Submitted:

28 May 2025

Posted:

28 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Overview of the Project

1.3. Current System

1.4. Proposed System

1.5. Scope of the Project

2. Methodology (Analysis and Design)

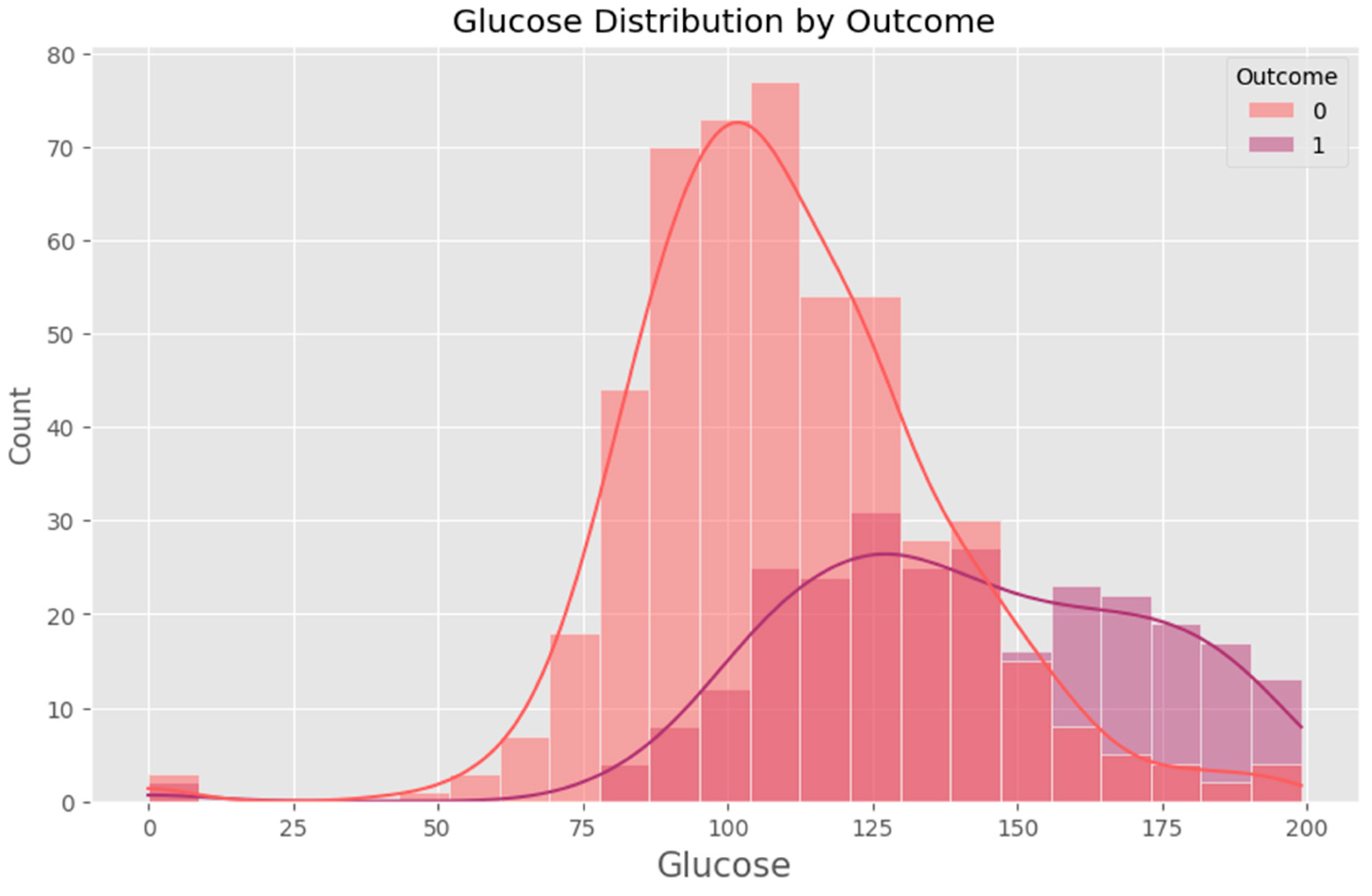

2.1. Data Collection and Preprocessing

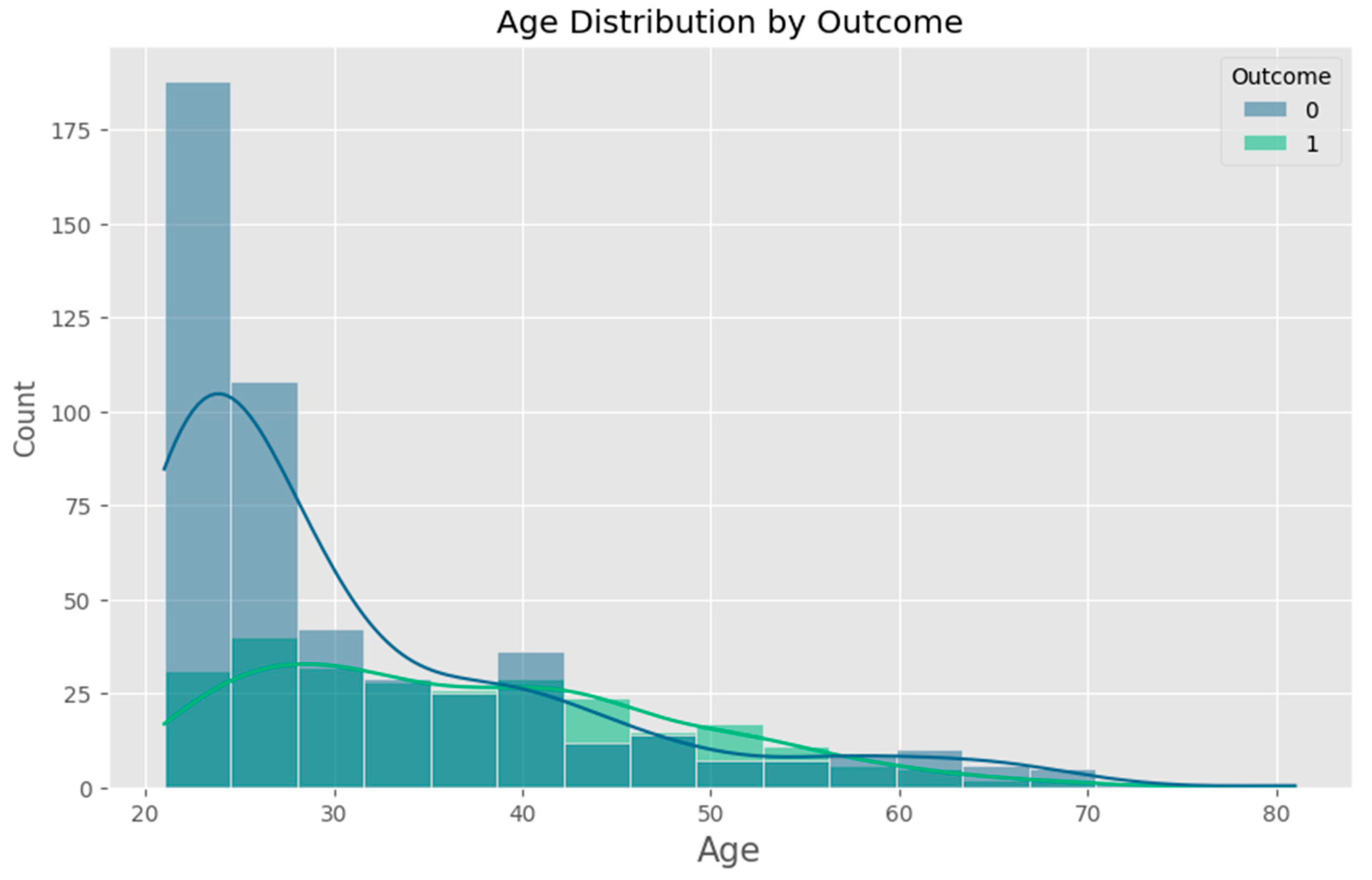

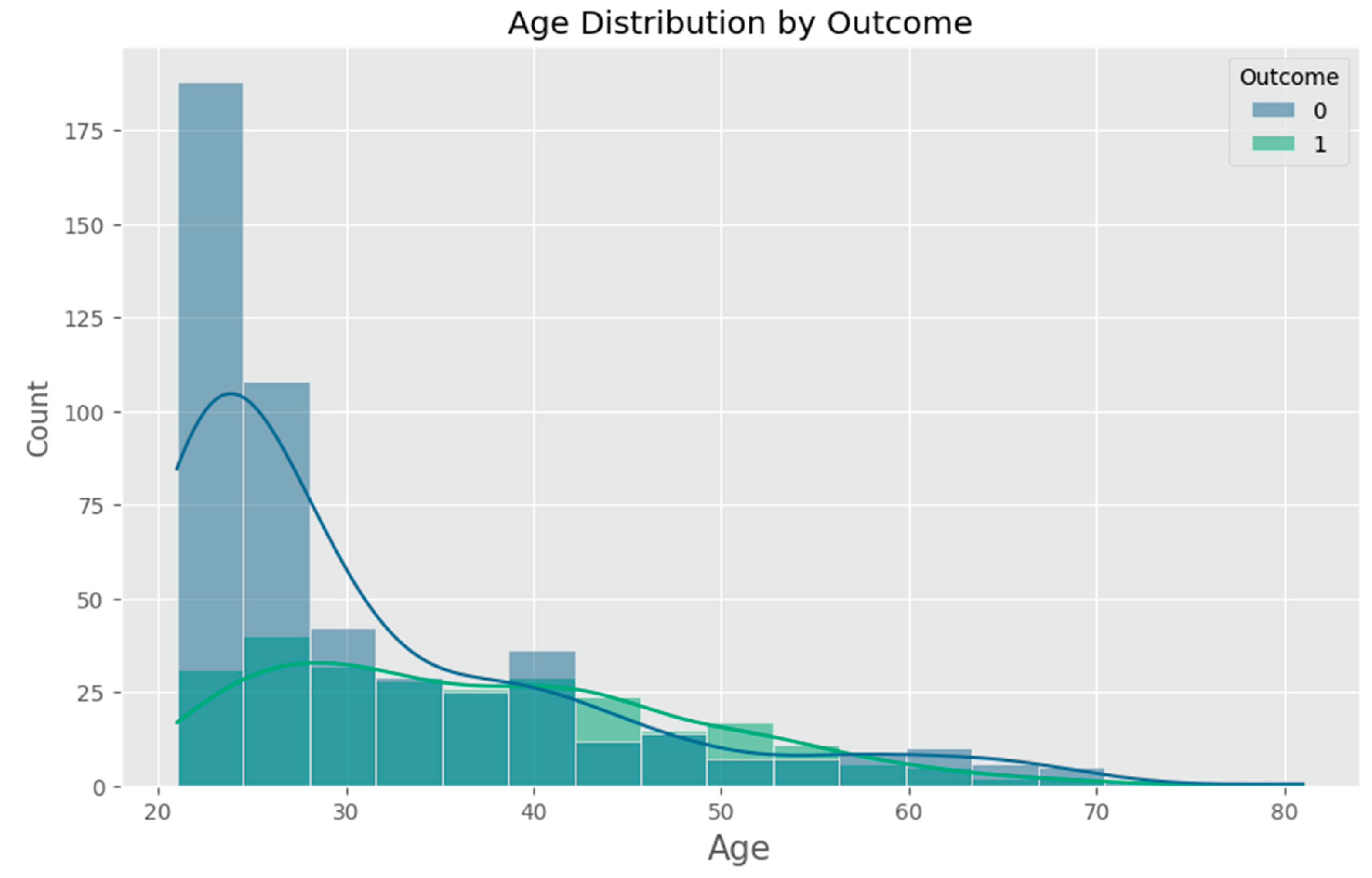

- Age (years) – An important demographic factor associated with increased risk of Type 2 diabetes.

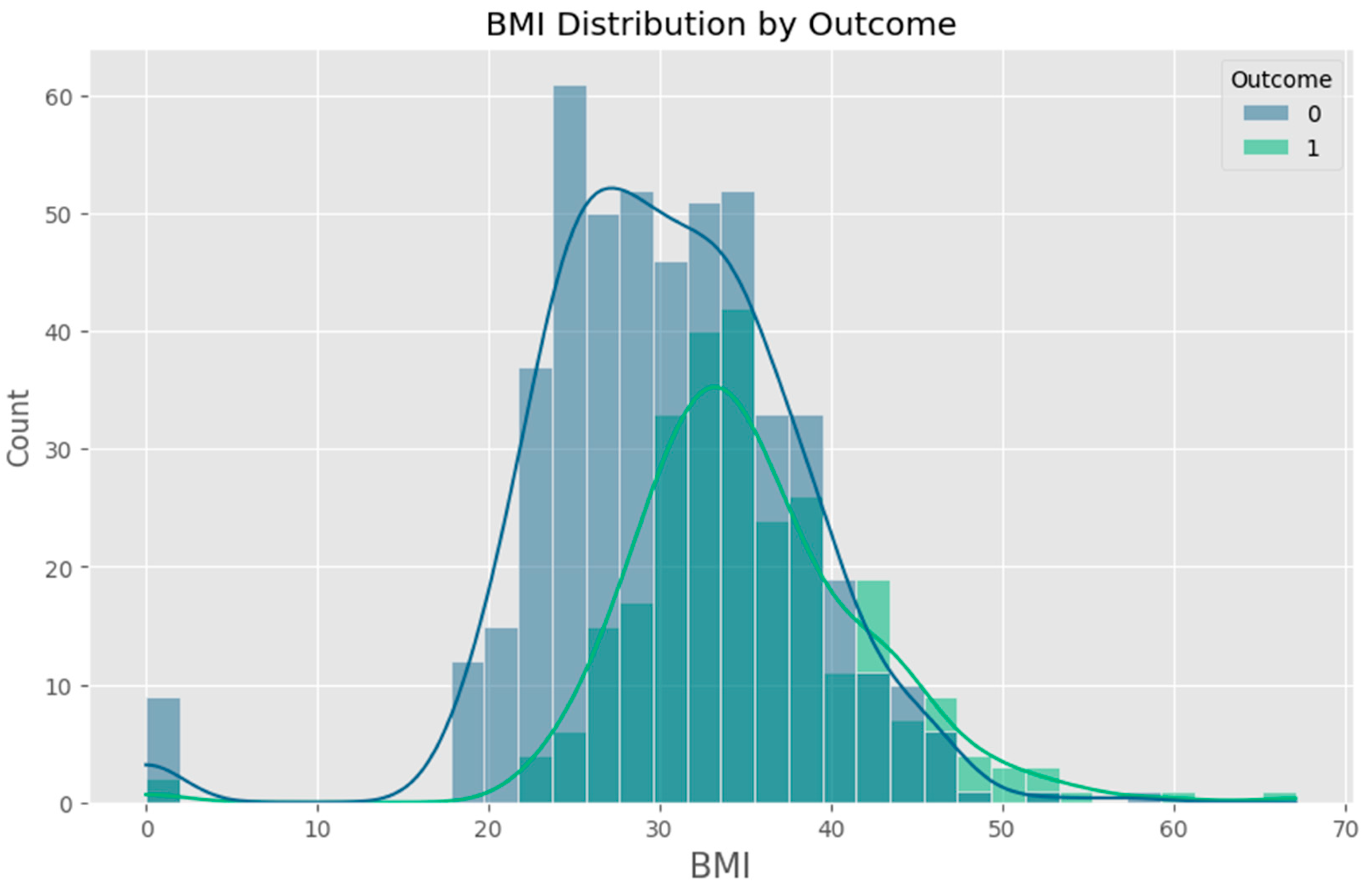

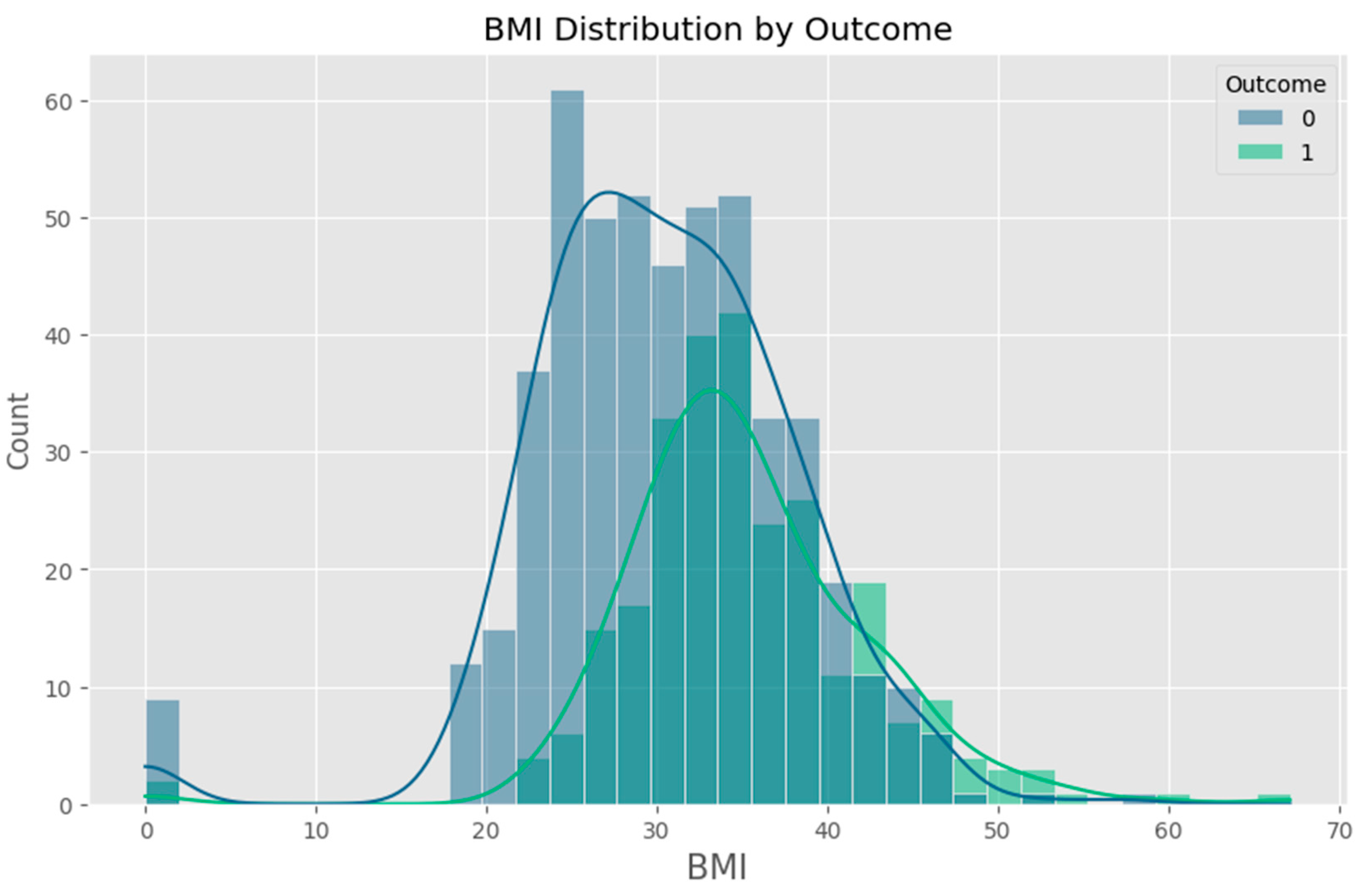

- Body Mass Index (BMI) – A widely used measure of body fat based on height and weight.

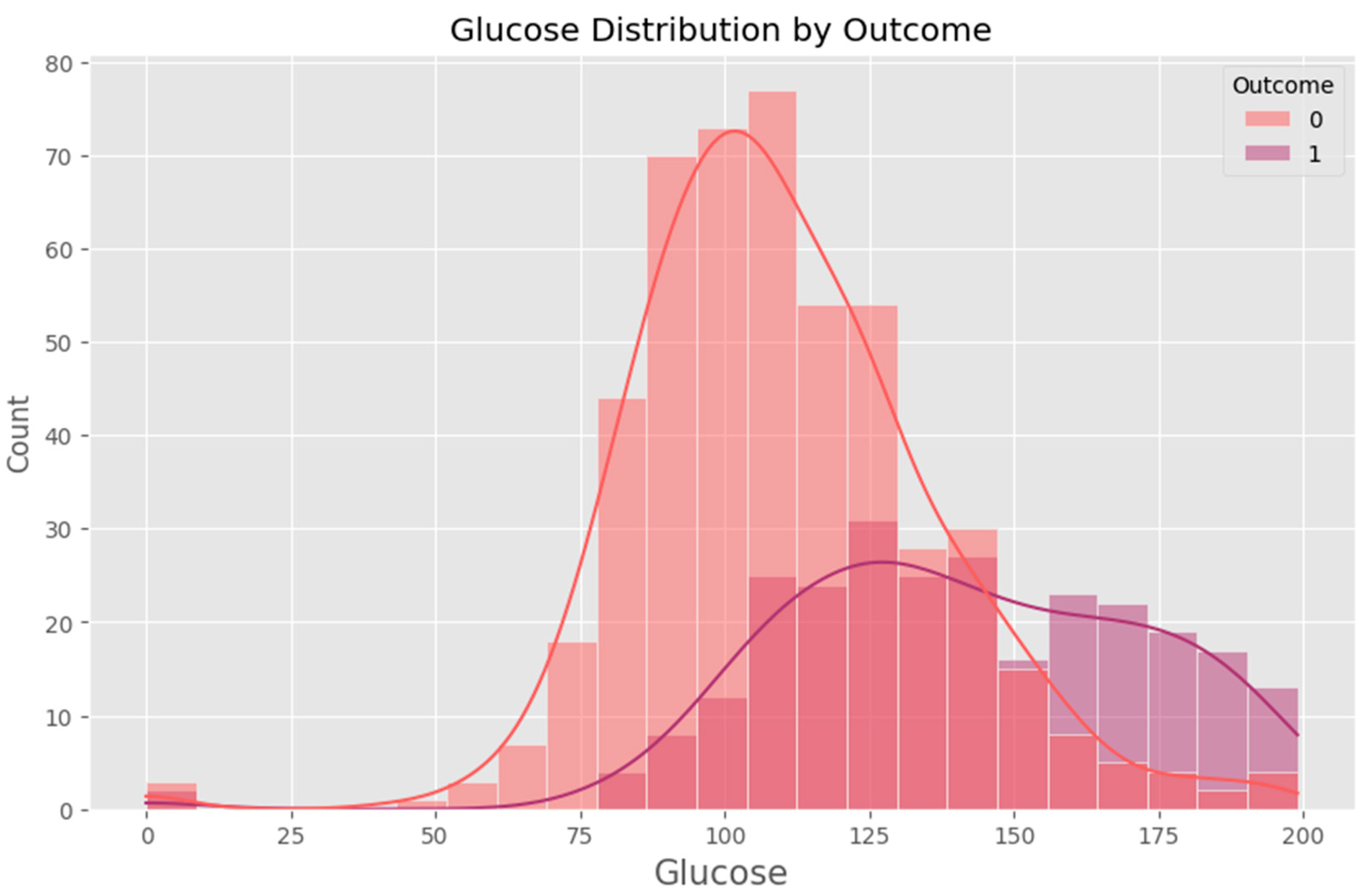

- Blood Glucose Level (mg/dL) – A critical biomarker directly linked to diabetes risk.

2.1.1. Data Cleaning

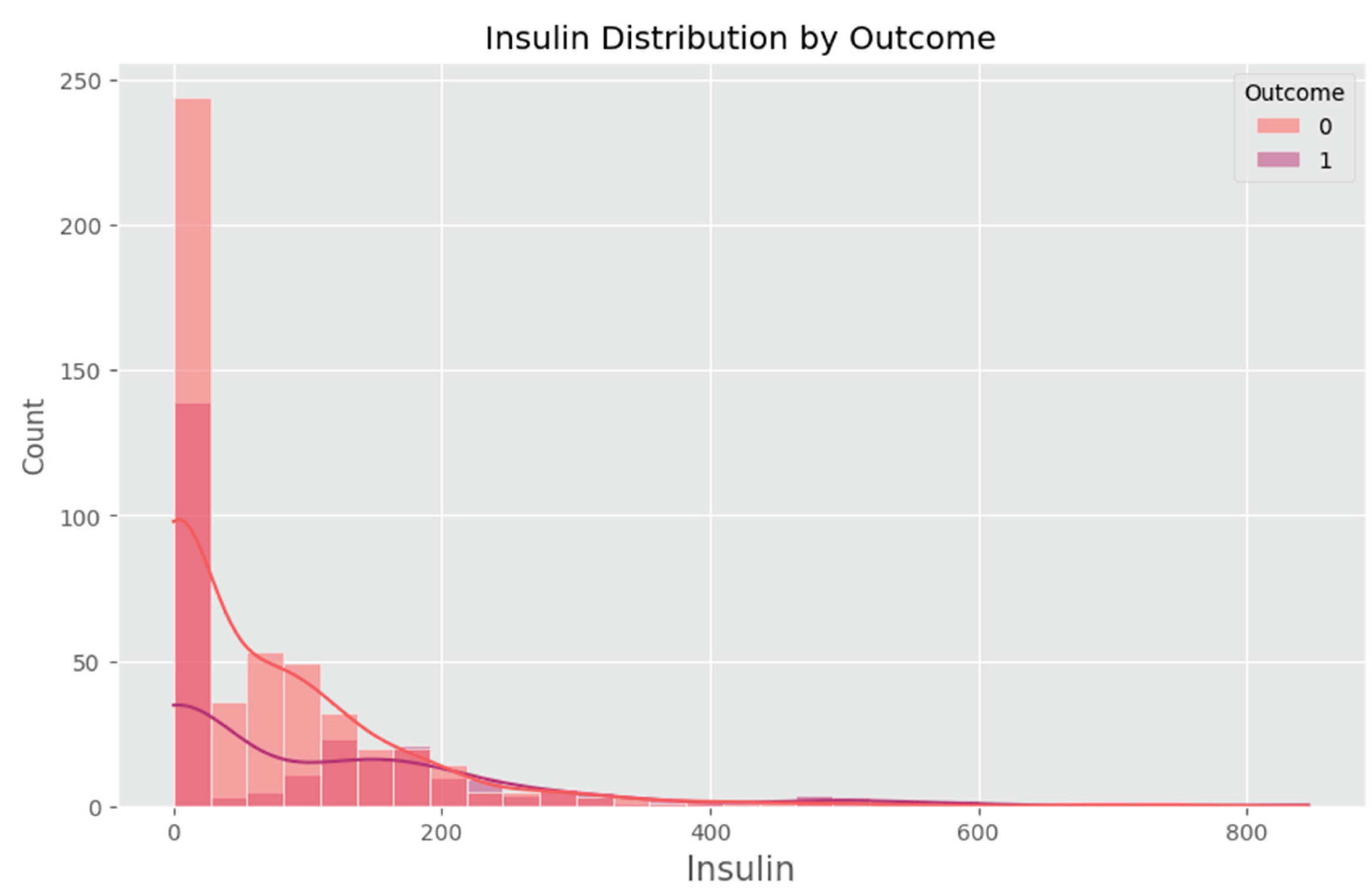

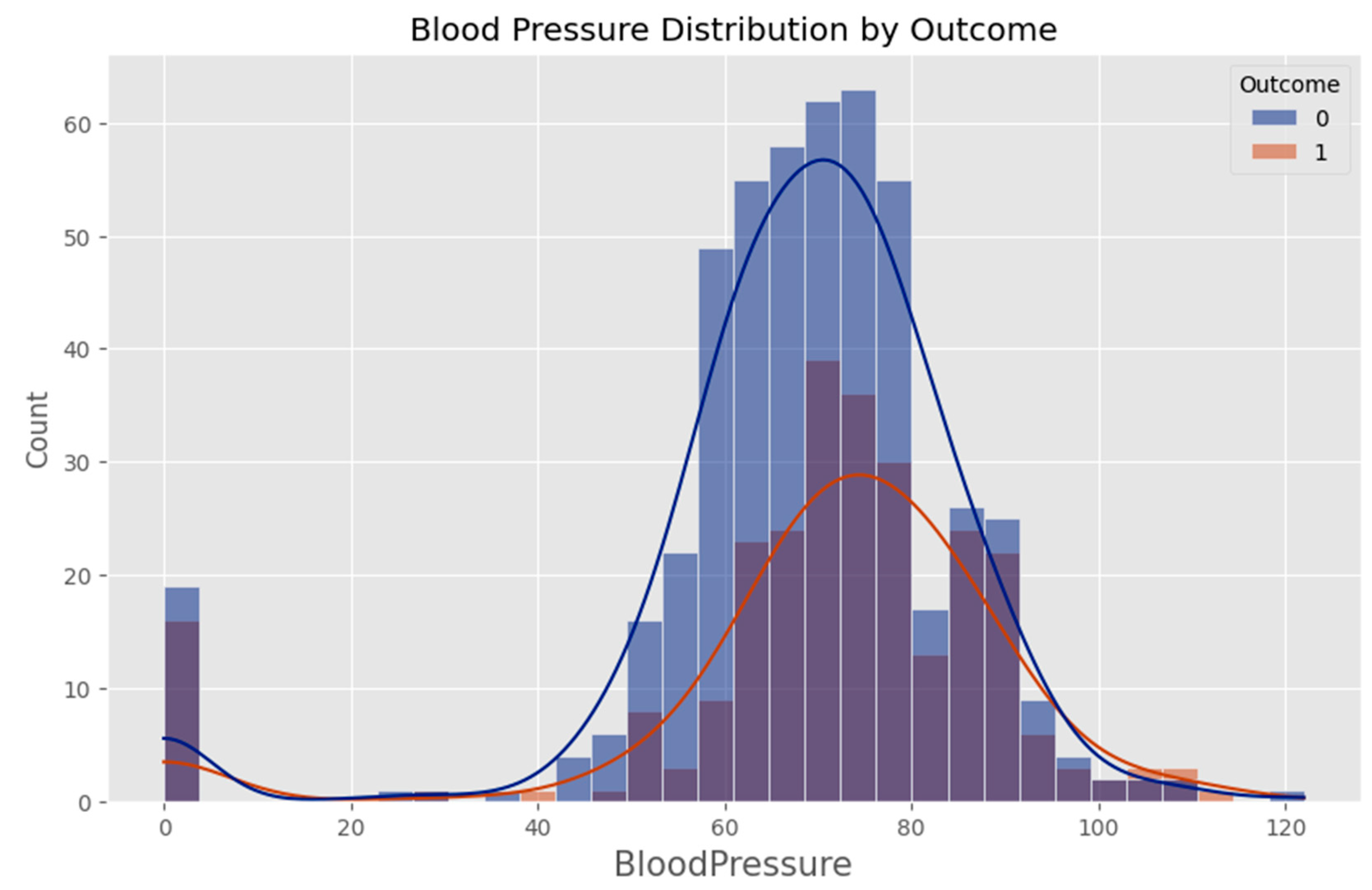

- Handling Missing Values: The dataset contains instances where critical measurements, such as BMI and glucose levels, were recorded as zero, which is not physiologically possible. These zero values were treated as missing and replaced using imputation techniques. The median value of the respective feature was used to fill missing values to minimize bias.

- Outlier Detection and Treatment: Statistical methods such as interquartile range (IQR) analysis were applied to detect and manage outliers that could skew model performance. Extreme values were capped to reasonable physiological ranges based on clinical guidelines.

2.1.2. Data Normalization

2.1.3. Data Balancing

2.1.4. Data Splitting

- Training Set (80%) – Used to train the machine learning models.

- Test Set (20%) – Used to evaluate model performance on unseen data.

2.1.5. Summary

2.2. Machine Learning Models

2.2.1. Logistic Regression

2.2.2. Random Forest

2.2.3. Support Vector Machines (SVM)

2.2.4. Model Evaluation Approach

2.2.5. Summary

2.3. Model Design and Evaluation

2.3.1. Model Design

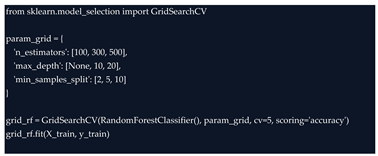

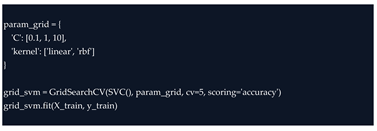

2.3.2. Model Training and Hyperparameter Tuning

- For Logistic Regression, the regularization parameter (C) was adjusted to balance the trade-off between bias and variance.

- For Random Forest, key parameters such as the number of trees (n_estimators), maximum tree depth, and minimum samples per leaf were fine-tuned to improve performance and reduce overfitting.

- For SVM, both the kernel type (linear or radial basis function) and the regularization parameter were carefully tuned to maximize classification accuracy.

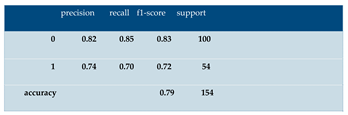

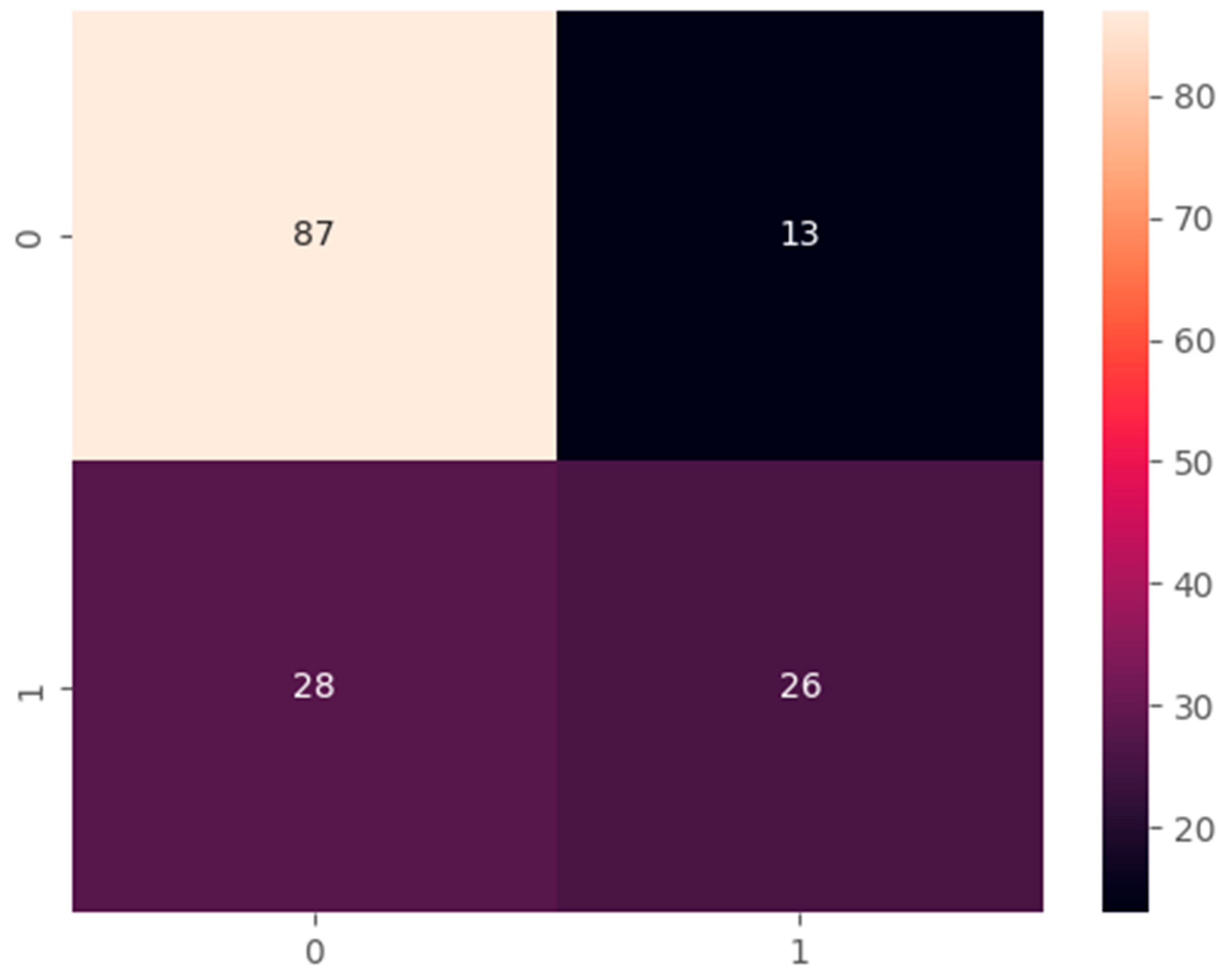

2.3.3. Model Evaluation

- Accuracy: Measures the proportion of correct predictions out of total predictions.

- Precision: Indicates how many of the predicted high-risk cases were actually high-risk.

- Recall (Sensitivity): Measures the ability of the model to correctly identify all actual high-risk individuals.

- F1-Score: Provides a balanced measure that combines both precision and recall. [18]

2.3.4. Performance Comparison and Selection

2.3.5. Summary

3. Implementation

3.1. Model Development

3.1.1. Development Environment

- Python Version: 3.8

- Virtual Environment: Created via python -m venv venv

-

Installation:

Core Libraries:

Core Libraries:- ○

Data handling: pandas (v1.x), numpy (v1.x)- ○

Visualization: matplotlib, seaborn- ○

Modeling: scikit-learn (v0.24+)- ○

Persistence: pickle

3.1.2. Data Loading and Inspection

3.1.3. Feature Selection and Label Definition

- Age

- Body Mass Index (BMI)

- Blood Glucose Level

3.1.4. Data Cleaning and Preprocessing

3.1.5. Feature Scaling

3.1.6. Train/Test Split

3.1.7. Prototype Model Training

- Logistic Regression

- K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN)

- Gaussian Naive Bayes

- Random Forest

- Support Vector Machine (SVM)

3.1.8. Model Selection and Persistence

3.1.9. Integration Readiness

3.2. Algorithm Implementation

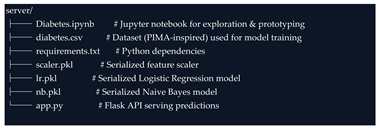

3.2.1. System Architecture

- Preprocessing module: Scales the user’s input data to match the model’s expected input distribution using the previously saved scaler.pkl object.

- Model prediction module: Loads the serialized machine learning model (lr.pkl or nb.pkl) and generates a risk prediction.

- REST API interface: Exposes endpoints for the front-end application (or AI chatbot) to send user inputs and receive prediction results. [20]

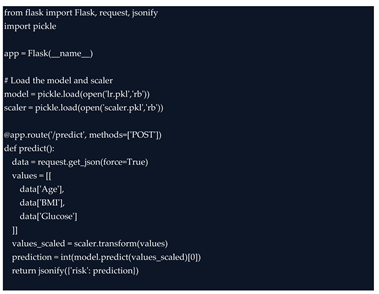

3.2.2. Flask API Structure

3.2.3. Model Integration

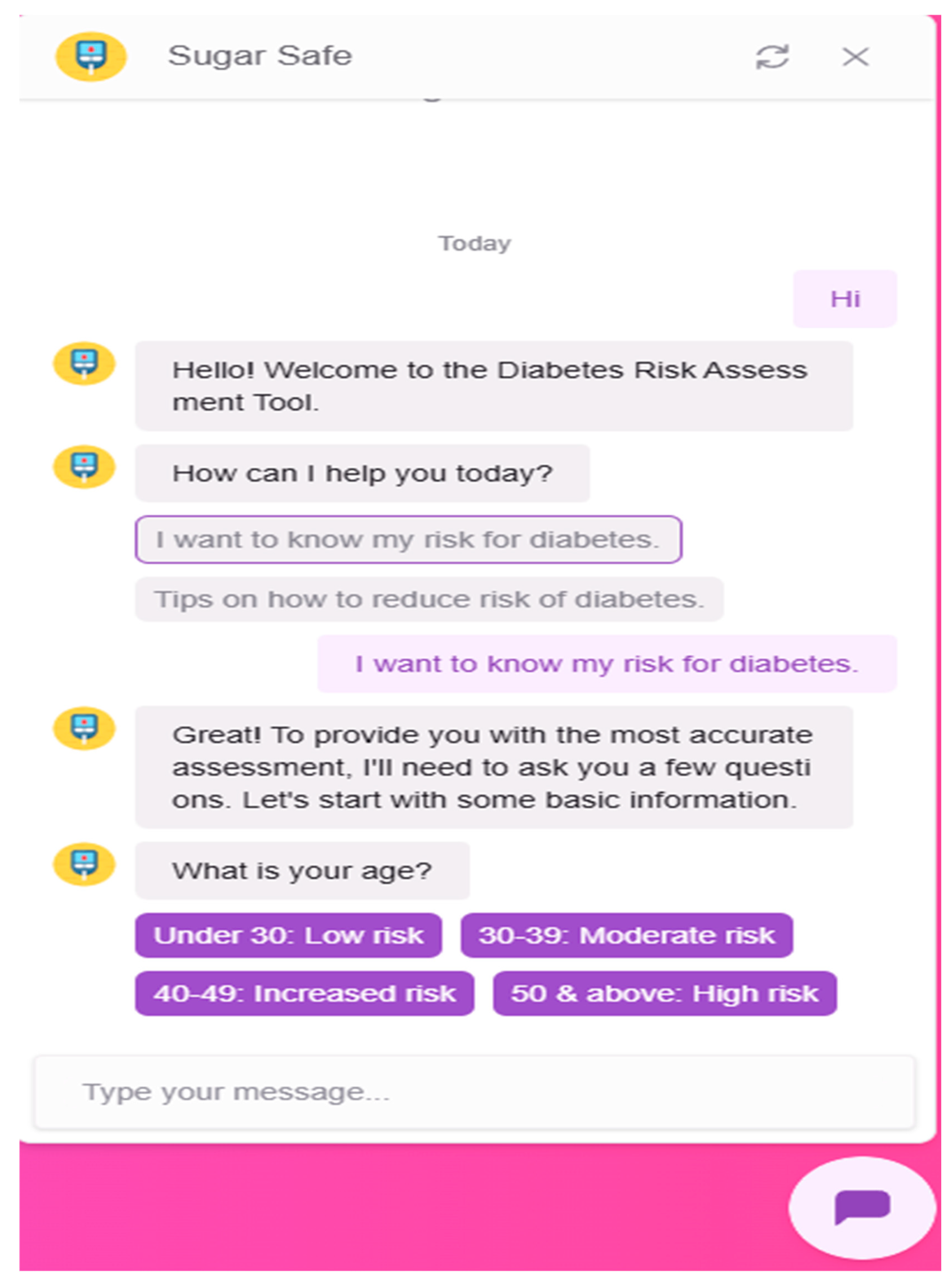

3.2.4. Chatbot Integration

- Greet users and explain the purpose of the system

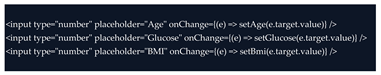

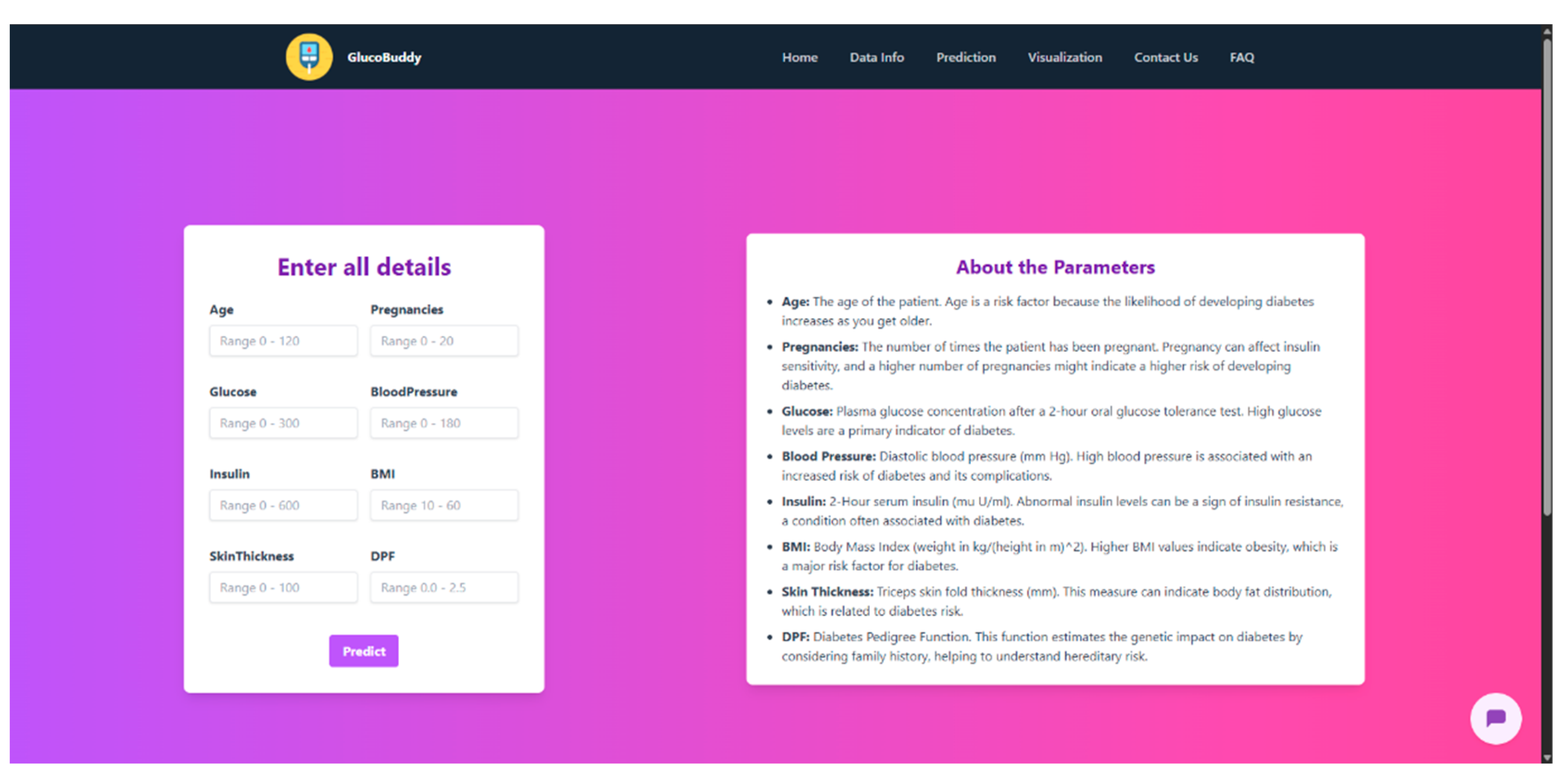

- Ask for user inputs (age, BMI, glucose level)

- Pass collected values to the Flask backend

- Receive the risk prediction and deliver it in conversational language

- Offer general advice about diabetes prevention and recommend seeking medical consultation if risk is high

3.3. Training and Tuning of Models

3.3.1. Training Process

- Logistic Regression

- K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN)

- Naive Bayes (GaussianNB)

- Random Forest

- Support Vector Machine (SVM)

3.3.2. Hyperparameter Tuning

- Random Forest

- SVM

- Logistic Regression

3.3.3. Cross-Validation

3.3.4. Performance Evaluation

- Accuracy – overall correctness of predictions

- Precision – ability to avoid false positives

- Recall (Sensitivity) – ability to catch all actual positives

- F1-score – harmonic mean of precision and recall

- ROC-AUC – the area under the ROC curve to assess overall classification power

3.3.5. Model Selection

3.3.6. Summary

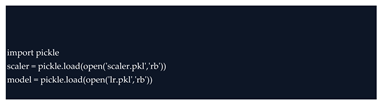

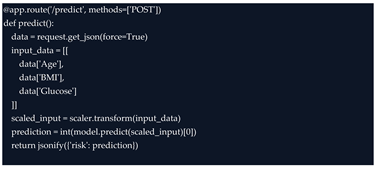

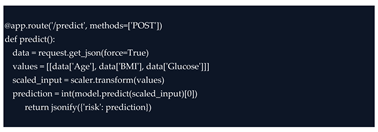

3.4. Model Integration

3.4.1. Loading the Model and Scaler

3.4.2. Creating the Prediction Endpoint

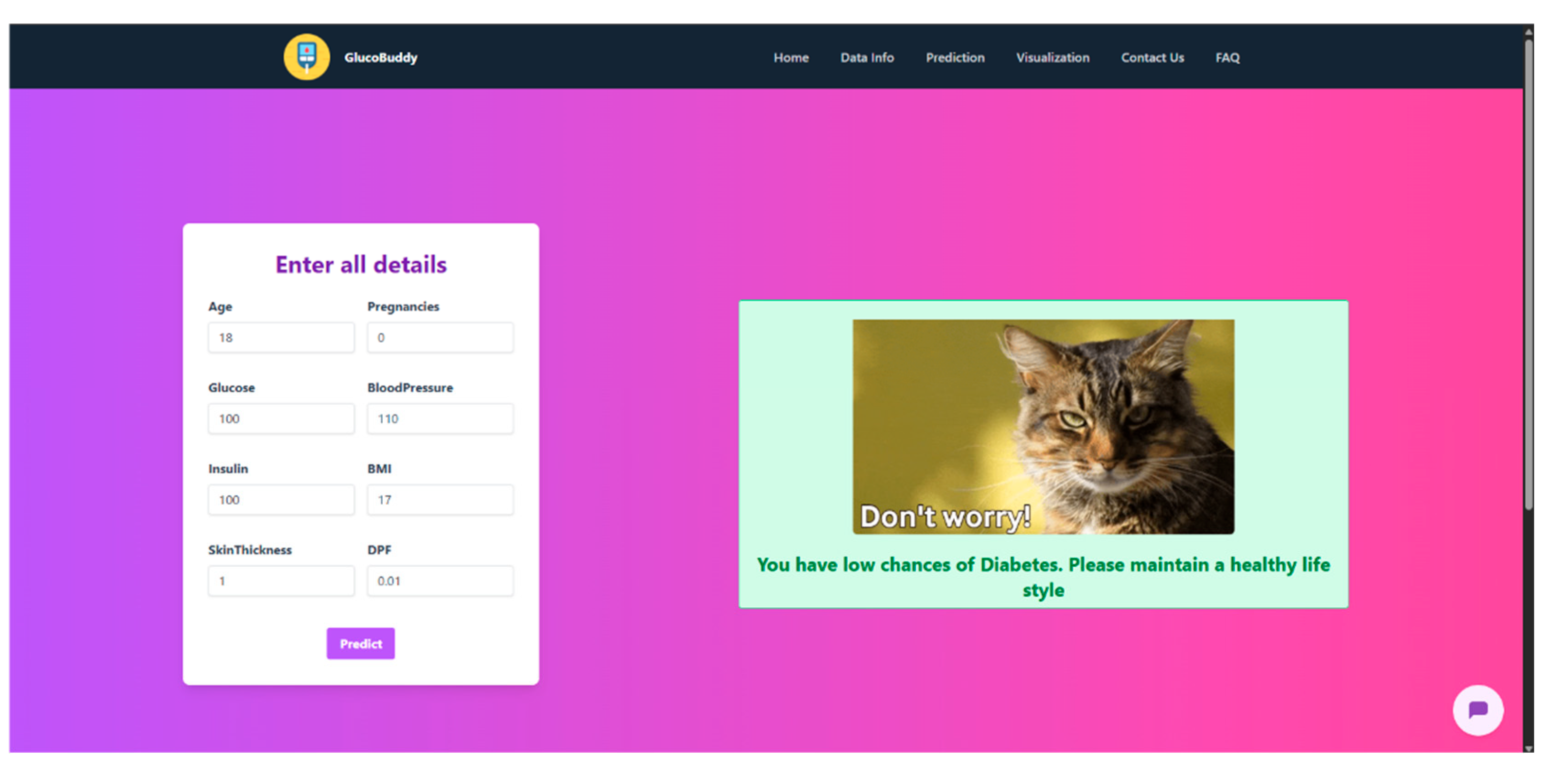

- Accepts raw JSON input from the frontend

- Applies the trained StandardScaler to normalize the data

- Uses the logistic regression model to classify the input as either 0 (low risk) or 1 (high risk)

- Returns the prediction in a user-friendly JSON format

3.4.3. Compatibility with Front-End Interfaces

- A web interface (e.g., React or basic HTML form)

- A mobile app

- An AI chatbot interface (e.g., Dialogflow, Rasa, or OpenAI-powered bot)

3.4.4. Scalability and Flexibility

3.4.5. Summary

4. Testing and Deployment

4.1. Testing Requirements

4.1.1. Model Testing

4.1.2. API Testing

- Sending valid JSON payloads and verifying correct predictions were returned.

- Testing with invalid or missing input fields to ensure appropriate error handling.

- Ensuring that the scaler was applied correctly and consistently.

- Verifying that the response structure matched frontend expectations.

4.1.3. Usability and Integration Testing

4.1.4. Testing Requirements Summary

- Accuracy of predictions (ML model)

- Stability across data splits (cross-validation)

- Robustness of the backend to unexpected inputs

- Responsiveness under normal usage

- Extendability for chatbot or mobile integrations

4.2. Performance Evaluation of Models

4.2.1. Evaluation Metrics Overview

- Accuracy measures the proportion of total correct predictions.

- Precision indicates how many of the predicted high-risk cases were truly high-risk.

- Recall (or Sensitivity) measures how well the model identifies actual high-risk individuals.

- F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, balancing false positives and false negatives.

- ROC-AUC (Receiver Operating Characteristic – Area Under Curve) reflects the model’s ability to distinguish between the two classes across all thresholds.

4.2.2. Model Performance Results

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | ROC-AUC |

| Logistic Regression | 78.6% | 79.3% | 76.2% | 77.7% | 84.1% |

| Naive Bayes | 76.2% | 74.1% | 77.4% | 75.7% | 82.3% |

| K-Nearest Neighbors | 74.1% | 72.5% | 73.0% | 72.7% | 78.9% |

| Random Forest | 81.0% | 80.6% | 79.5% | 80.0% | 85.4% |

| SVM (Linear) | 79.4% | 77.8% | 78.1% | 77.9% | 83.6% |

4.2.3. Analysis and Comparison

- Fast prediction time

- Low computational resource needs

- High interpretability (important in healthcare)

4.2.4. Final Model Selection Justification

4.3. Deployment Strategy

4.3.1. Local Deployment Using Flask

- The serialized model (lr.pkl) and scaler (scaler.pkl) were loaded at startup.

- The Flask application (app.py) was launched using: python app.py

- The server ran on http://127.0.0.1:5000, making it accessible to local clients, test tools like Postman, and any frontend component under development

4.3.2. Backend and Frontend Separation

- A web application

- A mobile app

- An AI-powered chatbot

- Desktop software

4.3.3. Data Privacy and Security

4.3.4. Future Deployment Scenarios

- Cloud platforms such as Heroku, AWS, or Google Cloud

- Docker containers for lightweight, portable deployment

- Edge devices for offline use in remote clinics

4.3.5. Summary

4.4. Scalability and Efficiency

4.4.1. System Scalability

- New machine learning models can be trained and swapped in by updating the .pkl file.

- Additional endpoints can be added for more features (e.g., lifestyle tracking, symptom logging).

- Multiple instances of the Flask server can be deployed in parallel behind a load balancer for high-traffic environments.

4.4.2. Chatbot and API Expansion

- Web browsers

- Mobile apps

- Messaging platforms (e.g., WhatsApp, Telegram)

4.4.3. Runtime Efficiency

4.4.4. Future Enhancements

- Support for multiple languages in the chatbot

- User authentication and personalized risk tracking

- Integration with wearable devices for continuous monitoring

- Real-time data dashboards for healthcare providers

4.4.5. Summary

5. Conclusion and Future Works

5.1. Summary of Results

5.2. Limitations of the Study

5.2.1. Limited Dataset Diversity

5.2.2. Small Feature Set

5.2.3. Prototype-Level Chatbot Integration

5.2.4. No Real-World User Testing

5.2.5. No Formal Privacy or Security Compliance

5.2.6. Static Risk Prediction

5.3. Future Research Directions

5.3.1. Expanding the Dataset

5.3.2. Adding More Features

- Blood pressure

- Cholesterol levels

- Family history of diabetes

- Physical activity levels

- Dietary habits

- Blood insulin levels

- Including a broader range of features can result in more nuanced and accurate risk assessments, especially for borderline cases.

5.3.3. Full Chatbot Integration

- Designing multi-turn conversations for guided health assessments

- Supporting multiple languages to reach broader user groups

- Creating a visual or voice-based interface for accessibility

5.3.4. Cloud Deployment and Mobile App

- Mobile apps (Android/iOS)

- Web platforms

- Embedded systems (e.g., clinic kiosks or wearable devices)

5.3.5. Continuous Risk Monitoring

5.3.6. Compliance with Privacy and Medical Standards

Acknowledgments

Appendix A

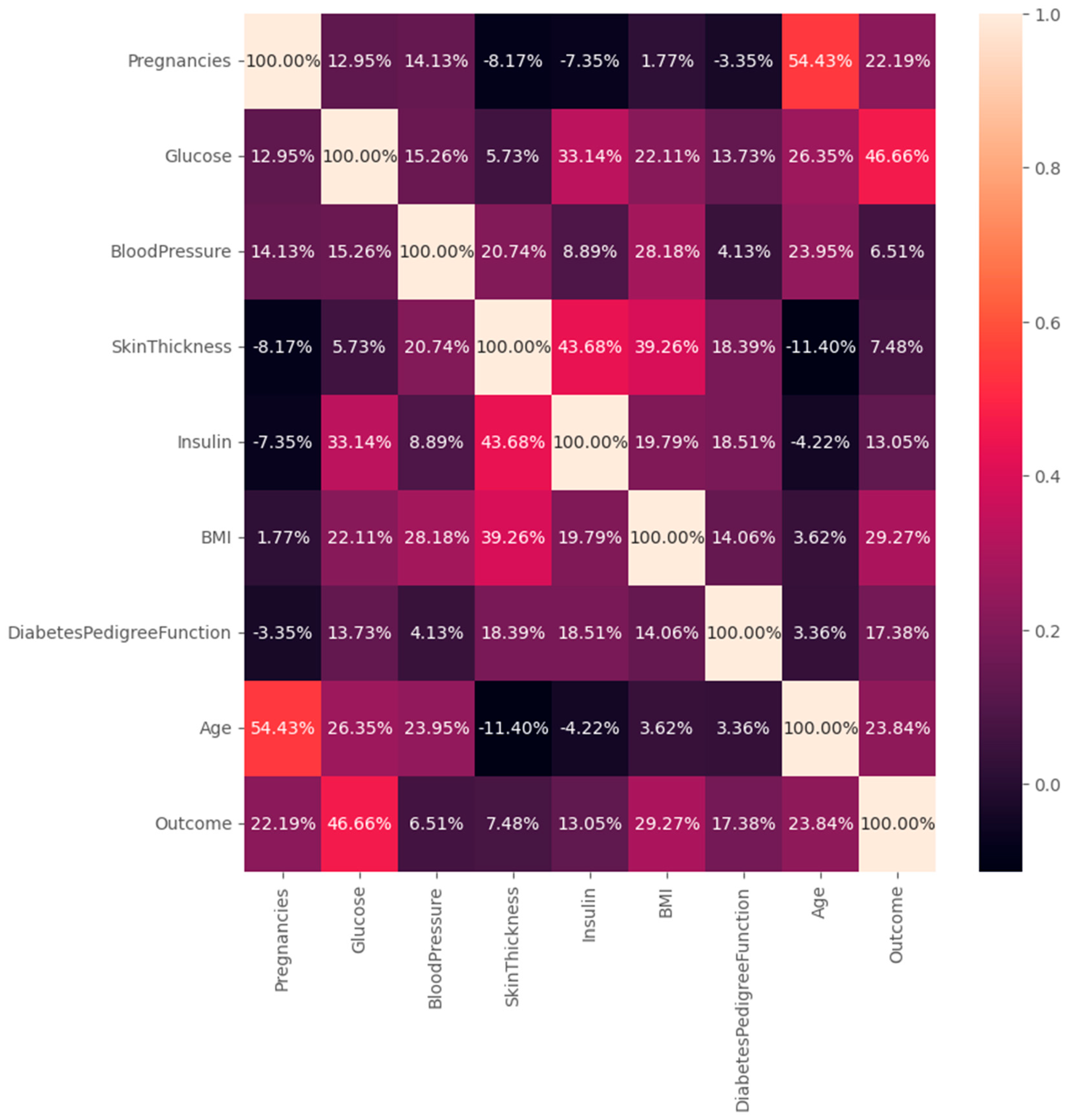

Appendix A – Dataset Overview

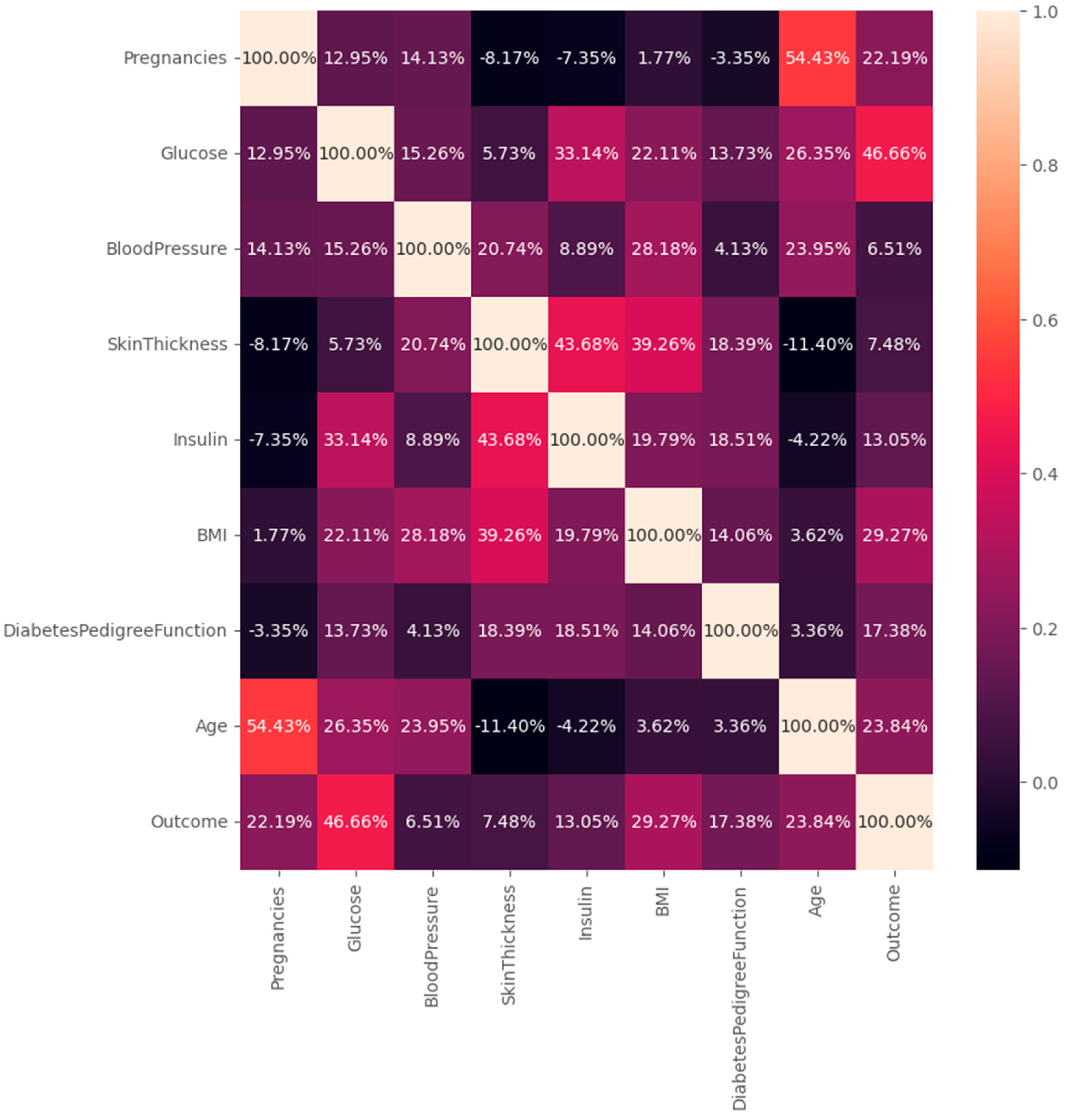

| Feature | Description |

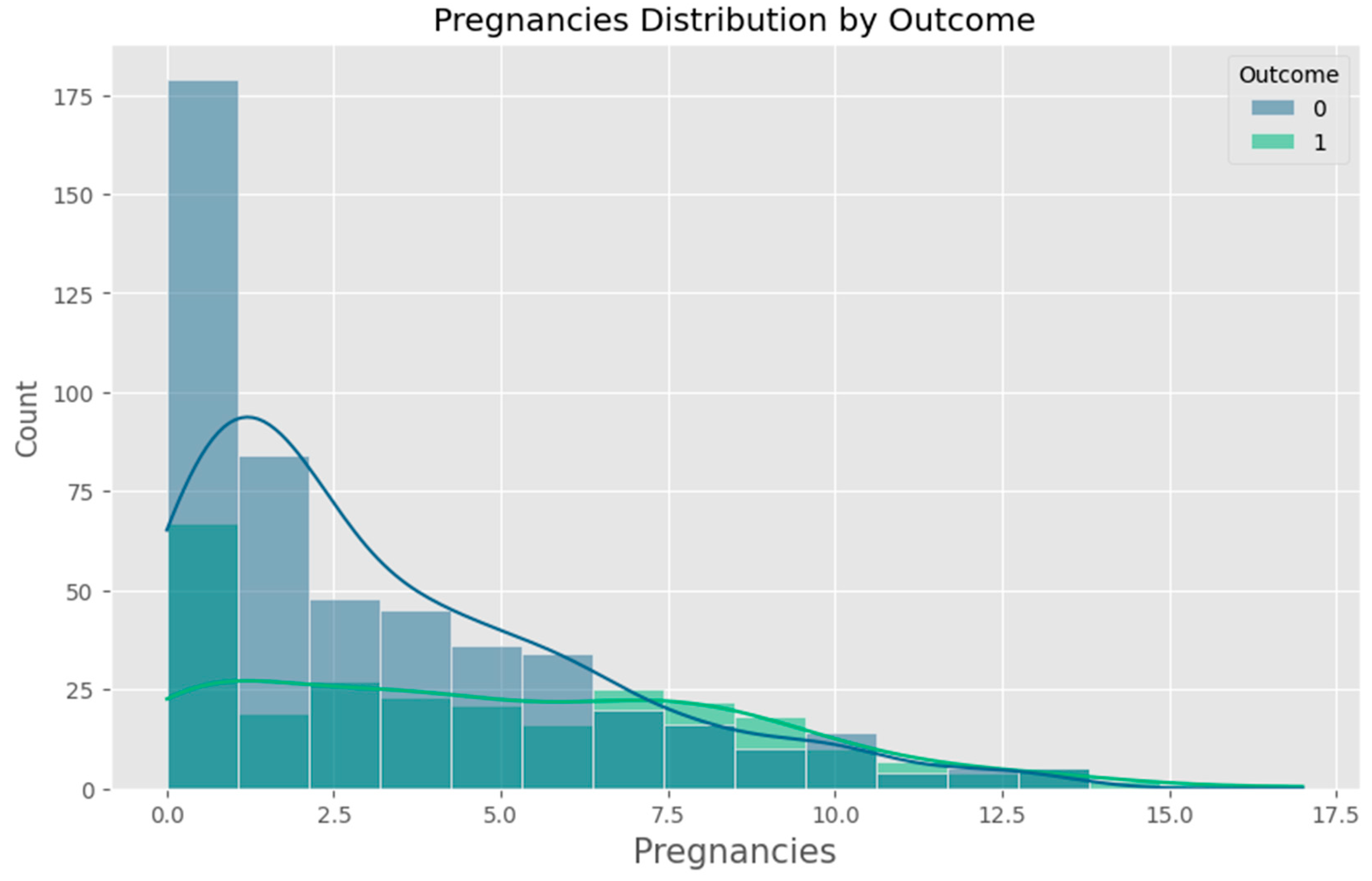

| Pregnancies | Number of times the patient has been pregnant |

| Glucose | Plasma glucose concentration (mg/dL) |

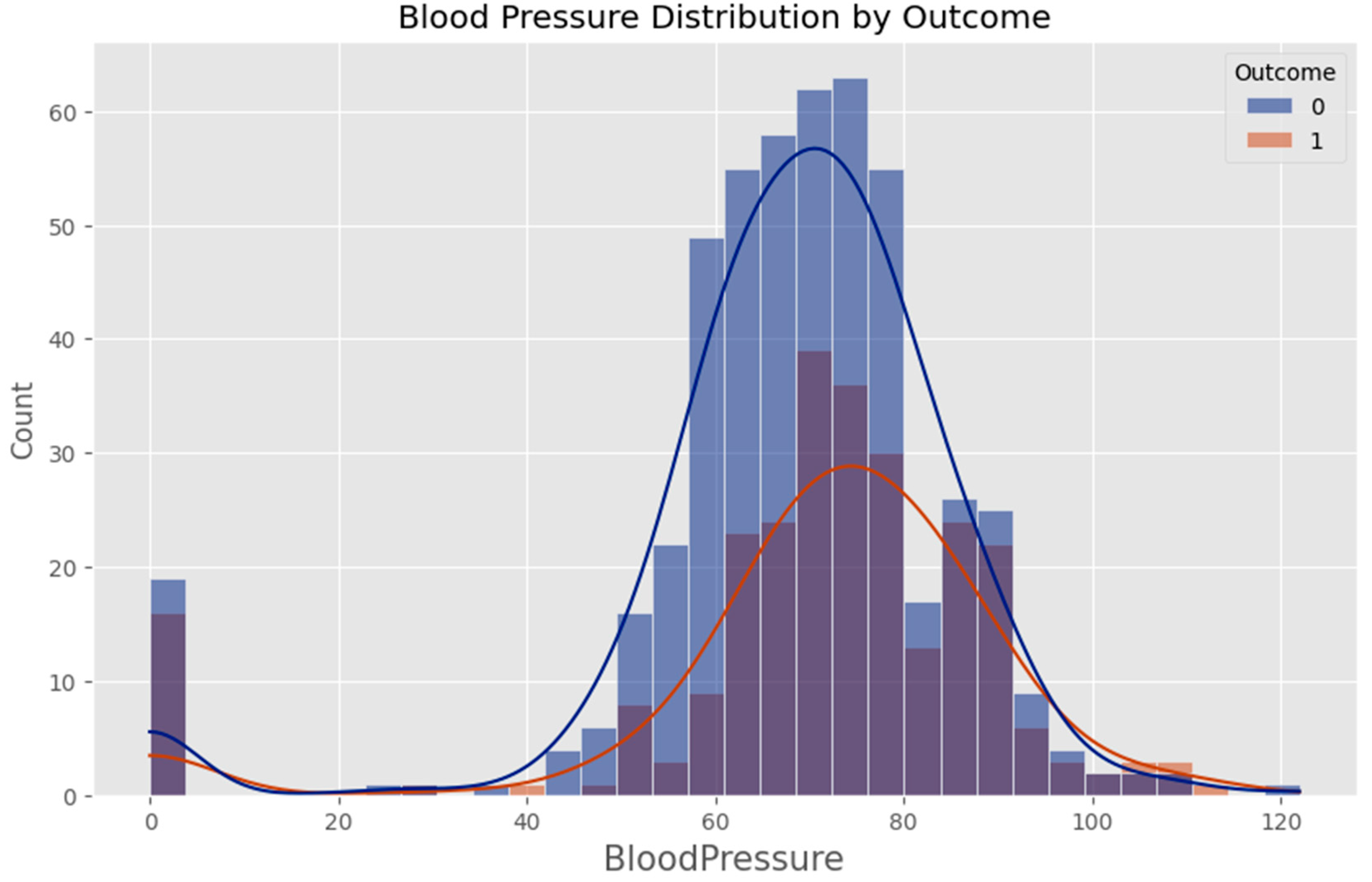

| Blood Pressure | Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) |

| Skin Thickness | Triceps skin fold thickness (mm) |

| Insulin | 2-Hour serum insulin (mu U/ml) |

| BMI | Body mass index (kg/m²) |

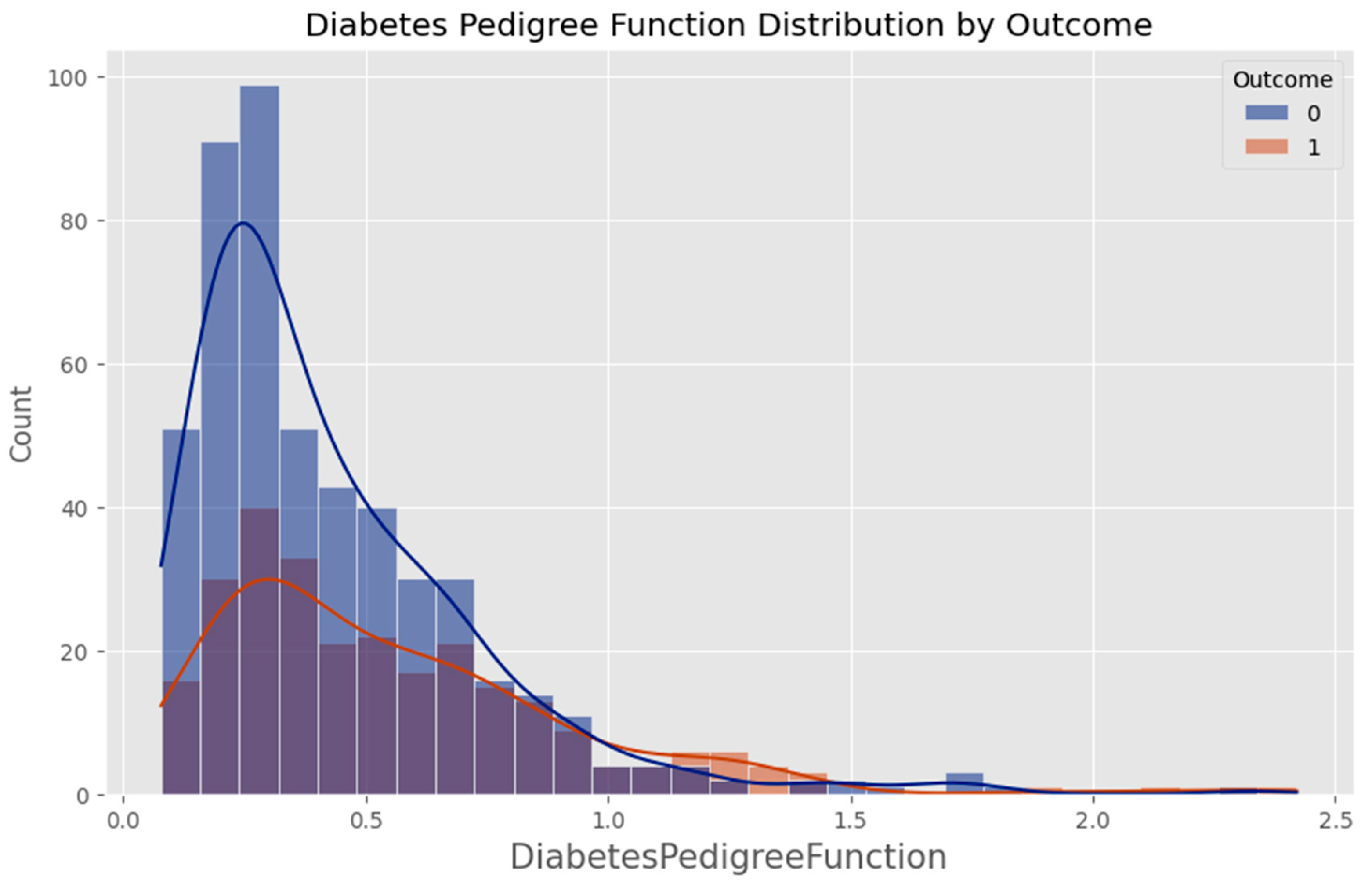

| DPF | Diabetes Pedigree Function (genetic risk indicator) |

| Age | Age of the patient (years) |

| Outcome | 0 = non-diabetic, 1 = Diabetic (target label) |

Appendix B – Key Machine Learning Code

B.1 Model Training (Logistic Regression)

B.2 Data Preprocessing and Scaling

B.3 Saving the Model and Scaler

Appendix C – Flask Server Code Snippets

C.1 Model Loading

C.2 Prediction API Endpoint

Appendix D – Client (React) Integration

D.1 API Call in Prediction.jsx

D.2 Input Form Elements

Appendix E – Evaluation Outputs

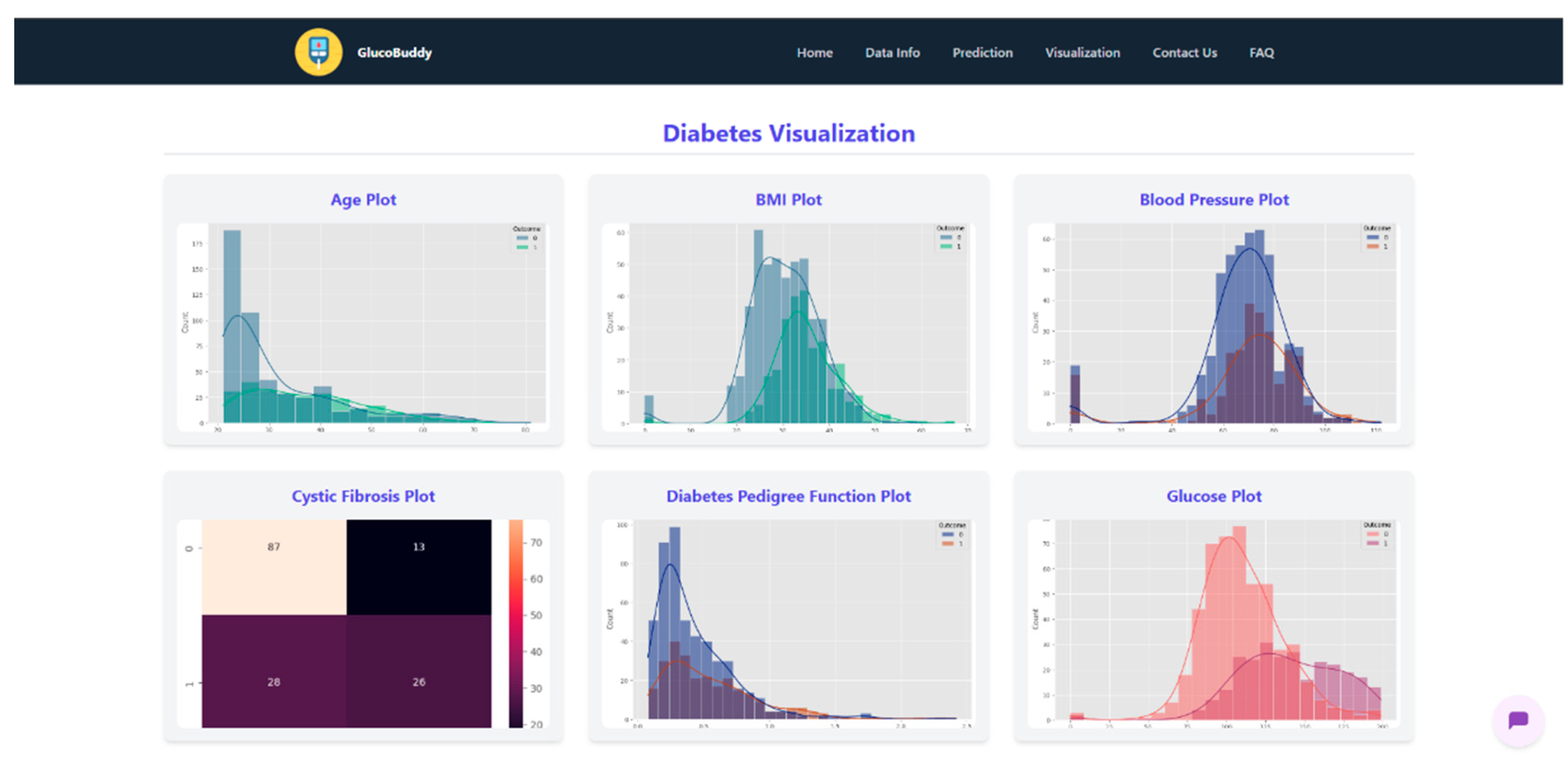

E.1 Sample Classification Report (Logistic Regression)

E.2 Confusion Matrix

Appendix F – Visualizations

Appendix G – Client UI Screenshots

References

- World Health Organization, “Diabetes”. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 10th ed.; International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.; et al. Early detection of type 2 diabetes using machine learning models. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 35445–35456. [Google Scholar]

- Kavakiotis, E.; et al. Machine learning and data mining methods in diabetes research. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 2017, 15, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sisodia, D.; Sisodia, D. Prediction of diabetes using classification algorithms. Procedia Computer Science 2018, 132, 1578–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kate, R.J. Using dynamic feature selection for real-time patient risk prediction in emergency departments. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2014, 18, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scikit-learn developers. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. Available online: https://scikit-learn.org (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Kaggle. “PIMA Indians Diabetes Database”. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/uciml/pima-indians-diabetes-database (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Milinovich, A.; Kattan, M. Software applications for patient education in diabetes. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2018, 20, 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; et al. Smartphone-based health management apps: A review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e90. [Google Scholar]

- Dua, P.; Dua, A. A survey on healthcare chatbot systems: Applications, challenges and research issues. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2021, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Sezgin, T.M. Conversational agents in healthcare: A review. Healthcare 2021, 9, 545–562. [Google Scholar]

- Chawla, N.; et al. SMOTE: Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2002, 16, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyon, I.; Elisseeff, A. An introduction to feature extraction and selection. In Feature Extraction; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2006; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, S.M.; et al. A comparison of SVM and LR for diabetes prediction. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2017, 162, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett, T. An introduction to ROC analysis. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2006, 27, 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Python Software Foundation. Pickle—Object Serialization. Available online: https://docs.python.org/3/library/pickle.html (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Flask Framework. Flask documentation. Available online: https://flask.palletsprojects.com/ (accessed on 27 May 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).