1. Introduction

Plates, as important steel materials, are widely used in infrastructure construction and mechanical manufacturing [

1]. The yield of plates is an important economic and technical indicator for evaluating enterprises' resource utilization and competitiveness. The main influencing factors of the yield is the shear loss caused by the restriction of the plan view pattern [

2]. Plate plan view pattern control (PVPC) is a very effective method to make the plate rectangular, reduce crop and edge losses, and improve the yield. Its basic idea is to predict the pattern of the rolled piece after rolling, and convert the volume of the irregular pattern into an abnormal thickness compensation amount given in the last pass of the sizing and broadening phase according to the "constant volume principle". This abnormal thickness distribution is used to improve the final rectangularity. The basic principle of the plan view pattern control is shown in

Figure 1.

Extensive research has been conducted by scholars on plan view pattern control. Early studies primarily adopted mechanism models, deriving theoretical equations for three-dimensional metal flow and spreading through basic laws such as the equal volume method and the minimum resistance method. These models provided a foundational basis for analyzing the plan view pattern of plates. For example, Ding [

3] established a mathematical model for the plan view pattern of plates to explore the variation law of deformation parameters during the rolling process. Liu [

4] used the energy method to develop an accurate prediction model for plate rolling. However, mechanism models often exhibit substantial errors due to the simplification and assumptions of physical phenomena. In contrast, the finite element analysis method can accurately predict stress, strain, and temperature distributions through fine discretization, adapting to material nonlinearity and complex boundary conditions. This not only enhances the accuracy of plan view pattern control but also provides more reliable support for optimizing process parameters.

Hu and Zhang [

5,

6] established plan view pattern control models for plates based on simulation and proposed new technologies such as the THP edge-free rolling process to improve slab yield. Xun [

7] employed the elasto-plastic finite element method to analyze the influence of rolling conditions on the plate plan view pattern, proposing a calculation formula for the plan view pattern curve. Yang et al [

8] established a plan view pattern prediction model based on the longitudinal length difference at plate head and tail, improving prediction accuracy through the relationship between metal volume and length difference, and verified the model's effectiveness through finite element simulation and experiments. Ding et al [

9] studied the influence of setting points and distances on the rectangularity of products using a controllable point set-ting method combined with finite element analysis, successfully increasing the pro-duction yield from 92.28% to 93.36%. Yin [

10] analyzed metal flow through simulating the rolling process, compared the plan view patterns under different rolling schedules, and obtained a comprehensive optimal rolling schedule. Masayuki Horie [

11] et al. studied the dog-bone rolling method and found that the dog-bone width and broadening ratio significantly influence the plastic deformation length and fish-tail length. When the width increases or the broadening ratio decreases, the fish-tail length in-creases. Gu [

12] used the finite element method to study the control of plate plan view pattern by flat and vertical rolls, proposed a theoretical model, and the simulation results matched the actual situation, reducing the difference in width elongation and effectively controlling the head convex shape. Wang [

13] analyzed the variation law of plate plan view pattern through finite element modeling, and improved the width accuracy by 27% after parameter optimization. Yao [

14] et al. established a prediction model and control model for plan view pattern control of wide plates based on the constant volume law, and applied the models on site, reducing the shear loss of products.

With the vigorous development of intelligent technologies, research on plate plan view pattern has been integrated with advanced technologies such as machine learning and machine vision. Machine vision detection technology [

15] is rapidly emerging in the industrial field, gradually replacing human eyes for measurement and judgment. Chen et al [

16] proposed a new strip shape recognition method, optimizing neural networks with orthogonal polynomials and binary trees to construct a hybrid model and improve recognition accuracy. Ma [

17] studied the selection of industrial cameras and image processing algorithms to realize online real-time recognition of plate con-tours and accurate positioning of crop positions for head and tail. He et al [

18] used improved image processing algorithms based on machine vision technology to re-al-time detect the position and angle information during the steel turning process, enabling real-time processing of detection data in complex production environments. Ding et al [

19] employed machine vision to measure the camber of plates, obtaining sub-pixel coordinates of the rolled piece edges and determining their plan dimensions to implement feedback control for camber defects. Yang [

20] achieved high - precision recognition and contour feature extraction of plates based on machine vision technologies such as binocular multi - group linear array cameras.

Machine vision technology combined with machine learning algorithms can analyze and process massive data and image information to realize monitoring, prediction, correction, and optimization of plate deformation, defects, and plan view patterns. Machine learning models aim to tap the potential in feature extraction and model construction for plate plan view patterns, deepening the intelligent research on plan view pattern control. Wang [

21,

22] built BP neural networks to establish metal rolling flow prediction models, though they faced challenges such as data deviation and long computation times. M.S. Chun [

23] established a multi-layer neural network model to predict width changes during plate rolling, determining the optimal broadening value to reduce edge trimming losses. Dong [

24] developed an ISSA-ANN plan view pattern prediction model based on on-site production data, optimizing initial weights and thresholds to overcome the problem that the traditional neural network was easy to produce local optimum. Jiao et al [

25] optimized the RBF neural network by using DBO algorithm, and developed a prediction and control model for plate plan view pattern. In practical on-site applications, the crop cutting loss area of irregular deformation in the plate can be reduced by 31%. Wu et al [

26] proposed an attention-based weight-adaptive multi-task learning framework for predicting and optimizing irregular shapes in hot rolling, optimizing the short-stroke process to achieve a 10.3% improvement in defect width deviation. Zhao [

27] studied the application of extreme learning machines in predicting the length of rolled pieces, optimizing the prediction model for the plate plan view pattern.

Currently, research work on intelligent optimal control of plate plan view pattern using machine vision inspection is based on pattern inspection of finished plates at the end of rolling. However, passes for plan view pattern control occur in the rough rolling stage, specifically at the final pass of sizing phase and broadsiding phase. Due to requirements of TMCP rolling process for plates, there is a holding temperature process after rough rolling stage. Multiple rolled pieces will first complete rough rolling stage and holding temperature before proceeding to subsequent rolling passes to become products. Therefore, product pattern detection results can not be followed by a rolled pieces for real-time correction, plan view pattern control optimization has a large lag. If an accurate description of final shape can be obtained immediately after the end of rough rolling, plan view pattern of next piece can be optimized and adjusted in time.

Based on above background, by reasonably arranging detection devices, intermediate slab plan view pattern of rolled piece can be obtained after rough rolling. Then, according to subsequent rolling process conditions, machine learning algorithms can be used to predict the final shape in advance, enabling timely feedback and optimization of plan view pattern control for next rolled piece. Existing actual data from product shape detection serves as both machine learning data source for model predicting final pattern from intermediate pattern and evaluation tool for the final control effect.

This paper takes a typical two-stand plate production line as the research object, deploying visual detection devices after both rough mill and finish mill to collect intermediate slab and final plate plan pattern data during rolling. Using intermediate slab pattern data and subsequent rolling schedule data as inputs, and corresponding final pattern prediction is obtained through machine learning algorithm as output result. Based one final pattern prediction, we evaluate effect of plan view pattern control and optimize control parameters, and optimize plan view pattern of subsequent rolled piece in real time. The actual measurement data of final plate pattern serves as ultimate evaluation for prediction and control models.

Figure 1.

Rolling process of PVPC [

25].

Figure 1.

Rolling process of PVPC [

25].

Figure 2.

Industrial camera installation position installation.

Figure 2.

Industrial camera installation position installation.

Figure 3.

intermediate slab head grey image.

Figure 3.

intermediate slab head grey image.

Figure 4.

Intermediate billet image processing flow: (a) binarization; (b) edge detection; (c) contour extraction.

Figure 4.

Intermediate billet image processing flow: (a) binarization; (b) edge detection; (c) contour extraction.

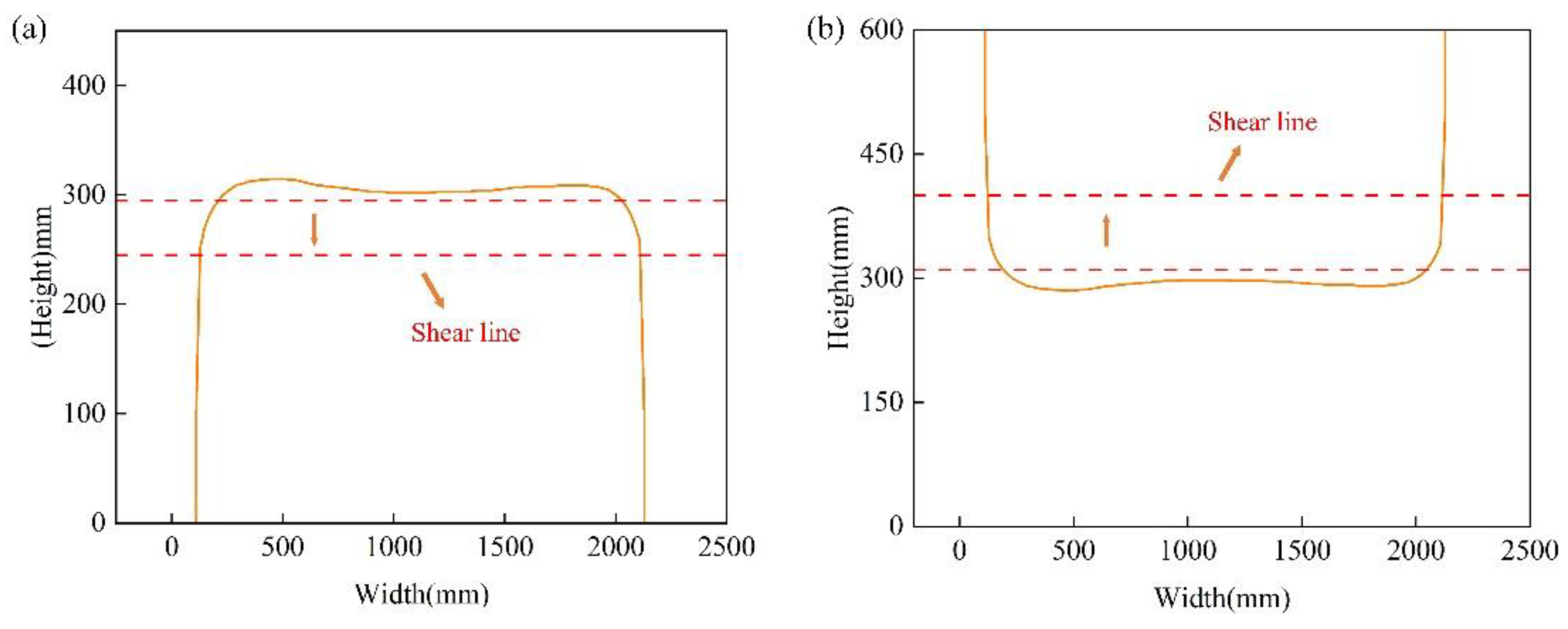

Figure 5.

Determination of the best shear line: (a) head; (b) tail.

Figure 5.

Determination of the best shear line: (a) head; (b) tail.

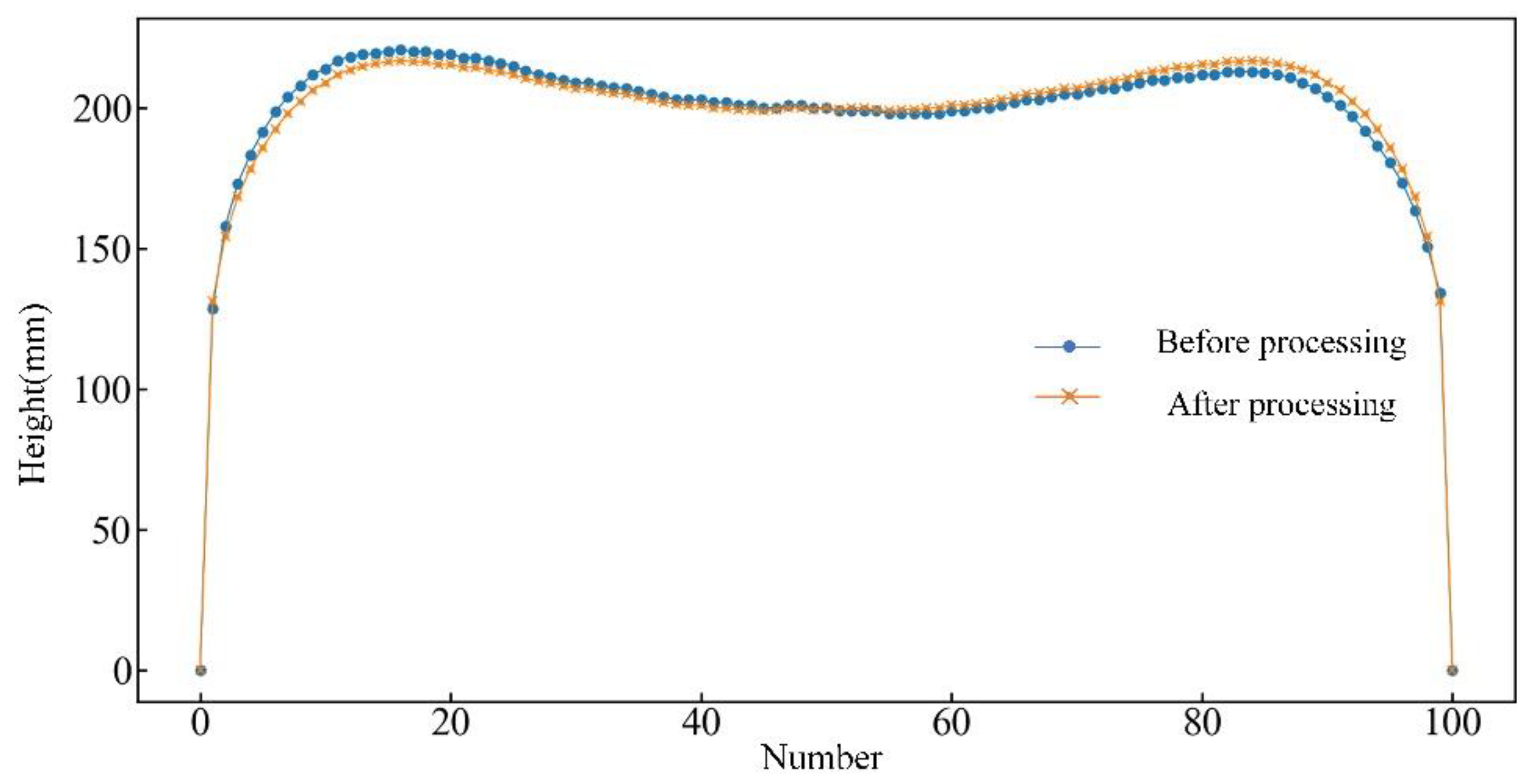

Figure 6.

Outline point coordinate processing diagram.

Figure 6.

Outline point coordinate processing diagram.

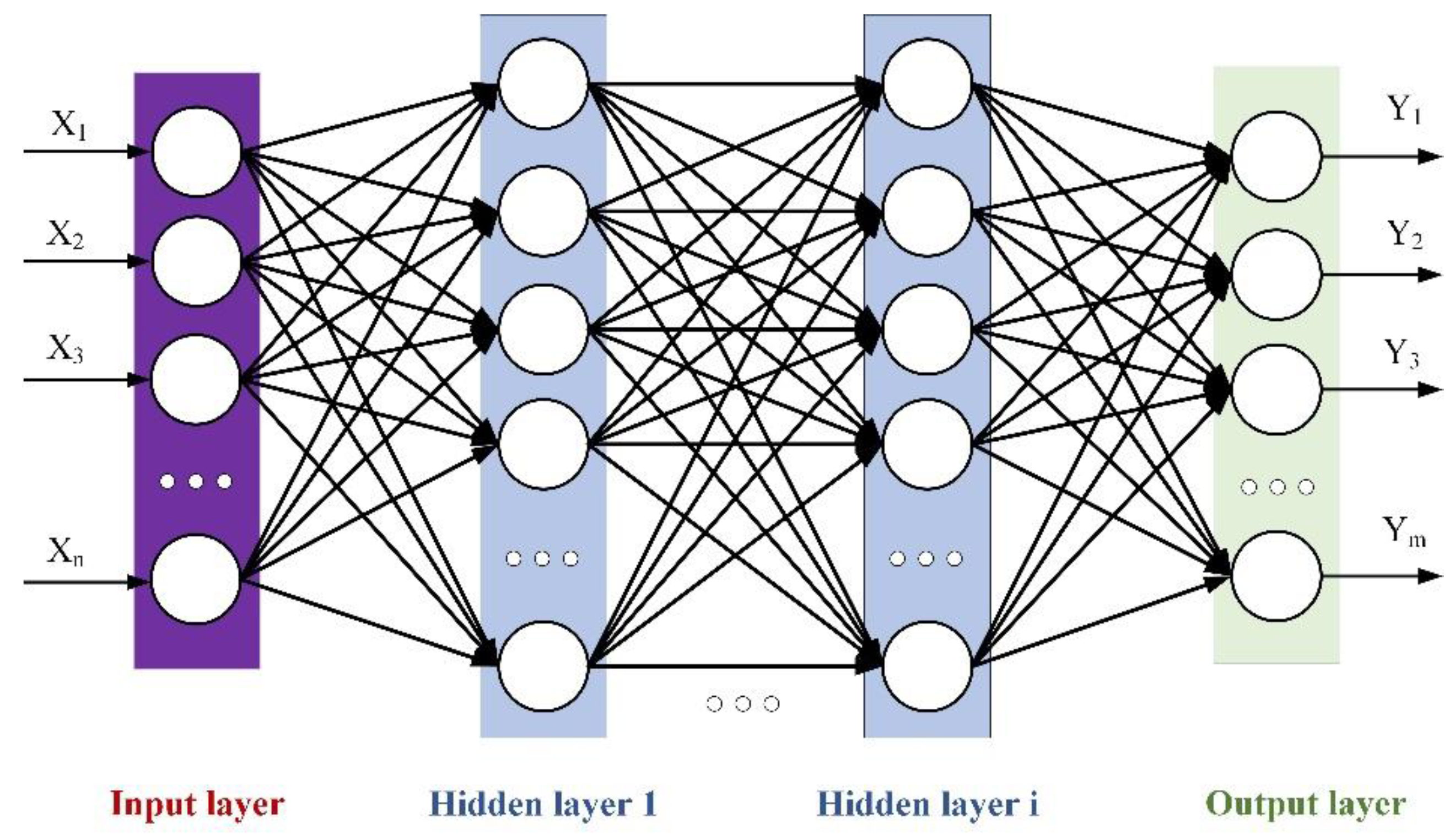

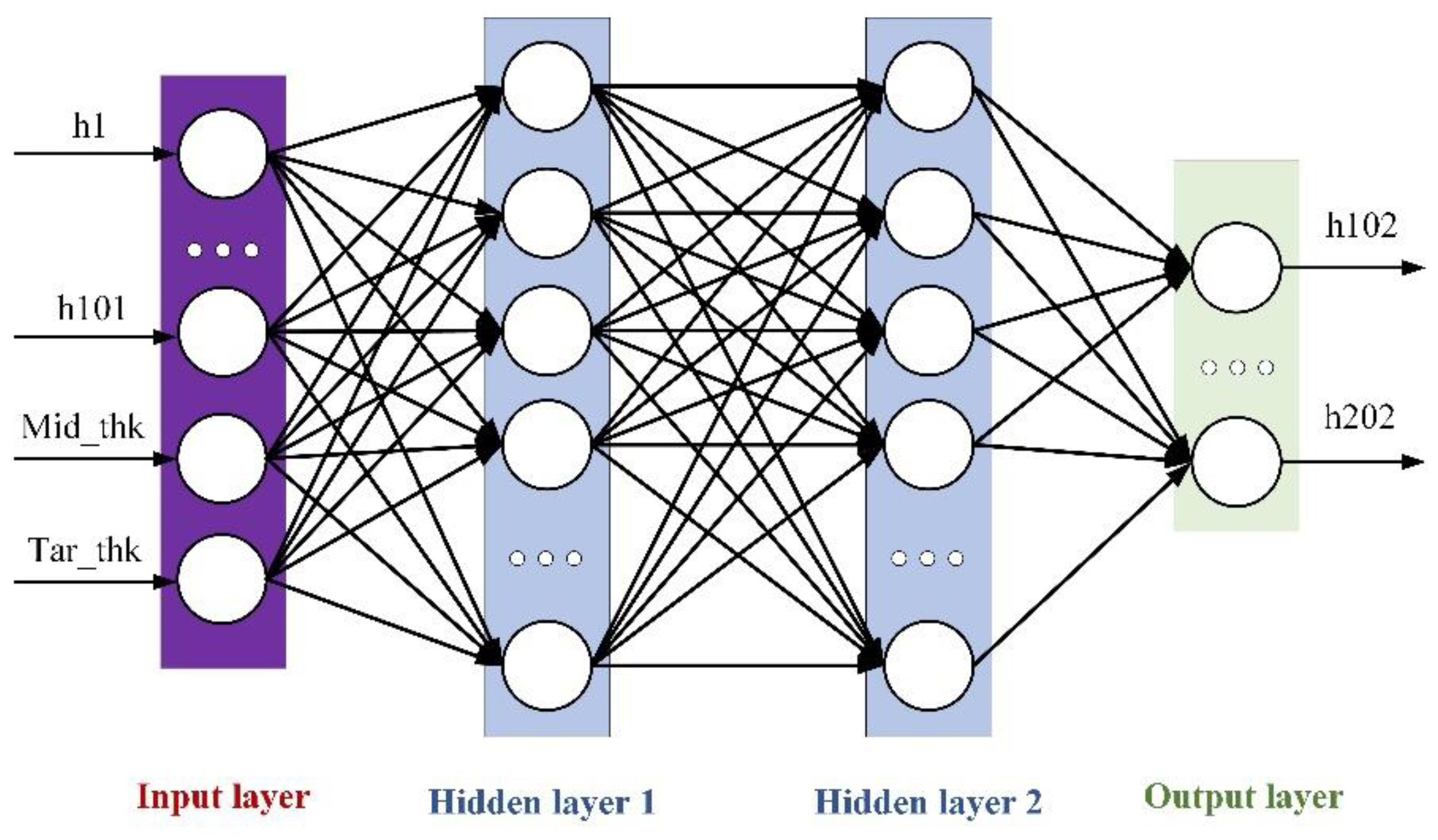

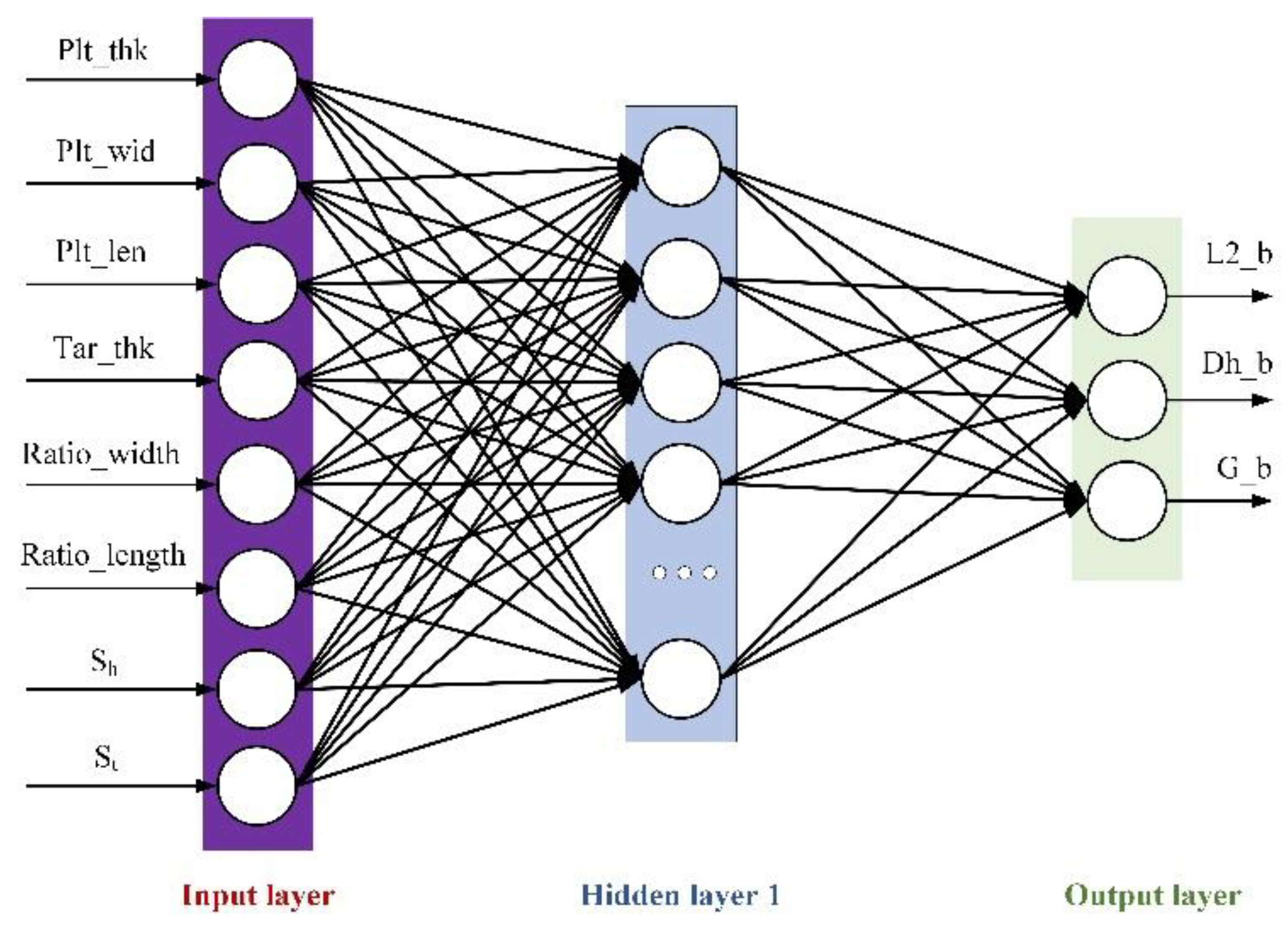

Figure 8.

DNN neural network diagram.

Figure 8.

DNN neural network diagram.

Figure 9.

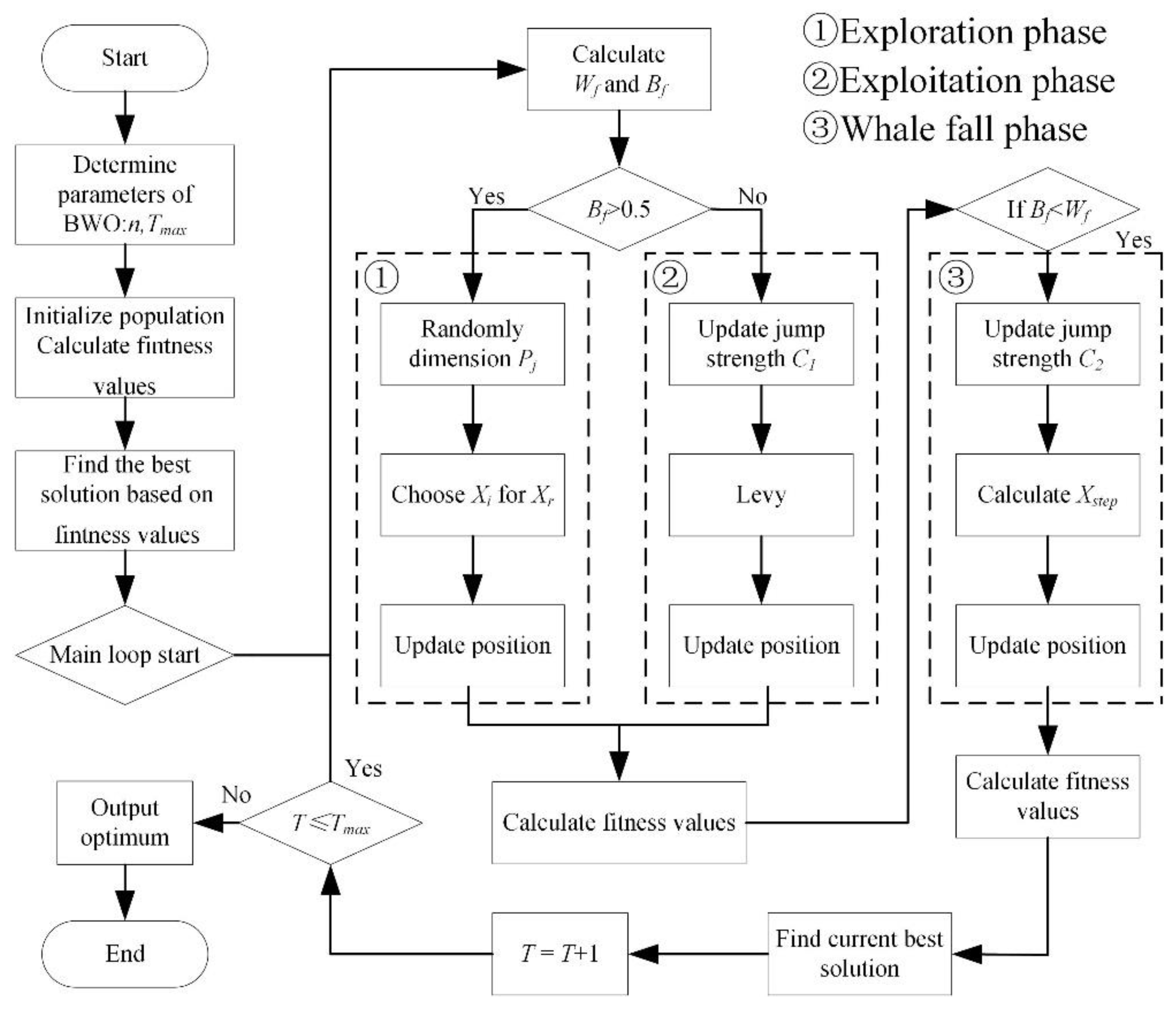

BWO algorithm flow.

Figure 9.

BWO algorithm flow.

Figure 10.

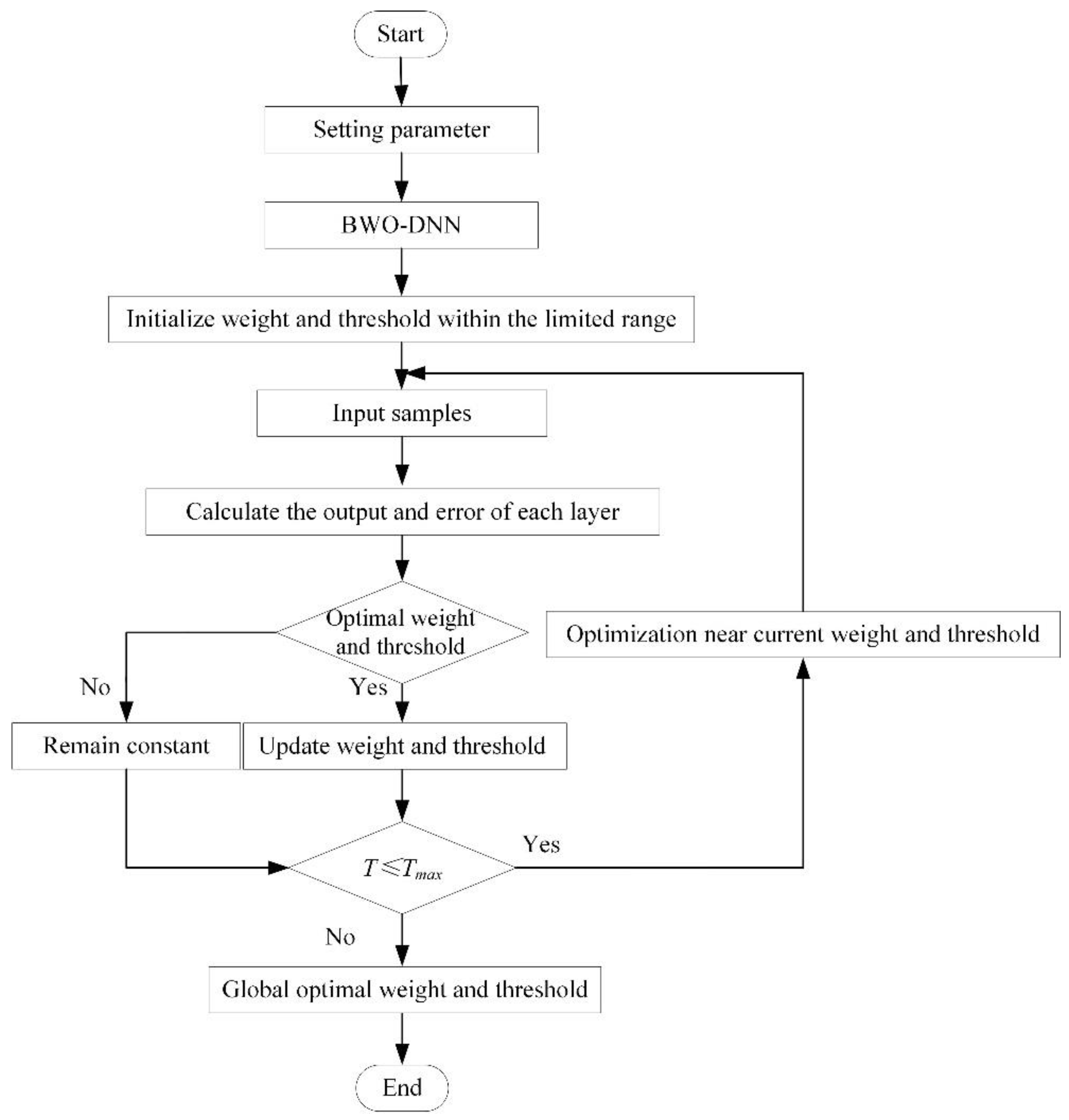

DNN-BWO algorithm flow.

Figure 10.

DNN-BWO algorithm flow.

Figure 11.

Plan view pattern prediction model.

Figure 11.

Plan view pattern prediction model.

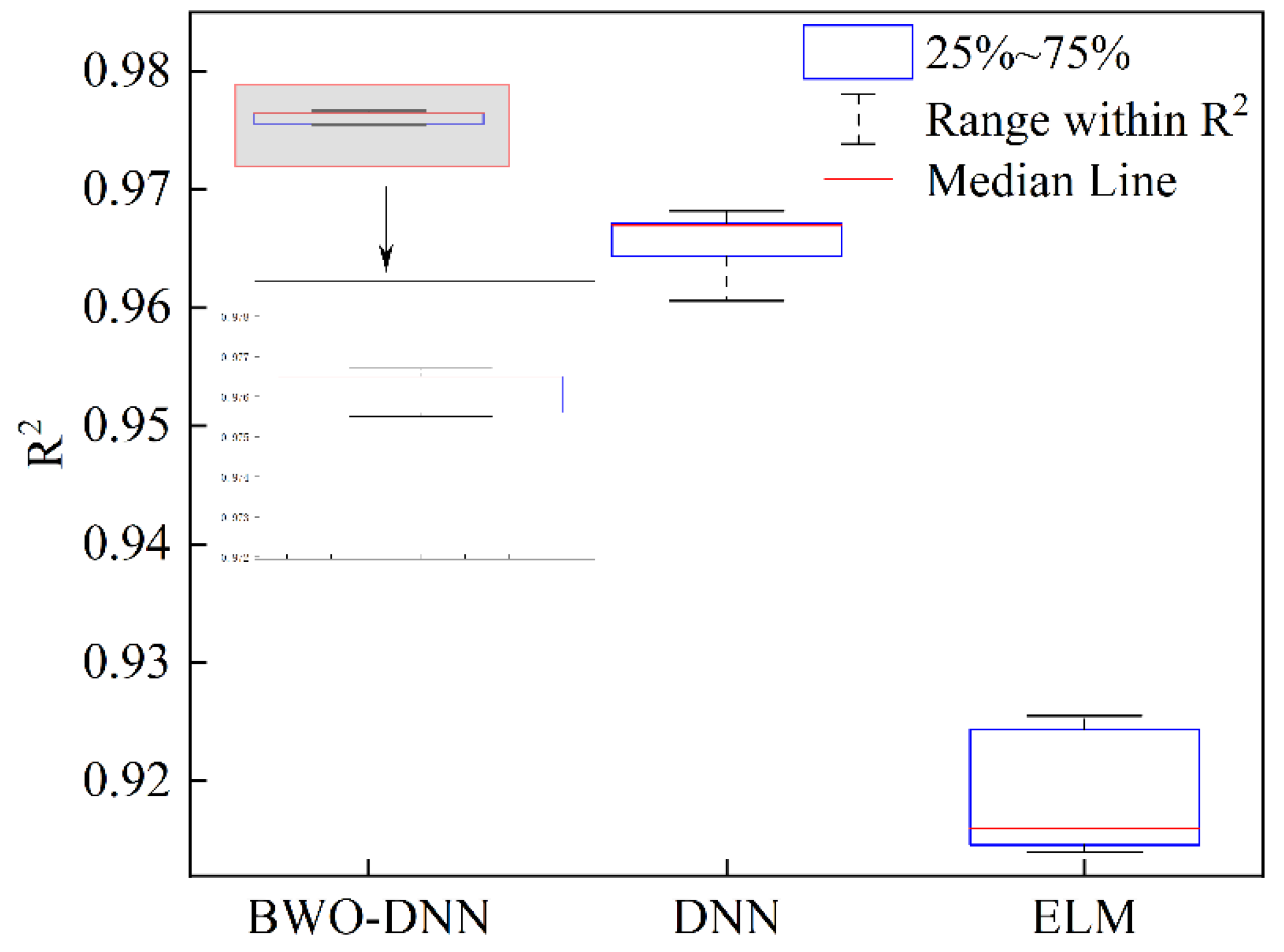

Figure 12.

The boxplot for the R2 value in multiple training sessions.

Figure 12.

The boxplot for the R2 value in multiple training sessions.

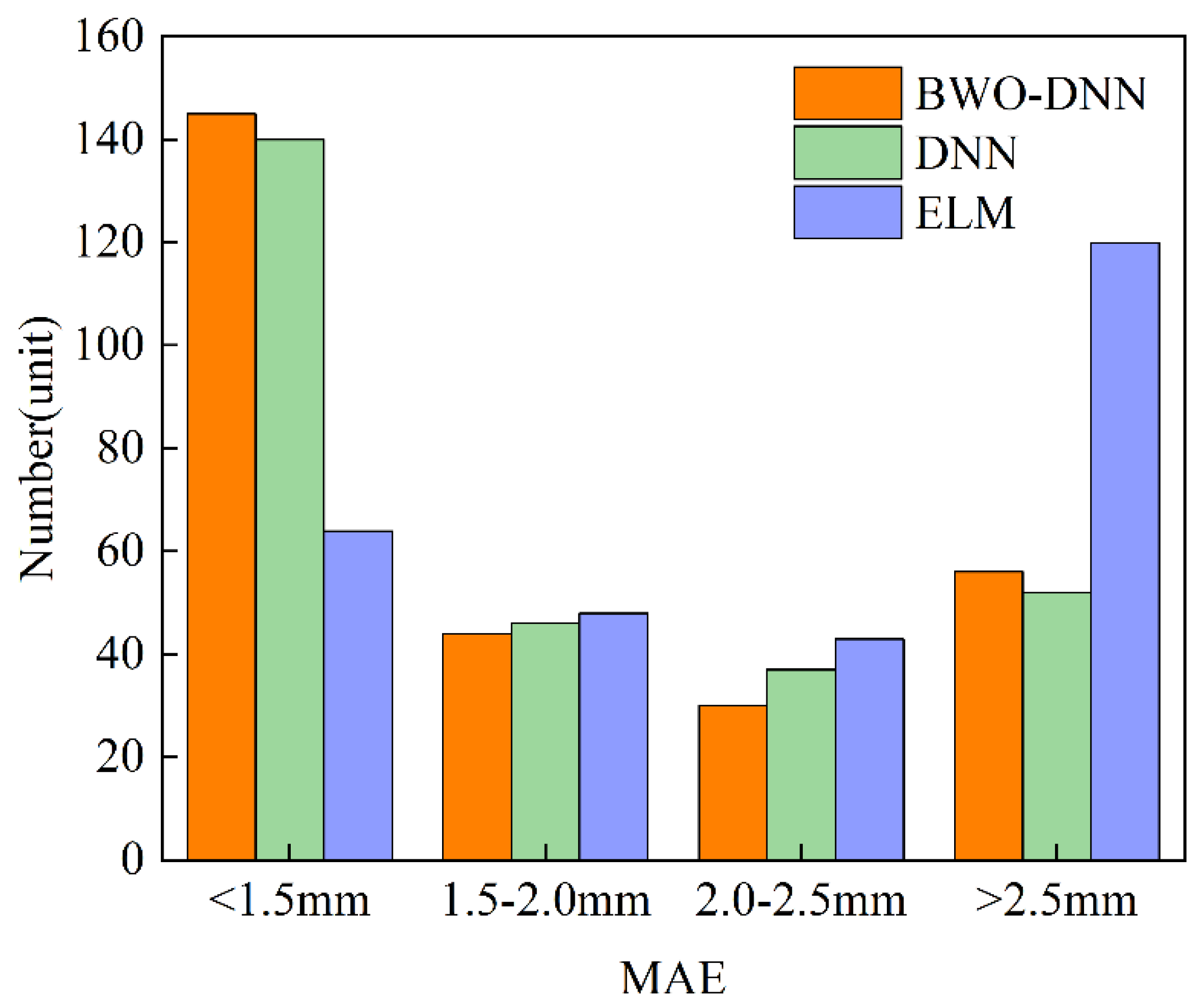

Figure 13.

MAE distribution of different algorithms.

Figure 13.

MAE distribution of different algorithms.

Figure 14.

Plan view pattern control model.

Figure 14.

Plan view pattern control model.

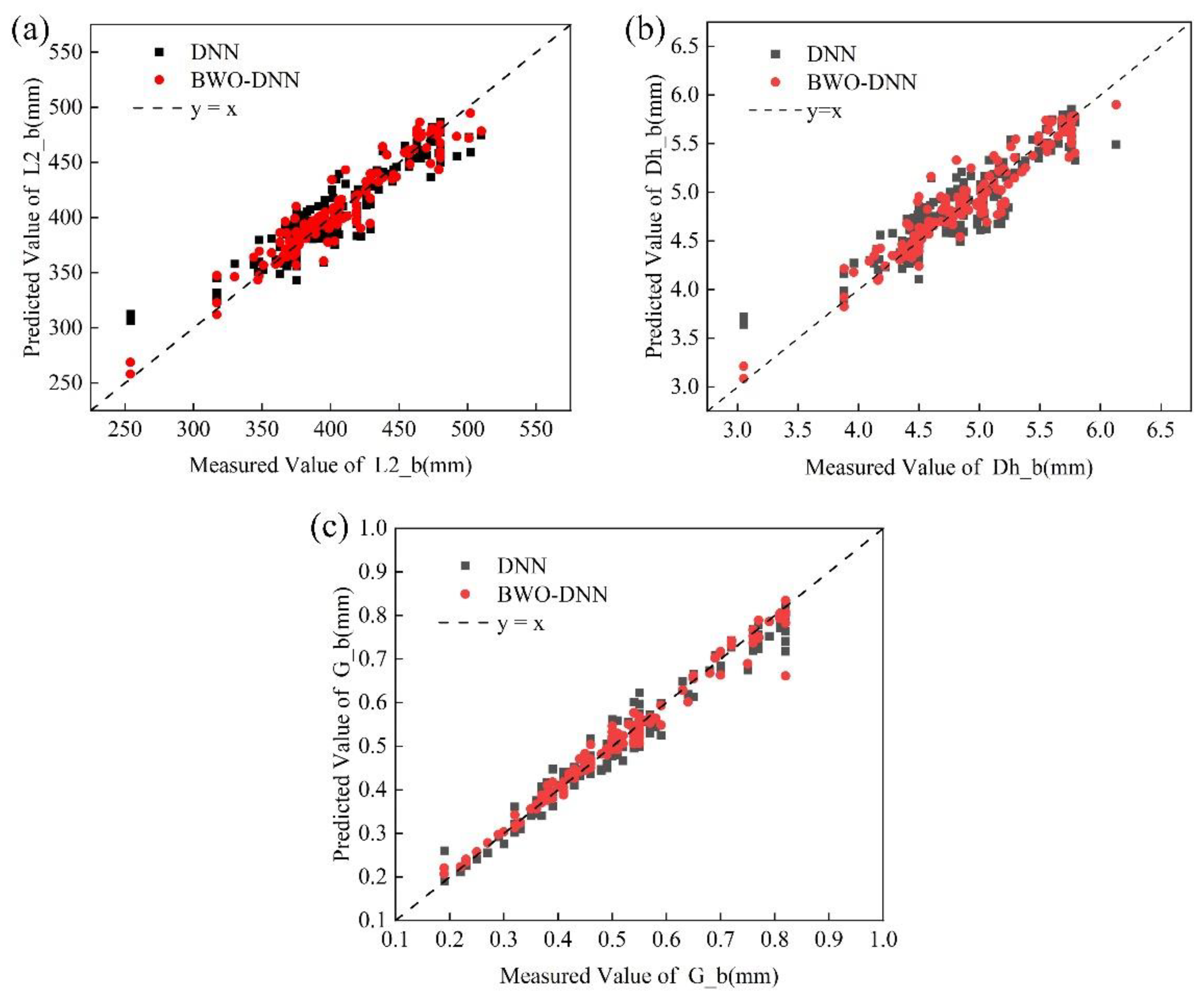

Figure 15.

BWO-DNN and DNN prediction results: (a) L2_b comparison results; (b) Dh_b comparison results; (c) G_b comparison results.

Figure 15.

BWO-DNN and DNN prediction results: (a) L2_b comparison results; (b) Dh_b comparison results; (c) G_b comparison results.

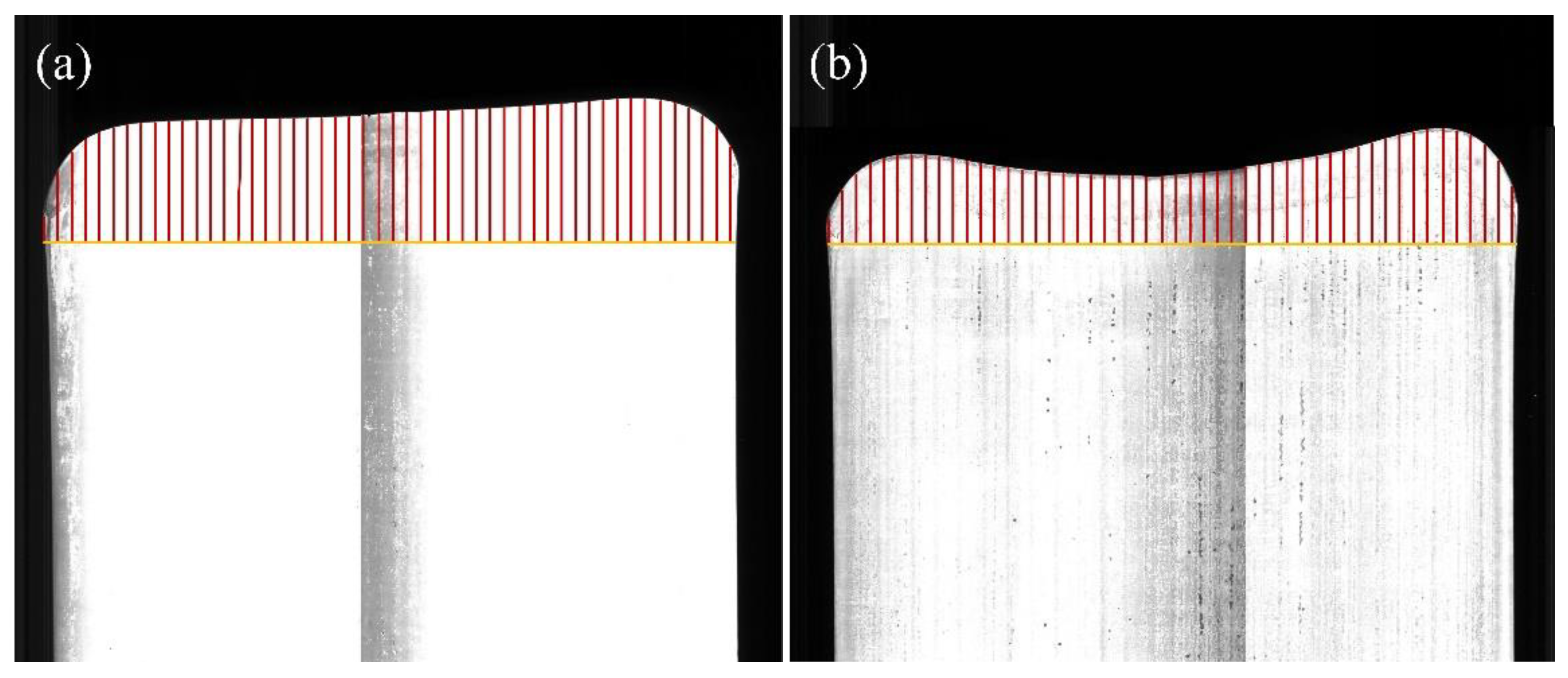

Figure 16.

Comparison of Plate Plan View Pattern Before and After Optimization: (a)Before optimization; (b) After optimization.

Figure 16.

Comparison of Plate Plan View Pattern Before and After Optimization: (a)Before optimization; (b) After optimization.

Table 1.

Data feature value summary.

Table 1.

Data feature value summary.

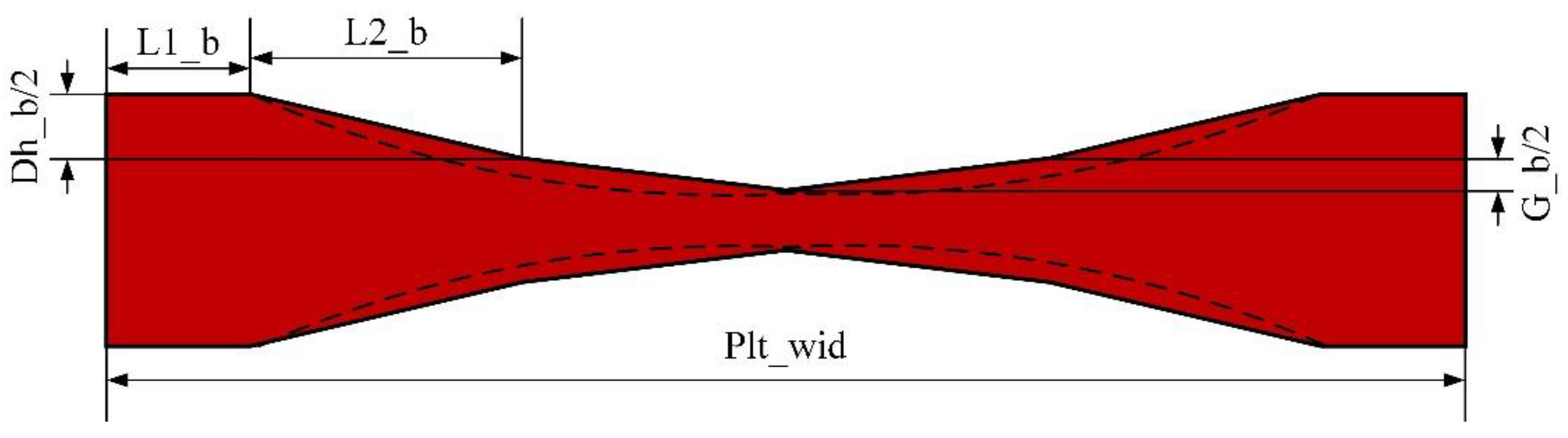

| Index |

Parameter |

Description |

Unit |

| V1 |

Plt_thk |

Slab thickness |

mm |

| V2 |

Plt_wid |

Slab width |

mm |

| V3 |

Plt_len |

Slab length |

mm |

| V4 |

Tar_thk |

Target thickness |

mm |

| V5 |

Ratio_width |

Broadening ratio after completion of rolling |

- |

| V6 |

Ratio_length |

Extension ratio after completion of rolling |

- |

| V7 |

L1_b |

PVPC parameter |

mm |

| V8 |

L2_b |

PVPC parameter |

mm |

| V9 |

Dh_b |

PVPC parameter |

mm |

| V10 |

G_b |

PVPC parameter |

mm |

| V11-V111 |

h1-h101 |

Y-value of intermediate slab contour points |

mm |

| V112-V212 |

h102-h202 |

Y-value of plate contour points |

mm |

| V213 |

Mid_thk |

Intermediate slab thickness |

mm |

| V214 |

Sh

|

Irregular area of head |

mm2

|

| V215 |

St

|

Irregular area of tail |

mm2

|

Table 2.

Summary of hidden layer and neuron number discussion.

Table 2.

Summary of hidden layer and neuron number discussion.

| hidden layers number |

number of neurons |

MAE/mm |

R2

|

| 1 |

128 |

3.823 |

0.9436 |

| 1 |

256 |

3.214 |

0.9498 |

| 2 |

128-128 |

3.566 |

0.9496 |

| 2 |

128-256 |

2.987 |

0.9657 |

| 2 |

256-256 |

3.554 |

0.9623 |

| 3 |

100-200-300 |

3.568 |

0.9532 |

Table 3.

Effect of population size and iterations of BWO-DNN.

Table 3.

Effect of population size and iterations of BWO-DNN.

| population size and iterations |

R2

|

MAE/mm |

| 30-100 |

0.9734 |

2.981 |

| 30-150 |

0.9742 |

2.978 |

| 30-180 |

0.9750 |

2.977 |

| 50-100 |

0.9752 |

2.975 |

| 50-120 |

0.9754 |

2.971 |

| 50-150 |

0.9758 |

2.969 |

| 50-180 |

0.9758 |

2.969 |

Table 4.

R2 values of different upper and lower limits.

Table 4.

R2 values of different upper and lower limits.

| value ranges |

R2

|

MAE/mm |

| -0.12~0.12 |

0.9758 |

2.969 |

| -0.1~0.1 |

0.9760 |

2.964 |

| -0.09~0.09 |

0.9760 |

2.964 |

| -0.08~0.08 |

0.9760 |

2.964 |

Table 5.

Summary of hidden layer and neuron number discussion.

Table 5.

Summary of hidden layer and neuron number discussion.

| Hidden layers numbers |

Number of neurons |

MAE/mm |

R2

|

| 1 |

32 |

1.621 |

0.9412 |

| 1 |

64 |

1.214 |

0.9431 |

| 1 |

128 |

1.206 |

0.9470 |

| 2 |

32-64 |

1.552 |

0.9423 |

| 2 |

64-128 |

1.571 |

0.9410 |

| 2 |

32-128 |

1.629 |

0.9399 |

| 3 |

32-64-128 |

1.680 |

0.9382 |

Table 6.

Effect of population size and iterations of BWO-DNN.

Table 6.

Effect of population size and iterations of BWO-DNN.

| Population size and iterations |

R2

|

MAE/mm |

| 20-50 |

0.9322 |

1.721 |

| 20-80 |

0.9389 |

1.716 |

| 20-100 |

0.9391 |

1.702 |

| 30-50 |

0.9426 |

1.627 |

| 30-80 |

0.9520 |

1.202 |

| 30-100 |

0.9520 |

1.202 |

| 50-50 |

0.9456 |

1.215 |

Table 7.

R2 values of different upper and lower limits.

Table 7.

R2 values of different upper and lower limits.

| Value ranges |

R2

|

MAE/mm |

| -0.30~0.30 |

0.9498 |

1.362 |

| -0.28~0.28 |

0.9546 |

1.212 |

| -0.25~0.25 |

0.9569 |

1.198 |

| -0.20~0.20 |

0.9553 |

1.182 |

| -0.18~0.18 |

0.9551 |

1.213 |

Table 8.

Effect of population size and iterations of BWO-DNN.

Table 8.

Effect of population size and iterations of BWO-DNN.

| Parameter |

Index |

R2

|

MAE/mm |

| |

BWO-DNN |

0.9471 |

6.2758 |

| L2_b |

DNN |

0.9446 |

6.9873 |

| |

ELM |

0.8805 |

11.7886 |

| |

BWO-DNN |

0.9437 |

0.0839 |

| Dh_b |

DNN |

0.9139 |

0.0996 |

| |

ELM |

0.8583 |

0.1529 |

| |

BWO-DNN |

0.9907 |

0.0109 |

| G_b |

DNN |

0.9862 |

0.0122 |

| |

ELM |

0.9631 |

0.0176 |

Table 9.

Summary of slab data.

Table 9.

Summary of slab data.

| Parameter |

Value |

| material |

AH36 |

| Plt_thk/mm |

220 |

| Plt_wid/mm |

2065 |

| Plt_len/mm |

2295 |

| Tar_thk/mm |

17.65 |

| Ratio_width |

1.179 |

| Ratio_length |

10.571 |