1. Introduction

Adverse drug events (ADEs) are a significant cause of prolonged hospitalization, morbidity, and mortality, posing a direct threat to patient safety [

1]. Although pre-market clinical trials rigorously assess the safety of new drugs, rare and serious ADEs often emerge only in real-world clinical settings [

2]. As such, robust pharmacovigilance systems are essential for the ongoing monitoring of drug safety post-approval [

1].

To coordinate global efforts in pharmacovigilance, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched the Programme for International Drug Monitoring (PIDM) in 1968 [

3]. As of today, over 180 countries participate in this program, contributing more than 40 million individual case safety reports to VigiBase, the world’s largest pharmacovigilance database [

3]. This collaborative data-sharing enables timely signal detection, facilitating early regulatory action to mitigate harm and enhance patient protection [

1,

2].

A cornerstone of pharmacovigilance is the spontaneous reporting system (SRS), wherein healthcare professionals and patients voluntarily report suspected ADEs [

1]. Despite its critical role, the effectiveness of SRS is undermined by widespread underreporting, largely due to a lack of awareness, training, and institutional support [

4,

5,

6]. Globally, it is estimated that only around 6% of actual ADEs are reported [

6], delaying risk identification and compromising patient safety [

7]. Addressing the barriers to reporting is thus imperative for cultivating a proactive safety culture in healthcare [

8].

Recognizing the increasing use of herbal medicines (HMs) worldwide, the WHO has emphasized the urgent need to integrate HMs into national pharmacovigilance frameworks [

9]. Although HMs have a long tradition of use, many lack rigorous post-marketing safety evaluations [

10]. Consequently, post-market surveillance is essential for ensuring the safe and responsible use of HMs [

11]. However, many countries either exclude HMs from their SRS entirely or include only a limited subset [

12]. Furthermore, underreporting of HM-related ADEs is particularly prevalent due to low perceived risk, lack of standardization, and patients’ reluctance to disclose HM use to healthcare providers [

10,

11,

12,

13].

In Korea, traditional East Asian medicine is widely practiced, and herbal medicines are central to Korean medicine. These are dispensed in a variety of forms, ranging from licensed herbal medicinal products (HMPs) manufactured by pharmaceutical companies to self-prepared herbal medicines (SPHMs) such as decoctions and powders, produced by traditional Korean medicine institutions (KMIs). Despite their prevalence, only a limited number of these—mainly licensed HMPs and select herbal raw materials (HRMs)—are included in the national SRS.

The Korean SRS was established in 1988, and regional drug safety centers (RDSCs) have promoted reporting since 2006 [

14]. Although most RDSCs are housed within Western medical institutions or the Korean Pharmaceutical Association, a Korean medicine institution was designated as an RDSC specializing in herbal medicines for the first time in 2020 [

14]. However, the current SRS continues to exclude many commonly used SPHMs, thereby limiting comprehensive safety surveillance in Korean medicine [

12]. As a result, ADE reporting by traditional Korean medicine doctors (KMDs) remains very low, and HM-related safety data are scarce [

15].

Healthcare professionals’ engagement in pharmacovigilance is closely linked to their knowledge, attitudes, and exposure to training [

7,

8]. Although a 2007 study explored general stakeholder views on HMs and ADEs [

16], no research to date has specifically examined the perspectives and practices of KMDs. Given their central role in prescribing HMs, understanding the barriers they face is essential to strengthening patient safety within the domain of Korean medicine.

This study aimed to assess the knowledge, attitudes, and experiences of KMDs regarding spontaneous ADE reporting. The findings are expected to inform targeted strategies for enhancing KMD participation in pharmacovigilance and support the development of a more inclusive and effective safety monitoring system—ultimately contributing to a stronger culture of patient safety in contemporary integrative healthcare.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

This was a cross-sectional study employing an anonymous online survey. The study population comprised KMD members of the Association of Korean Medical who agreed to participate in this survey, completed the response, and were currently engaged in clinical practice or medical education/research (academia). A KMD was defined as a person who completed and graduated from a six-year course at a college of traditional Korean medicine (KM) or a four-year course at a graduate school of KM approved by the government of the Republic of Korea, passed a national examination for KMDs, and obtained a license from the Ministry of Health and Welfare, thereby obtaining a legal license to practice KM practices.

2.2. Questionnaire Development

The questionnaire was designed based on previous studies [

7,

8,

16]. The questionnaire consisted of four sections: the respondents’ sociodemographic characteristics, knowledge, attitudes, and experience regarding spontaneous reporting (SR) of ADEs. Sociodemographic variables were collected from six questions on sex, age group (20s, 30s, 40s, 50s, and over 60 years), years of experience as a KMD (<5, 5–9, 10–19, and ≥ 20 years), current employment type (self-employed, employed, and academia), current workplace (local clinic, other medical institutions, and university/research institutions), and experience completing a training course in KM teaching hospitals (never, internship, and residency training). Four questions on knowledge level (K1–4), six questions on attitudes (A1–6), and four questions on experience with SR and related education (E1–4) were assigned.

2.3. Data Collection

The self-developed questionnaire was entered into the online platform provided by the Korean Social Science Data Center (KSDC), and the link address was sent to 27,407 email accounts registered as KMD members of the association of Korean Medicine as of October 21, 2024. The purpose, outline, and utilization plan of the survey were provided via email, and data were collected only from members who voluntarily agreed to participate. The survey period was 12 days, from October 21 to November 1, 2024. After completing the survey, raw data in Microsoft Excel file format were downloaded from the KSDC.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics of the responses to each item are presented as frequencies and percentages. For questions allowing multiple responses, the frequency and percentage were calculated based on the number of participants who responded. For the questionnaire related to knowledge, attitudes, and experience, odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using logistic regression analysis to evaluate the influence of respondents’ sociodemographic characteristics on each response. The results of the univariate and multivariate analyses adjusted for sex, age group, clinical experience, employment type, workplace, and training experience are presented. In cases where the independent variables were categorical (age group, clinical experience, and training experience), a trend analysis was performed to determine whether the dependent variable exhibited a linear trend as each category level increased. For two identical questions with multiple answers, the consistency of the response rate for each choice was estimated using the chi-square test. All results were analyzed using R statistical software (version 4.1.1; R Core Team 2021), with statistical significance set at p-values of < 0.05.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

Before conducting the survey, the research procedure and result utilization plan were submitted to the Institutional Review Board, and an exemption from review was received (DUIOH IRB 2024-07-001-001). Written informed consent was not obtained to ensure the anonymity of the respondents.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Respondents

Data from 1,021 respondents who met the inclusion criteria among the 1,040 who completed the questionnaire were analyzed. The respondents’ sociodemographic characteristics are presented in

Table 1. Males accounted for 65.4% of cases. The most common age group was the 30s, followed by the 40s. The clinical experience was 10–19 years for the most part (33.6%). The employment type was mostly self-employed (45.4%), followed by the employed (42.9%). The most common workplace was a local KM clinic (62.9%), followed by other medical institutions (35.3%). More than half of the respondents (60.5%) were general practitioners with no training experience in KM teaching hospitals. Respondents who completed a one-year internship was 12.3%, and specialists who completed a one-year internship and a three-year residency training was 27.1%.

3.2. Knowledge Characteristics

Four questions (K1–4) were assigned to assess the respondents’ knowledge level (

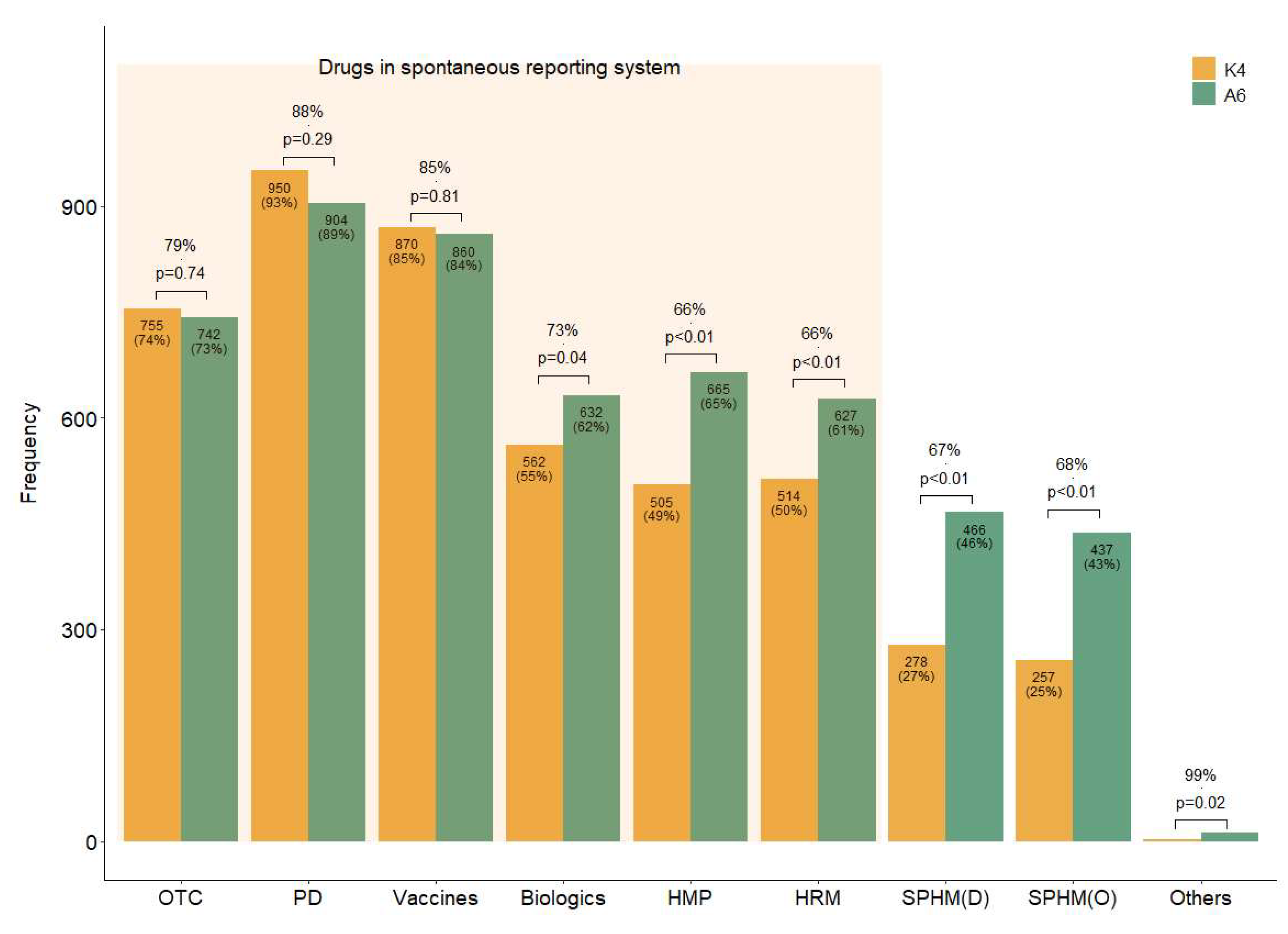

Table 2). Overall, 55% of the respondents were aware of the domestic SRS (K1), whereas 46% were aware that HMs were also included in the system (K2). Additionally, 59% of the respondents answered that they should report to the regulatory agency even if the causal relationship between drugs and ADEs was unclear (K3), suggesting that they were clearly aware of the subjects of SR. As illustrated by the K4 bar plot in

Figure 1, more than half of the respondents were aware of the drugs in the current SRS (over-the-counter drugs, prescription drugs, vaccines, biologics, licensed HMPs, and HRM) (

Figure 1 (K4)). However, fewer respondents were aware that some HMs (licensed HMPs, 49%; HRM, 50%) were included in the SRS compared with Western medicines (from 55% to 93%) (

Figure 1 (K4)).

3.3. Attitude Characteristics

Six questions (A1–6) were assigned to assess the respondents’ attitudes toward SRS (

Table 2). Almost 90% of the respondents agreed that KMDs need to actively report ADEs (A1) and that their role in SRS is important (A2), showing a positive attitude toward KMD participation in SR (

Table 2).

As shown in

Table 3, the most agreed-upon potential outcome of SR (A3) was knowledge accumulation regarding the safe use of drugs, and all three of the top three most frequently reported outcomes were positive. Among negative expectations, concerns about legal disputes and heightened social tensions were the most frequently selected.

The most common reasons for non-participation in SR (A4) were a lack of awareness of SRS and reporting procedures, followed by the belief that cases with low causality and mild severity of AEs did not need to be reported (

Table 4).

The most common measure for activating SR (A5) was the simplification of the reporting process, followed by strengthening undergraduate education on related tasks and establishing institutional devices to resolve legal disputes (

Table 5).

In terms of the types of drugs that should be included in the domestic SRS (A6), respondents answered that in addition to the drugs already managed within the current system, all types of HMs, including SPHMs, which are prepared in KMIs and not in pharmaceuticals, should also be included in the system (

Figure 1 (A6)). In questions with the same choices (K4 and A6), the agreement in the response rates for each choice was generally high; however, in the case of HMs and biologics, the demand for management necessity (A6) was significantly higher than the awareness of the current status of inclusion within the system (K4) (

Figure 1).

3.4. Experience Characteristics

Four questions (E1–4) were assigned to investigate the respondents’ experiences of SR and related education (

Table 2). Half of the respondents (51%) answered that they had experienced or witnessed ADEs, but only 5% reported these to a regulatory agency. Most respondents (91%) answered that they had not received any training in pharmacovigilance, including SR procedures or causality assessments. Those with educational experience indicated that they had received education through an undergraduate curriculum, training courses in teaching hospitals, or continuing education.

3.5. Sociodemographic Factors Affecting Respondents’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Experiences Regarding SR

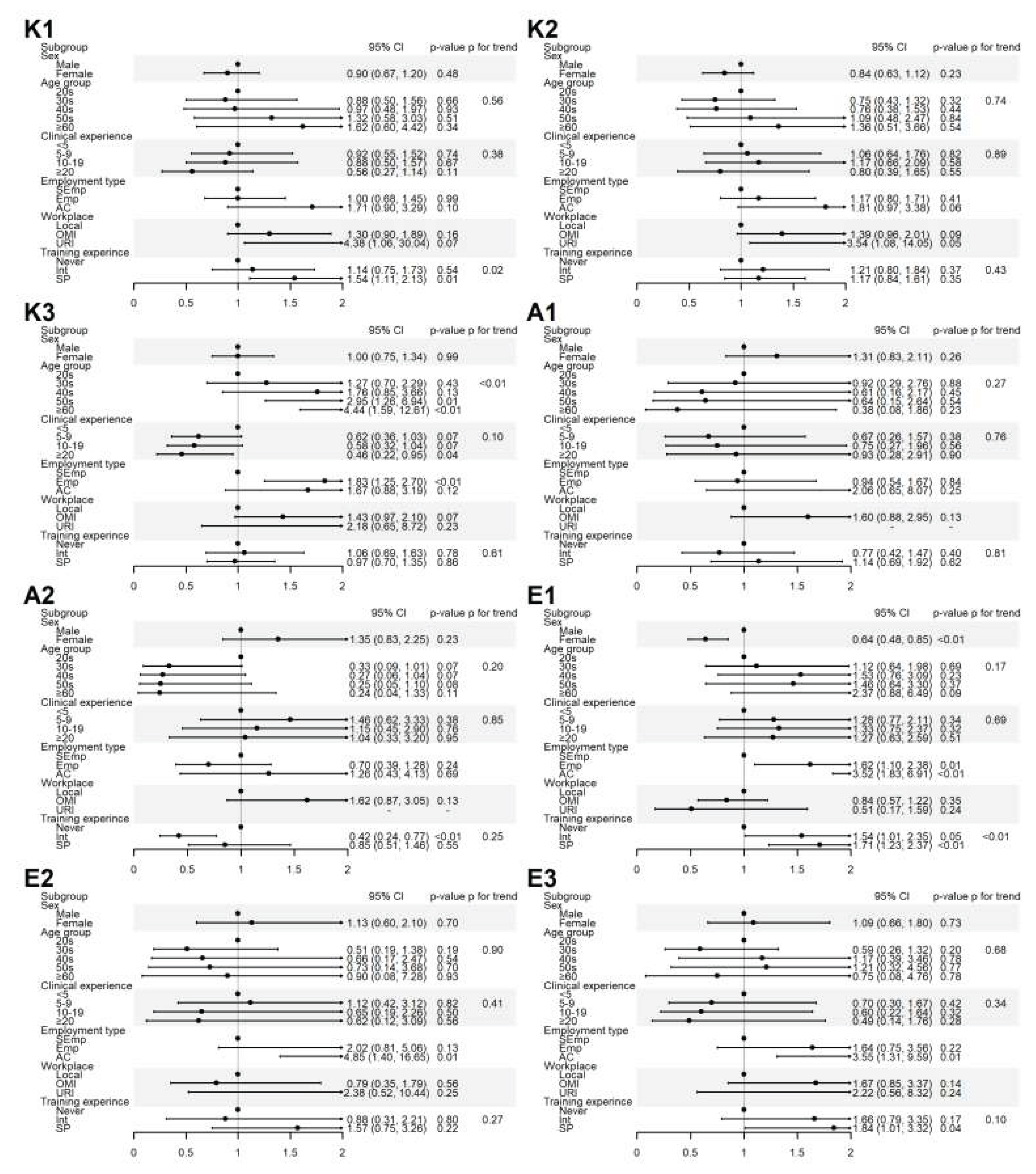

The impact of the respondents’ sociodemographic variables on yes-or-no questions was assessed. The adjusted OR with 95% CI derived from the multivariable logistic regression analysis and p-values for trend derived from the trend analysis for categorical variables are presented in

Figure 2 and

Supplementary Table S1.

The level of awareness of domestic SRS (K1) differed according to employment type, workplace, and training experience in the univariate analysis. However, multivariable analysis showed that the likelihood of being aware of the system was significantly higher in those working in the academia compared with self-employed respondents (OR 1.71, 95% CI 0.90–3.29) and in specialists compared with general practitioners (OR 1.54, 95% CI 1.11–2.13). In particular, there was a tendency for SRS awareness to increase as training experience increased (p for trend = 0.02).

In the univariate analysis, the level of awareness that HMs are included in the domestic SRS (K2) differed according to employment type, workplace, and training experience. However, the fully adjusted analysis confirmed that no factor had a significant effect on the answers.

The level of awareness that ADEs should be reported to regulatory agencies, even when causality is unclear (K3), differed by clinical experience, employment type, and workplace in the univariable analysis. However, the multivariate analysis revealed age group, clinical experience, employment type, and workplace in the unadjusted analysis. Adjusted analysis revealed that age group, clinical experience, and employment type had significant effects. Compared to those in their 20s, those in their 50s and older had a higher rate of agreement to report cases where causality was unclear (OR 2.95, 95% CI 1.26–6.94 for those in their 50’s; OR 4.44, 95% CI 1.59–12.61, for those in their 60s and older), and there was a tendency for agreement to increase with age (p for trend < 0.01). The consent rate for reporting was higher in the employed KMDs than in the self-employed (OR 1.83, 95% CI 1.25–2.70). However, compared to respondents with less than 5 years of clinical experience, those with 20 years or more were less likely to agree (OR 0.46, 95% CI 0.22–0.95), and this tendency was stronger as clinical experience increased (p for trend = 0.10).

The agreement rate on the need for active KMD participation in SR (A1) and the importance of the role of KMDs in this system (A2) differed by age group, clinical experience, employment type, and workplace in univariate analysis. In the adjusted model analysis, 100% of the respondents in the group whose workplace was a university or research institute agreed with these two questions. For the first question (A1), no factor other than workplace had a significant effect on the answer. On the other hand, in the latter case (A2), the respondents who completed only a one-year internship training course had a significantly lower rate of agreement than the general practitioners (OR 0.42, 95% CI 0.24–0.77).

The proportion of respondents who answered that they had experienced and/or witnessed ADEs (E1) appeared to be affected by all sociodemographic variables in the univariate analysis. However, in the multivariate analysis, only sex, employment type, and training experience showed a significant impact. Compared with the self-employed respondents, employed respondents (OR 1.62, 95% CI 1.10–2.38) and those in the academia (OR 3.52, 95% CI 1.83–6.91) were more likely to answer that they had experience. Compared with general KMDs who had no training experience, the specialists had a higher rate of agreement with this answer (OR 1.71, 95% CI 1.23–2.37), and this tendency became stronger as training experience increased (p for trend < 0.01). Women were less likely to agree with this question than men (OR 0.64, 95% CI 0.48–0.85).

Only the employment type had a significant impact on SR experience. Compared with self-employed respondents, the academia group had significantly higher experience in SR (OR 4.85, 95% CI 1.40–16.65).

The proportion of respondents who answered that they had received education in the field of pharmacovigilance (E3) appeared to be affected by all sociodemographic variables in the univariate analysis. However, in the multivariate analysis, only employment type and training experience were found to have a significant impact. The proportion of individuals who responded that they had received education was significantly higher in respondents in the academic field compared with self-employed KMDs (OR 3.55, 95% CI 1.31–9.59) and in specialists compared with general practitioners (OR 1.84, 95% CI 1.01–3.32).

4. Discussion

This study investigated the knowledge, attitudes, and experiences of KMDs regarding the SR of ADEs through an anonymous online survey. Although most KMDs expressed positive attitudes toward SR, the actual reporting rate was very low (5%). The most frequently cited barrier was insufficient knowledge—particularly concerning the national spontaneous reporting system SRS, including the existing inclusion of licensed herbal medicinal products HMPs.

Responses to the questions about currently included drug types (K4) and opinions on what should be included (A6) revealed a significant knowledge gap. While KMDs strongly supported the expansion of the SRS to include all HMs, including both licensed HMPs and self-prepared herbal medicines SPHMs, they were often unaware of the current scope of the system. This discrepancy underscores the urgent need for targeted education, strategic promotion, and improved communication about the national SRS.

In Korea, the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS) includes only licensed HMPs and HRMs in the SRS, excluding SPHMs despite their common use by KMDs. Expanding the scope of the SRS to cover all HMs is critical for building a comprehensive pharmacovigilance system. Our findings suggest that KMDs are supportive of this change.

These findings are consistent with international literature identifying lack of knowledge ("ignorance"), uncertainty in causality assessment ("diffidence"), and complexity of the reporting process ("lethargy") as key barriers to reporting [

8]. In our study, these same three factors were the most frequently cited. Notably, a distinctive barrier identified in this context was “fear”—the concern that reporting ADEs could fuel public criticism or legal scrutiny of HMs. This fear, rooted in interprofessional tension between KM and Western medicine (WM) communities, is less commonly emphasized in other healthcare settings.

In Korea, KMDs often hesitate to engage in SR for fear that such actions could serve as ammunition in ongoing debates questioning the safety and scientific legitimacy of HMs. This fear is exacerbated by historical tension and competition between KM and WM, and a persistent public skepticism toward HMs [

17]. This is despite the fact that the majority of HMs prescribed by KMDs—whether licensed HMPs or SPHMs—are subject to strict government regulations, manufactured or prepared using quality-assured HRMs. Under these circumstances, most ADEs are likely to be rare and idiosyncratic, rather than due to quality defects such as contamination, misuse, or misidentification [

10,

11]. Nonetheless, when ADEs are reported or publicized, the lack of contextualization often leads to general negative perceptions toward HMs and KMDs. Therefore, to promote SR among KMDs, it is not enough to simply raise awareness or simplify the reporting process. Broader, systemic approaches—such as government-led efforts to ease interprofessional conflicts and foster public trust—are essential for cultivating a reporting culture and collecting meaningful real-world safety data.

Although nearly 90% of KMDs agreed that their participation in SR is important, only a minority had received formal training, mostly through academic institutions and specialty societies. These groups demonstrated greater awareness, higher reporting rates, and a stronger sense of responsibility, indicating their potential to serve as leaders in promoting SR education and mentorship within the KM community.

Educational interventions should go beyond one-time lectures. Research indicates that hands-on, practical training has a greater and more sustained impact on reporting behavior [

18,

19,

20], though these effects may diminish over time without reinforcement [

8,

21]. Therefore, incorporating structured and recurrent training—starting from undergraduate education and continuing through professional development—is vital to overcoming entrenched barriers.

Finally, several limitations must be acknowledged. This study’s voluntary and self-reported design may have introduced selection and recall biases. Respondents may have had a preexisting interest in pharmacovigilance, and the results may not fully represent all KMDs. Nevertheless, the findings offer valuable insights into the current state of SR within KM and point to actionable paths forward.

5. Conclusions

This cross-sectional survey highlights that, despite generally positive attitudes toward the spontaneous reporting of ADEs, KMDs show low actual participation—primarily due to limited knowledge, uncertainty, and procedural burden. These barriers are similar to those observed internationally, but uniquely compounded in Korea by social and professional tension between KM and WM communities, leading to fear of criticism and reputational harm.

To increase SR rates among KMDs, efforts must extend beyond basic awareness campaigns. A multifaceted approach is required—one that improves knowledge, clarifies the scope of the SRS, and addresses interprofessional conflicts and societal distrust toward HMs. Expanding the inclusion of all HMs within the national SRS and ensuring transparency and fairness in ADE assessment will be essential steps.

Academia and specialist KMDs, while representing a small proportion of the profession, are well-positioned to lead educational initiatives and foster a culture of patient safety. Ultimately, greater engagement of KMDs in pharmacovigilance will contribute to building reliable safety data for HMs, thereby supporting their responsible use, improving patient outcomes, and advancing public health in an integrated healthcare system.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

https://www.mdpi.com/article/doi/s1, Table S1: Sociodemographic factors affecting respondents’ knowledge, attitudes, and experiences of spontaneous reporting.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K.; methodology, M.K. and J.J.; software, J.J.; validation, M.K. and J.J.; formal analysis, J.J.; investigation, M.K. and D.C.; data curation, J.J.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K. and H.S.; writing—review and editing, M.K., H.S., J.J. and D.C.; visualization, M.K. and J.J.; supervision, D.C.; project administration, D.C.; funding acquisition, D.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: RS-2023-KH139286).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was by the Institutional Review Board of Dongguk University Ilsan Oriental Hospital (DUIOH IRB 2024-07-001-001 and 16 Oct 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the anonymous nature of the survey and the absence of personally identifiable information.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADE |

Adverse drug event |

| CI |

confidence interval |

| HM |

Herbal medicine |

| HMP |

Licensed herbal medicinal products |

| HRM |

Herbal raw material |

| KM |

Traditional Korean medicine |

| KMD |

Korean medicine doctor |

| KMI |

Traditional Korean medical institutions |

| KSDC |

Korean social science data center |

| MFDS |

Ministry of Food and Drug Safety |

| OR |

Odds ratio |

| PIDM |

Programme for International Drug Monitoring |

| RDSC |

Regional drug safety center |

| SPHM |

Self-prepared herbal medicine |

| SR |

Spontaneous reporting |

| SRS |

Spontaneous reporting system |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| WM |

Western medicine |

References

- Bailey, C.; Peddie, D.; Wickham, M.E.; Badke, K.; Small, S.S.; Doyle-Waters, M.M.; et al. Adverse drug event reporting systems: a systematic review. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 82, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noguchi, Y.; Tachi, T.; Teramachi, H. Detection algorithms and attentive points of safety signal using spontaneous reporting systems as a clinical data source. Brief. Bioinform. 2021, 22, bbab347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uppsala Monitoring Centre Website. Available online: https://who-umc.org (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Hazell, L.; Shakir, S.A. Under-reporting of adverse drug reactions. Drug Saf. 2006, 29, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, M. Pharmacovigilance and spontaneous adverse drug reaction reporting: Challenges and opportunities. Perspect. Clin. Res. 2022, 13, 177–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alatawi, Y.M.; Hansen, R.A. Empirical estimation of under-reporting in the U.S. Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2017, 16, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervantes-Arellano, M.J.; Castelán-Martínez, O.D.; Marín-Campos, Y.; Chávez-Pacheco, J.L.; Morales-Ríos, O.; Ubaldo-Reyes, L.M. Educational interventions in pharmacovigilance to improve the knowledge, attitude and the report of adverse drug reactions in healthcare professionals: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. DARU J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 32, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Abeijon, P.; Costa, C.; Taracido, M.; Herdeiro, M.T.; Torre, C.; Figueiras, A. Factors Associated with Underreporting of Adverse Drug Reactions by Health Care Professionals: A Systematic Review Update. Drug Saf. 2023, 46, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on safety monitoring of herbal medicines in pharmacovigilance systems. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/43034/9241592214_eng.pdf (accessed on day month year).

- Shaw, D.; Graeme, L.; Pierre, D.; Elizabeth, W.; Kelvin, C. Pharmacovigilance of herbal medicine. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 140, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhury, A.; Singh, P.A.; Bajwa, N.; Dash, S.; Bisht, P. Pharmacovigilance of herbal medicines: Concerns and future prospects. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 309, 116383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Woo, Y.; Han, C.-h. Current status of the spontaneous reporting and classification/coding system for herbal and traditional medicine in pharmacovigilance. Integr. Med. Res. 2021, 10, 100467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skalli, S.; Soulaymani Bencheikh, R. Pharmacovigilance of herbal medicines in Africa: Questionnaire study. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 171, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Korea Institute of Drug Safety and Risk Management (KIDS) Website. Available online: https://www.drugsafe.or.kr (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Choi, Y.; Shin, H.-K. Adverse events associated with herbal medicine products reported in the Korea Adverse Event Reporting System from 2012 to 2021. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1378208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S. Establishment and activation of a reporting system related adverse events of herbal medicine and herbal medicine preparations: A research project report. https://scienceon.kisti.re.kr/srch/selectPORSrchReport.do?cn=TRKO201000015873 (published 2007; accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Ku, N.-P.; Seol, S.-S. J. Limits of Innovation in Korean Medicine Industry. Korea Technol. Innov. Soc. 2015, 18, 667–692. Available online: https://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/ci/sereArticleSearch/ciSereArtiView.kci?sereArticleSearchBean.artiId=ART002074346 (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Schutte, T.; Tichelaar, J.; Reumerman, M.O.; van Eekeren, R.; Rissmann, R.; Kramers, C.; et al. Pharmacovigilance Skills, Knowledge and Attitudes in our Future Doctors - A Nationwide Study in the Netherlands. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2017, 120, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkalmi, R.M.; Hassali, M.A.; Ibrahim, M.I.M.; Widodo, R.T.; Efan, Q.M.; Hadi, M.A. Pharmacy students’ knowledge and perceptions about pharmacovigilance in Malaysian public universities. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2011, 75, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.J.; Hwang, S.Y. Impact of safety climate perception and barriers to adverse drug reaction reporting on clinical nurses' monitoring practice for adverse drug reactions. Korean J. Adult Nurs. 2018, 30, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Han, C.-h.; Han, C.-h. A survey on the impact of a pharmacovigilance practice training course for future doctors of Korean medicine on their knowledge, attitudes, and perception. J. Korean Med. 2021, 42, 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Concordance rates of responses to the types of drugs currently thought to be included in the spontaneous reporting system and those that should be included. Figure 4 and A6 of the survey. K4: Which of the following do you believe are currently included in the official ADE targets under the domestic SRS? (Allowing for multiple selections). A6: Which of the following do you believe should be mandatorily included as ADE-reporting targets in domestic SRS? (Allowing for multiple selections). D, decoction; HMP, licensed herbal medicinal products manufactured by pharmaceutical companies; HRM, medicinal herbs as raw materials; O, other dosage forms than decoction such as pills or powder etc.; OTC, over-the-counter drugs; PD, prescription drugs; SPHM, self-prepared herbal medicines by Korean medical institutions.

Figure 1.

Concordance rates of responses to the types of drugs currently thought to be included in the spontaneous reporting system and those that should be included. Figure 4 and A6 of the survey. K4: Which of the following do you believe are currently included in the official ADE targets under the domestic SRS? (Allowing for multiple selections). A6: Which of the following do you believe should be mandatorily included as ADE-reporting targets in domestic SRS? (Allowing for multiple selections). D, decoction; HMP, licensed herbal medicinal products manufactured by pharmaceutical companies; HRM, medicinal herbs as raw materials; O, other dosage forms than decoction such as pills or powder etc.; OTC, over-the-counter drugs; PD, prescription drugs; SPHM, self-prepared herbal medicines by Korean medical institutions.

Figure 2.

Sociodemographic factors of affecting respondents’ knowledge, attitudes, and experiences of spontaneous reporting. K1: I know that ADEs can be reported to the KIDS or RDSCs; K2: I know that ADEs related to HMs can also be reported to the KIDS or RDSCs; K3: I think that ADEs should be reported to the KIDS or RDSCs even if the causal relationship with the drug is uncertain; A1: I agree that KMDs should actively participate in SR; A2: I believe that the role of KMDs is important in SRS; E1: I have ever experienced or witnessed an ADE following drug administration; E2: I have ever reported an ADE to the relevant authority; E3: I have received training on PV, including SRS procedures and causality assessment. AC, academia group engaged in medical education and/or research; CI, 95% confidence interval; Emp, employed KMD; Int, internship course; KMD, traditional Korean medicine doctor; Local, local clinic of traditional Korean medicine; OMI, other medical institutions; OR, odds ratio; P, p-value; PFT, P for trend; SEmp, self-employed KMD; SP, specialists who completed internship and residency training course; URI, universities or research institute

Figure 2.

Sociodemographic factors of affecting respondents’ knowledge, attitudes, and experiences of spontaneous reporting. K1: I know that ADEs can be reported to the KIDS or RDSCs; K2: I know that ADEs related to HMs can also be reported to the KIDS or RDSCs; K3: I think that ADEs should be reported to the KIDS or RDSCs even if the causal relationship with the drug is uncertain; A1: I agree that KMDs should actively participate in SR; A2: I believe that the role of KMDs is important in SRS; E1: I have ever experienced or witnessed an ADE following drug administration; E2: I have ever reported an ADE to the relevant authority; E3: I have received training on PV, including SRS procedures and causality assessment. AC, academia group engaged in medical education and/or research; CI, 95% confidence interval; Emp, employed KMD; Int, internship course; KMD, traditional Korean medicine doctor; Local, local clinic of traditional Korean medicine; OMI, other medical institutions; OR, odds ratio; P, p-value; PFT, P for trend; SEmp, self-employed KMD; SP, specialists who completed internship and residency training course; URI, universities or research institute

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents (n=1,021).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents (n=1,021).

| Characteristics |

Categories |

No(%) |

| Sex |

Male |

668 (65.4%) |

| Female |

353 (34.6%) |

| Age group (years) |

20-29 |

103 (10.1%) |

| 30-39 |

337 (33.0%) |

| 40-49 |

317 (31.0%) |

| 50-59 |

215 (21.1%) |

| ≥ 60 |

49 ( 4.8%) |

| Clinical experience1 (years) |

< 5 |

199 (19.5%) |

| 5-9 |

197 (19.3%) |

| 10-19 |

343 (33.6%) |

| ≥ 20 |

282 (27.6%) |

| Employment type |

Self-employed KMD |

464 (45.4%) |

| Employed KMD |

438 (42.9%) |

| Academia3

|

119 (11.7%) |

| Workplace |

Local KM clinic |

642 (62.9%) |

| Other medical institutions |

360 (35.3%) |

| Training experience2

|

No |

19 ( 1.9%) |

| Internship course |

618 (60.5%) |

| Internship + residency training course |

126 (12.3%) |

Table 2.

Respondents’ knowledge, attitudes and experiences regarding spontaneous reporting.

Table 2.

Respondents’ knowledge, attitudes and experiences regarding spontaneous reporting.

| Categories |

Question No. |

Questions |

Choices |

No (%) |

P-value |

| Knowledge |

K1 |

Are you aware that ADEs can be reported to the KIDS or RDSCs? |

No$Yes |

463 (45%)$558 (55%) |

<0.01 |

| K2 |

Are you aware that ADEs related to HMs can also be reported to the KIDS or RDSCs? |

No$Yes |

553 (54%)$468 (46%) |

0.01 |

| K3 |

Do you think that ADEs should be reported to the KIDS or RDSCs even if the causal relationship with the drug is uncertain? |

No$Yes |

421 (41%)$600 (59%) |

<0.01 |

| K4 |

Which of the following do you believe are currently included in the official ADE targets under the domestic SRS? (AMS) |

The results are in Fig. 1. |

| Attitudes |

A1 |

Do you agree that KMDs should actively participate in SR? |

No$Yes |

121 (12%)$900 (88%) |

<0.01 |

| A2 |

Do you believe that the role of KMDs is important in SRS? |

No$Yes |

108 (11%)$913 (89%) |

<0.01 |

| A3 |

Which of the following do you agree with are the potential outcomes of SR? (AMS) |

The results are in Table 3. |

| A4 |

What are the reasons for not reporting ADEs in the past? (AMS) |

The results are in Table 4. |

| A5 |

Which of the following measures do you think are appropriate for promoting SR by KMDs? (AMS) |

The results are in Table 5. |

| A6 |

Which of the foloowing do you believe should be mandotorily included as ADE reporting targets in the domestic SRS? (AMS) |

The results are in Fig. 1. |

| Experiences |

E1 |

Have you ever experienced or witnessed an ADE following drug administration? |

No$Yes |

498 (49%)$523 (51%) |

0.43 |

| E2 |

Have you ever reported ad ADE to the relevant authority? |

No$Yes |

965 (95%)$56 (5%) |

<0.01 |

| E3 |

Have you ever received training on PV, including SRS procedures and causality assessment? |

No$Yes |

928 (91%)$93 (9%) |

<0.01 |

| E4 |

If yes to E3, through which channel did you receive the training (AMS) |

College of KM$The others |

39 (41%)$57 (59%) |

0.07 |

Table 3.

Respondents’ predictions about potential outcomes of spontaneous reporting (multiple selections allowed) (n = 1,021)*.

Table 3.

Respondents’ predictions about potential outcomes of spontaneous reporting (multiple selections allowed) (n = 1,021)*.

| Choices |

No (%) |

| Knowledge for safe use of drugs is accumulated. |

798 (78%) |

| Improves patients safety. |

734 (72%) |

| Increases social trust in the safety of drugs. |

486 (48%) |

| Causes legal disputes. |

291 (29%) |

| Heightens social tensions about the risk of drugs. |

288 (28%) |

| Wastes time reporting. |

200 (20%) |

| Increases risk of medical errors. |

155 (15%) |

| Breaks trust with patients. |

112 (11%) |

| Interferes with the medical process. |

71 (7%) |

| Decreases my medical revenue. |

68 (7%) |

| The individual reporting benefits. |

67 (7%) |

| Knowledge for safe use of drugs is accumulated. |

798 (78%) |

Table 4.

Reasons for not participating in the spontaneous reporting of adverse drug events (multiple selections allowed) (n = 489)*.

Table 4.

Reasons for not participating in the spontaneous reporting of adverse drug events (multiple selections allowed) (n = 489)*.

| Choices |

No (%) |

| Not aware of the existence of the SRS. |

267 (55%) |

| Not aware of the reporting procedure. |

250 (51%) |

| Causality is not unclear. |

223 (46%) |

| Clinical severity is not severe. |

214 (44%) |

| Reporting procedure is complicated and inconvenient. |

109 (22%) |

| Not sure what the suspected drug is. |

121 (25%) |

| Concerned that it will be used as grounds for attacking the safety of HM. |

102 (21%) |

| No benefit nor reward for me. |

96 (20%) |

| Not aware of how to assess causality. |

95 (19%) |

| Too much work and not enough time. |

94 (19%) |

| Concerned about legal issues such as lawsuits with patients. |

76 (16%) |

| SR is not my duty. |

71 (15%) |

| HM is not subject to SR. |

56 (11%) |

| It is a prodromal response to healing and therefore not subject to SR. |

40 (8%) |

| Academically useless. |

32 (7%) |

| Patient personal information should not be disclosed. |

28 (6%) |

| Concerned about legal issues such as lawsuits with pharmaceutical companies or suppliers. |

28 (6%) |

| Concerned about personal information of the reporter being disclosed. |

26 (5%) |

Table 5.

This is a table. Tables should be placed in the main text near to the first time they are cited.

Table 5.

This is a table. Tables should be placed in the main text near to the first time they are cited.

| Choices |

No (%) |

| Simplify reporting procedures. |

645 (63%) |

| Strengthen undergraduate education. |

629 (62%) |

| Establish institutional mechanisms to resolve legal issues of concern. |

569 (56%) |

| Activating post-graduation continuing education and promotion . |

549 (54%) |

| Add SR of ADE function to electronic chart. |

504 (49%) |

| Include HMs in the range of the relief system for adverse drug reactions. |

461 (45%) |

| Providing feedback on reporting results. |

402 (39%) |

| Providing appropriate compensation to the reporters. |

375 (37%) |

| Develop a HM-friendly reporting system. |

343 (34%) |

| KMDs are not required to participate in SR. |

16 (2%) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).