1. Introduction

The lung is a dynamic organ that continuously interacts with the environmental air introduced through processes of compression and expansion [

1]. This activity, combined with constant exposure to environmental pollutants, predispose it to diseases such as pulmonary fibrosis (PF) [

2]. PF is a progressive disease characterized by excessive deposition of a collagen-rich extracellular matrix by fibroblasts, leading to irreversible scarring and impaired oxygen exchange in the alveoli [

3,

4]. PF often results from a diverse group of conditions collectively known as diffuse parenchymal lung diseases or interstitial lung diseases, which can progress to fibrosis in chronic cases. These conditions include silicosis, asbestosis, and drug- and radiation- induced lung diseases. Others include granulomatous disease such as sarcoidosis and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), the cause of which remains unknown [

5,

6].

Given the role of pulmonary surfactant in maintaining alveolar stability, alterations in its composition may have profound implications for diseases such as PF. Pulmonary surfactant, a complex mixture synthesized, stored, and recycled by type II alveolar cells, plays a critical role in maintaining lung function [

7,

8]. PS is composed of 10% specific proteins such as SP-A, SP-B, SP-C, and SP-D and 90% lipids, which are primarily phosphoglycerides, cholesterol, and neutral lipids [

9,

10]. The main function of PS is to reduce the surface tension in the alveoli, which minimizes the work of breathing and prevents alveolar collapse during expiration [

11]. Alterations in the composition or deficiency of pulmonary surfactant have been associated with major lung diseases, including neonatal respiratory distress syndrome, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and IPF [

12,

13].

Recent studies suggest that pulmonary surfactant components, particularly PE, may modulate fibroblast behaviour and halt the fibrotic process before PF develops. For instance, Beractant, a pulmonary surfactant formulation, was shown to induce apoptosis in normal human fibroblasts (NHLF), decreased collagen expression, and triggers calcium signaling, an effect associated with antifibrotic properties [

14]. In contrast, SP-A increased collagen expression without affecting collagenase-1 or tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1. Interestingly, when Beractant was combined with SP-A, the anti-fibrotic effects of were partially reversed. These findings suggest that pulmonary surfactant lipids may protect against fibrogenesis by promoting fibroblast apoptosis and reducing collagen accumulation [

15]. In addition, PE has been shown to have significant antifibrotic effects. In a bleomycin-induced mouse model of lung fibrosis, PE reduced collagen expression, promoted apoptosis, and attenuated overall fibrosis [

16]. Similarly, organically synthesized PE induced early apoptosis at low concentrations, significantly increased late apoptosis at higher doses in NHLF, further strengthening its potential as a therapeutic target for PF [

17].

3. Discussion

In this study, a NPPS formulation was obtained with a phospholipid and protein composition similar to other pulmonary surfactants commercially available. Once enriched with PE (NPPS-PE), the biophysical evaluation showed a synergistic activity of PE on NPPS surface activity. Furthermore, the effect of the NPPS-PE mixture in NHLF was found to induce an antifibrotic action, as previously observed in experiments with commercial substances [

16]. We also provide evidence that NPPS-PE improves oxygenation in an animal model of surfactant deficiency.

Pulmonary surfactant is used worldwide for treating neonatal respiratory distress syndrome [

18]; however, at the clinical level, it is used to treat other respiratory conditions in neonates, such as neonatal pneumonia, meconium aspiration syndrome, acute respiratory failure in neonates, and newborns who have experienced hypoxia during labor [

18,

19]. Treatment of these diseases with pulmonary surfactant has increased life expectancy [

20]. Pulmonary surfactant can be of bovine or porcine origin, with the latter being somehow more efficient likely as a consequence of its different method or production, although some clinical trials mention that there are no significant differences between using bovine versus porcine surfactants [

21,

22]. Exogenous pulmonary surfactant can be obtained through minced tissue or tracheobronchial lung lavage [

23]with minced lavage typically extracting more non-surfactant lipid/protein material. In this study, porcine lung lavages were performed, thus obtaining native surfactant that is more similar to that found on the alveolar surface.

The biophysical function of pulmonary surfactant is to reduce surface tension in the lungs, which helps preventing the alveoli from collapsing [

8]. A good surfactant must fulfill three essential functions for respiration: forming an active film during inhalation, reorganizing to reduce surface tension during exhalation, and redistributing lipids in the next inhalation to prevent alveolar collapse [

24,

25]. The transition from a tilted-condensed phase to a liquid-expanded phase is critical for surfactant function, as the liquid-expanded phase favors the reduction of surface tension in the pulmonary alveoli, helping to keep them open during breathing [

8,

26]. The addition of PE improved surfactant activity. Using the Langmuir film balance, NPPS alone showed a typical surfactant compression-expansion isotherm (surface pressure versus surface area) [

27,

28]. However, when PE was added, it showed an optimal maximum surface tension of ~70 mN/m, which collapses near ~10 mN/m. This values are comparable to what has been described in other studies [

29]. Another interesting finding was observed in condensed domain segregation. Domain formation indicates that this surfactant can be reincorporated into type II epithelial cells [

8,

28,

30]. The addition of PE facilitated domain segregation in a concentration-dependent manner, causing domains to segregate at higher pressures and to a greater extent, possibly due to a synergistic action. Similar results were observed in the surface tension evaluation with the captive bubble surfactometer, confirming that PE optimizes adsorption dynamics.

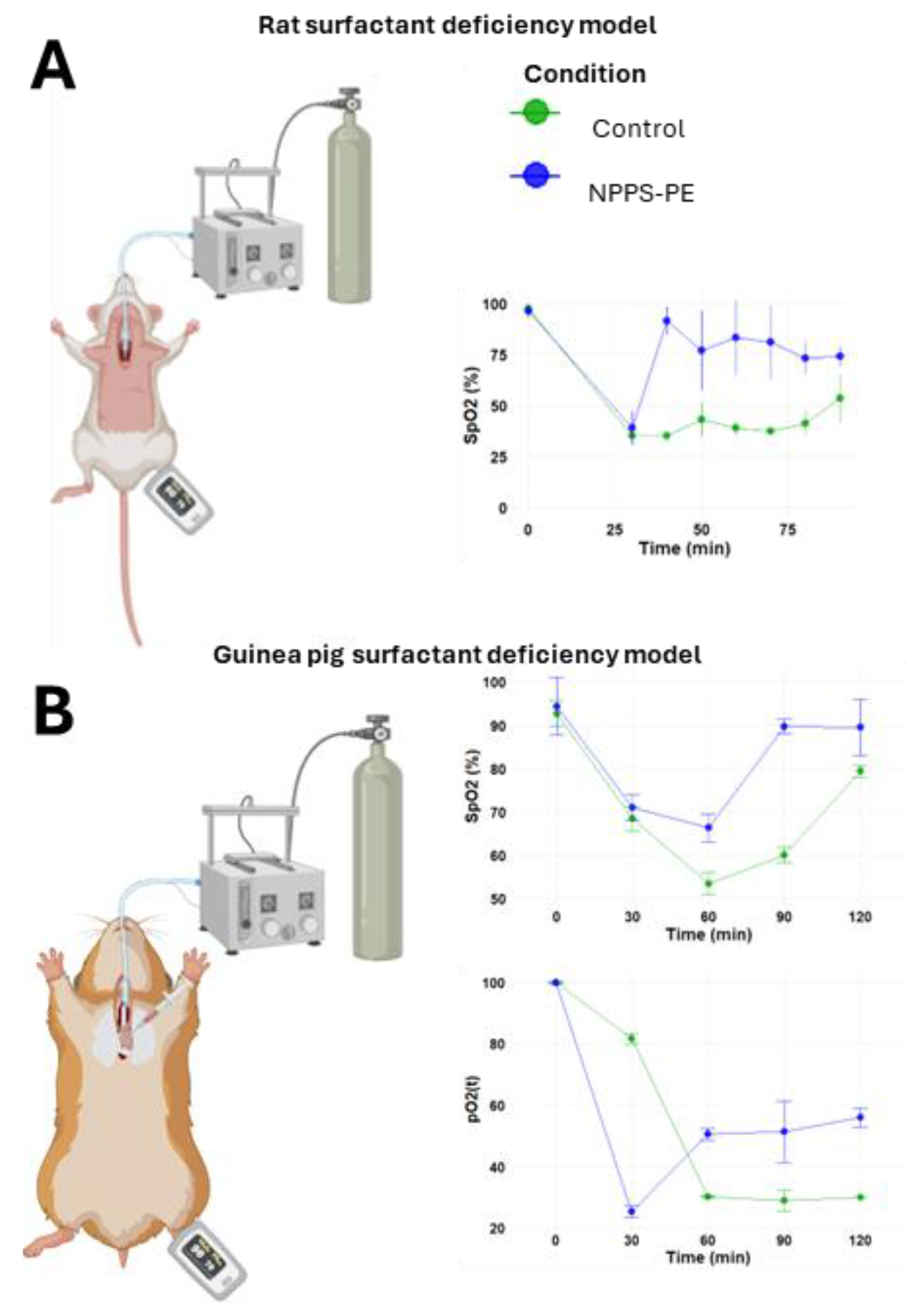

The results with the

in vivo models of surfactant deficiency parallel the findings observed in the

in vitro experiments. In the surfactant deficiency models in rats and guinea pigs, we evaluated gasometric parameters and O

2 saturation. As a replacement therapy for surfactant deficiency, we administered the NPPS-PE mixture. The results showed increased oxygenation and O

2 saturation, which is consistent with findings in other surfactant deficiency models [

31,

32].

The biochemical composition of NPSS is comparable to other exogenous lung surfactants commercially available. In this study, we qualitatively assessed by TLC the presence of, sphingomyelin, phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylserine, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylglycerol, cholesterol, and phosphatidylcholine (

Figure S1). Regarding the proportion of PE in our NPPS, it was found to contain 7%, similar to the amount present in other surfactants extracted via lung lavage and of porcine origin, such as Butantan and Poractant-α, which contain 7% and 6%, respectively [

23].

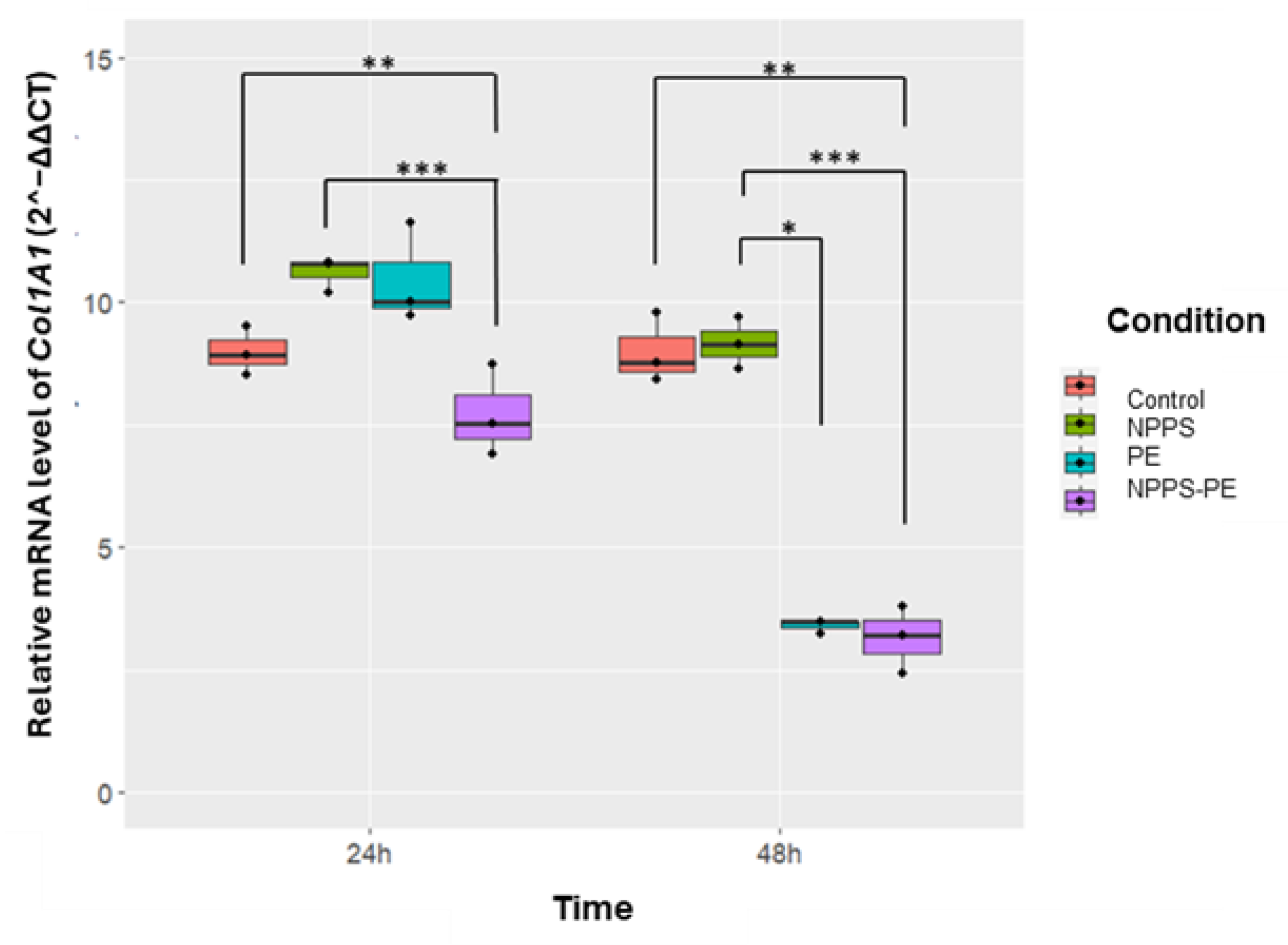

NPPS-PE decreased the expression of collagen and increased apoptosis in fibroblasts. PF is the result of a pathological process characterized by the excessive proliferation of fibroblasts, which leads to uncontrolled accumulation of collagen-rich extracellular matrix [

2,

33]. Furthermore, these fibroblasts become resistant to apoptosis, a biological process that should be activated once the damaged tissue has been repaired [

17,

34], hence, fibroblasts continue to proliferate and accumulate extracellular matrix, perpetuating the damage and altering the structure and mechanical properties of the lung tissue [

2,

35,

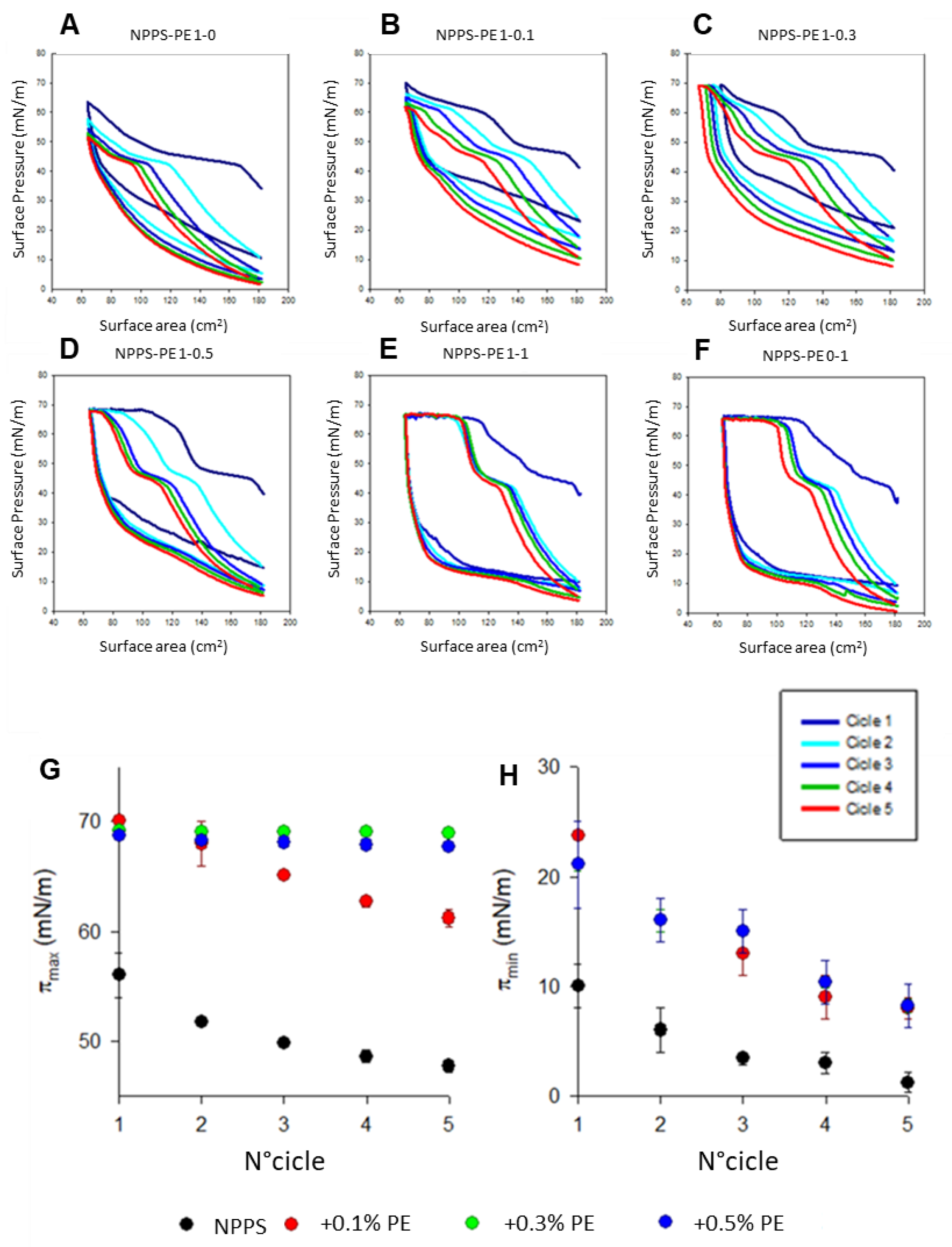

36]. The mechanism of action of NPPS-PE in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis is not clearly understood. Using a murine model of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis, we found that NPPS-PE administration reduced collagen deposition and attenuated fibrosis, particularly when applied during the inflammatory phase. We tested NPPS-PE administration via inhalation in a murine model of bleomycin-induced lung injury and fibrosis, taking advantage of its ability to directly target the affected organ. Our study focused on the optimal timing of treatment following bleomycin administration, which initiates an inflammatory cascade characterized by cytokine recruitment, immune cell infiltration, and epithelial damage by day 0 [

37]. This inflammatory process facilitates the migration of immune cells, including neutrophils and lymphocytes [

38], and promotes fibroblast recruitment through macrophage-mediated signaling [

4]. The inflammatory phase also leads to damage of the basement membrane, an essential structure for cellular adhesion and lung architecture. NPPS-PE complexes could be incorporated into alveolar coating films, potentially modulating the inflammatory response and stabilizing the pulmonary surfactant biophysical action. It has been proposed that pulmonary surfactant dysfunction and the concomitant defective mechanics could precede the fibrotic and pro-fibrotic phenotype [

39] and therefore constitute an early marker in the pathway to fibrotic lungs as a consequence of damage and inflammation. Treatment with NPPS-PE could prevent that surfactant contribution, facilitating proper breathing mechanics during the time required to resolve inflammation and tissue repair. Evidence suggests that by day 3 post-bleomycin administration, the inflammatory process remains active, with persistent immune cell infiltration and the initiation of fibroblast recruitment [

37]. At this stage, NPPS-PE administration could directly influence fibroblasts before they form fibrotic foci, perhaps by reducing at least part of the mechanosensing stimuli that define fibroblast proliferation, potentially inducing apoptosis, and decreasing collagen synthesis—effects we have previously demonstrated in

in vitro models) [

16,

17]. PF results from excessive fibroblast proliferation and the uncontrolled accumulation of collagen-rich extracellular matrix [

2,

36]. Additionally, fibroblasts in fibrotic tissue become resistant to apoptosis, a process that should be activated once tissue repair is complete. The failure of apoptosis activation allows fibroblasts to persist, continuously depositing extracellular matrix and exacerbating lung tissue remodeling [

36]. In this context, the integration of NPPS-PE into the alveolar surface films may help to modulate the response towards fibroblast activation and prevent excessive extracellular matrix deposition. Previously, we have provided evidence that pulmonary surfactant can induce calcium signaling via the IP3 pathway, which may play a role in fibroblast apoptosis [

14,

16]. The incorporation of NPPS-PE into the alveolar respiratory surface, combined with its effects on calcium-mediated signaling, may help in maintaining alveolar structural integrity, as confirmed by our histological analyses. This suggests that NPPS-PE might not only modulate inflammatory responses but also play a role in the regulation of the basement membrane and the control of fibrosis progression. By day 7 in the bleomycin model, fibrosis is in its early stages, with fibroblast invasion into the pulmonary parenchyma disrupting gas exchange. At this point, type II alveolar epithelial cells undergo apoptosis due to alveolar structural damage [

36], impairing the recycling and reintegration of phospholipids necessary for surfactant function [

40]. The loss of basement membrane integrity at this stage exacerbates fibrosis by promoting the continued recruitment of fibroblasts and collagen deposition. At this stage, NPPS-PE is less likely to be effectively incorporated into the alveolar system, suggesting that its therapeutic potential is primarily within the inflammatory phase rather than at the fibrotic stage. Thus, NPPS-PE appears to exert its most significant therapeutic effects by modulating the early inflammatory responses and preventing the degradation of the basement membrane, ultimately reducing the progression of fibrosis. This mechanism underscores its potential as a novel therapeutic agent in PF, particularly in the early stages when the inflammatory processes are most active. (

Figure 9).

One limitation of this study is the use of racemic PE, which contains both enantiomers. Due to the nature of these molecules, the effects of individual enantiomers were not evaluated. Previous studies have suggested that different enantiomers may exert distinct biological activities, and further investigation is warranted to determine whether the racemic mixture or a specific enantiomer is responsible for the observed effects in the NPPS-PE mixture.

The NPPS-PE mixture holds potential as a therapeutic option, similar to other commercial surfactants, for treating diseases in neonates. One promising avenue for future research is the evaluation of NPPS-PE in clinical trials for diseases that could lead to pulmonary fibrosis. In neonatology, diffuse interstitial pneumonia in children is an area of particular concern, as there are currently no effective medications available for treating these conditions in pediatric patients. Therefore, we propose that NPPS-PE could be explored as a therapeutic approach for children diagnosed with diffuse interstitial pneumonia. Looking beyond its current scope, we envision NPPS-PE not only as a treatment for existing conditions but also as a prophylactic agent for diseases that predispose individuals to pulmonary fibrosis. Furthermore, we plan to explore whether NPPS-PE could block key pathways such as TGF-β, which has been identified as a therapeutic target for fibrosis prevention, either alone or combined with TGF-β inhibitory drugs. These investigations could pave the way for specific clinical surfactant formulations such as NPPS-PE to become a valuable tool in both the treatment and prevention of pulmonary fibrosis, especially in pediatric populations. Additionally, the potential application of NPPS-PE in models analogous to acute lung injury should be explored, as it may offer insights into broader therapeutic possibilities for lung diseases.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Preparation, Characterization, and Biophysical Evaluation of NPPS-PE

Porcine lungs were obtained from the local abattoir according to specific criteria: without larynx, heart, or tissue lesions. Bronchoalveolar lavage was performed with 1 L of 0.9% saline solution. The collected bronchoalveolar fluid was centrifuged at 3,500 rpm for 5 min to remove cellular debris, followed by a second centrifugation at 9,000 rpm to obtain a pellet with the large surfactant complexes. The pellet was then processed through a series of solvent systems consisting of methanol:chloroform:water (2:1:0.8). After filtration and separation of the chloroform phase the pellet was treated with acetone to increase the volume 20× for lipid reconstitution and evaporated under nitrogen gas. The resulting pellet was subjected to evaporation to remove solvent traces and later resuspended in a solution of NaCl-CaCl₂ 100-5 mM. Finally, the mixture was sterilized using a flash autoclave at 120°C for 10 min to ensure a sterile and homogeneous product. Total phospholipids in the NPPS were quantified by the Rouser method, which uses phosphorus analysis to measure phospholipid content. Phospholipid classes were analyzed by thin-layer chromatography.

4.2. Evaluation of NPPS-PE Monolayer Properties Using the Langmuir Film Balance

Monolayer experiments were performed at 25 °C using a Langmuir-Blodgett balance (102M micro Film Balance; NIMA Technologies, Coventry, UK) as previously described [

16]. The aqueous subphase contained NaCl-CaCl₂100-5 mM at 25 °C. A 1 mg/mL concentrated solution of the organic lipid extract of NPPS or PE dissolved in chloroform:methanol (1:2) was used for monolayer experiments. The monolayers were formed by spreading 10 µl of a concentrated solution of the organic lipid extract of NPPS-PE at the air-water After evaporation of the organic solvent, the monolayer was allowed to stabilize for 10 min. Monolayers were then cyclically compressed five times.

4.3. Observation of Rhodamine-DOPE-Labeled NPPS-PE Films by Epifluorescence Microscopy

NPPS and PE samples were labeled with 0.1% rhodamine-DOPE suspended in chloroform:methanol (1:2). Subsequently, 20 µL of the Rhodamine-DOPE-labeled NPPS-PE suspension was spread onto the air-liquid interface of the Langmuir film balance, and the organic solvent was allowed to evaporate for 10 min. The interfacial film was then transferred onto a glass coverslip during compression at a constant rate of 25 cm²/min using the Langmuir-Blodgett technique with continuously varying surface pressures [

42]. The transferred films were observed using an epifluorescence Leica DM 4000B microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with an ORCA R2 10,600 camera (Hamamatsu Photonics K.K., Shizuoka, Japan).

4.4. Surface Tension Measurement with a Captive Bubble Surfactometer

The interfacial activity of NPPS samples in the absence and presence of PE suspendend in NaCl-CaCl₂ 100-5 mM was evaluated in a captive bubble surfactometer at 37°C as described in [

41]. The surfactometer chamber contained 5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7, 150 mM NaCl, and 10% sucrose. After a small air bubble (0.035–0.040 cm³) had formed, approximately 150 nL of surfactant (10 mg/mL) was deposited beneath the bubble surface with a transparent capillary. Then, the change in surface tension (γ) was monitored for 5 min from the changes in the shape of the bubble as recorded in a digital camera. The chamber was sealed, and the bubble was rapidly expanded (within 1 s) to a volume of 0.15 cm³ to record the post-expansion adsorption. Five minutes after expansion, quasi-static cycles began, in which the bubble was initially reduced in size (to 20% of its previous volume) and then gradually enlarged. A 1-minute delay was maintained between each of the four quasi-static cycles, and an additional 1-minute delay was added before dynamic cycles started, in which the bubble was continuously compressed and expanded at a rate of 20 cycles per min.

4.5. Isolation and Maintenance of Normal Human Lung Fibroblasts

The isolation of primary NHLF was performed in our laboratory as previously described [

16]. Briefly, NHLF was obtained from lung tissue donated by patients who were diagnosed as brain dead. Family consent was obtained before the procedure, and these donors had no history of lung disease, smoking, allergy, or comorbidities. The Ethics and Research Committees of the Hospital General de Puebla and the Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, Faculty of Medicine, reviewed and approved the study protocol with a registration number (SIEP/C.I/153/2022). The lung piece was obtained from the right lingula with a dimension of 5 × 2 cm in thickness, which is preserved in 30 mL of Ham's F-12 medium without fetal bovine serum. A portion was processed for histopathology. The other portion was minced and incubated for 20 min in 1X trypsin-EDTA solution and serum-free F-12 medium. The digested tissue was gently triturated with a 10 mL pipette and the dissociated cells were filtered through a mesh filter. Filtrate was centrifuged at 200×g for 10 min using an (Eppendorf 5804R centrifuge), and the pellet was resuspended in F-12 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Cells were cultured in T-25 flasks and grown to 75% confluence in F-12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin at 37°C in 95% O₂, 5% CO₂ saturated humidity. Only cells that were derived from lungs with a normal histology as determined by histopathological examination were included in this study. Fibroblasts from passages 5 to 10 were plated on coverslips in petri dishes, allowed to adhere for 24 h, and then incubated in serum-free medium for 48 h.

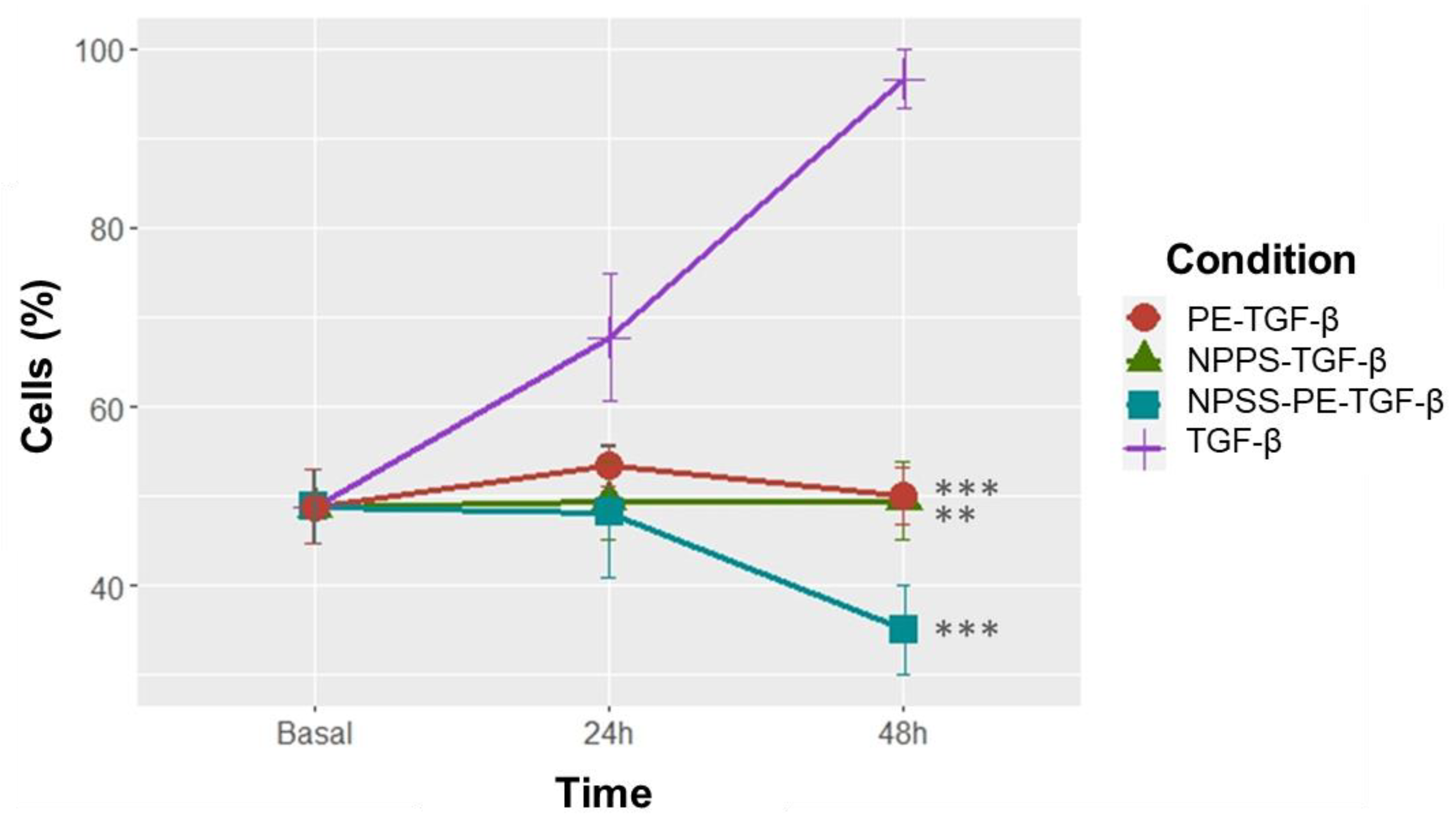

4.6. Cell Proliferation Assay

A Neubauer chamber was used to generate a cell concentration curve with values of 62,500, 46,875, 31,250, 15,625, and 7,813 cells/cm². These cells were seeded in a 96-well plate format. For the experimental conditions, a concentration of 15,625 cells/cm² was used, and all conditions were seeded in triplicate. After seeding the cells and incubating them overnight, the medium was removed, and the experimental conditions were applied. The experimental setup included the following conditions: cells treated with transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) at 1 ng/mL as an inducer of cell proliferation, cells treated with NPPS (500 µg/mL), cells treated with PE (100 µg/mL), and cells treated with NPPS- PE (500 µg/mL and 100 µg/mL, respectively). Cell proliferation was measured at 24 and 48 hours using the WST-1 kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance readings were taken at 550 nm.

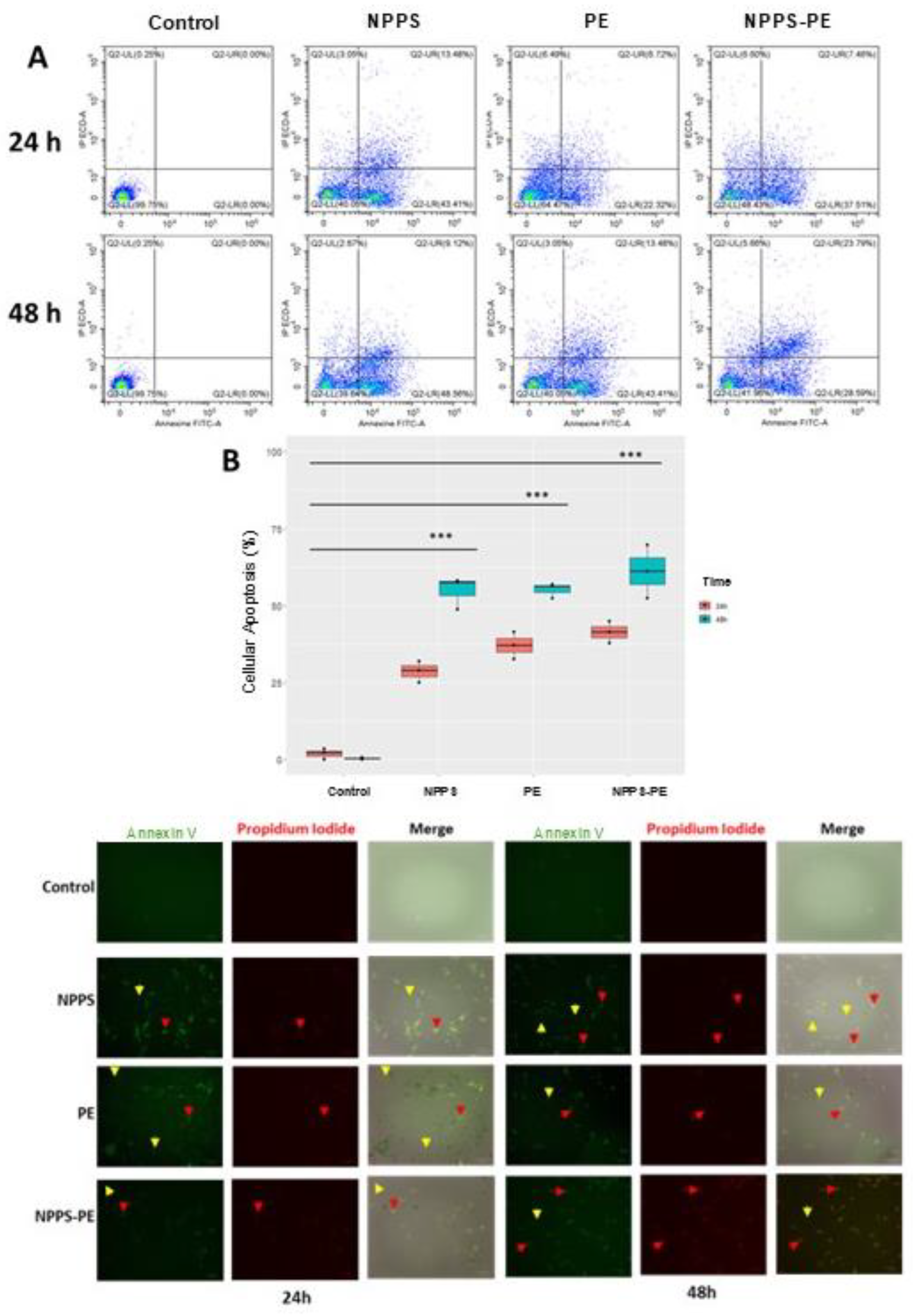

4.7. Evaluation of Apoptosis in NHLF Treated with NPPS-PE by Flow Cytometry

NHLF cells were seeded in 24-well plates at a density of 50,000 cells/mL. Apoptosis was assessed using Annexin-V and propidium iodide according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Apoptosis measurement by flow cytometry was performed using a CytoFlex instrument (Beckman Coulter, USA), and microscopic analysis was performed using a ZOE microscope (Bio-Rad, USA). NHLF cells were treated with medium as a control, NPPS (500 µg/mL), PE (100 µg/mL), and NPPS-PE (500-100 µg/mL). Measurements were performed in triplicate at 24 and 48 h.

4.8. Determination of COL1A1 Expression by RT-qPCR

Total RNA extraction was performed using TRIzol (Ambion by Life Technologies, USA; Cat. No. 15596-026), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. NHLF cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 300,000 cells per well, and the experimental groups were as follows: control cells cultured in Ham-F12 medium without fetal bovine serum, NPPS-treated cells (500 µg/mL), PE-treated cells (100 µg/mL), and NPPS-PE-treated cells (500-100 µg/mL). The incubation time for the experimental conditions was 24 and 48 h. The extracted RNA was quantified using the NanoDrop 100 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), and stored at -70°C. RNA was converted to cDNA using a thermal cycler and the H Minus First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Scientific, USA), RT-qPCR was performed using GAPDH (Hs02786624_g1) as the reference gene and COL1A1 (Hs00164004_m1) as the target gene. The PCR conditions were set as 2 minutes at 94 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 seconds at 95 °C and 1 minute at 60 °C, finishing with an indefinite cooling loop. Each experimental sample was loaded in triplicate, along with the triplicate of the GAPDH gene. Samples were processed on a Rotor-Gene Q thermal cycler (Qiagen, Germany).

4.9. Determination of the Effect of NPPS-PE in C57BL/6 Mice Treated with Bleomycin

The bleomycin model was established using C57BL/6 mice, weighing 30-40 g and six weeks old. Bleomycin instillation was done intratracheally at a dose of 3U/kg in 30 µl [

16]. Treatments were administered through nebulization, with NPPS-PE 400-80 mg/kg diluted to 1.5 mL with saline solution. Treatments commenced on days 0, 3, and 7 (

Figure 9). The animals were euthanized on day 20 under anesthesia. The right lung was used for hydroxyproline quantification, while the left lung was subjected to H&E and Masson's Trichrome staining, with analysis performed using Orbit Image Analysis machine learning software.

4.10. Pulmonary Surfactant Deficiency Model in Animal Models of Surfactant Deficiency Treated with NPPS-PE

A total of 6 Sprague-Dawley rats (weighing 250-300 g) and 6 guinea pigs (Cavia porcellus) were obtained and divided into two groups according to species: a control group with the vehicle and a group treated with NPPS-PE (100 mg/kg of body weight) from a NPPS-PE preparation (25 and 5 mg, respectively). The treatments were suspended in NaCl-CaCl₂ 100-5 mM. The animals were anesthetized with a mixture of xylazine/ketamine (20 and 100 mg/mL, respectively) at a dose of 0.2 mL per 100 g. They were then immobilized and placed in a supine position with the jaw retracted. An incision was made at the level of the trachea, which was then localized and cannulated. The animals were then placed on a positive pressure ventilator (Harvard Small Animal Mouse Ventilator, Model 687, 55-0001) delivering O2 at a flow rate of 2 L/min. Rats were ventilated at a frequency of 90 breaths per min, guinea pigs were ventilated at 100 breaths per min, with an O2 volume of 2.5 mL per breath. Three lung lavages were performed over a 30-min period, alternating with mechanical ventilation. Each lavage was performed with 0.9 % saline solution at a rate of 35 mL/kg at 37°C. After the lung lavage and induction of pulmonary surfactant deficiency, the appropriate treatment was administered. The guinea pigs’ right atrium was punctured to obtain blood samples of 300 µL, which were analyzed using a blood gas analyzer (GEM Premier 3500) at times 0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min. During the experimental phase, oxygen saturation (SpO2) was monitored using a pediatric pulse oximeter placed on the left paw.

4.11. Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation of experiments performed in triplicate. Data analysis of the biophysical assessment was performed using Prism v.9.5.0 software (GraphPad), while the remaining data were processed using R 4.4.1. Statistical inferential analysis was performed with ANOVA using a significance level of p<0.05, and a bilateral Dunnett's post-hoc test was conducted.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Beatriz Tlatelpa-Romero and Luis Vázquez-de-Lara Cisneros; Data curation, Luis Vázquez-de-Lara Cisneros; Formal analysis, Beatriz Tlatelpa-Romero, Luis Vázquez-de-Lara Cisneros, Criselda Mendoza-Milla, José Martinez-Vaquero, Rene de-la-Rosa-Paredes and Roberto Berra-Romani; Funding acquisition, Luis Vázquez-de-Lara Cisneros, Jesús Pérez-Gil and Alonso Collantes-Gutiérrez; Investigation, Beatriz Tlatelpa-Romero; Methodology, Beatriz Tlatelpa-Romero, Olga Cañadas, Amaya Blanco and Barbara Olmeda; Project administration, Yair Romero; Resources, Luis Vázquez-de-Lara Cisneros, Jesús Pérez-Gil, Rene de-la-Rosa-Paredes, Alonso Collantes-Gutiérrez and María Pérez-Fernández; Software, Sinhué Ruiz-Salgado; Supervision, Olga Cañadas and Jesús Pérez-Gil; Validation, Jesús Pérez-Gil and Yair Romero; Visualization, Beatriz Tlatelpa-Romero; Writing – original draft, Beatriz Tlatelpa-Romero and Olga Cañadas; Writing – review & editing, Luis Vázquez-de-Lara Cisneros, José Martinez-Vaquero and Roberto Berra-Romani..

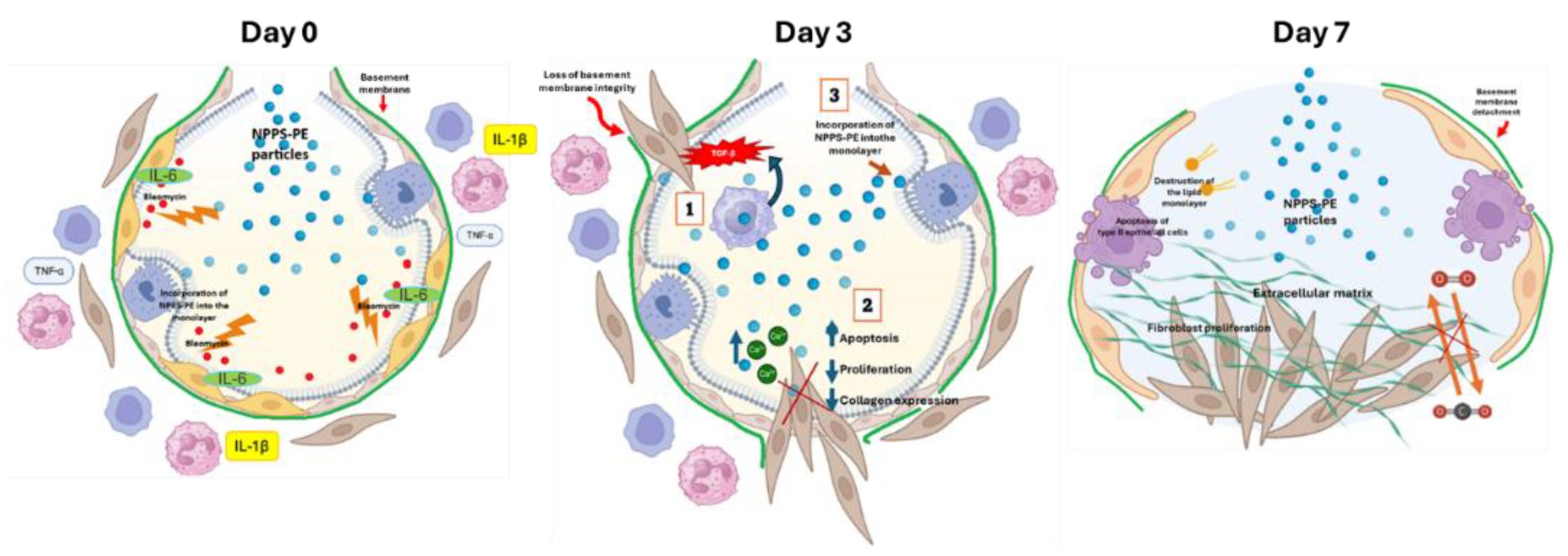

Figure 1.

Effect of PE on NPPS compression/expansion cycles. A-F) π-area isotherms obtained from five cycles for pure SPP monolayers (A), SPP:PE blends with molar ratios 1:0.1 (B), 1:0.3 (C), 1:0.5 (D), and 1:1 (E), and pure PE (F). G and H) Effect of PE on the maximum (πmax) (G) and minimum (πmax) (H) surface pressure reached by the isotherms of SPP isolated from porcine lung lavages during compression cycles.

Figure 1.

Effect of PE on NPPS compression/expansion cycles. A-F) π-area isotherms obtained from five cycles for pure SPP monolayers (A), SPP:PE blends with molar ratios 1:0.1 (B), 1:0.3 (C), 1:0.5 (D), and 1:1 (E), and pure PE (F). G and H) Effect of PE on the maximum (πmax) (G) and minimum (πmax) (H) surface pressure reached by the isotherms of SPP isolated from porcine lung lavages during compression cycles.

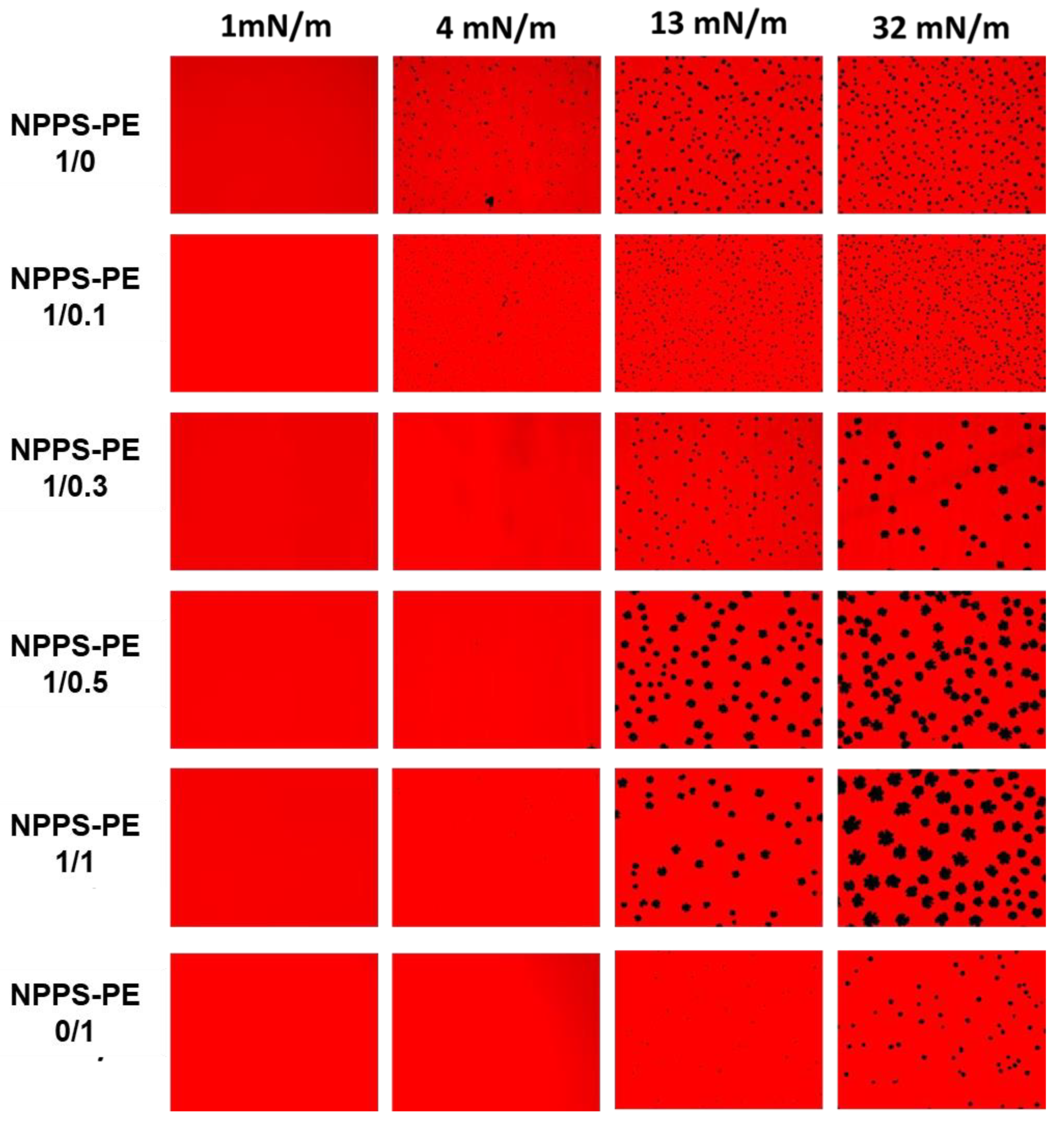

Figure 2.

Micrographs obtained from the transfer of NPPS-PE (1/0, 1/0.1, 1/0.3, 1/0.5, 1/1, 0/1) stained with Rho-DPPE, experiments performed on the Langmuir balance. Images of NPPS were obtained alone and in the presence of PE. The transfers of the interfacial films were performed on glass slides and observation under an epifluorescence microscope. Monolayers in a homogeneous expanded liquid (LE) phase are shown at 1 mN/m. Further compression of the monolayer resulted in the nucleation and growth of domains in the crystal phase (CP) with gradual incorporation of PE into NPPS.

Figure 2.

Micrographs obtained from the transfer of NPPS-PE (1/0, 1/0.1, 1/0.3, 1/0.5, 1/1, 0/1) stained with Rho-DPPE, experiments performed on the Langmuir balance. Images of NPPS were obtained alone and in the presence of PE. The transfers of the interfacial films were performed on glass slides and observation under an epifluorescence microscope. Monolayers in a homogeneous expanded liquid (LE) phase are shown at 1 mN/m. Further compression of the monolayer resulted in the nucleation and growth of domains in the crystal phase (CP) with gradual incorporation of PE into NPPS.

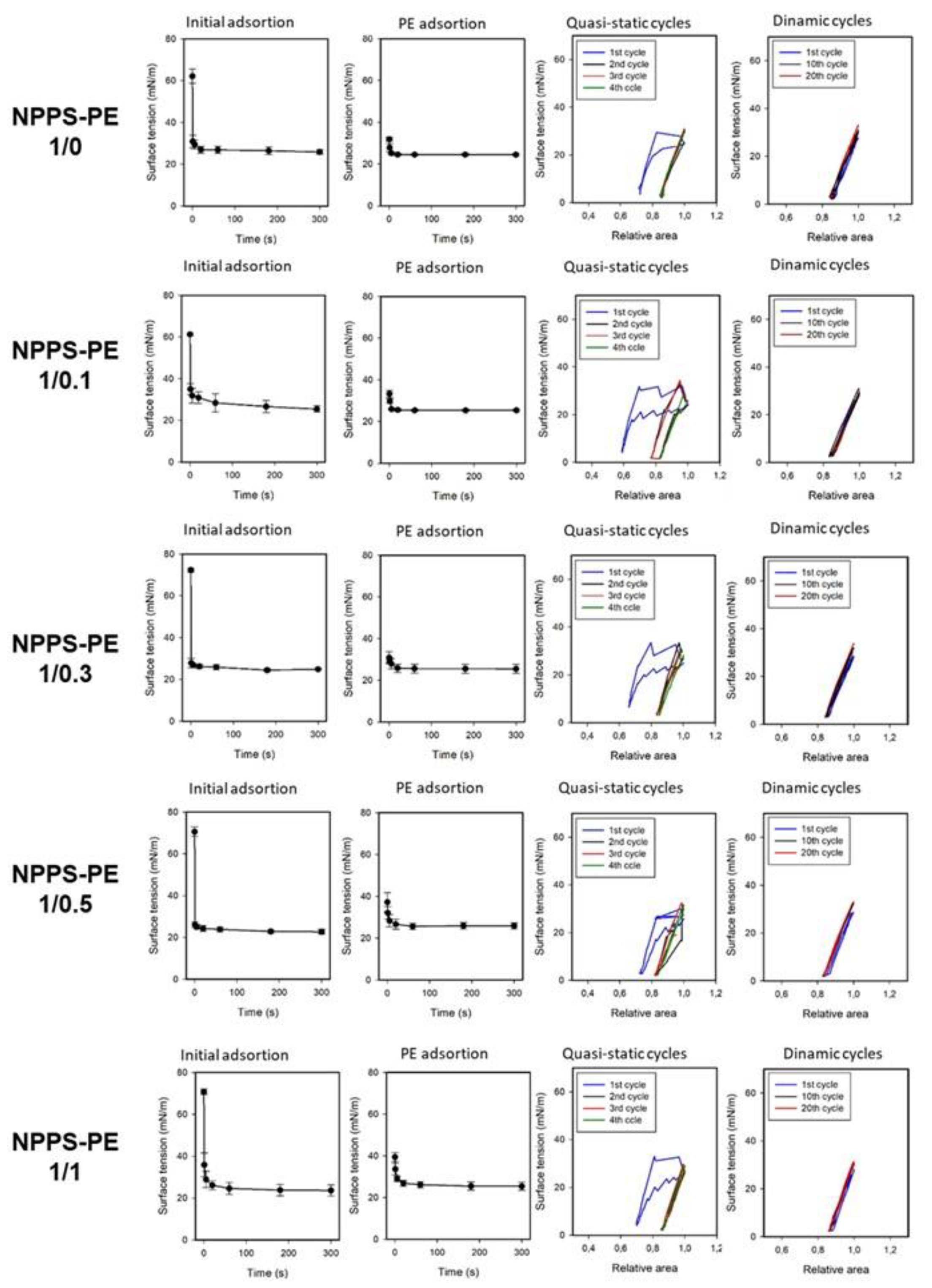

Figure 3.

Surface tension evolution of PE-enriched NPPS at different molar ratios (1/0, 1/0.1, 1/0.3, 1/0.5, 1/1, 0/1). The first two columns show the change in surface tension as a function of time during initial adsorption and post-expansion. The last two columns represent the quasi-static and dynamic compression-expansion cycles. A captive bubble surfactometer was used to measure, with an average of three experiments and the standard deviation represented by the error bars.

Figure 3.

Surface tension evolution of PE-enriched NPPS at different molar ratios (1/0, 1/0.1, 1/0.3, 1/0.5, 1/1, 0/1). The first two columns show the change in surface tension as a function of time during initial adsorption and post-expansion. The last two columns represent the quasi-static and dynamic compression-expansion cycles. A captive bubble surfactometer was used to measure, with an average of three experiments and the standard deviation represented by the error bars.

Figure 2.

Surfactant deficiency models in animals. A) Oxygen saturation (SpO₂) was monitored using pulse oximetry in rats, while B) partial oxygen pressure (PaO₂) and SpO₂ were quantified in blood samples from the right ventricle in guinea pigs. In both models, the groups were the control group and the group treated with NPPS-PE at multiple time points. The results showed that treatment with NPPS-PE improved respiratory parameters over time in both models.

Figure 2.

Surfactant deficiency models in animals. A) Oxygen saturation (SpO₂) was monitored using pulse oximetry in rats, while B) partial oxygen pressure (PaO₂) and SpO₂ were quantified in blood samples from the right ventricle in guinea pigs. In both models, the groups were the control group and the group treated with NPPS-PE at multiple time points. The results showed that treatment with NPPS-PE improved respiratory parameters over time in both models.

Figure 5.

The effect of NPPS enriched with PE on normal human lung fibroblasts (NHLF) collagen expression (Col1A1) was determined by RT-qPCR. The graphical results reveal that at 24 and 48 hours, the combination of NPPS-PE leads to a significant decrease in Col1A1 expression in NHLF. It is important to note that when NPPS was enriched with PE, its inhibitory effect on Col1A1 expression was notably enhanced.

Figure 5.

The effect of NPPS enriched with PE on normal human lung fibroblasts (NHLF) collagen expression (Col1A1) was determined by RT-qPCR. The graphical results reveal that at 24 and 48 hours, the combination of NPPS-PE leads to a significant decrease in Col1A1 expression in NHLF. It is important to note that when NPPS was enriched with PE, its inhibitory effect on Col1A1 expression was notably enhanced.

Figure 6.

Effect of NPPS-PE Treatment in a Bleomycin-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis Model. (A) Experimental Timeline: Pulmonary fibrosis was induced by a single dose of bleomycin (day 0). Mice were treated with either saline solution (control) or NPPS-PE at three different time points: at the onset of injury (day 0), during the inflammatory phase (day 3), and in the early fibrotic phase (day 7). Lungs were collected on day 20 for histological and biochemical analysis. The treatment was administered by inhalation, placing the mice in a containment chamber. (B) Collagen Deposition: hydroxyproline levels, a marker of collagen deposition, significantly increased following bleomycin administration compared to controls. NPPS-PE treatment significantly reduced these levels in the groups treated on days 0 and 3 (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001). The percentage of collagen in alveolar walls, assessed by histological staining, showed an increase in bleomycin-treated mice, which was partially reversed by NPPS-PE treatment on days 0 and 3 (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001). (C) Histological Images: Lung sections stained with Masson's Trichrome revealed collagen accumulation (blue areas) following bleomycin treatment, with a significant reduction after NPPS-PE treatment.

Figure 6.

Effect of NPPS-PE Treatment in a Bleomycin-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis Model. (A) Experimental Timeline: Pulmonary fibrosis was induced by a single dose of bleomycin (day 0). Mice were treated with either saline solution (control) or NPPS-PE at three different time points: at the onset of injury (day 0), during the inflammatory phase (day 3), and in the early fibrotic phase (day 7). Lungs were collected on day 20 for histological and biochemical analysis. The treatment was administered by inhalation, placing the mice in a containment chamber. (B) Collagen Deposition: hydroxyproline levels, a marker of collagen deposition, significantly increased following bleomycin administration compared to controls. NPPS-PE treatment significantly reduced these levels in the groups treated on days 0 and 3 (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001). The percentage of collagen in alveolar walls, assessed by histological staining, showed an increase in bleomycin-treated mice, which was partially reversed by NPPS-PE treatment on days 0 and 3 (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001). (C) Histological Images: Lung sections stained with Masson's Trichrome revealed collagen accumulation (blue areas) following bleomycin treatment, with a significant reduction after NPPS-PE treatment.

Figure 7.

Proposed Mechanism of Action of NPPS-PE in Bleomycin-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis. Day 0 – Bleomycin induces epithelial damage, leading to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α. NPPS-PE particles are incorporated into the epithelial monolayer, suggesting potential modulation of the inflammatory response and protection of the basement membrane from the harmful effects of bleomycin. Day 3 – Disruption of epithelial integrity. Bleomycin causes loss of basement membrane integrity, facilitating TGF-β signaling produced by macrophages, which recruits fibroblasts to the alveolar space. This leads to fibroblast proliferation and collagen deposition, a key process in pulmonary fibrosis. The incorporation of NPPS-PE into the epithelial layer appears to modulate these processes. Day 7 – Fibrotic stage. Persistent epithelial damage, type II alveolar cell apoptosis, and lipid monolayer destruction result in fibroblast proliferation and extracellular matrix accumulation, characterizing the fibrotic phase. NPPS-PE particles are no longer able to modulate this process, as fibroblasts have formed fibrotic foci, leading to loss of alveolar structure and impaired gas exchange.

Figure 7.

Proposed Mechanism of Action of NPPS-PE in Bleomycin-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis. Day 0 – Bleomycin induces epithelial damage, leading to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α. NPPS-PE particles are incorporated into the epithelial monolayer, suggesting potential modulation of the inflammatory response and protection of the basement membrane from the harmful effects of bleomycin. Day 3 – Disruption of epithelial integrity. Bleomycin causes loss of basement membrane integrity, facilitating TGF-β signaling produced by macrophages, which recruits fibroblasts to the alveolar space. This leads to fibroblast proliferation and collagen deposition, a key process in pulmonary fibrosis. The incorporation of NPPS-PE into the epithelial layer appears to modulate these processes. Day 7 – Fibrotic stage. Persistent epithelial damage, type II alveolar cell apoptosis, and lipid monolayer destruction result in fibroblast proliferation and extracellular matrix accumulation, characterizing the fibrotic phase. NPPS-PE particles are no longer able to modulate this process, as fibroblasts have formed fibrotic foci, leading to loss of alveolar structure and impaired gas exchange.