1. Introduction

Screening for type 1 diabetes (T1D) is gaining international recognition as a potential component of standard preventive care. While current efforts are largely research-based, several countries are initiating structured implementation strategies. In 2023, Italy became the first country to formally enact a public health policy mandating population-wide pediatric screening for both T1D and celiac disease (CD). The Istituto Superiore di Sanità (ISS), under the directive of the Ministry of Health, launched a government-funded pilot program—D1Ce (Diabete tipo 1 e Celiachia) Screen—across four regions (Lombardia, Marche, Campania, and Sardegna) [

1]. This initiative aims to assess feasibility, acceptability and operational challenges of large-scale screening, with major focus on sample collection and autoantibody detection, serving as a foundational step toward a future nationwide implementation [

1].

The main purpose of type 1 diabetes (T1D) screening programs is to detect individuals at risk or in early disease stages, enabling preventive interventions. Demonstrated benefits include a significant reduction in diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) at diagnosis (i.e., from 15–80% to below 5%), with consequent improvement in acute morbidity, neurocognitive impairment and mortality [

2]. Screening also ameliorates short-term clinical outcomes and reduces hospitalization, and contributes to better psychological adjustment, as parents of screened children report lower anxiety levels at diagnosis [

3]. Beyond these immediate benefits, recent advances in immunotherapy, such as the approval of teplizumab for delaying the onset of clinical T1D, have expanded the relevance of early identification strategies. These developments have renewed interest in feasibility and potential impact of population-based screening programs, aiming not only to improve diagnosis but also to enable timely preventive interventions [

4,

5].

Islet autoantibodies recognizing four major pancreatic autoantigens are currently clinically available, and consist of anti-insulin autoantibodies (IAA), anti-glutamate decarboxylase autoantibodies (GADA), anti-insulinoma antigen-2 autoantibodies (IA-2A), and anti-zinc transporter protein 8 antibodies (ZnT8A) [

6,

7]. These tests represent the screening targets recommended by the most recent American Diabetes Association (ADA) Standards of Care [

8]. The presence of two or more autoantibodies in the context of normoglycemia defines Stage 1 T1D. Stage 2 is instead characterized by the same serological profile in association with dysglycemia, in the absence of clinical symptoms. Stage 3 corresponds to the clinical onset of T1D, with hyperglycemia meeting diagnostic criteria established by the ADA [

9,

10]. Various methods have been proposed for detection of anti-TDM1 antibodies, including radioimmunoassay (RIA) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) [

11]. Although the RIA technique is extremely sensitive and specific, it requires specialized equipment, special precautions, and licensing since radioactive substances are used. For this reason, most of laboratories worldwide are increasingly abandoning this analytical technology.

ELISA has hence emerged as the primary detection method due to its quantitative capabilities and straightforward procedure [

12,

13]. Nonetheless, ELISA still possesses certain limitations inherent to traditional immunological detection techniques, such as the need for multiple operational steps, extended time requirements, and high costs [

14]. Additionally, achieving rapid sample detection in clinical settings can be challenging with ELISA [

15]. To address these limitations, the chemiluminescence immunoassay (CLIA) detection technology has gained popularity as a new and mainstream clinical immunoassay method [

16]. CLIA comprises the following steps: a) labeling an antigen or an antibody with a chemiluminescence-related substance; b) separating a free chemiluminescence-related marker after a specific antigen-antibody reaction; c) adding other related substances of a chemiluminescence-related system to generate chemiluminescence; and d) performing qualitative or quantitative detection on labeled antigen or antibody. CLIA has gained widespread use in clinical disease diagnosis, particularly for tumor biomarker and autoantibody detection, owing to its rapid detection speed, ease of operation, and high sensitivity and specificity. As a result, it could be applied in pharmaceutical control, clinical diagnostics, and environmental monitoring. It is now regarded as the best alternative to ELISA and RIA [

17].

Despite the increased focus on D1T antibody assays, data from methods comparison are limited. Moreover, The Islet Autoantibody Standardization Program (IASP) has recently observed discrepancies of positive/negative scores and ranking of antibodies levels across assays and formats across laboratories around the world, thus heightening the need of more standardized procedure for these assays [

18]. This study was hence aimed at comparing the diagnostic performance of CLIA and ELISA in detecting the presence of three autoantibodies, with the purpose of identifying a more accurate, rapid, automated, and convenient method for the implementation of screening programs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Assessment of Comparability Between Methods

A total of 104 serum specimens, covering the most clinically relevant range of Anti-GAD, Anti-ZnT8, and Anti-IA-2 antibodies assays, were collected from the sample of children and adolescents with new-onset T1D or undergoing screening as first-degree relatives, and collected in the PRECIMED-VR Biobank of the Regional Center for Pediatric Diabetes of Verona (Italy). The samples were analyzed at the Service of Laboratory Medicine, University Hospital of Verona (Italy). The ELISA assays used in clinical practice were compared with MAGLUMI™ 800 CLIA on residual and previously anonymized specimens after ELISA testing was completed, using identical test aliquots. The study was cleared by the local Ethical Committee (Verona and Rovigo provinces; protocol number: 971CESC, date of approval: 25 July, 2016). The analytical characteristics of the assays are summarized in

Table 1.

The overall positive and negative percent agreement and Cohen's κ coefficient were calculated to demonstrate the concordance between the two assays. Standard formulae have been used to calculate percent agreement and relative sensitivity and specificity of results by the CLIA method, considering ELISA as the reference standard. κ values lower than 0.40 mean poor agreement, values between 0.40 and 0.60 moderate agreement, those between 0.60 and 0.80 good agreement, and values over 0.80 excellent agreement. After assessment of variables distribution by Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, Spearman correlation analysis was used for identifying the correlation between methods. Proportional and/or constant bias were assessed with Passing-Bablok regression and Bland-Altman analysis. Deviation from linearity was detected by the Cusum test. The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 26.0 statistical software (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and Graph Pad 10.4.2 (San Diego, CA, USA).

2.2. Assessment of Precision and Linearity

Intra-assay variability was assessed by performing ten replicate measurements on aliquots of two serum pools for each class of major islet antibodies, with one pool having analyte concentrations below and the other above the established positivity cut-off. The resulting coefficients of variation (CVs) were compared with those provided by the CLIA manufacturer, which have been assessed with three human serum pools and internal control materials containing different analyte concentrations, each measured in duplicate. Linearity was evaluated by preparing serial dilutions (ranging from 1:10 to 10:1) of high-titer serum samples for GADA, ZnT8A, and IA-2A, each diluted with the corresponding low-titer serum pool specific for each class of major islet antibodies. All dilutions were tested in triplicate, and values were averaged.

3. Results

3.1. Precision and Linearity

Table 2 shows the results of the imprecision study. The obtained values were generally consistent with those provided by the manufacturer, whose declared coefficients of variation (CVs) ranging from 0.5% to 4.5%.

Using the protocol described above, assay linearity was assessed within the range of 12 to 270 IU/mL for ZnT8A, 2.3 to 300 IU/mL for GADA, and 5 to 413 IU/mL for IA-2A. The assay demonstrated excellent linearity for ZnT8A and GADA (Spearman’s correlation coefficients of 0.992 and 0.999, respectively), and a good linearity for IA-2A (Spearman’s correlation coefficient of 0.962).

3.2. Comparability Between Methods

For each of the three autoantibodies tested (GADA, IA-2A, and ZnT8A), 104 serum samples were analyzed, spanning broad concentration ranges of each analyte (<1 to >2000 for ZnT8A; <0.2 to >2000 for GADA; and <2 to >1000 for IA-2A). The CLIA and ELISA methods showed strong cumulative agreement, with ZnT8A displaying the highest inter-assay concordance. The positive and negative agreement rates, as well as the Cohen’s kappa coefficient (based on dichotomizing results at the manufacturers’ cut-off values), are summarized in

Table 3

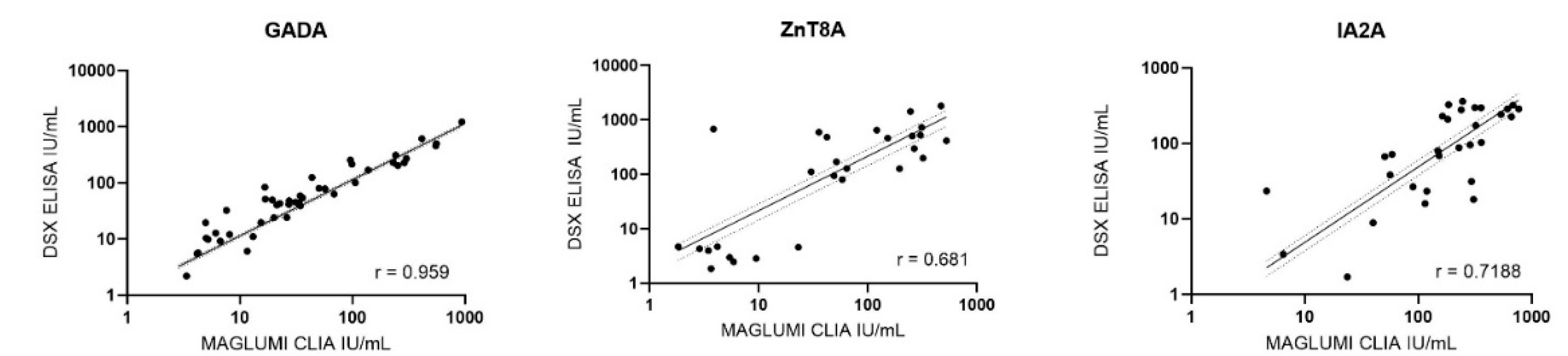

Passing-Bablok regression was used for samples within the measurable range of each assay in order to compare CLIA and ELISA measurements for GADA, IA-2A, and ZnT8A antibodies. No significant deviation from linearity was observed in any of these comparisons (Cusum test, p > 0.05), indicating that a linear model was appropriate. The regression slopes revealed systematic differences between the methods. For GADA (n = 52) and ZnT8A (n = 31), CLIA yielded systematically lower concentrations than ELISA, with slopes significantly below 1 (95% CI: 0.6952–0.8242 and 0.4594–0.5427, respectively). Contrarily, CLIA values were higher than ELISA for IA-2A (n = 30), with slope significantly above 1 (95% CI: 1.6891–2.6813). Spearman’s rank correlation analysis (

Figure 1) yielded a strong correlation for GADA (r = 0.959) and moderately strong correlations for IA-2A (r = 0.719) and ZnT8A (r = 0.681). All correlation coefficients were statistically significant (p < 0.001).

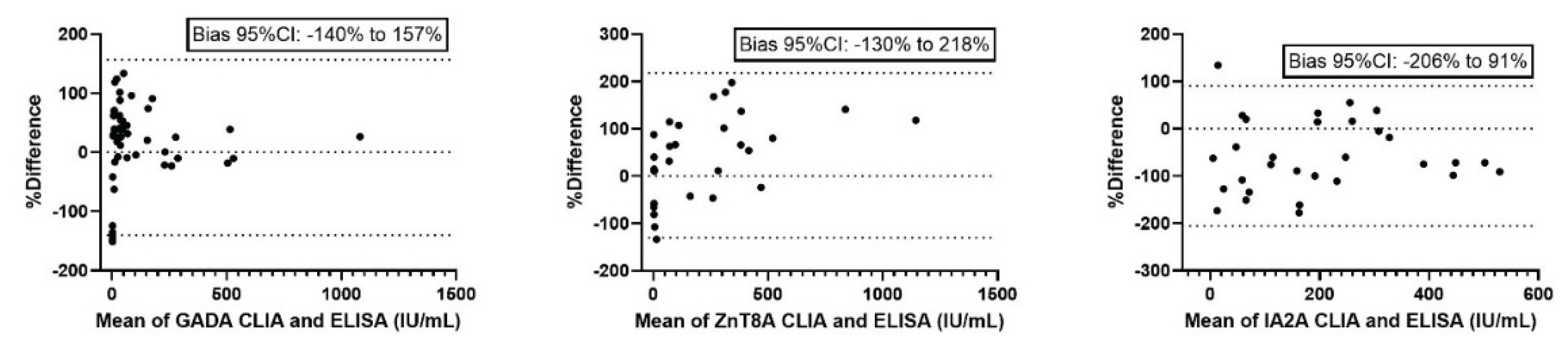

Bland-Altman analysis (

Figure 2) was used to further assess the agreement between methods, revealing a relative dispersion of values, with broad 95% CIs.

4. Discussion

The screening for islet autoantibodies is now primarily conducted within programs targeting children, adolescents, and adults who are at increased risk of developing T1D due to either having a first-degree relative with T1D or carrying a known high-risk HLA genotype [

7,

19]. Periodic monitoring of individuals who test positive for one or more islet autoantibodies is cost-effective and feasible using ELISA-based methods, given the relatively limited number of samples involved. Nevertheless, up to 90% of individuals who eventually develop T1D do not belong to these predefined at-risk groups, so that population-based screening initiatives are being launched, substantially increasing the number of samples to be analyzed. Regional screening programs could result in a shift from processing a few thousand samples per year to over twenty-fold samples annually. In this context, the use of traditional ELISA methods becomes impractical due to their limited scalability and lack of full automation. There is hence urgent need for availability of new, fully automated and standardized platforms to efficiently monitor islet autoantibodies status at regional and population-wide levels. Among the currently available alternative methods, dissociation-enhanced lanthanide fluorescence immunoassay (DELFIA) and CLIA appear to be the most promising options [

20,

21].

In this study, we evaluated the analytical concordance and the quantitative agreement between CLIA and ELISA assays for measurement of anti-GAD, IA-2, and ZnT8 autoantibodies in a cohort of serum samples covering a broad dynamic range. Our findings offer valuable insights into the comparability of these two commonly used immunoassay platforms, highlighting both strengths and potential limitations associated with their interchangeability. We also verified the precision and linearity of GADA, ZnT8A and IA-2A CLIA assays on MAGLUMI 800.

The present study demonstrates a strong total agreement between CLIA and ELISA methods for measurement of GADA, IA-2A, and ZnT8A autoantibodies, with Cohen’s kappa coefficients consistently indicating excellent concordance. Notably, ZnT8A exhibited the highest agreement between methods, while GADA showed slightly lower concordance, particularly in terms of negative agreement. Despite these encouraging findings, method comparison analyses revealed significant proportional biases. Passing-Bablok regression proved that, while a linear relationship was maintained, CLIA systematically underestimated antibodies concentrations for GADA and ZnT8A and overestimated those for IA-2A compared to ELISA. This trend was further supported by Bland-Altman analysis, which highlighted mean biases of +8% for GADA, +44% for ZnT8A, and –57% for IA-2A, indicating a substantial variation in both bias magnitude and direction across analytes. This suggests that, although CLIA and ELISA generate highly correlated data, the presence of systematic proportional differences precludes their direct interchangeability for quantitative assessment.

Our findings are in line with previous observations by Plebani et al. [

22], who reported a detectable proportional bias between the MAGLUMI™ 2000 Plus CLIA and the EUROIMMUN Anti-GAD ELISA for GADA quantification. In their study, the CLIA method systematically underestimated GADA concentrations compared to ELISA, despite both assays being calibrated against the World Health Organization (WHO) 1

st Reference Reagent 97/550. Similarly, in our analysis, Passing-Bablok regression and Bland-Altman plots revealed a significant proportional bias, with CLIA underestimating GADA levels relative to ELISA.

By extending the analysis performed by Plebani et al. [

22], to ZnT8A and Ia-2A assays, we also showed a persistent substantial proportional bias between methods. In particular, the positive bias for ZnT8A and the negative bias for IA-2A highlight that the magnitude and direction of discrepancy may vary considerably depending on the specific auto-antibodies analyzed.

This was the first study evaluating the comparability between ELISA and CLIA for the three antibodies against three major pancreatic autoantigens. The major strengths of this study include the evaluation of a substantial number of samples across a wide dynamic range and the application of complementary statistical approaches—Passing-Bablok regression, Spearman’s correlation, and Bland-Altman analysis to comprehensively assess method comparison.

However, of the 104 samples collected for each class of major islet antibodies, several results were below or above the measurable range of one or both ELISA and CLIA assays. Therefore, to avoid misinterpretation of results, only results within the measurable range of each assay were included in the quantitative analyses, which may have excluded extreme values potentially relevant in clinical practice. A further limitation of this study is that only three out of the four antibodies recommended for autoimmune screening in type 1 diabetes were assessed. Evaluation of insulin autoantibodies (IAA) was precluded by the absence of samples exceeding the established positivity threshold among those analyzed during routine laboratory testing.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that CLIA and ELISA assays for GADA, IA-2A, and ZnT8A exhibit strong agreement and high correlation coefficients. Although significant proportional biases between methods limit their quantitative interchangeability, our findings support the use of CLIA assays in clinical practice for detection of islet autoantibodies, including in the context of large-scale screening initiatives, due to their automation, rapidity and overall reliability. Nonetheless, major efforts are still needed to increase the harmonization of serum antibodies values generated by these two techniques.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Cl.M. and G.L.; methodology, E.D.; software, C.M.; formal analysis, E.D.; investigation, C.P., M.R., E.T., E.M., L.P. and GLS; data curation, E.D.; writing—original draft preparation, E.D.; writing—review and editing, C.P., Ca.M., Cl.M. and G.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was cleared by the local Ethical Committee (Verona and Rovigo provinces; protocol number: 971CESC, date of approval: 25 July, 2016).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived because anonymized residual samples were used to perform the same diagnostic tests with a different assay as originally requested for clinical purposes.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| T1D |

type 1 diabetes |

| CD |

celiac disease |

| DKA |

diabetic ketoacidosis |

| ELISA |

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| CLIA |

chemiluminescence Immunoassays |

| RIA |

radioimmunoassay |

| GADA |

anti-glutamate decarboxylase autoantibody |

| IA-2A |

anti-insulinoma antigen-2 autoantibody |

| ZnT8A |

anti-zinc transporter protein 8 antibody |

| IAA |

anti-insulin autoantibody |

| IASP |

Islet Autoantibody Standardization Program |

| DELFIA |

Dissociation-enhanced lanthanide fluorescence immunoassay |

| CVs |

coefficients of variation |

| |

|

| |

|

References

- Cherubini, V.; Mozzillo, E.; Iafusco, D.; Bonfanti, R.; Ripoli, C.; Pricci, F.; Vincentini, O.; Agrimi, U.; Silano, M.; Ulivi, F.; et al. Follow-up and monitoring programme in children identified in early-stage type 1 diabetes during screening in the general population of Italy. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2024, 2024 26, 4197–4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherubini, V.; Grimsmann, J.M.; Åkesson, K.; Birkebæk, N. H.; Cinek, O.; Dovč, K.; Gesuita, R.; Gregory, J. W.; Hanas, R.; Hofer, S. E.; et al. Temporal trends in diabetic ketoacidosis at diagnosis of paediatric type 1 diabetes between 2006 and 2016: results from 13 countries in three continents. Diabetologia. 2020, 63, 1530–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sims, E.K.; Besser, R.E.J.; Dayan, C.; Geno Rasmussen, C.; Greenbaum, C.; Griffin, K.J.; Hagopian, W.; Knip, M.; Long, A.E.; Martin, F.; et al. NIDDK Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet Study Group. Screening for Type 1 Diabetes in the General Population: A Status Report and Perspective. Diabetes. 2022 71, 610-623.

- Herold, K.C.; Bundy, B.N.; Long, S.A.; Bluestone, J.A.; Di Meglio, L.A.; Dufort, M.J.; Gitelman, S.E.; Gottlieb, P.A, .; Krischer, J.P.; Linsley, P.S.; et al. Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet Study Group. An Anti-CD3 Antibody, Teplizumab, in Relatives at Risk for Type 1 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 603-613.

- Sims, E.K.; Bundy, B.N.; Stier, K.; Serti, E.; Lim, N.; Long, SA.; Geyer, SM.; Moran, A.; Greenbaum, C.J.; Evans-Molina, C.; et al. Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet Study Group. Teplizumab improves and stabilizes beta cell function in antibody-positive high-risk individuals. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabc8980.

- Krischer, J.P.; Lynch, K.F.; Schatz, D.A.; Ilonen, J.; Lernmark, Å.; Hagopian, W.A.; Rewers, M.J.; She, JX.; Simell, O.G.; Toppari, J.; et al. TEDDY Study Group. The 6 year incidence of diabetes-associated autoantibodies in genetically at-risk children: the TEDDY study. Diabetologia. 2015, 58, 980-987.

- Ziegler, A.G.; Rewers, M.; Simell, O.; Simell, T.; Lempainen, J.; Steck, A.; Winkler, C.; Ilonen, J.; Veijola, R.; Knip, M.; et al. Seroconversion to multiple islet autoantibodies and risk of progression to diabetes in children. JAMA. 2013, 309, 2473–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 3. Prevention or Delay of Diabetes and Associated Comorbidities: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2025. Diabetes Care. 2025, 48 (Supplement_1), S50–S58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Insel, R.A.; Dunne, J.L.; Atkinson, M.A.; Chiang, J.L.; Dabelea, D.; Gottlieb, P.A.; Greenbaum, C.J.; Herold, K.C.; Krischer, J.P.; Lernmark, Å.; et al. Staging presymptomatic type 1 diabetes: a scientific statement of JDRF, the Endocrine Society, and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2015, 38, 1964–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 2. Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2025. Diabetes Care. 2025, 48(Supplement_1), S27-S49.

- So, M.; Speake, C.; Steck, A. K.; Lundgren, M.; Colman, P. G.; Palmer, J. P.; Herold, K. C.; Greenbaum, C. J. Advances in type 1 diabetes prediction using islet autoantibodies: beyond a simple count. Endocr. Rev. 2021, 42, 584–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lequin, R.M. Enzyme immunoassay (EIA)/enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Clin. Chem. 2005, 51, 2415–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tighe, P.J.; Ryder, R.R.; Todd, I.; Fairclough, L.C. ELISA in the multiplex era: potentials and pitfalls. Proteomics Clin. Appl. 2015, 9, 406–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engvall, E. The ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Clin. Chem. 2010, 56, 319–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhajj, M.; Zubair, M.; Farhana, A. Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay. 2023, In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024. [PubMed]

- Cinquanta, L.; Fontana, D.E.; Bizzaro, N. Chemiluminescent immunoassay technology: what does it change in autoantibody detection? Auto Immun. Highlights. 2017, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khattar, R.B.; Nehme, M.E. Emergence and evolution of standardization systems in medical biology laboratories. Adv. Lab. Med. 2024, 5, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzinotto, I.; Pittman, D.L.; Williams, A.J.K.; Long, A.E.; Achenbach, P.; Schlosser, M.; Akolkar, B.; Winter, W.E.; Lampasona, V.; participating laboratories. Islet Autoantibody Standardization Program: interlaboratory comparison of insulin autoantibody assay performance in 2018 and 2020 workshops. Diabetologia. 2023, 66, 897–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krischer, J.P.; Liu, X.; Lernmark, Å.; Hagopian, W.A.; Rewers, M.J.; She, J.X.; Toppari, J.; Ziegler, A.G.; Akolkar, B.; TEDDY Study Group. Predictors of the Initiation of Islet Autoimmunity and Progression to Multiple Autoantibodies and Clinical Diabetes: The TEDDY Study. Diabetes Care. 2022, 45, 2271-2281.

- Passariello, L.; Iannilli, A.; Santarelli, S.; Federici, L.; De Laurenzi, V.; Cherubini, V.; Pieragostino, D. Development and validation of a novel method for evaluation of multiple islet autoantibodies in dried blood spot using dissociation-enhanced lanthanide fluorescent immunoassays technology, specific and suitable for paediatric screening programmes. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025, 27, 414–418. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mulla, F.; Alhomaidah, D.; Abu-Farha, M.; Hasan, A.; Al-Khairi, I.; Nizam, R.; Alqabandi, R.; Alkandari, H.; Abubaker, J. Early autoantibody screening for type 1 diabetes: a Kuwaiti perspective on the advantages of multiplexing chemiluminescent assays. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1273476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosma, C.; Padoan, A.; Plebani, M. Evaluation of precision, comparability and linearity of MAGLUMI TM 2000 Plus GAD65 antibody assay. J. Lab. Precis. Med. 2019, 4, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).