1. Introduction

Since in vitro fertilization (IVF) had become one of the most popular treatment of human infertility caused by various issues of gamete quality, many technical advances of IVF techniques were achieved. Despite that, the clinical efficacy of IVF has not kept pace with these achievements and still remains disturbingly low [

1]. There is a strong consensus among experts that this drawback is mainly associated with embryo quality and derives from impaired function of gametes. Historically, IVF was developed for female infertility of tubal origin to by-pass the obstacle impeding spermatozoa and oocytes from meeting [

2]. However, it was rapidly understood that IVF can also be used with success in male infertility with diminished sperm count and motility so as to facilitate sperm access to the oocyte by avoiding physiological barriers present in the upper female genital tract [

3].

The development of laboratory techniques assisting fertilization by means of micromanipulation, mainly intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) [

4] and later round spermatid injection (ROSI) [

5] shifted the balance between the female and male indications of IVF even more in favor of the latter [

6]. Oocytes were traditionally blamed for IVF success rates still remaning far below the desired ones. This was reasonably true for steadily growing IVF indication in women of advanced ages. Embryo demise in other cases was usually explained by “hidden” oocyte issues. It is only recently that sperm involvement in embryo dysfunction has been increasingly acknowledged and the micromanipulation techniques used to assist fertilization have been shown to contribute by further limiting natural mechanisms of sperm selection as compared with conventional IVF [

7].

This review deals with the principal sperm-derived factors causing human embryo dysfuncion, implantation failure, miscarriage and offspring abnormalities and explains their molecular mechanisms of action. Current possibilities of detecting each factor’s presence and measures that can be taken to overcome its effect on IVF clinical outcome are highlighted.

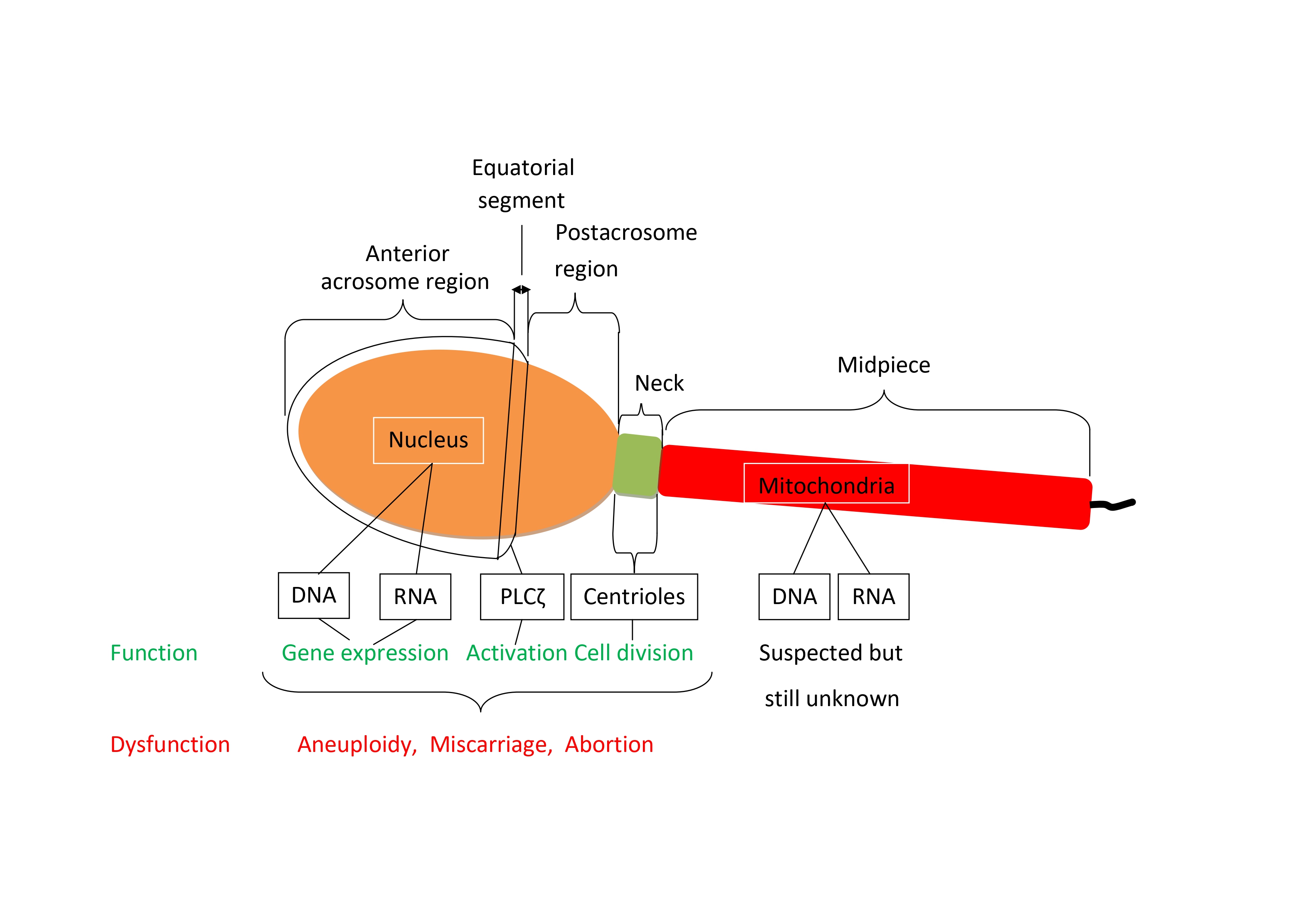

2. Sperm Oocyte-Activating Factor

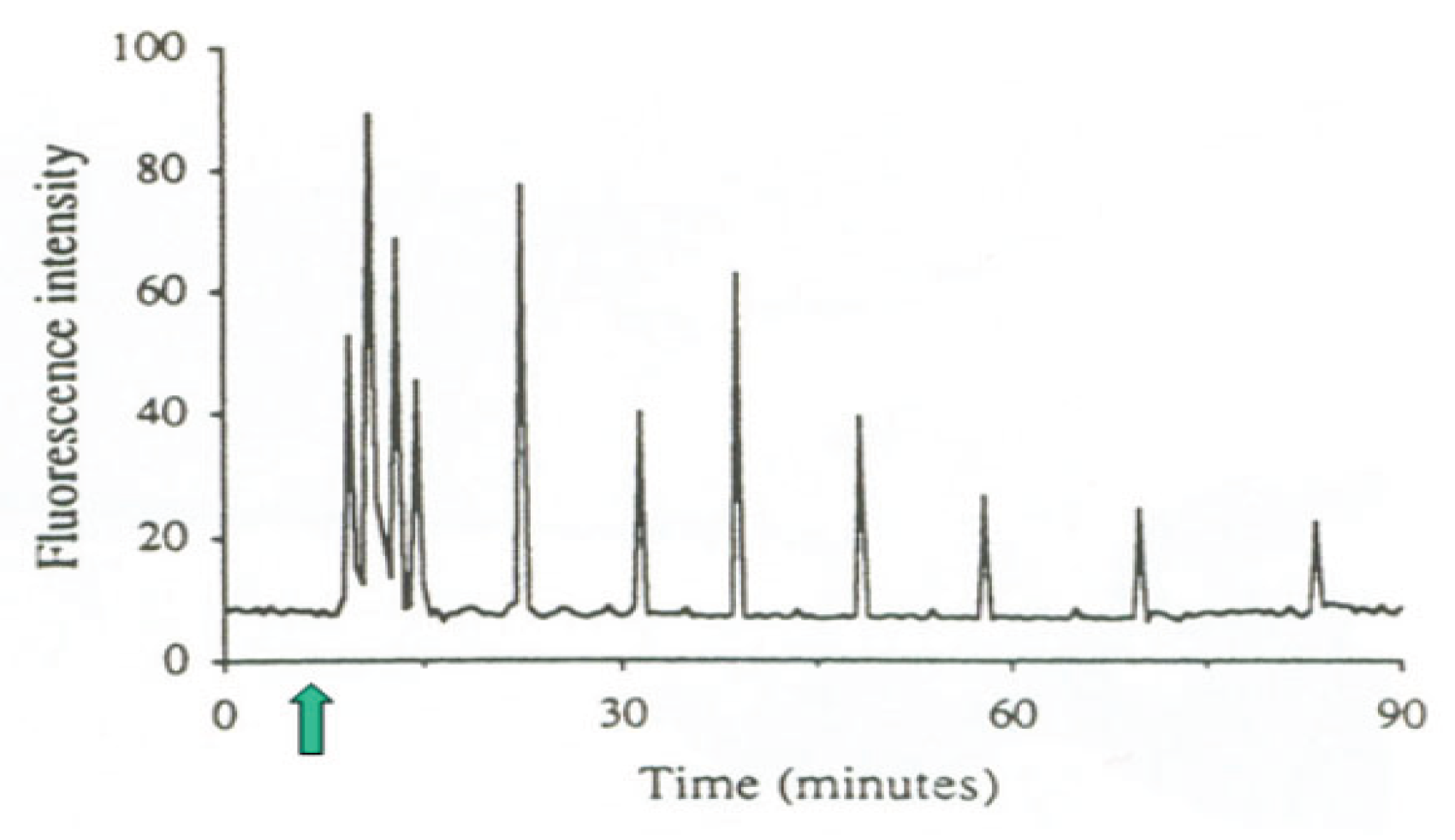

At the outset of fertilization, the cell cycle of the oocyte is arrested at the metaphase of the second meiotic division. In order to complete meiosis and start the first embryonic cell cycle, the oocyte needs to be activated by the fertilizing spermatozoon. Oocyte activation consists of a series of sequential signal transduction events that are started by a series of periodic sharp increases and decreases of cytosolic free Ca

2+ concentration, termed calcium oscillations, induced by the fertilizing spermatozoon (

Figure 1). The sperm oocyte-activating factor, initially called oscillin, has

been identified as a special form of phospholipase C (PLC) referred to as PLC zeta (PLCζ). It was first discovered in mouse [

8] and later in human spermatozoa where it was localized to the equatorial region [

9], more precisely along the inner acrosomal membrane and in the perinuclear theca [

10] where it was undetectable in sperm from patients with a history of failed ICSI [

9].

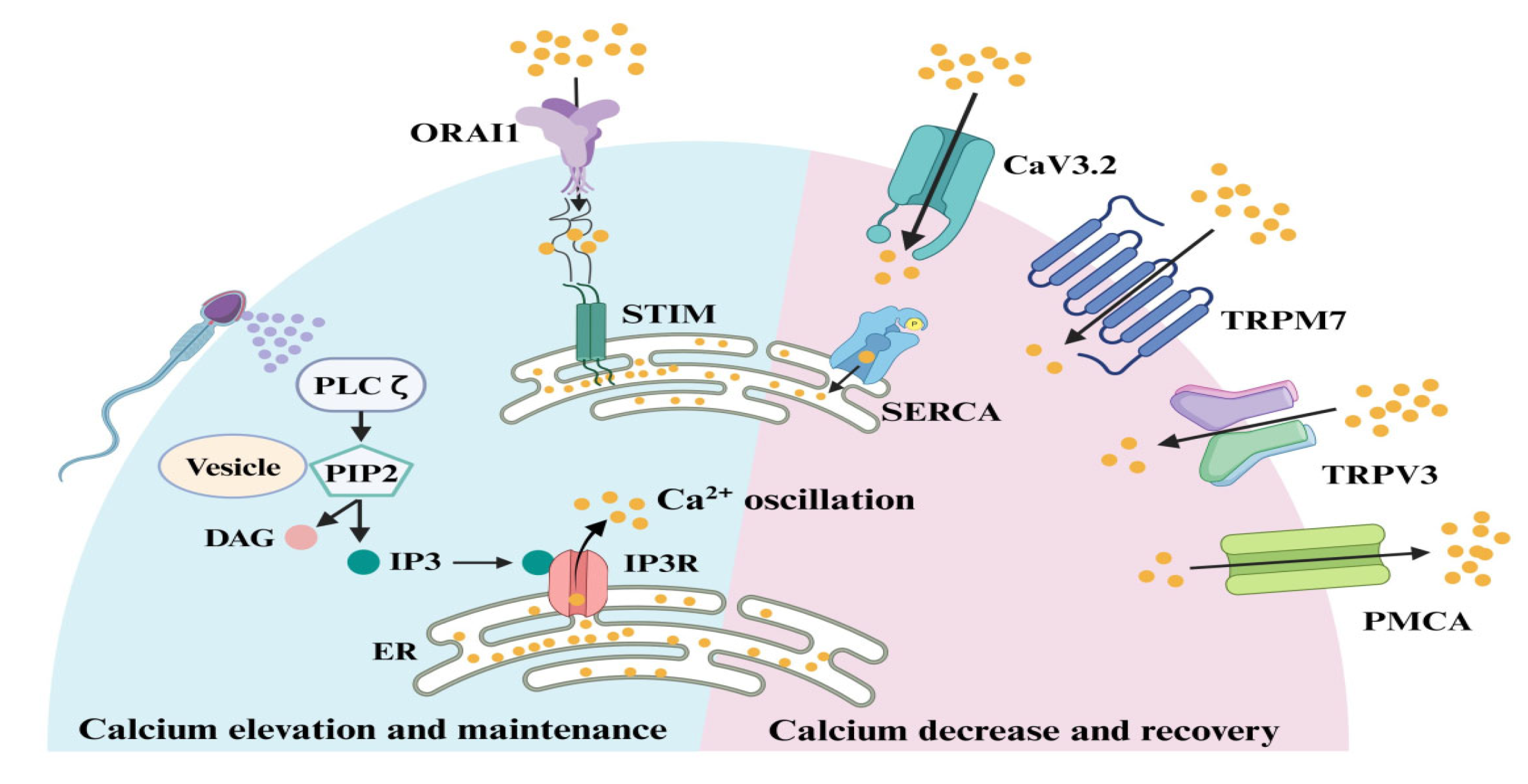

The mechanism of sperm-induced calcium oscillation in oocytes (

Figure 2) has been nicely reviewed recently [

11].

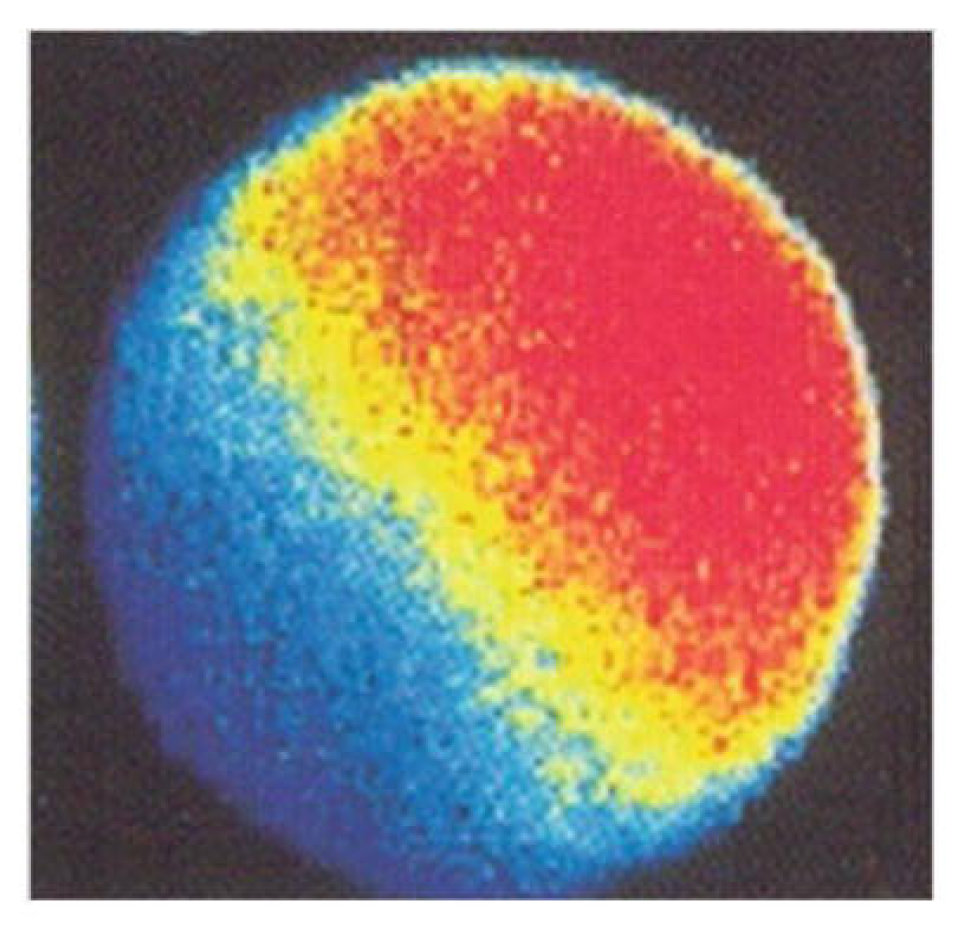

It has to be noted that the first of the ongoing series of calcium oscillation is generated by a different mechanism. The IP3-sensitive Ca

2+ stores are accumulated in the peripheral region of the oocyte from which the signal (Ca

2+ wave) runs across the whole oocyte (

Figure 3) owing to Ca

2+-induced Ca

2+ release from ryanodine-sensitive stores spread all over

the bulk of oocyte cytoplasm [

12]. Apart from causing complete fertilization failure, minor deficiencies of PLCζ can sometimes be compatible with fertilization but cause persistent embryo quality issues and/or miscarriage after embryo transfert [

13]. Specifically, abnormalities of sperm-induced calcium signals can cause complete failure of the second meiotic division, leading to triploidy; incomplete failure of the second meiotic division, leading to de novo chromosomal numerical abnormalities; abnormal pronuclear development and function; abnormalities of the blastomere cell cycle, possibly leading to embryo cleavage arrest; and problems with blastomere allocation to embryonic cell lineages, leading to disproportionate development of the inner cell mass and trophectoderm derivatives, which can be the origin of implantation failure or miscarriage [

14]. More recently, a homozygous missense mutation of actin-like 7A (

ACTL7A) gene was identified by whole-exome sequencing in two infertile brothers, and a corresponding mutated mouse model was generated [

15]. Both the infertile brothers and the model mice exhibited reduced expression of PLCζ in spermatozoa and a complete fertilization failure after ICSI, which could be overcome by assisted oocyte activation (see section 6.2. of this article for methodological details). It has to be underscored that the mutation was undetectable by conventional semen analysis and that the individuals were homozygous for it [

15]. In cases of heterozygous mutations, a slighter reduction of PLCζ can be expected, leading to early embryo dysfunction rather that complete fertilization failure. In fact, changes in the expression or intracellular position of PLCζ in spermatozoa are associated with subfertility or even infertility owing to impaired embryonic development [

16], and ACTL7A protein levels were shown to be significantly reduced in sperm samples presenting poor embryo quality [

17].

Later studies revealed other genetic causes of sperm-related human infertility, including homozygous pathogenic variants in actin-like 9 (

ACTL9) gene [

18], disruption of IQ motif-containing N (

IQCN) gene [

19], and bi-allelic mutations in

PLCZ1 (the gene coding for PLCζ in humans) [

20,

21].

3. Sperm Centrioles

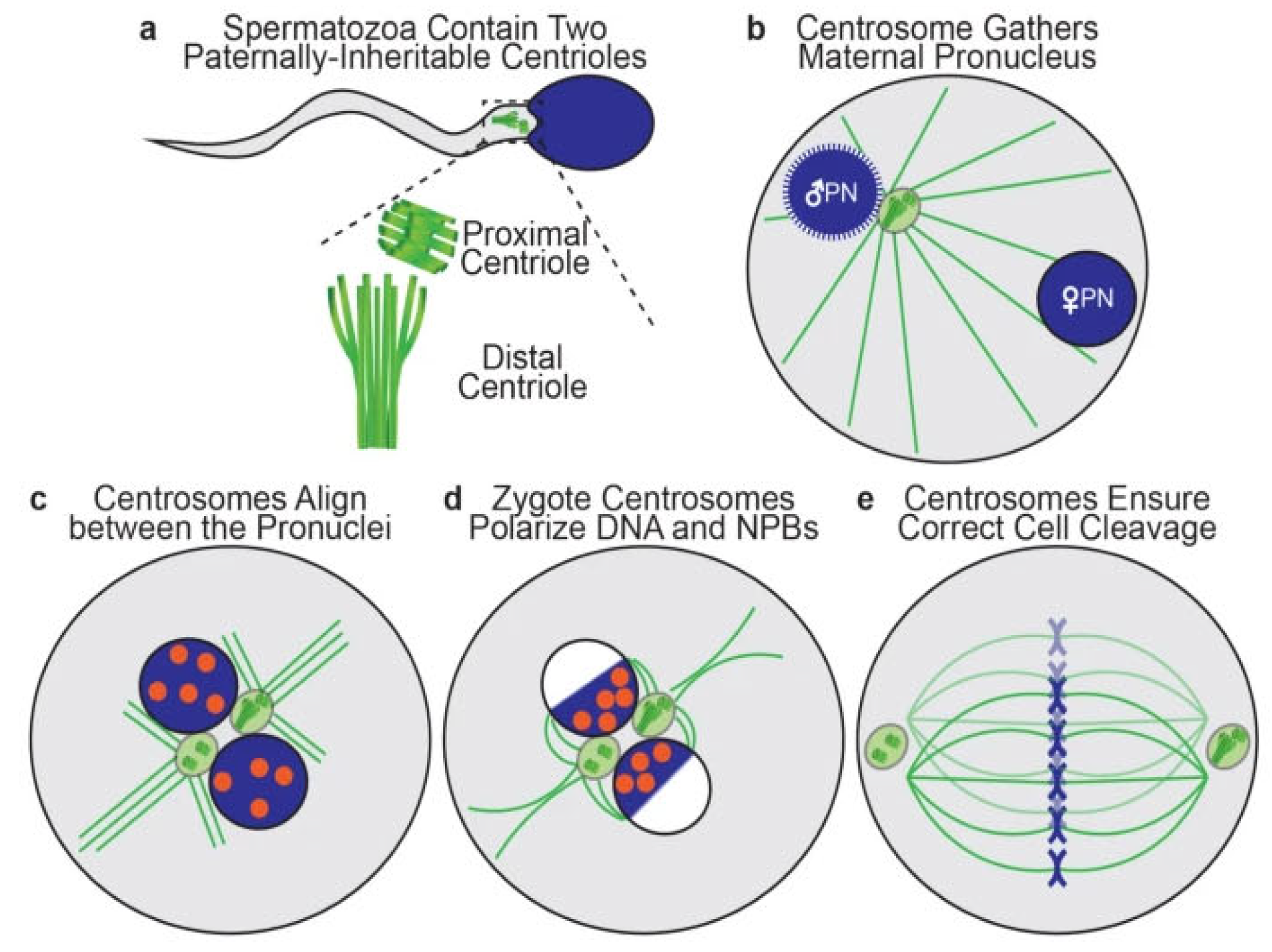

Each human spermatozoon has two centrioles while the oocyte has none [

22]. The sperm centrioles (

Figure 4), a barrel-shaped (typical) proximal one and a fan-shaped (atypical) distal one, are both located in the sperm neck (a small region between sperm head and midpiece) and exert multiple functions during fertilization and subsequent embryo development [

23]. The human zygotes inherits both sperm centrioles [

24]. The actions of sperm centrioles in the human zygote (

Figure 4) were reviewed recently [

25]. Short after sperm-oocyte fusion (or sperm injection into the oocyte), the paternal centrioles are close to each other and to the sperm nucleus (becoming the male pronucleus) (

Figure 4a), form the zygote’s first centrosome by recruiting pericentriolar protein from oocyte, and send out a microtubule aster to pull the maternal pronucleus towards the female one leading to pronuclear apposition (

Figure 4b). After replication, the two zygote centrosomes, each containing two sperm-derived centrioles, align in the interpronuclear area (

Figure 4c), ineract with pronuclei’s nuclear pores and atract DNA, visualized in living oocytes by microscopic observation of nucleolar precursor bodies (NPBs), toward the area of interpronuclear contact in preparation of the first cleavage division (

Figure 4d). Subsequently, the two centrosomes associate with the dual spindles poles, helping to organize and ensure correct mitotic division during the first embryonic cleavage (

Figure 4e) [

25]. Both epidemiological and observational studies (reviewed by Avidor-Reiss et al., 2019) [

22] strogly suggest that centriole abnormalities, may be at a cause of human embryo dysfuncion and failure to carry pregnancy to term.

4. Sperm DNA

There are multiple ways how factors affecting sperm DNA can influence early embryonic development, even before the major activation of embryonic gene transription [

26] and expression [

27,

28] taking place in humans at the 4-cell stage and between the 4-cell and the 8-cell stage of cleavage, respectively. Among these factors, genetic ones and epigenetic ones can be distinguished.

4.1. Genetic Factors

Sperm genetic factors affecting embryo developmental potential can be inherited or acquired. There is a number of chromosomal abnormalities and gene deletions or mutations that impact embryo quality. While most of them are incompatible with full sperm development or fertilizing ability, and thus excluded from transmission to embryos via natural fertilization, these barriers can now be partly circumvented with the use of micromanipulation-assisted IVF technologies, such as ICSI [

4] and ROSI [

5]. In fact, the de novo chromosomal abnormality rate in pre- and postnatal karyotypes of ICSI offspring was shown to be higher than in the general population and related to fathers’ sperm parameters [

29]. As to ROSI, the number of analyzable cases is still too low to be assessed.

DNA fragmentation is the most extensively studied genetic factor related to human embryo dysfunction. Originating mainly from apoptosis (programmed cell death) during spermatogenesis, oxidative stress, and defective chromatin

packaging during spermiogenesis, DNA breaks can affect a single DNA strand (oxidative stress, improper chromatin packaging) or both of them (apoptosis) [

30]. Since sperm DNA is protected against insults by its association with protamins in the highly compact chromatin, there is a close association of its fragmentation with defective chromatin packaging as revealed by scanning electron microscopy (

Figure 5) [

31]. Even though, unlike oocytes, spermatozoa are incapable of repairing their own DNA damage, it can be repaired after fertilization in zygotes using maternal DNA repair mechanisms both in mice [

32] and humans [

33]. General features of DNA-damage repair mechanisms and their activity in human zygotes and embryos have been reviewed recently [

34]. This DNA repair capacity is limited and likely to decline with female age, and unrepaired DNA damage can disrupt further development of the zygote, potentially leading to pregnancy loss, birth defects, and increased risk of certain diseases including cancer [

35]. On the other hand, errors of zygotic repair of sperm-derived DNA can be as destructive as the DNA damage itself, causing mis-rejoining of DNA fragments, chromosomal rearrangements, and the formation of acentric fragments [

35].

Another genetic factor which may affect human embryo viability and function is sperm aneuploidy, which results from errors of chromosome synapsis during spermatogenesis, mainly concerns chromosomes X and Y, and is more frequent in spermatozoa surgically retrieved from men with nonobstructive azoospermia [

36] or severe oligozoospermia [

37]. Aneuploid spermatozoa are capable of fertilizing the oocyte, leading to embryo aneuploidy [

38], and this situation is related to lower implantation and pregnancy rates and higher abortion rate after embryo transfer [

39].

4.2. Epigenetic Factors

Epigenetic factors that affect viability and function of human embryos by acting on paternal DNA, especially in the context of micromanipulation-assisted fertilization, have been extensively reviewed [

13,

40]. In this section, only those acting directly on sperm DNA structure are dealt with. Other epigenetic issues related to the action of sperm oocyte-activating factor and centriole were covered in other parts of this article (sections 2 and 3, respectively) and those related to the expression of small non-coding RNA are included in the section 5. Traditionally it was believed that all epigenetic marks, including DNA methylation, histone acetylation status and small RNAs, are completely erased and subsequently reset during germline reprogramming [

41]. In mammals, these events take place both in the germline and in zygote immediately after fertilization [

42]. However, it is now known that this reset is not complete, and some sperm-inherited regions can escape reprogramming to impact functional changes in the pre- and postimplantation embryo development via mechanisms that implicate transcription factors, chromatin organization, and transposable elements [

43].

A recent study reported a positive correlation good embryo quality in human IVF with Histone H3 Lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3) mark, whereas H3K4me3 and H3K4me2 marks were correlated with fertilization rate negatively [

44]. During mammalian preimplantation development, H3K27me3 is catalyzed by proteins of the polycomb group, an evolutionally conserved set of long-term transcriptional repressors, and is actively involved involved in silencing of gene expression before zygotic gene activation (ZGA) [

45]. In human germinal-vesicle oocytes, H3K27me3 was shown to be selectively deposited in promoters of developmental genes and partially methylated domains, it was a strikingly absent in human embryos at ZGA (8-cell) [

46], indicating a comprehensive erasure of this histone modification on both parental genomes [

47]. The concept of epigenetic modifications of sperm-derived DNA and associated proteins as factors influencing embryo viability and function is thus emerging an represents a challenge for future focused research.

5. Sperm RNA

The importance of RNA delivered to the oocyte at fertilization (large and small, coding and non-coding RNAs) for embryo development has long been subestimated [

48,

49], and it is only recently that this subject has received adequate attention, although there still remain many unanswered question as to the underlying mechanisms [

43,

50,

51]. In the mouse model it was shown that, in addition to RNAs synthesized during spermatogenesis, some RNA species are acquired by spermatozoa as they migrate through the male reproductive tract, specifically throughout epididymal transit [

52,

53], and a similar traffic was also reported in idiopathic infertile men undergoing fertility teatment [

50]. It was also suggested that particular RNAs may be selectively delivered to spermatozoa through epididymosomes in response to environmental factors [

54].

In humans, several hundreds of RNA elements (exon-sized sequences in RNA molecules that can affect gene expression), including microRNAs, transfer RNA-derived small RNA and small noncoding RNAs, were shown to be significantly associated with blastocyst development, and some of them were closely linked to genes involved in critical developmental processes, such as mitotic spindle formation and specification of ectoderm and mesoderm cell lineages [

54]. Similar to the mouse, environmental exposures affect human sperm RNA [

55], mainly acting on sperm microRNAs [

43], and the presence or absence of specific RNA elements are positively or negatively correlated with idiopathic male infertility [

56,

57]. On the whole, sperm RNAs are increasingly considered potential markers of sperm-derived embryo dysfunction and therapeutic targets, although mechanims of their actions in embryos still remain to be understood only partly.

6. Clinical Resolution

When the clinician is faced with repeated embryo dysfunction (cleavage arrest, slow cleavage, blastomere multinucleation, embryo fragmentation, etc) in human IVF, the first question to be asked is whether the sperm contribution is a plausible explanation or the problem is more likely to be derived from oocyte issues. When there is no apparent reason to suspect the female factor (age, ovarian reserve, endocrine imbalance, overweight, systemic or local disease), sperm origin is probable, but sperm factors can also contribute to dysfunctions apparently due to the oocyte. The detection of sperm-derived etiologies is not an easy task because appropriate diagnostic tests for many of them are not easily available (see section 6.1.). Once a sperm anomaly is detected, appropriate treatment, superimposed to the basic IVF procedure, has to be chosen.

6.1. Diagnosis

With the exception of sperm DNA fragmentation, for which numerous types of test are currently available [

58], the other sperm derived factors are more difficult to diagnose. Serious problems of the oocyte sperm-activating factor can be easily blamed for in cases of total fertilization failure after ICSI. However, lighter forms of deficiency, leading to impaired embryo development after apparently normal fertilization, can only be detected by evaluating sperm-induced oscillations of cytosolic free Ca

2+ oscillations by confocal microscopy after oocyte loading with intracellular calcium indicators [

14], which is incompatible with oocyte survival and further embryo development. In order to obviate this problem, tests substituting human oocytes with animal ones were developed. Thus far, mouse oocytes are the most commonly used model with which to study the fertilizing capacity of human sperm, becaue of their ease of access and handling, high cleavage rate after intracytoplasmic injection of human sperm and the relatively low rate of spontaneous activation [

59]. Piezo-driven ICSI of human sperm into mouse oocytes can be used both to assess the activation rate (mouse oocyte activation test, MOAT) [

60,

61] and the sperm-induced calcium oscillation pattern (mouse oocyte calcium analysis, MOCA) [

62]. Performance of patients’ spermatozoa is compared to that of spermtozoa from fertile donors in both of these tests. The MOCA test is particularly useful in patients whose oocytes do undergo fertilization after ICSI but subsequently develop into dysfunctional embryos to evaluate the relative contribution of spermatozoa and oocytes to this condition. In addition to mouse, heterologous ICSI with hamster oocytes was also used to assess sperm oocyte-activating performance [

63].

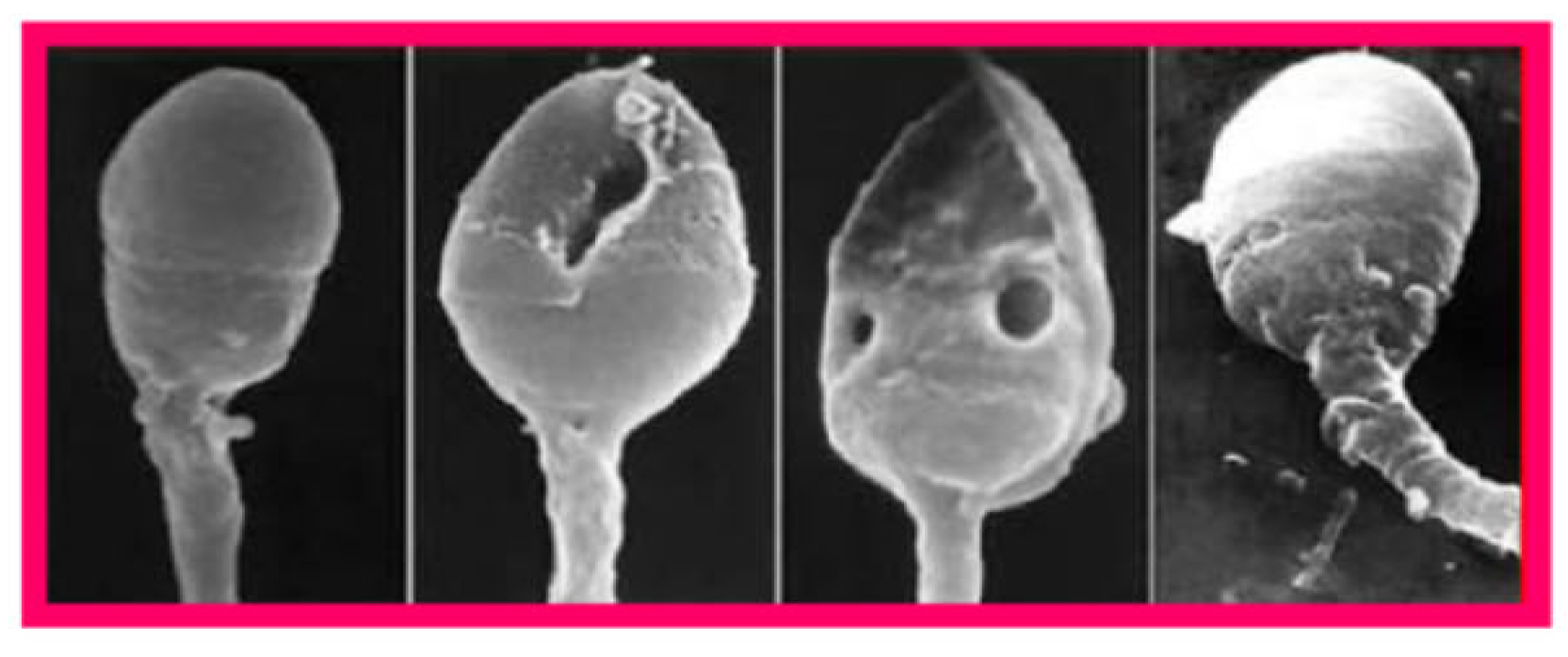

In some cases, defective function of sperm oocyte-activating factor can be detected by a direct observation of sperm cells. This is easy in patients with globozoospermia, the most notorious anomaly associated with the inability of spermatozoa to activate oocytes. Spermatozoa from these patients lack acrosome and show deficiency of the oocyte-activating factor PLCζ making them unable to correctly activate oocytes even when injected to their cytoplasm by ICSI [

64]. However, in most men the insufficiency of sperm oocyte-activating factor is associated with subtler phenotypical manifestations that cannot be distinguished by conventional semen analysis. This is the case of disruption in actin-like 7A (

ACTL7A) that are associated with acrosomal defects detectable by cytochemistry and electron microscopy [

15]. Reduced sperm ACTL7A protein levels were shown to be significantly associated with poor embryo quality and suggested as a biomarker for assisted reproductive technology outomes [

17]. Genetic testing for

PLCZ1 (the gene coding for PLCζ in humans) mutations [

20,

21] can also be envisaged when issues of sperm-induced oocyte activation are suspected.

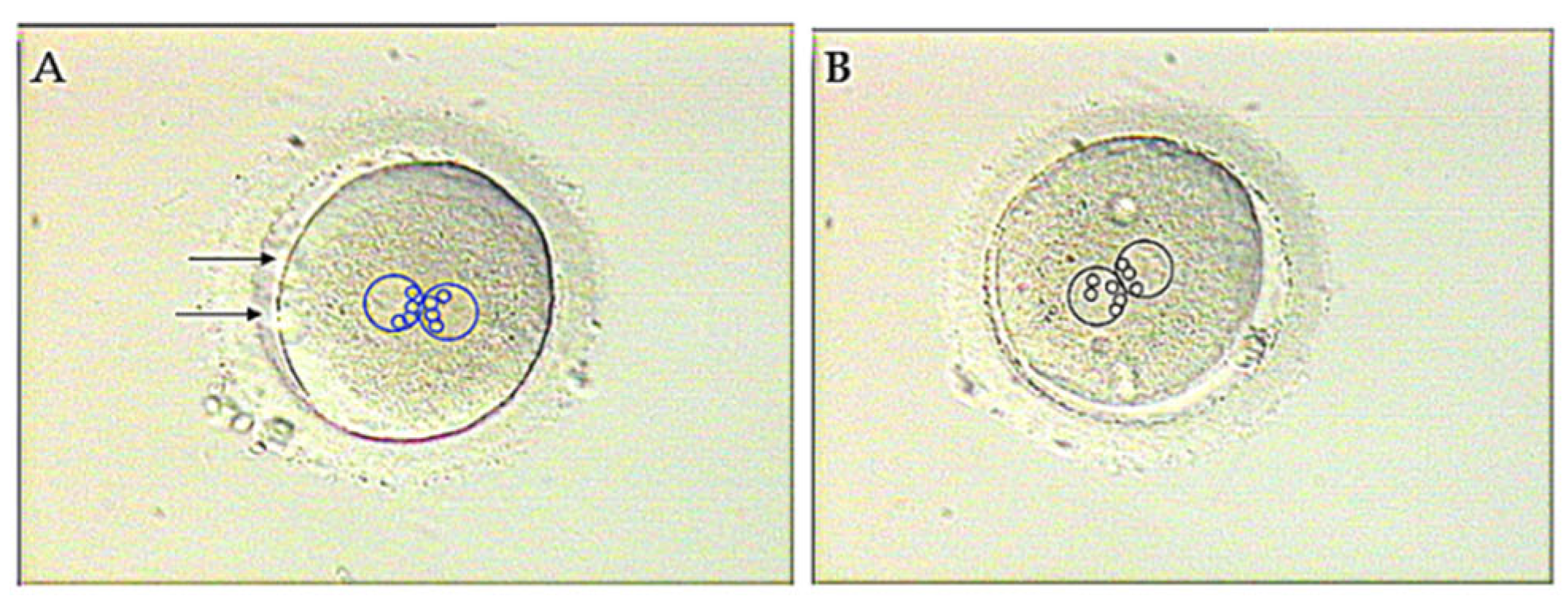

Defective function of sperm centrioles can be suspected when NPBs, marking de position of DNA in both pronuclei (see section 3 of this article), fail to get adequately polarized in the zygote (

Figure 6) [

65]. However, abnormal pronuclear patterns are not exclusive for centriolar issues and can also be causes by oocyte-derived factors. For a more specific diagnosis of centriole dysfunction, heterologous ICSI can be used [

59]. Given that mouse oocytes cannot be used for this objective as the embryonic centrosome is maternallyl derived in rodents [

66,

67], recourse has been made to rabbit [

68] and bovine [

69,

70] oocytes since the centrosome is paternally inherited in these species, just as in human.

Assays for sperm RNAs relevant to embryonic development are emerging only recently and are based on next-generation sequencing to profile RNA extracted from the patients’ spermatozoa [

50,

57].

6.2. Treatment Options

There are a variety of treatment options available for alleviating sperm-derived embryo dysfunction in the context of human IVF. The choice of the specific therapy to be used in each case depends on the nature of sperm deficiency supposedly at cause of this situation.

Absent or reduced ability of spermatozoa to activate the oocyte leading, respectively, to fertilization failure and impaired embryo development can be treated with success by assisted oocyte activation (AOA) after ICSI. Even when performed as late as 24 hour after ICSI, most of oocytes that initially failed to fertilize did so after subsequent AOA by exposure to calcium ionophore and undeerwen at least one apparently normal cleavage division [

71]. The beneficial effect of AOA was substantiated by the demonstration that unfertilized sperm-injected oocytes subjected to AOA with the use of calcium ionophore A23187 (calcimycin) developed free cytosolic Ca

2+ oscillations, quite similar to those observed after sperm-oocyte fusion [

72]. This oocyte response to ionophore only occurred when a spermatozoon or a round spermatid (haploid sperm precursor cell) was present in their cytoplasm, and treatment of oocytes previously sham-injected with non-germ cells (leukocytes) merely displayed a single transient Ca

2+ rise [

73]. Nowadays there are many reports on the use of AOA with calcimycin, and all of them agree that the method is efficient in improving fertilization and embryo development after ICSI in couples with previous problems, even in those in which the implication of sperm oocyte-activating factor has not been clearly ascertained [

61,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78,

79,

80].

In addition to calcium ionophores, successful chemical-free activation of human oocytes can also be achieved by a special ICSI technique (double vigorous cytoplasmic aspiration [

81] or exposure of oocytes to an electrical field [

82].

The safety of AOA with calcium ionophores was assessed in several studies which addressed the frequency of chromosome segregation errors in the second meiotic division of the sperm-injected oocyte [

83] and neonatal and neurodevelopmental outcomes of children born [

84,

85,

86,

87]. None of these studies evidenced any serious adverse effects in any of these aspects. Even so, it has to be admitted that, in spite of these encouraging results, the sample sizes of these studies are relatively low and more follow-up evaluations of children born after AOA are required. For the time being, in order to avoid any trace of doubt concerning the use of calcium ionophores, the recourse to drug-free AOA (see above) is possible.

As to the treatment of embryo dysfunction caused by defective function of sperm centrioles, very scarce data are available. Only one study addresses this subject in 2005, and it was found that sperm centrosomal function could be induced by the treatment of human spermatozoa with dithiothreitol before ICSI and of oocytes with paclitaxel after ICSI [

88]. However, these pioneering observations have not been confirmed by any subsequent study so far.

Treatment options to be envisaged in cases of sperm DNA fragmentation have been reviewed recently [

89]; they involve treatment of comorbidities, if suspected to be at the cause, in vivo therapies given to affected men and in vitro sperm selection techniques. Specifically, patient-tailored use of oral antibiotics and anti-inflammatory agents to control semen infection [

90], hormonal substitution (gonadotropins, selective estrogen receptor modulators, and aromatase inhibitors) [

91], oral administration of antioxidant vitamins [

92,

93], in vitro selection of living spermatozoa with morphologically intact chromatin [

94] and the recourse to testicular spermatozoa as the ultimate measure when all the above fail [

95] were demonstrated to be able to cope with sperm DNA integrity issues.

No specific treatments for sperm DNA issues other than fragmentation and those related to sperm RNA (mainly epigenetic ones) have been suggested yet. However, because most of these issues emerged in the era of ICSI, it can be speculated that oocyte vestments (cumulus oophorus and zona pellucida), that have to be negotiated by the spermatozoon before it can fertilize naturally, might exert a barrier effect which could selectively prevent spermatozoa carrying different genetic and epigenetic abnormalities from entering [

7]. If this hypothesis is confirmed, methods for the selection of spermatozoa for ICSI, based on their affinity to the zona pellucida will probably be introduced to future clinical IVF practice. Alternatively, when spermatozoa from a given patient are capable of penetrating into oocytes by their proper means, conventional IVF, potentially enhanced by sperm pretreatment with pentoxifylline [

96,

97], might be used instead of ICSI.

7. Conclusions

Sperm factors are generally accepted to play essential roles in human embryo development. They include sperm oocyte-activating factor, centrioles, DNA and RNA, each of them affecting different embryo developmental characterisctics. The nature of perturbations detected can thus call attention to the factor most likely to be involved. Abnormalities of sperm-induced oocyte activation can entail, in addition to total fertilization failure, triploidy, de novo chromosomal numerical abnormalities, atypical pronuclear development, and recurrent failures of embryo cleavage, implantation and postimplantation development. Defective function of sperm centrioles causes pronuclear abnormalites, impair embryo morphology (fragmentation) implantation failure and miscarriage. Sperm DNA and RNA issues can be at the origin of recurrent pregnancy loss and birth defects.

Sperm origin of any of the above abnormalities is more likely in couples in whom no problems relative to the female reproductive health can be detected. However, the presence of the female factors does nor exclude superimposition of male factors which should thus never be forgotten. Except sperm DNA fragmentation, diagnosis of the other potential sperm factors is more difficult. The dysfunction of sperm oocyte-activating factor (PLCζ) can be assessed indirectly, by heterologous ICSI with mouse oocytes, or directly by the evaluation of PLCζ abundance and distribution in spermatozoa or related ultrastructural anomalies. Heterologous ICSI (rabbit or bovine oocytes) can also serve to evaluate the function of sperm centrioles. Abnormalities of sperm DNA (other than fragmentation) and RNA can be assessed by next-generation sequencing.

Available treatments of sperm-derived embryo dysfunction include assisted oocyte activation (for oocyte-activating factor), and oral antioxidants, treatment of comorbidities and high-magnification selection of spermatozoa to be used in ICSI (for sperm DNA fragmentation). No specific treatments yet exist for other DNA and RNA anomalies, but the use of conventional IVF instead of ICSI might be considered where feasible.

Author Contribution: J.T. wrote the first draft, R.M.T. prepared the figures, and both J.T. and R.M.T. revised the final draft and finalized the submission. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

There was no external funding for this article

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bashiri, A.; Halper, K.I.; Orvieto, R. Recurrent implantation failure-update overview on etiology, diagnosis, treatment and future directions. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2018, 16, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steptoe, P.C.; Edwards, R.G. Birth after reimplantation of a human embryo. Lancet. 1978, 2, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, R.G.; Steptoe, P.C. Current status of in-vitro fertilisation and implantation of human embryos. Lancet. 1983, 2, 1265–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palermo, G.; Joris, H.; Devroey, P.; Van Steirteghem, A.C. Pregnancies after intracytoplasmic injection of single spermatozoon into an oocyte. Lancet. 1992, 340, 17–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesarik, J.; Mendoza, C.; Testart, J. Viable embryos from injection of round spermatids into oocytes. N Engl J Med. 1995, 333, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesarik, J. Assisted reproduction: new challenges and future prospects. In 40 Years After In Vitro Fertilisation; Tesarik, J., Ed.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2019; pp. 269–286. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, E.T.Y.; Lee, B.K.M.; Lee, C.L.; Tian, X.; Lam, K.K.W.; Li, R.H.W.; Ng, E.H.Y.; Yeung, W.S.B.; Ou, J.P.; Chiu, P.C.N. The role of spermatozoa-zona pellucida interaction in selecting fertilization-competent spermatozoa in humans. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023, 14, 1135973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, C.M.; Larman, M.G.; Parrington, J.; Cox, L.J.; Royse, J.; Blayney, L.M.; Swann, K.; Lai, F.A. PLC zeta: a sperm-specific trigger of Ca(2+) oscillations in eggs and embryo development. Development. 2002, 129, 3533–3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.Y.; Jellerette, T.; Salicioni, A.M.; Lee, H.C.; Yoo, M.S.; Coward, K.; Parrington, J.; Grow, D.; Cibelli, J.B.; Visconti, P.E.; Mager, J.; Fissore, R.A. Human sperm devoid of PLC, zeta 1 fail to induce Ca(2+) release and are unable to initiate the first step of embryo development. J Clin Invest. 2008, 118, 3671–3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escoffier, J.; Yassine, S.; Lee, H.C.; Martinez, G.; Delaroche, J.; Coutton, C.; Karaouzène, T.; Zouari, R.; Metzler-Guillemain, C.; Pernet-Gallay, K.; Hennebicq, S.; Ray, P.F.; Fissore, R.; Arnoult, C. Subcellular localization of phospholipase Cζ in human sperm and its absence in DPY19L2-deficient sperm are consistent with its role in oocyte activation. Mol Hum Reprod. 2015, 21, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Huang, Z.; Dong, S.; Ding, M.; Li, J.; Wang, M.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, X.; Sun, X. Calcium signaling in oocyte quality and functionality and its application. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2024, 15, 1411000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M.; Barros, A.; Tesarik, J. The role of ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ stores in the Ca2+ oscillation machine of human oocytes. Mol Hum Reprod. 1996, 2, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesarik, J. Paternal Effects on Embryonic, Fetal and Offspring Health: The Role of Epigenetics in the ICSI and ROSI Era. [CrossRef]

- Tesarik, J. Calcium signaling in human preimplantation development: a review. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1999, 16, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, A.; Qu, R.; Chen, G.; Zhang, L.; Chen, J.; Tao, C.; Fu, J.; Tang, J.; Ru, Y.; Chen, Y.; Peng, X.; Shi, H.; Zhang, F.; Sun, X. Disruption in ACTL7A causes acrosomal ultrastructural defects in human and mouse sperm as a novel male factor inducing early embryonic arrest. Sci Adv. 2020, 6, eaaz4796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heytens, E.; Parrington, J.; Coward, K.; Young, C.; Lambrecht, S.; Yoon, S.Y.; Fissore, R.A.; Hamer, R.; Deane, C.M.; Ruas, M.; Grasa, P.; Soleimani, R.; Cuvelier, C.A.; Gerris, J.; Dhont, M.; Deforce, D.; Leybaert, L.; De Sutter, P. Reduced amounts and abnormal forms of phospholipase C zeta (PLCzeta) in spermatozoa from infertile men. Hum Reprod. 2009, 24, 2417–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, G.W.; Sun, Y.S.; Li, Z.C.; Shen, X.R.; Zhang, Y.N.; He, W.; Zhou, D.; Shi, H.J.; Xin, A.J.; Sun, X.X. Sperm-specific protein ACTL7A as a biomarker for fertilization outcomes of assisted reproductive technology. Asian J Androl. 2022, 24, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Zhang, T.; Guo, J.; Zhou, Q.; Gu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hu, L.; Zong, Y.; Song, J.; Zhang, S.; Dai, C.; Gong, F.; Lu, G.; Zheng, W.; Lin, G. Homozygous pathogenic variants in ACTL9 cause fertilization failure and male infertility in humans and mice. Am J Hum Genet. 2021, 108, 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Li, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, S.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Guo, J.; Gu, Y.; Gong, F.; Tan, Y.; Lu, G.; Zheng, W.; Lin, G. IQCN disruption causes fertilization failure and male infertility due to manchette assembly defect. EMBO Mol Med. 2022, 14, e16501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Lin, Y.; Deng, K.; Shen, J.; Cui, Y.; Liu, J.; Yang, X.; Diao, F. Mutations in PLCZ1 induce male infertility associated with polyspermy and fertilization failure. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2023, 40, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, B.; Zhang, T.; Niu, Y.; Hu, S.; Ding, Y.; Yao, G.; Wei, Z.; Yao, N.; Yao, Y.; Lu, Y.; He, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Sun, Y. Novel mutations in PLCZ1 lead to early embryonic arrest as a male factor. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2023, 11, 1193248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avidor-Reiss, T.; Mazur, M.; Fishman, E.L.; Sindhwani, P. The role of sperm centrioles in human reproduction– the known and the unknown. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, E.L.; Jo, K. , Nguyen, Q.P.H.; Kong, D.; Royfman, R.; Cekic, A.R.; Khanal, S.; Miller, A.L.; Simerly, C.; Schatten, G.; Loncarek, J.; Mennella, V.; Avidor-Reiss, T. A novel atypical sperm centriole is functional during human fertilization. Nat Commun, 2: 9, 2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai, Y.; Iwata, K.; Iba, Y.; Mio, Y. Diagnosis of abnormal human fertilization status based on pronuclear origin and/or centrosome number. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2015, 32, 1589–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kluczynski, D.F.; Jaiswal, A.; Xu, M.; Nadiminty, N.; Saltzman, B.; Schon, S.; Avidor-Reiss, T. Spermatozoa centriole quality determined by FRAC may correlate with zygote nucleoli polarization-a pilot study. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesarik, J.; Kopecny, V.; Plachot, M.; Mandelbaum, J. Activation of nucleolar and extranucleolar RNA synthesis and changes in the ribosomal content of human embryos developing in vitro. J Reprod Fertil. 1986, 78, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braude, P.; Bolton, V.; Moore, S. Human gene expression first occurs between the four- and eight-cell stages of preimplantation development. Nature. [CrossRef]

- Tesarik, J.; Kopecny, V.; Plachot, M.; Mandelbaum, J. Early morphological signs of embryonic genome expression in human preimplantation development as revealed by quantitative electron microscopy. Dev Biol. 1988, 128, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belva, F.; Bonduelle, M.; Buysse, A. ,.; Van den Bogaert, A.; Hes, F.; Roelants, M.; Verheyen, G.; Tournaye, H.; Keymolen, K. Chromosomal abnormalities after ICSI in relation to semen parameters: results in 1114 fetuses and 1391 neonates from a single center. Hum Reprod. 2020 Sep 1;35, 2149-2162. [CrossRef]

- Muratori, M.; Marchiani, S.; Tamburrino, L. , Baldi, E. Sperm DNA fragmentation: Mechanisms of origin. Adv Exp Med Biol, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesarik, J. Acquired sperm DNA modifications: Causes, consequences, and potential solutions. EMJ. 2019, 4, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leem, J.; Bai, G.Y.; Oh, J.S. The capacity to repair sperm DNA damage in zygotes is enhanced by inhibiting WIP1 activity. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022, 10, 841327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesarik, J.; Mendoza-Tesarik, R. Molecular clues to understanding causes of human assisted reproduction treatment failures and possible treatment options. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musson, R.; Gąsior, Ł.; Bisogno, S.; Ptak, G.E. DNA damage in preimplantation embryos and gametes: specification, clinical relevance and repair strategies. Hum Reprod Update. 2022, 28, 376–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, H.; Catt, S.; Vining, B.; Vollenhoven, B.; Horta, F. DNA repair and response to sperm DNA damage in oocytes and embryos, and the potential consequences in ART: a systematic review. Mol Hum Reprod. 2022, 28, gaab071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.H. Mechanisms of nondisjunction in human spermatogenesis. Cytogenet Genome Res, 2: 111(3-4). [CrossRef]

- Levron, J.; Aviram-Goldring, A.; Madgar, I.; Raviv, G.; Barkai, G.; Dor, J. Sperm chromosome abnormalities in men with severe male factor infertility who are undergoing in vitro fertilization with intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Fertil Steril. 2001, 76, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrell, D.T.; Wilcox, A.L.; Udoff, L.C.; Thorp, C.; Campbell, B. Chromosome 15 aneuploidy in the sperm and conceptus of a sibling with variable familial expression of round-headed sperm syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2001, 76, 1258–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burrello, N.; Vicari, E.; Shin, P.; Agarwal, A.; De Palma, A.; Grazioso, C.; D’Agata, R.; Calogero, A.E. Lower sperm aneuploidy frequency is associated with high pregnancy rates in ICSI programmes. Hum Reprod. 2003, 18, 1371–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrell, D.T. Epigenetics of the male gamete. Fertil Steril. 2012, 97, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hackett, J.A.; Surani, M.A. Beyond DNA: programming and inheritance of parental methylomes. Cell. 2013, 153, 737–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hackett, J.A.; Sengupta, R.; Zylicz, J.J.; Murakami, K.; Lee, C.; Down, T.A.; Surani, M.A. Germline DNA demethylation dynamics and imprint erasure through 5-hydroxymethylcytosine. Science. 2013, 339, 448–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lismer, A.; Kimmins, S. Emerging evidence that the mammalian sperm epigenome serves as a template for embryo development. Nat Commun, 2142; ;14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambiasso, M.Y.; Romanato, M.; Gotfryd, L.; Valzacchi, G.R.; Calvo, L. , Calvo, J.C.; Fontana, V.A. Sperm histone modifications may predict success in human assisted reproduction: a pilot study. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2024, 41, 3147–3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogliotti, Y.S.; Ross, P.J. Mechanisms of histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation remodeling during early mammalian development. Epigenetics. 2012, 7, 976–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Zhan, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.; Hou, Z.; Zhang, C.; Yi, L.; Gao, L.; Zhao, H.; Chen, Z-J. ; Liu, J.; Wu, K. Human zygotic genome activation is initiated from paternal genome. Cell Discov. 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotomayor-Lugo, F.; Iglesias-Barrameda, N.; Castillo-Aleman, Y.M.; Casado-Hernandez, I.; Villegas-Valverde, C.A.; Bencomo-Hernandez, A.A.; Ventura-Carmenate, Y.; Rivero-Jimenez, R.A. The dynamics of histone modifications during mammalian zygotic genome activation. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.D.; Lalancette, C.; Linnemann, A.K.; Leduc, F.; Boissonneault, G.; Krawetz, S.A. The sperm nucleus: chromatin, RNA, and the nuclear matrix. Reproduction. 2011, 141, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, J.; Silva, J.V.; Howl, J.; Santos, M.A.S.; Fardilha, M. All you need to know about sperm RNAs. Hum Reprod Update. 2021, 28, 67–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, M.; Russell, S.; Swanson, G.M.; Krawetz, S.A.; Menezes, K.; Moskovtsev, S.I.; Librach, C. A comprehensive analysis of spermatozoal RNA elements in idiopathic infertile males undergoing fertility treatment. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 10316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leggio, L.; Paternò, G.; Cavallaro, F.; Falcone, M.; Vivarelli, S.; Manna, C.; Calogero, A.E.; Cannarella, R.; Iraci, N. Sperm epigenetics and sperm RNAs as drivers of male infertility: truth or myth? Mol Cell Biochem. 2025, 480, 659–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conine, C.C.; Sun, F.; Song, L.; Rivera-Pérez, J.A.; Rando, O.J. Small RNAs gained during epididymal transit of sperm are essential for embryonic development in mice. Dev Cell, 46. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, U.; Sun, F.; Conine, C.C.; Reichholf, B.; Kukreja, S.; Herzog, V.A.; Ameres, S.L.; Rando, O.J. Small RNAs are trafficked from the epididymis to developing mammalian sperm. Dev Cell, 46. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, U.; Conine, C.C.; Shea, J.M.; Boskovic, A.; Derr, A.G.; Bing, X.Y.; Belleannee, C.; Kucukural, A.; Serra, R.W.; Sun, F.; Song, L.; Carone, B.R.; Ricci, E.P.; Li, X.Z.; Fauquier, L.; Moore, M.J.; Sullivan, R.; Mello, C.C.; Garber, M.; Rando, O.J. Biogenesis and function of tRNA fragments during sperm maturation and fertilization in mammals. Science. 2016, 351, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estill, M.; Hauser, R.; Nassan, F.L.; Moss, A.; Krawetz, S.A. The effects of di-butyl phthalate exposure from medications on human sperm RNA among men. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 12397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jodar, M.; Sendler, E.; Moskovtsev, S.I.; Librach, C.L.; Goodrich, R.; Swanson, S.; Hauser, R.; Diamond, M.P.; Krawetz, S.A. Absence of sperm RNA elements correlates with idiopathic male infertility. Sci Transl Med. 2015, 7, 295re6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, M.; Russell, S.; Menezes, K.; Moskovtsev, S.I.; Librach, C. Assessing spermatozoal small ribonucleic acids and their relationship to blastocyst development in idiopathic infertile males. Sci Rep. 2022 Nov 21;12, 20010. [CrossRef]

- Evgeni, E.; Sabbaghian, M.; Saleh, R.; Gül, M.; Vogiatzi, P.; Durairajanayagam, D.; Jindal, S.; Parmegiani, L.; Boitrelle, F.; Colpi, G.; Agarwal, A. Sperm DNA fragmentation test: usefulness in assessing male fertility and assisted reproductive technology outcomes. Panminerva Med. 2023, 65, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona Barberán, A.; Boel, A.; Vanden Meerschaut, F.; Stoop, D.; Heindryckx, B. Diagnosis and treatment of male infertility-related fertilization failure. J Clin Med. 2020, 9, 3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybouchkin, A.; Dozortsev, D.; de Sutter, P.; Qian, C.; Dhont, M. Intracytoplasmic injection of human spermatozoa into mouse oocytes: a useful model to investigate the oocyte-activating capacity and the karyotype of human spermatozoa. Hum Reprod. 1995, 10, 1130–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heindryckx, B.; Van der Elst, J.; De Sutter, P.; Dhont, M. Treatment option for sperm- or oocyte-related fertilization failure: assisted oocyte activation following diagnostic heterologous ICSI. Hum Reprod. 2005 Aug;20, 2237-41. [CrossRef]

- Vanden Meerschaut, F.; Leybaert, L.; Nikiforaki, D.; Qian, C.; Heindryckx, B.; De Sutter, P. Diagnostic and prognostic value of calcium oscillatory pattern analysis for patients with ICSI fertilization failure. Hum Reprod. 2013, 28, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, A.; Bongso, A.; Ng, S.C. Intracytoplasmic injection of human sperm into the hamster oocyte (hamster ICSI assay) as a test for fertilizing capacity of the severe male-factor sperm. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1996, 13, 647–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.L.; Yoon, S.Y.; Morshedi, M.S.; Lacey, D.R.; Jellerette, T.; Fissore, R.A.; Oehninger, S. Complete globozoospermia associated with PLCζ deficiency treated with calcium ionophore and ICSI results in pregnancy. Reprod Biomed Online. 2010, 20, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesarik, J. Noninvasive biomarkers of human embryo developmental potential. Int J Mol Sci. 2025, 26, 4928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.Y.; Schatten, H. Centrosome inheritance after fertilization and nuclear transfer in mammals. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007, 591, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avidor-Reiss, T.; Khire, A.; Fishman, E.L.; Jo, K.H. Atypical centrioles during sexual reproduction. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2015, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terada, Y. , Nakamura, S.; Simerly, C.; Hewitson, L.; Murakami, T.; Yaegashi, N.; Okamura, K.; Schatten, G. Centrosomal function assessment in human sperm using heterologous ICSI with rabbit eggs: a new male factor infertility assay. Mol Reprod Dev, 67. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Terada, Y.; Horiuchi, T.; Emuta, C.; Murakami, T.; Yaegashi, N.; Okamura, K. Human sperm aster formation and pronuclear decondensation in bovine eggs following intracytoplasmic sperm injection using a Piezo-driven pipette: a novel assay for human sperm centrosomal function. Biol Reprod. 2001, 65, 1359–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Terada, Y.; Horiuchi, T.; Emuta, C.; Murakami, T.; Yaegashi, N.; Okamura, K. Analysis of the human sperm centrosomal function and the oocyte activation ability in a case of globozoospermia, by ICSI into bovine oocytes. Hum Reprod. 2002, 17, 2930–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesarik, J.; Sousa, M. More than 90% fertilization rates after intracytoplasmic sperm injection and artificial induction of oocyte activation with calcium ionophore. Fertil Steril. 1995, 63, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesarik, J.; Testart, J. Treatment of sperm-injected human oocytes with Ca2+ ionophore supports the development of Ca2+ oscillations. Biol Reprod. 1994, 51, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M.; Mendoza, C.; Barros, A.; Tesarik, J. Calcium responses of human oocytes after intracytoplasmic injection of leukocytes, spermatocytes and round spermatids. Mol Hum Reprod. 1996, 2, 853–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heindryckx, B.; De Gheselle, S.; Gerris, J.; Dhont, M.; De Sutter, P. Efficiency of assisted oocyte activation as a solution for failed intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Reprod Biomed Online. 2008, 17, 662–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montag, M.; Köster, M.; van der Ven, K.; Bohlen, U.; van der Ven, H. The benefit of artificial oocyte activation is dependent on the fertilization rate in a previous treatment cycle. Reprod Biomed Online. 2012, 24, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebner, T.; Montag, M. ; Oocyte Activation Study Group; Montag, M.; Van der Ven, K.; Van der Ven, H.; Ebner, T.; Shebl, O.; Oppelt, P.; Hirchenhain, J.; Krüssel, J.; Maxrath, B.; Gnoth, C.; Friol, K.; Tigges, J.; Wünsch, E.; Luckhaus, J.; Beerkotte, A.; Weiss, D.; Grunwald, K.; Struller, D.; Etien, C. Live birth after artificial oocyte activation using a ready-to-use ionophore: a prospective multicentre study. Reprod Biomed Online, 30. [CrossRef]

- Murugesu, S.; Saso, S.; Jones, B.P.; Bracewell-Milnes, T.; Athanasiou, T.; Mania, A.; Serhal, P.; Ben-Nagi, J. Does the use of calcium ionophore during artificial oocyte activation demonstrate an effect on pregnancy rate? A meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. [CrossRef]

- Bonte, D.; Ferrer-Buitrago, M.; Dhaenens, L.; Popovic, M.; Thys, V.; De Croo, I.; De Gheselle, S.; Steyaert, N.; Boel, A.; Vanden Meerschaut, F.; De Sutter, P.; Heindryckx, B. Assisted oocyte activation significantly increases fertilization and pregnancy outcome in patients with low and total failed fertilization after intracytoplasmic sperm injection: a 17-year retrospective study. Fertil Steril. 2019, 112, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zhao, H.; Lv, J.; Dong, Y.; Zhao, M.; Sui, X.; Cui, R.; Liu, B.; Wu, K. Calcium ionophore improves embryonic development and pregnancy outcomes in patients with previous developmental problems in ICSI cycles. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022, 22, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, J.L.; Liang, S.S.; Pan, J.P.; Chen, Z.Q. ; Teng,X.M. Artificial oocyte activation with Ca2+ ionophore improves reproductive outcomes in patients with fertilization failure and poor embryo development in previous ICSI cycles. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). [CrossRef]

- Tesarik, J.; Rienzi, L.; Ubaldi, F.; Mendoza, C.; Greco, E. Use of a modified intracytoplasmic sperm injection technique to overcome sperm-borne and oocyte-borne oocyte activation failures. Fertil Steril. 2002, 78, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, R.; Fahmy, I.; Tawab, N.A.; Kamal, A.; El-Demery, Y.; Aboulghar, M.; Serour, G. Electrical activation of oocytes after intracytoplasmic sperm injection: a controlled randomized study. Fertil Steril. 2009, 91, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capalbo, A.; Ottolini, C.S.; Griffin, D.K.; Ubaldi, F.M.; Handyside, A.H.; Rienzi, L. Artificial oocyte activation with calcium ionophore does not cause a widespread increase in chromosome segregation errors in the second meiotic division of the oocyte. Fertil Steril. [CrossRef]

- Vanden Meerschaut, F.; D’Haeseleer, E.; Gysels, H.; Thienpont, Y.; Dewitte, G.; Heindryckx, B.; Oostra, A.; Roeyers, H.; Van Lierde, K.; De Sutter, P. Neonatal and neurodevelopmental outcome of children aged 3-10 years born following assisted oocyte activation. Reprod Biomed Online. 2014, 28, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deemeh, M.R.; Tavalaee, M.; Nasr-Esfahani, M.H. Health of children born through artificial oocyte activation: a pilot study. Reprod Sci. 2015, 22, 322–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateizel, I.; Verheyen, G.; Van de Velde, H.; Tournaye, H.; Belva, F. Obstetric and neonatal outcome following ICSI with assisted oocyte activation by calcium ionophore treatment. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2018, 35, 1005–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhou, Y.; Yan, Z.; Li, M.; Xue, S.; Cai, R.; Fu, Y.; Hong, Q.; Long, H.; Yin, M.; Du, T.; Wang, Y.; Kuang, Y.; Yan, Z.; Lyu, Q. Pregnancy and neonatal outcomes of artificial oocyte activation in patients undergoing frozen-thawed embryo transfer: a 6-year population-based retrospective study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019, 300, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Terada, Y.; Rawe, V.Y.; Uehara, S.; Morito, Y.; Yoshimoto, T.; Tachibana, M.; Murakami, T.; Yaegashi, N.; Okamura, K. A trial to restore defective human sperm centrosomal function. Hum Reprod. 2005, 20, 1933–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesarik, J. Lifestyle and environmental factors affecting male fertility, individual predisposition, prevention, and intervention. Int J Mol Sci. 2025, 26, 2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adel Domínguez, M.A.; Cardona Maya, W.D.; Mora Topete, A. Sperm DNA fragmentation: focusing treatment on seminal transport fluid beyond sperm production. Arch Ital Urol Androl. 2025, 97, 13128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Minhas, S.; Dhillo, W.S.; Jayasena, C.N. Male infertility due to testicular disorders. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021, 106, e442–e459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greco, E.; Iacobelli, M.; Rienzi, L.; Ubaldi, F.; Ferrero, S.; Tesarik, J. Reduction of the incidence of sperm DNA fragmentation by oral antioxidant treatment. J Androl. 2005, 26, 349–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, E.; Romano, S.; Iacobelli, M.; Ferrero, S.; Baroni, E.; Minasi, M.G.; Ubaldi, F.; Rienzi, L.; Tesarik, J. ICSI in cases of sperm DNA damage: beneficial effect of oral antioxidant treatment. Hum Reprod. 2005, 20, 2590–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazout, A.; Dumont-Hassan, M.; Junca, A.M.; Cohen Bacrie, P.; Tesarik, J. High-magnification ICSI overcomes paternal effect resistant to conventional ICSI. Reprod Biomed Online. 2006, 12, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, E.; Scarselli, F.; Iacobelli, M.; Rienzi, L.; Ubaldi, F.; Ferrero, S.; Franco, G.; Anniballo, N.; Mendoza, C.; Tesarik, J. Efficient treatment of infertility due to sperm DNA damage by ICSI with testicular spermatozoa. Hum Reprod. 2005, 20, 226–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesarik, J.; Thébault, A.; Testart, J. Effect of pentoxifylline on sperm movement characteristics in normozoospermic and asthenozoospermic specimens. Hum Reprod. 1992, 7, 1257–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesarik, J.; Mendoza, C. Sperm treatment with pentoxifylline improves the fertilizing ability in patients with acrosome reaction insufficiency. Fertil Steril. 1993, 60, 141–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).