1. Introduction

Protein kinases regulate diverse signaling pathways that control cellular growth, differentiation, and immune function [

1,

2]. Dysregulation of kinase activity is a hallmark of many cancers, often driven by mutations or altered protein–protein interactions that perturb regulatory mechanisms [

3]. Among Src-family kinases (SFKs), Lyn plays a pivotal role in hematopoietic cells, modulating B cell receptor (BCR) signaling and influencing proliferation, apoptosis, and drug resistance [

4,

5]. Aberrant Lyn activation has been implicated in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and other hematologic malignancies [

6,

7]; yet, compared to prototypical SFKs like Src or Hck, Lyn remains structurally and dynamically understudied.

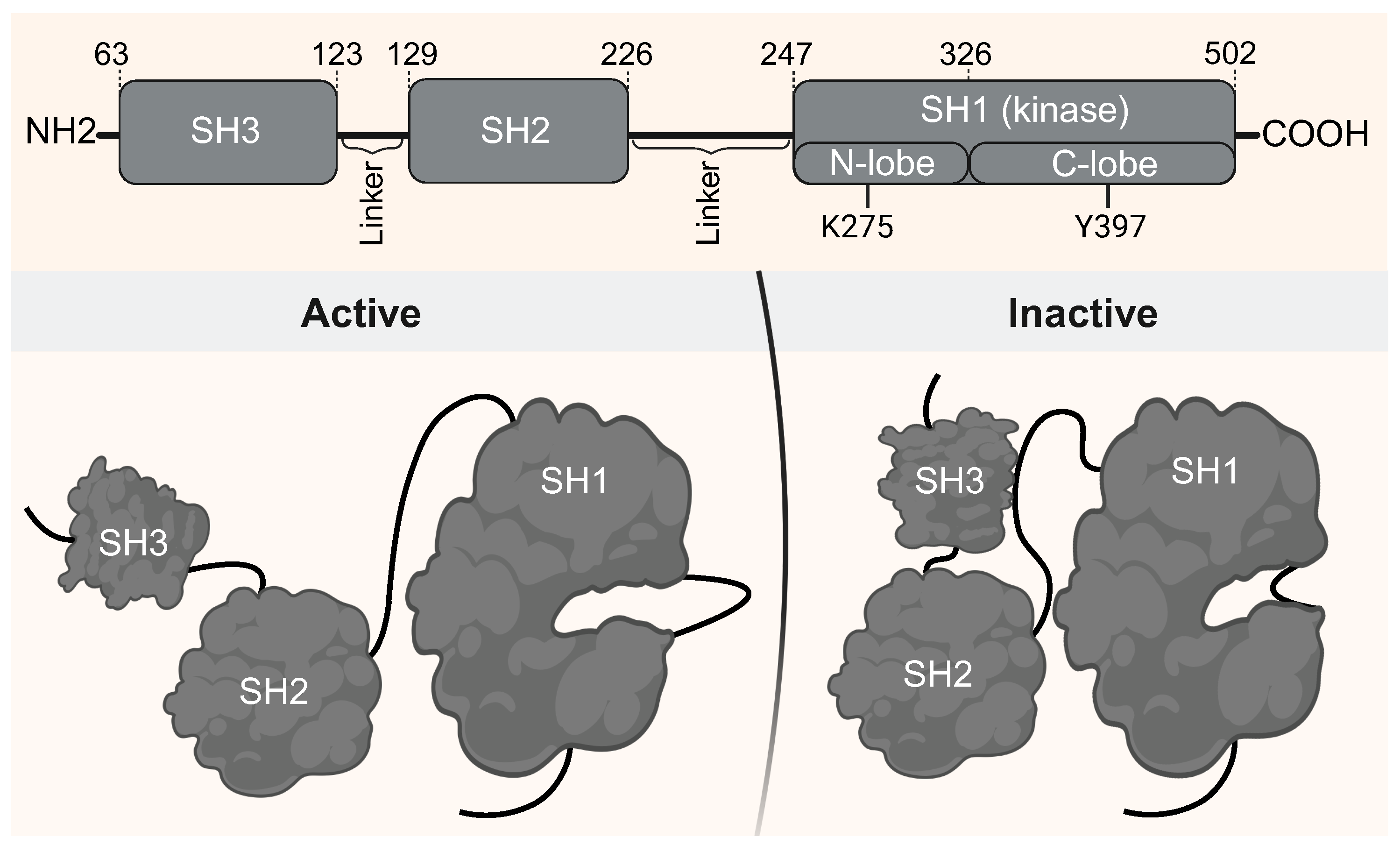

Figure 1 illustrates the domain architecture of Lyn kinase and highlights functionally relevant residues, emphasizing its modular SH3–SH2–SH1 arrangement. Most structural data for Lyn are limited to the SH1 domain, either in its apo form or bound to ATP competitive inhibitors such as dasatinib [

8]. Currently, no experimentally resolved structure includes all three domains [

9], limiting our understanding of interdomain regulation and impeding the rational design of domain-specific inhibitors. Additionally, Lyn’s dual role in both promoting and attenuating signaling further complicates its therapeutic targeting [

4,

10].

Conventional kinase inhibitors often target the conserved ATP-binding cleft, resulting in off-target effects and poor selectivity across SFKs [

11]. Allosteric modulation offers a promising alternative by targeting structurally distinct residues that regulate activity through long-range coupling [

9,

12]. However, identifying such regulatory hotspots requires full-length, dynamics-resolved models that static crystallography alone cannot provide. In this context, mapping allosteric hubs, residues embedded in dynamic networks and often located at interdomain interfaces, can offer mechanistic insight and reveal new opportunities for selective modulation.

Advances in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations allow the exploration of protein conformational landscapes at atomic resolution over relevant timescales [

13]. When integrated with principal component analysis (PCA), cross-correlation matrix (DCCM), and network-based methods, these approaches reveal dynamic couplings and functionally relevant communication pathways [

14,

15]. For multidomain kinases as Lyn, such tools are essential to link mutation, ligand binding, and long-range structural reorganization to regulatory outcomes.

In this study, we addressed these challenges by applying an integrative computational framework to characterize the full-length conformational landscape of Lyn kinase. We simulated the effects of ATP and dasatinib binding, as well as cancer-associated mutations, to investigate how these perturbations reshape domain flexibility, ATP-binding geometry, and long-range coupling. The SH3 and SH2 domains, often absent in structural studies, are explicitly modeled alongside SH1 to capture critical interdomain coordination. Using long-timescale MD simulations combined with PCA, DCCM, and residue-level network analysis, we identified dynamically embedded allosteric hubs and integration modules that govern signal propagation. A Random Forest (RF) classifier trained on structural and dynamic descriptors further quantifies key determinants of functional state, revealing that interdomain interactions are among the most discriminative features separating active- from inactive-like ensembles. Together, our findings establish a dynamic, network-informed framework for understanding Lyn regulation and provide an approach for context-specific modulation and structure-based targeting.

2. Results

To characterize the dynamic behavior of Lyn protein kinase in response to ligand binding and mutation, we performed classical MD simulations across 13 systems. These included the wildtype (WT) protein in its apo form, ATP-bound (WT-ATP), and dasatinib-bound (WT-DAS) systems, as well as five single-point mutants: K275A, E290D, E290K, I364L, and I364N, each simulated in both apo and ATP-bound conditions. All systems were simulated in three replicates for 2

s, yielding over 78

s of aggregate simulation time (Table S1). Mutations were selected based on functional relevance; K275A is a known catalytic mutant [

16], while E290D/K and I364L/N are naturally occurring variants identified in cancer types such as bladder urothelial carcinoma, stomach adenocarcinoma, and colorectal adenocarcinoma. Mutants I364L and I364N have been predicted to be oncogenic based on hotspot analyses in cancer genomics datasets [

17].

2.1. Global and Local Dynamics of Lyn Protein Across Domains

We focused our analysis on global conformational stability using root mean square deviation (RMSD), local residue flexibility using root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), and mutation- or ligand-induced domain level perturbations. Domain-resolved insights are presented for SH1, SH2, and SH3, with a focus on ATP-induced stabilization and mutation-specific dynamic signatures.

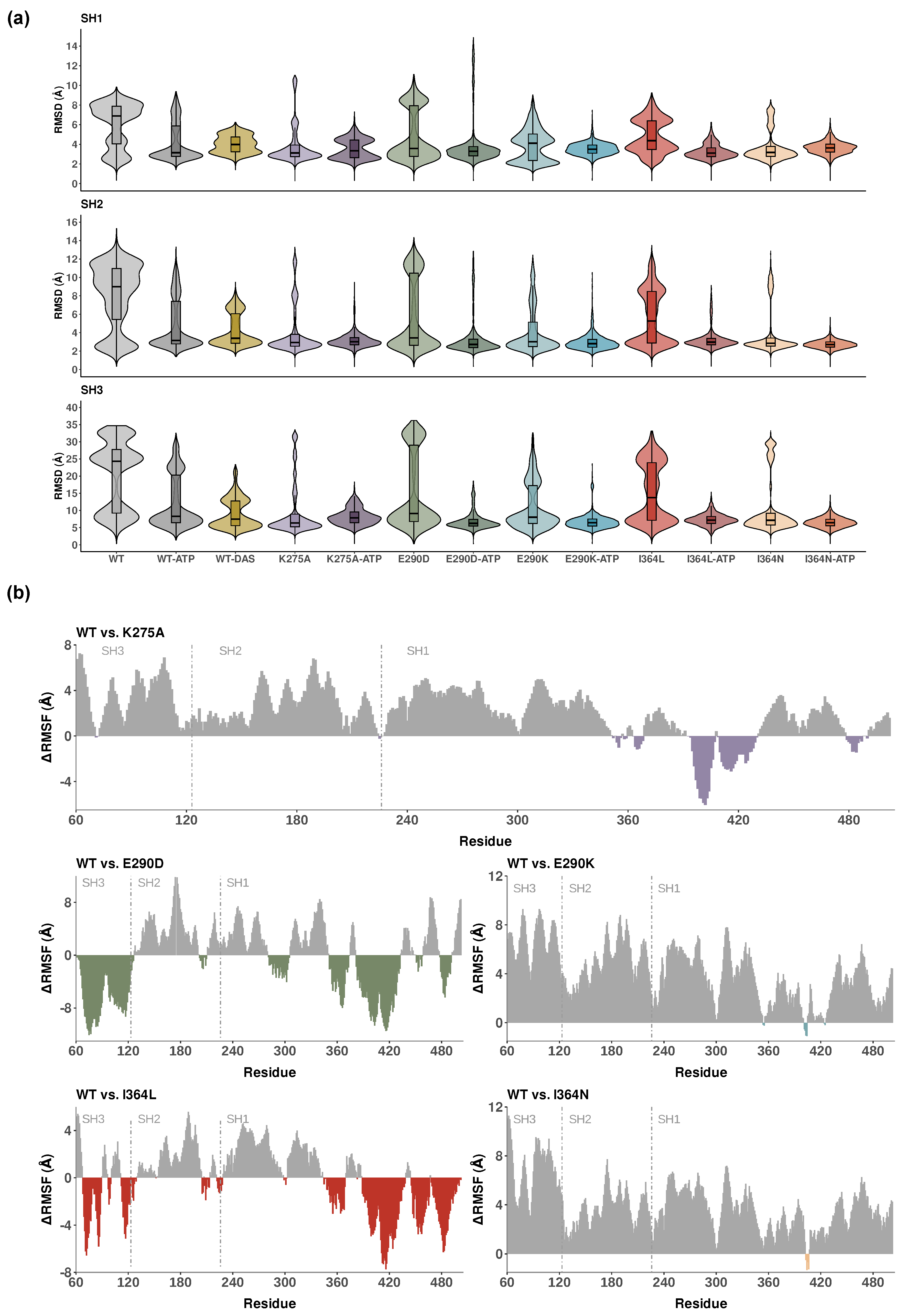

RMSD distributions of backbone atoms per domain are shown in

Figure 2a, with statistical comparisons summarized in Table S2. Among the three domains, SH3 consistently exhibited the highest deviation from the initial structure, reflecting its high mobility and functional role in regulatory switching. Unexpectedly, WT SH3 domain displayed a bimodal distribution, suggesting potential switching between conformational states relevant to regulatory engagement. This was suppressed in SH3 mutants such as I364N, consistent with a stabilized, potentially inactive-like ensemble.

ATP-bound systems generally exhibited reduced RMSD values across all domains in

Figure 2a, consistent with ligand-induced stabilization. In contrast, the WT-DAS system showed significantly higher median RMSD values in SH1 and SH2 (3.98 Å and 3.39 Å, respectively) compared to WT-ATP, indicating increased conformational variability upon dasatinib binding. This likely reflects broader target spectrum and reduced specificity of dasatinib, which may promote alternative structural rearrangements within the catalytic core. Conversely, WT-DAS displayed a significantly lower median RMSD in SH3 (7.5 Å) relative to WT-ATP, suggesting selective stabilization of this regulatory domain. These findings indicate that ATP stabilizes the kinase core, while dasatinib preferentially restricts SH3 dynamics, potentially locking Lyn into a inhibited state.

Among the mutants shown in

Figure 2a, E290D and I364L exhibited higher RMSD values than E290K and I364N, respectively (particularly in the SH3 domain) indicating more substantial structural perturbations. In contrast, K275A-ATP showed moderately elevated RMSD values across all domains, consistent with disruption of ATP binding due to loss of the conserved catalytic lysine. Statistical testing using the Wilcoxon test (Table S2) confirmed significant differences between WT-ATP and all mutant systems, highlighting the broad impact of mutations on domain stability.

To evaluate the localized effects of mutations on residue mobility, we calculated

RMSF values by subtracting the RMSF of mutant systems from WT-ATP (

RMSF = WT − Mutant). Positive values indicate higher flexibility in WT relative to the mutant, while negative values denote increased flexibility in the mutant.

Figure 2b displays these comparisons for K275A, E290D, E290K, I364L, and I364N, with domain boundaries highlighted. Comparisons for all other systems are provided in Figure S1.

Each RMSF plot spans the full 443-residue sequence, with SH3, SH2, and SH1 domains annotated. The conservative substitutions E290D and I364L displayed similar flexibility shifts with a substantial increase (negative RMSF), particularly in SH1 and SH3, supporting a more permissive, active-like conformation. The more disruptive substitutions E290K and I364N exhibited pronounced reductions in flexibility across the full structure (positive RMSF) consistent with an inactive-like and more compact conformation. K275A, which removes the conserved catalytic lysine, led to a marked reduction in flexibility within SH1 and adjacent C-terminal regions, reflecting structural destabilization at the catalytic core. Increased flexibility relative to the WT was observed only in a limited set of residues between positions 390 and 430.

These RMSF patterns reinforce the functional impact of each mutation, linking changes in local mobility to global effects and catalytic accessibility. Importantly, the impact of these mutations extends beyond their immediate location, perturbing interdomain linkers and allosteric communication networks. Additional comparisons in Figure S1 confirmed that ATP binding generally reduces structural flexibility all over the protein structure. WT-DAS complex exhibited higher flexibility in SH1 and SH3 relative to WT-ATP, in line with previous observations.

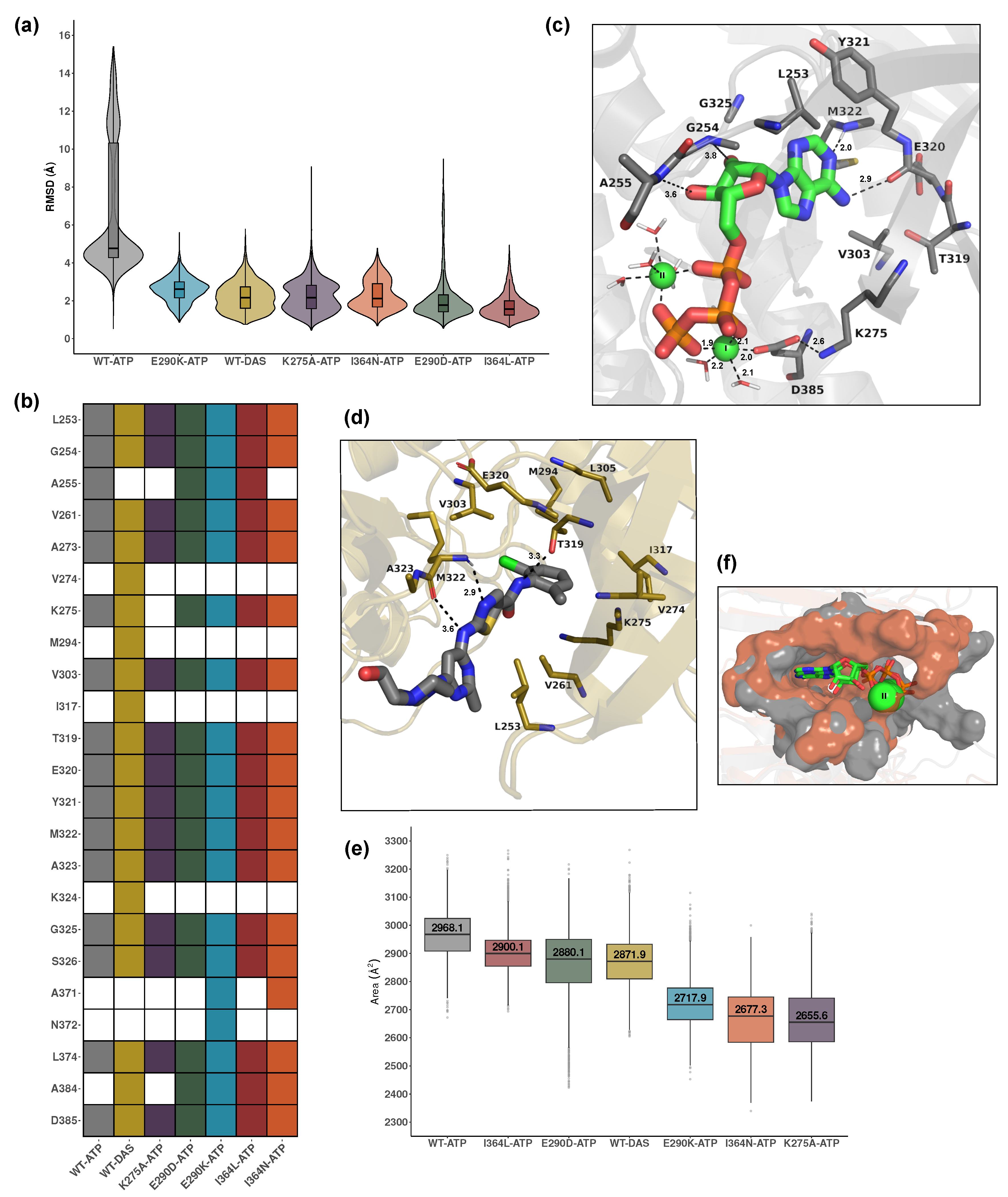

2.2. Ligand and Mutation Effects on Catalytic Site Architecture

To understand how mutations influence the ability of Lyn protein to accommodate ATP, and to contrast these effects with the binding of the ATP-competitive inhibitor dasatinib, we evaluated ligand positional stability, local residue proximity, binding pocket size, binding free energy, and magnesium ion coordination. These complementary analyses offer mechanistic insights into how specific substitutions modulate active-site plasticity, ATP affinity, and conformational shifts driven by inhibitor engagement.

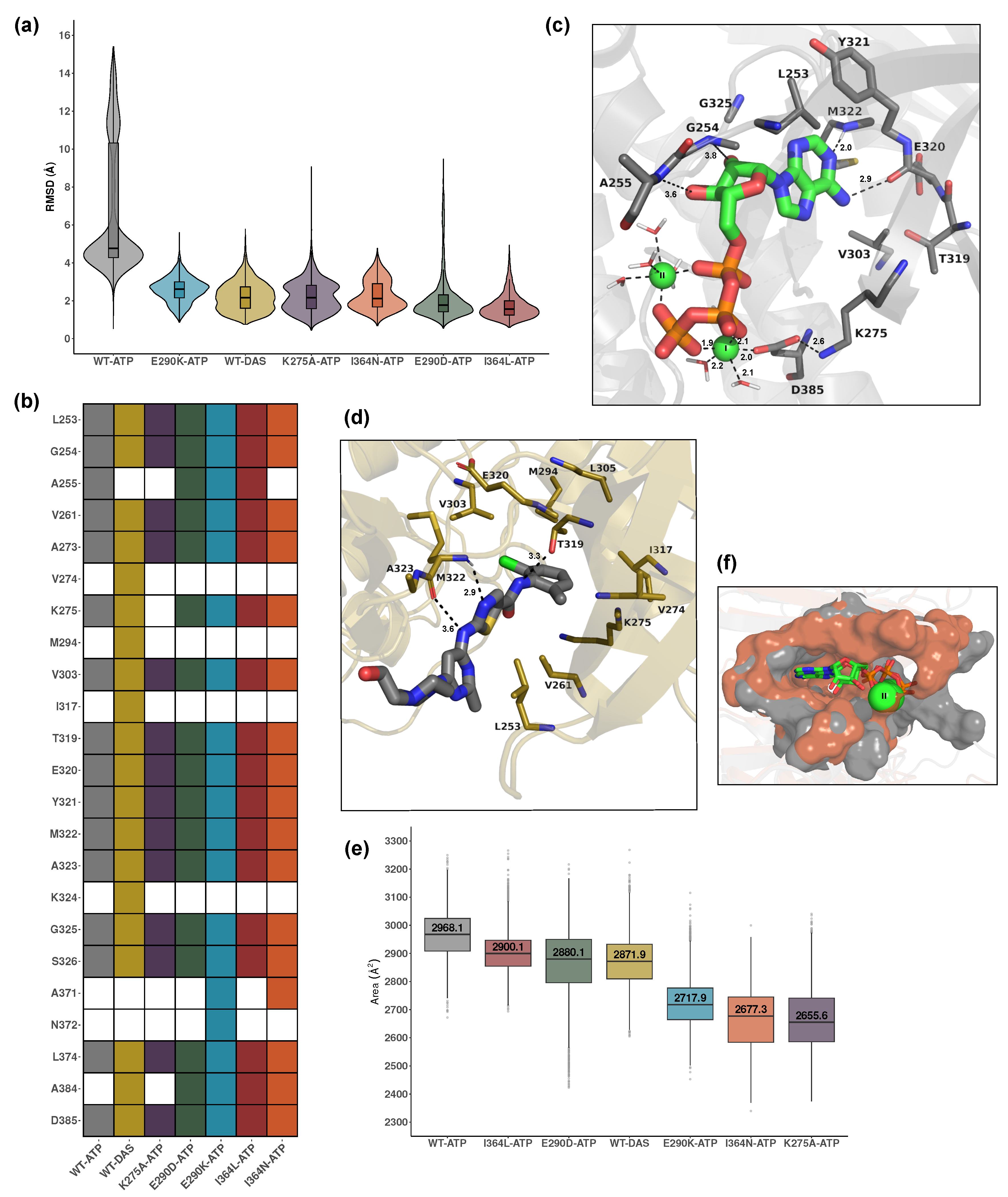

Ligand RMSD analysis shown in

Figure 3a revealed that ATP exhibited lower mobility in all mutant systems, which displayed significantly lower RMSD values compared to WT-ATP. This suggests that these mutations impose spatial constraints or alter pocket accessibility, thereby restricting ATP movement. The RMSD of dasatinib was also significantly lower than that of WT-ATP, indicating that, as a competitive inhibitor, binds with limited conformational flexibility within the pocket and alters the native ATP binding dynamics. Statistical comparisons for all systems are summarized in Table S3.

Figure 3b provides a comparative view of residue environments surrounding the bound ligand across the 7 holo systems. All ATP-bound systems shared a conserved core set of interacting residues, including L253, G254, V261, L263, V303, I317, the loop region around T319-A323, G325, S326, and D385. These residues delineate the canonical SH1 pocket and support stable ATP accommodation. Additional residues such as A255, A371, N372 and A384 were variably engaged in select ATP-bound mutants, indicating subtle context-dependent rearrangements. WT-ATP, E290D-ATP, and I364L-ATP share a highly similar local environment, aligning with their minimal impact on ligand RMSD. E290K, positioned within the coordination site, likely introduced charge repulsion and disrupted

solvation. K275A eliminated a direct phosphate-contacting residue, diminishing ATP electrostatic stabilization.

In contrast, the WT-DAS system displayed a broader and more dispersed set of interacting residues, including V274, M294, A255, I317, and K324, many of which lie outside the core ATP-binding cleft. These observations reflect the bulkier structure of dasatinib and extended reach within the pocket, leading to altered spatial constraints. Several residues unique to WT-DAS were absent from all ATP-bound systems, further supporting a non-canonical binding mode. This divergence underscores the distinct structural consequences of inhibitor versus substrate engagement.

Figure 3c and Figure S2 show that the coordination geometry and asymmetry of the magnesium ions further support these observations. In the WT-ATP system, both

ions were stably coordinated in an octahedral configuration via D385, phosphate groups, and water molecules. MG1 was more tightly coordinated than MG2, as indicated by the number and proximity of surrounding waters (e.g., 2.0–2.2 Å). The oxygen atoms of D385 coordinated mainly MG1 while the triphosphate moiety from ATP was involved in the coordination of both ions. The ATP adopts a compact, horseshoe-like conformation within the binding cleft. Specific hydrogen bonds include D385–MG2 (2.0 Å), D385–K275 (2.6 Å), and E320–adenine (2.0 Å), while triphosphate interactions span 1.8–2.2 Å with coordinating residues and water molecules. This arrangement forms a robust and catalytically favorable environment stabilizing the kinase core. In mutant systems, particularly E290K and I364N, coordination was often asymmetric or incomplete. For example, E290K showed significant disruption, with D385 displaced from the vicinity of MG2 (distance > 4.0 Å), destabilizing the local coordination network (Figure S2). Such asymmetry is characteristic of kinase-inactive states where phosphate transfer is impaired.

Dasatinib exhibited a markedly different binding mode as shown in

Figure 3d. Though it occupies the ATP-binding cleft, it engages a broader and more dispersed set of contacts, particularly in

-sheets and loop regions of SH1, consistent with its promiscuous profile. Dasatinib binds via

-stacking and van der Waals interactions, rather than magnesium-assisted hydrogen bonds. Representative interactions include M322–dasatinib (2.9 Å), A323–dasatinib (3.6 Å), and T319–dasatinib (3.3 Å), primarily located in the SH1

-sheet region. Unlike ATP, dasatinib is elongated, and approximately 44% of the molecule extends beyond the canonical ATP pocket throughout the trajectory. This geometry correlates with increased conformational flexibility in SH1 and SH3 domains, supporting a non-catalytic, inactive-like conformation.

Binding free energy calculations using MM/PBSA further corroborated these findings (Table S4). The WT-ATP system exhibited the strongest interaction ( kcal/mol), consistent with high-affinity binding in a catalytically competent conformation. I364L-ATP and E290D-ATP showed moderate reductions in binding strength ( and kcal/mol, respectively), whereas I364N-ATP and E290K-ATP displayed substantially weakened interactions ( and kcal/mol). The K275A-ATP mutant also showed impaired affinity ( kcal/mol), in line with disruption of catalytic lysine contacts. The WT-DAS complex yielded a binding free energy of kcal/mol, approximately 4 kcal/mol weaker than WT-ATP, reflecting reduced interaction strength. While this shows a relatively stable complex, it is consistent with its the broader and non-specific nature.

Analysis of pocket sizes via SASA measurements reinforced these trends and is shown in

Figure 3e. The WT-ATP displayed the most open and catalytically accessible binding site, with an area of 2968.1 Å

2. In contrast, all ATP-bound mutants showed a reduction in accessible surface area. The most substantial narrowing was observed in K275A-ATP, I364N-ATP, and E290K-ATP with surface areas of 2655.6 Å

2, 2677.3 Å

2, and 2717.9 Å

2 respectively. E290D-ATP showed a less prominent reduction, at 2880.1 Å

2. I364L-ATP retained a more open binding site compared to the other mutants, with a surface area of 2900.1 Å

2. The WT-DAS complex presented a moderate pocket size of 2871.9 Å

2, smaller than WT-ATP but larger than some mutant systems, reflecting different structural effects due to inhibitor binding.

A visual comparison between WT-ATP and I364N-ATP pocket surfaces is shown in

Figure 3f, highlighting the extent of structural narrowing induced by this mutation. Notably, no experimentally resolved 3D structure of full-length Lyn bound to ATP is currently available. Crystallographic data are limited to the isolated SH1 domain in complex with dasatinib [

8]. Thus, these simulations uniquely characterize how ATP interacts with the full multidomain Lyn kinase and how this interaction is perturbed by mutation or inhibition.

Collectively, these results demonstrate that Lyn kinase activity depends on finely tuned spatial and electrostatic determinants at the ATP binding site. Disruption of this environment, whether through direct mutation or allosteric effects, can impair ligand retention, compromise metal coordination, and drive the kinase into an inactive-like state. Conversely, the inhibitor dasatinib induces a distinct, non-catalytic conformation characterized by increased SH3 constrains and reduced plasticity in the kinase core, likely due to its promiscuous and non-specific binding mode.

2.3. Dominant Global Motions Distinguish WT and Mutant Dynamics

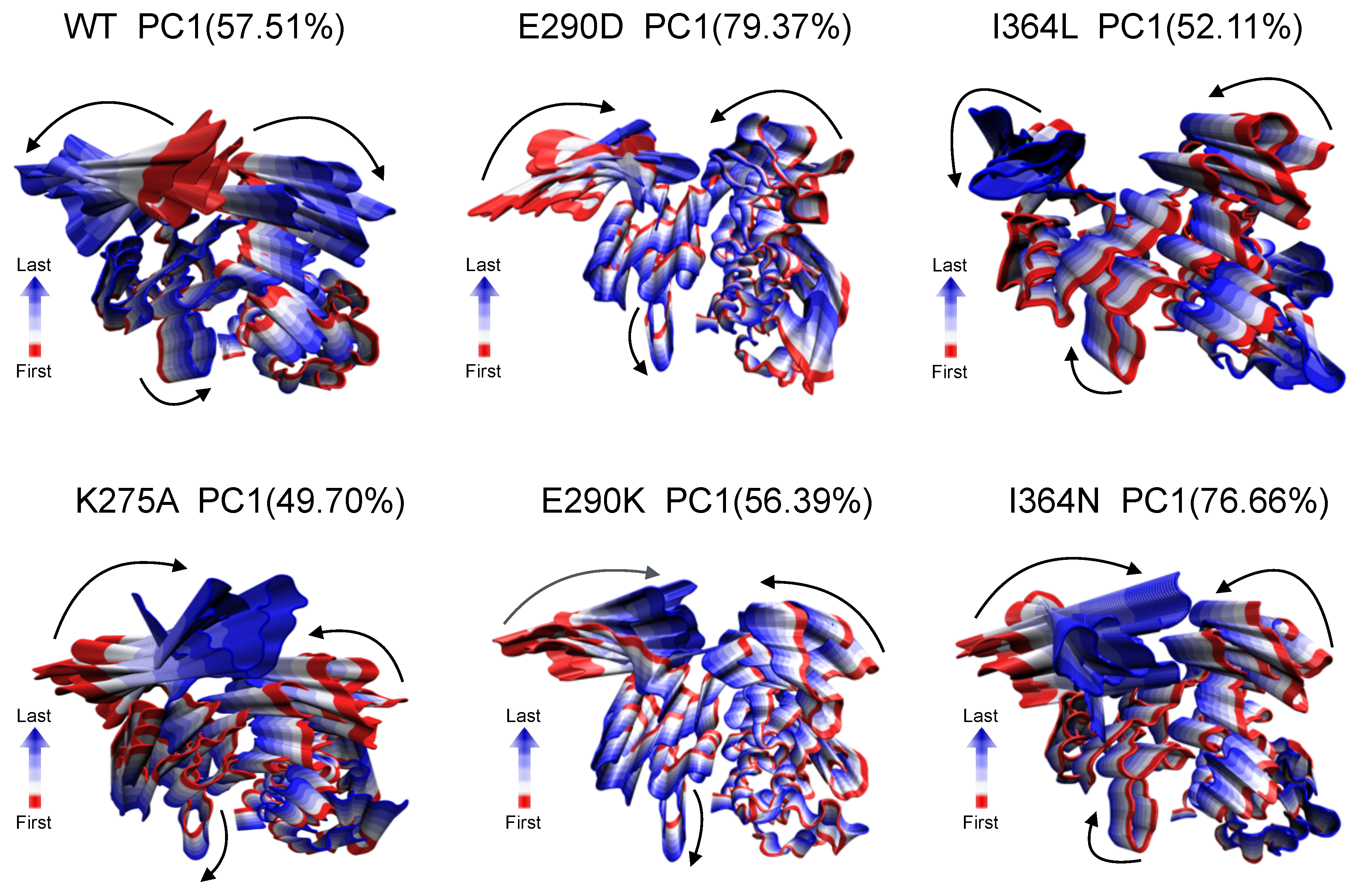

To qualitatively assess global conformational changes across systems, we performed PCA on the trajectories of WT and apo mutants (K275A, E290D, E290K, I364L and I364N). The analysis was based on the covariance matrix of C

atomic fluctuations. Dominant motions were extracted from the first eigenvector (PC1), and the resulting structures represent the extreme conformations along this axis.

Figure 4 illustrates the dominant motions of PC1 for each system, capturing the most relevant structural displacements sampled during the simulation time.

In the WT, PC1 captures coordinated but oppositely directed interdomain movements between SH1 and SH3, consistent with an active-like state that supports catalytic accessibility. In contrast, mutant systems exhibited altered or attenuated motion patterns. For example, K275A showed highly restricted, distorted movements suggestive of structural constraint, while E290K and I364N displayed more localized fluctuations with limited interdomain propagation. These differences imply that even single-point mutations can reshape the dominant motion landscape of the protein, potentially impairing conformational transitions necessary for allosteric regulation and enzymatic turnover. These qualitative trends motivated a more detailed investigation of inter-residue dynamic coupling via cross-correlation analysis.

2.4. Mutation-Induced Perturbations in Allosteric Communication Revealed by DCCMs

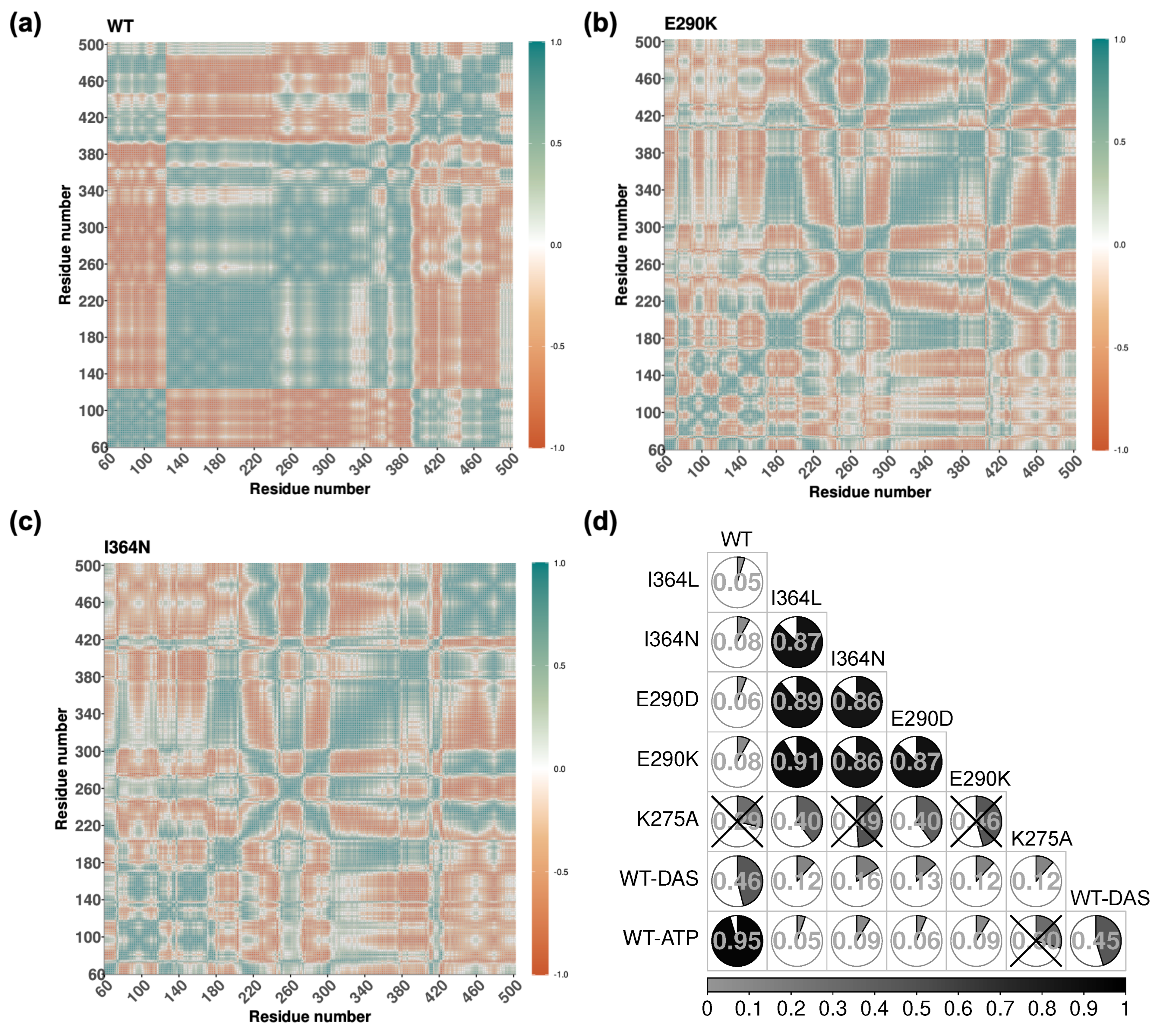

While PCA captures dominant directions of collective motion, it does not provide insight into how different residues move relative to one another. To assess coordinated fluctuations between residues, we computed DCCM for each system. This analysis quantify the extent of correlated (positive values) or anti-correlated (negative values) motions between residue pairs throughout the simulations.

Figure 5 shows the DCCM extracted from the WT (a), E290K (b) and I364N (c) simulations. This analysis revealed that positively correlated motions were generally more prevalent than negative ones. In the WT, these correlations formed a highly structured and organized pattern, particularly between SH3 and SH2, as well as within flexible loop regions of SH1. Such structured correlations are characteristic of an active-like state with intact interdomain communication. In contrast, mutants displayed disrupted or fragmented correlation networks. For example, E290K exhibited localized patterns with diminished interdomain connectivity, and a substantial reduction in long-range correlated motions. The SH2-SH3 axis in E290K appeared partially decoupled, indicating that the mutation imposes structural constraints that weaken dynamic communication. The I364N mutant also showed a loss of structured correlations in interdomain linker regions and an overall shift toward more confined, localized dynamics in SH3 and SH1 domains. This further supports the hypothesis that I364N impairs long-range coordination despite being located outside the catalytic site. The remaining DCCM for all other systems are provided in Figure S3 for comparison.

To quantify differences in correlation behavior across systems, we calculated Pearson correlation coefficients between all pairwise DCCMs (

Figure 5d). The highest similarity was observed between WT and WT-ATP (

r = 0.95), consistent with preserved dynamic coupling upon ATP binding. Among mutants, E290K and I364L exhibited a high degree of similarity (

r = 0.91), followed by E290D and I364L (

r = 0.89). The correlation between E290K and I364N, as well as between E290D and I364N, was also substantial (

r = 0.86 in both cases), suggesting a shared impact on global coordination. In contrast, the correlation between WT-ATP and WT-DAS was much lower (

r = 0.45), highlighting distinct conformational behaviors induced by the inhibitor.

Figure 5d presents a subset of systems; complete pairwise correlation data are available in Table S5.

Together, these analyses provide a system-level view of how point mutations modulate dynamic coupling and interdomain coordination. The prevalence of positive correlations and the well-organized pattern observed in the WT contrast sharply with the fragmented correlation structures seen in mutants. Importantly, the DCCM-based correlation patterns reinforce the notion that both ligand binding and point mutations reshape the allosteric communication network of Lyn in distinct yet mechanistically coherent ways. These altered correlation landscapes serve as the foundation for subsequent network generation and community detection aimed to identify long-range communication hubs.

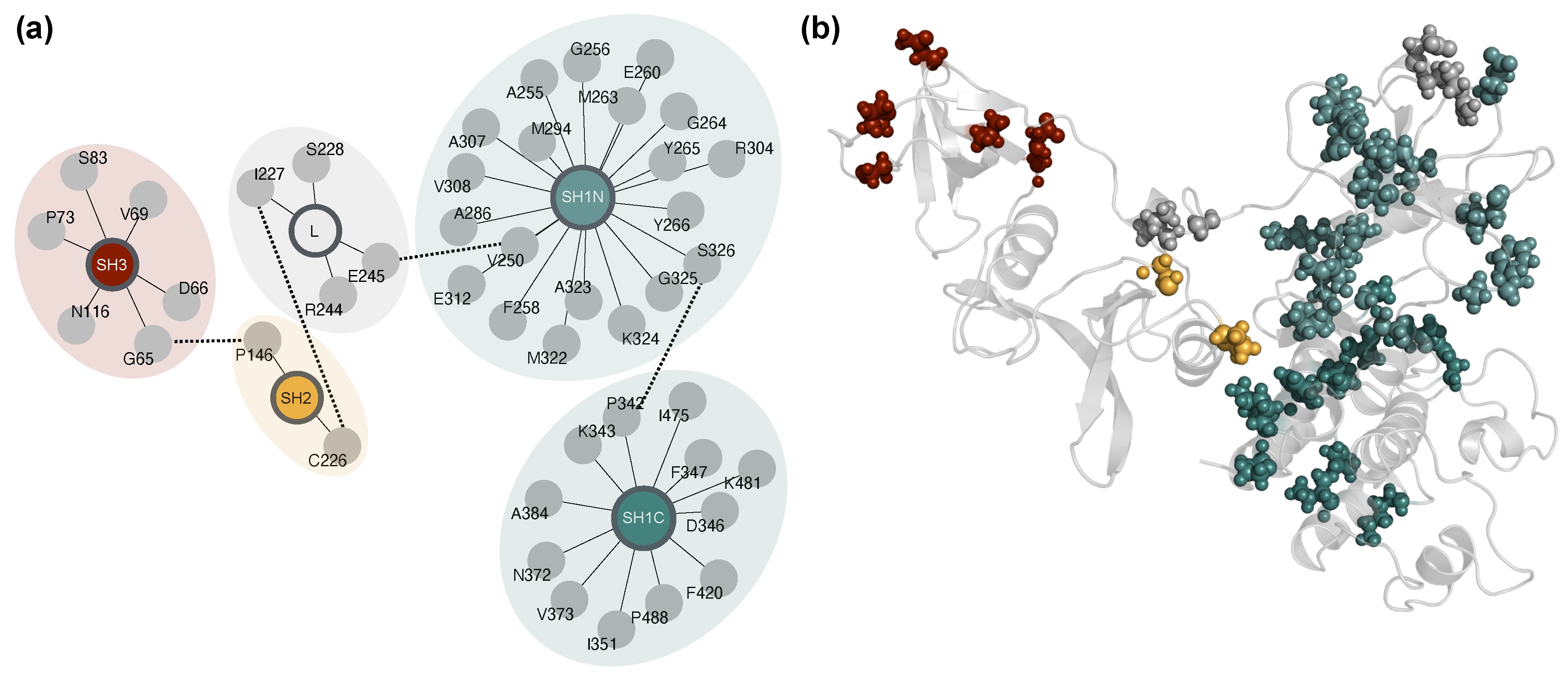

2.5. Network-Based Mapping of Allosteric Hubs

To extend our residue-level correlation analysis toward functional interpretation, we generated dynamic correlation networks and performed community detection. This approach enabled us to identify modular communication pathways and locate potential allosteric control hubs across Lyn systems. Based on structural and dynamic indicators established earlier, including domain-level RMSD/RMSF, pocket compaction, and correlation matrix integrity, WT and WT-ATP systems were classified as active-like, while all mutant systems and WT-DAS were considered inactive-like.

To evaluate how inter-residue dynamic couplings map onto the structural organization of Lyn, we applied community detection to residue-residue correlation networks. This analysis partitions the network into discrete modules of tightly correlated residues, offering a coarse-grained view of each system’s internal dynamic architecture. It is particularly valuable for multidomain proteins like Lyn, where long-range communication plays a central role in functional regulation.

To assess whether individual communities aligned with structural domains or crossed boundaries, we introduced the concept of module purity. Purity was defined as the fraction of residues within a given module that originate from its most dominant structural region. A purity near 1.0 indicates a domain-localized module, while lower values reflect cross-region mixing, a hallmark of dynamic integration. A detailed breakdown of module region composition across systems is provided in Figure S5.

Each system integration module was defined as the community with the lowest purity. This module typically includes residues from multiple structural regions and serves as a candidate hub for allosteric coordination. Most systems exhibited integration modules composed of residues from 5 structural regions. However, in the I364N-ATP system, only 4 regions were represented (SH1N, SH1C, SH2, and SH3) indicating that the interdomain linker was dynamically uncoupled from the rest of the correlated network. Moreover, across all systems, 17 out of 443 residues were not assigned to any integration module. These residues, located primarily in SH2 and SH1C, likely represent structurally flexible or dynamically isolated regions with weak network connectivity. Their consistent exclusion suggests limited involvement in coordinated domain-level dynamics (see Table S6).

To identify residues acting as potential allosteric connectors within these integration modules, we computed betweenness centrality, which quantifies how often a residue lies on the shortest paths between other residues in the correlation network. We focused on the top 25 residues with the highest centrality per system. Although individual connector residues varied, certain residues recurred across multiple systems, suggesting a conserved role in dynamic coordination. Comparisons between apo and holo conditions of mutant systems revealed ligand-induced rewiring of connector networks, with residues gained or lost upon ATP binding often located at interdomain interfaces.

To strengthen the biological relevance of these residues, we examined the correlation between each residue centrality and system-level conformational state (active-like vs. inactive-like). Residues with high positive or negative correlations were likely critical for distinguishing functional states. To further refine the list, we computed a consistency score reflecting recurrence across a range of correlation thresholds and a mixing score quantifying the compositional heterogeneity of the integration module. These metrics were combined into a unified score.

Finally, we integrated structural interface information derived from MD-based contact analysis. Residues were annotated based on their presence at SH1, SH2, SH3, or linker interfaces across systems. The final selection was based on an interface-weighted score that combined dynamic centrality with structural positioning. Residues with a score exceeding 0.5 were defined as allosteric hubs (n = 44), spanning all domains, though fewer were found in the SH2. Many of these hubs localize to the SH2–SH1 linker, SH1N lobe, and SH3-SH1C boundary regions well-positioned to mediate long-range dynamic coupling. Scores for all 443 residues are provided in Table S6; see Methods for a full description of the scoring procedure.

The domain-level organization of connector residues is depicted in

Figure 6a, highlighting their distribution across SH3, SH2, SH1N, SH1C domains, and the interdomain linker. Rather than remaining confined within individual regions, these residues form cross-domain clusters. Dashed connections between modules indicate putative interdomain communication paths derived from the correlation network. When projected onto the 3D structure (

Figure 6b), these residues form a spatially distributed network spanning the entire protein architecture. This organization supports the interpretation that these positions constitute an embedded allosteric wiring system, capable of mediating long-range coupling and responding to both mutation and ligand-induced perturbations.

The allosteric hubs identified here were most prominent in the active systems (WT and WT-ATP) than in mutants and WT-DAS. This suggests that dasatinib binding, like disruptive mutations, destabilizes the native allosteric network rather than shifting it to an alternative configuration. The loss of key connector residues across some inactive-like states underscores a breakdown in long-range coordination and supports the distinction between catalytically competent and inhibited conformations.

2.6. Discriminative Structural Features Define Domain-Level Determinants of Functional States

Given the altered correlation networks and reduced connectivity of key allosteric hubs in mutant systems, we next assessed whether structural and dynamic features extracted from MD trajectories could systematically distinguish different functional states. To this end, we trained a RF classifier using 16 interpretable features derived from each simulation snapshot. These descriptors, listed in Table S7, were selected based on prior observations and included residue–residue distances central to ATP coordination and domain cross-talk (e.g., K275–E290, D385–K275), activation loop geometry (e.g., R-spine angle), and interdomain interactions (e.g., SH2–SH3, SH3–SH1N).

The dataset included approximately 78,000 frames, each represented by these 16 features. Systems were labeled as “active-like” (WT, WT-ATP) or “inactive-like” (WT-DAS, all mutants), based on structural, dynamic and correlation-based criteria established earlier. Importantly, while the classifier was not primarily developed for predictive application, it provided a means to evaluate which features best encode conformational differences across the ensemble. The classifier achieved, in the test dataset, an overall accuracy of 96%, with high recall and precision for both active-like and inactive-like classes. All metrics used to evaluate performance are summarized in

Table 1. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was 0.98, indicating as shown in

Figure 7a.

Feature importance rankings are shown in

Figure 7b. The most important features included the K275–E290 salt bridge, SH3–SH1N distance, and E290–D385 coupling—interactions that span both regulatory and catalytic domains. Additional high-ranking descriptors such as SH2–SH3 separation, D385–K275 distance, and the R-spine angle further emphasize the importance of interdomain coordination. The top seven features together accounted for approximately 66.7% of the total permutation importance, underscoring their dominant contribution to functional classification.

This analysis supports the notion that interdomain interactions are among the most informative determinants of functional state in full-length Lyn kinase. The classifier reinforces and quantifies insights gained from structural, dynamical, and network-based analyses, validating that conformational coupling between SH3, SH2, and SH1 domains plays a defining role in distinguishing active-like and inactive-like ensembles.

3. Discussion

Protein kinases function as dynamic molecular switches, and their regulation depends on the intricate coordination of structural domains and conformational plasticity [

18]. Among SFKs, Lyn is known for its roles in hematopoietic signaling, immune regulation, and cancer biology [

4,

19]. However, unlike Src or Hck, Lyn remains structurally understudied, with no experimentally determined multidomain structures and only limited human SH1 domain crystal structures in complex with inhibitors such as dasatinib [

8,

20]. This study presents the first long-timescale MD analysis of full-length Lyn kinase, including SH3, SH2, and SH1 domains, across WT and mutant states in both apo and ligand-bound forms.

Our simulations provide a detailed framework for understanding how domain coordination, ligand binding, and sequence variants collectively shape Lyn conformational landscape. ATP binding stabilizes a catalytically competent, active-like state by reinforcing SH1 integrity and preserving interdomain coupling with SH2 and SH3. In contrast, the ATP-competitive inhibitor dasatinib induces a markedly different response, increasing flexibility in SH1 and SH2 and reducing plasticity in SH3. This redistribution resembles previous observations in Src [

21,

22], but extends them to Lyn in a multidomain context. These differences were further supported by binding free energy calculations: ATP showed the strongest affinity (

kcal/mol), whereas dasatinib exhibited moderately reduced affinity (

kcal/mol), consistent with its broader, non-specific binding mode. These results reinforce the notion that ATP stabilizes a high-affinity, catalytically competent state, while both mutation and inhibitor binding attenuate this stability through distinct structural mechanisms.

Cancer-associated mutations such as E290K and I364N were found to promote catalytically impaired conformations. E290K disrupts

solvation and weakens electrostatic interactions necessary for phosphate coordination [

23], while I364N—despite its distal location—disrupts global dynamics by decoupling SH3 from the interdomain linker. I364N has not previously been characterized structurally, but its predicted oncogenic potential [

17] aligns with our finding that it impairs long-range coordination.

Comparison with related SFKs highlights both conserved and distinct regulatory features. Although Src has been extensively studied and shown to undergo ATP-induced stabilization of the kinase core [

24], most structural analyses remain limited to SH1-only models [

25,

26]. Allosteric regulation has been explored within the SH1 domain in Src using computational and experimental approaches [

27,

28], but such studies do not extend to full-length models. Only a few works have investigated full-length SFKs, including Src, Lck, and Hck, using experimental or simulation-based strategies [

29,

30,

31].

Our results suggest that Lyn exhibits unique regulatory features. In particular, SH3–SH1N coupling appears to play a more dominant role in stabilizing the active-like state, in contrast to the highly correlated SH2–SH3 connector often emphasized in inactive states [

32]. The SH3 displacement observed in Lyn resembles conformational shifts described in Hck (the closest homolog related to Lyn) [

33] and Src [

34], where SH3 disengages from the linker while the tail remains SH2-bound. These observations support the idea of alternative active conformations within individual Src-family members with distinct signaling properties [

35,

36].

To explore how mutations and ligand binding reshape this regulatory landscape, we performed community detection on DCCM and identified integration modules (low-purity communities spanning multiple domains). These modules harbor dynamically coordinated residues, including 44 allosteric hubs that were preferentially associated with active-like states. Their reduced representation in mutant systems suggests that mutations attenuate conserved long-range communication rather than rewire it.

To further corroborate our structure-based and network-derived findings, we applied a RF classifier trained on 16 interpretable MD-derived features. Although not intended as a predictive tool, the classifier allowed us to systematically evaluate which structural and dynamic descriptors best distinguish active-like from inactive-like states. The top seven features accounted for approximately two-thirds of the total feature importance, confirming that interdomain distances and salt bridges are major discriminants of kinase state, consistent with our network-derived regulatory features. Recent machine learning frameworks for kinase structure prediction [

37,

38] have highlighted the utility of AI in capturing conformational variability. In contrast, our physics-based approach provides structural interpretability and temporal resolution, offering mechanistic insight into dynamic regulation. Taken together, these results reinforce and quantify the broader structure–function relationships revealed through MD simulations and network modeling, and underscore the value of integrating machine learning with physics-based methods to dissect allosteric control in multidomain kinases.

From a therapeutic perspective, these findings are highly relevant. Lyn is implicated in hematological malignancies and resistance to kinase inhibitors like imatinib and dasatinib [

39]. Our results suggest that Lyn may function as a context-dependent oncogene, with certain mutations as E290K and I364N contributing to dysfunctional signaling via long-range allosteric disruption. Importantly, conventional structure-based design has focused on static, isolated domains. Our results highlight that key regulatory features, such as SH3–SH1 coupling and integration hubs, emerge only in full-length, dynamics-resolved models. These insights could support the development of more selective allosteric modulators [

40,

41].

This study provides a basis for future experimental investigations. Many of the identified allosteric hubs could be targeted for mutagenesis or probed using conformational biosensors such as FRET or HDX-MS [

42]. Our integrative computational framework offers a generalizable approach to dissect allosteric regulation in other multidomain kinases or signaling proteins.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Homology Modeling of Full-Length Lyn Protein

A full-length structural model of Lyn kinase (residues 60 to 502) was generated using Modeller [

43]. High-resolution crystal structures of homologous SFKs were used as templates: 6NMW (human Lyn SH3 domain), 4TZI (mouse Lyn SH2 domain), and 5H0B (human full-length Hck). Model quality was assessed using the ERRAT server [

44], yielding a global quality factor of 99.1, indicative of a high-confidence model suitable for molecular simulations. The final model was energy-minimized using the steepest descent algorithm in GROMACS 2022.04 [

45].

4.2. Mutant Generation and Small Molecule Incorporation

Single-point mutations at residues I364 (I364L and I364N), E290 (E290D and E290K), and K275 (K275A) were introduced into the full-length Lyn model using SCWRL4 program with default parameters [

46]. These variants were selected based on their presence in cancer genomics datasets or previously reported functional relevance. For ATP-bound systems, one ATP molecule and two

ions were positioned in the catalytic cleft by structural alignment to the kinase complex in PDB ID: 1ATP. For the system containing the ATP-competitive inhibitor dasatinib, coordinates were extracted from the crystal structure (PDB ID: 2ZVA), superimposed onto the modeled apo Lyn structure, and energy-minimized to resolve steric clashes and refine the binding pose. Both WT and mutant models, either unbound (apo), ATP-bound (holo), or dasatinib-bound (holo), were used as inital structures for MD simulations.

4.3. Quantum mechanical calculations

Geometry optimization, frequency calculations, and population analyses of dasatinib were performed with the Gaussian 16 package of programs [

47] using the B3LYP functional and the 6-31 G(d) basis set. Geometry optimization and frequency calculations were carried out in solution, using the SMD continuum model and water as solvent. SMD is considered a universal solvation model, due to its applicability to any charged or uncharged solute in any solvent or liquid medium [

48]. Vibrational analysis indicates that geometries correspond to minima. Computed electrostatic potential (ESP) derived atomic charges were used later for MD simulations.

4.4. Classical MD simulations

A summary of all simulations is presented in Table S1. We conducted 78

of MDs (3 replicates per system, to ensure reproducibility) using the all-atom additive CHARMM36 force field [

49] with optimized magnesium binding parameters [

50] in GROMACS 2022.04 [

45]. The protein was placed in the center of a rhombic dodecahedron box with a minimal distance from the structure to the box boundaries of 10 Å. The TIP3 explicit water model [

51] was used to solvate the system. Sodium and chloride ions were added to neutralize the systems at an ionic concentration of

/

. Equilibration included 5 ns in the NVT ensemble with restrained heavy atoms, followed by 5 ns in the NPT ensemble without restraints. Temperature was stabilized at 310 K using V-rescale thermostat [

52] and pressure at 1 atm by the Parinello-Rahman barostat [

53], respectively. Electrostatic interactions were calculated using the Particle Mesh Ewald [

54] and LINCS [

55] was used for bond constraints. Production MD simulations were computed for 2

each on a GPU (GeForce RTX 4090, Cuda 12.2) with a 2 fs time step. Coordinates, velocities, and energies were saved every 1 ns.

4.5. Trajectory Analyses

Trajectory analyses were performed using GROMACS tools to assess structural stability and residue-level fluctuations. Backbone RMSD was calculated on backbone atoms using

gmx rms, and RMSF was calculated on C

atoms using

gmx rmsf. Distances and angles were computed using

gmx distance and

gmx angle, respectively, and all outputs were processed and analyzed in R Statistical Software (v4.4.1; R Core Team 2021 [

56]). Representative structures were extracted from the trajectories by clustering frames based on mutual backbone RMSDs using the PAM algorithm implemented in the

cluster R package [

57]. Clustering quality was evaluated using silhouette coefficients computed with the

fpc R package [

58]. For each system, the most populated cluster was selected, and its medoid, the frame with the lowest average RMSD to all other frames within the cluster, was defined as the representative structure.

4.6. Interface Residues

Interdomain interface residues were identified using the InterfaceResidues plugin in PyMOL. This method estimates solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) changes to detect residues involved in domain–domain interactions. The algorithm first calculates the SASA of the full complex, then separates the complex into two regions (e.g., individual domains or chains) and computes the SASA for each independently. The difference between the summed individual SASAs and the complex SASA (SASA) reflects the buried surface area upon domain association. Residues exhibiting a SASA reduction greater than 1.0 Å2 were classified as interface residues.

4.7. Binding Pocket Surface Area Estimation

To estimate binding pocket size across systems, the SASA of the ligand (ATP or dasatinib) was calculated. Pocket residues were predefined as all residues within a 5 Å radius of the ligand, effectively delineating the binding site based on spatial proximity. The SASA of this ligand-surrounding region was then computed using GROMACS analysis tools and used as an approximation of pocket surface area.

4.8. Projection of Dominant Motions Along Principal Components

To investigate large-scale conformational dynamics, we projected atomic displacements along the principal components derived from each system trajectory. PCA was performed in GROMACS using the positional fluctuations of C

atoms. The covariance matrix was calculated with

gmx covar, and eigenvectors were analyzed using

gmx anaeig. To visualize the dominant motions, extreme projections along the first principal component (PC1) were generated, representing the maximum conformational deviations along this mode. A series of interpolated structures was then constructed to illustrate the transition between these extremes. These structures were visualized using VMD [

59], enabling interpretation of system-specific differences.

4.9. Dynamical Cross-Correlation Analysis

Dynamical cross-correlation analysis was performed to identify coupled motions within the protein. Pairwise cross-correlation coefficients of atomic fluctuations were computed using the

dccm function from the Bio3D package [

60]. C

atoms were used to align trajectory frames, and an

cross-correlation matrix was generated, where

N is the number of residues. Each matrix element reflects the degree of dynamic correlation between atomic displacements. The results were visualized as dynamical cross-correlation matrices.

4.10. Community Detection and Integration Module Identification

Community detection was performed using the Louvain algorithm on DCCM to examine how residue-residue correlations organize into structural communities. For each system, an undirected, weighted graph was constructed from the upper triangle of the dynamical cross-correlation matrix, retaining edges with absolute correlation values above a threshold of 0.8. Residues were represented as nodes, and edge weights reflected the magnitude of dynamic correlation. Communities (modules) were identified based on graph topology using the Louvain algorithm, and module memberships were mapped to known structural regions (SH1N, SH1C, SH2, SH3, and the interdomain linker). To assess the degree of structural integration, the purity of each module was calculated as the fraction of residues belonging to the dominant structural region. Modules with low purity, spanning multiple domains, were considered “integration modules.” The lowest-purity module from each system was selected for downstream analysis.

4.11. Identification of Allosteric Hubs from Networks and Interface Features

Residues with potential allosteric significance were identified based on their betweenness centrality within each system’s integration module. Betweenness values were computed on the full residue–residue correlation network, and residues were ranked according to their centrality within each system. To capture functionally relevant variation, the correlation between each residue’s centrality profile and the binary classification of systems as active-like or inactive-like was calculated. For a given residue

r, the vector of betweenness values across all

N systems was denoted as

, and the corresponding activity labels were encoded as

, where

for active-like systems and

otherwise. The Pearson correlation

was used to quantify the relationship between centrality and conformational state. To further characterize residue behavior, a module-mixing index

was calculated for each residue

r in each system

s, reflecting the compositional heterogeneity of its integration module. The mean module-mixing score across systems was computed as:

These two quantities were combined to produce a mixing-weighted correlation score, which integrates functional sensitivity and modular diversity:

To incorporate structural context, domain interface frequency was introduced as a weighting factor. The criteria for identifying whether a residue belongs to an interdomain interface are detailed in

Section 4.6. For each residue

r, the number of systems in which it was part of an interdomain interface was recorded as

, and normalized as

. This value was used to compute an interface-weighted score:

which reflects both dynamic and interface-associated significance. Residues with an interface-weighted score greater than 0.5 were classified as allosteric hubs. The full set of scoring results is provided in Table S6.

4.12. Random Forest Classification

A supervised classification pipeline was implemented using the scikit-learn library to evaluate which structural and dynamic features most effectively distinguish active-like from inactive-like conformational ensembles of Lyn kinase. Sixteen interpretable features were extracted from MD trajectories (Table S7).

Approximately 78,000 simulation frames were analyzed, each labeled as “active-like” (WT, WT-ATP) or “inactive-like” (WT-DAS and all mutant systems). All features were treated as continuous variables and scaled using Min–Max normalization. The dataset was randomly shuffled and partitioned into training (80%) and testing (20%) sets using stratified sampling to maintain class distribution. To address class imbalance, a modeling pipeline combining the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) [

61] with a RF classifier was applied. Hyperparameters including the SMOTE sampling ratio, number of estimators, maximum tree depth, and class weighting—were optimized via grid search with five-fold cross-validation.

The final model was trained using the following optimal parameters: n_estimators = 1000, max_depth = None, class_weight = None, and smote__sampling_strategy = 0.5. Model performance was evaluated on the test set using standard classification metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and the AUC. Feature importances were computed using both Gini index and permutation methods and are reported with respect to the original feature names.

4.13. Statistics

Statistical significance was assessed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (two-sided, significance threshold ). Detailed numerical data supporting the analyses are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, R.R.-R.; methodology, J.R.A.-I., O.K. and R.R.-R.; software, M.R., F.H., J.R.A.-I., O.K. and R.R.-R.; formal analysis, M.R., F.H., E.P., F.R. and O.K.; resources, M.H., J.R.A.-I., O.K. and R.R.-R.; data curation, M.R., F.H., E.P. and F.R.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R. and R.R.-R.; writing—review and editing, M.R. and R.R.-R.; visualization, M.R. and F.H.; supervision, R.R.-R.; funding acquisition, M.H and R.R.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Figure 1.

Domain organization and conformational states of full-length Lyn kinase. Top: Schematic representation of Lyn modular architecture, comprising SH3, SH2, and SH1 (kinase) domains, connected by flexible linkers. Key catalytic residues (K275 in the N-lobe and Y397 in the C-lobe) are indicated. Bottom: Cartoon depiction of the conformational switch between the active (left) and inactive (right) states. In the inactive conformation, SH3 engages the SH2–SH1 linker and SH2 interacts with the phosphorylated C-terminal tail, stabilizing autoinhibition. In the active state, SH3 is displaced, allowing an open, catalytically competent conformation. Figure created with BioRender.

Figure 1.

Domain organization and conformational states of full-length Lyn kinase. Top: Schematic representation of Lyn modular architecture, comprising SH3, SH2, and SH1 (kinase) domains, connected by flexible linkers. Key catalytic residues (K275 in the N-lobe and Y397 in the C-lobe) are indicated. Bottom: Cartoon depiction of the conformational switch between the active (left) and inactive (right) states. In the inactive conformation, SH3 engages the SH2–SH1 linker and SH2 interacts with the phosphorylated C-terminal tail, stabilizing autoinhibition. In the active state, SH3 is displaced, allowing an open, catalytically competent conformation. Figure created with BioRender.

Figure 2.

Domain-resolved analysis of structural deviations and local flexibility across Lyn kinase systems. (a) Violin plots showing backbone RMSD distributions per domain (SH1, SH2, SH3) for all 13 systems. RMSD values reflect deviations from the starting structure and indicate domain-level stability. (b) RMSF plots for key mutants (K275A, E290D, E290K, I364L, I364N), calculated as the difference in RMSF of WT relative to the mutant (WT − Mutant). Positive values indicate reduced flexibility in mutants, while negative values denote increased flexibility. Domain boundaries (SH3, SH2, SH1) are annotated and separated by dashed vertical lines.

Figure 2.

Domain-resolved analysis of structural deviations and local flexibility across Lyn kinase systems. (a) Violin plots showing backbone RMSD distributions per domain (SH1, SH2, SH3) for all 13 systems. RMSD values reflect deviations from the starting structure and indicate domain-level stability. (b) RMSF plots for key mutants (K275A, E290D, E290K, I364L, I364N), calculated as the difference in RMSF of WT relative to the mutant (WT − Mutant). Positive values indicate reduced flexibility in mutants, while negative values denote increased flexibility. Domain boundaries (SH3, SH2, SH1) are annotated and separated by dashed vertical lines.

Figure 3.

Structural and dynamic insights into ATP and dasatinib binding. (a) Violin plots showing RMSD distributions of ATP and dasatinib ligands across all holo systems, indicating ligand positional stability within the binding site. (b) Heatmap of residues within 5 Åof the ligand in each system, reflecting the composition of the local binding environment. Shared and unique contacts across systems illustrate ligand-specific interaction patterns. (c) Representative binding of ATP in the WT-ATP system, highlighting key coordinating residues and Mg2+-mediated contacts. Dashed lines indicate coordination distances between ATP, residues, and metal ions. (d) Representative dasatinib binding in WT-DAS, showing broader and more dispersed contact residues including loop and -sheet regions. Dashed lines indicate key intermolecular distances involved in the binding. (e) Pocket size estimated based on the SASA of the ligand-defined region in each system, reflecting mutation- or inhibitor-induced compaction. (f) Structural comparison of pocket accessibility between WT-ATP and I364N-ATP systems, highlighting narrowing of the cavity in the mutant.

Figure 3.

Structural and dynamic insights into ATP and dasatinib binding. (a) Violin plots showing RMSD distributions of ATP and dasatinib ligands across all holo systems, indicating ligand positional stability within the binding site. (b) Heatmap of residues within 5 Åof the ligand in each system, reflecting the composition of the local binding environment. Shared and unique contacts across systems illustrate ligand-specific interaction patterns. (c) Representative binding of ATP in the WT-ATP system, highlighting key coordinating residues and Mg2+-mediated contacts. Dashed lines indicate coordination distances between ATP, residues, and metal ions. (d) Representative dasatinib binding in WT-DAS, showing broader and more dispersed contact residues including loop and -sheet regions. Dashed lines indicate key intermolecular distances involved in the binding. (e) Pocket size estimated based on the SASA of the ligand-defined region in each system, reflecting mutation- or inhibitor-induced compaction. (f) Structural comparison of pocket accessibility between WT-ATP and I364N-ATP systems, highlighting narrowing of the cavity in the mutant.

Figure 4.

Dominant global motions captured by principal component analysis (PCA). Snapshots representing extreme projections along PC1 are shown for WT and mutant systems (K275A, E290D, E290K, I364L, and I364N). PC1 accounts for the highest variance in atomic fluctuations and captures large-scale domain movements. Structures are colored from red (start of motion) to blue (end of motion), illustrating the directionality and amplitude of motion. Arrows indicate the dominant direction of displacement along PC1 for SH3, SH2, and SH1 domains. Percentage values in parentheses denote the variance explained by PC1 in each system.

Figure 4.

Dominant global motions captured by principal component analysis (PCA). Snapshots representing extreme projections along PC1 are shown for WT and mutant systems (K275A, E290D, E290K, I364L, and I364N). PC1 accounts for the highest variance in atomic fluctuations and captures large-scale domain movements. Structures are colored from red (start of motion) to blue (end of motion), illustrating the directionality and amplitude of motion. Arrows indicate the dominant direction of displacement along PC1 for SH3, SH2, and SH1 domains. Percentage values in parentheses denote the variance explained by PC1 in each system.

Figure 5.

(a–c) DCCMs for WT, E290K, and I364N systems showing pairwise correlations of C atom displacements. Positive correlations are shown in teal, negative in red, with intensity reflecting correlation magnitude. WT exhibits well-structured long-range correlations across domains, indicative of coordinated dynamics. Mutants E290K and I364N display fragmented and localized correlation patterns, reflecting impaired interdomain communication. (d) Pearson correlation coefficients between DCCMs across all systems. Each cell is represented as a pie chart with shading proportional to the correlation value displayed at the center. Cells marked with “X” denote comparisons where the correlation was not statistically significant.

Figure 5.

(a–c) DCCMs for WT, E290K, and I364N systems showing pairwise correlations of C atom displacements. Positive correlations are shown in teal, negative in red, with intensity reflecting correlation magnitude. WT exhibits well-structured long-range correlations across domains, indicative of coordinated dynamics. Mutants E290K and I364N display fragmented and localized correlation patterns, reflecting impaired interdomain communication. (d) Pearson correlation coefficients between DCCMs across all systems. Each cell is represented as a pie chart with shading proportional to the correlation value displayed at the center. Cells marked with “X” denote comparisons where the correlation was not statistically significant.

Figure 6.

Spatial and network organization of the 44 allosteric hubs identified across systems. (a) Network-based schematic showing the distribution of allosteric hub residues across Lyn kinase domains. Hubs are grouped and colored by structural regions (SH3, SH2, interdomain linker [L], SH1N, SH1C). Dashed edges indicate putative interdomain communication paths inferred from correlation network topology. (b) 3D spatial mapping of the same 44 residues onto the WT full-length Lyn structure. Hub residues are shown as spheres and colored as in (a), highlighting their broad distribution and role in bridging multiple domains. This architecture supports a model of embedded allosteric wiring responsive to ligand binding and mutation.

Figure 6.

Spatial and network organization of the 44 allosteric hubs identified across systems. (a) Network-based schematic showing the distribution of allosteric hub residues across Lyn kinase domains. Hubs are grouped and colored by structural regions (SH3, SH2, interdomain linker [L], SH1N, SH1C). Dashed edges indicate putative interdomain communication paths inferred from correlation network topology. (b) 3D spatial mapping of the same 44 residues onto the WT full-length Lyn structure. Hub residues are shown as spheres and colored as in (a), highlighting their broad distribution and role in bridging multiple domains. This architecture supports a model of embedded allosteric wiring responsive to ligand binding and mutation.

Figure 7.

Random forest classifier distinguishes active- and inactive-like Lyn ensembles based on structural and dynamic features. (a) Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve showing classifier performance, with an AUC of 0.985, indicating excellent discrimination between functional states. (b) Feature importance analysis based on Gini index and permutation method. Top-ranking descriptors include the E290–K275 and E290–D385 distances, SH3–SH1N separation, and D385–K275 interaction.

Figure 7.

Random forest classifier distinguishes active- and inactive-like Lyn ensembles based on structural and dynamic features. (a) Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve showing classifier performance, with an AUC of 0.985, indicating excellent discrimination between functional states. (b) Feature importance analysis based on Gini index and permutation method. Top-ranking descriptors include the E290–K275 and E290–D385 distances, SH3–SH1N separation, and D385–K275 interaction.

Table 1.

Metrics used to evaluate the performance of the RF classifier.

Table 1.

Metrics used to evaluate the performance of the RF classifier.

| |

Precision |

Recall |

F1-score |

| Active-like |

0.91 |

0.84 |

0.87 |

| Inactive-like |

0.97 |

0.98 |

0.98 |

| Accuracy |

0.96 |

| Macro average |

0.94 |

0.91 |

0.92 |

| Weighted average |

0.96 |

0.96 |

0.96 |