1. Introduction

Palatal implant application for orthodontic purpose was initially clinically proposed using a specifically bone integrated implant system specifically designed for orthodontic anchorage needs. [

1]

Almost 10 years later non osseo-integrated orthodontic palatal miniscrew were proposed to improve anchorage management in palatal hybrid hyrax expansion protocol.[

2]

Numerous scientific articles proposed guidelines for palatal miniscrew insertion exploring the anatomic characteristics of the palatine vault in terms of total bone depth, and cortical and mucosa thickness. [

3,

4]

The published reports concluded by proposing what are the ideal palatal insertion sites. However, all the articles reported for the optimal insertion sites minimum values and standard deviation of bone depth that clearly showed a high individual patient variability. This variability causes in some patients less than 8mm of total palatal bone depth for the optimal insertion sites. 8mm is the minimum length of a palatal orthodontic miniscrew in the orthodontic market.

Consequently, the literature confirmed if the patient presents not optimal characteristics for palatal miniscrew insertion even the smallest palatal miniscrew could protrude during insertion into the nasal cavity. [

3,

4]

So, if the aim of the clinicians is to perform a miniscrew application within the palatal bone a CBCT evaluation along with miniscrew position planning is mandatory.

Once the miniscrew position is planned specific software can be used to design surgical insertion guides to help the clinician to place the palatal orthodontic miniscrew in the planned position.[

5,

6]

Surgical guides can be printed with 3D printing technology and specifically certified approved resin for surgical guide fabrication.

Although this procedure was already described in the orthodontic literature no studies evaluated its accuracy comparing the final miniscrew position with the totally virtual planned miniscrew position.

The aim of this retrospective study was to evaluate in vivo the accuracy of surgical guides obtained by 3D printing technology, used to transfer, during palatal miniscrew placement, its 3D software planned position and axis.

2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective cross-sectional CBCT study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Its protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Messina (prot.33-2020).

The University clinic’s database was searched and records of patients showing the following criteria were selected: caucasian subjects with permanent dentition (excluding third molars) that performed a CBCT exam for planning skeletal palatal anchorage with two miniscrews placed in the anterior palatine vault, aged between 14 and 22y.o., no history of previous orthodontic treatment; absence of craniofacial abnormalities or congenital syndromes such as cleft lip and palate, cysts, or maxillary tumors. Moreover, the included subjects presented in their folder the following records: digital models obtained with an intra-oral scanner, supplementary maxillary scan taken for scanbodies position registration, and CBCT scan of maxilla stored as a DICOM file.

24 cases fulfill the inclusion criteria, their records were checked for quality and integrity and included in this investigation. Patients were divided by gender into two numbered groups, and each group was sorted by age. A random sequence generator was used to create two lists of randomized numbers of 11 and 13 units.

The final sample size was determined through a preliminary power analysis, using data obtained from the first 10 patients included in the study. To ensure the robustness of the results, an additional evaluation was carried out based on studies available in the literature. The parameters considered for the analysis were: 0° (planned miniscrew angulation), 2.3° (maximum angular discrepancy between the planned and final miniscrew axis), and 2.6 (common standard deviation). The power level was set at 0.8, and the significance level at 5%. The results of the analysis indicated that a sample of 21 cases would be sufficient to achieve the desired statistical power. To minimize the risk of false-negative results, the sample size was increased to 24 subjects (12 females and 12 males). Case enrollment was performed using a balanced randomization system based on patient gender. The final sample included 24 subjects (mean age 18.4 ± 3.15 years), with 12 male subjects (mean age 17.7 ± 3.06 years) and 12 female subjects (mean age 19 ± 3.56 years). The overall sample included 8 subjects with skeletal Class I, 10 subjects with skeletal Class II, and 6 subjects with skeletal Class III.CBCT and lateral cephalogram records were generated by the Kavo OP 3D Pro CBCT scanner (Kavo Dental Technologies, Imaging Sciences International, Hatfield, PA, USA). CBCT exams were performed setting the following parameters acquisition: 90 kv, 6.3-8 mA, 5-8 seconds exposure time. Lateral cephalograms were executed with the following parameters: 90kv, 10mA, 16sec.

Digital maxillary models were obtained by intro-oral scanner acquisition (Medit i500, Medit, Seoul, Republic of Korea) and exported in STL file format.

DICOM files and maxillary digital model have been imported into a specific software used for planning 3-dimensionally miniscrew position (BlueSkyPlan software version 4.7, Blue Sky Bio, LLC, Grayslake, IL, USA).

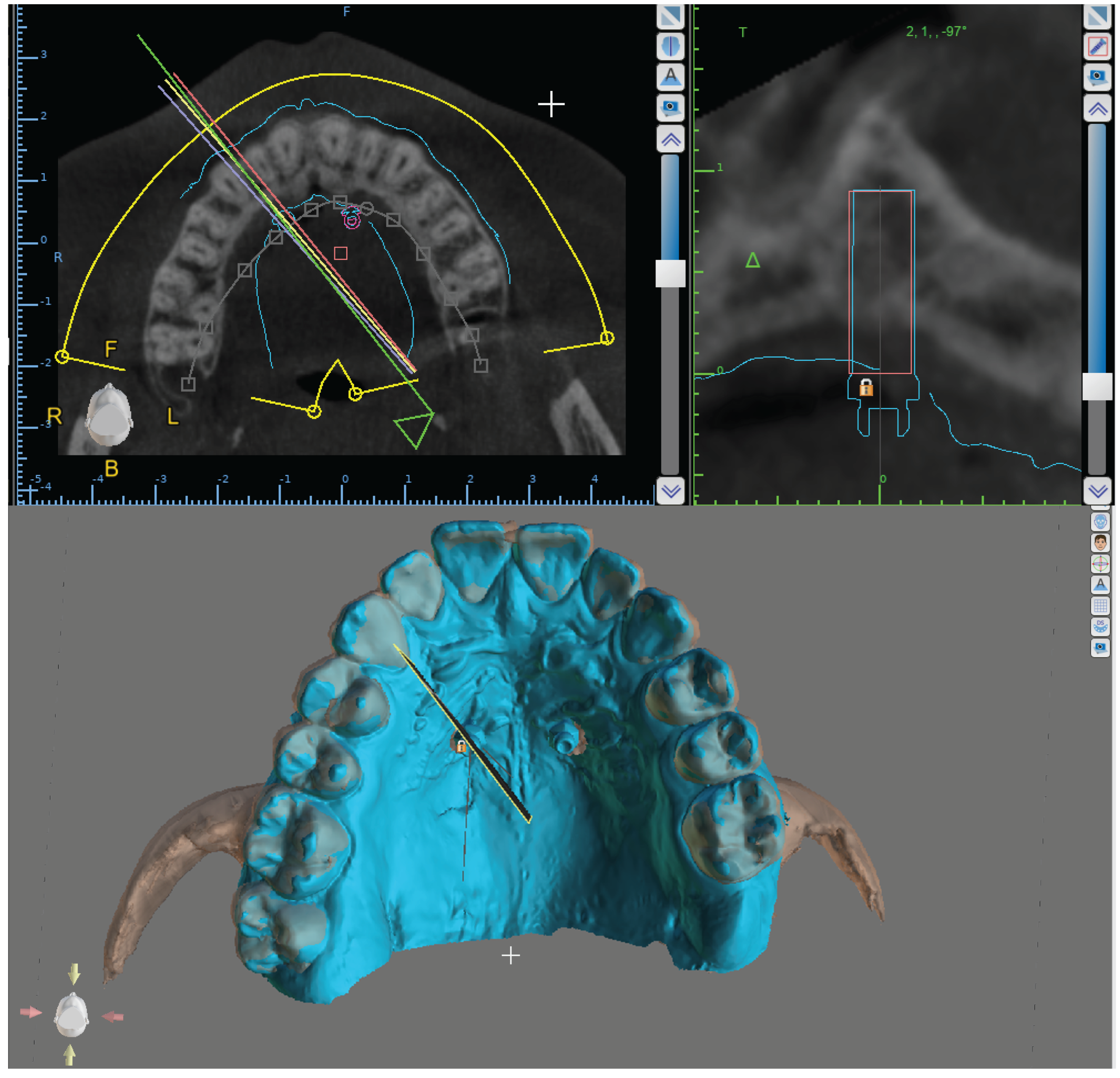

Subsequently, Blue Sky Plan software was used to superimpose maxillary digital models and CBCT volumes (

Figure 1). The software (internationally registered as a medical device) used an algorithm to automatically superimpose the digital maxillary model and the CBCT volume scan. Blue Sky Plan software was also used to design the surgical guide.

Outcome measurements were performed on both the right and left sides of the evaluated cases.

The surgical guide was exported as an STL file, imported into the software of the 3D printer (Form2, Formlabs Ohio Inc., Millbury, OH, USA), and printed with supports. The 3D printing process was performed according to the 3D printer manufacturer’s instructions with a specific resin designed for surgical guide fabrication (Surgical Guide Resin, Formlabs Ohio Inc., Millbury, OH, USA).

At the end of the 3D printing process, the supports were removed, and the surgical guides were polished and additionally cured for 5 minutes.

Surgical guides were designed to incorporate metal bushings provided by the miniscrew manufacturer (HDC, Thiene, VI, | Italy). The bushings were able to intimately couple with a specific pick-up driver able to hold the miniscrew before and during its insertion.

Following administration of local anesthesia to the palatal mucosa adjacent to the planned insertion site, predrilling was performed to facilitate controlled entry and improve accuracy. Subsequently, palatal miniscrew insertion was carried out under aseptic conditions, ensuring primary stability and optimal positioning.

Once the orthodontic miniscrews Regular Plus Konic (HDC, Thiene, VI, | Italy) were inserted, two specific scanbodies were coupled with the two miniscrews and their position and inclination were registered by performing a new intra-oral scan with the intra-oral scanner.

This scan was used to orientate two virtual analogues of the miniscrew. These two analogues were superimposed, using BluSkyPlan Software, to the virtual analogues placed in the corresponding planned miniscrew position.

The maximum insertion angle discrepancy (MIAD) between the planned and final miniscrew analogue axis was visualized and measured. (

Figure 3)

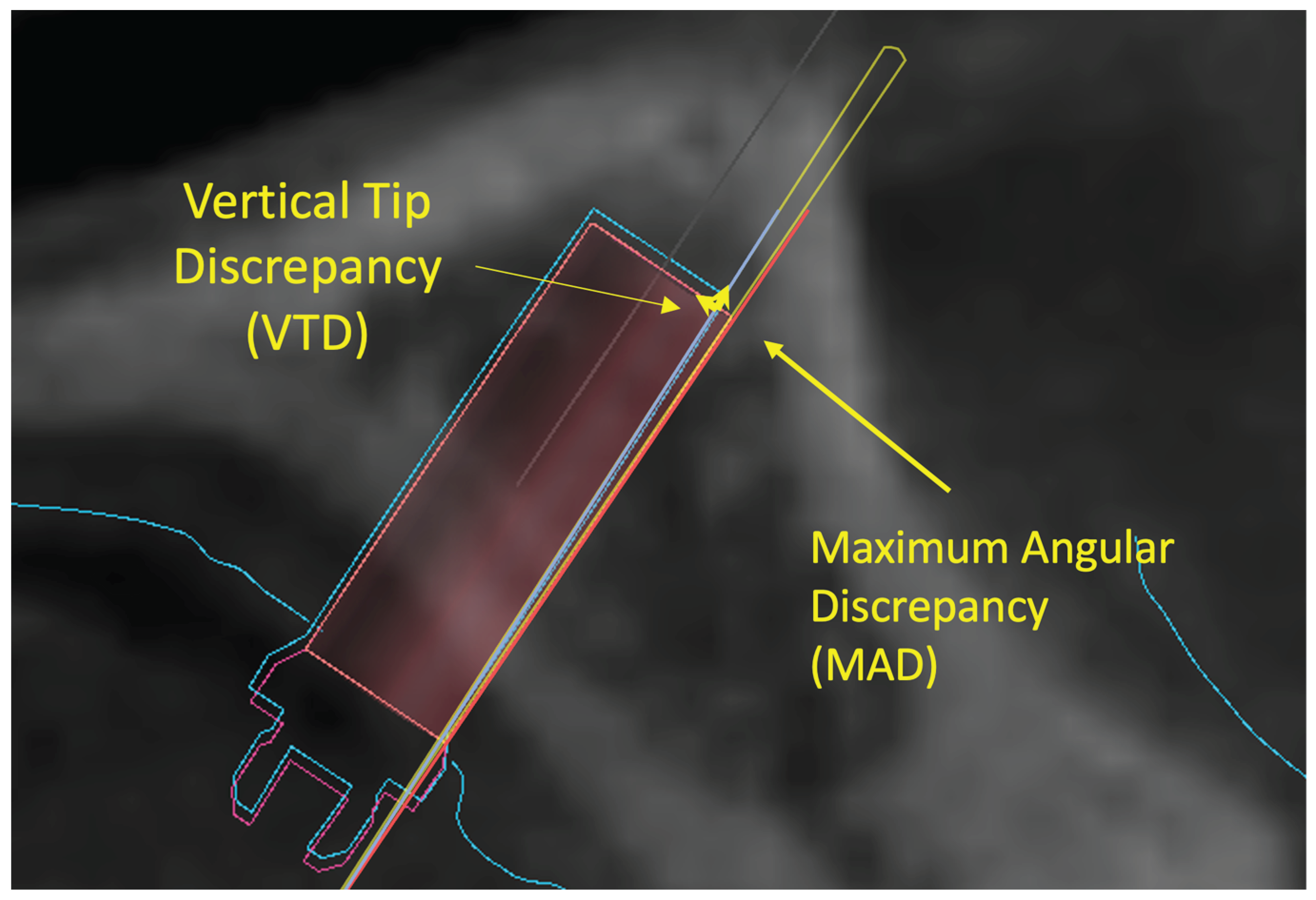

A specific software function able to identify and show all the CBCT scans passing through the miniscrew axis of the planned miniscrew was used to identify the scan showing the maximum discrepancy between the planned and final miniscrew placement.

This scan was used to measure all the outcomes evaluated in this study: maximum angular discrepancy (MAD); maximum vertical tip distance (VTD), the maximum linear distance between the profiles of the planned and final miniscrews measured on lines parallel to the miniscrew axis;(

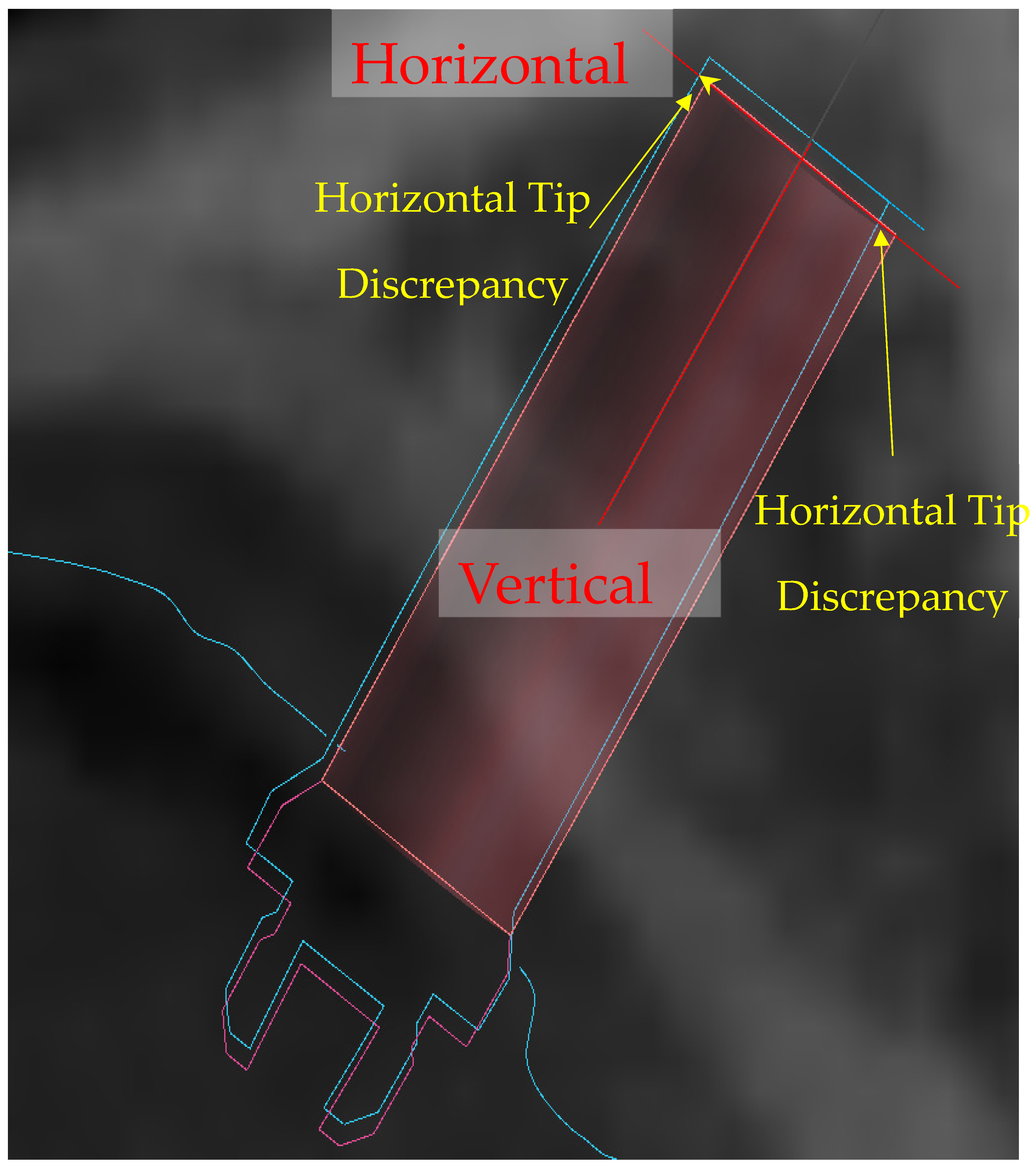

Figure 4) maximum horizontal tip discrepancy(HTDmax), perpendicular to the miniscrew axis; minimum horizontal tip discrepancy(HTDmin); (

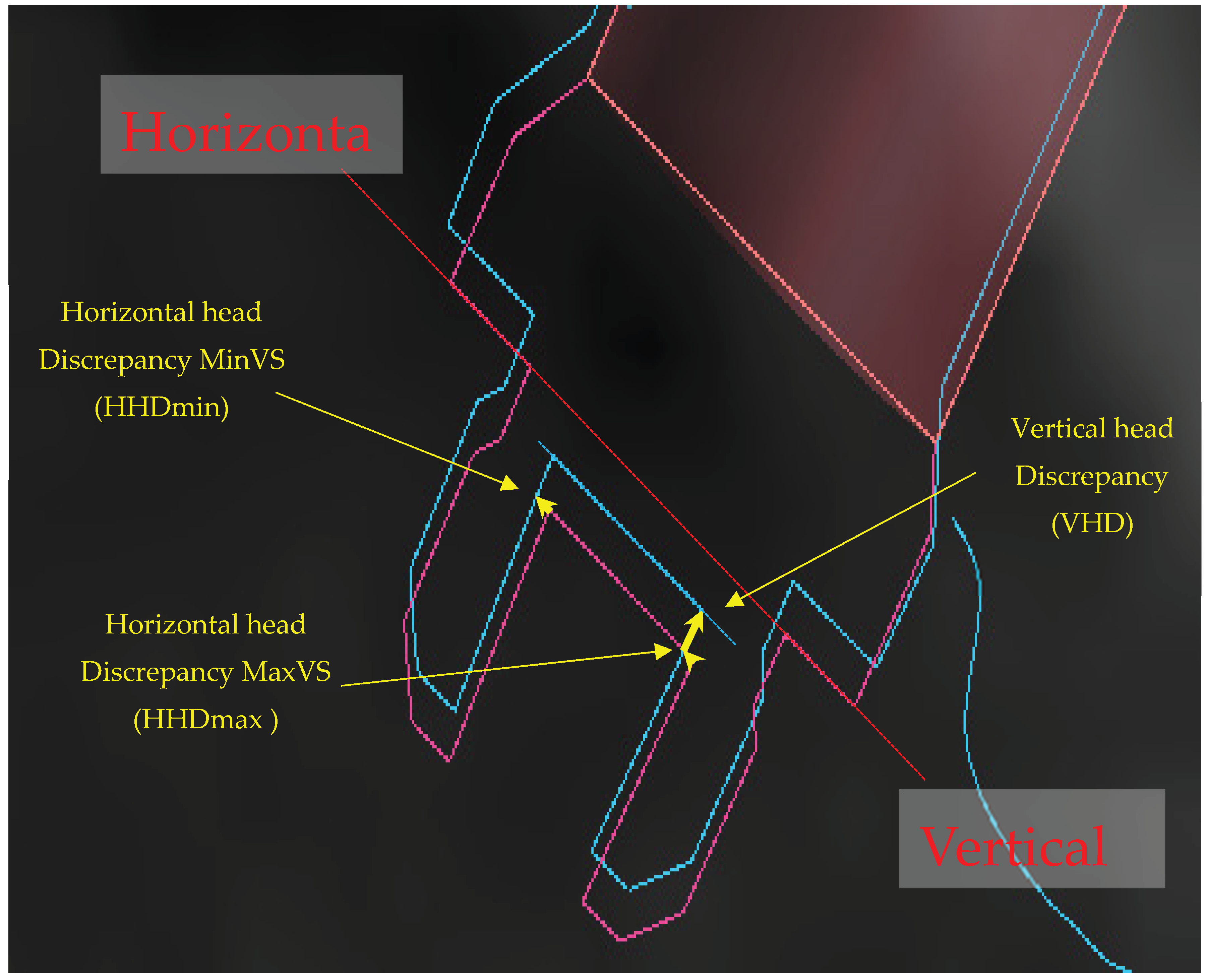

Figure 5) maximum vertical head distance (VHD); maximum horizontal head discrepancy (HHDmax); minimum horizontal head discrepancy (HHDmin). (

Figure 6)

Figure 4.

Software interface, the maximum discrepancy between the placement of the planned miniscrew and the final miniscrew.

Figure 4.

Software interface, the maximum discrepancy between the placement of the planned miniscrew and the final miniscrew.

Figure 5.

Software interface, maximum angular discrepancy (MAD) is identified; maximum vertical tip distance (VTD), the maximum linear distance between planned and final miniscrew profiles measured on lines parallel to the miniscrew axis.

Figure 5.

Software interface, maximum angular discrepancy (MAD) is identified; maximum vertical tip distance (VTD), the maximum linear distance between planned and final miniscrew profiles measured on lines parallel to the miniscrew axis.

Figure 6.

Software interface, maximum horizontal tip discrepancy (HTDmax), minimum horizontal tip discrepancy (HTDmin).

Figure 6.

Software interface, maximum horizontal tip discrepancy (HTDmax), minimum horizontal tip discrepancy (HTDmin).

Figure 7.

Software interface, maximum vertical head distance (VHD), maximum horizontal head discrepancy (HHDmax), minimum horizontal head discrepancy (HHDmin).

Figure 7.

Software interface, maximum vertical head distance (VHD), maximum horizontal head discrepancy (HHDmax), minimum horizontal head discrepancy (HHDmin).

3. Statistical Analysis

All measurements were performed by two orthodontists with at least ten years of clinical experience and advanced expertise in digital orthodontic technologies. To assess inter-operator consistency, a reproducibility analysis was conducted using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), which demonstrated high agreement and confirmed excellent measurement reliability.

Statistical analysis included both descriptive and inferential methods. Descriptive statistics were calculated for each outcome variable, including mean, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum values (

Table 1). The normality of the angular deviation data between the planned and actual miniscrew insertion axes was verified using the Shapiro–Wilk test, which confirmed a normal distribution.

Accordingly, a paired t-test was applied to assess whether the discrepancies between planned and actual positions were statistically significant (

Table 2). No significant differences were observed between the right and left sides for any of the evaluated variables. As a result, the analysis was conducted on the entire sample without distinguishing between sides, focusing solely on the spatial reference points. All analyses were conducted in Stata software (version 17; StataCorp, College Station, Tex).

4. Results

In total, 24 patients had bilateral palatal miniscrews insertion (48 miniscrews).

The analysis revealed measurable discrepancies between the planned and final positions of the miniscrews. On average, an angular deviation of 2,95 ° (SD +/- 1.13 °) was found between the intended and achieved insertion axes, with a screw length of 10 mm.

Greater deviations were observed at the tip of the miniscrew compared to its head, both in the vertical and horizontal planes. This finding was expected, as the tip is geometrically farther from the reference surface of the guide and thus more susceptible to spatial deviation. This highlights the importance of evaluating tip-level discrepancies when assessing the overall accuracy of miniscrew placement.

Despite the observed deviations, the use of 3D-printed surgical guides resulted in an overall improvement in placement accuracy compared to conventional methods. The guided approach reduced error margins; however, a cumulative effect of inaccuracies from each operative step—from digital planning to 3D printing and clinical insertion—was evident. These findings emphasize the need for standardized workflows and careful planning to further enhance the precision of miniscrew placement.

5. Discussion

The insertion site for orthodontic miniscrews is influenced by several clinical factors, including the direction of intended tooth movement, anchorage requirements, and anatomical limitations. Although the anterior palate is a commonly preferred site due to its favorable bone quality and thickness, several studies have highlighted its high anatomical variability. For this reason, a preliminary evaluation using cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) is strongly recommended to ensure accurate and safe placement—particularly in cases involving impacted teeth or narrow maxillary arches.[

7,

8,

9,

10]

The use of 3D-printed surgical guides has been proposed to enhance the accuracy and reproducibility of miniscrew insertion. Numerous authors have compared traditional free-hand placement with guided insertion using 3D templates, reporting significantly better outcomes in terms of angular and linear deviations when surgical guides are employed. [

11,

12,

13]

These guides have proven effective not only in palatal insertions but also in more challenging anatomical regions such as the infra zygomatic crest and interradicular space.[

11,

14]

Quantitative assessments using pre- and postoperative CBCT scans have confirmed the improved precision of guided insertion techniques, reducing the risk of iatrogenic damage to adjacent roots or the maxillary sinus. [

13,

15]

Two different studies conducted on cadaver [

16] and phantom [

17] showed that miniscrew-assisted placement with a surgical guide is more accurate compared to free-hand placement for both angular deviation and mesiodistal deviation in the coronal and apical miniscrew areas. [

16,

17]

A recent study by Pozzan et al. [

12], analyzed the accuracy of palatal miniscrew placement under a digital workflow, assessing errors at multiple stages: from virtual planning to laboratory model fabrication and clinical insertion. They highlighted how even small deviations in the lab phase (mean angular error ~2.12°) could contribute to cumulative inaccuracies that compromise the final clinical outcome, particularly in protocols requiring high insertion precision.

Discrepancies between planned and achieved miniscrew positions may result from several factors, including patient-specific bone morphology, operator experience, and procedural inconsistencies.

Although digital scanners have demonstrated high reliability in the literature [

20], operator skill and environmental conditions can still affect scan accuracy. Therefore, standardized protocols and precise execution of each step in the digital workflow are essential to optimize outcomes.

In the context of single-visit protocols, accurate digital planning followed by predrilling using a surgical guide ensures optimal screw angulation and minimizes undercuts. This facilitates the insertion of TADs and the immediate fit of orthodontic appliances, ultimately reducing chair time and enhancing clinical efficiency. [

21]

The present study aimed to evaluate the real-world accuracy of 3D-printed surgical guides for palatal miniscrew insertion by comparing the digitally planned position with the actual postoperative outcome. Through the superimposition of STL models from the planning phase and the final clinical scan, discrepancies in insertion angle and spatial deviation at both the screw head and tip were measured.

Results revealed greater horizontal and vertical discrepancies at the tip than at the head, consistent with the geometric amplification of angular deviations over distance. The mean angular deviation between the planned and final screw insertion axes was 2,95 ° (SD +/- 1.13 °)which is lower than that reported by Pozzan et al. (5.7° ± 3.42°), possibly due to the exclusion of the laboratory-derived error in the current workflow. These findings underscore the clinical relevance of each step in the digital protocol and reinforce the value of surgical guides in improving insertion precision.

6. Conclusions

The use of 3D-printed surgical guides for palatal miniscrew insertion resulted in a mean angular deviation of 2,95 ° (SD +/- 1.13 °)demonstrating a clear improvement in placement accuracy over free-hand techniques. However, even small apex-level discrepancies may compromise the efficacy of single-visit protocols, in which miniscrew insertion and appliance attachment are completed in the same appointment.

Guided insertion proved particularly beneficial in anatomically challenging scenarios—such as narrow palatal vaults, transverse maxillary dysplasia, impacted teeth, or infra zygomatic sites—by reducing the risk of root or nasal cavity perforation.

An integrated digital–laboratory workflow combining CBCT-based planning, intra-oral scanning, and the use of scan-bodies enables precise registration of miniscrew positions for the fabrication of customized palatal appliances. This approach obviates the need for conventional impressions, enhances patient comfort, and streamlines clinical procedures.

To further reduce cumulative errors, clinicians should rigorously standardize each step of the digital workflow (imaging, planning, guide fabrication, and insertion) and undertake dedicated training in 3D-planning software and guided-surgery protocols. A pre-operative CBCT is recommended in cases of limited bone volume or complex anatomy to verify the planned trajectory.

Prospective, randomized comparisons of different guided systems are now warranted to confirm these findings and optimize single-visit protocols for palatal miniscrew placement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization; A. M. B., E. C., S. B. Data curation; A. M. B., E. C., S. B., Formal analysis; A. M. B., E. C., S. B., D.A. Funding acquisition; A. M. B., E. C., S. B., D.A. Investigation; A. M. B., E. C., S. B., D.A. Methodology; A. M. B., E. C., S. B., D.A. Project administration; D.A.., R. N. Resources; A. M. B., E. C., S. B., D.A., R. N. Software; D.A.R. N. Supervision; D.A., R. N. Validation; D.A., R. N. Visualization; D.A., R. N. Roles/Writing -original draft; A. M., D.A., R. N. Writing – review, and editing, A. M. B, D.A., R. N.

Funding

This work has been partially supported by the European Union (NextGeneration EU), through the MUR-PNRR project SAMOTHRACE (ECS00000022). Dr. Angela Mirea Bellocchio, the corresponding manuscript’s author, is funded by a research grant for her research activities.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study proposal received joint approval by the Ethics Committee Messina (prot. 33-2020).

Data Availability Statement

All raw data are publicly available. Previously asking.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

References

- Wehrbein, H. , Glatzmaier, J., Mundwiller, U., & Diedrich, P. (1996). The Orthosystem--a new implant system for orthodontic anchorage in the palate. J Orofac Orthop, 57, 142-153.

- Di Leonardo, B. , Ludwig, B., Lisson, J. A., Contardo, L., Mura, R., & Hourfar, J. (2018). Insertion torque values and success rates for paramedian insertion of orthodontic mini-implants : A retrospective study. J Orofac Orthop, 79, 109-115.

- Faegheh, G.; Khosravifard, N.; Maleki, D.; Hosseini, S.K. Evaluation of Palatal Bone Thickness and Its Relationship with Palatal Vault Depth for Mini-Implant Insertion Using Cone Beam Computed Tomography Images. Turk. J. Orthod. 2022, 35, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nucera, R.; Costa, S.; Bellocchio, A.M.; Barbera, S.; Drago, S.; Silvestrini, A.; Migliorati, M. Evaluation of palatal bone depth, cortical bone, and mucosa thickness for optimal orthodontic miniscrew placement performed according to the third palatal ruga clinical reference. Eur. J. Orthod. 2022, 44, 530–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Riofrío, D.; Viñas, M.J.; Ustrell-Torrent, J.M. CBCT and CAD-CAM technology to design a minimally invasive maxillary expander. BMC Oral Heal. 2020, 20, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiello, D.; Nucera, R.; Costa, S.; Figliuzzi, M.M.; Paduano, S. A Simplified Digital Approach to the Treatment of a Postpuberty Patient with a Class III Malocclusion and Bilateral Crossbite. Case Rep. Dent. 2021, 2021, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumgaertel, S. Quantitative investigation of palatal bone depth and cortical bone thickness for mini-implant placement in adults. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2009, 136, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hourfar, J.; Ludwig, B.; Bister, D.; Braun, A.; Kanavakis, G. The most distal palatal ruga for placement of orthodontic mini-implants. Eur. J. Orthod. 2014, 37, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nucera, R.; Ciancio, E.; Maino, G.; Barbera, S.; Imbesi, E.; Bellocchio, A.M. Evaluation of bone depth, cortical bone, and mucosa thickness of palatal posterior supra-alveolar insertion site for miniscrew placement. Prog. Orthod. 2022, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maino, B. G. , Paoletto, E., Lombardo, L., 3rd, & Siciliani, G. (2016). A Three-Dimensional Digital Insertion Guide for Palatal Miniscrew Placement. J Clin Orthod, 50, 12-22.

- Su, L.; Song, H.; Huang, X. Accuracy of two orthodontic mini-implant templates in the infrazygomatic crest zone: a prospective cohort study. BMC Oral Heal. 2022, 22, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozzan, L.; Migliorati, M.; Dinelli, L.; Riatti, R.; Torelli, L.; Di Lenarda, R.; Contardo, L. Accuracy of the digital workflow for guided insertion of orthodontic palatal TADs: a step-by-step 3D analysis. Prog. Orthod. 2022, 23, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilmes, B.; Vasudavan, S.; Drescher, D. CAD-CAM–fabricated mini-implant insertion guides for the delivery of a distalization appliance in a single appointment. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2019, 156, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.C.; Huang, J.-N.; Zhao, S.-F.; Xu, X.-J.; Xie, Z.-J. Radiographic and surgical template for placement of orthodontic microimplants in interradicular areas: a technical note. . 2006, 21, 629–34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cantarella, D.; Savio, G.; Grigolato, L.; Zanata, P.; Berveglieri, C.; Giudice, A.L.; Isola, G.; Del Fabbro, M.; Moon, W. A New Methodology for the Digital Planning of Micro-Implant-Supported Maxillary Skeletal Expansion. Med Devices: Évid. Res. 13. [CrossRef]

- Bae, M.-J.; Kim, J.-Y.; Park, J.-T.; Cha, J.-Y.; Kim, H.-J.; Yu, H.-S.; Hwang, C.-J. Accuracy of miniscrew surgical guides assessed from cone-beam computed tomography and digital models. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2013, 143, 893–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, L.; Haruyama, N.; Suzuki, S.; Yamada, D.; Obayashi, N.; Kurabayashi, T.; Moriyama, K. Accuracy of orthodontic miniscrew implantation guided by stereolithographic surgical stent based on cone-beam CT–derived 3D images. Angle Orthod. 2012, 82, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melo, A.C.M.; Andrighetto, A.R.; Hirt, S.D.; Bongiolo, A.L.M.; Silva, S.U.; da Silva, M.A.D. Risk factors associated with the failure of miniscrews - A ten-year cross sectional study. Braz. Oral Res. 2016, 30, e124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crismani, A.G.; Bertl, M.H.; Čelar, A.G.; Bantleon, H.-P.; Burstone, C.J. Miniscrews in orthodontic treatment: Review and analysis of published clinical trials. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2010, 137, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoetzer, M. , Wagner, M. E., Wenzel, D., Lindhorst, D., Gellrich, N. C., & von See, C. (2014). Nonradiological method for 3-dimensional implant position assessment using an intraoral scan: new method for postoperative implant control. Implant Dent, 23, 612-616.

- Maino, B.G.; Paoletto, E.; Cremonini, F.; Liou, E.; Lombardo, L. Tandem Skeletal Expander and MAPA Protocol for Palatal Expansion in Adults. . 2020, 54, 690–704. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).