1. Introduction

There are places in the world that have been inhabited for thousands of years and have therefore accumulated, over time, a historical, cultural, and architectural heritage of immense value. One of these places is Italy, a country that has a vast urban heritage of exceptional historical and architectural value which, unfortunately, is often endangered and sometimes destroyed by frequent earthquakes of high magnitude. In the past, it was almost always preferred to rebuild “as it was and where it was,” i.e. in the same places affected by the earthquake, to preserve the precious cultural memory of areas inhabited for thousands of years. However, not all urban fabric damaged by an earthquake is necessarily of high value and significance. If the affected building has no historical or architectural value and is in areas of high geological or seismic risk, it is worth considering whether it is geoethically and economically acceptable to continue rebuilding in areas so highly exposed to geodynamic disasters.

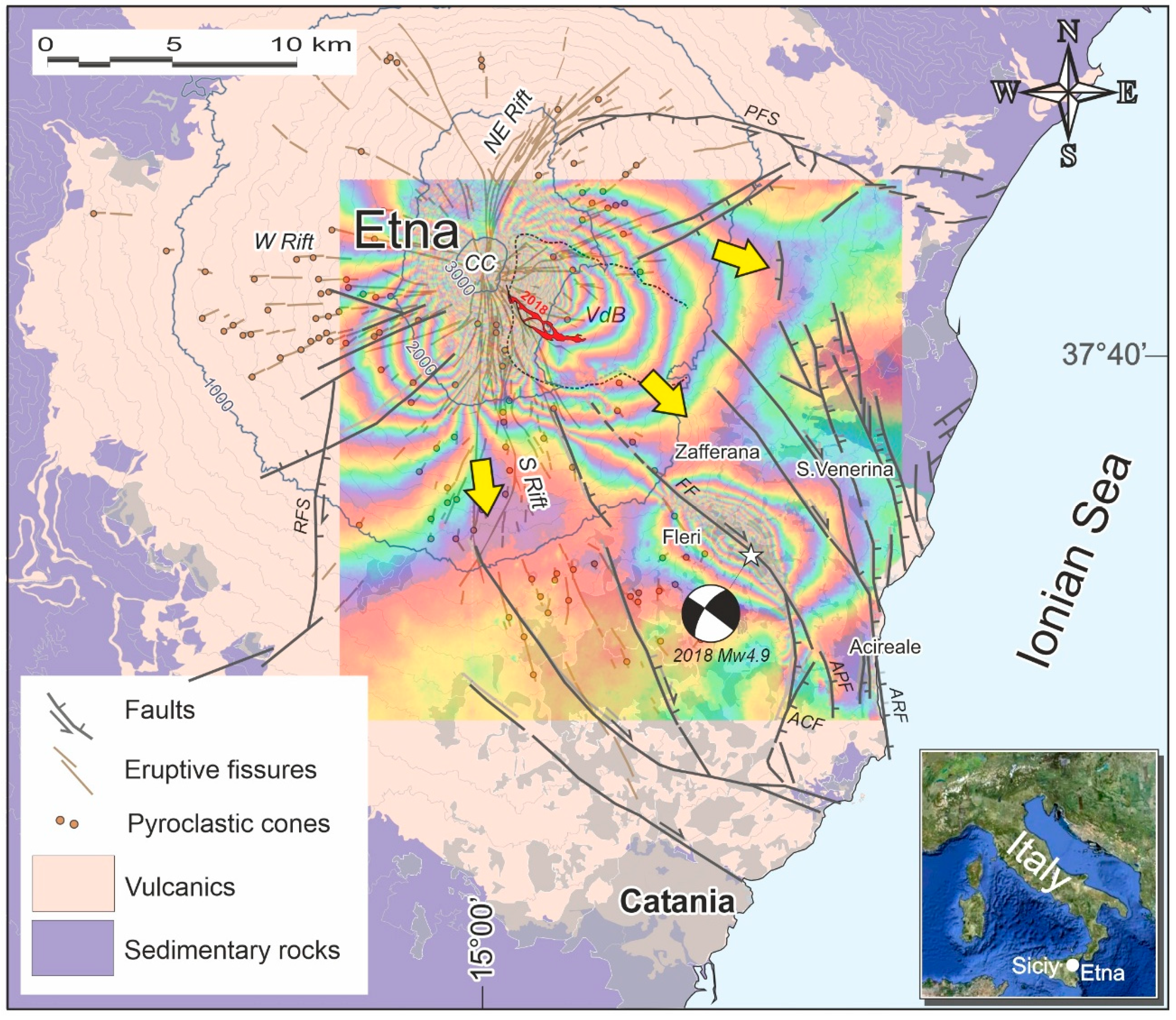

Mount Etna is one of the most persistently active and largest strato-volcanoes on Earth (3404 m above sea level), which generates frequent eruptions either from its summit vents [

1,

2,

3] or, less frequently, from fissures that open on its flanks [

4,

5](

Figure 1).

Lateral eruptions are potentially dangerous for the approximately one million people living on the slopes of the volcano, as lava flows can quickly bury entire villages [

7,

8,

9]. In addition to this, Etna's populations are exposed to the seismic risk generated by numerous active surface faults that mainly cross the eastern flank of the volcano [

10,

11], which is subject to slow but continuous collapse phenomena [

12,

13]. Often, deformations of the eastern flank accelerate during lateral eruptions, suggesting a clear cause-effect relationship between the two phenomena [

14,

15,

16].

Between 24 and 26 December 2018, a brief lateral eruption of Etna occurred [

17,

18,

19], which was fed by a ~2 km long fissure opened in the high western wall of the Valle del Bove erosive depression (VdB in

Figure 1). The lava flow descended along the western wall of the valley, then expanding eastwards to reach a maximum length of about three kilometers, but remaining confined within a desert area [

18] and therefore without causing any damage to houses and man-made infrastructures.

The eruption, however, was accompanied by several thousand earthquakes within a few weeks and considerable ground deformations focused both along the eruptive fissure and on the slopes of the volcano [

6]. The most energetic of these earthquakes (Mw 4.9), with a very shallow hypocenter (a few hundred meters), occurred at 03:19:14 local time on 26 December 2018, originating from the movement of the Fiandaca fault and characterized by noticeable coseismic ruptures observed on the ground along a strip of land tens to a few hundred meters wide and about 10 km long [

6,

20,

21,

22]. This resulted in damaging over three thousand buildings in an area of ~205 km

2, forcing thousands of people to permanently abandon their homes [

23]. The worst affected area was the surface fault zone, where the seismic shaking was superimposed by the destruction of buildings caused by the fracturing of the buildings' foundation substrate.

At the end of 2019, the Italian government appointed a Special Commissioner for the reconstruction of the areas affected by the earthquake [

24]. In this article, we will describe how the government Commissioner's Office tackled the reconstruction of the area affected by the earthquake, starting with the mapping of the areas at highest geological risk and continuing with the planning of interventions in the territory and assistance to the affected populations, based also on psychological assessments. This approach has proved effective both economically, as it has optimized the economic resources made available for reconstruction, and geo-ethically, as it has moved many families away from the riskiest areas, preventing probable future disasters.

2. Materials and Methods

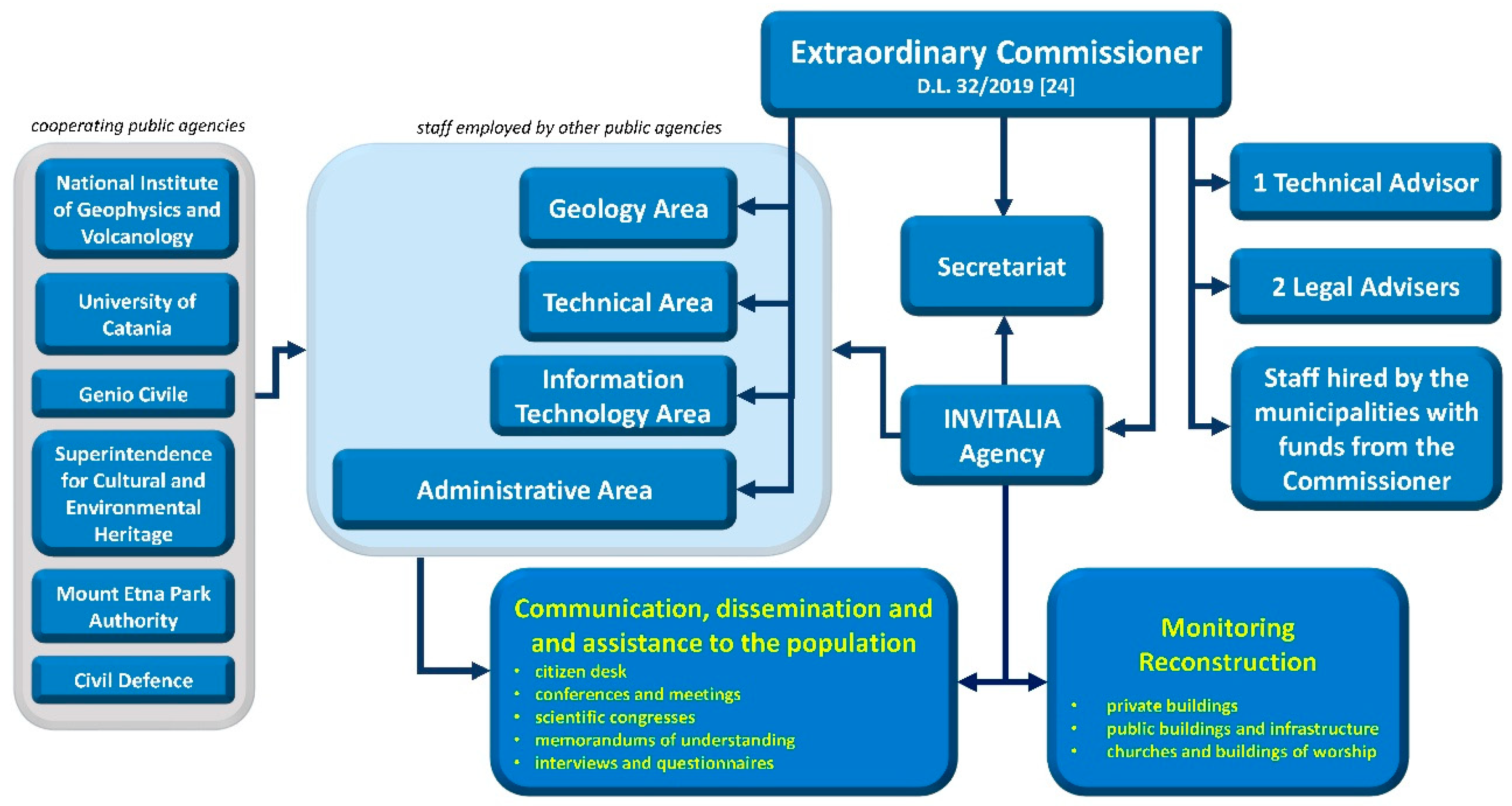

In the event of major natural disasters, the Italian Government usually appoints an Extraordinary Commissioner in charge of dealing with issues related to reconstruction, aid to the population and economic recovery of the affected territory. Accordingly, on 5 August 2019, by Decree of the President of the Council of Ministers [

24], an Extraordinary Commissioner was appointed for reconstruction in the territories of the municipalities of the Metropolitan City of Catania affected by the earthquakes of 26 December 2018. The Commissioner subsequently set up a Commissioner's Structure composed of 15 people from other public administrations, flanked by other staff from the national development agency INVITALIA, and around 40 additional technicians hired by the municipalities affected by the earthquake and supported financially by the Commissioner's availability. The staff thus identified ensures support to the Extraordinary Commissioner both in the phase of preparation of the commissioner's measures and for the study of all technical-legal issues related to the fulfilment of institutional tasks, guaranteeing the applicability of the provisions introduced, the analysis of the impact and feasibility of the regulations, and the streamlining and simplification of legislation.

The Commissioner's most urgent objective was immediately to start the reconstruction of the affected areas in a safe and timely manner. The geologists of the Commissioner's Structure analyzed the scientific publications concerning the earthquake and already available [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

25,

26,

27], supplementing them with further detailed geostructural studies. Homogeneous microzone maps were then drawn up in accordance with the guidelines for land management in areas subject to active and capable faults (ACF) [

28,

29]. The team was composed of experts from the Office of the Extraordinary Commissioner, the Civil Engineering Department (Department of the Sicilian Region), the national agency Invitalia, and geologists from the National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology (

Figure 2). The work was mainly coordinated and carried out by one of the authors [

30,

31,

32], who also holds the position of Deputy Commissioner and Head of the Geological Area of the Government Commission Structure (

https://commissariosismaareaetnea.it/).

The results were represented in maps published both in PDF format (scale 1:10,000) and WebGIS, [

https://commissariosismaareaetnea.it/]. The maps identify homogeneous micro-zones of active and capable faults (ACF) also delimit the areas affected by hydrogeological instability. Thus, it was possible to proceed with the drafting of the Government Commissioner's regulations and the adoption of the reconstruction plans.

Communication with the earthquake affected population was fundamental for the dissemination of the results acquired by the team of experts and for the acceptance of the consequent regulations concerning reconstruction and, in some cases, the relocation of buildings exposed to the greatest geo-structural risk (

Figure 2). Frequent meetings were organized with representatives of municipalities and citizens, including through online events during the COVID-19 pandemic. Numerous science conferences were organized each year, involving the main service-clubs (Kiwanis International, Lions, Rotary) and voluntary associations. An IT communication system called ‘Citizen's Desk’ was set up via the website

https://commissariosismaareaetnea.it/lo-sportello-telematico-del-cittadino/ with the aim of facilitating assistance to people affected by the earthquake and answering their questions. Finally, a collaboration was initiated with Prof. Mara Benadusi, professor at the Department of Political and Social Sciences at the University of Catania, and Dr. Mario Mattia, chief technologist at the National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology, through the project “Faglie di rischio: vulnerabilità, delocalizzazioni, spaesamenti e appaesamento,” focused on the local perception of seismic risk [

33].

3. Results

The earthquake of 26 December 2018 caused a co-seismic rupture of the ground approximately 10 km long in a strip of territory NW-SE and N-S oriented, varying in width from a few tens of meters to a few hundred meters. The activated fault is the Fiandaca fault, but on the south-eastern periphery, the movement transferred to the Aci Platani and Aci Catena faults, which were activated by aseismic creep in the hours/days following the earthquake. The Fiandaca fault showed right-lateral kinematics, while the other faults moved mainly with extensional movements [

20,

21,

22,

34].

The Fiandaca fault has caused numerous earthquakes in historical times [

35]; those of 1894, 1907 and 1984 caused damage and ground fracturing in many parts overlapping those that occurred in 2018, demonstrating the high hazard of the fault both due to the magnitude and shallowness of the hypocenters and its ability to generate extensive zones of co-seismic fracturing.

3.1. The Reconstruction: From Structural Maps to Commissarial Ordinances

The map realized by the team of experts coordinated by the Commissarial Structure Commission Structure identifies the position of the faults that activated on 26 December 2018 and circumscribes around them three types of ‘homogeneous micro-zones’ in seismic perspective: the Zone of Attention (ZA

ACF), at least 400 meters wide around the fault; the Zone of Susceptibility (ZS

ACF), at least 160 meters wide around the fault; and the Respect Zone (ZR

ACF), the most dangerous, with a minimum width of 30 meters around the surface fault plane [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. Once this map was created, it was possible to issue the Commissarial Ordinances for reconstruction which decree building regulations and the allocation of financial contributions (all regulations issued by the Commissioner are published here:

https://commissariosismaareaetnea.it/argomento-provvedimenti/ordinanze/). A plan was therefore drawn up for the reconstruction of public infrastructure and buildings, a plan for the ecclesiastical and religious buildings, and finally a plan for the private buildings. The amount of financial aid granted by the Commissioner was proportional to the damage suffered by each building, with the aim of repairing or rebuilding it in a modern, earthquake-proof manner and therefore to a higher safety standard than the existing structure. The total cost of the reconstruction amounts, at the time of writing this article, to just under €250 million, including both the cost of personnel employed at the Commission Structure and at the nine municipalities affected by the earthquake, as well as any other type of expenditure functional to reconstruction and economic recovery.

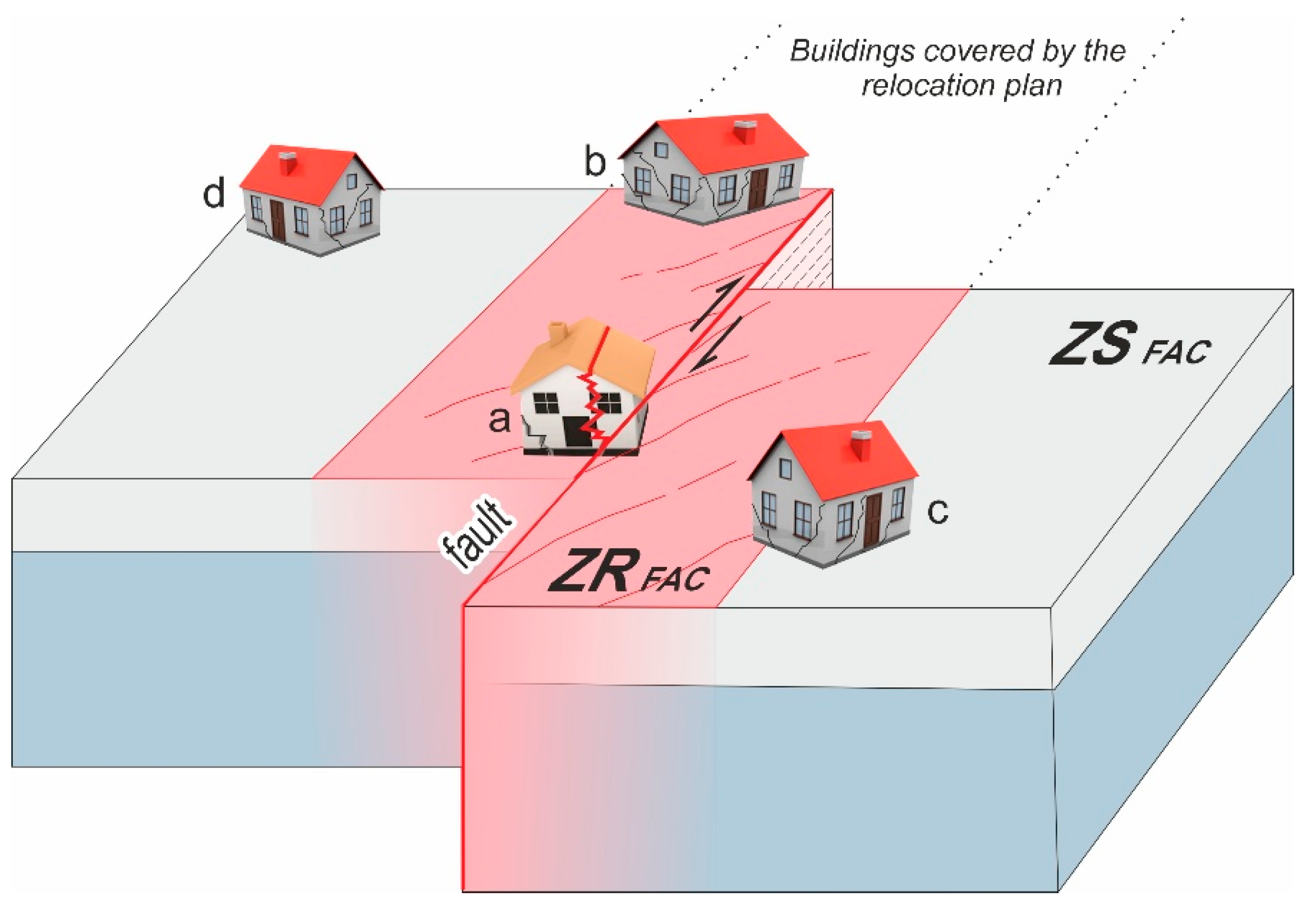

In areas not directly affected by surface faults, citizens and public institutions were immediately able to submit projects accompanied by in-depth geological investigations and surveys that improved the understanding of the geological substrate in each specific project area. Some geological and geophysical surveys were therefore indicated as necessary for the presentation of the projects, proportionate to both the size of the building structure and the geological and geomorphological context in which it is located. A more in-depth understanding of the geostructural context was required within the zone of Attention (ZA

ACF) and Zone of Susceptibility (ZS

ACF) to rule out the presence of faults in the building footprint or in its immediate vicinity (

Figure 3).

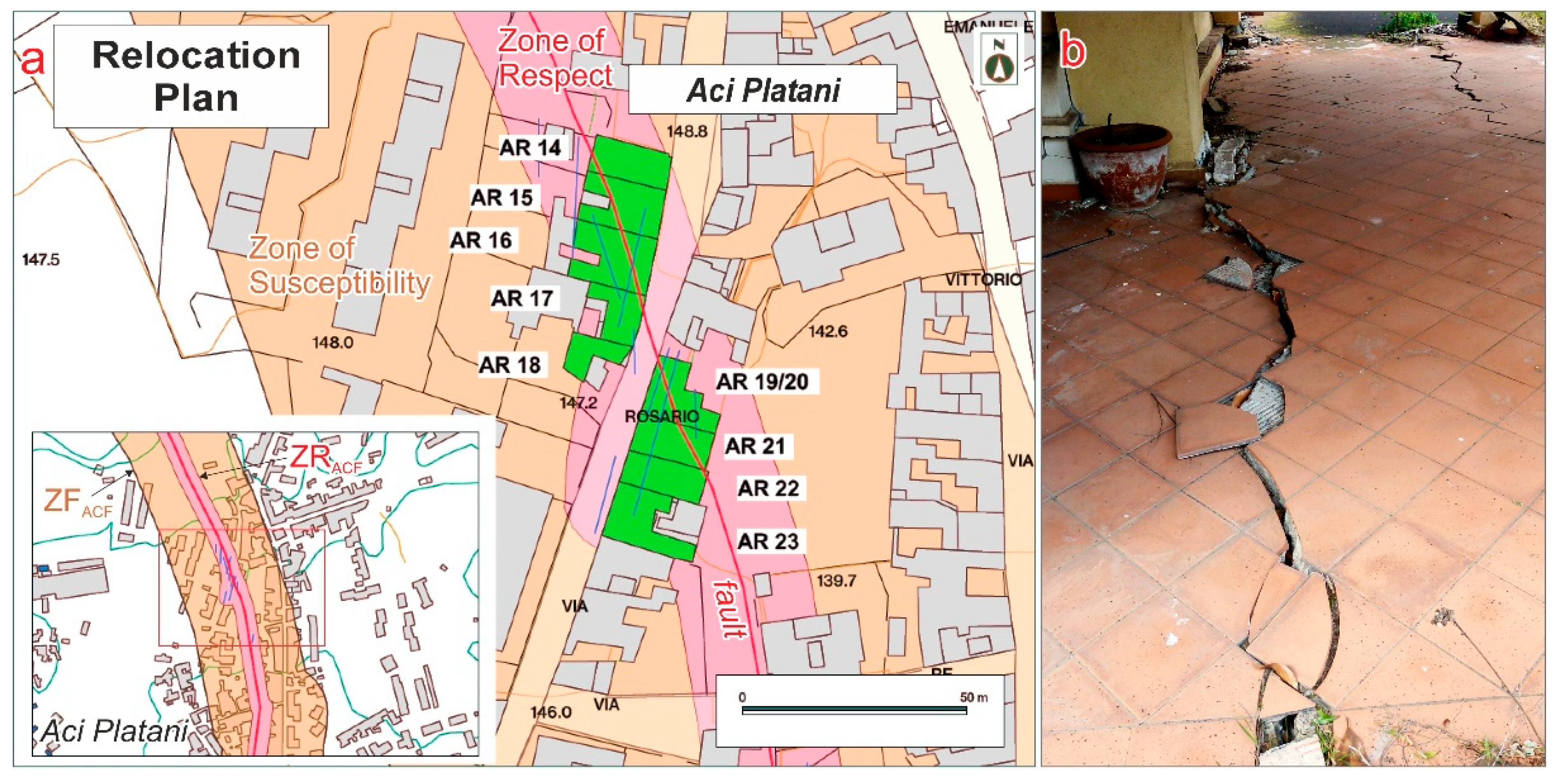

3.2. The Relocation Plan, a Geoethical Choice

Buildings located within the Zone of Respect (ZR

ACF), being subject not only to seismic shocks generated by the displacement of the fault plane but also to fracturing (faulting) of the ground beneath their foundations, have not been rebuilt in the same place. A relocation plan has been drawn up for them (

Figure 4)[

36]. This strategy was implemented to ensure the safety of citizens and to avoid spending resources on reconstruction of buildings that are at high risk of collapse within a few years or decades, given the high frequency of activity of the Fiandaca Fault [

35].

The plan provides for the voluntary relocation of 58 buildings which contained 122 housing units at a total cost of approximately €33 million, regulated by Commissioner's Order No. 18 of December 21, 2020 [

37]. The ordinance stipulates that owners of damaged properties located within the Zone of Respect (ZR

ACF) (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) will be granted financial assistance equivalent to the value of the property to be relocated. After the demolition of the building damaged by the earthquake, owners are offered the opportunity to purchase an existing building in one of the nine municipalities affected by the earthquake, or to build a new one in a seismically and geologically safer area.

However, there is another side to the coin: the relocation of a building, especially when it is located within a long-established urban area, forces entire families to “emigrate” elsewhere. This is perceived by the community as a loss of economic (territorial) and social (relational) value, which must therefore be mitigated as much as possible. In fact, especially when communities are small, as in the case of the villages of Fleri (2432 inhabitants) and Aci Platani (3594 inhabitants), which are particularly affected by the relocation plan (see example in

Figure 4), the loss of dozens of families can represent a significant socio-economic challenge. Compensation has therefore been provided for the community that remains in these villages. The land on which the relocated buildings stood has been transferred free of charge to the municipalities concerned, which will also receive adequate financial resources from the Commissioner to redevelop these areas through the construction of urban parks and green areas, roads, and parking lots (

Figure 4a), i.e., works compatible with the geological fragility of these sites and for the free use of local communities.

4. Discussion

In the recent past, Italy has experienced disastrous earthquakes that resulted in the destruction of entire towns that were never rebuilt in the same places. Following the Belice earthquake of 1968 (Mw6.5), for example, several towns were relocated or rebuilt in new areas. Of these, Gibellina, Poggioreale, Salaparuta and Montevago were among the hardest hit. Gibellina was rebuilt about 18 km from the original site, with modern and innovative architecture [

38,

39,

40,

41]. In terms of economic contributions, the Italian government allocated funds for reconstruction and relocation of inhabitants, but the management of aid has often been criticized for its slowness and lack of a planning vision appropriate to the socio-economic context of the affected area [

39,

40]. In the case of the 1980 Irpinia earthquake (Mw6.9), many villages were evacuated and rebuilt elsewhere. Among the towns affected were Conza della Campania, Sant'Angelo dei Lombardi, and Lioni [

41,

42,

43]. Again, the Italian government provided financial contributions to rebuild homes and infrastructure, but there was controversy over the distribution of funds and transparency in management [

43,

44,

45].

These events deeply marked local communities, transforming the urban and social landscape of the affected areas. These places are not only symbols of past tragedies, but also warnings for the future. They remind us how important it is to design resilient cities and take preventive measures to safeguard lives and communities.

The situation brought about by the 2018 Etna earthquake is very different from the cases mentioned above. Relocation involved not entire towns but only individual buildings or part of individual neighborhoods, due to the unbiased geostructural hazard of the sites where those buildings were located (see the surface faulting in

Figure 4b and

Figure 5). Moreover, the relocation was planned immediately after the earthquake, following specific studies that recommended it, all authorities with specific responsibilities in the field of land-use planning (Genio Civile of Catania-Sicilian Region, Superintendency for Cultural and Environmental Heritage, Etna Park, Municipalities, Civil Protection) were involved. The result was, therefore, materialized in a few months [

30,

31,

32], so that most of the citizens involved in the relocation of their homes were able to move into their new homes almost immediately [

36,

37].

Nevertheless, we are aware, and have experienced during this study, that leaving one's home is never an easy decision to make, even when there are strong reasons supporting the need to move to safer places.

4.1. The Reaction of the Population Affected by the Relocation

The reactions of the population to the relocation plan proposed by the Commissioner were many and, at times, opposite. There are those who immediately accepted favorably and seized the opportunity offered by the government to move their homes away from a dangerous territory and those, on the other hand, who strenuously opposed this proposal, interpreting it as a hostile act and trying, therefore, to question the relocation plan by seeking additional technical opinions adhering to their expectations to remain living in the same places in which they had lived until the date of the earthquake [

23,

46]. In one emblematic case (see faulting effects shown in

Figure 5e,g), a citizen, at his own expense, had a paleo-seismological trench interpreted by specialists in the field [

22,

47], in the hope of refuting the surface evidence shown on the commissarial map: an attempt that was ultimately in vain, since the trench only further clarified the surface geo-structural evidence, thus confirming the extreme urgency of relocating his home [

46,

47].

4.1.1. Insufficient Information or Irrational Choices

We, therefore, reflected on these reactions of such contrasting signs, promoting opportunities to meet with the population involved in the relocation plan. Initially, we asked ourselves why the negative reactions occurred, researching the reasons behind the decision of some individuals to live in dangerous places, for example, areas close to seismogenic faults or areas highly susceptible to the invasion of lava flows. We have ascertained that, often, this decision is made based on a lack of sufficient information: many people are not aware of the high danger of the Italian geological landscape [

39,

41,

44] and, in particular, of active volcanic regions such as those in Etna.

Sometimes, however, despite a generic awareness of the threat, some individuals choose to establish their residence in areas of high hazard induced by natural phenomena.

4.1.2. Perception, Minimization, and Denial of Risk

To explain these behaviors, we started from the consideration that earthquakes and volcanic eruptions are sudden, discontinuous, and unpredictable events. As a result, the threat is not always perceived by the population [

48,

49], even when the risk is depicted in maps that are already usable and known. In cases of impending calamitous events, people may deploy defensive strategies that they use to cope with stressful events and to protect themselves from emotions and thoughts that they find unbearable [

50]; in this specific case, people may: a) minimize the severity of the danger, b) deny its existence, and c) use “magical thinking”.

Those who unjustifiably minimize the problem are incapable of handling the emotional impact of the information they receive, so they reduce its value by aligning it with their psychological, emotional, and cognitive capacities. Those who want to build their house, for example, reassure themselves by saying, “

We will build a house that can withstand any earthquake. There is no reason to worry if such an event occurs.” Those, on the other hand, who deny the existence of the problem, “erase” it from their consciousness. This may occur for the same reasons mentioned above, but in this case, it indicates even more modest personal resources. For example, such people may claim, “...

but what will it be for a little earth shaking...!” The most extreme “deniers” also include those who do not believe in science and take refuge in folk memories or personal experiences, which, however, represent only some of the possible scenarios, i.e., those most comfortable and convenient to them. For example, certain individuals who have survived an earthquake assume the belief that such a positive experience will certainly be replicated in the future. Finally, in the case of magical thinking, people tend to rely on intuitions and connections that are not logical and/or based on unscientific knowledge. The basis for such claims lies in one's own personal experiences or those of close people, which, however, are not representative of the various possible scenarios [

50,

51]. An example of the use of magical thinking is the following: “

my grandfather told me that his house was spared by the earthquake, surely I will be spared too.”

These coping behaviors enacted by individuals to cope with and manage stressful events, have been widely documented in humans and are often applied, with varying degrees of awareness, in situations of psychological and emotional distress [

50,

51,

52,

53,

54].

4.1.3. An Opposite Reaction: Excessive Fear

An alternative and inverse response to the previous ones is a reaction of very intense fear, which when it reaches high levels reduces the individual's lucidity and ability to reason rationally. Following the revelation of a potential or probable threat, some individuals tend to expect only the most adverse expected scenarios. This leads to unjustifiably magnifying their concerns, rather than realistically assessing situations. The psychological distress experienced by these people because of the prospect of a potential disaster can have a significant impact on their daily lives [

50,

54,

55]. For example, despite having taken all necessary precautions, such people may still experience apprehension and manifest high anxiety about seismic events, even if they dwell in a modern earthquake-resistant building located a considerable distance from active faults.

This also results in prolonged periods of insomnia caused by apprehension about hypothetical future traumatic experiences associated with a hypothetical earthquake [

52]. This reaction can be particularly intense in individuals who have already experienced an earthquake and consequently suffered significant damage to their homes. Impactful experiences such as these can leave deep traces in the mind and body, leading to a condition of hypervigilance and a chronic stress response [

50,

51,

52,

54,

55].

4.1.4. Pathology or Defensive Strategies?

It is important to emphasize that the behaviors described earlier do not necessarily indicate the presence of pathology. Rather, they represent defensive strategies that people use to cope with uncomfortable situations or that force them to leave their comfort zone, i.e., their safe place, in this specific case represented by the building and/or neighborhood in which they reside and live.

The psychological impact of relocating one's home is considerable and can be experienced negatively, particularly for individuals who are emotionally vulnerable or who have a history of prior economic or social hardship determined by whatever reason. The meaning subjectively attributed to one's home is also part of these dynamics: the home not only represents a physical building, but is also a repository of memories, affections, and social ties. As an illustration, consider an individual who has invested emotionally and financially in the construction of his or her home, often the only one in his or her possession, demonstrating an unwavering commitment to the project, making considerable personal sacrifices and dedicating years, if not decades, to the undertaking. Then, unexpectedly, and suddenly, an earthquake causes irreparable damage to his home, wiping out the fruit of his hard work in a matter of seconds. It is intuitable to conclude that that person, in that situation, feels a profound sense of loss, sadness and disorientation, missing a clear point of reference in his life and having to, then, confront the stark reality of the destruction of a place they previously perceived as safe and welcoming. The destruction of houses of worship, constituting places of collective gathering, can also represent a loss of identity (

Figure 6).

The loss of one's home, in symbolic terms, represents the collapse of a fundamental point of reference for the lives of all of us, that is, the absence of a safe place to return to, the crumbling of memories to which we are attached, which brings with it emotions that can procure an almost physical ache: fear, anger, bewilderment, confusion, abandonment, sadness, emptiness. We should, however, expect reactions to vary from individual to individual, depending on each person's life experience, cognitive abilities, and cultural, social, and economic resources [

55]. Such experiences can be classified as “biographical shock,” [

50,

51,

52,

53] a term used to describe a moment in an individual's history that takes on the role of a watershed, marking a before and after in his or her life.

4.2. The Importance of Empathetic Dialogue with Earthquake Victims

What we have come to realize during this study is that simply knowing things, that is, possessing adequate cognitive and cultural means to fully understand information about the dangerousness of a certain place, is not enough to take conservative and/or wise attitudes. Knowing is not enough. This occurs because people are capable of self-deception and even distortion of reality when these actions serve to protect themselves from emotions and thoughts, they find untenable.

This highlights the importance of considering psychological assistance as a crucial and complementary element of support for people affected by natural disasters. In providing psychological assistance, it is essential to act early by diversifying the approach according to the type and size of the disaster, the planned interventions, and the expected time frame for recovery. The scope of support, therefore, should go beyond the obvious economic assistance. It should, that is, aim to help people cope with the difficulties they encounter in the immediate aftermath of the tragedy, providing additional emotional support to deal with the resulting lack of fundamental reference points for their existence. In the case of the 2018 post-earthquake reconstruction, the dialogue from the very beginning between the Commissioner's Structure technicians and the earthquake-affected population (

Figure 7), particularly those involved in relocation, is a significant first step in understanding the multifaceted nature of the necessary support, beyond simple economic assistance, based on empathetic sharing of distress.

5. Conclusions

In the context of natural disasters, the reconstruction of affected areas is not always geoethically justifiable. In the aftermath of a major earthquake, it is imperative to identify zones with extreme geological and seismic hazards and prioritize the relocation of buildings in the most exposed areas to reduce urban density and mitigate future risks. Nevertheless, a significant challenge remains in establishing a clear and universally accepted threshold for determining when a risk reaches a level that is deemed "unacceptably high," thereby justifying such intervention. In instances of recurrent surface faulting that consistently affect the same locations, we consider it geoethically appropriate to relocate buildings situated on or in proximity to active fault lines.

In addition to the implementation of physical mitigation efforts, it is imperative to ensure that affected populations possess a comprehensive understanding of the geological context of their environment and the measures available to reduce future disaster impacts. Effective communication by government authorities is crucial for fostering public acceptance. Transparency and empathy are paramount in explaining the rationale behind planning decisions (

Figure 7).

It is noteworthy that the methodology developed in the Etna region for managing buildings exposed to extreme geological and seismic risks has been successfully adapted for post-earthquake reconstruction projects in central Italy (2016–2017 earthquakes) [

56] and Ischia (2017 earthquake) [

57]. Appropriate regulatory modifications that account for local specifics have resulted in the emergence of a practical and geoethically sound framework for guiding the socio-economic recovery of urban areas affected by recurrent surface faulting, both in Italy and globally.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology and validation, M.N.; formal analysis, geological and seismological investigation, M.N.; psychological investigation, E.N.; writing—original draft preparation, M.N. and E.N.; writing—review and editing, M.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We express our deep gratitude to C. Doglioni, former President of the National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology, and to S. Scalia, Extraordinary Government Commissioner for the Reconstruction of the Earthquake-affected Areas of Etna earthquake 2018, for their valuable and constant support throughout this project. We would also like to thank M. L. Carbone, A. M. Londino, G. Licciardello, and G. Scapellato for their assistance in the preparation of the relocation plan, and the geologists of the Genio Civile of Catania F. Chiavetta, G. Filetti, and C. Marino, for their contribution in the elaboration of the map of faults activated by the earthquake of December 26, 2018.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Branca, S.; Del Carlo, P.; Behncke, B.; Bonfanti, P. Database of Etna’s historical eruptions (DANTE). Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV) 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acocella, V.; Neri, N.; Behncke, B.; Bonforte, A.; Del Negro, C.; Ganci, G. Why does a mature volcano need new vents? The case of the New Southeast Crater at Etna. Front. Earth Sci. 2016, 4, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, M.; De Maio, M.; Crepaldi, S.; Suozzi, E.; Lavy, M.; Marchionatti, F.; Calvari, S.; Buongiorno, F. Topographic Maps of Mount Etna’s Summit Craters, updated to 15. Journal of Maps 2017, 13, 647–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, M.; Acocella, V.; Behncke, B.; Giammanco, S.; Mazzarini, F.; Rust, D. Structural analysis of the eruptive fissures at Mount Etna (Italy). Ann. Geophys. 2011, 54, 5–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappello, A.; Neri, M.; Acocella, V.; Gallo, G.; Vicari, A.; Del Negro, C. Spatial vent opening probability map of Mt. Etna volcano (Sicily, Italy). Bull. Volcanol. 2012, 74, 2083–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Novellis, V.; Atzori, S.; De Luca, C.; Manzo, M.; Valerio, E.; Bonano, M.; Cardaci, C.; Castaldo, R.; Di Bucci, D.; Manunta, M.; Onorato, G.; Pepe, S.; Solaro, G.; Tizzani, P.; Zinno, I.; Neri, M.; Lanari, R.; Casu, F. DInSAR analysis and analytical modeling of Mount Etna displacements: The December 2018 volcano-tectonic crisis. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behncke, B.; Neri, M.; Nagay, A. Lava flow hazard at Mount Etna (Italy): New data from a GIS-based study, in Kinematics and dynamics of lava flows; Manga, M., Ventura, G., Eds. Geol. Soc. Am. Spec. Pap. 2005, 396, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rongo, R.; Avolio, M. V.; Behncke, B.; D’Ambrosio, D.; Di Gregorio, S.; Lupiano, V.; Neri, M.; Spataro, W.; Crisci, G.M. Defining High Detailed Hazard Maps by a Cellular Automata approach: Application to Mt. Etna (Italy). Ann. Geophys. 2011, 54, 568–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Negro, C.; Cappello, A.; Neri, M., Bilotta; Hérault, A.; Ganci, G. Lava flow hazards at Etna volcano: constraints imposed by eruptive history and numerical simulations. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreca, G.; Bonforte, A.; Neri, M. A pilot GIS database of active faults of Mt. Etna (Sicily): A tool for integrated hazard evaluation. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2013, 251, 170–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Amico, S.; Azzaro, R.; Tusa, G.; Tuvè, T.; Varini, E. Volcano-tectonic seismicity and related hazard: a component of the multi-hazard assessment in the highly exposed region of Mt. Etna (Italy). Ann. Geophys. 2025, 68, V101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solaro, G.; Acocella, V.; Pepe, S.; Ruch, J.; Neri, M.; Sansosti, E. Anatomy of an unstable volcano through InSAR data: multiple processes affecting flank instability at Mt. Etna in 1994-2008. J. Geophys. Res. 2010, 115, B10405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siniscalchi, A.; Tripaldi, S.; Neri, M.; Balasco, M.; Romano, G.; Ruch, J.; Schiavone, D. Flank instabilitystructure of Mt. Etna inferred by a magnetotelluric survey. J. Geophys. Res. 2012, 117, B03216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, M.; Casu, F.; Acocella, V.; Solaro, G.; Pepe, S.; Berardino, P.; Sansosti, E.; Caltabiano, T.; Lundgren, P.; Lanari, R. Deformation and eruptions at Mt. Etna (Italy): a lesson from 15 years of observations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2009, 36, L02309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, M.; Di Bari, M.; Acocella, V.; Neri, M. Dike emplacement and flank instability at Mount Etna: Constraints from a poro-elastic-model of flank collapse. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2011, 199, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acocella, V.; Neri, M.; Norini, G. An overview of analogue models to understand a complex volcanic instability: application to Etna, Italy. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2013, 251, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonforte, A.; Guglielimno, F.; Piglisi, G. Large dyke intrusion and small eruption: The December 24, 2018 Mt. Etna eruption imaged by Sentinel-1 data. Terra Nova 2019, 31, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvari, S.; Billotta, G.; Bonaccorso, A.; Caltabiano, T.; Cappello, A.; Corradino, C.; Del Negro, C.; Ganci, G.; Neri, M.; Pecora, E.; Salerno, G.; Spampinato, L. The VEI 2 Christmas 2018 Etna Eruption: a small but intense eruptive event or the starting phase of a larger one? Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloisi, M.; et al. The 24 December 2018 eruptive intrusion at Etna volcano as revealed by multidisciplinary continuous deformation networks (CGPS, borehole strainmeters and tiltmeters). J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2020, 125, e2019JB019117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civico, R.; Pucci, S.; Nappi, R.; Azzaro, R.; Villani, F.; et al. Surface ruptures following the 26 December 2018, Mw 4.9, Mt. Etna earthquake, Sicily (Italy). J. Maps 2019, 15, 831–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, F.; Pucci, S.; Azzaro, R.; Civico, R.; Cinti, F.R.; et al. Surface ruptures database related to the 26 December 2018, MW 4.9 Mt. Etna earthquake, southern Italy. Scientific Data 2020, 7, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tringali, G.; Bella, D.; Livio, F.; Ferrario, M.F.; Groppelli, G.; et al. Fault rupture and aseismic creep accompanying the December 26, 2018, Mw 4. 9 Fleri earthquake (Mt. Etna, Italy): Factors affecting the surface faulting in a volcano-tectonic environment, Quaternary Int. 2023, 651, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, M.; Neri, E. Etna 2018 earthquake: rebuild or relocate? Applying geoethical principles to natural disaster recovery planning. J. Geoeth. Soc. Geosci. 2024, 2, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D.L. 32/2019 Disposizioni urgenti per il rilancio del settore dei contratti pubblici, per l'accelerazione degli interventi infrastrutturali, di rigenerazione urbana e di ricostruzione a seguito di eventi sismici. (19G00040) (GU Serie Generale n.92 del 18-04-2019), 2019; 55.

- EMERGEO, W.G. Il terremoto etneo del 26 dicembre 2018, Mw4.9: rilievo degli effetti di fagliazione cosismica superficiale. Rapporto INGV n. 1 del 21/01/2019. [CrossRef]

- EMERGEO, W.G. Photographic collection of the coseismic geological effects originated by the 26th December Etna (Sicily) earthquake. Misc. INGV. 2019, 48, 1–76. [Google Scholar]

- QUEST, W.G. Il terremoto etneo del 26 dicembre 2018, Mw4.9: rilievo degli effetti macrosismici. Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- Technical Commission on Seismic Microzonation, Land Use Guidelines for Areas with Active and Capable Faults (ACF), Conference of the Italian Regions and Autonomous Provinces – Civil Protection Department, Rome, 2015. https://www.centromicrozonazionesismica.it/documents/23/FAC_ing.pdf (accessed ). 1 May.

- SM Working Group. Guidelines for Seismic Microzonation, Conference of Regions and Autonomous Provinces of Italy – Civil Protection Department, Rome, 2015, https://www.centromicrozonazionesismica.it/documents/18/GuidelinesForSeismicMicrozonation.pdf, (accessed 1 May 2025).

- Neri, M. Area interessata da fagliazione superficiale in occasione del sisma del 26 dicembre 2018 conindividuazione preliminare della Zone di Attenzione (ZAFAC). Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri, Struttura Commissariale Ricostruzione Area Etnea – Area Geologia, 2020, https://commissariosismaareaetnea.it/ente/mappa-dellarea-interessata-da-fagliazione-superficiale-inoccasione-del-sisma-del-26-dicembre-2018/, (accessed 1 May 2025).

- Neri, M.; Carbone, M.L. Mappa WebGIS delle Aree interessate Fenomeni di Dissesto Idrogeologico nei Territori colpiti dal Sisma del 26 Dicembre 2018. Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri, Struttura Commissariale Ricostruzione Area Etnea – Area Geologia, 1 May.

- Neri, M.; Carbone, M.L.; Chiavetta, F.; Filetti, G.; Marino, C. Area interessata da fagliazione superficiale cosismica in occasione del terremoto del 26 dicembre 2018 con individuazione preliminare delle Zone di Suscettibilità (ZSFAC) e di Rispetto (ZRFAC). Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri, Struttura Commissariale Ricostruzione Area Etnea – Area Geologia, Regione Siciliana, Ufficio del Genio Civile di Catania, 1 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Benadusi, M.; Mattia, M.; Lo Bartolo, V. Faglie di rischio. Delocalizzazioni, spaesamenti e appaesamenti alle pendici del Monte Etna. Antropologia Pubblica 2024, 10, 55–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzaro, R.; Pucci, S.; Villani, F.; Civico, R.; Branca; et al. Surface Faulting of the 26 December 2018, Mw5 Earthquake at Mt. Etna Volcano (Italy): Geological Source Model and Implications for the Seismic Potential of the Fiandaca Fault. Tectonics 2022, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CMTE Working Group. Catalogo Macrosismico dei Terremoti Etnei, 1832–2008. Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, Catania.

- Piano per la delocalizzazione di edifici e unità immobiliari ad uso abitativo, produttivo e commerciale ricadenti nella Zona di Rispetto (ZRFAC) della mappa pubblicata sul sito del Commissario Straordinario il 18 agosto 2020. Primo stralcio. Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri Commissario Straordinario per la ricostruzione dell'area etnea - sisma 26 dicembre 2018, 1 May 2020. Available online: https://commissariosismaareaetnea.it/provvedimenti/piano-per-la-delocalizzazione-di-edifici-e-unita-immobiliari-ad-uso-abitativo-produttivo-e-commerciale-ricadenti-nella-zona-di-rispetto-zrfac-della-mappa-pubblicata-sul-sito-del-commissario-straord/.

- Ordinanza, n. 18/2020. Ordinanza n. 18 del 21 dicembre 2020, Delocalizzazione di edifici ad uso abitativo, produttivo e commerciale ricadenti nella Zona di Rispetto (ZRFAC) della mappa pubblicata dal Commissario Straordinario il 18 Agosto 2020, Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri Commissario Straordinario per la ricostruzione dell'area etnea - sisma 26 dicembre 2018, 2020. https://commissariosismaareaetnea.it/argomento-provvedimenti/ordinanze/.

- Azzaro, R.; Cascone, M.; Amantia, A. Earthquakes and ghost towns in Sicily: from the Valle del Belìce in 1968 to the Val di Noto in 1693. The first stage of the virtual seismic itinerary through Italy. Ann. Geophys. 2020, 63, SE106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caponetto, R.; D'Urso, S. Ancient Poggioreale: an opportunity for reflection on the topic of post-earthquake territory abandonment. Ann. Geophys. 2020, 63, SE109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappalardo, V.; Martinico, F. Gibellina, Salaparuta, Poggioreale and Montevago: about built environment underutilization and possible urban future. Ann. Geophys. 2020, 63, SE108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lucia, M.; Benassi, F.; Meroni, F.; Musacchio, G.; Pino, N. A.; Strozza, S. Seismic disasters and the demographic perspective: 1968, Belice and 1980, Irpinia-Basilicata (southern Italy) case studies. Ann. Geophys. 2020, 63, SE107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porfido, S.; Alessio, G.; Gaudiosi, G.; Nappi, N.; Michetti, A.M. The November 23rd, 1980 Irpinia-Lucania, Southern Italy Earthquake. Insights and Reviews 40 Years Later. Geosciences 2020, 66, 4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscariotolo, G.I. Reconstruction as a Long-Term Process. Memory, Experiences and Cultural Heritage in the Irpinia Post-Earthquake (November 23, 1980) Reprinted from. Geosciences 2020, 10, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, A.; Nicodemo, G. Reconstruction, recovery and socio-economic development of the Basilicata region, southern Italy: lessons and experience after the 1980 earthquake. Bull. Geophys. Oceanogr. 2022, 63, 619–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porfido, S.; Alessio, G.; Gaudiosi, G; Nappi, R.; Spiga, E. Some Considerations on the Seismic Event of 23 November 1980 (Southern Italy). Prevention and Treatment of Natural Disasters 2024, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, M.; Neri, E.; Leonardi, A. Geoethical principles applied to the reconstruction planning of natural disasters: the Etna 2018 earthquake case study, EGU General Assembly, 2025, Vienna, Austria, 27 Apr–, EGU25-9411. 2 May. [CrossRef]

- Tringali, G.; Bella, D.; Livio, F.; Blumetti, A. M.; Groppelli, G.; Guerrieri, L.; Neri, M.; Adorno, V.; Pettinato, R.; Trotta, S.; Michetti, A. M. New paleoseismological findings along the Fiandaca Fault reveal the dynamics of Etna volcano's eastern flank, EGU General Assembly, 2025, Vienna, Austria, 27 Apr–, EGU25-16385. 2 May. [CrossRef]

- Wachinger, G.; Renn, O.; Begg, C.; Kuhlicke, C. The Risk Perception Paradox—Implications for Governance and Communication of Natural Hazards. Risk Analysis 2013, 33, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crescimbene, M.; La Longa, F.; Camassi, R. What’s the Seismic Risk Perception in Italy? In Engineering Geology for Society and Territory, Lollino, G. et al., Eds., 2014, Vol. 7, Springer International Publishing, Switzerland, 69-75. [CrossRef]

- Kamaledini, M.; Azkia., M. The Psychosocial Consequences of Natural Disasters: A Case Study. Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly 2021, 6, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risen, J. L. Believing What We Do Not Believe: Acquiescence to Superstitious Beliefs and Other Powerful Intuitions. Psychological Rev. 2016, 123, 182–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, D.; Iacob, C.I.; Avram, E.; Arma, I. Emotional distress related to hazards and earthquake risk perception. Nat. Haz. 2021, 109, 2077–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S.; Lazarus, R.S. Ways of coping questionnaire, sampler set, manual, test booklet, scoring key; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, 1988; Available online: https://search.library.wisc.edu/catalog/999881684402121.

- Lingiardi, V.; Madeddu, F. I meccanismi di difesa, Cortina R. Ed., Milano, ISBN 9788832855609, 2022, 54 pp. Available online: https://www.raffaellocortina.it/scheda-libro/vittorio-lingiardi-fabio-madeddu/i-meccanismi-di-difesa-9788832855609-4049.html.

- Van Der Kolk, B. Il corpo accusa il colpo: mente, corpo e cervello nell'elaborazione delle memorie traumatiche, Cortina R., Ed. Milano, 2015, 501 p. Available online: https://www.raffaellocortina.it/scheda-libro/bessel-van-der-kolk/il-corpo-accusa-il-colpo-9788860307583-1630.htmlISBN 9788860307583.

- Ordinanza, n. 119/2021, Ordinanza n. 119 del 8 settembre 2021, Disciplina degli interventi in aree interessate da Faglie Attive e Capaci e da altri dissesti idrogeomorfologici, Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri, Commissario Straordinario Ricostruzione Sisma 2016, 2021. Available online: https://sisma2016.gov.it/ordinanze/.

- Ordinanza, n. 24/2023, Ordinanza n. 24 del 21 luglio 2023, Delocalizzazioni degli edifici danneggiati o distrutti ad uso abitativo o produttivo, Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri, Commissario Straordinario per la Ricostruzione nei territori dell’isola d’Ischia interessati dal sisma del 21 agosto 2017, 2023. Available online: https://sismaischia.it/sisma-ischia-2017/normativa-2/ordinanze-del-commissario-straordinario/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).