Submitted:

26 May 2025

Posted:

27 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

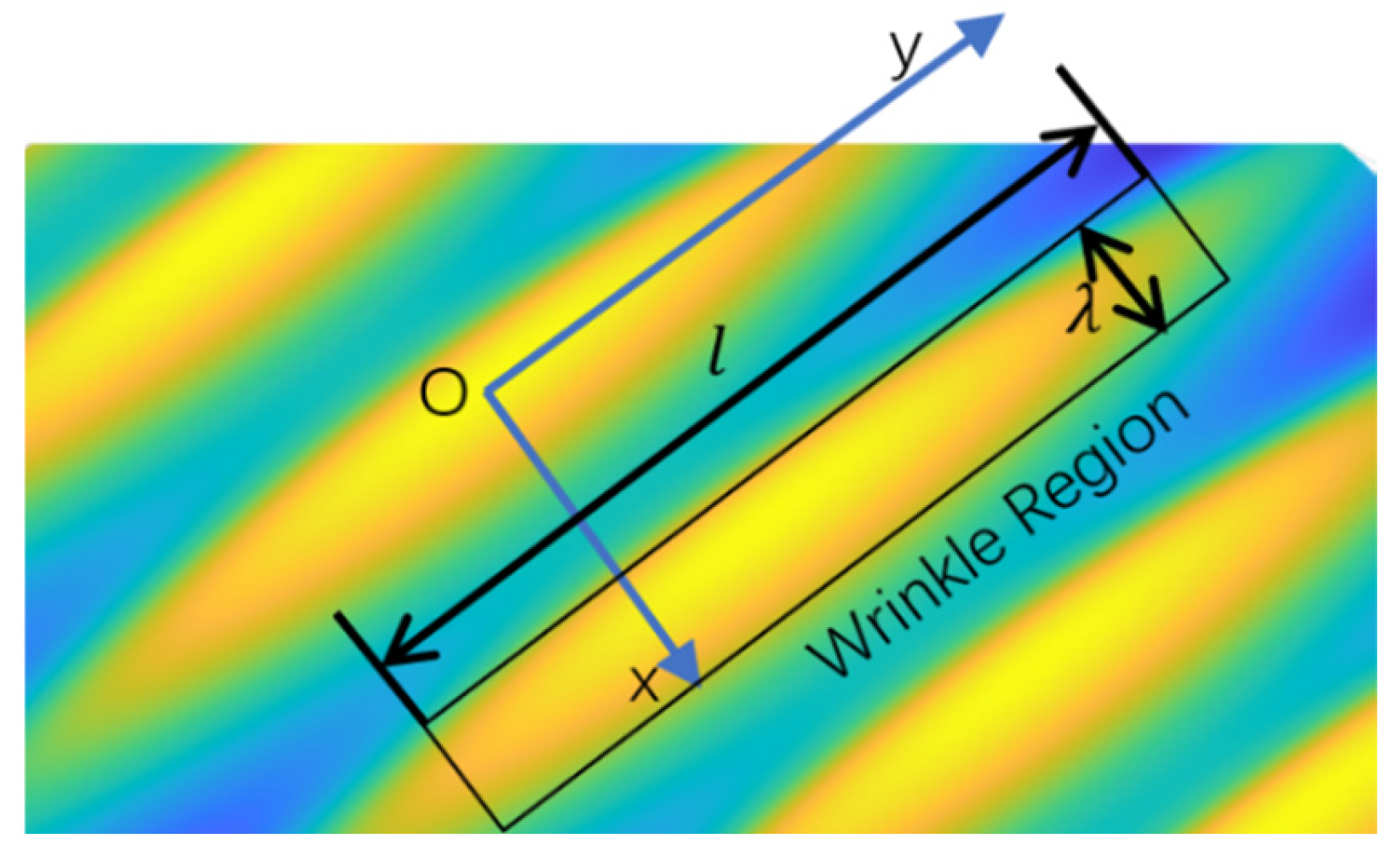

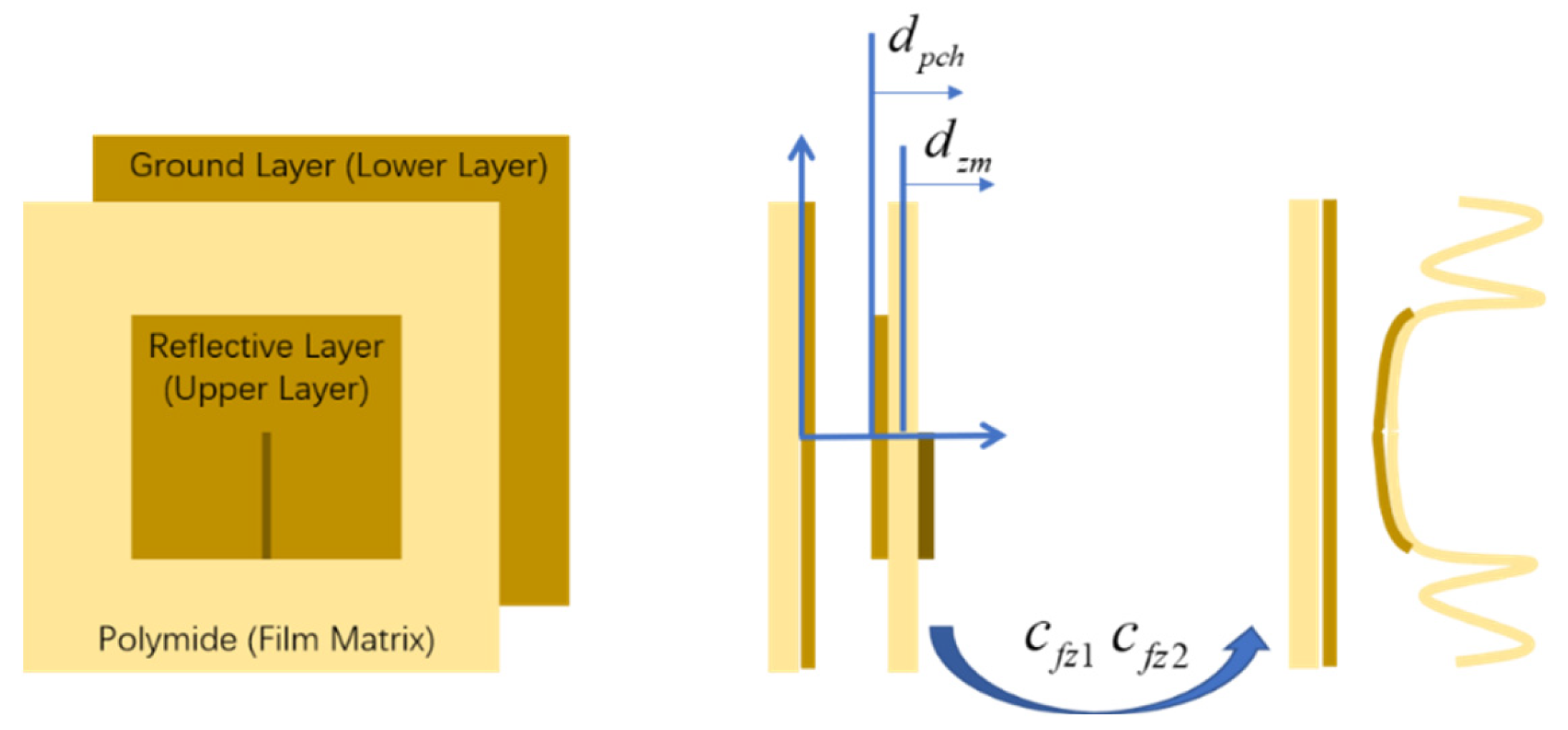

2. Wrinkling of Step-Stiffness Structure and Dual-Domain Displacement Mod

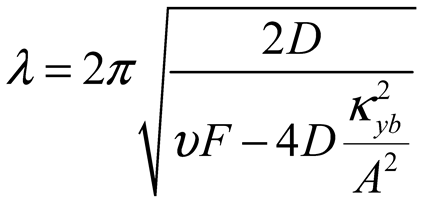

2.1. Wrinkling Mechanism of Step-Stiffness Structure

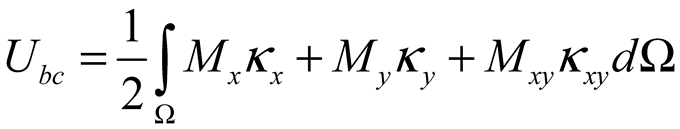

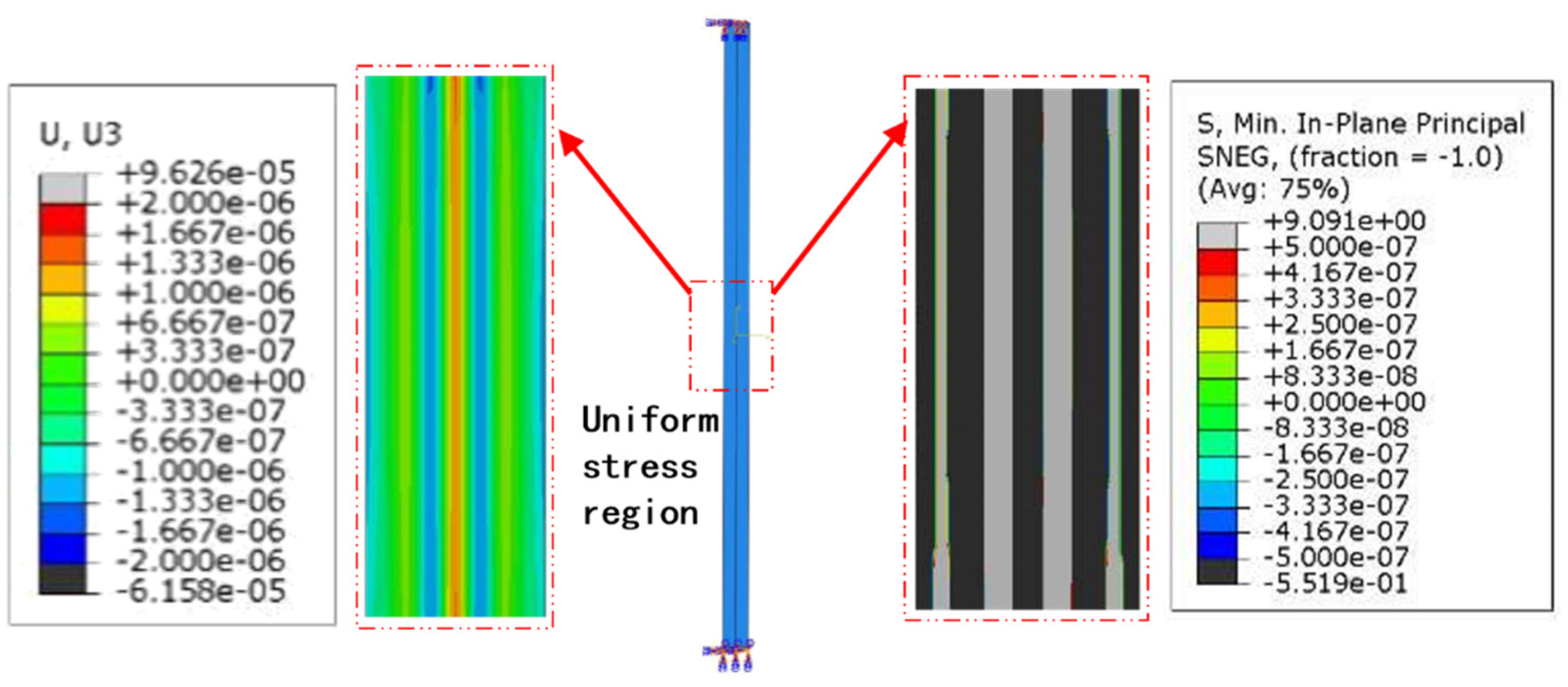

2.2. Surface Deformation of STMA

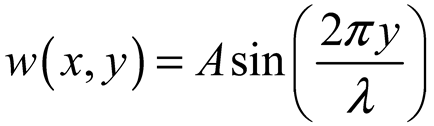

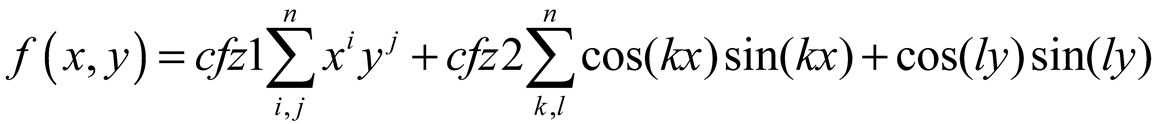

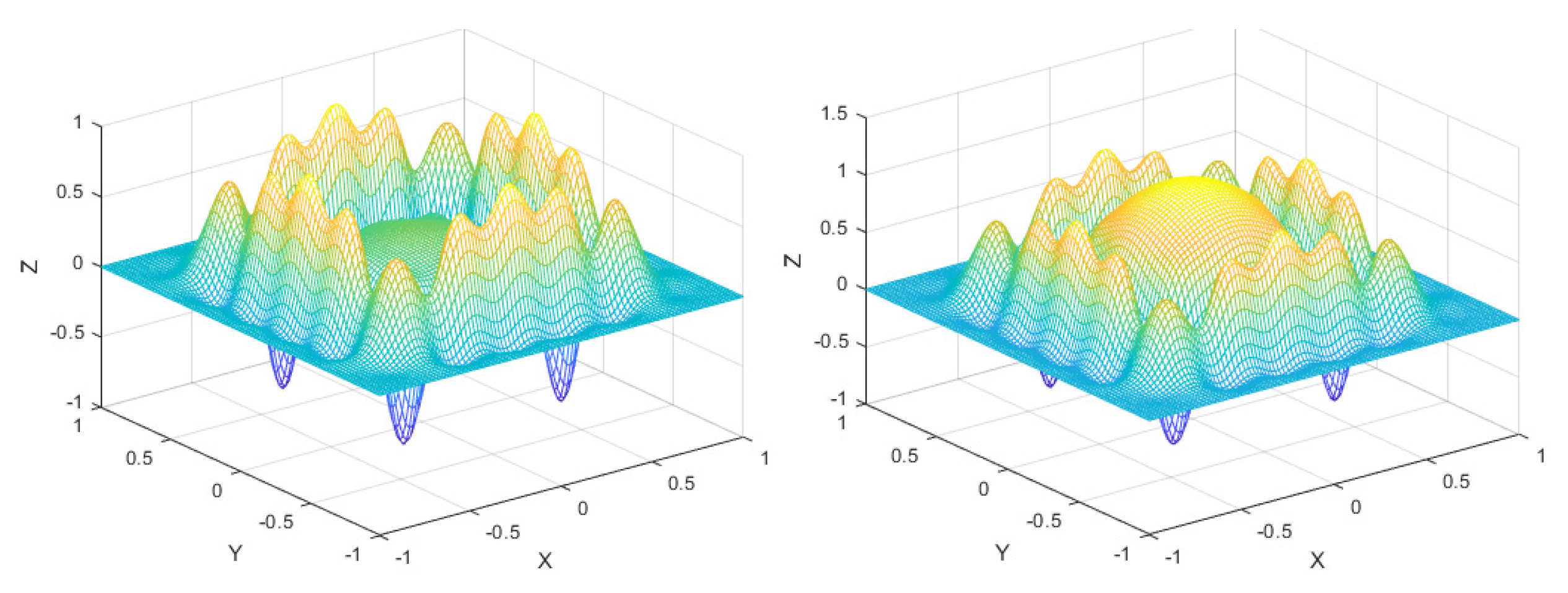

2.3. Dual-Domain Displacement-Driven Function

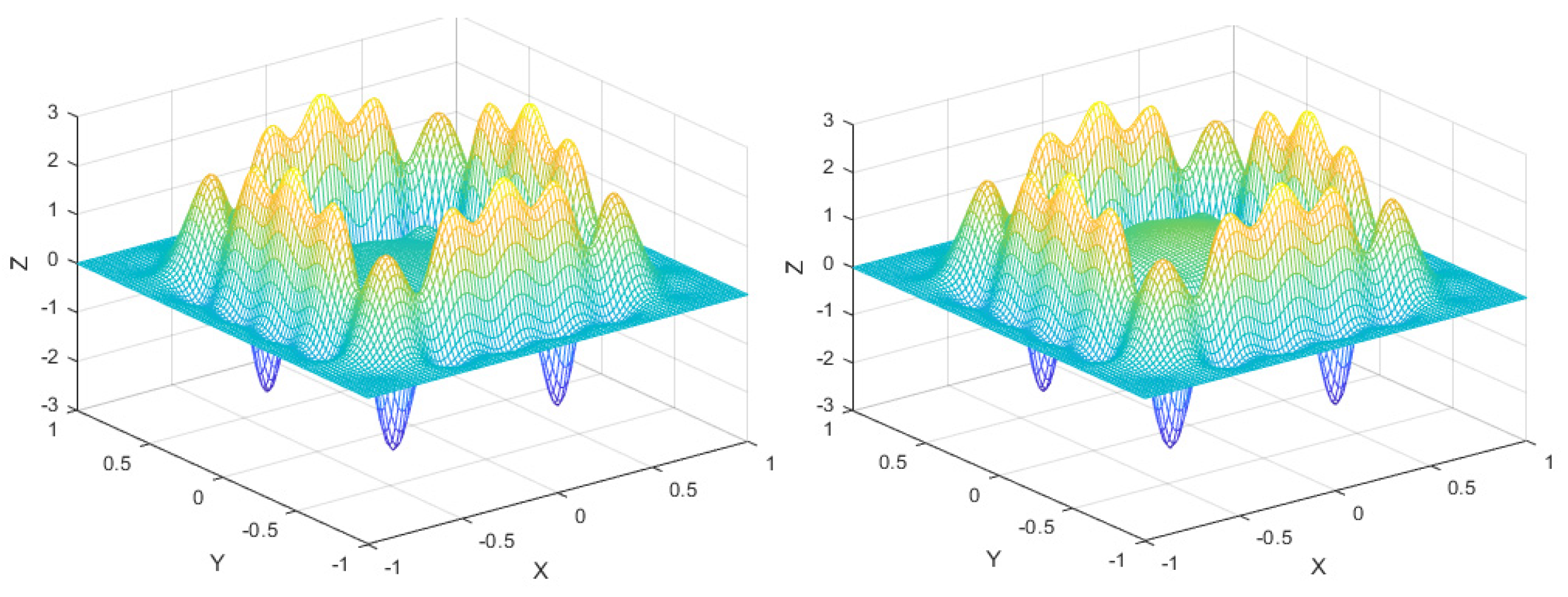

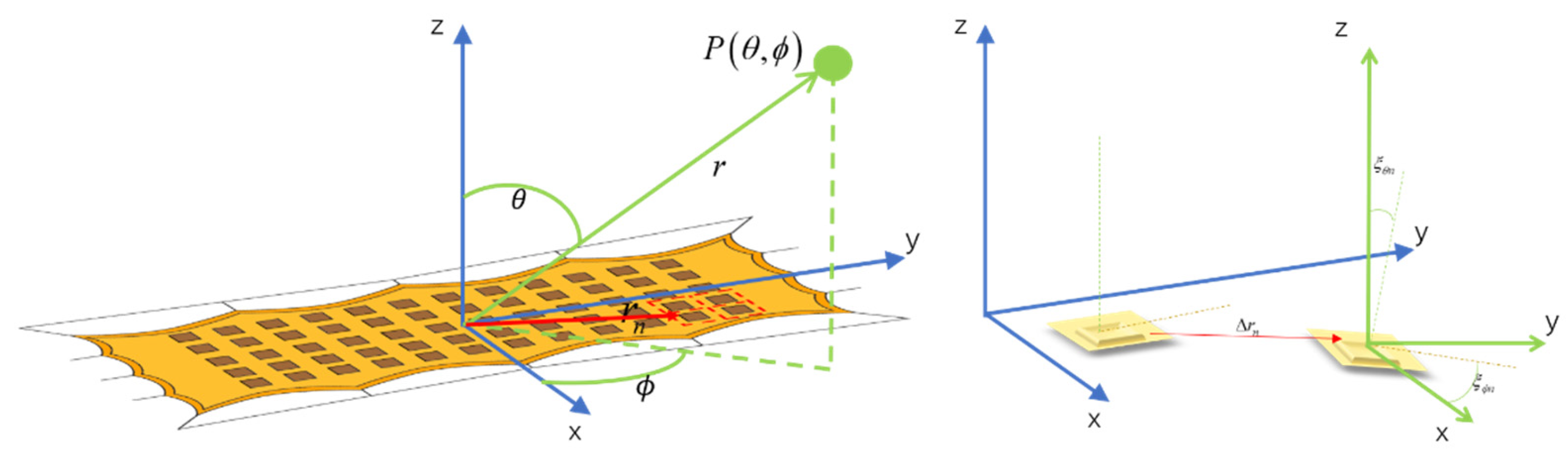

3. Structural-Electromagnetic Coupling Model

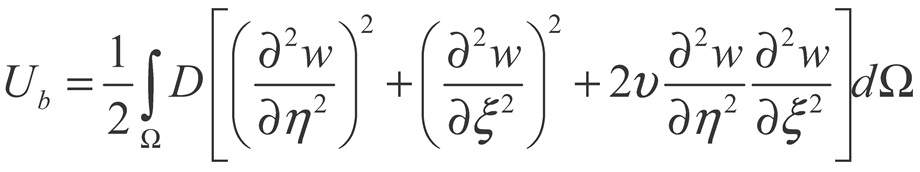

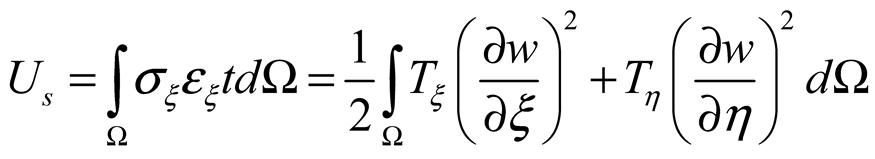

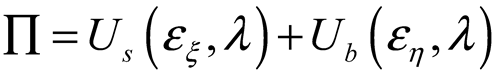

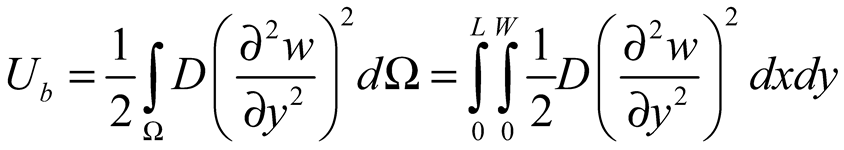

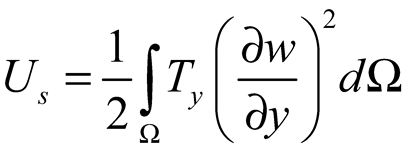

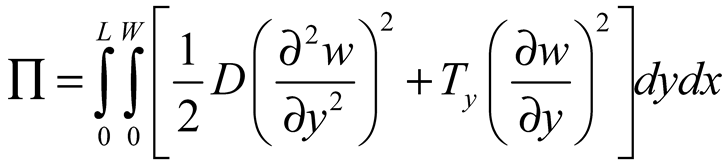

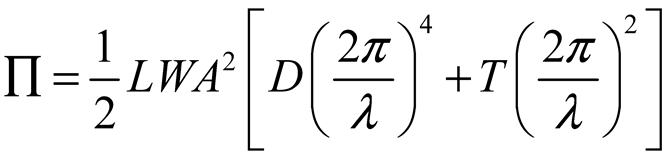

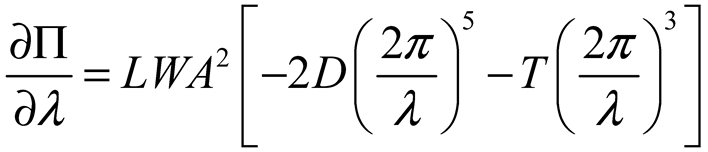

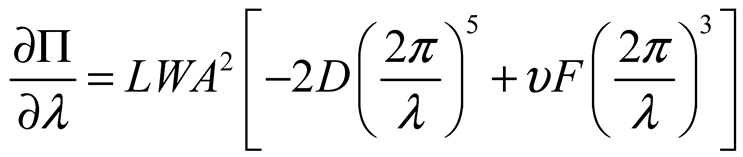

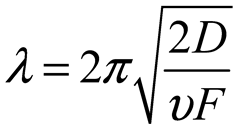

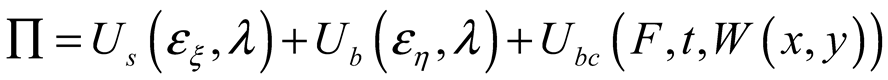

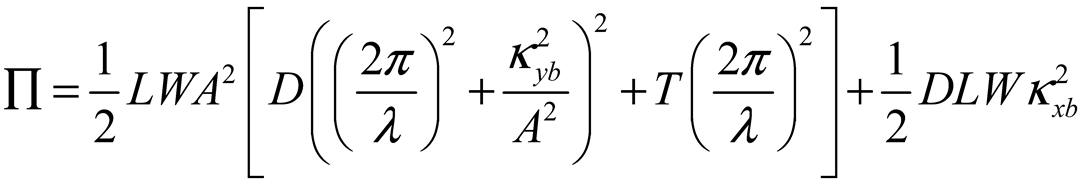

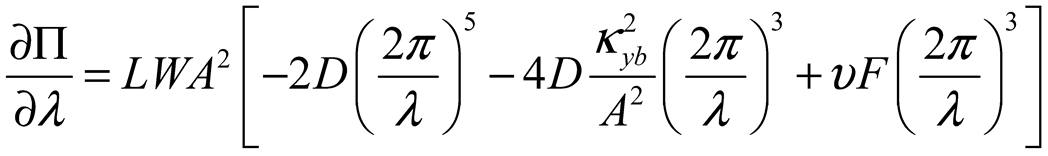

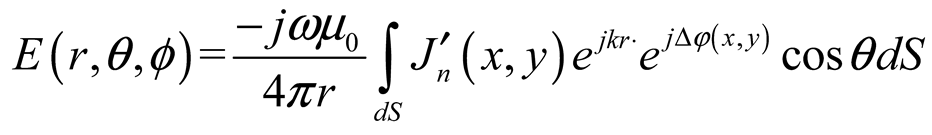

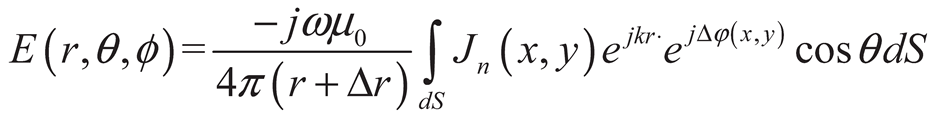

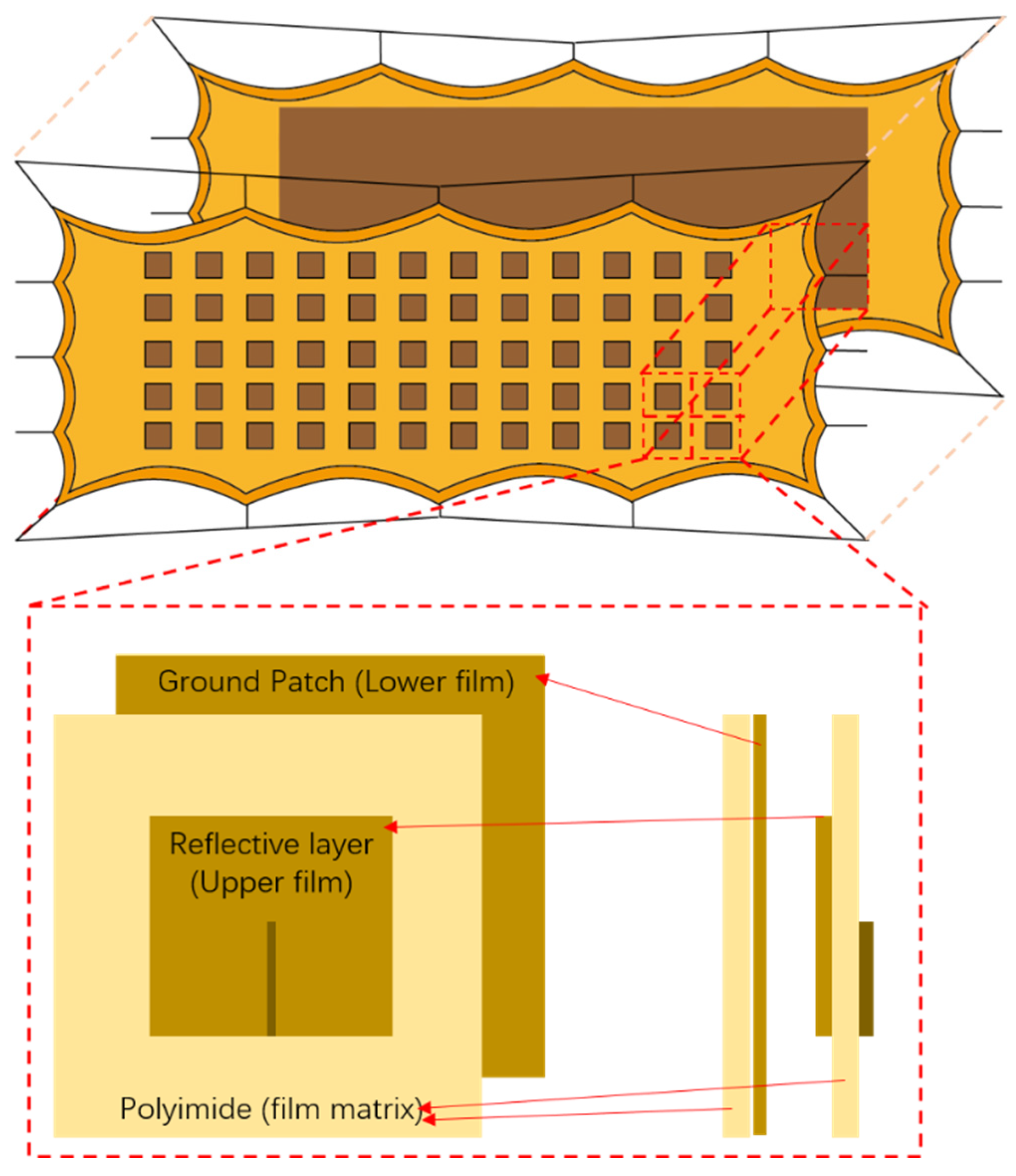

3.1. Electromechanical Coupling Model

3.2. Patch Electro-Magnetic Performance Simulation

4. Discussion

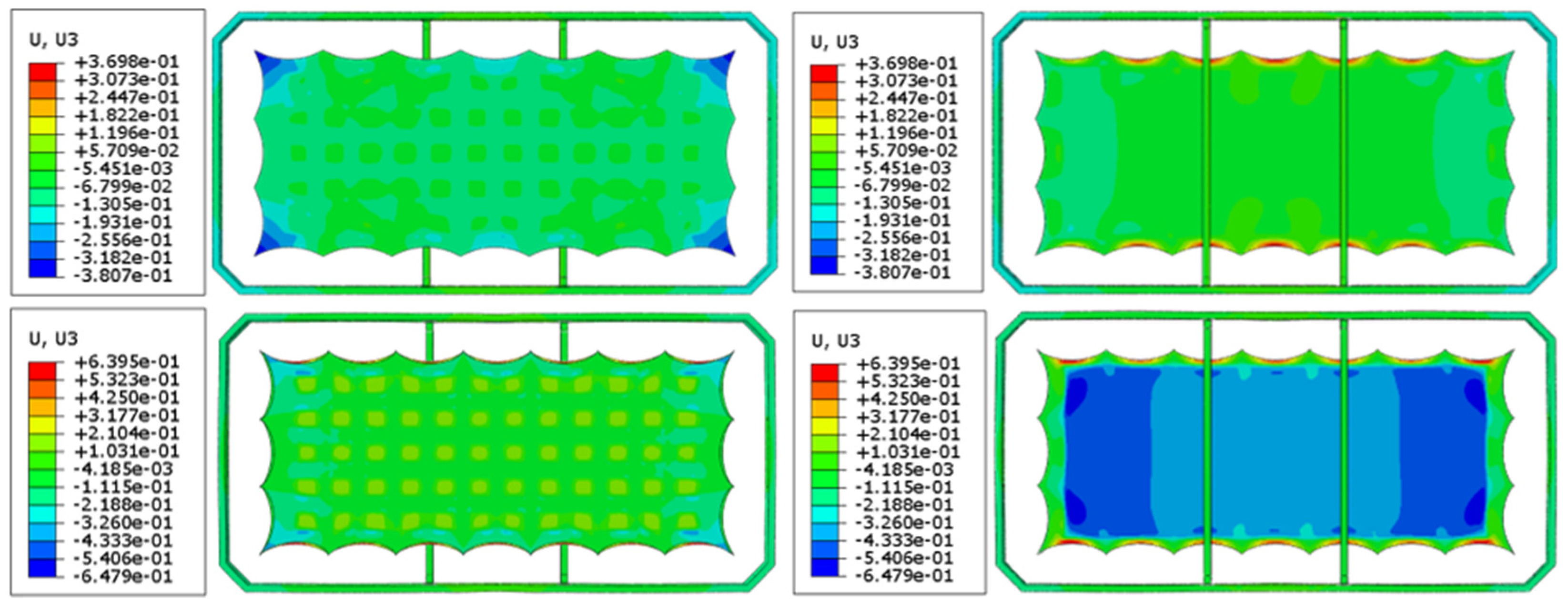

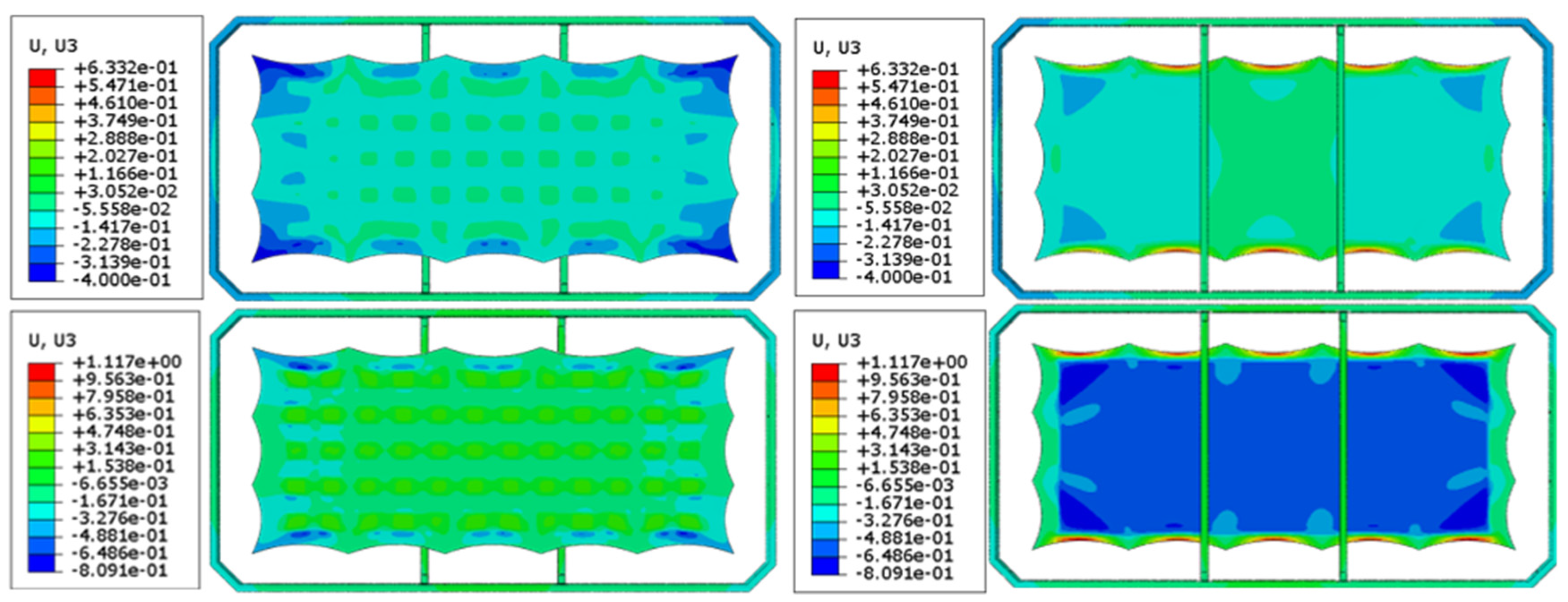

4.1. Dual-Domain Displacement Patch Analysis

4.2. Phased Array Antenna Analysis

5. Conclusions

- A comprehensive electromechanical coupling model was developed, incorporating angular distortions, displacement errors, and current density variations, enabling efficient performance evaluation of deformed copper/membrane patch antennas. The model provides a rapid simulation approach for analyzing the phased array antenna performance under structural deformations.

- The analysis of surface accuracy under different numbers of catenary lines and pre-tension levels revealed that structural deformations impact the antenna’s displacement field, which in turn affects its electromagnetic characteristics. The dual-domain displacement-based electromechanical coupling model effectively characterizes these deformations and their impact on antenna performance.

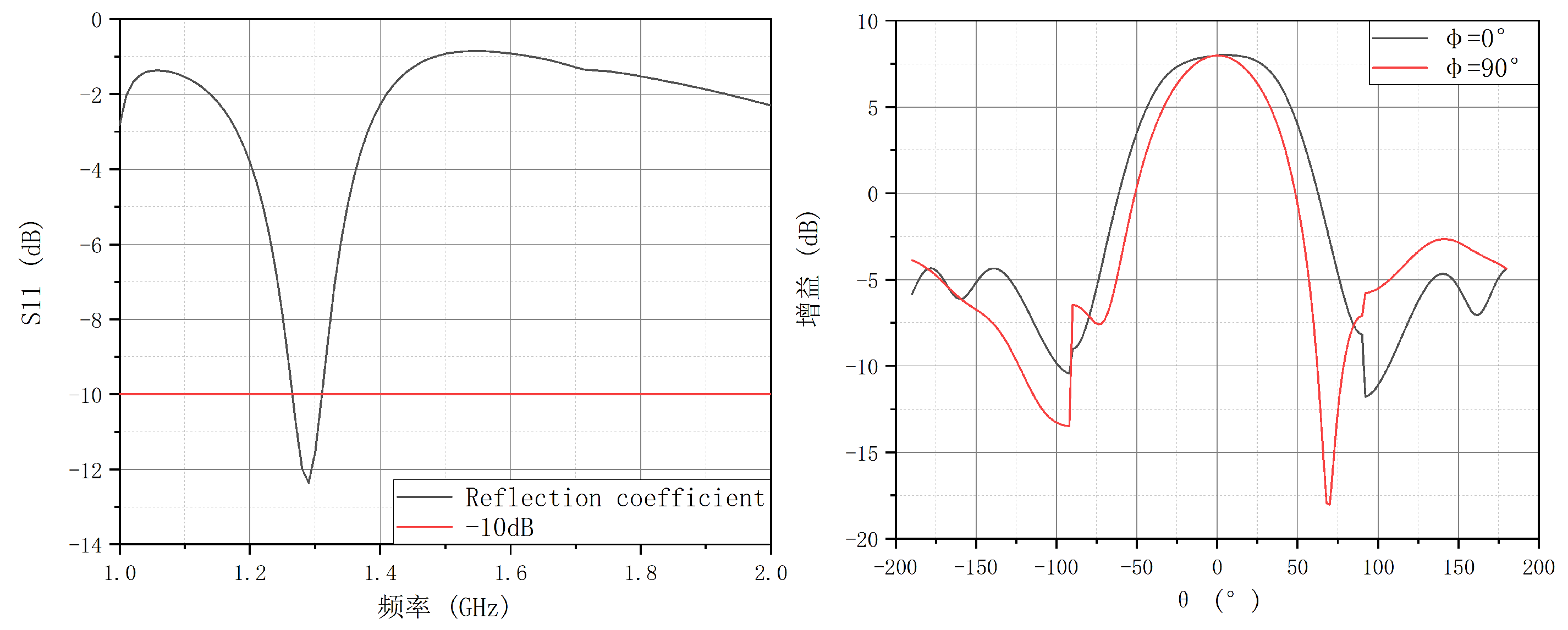

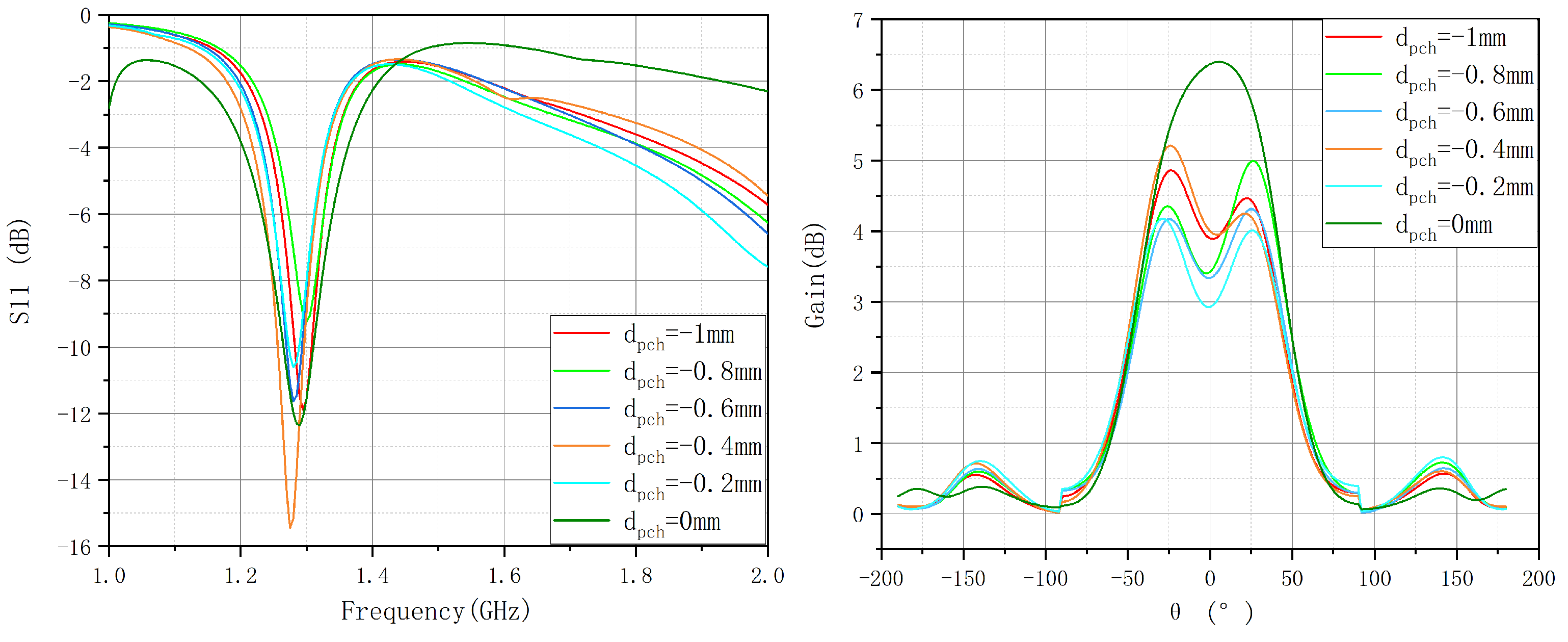

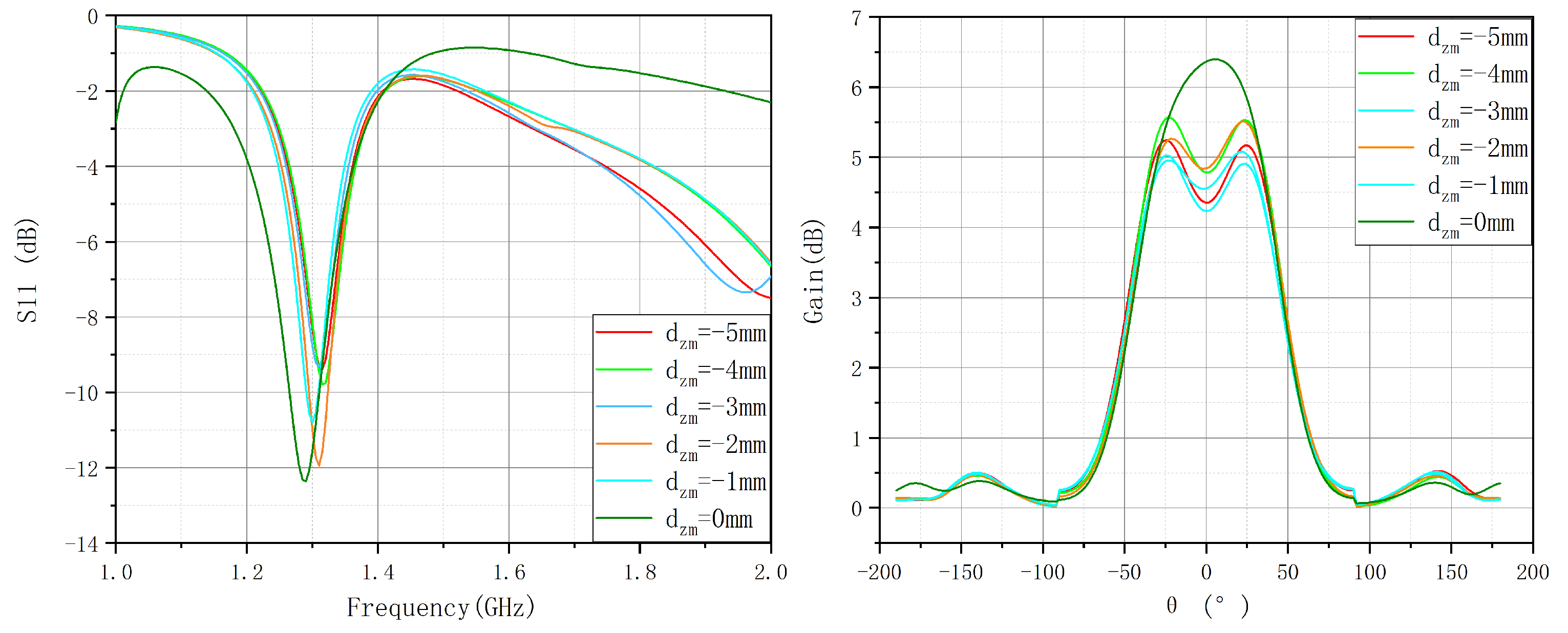

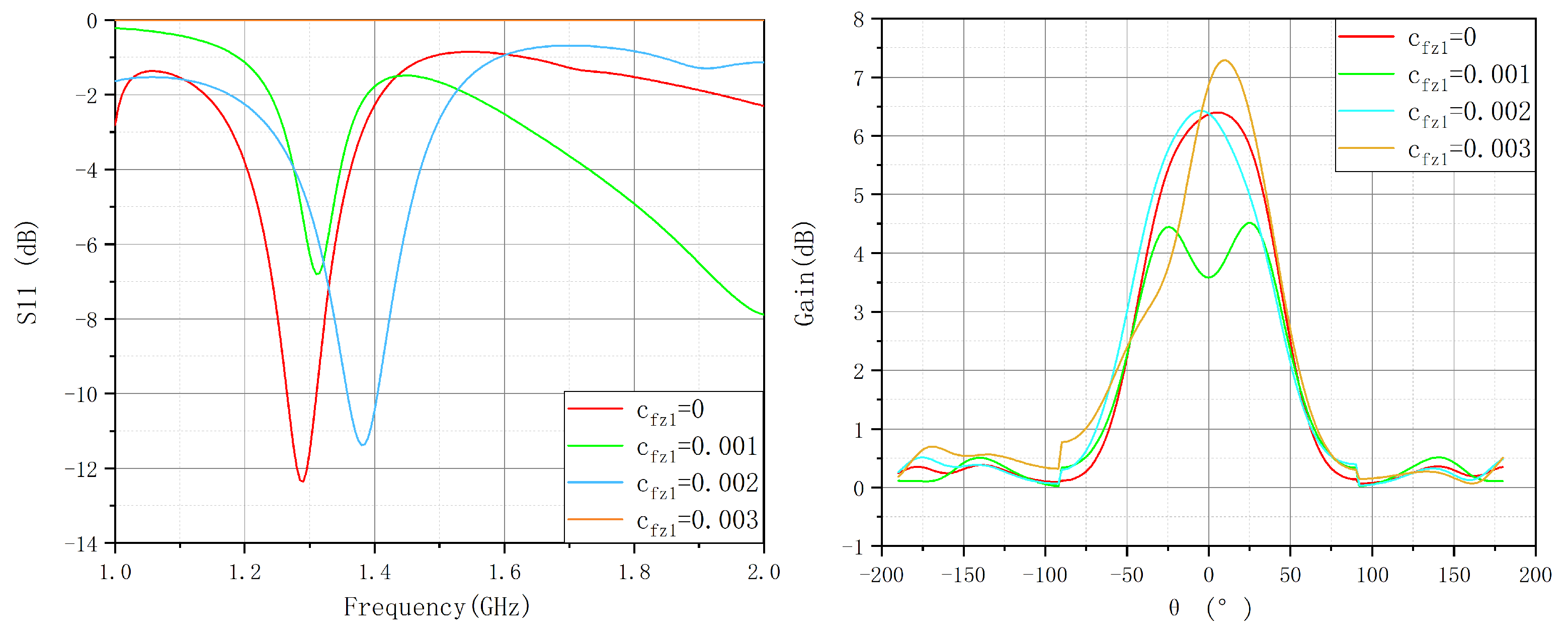

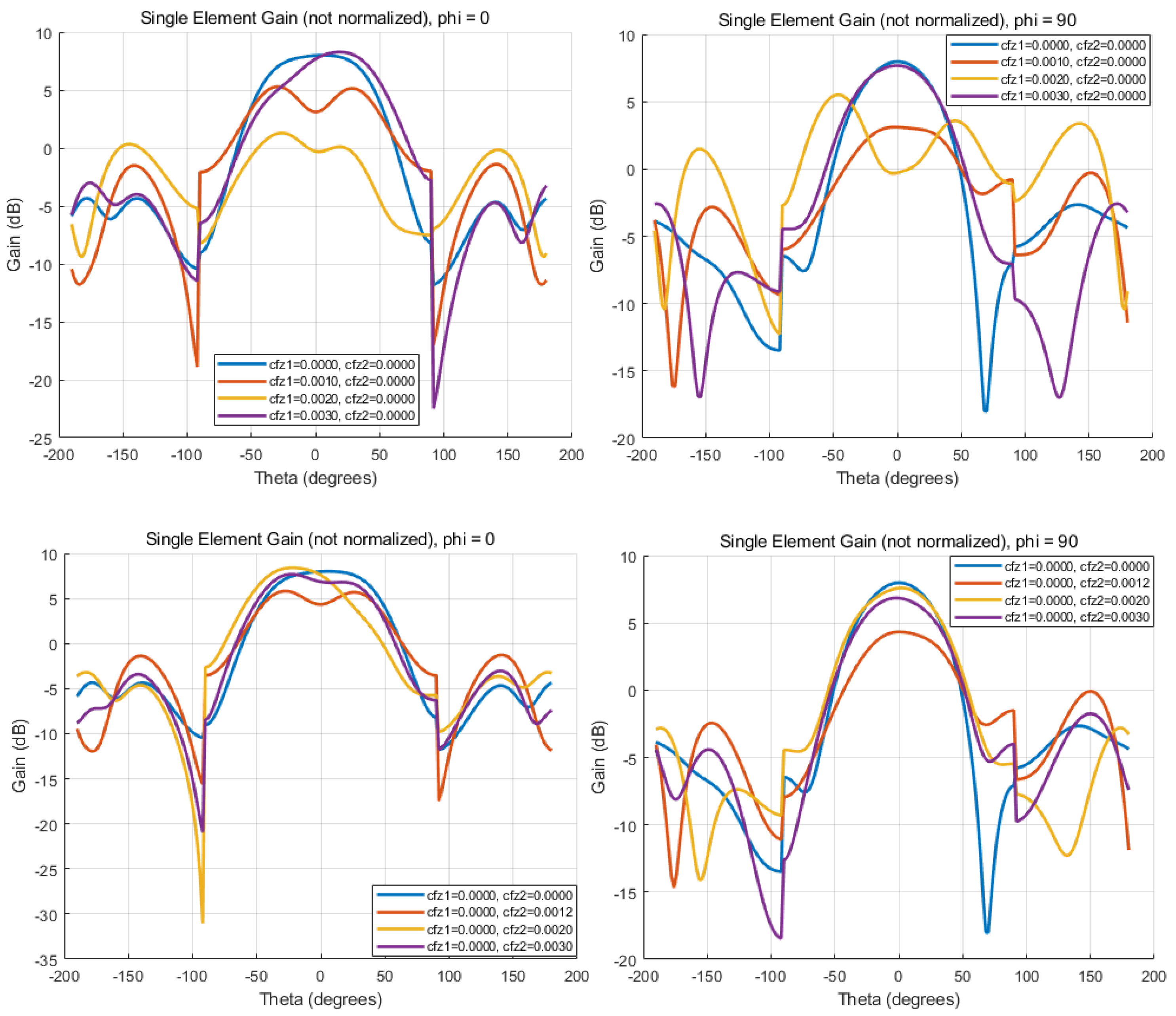

- Gain analysis of individual antenna elements indicated that the main lobe gain shifts with variations in structural parameters. Specifically, influences peak gain values, while significantly alters the sidelobe structure and overall radiation pattern. As increases, the main lobe gain decreases, while sidelobes intensify, suggesting that excessive structural modifications may degrade the radiation pattern and introduce undesired interference.

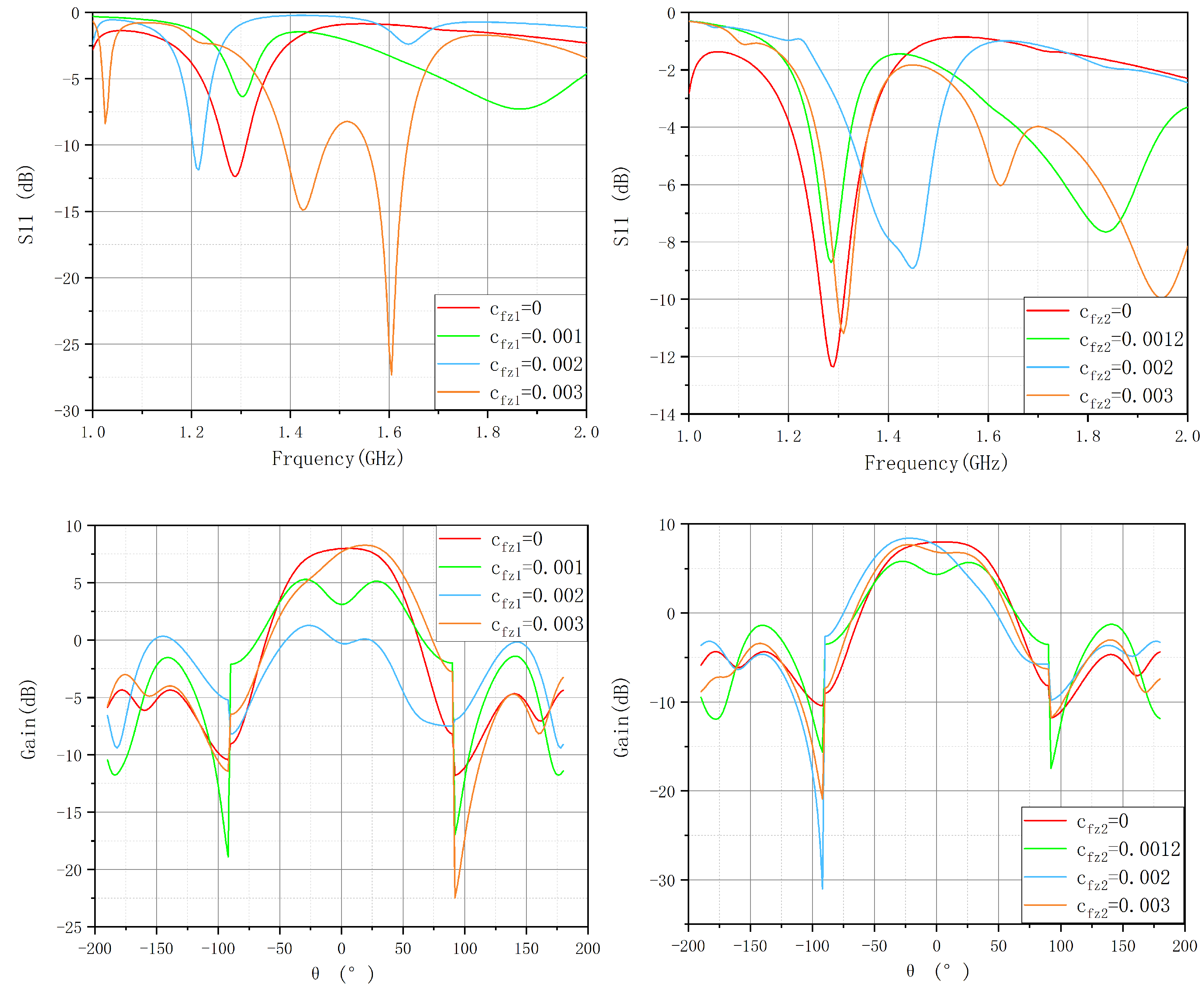

- S-parameter simulations demonstrated that structural deformations cause resonant frequency shifts and impedance mismatches. Increasing and leads to changes in return loss characteristics, particularly at =0.30, where impedance matching significantly deteriorates, potentially compromising the antenna’s operational efficiency at the target frequency of 1.3 GHz.

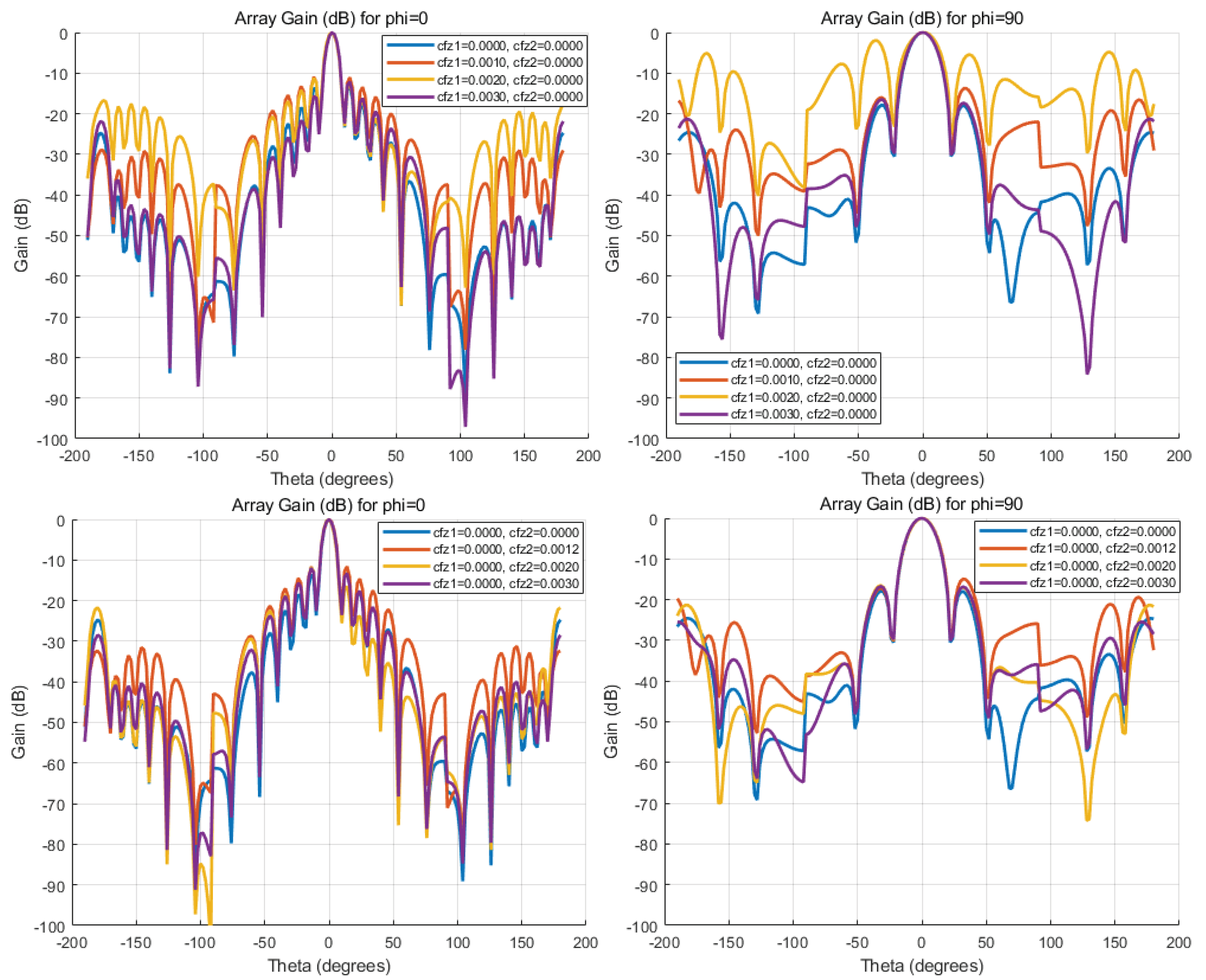

- Phased array total gain analysis showed that the array exhibits high gain in the main lobe direction (θ≈0∘), but the radiation pattern undergoes significant changes with variations in and . An increase in not only reduces main lobe gain but also amplifies sidelobes, which may enhance interference signals and degrade overall system performance. Furthermore, radiation pattern comparisons across different azimuth angles (ϕ) revealed that the antenna maintains symmetry at ϕ=0∘, while gain deformation is more pronounced at ϕ=90∘, indicating that structural modifications affect radiation characteristics differently depending on the azimuth angle.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DASIY | Deployable antenna integralSystem |

| SSDA | Solid surface deployable antenna |

| SAR | Synthetic Aperture Radar |

| STMA | Space-Tensioned Membrane Antenna |

References

- Ma, X.; Li, J.; Ma, J.; Wang, Z.; Shi, C.; Zheng, S.; Cui, Q.; Li, X.; Liu, F.; Guo, H.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y. China’s Space Deployable Structures: Progress and Trends. Engineering 2020, 17(10), 207–219. [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; An, N.; Cong, Q.; Bai, J.-B.; Wu, M.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, T.; Guo, R.; et al. Design, modeling, and manufacturing of high strain composites for space deployable structures. Commun. Eng. 2024, 3, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, B. Large Spaceborne Deployable Antennas (LSDAs) —A Comprehensive Summary. Chin. J. Electron. 2020, 29, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-Q.; Qiu, H.; Li, X.; Yang, S.-L. Review of Large Spacecraft Deployable Membrane Antenna Structures. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2017, 30, 1447–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Ma, X.; Li, H. Research Status and Development Trends of Flexible Tensioned Thin-Film Deployable Space Antennas. China Space Science and Technology 2022, 42(4), 15.

- Shinde, S.D.; Upadhyay, S. Investigation on effect of tension forces on inflatable torus for rectangular multi-layer planar membrane reflector. Mater. Today: Proc. 2022, 72, 1486–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.-J.; Li, M.; Liu, Y.-F.; Geng, X.-Y.; Li, Y.-Y. A Review on the Development of Spaceborne Membrane Antennas. Space: Sci. Technol. 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, C.M.; Huang, R.; Hutchinson, J.W. Formation of surface wrinkles and creases in constrained dielectric elastomers subject to electromechanical loading. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2022, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierunalan, S.; Dassanayake, S.P.; Mallikarachchi, H.M.Y.C.; Upadhyay, S.H. Simulation of ultra-thin membranes with creases. Int. J. Mech. Mater. Des. 2022, 19, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, G.; Abramovich, H. Large Deflections of Thin-Walled Plates under Transverse Loading—Investigation of the Generated In-Plane Stresses. Materials 2022, 15, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Fang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Meng, S.; Nan, Z.; Xu, H.; Imtiaz, H.; Liu, B.; Gao, H. A perturbation force based approach to creasing instability in soft materials under general loading conditions. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2021, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Qiu, X.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y. A General Theory and Analytical Solutions for Post-Buckling Behaviors of Thin Sheets. J. Appl. Mech. 2022, 89, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkata, S.P.; Balbi, V.; Destrade, M.; Zurlo, G. Designing necks and wrinkles in inflated auxetic membranes. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2024, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.-K.; Li, B.; Feng, X.-Q.; Gao, H. Wrinkling–dewrinkling transitions in stretched soft spherical shells. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2024, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammane, M.; Elmhaia, O.; Mesmoudi, S.; Askour, O.; Braikat, B.; Tri, A.; Damil, N. On the use of Hermit-type WLS approximation in a high order continuation method for buckling and wrinkling analysis of von-Kàrmàn plates. Eng. Struct. 2023, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Huangfu, D.; Zhang, K.; Hu, G. Wrinkling of the membrane with square rigid elements. EPL (Europhysics Lett. 2016, 116, 24005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.-Q.; Lai, W.-J.; Huang, C.-Y.; Cai, C.-S.; Lin, C.-H.; Zhu, Q.-H. Dynamic modeling and control of rigid-flexible-thermo-electrically coupled piezoelectric integrated smart spacecraft. Appl. Math. Model. 2024, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Duan, B.; Zheng, F. Effect of the Random Error on the Radiation Characteristic of the Reflector Antenna Based on Two-Dimensional Fractal. Int. J. Antennas Propag. 2012, 2012, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Yang, Y.; Hu, G.; Zhou, Y.; Hong, J. Energy harvesting from thermally induced vibrations of antenna panels. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2022, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Lyu, S.; Ma, X.; Lin, K.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, X.; Su, G.; Li, Y.; Jin, X. Topology Design of Modular Unit and Cable Network of On-Orbit Modular-Assembled Antenna. Int. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2024, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Wang, Y.; Xu, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z.; Yu, K.; Wu, W.; Wang, M.; Leng, G.; Ge, D.; et al. Structural-Electromagnetic-Thermal Coupling Technology for Active Phased Array Antenna. Int. J. Antennas Propag. 2023, 2023, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Wei, X.; Xu, L.; Wang, C.; Lian, P.; Xue, S.; Al-Saadi, A.; Shi, Y. Multiphysics vibration FE model of piezoelectric macro fibre composite on carbon fibre composite structures. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2019, 161, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, M.; Zhong, J.; Duan, B. Compensation method for distorted planar array antennas based on structural–electromagnetic coupling and fast Fourier transform. IET Microwaves, Antennas Propag. 2018, 12, 954–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, D.; Song, L.; Zhang, X. Second-order sensitivity analysis of electromagnetic performance with respect to surface nodal displacements for reflector antennas and its benefits in integrated structural–electromagnetic optimisation. IET Microwaves, Antennas Propag. 2017, 11, 1530–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, B.A.; Afzal, M.U.; Esselle, K.P. Performance analysis of classical and phase-corrected electromagnetic band gap resonator antennas with all-dielectric superstructures. IET Microwaves, Antennas Propag. 2016, 10, 1276–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadarig, R.C.; de Cos, M.E.; Las-Heras, F. High-Performance Computational Electromagnetic Methods Applied to the Design of Patch Antenna with EBG Structure. Int. J. Antennas Propag. 2011, 2012, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, H.; Ma, X. Analysis of Structural Boundary Effects of Copper-Coated Films and Their Application to Space Antennas. Coatings 2023, 13, 1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).