4. Discussion

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations (COPDe) are acute clinical events defined by a sudden and sustained worsening of respiratory symptoms, such as increased dyspnea, cough, and sputum production, in patients with an established history of COPD, often linked to a significant smoking background. These exacerbations contribute substantially to healthcare utilization, with frequent emergency department visits, hospital admissions, and increased morbidity and mortality. The clinical course of a COPDe can be further complicated by the development of acute kidney injury (AKI), an increasingly recognized comorbidity that adversely affects patient outcomes. AKI, which may arise due to hypoperfusion, nephrotoxic medications, or systemic inflammation, has been associated with increased mortality and prolonged recovery in various hospitalized populations, including those with pulmonary disease. Identifying AKI in the context of COPDe can serve as an important prognostic marker and may influence the aggressiveness of inpatient management.

In this retrospective cohort study, we sought to investigate the incidence and prevalence of AKI in patients hospitalized with COPDe and to evaluate its impact on key clinical outcomes, including inpatient mortality and hospital length of stay (LOS), in comparison to patients hospitalized with COPDe alone. The study population included adults aged 35 and older with a documented history of cigarette smoking and a confirmed diagnosis of COPD. Patients were categorized into two groups based on whether they developed AKI either at the time of admission or during the course of hospitalization.

To ensure a focused analysis, several exclusion criteria were applied, including patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), acute heart failure exacerbation, ongoing urinary tract infection (UTI), myocardial infarction, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, and those with a concurrent COVID-19 diagnosis. These conditions were excluded due to their potential to confound the clinical picture and independently contribute to kidney injury or mortality.

The study’s findings revealed that patients who developed AKI during hospitalization for COPDe exhibited markedly worse clinical outcomes compared to those without AKI. Significant differences were observed in demographic profiles, presence of comorbidities, complexity of hospital course, longer LOS, and notably, higher inpatient mortality rates. These results suggest that AKI serves not only as a complication but also as a potential marker of disease severity in the setting of COPD exacerbations.

Given these findings, early identification of patients at risk for AKI upon hospital admission may allow for more targeted interventions, including closer hemodynamic monitoring, judicious use of nephrotoxic medications, and timely nephrology consultation. Furthermore, these insights can aid in risk stratification, inform prognosis, and support the development of multidisciplinary care strategies aimed at improving outcomes in this high-risk population.

Our analysis revealed notable demographic differences between COPD patients with and without concomitant AKI. One key finding was the significant age difference between the two groups. Patients with AKI were generally older than those without, with a mean age of 72.69 ± 10.29 years compared to 69.55 ± 10.84 years in the non-AKI group (p = 0.01). This association may be explained by age-related declines in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), underscoring advanced age as a significant risk factor for AKI in patients with COPD, as shown by Singh et al. [

6]. In addition, older patients are more likely to have pre-existing chronic kidney disease (CKD), which may result from underlying conditions such as renal artery disease, diabetic nephropathy, or longstanding hypertension—all of which increase susceptibility to AKI during hospitalization.

In addition to age, differences in sex and ethnicity were also observed. Females were found in lower proportion in the AKI group compared to the non-AKI group. This disparity may be attributed to several factors, including the protective effects of estrogen on both cardiovascular and renal function, which may help reduce the severity or incidence of AKI. Moreover, females generally have a lower prevalence of comorbid conditions such as coronary artery disease and chronic kidney disease. They are also more likely to seek medical attention earlier and adhere more consistently to treatment regimens, which can lead to improved management of both COPD and its complications, including AKI [

7,

8,

9].

White patients were also found in lower proportion in the AKI group compared to the non-AKI group. This observation may suggest a lower incidence of kidney injury in this population. In contrast, Black and Hispanic patients were represented in greater proportion within the AKI group. These demographic differences raise important questions about racial and ethnic susceptibilities to AKI in the setting of COPD, warranting further investigation [

7,

9]. Grams et al. [

10] suggest that socioeconomic disparities such as differences in income, education level, and insurance coverage may influence access to preventive care and timely medical interventions, potentially contributing to this trend.

As expected, patients with AKI exhibited a significantly higher prevalence of comorbidities compared to those without AKI. Hypertension was the most common condition, affecting 84.3% of patients in the AKI group versus 72.4% in the non-AKI group. Similarly, the rates of diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia were also notably higher among patients with AKI. These findings align with established literature and can be explained by several pathophysiological mechanisms. Hypertension is a well-known risk factor for AKI, as it can result in chronic kidney damage and reduced renal reserve, thereby increasing vulnerability to acute renal insults [

11]. Diabetes mellitus, likewise, more prevalent in the AKI group, contributes to AKI risk through its deleterious effects on microvascular integrity and its association with diabetic nephropathy [

11,

12]. Dyslipidemia, through its role in promoting atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease, can impair renal perfusion and further exacerbate kidney injury [

13].

Given that chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a well-established risk factor for the development of AKI, Singh et al. [

7] demonstrated a clear link between CKD stages 3–4 and increased AKI risk. It is therefore not surprising that CKD stage 3–4 was notably more prevalent among patients with AKI. In addition to CKD, other comorbid conditions, including coronary artery disease (CAD), obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), cerebrovascular disease (CVD), and pulmonary hypertension, were also more commonly seen in the AKI group. Interestingly, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) was slightly less prevalent among patients with AKI. The presence of these comorbidities likely compounds physiological stress during a COPD exacerbation, increasing the risk for renal injury. These findings underscore the importance of comprehensive and proactive management of chronic comorbid conditions to reduce the risk of AKI and improve overall patient outcomes.

Patients hospitalized for COPD exacerbations often require advanced respiratory support to stabilize their oxygenation status, including high-flow nasal cannula, noninvasive ventilation (NIV), or mechanical ventilation. These interventions may prolong hospitalization, particularly when complications such as AKI arise. Our analysis revealed that patients who developed AKI during hospitalization for COPD exacerbation had significantly longer lengths of stay (LOS), with a mean LOS of 6 days compared to 4 days for those without AKI. In a study by Zhang et al. [

14], patients with acute COPD exacerbation complicated by AKI had substantially longer hospital stays (13 days vs. 10 days) and significantly higher in-hospital mortality (18.0% vs. 2.7%) than those without AKI.

These findings further emphasize the importance of early intervention to optimize oxygenation and avoid clinical deterioration. The extended LOS observed in the AKI group may be attributed to several factors, including respiratory failure, the need for close monitoring of fluid balance, correction of electrolyte abnormalities, and impaired metabolic compensation for respiratory acidosis. Identifying patients at higher risk for AKI and initiating timely, targeted interventions may help reduce hospitalization duration and improve survival.

Our data supports that patients who developed AKI during COPD exacerbations experienced significantly higher inpatient mortality compared to those without AKI (5.8% vs. 1.6%). The elevated mortality in this population is likely multifactorial, though several mechanisms are supported by existing literature. One proposed explanation involves impaired metabolic compensation for respiratory acidosis. As shown by Marcy et al. [

15], AKI diminishes the kidneys’ ability to retain bicarbonate, a key buffer against elevated carbon dioxide levels in COPD patients. This impairment can worsen respiratory acidosis and lead to acute respiratory failure, requiring escalated oxygen support and increasing the risk of mortality. Our data supports this association, as patients with AKI experienced higher rates of acute respiratory failure (58.4% vs. 51.7%) and a greater need for intubation (10.7% vs. 3.9%). Chen et al. further demonstrated that the interaction between acute respiratory failure and AKI synergistically increases the risk of in-hospital mortality in patients with COPD exacerbations, emphasizing the importance of managing both complications concurrently [

8].

AKI is also associated with fluid overload and electrolyte abnormalities, particularly hyperkalemia and hyponatremia. Hyperkalemia may lead to serious electrophysiological disturbances, including bradyarrhythmia and potentially fatal cardiac arrhythmias. In severe cases, this can precipitate cardiac arrest and necessitate immediate intervention with mechanical ventilation and vasopressor support [

16]. Hyponatremia, especially when rapidly fluctuating, can contribute to cerebral edema and neurological impairment. This, in turn, may lead to respiratory muscle weakness, precipitating acute respiratory failure and the need for ventilatory support.

Additionally, the presence of AKI in COPD patients can amplify systemic inflammation and oxidative stress. Elevated levels of inflammatory markers such as high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) have been associated with poor prognosis in this cohort [

17,

18]. This pro-inflammatory state increases the risk of multi-organ dysfunction, further worsening patient outcomes.

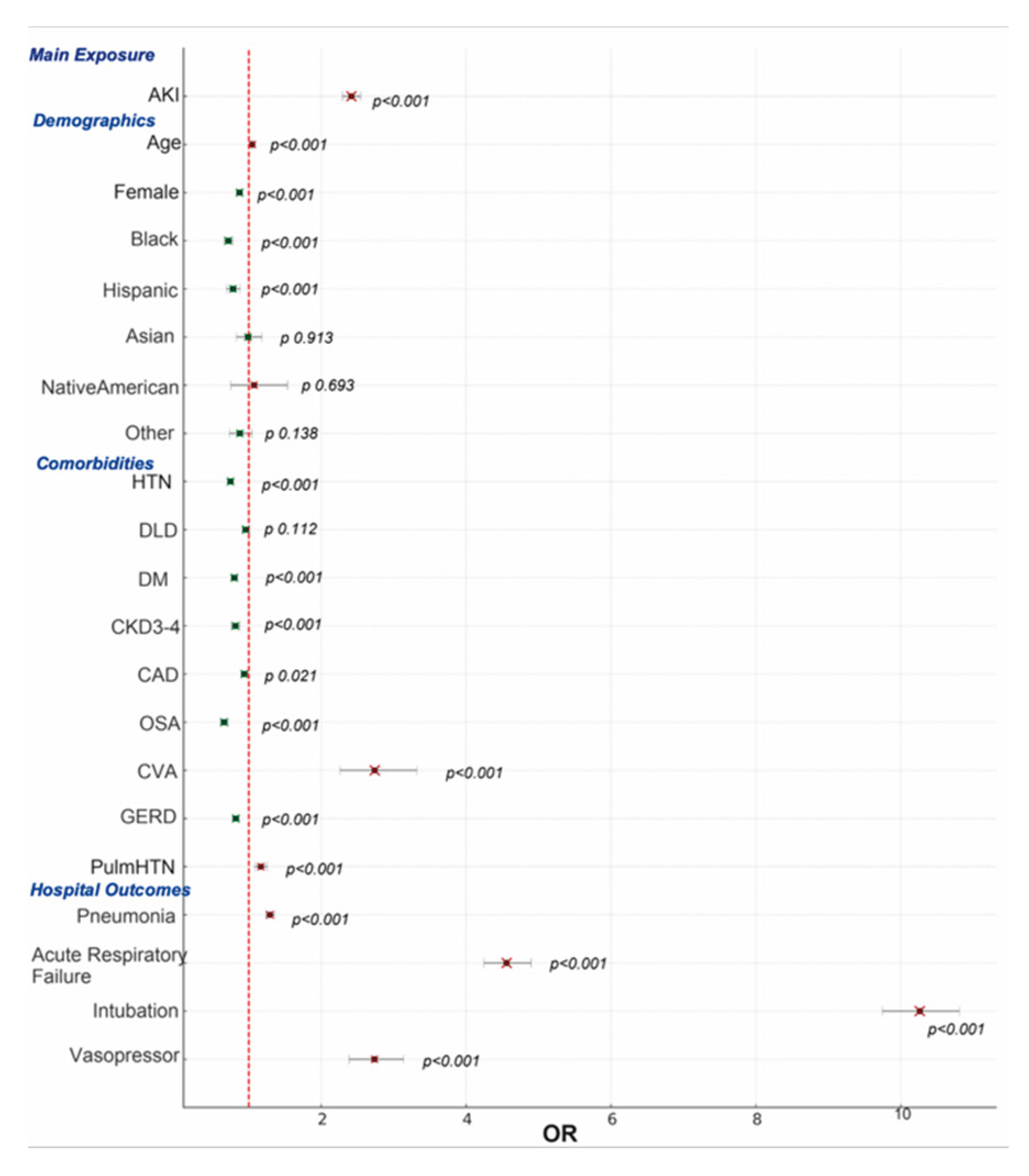

To further explore predictors of mortality, a multivariate analysis was conducted. The findings indicated that intubation carried the highest risk of mortality, followed by vasopressor use, both of which strongly correlate with the severity of respiratory failure. Vieira et al. found that the presence of AKI was associated with delayed weaning from mechanical ventilation in critically ill patients, potentially prolonging hospital stay and increasing complication rates [

18].Faubel and Edelstein [

19] demonstrated that AKI contributes to respiratory failure through systemic inflammation and immune dysregulation, which can lead to multi-organ dysfunction, including lung injury. Legrand and Rossignol [

20] further highlighted the role of increased vascular permeability and pulmonary edema due to AKI. In patients requiring mechanical ventilation, careful management of fluid status and electrolyte balance becomes critical. In severe AKI cases, renal replacement therapy (RRT) may be necessary, which introduces further complexity, including hemodynamic instability that often requires vasopressor support. These overlapping processes create a vicious cycle of AKI and respiratory failure, leading to prolonged mechanical ventilation, challenges in weaning, and increased mortality risk. In addition to its acute consequences, AKI has been shown to contribute to the progression of chronic kidney disease, highlighting the need for long-term renal monitoring in COPD patients who experience AKI during hospitalization [

12].

Cerebrovascular disease (CVD) also emerged as a major mortality risk factor. The relationship between CVD and AKI is complex and bidirectional. CVD can precipitate AKI through mechanisms such as hypoperfusion during stroke or cardiogenic shock. Additionally, the use of contrast agents in imaging can cause contrast-induced nephropathy, as described by Modi et al. [

19]. Conversely, Albeladi et al. [

20] demonstrated that AKI is associated with increased risk of future cerebrovascular events due to inflammation, atherosclerosis, and endothelial dysfunction. Shared risk factors including hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia likely contribute to the co-occurrence of these conditions.

Pulmonary hypertension was another significant risk factor. It is defined by a mean pulmonary artery pressure of ≥25 mm Hg at rest, as established in guidelines by Galiè et al. [

21]. Kidney dysfunction is frequently observed in patients with pulmonary hypertension and serves as an independent predictor of mortality. Nickel et al. [

22] proposed mechanisms linking pulmonary hypertension to AKI, including increased venous congestion, decreased cardiac output, and neurohormonal activation. AKI may exacerbate cardiovascular strain and systemic inflammation, both of which are associated with poorer prognosis in critically ill patients, as described by Legrand and Rossignol [

17].

Notably, the detrimental impact of AKI is not limited to acute exacerbations of COPD; Wang et al. [

23] found that even among patients hospitalized with stable, non-exacerbated COPD, the presence of AKI independently predicted increased in-hospital mortality and prolonged hospitalization. This finding reinforces the critical role of renal function in determining outcomes across the full spectrum of COPD severity. Similarly, Barakat et al. found that the presence of AKI was associated with increased morbidity and mortality in both stable COPD and during exacerbations, further emphasizing the critical role of renal function across the COPD spectrum [

9].

Interestingly, despite being more prevalent in the AKI group, comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes were associated with lower mortality. Similarly, CKD stage 3–4, OSA, and GERD were linked to reduced mortality, and CAD showed a modest protective effect. Dyslipidemia showed no significant impact on mortality. These findings may reflect the protective effects of certain medications, such as ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and SGLT2 inhibitors, commonly prescribed in patients with hypertension, diabetes, and CAD. These agents have demonstrated both renal and mortality benefits, as reported by Cardoso et al. [

24] and van Vark et al. [

25], which may explain the observed decrease in mortality risk.

Another unexpected finding was the lower mortality risk among Black and Hispanic patients compared to White patients. Although Black and Hispanic patients were more likely to develop AKI, their overall mortality was lower. Kabarriti et al. [

26] suggest that these groups often have higher rates of hypertension and diabetes, leading to more frequent use of renoprotective therapies with known mortality benefits. Thus, increased exposure to these medications may help mitigate the elevated mortality risk typically associated with AKI.

As a retrospective study, this analysis has several limitations. While it identifies associations between AKI and mortality in COPD exacerbations, it does not establish causality. Determining the temporal sequence of clinical events is difficult in retrospective datasets, and coding inaccuracies may confound the findings. The lack of longitudinal follow-up data also limits the ability to assess long-term outcomes and refine risk stratification tools. Additionally, potential selection and confounding biases may limit the generalizability of results to the broader COPD population.

Future research should focus on prospective, longitudinal studies to better characterize the temporal and causal relationships between AKI and outcomes in COPD exacerbations. Such studies should incorporate detailed clinical and biochemical data to improve risk prediction models and identify modifiable risk factors. Further exploration into the protective effects of commonly used medications could provide valuable insights into optimizing therapy. Additionally, addressing demographic disparities potentially driven by socioeconomic factors, comorbidity burden, and access to care will be critical for improving outcomes in vulnerable patient populations.