1. Introduction

The story of type 1 diabates mellitus (T1DM) is not only a chronicle of medical discovery but also a case study in the evolution of scientific thought. For much of recorded history, diabates was understood as a singular metabolic disorder a condition defined by emaciation, glycosuria, and a rapid course toward death. With the advent of insulin therapy in the early 20th century, diabates became treatable but remained etiologically obscure. It would take several decades, and the convergence of multiple lines of inquiry, for T1DM to be reclassified as an autoimmune disease. This reclassification was not just terminological; this marked a change in the underlying the way people thought about the disease itself. Where once T1DM was viewed as a passive failure of pancreatic function, it is now recognized as the result of active immune-mediated destruction of insulin-producing β-cells. The transition was fueled by technological innovations such as autoantibody assays and HLA genotyping as well as by conceptual realignments that drew from immunology, genetics, and systems biology.

In this review, we examine the chronological and epistemological transformation of T1DM. Beginning with ancient medical texts and early anatomical observations, we follow the progression through the insulin era, the recognition of disease heterogeneity in the mid-20th century, and the autoimmune a radical conceptual shift of the 1970s. We then explore how the consolidation of immunological evidence led to new classification systems, prevention trials, and finally, disease-modifying therapies in the 21st century. Our analysis integrates classical and contemporary literature (

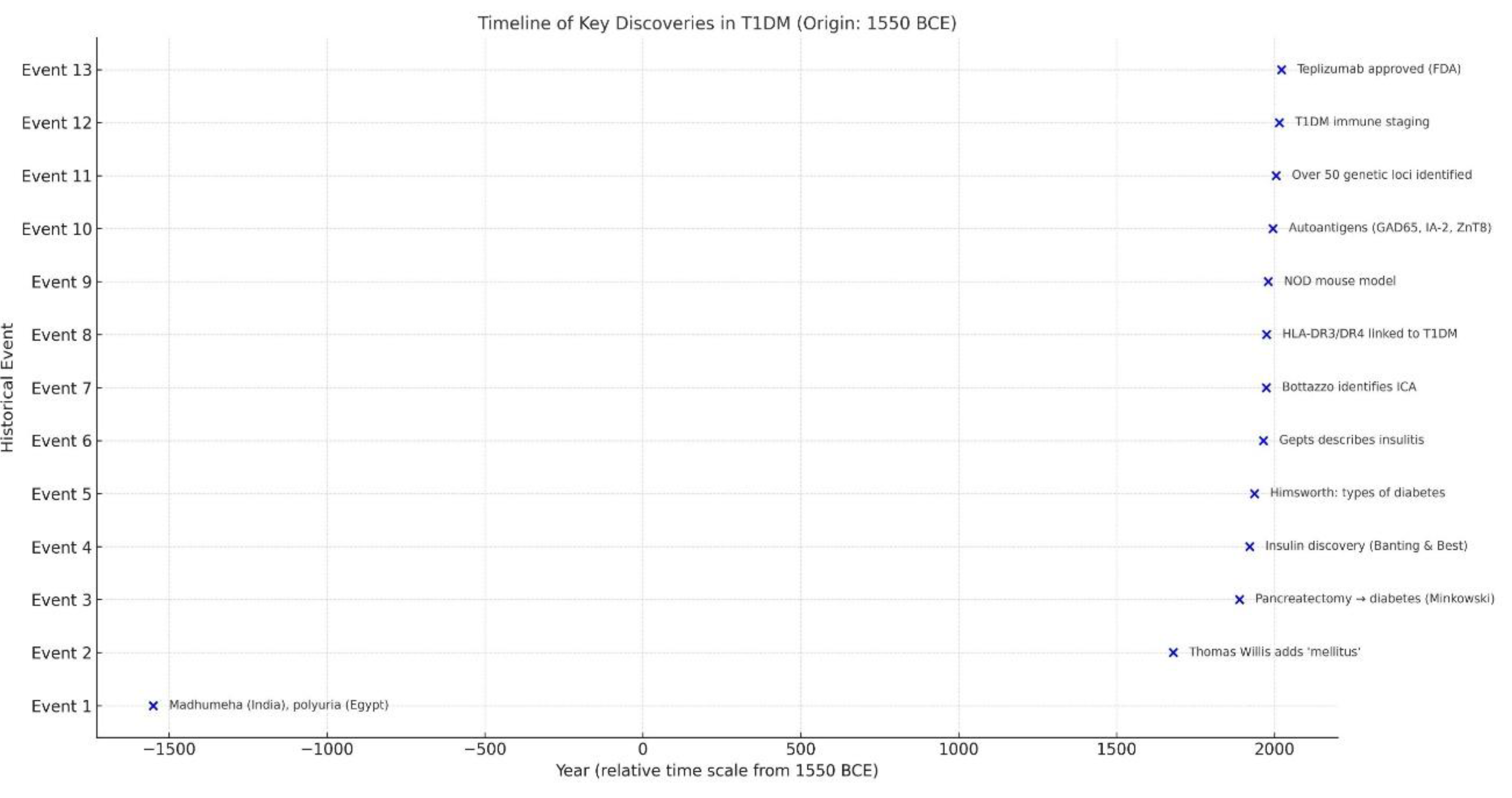

see Figure 1 for a visual timeline of key discoveries in T1DM), including the recent comprehensive review Herold et al. , and considers how shifts in scientific instruments, institutional priorities, and interpretative frameworks have redefined not only how T1DM is treated, but what it is [

1]. In doing so, we aim to contextualize T1DM as a model for understanding how diseases evolve in the collective imagination of science and medicine.

This timeline highlights 13 major milestones in the conceptual and scientific evolution of T1DM, spanning from early clinical descriptions in antiquity to modern immunogenetic discoveries and therapeutic breakthroughs. The horizontal axis represents the year of discovery, while the vertical axis lists the chronological order of events.

2. Before Insulin: Diabetes in Antiquity and the Pre-modern Era

The origins of what we now identify as T1DM trace back over three millennia. In the Ebers Papyrus (circa 1550 BCE), Egyptian physicians described polyuric syndromes marked by excessive urination, a hallmark of hyperglycemia [

2]. Ancient Indian Ayurvedic texts referred to Madhumeha, or “honey urine,” reflecting an early recognition of glycosuria. The Greek physician Aretaeus of Cappadocia coined the term “diabetes” in the 2nd century CE, from the word siphon, to describe the seemingly uncontrollable flow of fluids through the body. In the 17th century, Thomas Willis famously added mellitus meaning “sweet” after tasting patients’ urine and noting its sugary flavor [

3]. Despite such detailed phenomenology, the nature of the diesease remained obscure. The humoral theory of diesease prevailed, attributing symptoms to imbalances of bodily fluids. Even when anatomical studies emerged during the Renaissance, little was understood about the pancreas. Paracelsus, for example, observed crystalline substances in diabetic urine but could not link them to sugar or pancreatic pathology. It wasn’t until the late 19th century that researchers like Étienne Lancereaux proposed a distinction between “diabète maigre” and “diabète gras,” hinting at heterogeneity, though without molecular basis [

4]. A major conceptual leap occurred in 1889, when von Mering and Minkowski removed the pancreas from dogs, inducing severe diabetes a key demonstration that pancreatic secretions were essential to glucose homeostasis [

5]. However, without a clear understanding of hormones, their work did not immediately resolve the diesease’s mystery. In the early 20th century, tretment strategies focused on extreme caloric restriction, such as the Allen diet, which delayed death but led to starvation [

6].

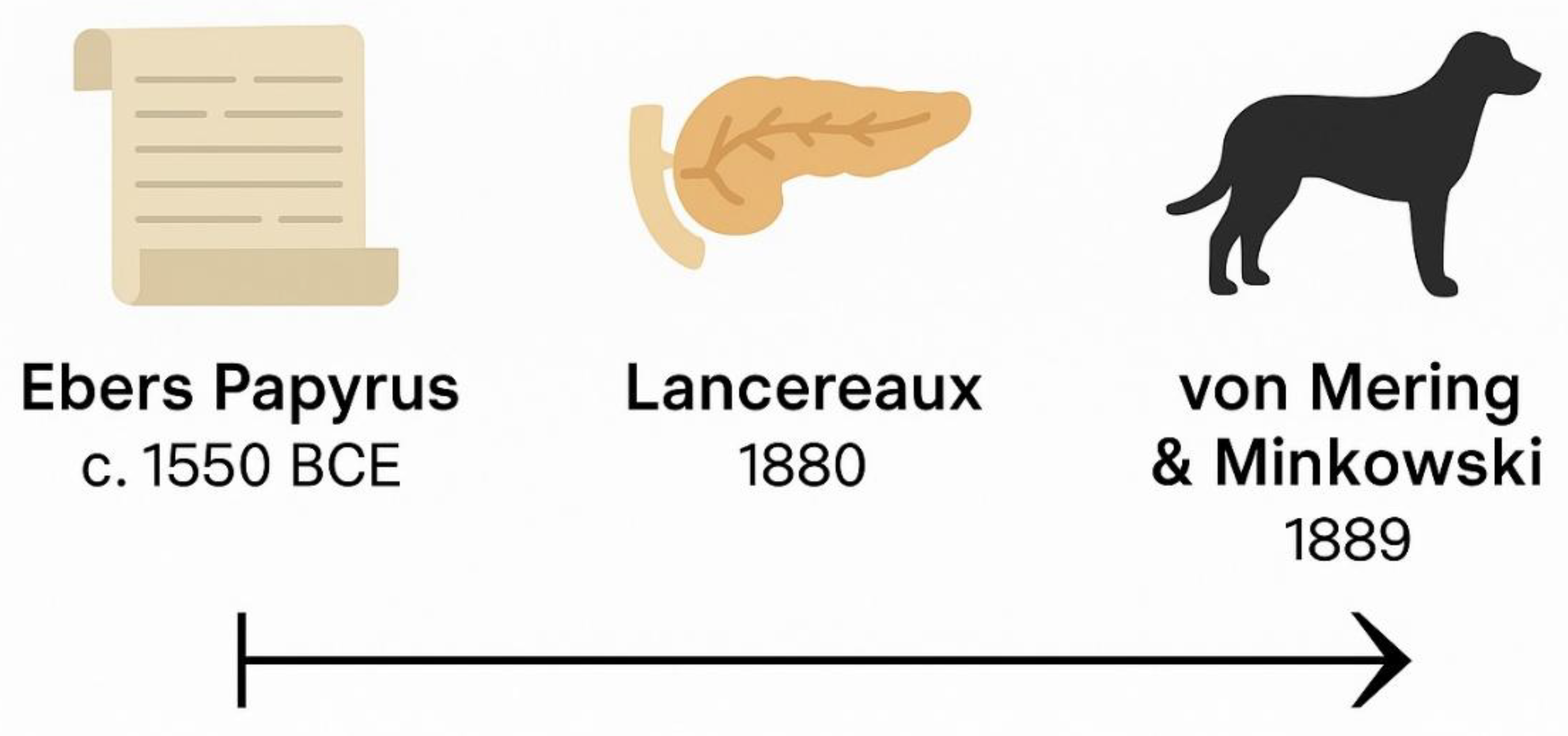

Crucially, this entire era framed diabetes as a uniform metabolic disorder. No distinction between types was made, nor was the imune system considered relevant (

See Figure 2 for a visual summary of key milestones in diabetes history prior to the discovery of insulin). The discovery of insulin has been a milestone and has truly revolutionized both the therapy and the prognosis of the diabetes, one of the diseases most studied in the history of medicine [

7]. Histopathological clues such as occasional lymphocytic infiltration were either missed or dismissed [

8]. Thus, the pre-insulin age laid a conceptual foundation that would both advance and constrain future thinking: diabetes was metabolic, not immunological; singular, not heterogeneous.

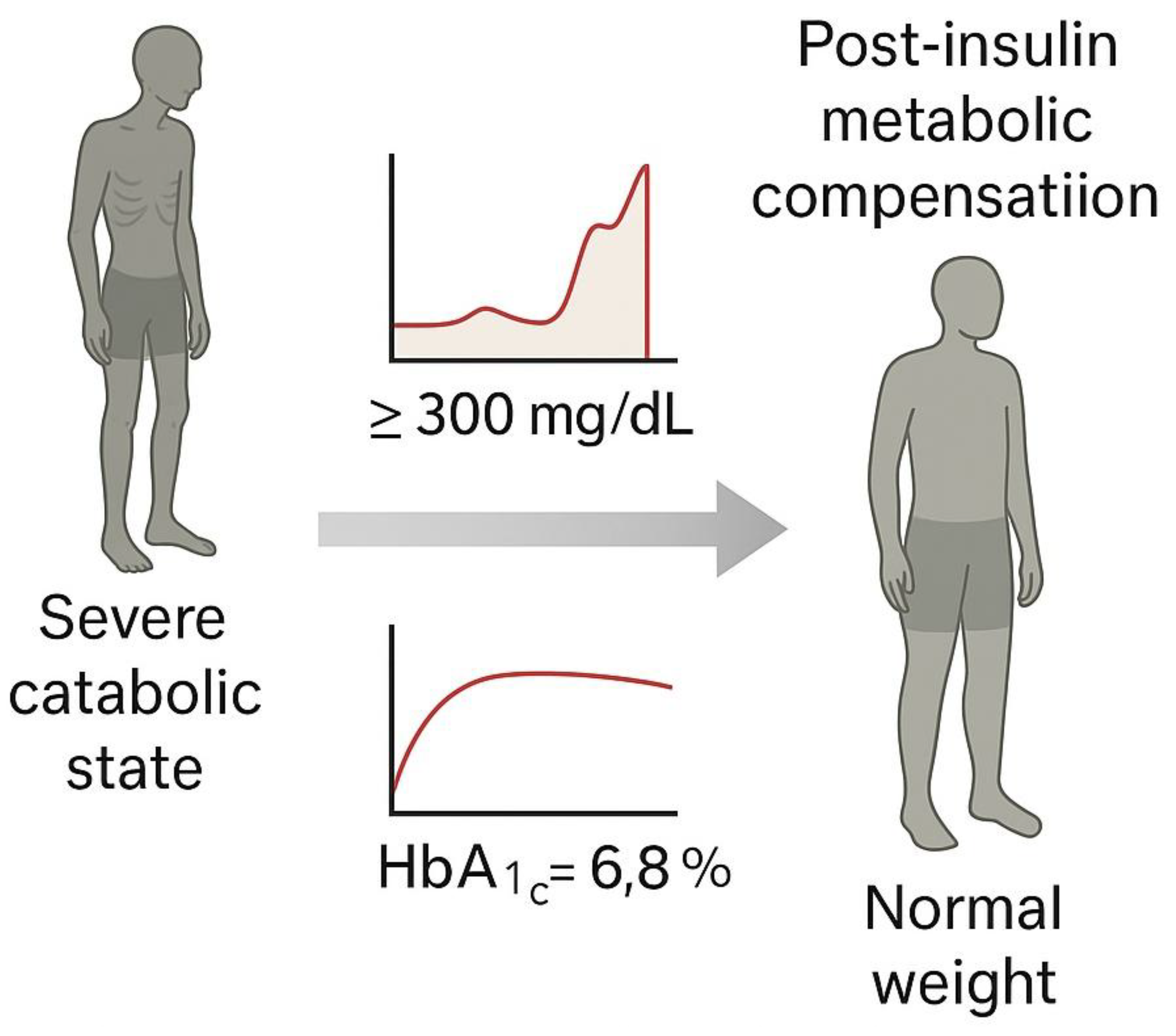

Before 1921, a diagnosis of diabetes in children almost invariably led to death, often preceded by extreme emaciation and coma (Joslin, 1916). The discovery and therapeutic introduction of insulin by Banting and Best in 1921 dramatically reversed this prognosis, allowing patients to survive, gain weight, and live for decades (Michael Bliss, 1982; Rosenfeld, 2002). However, this therapeutic breakthrough also entrenched a metabolic framework of disease understanding, which delayed the recognition of immune-mediated mechanisms for decades (Herold et al., 2024).

3. The Insulin Revolution: From Fatal Diagnosis to a Chronic Condition (1921–1950)

The discovery of insulin in the early 1920s represents one of the most dramatic shifts in the history of medicine [

7]. Prior to this event, a diagnosis of diabetes especially in children and adolescents was effectively a death sentence. Treatments such as the Allen starvation diet, while occasionally extending life, severely restricted caloric intake and often led to malnutrition [

6]. In 1921, Canadian physician Frederick Banting and medical student Charles Best, working in J.J.R. Macleod’s laboratory at the University of Toronto, succeeded in isolating a pancreatic extract that dramatically reduced blood glucose in diabetic dogs [

9]. In January 1922, they administered this extract later refined and named insulin to 14-year-old Leonard Thompson, marking the beginning of a therapeutic revolution [

10].

Within a year, commercial production of insulin began through partnerships with Eli Lilly and Connaught Laboratories, and by 1923, Banting and Macleod had received the Nobel Prize [

9]. While insulin saved lives and became a cornerstone of diabetes management, it also cemented the view of diabetes as a purely metaboilic disorder, characterized by insulin deficiency and hyperglycemia (

See Figure 3 for a conceptual depiction of the transformative clinical impact of insulin therapy on type 1 diabetes.). This framework would dominate thinking for the next five decades [

11,

12].

During this era, no clear distinction was made between what are now known as type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Although Harold Himsworth proposed the classification of insulin-sensitive and insulin-insensitive diabetes in 1936, this remained a metaboilic differentiation, not an etiological one [

11]. Autopsy studies occasionally showed lymphocytic infiltration of the islets, but these were largely dismissed as non-specific [

13].

Importantly, the overwhelming clinical success of insulin paradoxically suppressed further etiological inquiry. As [

1] argue, the therapeutic efficacy of insulin reinforced the metaboilic model and delayed the integration of immune-based hypotheses. Even in the face of growing recognition of autoimmune dieseases in the mid-20th century such as Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and Addison’s disease diabetes remained conceptually isolated from immunological thinking [

14,

15].

This period thus laid the groundwork for both progress and a fundamental change in medical framing . While it transformed diabetes care, it also entrenched assumptions that would only be challenged in the 1970s with the discovery of islet autoantibodies and the rediscovery of insulitis [

13,

16].

4. Heterogeneity and the Pre-Autoimmune Puzzle (1950–1970)

In the mid-20th century, the growing availability of clinical data began to challenge the idea of diabetes mellitus as a homogeneous disorder. As Stefan Fajans & Conn in 1960 noted, “These diabetic subjects do not spontaneously present themselves to the physician or researcher; it is the investigator who must find them by testing asymptomatic relatives of known diabetic patients”(Fajans & Conn, 1960).

Physicians observed striking differences in disease onset, progression, and therapeutic response across age groups. Pediatric patients typically presented with rapid onset of symptoms, profound insulin deficiency, and a high risk of ketoacidosis, while adult patients often showed a more indolent course, with varying degrees of insulin dependence [

18]. Despite these differences, the notion of diabetes as a single metabolic entity persisted in textbooks and clinical practice [

19].

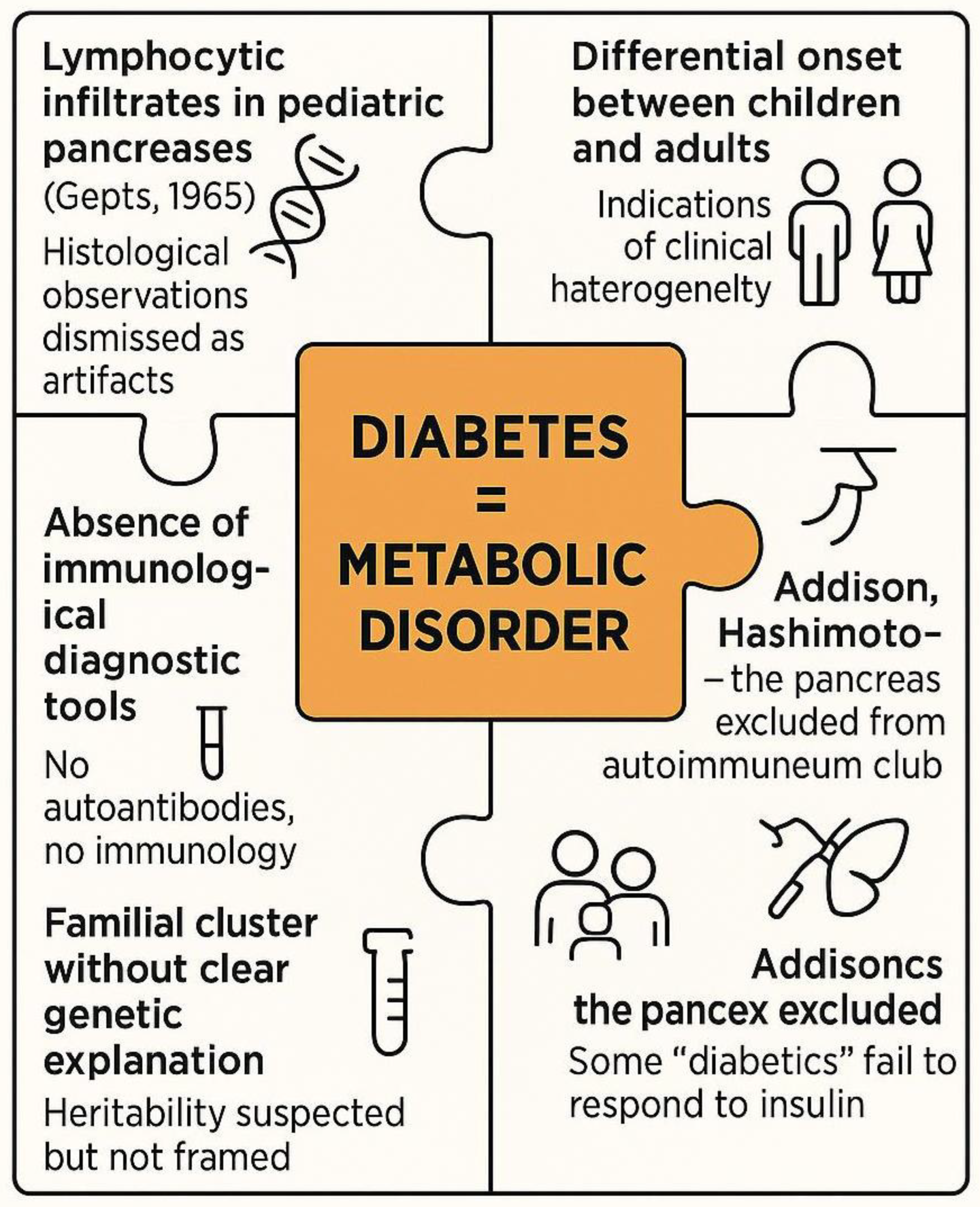

The possibility of underlying heterogeneity remained underexplored in part because of the absence of mechanistic tools. Biomarkers for immune activity were nonexistent, and pancreatic histopathology was rarely performed ante mortem. Nonetheless, isolated autopsy reports such as those later compiled by Gepts revealed the presence of lymphocytic infiltration in the islets of Langerhans, suggesting an inflammatory, perhaps immune-mediated, process [

13]. These findings, however, were often dismissed as nonspecific or artefactual [

20].

During the same period, autoimmune dieseases were gaining recognition in other organ systems. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Addison’s diesease, and pernicious anemia were increasingly understood as immune-mediated pathologies [

14]. Yet the conceptual link between diabetes and autoimmunity remained tenuous. The pancreas was not yet viewed as a potential target of immune aggression, and diabetology remained largely under the influence of endocrine and metaboilic frameworks [

21].

Genetic studies were equally limited, though familial clustering of diabetes was observed, prompting speculation about inherited predisposition [

22]. Without HLA typing or genome-wide tools, however, these hypotheses lacked confirmatory evidence [

23]. Immunology and endocrinology, still distinct disciplines, had not yet converged in the study of diabetes.

The terminology used during this period further obscured diesease subtypes. The labels “juvenile-onset” and “maturity-onset” diabetes, though descriptive, lacked pathophysiological clarity and reinforced the false assumption that diabetes was a temporally stratified but mechanistically uniform condition [

24].

This era, therefore, represents a critical liminal phase (

See Figure 4). The signs of autoimmune involvement were present but uninterpreted, like puzzle pieces without a framework. Only in the 1970s, with the discovery of islet autoantibodies and the rise of immune-centric models, would these fragments begin to coalesce into a coherent immunological narrative [

16].

5. The Autoimune Paradigm Shift (1971–1976)

The period between 1971 and 1976 marks a pivotal turning point in the conceptual history of T1DM. It was during these years that the disease underwent a Kuhnian full-on change of lens from a metabolic deficiency to an autoimune pathology [

25]. Prior to this, the idea that the immune system could play a causal role in β-cell destruction remained speculative and marginal within mainstream endocrinology. As noted in a retrospective analysis, "the lack of understanding, in humans, of the role for the immune responses underlying β-cell destruction in general but, in particular, the absence of specific markers of autoimmunity, made it difficult to establish a direct link between immune mechanisms and the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes" [

26].

A central breakthrough came in 1974 when Bottazzo and colleagues published their discovery of islet cell antibodies (ICA) in newly diagnosed diabetic children, especially those with polyglandular autoimune syndromes [

16]. This provided the first serological evidence of autoimmunity against pancreatic islets, fundamentally challenging the insulin-centric view of disease pathogenesis. Parallel to this, advances in histopathology had already begun to suggest a role for the imune system. Gepts (1965) had documented lymphocytic infiltration later termed “insulitis” in the pancreata of children who had died shortly after diagnosis, although these findings were initially regarded as incidental[

13].

By mid-decade, accumulating evidence from both histological and immunological fronts began to align. Several groups replicated ICA detection and extended findings to broader populations, including first-degree relatives of patients [

15]. The growing recognition of autoimune polyendocrine syndromes, including Addison’s disease and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, further bolstered the plausibility of a shared imune etiology [

14,

27,

28].

The introduction of HLA typing provided additional weight. Studies by Cudworth and Woodrow (1975) demonstrated a significant association between juvenile-onset diabetes and specific HLA haplotypes, particularly DR3 and DR4, establishing a genetic–imune axis of susceptibility [

29]. These insights were reinforced by later findings in monozygotic twins and population-level cohorts [

30].

Despite the strength of this emerging model, resistance from the clinical community was not uncommon. As Herold et al. highlight, many practitioners remained skeptical, anchored in the success of insulin therapy and unaware of imune-mediated mechanisms operating years before clinical onset [

1]. The autoimune model initially lacked therapeutic application there was no intervention to “treat” autoimmunity making it less attractive to practicing diabetologists (

see Figure 5).

Nevertheless, this period crystallized the autoimmune hypothesis and redefined T1DM not merely as a hormonal deficiency but as an immune-mediated process. This paradigm shift was substantiated by the identification of islet autoantibodies and a strong association with specific HLA class II alleles, underscoring the immunogenetic basis of the disease [

31]. Furthermore, the conceptualization of T1DM as a progressive, staged autoimmune disease emerged, delineating a sequence from asymptomatic autoimmunity to overt clinical diabetes, thereby providing a framework for early prediction and intervention strategies [

32,

33].

Key discoveries between 1971 and 1976, including the histological reevaluation of insulitis, the identification of islet autoantibodies, and the association of T1DM with HLA class II alleles catalyzed a Kuhnian shift in understanding the disease as autoimmune rather than purely metabolic.

6. Consolidating Autoimmunity: From Experimental Models to Human Trials (1980–2000)

Following the paradigm shift of the 1970s, the two final decades of the 20th century saw the consolidation of T1DM as a prototypical autoimmune disease. Early findings such as the presence of islet cell autoantibodies and pancreatic insulitis had laid the groundwork, but it was in the 1980s and 1990s that these observations were mechanistically connected through a combination of animal models, human studies, and genetic insights [

34].

The non-obese diabetic (NOD) mouse became an indispensable tool during this period. This animal model developed spontaneous autoimmune diabetes that mirrored human T1DM in both histology and immunopathogenesis [

35,

36]. The NOD mouse enabled researchers to investigate the roles of autoreactive T cells, antigen-presenting cells, and inflammatory cytokines in β-cell destruction [

37,

38]. These findings supported parallel immunological mechanisms in human disease, particularly as similar immune cell infiltrates were detected in pancreatic samples from newly diagnosed patients [

39,

40].

Autoantigen discovery was another cornerstone of this era. Beyond islet cell antibodies, specific autoantigens such as insulin itself, GAD65, IA-2, and ZnT8 were identified, allowing for improved stratification of disease risk [

41,

42].

Studies showed that the presence of multiple autoantibodies predicted progression to clinical diabetes, especially among genetically predisposed individuals [

43,

44].

This led to the formulation of a disease "staging" model based on immune markers, later refined in the 21st century.

Genetics also gained prominence. The association of T1DM with HLA-DR3 and DR4 alleles was confirmed in large-scale studies, and non-HLA genes such as INS, PTPN22, and CTLA4 were linked to immune regulation and disease susceptibility [

45,

46]. These findings demonstrated that T1DM was a complex polygenic disease, shaped by both immunogenetic and environmental interactions [

47].

Clinical translation was more difficult. Trials using cyclosporin A showed some promise in preserving residual β-cell function but were marred by nephrotoxicity and relapse upon discontinuation [

48,

49]. Other immunotherapies, including oral insulin and nicotinamide, failed to prevent disease onset in high-risk individuals [

50,

51,

52].

Despite these setbacks, this era solidified T1DM’s place in the autoimmune canon (

see Figure 6). It marked a transition from observation to mechanistic exploration, setting the stage for precision immunology and interventional trials in the 21st century [

1,

53].

Spanning animal models, antigenic targets, genetic discoveries, and immunotherapy trials, this period established type 1 diabetes as a prototypical organ-specific autoimmune disease and laid the groundwork for translational immunology.

7. The Immunological Turn of the 21st Century: Biomarkers, Therapies, and Prevention (2000–2024)

The early 21st century marked a transition from descriptive immunology to translational immunotherapy in the management of T1DM. By this point, the autoimmune nature of the disease was well established, but researchers shifted their focus toward early prediction, immune staging, and disease interception. This “immunological turn” was underpinned by significant advances in genetics, bioinformatics, biomarker discovery, and immune modulation strategies [

1,

32,

54].

Major efforts were directed toward defining precise immune phenotypes, discovering novel autoantibody and T-cell biomarkers predictive of disease progression [

55,

56] and developing preventive interventions targeting the presymptomatic stages of T1DM [

57,

58]. Advances in next-generation sequencing and systems immunology further accelerated the identification of molecular signatures associated with different stages of autoimmunity [

1,

59] facilitating stratified clinical trial designs and personalized immunotherapy approaches.

One of the most transformative developments was the identification of preclinical stages of T1DM based on serological and metaboilic markers. The presence of multiple islet autoantibodies such as anti-GAD, IA-2A, IAA, and ZnT8A was found to predict near-certain progression to symptomatic disease, particularly in individuals with HLA-DR3/DR4 genotypes [

33,

60]. This led to the formalization of a three-stage model: Stage 1 (autoantibodies, normoglycemia), Stage 2 (dysglycemia), and Stage 3 (clinical onset) [

32].

At the same time, genomic studies revealed more than 50 susceptibility loci beyond the HLA region, including INS, PTPN22, IL2RA, and IFIH1, helping refine risk stratification and deepening understanding of immune pathways involved in β-cell destruction [

61,

62]. This genomic insight supported the development of personalized risk scores and opened new avenues for prevention trials [

63].

On the therapeutic front, immune interventions became increasingly targeted. Anti-CD3 monoclonal antibodies such as teplizumab showed the ability to delay progression from Stage 2 to Stage 3 in high-risk individuals [

64]. In 2022, teplizumab received FDA approval the first drug ever authorized to delay the onset of T1DM, representing a watershed moment in the field (FDA, 2022). Other agents under investigation include abatacept (CTLA4-Ig), low-dose IL-2, anti-CD20 (rituximab), and combination therapies [

65].

Despite progress, major challenges remain. Not all at-risk individuals progress at the same rate, and not all therapies work equally well across age groups or immunophenotypes. Concepts like endotypes and immune resilience are being introduced to explain this variability and guide next-generation therapies [

54].

Today, T1DM is not only managed but preemptively studied. Longitudinal cohorts like TrialNet and TEDDY have redefined natural history reseach, while real-world implementation of screening and early therapy raises questions of ethics, access, and cost [

66,

67]. The 21st century has thus transformed T1DM from a fatal pediatric illness into a disease that can be monitored, anticipated, and at least in part modulated (

See the key milestones in the immunological and translational turn of type 1 diabetes, Figure 7).

Biomarker discovery, disease staging, and immunointervention have redefined T1DM from a clinically reactive condition to one that can be predicted and modulated. The progression from risk identification to FDA-approved therapies marks a new phase in autoimmune precision medicine.

8. The Contribution of Dismantled Immune Pathogenetic Concepts to the Diagnosis of T1DM: From Urine Testing to Seroimmunological and Biomolecular Analyses

The diagnosis of T1DM has undergone a profound transformation, evolving from rudimentary clinical observations to the current implementation of sophisticated immunological and genetic assays. Historically, the clinical recognition of diabetes was anchored in the detection of glycosuria, a method dating back to the 17th century when Thomas Willis described the sweet taste of diabetic urine. In the 19th century, chemical tests using Benedict’s or Fehling’s reagents enabled rudimentary quantification of glucose in urine, but lacked specificity and sensitivity. Blood glucose testing only emerged in clinical practice during the early 20th century, facilitated by the development of accurate enzymatic assays and the invention of portable glucose meters in the 1970s. Despite these advancements, T1DM remained indistinct from type 2 diabetes until the late 20th century, when immunological markers and HLA genotyping reshaped its clinical profile. The discovery of islet cell autoantibodies (ICA) in the mid-1970s represented a pivotal moment, identifying T1DM as an autoimmune disease [

16]. These antibodies were initially identified by indirect immunofluorescence techniques, revealing cytoplasmic staining patterns in pancreatic islets of deceased donors. Shortly thereafter, more specific autoantibodies were discovered, including anti-GAD65, anti-IA2, insulin autoantibodies (IAA), and later, ZnT8 autoantibodies, each providing increasing resolution for diagnosing preclinical and overt T1DM [

33,

68]. Modern diagnostic frameworks are grounded in the detection of two or more diabetes-associated autoantibodies, which predict progression to overt disease with high sensitivity and specificity [

69]. These biomarkers are now routinely employed in longitudinal birth cohort studies such as DAISY, TEDDY, and DIPP to detect islet autoimmunity in genetically predisposed children. In such contexts, the presence of multiple antibodies implies an almost certain future diagnosis of T1DM [

33]. Parallel to serological advances, HLA genotyping emerged as a cornerstone for stratifying genetic risk. The identification of the HLA-DR3/4-DQ2/8 heterozygous haplotype as a major genetic determinant helped identify neonates at greatest risk [

70]. Today, HLA typing is employed in neonatal screening programs to preselect candidates for immunological surveillance. Though HLA risk haplotypes are necessary, they are not sufficient for disease development, highlighting the need for integrated diagnostic approaches. A further revolution occurred with the ability to measure beta-cell function through the quantification of C-peptide and stimulated insulin secretion. The disappearance of C-peptide over time reflects progressive beta-cell loss and is thus used to stage disease progression and evaluate therapeutic efficacy in interventional trials [

71]. More recent developments include metabolomic profiling, such as the identification of distinct lipid signatures that precede seroconversion [

72], although these remain research tools rather than clinical standards. The evolution of T1DM diagnostics reflects a deeper understanding of its pathophysiology, from a disease of sugar metabolism to one of targeted autoimmune beta-cell destruction. Today’s diagnostic algorithms integrate autoantibody panels, genetic susceptibility markers, and dynamic beta-cell functional assays. This paradigm shift enables not only earlier diagnosis, but also opens a window for pre-symptomatic intervention, marking the dawn of a predictive and preventative era in T1DM care (

see Table 1).

Progressive evolution of diagnostic approaches for T1DM, from rudimentary symptom-based assessments and glycosuria detection in antiquity, to the molecular profiling and immunological assays used in modern clinical practice. This timeline illustrates how advances in endocrinology, immunology, and genetics have refined diagnostic accuracy and allowed for earlier and more precise detection of disease onset.

9. Conclusion

The historical reconstruction of T1DM reveals not just the evolution of a clinical entity, but the unfolding of a deeper transformation in biomedical understanding. From its earliest recognition as a polyuric wasting diesease in antiquity, through its reclassification as a metabolic disorder in the insulin era, to its current status as a prototype of organ-specific autoimmunity, T1DM went through profound ontological shifts. These shifts reflect the interplay of observation, theory, technology, and institutional resistance, hallmarks of what Thomas Kuhn would describe as scientific revolutions.

The discovery of insulin in 1921 was both a triumph and a conceptual detour. While it saved lives and revolutionized treatment, it also entrenched a metabolic interpretation of the diesease that delayed deeper inquiry into its cause. For decades, the focus on glycemic control overshadowed the heterogeneity in diesease presentation especially between children and adults which hinted at divergent underlying mechanisms. These early clinical observations were dismissed or misinterpreted in the absence of tools capable of revealing the imune system’s role in β-cell destruction.

It was only in the 1970s, with the identification of islet cell autoantibodies and the histological detection of insulitis, that a new explanatory framework emerged. The autoimune model not only redefined T1DM but placed it in a broader family of dieseases involving aberrant imune responses to self. This kind of classic shift was consolidated through the 1980s and 1990s via animal models (e.g., the NOD mouse), immunogenetic studies, and the identification of autoantigens. These advances allowed the diesease to be dissected at the molecular level and situated within the emerging field of clinical immunology.

The 21st century has ushered in a new phase translational, preventive, and personalized. Through longitudinal studies and population screening, the natural history of T1DM has been mapped from its preclinical imune stages to full-blown metabolic failure. This temporal stratification has enabled the testing and approval of immunotherapies aimed at delaying onset, with teplizumab marking a historic milestone. Yet, for all its promise, imune modulation remains complex. Variability in patient response and the need for long-term efficacy call for nuanced models of diesease progression, including emerging frameworks like endotyping.

Beyond the scientific advances, the story of T1DM is also a philosophical and institutional one. Its history illustrates how medical knowledge is not simply accumulated but restructured how dominant paradigms resist change, and how new frameworks gain traction only when evidence, instrumentation, and theory converge. The shifts in T1DM understanding mirror broader tensions in biomedicine: between reductionism and systems thinking, between symptom control and etiological insight, and between immediate clinical application and long-term conceptual clarity.

In tracing this trajectory, T1DM serves as a microcosm of biomedical evolution a case study in how dieseases are not only discovered but constructed through the very tools and lenses with which we investigate them. The journey from glycosuria to genome-wide association studies, from insulin syringes to checkpoint modulators, reflects not only progress in treatment but a deeper reconfiguration of what it means to understand a diesease.

As we look to the future, the challenge will be to sustain this integrative vision—to continue weaving together clinical, molecular, and philosophical perspectives. T1DM, once a mysterious killer of children, now stands as a sentinel diesease at the frontier of immunology, prevention, and scientific imagination.

10. Epistemological Reflections on Paradigm Shifts in T1DM

The transformation T1DM from a metabolic to an autoimmune disease offers a powerful lens through which to examine how biomedical paradigms evolve. This evolution, spanning centuries, exemplifies the dynamic interplay between empirical observation, technological innovation, and the philosophical frameworks that shape medical understanding. Thomas Kuhn’s theory of scientific revolutions is particularly instructive here. For decades, diabetes was entrenched within a metaboilic paradigm, reinforced by therapeutic success with insulin and the lack of tools to explore immune mechanisms. It was only with the accumulation of anomalies e.g., heterogeneity of clinical presentation, the discovery of islet cell autoantibodies, and evidence of insulitis that a shift became both possible and necessary. This shift was not only empirical but epistemological: it redefined what constituted valid evidence, which disciplines held authority, and how causality was framed.

The case of T1DM also underscores the role of resistance in science. Clinicians and researchers working within the metabolic framework were initially reluctant to embrace an autoimmune model. This resistance illustrates how paradigms function not only as explanatory tools but also as institutional structures that gatekeep knowledge production. The eventual adoption of the autoimmune paradigm required more than new data it required a reorganization of medical consensus.

Today, T1DM continues to evolve conceptually, as notions of disease staging, endotypes, and immune modulation introduce new layers of complexity. The history of T1DM serves as a reminder that scientific progress is rarely linear and that full-on change of lenss involve not only data, but also deep shifts in perception, trust, and disciplinary boundaries.

References

- Herold, K.C.; Delong, T.; Perdigoto, A.L.; Biru, N.; Brusko, T.M.; Walker, L.S.K. The immunology of type 1 diabetes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2024, 24, 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunn, J.F. Ancient Egyptian medicine. 1996, 240.

- Willis, T. 1621-1675. Pharmaceutice rationalis: or, The operations of medicines in humane bodies. The second part. With copper plates describing the several parts treated of in this volume. By Tho. Willis, M.D. and Sedley Professor in the University of Oxford.; 1679.

- Lancereaux Le diabète maigre : ses symptômes, son évolution, son pronostic et son traitement; ses rapports avec les altérations du pancréas. Etude comparative du diabète maigre et du diabète gras. Coup d’oeil rétrospectif sur les diabètes. Union médicale 1880, 29, 161–167.

- JV Mering, O.M. Diabetes mellitus nach Pankreasexstirpation. Zbl Klin Med 1889, 10, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joslin, E.P. The Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus; 1916.

- Vecchio, I.; Tornali, C.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Martini, M. The Discovery of Insulin: An Important Milestone in the History of Medicine. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2018, 9, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- In’t Veld, P. Insulitis in human type 1 diabetes: The quest for an elusive lesion. Islets 2011, 3, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael Bliss The Discovery of Insulin; University of Chicago Press, 1982; ISBN 9780226058986.

- Rosenfeld, L. Insulin: discovery and controversy. Clin. Chem. 2002, 48, 2270–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himsworth, H.P. DIABETES MELLITUS: ITS DIFFERENTIATION INTO INSULIN-SENSITIVE AND INSULIN-INSENSITIVE TYPES. Lancet 1936, 227, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, R.H.; Orci, L. The essential role of glucagon in the pathogenesis of diabetes mellitus. Lancet (London, England) 1975, 1, 14–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gepts, W. Pathologic anatomy of the pancreas in juvenile diabetes mellitus. Diabetes 1965, 14, 619–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witebsky, E.; Rose, N.R.; Terplan, K.; Paine, J.R.; Egan, R.W. Chronic thyroiditis and autoimmunization. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1957, 164, 1439–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irvine, W.J.; McCallum, C.J.; Gray, R.S.; Campbell, C.J.; Duncan, L.J.; Farquhar, J.W.; Vaughan, H.; Morris, P.J. Pancreatic Islet-cell Antibodies in Diabetes Mellitus Correlated with the Duration and Type of Diabetes, Coexistent Autoimmune Disease, and HLA Type. Diabetes 1977, 26, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottazzo, G.F.; Florin-Christensen, A.; Doniach, D. ISLET-CELL ANTIBODIES IN DIABETES MELLITUS WITH AUTOIMMUNE POLYENDOCRINE DEFICIENCIES. Lancet 1974, 304, 1279–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAJANS, S.S.; CONN, J.W. Tolbutamide-induced improvement in carbohydrate tolerance of young people with mild diabetes mellitus. Diabetes 1960, 9, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tattersall, R.B.; Pyke, D.A. DIABETES IN IDENTICAL TWINS. Lancet 1972, 300, 1120–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, L.M.; Parris, E.E.; Unger, R.H. Glucagon Physiology and Pathophysiology. N. Engl. J. Med. 1971, 285, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foulis, A.K. The pathology of islets in diabetes. Eye 1993, 7, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, W.J. Autoimmunity in endocrine disease. Recent Prog. Horm. Res. 1980, 36, 509–556. [Google Scholar]

- Tattersall, R.B.; Fajans, S.S. A Difference Between the Inheritance of Classical Juvenile-onset and Maturity-onset Type Diabetes of Young People. Diabetes 1975, 24, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerup, J.; Platz, P.; Andersen, O.O.; Christy, M.; Lyngs o e, J.; Poulsen, J.E.; Ryder, L.P.; Thomsen, M.; Nielsen, L.S.; Svejgaard, A. HL-A ANTIGENS AND DIABETES MELLITUS. Lancet 1974, 304, 864–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerasi, E. Mechanisms of glucose stimulated insulin secretion in health and in diabetes: Some re-evaluations and proposals - The Minkowski Award Lecture delivered on September 12, 1974, before the European Association for the Study of Diabetes at Jerusalem, Israel. Diabetologia 1975, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, M. The structure of scientific revolutions (Thomas S. Kuhn, 1970, 2nd ed. Chicago, London: University of Chicago Press Ltd. 210 pages). Philos. Pap. Rev. 2013, 4, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, M.A. Thirty Years of Investigating the Autoimmune Basis for Type 1 DiabetesWhy Can’t We Prevent or Reverse This Disease? Diabetes 2005, 54, 1253–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Notkins, A.L.; Lernmark, Å. Autoimmune type 1 diabetes: resolved and unresolved issues. J. Clin. Invest. 2001, 108, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, N.R.; Bona, C. Defining criteria for autoimmune diseases (Witebsky’s postulates revisited). Immunol. Today 1993, 14, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudworth, A.G.; Woodrow, J.C. Evidence for HL-A-linked genes in “juvenile” diabetes mellitus. Br. Med. J. 1975, 3, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, J.A.; Bell, J.I.; McDevitt, H.O. HLA-DQβ gene contributes to susceptibility and resistance to insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Nature 1987, 329, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo, M.J.; Yu, L.; Hawa, M.; Mackenzie, T.; Pyke, D.A.; Eisenbarth, G.S.; Leslie, R.D.G. Heterogeneity of Type I diabetes: Analysis of monozygotic twins in Great Britain and the United States. Diabetologia 2001, 44, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insel, R.A.; Dunne, J.L.; Atkinson, M.A.; Chiang, J.L.; Dabelea, D.; Gottlieb, P.A.; Greenbaum, C.J.; Herold, K.C.; Krischer, J.P.; Lernmark, A.; et al. Staging presymptomatic type 1 diabetes: A scientific statement of jdrf, the endocrine society, and the American diabetes association. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 1964–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, A.G.; Rewers, M.; Simell, O.; Simell, T.; Lempainen, J.; Steck, A.; Winkler, C.; Ilonen, J.; Veijola, R.; Knip, M.; et al. Seroconversion to multiple islet autoantibodies and risk of progression to diabetes in children. JAMA 2013, 309, 2473–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, C.A.; Libman, I.M.; Becker, D.J.; Levitsky, L.L. From Antiquity to Modern Times: A History of Diabetes Mellitus and Its Treatments. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2022, 95, 593–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makino, S.; Kunimoto, K.; Muraoka, Y.; Mizushima, Y.; Katagiri, K.; Tochino, Y. Breeding of a non-obese, diabetic strain of mice. Exp. Anim. 1980, 29, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikutani, H.; Makino, S. The murine autoimmune diabetes model: NOD and related strains. Adv. Immunol. 1992, 51, 285–322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jansen, A.; Homo-Delarche, F.; Hooijkaas, H.; Leenen, P.J.; Dardenne, M.; Drexhage, H.A. Immunohistochemical characterization of monocytes-macrophages and dendritic cells involved in the initiation of the insulitis and beta-cell destruction in NOD mice. Diabetes 1994, 43, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.S.; Bluestone, J.A. The NOD mouse: A model of immune dysregulation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2005, 23, 447–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulis, A.K.; Liddle, C.N.; Farquharson, M.A.; Richmond, J.A.; Weir, R.S. The histopathology of the pancreas in Type I (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus: a 25-year review of deaths in patients under 20 years of age in the United Kingdom. Diabetologia 1986, 29, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willcox, A.; Richardson, S.J.; Bone, A.J.; Foulis, A.K.; Morgan, N.G. Analysis of islet inflammation in human type 1 diabetes. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2009, 155, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, M.A.; Eisenbarth, G.S. Type 1 diabetes: New perspectives on disease pathogenesis and treatment. Lancet 2001, 358, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, M. Insulin as a key autoantigen in the development of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. Metab. Res. Rev. 2011, 27, 773–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifacio, E.; Genovese, S.; Braghi, S.; Bazzigaluppi, E.; Lampasona, Y.; Bingley, P.J.; Rogge, L.; Pastore, M.R.; Bognetti, E.; Bottazzo, G.F.; et al. Islet autoantibody markers in IDDM: risk assessment strategies yielding high sensitivity. Diabetologia 1995, 38, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krischer, J.P.; Liu, X.; Lernmark, Å.; Hagopian, W.A.; Rewers, M.J.; She, J.X.; Toppari, J.; Ziegler, A.G.; Akolkar, B. The influence of type 1 diabetes genetic susceptibility regions, age, sex, and family history on the progression from multiple autoantibodies to type 1 diabetes: A teddy study report. Diabetes 2017, 66, 3122–3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todd, J.A. Genetic control of autoimmunity in type 1 diabetes. Immunol. Today 1990, 11, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noble, J.A.; Erlich, H.A. Genetics of type 1 diabetes. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilonen, J.; Lempainen, J.; Veijola, R. The heterogeneous pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougneres, P.F.; Carel, J.C.; Castano, L.; Boitard, C.; Gardin, J.P.; Landais, P.; Hors, J.; Mihatsch, M.J.; Paillard, M.; Chaussain, J.L.; et al. Factors Associated with Early Remission of Type I Diabetes in Children Treated with Cyclosporine. N. Engl. J. Med. 1988, 318, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatenoud, L.; Thervet, E.; Primo, J.; Bach, J.F. Anti-CD3 antibody induces long-term remission of overt autoimmunity in nonobese diabetic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994, 91, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Group, T.D.C. and C. T.R. The Effect of Intensive Treatment of Diabetes on the Development and Progression of Long-Term Complications in Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993, 329, 977–986. [Google Scholar]

- Skyler, J.S. Effects of oral insulin in relatives of patients with type 1 diabetes: The diabetes prevention trial-type 1. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 1068–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Assfalg, R.; Knoop, J.; Hoffman, K.L.; Pfirrmann, M.; Zapardiel-Gonzalo, J.M.; Hofelich, A.; Eugster, A.; Weigelt, M.; Matzke, C.; Reinhardt, J.; et al. Oral insulin immunotherapy in children at risk for type 1 diabetes in a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia 2021, 64, 1079–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, E.K.; Carr, A.L.J.; Oram, R.A.; DiMeglio, L.A.; Evans-Molina, C. 100 years of insulin: celebrating the past, present and future of diabetes therapy. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1154–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, M.; Anderson, M.S.; Buckner, J.H.; Geyer, S.M.; Gottlieb, P.A.; Kay, T.W.H.; Lernmark, Å.; Muller, S.; Pugliese, A.; Roep, B.O.; et al. Understanding and preventing type 1 diabetes through the unique working model of TrialNet. Diabetologia 2017, 60, 2139–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vehik, K.; Bonifacio, E.; Lernmark, Å.; Yu, L.; Williams, A.; Schatz, D.; Rewers, M.; She, J.X.; Toppari, J.; Hagopian, W.; et al. Hierarchical order of distinct autoantibody spreading and progression to type 1 diabetes in the Teddy study. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 2066–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sims, E.K.; Besser, R.E.J.; Dayan, C.; Rasmussen, C.G.; Greenbaum, C.; Griffin, K.J.; Hagopian, W.; Knip, M.; Long, A.E.; Martin, F.; et al. Screening for Type 1 Diabetes in the General Population: A Status Report and Perspective. Diabetes 2022, 71, 610–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, A.G.; Schmid, S.; Huber, D.; Hummel, M.; Bonifacio, E. Early Infant Feeding and Risk of Developing Type 1 Diabetes–Associated Autoantibodies. JAMA 2003, 290, 1721–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenbaum, C.J. A Key to T1D Prevention: Screening and Monitoring Relatives as Part of Clinical Care. Diabetes 2021, 70, 1029–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pociot, F. Type 1 diabetes genome-wide association studies: Not to be lost in translation. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifacio, E.; Beyerlein, A.; Hippich, M.; Winkler, C.; Vehik, K.; Weedon, M.N.; Laimighofer, M.; Hattersley, A.T.; Krumsiek, J.; Frohnert, B.I.; et al. Genetic scores to stratify risk of developing multiple islet autoantibodies and type 1 diabetes: A prospective study in children. PLoS Med. 2018, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankovic, J.; Sherer, T. The future of research in Parkinson disease. JAMA Neurol. 2014, 71, 1351–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klak, M.; Gomółka, M.; Kowalska, P.; Cichoń, J.; Ambrożkiewicz, F.; Serwańska-Świętek, M.; Berman, A.; Wszoła, M. Type 1 diabetes: genes associated with disease development. Cent. Eur. J. of Immunology 2021, 45, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo, M.J.; Steck, A.K.; Pugliese, A. Genetics of type 1 diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 2018, 19, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herold, K.C.; Bundy, B.N.; Long, S.A.; Bluestone, J.A.; DiMeglio, L.A.; Dufort, M.J.; Gitelman, S.E.; Gottlieb, P.A.; Krischer, J.P.; Linsley, P.S.; et al. An Anti-CD3 Antibody, Teplizumab, in Relatives at Risk for Type 1 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orban, T.; Bundy, B.; Becker, D.J.; DiMeglio, L.A.; Gitelman, S.E.; Goland, R.; Gottlieb, P.A.; Greenbaum, C.J.; Marks, J.B.; Monzavi, R.; et al. Co-stimulation modulation with abatacept in patients with recent-onset type 1 diabetes: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2011, 378, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rewers, M.; Ludvigsson, J. Environmental risk factors for type 1 diabetes. Lancet 2016, 387, 2340–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achenbach, P.; Hummel, M.; Thümer, L.; Boerschmann, H.; Höfelmann, D.; Ziegler, A.G. Characteristics of rapid vs slow progression to type 1 diabetes in multiple islet autoantibody-positive children. Diabetologia 2013, 56, 1615–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzlau, J.M.; Juhl, K.; Yu, L.; Moua, O.; Sarkar, S.A.; Gottlieb, P.; Rewers, M.; Eisenbarth, G.S.; Jensen, J.; Davidson, H.W.; et al. The cation efflux transporter ZnT8 (Slc30A8) is a major autoantigen in human type 1 diabetes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104, 17040–17045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingley, P.J. Clinical applications of diabetes antibody testing. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 95, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rewers, M.; Bugawan, T.L.; Norris, J.M.; Blair, A.; Beaty, B.; Hoffman, M.; McDuffie, R.S.; Hamman, R.F.; Klingensmith, G.; Eisenbarth, G.S.; et al. Newborn screening for HLA markers associated with IDDM: Diabetes autoimmunity study in the young (DAISY). Diabetologia 1996, 39, 807–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenbaum, C.J.; Beam, C.A.; Boulware, D.; Gitelman, S.E.; Gottlieb, P.A.; Herold, K.C.; Lachin, J.M.; McGee, P.; Palmer, J.P.; Pescovitz, M.D.; et al. Fall in C-peptide during first 2 years from diagnosis: Evidence of at least two distinct phases from composite type 1 diabetes trialnet data. Diabetes 2012, 61, 2066–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orešič, M.; Simell, S.; Sysi-Aho, M.; Näntö-Salonen, K.; Seppänen-Laakso, T.; Parikka, V.; Katajamaa, M.; Hekkala, A.; Mattila, I.; Keskinen, P.; et al. Dysregulation of lipid and amino acid metabolism precedes islet autoimmunity in children who later progress to type 1 diabetes. J. Exp. Med. 2008, 205, 2975–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).