories, with particularly strong performance on Linkability threats (F1 = 0.9893). Interestingly, XGBoost matched this best-in-class performance (F1 = 0.9893) but on Identifiability threats, suggesting that different models may possess complementary strengths for specific privacy threat detection tasks.

5.2. Graph Neural Networks

Our evaluation included two state-of-the-art graph neural network architectures: Devign and Reveal.

Table 7 presents their overall classification performance.

Both GNN models achieved exceptional recall (>0.99), with Reveal outperforming Devign across all metrics. Reveal's superior precision (0.9821 vs. 0.9699) contributed to its higher F1-score (0.9860), indicating better overall classification performance.

For production deployment assessment, we conducted large-scale inference testing with results shown in

Table 8.

Reveal demonstrated higher accuracy (0.9933) with considerably fewer false positives (74 vs. 103) compared to Devign, while both models produced identical false negative counts (27). Notably, both GNN models exhibited lower average confidence scores (≈0.50) than traditional ML models, suggesting more conservative decision boundaries despite their higher performance metrics.

To assess model consistency across vulnerability categories, we analysed performance variance across CWE classes (

Table 9).

Both GNN models achieved nearly identical category-level performance with excellent mean recall (0.997) and F1-scores (0.991). The slightly higher standard deviations in precision (σ ≈ 0.017-0.018) suggest that both models experience some variability across different CWE classes, though this does not significantly impact overall robustness.

For privacy-threat metrics, we evaluated performance consistency and identified peak performance areas (

Table 10).

Reveal achieved higher mean precision (0.990 vs. 0.986) and F1-score (0.993 vs. 0.991) than Devign, with both models maintaining exceptionally high recall (0.996). The minimal standard deviations across all metrics (σ ≤ 0.005) indicate remarkable consistency across privacy threat types. Interestingly, the models demonstrated complementary strengths, with Devign excelling at Identifiability detection (F1 = 0.9945) and Reveal performing best on Linkability threats (F1 = 0.9968).

To provide a more comprehensive view of privacy-threat classification performance, we present average metrics and best-case performance for each model in

Table 11.

Reveal consistently outperformed Devign across all average metrics, with particularly strong performance in precision (0.9902 vs. 0.9860) and F1-score (0.9931 vs. 0.9910). Both models achieved near-perfect recall (>0.996), highlighting their exceptional sensitivity to privacy vulnerabilities. The complementary specialization patterns observed earlier were confirmed, with Devign excelling at Identifiability threats and Reveal demonstrating superior performance on Linkability threats.

5.3. Transformer-Based Models

We evaluated five transformer-based models: BERT, RoBERTa, CodeBERT, CodeT5-base, and CodeT5-small.

Table 12 presents their overall classification performance.

All transformer models demonstrated exceptional performance, with F1-scores exceeding 0.98. RoBERTa emerged as the top performer with the highest precision (0.980), recall (0.994), and F1-score (0.987) among transformer models. CodeBERT ranked second with an F1-score of 0.985, while CodeT5-small showed the lowest overall performance but still achieved an impressive F1-score of 0.981.

For production deployment assessment,

Table 13 presents inference performance metrics.

RoBERTa achieved the highest accuracy (0.9932) with the fewest false positives (60) and false negatives (25), confirming its superior performance in practical deployment scenarios. All transformer models exhibited high confidence scores (>0.89), with RoBERTa again leading at 0.925. CodeT5-small showed the weakest production performance with the most false positives (102) and false negatives (45), consistent with its lower overall metrics.

To assess consistency across vulnerability categories, we analysed performance across CWE classes (

Table 14).

All transformer models demonstrated consistent performance across CWE classes with low standard deviations (σF1 ≤ 0.009). RoBERTa again led with the highest mean F1-score (0.987) and smallest performance variability (σF1 = 0.006), indicating robust performance across all vulnerability types. CodeT5-small showed the highest variability (σF1 = 0.009), though still maintaining strong overall performance.

For privacy-threat classification, we assessed fine-grained metrics across threat types (

Table 15).

All transformer models achieved exceptional performance on privacy threat classification, with mean F1-scores ≥ 0.989 and minimal standard deviations (σF1 ≤ 0.006). RoBERTa maintained its leading position with the highest mean F1-score (0.991), followed closely by CodeBERT and CodeT5-base (both 0.990). The consistently high recall across all models (≥ 0.994) highlights their strong sensitivity to privacy vulnerabilities.

Finally, we identified the best-performing privacy threat type for each transformer model (

Table 16).

Interestingly, different transformer models demonstrated specialized strengths for specific privacy threat types. RoBERTa excelled at Linkability detection (F1 = 0.9962), while CodeT5-small achieved its best performance on Data Disclosure threats (F1 = 0.9961) despite having lower overall metrics. BERT and CodeT5-base both performed best on Identifiability threats with identical F1-scores (0.9946). This specialization pattern suggests potential benefits from ensemble approaches that leverage the complementary strengths of different models.

6. Discussion

Comparing GNN-based, transformer-based, and traditional ML models reveals major differences in their capacities for vulnerability detection. For instance, the GNN-based models we used, Reveal and Devign, leverage graph structures to accurately capture complex dependencies in codebases. Reveal consistently demonstrated superior performance, achieving precision and recall close to 0.99, outperforming Devign due to its nuanced integration of data flow and control flow dependencies. Devign, while slightly behind, still provided substantial insights by combining graph convolutional networks with gated recurrent units, effectively capturing sequential and structural patterns essential for identifying subtle vulnerabilities [

32]. In contrast, the transformer-based models, RoBERTa, CodeBERT, and CodeT5 displayed superb contextual learning capabilities, largely due to their extensive pretraining on code and natural language corpora. RoBERTa achieved the highest precision and recall, indicating its profound ability to capture subtle semantic issues within code. CodeBERT and CodeT5, while slightly lower in overall performance, provided multitask flexibility, important for broader software analysis tasks, suggesting the suitability of transformer-based models for complex, multifaceted vulnerability detection contexts [

33,

34].

The traditional ML models performed effectively as a baseline, revealing high efficiency and interpretability. Among these, SVM and XGBoost performed better in exhibiting outstanding recall and precision. SVM presented a balanced performance, minimizing false negatives, crucial for critical healthcare environments where missing a vulnerability might lead to severe consequences. XGBoost, despite a slight inclination towards false positives, demonstrated exceptional predictive capabilities, emphasizing its relevance in scenarios prioritizing comprehensive threat detection over strict accuracy. Random Forest and Logistic Regression, while reliable, highlighted limitations in managing false negatives, underscoring the importance of choosing appropriate models based on the specific operational priorities within healthcare IT infrastructures [

36].

Interestingly, our analysis revealed that vulnerability types with direct privacy implications exhibited varying degrees of detection difficulty. Information disclosure vulnerabilities were detected with high accuracy across all models, while more subtle privacy issues related to insufficient anonymization or improper access control required more sophisticated model architectures, particularly GNNs and transformers with architectural components tailored to structural code understanding. This finding aligns with recent research suggesting that privacy vulnerabilities often involve complex interactions between code structure, data flow, and application semantics that can be challenging to detect with simple pattern matching [40] All the models tested showed strong effectiveness in identifying privacy-specific vulnerabilities, although distinct variations existed in their accuracy across different privacy threats. Transformer-based models, notably RoBERTa, consistently demonstrated superior performance across different privacy threats, particularly in Linkability and Identifiability, which is likely because of their nuanced semantic understanding derived from vast pretraining. Reveal, within the GNN category, particularly excelled in identifying Linkability threats, leveraging its structural sensitivity to intricate privacy issues deeply embedded within code dependencies. This specificity underscores the value of employing specialized models tailored to distinct privacy threats rather than generalized vulnerability detectors, especially within sensitive healthcare contexts.

Furthermore, the performance patterns observed across different CWE categories were instructive for targeted vulnerability detection strategies. Memory buffer errors, representing the largest vulnerability category in our dataset (19,948 instances), were consistently detected with great accuracy across all model types, reflecting the relatively structured nature of these vulnerabilities. In contrast, data neutralization issues (4,896 instances) exhibited greater variability in detection performance, likely due to their context-dependent manifestation and the diverse implementation patterns for data sanitization in healthcare applications [

38].

The targeted construction of C3-VULMAP, specifically integrating healthcare-focused vulnerability scenarios, provided superior generalization within healthcare software contexts compared to generic datasets. The combination of real-world vulnerabilities with synthetic examples significantly bolstered the ability of the dataset to train models capable of generalizing across diverse privacy threats, thus achieving robust state-of-the-art results in healthcare privacy vulnerability detection. The integration of the LINDDUN framework with CWE profoundly impacted vulnerability detection by providing a structured and explicit mapping between privacy threats and specific vulnerabilities at the code level. This integration facilitates deeper interpretability, enabling stakeholders to understand not only what vulnerabilities exist but their potential privacy implications. Such detailed mappings bridge the gap between abstract privacy concepts and concrete software vulnerabilities, significantly enhancing the capability to mitigate privacy risks proactively in healthcare environments. Moreover, it supports compliance-driven development, guiding software engineers towards more privacy-aware coding practices, fundamentally transforming how software vulnerabilities are managed and prioritized in healthcare systems.

When interpreting our results in the broader context of healthcare software privacy, several key implications emerge. The high accuracy achieved by our models demonstrates the feasibility of automated privacy vulnerability detection as part of healthcare software development pipelines, potentially accelerating compliance verification for regulations. However, the observed specialization of different models for specific privacy threat types suggests that comprehensive privacy assurance requires multi-faceted detection approaches rather than reliance on a single model architecture. Additionally, the integration of privacy threat modelling with concrete vulnerability detection bridges the gap between privacy engineering and security engineering disciplines, addressing the historical disconnect between these domains that has challenged healthcare software development [

35].

Nevertheless, our approach is not devoid of challenges worth considering. For instance, the labelling of C/C++ functions for privacy vulnerabilities required significant domain expertise in both healthcare operations and privacy engineering. Also, the adaptation of the LINDDUN methodology to code-level vulnerabilities presented conceptual challenges, as privacy threats often manifest across multiple functions or components rather than within isolated code segments [

11]. Additionally, the class imbalance inherent in vulnerability datasets (30,112 vulnerable vs. 7,808,136 non-vulnerable functions) necessitated careful sampling and evaluation approaches to ensure model robustness in production environments.

The comparative analysis between GNN-based, transformer-based, and traditional ML models highlights significant differences in their capacities for vulnerability detection. GNN-based models, particularly Reveal and Devign, leverage graph structures to accurately capture complex dependencies in codebases. Reveal consistently demonstrated superior performance, achieving precision and recall close to 0.99, outperforming Devign due to its nuanced integration of data flow and control flow dependencies. Devign, while slightly behind, still provided substantial insights by combining graph convolutional networks with gated recurrent units, effectively capturing sequential and structural patterns essential for identifying subtle vulnerabilities [

13]. In contrast, transformer-based models such as RoBERTa, CodeBERT, and CodeT5 displayed outstanding contextual learning capabilities, largely due to their extensive pretraining on code and natural language corpora. RoBERTa achieved the highest precision and recall, indicating its profound ability to capture subtle semantic issues within code. CodeBERT and CodeT5, while slightly lower in overall performance, provided multitask flexibility, crucial for broader software analysis tasks, suggesting the suitability of transformer-based models for complex, multifaceted vulnerability detection contexts [

33,

34].

Traditional ML models served effectively as a baseline, revealing high efficiency and interpretability. Among these, SVM and XGBoost notably excelled, exhibiting outstanding recall and precision. SVM presented a balanced performance, minimizing false negatives, crucial for critical healthcare environments where missing a vulnerability might lead to severe consequences. XGBoost, despite a slight inclination towards false positives, demonstrated exceptional predictive capabilities, emphasizing its relevance in scenarios prioritizing comprehensive threat detection over strict accuracy. Random Forest and Logistic Regression, while reliable, highlighted limitations in managing false negatives, underscoring the importance of choosing appropriate models based on the specific operational priorities within healthcare IT infrastructures [

36,

39].

All tested models showed strong effectiveness in identifying privacy-specific vulnerabilities, although distinct variations existed in their accuracy across different privacy threats. Transformer-based models, notably RoBERTa, consistently demonstrated superior performance across diverse privacy threats, particularly in Linkability and Identifiability, likely due to their nuanced semantic understanding derived from vast pretraining. Reveal, within the GNN category, particularly excelled in identifying Linkability threats, leveraging its structural sensitivity to intricate privacy issues deeply embedded within code dependencies. This specificity underscores the value of employing specialized models tailored to distinct privacy threats rather than generalized vulnerability detectors, especially within sensitive healthcare contexts [

35].

Generalization performance is particularly critical in real-world applications. The evaluated models, trained on the C3-VULMAP dataset, indicated substantial advancement over traditional datasets like DiverseVul and ReposVul. The targeted construction of C3-VULMAP, specifically integrating healthcare-focused vulnerability scenarios, provided superior generalization within healthcare software contexts compared to generic datasets. The combination of real-world vulnerabilities with synthetic examples significantly bolstered the dataset's ability to train models capable of generalizing across diverse privacy threats, thus achieving robust state-of-the-art results in healthcare privacy vulnerability detection.

Interpreting these results within healthcare software privacy contexts highlights the necessity of high-performing detection systems capable of pinpointing nuanced vulnerabilities critical to patient data integrity and compliance with healthcare regulations. The remarkable performance of transformer-based and GNN models emphasizes their applicability in healthcare, given their precision in capturing both semantic and structural vulnerabilities. Privacy-specific threats such as Linkability and Identifiability require meticulous detection mechanisms, aligning closely with healthcare’s stringent privacy regulations like HIPAA and GDPR. Therefore, employing advanced detection models becomes not merely a technical preference but a regulatory imperative for healthcare organizations aiming to protect sensitive patient data comprehensively.

The integration of the LINDDUN framework with CWE profoundly impacted vulnerability detection by providing a structured and explicit mapping between privacy threats and specific vulnerabilities at the code level. This integration facilitates deeper interpretability, enabling stakeholders to understand not only what vulnerabilities exist but their potential privacy implications. Such detailed mappings bridge the gap between abstract privacy concepts and concrete software vulnerabilities, significantly enhancing the capability to mitigate privacy risks proactively in healthcare environments. Moreover, it supports compliance-driven development, guiding software engineers towards more privacy-aware coding practices, fundamentally transforming how software vulnerabilities are managed and prioritized in healthcare systems [

26].

7. Conclusion

The significance of privacy-aware vulnerability detection cannot be overstated, particularly in healthcare contexts where privacy breaches can have profound implications on patient safety and compliance with strict regulatory frameworks. The C3-VULMAP dataset substantially advances the field by explicitly integrating the LINDDUN privacy framework with CWE vulnerability classifications, creating a unique and valuable resource tailored to healthcare privacy concerns. Its combination of real-world and synthetic examples provides balanced and comprehensive vulnerability representation, facilitating superior model training and generalization capabilities.

Given these strengths, further use and collaborative enhancements of the C3-VULMAP dataset are strongly encouraged. Researchers, practitioners, and policymakers in cybersecurity and healthcare are invited to engage with and contribute to this evolving resource, promoting broader adoption and continuous improvement in privacy vulnerability detection methodologies.

Practical implications from this study highlight considerable challenges and critical considerations in labelling and detecting vulnerabilities. One notable challenge is ensuring accurate manual labelling, which remains essential despite advancements in automated detection methodologies. The reliance on domain expertise for manual labelling poses significant resource implications, highlighting the reliance on human oversight to validate automated findings. The integration of synthetic vulnerabilities, although beneficial, also presents challenges related to ensuring their realism and representativeness. Practical deployment further demands addressing issues such as managing false positives, refining confidence thresholds, and ensuring that detected vulnerabilities are actionable and relevant, thus necessitating ongoing iterative improvements and adaptations to maintain robust and accurate vulnerability detection in dynamic healthcare environments.

Expansion to additional programming languages is another important direction, as the current dataset predominantly focuses on C/C++ due to their prevalent use in safety-critical applications like those used in healthcare. Incorporating other widely used languages like Python, Java, and JavaScript would broaden the applicability of the dataset, providing comprehensive coverage across diverse healthcare systems and software environments. Additionally, exploring real-time vulnerability detection systems represents a promising avenue. Implementing continuous, real-time detection mechanisms would enhance proactive privacy protection capabilities in dynamic healthcare infrastructures, addressing vulnerabilities immediately as they emerge, thus substantially reducing associated risks and impacts.

Author Contributions

J.E. Ameh led the conceptualization, dataset construction, model implementation, and manuscript drafting. A. Otebolaku contributed to the methodological framework, evaluation design, and critical revisions of the manuscript. A. Shenfield supervised the experimental validation, data interpretation, and provided technical oversight throughout the study. A. Ikpehai supported the integration of privacy frameworks, ensured alignment with healthcare cybersecurity standards, and reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Please add: “This research received no external funding”.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

“During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used ChatGPT and Claude for the purposes of python script enhancement. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.”.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no known conflict of interest.

References

- Mejía-Granda, C.M.; Fernández-Alemán, J.L.; Carrillo-de-Gea, J.M.; et al. Security vulnerabilities in healthcare: An analysis of medical devices and software. Medical & Biological Engineering & Computing 2024, 62, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protić, D.D. Review of KDD Cup ’99, NSL-KDD and Kyoto 2006+ datasets. Vojnotehnički Glasnik 2017, 66, 580–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, R.; Nagpal, R. A review on KDD Cup ’99 and NSL-KDD dataset. International Journal of Advanced Research in Computer Science 2019, 10, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harzevili, N.S.; Belle, A.B.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Jiang ZM, J.; Nagappan, N. A systematic literature review on automated software vulnerability detection using machine learning. ACM Computing Surveys 2024, 57, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, M.; Falessi, D. VALIDATE: A deep dive into vulnerability prediction datasets. Information and Software Technology 2024, 170, 107448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Zaabi, M.; Alhashmi, S.M. Big data security and privacy in healthcare: A systematic review and future research directions. Journal of Information Science 2024, 50, 1247781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almarimi, A.; Alsaleh, M. Vulnerability to Cyberattacks and Sociotechnical Solutions for Health Care Systems: Systematic Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2024, 26, e46904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.W.; et al. Balancing Privacy and Progress: A Review of Privacy Challenges, Systemic Oversight, and Patient Perceptions in AI-Driven Healthcare. Applied Sciences 2023, 14, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Nguyen, T.N. (2020). A C/C++ code vulnerability dataset with code changes and CVE summaries. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Mining Software Repositories (MSR 2020) (pp. 508–512). Association for Computing Machinery. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ding, Z.; Alowain, L.; Chen, X.; Wagner, D. (2023). DiverseVul: A new vulnerable source code dataset for deep learning based vulnerability detection. In Proceedings of the 26th International Symposium on Research in Attacks, Intrusions and Defenses (RAID ’23) (pp. 1–15). ACM. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Hu, R.; Gao, C.; Wen, X.-C.; Chen, Y.; Liao, Q. (2024). ReposVul: A repository-level high-quality vulnerability dataset. In Proceedings of the 46th International Conference on Software Engineering: Companion Proceedings (ICSE-Companion ’24) (pp. 472–483). Association for Computing Machinery. [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, G.; Naseer, A.; Moonen, L. (2021). CVEfixes: Automated collection of vulnerabilities and their fixes from open-source software. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Predictive Models and Data Analytics in Software Engineering (PROMISE ’21) (pp. 30–39). Association for Computing Machinery. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Bettaieb, S.; Casino, F. A comprehensive analysis on software vulnerability detection datasets: trends, challenges, and road ahead. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2024, 23, 3311–3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A.; Herrera, L.-C.; Donoso, Y.; Gutierrez, J.A. Survey on intrusion detection systems based on machine learning techniques for the protection of critical infrastructure. Sensors 2023, 23, 2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sion, L.; Wuyts, K.; Yskout, K.; Van Landuyt, D.; Joosen, W. (2018). Interaction-based privacy threat elicitation. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy Workshops (EuroS&PW) (pp. 79–86). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Wuyts, K.; Sion, L.; Joosen, W. (2020). LINDDUN GO: A lightweight approach to privacy threat modeling. In 2020 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy Workshops (EuroS&PW) (pp. 302–309). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Naik, N.; Jenkins, P.; Grace, P.; Naik, D.; Prajapat, S.; Song, J. (2024). A Comparative Analysis of Threat Modelling Methods: STRIDE, DREAD, VAST, PASTA, OCTAVE, and LINDDUN. In: Naik, N., Jenkins, P., Prajapat, S., Grace, P. (eds) Contributions Presented at The International Conference on Computing, Communication, Cybersecurity and AI, July 3–4, 2024, London, UK. C3AI 2024. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol 884. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Langthaler, O.; Eibl, G.; Klüver, L.-K.; Unterweger, A. (2025). Evaluating the efficacy of LINDDUN GO for privacy threat modeling for local renewable energy communities. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP 2025) (Vol. 2, pp. 518–525). SciTePress. [CrossRef]

- Sion, L.; Van Landuyt, D.; Wuyts, K.; Joosen, W. Robust and reusable LINDDUN privacy threat knowledge. Computers & Security 2025, 154, 104419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raciti, M.; Bella, G., "A Threat Model for Soft Privacy on Smart Cars," 2023 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy Workshops (EuroS&PW), Delft, Netherlands, 2023, pp. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Nweke, L.O.; Abomhara, M.; Yildirim Yayilgan, S.; Camparin, D.; Heurtier, O.; Bunney, C. (2022). A LINDDUN-based privacy threat modelling for national identification systems. In 2022 IEEE Nigeria 4th International Conference on Disruptive Technologies for Sustainable Development (NIGERCON) (pp. 1–6). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Kunz, I.; Xu, S. (2023). Privacy as an architectural quality: A definition and an architectural view. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy Workshops (EuroS&PW) (pp. 125–132). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Wuyts, K.; Scandariato, R.; Joosen, W. Empirical evaluation of a privacy-focused threat modeling methodology. Journal of Systems and Software 2014, 96, 122–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Ben Allal, L.; Zi, Y.; Muennighoff, N.; Kocetkov, D.; Mou, C.; Marone, M.; Akiki, C.; Li, J.; Chim, J.; Liu, Q.; Zheltonozhskii, E.; Zhuo, T.Y.; Wang, T.; Dehaene, O.; Davaadorj, M.; Lamy-Poirier, J.; Monteiro, J.; Shliazhko, O., … de Vries, H. (2023). StarCoder: May the source be with you! Transactions on Machine Learning Research. [CrossRef]

- Zouev, E. (2020). Programming Languages for Safety-Critical Systems. In: Software Design for Resilient Computer Systems. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.D.; Ivaki, N.; Vieira, M. Characterizing buffer overflow vulnerabilities in large C/C++ projects. IEEE Access, 2021; 9, 142879–142892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, C.; Wang, J.; Yang, A.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Hua, D. Review on security of Federated Learning and its application in Healthcare. Future Generation Computer Systems 2023, 144, 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponggawa, V.V.; Santoso, U.B.; Talib, G.A.; Lamia, M.A.; Manuputty, A.R.; Yusuf, M.F. Comparative Study of C++ and C# Programming Languages. Jurnal Syntax Admiration 2024, 5, 5743–5748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma X.; Yan, J.; Wang, W.; Yan, J.; Zhang, J.; Qiu, Z. (2021) "Detecting Memory-Related Bugs by Tracking Heap Memory Management of C++ Smart Pointers," 2021 36th IEEE/ACM International Conference on Automated Software Engineering (ASE), Melbourne, Australia, 2021, pp. 880-891. [CrossRef]

- Rassokhin, D. The C++ programming language in cheminformatics and computational chemistry. J Cheminform 2020, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganz, T.; Härterich, M.; Warnecke, A.; Rieck, K. (2021). Explaining graph neural networks for vulnerability discovery. In Proceedings of the 14th ACM Workshop on Artificial Intelligence and Security (AISec ’21) (pp. 145–156). Association for Computing Machinery. [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Fang, Y.; Huang, C.; Ou, H.; Lin, C.; Guo, Y. HyVulDect: A hybrid semantic vulnerability mining system based on graph neural network. Computers & Security, 2022; 121, 102823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Shao, H.; Deng, X. (2024). VulCoBERT: A CodeBERT–based system for source code vulnerability detection. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Generative Artificial Intelligence and Information Security (GAIIS 2024) (pp. 249–252). Association for Computing Machinery. [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Wang, Y.; Xu, H.; Sun, J.; Zhang, F.; Li, P.; Guo, Z. (2024). Vul-LMGNNs: Fusing language models and online-distilled graph neural networks for code vulnerability detection (arXiv:2404.14719) [Preprint]. arXiv, arXiv:2404.14719) [Preprint]. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Kalouptsoglou, I.; Siavvas, M.; Ampatzoglou, A.; Kehagias, D.; Chatzigeorgiou, A. (2024). Vulnerability prediction using pre-trained models: An empirical evaluation. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Modeling, Analysis and Simulation of Computer and Telecommunication Systems (MASCOTS) (pp. 1–6). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Choubisa, M.; Doshi, R.; Khatri, N.; Hiran, K.K. (2022). A simple and robust approach of random forest for intrusion detection system in cyber security. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on IoT and Blockchain Technology (ICIBT) (pp. 1–5). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Meng, N.; Nagy, S.; Yao, D.; Zhuang, W.; Arango-Argoty, G. (2018). Secure coding practices in Java: Challenges and vulnerabilities. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE ’18) (pp. 372–383). Association for Computing Machinery. [CrossRef]

- Altamimi, S. (2022). Investigating and mitigating the role of neutralisation techniques on information security policies violation in healthcare organisations (Doctoral dissertation, University of Glasgow). [CrossRef]

- Babu, M.; Suryanarayana Reddy, N.R.; Moharir, M. & Mohana. (2024, November). Leveraging XGBoost machine learning algorithm for Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) exploitability classification. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Computational System and Information Technology for Sustainable Solutions (CSITSS 2024) (pp. 1–6). IEEE. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Comparing Some Available Healthcare Domain Specific Datasets.

Table 1.

Comparing Some Available Healthcare Domain Specific Datasets.

| Dataset |

Healthcare Focus |

Privacy-Specific Mappings |

Correlation with LINDDUN/CWE |

Model

Evaluations |

| NVD |

Partial |

No |

No |

Limited |

| KDD-Cup'99/NSL-KDD |

No |

No |

No |

General |

| C3-VULMAP |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Comprehensive |

Table 2.

Comparative Summary of Existing Vulnerability Datasets.

Table 2.

Comparative Summary of Existing Vulnerability Datasets.

| Dataset |

Vulnerabilities |

Strengths |

Limitations |

Programming

Languages |

| Big-Vul |

3,754 |

Detailed CVE summaries, severity scores |

Limited privacy applicability |

C/C++ |

| DiverseVul |

18,945 |

Diversity of real-world vulnerabilities |

No integration of privacy frameworks |

C/C++, Python |

| ReposVul |

6,134 |

Repository-level, untangled labelling |

No explicit privacy threat modelling |

C, C++, Java, Python |

| CVEfixes |

5,365 |

Predictive modelling, automated repairs |

Lack of privacy-specific considerations |

Multiple languages (C, Java) |

Table 3.

Overall performance of traditional ML models.

Table 3.

Overall performance of traditional ML models.

| Model |

Precision |

Recall |

F1-score |

| Random Forest |

0.985 |

0.939 |

0.961 |

| SVM |

0.982 |

0.993 |

0.987 |

| Logistic Regression |

0.985 |

0.979 |

0.982 |

| XGBoost |

0.978 |

0.995 |

0.986 |

Table 4.

Inference performance summary.

Table 4.

Inference performance summary.

| Model |

Accuracy |

False

Positives |

False

Negatives |

Avg

Confidence |

| Random Forest |

0.962 |

129 |

553 |

0.827 |

| SVM |

0.987 |

169 |

60 |

0.982 |

| Logistic Regression |

0.982 |

132 |

192 |

0.966 |

| XGBoost |

0.986 |

205 |

49 |

0.978 |

Table 5.

Mean ± SD of CWE granular metrics.

Table 5.

Mean ± SD of CWE granular metrics.

| Model |

Precision (μ ± σ) |

Recall (μ ± σ) |

F1 (μ ± σ) |

| Random Forest |

0.965 ± 0.012 |

0.964 ± 0.011 |

0.964 ± 0.011 |

| SVM |

0.988 ± 0.005 |

0.987 ± 0.006 |

0.987 ± 0.005 |

| Logistic Regression |

0.982 ± 0.007 |

0.982 ± 0.008 |

0.982 ± 0.007 |

| XGBoost |

0.988 ± 0.004 |

0.988 ± 0.005 |

0.988 ± 0.004 |

Table 6.

Average privacy-threat metrics and best-performing threat type per model.

Table 6.

Average privacy-threat metrics and best-performing threat type per model.

| Model |

Avg

Precision |

Avg Recall |

Avg F1 Score |

Best Threat Type |

F1 Score |

| Random Forest |

0.9632 |

0.9622 |

0.9625 |

Linkability |

0.9679 |

| SVM |

0.9874 |

0.9873 |

0.9873 |

Linkability |

0.9893 |

| Logistic Regression |

0.9821 |

0.9820 |

0.9820 |

Identifiability |

0.9852 |

| XGBoost |

0.9861 |

0.9859 |

0.9859 |

Identifiability |

0.9893 |

Table 7.

Overall performance of GNN classifiers.

Table 7.

Overall performance of GNN classifiers.

| Model |

Precision |

Recall |

F1-score |

| Devign |

0.9699 |

0.9912 |

0.9776 |

| Reveal |

0.9821 |

0.9945 |

0.9860 |

Table 8.

Production inference performance.

Table 8.

Production inference performance.

| Model |

Accuracy |

False Positives |

False Negatives |

Avg Confidence |

| Devign |

0.9913 |

103 |

27 |

0.503 |

| Reveal |

0.9933 |

74 |

27 |

0.502 |

Table 9.

Mean ± SD of CWE granular metrics.

Table 9.

Mean ± SD of CWE granular metrics.

| Model |

Precision (μ ± σ) |

Recall (μ ± σ) |

F1 (μ ± σ) |

| Devign |

0.984 ± 0.017 |

0.997 ± 0.004 |

0.991 ± 0.009 |

| Reveal |

0.986 ± 0.018 |

0.997 ± 0.004 |

0.991 ± 0.009 |

Table 10.

Mean ± SD of privacy-threat metrics, plus best-scoring threat.

Table 10.

Mean ± SD of privacy-threat metrics, plus best-scoring threat.

| Model |

Precision (μ ± σ) |

Recall (μ ± σ) |

F1 (μ ± σ) |

Best Threat Type |

F1 |

| Devign |

0.986 ± 0.005 |

0.996 ± 0.002 |

0.991 ± 0.002 |

Identifiability |

0.9945 |

| Reveal |

0.990 ± 0.005 |

0.996 ± 0.002 |

0.993 ± 0.003 |

Linkability |

0.9968 |

Table 11.

Average privacy-threat metrics and best-performing threat type per model.

Table 11.

Average privacy-threat metrics and best-performing threat type per model.

| Model |

Avg Precision |

Avg Recall |

Avg F1 Score |

Best Threat Type |

F1 Score |

| Devign |

0.9860 |

0.9962 |

0.9910 |

Identifiability |

0.9945 |

| Reveal |

0.9902 |

0.9964 |

0.9931 |

Linkability |

0.9968 |

Table 12.

Overall performance of Transformer models.

Table 12.

Overall performance of Transformer models.

| Model |

Precision |

Recall |

F1-score |

| BERT (bert-base-uncased) |

0.974 |

0.992 |

0.983 |

| RoBERTa (roberta-base) |

0.980 |

0.994 |

0.987 |

| CodeBERT (codebert-base) |

0.978 |

0.993 |

0.985 |

| CodeT5-base |

0.976 |

0.991 |

0.983 |

| CodeT5-small |

0.972 |

0.990 |

0.981 |

Table 13.

Production inference performance.

Table 13.

Production inference performance.

| Model |

Accuracy |

False Positives |

False Negatives |

Avg Confidence |

| BERT (bert-base-uncased) |

0.9915 |

85 |

30 |

0.912 |

| RoBERTa (roberta-base) |

0.9932 |

60 |

25 |

0.925 |

| CodeBERT (codebert-base) |

0.9928 |

70 |

28 |

0.918 |

| CodeT5-base |

0.9921 |

75 |

32 |

0.908 |

| CodeT5-small |

0.9905 |

102 |

45 |

0.890 |

Table 14.

Mean ± SD of CWE granular metrics.

Table 14.

Mean ± SD of CWE granular metrics.

| Model |

Precision (μ ± σ) |

Recall (μ ± σ) |

F1 (μ ± σ) |

| BERT (bert-base-uncased) |

0.975 ± 0.010 |

0.993 ± 0.005 |

0.984 ± 0.007 |

| RoBERTa (roberta-base) |

0.981 ± 0.008 |

0.994 ± 0.004 |

0.987 ± 0.006 |

| CodeBERT (codebert-base) |

0.979 ± 0.009 |

0.993 ± 0.005 |

0.986 ± 0.006 |

| CodeT5-base |

0.977 ± 0.011 |

0.991 ± 0.005 |

0.983 ± 0.008 |

| CodeT5-small |

0.973 ± 0.013 |

0.990 ± 0.006 |

0.981 ± 0.009 |

Table 15.

Mean ± SD of privacy-threat granular metrics.

Table 15.

Mean ± SD of privacy-threat granular metrics.

| Model |

Precision (μ ± σ) |

Recall (μ ± σ) |

F1 (μ ± σ) |

| BERT (bert-base-uncased) |

0.983 ± 0.006 |

0.995 ± 0.003 |

0.989 ± 0.004 |

| RoBERTa (roberta-base) |

0.987 ± 0.005 |

0.996 ± 0.003 |

0.991 ± 0.004 |

| CodeBERT (codebert-base) |

0.985 ± 0.006 |

0.995 ± 0.003 |

0.990 ± 0.005 |

| CodeT5-base |

0.986 ± 0.007 |

0.995 ± 0.003 |

0.990 ± 0.005 |

| CodeT5-small |

0.984 ± 0.008 |

0.994 ± 0.004 |

0.989 ± 0.006 |

Table 16.

Best-performing privacy threat per model.

Table 16.

Best-performing privacy threat per model.

| Model |

Best Threat Type |

F1 Score |

| BERT (bert-base-uncased) |

Identifiability |

0.9946 |

| RoBERTa (roberta-base) |

Linkability |

0.9962 |

| CodeBERT (codebert-base) |

Data Disclosure |

0.9958 |

| CodeT5-base |

Identifiability |

0.9946 |

| CodeT5-small |

Data Disclosure |

0.9961 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).