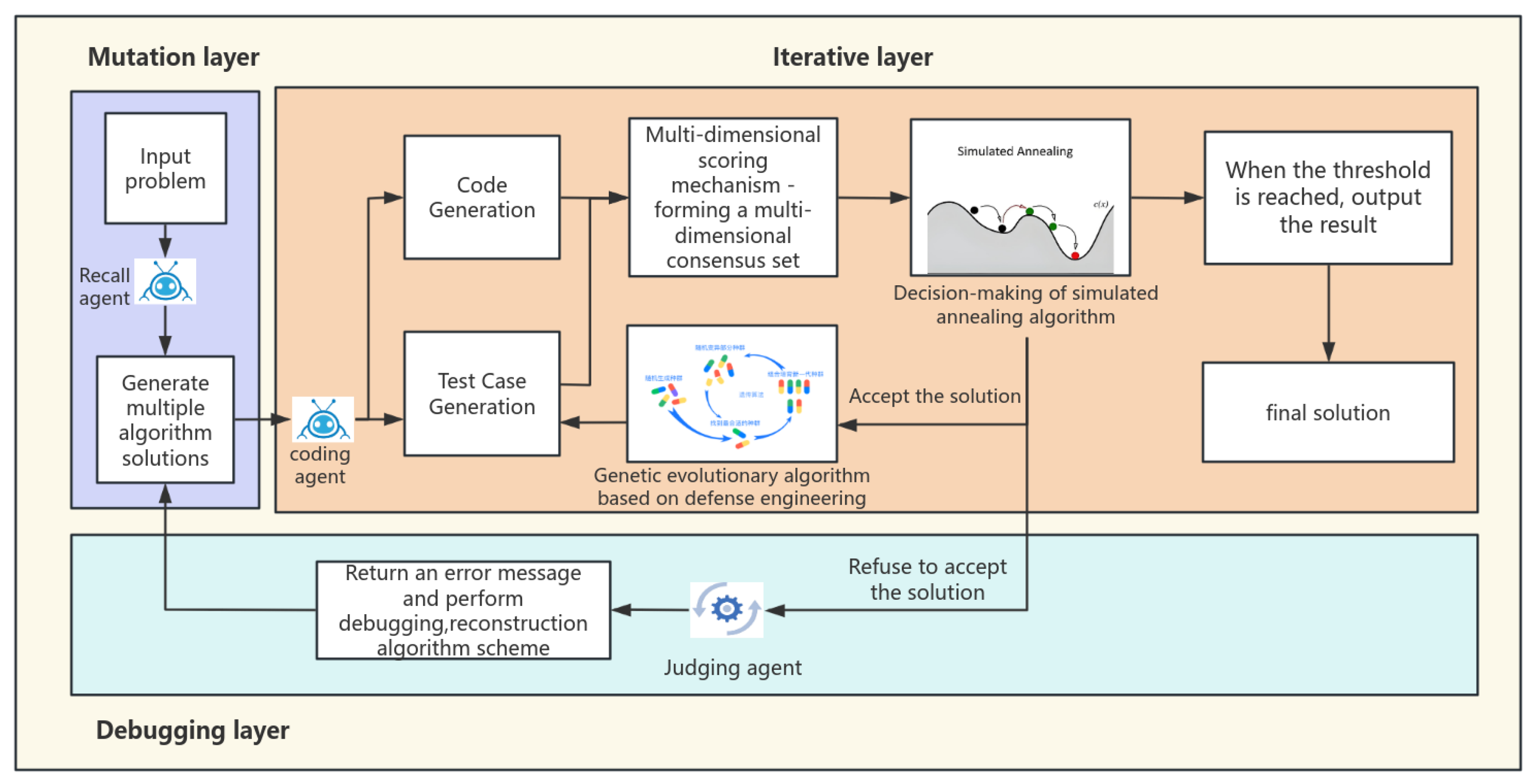

3.3.3. Innovation Mechanism

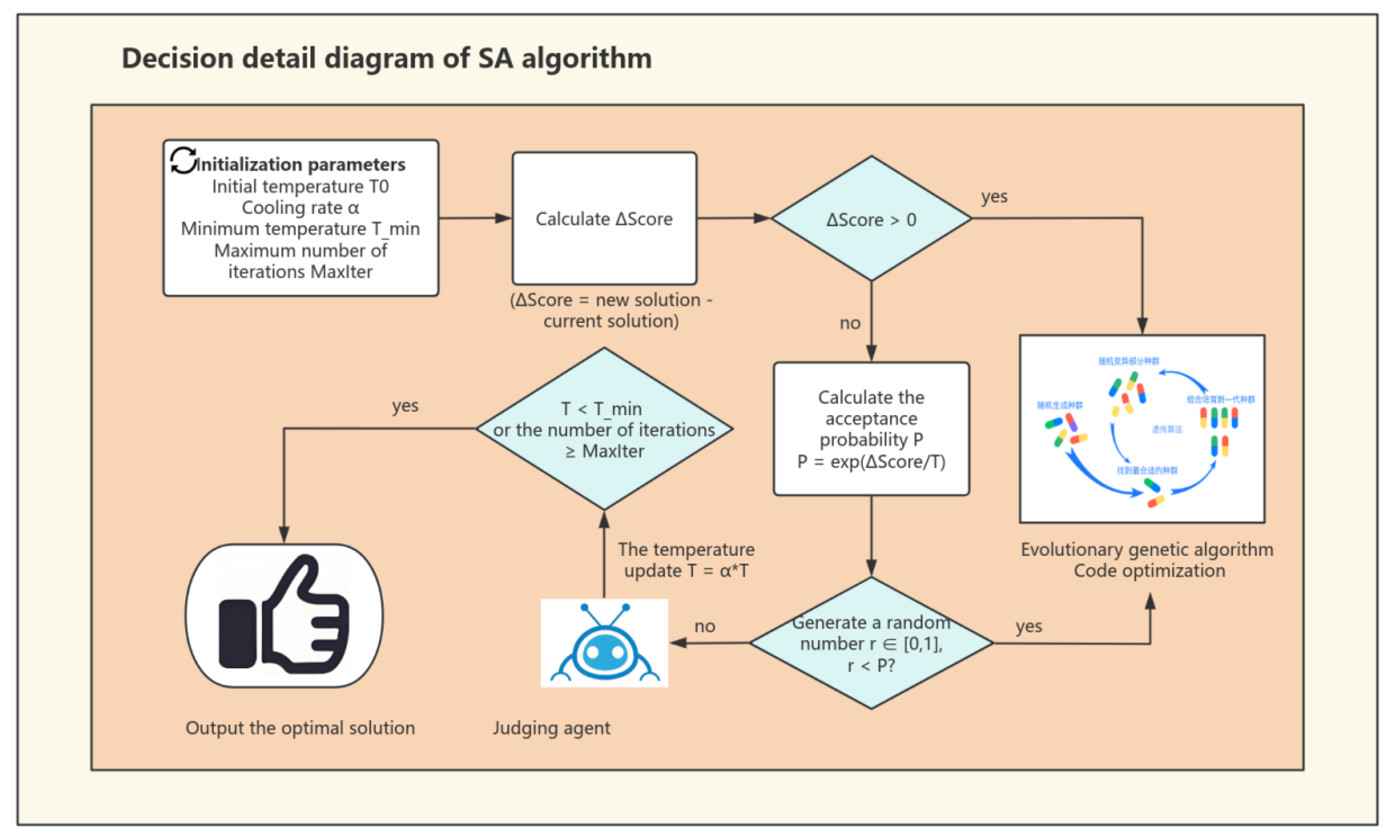

In the annealing decision module, the acceptance probability of suboptimal solutions is governed by the temperature

T. We utilize a dynamic adjustment technique for temperature

T. The initial temperature

is established according to the problem’s complexity.

is defined by the quantity of initial candidate solutions and their respective fitness ratings. If the average fitness decreases, indicating a more challenging problem, we will increase the temperature to extend the exploration phase. The adaptive technique, unlike a constant temperature such as

set at 1000, facilitates expedited convergence and reduces computing expenses in simpler tasks while ensuring sufficient exploration in difficult tasks, enhancing convergence speed by 30% in datasets like APPS.

:the maximum value of fitness theory (such as the upper limit of scoring). :the average fitness score of the initial population. :initial fitness variance. :smoothing factor (to prevent the denominator from being 0, usually taking the value of ) . The formula dynamically sets the initial temperature to suit the problem’s complexity. It ensures that harder problems, which usually have a lower average fitness in the initial population, get a higher T0. This allows for broader exploration of the solution space. By doing so, it helps the algorithm avoid getting trapped in local optima early on and significantly improves the efficiency of the optimization process.

We employ an adaptive dynamic cooling adjustment method that integrates exponential cooling with variance feedback to mitigate temperature fluctuations. The present population fitness variance (

) indicates the diversity of solutions. An elevated value signifies more population diversity and a wider range of solutions, necessitating a reduced cooling rate to extend the exploration phase. Conversely, less variance in population fitness indicates an increasing homogeneity within the population, requiring expedited cooling for swifter convergence. The constant

C functions as a tuning parameter to regulate the sensitivity of the cooling rate to variability. According to previous study experience,

C is often established at 100 to equilibrate the effects of variance variations.

: The temperature of the next generation, controlling the degree of attenuation of the acceptance probability of the inferior solution. : The current temperature affects the exploration ability of the current iteration. :The basic cooling coefficient is the reference rate of temperature attenuation that determines the temperature. :Population fitness variance measures the diversity of the current solution. C:Variance sensitivity adjustment constant, controlling the influence of variance on the cooling rate. This formula adjusts cooling based on solution diversity: slows cooling to explore when diverse, speeds up when converging.

The dynamic temperature adjustment approach proficiently addresses the limitations of conventional exponential cooling, which employs a constant cooling rate, such as . This conventional method fails to ascertain the true condition of the population, which may result in premature convergence or superfluous iterations. Conversely, the hybrid strategy regulates temperature adaptively, enabling a reduction that responds dynamically to the problem’s complexity. When addressing issues of greater complexity or significant initial variance, this strategy automatically prolongs the high-temperature phase. It attains rapid convergence for less complex problems.

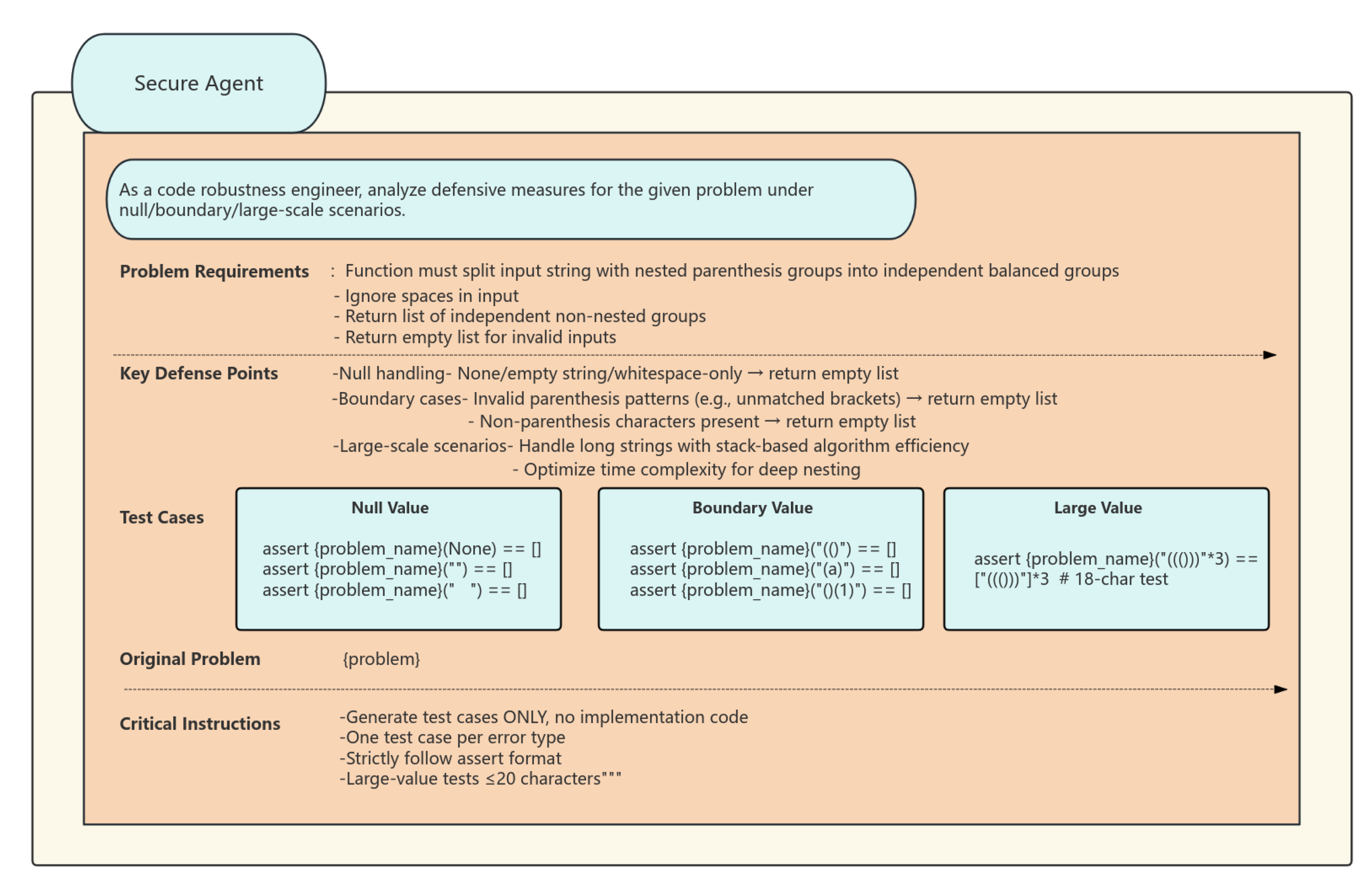

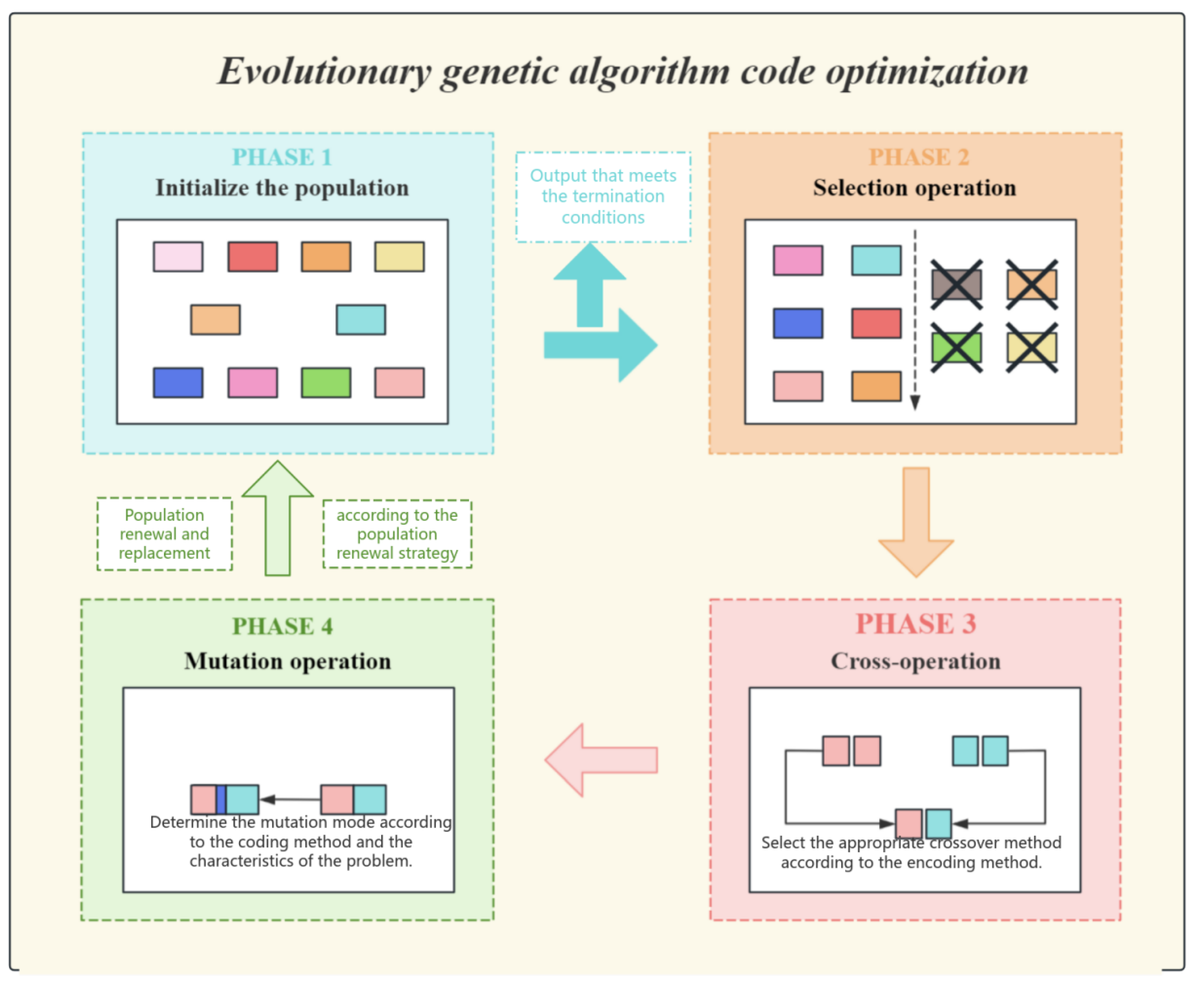

Figure 7.

The Detailed Diagram of Evolutionary Genetic Optimization.

Figure 7.

The Detailed Diagram of Evolutionary Genetic Optimization.

The fundamental decision-making mechanism of simulated annealing relies on the probability acceptance criterion dictated by temperature

T. This criterion is the principal mechanism for determining the acceptance of a suboptimal solution—a new solution with a score inferior to the existing one.

is defined as Scorenew minus Scorecurrent, indicating the score disparity between the new and current solutions, and

T denotes the current temperature parameter. When

exceeds 0, it signifies that the new answer is superior and will be accepted unequivocally. Nevertheless, when

is less than or equal to zero, the new solution is deemed suboptimal. However, even if the new approach reduces the readability of the code while presenting an innovative structure, there is a certain likelihood of its preservation. The retention likelihood is predominantly influenced by temperature T. In the high-temperature phase, the algorithm is inclined to accept suboptimal solutions, promoting the exploration of novel regions, particularly in the initial phases. By doing comprehensive searches throughout the solution space, it prevents entrapment in local optima. In the low-temperature phase, the algorithm prioritizes fine-tuning in its later phases, concentrating on high-quality solutions while nearly discarding all inferior options and prioritizing localized optimization.

: The probability of acceptance of the inferior solution. Score: The difference in fitness between the new solution and the current solution. T: Current temperature. At high T, it accepts some worse solutions to escape local optima; at low T, becomes increasingly greedy.

Convergence determination formula provides a clear stopping condition for the algorithm. It halts iterations when the maximum adaptation change in the last five iterations falls below a predefined threshold, indicating that the algorithm has reached a stable state. This ensures that computational resources are used efficiently, preventing unnecessary iterations once the solution has stabilized and saving time and computational power for more productive use.

:the score changes in the last five iterations. :convergence threshold,termination when the score fluctuation is less than 1%. This formula flags convergence if score improvements are less than 1% over five generations.

The resource consumption constraint formula acts as a financial advisor for the algorithm, meticulously setting a token budget to keep resource usage in check. It plays the role of a vigilant supervisor, continuously monitoring how many tokens the algorithm is gobbling up during its operations. If the algorithm starts to overspend and exceeds the predefined budget, the formula steps in like a strict accountant, terminating further iterations to prevent any wasteful resource drain. This makes the algorithm a perfect fit for those tight-budget, resource-constrained environments where computational resources are as precious as gold, and every ounce of efficiency counts towards making the algorithm’s practical implementation a reality.

:the number of candidate solutions generated in the KTH iteration. TokenCost:token consumption of a single candidate solution. : Maximum token budget. Enforces token/API call limits by reducing population size or early stopping when approaching budget.

In a multi-dimensional scoring system, fitness scores are assessed based on four indicators. Functional correctness is assessed by test case pass rates; execution efficiency is shown by normalized scores of time and memory utilization; symmetry encompasses logical branch symmetry and interface symmetry; and readability is evaluated based on static analysis scores from Pylint. Concerning dynamic weight regulations, if the problem description includes terms like "efficient" or "low latency,"

is elevated to

. In the event that symmetry constraints are identified,

is established at a minimum of 0.3. Customized scoring criteria are established based on particular specifications, producing solutions that more closely conform to the intended standards.

:the weight is dynamically adjusted. fi:The fitness score of the i-th dimension. Weighted combination of functionality, efficiency, symmetry , and readability , with dynamic adjustments.

Table 2.

The weight of each scoring dimension can be dynamically adjusted according to actual needs to reflect its importance in the overall scoring. For example, if the time complexity is particularly important in the scenario, a higher weight can be set for it

Table 2.

The weight of each scoring dimension can be dynamically adjusted according to actual needs to reflect its importance in the overall scoring. For example, if the time complexity is particularly important in the scenario, a higher weight can be set for it

| Code set |

Time complexity |

Space complexity |

Code readability |

Test pass rate |

Final score |

| Evaluation Code 1 |

|

× |

|

80% |

75 |

| Evaluation Code 2 |

× |

|

|

90% |

78 |

| Evaluation Code 3 |

|

|

× |

85% |

85 |

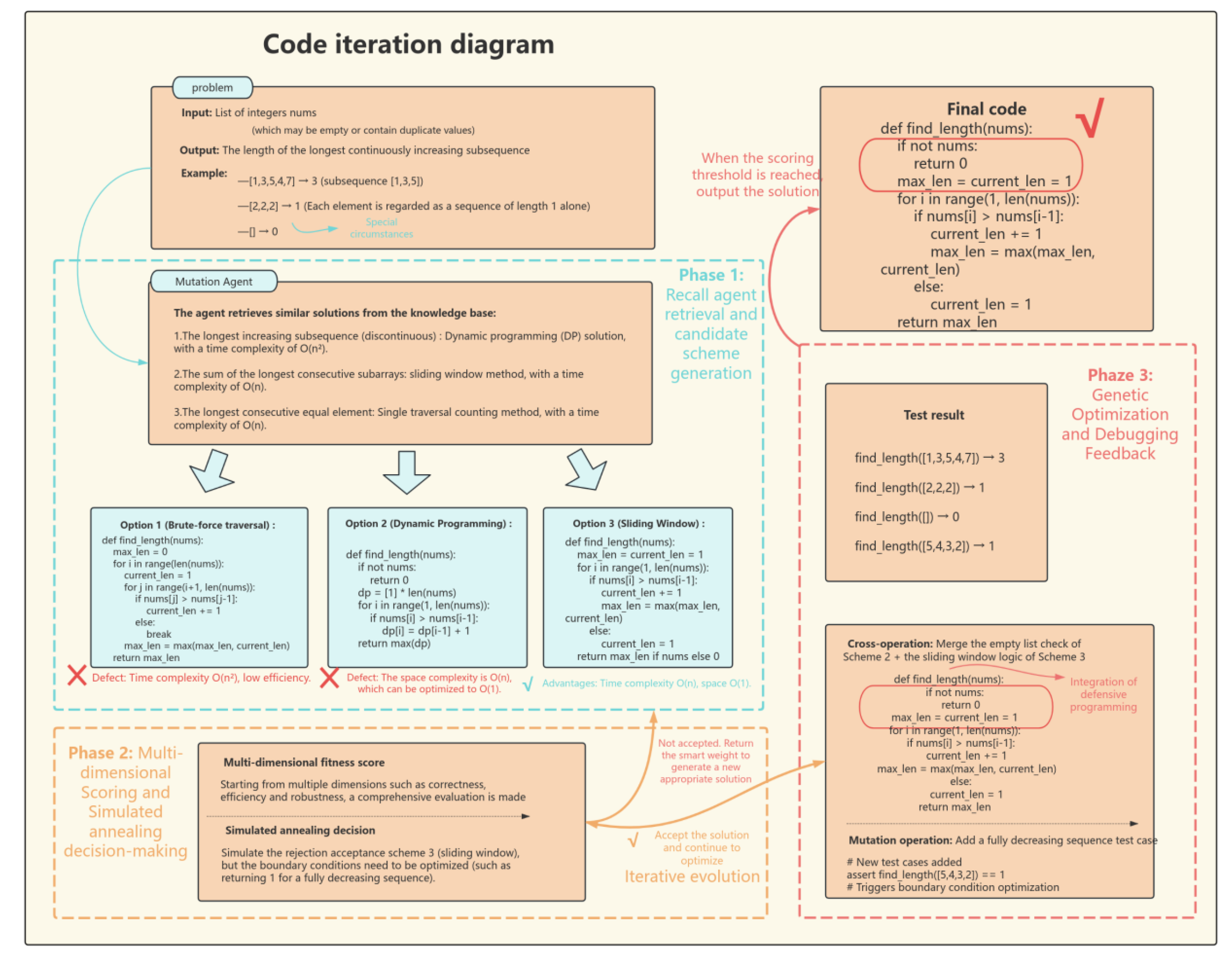

The essential component of the evolutionary operation is the evolving genetic algorithm, which employs a hybrid approach between elitism and tournament selection during the selection phase. Only individuals in the top ten percent of fitness are directly kept for the subsequent generation, while the remaining individuals produce parents via tournament selection. The crossover operation can be incorporated with the defensive code template library, encompassing input validation, error handling, and boundary condition checks, thereby ensuring that the resulting code operates correctly and adheres to robust defensive programming principles. We employ directed syntax mutation to enhance code robustness, which has proven to be more effective than random mutation techniques. Utilizing boundary reinforcement, dynamic boundary verifications are incorporated within loops or conditional expressions.

: individual fitness. This formula is essentially a dynamic balance point established between "ensuring the convergence quality" and "maintaining the exploration ability", and its parameters (10% elite ratio, tournament size 5) have been determined through empirical research as the optimal configuration for the code generation task.

The defensive cross-operation formula is like a clever safeguard woven right into the fabric of the code-generation crossover process. It’s not just about mixing and matching code snippets; it’s about embedding smart defensive programming techniques. By weaving in error-handling mechanisms that act like safety nets, catching and managing any unexpected hiccups, along with input validation that acts as a strict gatekeeper, ensuring only the right kind of data gets through, and boundary condition checks that keep a vigilant eye on the code’s operational limits, this formula gives the generated code a real boost in terms of robustness and reliability. This means fewer nasty runtime errors and exceptions popping up to ruin the party, and code that doesn’t just do its job right but also stands strong against all sorts of error-inducing challenges. All in all, it’s a big win for the overall quality and maintainability of the software, making it a breeze to keep in tip-top shape for the long haul.

:standard crossover operations, such as single-point crossover or uniform crossover. DefenseTemplate:a defensive code template library, including modules such as input validation and error handling. This formula flexibly combines the parent solution with the forcibly injected defense template (input validation, error handling) to enhance the defense performance of the generated code.

Directional grammar variation formula identifies vulnerable points in the code structure for mutation. By analyzing the code’s syntax and pinpointing areas that are prone to errors or have weak error-handling capabilities, it applies targeted mutations. This approach aims to optimize code quality and robustness, ensuring that the generated code can gracefully handle edge cases and exceptions, thereby improving its reliability and reducing the need for extensive post-generation debugging.

AST:the tree-like structure representation of the code. :the sensitivity of fitness score to code node s. We can use formulas to locate sensitive nodes through AST analysis, for example, automatically insert range validation logic above loop statements.

The formula for population diversity is designed to maintain a healthy balance within the genetic algorithm by monitoring the diversity of solutions. When diversity is too low, it indicates that the population may be converging prematurely on a suboptimal solution. Conversely, when diversity is too high, it may suggest that the algorithm is not effectively focusing on the most promising solutions. By tracking these levels, the formula ensures the algorithm doesn’t settle for suboptimal results too quickly and continues to explore the solution space effectively.This balance is crucial as it prevents the algorithm from becoming trapped in local optima, instead encouraging a thorough exploration that can lead to the discovery of high-quality solutions which might otherwise be missed. The benefits of this mechanism are significant, as it enhances the algorithm’s ability to find more optimal solutions, improves the overall efficiency of the optimization process, and increases the likelihood of achieving better results in a wide range of applications. By maintaining this balance, the genetic algorithm can operate at its best, delivering more reliable and effective solutions to complex problems.

:population fitness variance. :population average fitness.The population diversity metric quantifies solution spread by normalizing fitness variance against mean fitness. It dynamically regulates exploration: triggers forced mutation when diversity drops below 5% (preventing premature convergence) and restricts crossover above 20% (controlling excessive randomness). This maintains optimal genetic variation throughout evolution.