Submitted:

28 May 2025

Posted:

29 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

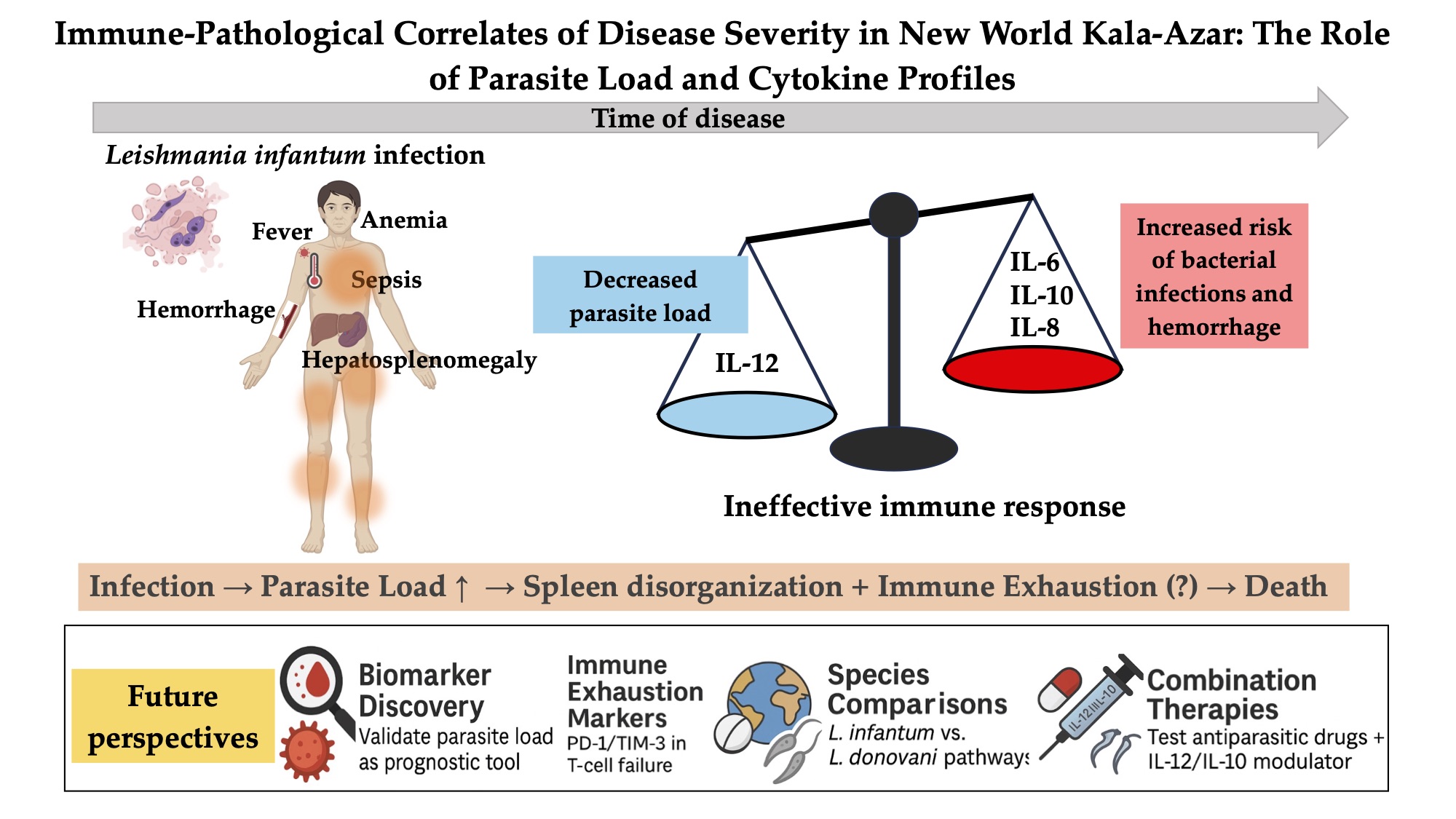

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Medical Data

2.3. DNA Isolation, Purity, and Standardization

2.4. Quantitative PCR

2.5. Plasma Cytokines

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.2. Clinical Findings

3.3. Quantity of Parasite Load and Cytokines

3.4. Blood and Bone Marrow L. infantum Load

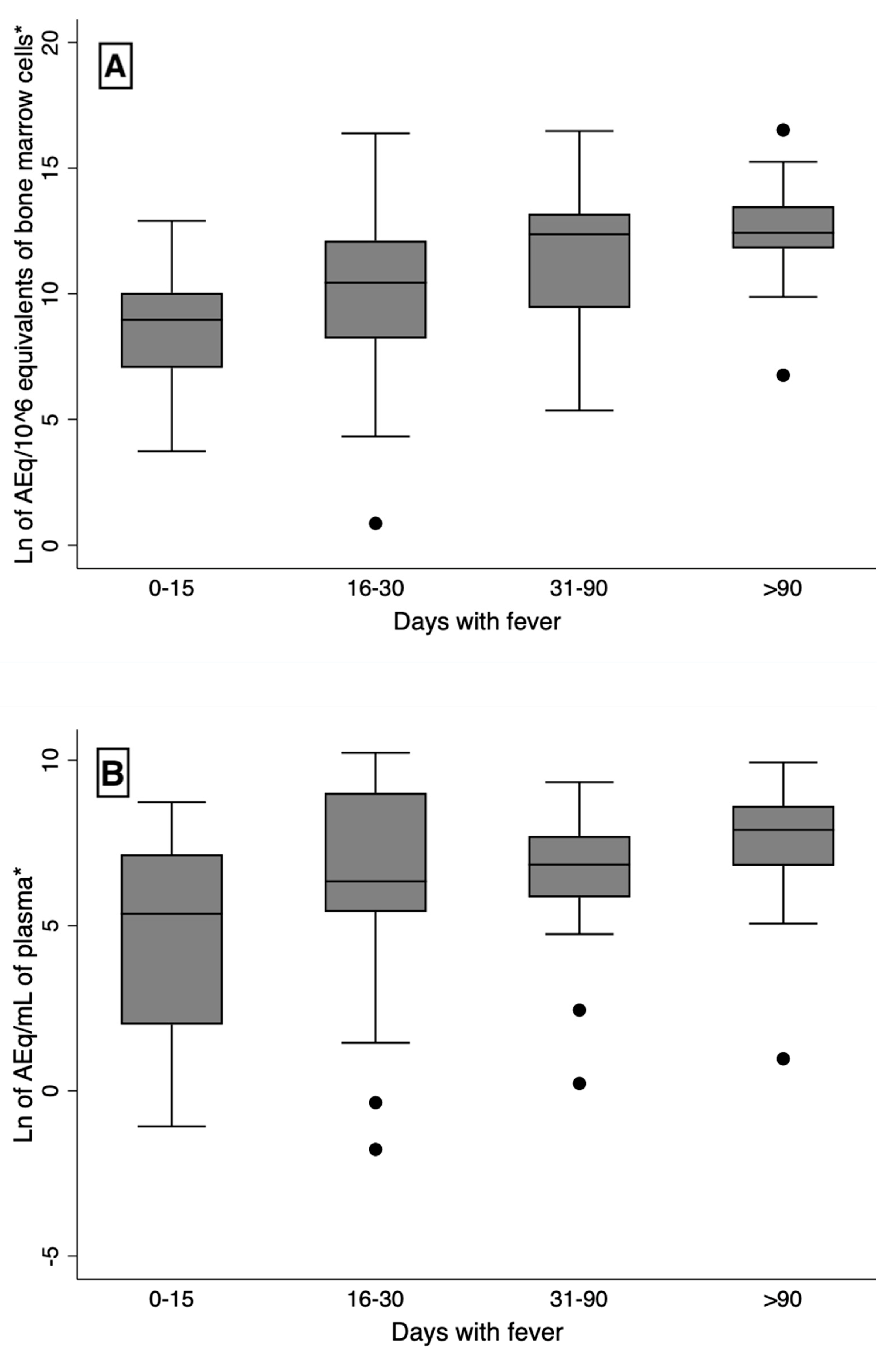

3.5. Time of Disease, Blood and Bone Marrow L. infantum Load, Plasma Cytokines, and Severity

3.6. Blood and Bone Marrow L. infantum Load, Age, Sex, HIV Infection, and Kala-Azar Severity

3.7. Plasma Cytokines, Age, Sex, HIV Infection, and Markers of Kala-Azar Severity

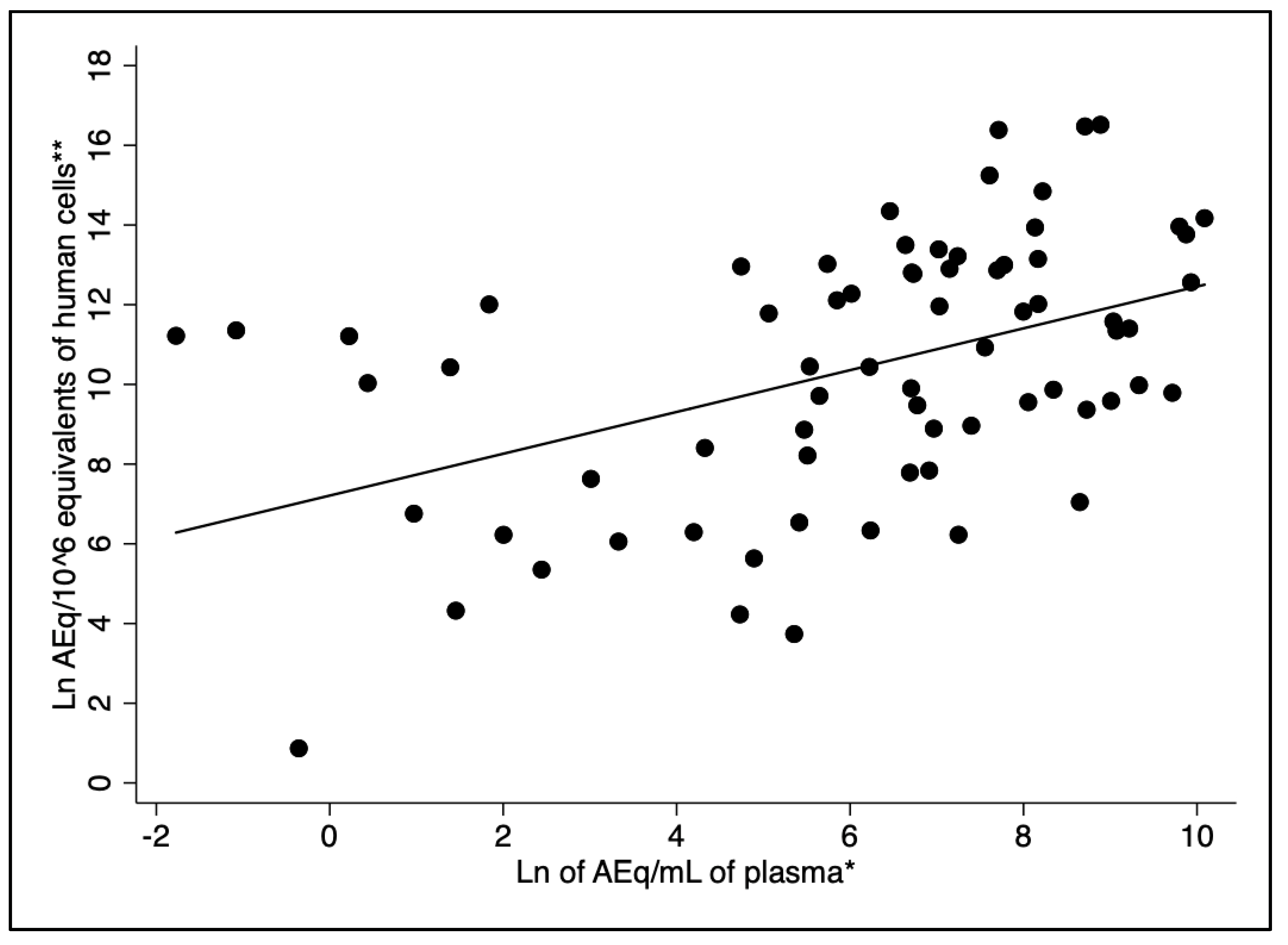

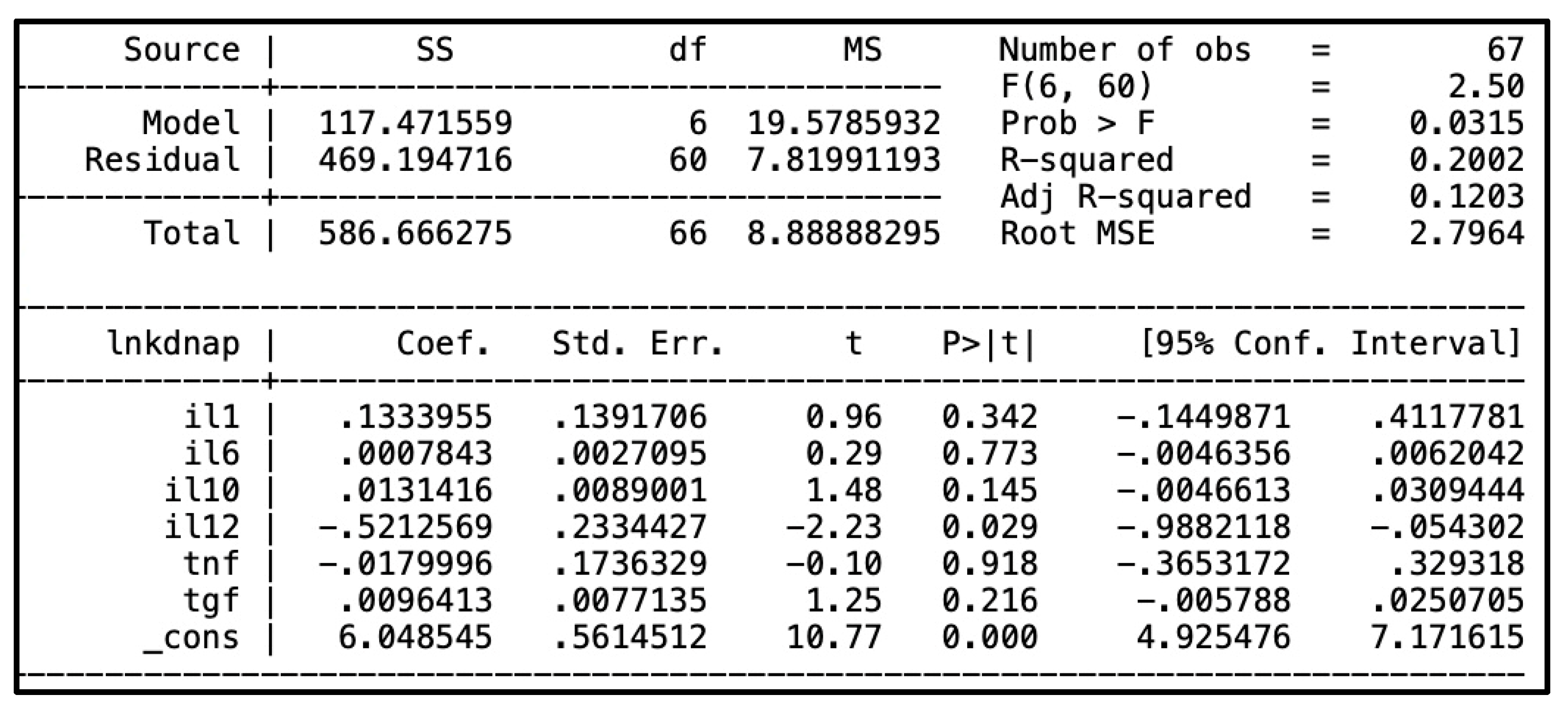

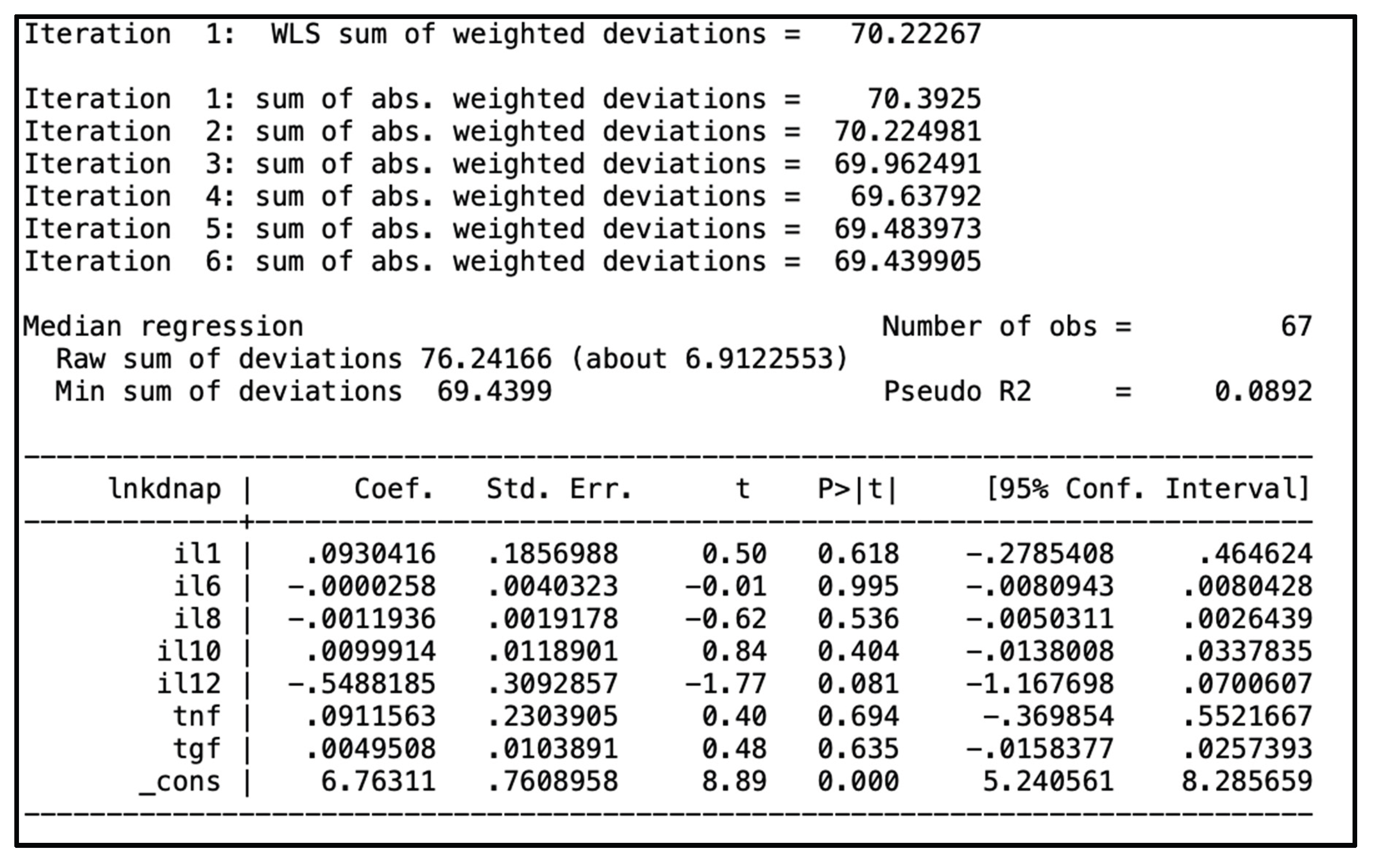

3.8. Regression Analysis Between L. infantum Load and Plasma Cytokines

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Burza S, Croft SL, Boelaert M. Leishmaniasis. Lancet. 2018 Sep;392(10151):951–70.

- Andrade TM, Carvalho EM, Rocha H. Bacterial Infections in Patients with Visceral Leishmaniasis. J Infect Dis. 1990 Dec 1;162(6):1354–9.

- Costa CHN, Werneck GL, Costa DL, Holanda TA, Aguiar GB, Carvalho AS, et al. Is severe visceral leishmaniasis a systemic inflammatory response syndrome? A case control study. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2010 Aug;43(4):386–92. 86822010000400010&lng=en&tlng=en.

- Sampaio MJA de Q, Cavalcanti NV, Alves JGB, Fernandes Filho MJC, Correia JB. Risk Factors for Death in Children with Visceral Leishmaniasis. Franco-Paredes C, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010 Nov 2;4(11):e877.

- Costa DL, Rocha RL, Chaves E de BF, Batista VG de V, Costa HL, Costa CHN. Predicting death from kala-azar: construction, development, and validation of a score set and accompanying software. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2016 Dec;49(6):728–40.

- Akuffo H, Costa C, van Griensven J, Burza S, Moreno J, Herrero M. New insights into leishmaniasis in the immunosuppressed. Rafati S, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis . 2018 May 10;12(5):e0006375.

- Kurizky PS, Marianelli FF, Cesetti MV, Damiani G, Sampaio RNR, Gonçalves LMT, et al. A comprehensive systematic review of leishmaniasis in patients undergoing drug-induced immunosuppression for the treatment of dermatological, rheumatological and gastroenterological diseases. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2020;62.

- Rahim S, Karim MM. The Elimination Status of Visceral Leishmaniasis in Southeast Asia Region. Acta Parasitol. 2024 Sep 20;69(3):1704–16.

- da Rocha ICM, dos Santos LHM, Coura-Vital W, da Cunha GMR, Magalhães F do C, da Silva TAM, et al. Effectiveness of the Brazilian Visceral Leishmaniasis Surveillance and Control Programme in reducing the prevalence and incidence of Leishmania infantum infection. Parasit Vectors. 2018 Dec 12;11(1):586.

- McCall LI, Zhang WW, Matlashewski G. Determinants for the Development of Visceral Leishmaniasis Disease. Chitnis CE, editor. PLoS Pathog. 2013 Jan 3;9(1):e1003053.

- Volpedo G, Pacheco-Fernandez T, Bhattacharya P, Oljuskin T, Dey R, Gannavaram S, et al. Determinants of Innate Immunity in Visceral Leishmaniasis and Their Implication in Vaccine Development. Front Immunol. 2021 Oct 12;12.

- Bogdan C, Islam NAK, Barinberg D, Soulat D, Schleicher U, Rai B. The immunomicrotope of Leishmania control and persistence. Trends Parasitol. 2024 Sep;40(9):788–804.

- Silva JC, Zacarias DA, Silva VC, Rolão N, Costa DL, Costa CH. Comparison of optical microscopy and quantitative polymerase chain reaction for estimating parasitaemia in patients with kala-azar and modelling infectiousness to the vector Lutzomyia longipalpis. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2016 Jul 18;111(8):517–22.

- Ferreira GR, Santos-Oliveira JR, Silva-Freitas ML, Honda M, Costa DL, Da-Cruz AM, et al. Biomarkers of disease severity in patients with visceral leishmaniasis co-infected with HIV. Cytokine. 2022 Jan;149:155747.

- Al-Khalaifah, HS. Major Molecular Factors Related to Leishmania Pathogenicity. Front Immunol. 2022 Jun 13;13.

- Samant M, Sahu U, Pandey SC, Khare P. Role of Cytokines in Experimental and Human Visceral Leishmaniasis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021 Feb 18;11.

- Costa DL, Rocha RL, Carvalho RMA, Lima-Neto AS, Harhay MO, Costa CHN, et al. Serum cytokines associated with severity and complications of kala-azar. Pathog Glob Health. 2013 Mar 12;107(2):78–87.

- Costa CHN, Chang KP, Costa DL, Cunha FVM. From Infection to Death: An Overview of the Pathogenesis of Visceral Leishmaniasis. Pathogens. 2023 Jul 24;12(7):969.

- dos Santos PL, de Oliveira FA, Santos MLB, Cunha LCS, Lino MTB, de Oliveira MFS, et al. The Severity of Visceral Leishmaniasis Correlates with Elevated Levels of Serum IL-6, IL-27 and sCD14. Oliveira SC, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016 Jan 27;10(1):e0004375.

- Silva JM, Zacarias DA, de Figueirêdo LC, Soares MRA, Ishikawa EAY, Costa DL, et al. Bone Marrow Parasite Burden among Patients with New World Kala-Azar is Associated with Disease Severity. Am Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2014 Apr 2;90(4):621–6.

- Zacarias DA, Rolão N, de Pinho FA, Sene I, Silva JC, Pereira TC, et al. Causes and consequences of higher Leishmania infantum burden in patients with kala-azar: a study of 625 patients. Trop Med Int Heal. 2017 Jun 2;22(6):679–87.

- Grace CA, Sousa Carvalho KS, Sousa Lima MI, Costa Silva V, Reis-Cunha JL, Brune MJ, et al. Parasite Genotype Is a Major Predictor of Mortality from Visceral Leishmaniasis. Weiss LM, editor. MBio. 2022 Dec 20;13(6).

- Cota G, Erber AC, Schernhammer E, Simões TC. Inequalities of visceral leishmaniasis case-fatality in Brazil: A multilevel modeling considering space, time, individual and contextual factors. Ramos AN, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021 Jul 1;15(7):e0009567.

- Kildey K, Rooks K, Weier S, Flower RL, Dean MM. Effect of age, gender and mannose-binding lectin (MBL) status on the inflammatory profile in peripheral blood plasma of Australian blood donors. Hum Immunol. 2014 Sep;75(9):973–9.

- Porcino GN, Carvalho KSS, Braz DC, Costa Silva V, Costa CHN, de Miranda Santos IKF. Evaluation of methods for detection of asymptomatic individuals infected with Leishmania infantum in the state of Piauí, Brazil. Rafati S, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019 Jul 1;13(7):e0007493.

- Das VNR, Bimal S, Siddiqui NA, Kumar A, Pandey K, Sinha SK, et al. Conversion of asymptomatic infection to symptomatic visceral leishmaniasis: A study of possible immunological markers. Brodskyn CI, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020 Jun 18;14(6):e0008272.

- Chakravarty J, Hasker E, Kansal S, Singh OP, Malaviya P, Singh AK, et al. Determinants for progression from asymptomatic infection to symptomatic visceral leishmaniasis: A cohort study. Franco-Paredes C, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019 Mar 27;13(3):e0007216.

- Virginia Batista Vieira A, Farias PCS, Silva Nunes Bezerra G, Xavier AT, Sebastião Da Costa Lima Júnior M, Silva ED Da, et al. Evaluation of molecular techniques to visceral leishmaniasis detection in asymptomatic patients: a systematic review. Expert Rev Mol Diagn . 2021 May 4;21(5):493–504.

- Harhay MO, Olliaro PL, Vaillant M, Chappuis F, Lima MA, Ritmeijer K, et al. Who Is a Typical Patient with Visceral Leishmaniasis? Characterizing the Demographic and Nutritional Profile of Patients in Brazil, East Africa, and South Asia. Am Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2011 Apr 5;84(4):543–50.

- Leite de Sousa-Gomes M, Romero GAS, Werneck GL. Visceral leishmaniasis and HIV/AIDS in Brazil: Are we aware enough? Gradoni L, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017 Sep 25;11(9):e0005772.

- Machado CAL, Sevá A da P, Silva AAFA e, Horta MC. Epidemiological profile and lethality of visceral leishmaniasis/human immunodeficiency virus co-infection in an endemic area in Northeast Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop . 2021;54. 86822021000100316&tlng=en.

- Hailu A, van der Poll T, Berhe N, Kager PA. Elevated plasma levels of interferon (IFN)-gamma, IFN-gamma inducing cytokines, and IFN-gamma inducible CXC chemokines in visceral leishmaniasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004 Nov;71(5):561–7.

- Peruhype-Magalhães V, Martins-Filho OA, Prata A, Silva LDA, Rabello A, Teixeira-Carvalho A, et al. Mixed inflammatory/regulatory cytokine profile marked by simultaneous raise of interferon-γ and interleukin-10 and low frequency of tumour necrosis factor-α+ monocytes are hallmarks of active human visceral Leishmaniasis due to Leishmania chagasi infectio. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006 Aug 25;146(1):124–32.

- Ansari NA, Saluja S, Salotra P. Elevated levels of interferon-γ, interleukin-10, and interleukin-6 during active disease in Indian kala azar. Clin Immunol. 2006 Jun;119(3):339–45.

- van Dijk NJ, Carter J, Kiptanui D, Mens PF, Schallig HDFH. A case–control study on risk factors for visceral leishmaniasis in West Pokot County, Kenya. Trop Med Int Heal. 2024 Oct 4;29(10):904–12.

- Decker ML, Grobusch MP, Ritz N. Influence of Age and Other Factors on Cytokine Expression Profiles in Healthy Children—A Systematic Review. Front Pediatr. 2017 Dec 14;5.

- Ringleb M, Javelle F, Haunhorst S, Bloch W, Fennen L, Baumgart S, et al. Beyond muscles: Investigating immunoregulatory myokines in acute resistance exercise – A systematic review and meta-analysis. FASEB J. 2024 Apr 15;38(7).

- Tasca KI, Correa CR, Caleffi JT, Mendes MB, Gatto M, Manfio VM, et al. Asymptomatic HIV People Present Different Profiles of sCD14, sRAGE, DNA Damage, and Vitamins, according to the Use of cART and CD4 + T Cell Restoration. J Immunol Res. 2018;2018:1–11.

- Guedes DL, Silva ED da, Castro MCAB, Júnior WLB, Ibarra-Meneses AV, Tsoumanis A, et al. Comparison of serum cytokine levels in symptomatic and asymptomatic HIV-Leishmania coinfected individuals from a Brazilian visceral leishmaniasis endemic area. Guizani I, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022 Jun 17;16(6):e0010542.

- Hunter CA, Jones SA. IL-6 as a keystone cytokine in health and disease. Nat Immunol. 2015 May;16(5):448–57.

- Mary C, Faraut F, Lascombe L, Dumon H. Quantification of Leishmania infantum DNA by a Real-Time PCR Assay with High Sensitivity. J Clin Microbiol. 2004 Nov;42(11):5249–55.

- de Araújo Albuquerque LP, da Silva AM, de Araújo Batista FM, de Souza Sene I, Costa DL, Costa CHN. Influence of sex hormones on the immune response to leishmaniasis. Parasite Immunol. 2021 Oct 2;43(10–11).

- Murray HW, Rubin BY, Rothermel CD. Killing of intracellular Leishmania donovani by lymphokine-stimulated human mononuclear phagocytes. Evidence that interferon-gamma is the activating lymphokine. J Clin Invest. 1983 Oct 1;72(4):1506–10.

- Reiner NE, Ng W, Wilson CB, McMaster WR, Burchett SK. Modulation of in vitro monocyte cytokine responses to Leishmania donovani. Interferon-gamma prevents parasite-induced inhibition of interleukin 1 production and primes monocytes to respond to Leishmania by producing both tumor necrosis factor-alpha and in. J Clin Invest. 1990 Jun 1;85(6):1914–24.

- Heinzel FP, Schoenhaut DS, Rerko RM, Rosser LE, Gately MK. Recombinant interleukin 12 cures mice infected with Leishmania major. J Exp Med . 1993 May 1;177(5):1505–9.

- Murray HW, Hariprashad J. Interleukin 12 is effective treatment for an established systemic intracellular infection: experimental visceral leishmaniasis. J Exp Med. 1995 Jan 1;181(1):387–91.

- Ghalib HW, Piuvezam MR, Skeiky YA, Siddig M, Hashim FA, El-Hassan AM, et al. Interleukin 10 production correlates with pathology in human Leishmania donovani infections. J Clin Invest. 1993 Jul 1;92(1):324–9.

- Bacellar O, Brodskyn C, Guerreiro J, Barral-Netto M, Costa CH, Coffman RL, et al. Interleukin-12 Restores Interferon- Production and Cytotoxic Responses in Visceral Leishmaniasis. J Infect Dis. 1996 Jun 1;173(6):1515–8.

- Verma S, Kumar R, Katara GK, Singh LC, Negi NS, Ramesh V, et al. Quantification of Parasite Load in Clinical Samples of Leishmaniasis Patients: IL-10 Level Correlates with Parasite Load in Visceral Leishmaniasis. Rodrigues MM, editor. PLoS One. 2010 Apr 9;5(4):e10107.

- Bhattacharya P, Ghosh S, Ejazi SA, Rahaman M, Pandey K, Ravi Das VN, et al. Induction of IL-10 and TGFβ from CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ T Cells Correlates with Parasite Load in Indian Kala-azar Patients Infected with Leishmania donovani. Bates PA, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016 Feb 1;10(2):e0004422.

- Teles L de F, Viana AG, Cardoso MS, Pinheiro GRG, Bento GA, Lula JF, et al. Evaluation of medullary cytokine expression and clinical and laboratory aspects in severe human visceral leishmaniasis. Parasite Immunol. 2021 Dec 11;43(12).

- Carvalho EM, Badaró R, Reed SG, Jones TC, Johnson WD. Absence of gamma interferon and interleukin 2 production during active visceral leishmaniasis. J Clin Invest. 1985 Dec 1;76(6):2066–9.

- Carvalho EM, Bacellar O, Brownell C, Regis T, Coffman RL, Reed SG. Restoration of IFN-gamma production and lymphocyte proliferation in visceral leishmaniasis. J Immunol. 1994 Jun 15;152(12):5949–56.

- Karp CL, El-Safi SH, Wynn TA, Satti MM, Kordofani AM, Hashim FA, et al. In vivo cytokine profiles in patients with kala-azar. Marked elevation of both interleukin-10 and interferon-gamma. J Clin Invest. 1993 Apr 1;91(4):1644–8.

- Nylén S, Sacks D. Interleukin-10 and the pathogenesis of human visceral leishmaniasis. Trends Immunol. 2007 Sep;28(9):378–84.

- Kany S, Vollrath JT, Relja B. Cytokines in Inflammatory Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Nov 28;20(23):6008.

- Fabri A, Kandara K, Coudereau R, Gossez M, Abraham P, Monard C, et al. Characterization of Circulating IL-10-Producing Cells in Septic Shock Patients: A Proof of Concept Study. Front Immunol. 2021 Feb 4;11.

- D’Oliveira Júnior A, Costa SRM, Bispo Barbosa A, Orge Orge M de LG, Carvalho EM. Asymptomatic Leishmania chagasi Infection in Relatives and Neighbors of Patients with Visceral Leishmaniasis. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1997 Jan;92(1):15–20.

- Lima S, Braz D, Silva V, Farias T, Zacarias DADAADA, Silva JC, et al. Biomarkers of the early response to treatment of visceral leishmaniasis: A prospective cohort study. Parasite Immunol. 2021 Jan 20;43(1).

- Saraiva M, Vieira P, O’Garra A. Biology and therapeutic potential of interleukin-10. J Exp Med. 2020 Jan 6;217(1).

- Munk RB, Sugiyama K, Ghosh P, Sasaki CY, Rezanka L, Banerjee K, et al. Antigen-Independent IFN-γ Production by Human Naïve CD4+ T Cells Activated by IL-12 Plus IL-18. Klinman D, editor. PLoS One . 2011 May 10;6(5):e18553.

- Lee HG, Cho MJ, Choi JM. Author Correction: Bystander CD4+ T cells: crossroads between innate and adaptive immunity. Exp Mol Med. 2023 Jun 8;55(6):1275–1275.

- Reis-Cunha JL, Grace CA, Ahmed S, Harnqvist SE, Lynch CM, Boité MC, et al. The global dispersal of visceral leishmaniasis occurred within human history . 2024.

- Zijlstra, EE. The immunology of post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL). Parasit Vectors. 2016 Dec 23;9(1):464.

- Jarczak D, Nierhaus A. Cytokine Storm—Definition, Causes, and Implications. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Oct 3;23(19):11740.

- Miller CHT, Maher SG, Young HA. Clinical Use of Interferon-γ. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009 Dec 14;1182(1):69–79.

- Baessler A, Vignali DAA. T Cell Exhaustion. Annu Rev Immunol. 2024 Jun 28;42(1):179–206.

- Sonar SA, Watanabe M, Nikolich JŽ. Disorganization of secondary lymphoid organs and dyscoordination of chemokine secretion as key contributors to immune aging. Semin Immunol. 2023 Nov;70:101835.

- Gautam S, Kumar R, Singh N, Singh AK, Rai M, Sacks D, et al. CD8 T Cell Exhaustion in Human Visceral Leishmaniasis. J Infect Dis. 2014 Jan 15;209(2):290–9.

- Silva-O’Hare J, de Oliveira IS, Klevorn T, Almeida VA, Oliveira GGS, Atta AM, et al. Disruption of Splenic Lymphoid Tissue and Plasmacytosis in Canine Visceral Leishmaniasis: Changes in Homing and Survival of Plasma Cells. Khan WN, editor. PLoS One . 2016 May 31;11(5):e0156733.

- Hermida M d’El R, de Melo CVB, Lima I dos S, Oliveira GG de S, Dos-Santos WLC. Histological Disorganization of Spleen Compartments and Severe Visceral Leishmaniasis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018 Nov 13;8.

- de Souza TL, da Silva AVA, Pereira L de OR, Figueiredo FB, Mendes Junior AAV, Menezes RC, et al. Pro-Cellular Exhaustion Markers are Associated with Splenic Microarchitecture Disorganization and Parasite Load in Dogs with Visceral Leishmaniasis. Sci Rep. 2019 Sep 10;9(1):12962.

| Characteristic | Number (%) | 95% CI1 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 42 (58.3) | 46.1; 69.85 |

| Female | 30 (41.7) | 30.2; 53.89 |

| Age groups (Years) | ||

| <2 | 17 (23.6) | 14.0; 35.0 |

| 2<4 | 5 (6.9) | 2.2; 15.4 |

| 4<15 | 22 (30.6) | 20.2; 42.5 |

| 15<40 | 22 (30.6) | 20.2; 42.5 |

| 40+ | 6 (8.3) | 3.1; 17.3 |

| HIV2 (number, %) | 13 (18.6) | 10.3; 30.0 |

| Deaths (number, %) | 4 (5.6) | 1.5; 13.61 |

| Chance of death > 10% by Kala-Cal® | 25 (34.7) | 23.9; 46.9 |

| Hemorrhages or infections | 31 (43.7) | 31.9; 56.0 |

| Reported bleeding | 4 (5.6%) | 1.5; 13.6 |

| Detected bleeding | 15 (20.8) | 12.2; 32.0 |

| Sepsis | 10 (14.1) | 7.0; 24.4 |

| Any bacterial infection | 23 (31.9) | 21.4; 44.0 |

| Variables | Median | Interquartile intervals | Mean | Reference values (median) | Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (p-value) |

| Plasma kDNA (AEq1 /mL) | 856.7 | 145.5-3,527.9 | 3,515.4 | 06 | 0.000 |

| Bone marrow kDNA (AEq/106HCEq2) | 55.7 | 3.6 – 4,008 | 889.9 | 06 | 0.000 |

| IL-1b pg/mL | 0.9 | 0.2 – 2.1 | 2.0 | 0.18 (0–3.66)3 | 0.000 |

| IL-6 pg/mL | 9.5 | 2.4 – 28.0 | 41.7 | 0 (0–0)3 | 0.000 |

| IL-8 pg/mL | 26.2 | 9.8 – 145.5 | 146.9 | 0 (0–0)3 | 0.000 |

| IL-10 pg/mL | 18.4 | 8.7 – 35 | 30.2 | 0 (0–0)3 | 0.000 |

| IL-12 pg/mL | 1.2 | 0.0 – 2.5 | 1.8 | 0 (0–0)3 | 0.000 |

| TNF-a pg/mL | 1.0 | 0.3 – 3.0 | 2.2 | 0 (0–0)3 | 0.000 |

| TGF-b ng/mL | 23.6 | 11.2 – 42.4 | 39.6 | NA4,5 | - |

| Markers of severe disease (number of patients) |

Blood AEq1 median, (mean) |

p-value2 |

Bone marrow AEq/109HCEq median, (mean) |

p-value3 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| <15 (27) | 508 (2,513) | 27 (519) | ||

| 15+ (44) | 2,679 (5,091) | 0.022 | 137 (1,494) | 0.043 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female (30) | 329 (1,580) | 28 (631) | ||

| Male (41) | 1,452 (4,898) | 0.012 | 90 (1,079) | 0.073 |

| HIV | ||||

| Yes (13) | 4,207 (7,016) | 56 (2,867) | ||

| No (57) | 511 (2,768) | 0.006 | 35 (500) | 0.168 |

| Hospital outcome | ||||

| Death (4) | 11,826 (11,925) | 487 (605) | ||

| Survival (67) | 830 (3,020) | 0.169 | 56 (907) | 0.273 |

| Chance of death > 10% by Kala-Cal® | ||||

| > 10% (25) | 3,532 (6,617) | 290 (2,280) | ||

| <10% (46) | 311 (1,866) | <0.001 | 20 (350) | 0.001 |

| Reported bleeding | ||||

| Yes (4) | 8,855 (10,440) | 89 (406) | ||

| No (67) | 830 (3,108) | 0.350 | 56 (919) | 0.517 |

| Detected bleeding | ||||

| Yes (15) | 823 (4,427) | 214 (1,406) | ||

| No (56) | 876 (3,276) | 0.873 | 21 (752) | 0.012 |

| Sepsis | ||||

| Yes (10) | 888 (5,619) | 247 (375) | ||

| No (60) | 1,130 (3,210) | 0.856 | 34 (988) | 0.374 |

| Any bacterial infection | ||||

| Yes (23) | 837 (3,679) | 425 (466) | ||

| No (48) | 1,059 (3,439) | 0.758 | 65 (1,093) | 0.722 |

| Variables (number of patients) |

IL-1b median, (mean) |

p-value1 |

IL-6 median, (mean) |

p-value |

IL-8 median, (mean) |

p-value |

IL-10 median, (mean) |

p-value |

IL-12 median, (mean |

p-value |

TNF-a median, (mean) |

p-value |

TGF-b median, (mean) |

p-value |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||||

| <15 (27) | 1.1 (2.1) | 14.0 (49.3) | 28.8 (130.7) | 23.4 (36.4) | 1.4 (2.1) | 1.2 (2.5) | 23.1 (40.5) | |||||||

| 15+ (44) | 0.4 (1.9) | 0.18 | 7.8 (28.9) | 0.16 | 23.3 (174.2) | 0.95 | 12.8 (19.8) | 0.02 | 0.6 (1.3) | 0.18 | 0.9 (1.6) | 0.52 | 24.5 (38.0) | 0.95 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||||

| Female (30) | 0.9 (1.9) | 8.4 (55.9) | 25.6 (118.7) | 23.1 (32.6) | 1.0 (2.2) | 2.1 (3.1) | 13.9 (40.6) | |||||||

| Male (41) | 1.0 (2.0) | 0.95 | 13.6 (32.6) | 0.79 | 26.2 (164.8) | 0.99 | 13.6 (28.7) | 0.06 | 1.3 (1.6) | 0.92 | 0.9 (1.7) | 0.54 | 28.5 (38.9) | 0.25 |

| HIV-infection | ||||||||||||||

| Yes (12) | 1.3 (2.7) | 8.1 (13.0) | 46.7 (188.1) | 12.4 (14.3) | 1.2 (1.7) | 1.6 (1.9) | 16.5 (35.9) | |||||||

| No (57) | 0.9 (1.9) | 0.46 | 13.0 (48.8) | 0.50 | 25.4 (140.5) | 0.50 | 21.8 (34.2) | 0.04 | 1.3 (1.9) | 0.87 | 1.0 (2.3) | 0.70 | 24.05 (40.1) | 0.65 |

| Hospital outcome | ||||||||||||||

| Death (4) | 1.3 (1.3) | 24.7 (44.4) | 48.1 (173.9) | 12.0 (31.5) | 1.4 (1.8) | 1.2 (1.8) | 18.6 (20.4) | |||||||

| Survival (62) | 0.9 (2.1) | 0.45 | 9.1 (42.2) | 0.44 | 26.4 (147.5) | 0.96 | 18.7 (30.5) | 0.44 | 1.2 (1.8) | 0.61 | 1.0 (2.3) | 0.84 | 24.1 (20.4) | 0.58 |

| Chance of death2 | ||||||||||||||

| > 10% (23) | 1.0 (2.5) | 15.4 (44.3) | 65.2 (206.5) | 16.2 (27.8) | 1.1 (1.6) | 1.0 (2.3) | 24.5 (45.4) | |||||||

| <10% (43) | 0.9 (1.8) | 0.33 | 9.5 (44.3) | 0.45 | 24.6 (118.5) | 0.10 | 19.1 (32.0) | 0.59 | 1.3 (1.9) | 0.68 | 0.9 (2.2) | 0.36 | 22.3 (36.1) | 0.53 |

| Reported bleeding | ||||||||||||||

| Yes (3) | 1.6 (1.8) | 34.1 (63.7) | 78.6 (246.1) | 34.7 (51.3) | 2.0 (2.1) | 0.4 (1.8) | 15.7 (19.8) | |||||||

| No (63) | 0.9 (2.0) | 0.14 | 8.6 (41.2) | 0.03 | 24.9 (144.5) | 0.16 | 16.6 (29.5) | 0.15 | 1.2 (1.8) | 0.44 | 1.0 (2.3) | 0.83 | 23.6 (40.3) | 0.51 |

| Detected bleeding | ||||||||||||||

| Yes (13) | 0.9 (2.8) | 17.2 (24.9) | 88.5 (242.7) | 16.1 (24.1) | 2.0 (2.5) | 2.1 (2.2) | 42.1 (59.8) | |||||||

| No (53) | 1.0 (1.9) | 0.50 | 8.6 (46.6) | 0.42 | 24.6 (126.2) | 0.04 | 21.8 (32.1) | 0.57 | 1.2 (1.7) | 0.13 | 1.0 (2.3) | 0.66 | 20.9 (34.3) | 0.09 |

| Sepsis | ||||||||||||||

| Yes (10) | 1.6 (1.9) | 23.0 (137.3) | 110.2 (229.9) | 36.9 (37.3) | 1.9 (2.5) | 2.4 (2.5) | 18.3 (31.9) | |||||||

| No (56) | 0.8 (2.0) | 0.06 | 8.1 (25.3) | 0.06 | 24.7 (134.7) | 0.21 | 16.1 (29.3) | 0.07 | 0.9 (1.7) | 0.04 | 0.9 (2.2) | 0.17 | 25.7 (40.7) | 0.41 |

| Any bacterial infection | ||||||||||||||

| Yes (22) | 1.6 (2.4) | 25.2 (83.1) | 67.0 (203.9) | 30.5 (40.6) | 1.9 (2.1) | 2.4 (2.8) | 18.9 (33.0) | |||||||

| No (44) | 0.7 (1.8) | 0.01 | 7.2 (21.9) | 0.01 | 22.6 (121.8) | 0.03 | 16.0 (25.5) | 0.04 | 0.9 (1.7) | 0.11 | 0.8 (2.0) | 0.01 | 29.5 (42.5) | 0.24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).