Submitted:

29 May 2025

Posted:

29 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

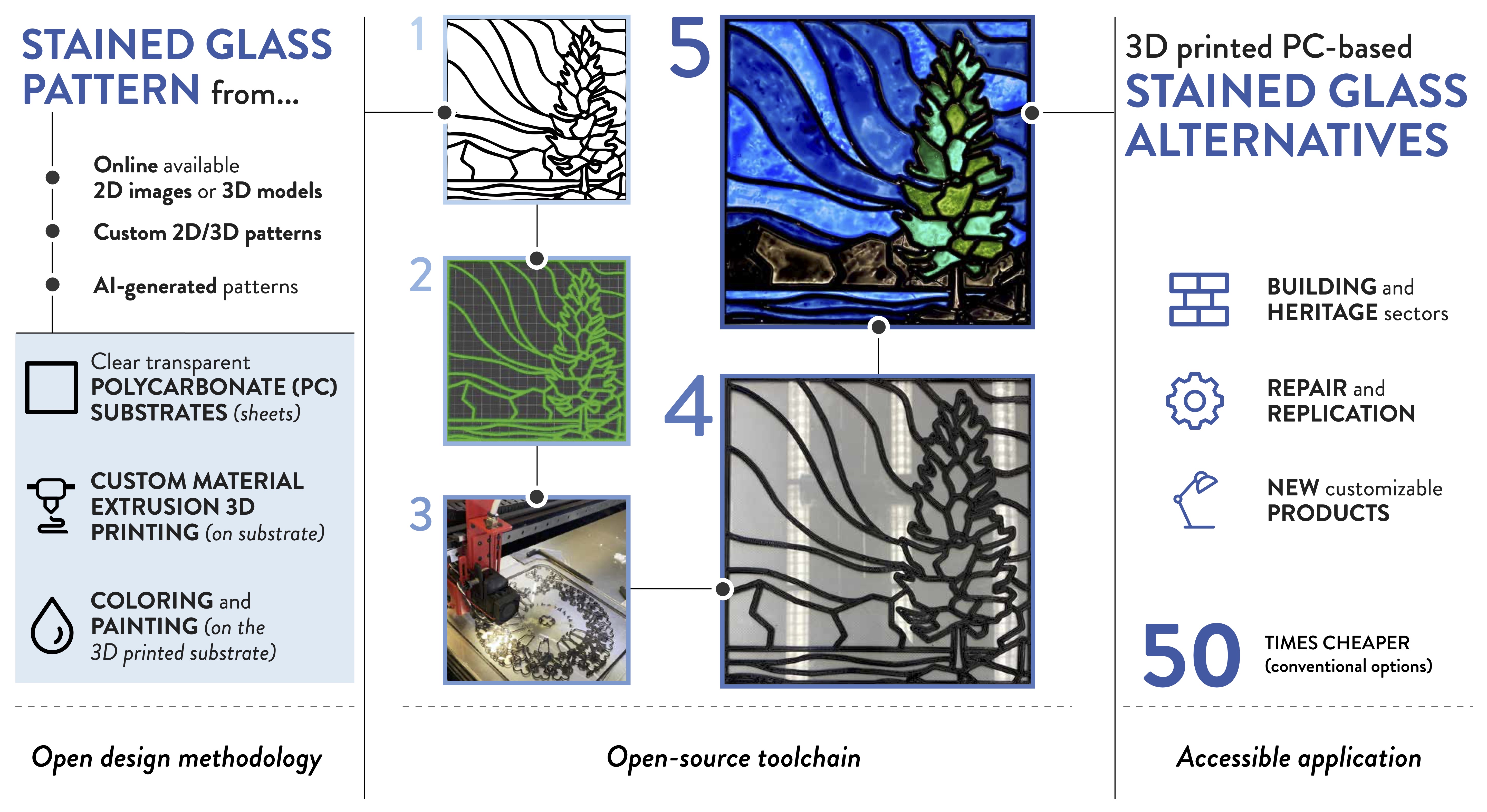

1. Introduction

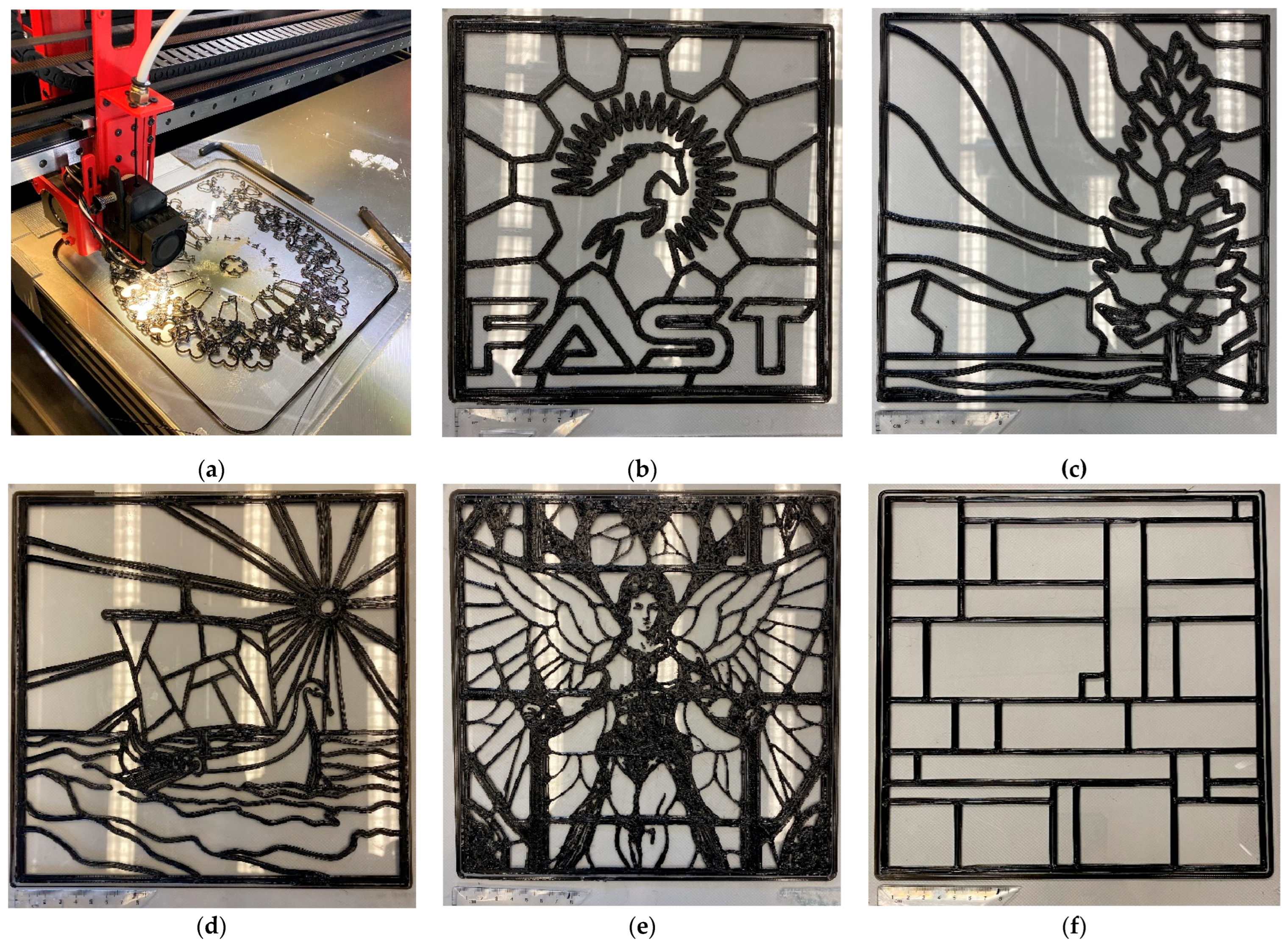

2. Materials and Methods

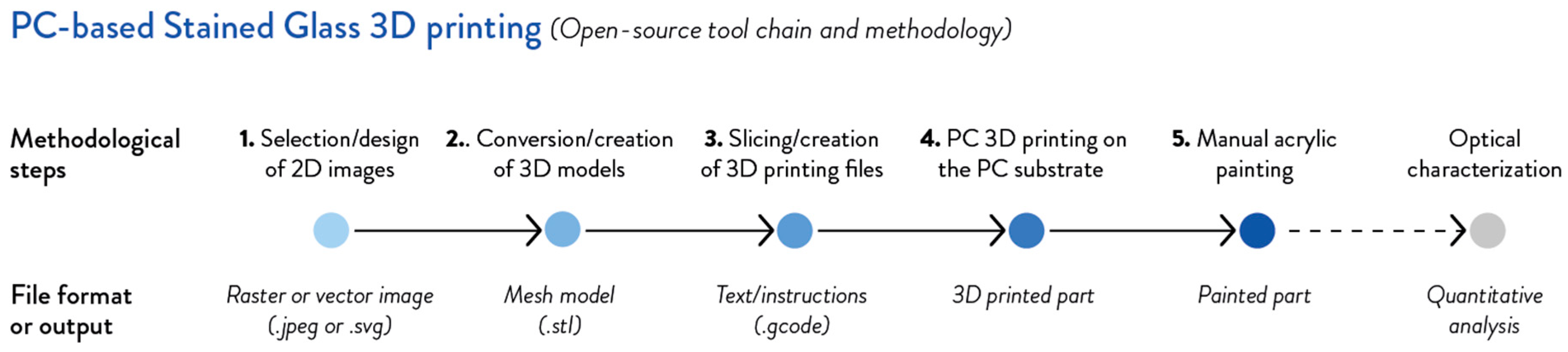

- Selection or design of the 2D images for the final stained-glass designs, e.g., sketches, drawings, raster, or vector images (Subsection 2.1, Figure 2).

- Conversion of the 2D images and creation of the 3D models saved in mesh format, i.e., STL (Subsection 2.2).

- Slicing of the 3D mesh models and generation of the gcode files (Subsection 2.2, Figure 3).

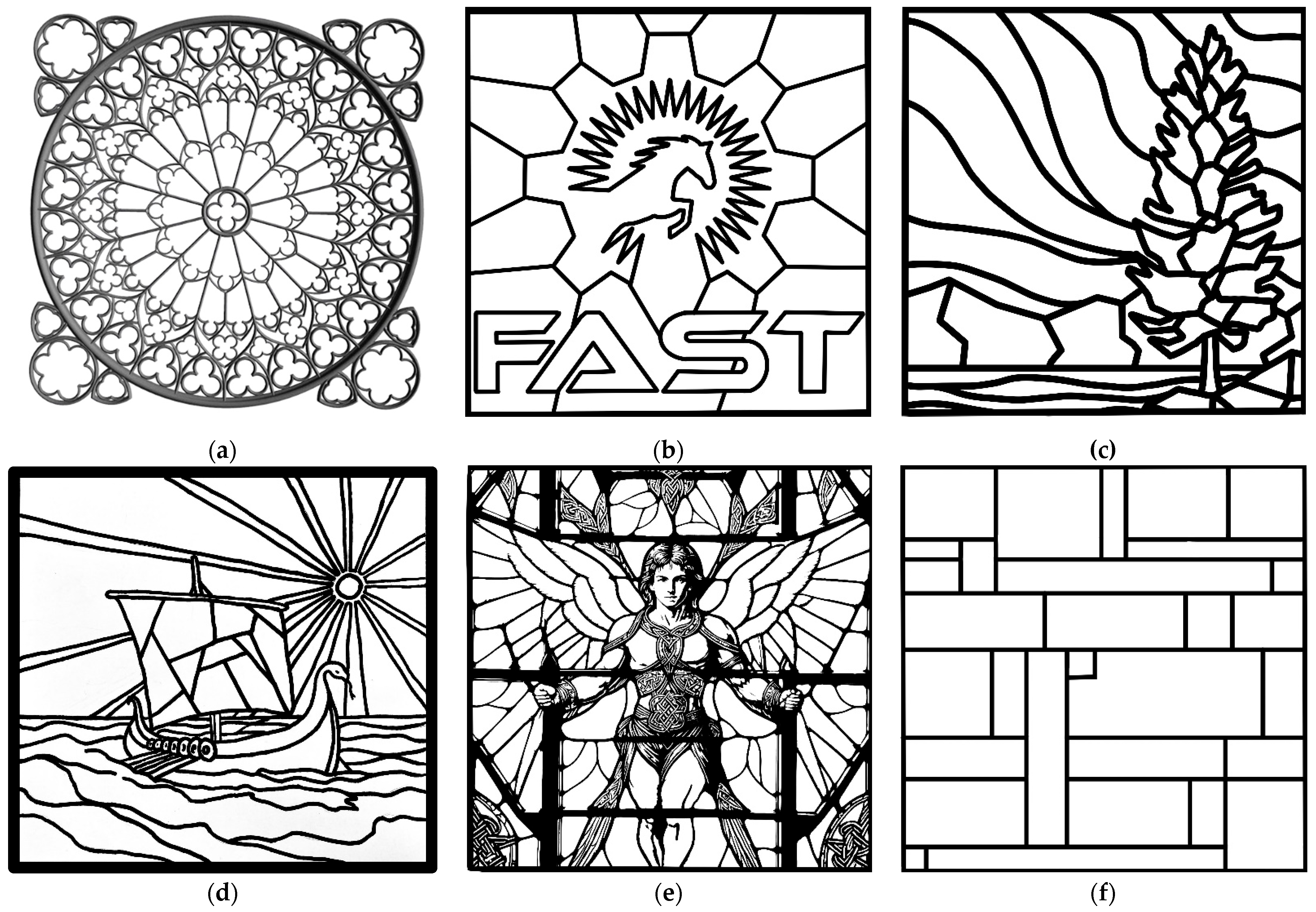

- Fabrication of the PC-based 3D design on the PC substrate via FFF 3D printing (Subsection 2.3, Figure 4).

- Manual coloring of the 3D-printed PC inserts through acrylic painting techniques (Subsection 2.3, Figures 7–10).

2.1. Phase 1: 2D Image Selection and Design

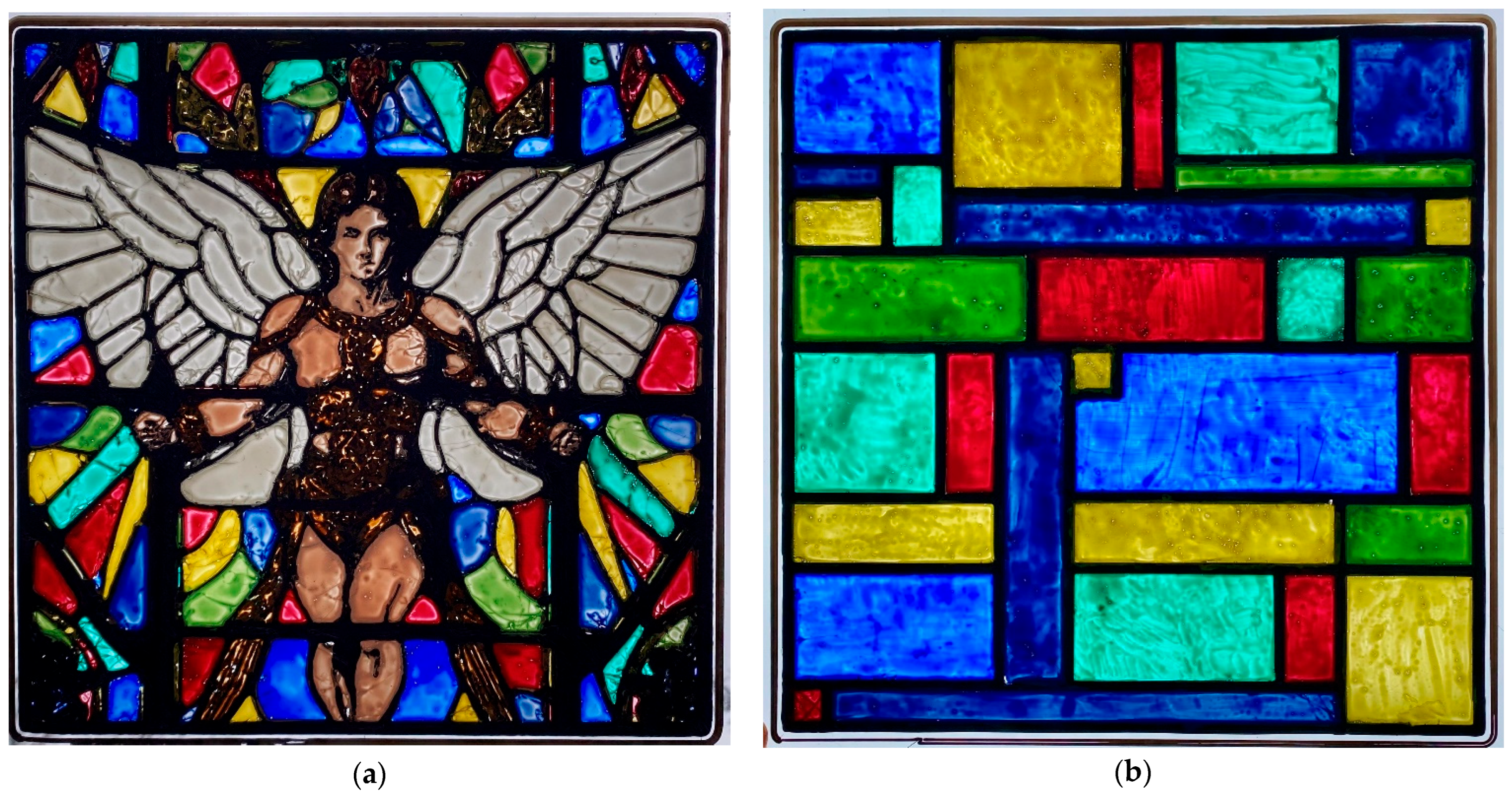

- AI-generated designs: novel custom design from an AI image generator (Angel, Figure 2e), saved as raster image and converted into vector.

2.1.1. Online-Retrieved Designs

2.1.2. Custom Designs: Digital-Drawn and Hand-Drawn Images

2.1.3. AI-Generated Design

2.1.4. Geometric Validation Image

2.2. Phases 2 and 3: Creation of the 3D Mesh Models and 3D Printing Slicing

2.3. Phases 4 and 5: FFF Additive Manufacturing and Painting

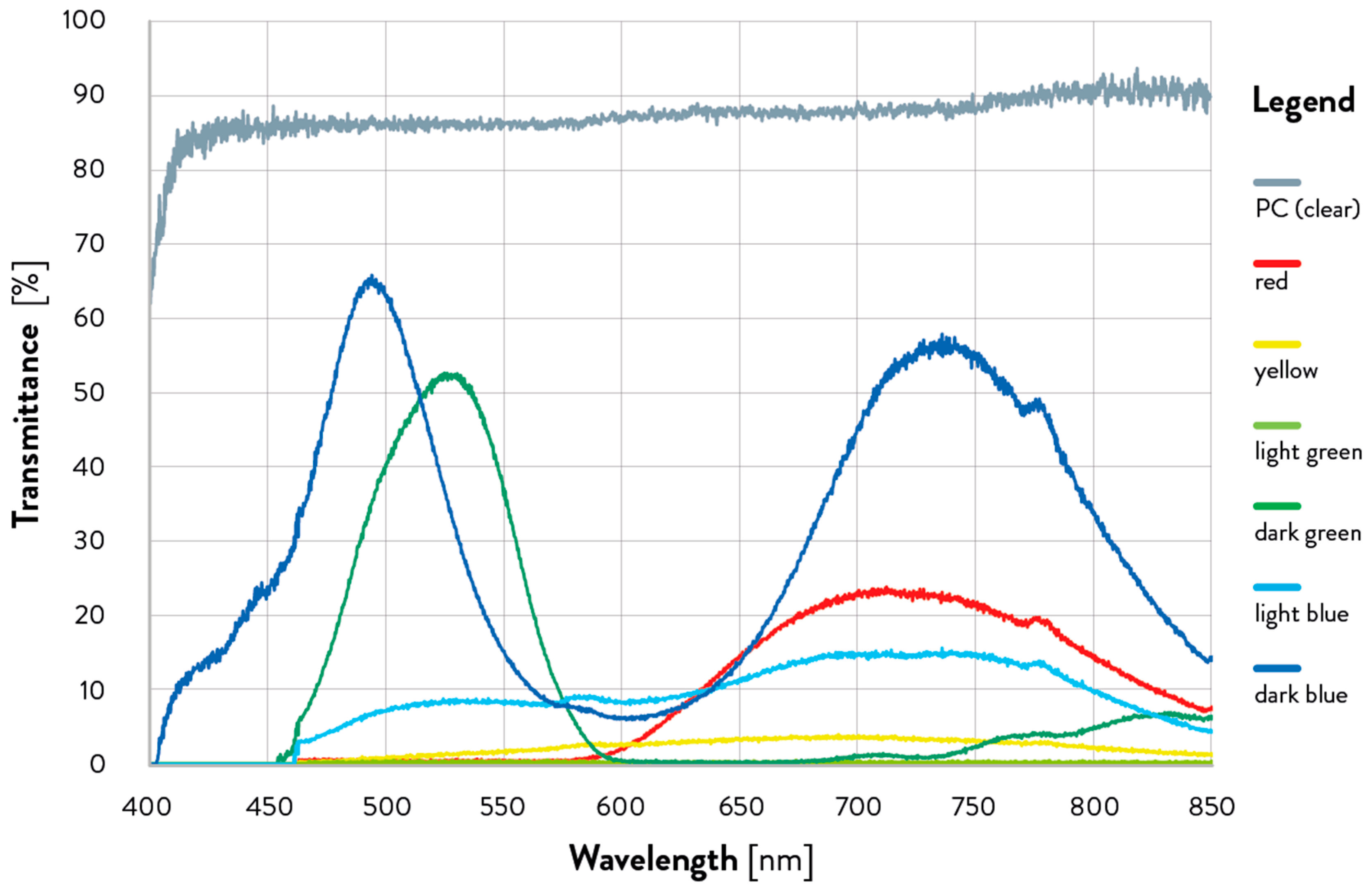

2.4. Optical Spectrum Characterization and Transmission Calculation

2.5. Preliminary Economic Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. FFF Additive Manufacturing of the Sample Designs

3.2. Aesthetic Production of Designs

3.2.1. Online-Retrieved Designs

3.2.2. Custom Designs: Digital-Drawn and Hand-Drawn Images

3.2.3. AI-Generated Design and Geometric Validation Image

3.3. Optical Transmission Validation

3.4. Economic Analysis

3.5. Potential of 3D Printed Stained Glass Alternatives Fabricated Through Open-Source Approaches

3.6. Limitations and Future Work

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rosewell, R. Stained Glass; Bloomsbury Publishing, 2012; ISBN 978-1-78200-150-8.

- Hunault, M.O.J.Y.; Bauchau, F.; Boulanger, K.; Hérold, M.; Calas, G.; Lemasson, Q.; Pichon, L.; Pacheco, C.; Loisel, C. Thirteenth-Century Stained Glass Windows of the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris: An Insight into Medieval Glazing Work Practices. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 2021, 35, 102753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varieties of Stained Glass. Available online: https://stainedglass.org/learning-resources/varieties-stained-glass (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Parker, J.M.; Martlew, D. Stained Glass Windows. In Encyclopedia of Glass Science, Technology, History, and Culture; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2021; pp. 1341–1359 ISBN 978-1-118-80101-7.

- Finucane, M.A.; Black, I. CO2 Laser Cutting of Stained Glass. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 1996, 12, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehren, Th.; Freestone, I.C. Ancient Glass: From Kaleidoscope to Crystal Ball. Journal of Archaeological Science 2015, 56, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, D. Design in Stained Glass. Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review 1952, 41, 209–218. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, M.; Bonet, J.; Cotte, M.; Schibille, N.; Gratuze, B.; Pradell, T. The Role of Sulphur in the Early Production of Copper Red Stained Glass. Ceramics International 2023, 49, 18602–18613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradell, T.; Molina, G.; Murcia, S.; Ibáñez, R.; Liu, C.; Molera, J.; Shortland, A.J. Materials, Techniques, and Conservation of Historic Stained Glass “Grisailles. ” International Journal of Applied Glass Science 2016, 7, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verney-Carron, A.; Sessegolo, L.; Chabas, A.; Lombardo, T.; Rossano, S.; Perez, A.; Valbi, V.; Boutillez, C.; Muller, C.; Vaulot, C.; et al. Alteration of Medieval Stained Glass Windows in Atmospheric Medium: Review and Simplified Alteration Model. npj Mater Degrad 2023, 7, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilarigues, M.; Redol, P.; Machado, A.; Rodrigues, P.A.; Alves, L.C.; da Silva, R.C. Corrosion of 15th and Early 16th Century Stained Glass from the Monastery of Batalha Studied with External Ion Beam. Materials Characterization 2011, 62, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa Pinto, A.M.; Macedo, M.F.; Vilarigues, M.G. The Conservation of Stained-Glass Windows in Latin America: A Literature Overview. Journal of Cultural Heritage 2018, 34, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murcia-Mascarós, S.; Foglia, P.; Santarelli, M.L.; Roldán, C.; Ibañez, R.; Muñoz, A.; Muñoz, P. A New Cleaning Method for Historic Stained Glass Windows. Journal of Cultural Heritage 2008, 9, e73–e80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon-King, D.; Jones, L.; Nabil, S. Interactive Stained-Glass: Exploring a New Design Space of Traditional Hybrid Crafts for Novel Fabrication Methods. In Proceedings of the Seventeenth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 26 February 2023; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Cuce, E.; Riffat, S.B. A State-of-the-Art Review on Innovative Glazing Technologies. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2015, 41, 695–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somasundaram, S.; Thangavelu, S.R.; Chong, A. Improving Building Efficiency Using Low-e Coating Based Retrofit Double Glazing with Solar Films. Applied Thermal Engineering 2020, 171, 115064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, S.; Trümpler, S.; Wakili, K.G.; Binder, B.; Baumann, E. Protective Glazing: The Conflict Between Energy- Saving and Conservation Requirements.

- Uher, C. Thermal Conductivity of Metals. In Thermal Conductivity: Theory, Properties, and Applications; Tritt, T.M., Ed.; Physics of Solids and Liquids; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 21–91. ISBN 978-0-387-26017-4. [Google Scholar]

- Lidelöw, S.; Örn, T.; Luciani, A.; Rizzo, A. Energy-Efficiency Measures for Heritage Buildings: A Literature Review. Sustainable Cities and Society 2019, 45, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Learn How Much It Costs to Install Stained Glass. Available online: https://www.homeadvisor.com/cost/home-design-and-decor/install-stained-glass/ (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- How Much Does It Cost to Install a Stained Glass Window in 2023? Available online: https://www.angi.com/articles/how-much-cost-stained-glass-window.htm (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Stained Glass Repair Cost: Can Stained Glass Be Repaired and How Much Does It Cost? - Kompareit.Com. Available online: https://www.kompareit.com/homeandgarden/windows-can-stained-glass-be-repaired.html#:~:text=How%20Much%20Does%20Stained%20Glass%20Repair%20Cost%3F%201,panel%2C%20depending%20on%20size%20and%20condition.%20More%20items (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Frenzel, G. The Restoration of Medieval Stained Glass. Scientific American 1985, 252, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qurraie, B.S.; Beyhan, F. Investigating the Effect of Stained-Glass Area on Reducing the Cooling Energy of Buildings (Case Study: Ankara). CRPASE 2022, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, S.; Maduru, V.R.; Kirankumar, G.; Arıcı, M.; Ghosh, A.; Kontoleon, K.J.; Afzal, A. Space-Age Energy Saving, Carbon Emission Mitigation and Color Rendering Perspective of Architectural Antique Stained Glass Windows. Energy 2022, 259, 124898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, E.; Zinzi, M.; Belloni, E. Polycarbonate Panels for Buildings: Experimental Investigation of Thermal and Optical Performance. Energy and Buildings 2014, 70, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittbrodt, B.T.; Glover, A.G.; Laureto, J.; Anzalone, G.C.; Oppliger, D.; Irwin, J.L.; Pearce, J.M. Life-Cycle Economic Analysis of Distributed Manufacturing with Open-Source 3-D Printers. Mechatronics 2013, 23, 713–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attaran, M. The Rise of 3-D Printing: The Advantages of Additive Manufacturing over Traditional Manufacturing. Business Horizons 2017, 60, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romani, A.; Rognoli, V.; Levi, M. Design, Materials, and Extrusion-Based Additive Manufacturing in Circular Economy Contexts: From Waste to New Products. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obi, M.U.; Pradel, P.; Sinclair, M.; Bibb, R. A Bibliometric Analysis of Research in Design for Additive Manufacturing. Rapid Prototyping J. 2022, 28, 967–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boisseau, É.; Omhover, J.-F.; Bouchard, C. Open-Design: A State of the Art Review. Des. Sci. 2018, 4, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sells, E.; Bailard, S.; Smith, Z.; Bowyer, A.; Olliver, V. RepRap: The Replicating Rapid Prototyper: Maximizing Customizability by Breeding the Means of Production. In Handbook of Research in Mass Customization and Personalization; World Scientific Publishing Company, 2009; pp. 568–580 ISBN 978-981-4280-25-9.

- Jones, R.; Haufe, P.; Sells, E.; Iravani, P.; Olliver, V.; Palmer, C.; Bowyer, A. RepRap – the Replicating Rapid Prototyper. Robotica 2011, 29, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, E.E.; Pearce, J. Emergence of Home Manufacturing in the Developed World: Return on Investment for Open-Source 3-D Printers. Technologies 2017, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.; Qian, J.-Y. Economic Impact of DIY Home Manufacturing of Consumer Products with Low-Cost 3D Printing from Free and Open Source Designs. European Journal of Social Impact and Circular Economy 2022, 3, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar, A.; Belhabib, S.; Guessasma, S.; Benmahiddine, F.; Hamami, A.E.A.; Belarbi, R. Mechanical and Thermal Properties of 3D Printed Polycarbonate. Energies 2022, 15, 3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidakis, N.; Petousis, M.; Kechagias, J.D. A Comprehensive Investigation of the 3D Printing Parameters’ Effects on the Mechanical Response of Polycarbonate in Fused Filament Fabrication. Prog Addit Manuf 2022, 7, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidakis, N.; Petousis, M.; Velidakis, E.; Spiridaki, M.; Kechagias, J.D. Mechanical Performance of Fused Filament Fabricated and 3D-Printed Polycarbonate Polymer and Polycarbonate/Cellulose Nanofiber Nanocomposites. Fibers 2021, 9, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romani, A.; Levi, M.; Pearce, J.M. Recycled Polycarbonate and Polycarbonate/Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene Feedstocks for Circular Economy Product Applications with Fused Granular Fabrication-Based Additive Manufacturing. Sustainable Materials and Technologies 2023, 38, e00730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, M.J.; Woern, A.L.; Tanikella, N.G.; Pearce, J.M. Mechanical Properties and Applications of Recycled Polycarbonate Particle Material Extrusion-Based Additive Manufacturing. Materials 2019, 12, 1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; He, S.; Lu, L. Binary Image Carving for 3D Printing. Computer-Aided Design 2019, 114, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, W.; Guo, J.; Cao, J.; Zhang, Y.J. Orientation Field Guided Line Abstraction for 3D Printing. Computer Aided Geometric Design 2018, 62, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedel, A.; Coudert-Osmont, Y.; Martínez, J.; Nishat, R.I.; Whitesides, S.; Lefebvre, S. Closed Space-Filling Curves with Controlled Orientation for 3D Printing. Computer Graphics Forum 2022, 41, 473–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, A. Democratizing Production through Open Source Knowledge: From Open Software to Open Hardware. Media, Culture & Society 2012, 34, 691–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, A. Building Open Source Hardware: DIY Manufacturing for Hackers and Makers; Addison-Wesley Professional, 2014; ISBN 978-0-13-337390-5.

- Bow Pearce, E.; Pearce, J.; Romani, A. 3D Printable Designs for Alternatives to Stained Glass for Energy Efficiency and Economic Savings. 2025.

- NOTRE DAME | 3D CAD Model Library | GrabCAD. Available online: https://grabcad.com/library/notre-dame-4 (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- File:FASTlogobw.Png. Available online: https://www.appropedia.org/File:FASTlogobw.png (accessed on 25 November 2023).

- GIMP. Available online: https://www.gimp.org/ (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Developers, I.W. Inkscape - Draw Freely. | Inkscape. Available online: https://inkscape.org/ (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Foundation, K. Krita. Available online: https://krita.org/en/ (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- AUTOMATIC1111 Stable Diffusion Web UI. Available online: https://github.com/AUTOMATIC1111/stable-diffusion-webui (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- ImageJ. Available online: https://imagej.net/ij/ (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- PrusaSlicer | Original Prusa 3D Printers Directly from Josef Prusa. Available online: https://www.prusa3d.com/page/prusaslicer_424/ (accessed on 21 July 2023).

- BIG-Meter – Modix Large 3D Printers. Available online: https://www.modix3d.com/big-meter/ (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Operating Manual for Modix Printers. Available online: https://www.appropedia.org/Operating_Manual_for_Modix_printers (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Black PC Filament 1.75 Mm 3D Printer Filament 1 KG Spool 2.2LBS Dimensional Accuracy +/- 0.05mm 3D Printing Polycarbonate Material: Amazon.ca: Industrial & Scientific. Available online: https://www.amazon.ca/Filament-Dimensional-Accuracy-Printing-Polycarbonate/dp/B075SXS6NP/ref=sr_1_5?keywords=polycarbonate+filament+1.75&sr=8-5 (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- 20 Pack 12 x 12 x.02 Inch Clear Plastic Craft Polycarbonate Sheet Thin Clear Plastic Sheet Flexible Transparent Plastic Sheet for Crafts DIY Projects Document Picture Frames Replacement Window Panes: Amazon.ca: Home. Available online: https://www.amazon.ca/Polycarbonate-Flexible-Transparent-Projects-Replacement/dp/B09XZZG8SH (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Software. Ocean Optics.

- Wittbrodt, B.T.; Glover, A.G.; Laureto, J.; Anzalone, G.C.; Oppliger, D.; Irwin, J.L.; Pearce, J.M. Life-Cycle Economic Analysis of Distributed Manufacturing Withopen-Source 3-D Printers. Mechatronics 2013, 23, 713–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BIG-Meter – Modix Large 3D Printers. Available online: https://www.modix3d.com/big-meter/ (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Electricity Rates | Ontario Energy Board. Available online: https://www.oeb.ca/consumer-information-and-protection/electricity-rates (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- [Hot Item] Transparent 3mm 4mm 5mm 8mm Solid Polycarbonate Sheets for Greenhouse. Available online: https://yunai888.en.made-in-china.com/product/uwCtIAPjrzWd/China-Transparent-3mm-4mm-5mm-8mm-Solid-Polycarbonate-Sheets-for-Greenhouse.html (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Costanzo, V.; Nocera, F.; Evola, G.; Buratti, C.; Lo Faro, A.; Marletta, L.; Domenighini, P. Optical Characterization of Historical Coloured Stained Glasses in Winter Gardens and Their Modelling in Daylight Availability Simulations. Solar Energy 2022, 243, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbadawi, M.; Basit, A.W.; Gaisford, S. Energy Consumption and Carbon Footprint of 3D Printing in Pharmaceutical Manufacture. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2023, 639, 122926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- [Hot Item] Tempered Double Pane Glazing Glass Price. Available online: https://jinjingglass.en.made-in-china.com/product/WdqAnZKyLBRG/China-Tempered-Double-Pane-Glazing-Glass-Price.html (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Balletti, C.; Ballarin, M.; Guerra, F. 3D Printing: State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Journal of Cultural Heritage 2017, 26, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeois, I.; Ascensão, Guilherme; Ferreira, Victor; and Rodrigues, H. Methodology for the Application of 3D Technologies for the Conservation and Recovery of Built Heritage Elements. International Journal of Architectural Heritage 2024, 0, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Espinel, J.D.; González, J.M.L.-G.; Torres, M.F. 3D Heritage: Preserving Historical and Cultural Heritage Through Reality Capture and Large-Scale 3D Printing. In Decoding Cultural Heritage: A Critical Dissection and Taxonomy of Human Creativity through Digital Tools; Moral-Andrés, F., Merino-Gómez, E., Reviriego, P., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 377–394. ISBN 978-3-031-57675-1. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J. The Application of 3D Printing Technology in Sculpture. In Proceedings of the The 2020 International Conference on Machine Learning and Big Data Analytics for IoT Security and Privacy; MacIntyre, J., Zhao, J., Ma, X., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 755–759. [Google Scholar]

- KurtH3 How to 3D Print a Stained “Glass” Window. Available online: https://www.instructables.com/How-to-3D-Print-a-Stained-Glass-Window/ (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- By Faux Stained Glass Effect, With 3D Printing And Epoxy. Hackaday 2021.

- cp_admin Toronto Based 3D Printing Service Company Creates a Stained Glass Window out of 100% Plastic. Available online: https://customprototypes.ca/blog/toronto-based-3d-printing-service-company-creates-a-stained-glass-window-out-of-10089991592657516849e6744e94e5940d3ea60f047fd6ba2f5bb1206c368e04806-plastic/ (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Zhong, S.; Pearce, J.M. Tightening the Loop on the Circular Economy: Coupled Distributed Recycling and Manufacturing with Recyclebot and RepRap 3-D Printing. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2018, 128, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romani, A.; Levi, M. Large-Format Material Extrusion Additive Manufacturing for Circular Economy Practices: A Focus on Product Applications with Materials from Recycled Plastics and Biomass Waste. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thingiverse.com Stained Glass Orchid by Carbonbased. Available online: https://www.thingiverse.com/thing:3080869 (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Woern, A.L.; McCaslin, J.R.; Pringle, A.M.; Pearce, J.M. RepRapable Recyclebot: Open Source 3-D Printable Extruder for Converting Plastic to 3-D Printing Filament. HardwareX 2018, 4, e00026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Home of HueForge. Available online: https://shop.thehueforge.com/ (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Brooks, S. Image-Based Stained Glass. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics 2006, 12, 1547–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stained Glass Window Generator. Available online: https://deepai.org/machine-learning-model/stained-glass-generator (accessed on 28 May 2025).

|

Sample and nomenclature |

Design Category |

2D design (origin) |

Image format |

3D model format |

3D printing format |

| Online Notre Dame Rose Window [47] - SG01 | Online designs (Section 2.1.1) | Retrieved design (3D model, online) | SVG (vector) |

STL (mesh) |

gcode |

| Online FAST Logo [48] - SG02 | Online designs (Section 2.1.1) | Retrieved design (2D image, online) | SVG (vector) |

STL (mesh) |

gcode |

| Digital Created Northern Lights- SG03 | Custom designs (Section 2.1.2) | Digital drawing | SVG (vector) |

STL (mesh) |

gcode |

| Viking Boat - SG04 | Custom designs (Section 2.1.2) | Paper drawing (digital acquisition) | JPEG (raster) |

STL (mesh) |

gcode |

| AI created Angel - SG05 | AI-generated designs (Section 2.1.3) | AI-generated image |

JPEG (raster) |

STL (mesh) |

gcode |

| Digital Created Geometric - SG06 | Geometric validation (Section 2.1.4) | Digital Image | SVG (vector) |

STL (mesh) |

gcode |

| Parameters for Bitmap Creation | Value |

| Detection Mode | Autotrace |

| Filter Iterations | 4 |

| Error Threshold | 2.0 |

| Speckles | 1000 |

| Smooth Corners | 1.000 |

| Optimize | 0.000 |

| 3D Printing Parameter | Unit | Value |

| Nozzle Diameter | mm | 0.8 |

| 3D printing temperature | °C | 245 |

| Build Plate Temperature | °C | 105 |

| 3D Printing Speed | mm/s | 60 |

| 3D Printing Speed (initial layer) | mm/s | 30 |

| Extrusion Flow | % | 100 |

| Number of Perimeters | // | 3 |

| Layer Height | mm | 0.8 |

| Layer Height (Initial layer) | mm | 0.5 |

| Number of bottom/top layers | // | 3 |

| Infill percentage | % | 100 |

| N. Color | Color | Transmission (%) |

Area in the Geometric Validation Design (mm2) |

| 1 | Red | 7.5 | 226.9 |

| 2 | Yellow | 1.7 | 396.4 |

| 3 | Light Green | 0.1 | 219.2 |

| 4 | Dark Green | 7.6 | 354.7 |

| 5 | Light Blue | 6.9 | 364.3 |

| 6 | Dark blue | 21.3 | 413.6 |

| Sample | 3D printed path | PC substrate | Total cost (US$) | |||

| Nominal weight (g) | Nominal time (min) | Material cost (US$) | Energy cost (US$) | Sheet cost (US$) | ||

| SG01 | 30.2 | 57 | 0.58 | 0.14 | 0.39 | 1.11 |

| SG02 | 29.8 | 44 | 0.58 | 0.11 | 0.39 | 1.07 |

| SG03 | 33.2 | 32 | 0.64 | 0.08 | 0.39 | 1.11 |

| SG04 | 30.4 | 32 | 0.59 | 0.08 | 0.39 | 1.06 |

| SG05 | 39.0 | 74 | 0.75 | 0.18 | 0.39 | 1.32 |

| SG06 | 21.0 | 20 | 0.41 | 0.05 | 0.39 | 0.85 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).