Submitted:

28 May 2025

Posted:

28 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation and Purification of OMW Complex Phenolic Polymer

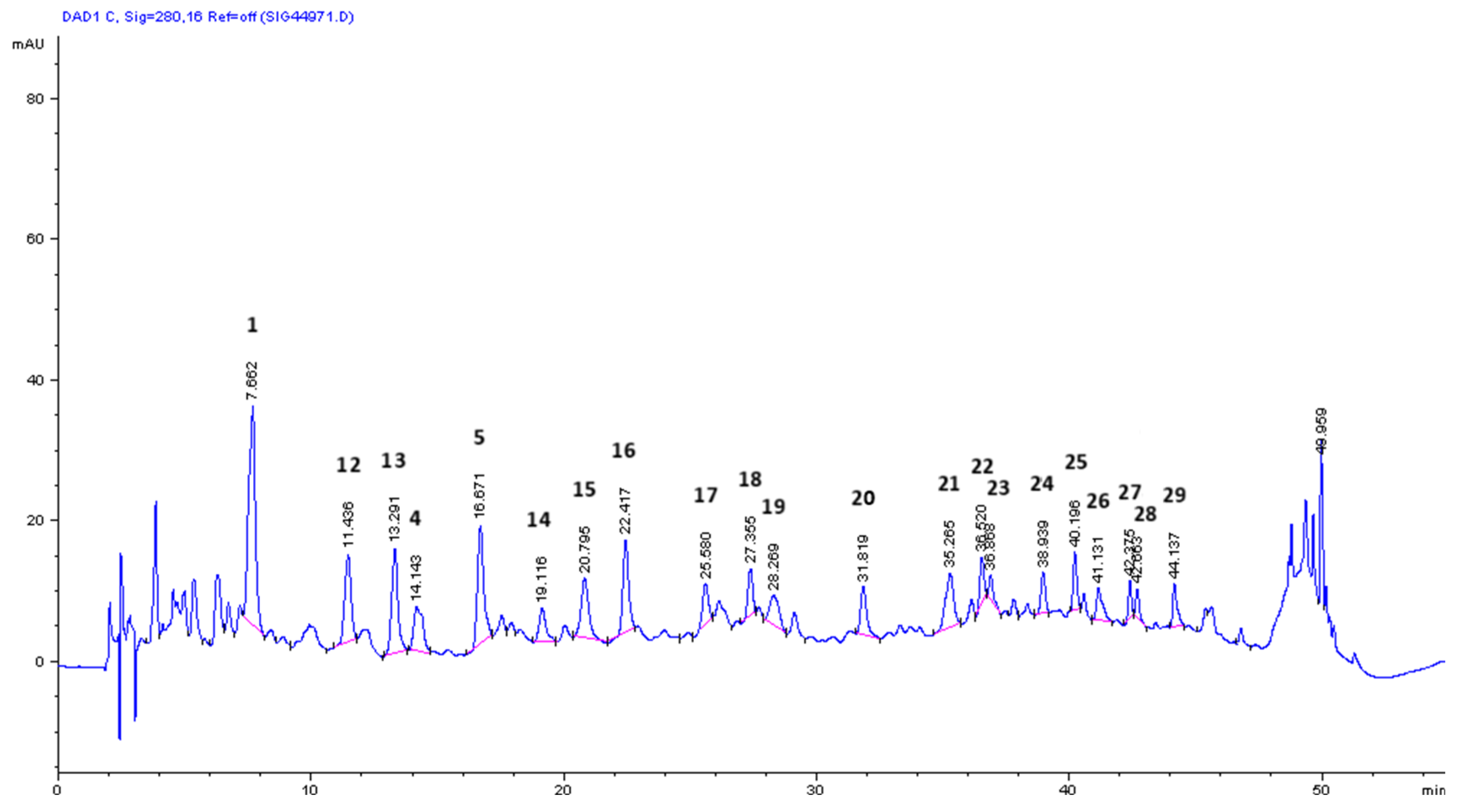

2.2. HPLC-DAD Chromatographic Analysis

2.3. Multi-Elemental Composition and Protein Content

2.4. Estimation of Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

2.5. Determination of Sugars by Gas Chromatography (Alditol Acetates)

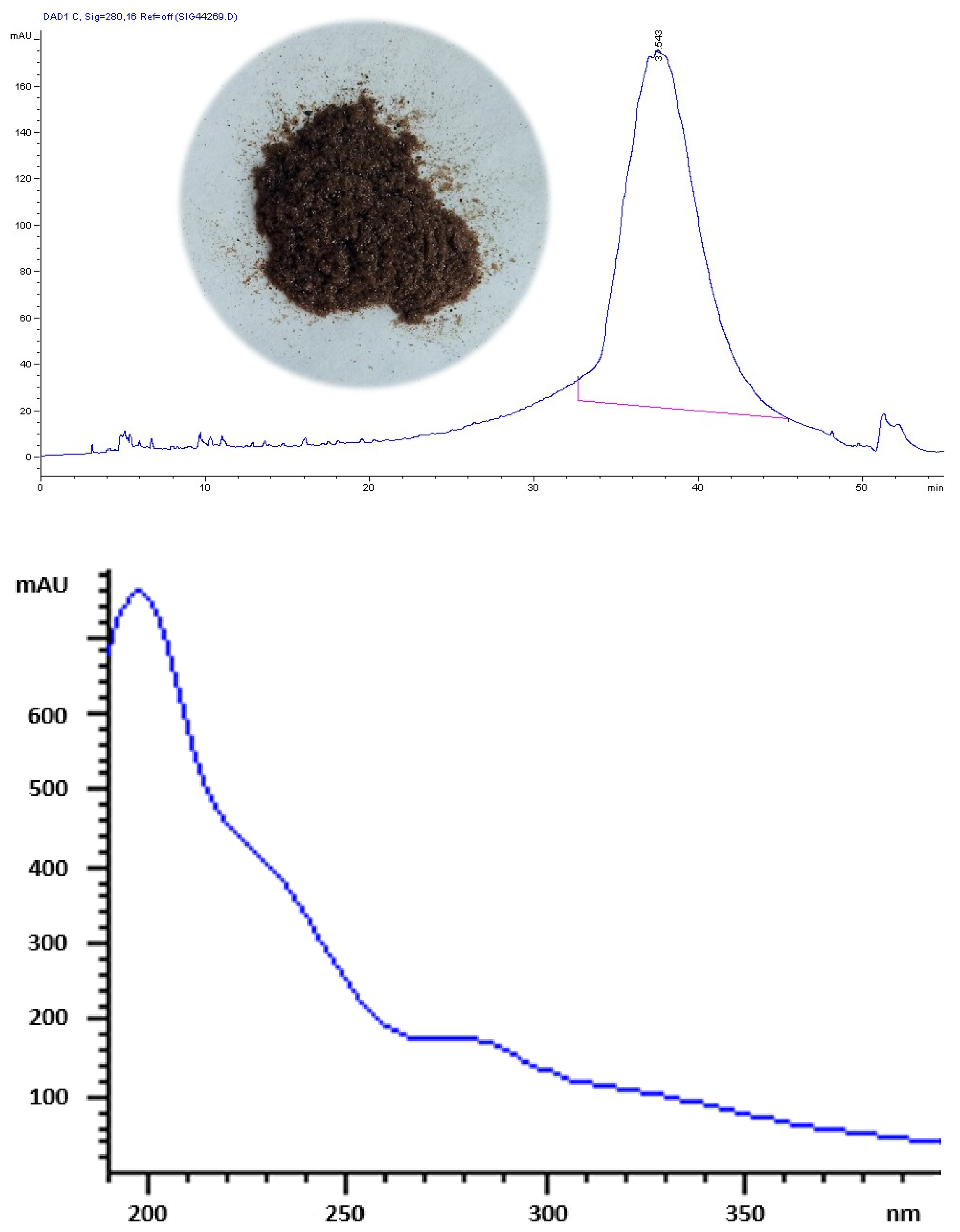

2.6. Estimation of Molecular Size by Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC)

2.7. Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR)-Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

2.8. NMR Spectroscopic Analysis

2.9. Acid and Basic Hydrolysis and Analysis of Products by Mass Spectrometry

2.10. Antioxidant Capacity Assays (DPPH, FRAP, ORAC and TEAC)

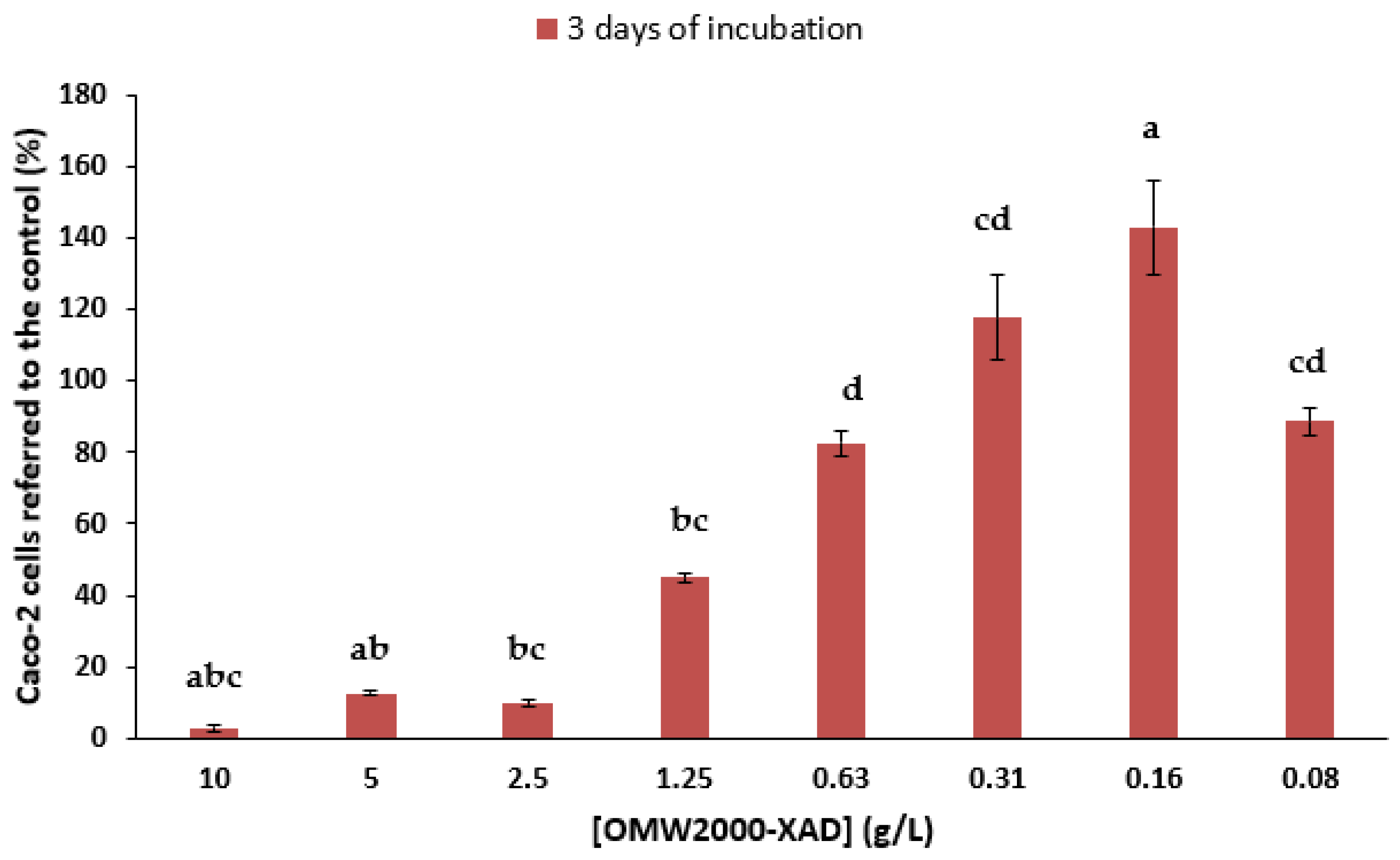

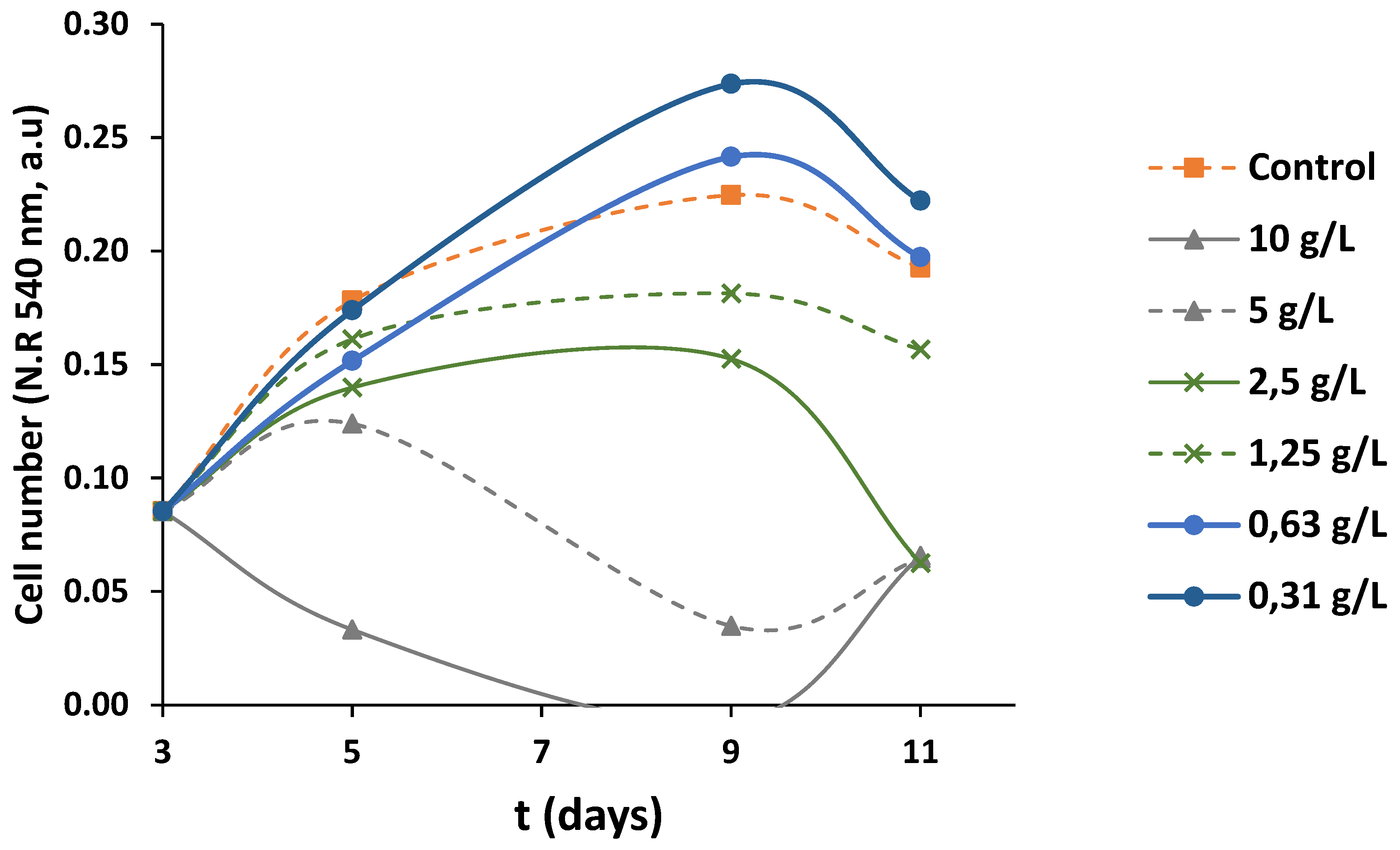

2.11. Anti-Proliferative Activity of OMW-2000XAD

2.11.1. Caco-2 Cell Culture

2.11.2. Caco-2 Cell Line Proliferation Assay with OMW-2000XAD

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Composition Analysis

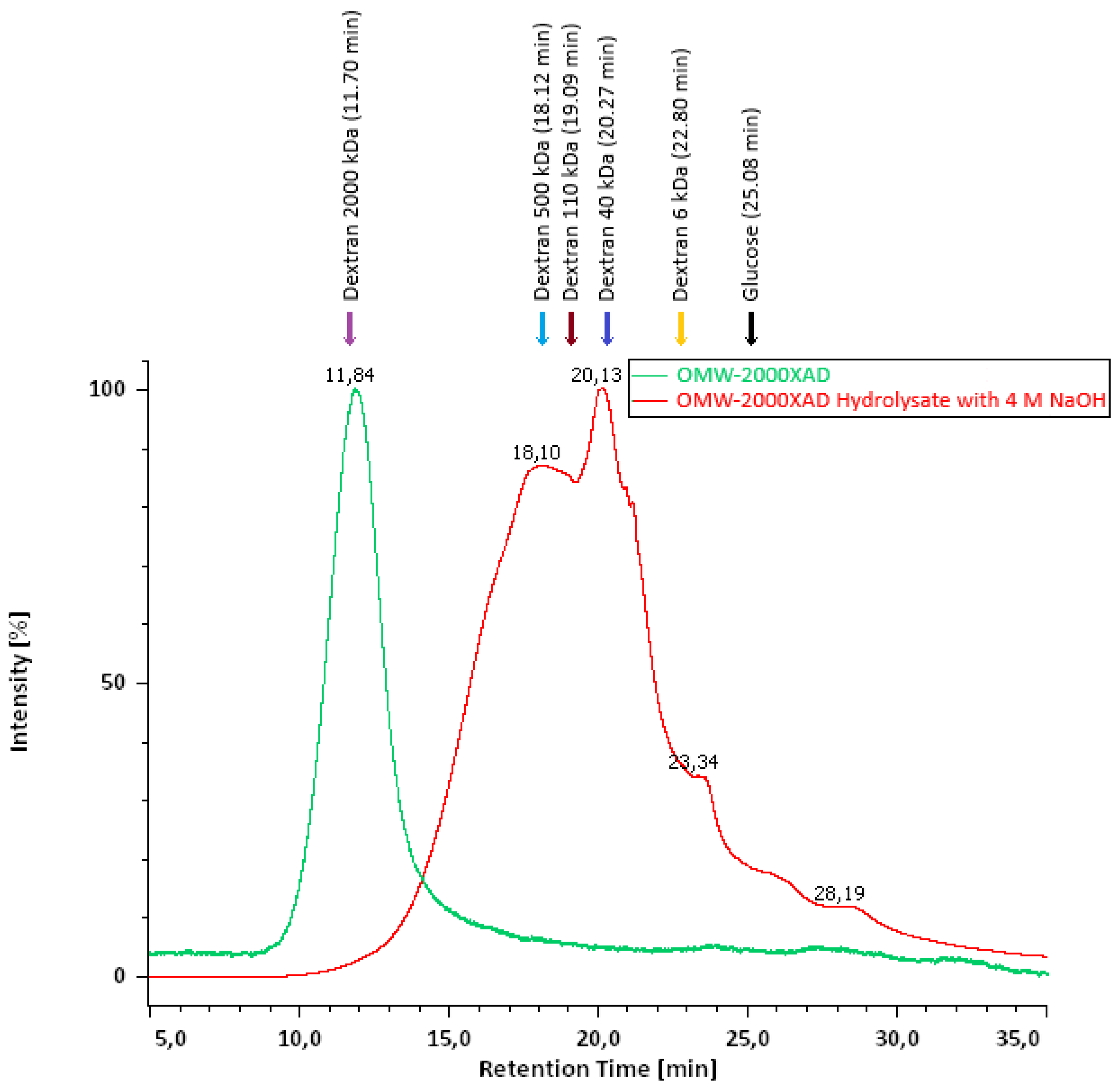

3.2. Gel Filtration Chromatography

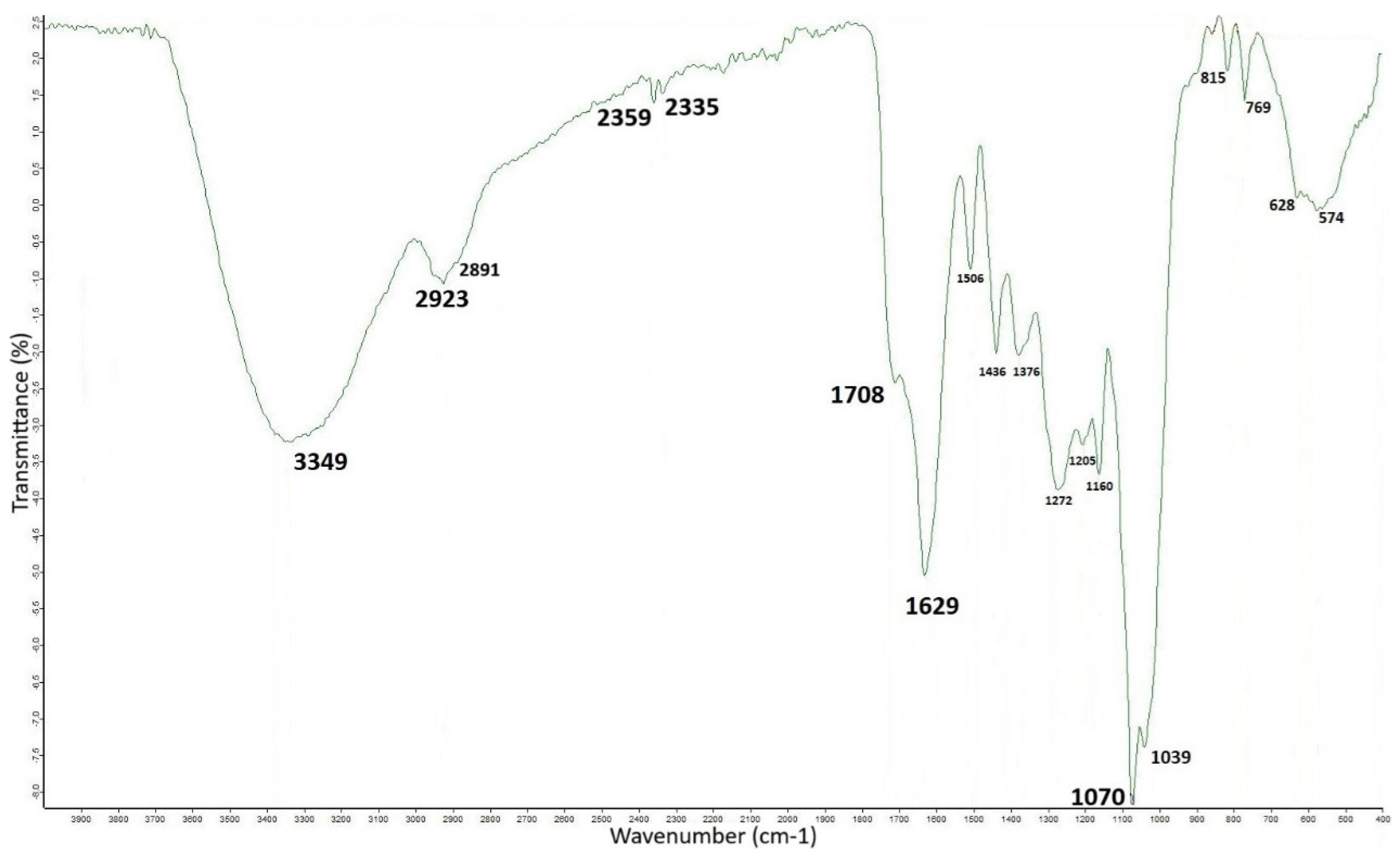

3.3. FTIR Analysis of OMW-2000XAD

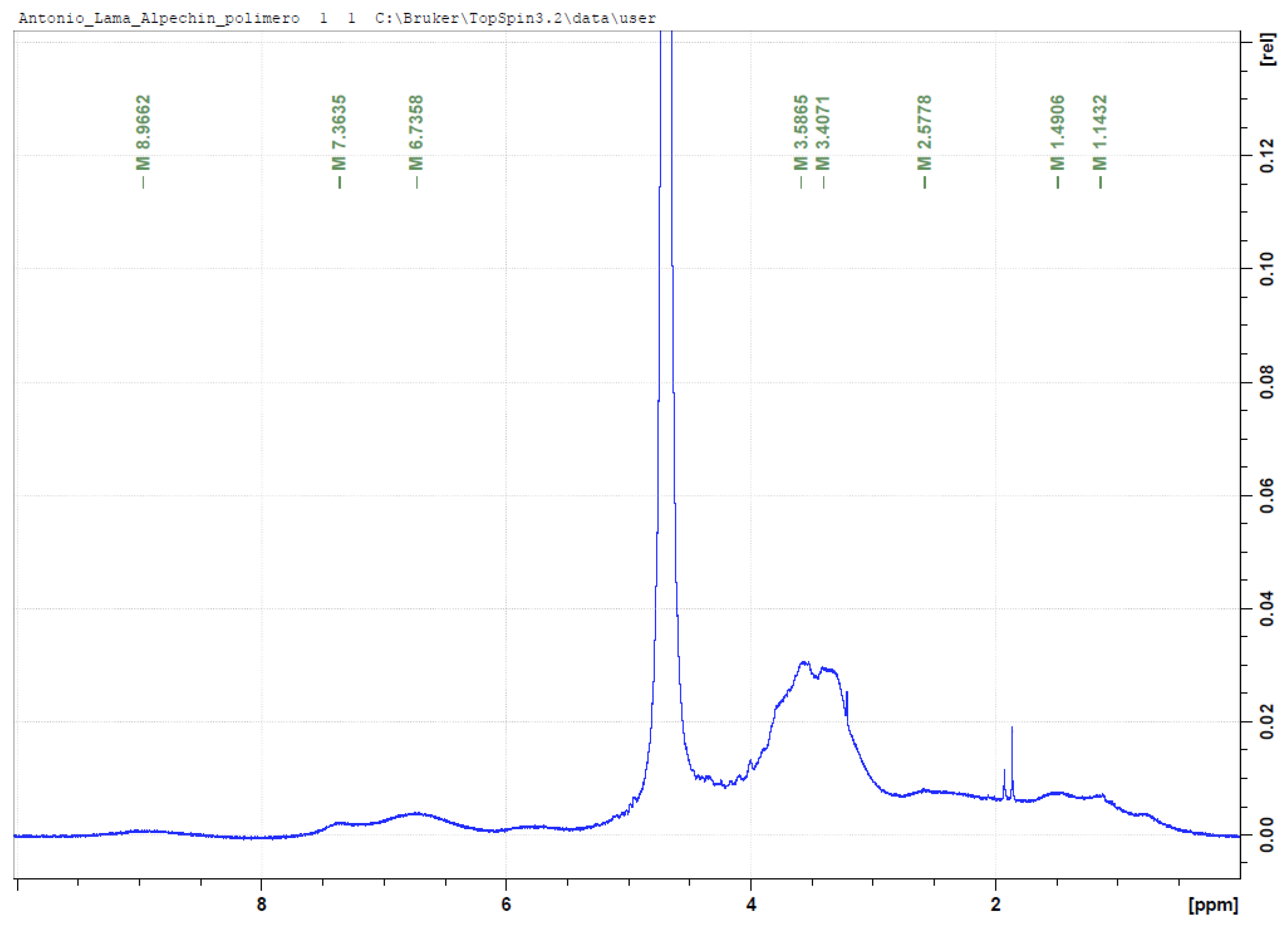

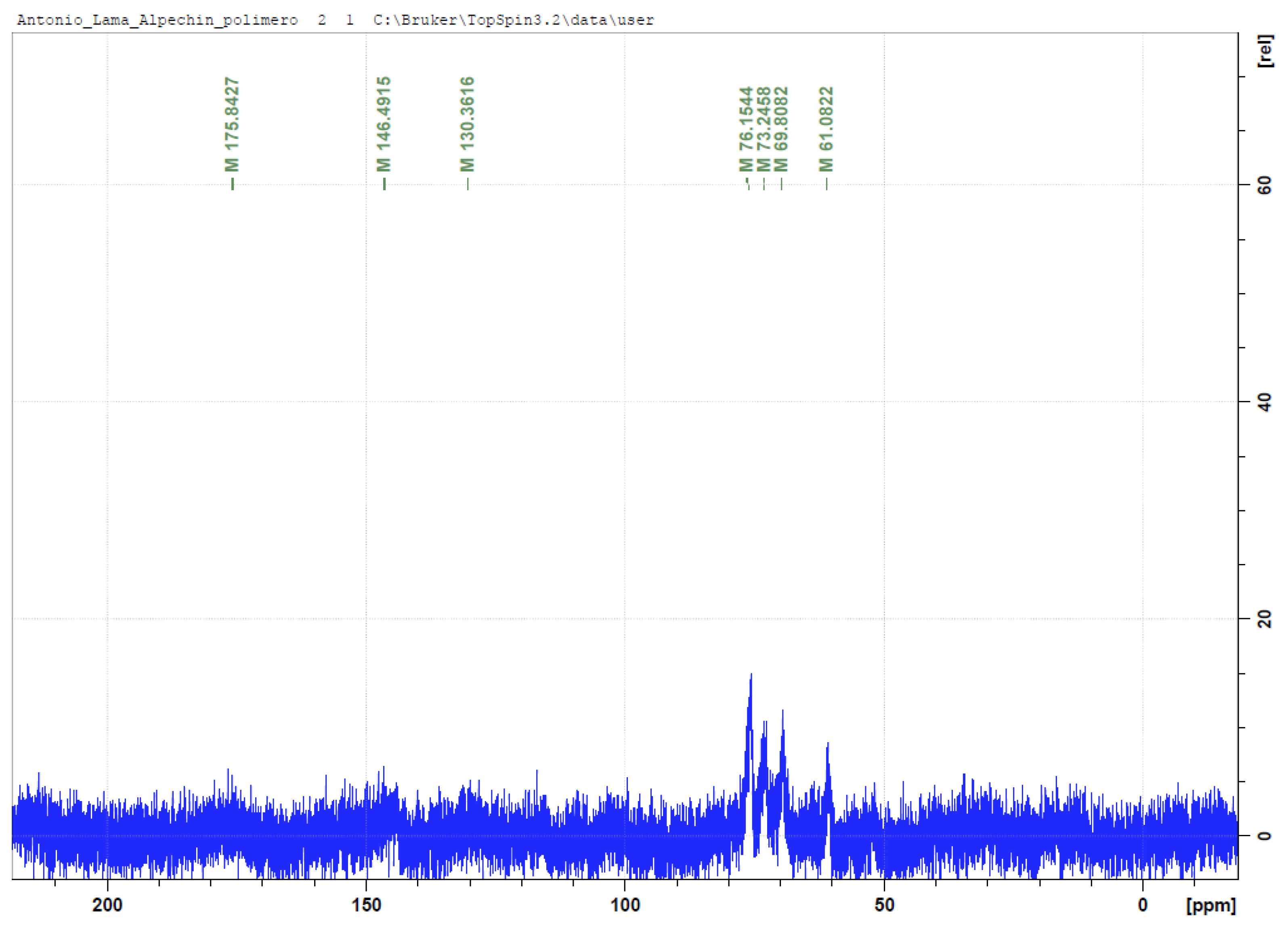

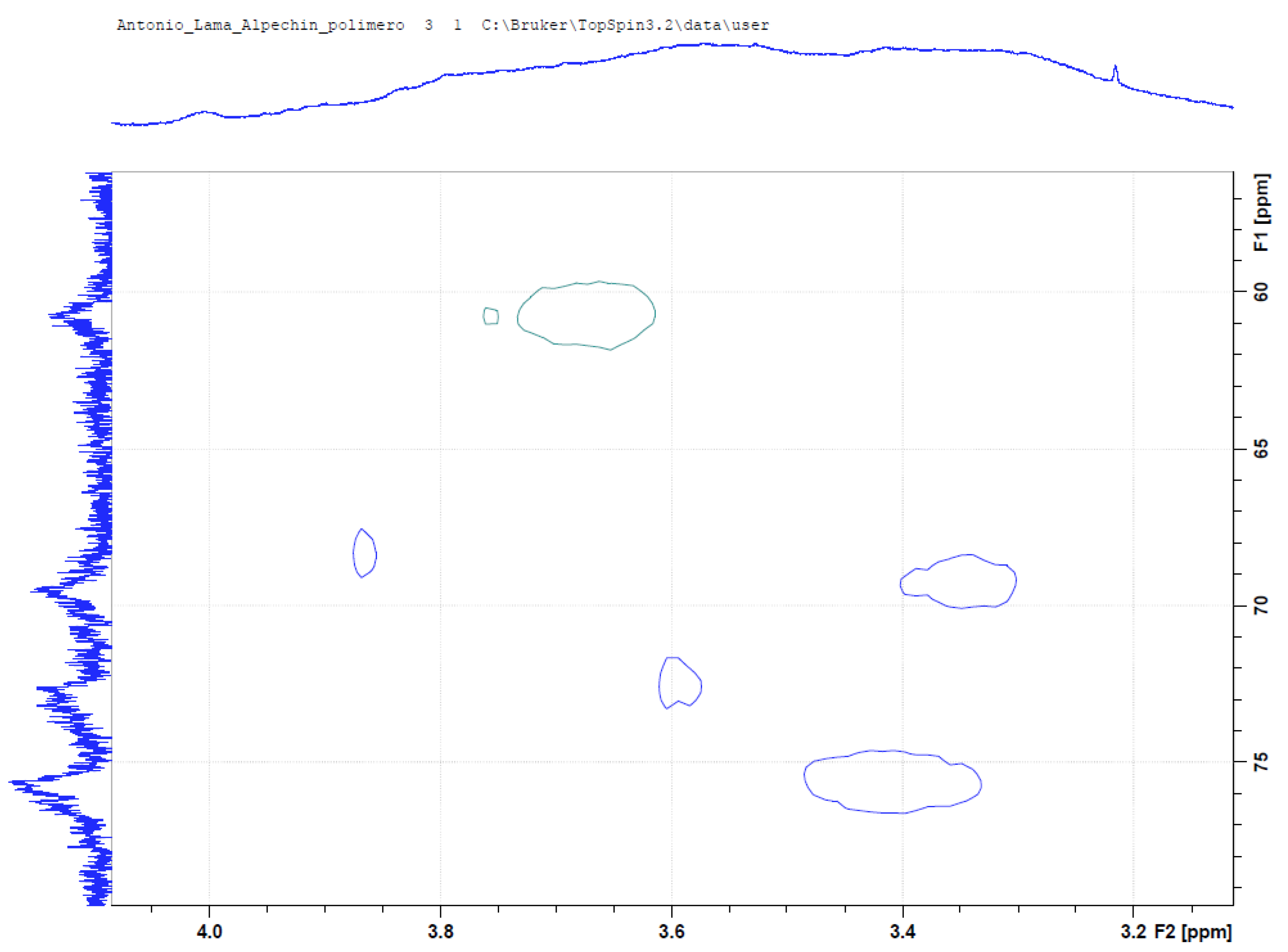

3.4. NMR Analysis of OMW-2000 XAD

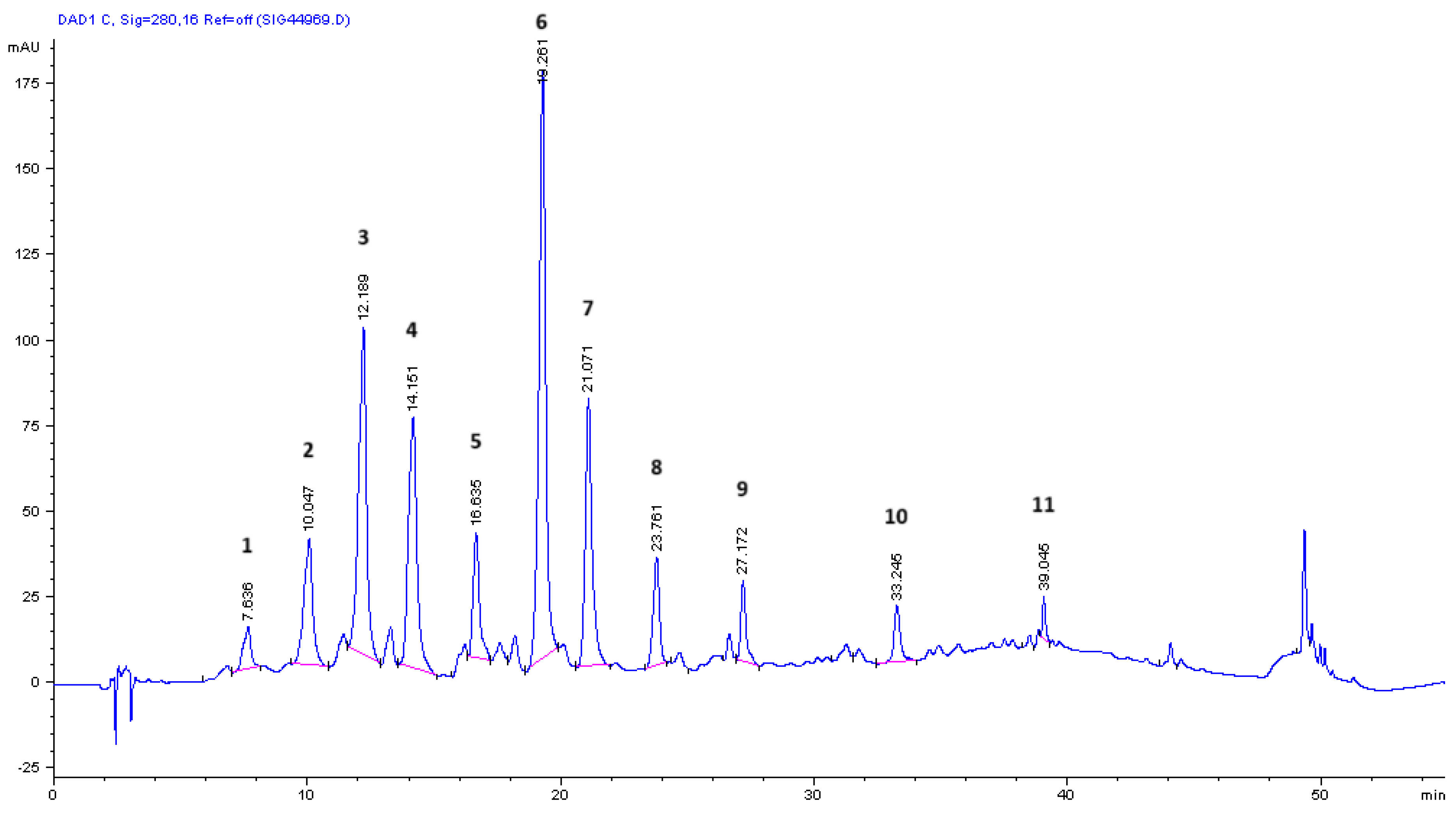

3.5. Mass Spectrometry for Qualitative Analysis of Compounds in OMW-2000 XAD Hydrolysates

3.6. Antioxidant Capacity of OMW-2000XAD

| Assay | OMW-2000XAD | Hydroxytyrosol | Caffeic acid |

|---|---|---|---|

| TEAC | 2539 ± 381 / (4976)2 | 11322 / (1.7) | 10700 / (1.9) |

| DPPH | 7013 ± 4 / (1374) | 87843 / (1.4) | 71483 / (1.3) |

| FRAP | 1038 ± 35 / (2035) | 5550 / (0.9) | Not found |

| ORAC | 3783 ± 76 / (7415) | 40405 / (6.2) | Not found |

| TPC | 5277 ± 186 / (10343) | - | - |

3.7. Anti-Proliferative Activity of OMW-2000XAD

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Azzam, M.O.J.; Hazaimeh, S.A. Olive mill wastewater treatment and valorization by extraction/concentration of hydroxytyrosol and other natural phenols. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2021, 148, 495–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, L.C.; Vilhena, A.M.; Novais, J.M.; Martins-Dias, S. Olive mill wastewater characteristics: modelling and statistical analysis. Grasas Aceites 2004, 55, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niaounakis, M.; Halvadakis, C.P. Olive-mill Waste Management - Literature Review and Patent Survey; Typothito - George Dardanos: Athens, Greece, 2004; pp. 18–34. [Google Scholar]

- Poerschmann, J.; Weiner, B.; Baskyr, I. Organic compounds in olive mill wastewater and in solutions resulting from hydrothermal carbonization of the wastewater. Chemosphere 2013, 92, 1472–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbattista, R.; Ventura, G.; Calvano, C.D.; Cataldi, T.R.I.; Losito, I. Bioactive compounds in waste by-products from olive oil production: Applications and structural characterization by mass spectrometry techniques. Foods 2021, 10, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncero, A.V.; Durán, R.M.; Constante, E.G. Componentes fenólicos de la aceituna II. Polifenoles del alpechín (Phenolic compounds in olive fruits II. Polyphenols in vegetation water). Grasas Aceites 1974, 25, 341–345. [Google Scholar]

- Schieber, A. Reactions of quinones - Mechanisms, structures, and prospects for food research. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 13051–13055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilley, A.; McHenry, M.P.; McHenry, J.A.; Solah, V.; Bayliss, K. Enzymatic browning: The role of substrates in polyphenol oxidase mediated browning. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2023, 7, 100623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Feng, J.; Tang, Y.; Wang, X.; Tang, J.; Cai, X.; Zhong, H. Research progress on the interaction of the polyphenol–protein–polysaccharide ternary systems. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2024, 11, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, M.M.; López-Linares, J.C.; Castro, E. Integrated advanced technologies for olive mill wastewater treatment: a biorefinery approach. In Advanced Technologies in Wastewater Treatment – Food Processing Industry; Basile, A., Cassano, A., Conidi, C., Eds.; Publisher: Elsevier Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2023; pp. 247–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochando-Pulido, J.M.; Vuppala, S.; García-López, A.I.; Martínez-Férez, A. A focus on anaerobic digestion and co-digestion strategies for energy recovery and digestate valorization from olive-oil mill solid and liquid by-products. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 333, 125827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Bolaños, J.; Rodríguez Gutiérrez, G.; Lama Muñoz, A.; Sánchez Moral, P. 2010. Device and method for processing olive-oil-production byproducts. ES Patent 2,374,675, 09 August.

- Amaral, C.; Lucas, M.S.; Coutinho, J.; Crespí, A.L.; do Rosário Anjos, M.; Pais, C. Microbiological and physicochemical characterization of olive mill wastewaters from a continuous olive mill in Northeastern Portugal. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 7215–7223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Jiang, M.; Yu, X.; Niu, N.; Chen, L. Application of lignin adsorbent in wastewater Treatment: A review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 302, 122116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sannino, F.; Iorio, M.; De Martino, A.; Pucci, M.; Brown, C.D.; Capasso, R. Remediation of waters contaminated with ionic herbicides by sorption on polymerin. Water Res. 2008, 42, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capasso, R.; De Martino, A. Polymerin and lignimerin, as humic acid-like sorbents from vegetable waste, for the potential remediation of waters contaminated with heavy metals, herbicides, or polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 10283–10299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panzella, L.; Napolitano, A. Natural Phenol Polymers: Recent Advances in Food and Health Applications. Antioxidants 2017, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadeniz, F.; Ahn, B.-N.; Kim, J.-A.; Seo, Y.; Jang, M.-S.; Nam, K.-H.; Kim, M.; Lee, S.-H.; Kong, C.-S. Phlorotannins suppress adipogenesis in pre-adipocytes while enhancing osteoblastogenesis in pre-osteoblasts. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2015, 38, 2172–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsirigotis-Maniecka, M.; Pawlaczyk-Graja, I.; Ziewiecki, R.; Balicki, S.; Matulová, M.; Capek, P.; Czechowski, F.; Gancarz, R. The polyphenolic-polysaccharide complex of Agrimonia eupatoria L. as an indirect thrombin inhibitor - isolation and chemical characterization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 125, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olennikov, D.N.; Chemposov, V.V.; Chirikova, N.K. Polymeric compounds of lingonberry waste: Characterization of antioxidant and hypolipidemic polysaccharides and polyphenol-polysaccharide conjugates from Vaccinium vitis-idaea press cake. Foods 2022, 11, 2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capasso, R.; De Martino, A.; Arienzo, M. Recovery and characterization of the metal polymeric organic fraction (Polymerin) from olive oil mill wastewaters. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 2846–2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capasso, R.; De Martino, A.; Pigna, M.; Pucci, M.; Sannino, F.; Violante, A. Recovery of polymerin from olive oil mill waste waters. Its potential utilization in environmental technologies and industry. La Chimica e l’Industria 2003, 85, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Capasso, R.; De Martino, A.; Cristinzio, G. Production, characterization, and effects on tomato of humic acid-like polymerin metal derivatives from olive oil mill waste waters. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 4018–4024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, E.; García-Romera, I.; Ocampo, J.A.; Carbone, V.; Mari, A.; Malorni, A.; Sannino, F.; De Martino, A.; Capasso, R. Chemical characterization and effects on Lepidium sativum of the native and bioremediated components of dry olive mil residue. Chemosphere 2007, 69, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardinali, A.; Cicco, N.; Linsalata, V.; Minervini, F.; Pati, S.; Pieralice, M.; Tursi, N.; Lattanzio, V. Biological activity of high molecular weight phenolics from olive mill wastewater. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 8585–8590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio-Senent, F.; Rodríguez-Gutiérrez, G.; Lama-Muñoz, A.; Fernández-Bolaños, J. Chemical characterization and properties of a polymeric phenolic fraction obtained from olive oil waste. Food Res. Int. 2013, 54, 2122–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allouche, N.; FKI, I.; Sayadi, S. Toward a high yield recovery of antioxidants and purified Hydroxytyrosol from olive mill wastewaters. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khemakhem, M.; Papadimitriou, V.; Sotiroudis, G.; Zoumpoulakis, P.; Arbez-Gindre, C.; Bouzouita, N.; Sotiroudis, T.G. Melanin and humic acid-like polymer complex from olive mill waste waters. Part I. Isolation and characterization. Food Chem. 2016, 203, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khemakhem, M.; Sotiroudis, G.; Mitsou, E.; Avramiotis, S.; Sotiroudis, T.G.; Bouzouita, N.; Papadimitriou, V. Melanin and humic acid-like polymer complex from olive mill waste waters. Part II. Surfactant properties and encapsulation in W/O microemulsions. J. Mol. Liq. 2016, 222, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martín, N.M.; Márquez-López, J.C.; Cerrillo, I.; Millán, F.; González-Jurado, J.A.; Fernández-Pachón, M.-S.; Pedroche, J. Production of chickpea protein hydrolysate at laboratory and pilot plant scales: Optimization using principal component analysis based on antioxidant activities. Food Chem. 2024, 437, 137707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo-Carmona, S.; Rodríguez-Arcos, R.; Guillén-Bejarano, R.; Jiménez-Araujo, A. Hydrothermal treatments enhance the solubility and antioxidant characteristics of dietary fiber from asparagus by-products. Food Bioprod. Process. 2019, 114, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lama-Muñoz, A.; Romero-García, J.M.; Cara, C.; Moya, M.; Castro, E. Low energy-demanding recovery of antioxidants and sugars from olive stones as preliminary steps in the biorefinery context. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 60, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Ou, B.; Prior, R.L. The chemistry behind antioxidant capacity assays. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 1841–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borenfreund, E.; Puerner, J.A. Toxicity determined in vitro by morphological alterations and neutral red absorption. Toxicol. Lett. 1985, 24, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Hajjouji, H.; Fakharedine, N.; Baddi, G.A.; Winterton, P.; Bailly, J.R.; Revel, J.C.; Hafidi, M. Treatment of olive mill waste-water by aerobic biodegradation: An analytical study using gel permeation chromatography, ultraviolet–visible and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 3513–3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barje, F.; El Fels, L.; El Hajjouji, H.; Amir, S.; Winterton, P.; Hafidi, M. Molecular behaviour of humic acid-like substances during co-composting of olive mill waste and the organic part of municipal solid waste. Int. Biodeter. Biodegr. 2012, 74, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonitati, J.; Elliott, W.B.; Miles, P.G. Interference by carbohydrate and other substances in the estimation of protein with the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Anal. Biochem. 1969, 31, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadour, M.; Laroche, C.; Pierre, G.; Delattre, C.; Moulti-Mati, F.; Michaud, P. Structural characterization and biological activities of polysaccharides from olive mill wastewater. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2015, 177, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafidi, M.; Amir, S.; Revel, J.-C. Structural characterization of olive mill waste-water after aerobic digestion using elemental analysis, FTIR and 13C NMR. Process Biochem. 2005, 40, 2615–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Haimer, Y.; Rich, A.; Sisouane, M.; Siniti, M.; El Krati, M.; Tahiri, S.; Mountadar, M. Olive oil mill wastewater treatment by a combined process of freezing, sweating and thawing. Desal. Water Treat. 2022, 257, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlaczyk-Graja, I. Polyphenolic-polysaccharide conjugates from flowers and fruits of single-seeded hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna Jacq.): Chemical profiles and mechanisms of anticoagulant activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 116, 869–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Cabrera, M.; Domínguez-Vidal, A.; Ayora-Cañada, M.J. Hyperspectral FTIR imaging of olive fruit for understanding ripening processes. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2018, 145, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Pham, L.B.; Adhikari, B. Complexation and conjugation between phenolic compounds and proteins: mechanisms, characterisation and applications as novel encapsulants. Sustainable Food Technol. 2024, 2, 1206–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeb, H.A.; Eichhorn, J.; Harley, S.; Robson, A.J.; Martocq, L.; Nicholson, S.J.; Ashton, M.D.; Abdelmohsen, H.A.M.; Pelit, E.; Baldock, S.J.; Halcovitch, N.R.; Robinson, B.J.; Schacher, F.H.; Chechik, V.; Vercruysse, K.; Taylor, A.M.; Hardy, J.G. Phenolic Polymers as Model Melanins. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2023, 2300025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.-Y.-Y.; Wang, J.-Q. Yin, J.-Y.; Nie, S.-P.; Xie, M.-Y. A review of NMR analysis in polysaccharide structure and conformation: Progress, challenge and perspective. Food Res. Int. 2021, 143, 110290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, R.S.P.; Muralikrishna, G. Structural characteristics of water-soluble feruloyl arabinoxylans from rice (Oryza sativa) and ragi (finger millet, Eleusine coracana): Variations upon malting. Food Chem. 2007, 104, 1160–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, M.; Dufour, C.; Mora, N.; Dangles, O. Antioxidant activity of olive phenols: mechanistic investigation and characterization of oxidation products by mass spectrometry. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005, 3, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Antuono, I.; Kontogianni, V.G.; Kotsiou, K.; Linsalata, V.; Logrieco, A.F.; Tasioula-Margari, M.; Cardinali, A. Polyphenolic characterization of olive mill wastewaters, coming from Italian and Greek olive cultivars, after membrane technology. Food Res. Int. 2014, 65, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capriotti, A.L.; Cavaliere, C.; Crescenzi, C.; Foglia, P.; Nescatelli, R.; Samperi, R.; Laganà, A. Comparison of extraction methods for the identification and quantification of polyphenols in virgin olive oil by ultra-HPLC-QToF mass spectrometry. Food Chem. 2014, 158, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.Z.; Fristedt, R.; Landberg, R.; Kamal-Eldin, A. Soluble and hydrolyzable phenolic compounds in date fruits (Phoenix dactylifera L.) by UPLC-QTOF-MS/MS and UPLC-DAD. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 132, 106354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kıvrak, Ş.; Kıvrak, İ. Ultrasonic-assisted extraction method of phenolic compounds in Extra-Virgin Olive Oils (EVOOs) by Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry (UPLC–MS/MS). Sep. Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoletto, I.; Salas, P.G.; Valli, E.; Bendini, A.; Ferioli, F.; Pasini, F.; Villasclaras, S.S.; García-Ruiz, R.; Toschi, T.G. HPLC-MS/MS phenolic characterization of olive pomace extracts obtained using an innovative mechanical approach. Foods 2024, 13, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, O.A.; Kerebba, N.; Horn, S.; Maboeta, M.S.; Pieters, R. Comparative phytochemistry using UPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS phenolic compounds profile of the water and aqueous ethanol extracts of Tagetes minuta and their cytotoxicity. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2024, 164, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongiorno, D.; Di Stefano, V.; Indelicato, S.; Avellone, G.; Ceraulo, L. Bio-phenols determination in olive oils: Recent mass spectrometry approaches. Mass Spec. Rev. 2023, 42, 1462–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattonai, M.; Vinci, A.; Degano, I.; Ribechini, E.; Franceschi, M.; Modugno, F. Olive mill wastewaters: quantitation of the phenolic content and profiling of elenolic acid derivatives using HPLC-DAD and HPLC/MS2 with an embedded polar group stationary phase. Nat. Prod. Res. 2019, 33, 3171–3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Mundo, M.L.; Escobedo-Crisantes, V.M.; Mendoza-Arvizu, S.; Jaramillo-Flores, M.E. Polymerization of phenolic compounds by polyphenol oxidase from bell pepper with increase in their antioxidant capacity. CYTA - J. Food 2016, 14, 594–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, J.A.; Fernández-Jalao, I.; Siles-Sánchez, M.N.; Santoyo, S.; Jaime, L. Implication of the polymeric phenolic fraction and matrix effect on the antioxidant activity, bioaccessibility, and bioavailability of grape stem extracts. Molecules 2023, 28, 2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisuthisakul, P. Antioxidant potential and phenolic constituents of mango seed kernel from various extraction methods. Kasetsart J. (Nat. Sci.) 2009, 43, 290–297. [Google Scholar]

- Bermúdez-Oria, A.; Castejón, M.L.; Rubio-Senent, F.; Fernández-Prior, Á.; Rodríguez-Gutiérrez, G.; Fernández-Bolaños, J. Isolation and structural determination of cis- and trans-p-coumaroyl-secologanoside (comselogoside) from olive oil waste (alperujo). Photoisomerization with ultraviolet irradiation and antioxidant activities. Food Chem. 2024, 432, 140724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Senent, F.; Bermúdez-Oria, A.; Rodríguez-Gutiérrez, G.; Lama-Muñoz, A.; Fernández-Bolaños, J. Structural and antioxidant properties of hydroxytyrosol-pectin conjugates: Comparative analysis of adsorption and free radical methods and their impact on in vitro gastrointestinal process. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 162, 110954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez-Oria, A.; Rodríguez-Gutiérrez, G.; Alaiz, M.; Vioque, J.; Girón-Calle, J.; Fernández-Bolaños, J. Pectin-rich extracts from olives inhibit proliferation of Caco-2 and THP-1 cells. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 4844–4853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Organic component | Element | % (g/100 g) |

|---|---|---|

| Phenols | 89.8 ± 0.34 | |

| Polysaccharides | 16.1 ± 0.5 | |

| Protein | 10.3 ± 0.1 | |

| C1 | 46.31 ± 0.19 | |

| N | 1.64 ± 0.01 | |

| Na2 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | |

| Mg | 0.13 ± 0.01 | |

| P | 0.03 ± 0.01 | |

| S | 0.75 ± 0.02 | |

| K | 0.73 ± 0.02 | |

| Ca | 0.34 ± 0.01 | |

| Fe | 0.03 ± 0.01 | |

| Cu | 0.03 ± 0.01 | |

| Total metals3 | 1.29 |

| Sugar | % (referred to carbohydrate content) |

g/100 g OMW-2000XAD | Amino acid | % (referred to protein content) |

g/100 g OMW-2000XAD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | 75.8 | 12.25 ± 0.111 | Cysteine (Cys) | 16.6 | 1.71 ± 0.04 |

| Arabinose | 6.8 | 1.11 ± 0.02 | Glutamic (Glu) | 12.4 | 1.27 ± 0.03 |

| Rhamnose | 5.6 | 0.91 ± 0.02 | Aspartic (Asp) | 10.9 | 1.13 ± 0.01 |

| Galactose | 5.0 | 0.76 ± 0.01 | Glycine (Gly) | 10.5 | 1.08 ± 0.02 |

| Mannose | 3.7 | 0.58 ± 0.01 | Serine (Ser) | 7.3 | 0.75 ± 0.01 |

| Xylose | 3.1 | 0.49 ± 0.01 | Tryptophan (Trp) | 6.9 | 0.71 ± 0.05 |

| Alanine (Ala) | 5.6 | 0.58 ± 0.02 | |||

| Leucine (Leu) | 5.5 | 0.57 ± 0.01 | |||

| Threonine (Thr) | 5.3 | 0.54 ± 0.03 | |||

| Arginine (Arg) | 4.4 | 0.45 ± 0.01 | |||

| Phenylalanine (Phe) | 3.9 | 0.40 ± 0.02 | |||

| Valine (Val) | 3.7 | 0.38 ± 0.01 | |||

| Isoleucine (Ile) | 2.8 | 0.28 ± 0.01 | |||

| Tyrosine (Tyr) | 1.9 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | |||

| Histidine (His) | 1.1 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | |||

| Lysine (Lys) | 0.6 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | |||

| Methionine (Met) | 0.3 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | |||

| Proline (Pro) | 0.3 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | |||

| Total | 100 | 16.1 | Total | 100 | 10.3 |

| tr (min) | [M-H]- m/z | Fragment ions m/z | UVmax (nm) | Compound | Hydrolysate 4 M NaOH | Hydrolysate 6 M HCl | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7.64 | 331.0026 (4.5) | 219.0523 (6.8) 153.0204 (100) 109.0287 (59.2) |

207, 217, 260, 294 | 1* - Unknown | + | + | - |

| 10.05 | 137.0252 (100) | - | 228, 280 | 2 - Tyrosol | + | - | [49] |

| 11.44 | 293.1230 (5.9) | 213.0778 (18.0) 137.0253 (100) |

224, 283, 311 | 12 - Unknown | - | + | [50] |

| 12.19 | 151.0412 (100) | 109.0289 (3.8) | 200, 230, 276, 306 | 3 – Vanillin | + | - | [51] |

| 13.29 | 213.0774 (44.8) | 151.0406 (100) | 207, 228, 275, 306 | 13 - Elenolic acid derivative | - | + | [5] |

| 14.15 | 179.0361 (68.1) | 135.0462 (100) | 218, 323 | 4 - Caffeic acid | + | + | [48] |

| 16.64 | 317.0292 (20.6) | 165.0200 (100) 121.0298 (38.5) |

209 | 5 - Unknown | + | + | - |

| 19.12 | 221.0388 (4.4) | 215.0927 (12.3) 187.0176 (100) 135.0463 (75.9) |

200, 281 | 14 - Unknown | - | + | - |

| 19.26 | 163.0406 (21.8) | 119.0507 (100) | 227, 310 | 6 - p-Coumaric acid | + | - | [52] |

| 20.08 | 313.0741 (11.7) | 269.0867 (45.6) 179.0358 (100) 147.0113 (13.0) |

310 | Caffeic acid (dimers C-C and C-O type) | + | - | [48] |

| 20.80 | 341.1203 (58.9) | 179.0327 (100) 135.0076 (1.5) |

218, 262, 296 | 15 – Caffeoyl hexoside | - | + | [53] |

| 21.07 | 193.0490 (54.0) | 178.0285 (91.0) 134.0379 (100) |

218, 238, 323 | 7 - t-Ferulic acid | + | - | [52] |

| 22.42 | 225.0756 (100) | - | - | 16 - Desoxyelenolic acid | - | + | [5] |

| 23.76 | 359.1110 (5.0) | 203.0354 (100) 159.0460 (84.0) |

232, 333 | 8 - Syringic acid hexoside | + | - | [54] |

| 25.58 | 491.0932 (3.5) | 397.0186 (5.3) 279.0403 (26.9) 203.0289 (37.5) 170.9856 (100) |

208, 270 | 17 – Unknown | - | + | - |

| 26.11 | 455.1347 (45.9) | 303.0822 (4.2) | - | Hydroxytyrosol [(2AH + A) – 2H] | - | + | [48] |

| 27.17 | 325.0701 (11.3) | 283.0618 (14.9) 197.0821 (22.9) 153.0928 (100) |

267 | 9 – Unknown | + | - | - |

| 27.35 | 365.1202 (4.9) | 229.1080 (100) 199.0902 (48.2) 153.0931 (92.6) 123.0802 (35.6) |

- | 18 - Dimethyl acetal of oleacein | - | + | [55] |

| 28.27 | 221.0780 (100) | 161.0246 (16.0) | 205 | 19 – Unknown | - | + | - |

| 31.82 | 411.0476 (2.4) | 329.0993 (35.6) 257.0339 (100) 189.0515 (17.2) 147.0088 (3.4) |

205, 251 | 20 – Unknown | - | + | - |

| 33.25 | 439.1962 (8.5) | 355.0806 (44.0) 325.0703 (79.5) 281.0812 (24.7) 159.0461 (100) |

229 | 10 – Unknown | + | - | - |

| 34.54 | 651.1514 (2.9) | 325.0699 (100) 281.0811 (19.5) 237.0917 (19.2) |

- | p-Coumaric acid (tetramer) | + | - | [48] |

| 35.27 | 569.0031 (4.2) | 411.1591 (10.2) 267.0866 (30.7) 235.0603 (100) 197.0599 (8.4) |

230, 316 | 21 – Unknown | - | + | - |

| 35.67 | 495.1771 (25.7) | - | - | Dihydrocaffeic acid [(2AH + A) – 2H] | + | - | [48] |

| 36.52 | 437.1101 (3.7) | 393.0810 (7.2) 301.0697 (44.2) 249.0753 (100) 225.0541 (29.9) |

226, 280 | 22 - Unknown | - | + | - |

| 36.87 | 949.6636 (2.9) | 549.1617 (100) 473.0985 (2.7) 381.0401 (4.3) 287.0343 (3.0) 257.0800 (9.3) 225.0548 (2.9) |

229, 316 | 23 – Unknown | - | + | - |

| 38.94 | 229.1034 (3.4) | 177.0521 (100) 141.0749 (10.4) 123.0090 (1.0) |

202, 291 | 24 - 3,4-Dihydroelenolic acid (demethylated) | - | + | [56] |

| 39.05 | 519.3151 (4.6) | 351.0863 (100) 295.0261 (8.4) |

230, 310 | 11 - Unknown | + | - | - |

| 40.20 | 437.1204 (6.5) | 377.0486 (2.5) 257.0807 (60.0) 213.0917 (36.3) 181.0657 (100) |

227 | 25 - Unknown | - | + | - |

| 41.13 | 494.0700 (7.8) | 473.0988 (7.8) 347.0385 (19.2) 263.0887 (100) 219.0811 (18.6) 171.0434 (15.6) 113.0862 (4.0) |

240, 280, 303 | 26 - Unknown | - | + | - |

| 42.38 | 507.0619 (23.9) | 383.0416 (10.7) 337.0721 (7.9) 249.0702 (24.3) 205.0826 (100) |

- | 27 -Unknown | - | + | - |

| 42.66 | 257.0814 (38.8) | 225.0556 (2.5) 213.0905 (3.8) 181.0659 (100) 153.0716 (8.5) |

225 | 28 - Hydroxyelenoic acid | - | + | [50] |

| 44.14 | 265.1498 (2.4) | 213.0095 (100) | 208, 231 | 29 - Xanthonic acid | - | + | [50] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).