1. Introduction

Piezo1 is a large, mechanically activated ion channel that plays a key role in cellular mechanotransduction and, in terms of cellular response, converting mechanical stimuli into electrochemical signals across a wide range of cell types [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. It acts as a non-selective cation channel permeable to Ca²⁺; mechanical forces trigger its opening, leading to calcium influx and the activation of downstream signaling pathways [

6]. In human red blood cells (RBCs), Piezo1 is endogenously expressed and plays a crucial role in cell volume regulation by activating the calcium-sensitive Gárdos channel and potentially other effectors [

7,

8,

9].

Beyond its physiological functions, Piezo1 dysfunction is associated with Hereditary Xerocytosis, a rare hemolytic but mostly compensated anaemia, caused by gain-of-function mutations in Piezo1, characterized by dehydrated RBCs [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

Although Piezo1 is directly gated by mechanical forces, its activation is strongly influenced by the physical and chemical properties of the surrounding membrane. Even in the absence of cytoskeletal constraints, membrane features such as curvature, lipid composition, and cholesterol content can modulate channel sensitivity by altering local tension and bilayer stress [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. These properties help explain the diversity in Piezo1 activity across different cell types and environments.

Small molecules such as Yoda1 and its analog Yoda2 have emerged as important pharmacological tools for modulating Piezo1 activity. Rather than bypassing mechanical activation, these compounds stabilize the channel in open or pre-open conformations, thereby lowering the threshold for mechanical activation [

21,

22]. Their effects are context-dependent and shaped by factors such as membrane architecture, curvature, and lipid environment [

17,

20,

23].

In this study, we investigate the pharmacological activation of Piezo1 in human RBCs using Yoda1 and Yoda2. By integrating high-throughput electrophysiology, calcium imaging, and assays of Gárdos channel activity, we compare their potency and characterize downstream responses in this unique native cell type. These findings offer new insight into the context-dependent pharmacology of Piezo1 activators and their applicability in RBCs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Blood Collection and Preparation

All measurements were performed on freshly drawn venous blood obtained from healthy donors as approved by the ethics vote of the “Ärztekammer des Saarlandes” (reference number 51/18). For the patch clamp measurements, whole blood was diluted in the external recording solution. For Ca2+ and membrane potential measurements, RBCs were washed three times in Tyrode (solution composition below) or 0.9% NaCl solution, respectively. RBCs were centrifuged at 3880 RCF for 5 minutes. The plasma supernatant was removed, and the RBC pellet was diluted with the respective solution. This washing step was repeated twice with gentle mixing of the pellet and subsequent centrifugation performed between each wash. Blood samples were used for experiments within 3 hours of withdrawal.

2.2. Automated Patch Clamp Recordings

Whole-cell patch clamp recordings were performed using the SyncroPatch 384 (Nanion Technologies, Germany) as previously described [

24] . Experiments were conducted at room temperature using NPC-384 single-hole microchips with resistances ranging from 6 to 10 MΩ. Recording solutions contained (in mM): 110 KF, 10 KCl, 10 NaCl, 10 EGTA, and 10 HEPES, pH: 7.2 (KOH) (internal) and 140 NaCl, 4 KCl, 2 CaCl

2, 1 MgCl

2, 5 D-glucose monohydrate, and 10 HEPES, pH: 7.4 (NaOH) (external). Data acquisition was conducted using PatchControl384 v3.2.2 (Nanion Technologies, Germany), sampled at 10 kHz.

Piezo1-mediated currents were elicited using a voltage ramp protocol ranging from −100 mV to +80 mV over 450 ms, applied every 10 s, with a holding potential set at −30 mV. After establishing a stable baseline current in the external solution, cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of either Yoda1 or Yoda2 (Tocris Bioscience, UK) in a cumulative manner: 41 nM, 144 nM, 442 nM, 1.33 µM, 4 µM and 8 µM. To block channel activity, 30 μM GdCl₃ (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany), a non-selective ion channel inhibitor, was subsequently applied.

Cells exhibiting a seal resistance greater than 0.5 GΩ were selected for analysis. Cells were classified as responders if the mean current amplitude at the three highest compound concentrations exceeded the mean current at baseline conditions by more than three times the standard deviation of the baseline (3σ). For EC₅₀ determination, current amplitudes at each concentration were normalised to the baseline current, and dose-response curves were fitted using the Hill equation.

2.3. Calcium Imaging and Flow Cytometry

Experiments for intracellular Ca2+ detection of RBCs were performed in Tyrode solution containing (in mM): 130 NaCl, 5 KCl, 5 glucose, 10 HEPES, 1 MgCl2 and 1.5 CaCl2, pH was adjusted to 7.38 by NaOH. All salts were of analytical grade. The cells were loaded with Fluo-4 AM (Molecular Probes, USA) at a concentration of 5 μM for 1 h at 37°C. Then, the cells were washed three times with Tyrode solution.

Flow cytometry measurements were performed on LSRFortessa (Becton Dickinson, USA). Washed RBCs from 50 μl blood were loaded with Fluo-4 as previously described [

25] and washed again. For flow cytometry analysis, 10 μl of cell suspension was added to 700 μl designed buffer and transferred to 5 ml round bottom polystyrene test tubes (Corning Inc., USA). For each sample, data recording started 1 min after cells were applied into the designed buffer for 10 min. The results were assessed using FlowJo (Becton Dickinson, USA).

For calcium imaging, RBCs from 10 μl blood were washed three times in Tyrode solution. Then cells were loaded with Fluo-4 as described above and washed again. For calcium images, 50 μl of cell suspension were added to 450 μl Tyrode solution and transferred to µ-Dishes (ibidi, Germany). Ca2+ images were acquired by a Leica STELLARIS 5 microscope (Leica Microsystems, Germany) with a HC PL APO 63x/1.40-0.60 oil objective (Leica Microsystems, Germany). Time-lapse acquisition was performed with a 488 nm laser recording a z-stack every 30 s starting 90 s after the compounds were applied to the cells.

2.4. Membrane Potential Measurement

The membrane potential of RBCs was measured using a method originally described by Macey

et al. [

26], subsequently refined by Poul Bennekou, e.g. [

27], and later optimized by the group of Stéphane Egée, e.g. [

28]. As such, the method is referred to as MBE method after the three scientists who most contributed to it [

29]. For each experiment, a 2 ml Eppendorf tube was prepared containing 1 ml of Ringer solution containing (in mM): 153 NaCl, 2 KCl, and 4 CaCl₂. All reagents were of analytical grade and dissolved in Milli-Q water. 1.66 µl of the protonophore carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP). The tube was placed in a 36°C water bath, and a magnetic stir bar was added to ensure continuous mixing. A calibrated pH electrode was immersed in the solution to monitor pH changes in real time, with data acquisition and recording performed via software on a connected computer. One minute after the start of pH recording, 150 µl of packed RBCs were added to the tube. At 1.5 minutes following RBC addition, the test compound (either Yoda1 or Yoda2) was introduced at the desired concentration. The system was monitored for an additional 5 minutes to observe the effects of the compound on the RBCs. Finally, 80 µl of Triton X-100 were added to lyse the RBCs, in order to establish a reference condition corresponding to a membrane potential of 0 mV.

The membrane potential (Vm) was calculated from the recorded pH data using the following equation:

Vm [mV] = -61.5 x (pHval - pHlys),

where pHval is the pH value measured at a specific time point, and pHlys is the final pH value obtained after cell lysis.

2.5. Data Analysis and Statistics

DataControl 384 v3.2.1 (Nanion Technologies, Germany) was used for the analysis of automated patch clamp data. n represents the number of responding cells out of the total number of valid cells, and N indicates the number of independent NPC-384 chips. Microscopic images were processed by Fiji (ImageJ). Membrane potential data were analysed using Excel (Office 365, Microsoft Corporation, USA), MATLAB (R2023a, MathWorks, USA). Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 10 (v10, GraphPad software, USA). Throughout the paper, data are presented as mean values with error bars indicating the standard error of the mean (SEM). Origin (v2023b, OriginLab Corporation, USA) and Prism were used for the presentation of the data.

3. Results

3.1. Patch Clamp Recordings

High-throughput automated patch clamp recordings were conducted to compare the electrophysiological effects of the Piezo1 activators Yoda1 and Yoda2 in RBCs. Due to the heterogeneity of the RBCs, such as variability in cell age and ion channel expression, responses to different concentrations of Piezo1 agonists can vary among individual cells, complicating precise EC₅₀ determination from single-dose exposures. To address this, a cumulative concentration approach was used, in which each cell was sequentially exposed to either increasing concentrations of the compound (Yoda1 or Yoda2) or the reference solution (external solution + 0.1% DMSO). This approach allowed the assessment of individual responsive cells across the entire concentration range, thereby increasing the number of data points per cell and improving the reliability of potency estimations.

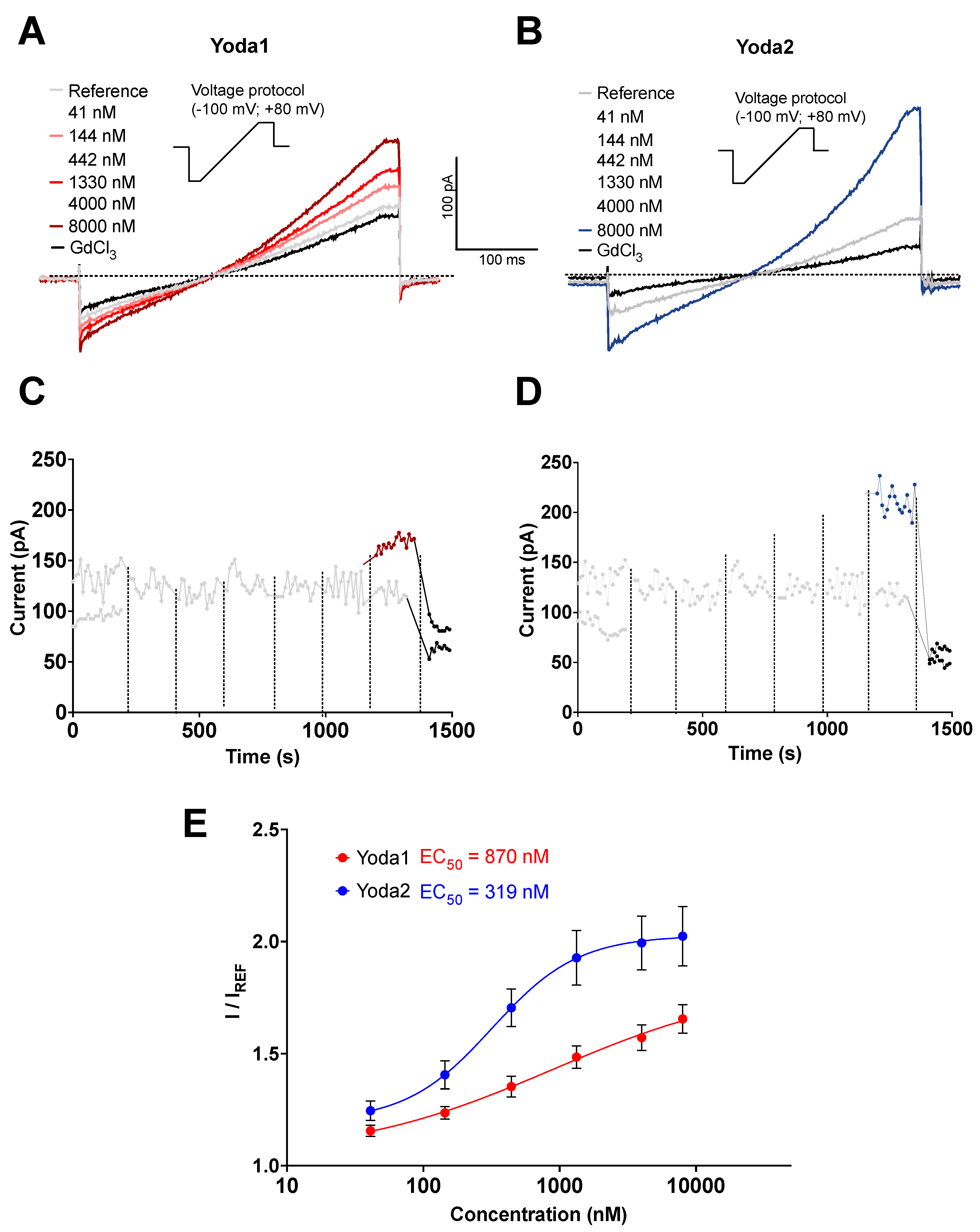

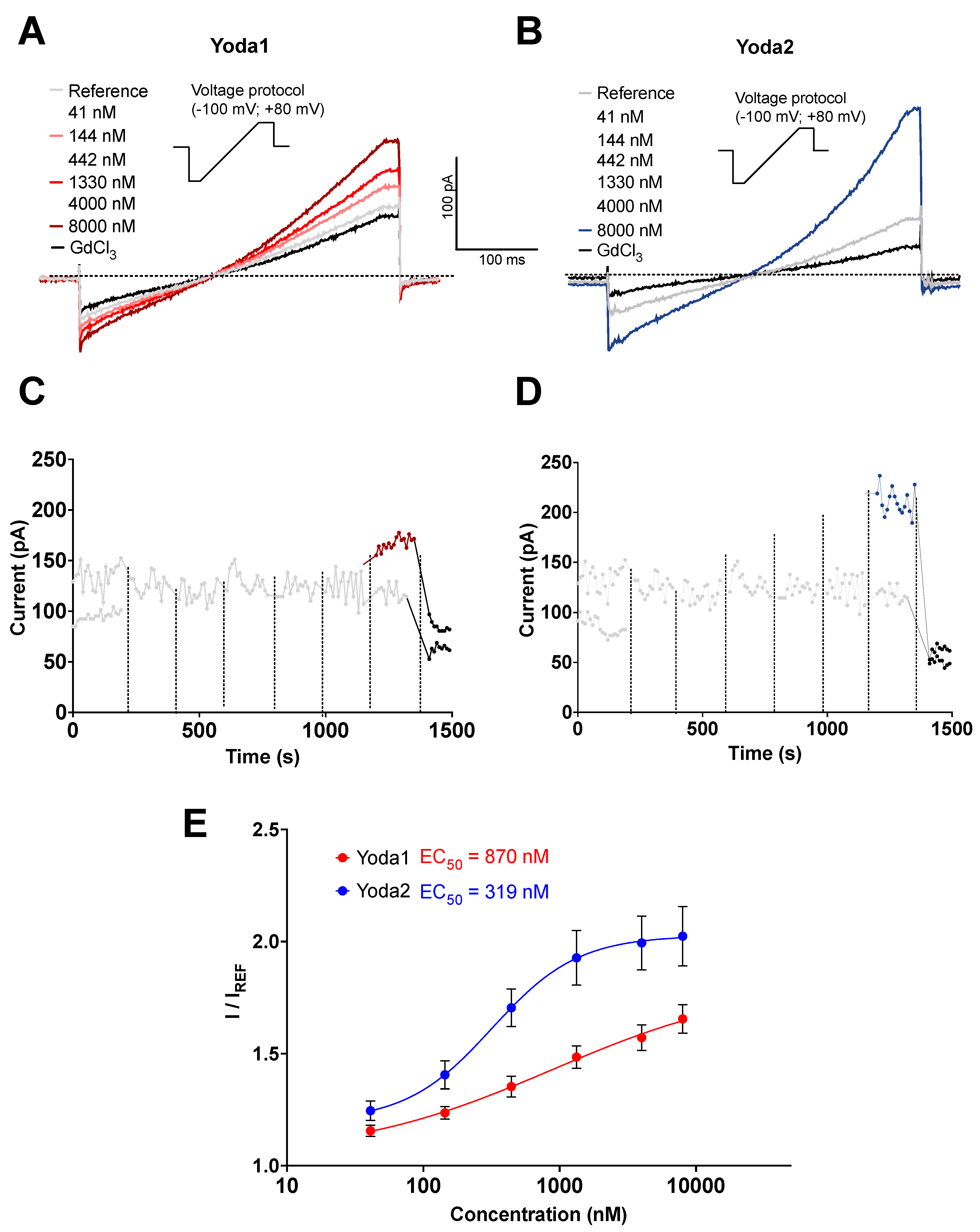

Measurements are presented in

Figure 1 with analysis at membrane potentials of +80 mV. Under control conditions, where only the reference solution was applied, currents remained stable throughout the recording period (

Figure 1C–D, grey traces), confirming that the mechanical stress generated by fluid exchange alone was insufficient to activate the channels. In contrast, both Yoda1 (

Figure 1A, 1C, red traces) and Yoda2 (

Figure 1B, 1D, blue traces) elicited concentration-dependent currents, consistent with Piezo1 activation.

Figure 1C,D shows the currents at +80 mV. Moreover, Yoda1 induced a gradual increase in current amplitude across all tested concentrations (

Figure 1A, 1C), while Yoda2 evoked a more step-like current increase, with the current plateauing at concentrations above 1 μM (

Figure 1B, 1D). This plateau suggests that Yoda2 may reach channel saturation at lower concentrations than Yoda1. The analysis is based exclusively on responding cells. The statistics of the responding cells is presented in

Appendix A (

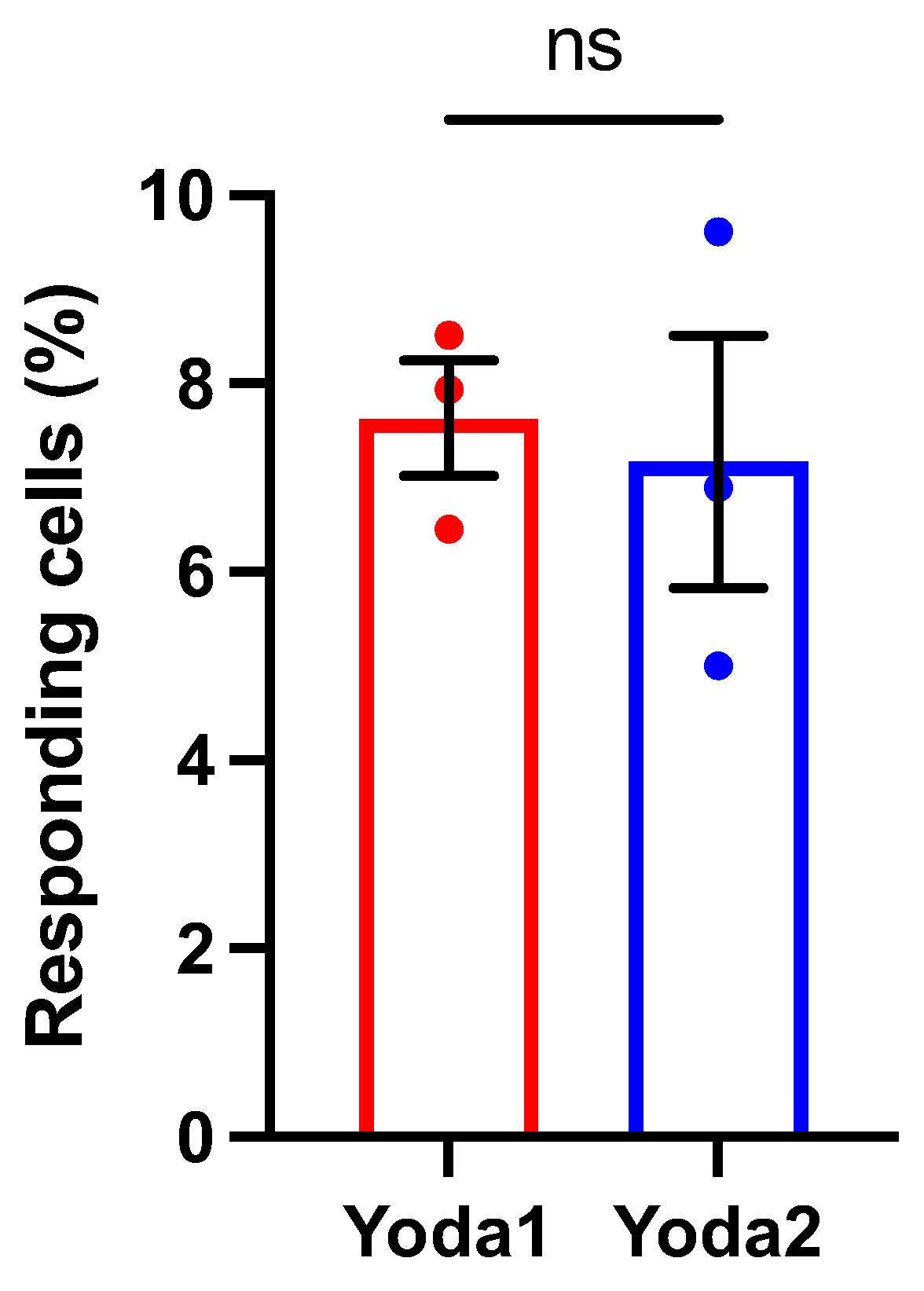

Figure A1).

Normalised concentration–response curves (

Figure 1E) confirmed the higher potency of Yoda2, with an estimated EC₅₀ of 319 nM compared to 880 nM for Yoda1. At every matched concentration, Yoda2 elicited larger mean current amplitudes than Yoda1. The fraction of responding cells was comparable between the two compounds (

Figure A1).

These results demonstrate that both Yoda1 and Yoda2 activate Piezo1 channels in RBCs in a dose-dependent manner, with Yoda2 exhibiting higher potency and efficacy. These findings position Yoda2 as a valuable pharmacological tool for modulating Piezo1 activity in RBCs, particularly in patch clamp assays where its stronger activation profile enhances detection sensitivity and functional characterization.

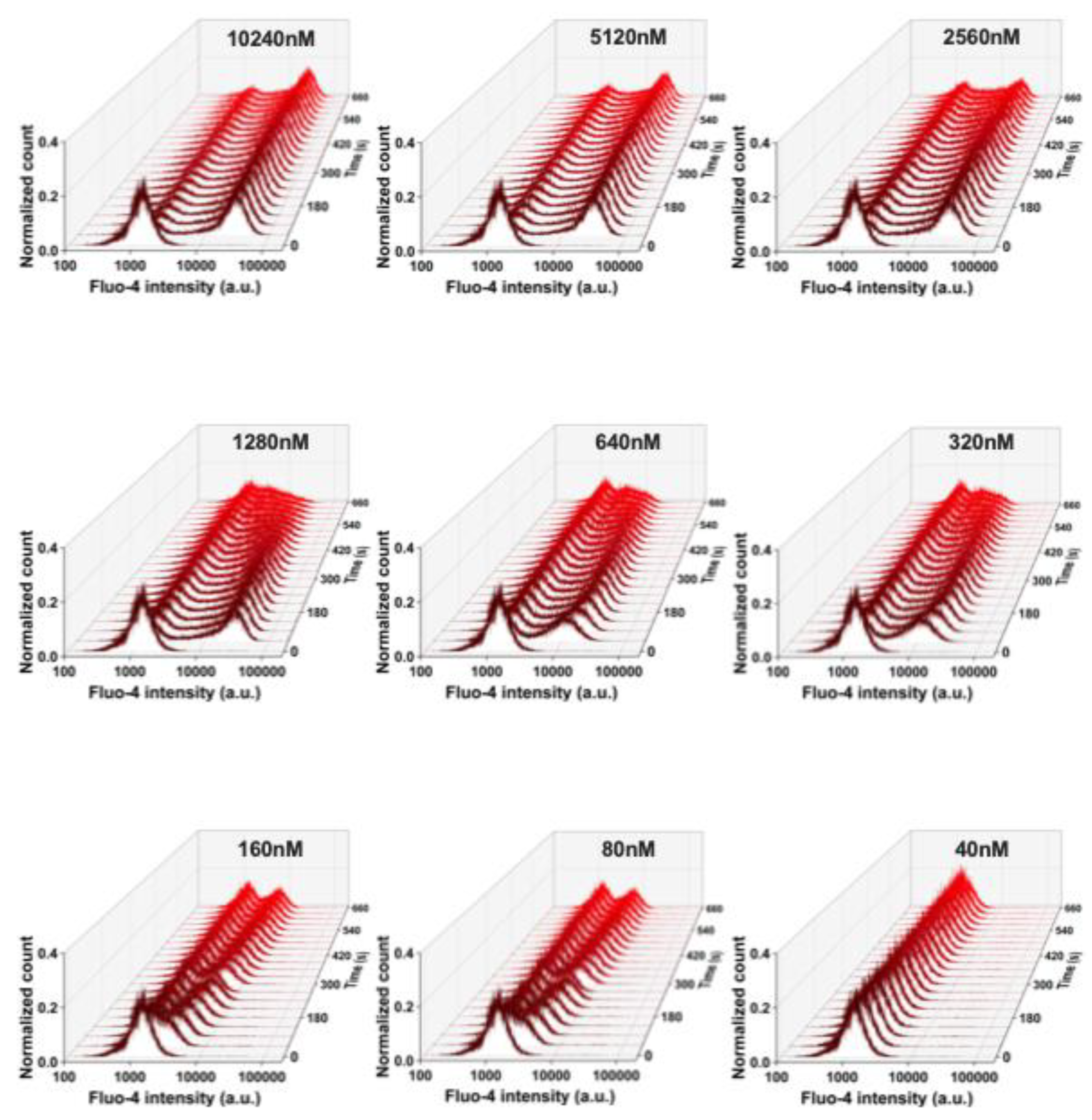

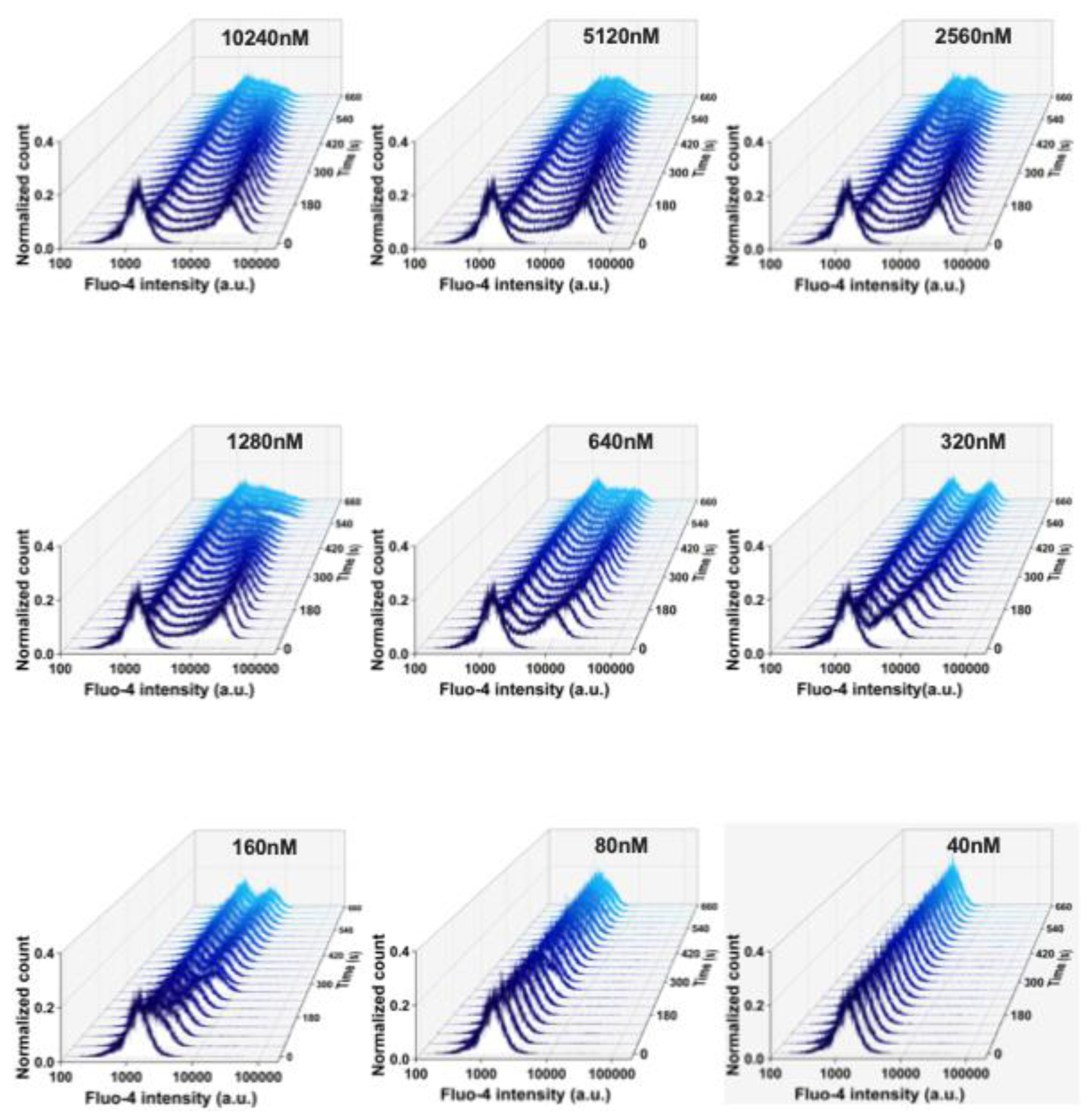

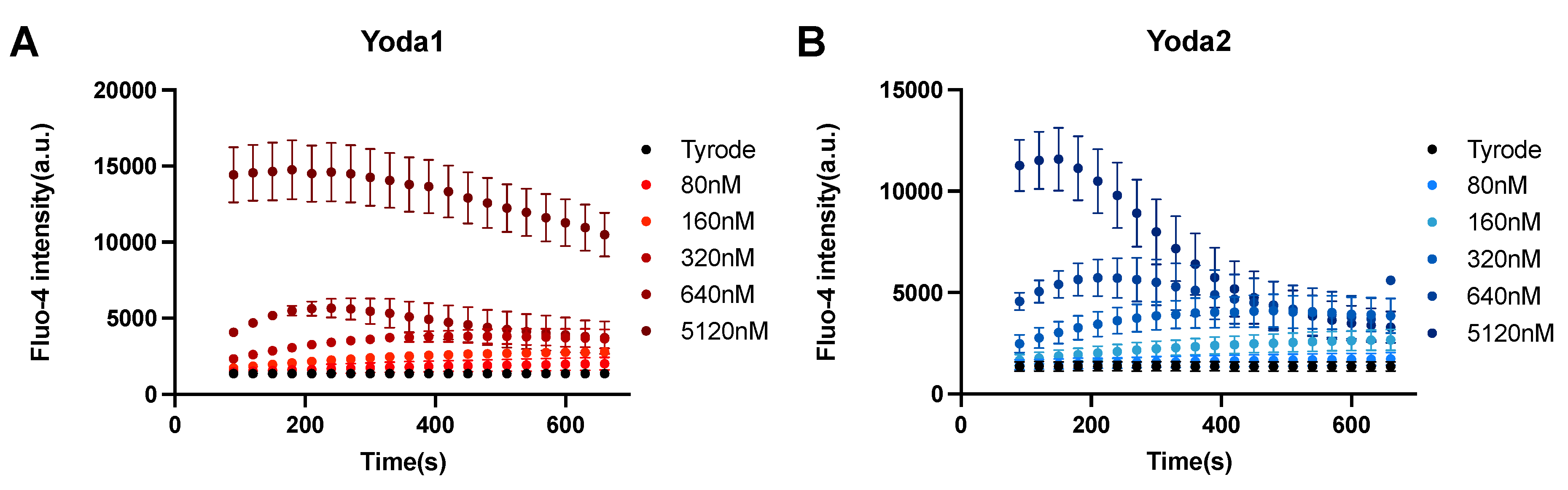

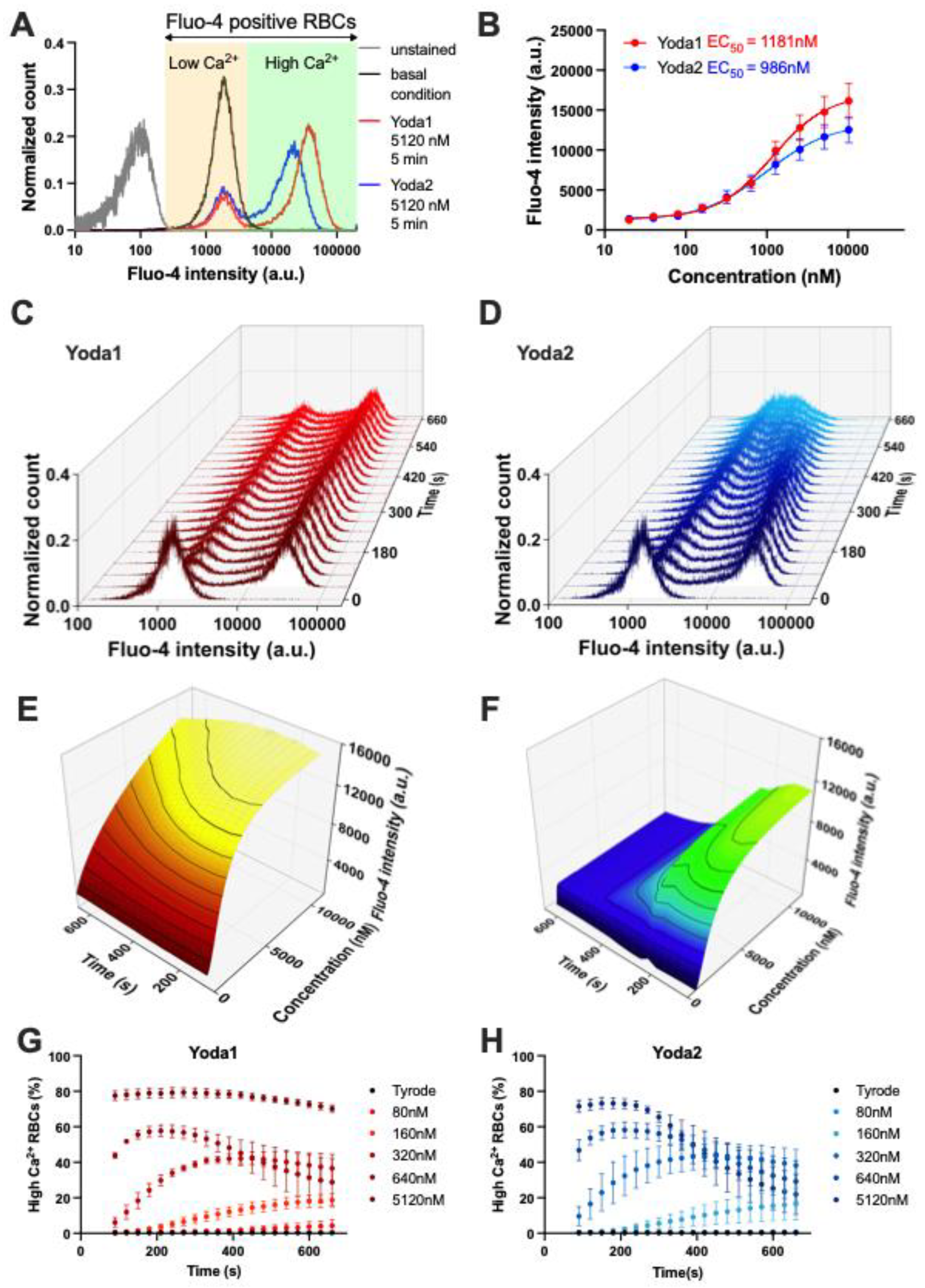

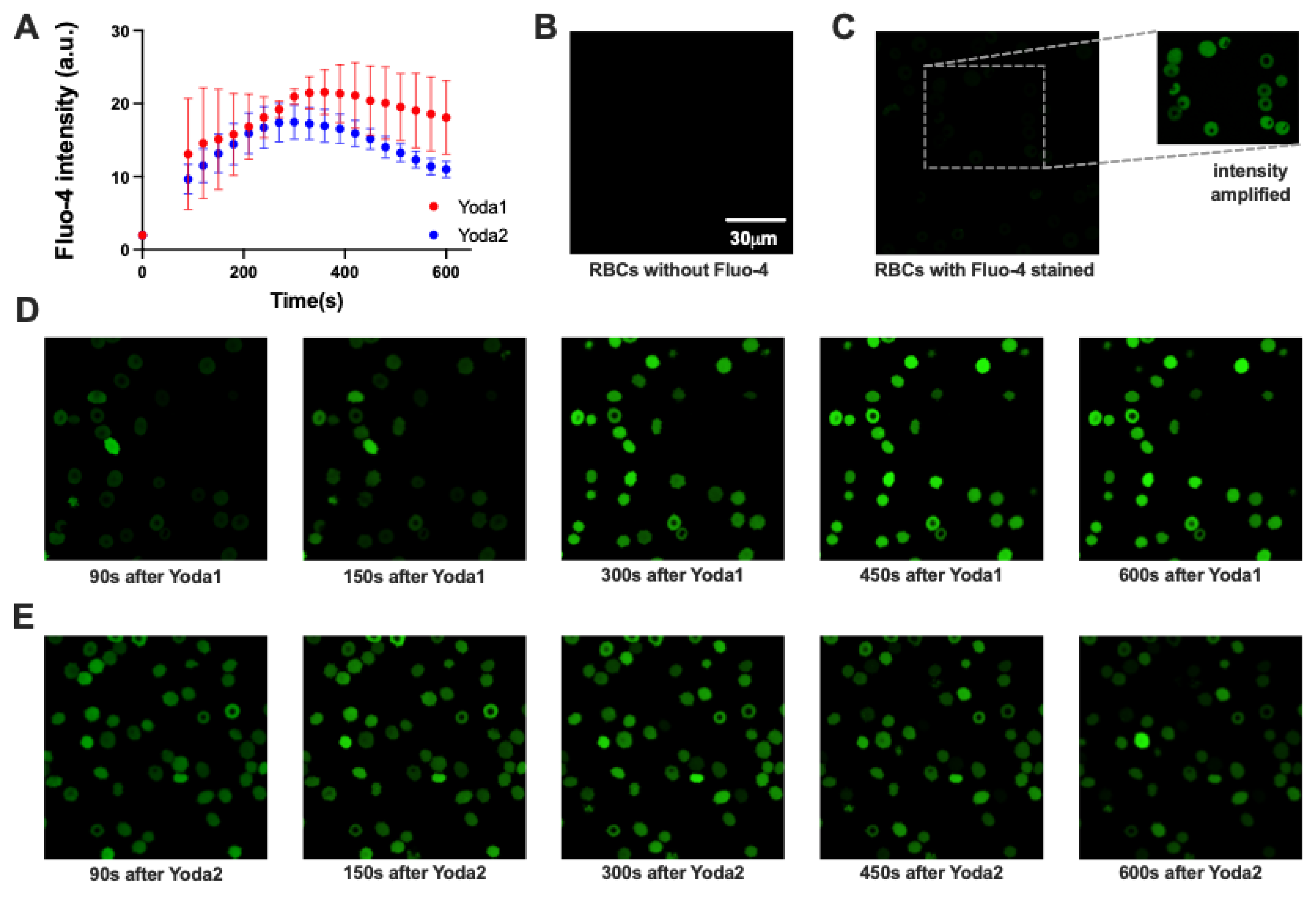

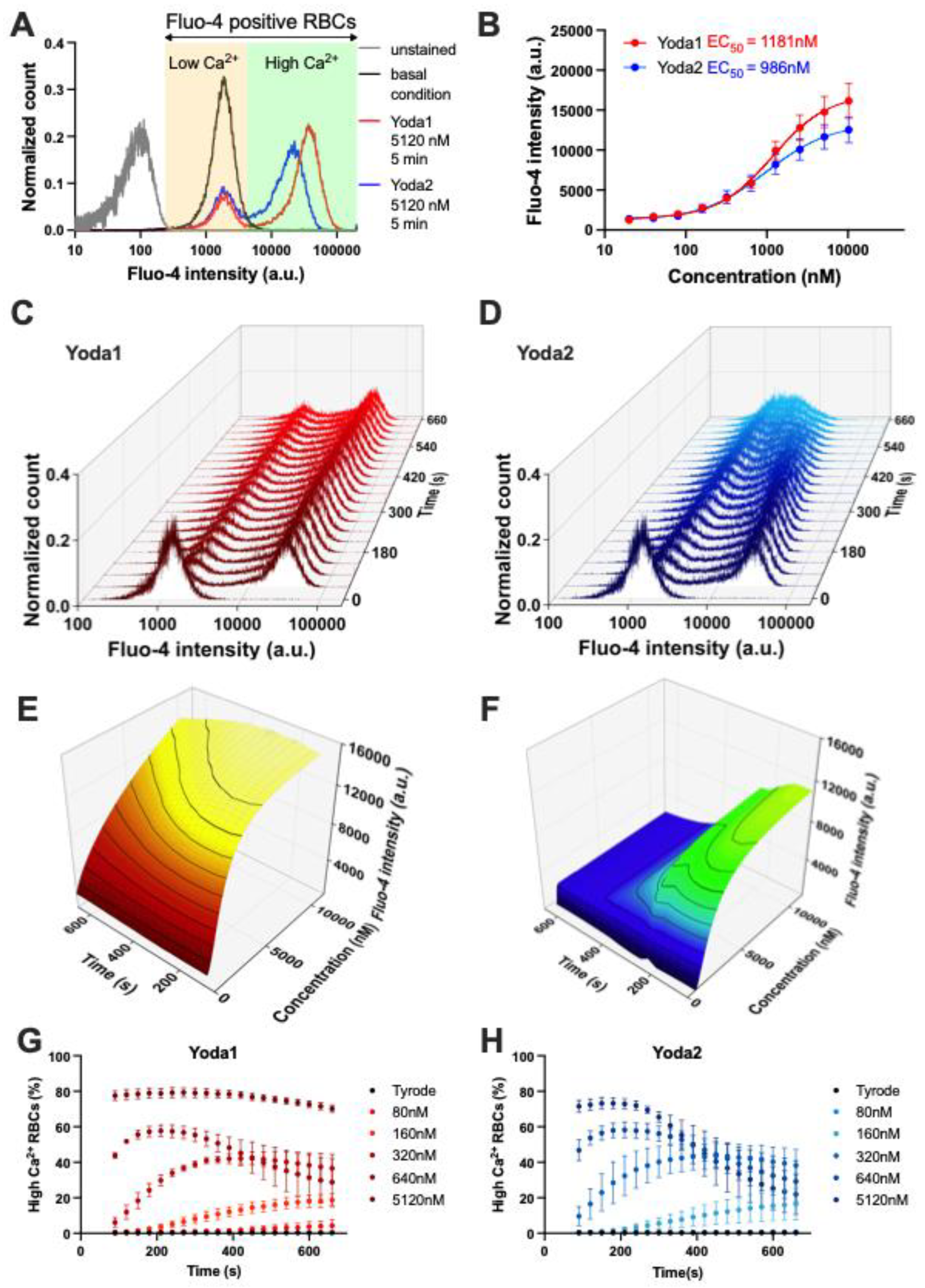

3.2. Calcium Measurements

As a non-selective cation channel, activation of Piezo 1 leads to Ca²⁺ entry, increasing intracellular Ca²⁺. When Fluo-4-stained RBCs were challenged with Yoda1 or Yoda2, a group of RBCs showed increased Fluo-4 intensity, indicating an increased intracellular Ca²⁺ concentration (

Figure 2). Yoda2-induced high Ca²⁺ RBCs had a lower average Fluo-4 intensity than those induced by Yoda1 stimulation (

Figure 2). While the full characterisation of the cells with all Yoda concentrations was performed in flow cytometry (

Figure 2 and

Appendix B,

Figure A2,

Figure A3 and

Figure A4), part of the measurements were performed by microscopic Ca

2+ imaging (

Figure 3) to test if the shear and the putative mechanical stress RBCs experience in the flow cytometer had an influence on the measurements. The flow cytometry and the confocal imaging gave consistent results. The average Fluo-4 intensity of high Ca²⁺ RBCs decreased over time when the Yoda1 or Yoda2 concentration was above 1.28 µM. In addition, the high Ca²⁺ concentration was maintained for longer and decreased more slowly in Yoda1-induced high Ca²⁺ RBCs compared to Yoda2 (

Figure A2 and

Figure A3, respectively). When stimulated, RBCs were challenged with 640 nM Yoda1 or Yoda2, the average Fluo-4 intensity initially increased and then decreased. When RBCs were challenged with 320 nM Yoda2, the Fluo-4 intensity of the high Ca²⁺ population increased over time, whereas the Yoda1-induced high Ca²⁺ population showed increased Fluo-4 intensity, followed by decreased Fluo-4 intensity, after approximately 150 seconds. When RBCs were stimulated with a lower dose of Yoda1 or Yoda2, the Fluo-4 intensity of the high Ca²⁺ population increased over time, and the RBCs showed no obvious response to Yoda2 at 80 nM or Yoda1 at 40 nM (

Figure A2 and

Figure A3). Additionally, the percentage of the high Ca²⁺ population exhibited a similar trend to the average Fluo-4 intensity (Figure 2G,H).

Due to changes in the intracellular Ca²⁺ concentration of the high Ca²⁺ population, the average Fluo-4 intensity of all RBCs changes over time. The fitted Hill equation and the extracted EC

50 are changing over time (

Figure 2D). The maximum average Fluo-4 intensity of all RBCs in each experiment was extracted and used to fit the Hill equation. The S-curve of Yoda2 has a lower plateau than that of Yoda1. The EC

50 of Yoda2 is 986 nM, which is smaller than that of Yoda1 (1181 nM) (

Figure 2B).

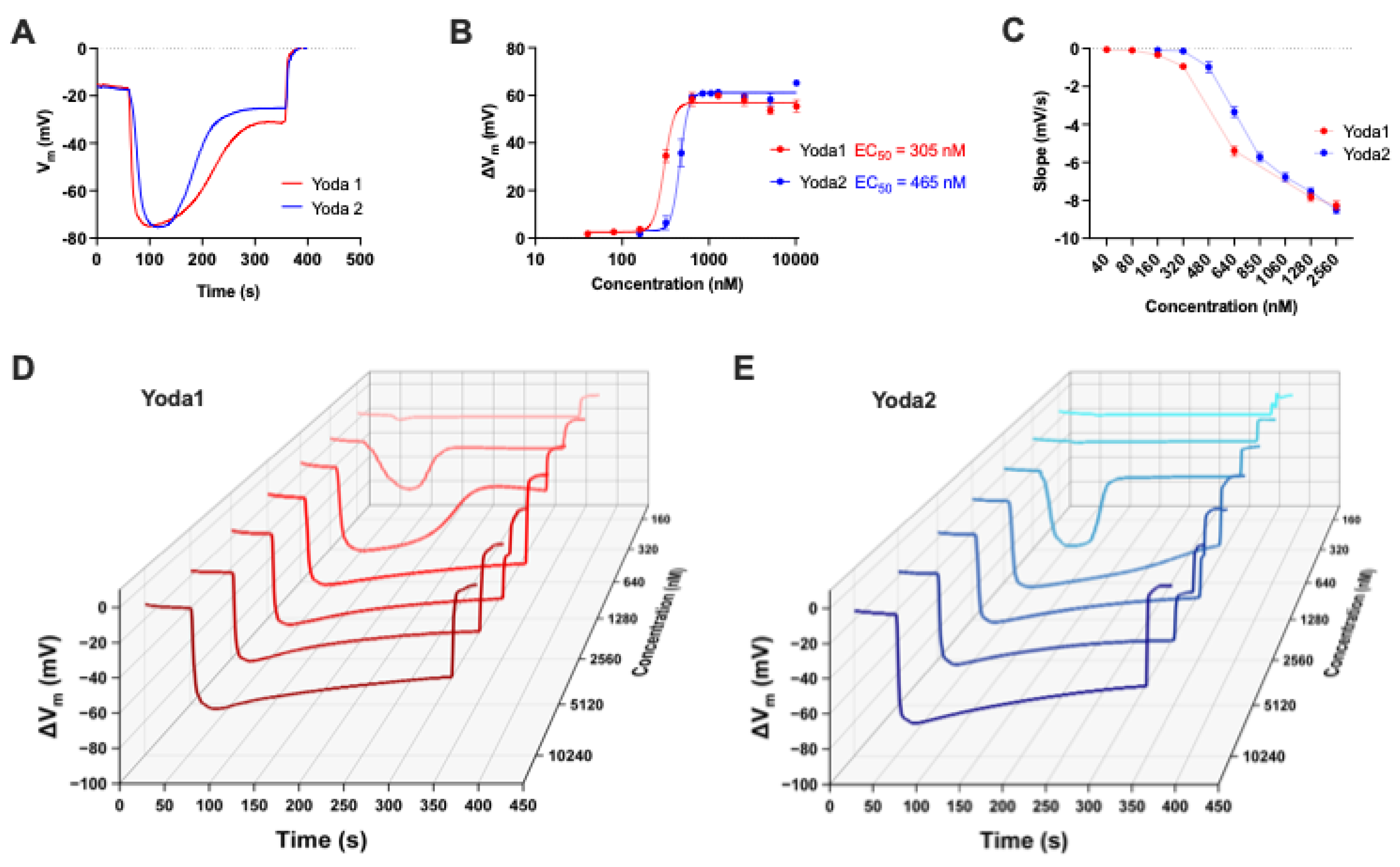

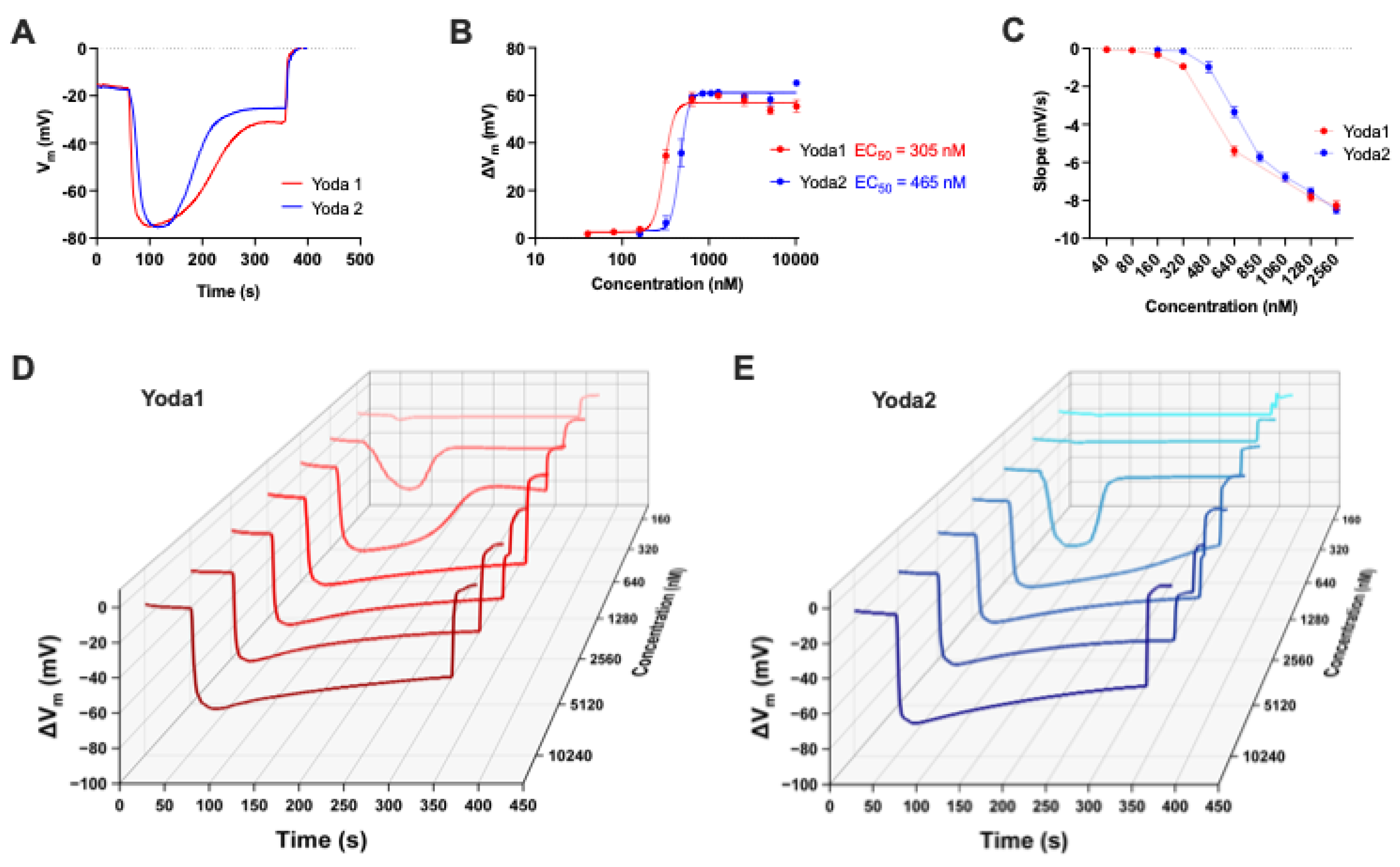

3.3. Membrane Potential Measurements

Membrane potential measurements revealed the effects of the Piezo1 activators Yoda1 and Yoda2 on RBCs. Each RBC sample has been exposed to decreasing concentrations of the activators, ranging from 10.24 µM to 160 nM, in order to assess the impact of the reagents and to determine key analytical parameters such as the EC₅₀. Representative recordings that illustrated changes in membrane potential are shown in

Figure 4A.

These traces indicated the timing of reagent addition, the magnitude of membrane depolarisation (defined as the difference between peak and resting membrane potentials), and the final addition of Triton X-100, which lysed the RBCs and established a reference condition corresponding to a membrane potential of 0 mV.

Figure 4B presents the dose–response curves for both Yoda1 and Yoda2, along with the calculated EC₅₀ values, which were 305 nM and 465 nM, respectively. The data indicated that while both compounds activated Piezo1 channels in RBCs at varying concentrations, there were notable differences in the cellular responses elicited by each. To quantify the rate of membrane hyperpolarisation, the slope of the membrane potential change was extrapolated from the dataset using MatLab and subsequently plotted for each concentration of Yoda1 and Yoda2, as shown in

Figure 4C. While Yoda1 and Yoda2 both followed a similar trend, the compounds exhibited a concentration-dependent increase in slope, indicating a higher rate of hyperpolarisation at higher concentrations.

Figure 4D displayed a waterfall plot of representative membrane potential traces across the concentration gradient for both activators. The traces highlighted a consistent pattern of faster hyperpolarisation at higher concentrations of the reagents, as well as a longer duration of effect.

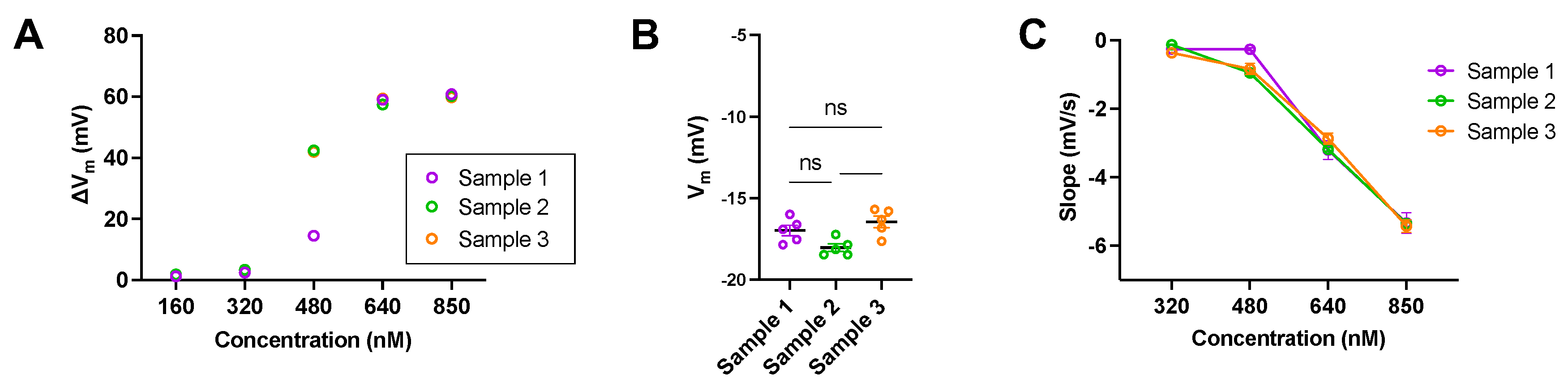

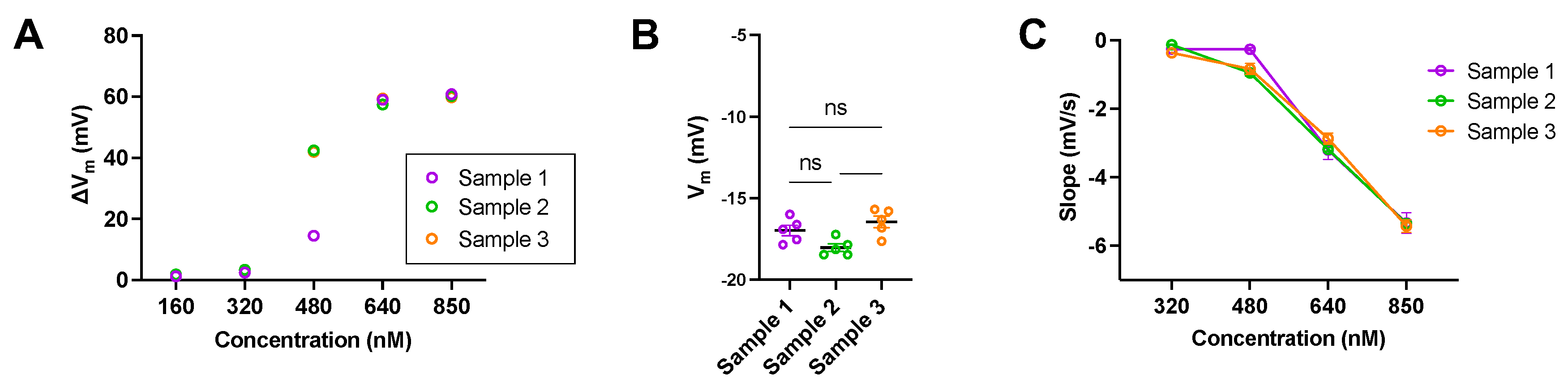

Figures 5A, 5B, and 5C aimed to determine whether biological variability was a factor to consider when analysing the data. The error bars in

Figures 4B and 4C, therefore, reflected biological variability due to donors rather than experimental error. This was particularly evident at intermediate concentrations such as 480 nM, where individual responses to the activators diverged significantly across donors.

4. Discussion

At first glance it looks easy and straightforward: An agonist or an activator of an ion channel increases its open probability in a dose-dependent manner in a particular environment/cell type at a given temperature. This means, when the whole-cell current is measured in dependence of the activator's concentration, a so-called dose-response curve is generated for Piezo1 in RBCs upon stimulation with Yoda1 and, alternately, with Yoda2 (

Figure 1). This gives characteristic EC

50 values of 880 nM and 319 nM for Yoda1 and Yoda 2, respectively.

However, the activity of Piezo1 in RBCs is mostly associated with a Ca

2+ influx. This is so predominant that it is sometimes overlooked that Piezo1 is a non-selective cation channel. The high Ca

2+ gradient of 20,000 between inside (60 nM) and outside (1.2 mM) the cell (under physiological conditions) and the high signaling capability of the Ca

2+ place this ion in the center of interest [

30]. Therefore, it makes a lot of sense to consider the dose of the Yoda compounds towards the magnitude of the Ca

2+ response in terms of fluorescence intensity of the Ca

2+ probe Fluo-4 (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). However, additional factors must now be considered:

- (i)

The Ca2+ entry, and hence the fluorescence of the dye accumulates over time, i.e., the kinetic properties of Piezo1 or more precisely the kinetic modulation of Piezo1 by the different Yoda variants come into play.

- (ii)

There are further players inside the RBC that influence the free Ca

2+ concentration (in a possibly Ca

2+ concentration-dependent manner), most notably the Ca

2+ pumps (mainly PMCA4) [

31].

Figure 2C-F shows that (depending on the Yoda concentrations) the RBC response increases over time reaching a maximum (which is in addition to the strength of the response, and also temporarily different for different Yoda concentrations) and finally declines over time. Therefore, the plot of the maximal response (which is at different time points after Yoda addition;

Figure 2C,D) has only limited value. Relating the patch clamp data to the Ca

2+ measurements, it seems obvious that Yoda1 results in a prolonged or sustained opening of Piezo1 in RBCs (EC

50 in similar order of magnitude for patch clamp and Ca

2+-measurements), while for the Yoda2 Ca

2+ response, the EC

50 is already 3 times the Yoda2 concentration from patch clamp recordings.

Going a step further, namely on the effect of increased intracellular Ca

2+ in RBCs: A main feature in the RBC volume regulation is the activation of the Gárdos channel and this volume regulation driven by the functional interaction between Piezo1 and Gárdos channel. This interaction is so far seen as the major physiological function triggered by Piezo1 [

7,

32,

33] and therefore, it is worthwhile to consider the Gárdos channel activity as one of the response parameters upon Yoda dose application. A very specific read-out parameter for Gárdos channel activity in RBCs is the hyperpolarisation of the RBC membrane potential [

27], and a very reliable method to measure the membrane potential in RBCs is the MBE method [

29]. The result of this approach is summarised in

Figure 4 and the response shows a (Yoda concentration-dependent) temporal modulation (Waterfall plots;

Figure 4C) showing yet a different dose-response curve (

Figure 4B) as the direct biophysical Yoda-dependent characterisation of Piezo1 (

Figure 1E) and the Piezo1 induced Ca

2+ entry (

Figure 2C). The activation of the Gárdos channel obviously requires submaximal Ca

2+ concentrations (referred to what can be reached by full Piezo1 activation) and therefore the EC

50 values of the MBE measurements are below the ones for the Ca

2+ influx.

Looking for the reasons, differences in the EC50 appear in the different measurement modes, we can identify several factors that can be grouped into three classes:

- (i)

Although all measurements relate to the activity of Piezo1, they are differently linked to the channel activity, as already discussed above. Patch clamp is the direct measurement, the Ca2+ increase is the response of the channel opening but modulated by other factors and the activity of the Gárdos channel is even further downstream with the potential of further modulations.

- (ii)

The nature of the measurements is vastly different. While patch clamp and Ca2+ measurements are single cell techniques, the MBE method is a cell population measurement presenting an average value of all cells, whereas in the patch clamp recordings non-responding cells are not considered. In the whole-cell configuration, the intracellular compartment is connected to a reservoir containing the internal solution, resulting in a wash-out of the cytosol. In contrast, Ca2+ and MBE measurements are performed on intact cells, just modulated by the abundance of Fluo-4 in the cytosol or CCCP in the cell membrane, respectively.

- (ii)

The concrete experimental conditions can be different. This is less about different personnel or laboratory locations, but rather to the fact that different methods require different conditions. This can be the composition of the ionic solutions, e.g., patch clamp recordings require a high fluoride concentration (110 mM) for an efficient seal formation or the nature of the MBE method requires a pH-unbuffered solution. Also, patch clamp recordings and Ca2+ measurements are performed at room temperature (due to historical reasons and technical limitations, respectively), whereas the MBE method needs to be performed at 37oC. Furthermore, for all three types of measurements, the effect of the Yoda compounds is convoluted with mechanical stress on the RBCs. All three major methods applied (patch-clamp technique, flow cytometry and MBE method) induce some but different mechanical stress to the RBCs (cell suction induced membrane curvature change, flow in tubes and chambers, stirring of cell suspension, respectively). Although this stress was present in the control condition (without Yoda stimulation), we cannot exclude a different effect of the mechanical stress on the Yoda-induced activity of Piezo1.

All three modes contribute to the different EC50’s but it would go far beyond the scope of this paper to decipher and quantify the particular contributions, still convoluted with the different kinetic action of Yoda1 and Yoda2. Our aim is rather to raise awareness of the underlying complexity.

5. Conclusions

The ‘real’ EC

50 (meaning the biophysical property) for Piezo1 activation in RBCs are the values given in the second column of

Table 1, with Yoda2 presenting a higher efficiency compared to Yoda1. However, looking for a cellular response, the picture changes and is even different in both numbers and relation of Yoda1 and Yoda2 to each other for the different read-outs. The reasons for these differences are multifactorial and discussed in more detail above.

As a recommendation for the choice of Yoda1 or Yoda2, all depends on the design of the experiments: When full activation of Piezo1 is required, where typically 3-times EC

50 concentrations are used, 3 µM of either Yoda1 or Yoda2 should be on the safe side. However, in their activation kinetics Yoda1 and Yoda2 show distinct differences (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 and

Appendix B). When Piezo1 stimulation around EC

50 is required, the recommendation is (even when performing similar experiments as presented here) to determine the EC

50 of the Yoda compound for the particular experimental settings and conditions (including the Yoda batch) as an experimental preparation to ensure correct concentrations, because the EC

50 values are highly sensitive on multiple parameters as discussed above.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G.R. and L.K.; formal analysis, M.Q., R.P., A.C. and F.M.M.; investigation, M.Q., R.P. and A.C.; resources, C.W. and L.K.; data curation, M.Q., R.P., A.C., N.M., M.G.R. and L.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Q., R.P., A.C., N.M. and L.K.; writing—review and editing, F.M.M., C.W. and M.G.R; visualization, M.Q., R.P., A.C. and L.K.; supervision, N.M., C.W., M.G.R. and L.K.; project administration, N.M., M.G.R. and L.K.; funding acquisition, M.G.R. and L.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work received funding from the European Community in Marie Skłodowska-Curie project no. 101120168—INNOVATION and from the German Research Foundation (DFG) in the Weave project GENIAL, project number 522062907.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the “Ärztekammer des Saarlandes” (51/18).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results. RP, NM and MGR are employees of Nanion Technologies, manufacturer of the device used for acquisition of the data presented in

Figure 1 and

Figure A1.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| a.u. |

arbitrary units |

| DMSO |

Di-Methyl-Sulf-Oxide |

| MBE |

Macey-Bennekou-Egée |

| ns |

not significant |

| RBCs |

red blood cells |

| RCF |

relative centrifugal force |

Appendix A

Additional Data Referring to the Patch Clam Pmeasurements

Figure A1.

The responding cells at + 80 mV of Piezo1 agonists Yoda1 and Yoda2 recorded using automated patch clamp. Yoda1: n = 13/159; N = 3; Yoda2: n = 12/158; N = 3. The bars are mean ± SEM, indicated in black, the circles are the data points from individual experiments. n represents the number of cells for a given experimental condition out of the total number of valid cells, and N indicates the number of independent experiments.

Figure A1.

The responding cells at + 80 mV of Piezo1 agonists Yoda1 and Yoda2 recorded using automated patch clamp. Yoda1: n = 13/159; N = 3; Yoda2: n = 12/158; N = 3. The bars are mean ± SEM, indicated in black, the circles are the data points from individual experiments. n represents the number of cells for a given experimental condition out of the total number of valid cells, and N indicates the number of independent experiments.

Appendix B

Additional Data Referring to Ca2+ Measurements

Figure A2.

Representative normalized histograms of Fluo-4 intensity of RBCs after Yoda1 stimulation over time. The concentration of Yoda1 is indicated in each panel.

Figure A2.

Representative normalized histograms of Fluo-4 intensity of RBCs after Yoda1 stimulation over time. The concentration of Yoda1 is indicated in each panel.

Figure A3.

Representative normalized histograms of Fluo-4 intensity of RBCs after Yoda2 stimulation over time. The concentration of Yoda2 is indicated in each panel.

Figure A3.

Representative normalized histograms of Fluo-4 intensity of RBCs after Yoda2 stimulation over time. The concentration of Yoda2 is indicated in each panel.

Figure A4.

Average Fluo-4 intensity of all red blood cells (RBCs) over time after (A) Yoda1 and (B) Yoda2 stimulation. Data are shown as means ± SEM. (N=3 independent experiments, n>30,000 cells per time interval).

Figure A4.

Average Fluo-4 intensity of all red blood cells (RBCs) over time after (A) Yoda1 and (B) Yoda2 stimulation. Data are shown as means ± SEM. (N=3 independent experiments, n>30,000 cells per time interval).

References

- Coste, B.; Mathur, J.; Schmidt, M.; Earley, T.J.; Ranade, S.; Petrus, M.J.; Dubin, A.E.; Patapoutian, A. Piezo1 and Piezo2 Are Essential Components of Distinct Mechanically Activated Cation Channels. Science 2010, 330, 55–60. [CrossRef]

- Coste, B.; Xiao, B.; Santos, J.S.; Syeda, R.; Grandl, J.; Spencer, K.S.; Kim, S.E.; Schmidt, M.; Mathur, J.; Dubin, A.E.; et al. Piezo Proteins Are Pore-Forming Subunits of Mechanically Activated Channels. Nature 2012, 483, 176–181. [CrossRef]

- Ranade, S.S.; Qiu, Z.; Woo, S.-H.; Hur, S.S.; Murthy, S.E.; Cahalan, S.M.; Xu, J.; Mathur, J.; Bandell, M.; Coste, B.; et al. Piezo1, a Mechanically Activated Ion Channel, Is Required for Vascular Development in Mice. Proc National Acad Sci 2014, 111, 10347–10352. [CrossRef]

- Gudipaty, S.A.; Lindblom, J.; Loftus, P.D.; Redd, M.J.; Edes, K.; Davey, C.F.; Krishnegowda, V.; Rosenblatt, J. Mechanical Stretch Triggers Rapid Epithelial Cell Division through Piezo1. Nature 2017, 543, 118–121. [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Si, G.; Huang, J.; Samuel, A.D.T.; Perrimon, N. Mechanical Regulation of Stem-Cell Differentiation by the Stretch-Activated Piezo Channel. Nature 2018, 555, 103–106. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Martinac, B. Mechanisms of PIEZO Channel Inactivation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14113. [CrossRef]

- Cahalan, S.M.; Lukacs, V.; Ranade, S.S.; Chien, S.; Bandell, M.; Patapoutian, A. Piezo1 Links Mechanical Forces to Red Blood Cell Volume. Elife 2015, 4. [CrossRef]

- Kuck, L.; Peart, J.N.; Simmonds, M.J. Piezo1 Regulates Shear-Dependent Nitric Oxide Production in Human Erythrocytes. Am. J. Physiol.-Hear. Circ. Physiol. 2022, 323, H24–H37. [CrossRef]

- Lew, V.L. The Calcium Homeostasis of Human Red Blood Cells in Health and Disease: Interactions of PIEZO1, the Plasma Membrane Calcium Pump, and Gardos Channels. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2025, 87, 257–277. [CrossRef]

- Zarychanski, R.; Schulz, V.P.; Houston, B.L.; Maksimova, Y.; Houston, D.S.; Smith, B.; Rinehart, J.; Gallagher, P.G. Mutations in the Mechanotransduction Protein PIEZO1 Are Associated with Hereditary Xerocytosis. Blood 2012, 120, 1908–1915. [CrossRef]

- Albuisson, J.; Murthy, S.E.; Bandell, M.; Coste, B.; Louis-dit-Picard, H. eacute l egrave ne; Mathur, J.; ant-Thibault, M.F. eacute n eacute; Tertian, G. eacute rard; Jaureguiberry, J.-P. de; Syfuss, P.-Y.; et al. Dehydrated Hereditary Stomatocytosis Linked to Gain-of-Function Mutations in Mechanically Activated PIEZO1 Ion Channels. Nature communications 2013, 4, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Rotordam, M.G.; Fermo, E.; Becker, N.; Barcellini, W.; Brüggemann, A.; Fertig, N.; Egée, S.; Rapedius, M.; Bianchi, P.; Kaestner, L. A Novel Gain-of-Function Mutation of Piezo1 Is Functionally Affirmed in Red Blood Cells by High-Throughput Patch Clamp. Haematologica 2019, 104, e179–e183. [CrossRef]

- Jankovsky, N.; Caulier, A.; Demagny, J.; Guitton, C.; Djordjevic, S.; Lebon, D.; Ouled-Haddou, H.; Picard, V.; Garçon, L. Recent Advances in the Pathophysiology of PIEZO1-related Hereditary Xerocytosis. Am. J. Hematol. 2021, 96, 1017–1026. [CrossRef]

- Dryllis, G.; Russo, R.; Andolfo, I.; Iolascon, A.; Rosato, B.E.; Konstantopoulos, K. Hereditary Hemolytic Anemia Due to PIEZO1 Red Blood Cell Membrane Defect. Hemoglobin 2024, 48, 357–359. [CrossRef]

- Cox, C.D.; Bae, C.; Ziegler, L.; Hartley, S.; Nikolova-Krstevski, V.; Rohde, P.R.; Ng, C.-A.; Sachs, F.; Gottlieb, P.A.; Martinac, B. Removal of the Mechanoprotective Influence of the Cytoskeleton Reveals PIEZO1 Is Gated by Bilayer Tension. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10366. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.H.; Grandl, J. Mechanical Sensitivity of Piezo1 Ion Channels Can Be Tuned by Cellular Membrane Tension. eLife 2015, 4, e12088. [CrossRef]

- Ridone, P.; Pandzic, E.; Vassalli, M.; Cox, C.D.; Macmillan, A.; Gottlieb, P.A.; Martinac, B. Disruption of Membrane Cholesterol Organization Impairs the Activity of PIEZO1 Channel Clusters. J. Gen. Physiol. 2020, 152, e201912515. [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Allegrini, B.; Rapetti-Mauss, R.; Picard, V.; Garçon, L.; Kohl, P.; Soriani, O.; Peyronnet, R.; Guizouarn, H. Hereditary Xerocytosis: Differential Behavior of PIEZO1 Mutations in the N-Terminal Extracellular Domain Between Red Blood Cells and HEK Cells. Front Physiol 2021, 12, 736585. [CrossRef]

- Caulier, A.; Garçon, L. PIEZO1, Sensing the Touch during Erythropoiesis. Curr Opin Hematol 2022, 29, 112–118. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, L.R. Regulation of PIEZO Channels by Membrane Lipids. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Syeda, R.; Xu, J.; Dubin, A.E.; Coste, B.; Mathur, J.; Huynh, T.; Matzen, J.; Lao, J.; Tully, D.C.; Engels, I.H.; et al. Chemical Activation of the Mechanotransduction Channel Piezo1. Elife 2015, 4, e07369. [CrossRef]

- Botello-Smith, W.M.; Zhang, H.; Ozkan, A.D.; Jiang, W.; Pham, C.N.; Luo, Y.; Lacroix, J.J. Structural Bases for Chemical and Mechanical Gating in the Piezo1 Channel. Biophys. J. 2019, 116, 478a–479a. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Miao, X.; Arnold, S.; Li, B.; Ly, A.T.; Wang, H.; Wang, M.; Guo, X.; Pathak, M.M.; Zhao, W.; et al. Membrane Curvature Governs the Distribution of Piezo1 in Live Cells. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7467. [CrossRef]

- Petkova-Kirova, P.; Murciano, N.; Iacono, G.; Jansen, J.; Simionato, G.; Qiao, M.; Zwaan, C.V. der; Rotordam, M.G.; John, T.; Hertz, L.; et al. The Gárdos Channel and Piezo1 Revisited: Comparison between Reticulocytes and Mature Red Blood Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1416. [CrossRef]

- Hatem, A.; Esperti, S.; Murciano, N.; Qiao, M.; Rotordam, M.G.; Becker, N.; Nader, E.; Maurer, F.; Pérès, L.; Bouyer, G.; et al. Adverse Effects of Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol on Sickle Red Blood Cells. Am. J. Hematol. 2023, 98, E383–E386. [CrossRef]

- Macey, R.I.; Adorante, J.S.; Orme, F.W. Erythrocyte Membrane Potentials Determined by Hydrogen Ion Distribution. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta Bba - Biomembr 1978, 512, 284–295. [CrossRef]

- Baunbaek, M.; Bennekou, P. Evidence for a Random Entry of Ca2+ into Human Red Cells. Bioelectrochemistry 2008, 73, 145–150. [CrossRef]

- Alonso, D.M.; Pérès, L.; Hatem, A.; Bouyer, G.; Egée, S. The Chloride Conductance Inhibitor NS3623 Enhances the Activity of a Non-Selective Cation Channel in Hyperpolarizing Conditions. Front Physiol 2021, 12, 743094. [CrossRef]

- Jansen, J.; Qiao, M.; Hertz, L.; Wang, X.; Fermo, E.; Zaninoni, A.; Colombatti, R.; Bernhardt, I.; Bianchi, P.; Kaestner, L. Mechanistic Ion Channel Interactions in Red Cells of Patients with Gárdos Channelopathy. Blood Adv 2021, 5, 3303–3308. [CrossRef]

- Bogdanova, A.; Makhro, A.; Wang, J.; Lipp, P.; Kaestner, L. Calcium in Red Blood Cells-a Perilous Balance. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2013, 14, 9848–9872. [CrossRef]

- Kaestner, L.; Bogdanova, A.; Egee, S. Calcium Channels and Calcium-Regulated Channels in Human Red Blood Cells. Adv Exp Med Biol 2020, 1131, 625–648. [CrossRef]

- Faucherre, A.; Kissa, K.; Nargeot, J.; Mangoni, M.E.; Jopling, C. Piezo1 Plays a Role in Erythrocyte Volume Homeostasis. Haematologica 2013, 99, 70–75. [CrossRef]

- Danielczok, J.G.; Terriac, E.; Hertz, L.; Petkova-Kirova, P.; Lautenschläger, F.; Laschke, M.W.; Kaestner, L. Red Blood Cell Passage of Small Capillaries Is Associated with Transient Ca2+-Mediated Adaptations. Front Physiol 2017, 8, 979. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Comparative analysis of Piezo1 activators Yoda1 and Yoda2 using automated patch clamp. (A-B) Representative current ramp traces recorded from human RBCs. Voltage ramps from -100 mV to +80 mV (insets) were applied every 10 seconds. Cells were initially perfused with external solution (grey traces), followed by cumulative additions of Yoda1 (A; 41 nM, 144 nM, 442 nM, 1.33 µM, 4 µM, and 8 µM; red traces) or Yoda2 (B; 41 nM, 144 nM, 442 nM, 1.33 µM, 4 µM, and 8 µM; blue traces). Subsequently, 30 μM GdCl₃ was applied to block Piezo1 channels (black traces). (C-D) Time-course plots of current amplitudes at +80 mV from representative cells exposed to cumulative applications of external solution (C-D, grey traces), increasing solutions of Yoda1 (C, red traces) or Yoda2 (D, blue traces), and GdCl₃ (C-D, black traces). Dashed vertical lines indicate the time points of each solution addition. (E) Concentration-response curves for Yoda1 and Yoda2. Current amplitudes at +80 mV were normalized to the baseline current in the external solution (I/IREF). Data points represent mean ± SEM. Curves were fitted using the Hill equation to estimate the EC₅₀s. The EC₅₀ values were determined to be 880 nM for Yoda1 (n = 13/159; N = 3) and 319 nM for Yoda2 (n = 12/158; N = 3), indicating a higher potency and efficiency of Yoda2 in activating Piezo1 channel. Here, n represents the number of responding cells out of the total number of cells that met the preset quality control conditions, and N indicates the number of independent NPC-384 well plates.

Figure 1.

Comparative analysis of Piezo1 activators Yoda1 and Yoda2 using automated patch clamp. (A-B) Representative current ramp traces recorded from human RBCs. Voltage ramps from -100 mV to +80 mV (insets) were applied every 10 seconds. Cells were initially perfused with external solution (grey traces), followed by cumulative additions of Yoda1 (A; 41 nM, 144 nM, 442 nM, 1.33 µM, 4 µM, and 8 µM; red traces) or Yoda2 (B; 41 nM, 144 nM, 442 nM, 1.33 µM, 4 µM, and 8 µM; blue traces). Subsequently, 30 μM GdCl₃ was applied to block Piezo1 channels (black traces). (C-D) Time-course plots of current amplitudes at +80 mV from representative cells exposed to cumulative applications of external solution (C-D, grey traces), increasing solutions of Yoda1 (C, red traces) or Yoda2 (D, blue traces), and GdCl₃ (C-D, black traces). Dashed vertical lines indicate the time points of each solution addition. (E) Concentration-response curves for Yoda1 and Yoda2. Current amplitudes at +80 mV were normalized to the baseline current in the external solution (I/IREF). Data points represent mean ± SEM. Curves were fitted using the Hill equation to estimate the EC₅₀s. The EC₅₀ values were determined to be 880 nM for Yoda1 (n = 13/159; N = 3) and 319 nM for Yoda2 (n = 12/158; N = 3), indicating a higher potency and efficiency of Yoda2 in activating Piezo1 channel. Here, n represents the number of responding cells out of the total number of cells that met the preset quality control conditions, and N indicates the number of independent NPC-384 well plates.

Figure 2.

Comparison of action of Yoda1 and Yoda2 on the free Ca

2+ in healthy red blood cells (RBCs). (A) Representative normalized histograms of Fluo-4 intensity of unstained RBCs (gray), Fluo-4 stained RBCs in Tyrode solution (black), Fluo-4 stained RBCs with Yoda1 stimulation (red) and Fluo-4 stained RBCs with Yoda2 stimulation (blue). (B) Maximum Fluo-4 intensity during recording for each compound were used to construct fitted curves from the Hill equation, and the respective EC

50 values are indicated. (C,D) Representative normalized histograms of Fluo-4 intensity of RBCs after 5.12 μM Yoda1 (C) and Yoda2 (D) stimulation. Histograms for all concentrationa applied are provided in

Appendix B. (E,F) 3D presentation of fitted curves from the Hill equation by using the average Fluo-4 intensity of RBCs after Yoda1 (E) and Yoda2 (F) stimulation over time. (G,H) Percentage of the high Ca

2+ RBCs population over time after Yoda1 (G) and Yoda2 (H) stimulation. Data are shown as means ± SEM in panels (B), (G) and (H). (N=3 independent experiments with at least 30,000 cells per time interval).

Figure 2.

Comparison of action of Yoda1 and Yoda2 on the free Ca

2+ in healthy red blood cells (RBCs). (A) Representative normalized histograms of Fluo-4 intensity of unstained RBCs (gray), Fluo-4 stained RBCs in Tyrode solution (black), Fluo-4 stained RBCs with Yoda1 stimulation (red) and Fluo-4 stained RBCs with Yoda2 stimulation (blue). (B) Maximum Fluo-4 intensity during recording for each compound were used to construct fitted curves from the Hill equation, and the respective EC

50 values are indicated. (C,D) Representative normalized histograms of Fluo-4 intensity of RBCs after 5.12 μM Yoda1 (C) and Yoda2 (D) stimulation. Histograms for all concentrationa applied are provided in

Appendix B. (E,F) 3D presentation of fitted curves from the Hill equation by using the average Fluo-4 intensity of RBCs after Yoda1 (E) and Yoda2 (F) stimulation over time. (G,H) Percentage of the high Ca

2+ RBCs population over time after Yoda1 (G) and Yoda2 (H) stimulation. Data are shown as means ± SEM in panels (B), (G) and (H). (N=3 independent experiments with at least 30,000 cells per time interval).

Figure 3.

Exemplified microscopy analysis of Ca2+-signaling of healthy red blood cells (RBCs) with 1.28 μM Yoda1 or Yoda2 stimulation. (A) The cellular Ca2+-response was plotted as average Fluo-4 intensity over time for all RBCs (N=2 independent experiments, each of n>50 cells). (B) - (E) Confocal images of RBCs at different conditions: (B) unstained RBCs; (C) Fluo-4 stained RBCs in Tyrode solution, the inset is intensity ampliefied to visualize the cells; (D) Fluo-4 stained RBCs after Yoda1 stimulation with temporal information indicated below the images; (E) Fluo-4 stained RBCs after Yoda2 stimulation with temporal information indicated below the images. The scale bar given in (B) is valid for all images and all images had the same acquisition settings and are displayed in the same contrast settings, except the insert in panel (C).

Figure 3.

Exemplified microscopy analysis of Ca2+-signaling of healthy red blood cells (RBCs) with 1.28 μM Yoda1 or Yoda2 stimulation. (A) The cellular Ca2+-response was plotted as average Fluo-4 intensity over time for all RBCs (N=2 independent experiments, each of n>50 cells). (B) - (E) Confocal images of RBCs at different conditions: (B) unstained RBCs; (C) Fluo-4 stained RBCs in Tyrode solution, the inset is intensity ampliefied to visualize the cells; (D) Fluo-4 stained RBCs after Yoda1 stimulation with temporal information indicated below the images; (E) Fluo-4 stained RBCs after Yoda2 stimulation with temporal information indicated below the images. The scale bar given in (B) is valid for all images and all images had the same acquisition settings and are displayed in the same contrast settings, except the insert in panel (C).

Figure 4.

The comparison of Piezo1 activators Yoda1 and Yoda2 in a population of healthy red blood cells (RBCs) using the MBE method. (A) Representative recordings of membrane potential (Vm) changes in RBCs upon exposure to 640 nM Yoda1 (red) and Yoda2 (blue). Recording starts at the resting membrane potential (Vrest) of RBCs. The trace shows the addition of the reagent – Yoda1 or Yoda2 – as well as the addition of Triton-X at the end so as to lyse the cells (reference point 0 mV). (B) Dose-response curves for Yoda1 and Yoda2, showing the effect of varying concentrations of the reagents. For each concentration, ΔVd is obtained from the averaging of two or more measurements from different donors. The Hill equation is used to fit curves to the data. The respective EC50 values for Yoda1 and Yoda2 are indicated on the plot. (C) Representation of the dose dependency of the slope in RBC samples after the addition of reagents. The slope is determined by identifying the membrane potential values at one-third and two-thirds of the range between the resting membrane potential and the peak membrane potential. Specifically, the slope is calculated as (Vb−Va)/(Tb−Ta), where Va and Vb are the membrane potentials at one-third and two-thirds of the range, respectively, and Ta and Tb are the corresponding time points. This reflects the rate of hyperpolarization within the central portion of the response curve. (D,E) 3D waterfall plot displaying representative traces of membrane potential changes in RBCs following exposure to varying concentrations of Yoda1 and Yoda2. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Figure 4.

The comparison of Piezo1 activators Yoda1 and Yoda2 in a population of healthy red blood cells (RBCs) using the MBE method. (A) Representative recordings of membrane potential (Vm) changes in RBCs upon exposure to 640 nM Yoda1 (red) and Yoda2 (blue). Recording starts at the resting membrane potential (Vrest) of RBCs. The trace shows the addition of the reagent – Yoda1 or Yoda2 – as well as the addition of Triton-X at the end so as to lyse the cells (reference point 0 mV). (B) Dose-response curves for Yoda1 and Yoda2, showing the effect of varying concentrations of the reagents. For each concentration, ΔVd is obtained from the averaging of two or more measurements from different donors. The Hill equation is used to fit curves to the data. The respective EC50 values for Yoda1 and Yoda2 are indicated on the plot. (C) Representation of the dose dependency of the slope in RBC samples after the addition of reagents. The slope is determined by identifying the membrane potential values at one-third and two-thirds of the range between the resting membrane potential and the peak membrane potential. Specifically, the slope is calculated as (Vb−Va)/(Tb−Ta), where Va and Vb are the membrane potentials at one-third and two-thirds of the range, respectively, and Ta and Tb are the corresponding time points. This reflects the rate of hyperpolarization within the central portion of the response curve. (D,E) 3D waterfall plot displaying representative traces of membrane potential changes in RBCs following exposure to varying concentrations of Yoda1 and Yoda2. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Figure 5.

(A-C) Graphs representing the biological variability of samples as a means to determine that variation of results during experiments is sample dependent and not mechanical error. Samples from three donors were measured under identical conditions to ensure consistency in the results. (A) Bar graph showing ΔVm of red blood cells (RBCs) exposed to five different concentrations of Yoda2. (B) Bar graph comparing the Vrest of three different donors. (C) Representation of the dose dependency of the slope in RBC samples after addition of decreasing concentrations of Yoda1 and Yoda2. Statistical significance in the graphs was determined using ordinary one-way ANOVA. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Significant differences between groups were considered at p < 0.05. All experiments were conducted under identical conditions and on the same day in order to ensure that observed variability arose solely from biological differences between samples rather than external or mechanical inconsistencies.

Figure 5.

(A-C) Graphs representing the biological variability of samples as a means to determine that variation of results during experiments is sample dependent and not mechanical error. Samples from three donors were measured under identical conditions to ensure consistency in the results. (A) Bar graph showing ΔVm of red blood cells (RBCs) exposed to five different concentrations of Yoda2. (B) Bar graph comparing the Vrest of three different donors. (C) Representation of the dose dependency of the slope in RBC samples after addition of decreasing concentrations of Yoda1 and Yoda2. Statistical significance in the graphs was determined using ordinary one-way ANOVA. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Significant differences between groups were considered at p < 0.05. All experiments were conducted under identical conditions and on the same day in order to ensure that observed variability arose solely from biological differences between samples rather than external or mechanical inconsistencies.

Table 1.

Summary of the EC50 data for Yoda1 and Yoda2 for all read-out methods applied.

Table 1.

Summary of the EC50 data for Yoda1 and Yoda2 for all read-out methods applied.

| compound |

EC50 (patch clamp) [nM] |

EC50 (Ca2+ measurements) [nM] |

EC50 (membrane potential) [nM] |

| Yoda1 |

880 |

1181 |

305 |

| Yoda2 |

319 |

986 |

465 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).