1. The UD Annotation of Old English

Universal Dependencies (UD) is an annotation framework developed for Natural Language Processing tasks, cross-linguistic comparison, translation, and language learning (Nivre et al., 2016; Nivre et al., 2020; Zeman, 2024). The UD framework provides a universal inventory of lexical categories, morphological features, and dependency relations suitable for cross-linguistic analysis that can also accomodate language-specific phenomena (de Marneffe et al., 2014; de Marneffe et al., 2021). UD adopts a dependency-based syntactic representation, where binary asymmetric relations are established between heads and dependents (de Marneffe and Manning, 2016). The annotation framework is organised into three layers: universal part-of-speech tags (UPOS), morphological features (FEATS), and syntactic dependencies (DEPREL). The UPOS layer consists of seventeen general lexical categories; the FEATS layer encodes morphological properties such as gender, number, case, and tense; and the DEPREL layer comprises a set of universal dependency relations that can be extended to handle language-specific constructions. Overall, UD prioritises universal linguistic patterns over language-specific ones, does not consider empty categories, and favours content words as syntactic heads over function words.

Old English (650–1150 CE) is a West Germanic language with a predominantly Germanic lexicon with borrowings from Latin and Old Norse. It is notable for its semantic transparency in word-formation (Kastovsky, 1992), extensive inflection in nominal, pronominal, and verbal categories (Campbell, 1987; Middeke, 2022), and relatively free word order compared to Modern English (Fischer et al., 2000; Ringe and Taylor, 2014). From the typological point of view, Old English is an SVO language in transition from the SOV type (Pintzuk, 1991, 1999; Kroch and Taylor, 2000; Koopman, 2005; Haeberli and Pintzuk, 2006; Van Kemenade, 2006), which still surfaces in some dependent clauses and is reflected by other areas of grammar such as postposition or the genitive (Allen, 2008). The written records of Old English amount to approximately 3 million words, preserved in around 3,000 texts. The primary corpora for Old English are The Dictionary of Old English Web Corpus (3 million words; Healey et al., 2004) and The York-Toronto-Helsinki Parsed Corpus of Old English Prose (hereafter YCOE; 1.5 million words; Taylor et al., 2003), the latter providing POS tagging and syntactic parsing for roughly half of the extant texts.

Recent research has applied the UD framework to the annotation of Old English. Martín Arista (2022a, 2022b, 2024) establishes the foundations for parsing Old English within UD and extends the annotation framework to include word-formation processes. This extension reflects the syntactic regularities and overlaps found in derivational processes and nominalisations in Old English, particularly those that inherit verbal properties (Ojanguren López, 2024). As regards automatic dependency annotation, Villa and Giarda (2023) evaluate the performance of a multilingual parser for Old English. Their study shows that combining Old English data with data from German and Icelandic yields the highest accuracy, with a peak performance of 75% accuracy for datasets combining Icelandic, German, and Old English. Villa and Giarda attribute these relatively low accuracy levels to linguistic factors such as Old English word order and case syncretism. These authors identify areas of error such as postpositions and discontinuity in relative clauses. They also note that inaccurate part-of-speech tagging leads to errors in dependency relations such as coordinating conjunctions, negation adverbial modifiers, auxiliaries, and locative and temporal adverbial modifiers. The work by Villa and Giarda (2023) is discussed in more detail in

Section 4, which compares their methods and results with this research.

Against this background, this paper focuses on the evaluation of UD parsing, with a specific focus on assessing how different neural architectures perform on the processing of Old English and on gauging the impact of the dataset sizes. The paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 describes the different pipeline architectures and datasets of this study.

Section 3 evaluates the performance of the models and the corpora with respect to the components of the pipeline.

Section 4 compares our results with the state of the art in Natural Language Processing in general and with the automatic parsing of Old English in particular.

Section 5 draws the main conclusions of the study.

2. Models and Data of the Study

Three models have been trained on four dataset sizes, which are described in the remainder of this section. The first model is a basic pipeline with default configuration that uses the spaCy default tok2vec component initialised with random weights. The second model also uses the tok2vec component but initialises its weights through a pretraining phase on an unannotated Old English corpus of about three million words. The third model is based on training from scratch with approximately 17 MB of text. Then, we the tok2vec component is replaced with a custom-trained MobileBERT transformer.

The MobileBERT architecture (25.3 million parameters) was selected to match the limited size of available Old English training data. However, transfer learning from contemporary English BERT models was not viable for the reasons of lexical distance between Present-Day English and Old English, which has a consistently Germanic word stock; and spelling differences with respect to the contemporary language, which has lost certain graphemes (<æ/Æ>, <ȝ/Ȝ>, <ð/Ð>, <þ/Þ>, and <ƿ/Ƿ>) that English models cannot handle.

The pipeline architecture adopted in the test is based on the NLP library spaCy. It consists of six major components or stages, each handling specific aspects of the processing of Old English texts, which can be seen in

Figure 2. The first stage is the Tokenizer, a rule-based component that splits text into tokens by using predefined English rules. Unlike other components, the Tokenizer is non-trainable and serves as the initial stage that converts plain text into the internal data structure required by spaCy. Following tokenization, the second stage implements either a tok2vec or transformer component, both of which transform tokens into numerical vectors. Given the limited size of the dataset, this component is shared across subsequent stages to reduce the number of trainable parameters. Two implementations have been tested: the standard tok2vec and a MobileBERT transformer. The middle layers of the pipeline consist of the Tagger, which assigns POS tags (XPOS column), and the Morphologizer, responsible for UPOS and FEATS assignments. These components incorporate the vector representations provided by the previous stage. The pipeline continues with the trainable Lemmatizer component for LEMMA assignments, followed by the Parser, which handles both dependency parsing (HEAD and DEPREL assignments) and sentence boundary detection.

Figure 1.

Pipeline stages.

Figure 1.

Pipeline stages.

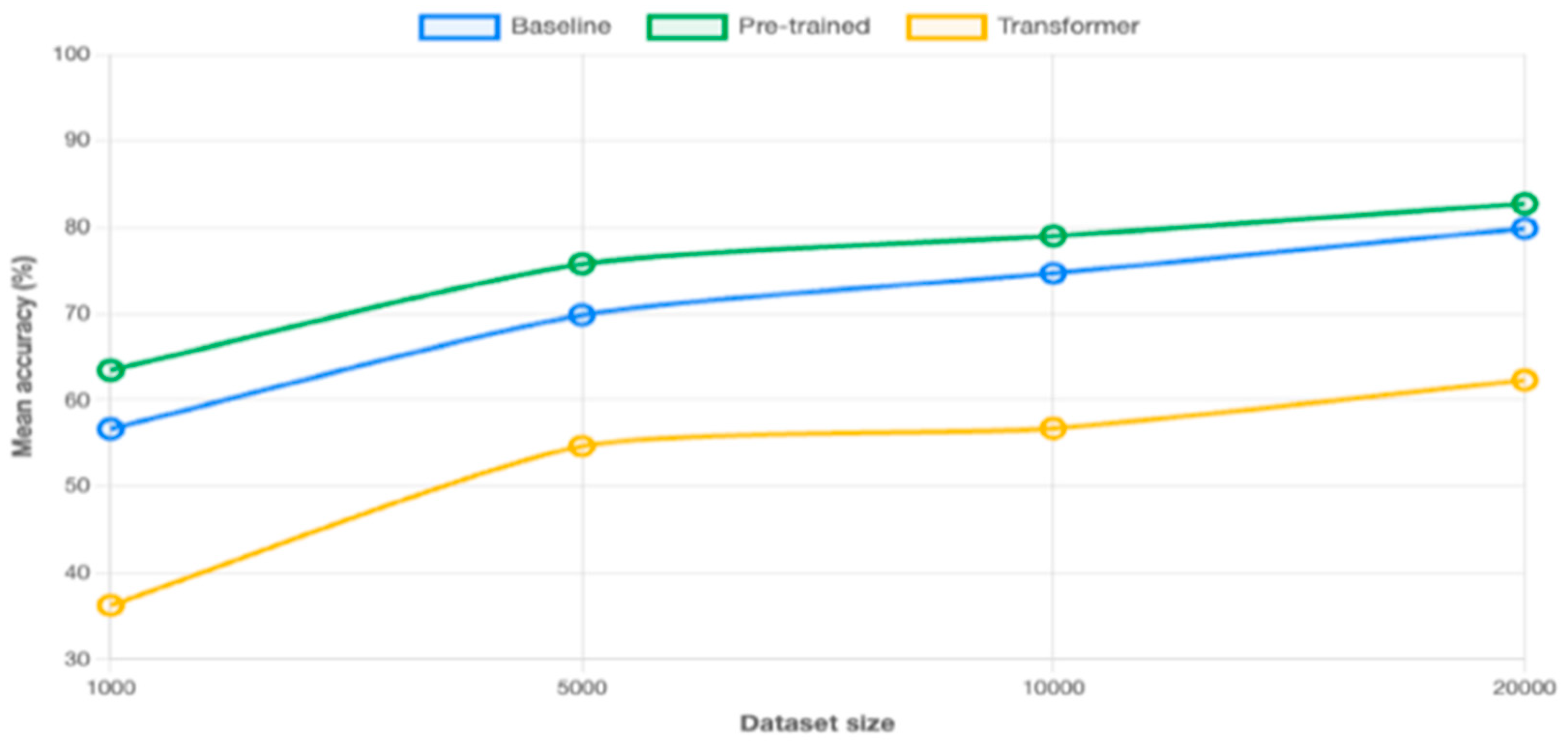

Figure 2.

Mean accuracy across all metrics by dataset size.

Figure 2.

Mean accuracy across all metrics by dataset size.

Thus described, the implementation maintains the pipeline architecture of spaCy, in which components can be trained independently or jointly. The pipeline also adopts the standard training workflow of spaCy, with configurable batch sizes (set to process at least 100 words per batch) and evaluation intervals (every 200 iterations). The evaluation metrics (TAG_ACC, POS_ACC, MORPH_ACC, LEMMA_ACC, DEP_UAS, DEP_LAS, and SENTS_F) are all standard spaCy metrics and are calculated with built-in evaluation functions. Additionally, the loss tracking capabilities during training are used to assess the performance of individual components. Separated loss values are obtained for the tok2vec, Tagger, Morphologizer, Lemmatizer, and Parser stages.

The source of the datasets is ParCorOEv3. An open access annotated parallel corpus Old English-English (Martín Arista et al., 2023). The choice of curated Old English text includes Ælfric’s Catholic Homilies I, The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle A, Anglo-Saxon Laws, St. Mark’s Gospel and King Alfred’s Orosius. The data of the test have been structured in four datasets of different sizes: 1,000, 5,000, 10,000, and 20,000 words for training. These increasing sizes have been established with a view to gauging the relationship between training data volume and model performance. This is a fundamental aspect, considering the scarcity of Old English written records and annotated corpora noted above. An independent evaluation corpus (20%), which has been fully segregated from the training data, has provided benchmarking throughout the test. For pre-training purposes, we have used a larger unannotated corpus of approximately 3 million words (The Dictionary of Old English Corpus; Healey et al. 2004). The training and test datasets are described by words, tokens and sentences in

Table 1.

3. Performance Evaluation

Performance evaluation consists of multiple accuracy metrics for each component. The performance of the Tagger has been measured through TAG_ACC for XPOS tagging. The performance of the Morphologizer has been tracked via POS_ACC (UPOS) and MORPH_ACC (FEATS). The performance of the Lemmatizer has been evaluated through LEMMA_ACC. Dependency parsing has been gauged through both unlabeled (DEP_UAS) and labeled (DEP_LAS) attachment scores. Sentence boundary detection has been evaluated by using the SENTS_F metric. LAS (Labelled Attachment Score) and UAS (Unlabelled Attachment Score) are standard evaluation metrics in dependency parsing (Nivre et al., 2007; Kübler et al., 2009; Manning, 2011). Whereas the UAS measures the percentage of tokens that are assigned the correct syntactic head, the LAS represents the percentage of tokens that are assigned both the correct syntactic head and the correct dependency label. As a more stringent measure, the LAS is always equal to or lower than the UAS.

Figure 2 presents the results of mean accuracy across all metrics by dataset size. The mean is calculated from TAG, POS, FEATS, LEMMA, UAS, LAS and SENT-F metrics (see the Appendix for a breakdown of scores by metric, architecture and dataset).

The performance analysis of this study reflects different degrees of task difficulty. Basic tagging tasks achieve 85-90% accuracy, while morphological analysis reaches around 80% accuracy. Dependency parsing gets lower metrics, with accuracy around 75%. The pretrained model performs better across all metrics and corpus sizes. The transformer-based model obtains lower metrics.

The first model, using the default configuration of spaCy, establishes a baseline for performance. The model performs well on basic tokenization and simple POS tagging, with accuracy rates around 70-75% for basic POS tagging, but turns out significantly lower accuracy rates for more complex tasks like dependency parsing (see Appendix). The pretrained model shows more promising results. By pretraining the tok2vec component on the larger unannotated corpus, we get notable improvements, with POS tagging accuracy increasing to 85-90% and dependency parsing displaying higher accuracy, around 75-80% (see Appendix). The third model, implementing a transformer-based architecture using MobileBERT, constitutes an attempt to leverage advances in neural language models for historical language processing. This model seemed promising as it might capture long-range relations and dependencies blurred by the flexible word order of Old English, but it was hampered by the limited size of the training corpus (see Appendix).

The accuracy metrics show interesting patterns across the three models. Sentence boundary detection turns out comparatively low metrics, probably due to the inconsistent punctuation patterns characteristic of Old English texts. Dependency parsing presents more variable results, although the pretrained model performs better across all corpus sizes. In POS tagging, accuracy improves with larger training sets, but the rate of improvement decreases significantly after the 10,000-word mark. Loss tracking during training revealed quick initial improvements followed by diminishing returns, particularly evident in the larger corpus sizes.

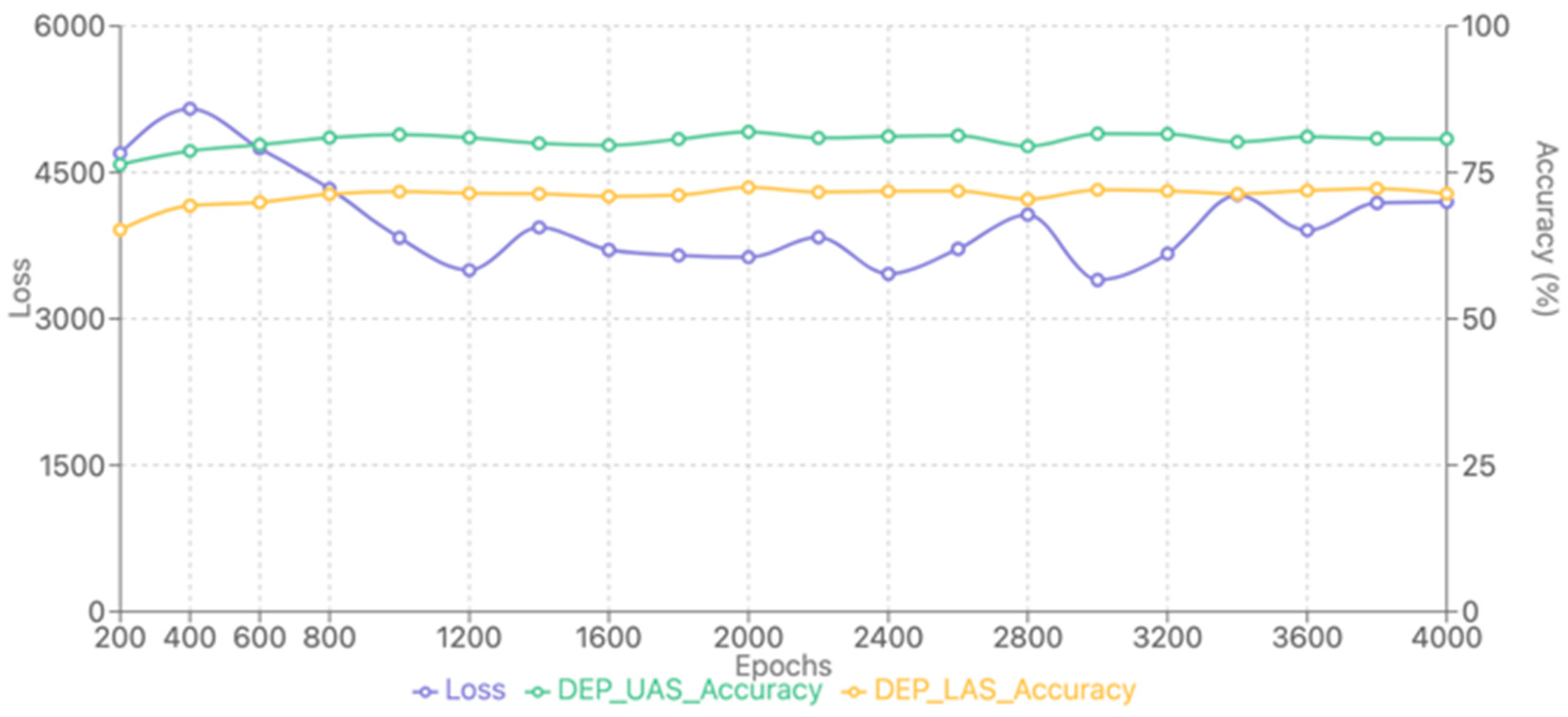

Figure 2 illustrates the learning dynamics of the model. The results correspond to the best performing architecture (pretrained model) and dataset (20,000 words).

As can be seen in

Figure 3, there is clear convergence and consistent performance across key metrics, including loss, UAS and LAS. To begin with, the loss sharply decreases initially. This is indicative of rapid improvement in the optimisation of the model during the early training phase. By approximately 2,000 iterations, the loss stabilizes. This demonstrates that the model has converged to a steady state with minimal further improvement in optimisation. At the same time, both UAS and LAS increase rapidly during the initial iterations, which also reflects substantial gains in the accuracy for syntactic parsing. While UAS consistently outperforms LAS, both metrics stabilise at approximately 60% and 70%, respectively. The existence of this plateau is telling us that the ability of the model to assign correct dependencies and labels has reached its peak performance with the architecture and the dataset selected.

4. Discussion

This section discusses our Old English parsing results from three angles: comparative performance, dataset scaling effects, and computational efficiency. First, we contextualise our findings against modern NLP benchmarks and compare them with Villa and Giarda´s (2023) recent work on Old English dependency parsing. This comparison examines methodological differences in data selection, learning approaches, and performance outcomes. Second, we analyse how increasing dataset size affects parsing accuracy across different model architectures, thus identifying optimal data thresholds and diminishing returns. Finally, we assess the computational requirements of each model architecture, providing a cost-benefit analysis that balances performance gains against resource consumption.

We address the question of compared performance metrics in the first place. The current state-of-the-art in POS tagging reaches 97-98% accuracy across most languages (Wang 2021), while up-to-date morphological analyzers show an accuracy of 90-92% for morphologically rich languages (Şahin 2020). Modern lemmatizers typically reach 95-97% accuracy (Kanerva 2020) and sentence segmentation systems present F1-scores of 95% (Agustyniak 2020). The dependency parsing of natural languages achieves UAS scores of 95-97% and LAS scores of 93-95% (Ahmad 2023).

In the processing of a historical language like Old English the results obtained so far do not reach the standards of natural languages for the reasons mentioned above. A relevant contribution to this field so far has been recently published by Villa and Giarda (2023), who also explore the methodologies of parsing Old English within the UD framework, although their work differs significantly from the present study as to dataset construction, training methodologies, and syntactic analysis. Beginning with datasets, Villa and Giarda’s work focuses on a small, manually annotated dataset derived from two religious prose texts: Adrian and Ritheus and Ælfric’s Supplemental Homilies. Their corpus comprises 292 sentences (5,315 tokens) converted from the YCOE into CoNLL-U format. To compensate for data scarcity, they employed cross-lingual transfer learning, training UUParser v2.4 on combinations of Old English data and treebanks from three modern Germanic languages. The authors reduced support language treebanks to 60k tokens to avoid bias from larger datasets. In contrast, this study uses a larger and more diverse dataset (25k words) sourced from multiple Old English texts, including chronicles, as well as historical, religious, legal and biblical texts. Unlike Villa and Giarda, this study trains models from scratch using spaCy pipelines and tests them.

Turning to learning methods and training approaches, Villa and Giarda’s methodology involved multilingual transfer learning, which is based on the hypothesis that the structural similarities of related languages can improve parsing accuracy. Villa and Giarda trained their models on Old English alone and in combination with Icelandic, German, and Swedish, both individually and collectively. Their best-performing model combined Old English with Icelandic (UAS 68.44%, LAS 58.70%), likely due to Icelandic’s conservative morpho-syntax (comprising case marking as well as V2 syntax) and distinctive graphemes (<æ/Æ> and <ð/Ð>). However, they observed diminishing returns when adding German or Swedish, which they attributed to syntactic divergences (like rigid SVO order in Swedish vs. relative flexibility in Old English). Notably, their monolingual Old English model underperformed (UAS 60.79%, LAS 47.23%).

This study gives priority to monolingual pretraining and dataset size. The pretrained model presented in this study achieves the highest scores (UAS 83.24%, LAS 74.23% with 20k words) and outperforms the MobileBERT transformer, which struggles as consequence of the lexical and graphemic differences between Old English and Present-Day English. Villa and Giarda’s lower overall scores (maximal LAS 58.70%) likely stem from their smaller training data and the heterogeneity of their support languages. By contrast, the larger dataset selected for this study enables better generalisation, particularly for morphosyntactic features like case (80.1% accuracy) and tense (83.8%). The models used in this study excel at local dependencies including, for example, possessive determiners (90.4% accuracy) but often fail to capture long-distance relations like clausal complements (25.5% accuracy). Villa and Giarda (2023) as well as this study show a consistent gap between UAS and LAS, which reflects the difficulty of labeling dependency relations compared to identifying head-dependent attachments. Villa and Giarda’s best model (Icelandic+Old English) achieved a 9.74-point gap (UAS 68.44% vs. LAS 58.70%), while the pretrained model of this study returns a 9.01-point difference (UAS 83.24% vs. LAS 74.23%).

Both studies identify non-projective dependencies as a major issue of automatic parsing. Villa and Giarda highlight discontinuous constituents, particularly in relative clauses, where the antecedent and relative pronoun are separated by adjuncts. This study reports 0% accuracy on non-projective structures, such as relative clauses, clausal modifiers, and conjunctions. These shortcomings can be attributed to the variable word order of Old English, which gives rise to crossing dependencies that are not compatible with transition-based parsing algorithms (Martin and Jurafsky 2020: 284).

We examine the question of the impact of dataset sizes now. Across all training methods, a clear correlation between dataset size and parsing accuracy emerges, though with important differences as far as learning patterns and efficiency are concerned. The relationship between dataset size and parsing accuracy follows a non-linear pattern with diminishing returns. The most remarkable improvements occur in the transition from 1,000 to 5,000 words, with the baseline model showing gains of +11.61% UAS and +25.85% LAS. The pretrained model, which starts from a higher baseline, achieves significant improvements of +7.99% UAS and +28.49% LAS. Subsequent increases from 5,000 to 10,000 words and from 10,000 to 20,000 words yield smaller improvements. The rate of improvement does not plateau even at 20,000 words, which suggests that the limit of useful training data has not yet been reached.

The three models tested in this study demonstrate different scaling characteristics. The pretrained model outperforms the alternatives at all dataset sizes, as it achieves 83.24% UAS and 74.23% LAS with 20,000 words. This architecture also shows better data efficiency because it reaches higher accuracy levels with smaller datasets than the baseline model for comparable performance. In contrast, the transformer-based approach consistently underperforms, reaching only 60.17% UAS and 45.51% LAS even with the largest dataset. The poor scaling efficiency of the transformer model may be put down to its larger parameter space, which cannot be adequately trained with limited historical language data.

Different annotation tasks exhibit distinct learning trajectories across dataset sizes. POS tagging and morphological feature recognition reach near-optimal performance relatively quickly, in such a way that the pretrained model achieves over 90% accuracy for POS tagging at just 5,000 words. These tasks benefit from the relatively closed sets of possible tags and the strong correlation between word form and morphological features in Old English. Dependency parsing continues to improve substantially across all dataset increments.

This assessment raises two further questions. Firstly, is the advantage of the pretrained model consistent across all tasks, or driven by exceptional performance on just a few metrics? And, secondly, does the transformer model struggle uniformly on all tasks, or is its weak overall performance primarily driven by specific metrics? This could explain which tasks benefit most from pretraining, where the simple baseline model may be adequate for getting similar results and at what dataset sizes architectural differences become more important.

To answer the question on the consistency of the advantage of the pretrained model´s performance, we analyse the performance gap between the pretrained model and the baseline model across all metrics at the 20K dataset size. The results are tabulated in

Table 2.

As is shown in

Table 2, the advantage of the pretrained model is not uniform across all tasks. The largest advantages are in dependency parsing metrics (LAS +6.13pp, UAS +4.98pp). The pretrained model actually performs slightly worse on lemmatization (-0.08pp) and its advantage is minimal for sentence segmentation (+0.81pp). It seems to be the case that the pretrained model overall advantage is a consequence of its strong performance in syntactic tasks, particularly dependency parsing.

In order to answer the question on the uniformity of the struggle of the transformer model across tasks, we compare the transformer model to the baseline model at the 20K dataset size. The results are displayed in

Table 3.

As can be seen in

Table 3, the underperformance of the transformer model is non-uniform across tasks. Its worst result is on sentence segmentation (SENT-F), at only 56.8% of the baseline model’s performance. Dependency parsing shows the deepest gap (LAS at 66.8% of the baseline model), while POS tagging shows the smallest difference (88.1% of the baseline model). The weak overall results of the transformer model, therefore, seem to be a direct consequence of its performance on syntactic parsing and sentence segmentation.

Table 4 shows the standard deviations across metrics for the mean accuracy.

As is presented in

Table 4, all models become more consistent as dataset size increases because standard deviations decrease. This indicates that more data not only improves performance but also makes performance more uniform across tasks. The transformer model has the highest standard deviations at larger dataset sizes. This highlights an uneven performance across tasks even with more data. This is in contradistinction to the pretrained model, which has the lowest standard deviations at the largest dataset size, which suggests that it achieves the most balanced performance across all metrics.

These remarks on the impact of dataset sizes add a new perspective to the main takeaway of this study, which underlines the adequacy for Old English parsing of the architecture based on the spaCy-based pipeline with pretraining on raw text. However, computational costs represent a crucial consideration alongside performance metrics when evaluating NLP architectures (Rae et al. 2021; Ding et al., 2023). As a matter of fact, the three architectures under analysis have profiles that require different computational resources. They are illustrated with respect to the 20,000-word dataset in

Table 5.

The comparative analysis of the three models on the 20,000-word dataset presents distinct trade-offs between performance, resources, and practicality. The pretrained model delivers the highest overall accuracy and requires moderately increased computational resources (1-2× training time, 2× cloud computing costs). This improvement is particularly pronounced in syntactic tasks. The baseline model offers excelent efficiency because it consumes minimal resources but achieves solid performance (79.88% average), making it the most accessible option for resource-constrained environments. This is in contrast to the transformer model, which clearly underperforms both alternatives (62.30% average, 17.58 percentage points below baseline) despite demanding higher computational resources (5-10× longer training time, 70-90% slower inference).

For future applications, the pretrained approach represents the optimal balance between accuracy and efficiency for most tasks, particularly when both performance and computational viability matter. However, the strong performance-to-cost ratio of the baseline model makes it an attractive alternative, especially for basic NLP tasks with limited resources. This advantage becomes even more outstanding when working with larger datasets, where simpler models with sufficient data can approach the performance of more complex models. For under-resourced languages or strict computational constraints, the simpler pipeline might be preferable despite its slightly lower accuracy. The transformer model´s combination of poor performance and high resource demands makes it unsuitable for this particular NLP task.

5. Conclusions

This study provides insights into the automatic parsing of Old English within the UD framework. Through comprehensive evaluation of three pipeline architectures across four dataset sizes, we have identified effective approaches for processing historical language data.

The pretrained model consistently delivers superior performance. It achieves 82.72% mean accuracy across all metrics with the largest dataset. This architecture excels particularly in syntactic tasks, with improvements of 6.13 and 4.98 percentage points in LAS and UAS respectively compared to the baseline model. The baseline model offers reasonable performance (79.88% mean accuracy) with minimal computational demands. This makes it suitable for resource-constrained environments. However, the transformer-based model significantly underperforms (62.30% mean accuracy) despite requiring more computational resources.

Our analysis of dataset impact shows that while larger training sets consistently improve performance, the relationship follows a non-linear pattern with diminishing returns. The most substantial gains occur when expanding from 1,000 to 5,000 words, whereas beyond this threshold improvements are modest. Nevertheless, even at 20,000 words, the learning curve has not plateaued completely, which suggests that additional training data could yield further improvements.

The computational cost analysis points to relevant relations between model complexity, resource requirements, and performance. The pretrained model represents the optimal balance because it delivers the highest accuracy with moderate resource demands. For applications where computational efficiency is important, the baseline model offers an excellent alternative with acceptable performance.

Overall, our findings demonstrate that medium-complexity architectures with pretraining on raw text currently provide the best approach for automated analysis of Old English dependencies, as they outperform both simpler baselines and more complex transformer-based models.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.A.; methodology, J.M.A. and A.E.O.L.; formal analysis, A.E.O.L. and S.D.B.; investigation, J.M.A, A.E.O.L., and S.D.B.; data curation, S.D.B.; writing—original draft preparation, S.D.B.; writing—review and editing, J.M.A. and A.E.O.L.; visualization, S.D.B.; supervision, J.M.A and A.E.O.L.; project administration, J.M.A.; funding acquisition, J.M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by AEI /10.13039/501100011033, grant number PID2023149762NB-100MCIN.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LAS |

Labelled Attachment Score |

| NLP |

Natural Language Processing |

| UAS |

Unlabelled Attachment Score |

| UD |

Universal Dependencies |

Appendix

The appendix presents a summary table and performance charts by component.

Summary table

| Model |

Dataset |

Metrics (%) |

Mean |

| |

|

XPOS |

UPOS |

FEATS |

LEMMA |

UAS |

LAS |

SENT-F |

|

| Baseline |

1000 |

75.75 |

74.79 |

58.96 |

54.39 |

57.44 |

27.32 |

48.07 |

56.67 |

| Baseline |

5000 |

84.98 |

84.98 |

71.40 |

68.95 |

69.05 |

53.17 |

56.22 |

69.82 |

| Baseline |

10000 |

87.88 |

87.66 |

75.95 |

73.90 |

73.76 |

60.95 |

62.81 |

74.70 |

| Baseline |

20000 |

90.66 |

90.64 |

81.00 |

79.91 |

78.26 |

68.10 |

70.57 |

79.88 |

| Pre-trained |

1000 |

86.44 |

85.55 |

70.39 |

55.35 |

68.48 |

34.19 |

43.74 |

63.45 |

| Pre-trained |

5000 |

90.46 |

90.10 |

78.14 |

69.45 |

76.47 |

62.68 |

63.12 |

75.77 |

| Pre-trained |

10000 |

91.84 |

91.62 |

80.82 |

74.28 |

80.07 |

69.10 |

65.27 |

79.00 |

| Pre-trained |

20000 |

93.20 |

92.96 |

84.21 |

79.83 |

83.24 |

74.23 |

71.38 |

82.72 |

| Transformer |

1000 |

52.47 |

52.99 |

39.13 |

37.02 |

42.78 |

14.47 |

14.96 |

36.26 |

| Transformer |

5000 |

75.60 |

75.81 |

59.45 |

61.36 |

50.42 |

29.84 |

30.14 |

54.66 |

| Transformer |

10000 |

75.60 |

75.81 |

59.45 |

61.36 |

55.58 |

38.83 |

30.56 |

56.74 |

| Transformer |

20000 |

79.91 |

79.89 |

64.95 |

65.58 |

60.17 |

45.51 |

40.07 |

62.30 |

Performance by component

References

- Ahmad, W. U., Peng, H., & Chang, K.-W. (2023). COLT5: Faster long-range transformers with conditional computation. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers) (pp. 11588–11608). Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Allen, C. (2008). Genitives in Early English: Typology and Evidence (pp. 1-332). Oxford University Press.

- Augustyniak, Ł., Morzy, M., Kajdanowicz, T., Kazienko, P., Dąbrowski, M., & Żelasko, P. (2020). Punctuation prediction model for conversational speech. In Proceedings of Interspeech 2020 (pp. 4911-4915). ISCA.

- Campbell, A. 1987. Old English Grammar. Oxford University Press.

- de Marneffe, Marie-Catherine and Christopher D. Manning. 2008. Stanford typed dependencies manual. Technical report, Stanford University.

- de Marneffe, Marie-Catherine, Christopher Manning, Joakim Nivre, and Daniel Zeman. 2021. Universal Dependencies. Computational Linguistics, 47(2):255-308.

- de Marneffe, Marie-Catherine, Timothy Dozat, Natalia Silveira, Katri Haverinen, Filip Ginter, Joakim Nivre, and Christopher Manning. 2014. Universal Stanford Dependencies: A cross-linguistic typology. In Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC'14), pages 4585-4592.

- Jurafsky, Dan, and James H. Martin. 2020. Speech and Language Processing: An Introduction to Natural Language Processing, Computational Linguistics and Speech Recognition, 2nd edition. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

- Fischer, Olga, Ans van Kemenade, Willem Koopman, and Wim van der Wurff. 2000. The Syntax of Early English. Cambridge University Press.

- Haeberli, E., & Pintzuk, S. (2006). Revisiting verb (projection) raising in Old English. York Papers in Linguistics Series 2, 6, 77–94.

- Healey, Antonette diPaolo, John Price Wilkin, and Xin Xiang. 2004. The Dictionary of Old English Web Corpus. Dictionary of Old English Project, Centre for Medieval Studies, University of Toronto.

- Kanerva, J., Ginter, F., & Salakoski, T. (2020). Universal Lemmatizer: A sequence-to-sequence model for lemmatizing Universal Dependencies treebanks. Natural Language Engineering, 26(2), 205-233. [CrossRef]

- Kastovsky, Dieter. 1992. Semantics and Vocabulary. In Richard M. Hogg, editor, The Cambridge History of the English Language 1, pages 290-408. Cambridge University Press.

- Koopman, W. F. (1995). Verb-final main clauses in Old English prose. Studia Neophilologica, 67(1), 129–144.

- Koopman, W. (2005). Transitional syntax: Postverbal pronouns and particles in Old English. English Language and Linguistics, 9(1), 47–62. [CrossRef]

- Kroch, A., & Taylor, A. (2000). Verb-object order in Early Middle English. In S. Pintzuk, G. Tsoulas, & A. Warner (Eds.), Diachronic syntax: Models and mechanisms (pp. 132–160). Oxford University Press.

- Kübler, Sandra, Ryan McDonald, and Joakim Nivre. 2009. Dependency Parsing. Synthesis Lectures on Human Language Technologies. Morgan & Claypool Publishers.

- Manning, Christopher D. 2011. Part-of-speech tagging from 97% to 100%: Is it time for some linguistics? In Alexander F. Gelbukh, editor, Computational Linguistics and Intelligent Text Processing, pages 171-189. Springer.

- Martín Arista, Javier (ed.), Sara Domínguez Barragán, Luisa Fidalgo Allo, Laura García Fernández, Yosra Hamdoun Bghiyel, Miguel Lacalle Palacios, Raquel Mateo Mendaza, Carmen Novo Urraca, Ana Elvira Ojanguren López, Esaúl Ruíz Narbona, Roberto Torre Alonso and Raquel Vea Escarza. 2023. ParCorOEv3. An open access annotated parallel corpus Old English-English. Nerthus Project, Universidad de La Rioja, www.nerthusproject.com.

- Martín Arista, Javier. 2022a. Old English Universal Dependencies: Categories, Functions and Specific Fields. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART 2022), volume 3, pages 945-951.

- Martín Arista, Javier. 2022b. Toward the morpho-syntactic annotation of an Old English corpus with Universal Dependencies. Revista de Lingüística y Lenguas Aplicadas, 17:85-97.

- Martín Arista, Javier. 2024. Toward a Universal Dependencies Treebank of Old English: Representing the Morphological Relatedness of Un-Derivatives. Languages, 9(3):76.

- Middeke, K. (2022). The Old English Case System: Case and Argument Structure Constructions. Brill.

- Nivre, Joakim, Johan Hall, Jens Nilsson, Atanas Chanev, Gülşen Eryigit, Sandra Kübler, Svetoslav Marinov, and Erwin Marsi. 2007. MaltParser: A language-independent system for data-driven dependency parsing. Natural Language Engineering, 13(2):95-135. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).