1. Introduction

A growing body of work in mathematics and physics suggests that foundational structures are best understood through a

relational or

relativistic lens [

1,

2,

3]. In such a paradigm, mathematical entities acquire meaning not as intrinsic absolutes but through their role within a system defined by internal symmetries and reference frames. Constants like 0, 1, or

i are not metaphysical primitives, but relational markers—origins, units, or axes—assigned by a chosen framing.

This perspective invites a re-evaluation of one of the most entrenched assumptions in mathematics: the acceptance of actual infinity. From real analysis to Hilbert spaces, infinity has been treated as foundational, despite its lack of empirical or computational realization. Under a relational view, such constructs may instead be interpreted as emergent limits or symbolic artifacts—arising when finite systems attempt to encode relationships that exceed their internal scope.

In previous work [

4], we argued that concepts like infinity, randomness, and undecidability are not ontological features of nature, but

epistemic placeholders—signals of representational saturation in finite informational systems. Here, we extend this view into a concrete formalism: a

relativistic algebra constructed entirely over a finite field

, with observer-relative arithmetic and emergent pseudo-numbers.

The present framework resonates with several contemporary perspectives that question the ontological status of the continuum and advocate for finitely constructed alternatives. In particular, Smolin has emphasized the need for a relational, observer-dependent formulation of physical laws, suggesting that the continuum is merely an idealization beyond the reach of internal observers [

5,

6]. Similarly, D’Ariano and collaborators have reconstructed quantum theory from finite, informationally grounded axioms, demonstrating that core features of quantum mechanics can emerge without invoking infinite-dimensional Hilbert spaces [

7]. From a mathematical standpoint, the approach aligns with the ultrafinitist program developed by Benci and Di Nasso, which offers a rigorous alternative to classical cardinality through the theory of numerosities and bounded arithmetic [

8,

9].

Furthermore, the ultrafinitist school—pioneered by Yessenin-Volpin and Parikh—takes finitude even further by denying the meaningful existence of “too large” numbers and insisting on feasibility as a foundational constraint. Formalizations of ultrafinitism and feasibility arithmetic appear in works such as [

10,

11,

12,

13], which explore the proof-theoretic and computational consequences of enforcing strict constructive bounds on arithmetic.

Ultrafinitism enforces an a priori cutoff on numerical existence—only those magnitudes deemed “feasible” within a human or machine resource bound are admitted. By contrast, our relativistic framework treats finiteness not as a hard barrier but as a contextual framing condition: We allow arbitrarily large numbers, so “size” is always relative to the chosen frame. Infinite structures, such as integers and rationals emerge asymptotically or as coordinate projections, rather than being forbidden. Arithmetic operations become internal symmetries of a finite system, rather than operations constrained by external feasibility checks. This shift replaces the ultrafinitist’s absolute feasibility threshold with a relational notion of scope: any number “exists” within some finite frame, while “infinity” itself appears as a relative point beyond the horizon of observability and algebraic accessibility.

To support this framework, we further draw upon several key developments in mathematics and physics. The foundational critique of actual infinity has been explored in works such as [

14,

15], which emphasize the constructive and finitist approaches to mathematics. The relational perspective on mathematical objects aligns with category theory [

1], where objects are defined by their morphisms and relationships rather than intrinsic properties. Additionally, the parallels between relativistic mathematics and modern physics are inspired by the symmetry principles in [

2,

3], which highlight the role of invariance and frame-dependence in physical laws. Finally, the informational limits of finite systems and their implications for mathematical representation are discussed in [

16,

17].

2. Finite Field Framing

Let

be the finite field of integers modulo an odd prime

p. The elements of

form a complete and closed set of relational representations of

under modular addition, multiplication and exponentiation. However, the specific numeric labels assigned to these elements—particularly the designation of 0 and 1 as the additive and multiplicative identities—are intrinsically relative and carry no absolute meaning within the field itself. The field

is invariant under relabeling of its elements via any bijective affine transformation of the form

where

and

. Such transformations preserve the field structure and allow any element to be reinterpreted as the origin. In this sense, the element labeled 0 is not uniquely privileged; it simply represents the additive identity with respect to a chosen reference frame. The same applies to the label 1, which identifies the multiplicative unit only relative to a particular scaling.

Recall that choosing a “frame” in

consists of picking two distinguished elements

and then defining relabeled addition and multiplication by

where divisions are in the original field

.

Theorem 1 (Frame-Invariance).

Let be a finite field, and let two frames and be related by the affine bijection

Then ϕ is a ring isomorphism between and . Consequently, any polynomial identity

if and only if the “relabeled” identity

where .

Proof. Since

,

is a bijection with inverse

. For any

,

and similarly

Thus, preserves addition and multiplication, so it is a ring isomorphism. It follows immediately that any algebraic (polynomial) relation valid in one frame is carried over to the other by conjugation with , establishing frame-independence of all algebraic identities. □

Therefore, in the absence of an externally imposed or contextually declared frame—such as one defined by a designated pair —the labels in are relational rather than absolute. The roles of “zero” and “one” are thus not the fundamental properties of the elements themselves, but a consequence of the system’s framing, making all representations in symmetric and interchangeable under coordinate transformation. To define our system unambiguously, we must specify a reference frame or coordinate system within the context of , which then becomes a framed finite ring. We will henceforth assume all such systems to be framed systems and will denote the corresponding finite ring as for simplicity, unless explicitly stated otherwise.

3. Finite Field as Discrete Geometric Structure

Let

p be an odd prime and let

denote the finite field with

p elements [

18]. The additive group

is a cyclic group of order

p, and the multiplicative group of nonzero elements

is a cyclic group of order

[

19]. We associate the cardinality degree of freedom

p and the three fundamental arithmetic operations with 4 distinct symmetry classes in a symbolic geometry as in [

20]:

Counting — defines the number of elements in the ring.

Addition — defines rotational symmetry on a linear periodic axis.

Multiplication — defines scaling symmetry on a multiplicative periodic axis.

Exponentiation — defines cyclic phase-like symmetry from repeated powers of a generator [

21].

The choice of cardinality itself defines a linear—radial—degree of translation, and each cyclic operation corresponds to a spherical axis of rotational transformation in a four-dimensional abstract symmetry space. For a fixed odd prime p, the described mathematical construct forms the geometric scaffold of a discrete spheroidal system. The three spherical axes are mutually orthogonal, but algebraically dependent forming a 2D spheroid in the 4D symmetry space.

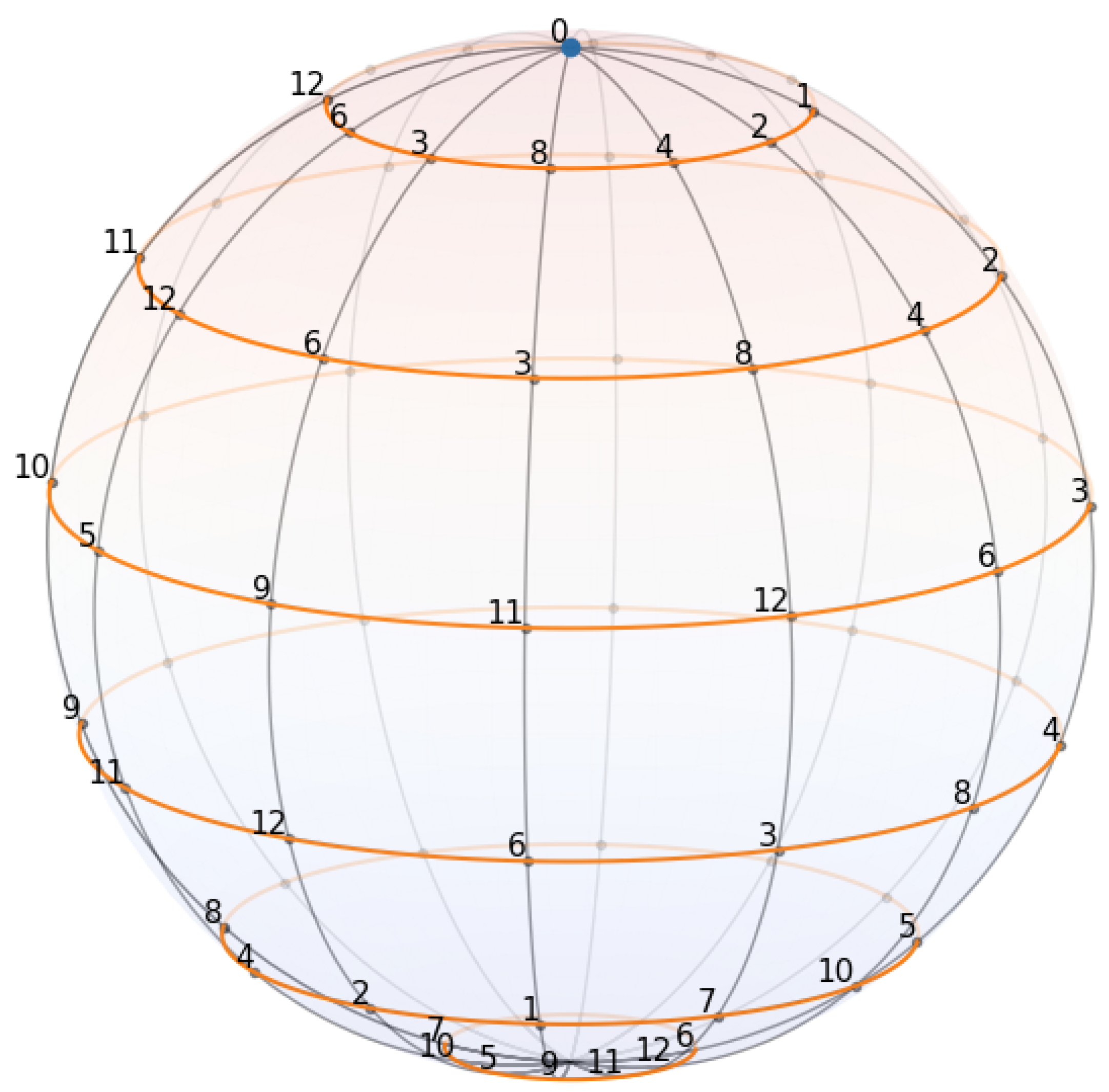

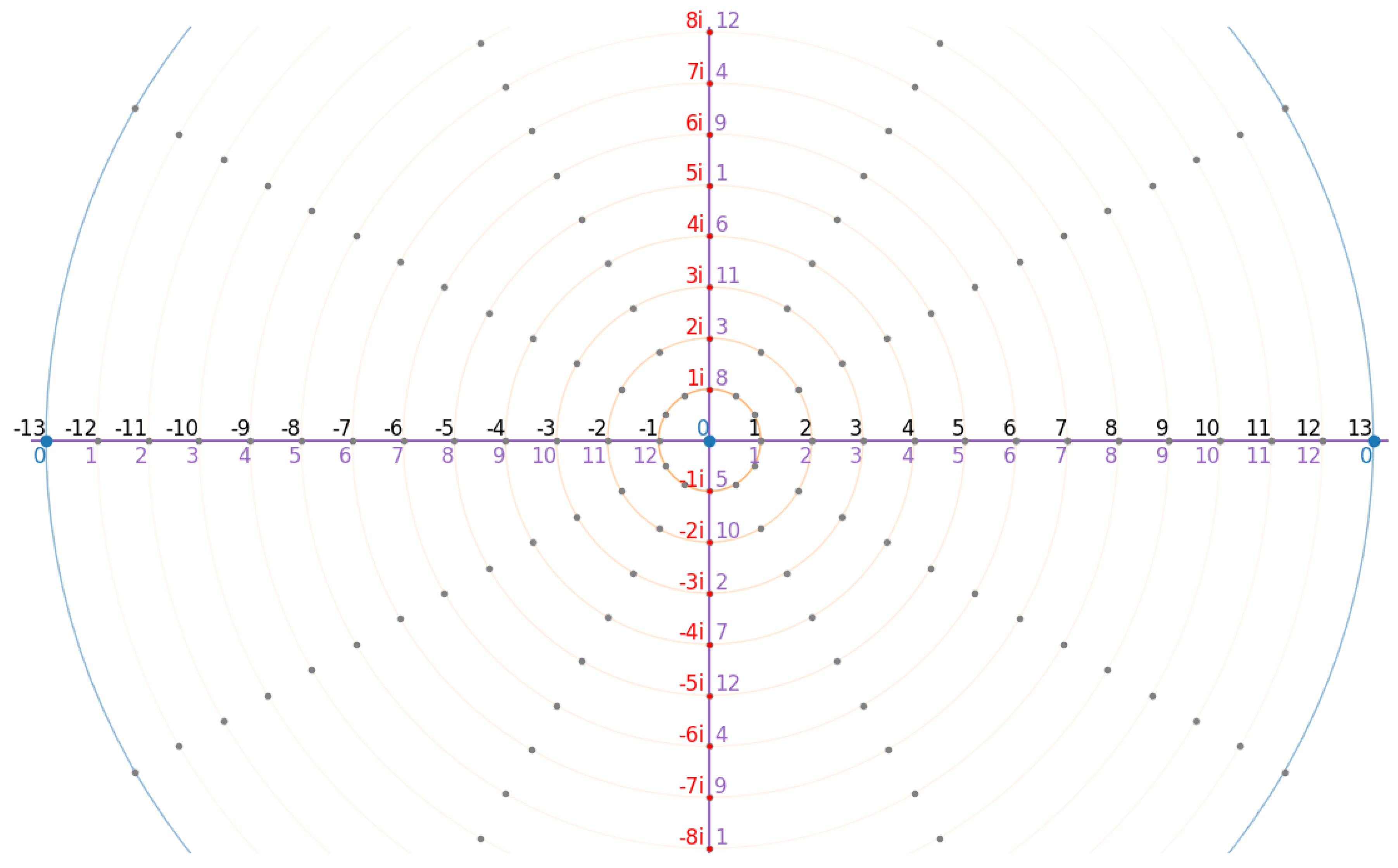

The resultant 2D spheroid for

is depicted in

Figure 1, where the prime meridian depicts the additive group

and the latitudes represent multiplicative group

generated by the minimum multiplicative generator

[

20].

4. Pseudo-Numbers

4.1. Pseudo-Integers

Define a mapping

, with

. This wraps

onto

. The observer, located at 0 and bounded by horizon

, perceives the wrapped axis as infinite. Thus, the apparent integer line emerges as a pseudo-integer class

, where negation, order, and comparison are reconstructed locally [

22].

The resulting class of relativistic pseudo-integers exhibits all the characteristic properties of the conventional integer set , including sign, order, addition, subtraction and multiplication. This framework allows us to recover the intuitive and logical structure of integers — including signed quantities and magnitude comparison — entirely within the finite, self-contained system , while preserving consistency with its modular arithmetic.

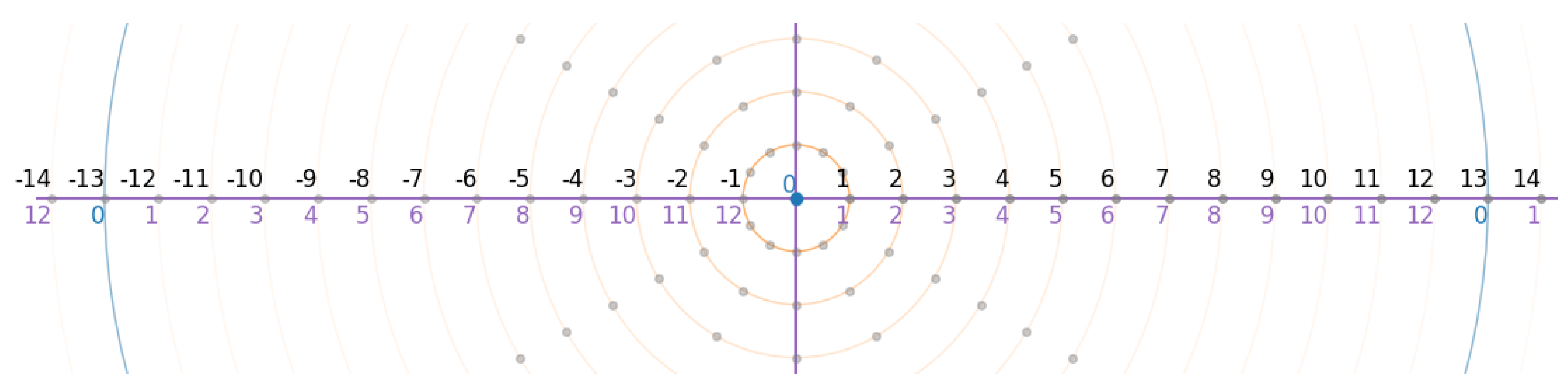

4.2. Pseudo-Rationals

The corresponding field value is

Multiple representations can map to the same

, forming equivalence classes. We show

is dense in

under a metric induced by bounded denominators

[

23]. For any

and

, there exists

such that

.

The validity of such definition is ensured by the fact that all elements

constituting the denominator product

have a multiplicative inverse

. A selection of some simple examples of such pseudo-rational numbers is depicted in

Figure 3, where for each position along the prime meridian

indicated as a black label on top, the corresponding finite field element

is indicated as purple label on the bottom.

Proposition 1.

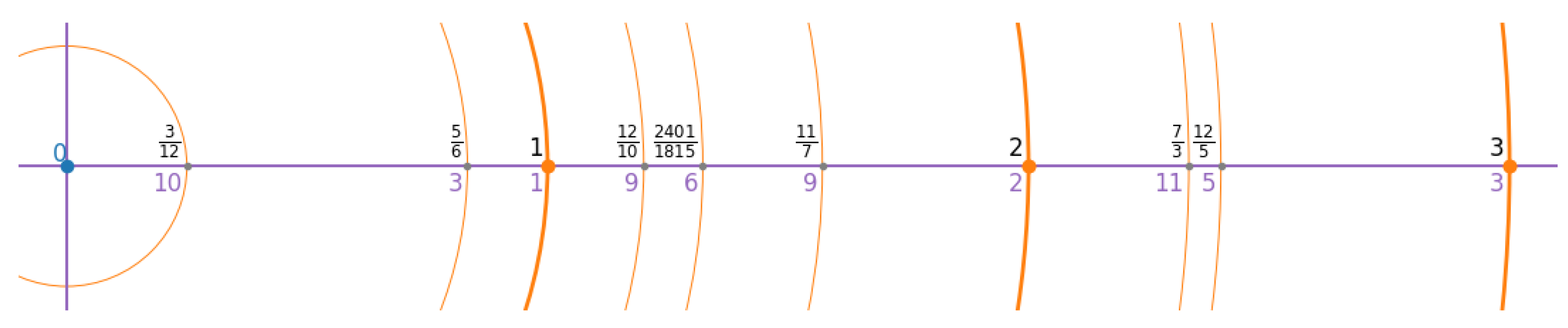

Let be an odd prime number, and let be any conventional rational number. Then for any , there exists an integer and an integer such that

Proof. Let be given, and let be arbitrary small number.

Since

p is a fixed prime, the expression

grows without bound as

. Therefore, there exists an integer

such that

Now consider the set of rational points of the form

as illustrated in

Figure 4. This set is a uniform grid of rational numbers with step size

, which is less than

by construction. There exists therefore an integer

such that

which completes the proof. □

It is very important to reiterate the meaning of this construct from an ontological viewpoint. More specifically, we stipulate that what actually “exists” are the p representations of the finite field , while the derivative class of pseudo-rationals constitute an abstract mathematical construct derived from the inherent relational properties of the framed instance .

In other words, the resultant field of pseudo-rational numbers will exhibit all the properties of the field of conventional numbers and can further approximate it with any arbitrary precision. Furthermore, for an observer with a limited observability horizon and sufficiently large values of cardinality p, the pseudo-rational field becomes completely indistinguishable from its conventional counterpart, as all the desired rational numbers of the form , where are represented not approximately, but exactly within the scope of the pseudo-rational numbers . In classical mathematics, the field of real numbers is introduced to enable the formulation of continuous functions, calculus, and metric spaces—tools indispensable for modeling physical phenomena and abstract structures alike. However, the real number line is defined as an uncountable, infinitary continuum, an ontological commitment that conflicts with the finite and relational framework we adopt in this study. Nonetheless, our need for continuous approximation and proportional reasoning persists, particularly in describing geometric constructs, dynamic systems, and analytic behaviors. Our approach is therefore pragmatic and epistemic rather than metaphysical. We seek to construct a class of pseudo-real numbers that fulfills the operational role of without invoking actual infinity.

4.3. Pseudo-Reals

Define truncated pseudo-rationals:

This set is finite and totally bounded under the metric:

Define

as the closure of

. We show all computable real numbers can be approximated within

by some element

, where

[

24].

Proposition 2 (Finite Total Boundedness). For each fixed H, the metric space is finite and thus totally bounded.

Proof. Since and , there are elements in . Any finite metric space is trivially totally bounded. □

Theorem 2 (Approximation of Computable Reals).

Let be a computable real number. For any integer there exist integers with such that

Moreover, if the observer’s horizon H satisfies

then one can construct with

In order to prove Theorem 2 we first show that every Cauchy sequence converges in . The key step is a uniform bound on the number of divisions in the Euclidean algorithm.

Lemma 1 (Euclidean-algorithm exponent bound).

Let p be a prime and suppose . If the Euclidean algorithm applied to produces k nonzero remainders before terminating, then

Proof. At each step of the Euclidean algorithm, if

are the successive remainders with

, then

and

. It is known (Lamé’s theorem) that the worst-case sequence of quotients

all equal 1, which yields the Fibonacci-type descent [

25].

so that

where

is the

n-th Fibonacci number. Since

and

for

, termination after

k steps implies

hence

. □

Proof (Proof of Theorem 2 (Completeness of

)). Let

be a Cauchy sequence with respect to the metric

where

is taken in the integer sense and we require

. By the Cauchy property, for any

there exists

N such that for all

,

Write

in lowest terms. Apply the Euclidean algorithm to each pair

to obtain the continued-fraction expansion

with

by Lemma 1. Truncating at the

J–th convergent yields a rational

satisfying the standard bound

Since

, for any chosen

we get

Thus, is a Cauchy sequence in the complete metric space , hence converges to some real limit L. By construction of as the metric completion of , this same limit L defines an element of . Therefore, every Cauchy sequence in converges in , proving completeness. □

Recall that

is defined as the metric completion of the set

equipped with the metric

Proposition 3 (Compactness of ). is a compact metric space.

Proof. We invoke the standard characterization of compactness in metric spaces [

26]:

Theorem. A metric space is compact if and only if it is complete and totally bounded.

By Theorem 2, is complete: every Cauchy sequence in converges to a point of .

Proposition 2 establishes that is totally bounded. Since is the closure (completion) of , it too is totally bounded.

Therefore, , being both complete and totally bounded, is compact. □

The resulting pseudo-real field is thus defined as the topological closure of under modular convergence. For any finite observer with bounded resolution and limited horizon of observability, is indistinguishable from the conventional real number continuum.

In conclusion, the field of pseudo-real numbers is not a metaphysical continuum but a layered epistemic utilitarian construct. It combines:

Exact pseudo-reals that satisfy algebraic equations within , and

Approximated pseudo-reals that are limits of converging sequences in .

This framework provides all the functional properties of the real numbers—continuity, density, and completeness—without invoking actual infinity. It affirms that, in a finite and informationally complete universe, continuum-like behavior is a pragmatic illusion emerging from local reasoning over a fundamentally finite arithmetic substrate. Having established the construction of pseudo-integers, rationals and reals over the finite field as relativistic, frame-dependent analogs of their classical counterparts, we seek to further extend this framework to encompass the algebraic closure of the pseudo-real field. In conventional mathematics, the introduction of complex numbers is necessitated by the absence of solutions to certain polynomial equations, such as , within the real numbers. Analogously, in the finite framed context, we are motivated to introduce complex-like elements in order to achieve closure under operations that are otherwise impossible within the pseudo-rational or alone.

Moreover, the construction of a relativistic complex plane enables the representation of rotations, oscillations, and other phenomena that are fundamental in both mathematics and physics, all within a finite and self-contained system. This approach not only mirrors the classical extension from to , but also demonstrates that the essential properties and utility of complex numbers can be realized as emergent features of a finite, relational arithmetic—thereby reinforcing our framework’s central theme of relativistic, context-dependent number systems.

5. Complex Plane over Finite Framed Field

As is commonly known, the field of real numbers does not contain any solutions of certain polynomial equations, such as the prominent equation . But that is not the case for many finite fields , where depending on the value and properties of their cardinality P, such solutions can readily exist. For example, in the finite field , the equation has two solutions: and . More generally, it is evident that the equation can be satisfied in a finite field if and only if is devisable by 4, or in other words . This is due to the fact that the multiplicative group of non-zero elements in such fields is cyclic and contains elements—and the corresponding rotational symmetry—of order 4, which allows for the existence of square roots of . In this case, we can define a special element that satisfies the equation . The element i is not unique, instead we have a pair of pseudo-integer elements i and in that satisfy the equation, in the same way as we have pairs x and of solutions for quadratic equations in the conventional complex plane .

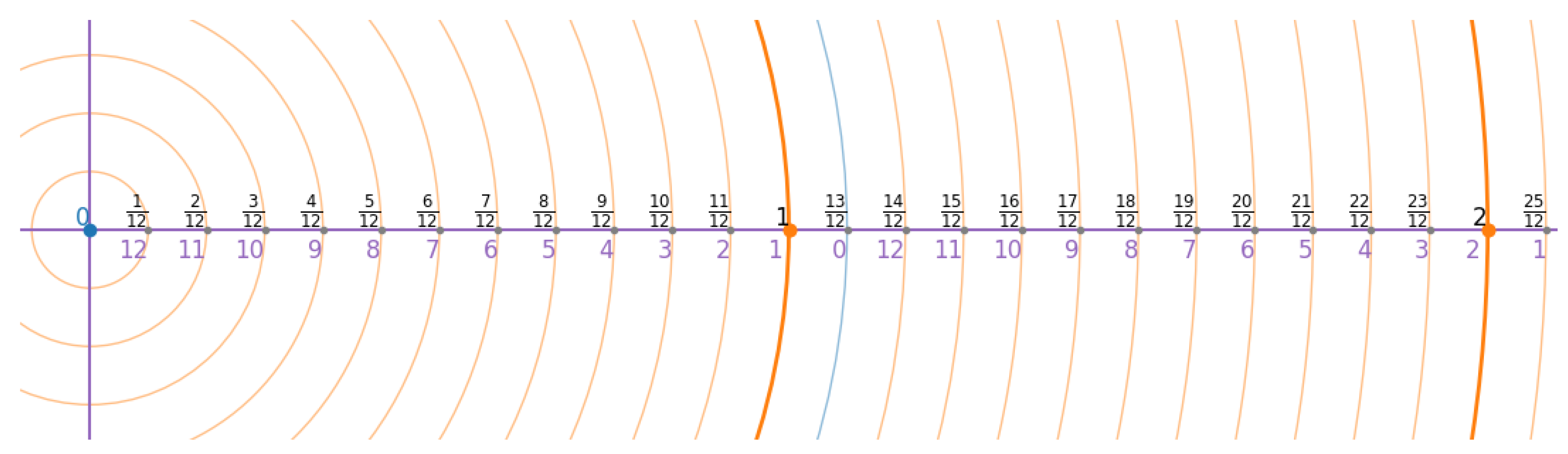

Let us now observe the “North Pole” frame of reference of the spherical representation of the finite field

with its prime meridian of pseudo-reals

forming the horizontal axis around the origin. The order-4 rotational symmetry of the finite field

can be represented as a vertical axis of imaginary numbers

, where

, that are perpendicular to the prime meridian, as illustrated in

Figure 5. The imaginary numbers

c are represented by their respective red labels, while the corresponding elements

are depicted in purple.

More generally, we can define a class of pseudo-complex numbers

as the Cartesian product of the pseudo-reals

and the imaginary numbers

. The pseudo-complex numbers are defined as follows:

where

a and

b are the real and imaginary components of the pseudo-complex number

c, respectively. The pseudo-complex numbers can be represented as points in the complex plane, where the horizontal axis corresponds to the pseudo-reals

and the vertical axis corresponds to the imaginary numbers

. The pseudo-complex numbers form a field and can be added, subtracted, multiplied, and divided in a manner analogous to conventional complex numbers, with the additional consideration of their finite field properties.

The pseudo-complex numbers form a relativistic algebraic field and can be added, subtracted, multiplied, and divided in a manner analogous to conventional complex numbers, subject to the selection of the arbitrary frame of reference, as well as the properties and constraints of the underlying finite field.

6. Unification and Ontological Perspective

We assert that only the

p representations of

truly exist. All pseudo-number classes are epistemic constructs derived from relational symmetries and observer framing. The observer’s bounded horizon

induces the illusion of infinite domains [

27].

6.1. Infinity as the Unknowable “Far-Far Away”

Let us revisit the ontological concept of

infinity as described in [

4]. In the previous sections, we have established the finite framed field

as an abstract pseudo-sphere

with a limited-horizon observer at its origin 0. We would like now to consider the geometric point on our pseudo-sphere that is the furthest away from the observer. This point is evidently the

South Pole—the antipodal point on the prime meridian—of the pseudo-sphere, which we will denote as

for now. We would like to emphasize the following important properties of

.

is a unique point on the pseudo-sphere that is the farthest away from the observer at 0.

is invisible to the observer at 0, that is to say that is located beyond any conceivable definition of the observer’s limited observability horizon.

Finally, is algebraically inaccessible to the observer at 0, in the sense that , and cannot be reached by any finite number of arithmetical steps along the surface of the pseudo-sphere.

We would like to provide a formal proof of the less evident Property 3 as follows.

Theorem 3 (No South Pole in

).

Let be an odd prime. Then the only solution to

is . Equivalently, there is no nonzero pseudo-rational whose image in has additive order 2.

Proof.

Since

p is prime, the additive group

is cyclic of order

p. An element

has order 2 precisely if

Because , multiplication by 2 is invertible in . Hence, from it follows immediately that . There is no nontrivial order-2 element.

By definition, each pseudo-rational

is represented in the field by

so

under the embedding

k. If some

mapped to a nonzero order-2 element

, then

would force

, a contradiction.

Therefore, no “South Pole” antipodal point exists in or , completing the proof. □

These properties of the geometrical point are unmistakably consistent with the properties of the concept of infinity in its conventional sense. This gives us the justification to identify the relativistic antipodal point with the concept of infinity in the context of , and thus denote it as ∞.

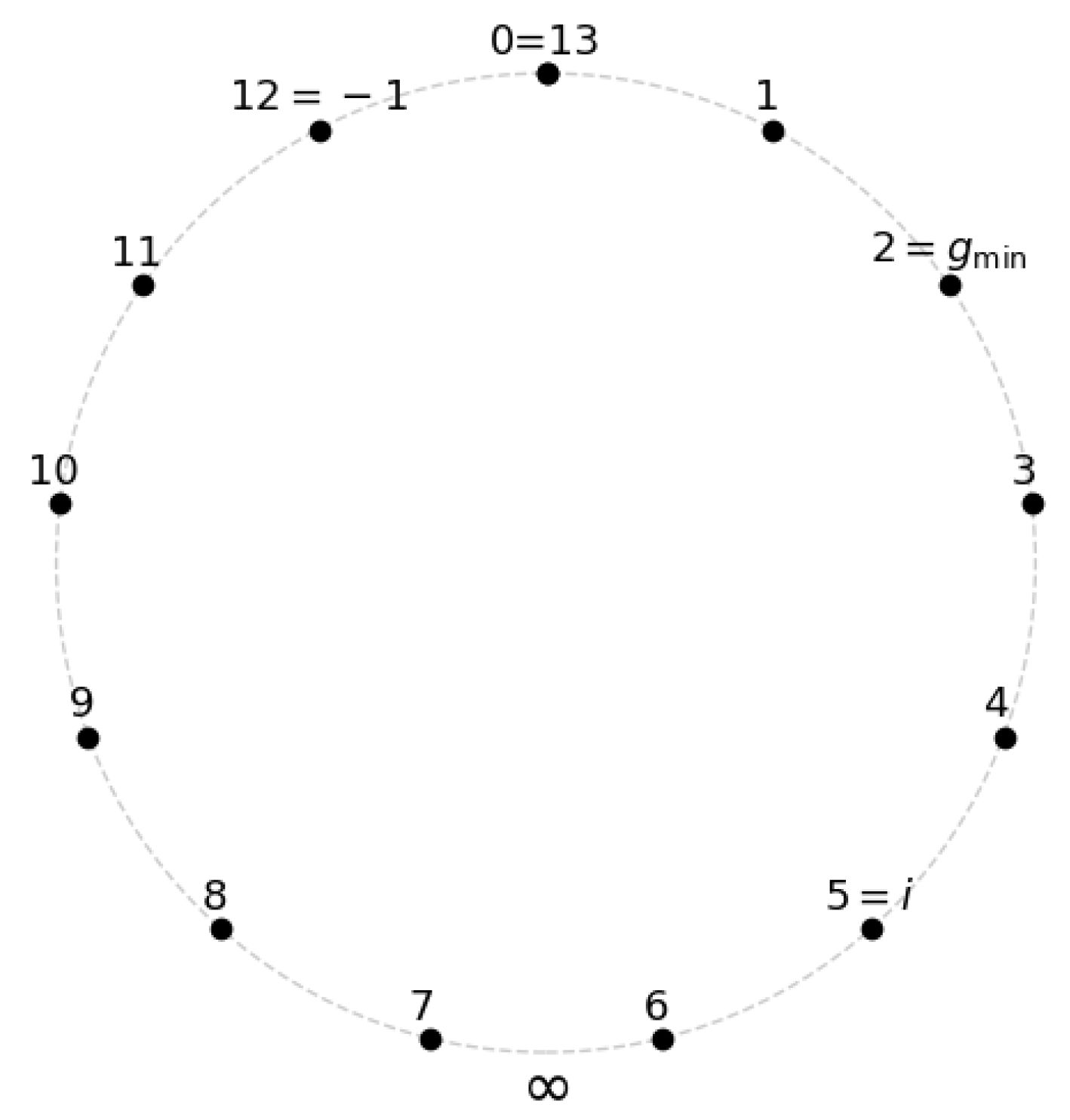

To exemplify, let us now consider the concrete example of

and the corresponding finite framed field

. We can identify the following values for the constants

i,

e and

in

:

The corresponding visual representation of the finite field

is shown in

Figure 6. The figure shows the state space of the finite field

as a circle on a 2D plane, with the major structural elements

, as well as

∞ indicated. The antipodal point

∞ is located at the South Pole of the pseudo-sphere, which is the farthest point from the observer at 0.

7. Unification over Finite Fields

7.1. Approximate Lie Groups

Continuous Lie groups such as

,

, and

are approximated in

by discrete symmetry groups generated by modular exponentiation and cyclic subgroup structures [

28].

Let

be a multiplicative cyclic group of order

. The mapping:

approximates continuous rotation

by discrete steps. Similarly, discrete matrix groups over

, such as

, replicate local algebraic behavior of Lie algebras over reals. These finite analogs converge to their continuous counterparts as

and preserve closure, invertibility, and group action properties locally within observer horizons

as follows.

Let

p be a prime with

, and fix a primitive root

g of

. Set

, and identify the cyclic subgroup

with the “discretized” circle via the map

Proposition 4 (Angle-approximation error).

For every , defining , one has

Proof. By construction,

, so

Thus, using the chord-arc bound

,

□

Proposition 5 (Group-law error).

For any , let and set . Then

Proof. We have

where the “round-off” exponent

satisfies

Hence, and is a multiple of with . Setting yields the claimed estimates. The final bound follows by combining from Prop. 4 with . □

7.2. Finite Langlands Program

In the usual Langlands philosophy one relates two vast worlds: on the one hand the (infinite) Galois representations of a global field, and on the other the automorphic representations of a reductive group over that field [

29,

30]. If one accepts that

only finite rings

can exist, then every “infinite” Galois group must be replaced by its finite quotient

and every automorphic representation must likewise factor through a finite group of points

for some level

. In this “finite-Langlands” perspective all objects—Galois data and automorphic forms—are

built from the same finite base ring

, and the conjectural correspondence becomes a bijection between

From the function-field side one already has a prototype: Drinfeld and Lafforgue proved a global Langlands correspondence for

over

, where

is a finite field, and automorphic forms live on

[

31,

32]. There, both Galois representations and automorphic sheaves are

intrinsically finite objects—perverse sheaves on moduli stacks over

and

ℓ-adic representations of

. This suggests that a genuinely finite-universe version of the Langlands program would reorganise every classical component (Hecke operators,

L-functions, trace formulas) into purely combinatorial operations on

-modules and finite group characters.

In summary, if one accepts that is the only ontologically primitive object, then the Langlands correspondence reduces to an equivalence of categories between -linear Galois modules and -linear automorphic modules. All “infinite” phenomena (analytic continuation, spectral decompositions) become emergent from the finiteness of through limiting processes within finite-dimensional -vector spaces. Such a viewpoint collapses the traditional dichotomy and recasts Langlands duality as a statement about different frames of reference on a single finite ring.

8. Conclusion

This work reconstructs arithmetic over finite fields as a complete, self-consistent relativistic algebra. Number systems conventionally built on actual infinity are shown to emerge from finite, observer-relative structures in . This reformulation provides a robust mathematical language for finite informational systems and supports a shift from absolute to structural foundations in mathematics, mathematics and formal logic.

References

- Lane, S.M. Categories for the Working Mathematician; Springer, 1998.

- Einstein, A. On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies. Annalen der Physik 1905, 17, 891–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noether, E. Invariante Variationsprobleme. Nachrichten von der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen, Mathematisch-Physikalische Klasse.

- Akhtman, Y. Existence, Complexity and Truth in a Finite Universe. Preprint 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Smolin, L. Time Reborn: From the Crisis in Physics to the Future of the Universe; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013.

- Smolin, L. The Trouble with Physics: The Rise of String Theory, the Fall of a Science, and What Comes Next; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2006.

- D’Ariano, G.M. Physics Without Physics: The Power of Information-Theoretical Principles. International Journal of Theoretical Physics 2017, 56, 97–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benci, V.; Nasso, M.D. Numerosities of Labelled Sets: A New Way of Counting. Advances in Mathematics 2003, 173, 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benci, V.; Nasso, M.D. A Theory of Ultrafinitism. Notre Dame Journal of Formal Logic 2011, 52, 229–247. [Google Scholar]

- Yessenin-Volpin, A.S. The Ultra-Intuitionistic Criticism and the Antitraditional Program for Foundations of Mathematics. Proceedings of the International Congress of Mathematicians.

- Parikh, R.J. Existence and Feasibility in Arithmetic. Journal of Symbolic Logic 1971, 36, 494–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sazonov, V.Y. On Feasible Numbers. Logic and Computational Complexity.

- Avron, A. The Semantics and Proof Theory of Linear Logic. Theoretical Computer Science 2001, 294, 3–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, L.E.J. On the Foundations of Mathematics; Springer, 1927.

- Weyl, H. Philosophy of Mathematics and Natural Science; Princeton University Press, 1949.

- Chaitin, G. Thinking about Gödel and Turing: Essays on Complexity, 1970-2007. World Scientific 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, S. Ultimate Physical Limits to Computation; Nature, 2000.

- Burton, D.M. Elementary Number Theory, 7th ed.; McGraw-Hill, 2010.

- Dummit, D.S.; Foote, R.M. Abstract Algebra, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, 2004.

- Akhtman, Y. Canonical Frame of Reference on Symbolic Spheroids in Finite Fields of Prime Cardinality. Preprint 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Artin, M. Algebra, 2nd ed.; Pearson, 2011.

- Knuth, D.E. The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 1: Fundamental Algorithms, 3rd ed.; Addison-Wesley, 1997.

- Serre, J.P. Local Fields; Vol. 67, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, Springer: New York, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Turing, A.M. On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem. Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society 1936, 42, 230–265. [Google Scholar]

- Lamé, G. Mémoire sur la résolution des équations numériques. Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Sciences 1844, 19, 867–872. [Google Scholar]

- Rudin, W. Principles of Mathematical Analysis, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Barwise, J.; Perry, J. Situations and Attitudes; MIT Press, 1985.

- Hall, B.C. Lie Groups, Lie Algebras, and Representations: An Elementary Introduction, 2nd ed.; Vol. 222, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, Springer, 2015.

- Langlands, R.P. Problems in the Theory of Automorphic Forms; Springer-Verlag, 1970.

- Borel, A. Automorphic Forms on Reductive Groups; Springer-Verlag, 1979.

- Drinfeld, V.G. Elliptic modules. Mathematics of the USSR-Sbornik 1974, 23, 561–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafforgue, L. Chtoucas de Drinfeld et correspondance de Langlands. Inventiones mathematicae 2002, 147, 1–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).