1. Introduction

Carbon dioxide is the major greenhouse gas contributing to global warming, which triggers numerous climate and environment catastrophes, and the situation is continuing to deteriorate [

1,

2]. According to the Global Carbon Budget 2023 [

3,

4], annual carbon dioxide emission could increase to 36.8 billion tons in 2023, primarily from combustion of carbon containing fuels. Carbon dioxide discharge control and reduction has attracted the grave attentions of governments all over the world. Scientists and engineers from various areas have been exploring viable technologies for carbon dioxide reduction in recent decades. Based on the final status of CO₂ conversion, the approaches reported for CO₂ reduction and removal can be classified as CO₂ fixing methods and elemental carbon fixing methods involving the splitting of CO₂.

For CO₂ fixing methods, CO₂ is converted into new substance such as biomass, methanol, starches, or carbonates, or just captured and stored in some manners.

These include forestation and plantation on land, i.e., planting trees and other botany to absorb CO₂ through photosynthesis mechanism, i.e., biochemical processes [

5,

6,

7]. This is efficient for the reduction of CO₂ near ground as the trees only grow up to limited heights. Marine permaculture, i.e., growing seaweed or kelp forests, which absorb CO₂ and can be harvested for bioenergy or sunk to the ocean floor for long-term storage, is a similar solution [

7,

8]. In the long run, this type of methods is the most environmentally friendly approach while requiring continuous efforts and time.

Converting CO₂ to useful products by chemical or biochemical processes have also explored by researchers [

9], for example, synthesizing methanol and dimethyl ether through hydrogenation using catalysts [

10,

11,

12], CO

2 reduction to formic acid via electrochemical and hydrogenation processes [

13,

14], starch synthesis from carbon dioxide via cell-free chemoenzymatic process [

15], synthesis of hexoses from carbon dioxide [

16], etc. The feasibility of these processes will be determined by their economical viability and process complexity.

Direct CO₂ capture technologies by absorption or adsorption using various materials/substances such as amine solutions [

17], ionic liquid [

18], solid polymeric support material with amino functionalities [

19], activated carbons [

20], sulfur-doped porous carbon adsorbent [

21], nitrogen doped carbon [

22], ultrapermeable carbon molecular sieve membrane [

23], and metal organic framework materials (MOFs) [

24,

25], have been extensively investigated. CO₂ from industrial sources (e.g., power plants, cement factories) was captured and stored underground [

26] or used in industrial applications such as enhanced oil recovery. Obviously, these kinds of methods only removing CO₂ from onsite production temporarily.

Capturing CO₂ using metal oxides and converting it into carbonate minerals through natural or accelerated processes is relatively thorough for carbon dioxide fixing, compared to absorption or adsorption processes [

27,

28]. However, the formed carbonates can be decomposed and release CO₂ again under the attacking of acidic media such as acid rains. Therefore, carbonates are not the ideal final status for CO₂ fixing.

Splitting CO₂ and fixing the elemental carbon is obviously a thorough approach for CO₂ reduction. To develop a thorough and viable carbon fixing process, we present the method for reducing CO₂ to graphite, which is a critical mineral for modern industries, using active metals [

29]. Particularly, when this carbon fixing method combines with the steam-methane-reforming (SMR) process, which is the technology for 95% commercial hydrogen production, green hydrogen production could become a reality due to the reduction of CO₂ produced in SMR reaction.

Herein, the conversion of CO₂ to graphite using active metals and its application for green hydrogen production using SMR process are presented.

2. CO₂ removal and conversion to graphite via metallurgy process

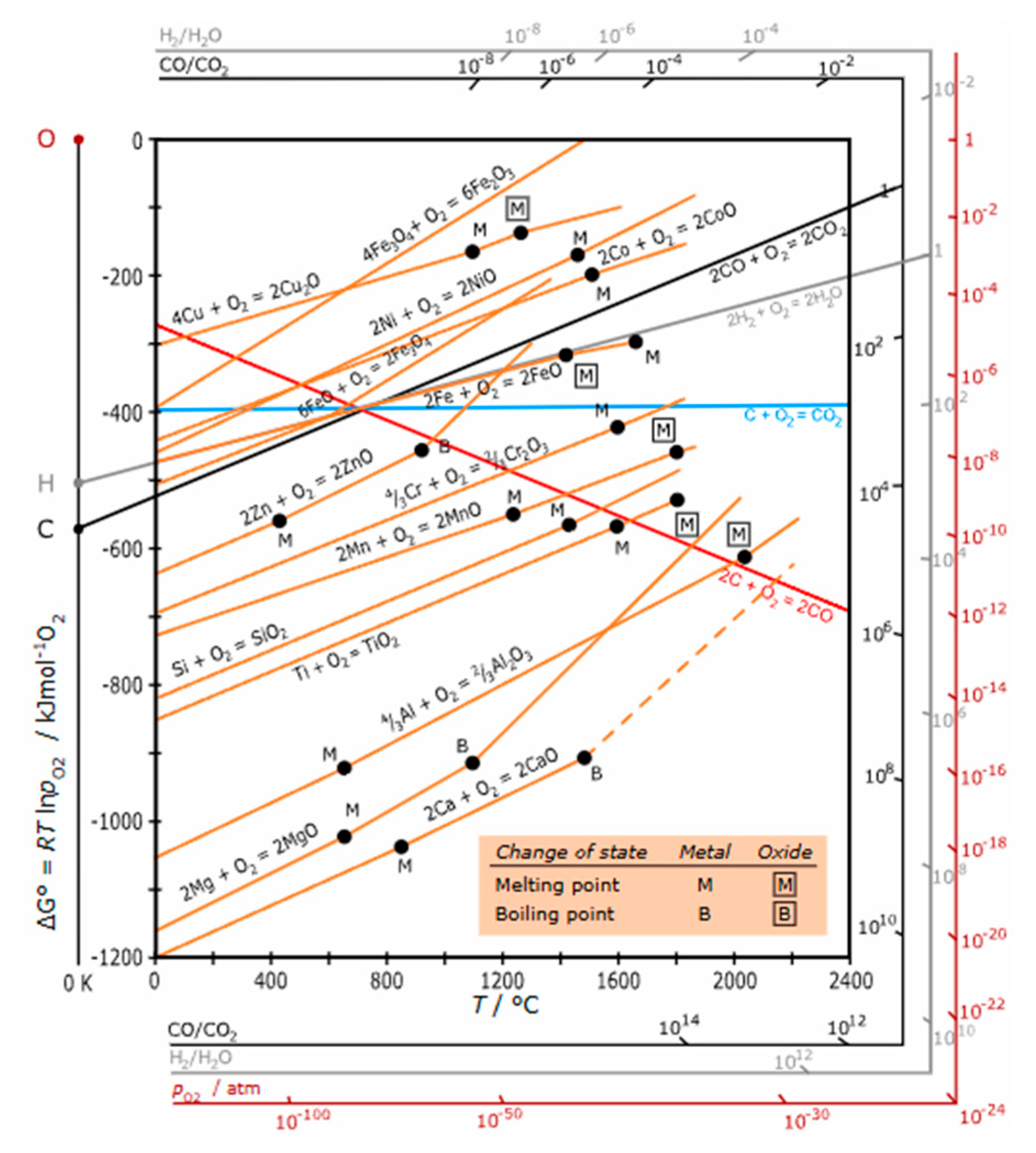

From the Ellingham diagram (

Figure 1) [

30,

31], it is thermodynamically favourable for a metal/element more active than carbon (i.e., the Gibbs free energy change ∆G lines of their oxidation are below those of CO and CO

2 formation under certain temperatures) to reduce CO₂ (and CO) to elemental carbon due to a negative Gibbs free energy change (∆G < 0). Graphite is the most stable phase for carbon under mild pressure and temperature as shown in the carbon phase diagram (

Figure 2) [

32]. Therefore, CO₂ can be reduced to graphite by active metals via metallurgy process as presented in patent [

29].

Taking magnesium as an example, the CO₂ conversion to graphite mechanism can be described as below:

That is, first magnesium reduces CO₂ to CO. Reaction (3) resulting from reactions (1) and (2) is a spontaneous reaction from the Ellingham diagram, which has the most negative Gibbs free energy change ∆G in the carbon, oxygen, and magnesium system. The medium product CO will be further reduced by Mg and fixed as C (graphite) as follow:

Reaction (5) resulting from reactions (2) and (4) is a spontaneous reaction below the temperature of 1800°C from the Ellingham diagram, which has a negative ∆G.

Therefore, the total reaction resulting from reactions (1) to (5) is

where CO₂ is decomposed to C (graphite) and oxygen. The oxygen produced can further react with magnesium according to reaction (2), which leads to

At low temperatures, CO₂ can also react with MgO to form magnesium carbonate MgCO

3, which will reduce the efficiency of CO₂ conversion to C (graphite). Therefore, temperature above the calcination of MgCO

3, i.e., over 350 °C [

33], should be adopted.

Kim et al. reported synthesis of graphene-like materials via combustion of solid magnesium in carbon dioxide [

34]. As seen from reaction (3), CO will be first produced as a middle product. To prevent its escape from the reaction system, liquid magnesium rather than solid magnesium should be employed to seal or lock CO. Another advantage of using liquid magnesium is that larger graphite flake will be obtained due to better crystal growth environment. Thus, reaction (7) can be rewritten as

Using the reduction of CO₂ to graphite/graphene by magnesium to improve the mechanical properties of Mg alloys is a proven method [

35,

36]. Therefore, converting CO₂ to C (graphite) using magnesium is a practical process. Reaction (8) is a huge exothermic process, if it is ignited, no more or little heating energy is required.

MgO obtained from reaction (8) can be recycled to produce metallic magnesium economically due to its high Mg content compared to the minerals for magnesium production, i.e., dolomite

CaMg(CO3)2 and magnesite

MgCO3. There are two practical processes. One is the pyrometallurgy approach, that is, the Silicotermic process [

37], which involves reducing molten magnesium oxide with ferrosilicon under low gas pressure at a temperature around 1400ºC.

The metallic magnesium formed in the process, which has the lowest melting (650 °C) and the lowest boiling point (1,090 °C) among all the alkaline earth metals [

38], evaporates and then condensates away from the hot region. The condensed magnesium has a purity of 99.95% and can be reused for converting CO₂ to graphite.

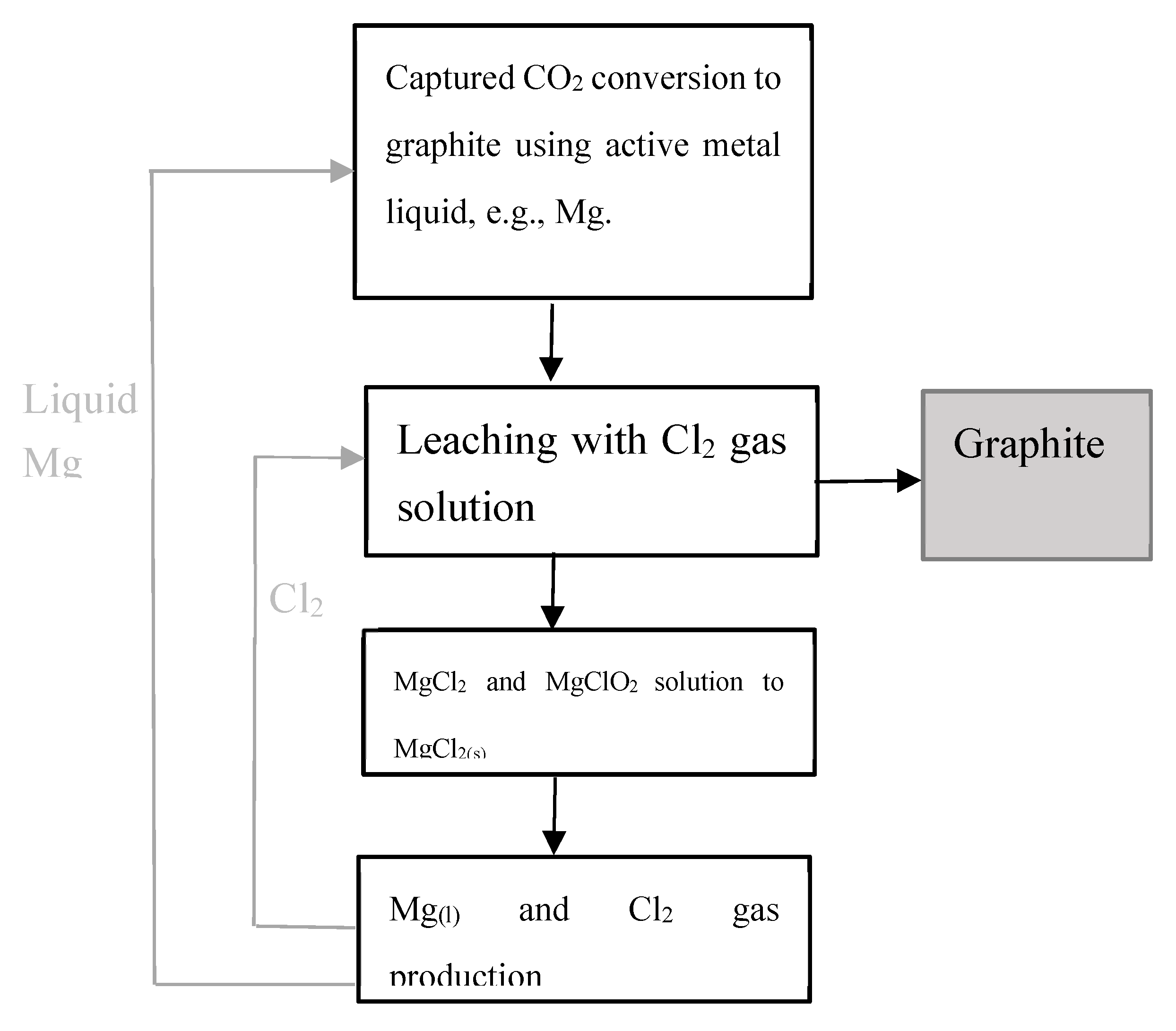

The other approach is recycling Mg through hydrometallurgy process,

In reaction (10), it involves following sub-reactions (11) to (13)

Crystalized Mg(ClO)

2 from leaching solution can be decomposed to MgCl

2 under calcination.

Magnesium chloride MgCl

2 is then used for Mg production in an electrolytic cell through electrolysis:

Metallic magnesium formed at the cathode can be sent to CO₂ conversion to graphite stage. The Cl

2 gas collected in the anode compartment can be recycled to MgO leaching in reaction (10). The principal process for CO₂ fixing and converting to graphite using active liquid magnesium is illustrated in

Figure 3. The cost for graphite production is mainly from the Mg – CO

2 reaction process, and Mg recycling from chlorine leaching and electrolysis process. Graphite is produced in a viable way from this process. Other alkaline metals and alkaline earth metals (such as Na, K, and Ca) and their alloys can work similarly as Mg. However, due to their extremely high activities to oxygen in the air, which leads to spontaneous ignition [

38], magnesium is a safer choice.

If liquid aluminum is used as the reducing agent, then

The recycling of Al from Al₂O

3 may use the similar electrolysis process for aluminum production, however, the anode should not be made of carbon material to prevent the production of CO

2. New anode materials coated with anticorrosion metals or alloys need to be employed.

If carbon anode is used, then C + O2(anode) = CO₂, that is, CO₂ will be regenerated.

With the annual discharge of carbon dioxide as large as 36.8 billion tons, one key consideration for practical CO₂ reduction process should be its scalability. Researchers studied the splitting of CO₂ to carbon (not graphite) using liquid eutectic gallium and indium alloy at temperatures between 25 °C and 500 °C [

39]. With the global gallium production of 616 tons per annum [

40], the reduction of CO₂ using gallium and its alloys would be difficult to commercialize besides the low value of produced carbon. Splitting CO₂ using electrochemical processes is also hard to industrialize due to limited CO₂ reduction capacity on the electrode [

41].

From current knowledge, converting carbon dioxide to valuable graphite using active metal liquid such as liquid magnesium is the most feasible approach for CO2 reduction and control, where the risk of CO forming and escaping can also be avoided.

3. Green hydrogen production via SMR process combined with CO₂ conversion to graphite

Currently, 95% hydrogen is produced using the steam-methane-reforming (SMR) process under the temperature of 800 to 1000 °C and a pressure of 14 to 20 atm over a catalyst bed [

42],

Carbon dioxide in the products can be separated from hydrogen using membrane or CaO/MgO sorption, then discharged to the environment, sealed underground, or stored as liquid CO

2 [

42,

43]. The hydrogen produced from the SMR process is called “blue hydrogen” due to the discharge of CO

2 from reaction (18) and that from the fossil fuel combustion to maintain the required reaction temperature. It is estimated that 9 kg of CO

2 is generated for 1 kg of H

2 produced using SMR process [

43]. From reaction (18), both methane and water contribute the same moles of hydrogen, which means water works equivalently to methane as raw material for hydrogen production. This is the most important merit of the SMR process. It combines the outcomes of methane pyrolysis (CH

4 = C +2H

2) and water electrolysis (2H

+ + 2e = H

2).

For the methane pyrolysis process, catalysts need to be used [

44], and the solid carbon produced will cover the catalysts in short time and deactivate them for further reaction when carbon fully occupies the catalyst surface. Therefore, fouled catalysts need be replaced with new ones from time to time. This incurs the high cost for catalyst replacement or recycling and affects process efficiency.

Green hydrogen produced from water electrolysis only accounts for small percentage (<5%) of hydrogen supply. The process is limited to the availability to green energy, e.g., hydroelectricity, solar energy (however, the production process of solar panels is not green), and wind energy, nonideal energy efficiency, and low hydrogen production capacity from the limited cathode surface [

45].

About 60% of global warming effects are attributed to the carbon dioxide emission [

2]. If the carbon dioxide produced from the SMR process is converted to graphite using the technology presented in patent [

29], the SMR process becomes a greener H

2 production technology. That is, using metal oxides such as CaO or MgO to capture the CO

2 from SMR reaction and that from carbon-containing fuel combustion via reaction (19), purified CO

2 for converting to graphite using active metal liquid is obtained through the calcination of the carbonate by reaction (20), where the metal oxide (CaO at here) can be recycled for the CO

2 capturing and purifying system.

The graphite production is an important merit of the combined process of hydrogen production via SMR reaction coupled with CO₂ conversion. Graphite is a critical mineral, which has extensive applications in modern industries such as battery industry (as electrodes), sealing material for jet engine production, graphene and diamond production (as raw material), and electrical/electronic industry [

46,

47]. Nowadays, the graphite ore grades have been decreasing due to continuous mining, which makes the graphite concentrates produced are hard to reach high purity, usually around 90% to 95% C from mineral processing [

48,

49]. It is predictable that graphite (especially the flaky graphite) resources will be depleted in the very near future. The graphite obtained from the presented carbon dioxide conversion process can reach nearly 100% C grade, and most importantly with much larger flakes due to the favorable crystal growth environment in active metal liquid. Graphite is an even more important critical mineral than lithium for energy storage and conversion. Technologically, lithium could be replaced by sodium and other metals [

50,

51]. However, it is hard to find a substitute of graphite. Using carbon dioxide conversion to graphite with active metals is a proven technology [

35,

36].

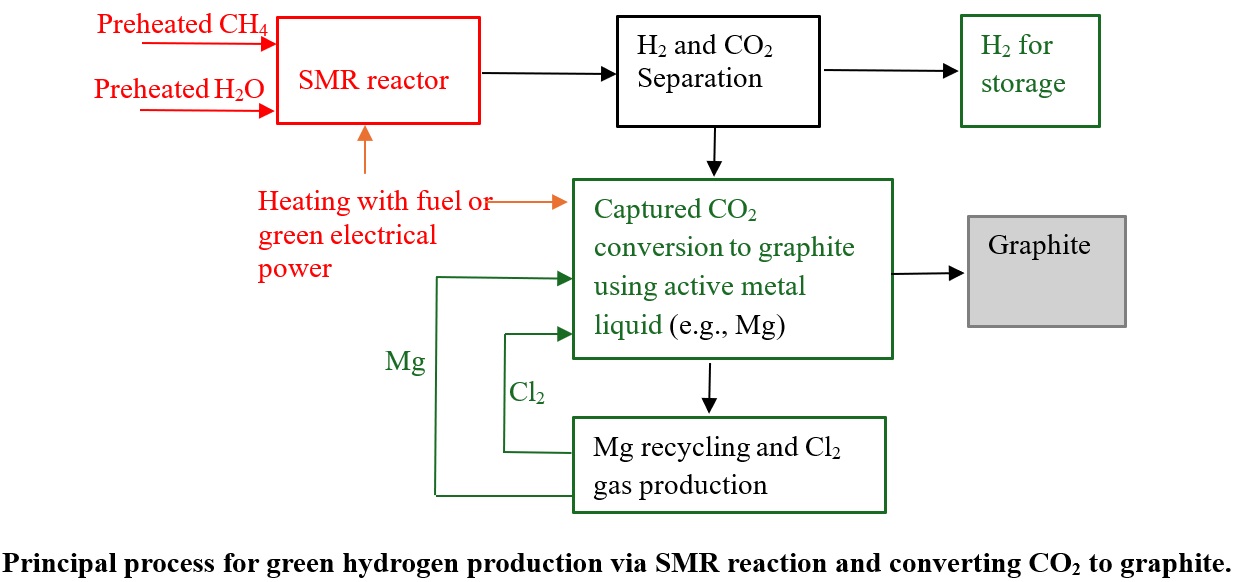

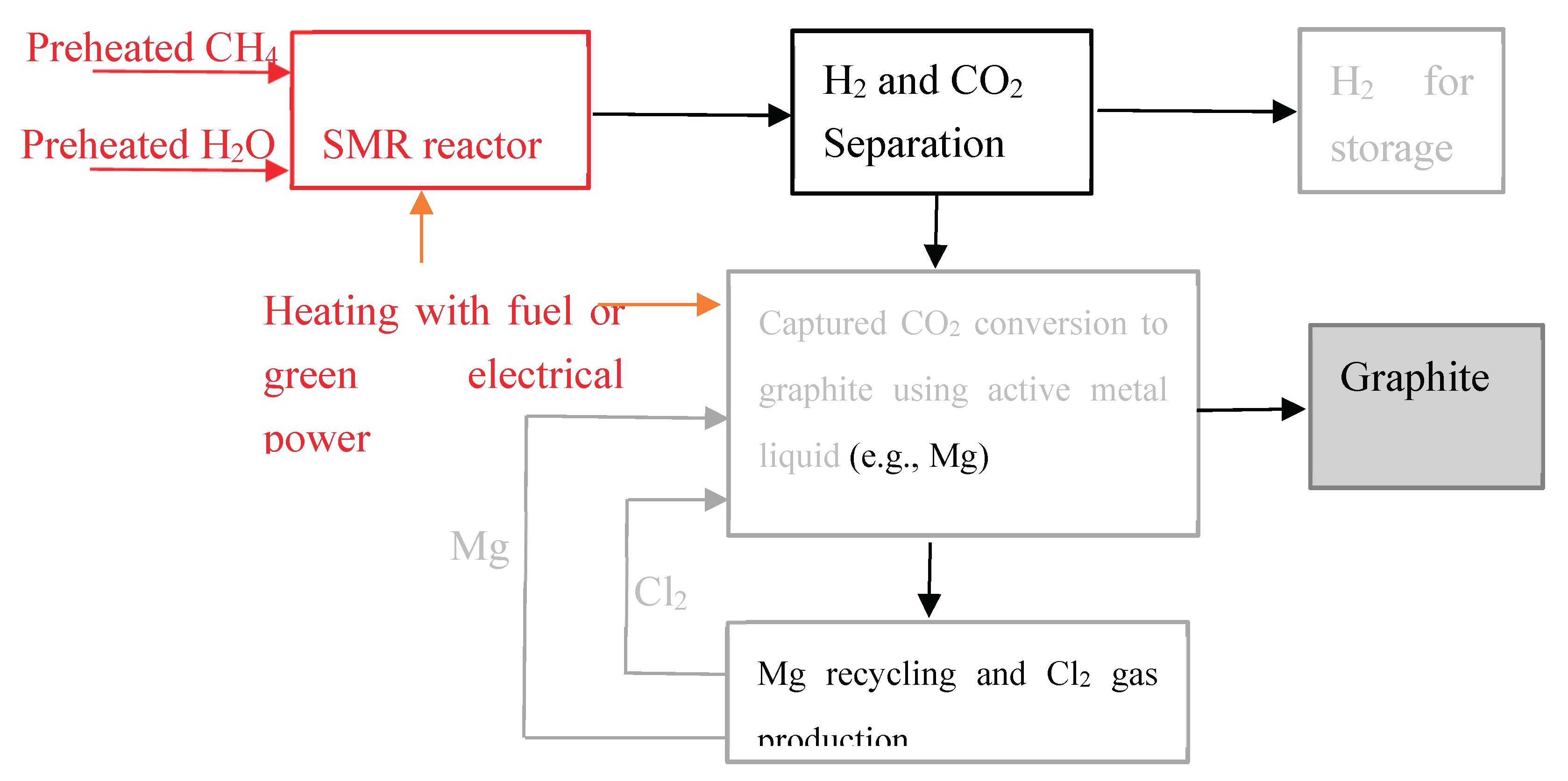

The entire process for greener hydrogen production via SMR reaction and converting carbon dioxide to graphite is illustrated in

Figure 4.

If green energy such as electrical energy from hydro powerplant or nuclear fusion is applied for hydrogen production via SMR process and ignition of CO2 conversion, the entire process will be totally green. Apparently, if hydrogen acts as the major fuel in the future, the green house effects arisen from carbon dioxide emission could be largely solved.

4. Conclusions

The global carbon dioxide discharge is around 40 billion tons per year, primarily from burning fossil fuels. Any processes for CO2 capture and reduction are not thorough tactics if CO2 cannot be converted and fixed to a stable and useful substance.

To process the enormous amount of discharged carbon dioxide, splitting carbon dioxide and converting it to critical mineral graphite using active metal liquid such as liquid magnesium is a feasible and scalable technology for CO2 reduction and control, where the forming and escaping of carbon monoxide from the process is prevented. Chemical reactions and thermodynamics of the presented CO₂ conversion to graphite process are analyzed.

Combining with the CO₂ conversion to graphite technology, SMR process will become a greener hydrogen production process, especially, when clean energy such as electrical energy from hydro powerplant or nuclear fusion is applied for the SMR process production and ignition of CO2 conversion, the entire process will be totally green.

One outstanding advantage of the process is the production of flaky graphite, which is a depleting strategical mineral of extensive applications and demands with high value. That could overcome the cost spent including the recycling of the metals used in CO₂ reduction. This is a technically feasible and economically viable process for H2 production, CO₂ reduction, and graphite production.

There are no technological obstacles for the presented process as all the chemical engineering and metallurgy sub-processes involved, i.e., the SMR process and active metal recycling, are proven and viable.

Author Contributions

Yahui Zhang prepared the paper draft. Hongbo Zeng, Qi Liu, Douglas Ivey, and Kaipeng Wang reviewed the paper and presented their perspectives of the process mechanism and conclusions.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of this work by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) (Funding Application # RGPIN-2023-03921).

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Monastersky, R. Global carbon dioxide levels near worrisome milestone. Nature 497, 13–14 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, A. An overview of CO2 mitigation options for global warming -Emphasizing CO2 sequestration options. Journal of Chemical Engineering of Japan 36, 361–375 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Global Carbon Budget Report 2023. https://globalcarbonbudget.org/fossil-co2-emissions-at-record-high-in-2023/.

- Lindsey, R. (2024) Climate change: Atmospheric carbon dioxide, NOAA Climate.gov. Available at: https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-climate/climate-change-atmospheric-carbon-dioxide (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Aini, N. and Shen, Z. The effect of tree planting within roadside green space on dispersion of CO2 from transportation. International Review for Spatial Planning and Sustainable Development 7, 97–112 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Fornaciari, M., Muscas, D., Rossi, F., Filipponi, M., Castellani, B., Di Giuseppe, A., Proietti, C., Ruga, L., Fabio O. CO2 Emission Compensation by Tree Species in Some Urban Green Areas. Sustainability. 6, p.3515 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Rasowo, J. O., Nyonje, B., Olendi, R., Orina, P., Odongo, S. Towards environmental sustainability: further evidences from decarbonization projects in Kenya’s Blue Economy. Frontiers in Marine Science. 11, 1239862 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Hurd, C. L., Law, C. S., Bach, L. T., Britton, D., Hovenden, M., Paine, E. R., John A. R., Veronica T., Philip W. B. Forensic carbon accounting: Assessing the role of seaweeds for carbon sequestration. Journal of phycology. 8, 347-363 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Awogbemi, O., Dawood A. D. Novel technologies for CO2 conversion to renewable fuels, chemicals, and value-added products. Discover nano. 20, 29-27(2025). [CrossRef]

- Porosoff, M. D., Yan, B., Chen, J. G. Catalytic Reduction of CO2 by H2 for Synthesis of CO, Methanol and Hydrocarbons: Challenges and Opportunities. Energy Environ. Sci. 9, 62–73 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J., Huang, L., Yan, W., Li, J., Liu, C., Lu, X. Theoretical study of the mechanism for CO2 hydrogenation to methanol catalyzed by trans-RuH2(CO)(dpa), Catalysts. 8, 244-253 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Olah, G. A., Goeppert, A., Prakash, G. K. S. Chemical Recycling of Carbon Dioxide to Methanol and Dimethyl Ether: From Greenhouse Gas to Renewable, Environmentally Carbon Neutral Fuels and Synthetic Hydrocarbons. J. Org. Chem. 74, 487–498 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Kortlever R., Balemans C., Kwon Y., Koper M. T. M. Electrochemical CO2 reduction to formic acid on a Pd-based formic acid oxidation catalyst. Catal Today. 244, 58–62 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Moret, S., Dyson, P. J., Laurenczy, G. Direct Synthesis of Formic Acid from Carbon Dioxide by Hydrogenation in Acidic Media. Nat. Commun. 5, 1–7 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Cai, T. et al. Cell-free chemoenzymatic starch synthesis from carbon dioxide. Science. 373, 1523-1527 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. et al. De novo artificial synthesis of hexoses from carbon dioxide. Science bulletin. 68, 2370-2381 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Rochelle, G.T. Amine scrubbing for CO2 capture. Science. 325, 1652–1654 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Luo, X., Guo, Y., Ding, F., Zhao, H., Cui, G., Li, H., Wang, C. Significant improvements in CO2 capture by pyridine-containing anion-functionalized ionic liquids through multiple-site cooperative interactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 7053–7057 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Angelo, V., Davide, A., Nina-Luisa, M., Tomas, A., Kim, T., Gerald, B. Sorbent material for CO2 capture, uses thereof and methods for making same. Patent application No. WO-2023094386-A1 (2023).

- Querejeta, N., Gil, M.V., Rubiera, F., Pevida, C., Wawrzyn´czak, D., Panowski, M., Majchrzak-Kucęb, I. Bio-engineering of carbon adsorbents to capture CO2 from industrial sources: The cement case. Separation and Purification Technology. 330, 125407 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Bai, J. et al. Sulfur-Doped porous carbon Adsorbent: A promising solution for effective and selective CO2 capture. Chemical Engineering Journal. 479, 147667 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Rao, L., Ma, R., Liu, S., Wang, L., Wu, Z., Yang, J., Hu, X. Nitrogen enriched porous carbons from D-glucose with excellent CO2 capture performance. Chemical Engineering Journal. 362, 794-801 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Hou, M., Li, L., Xu, R., Lu, Y., Song, J., Jiang, Z., Wang, T., Jian, X. Precursor-chemistry engineering toward ultrapermeable carbon molecular sieve membrane for CO2 capture. Journal of energy chemistry. 102, 421-430 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Sabouni, R., Kazemian, H., Rohani, S. Carbon dioxide capturing technologies: a review focusing on metal organic framework materials (MOFs). Environ Sci Pollut Res. 21, 5427–5449 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Millward, A.R., Yaghi, O.M. Metal-organic frameworks with exceptionally high capacity for storage of carbon dioxide at room temperature. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 17998–17999 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Peplow, M. The race to recycle carbon dioxide. Nature (London), 603 (7903), 780-783 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Daud, F. D. M., Ahmad, N. A. I., Mahmud, M. S., Sariffudin, N., Zaki, H. H. M. Two-Step Synthesis of Ca-Based MgO Hybrid Adsorbent for Potential CO2 Capturing Application. Materials science forum. 981, 369-374 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Pacciani, R., Müller, C. R., Davidson, J. F., Dennis, J. S., Hayhurst, A. N. Synthetic Ca-based solid sorbents suitable for capturing CO2 in a fluidized bed. Canadian journal of chemical engineering. 86, 356-366 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H., Zhang, Y., Liu, Qi. Wang, K. Process for capture and conversion of carbon dioxide. US Patent Application No. 63/487,510; International Application No. PCT/CA2024/050248 (2024). https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/092589050/publication/WO2024178508A1?q=PCT%2FCA2024%2F050248.

- Ellingham diagram. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ellingham_diagram (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Ellingham, H. J. T. Reducibility of oxides and sulphides in metallurgical processes. Journal of the Society of Chemical Industry 63, 125-160 (1944).

- Carbon-phase-diagramp.svg. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Carbon-phase-diagramp.svg (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Weast, R. C. et al. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (59th ed.). West Palm Beach, FL: CRC Press. p. B-133. ISBN 0-8493-0549-8 (1978). [CrossRef]

- Kim, T. H., Merritt, C. R., Ducati, C., Bond, A. D., Bampos, N., Brown, C. L. Bulk synthesis of graphene-like materials possessing turbostratic graphite and graphene nanodomains via combustion of magnesium in carbon dioxide. Carbon. 149, 582-586 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Shi, H., Wang, X., Hu, X., Xu, C., Shao, W. Direct synthesis and modification of graphene in Mg melt by converting CO2: A novel route to achieve high strength and stiffness in graphene/Mg composites. Carbon. 186, 632-643 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Kim, T. H., Merritt, C. R., Ducati, C., Bond, A. D., Bampos, N., Brown, C.L. Bulk synthesis of graphene-like materials possessing turbostratic graphite and graphene nanodomains via combustion of magnesium in carbon dioxide. Carbon. 149, 582–586 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Che, Y., Zhang, C., Song, J., Shang, X., Chen, X., He, J. The silicothermic reduction of magnesium in flowing argon and numerical simulation of novel technology. Journal of magnesium and alloys. 8, 752-760 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Hanusa, T. P., Phillips, C. S. G. Alkaline-earth metal. Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/alkaline-earth-metal.

- Zuraiqi, K. et al. Direct conversion of CO2 to solid carbon by Ga-based liquid metals. Energy & environmental science. 15, 595-600 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Jaganmohan, M. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1445336/production-of-gallium-worldwide/.

- Hu, L., Song, Y., Jiao, S., Liu, Y., Ge, J., Jiao, H., Zhu, J., Wang, J., Zhu, H., Fray, D. J. Direct conversion of greenhouse gas CO2 into graphene via molten salts electrolysis, ChemSusChem. 9 588–94 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Barelli, L., Bidini, G., Gallorini, F., Servili, S. Hydrogen production through sorption-enhanced steam methane reforming and membrane technology: A review. Energy. 33, 554-570 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Khan, A., Haider, M., Daiyan, R., Neal, P., Haque, N., MacGill, I., Amal, R. A framework for assessing economics of blue hydrogen production from steam methane reforming using carbon capture storage & utilisation. International journal of hydrogen energy. 46, 22685-22706 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Fulcheri, L., Rohani, V., Wyse, E., Hardman, N., Dames, E. An energy-efficient plasma methane pyrolysis process for high yields of carbon black and hydrogen. International journal of hydrogen energy. 48, 2920-2928 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Anwar, S., Khan, F., Zhang, Y., Djire, A. Recent Development in Electrocatalysts for Hydrogen Production through Water Electrolysis. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 46, 32284-32317 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Cermak, M., Perez, N., Collins, M., Bahrami, M. Material properties and structure of natural graphite sheet. Scientific reports. 10, 18672-18672 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Duan, S. et al. Preparation and properties of graphite-based “light–heat–electricity” conversion materials. Applied physics letters. 125, (2024). [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A. K. Literature quest and survey on graphite beneficiation through flotation. Renewable & sustainable energy reviews. 189, 113980 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Zhang, L., Qu, X., Qiu, Y. Beneficiation of a low-grade flaky graphite ore from australia by flotation. Advanced Materials Research. 1090, 188-192 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Nayak, P. K., Yang, L., Brehm, W., Adelhelm, P. From lithium-ion to sodium-ion batteries: advantages, challenges, and surprises. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 57, 102-120 (2018). [CrossRef]

- He, X. et al. Sulfolane-based flame-retardant electrolyte for high-voltage sodium-ion batteries. Nano-micro letters. 17, 45 (2024). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).