Submitted:

27 May 2025

Posted:

28 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. System Model

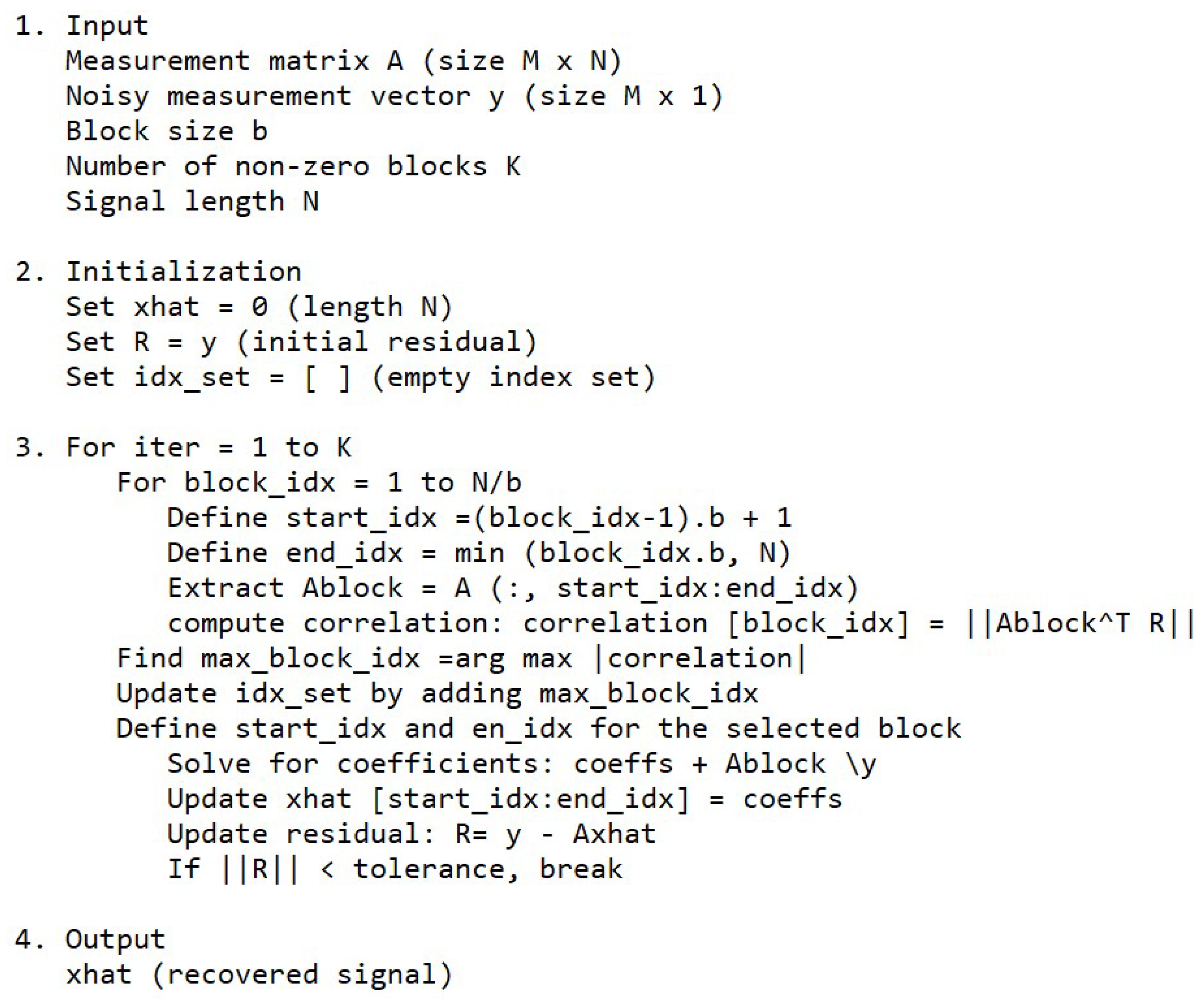

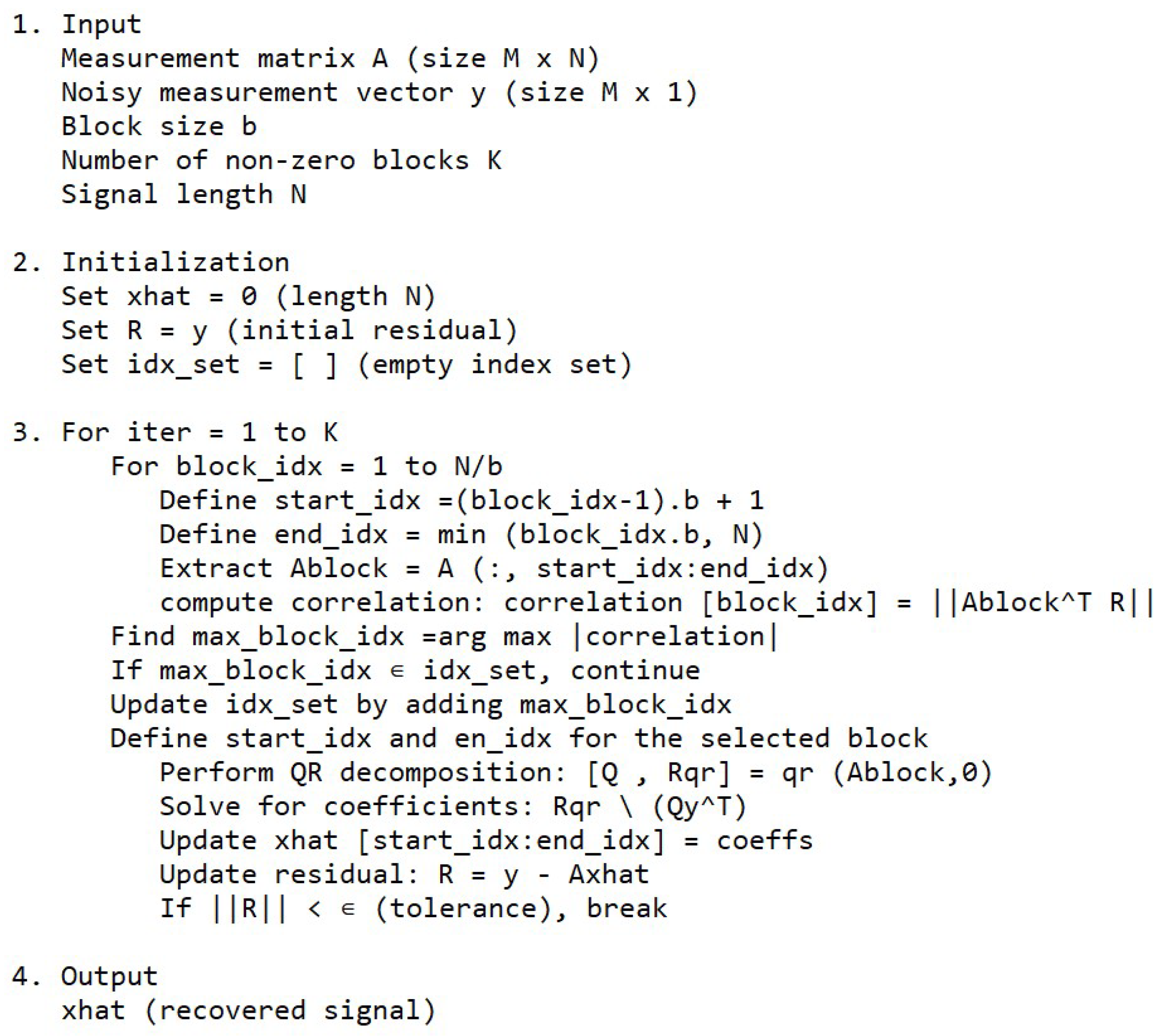

2.2. Methodology

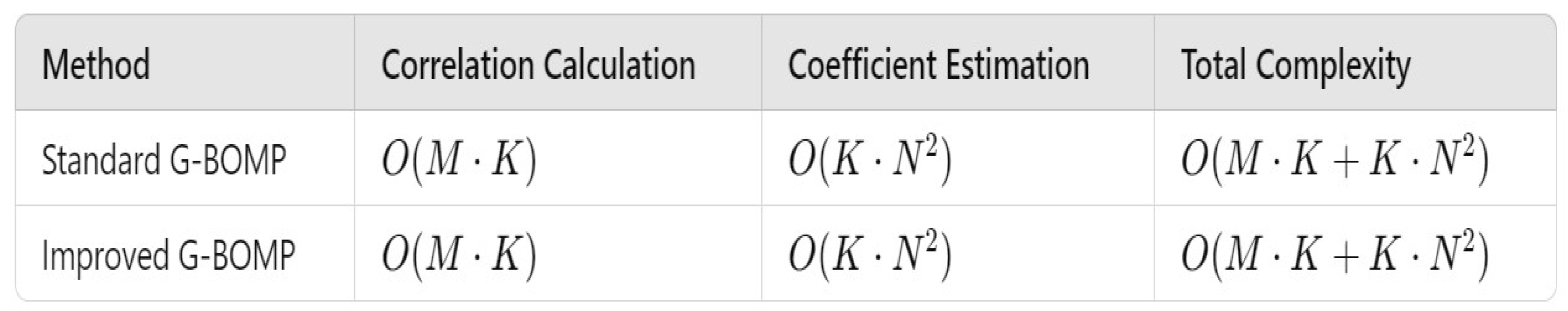

2.3. Computational Complexity

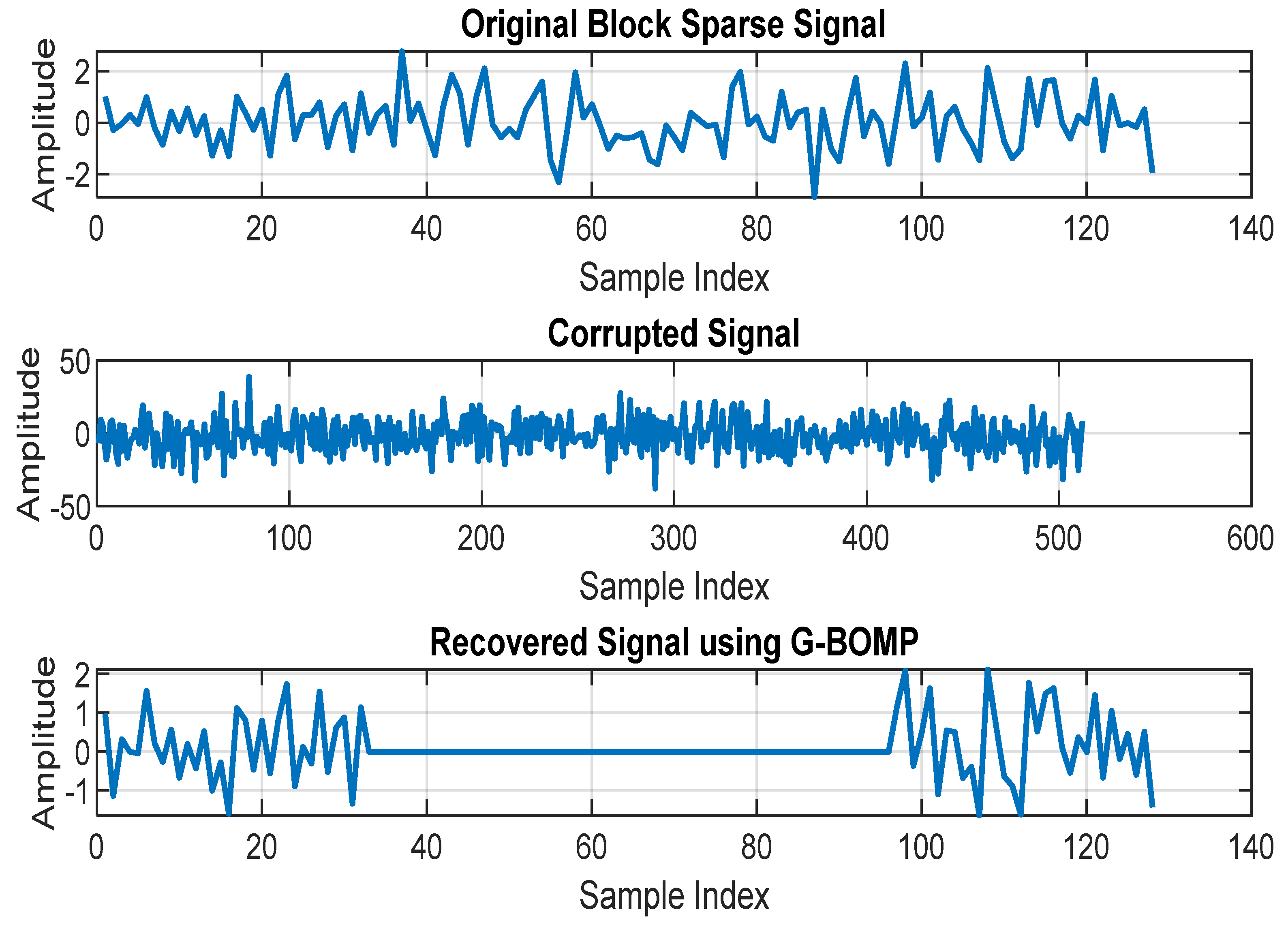

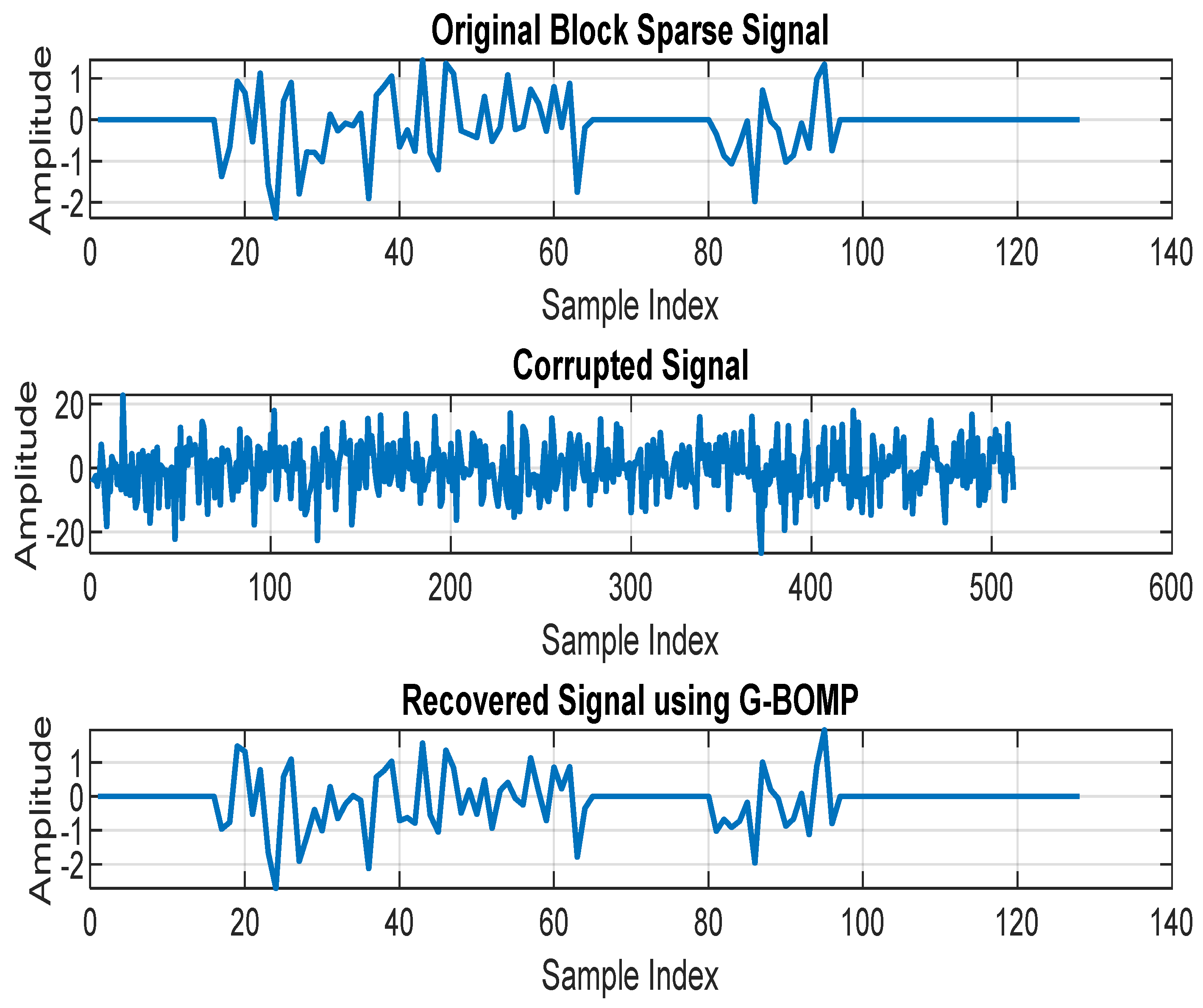

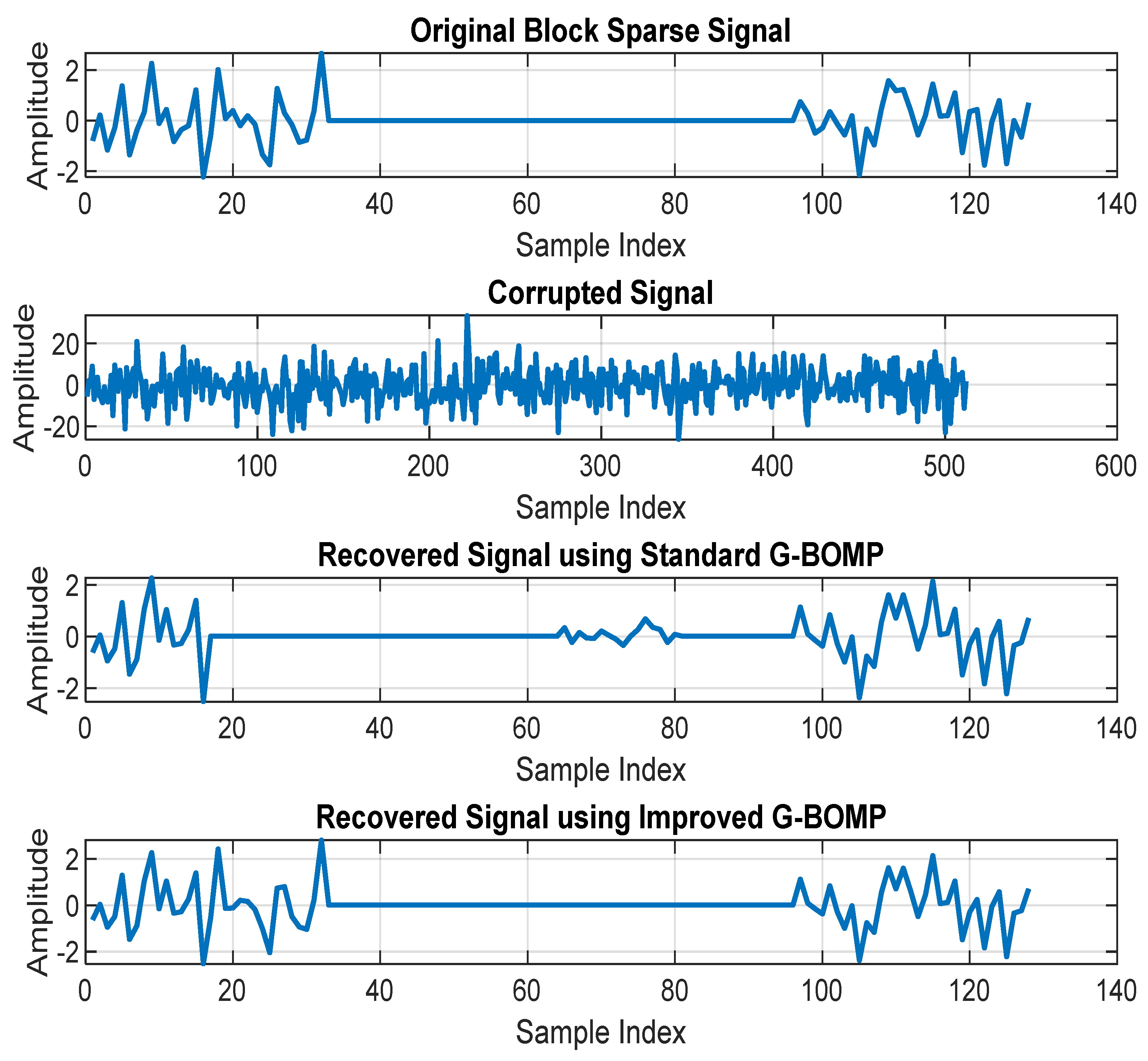

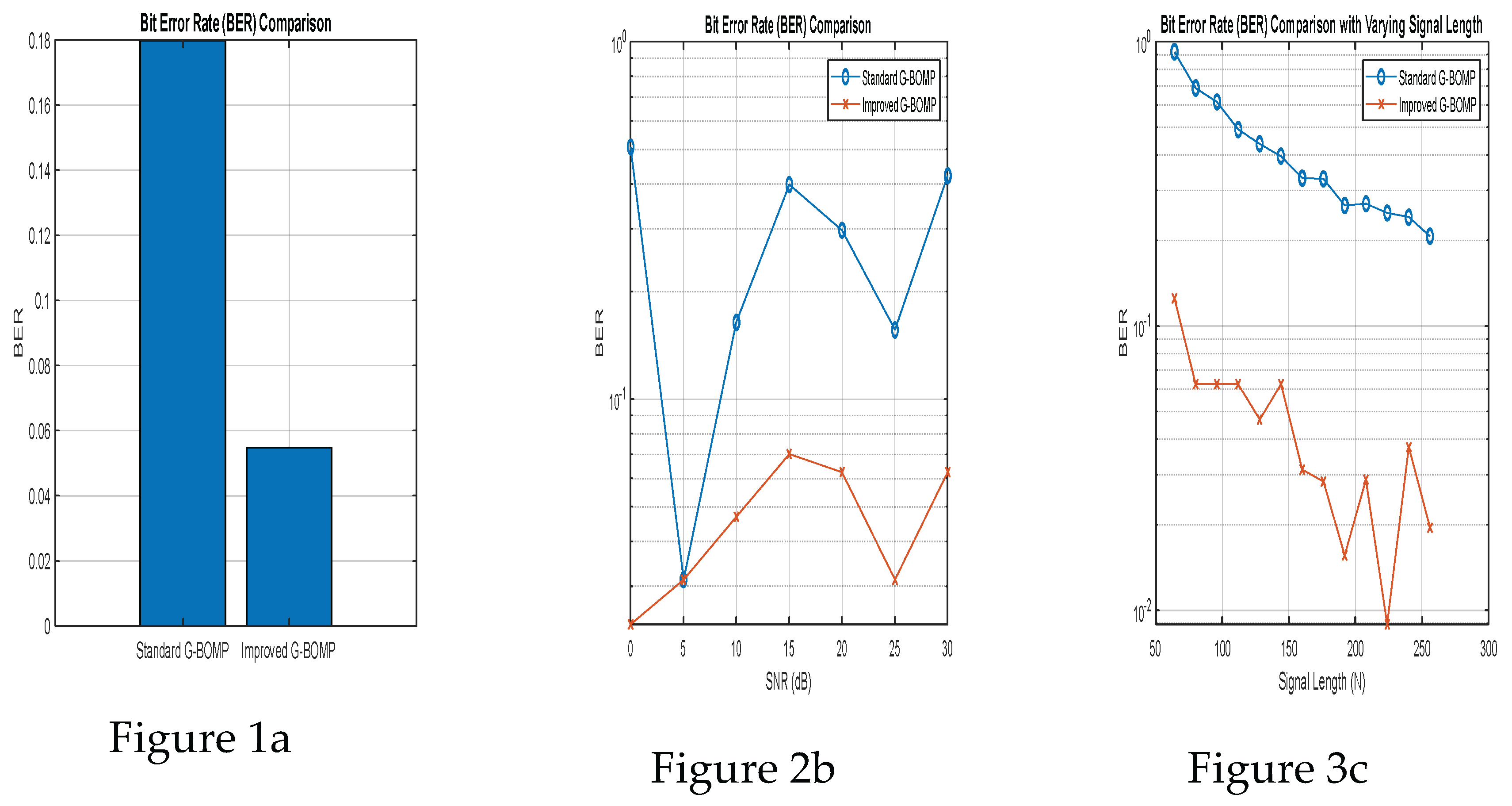

3. Results

6. Conclusion

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- D. L. Donoho, “Compressed sensing,” IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory, vol. 52, no. 4, pp. 1289–1306, 2006. [CrossRef]

- E. J. Candès, J. Romberg, and T. Tao, “Robust uncertainty principles: Exact signal reconstruction from highly incomplete frequency information,” IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory, vol. 52, no. 2, pp. 489–509, 2006. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Tropp and A. C. Gilbert, “Signal recovery from random measurements via orthogonal matching pursuit,” IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory, vol. 53, no. 12, pp. 4655–4666, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, M. Liu, and J. Huang, “Block sparse signal recovery with block sparsity constraints,” IEEE Trans. Signal Process., vol. 61, no. 12, pp. 3165–3177, 2013. [CrossRef]

- D. Needell, R. Vershynin, and J. A. Tropp, “Uniform recovery of sparse signals via convex programming,” Found. Comput. Math., vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 459–493, 2013. [CrossRef]

- X. Chen, Y. Yang, and Y. Liu, “Adaptive block sparse recovery via generalized orthogonal matching pursuit,” Signal Process., vol. 143, pp. 252–260, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Q. Wu, Y. Jiang, and X. Huang, “Improved generalized block orthogonal matching pursuit for sparse signal recovery,” IEEE Signal Process. Lett., vol. 27, pp. 951–955, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. L. Bertozzi, A. Bressan, and S. Cattaneo, “Machine learning techniques for signal recovery,” IEEE Trans. Signal Process., vol. 69, pp. 256–269, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Palangi et al., “Deep learning-enhanced block sparse recovery for image signals,” IEEE Trans. Image Process., vol. 31, pp. 512–525, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang et al., “Reinforcement learning for dynamic block selection in 5G channel estimation,” IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun., vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 1459–1473, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Nguyen et al., “Transformer-based compressive sensing with adversarial robustness,” Signal Process., vol. 198, 108567, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Wu et al., “Truncated SVD-BOMP for MRI reconstruction,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging, vol. 41, no. 5, pp. 1123–1136, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Karami and M. Naraghi, “LU factorization with iterative reweighting for ill-conditioned systems,” IEEE Trans. Signal Process., vol. 70, pp. 3450–3463, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Gupta et al., “FPGA implementation of QR decomposition for block sparse recovery,” IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I, vol. 69, no. 8, pp. 3012–3025, 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Chen et al., “Kalman-filter-integrated G-BOMP for radar signal tracking,” IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst., vol. 58, no. 3, pp. 1892–1905, 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Al-Jawad et al., “Distributed G-BOMP for IoT sensor networks,” IEEE Internet Things J., vol. 9, no. 15, pp. 13245–13258, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liang et al., “FPGA-accelerated QR-G-BOMP for millimeter-wave communications,” IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. Syst., vol. 30, no. 6, pp. 789–801, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Park et al., “GPU-optimized BOMP for video compressive sensing,” IEEE Trans. Multimedia, vol. 24, pp. 3210–3223, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Mishra et al., “Block-RIP guarantees for heavy-tailed measurement matrices,” IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory, vol. 68, no. 7, pp. 4567–4580, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Bahmani and P. T. Boufounos, “Linear convergence of G-BOMP under tree-sparse correlations,” IEEE Trans. Signal Process., vol. 70, pp. 112–125, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Guo et al., “G-BOMP with anatomical priors for accelerated MRI,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng., vol. 69, no. 9, pp. 2789–2798, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Rahman et al., “Quantized G-BOMP for massive MIMO channel estimation,” IEEE Trans. Commun., vol. 70, no. 10, pp. 6543–6556, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Awan et al., “Energy-efficient BOMP for wearable EEG sensors,” IEEE Sensors J., vol. 22, no. 18, pp. 17645–17655, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Singh et al., “Wavelet-denoised G-BOMP for underwater acoustics,” IEEE J. Ocean. Eng., vol. 47, no. 4, pp. 987–1001, 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhou et al., “Hber loss for impulsive noise resilience in G-BOMP,” IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol., vol. 71, no. 7, pp. 7023–7036, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Tavakoli et al., “Multi-stage hybrid algorithms for SAR imaging,” IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens., vol. 60, pp. 1–15, 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. Li et al., “Bayesian generalized block OMP for medical diagnostics,” IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform., vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 789–801, 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Wang et al., “Deep reinforcement learning for adaptive block sparsity,” IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst., vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 123–135, 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Sharma et al., “Block sparsity in federated learning: A G-BOMP approach,” IEEE Trans. Signal Process., vol. 71, pp. 210–225, 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. Almeida et al., “Real-time G-BOMP for autonomous vehicle perception,” IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst., vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 1567–1580, 2023. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).