The genes for microtubule associated protein tau (circTau) and TADBP (circTARDBP) generate 107 and 73 circular RNAs

Most of the circular RNAs from MAPT and TARDBP are human-specific

CircTau and circTARDBP contain 28 and 17 circRNA-specific exon

CircTau RNA can express proteins that might contribute to disease

1. Pre-mRNAs Generate a Large Number of Circular RNAs in Addition to mRNAs

1.1. Circular RNAs Largely Increase Transcript Diversity

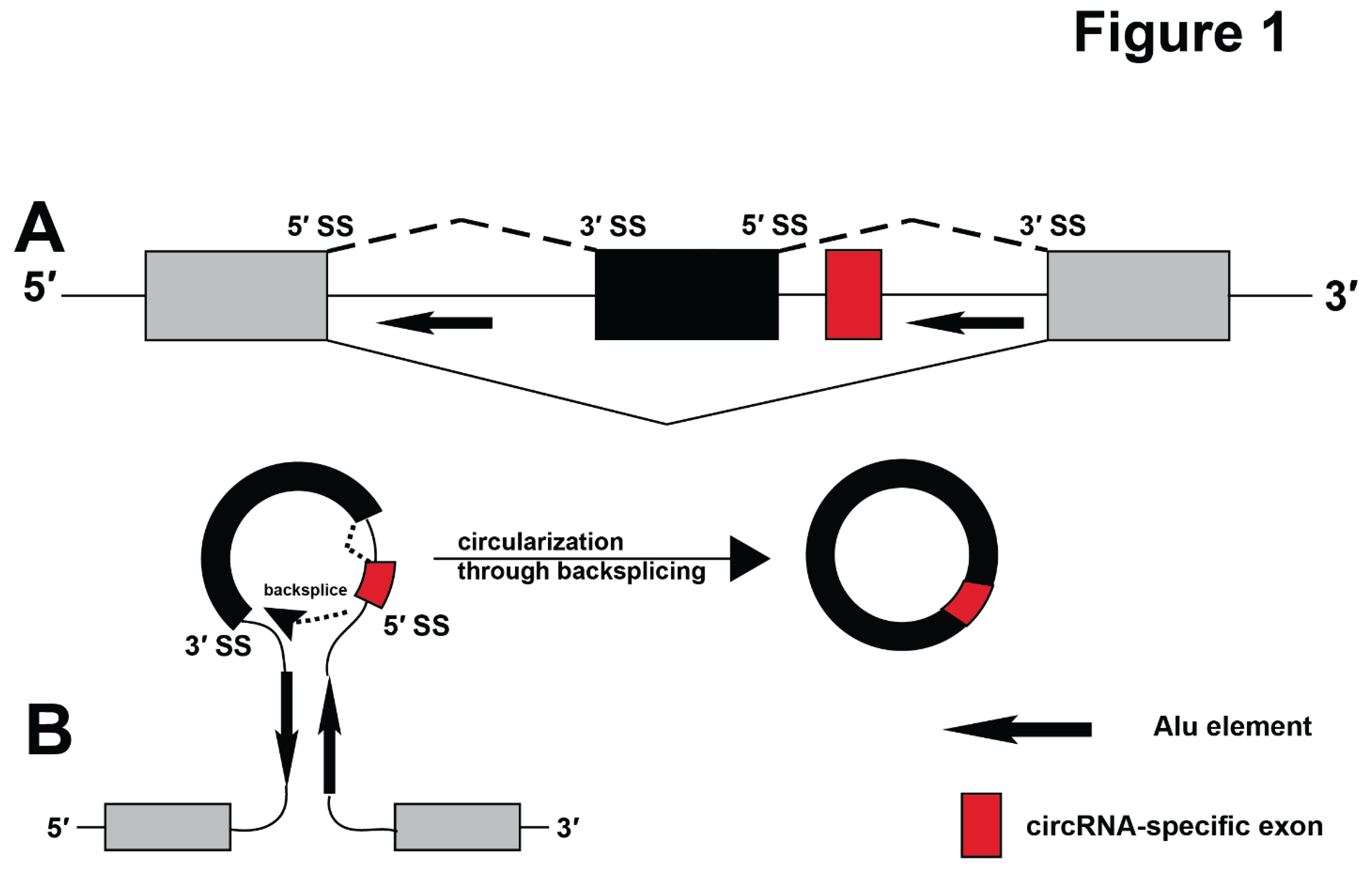

Almost all human genes undergo pre-mRNA splicing that removes introns by connecting a 5’ splice site of an exon to an downstream 3’ splice site, which generates mRNAs (

Figure 1A). Exons can be alternatively used, allowing humans to use 22,180 genes (Lee and Rio 2015) to generate an estimated 320,000 mRNA isoforms (Mudge, Carbonell-Sala et al. 2025).

Figure 1.

Pre-mRNA splicing and backsplicing. A. Pre-mRNA splicing leading to mRNA formation. An alternative exon (black) is indicated, arrows depict Alu elements. A red box indicates an exon that is only present in circular RNAs. B. Circular RNA generation. Pre-mRNA structures imposed by base-pairing between complementary repetitive elements, such as Alu elements (arrows, dots) bring putative backsplice sites in close vicinity leading to circularization.

Figure 1.

Pre-mRNA splicing and backsplicing. A. Pre-mRNA splicing leading to mRNA formation. An alternative exon (black) is indicated, arrows depict Alu elements. A red box indicates an exon that is only present in circular RNAs. B. Circular RNA generation. Pre-mRNA structures imposed by base-pairing between complementary repetitive elements, such as Alu elements (arrows, dots) bring putative backsplice sites in close vicinity leading to circularization.

In addition to mRNAs, pre-mRNAs can generate circular RNAs (circRNAs). CircRNAs are covalently closed RNAs that are found in all kingdoms of life (Wang, Bao et al. 2014, Patop, Wust et al. 2019, He, Xu et al. 2023). In humans, most circRNAs are generated through backsplicing (Yang, Wilusz et al. 2022), i.e. the connection of a 5’ splice site with an upstream 3’ splice site, which creates a backsplice junction (

BSJ) (

Figure 1B). CircRNAs are cytosolic, and highly expressed in brain, where they are enriched in synaptosomes (Hanan, Soreq et al. 2017, Akhter 2018, Meng, Zhou et al. 2019, Mehta, Dempsey et al. 2020). The expression levels of 14 circRNAs were associated with Braak stages and explained 31% of the clinical dementia rating, compared to 5% of the APOE4 alleles (Dube, Del-Aguila et al. 2019). Although circRNAs have been discovered more than 34 years ago (Nigro, Cho et al. 1991), only recent advances in next generation sequencing showed their abundant expression (Jeck, Sorrentino et al. 2013). The collection of human circRNAs in databases indicate that there are more than 1.8 million circRNA isoforms in humans, which is more than the currently estimated 320,000 mRNA isoforms annotated in Genecode (Mudge, Carbonell-Sala et al. 2025). Previous studies showed that 3.2% of the circRNAs contain specific exons, i.e. exons that occur only in circRNAs and 5.3% of circRNAs contain novel splicing patterns (Rahimi, Veno et al. 2021).

A recently released circRNA database, FL-circAS, identified 884,636 backsplice junctions in 1,853,692 full-length circRNA isoforms in humans. From these 1.8 million circRNAs, 195,802 isoforms were supported by at least five long reads identified in one full-length circRNA isoform. The recent sequencing efforts extended the large number of novel, circRNA-specific exons. Compared with the linear transcripts in the current genome annotations (Ensembl annotation version 113), 2,259,591 circRNA splice sites did not match any annotated exon boundaries and 397,438 circRNA exons did not overlap with any annotated exons, i.e. are specific for circRNAs. More than 12% (51,503) of the 397,438 circRNA-specific exons were supported by at least five long reads. Thus, although they show much lower expression levels than mRNAs, circRNAs strongly increase the readout of the human genome.

1.2. Circular RNA Biogenesis Is Influenced by Alu Elements

circRNAs can be generated by a number of mechanisms, including tRNA splicing (Noto, Schmidt et al. 2017), group I (Puttaraju and Been 1992) and group II intron splicing (Murray, Mikheeva et al. 2001) and through lariat formation (Barrett, Wang et al. 2015). In humans almost all circRNAs are generated through backsplicing mechanism (

Figure 1B). This pathway contrasts the generation of mRNAs, where a 5’ splice site is connected to the downstream 3’ splice site. In general, splice sites leading to circular RNA formation are thousands of nucleotides apart. The correct backsplice site can be brought into close vicinity necessary for splicing by two major mechanisms: pre-mRNA structures and bridging by hnRNPs. Pre-mRNA structures can be imposed by complementary regions in the mRNAs that are usually introduced by repetitive elements in intronic sequences. In humans, these structures are often imposed by Alu elements (

Figure 1B) (Jeck, Sorrentino et al. 2013).

Alu elements are primate-specific retrotransposons (Batzer, Deininger et al. 1996, Batzer and Deininger 2002, Deininger 2011, Chen and Yang 2017) that are about 300 nt in length and compose 10.7% of human DNA, making the presence of Alu-elements the major difference between humans and non-primate genomes. Alu elements originated from the non-coding 7SLRNA and expanded through primate evolution. Alu elements can lead to exon formation but are mainly found in intergenic and intronic regions.

Due to their sequence similarity, Alu elements can form double-stranded regions when inserted into pre-mRNAs and could thus generate a defined, primate-specific structure, especially when they are arranged in opposite orientation. The existence of these pre-mRNA structures is supported by RNA in situ conformation sequencing showing that Alu elements promote more than 37% of all RNA-RNA interactions across enhancers (Liang, Cao et al. 2023). It is thus likely that Alu elements could similarly promote backsplicing, which could explain the association of human backsplice sites with Alu-elements (Jeck, Sorrentino et al. 2013).

Alu elements are a major substrate for ADAR enzymes (Adenosine deaminase acting on RNA), that catalyze the conversion of adenosines to inosines (Bazak, Haviv et al. 2014). Almost all human Alu elements are modified by ADAR activity, making Alu-elements the preferred substrate of ADAR enzymes in humans (Bazak, Levanon et al. 2014). Likely reflecting the acquisition of novel Alu-elements, there is more A>I editing in humans than in other primate species like chimpanzee or rhesus, which is most apparent in genes expressed in brain (Paz-Yaacov, Levanon et al. 2010). In contrast to primates, the related rodent-specific B1 elements are much less frequently modified (Neeman, Levanon et al. 2006).

A second general mechanism that aligns backsplice sites is mediated by protein interaction where hnRNPs bind to regions flanking the backsplice sites and facilitate circularization. More than 15 RNA-binding proteins were shown to promote circRNA formation, among them QKI (Conn, Pillman et al. 2015), RBM20 (Khan, Reckman et al. 2016), hnRNP L (Fei, Chen et al. 2017), FUS (Ashwal-Fluss, Meyer et al. 2014), NF90/NF110 (Li, Liu et al. 2017), and muscleblind protein (MBL)(Ashwal-Fluss, Meyer et al. 2014), (reviewed in (Huang, Zheng et al. 2020)). Conversely, the helicase DHX9 unwinds Alu-element mediated structures and reduces circRNA expression (Aktas, Avsar Ilik et al. 2017). The recognition sites of most hnRNPs have been experimentally determined and their mapping based on bioinformatic predictions to sites flanking the backsplice sites are available in databases (Chiang, Jhong et al. 2024).

2. CircRNA Are Metabolically Stable and Undergo Base Modifications

CircRNAs are metabolically stable with half-lives of over 20 hours (Enuka, Lauriola et al. 2016), allowing them to accumulate RNA modifications. The best understood modifications are m6A modification (N6-methyl adenosine) present in 13% of circRNAs (Fan, Yang et al. 2022) and adenosine deamination leading to inosine formation. The m6A modification is catalyzed by an enzyme complex of Mettl3/Mettl14. Mettl3 (Methyltransferase 3) is the catalytic subunit and Mettl14 (Methyltransferase 14) positions the catalytic subunit near the 5'- [G/A/U][G>A]m6AC[U>A/C]-3' sequence that contains the adenosine to be modified. It is possible that similar to tRNAs and other stable RNAs, more RNA modifications exist in circRNAs.

Due to intramolecular base pairing, circRNAs form rod like structures with extended double stranded RNA sequences (Sanger, Klotz et al. 1976), and are thus prone to undergo modifications by ADAR enzymes that recognize these double stranded RNA structures and convert adenosines into inosines (A>I editing) (Samuel 2019). Humans express three ADAR enzymes: ADAR1 expressed in all tissues with an induced cytosolic (p150) and a constitutive nuclear (p110) isoform; ADAR2 showing weak expression in brain; and the catalytic inactive ADAR3 showing strong expression in brain. The induction of ADAR1-p150 is caused by cytokines, especially interferon alpha and gamma (George, Gan et al. 2011). Interferon stimulated genes are highly upregulated in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Roy, Wang et al. 2020), correlating with a two-fold increase of interferon alpha in AD brains (Taylor, Minter et al. 2014). The cytosolic ADAR1-p150 stimulates A>I modification of circTau12->7 RNA 3-10-fold stronger than the nuclear ADAR1-p110 or the related ADAR2 (Welden, Margvelani et al. 2022), suggesting that circRNA modification can take place in the cytosol. Mapping of the circTau RNA A>I editing sites showed that they are influenced by the flanking Alu elements (Welden, Margvelani et al. 2022), suggesting that the intronic sequencing context influences the modification of circular RNAs. ADAR1 mRNA is unchanged in AD (Ma, Dammer et al. 2021) and there is a reduction of ADAR2 and an increase of ADAR3 (Ma, Dammer et al. 2021) in AD. However, the activity of ADAR enzymes is regulated by post-translational modifications that include SUNOlation and phosphorylation (Vesely and Jantsch 2021). Only five editing sites in mRNA-UTRs were associated with AD (Ma, Dammer et al. 2021), but the editing of Alu elements in AD has not been determined.

3. Emerging Functions of circRNA

Despite their frequent occurrence, the function of most circRNAs is not clear. CircRNAs could act by interacting with other RNAs and proteins and/or by being translation templates to generate proteins.

3.1. Interaction with miRNAs

Binding to miRNAs was the first function identified for circRNAs. It was found that the unusually abundant circRNA ciRS-7/CDR1as (HUGO name LINC00632) binds to miR-7. ciRS-7/CDR1 mediated sequestration of miR-7, called ‘sponging’, repressed miR-7 action (Hansen, Jensen et al. 2013). This interaction is physiologically relevant, and ciRS-7/CDR1as was identified as a part of a network of non-coding RNAs that likely controls spatial and temporal miR-7 availability in neurons, which regulates synaptic transmission (Piwecka, Glazar et al. 2017). Numerous interactions between circRNAs and miRNAs have been reported and were validated in cellular assays. However, often the amount of circRNA is low compared to the miRNA, which questions the physiological relevance (Memczak, Jens et al. 2013, Hsiao, Sun et al. 2017, Panda 2018, Jarlstad Olesen and L 2021).

3.2. circRNAs as Templates for Translation

Most circRNAs contain open reading frames (ORF). Since circRNAs are lacking a 5′ tri-methyl guanosine cap, they need to use cap-independent translational mechanisms. Following the first description of internal ribosomal entry sites (Chen and Sarnow 1995, Chen, Cheng et al. 2021), the modification of adenosines to N6-methyl adenosines (m6A) was shown to promote circRNA translation. m6A binds to its reader YTHDF3, which recruits the 40S rRNA through interaction with eIF4G and eIF3 (Yang, Fan et al. 2017, Di Timoteo, Dattilo et al. 2020). Since only an estimated 13% of circRNAs contain m6A modifications (Fan, Yang et al. 2022), it is likely that other translational mechanisms exist.

A second mechanism to translate circRNA depends on proteins deposited on the splice sites during circRNA formation. circRNAs generated by backsplicing contain at least one splice-site junction. This and other splice junctions can bind to an exon-junction complex that contains eIF4A3, which can recruit the 40S rRNA through eIF3 mediated interaction, leading to eIF4A3-dependent translation, that was found for some circRNAs (Chang, Shin et al. 2023, Lin, Chang et al. 2023, Xiong, Liu et al. 2023). A third recently discovered mechanism uses adenosine to inosine (A>I) RNA modifications that strongly promote translation of circtau RNAs (Welden, Margvelani et al. 2022, Arizaca Maquera, Welden et al. 2023). The modification-dependent translation of circRNAs has been mainly studied in cancer and more than 30 circRNA encoded proteins confirmed by mass-spectroscopy have been reported (Margvelani, Maquera et al. 2024). In addition, mass-spectrometry identified over 1,600 backsplice junction-peptides in pachytene spermatocytes (Tang, Xie et al. 2020), a developmental stage where the expression of mRNAs is strongly reduced. In general, circRNA translation occurs under conditions that favor cap-independent translation, like hypoxia, viral infection, and heat shock.

Here, we summarize circular RNAs from the MAPT and TARDP genes and their possible contributions to brain pathologies.

4. Microtubule Associated Protein tau (MAPT)

4.1. MAPT and Human Disease

The neuropathologic hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (AD neuropathologic changes, or ADNC) are intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) and amyloid plaques (Alzheimer 1911). Of these two microscopic lesions, particularly strong associations have been described between NFTs and cognition (Williams 2006, Delacourte 2008, Abisambra and Scheff 2014). The molecular and ultrastructural makeup of NFTs have also been well characterized with the protein Tau at the core of the fibrillar, insoluble, and protease-resistant material that seems to extrude and causes death of some of the cells that harbor them. Further, many other diseases in addition to ADNC (collectively referred to as “tauopathies”) are characterized by Tau pathology. Excellent prior reviews have been written on tauopathies (Williams 2006, Takashima 2008, Spillantini and Goedert 2013). These diseases span a broad range of pathogenetic paradigms including developmental, age-related degenerative, traumatic, inflammatory, neoplastic, and combinatorial mechanisms, many of which are only incompletely understood (Chornenkyy, Fardo et al. 2019). A critical insight is that some mutations of the MAPT gene itself lead to frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD-MAPT) (Baker, Kwok et al. 1997, Hutton, Lendon et al. 1998, Goedert, Ghetti et al. 2000, Cairns, Bigio et al. 2007) and thus the gene/protein itself can drive dementia. What is also clear is that in the course of tauopathic diseases, common disease-driving pathologic cascades are downstream of many different primary causes, while clinical symptoms are referent to the anatomic location of the Tau pathology, rather than to the upstream antecedents (Chornenkyy, Fardo et al. 2019).

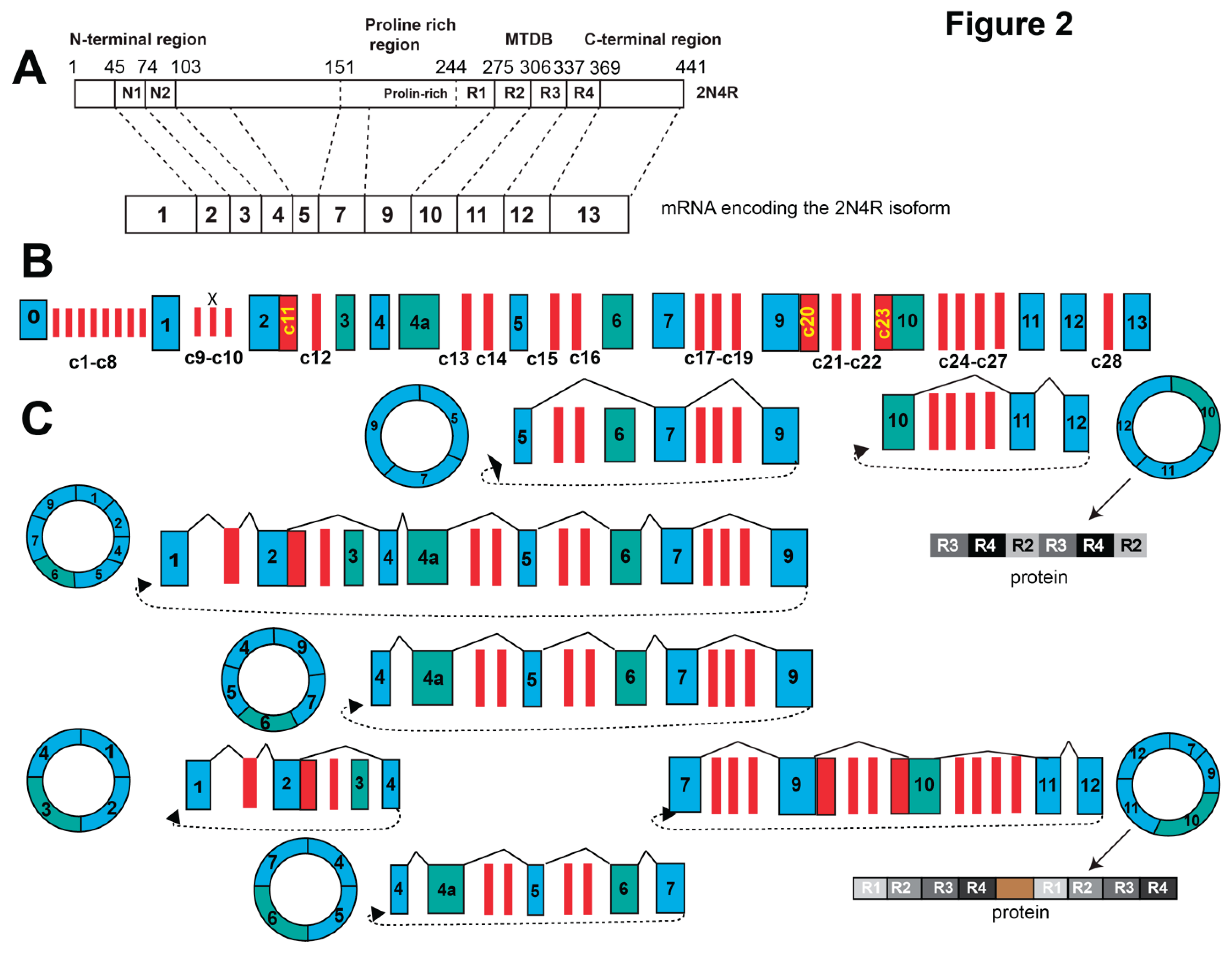

4.2. Structure of the Human MAPT Gene

The human MAPT gene spans 133,781 nt and is located on chromosome 17. The human gene contains at least 16 exons, around half of which are alternatively spliced (

Figure 2A), which generates a multitude of mRNA isoforms. The MAPT locus contains three internal transcripts: STH (saitohin), the MAPT intronic transcript 1, and a gene for Metazoan Signal Recognition Particle RNA. In addition, the gene locus generates an antisense transcript that partially overlaps with the MAPT pre-mRNA in intron 1.

Two major haplotypes of MAPT exist, with the more common H1 haplotype overrepresented in subjects with progressive supranuclear palsy. The haplotype was first discovered using polymorphic markers in intron 9 (Conrad, Amano et al. 1998) and later shown to include the whole MAPT locus (Baker, Litvan et al. 1999), including a 238 nt deletion in intron 9.

The protein encoded by the resulting MAPT mRNAs contains an N-terminal region, a proline-rich region, the microtubule binding domain (MTBD) and a C-terminal domain. This composition is changed by alternative splicing of the MAPT-pre-mRNA (

Figure 2A).

Exons 2 and 3 encode part of the N-terminal projection domain and exon 10 encodes the second microtubule binding domain. Alternative splicing of exon 2, 3 and 10 generates six major tau isoforms, termed 4R (including exon 10), and 3R (skipping exon 10) and 0, 1, 2 N containing 0-2 N terminal domains. (

Figure 2). Other isoforms contain exon 4a (‘big tau 4a+’) or stop at exon 6 and thus lack the microtubule binding sites. The isoforms have been extensively reviewed (Andreadis 2005, Corsi, Bombieri et al. 2022, Buchholz and Zempel 2024).

The human MAPT gene contains several repetitive elements that could influence the pre-mRNA structure. Notably, MAPT contains at least 83 Alu elements, with 56 on the sense strand and 27 on the antisense strand. In addition, there are CpG islands in intron 1 and internal CpG islands upstream of exon 4A and within exon 9 and 13 that could possibly interact and contribute to pre-mRNA structures (Caillet-Boudin, Buee et al. 2015).

4.3. MAPT Circular RNA Isoforms

The MAPT gene generates numerous circular RNAs. Analysis of 67 libraries (33 human and 34 mouse from various cells and tissues) using full-length circRNA sequencing approaches identified 75 backsplice junction sites (

BJSs), giving rise to 107 circMAPT isoforms. 69 of the observed 75 BSJs are found only in humans and only six BSJs are conserved between mouse and human indicating species-specific expression (

Table 1,

Figure 2).

Compared to other circRNAs, circMAPT isoforms are low abundant: the most frequent isoform circTau 7-4 has 56 reads, compared to 273987 reads of CDR1-AS9 (LINC00632) that represents the highest expressed circRNA.

RT-PCR analysis identified further circMAPT isoforms that were not annotated in the most recent database, indicating that more circMAPT isoforms could exist. These isoforms were generated by backsplicing from exon 12 to either exon 10 or exon 7. The expression of these circTau RNAs was validated by RNase protection analysis using radioactive probes against the backsplice sites, demonstrating the existence of these circRNAs (Welden, van Doorn et al. 2018, Welden, Margvelani et al. 2022). The pre-mRNA region involved in their formation contains 47/53 of the FTLD- MAPT (previously FTDP-17) mutations (Margvelani, Welden et al. 2024) and the 238 nt deletion in intron 9 that is characteristic for the H2 MAPT haplotype (Baker, Litvan et al. 1999). There was no detectable association between and circTau 12->10 expression and Braak stages (Welden, van Doorn et al. 2018).

The location of the circRNA indicates the genome coordinated of the flanking exons in Hg38. Exons and splicing pattern indicate the literature numbers of the exons. ORF and m6A indicated that presence of predicted ORFs and m6A sites. Reads indicate the number of reads from the CIRI-long and isoCirc libraries.

In total, there are 28 novel exons found only in circTau -RNAs that are listed in

Supplemental Table S1. The exons are cassette exons that are characterized by suboptimal length and being flanked by very weak splice sites. Three circRNA-specific exons C10, C23 and C27 are flanked by AT-AC intron and C5 contains a gc-5’ splice site. Thus, these circRNA-specific exons are very weak, which explains why they are not included in the MAPT-mRNA. Exon C16, C24, partially overlap with one and, C19, C21, C28 partially overlap with two Alu-elements, showing that circRNA can contribute to the exonization of Alu elements. The presence of partial Alu-elements in these circRNAs-exons can possibly promote their A>I editing and translation.

4.4. Translation of circTau RNAs

The circTau 12->7 and 12->10 circRNAs are 681 and 288 nt long and harbor open reading frames without stop codons. CircTau 12->7 is 681 nt long and contains one start codon. circTau 12->10 is 288 long and lacks a start codon. Since 681 and 288 can be divided by three, repeated rolling circle translation will lead to repeats of the MAPT-protein regions in an indefinite ORF (iORF), which was confirmed using transfection assays of reporter genes in HEK293 cells (Welden, Margvelani et al. 2022). Importantly, under normal transfection conditions, these circRNAs are hardly translated. However, when their RNA editing is induced using transfection of ADAR1 or ADAR2 expression constructs, strong translation is observed. The circTau 12->10 RNA lacks a start codon, but two FTLD- MAPT (previously FTDP-17), K317M (Zarranz, Ferrer et al. 2005) and V337M (Spina, Schonhaut et al. 2017) located in exons 11 and 12 introduce start codons and lead to translation (Welden, Margvelani et al. 2022). Unexpectedly, even in the absence of these mutation, editing of the circTau 12->10 RNA causes translation, likely by changing an AUA to AUI codon through editing, which was supported by mutational analysis (Welden, Margvelani et al. 2022). In vitro studies using reporter cells suggest that translated circTau proteins promote aggregation of mRNA-encoded tau proteins (Welden, Margvelani et al. 2022). Circtau 12->7 encoded proteins bind to eIF4B, a translational initiation factor that does not bind to mRNA-encoded tau proteins. Since the circTau 12->7 encoded proteins is identical to C-terminal of the mRNA encoded protein, it is not clear why circTau 12->7 encoded proteins have such a specific interaction (Margvelani, Welden et al. 2024).

The pre-mRNA regions involved in circTau 12->7 formation harbor 47/53 of the FTLD-MAPT mutations and the 238 nt deletion in intron 9 that defines the MAPT haplotypes. The FTDP-17 mutations allowed to determine the influence of point mutations on circRNA translation. For most mutations the amount of circRNA does not correlate with the amount of protein formed, which underlines that circRNA translation depends on RNA modifications. Some mutations, like I260V, L266V, G303V, K317M and V337M promote circRNA formation and three mutations P301S, S305N and V367I promote translation of the circTau 12->7 RNAs (Margvelani, Welden et al. 2024). It is thus possible that in general, the amount of circRNAs does not correlate with the amount of proteins formed.

Collectively, these data suggest that circTau encoded proteins could contribute to tauopathies and that some FTLD-MAPT mutations could act through circTau RNAs. However, at this stage, the analysis of circTau encoded proteins is limited to in vitro systems and the physiological roles needs further confirmations.

5. TARDBP

5.1. TARDP and Human Disease

The gene name TARDBP stands for TAR DNA Binding Protein, TAR abbreviates transactivation response RNA structure. Whereas there is relatively longstanding appreciation that many different conditions are associated with Tau pathology (Delacourte 2008, Abisambra and Scheff 2014), the study of TDP-43 proteinopathic conditions (TDPopathies) is a younger area of research. TDP-43 proteinopathy was discovered as a pathologic marker in 2006 in the context of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal lobar degeneration with TDP-43 inclusions (FTLD-TDP) (Neumann, Sampathu et al. 2006). Interestingly, some of the paradigms associated with tauopathic disease also seem to apply to TDP-43 proteinopathies, including the tendency of specific genetic modifiers (Ramanan and Saykin 2013, Jain and Chen-Plotkin 2018) to apparently increase the proteinopathy that was caused by different primary upstream causes. Indeed, the mutation of TARDBP by itself can cause neurological disease including dementia (Sreedharan, Blair et al. 2008, Van Deerlin, Leverenz et al. 2008, Gitcho, Bigio et al. 2009).

Further, along with the relatively well-known diseases with TDP-43 proteinopathy (ALS and FTLD-TDP), other TDPopathies include Alexander disease (Walker, Daniels et al. 2014), Perry syndrome (Mishima, Koga et al. 2017), Cockayne syndrome (Sakurai, Makioka et al. 2013), neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (Haraguchi, Terada et al. 2011), inclusion body myositis (Weihl, Temiz et al. 2008), Huntington’s disease (Davidson, Amin et al. 2009) and other conditions. However, by far the most common TDPopathy condition is termed limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE) and its defining substrate that is recognized at autopsy, LATE neuropathologic changes (LATE-NC) (Nelson, Dickson et al. 2019). LATE-NC affects ~1/3rd of individuals beyond age 85 and is strongly associated with cognitive impairment (Nelson, Abner et al. 2010, Nelson, Brayne et al. 2022, Nag and Schneider 2023). In LATE-NC and other TDPopathies, as in tauopathies, the affected protein becomes hyperphosphorylated and fibrillar, with toxic gains of function and also deleterious loss-of-normal-functional changes (Gao, Wang et al. 2018, Nelson, Schneider et al. 2023). However, the pathogenetic mechanisms underlying TDPopathies are only beginning to be understood.

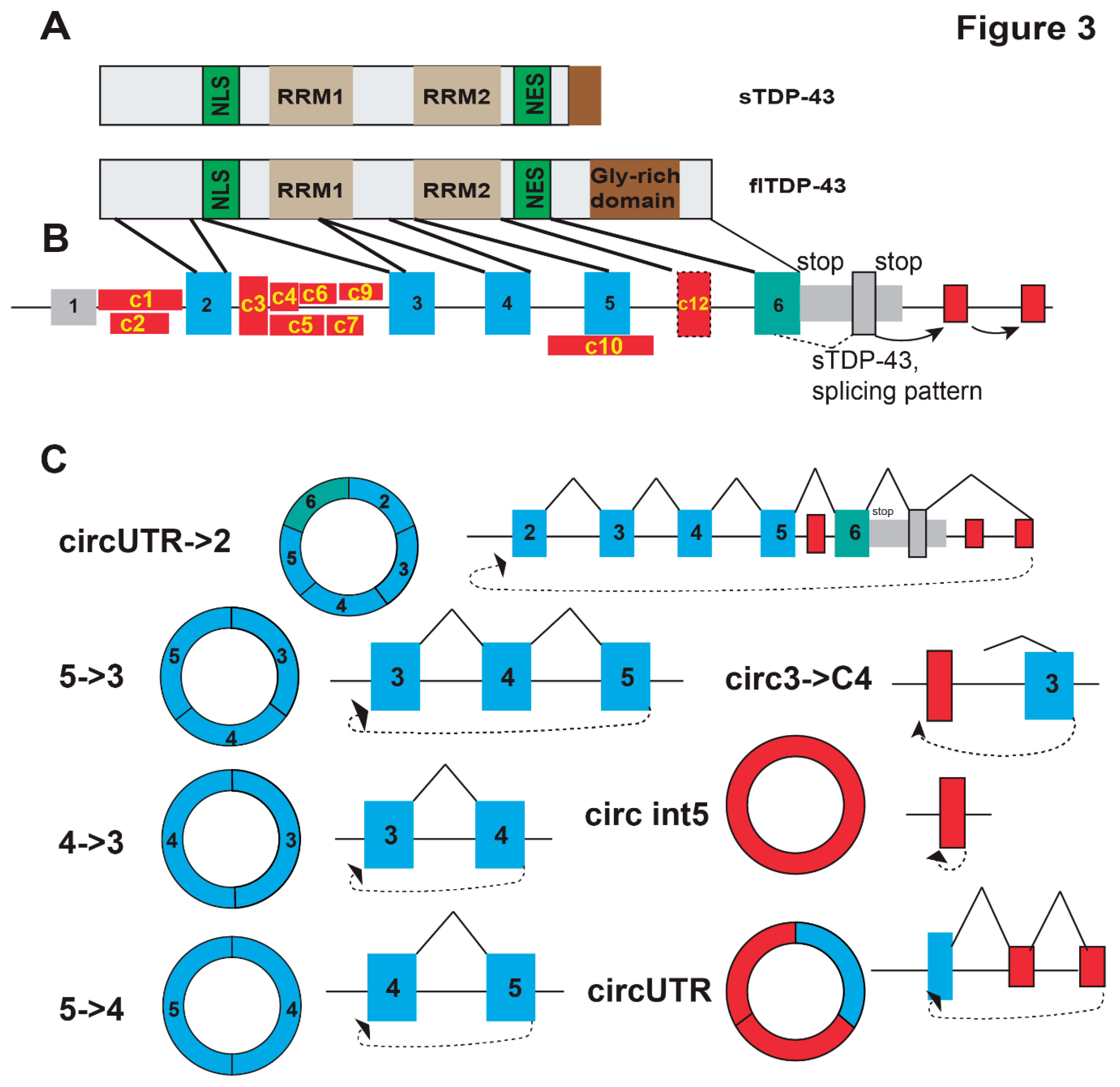

5.2. Structure of the TARDBP Gene

The TDP-43 gene spans 12.9 kb on chromosome 1 and contains six exons that create the major full-length flTDP-43 isoform which encodes a mainly nuclear protein (

Figure 3A,B). The flTDP-43 protein binds to UG-rich RNA sequences (Tollervey, Curk et al. 2011). At high cellular concentrations, the flTDP-43 protein binds to its own pre-mRNA and causes usage of an alternative splice site within exon 6 that connects an exon in the UTR, which due to alternative splicing in the UTR generates new 3’ ends (Wang, Wang et al. 2004, Weskamp, Tank et al. 2020, Shenouda, Xiao et al. 2022). The resulting mRNAs encode shorter sTDP-43 proteins that contain a C-terminal nuclear export sequence and are predominantly cytosolic (Weskamp, Tank et al. 2020). In total at least six sTDP-43 protein isoforms with slightly different C-termini are generated (Shenouda, Xiao et al. 2022). sTDP-43 is subject to nonsense-mediated decay and proteasomal degradation. sTDP-43 can heterodimerize with flTDP-43, which inhibits the nuclear splicing activity of flTDP-43 (Dykstra, Weskamp et al. 2025). Overexpression of sTDP-43 leads to neuronal death, suggesting that disruption of this autoregulation could lead to disease (Dykstra, Weskamp et al. 2025). TDP-43 represses the transcription of genes rich in Alu elements, preferring Alu S elements, which are the most frequent Alu subclass in humans (Morera, Ahmed et al. 2019).

5.3. circRNAs Formed by the TARDBP Gene

Visual inspection of the human TARDBP gene using the UCSF genome browser showed that the TDP-43 gene contains 18 Alu-elements. In humans, the pre-mRNA contains 60 backsplice junctions which generate 73 circTARDBP isoforms. Surprisingly no circTARDBP-RNAs have been detected in mice brain, suggesting that the TARDBP gene generates potentially human-specific circRNAs in brain. Mice use 16 BSJs generating 16 circRNA isoforms in other tissues. Several of the human circRNAs contain ORFs, but their translation has not been confirmed. Highly expressed TARDBP circRNAs supported by more than 5 reads that are present in at least two libraries are summarized in

Table 2.

The location of the circRNA indicates the genome coordinated of the flanking exons in Hg38. Exons and splicing pattern indicate the literature numbers of the exons. ORF and m6A indicated that presence of predicted ORFs and m6A sites. Reads indicate the number of reads from the CIRI-long and isoCirc libraries.

The circRNAs of the human TARDBP gene use at least 12 novel exons that have not been detected in mRNAs or ESTs. Eight of these novel exons partially overlap with human Alu-elements. Most of the novel circRNA exons are in intron 2 that contains seven Alu elements. Intron 2 expresses three circRNA-specific cassette exons that can utilize four internal splice sites, which generates at least seven circRNA-specific exons from intron 2. The circTARDBP-specific exons are flanked by weak splice site, including one AT-AC intron and atypical gg and ct at the 5’ splice site. It remains to be determined whether the atypical nucleotides are recognized via backsplicing or through another mechanism.

Although the human specific circTARDBP exons and circTARDBP RNAs are the major difference between mouse and human their physiological relevance remains to be determined.

6. Discussion

6.1. circRNAs Increase Significantly the Read-Out of the Genetic Information Stored in the MAPT and TARDBP Genes

Most of the circRNAs from the MAPT and TARDBP are human-specific and contain so far unknown exons. The circRNA-specific exons are flanked by very weak and often atypical splice sites and have a suboptimal length (mean length 315 nt, median: 243). The dependency of backsplicing on pre-mRNA structure likely allows the usage of suboptimal exons. 5/28 of the MAPT and 8/12 TARDBP circRNA-specific exons overlap with Alu-elements, suggesting the exonization of Alu elements is frequent in circRNAs. Since Alu-elements are the major target for A>I RNA editing, which promotes circRNA translation, the presence of these exons could lead to translation of some circRNAs from the MAPT and TARDBP genes. Recent studies showed that some of the translated circTau proteins promote aggregation of the mRNA-encoded tau protein in vitro. It is thus possible that translated circRNAs from the MAPT and TARDBP gene could contribute to AD or LATE.

6.2. circRNAs Often Encoded Misfolded Proteins that Are Prone to Aggregation

The analysis of experimentally validated circRNA-encoded proteins shows that they are often misfolded and adopt to new binding proteins (Margvelani, Maquera et al. 2024). For example, circtau 12->7 encoded proteins bind to eIF4B (eukaryotic initiation factor 4B). EIF4B does not interact with the mRNA encoded tau protein(Margvelani, Welden et al. 2024). Overall, the A>I editing of circular RNAs increases during AD progression in entorhinal cortex (Arizaca Maquera, Welden et al. 2023), suggesting that some circRNAs will be translated, generating novel proteins.

6.3. Do circTau and circTARDBP-Encoded Proteins Contribute to Pathologic Synergy?

The accumulation of one species of disease-associated misfolded protein can affect cellular processes and ultimately trigger misfolding of different proteins in the same cells (Trojanowski and Lee 2000, Hardy 2006, Irwin, Lee et al. 2013, Nelson, Trojanowski et al. 2016, Spires-Jones, Attems et al. 2017, Nelson, Abner et al. 2018), a process termed “pathologic synergy” (Nelson, Abner et al. 2018). Tau and TDP-43 proteinopathies appear to have the potential for pathologic synergy. The possibility of pathologic synergy is illustrated by brain conditions with Tau pathologies that often demonstrate comorbid TDP-43 pathology. These diseases include argyrophilic grain disease (Arnold, Dugger et al. 2013), Huntington’s disease (Davidson, Amin et al. 2009), anti-IgLON5 tauopathy (Cagnin, Mariotto et al. 2017), corticobasal degeneration (CBD) and progressive nuclear palsy (PSP) (Yokota, Davidson et al. 2010, Kouri, Oshima et al. 2013, Kertesz, Finger et al. 2015). Several studies have demonstrated co-localization of Tau and TDP-43 pathologic aggregates in the same cells (Nelson, Abner et al. 2018). For example confocal microscopy and double-label immunostaining against TDP-43 and Tau showed that TDP-43 and Tau-positive NFT co-localize in amygdala in AD patients (Higashi, Iseki et al. 2007) and a study of 247 subjects found that a subset of cells with colocalized hippocampal Tau/TDP-43 pathology was seen in advanced ADNC (Smith, Bachstetter et al. 2018)

Since circRNAs from the MAPT and TARDBP genes could encode misfolded proteins that are formed during AD progression they could contribute to pathological synergy and should be included in molecular studies of AD and LATE.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Naghme Bagheri and Giorgi Marvelani Conceptualization and Writing of first draft; Tai-Wei Chiang and Trees-Juen Chuang: bioinformatic analysis and data minining; Peter T Nelson: writing the medical background information; Stefan Stamm: writing, review and final editing.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Science Foundation [MCB-2221921]; NIH [1R21AG087332-01 to S.S., P30 AG072946, R01 NS118584, RF1 AG082339 to PTN, and National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan (NSTC 112-2311-B-001-023-MY3) to TJC.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not require ethical approval as it did not involve human or animal subjects.

Informed Consent Statement

During the preparation of this work the author(s) used Microsoft Copilot in order to improve the language and readability. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

backsplice junctions (BSJs); Adenosine deaminase acting on RNA ADAR; Alzheimer’s disease (AD); open reading frames (ORF); transactivation response RNA structure (TAR); circular RNA (circRNA); AD neuropathologic changes (ADNC)

References

- Abisambra, J.F.; Scheff, S. Brain Injury in the Context of Tauopathies. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2014, 40, 495–518. [CrossRef]

- Akhter, R. (2018). "Circular RNA and Alzheimer's Disease." Adv Exp Med Biol 1087: 239-243.

- Aktas, T.; Avsar Ilik, I.; Maticzka, D.; Bhardwaj, V.; Pessoa Rodrigues, C.; Mittler, G.; Manke, T.; Backofen, R.; Akhtar, A. DHX9 suppresses RNA processing defects originating from the Alu invasion of the human genome. Nature 2017, 544, 115–119. [CrossRef]

- Alzheimer, A. (1911). "Über eigenartige Krankheitsfälle des späten Alters." Z Gesamte Neurol Psychiatr(4): 356–385.

- Andreadis, A. Tau gene alternative splicing: expression patterns, regulation and modulation of function in normal brain and neurodegenerative diseases. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Basis Dis. 2005, 1739, 91–103. [CrossRef]

- Maquera, K.A.A.; Welden, J.R.; Margvelani, G.; Sardón, S.C.M.; Hart, S.; Robil, N.; Hernandez, A.G.; de la Grange, P.; Nelson, P.T.; Stamm, S. Alzheimer’s disease pathogenetic progression is associated with changes in regulated retained introns and editing of circular RNAs. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2023, in press.

- Maquera, K.A.A.; Welden, J.R.; Margvelani, G.; Sardón, S.C.M.; Hart, S.; Robil, N.; Hernandez, A.G.; de la Grange, P.; Nelson, P.T.; Stamm, S. Alzheimer’s disease pathogenetic progression is associated with changes in regulated retained introns and editing of circular RNAs. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2023, 16, 1141079. [CrossRef]

- Arnold, S.J.; Dugger, B.N.; Beach, T.G. TDP-43 deposition in prospectively followed, cognitively normal elderly individuals: correlation with argyrophilic grains but not other concomitant pathologies. Acta Neuropathol. 2013, 126, 51–57. [CrossRef]

- Ashwal-Fluss, R.; Meyer, M.; Pamudurti, N.R.; Ivanov, A.; Bartok, O.; Hanan, M.; Evantal, N.; Memczak, S.; Rajewsky, N.; Kadener, S. circRNA Biogenesis Competes with Pre-mRNA Splicing. Mol. Cell 2014, 56, 55–66. [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.; Kwok, J.B.J.; Kucera, S.; Crook, R.; Farrer, M.; Houlden, H.; Isaacs, A.; Lincoln, S.; Onstead, L.; Hardy, J.; et al. Localization of frontotemporal dementia with parkinsonism in an Australian kindred to chromosome 17q21–22. Ann. Neurol. 1997, 42, 794–798. [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.; Litvan, I.; Houlden, H.; Adamson, J.; Dickson, D.; Perez-Tur, J.; Hardy, J.; Lynch, T.; Bigio, E.; Hutton, M. Association of an Extended Haplotype in the Tau Gene with Progressive Supranuclear Palsy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1999, 8, 711–715. [CrossRef]

- Barrett, S.P.; Wang, P.L.; Salzman, J.; States, U. Circular RNA biogenesis can proceed through an exon-containing lariat precursor. eLife 2015, 4, e07540. [CrossRef]

- Batzer, M.A.; Deininger, P.L. Alu repeats and human genomic diversity. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2002, 3, 370–379. [CrossRef]

- Batzer, M.A.; Deininger, P.L.; Hellmann-Blumberg, U.; Jurka, J.; Labuda, D.; Rubin, C.M.; Schmid, C.W.; Ziętkiewicz, E.; Zuckerkandl, E. Standardized nomenclature for Alu repeats. J. Mol. Evol. 1996, 42, 3–6. [CrossRef]

- Bazak, L., A. Haviv, M. Barak, J. Jacob-Hirsch, P. Deng, R. Zhang, F. J. Isaacs, G. Rechavi, J. B. Li, E. Eisenberg and E. Y. Levanon (2014). "A-to-I RNA editing occurs at over a hundred million genomic sites, located in a majority of human genes." Genome Res 24(3): 365-376.

- Bazak, L.; Levanon, E.Y.; Eisenberg, E. Genome-wide analysis of Alu editability. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 6876–6884. [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, S.; Zempel, H. The six brain-specific TAU isoforms and their role in Alzheimer's disease and related neurodegenerative dementia syndromes. Alzheimer's Dement. 2024, 20, 3606–3628. [CrossRef]

- Cagnin, A.; Mariotto, S.; Fiorini, M.; Gaule, M.; Bonetto, N.; Tagliapietra, M.; Buratti, E.; Zanusso, G.; Ferrari, S.; Monaco, S. Microglial and Neuronal TDP-43 Pathology in Anti-IgLON5-Related Tauopathy. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2017, 59, 13–20. [CrossRef]

- Caillet-Boudin, M. L., L. Buee, N. Sergeant and B. Lefebvre (2015). "Regulation of human MAPT gene expression." Mol Neurodegener 10: 28.

- Cairns, N. J., E. H. Bigio, I. R. Mackenzie, M. Neumann, V. M. Lee, K. J. Hatanpaa, C. L. White, 3rd, J. A. Schneider, L. T. Grinberg, G. Halliday, C. Duyckaerts, J. S. Lowe, I. E. Holm, M. Tolnay, K. Okamoto, H. Yokoo, S. Murayama, J. Woulfe, D. G. Munoz, D. W. Dickson, P. G. Ince, J. Q. Trojanowski, D. M. Mann and D. Consortium for Frontotemporal Lobar (2007). "Neuropathologic diagnostic and nosologic criteria for frontotemporal lobar degeneration: consensus of the Consortium for Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration." Acta Neuropathol 114(1): 5-22.

- Chang, J.; Shin, M.-K.; Park, J.; Hwang, H.J.; Locker, N.; Ahn, J.; Kim, D.; Baek, D.; Park, Y.; Lee, Y.; et al. An interaction between eIF4A3 and eIF3g drives the internal initiation of translation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, 10950–10969. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-K.; Cheng, R.; Demeter, J.; Chen, J.; Weingarten-Gabbay, S.; Jiang, L.; Snyder, M.P.; Weissman, J.S.; Segal, E.; Jackson, P.K.; et al. Structured elements drive extensive circular RNA translation. Mol. Cell 2021, 81, 4300–4318.e13. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-Y.; Sarnow, P. Initiation of Protein Synthesis by the Eukaryotic Translational Apparatus on Circular RNAs. Science 1995, 268, 415–417. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L. L. and L. Yang (2017). "ALUternative Regulation for Gene Expression." Trends Cell Biol 27(7): 480-490.

- Chiang, T.-W.; Jhong, S.-E.; Chen, Y.-C.; Chen, C.-Y.; Wu, W.-S.; Chuang, T.-J. FL-circAS: an integrative resource and analysis for full-length sequences and alternative splicing of circular RNAs with nanopore sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 52, D115–D123. [CrossRef]

- Chornenkyy, Y.; Fardo, D.W.; Nelson, P.T. Tau and TDP-43 proteinopathies: kindred pathologic cascades and genetic pleiotropy. Mod. Pathol. 2019, 99, 993–1007. [CrossRef]

- Conn, S.J.; Pillman, K.A.; Toubia, J.; Conn, V.M.; Salmanidis, M.; Phillips, C.A.; Roslan, S.; Schreiber, A.W.; Gregory, P.A.; Goodall, G.J. The RNA Binding Protein Quaking Regulates Formation of circRNAs. Cell 2015, 160, 1125–1134. [CrossRef]

- Conrad, C.; Amano, N.; Andreadis, A.; Xia, Y.; Namekataf, K.; Oyama, F.; Ikeda, K.; Wakabayashi, K.; Takahashi, H.; Thal, L.J.; et al. Differences in a dinucleotide repeat polymorphism in the tau gene between Caucasian and Japanese populations: implication for progressive supranuclear palsy. Neurosci. Lett. 1998, 250, 135–137. [CrossRef]

- Corsi, A.; Bombieri, C.; Valenti, M.T.; Romanelli, M.G. Tau Isoforms: Gaining Insight into MAPT Alternative Splicing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15383. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, Y.; Amin, H.; Kelley, T.; Shi, J.; Tian, J.; Kumaran, R.; Lashley, T.; Lees, A.J.; Duplessis, D.; Neary, D.; et al. TDP-43 in ubiquitinated inclusions in the inferior olives in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and in other neurodegenerative diseases: a degenerative process distinct from normal ageing. Acta Neuropathol. 2009, 118, 359–369. [CrossRef]

- Deininger, P.L. Alu elements: know the SINEs. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, 236. [CrossRef]

- Delacourte, A. Tau Pathology and Neurodegeneration: An Obvious but Misunderstood Link. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2008, 14, 437–440. [CrossRef]

- Di Timoteo, G.; Dattilo, D.; Centrón-Broco, A.; Colantoni, A.; Guarnacci, M.; Rossi, F.; Incarnato, D.; Oliviero, S.; Fatica, A.; Morlando, M.; et al. Modulation of circRNA Metabolism by m6A Modification. Cell Rep. 2020, 31, 107641. [CrossRef]

- Dube, U.; Del-Aguila, J.L.; Li, Z.; Budde, J.P.; Jiang, S.; Hsu, S.; Ibanez, L.; Fernandez, M.V.; Farias, F.; Norton, J.; et al. An atlas of cortical circular RNA expression in Alzheimer disease brains demonstrates clinical and pathological associations. Nat. Neurosci. 2019, 22, 1903–1912. [CrossRef]

- Dykstra, M.M.; Weskamp, K.; Gómez, N.B.; Waksmacki, J.; Tank, E.; Glineburg, M.R.; Snyder, A.; Pinarbasi, E.; Bekier, M.; Li, X.; et al. TDP43 autoregulation gives rise to dominant negative isoforms that are tightly controlled by transcriptional and post-translational mechanisms. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 115113–115113. [CrossRef]

- Enuka, Y.; Lauriola, M.; Feldman, M.E.; Sas-Chen, A.; Ulitsky, I.; Yarden, Y. Circular RNAs are long-lived and display only minimal early alterations in response to a growth factor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 44, 1370–1383. [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Yang, Y.; Chen, C.; Wang, Z. Pervasive translation of circular RNAs driven by short IRES-like elements. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Fei, T.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, T.; Li, W.; Cato, L.; Zhang, P.; Cotter, M.B.; Bowden, M.; Lis, R.T.; Zhao, S.G.; et al. Genome-wide CRISPR screen identifies HNRNPL as a prostate cancer dependency regulating RNA splicing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017, 114, E5207–E5215. [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wang, L.; Huntley, M.L.; Perry, G.; Wang, X. Pathomechanisms of TDP-43 in neurodegeneration. J. Neurochem. 2018, 146, 7–20. [CrossRef]

- George, C. X., Z. Gan, Y. Liu and C. E. Samuel (2011). "Adenosine deaminases acting on RNA, RNA editing, and interferon action." J Interferon Cytokine Res 31(1): 99-117.

- Gitcho, M.A.; Bigio, E.H.; Mishra, M.; Johnson, N.; Weintraub, S.; Mesulam, M.; Rademakers, R.; Chakraverty, S.; Cruchaga, C.; Morris, J.C.; et al. TARDBP 3′-UTR variant in autopsy-confirmed frontotemporal lobar degeneration with TDP-43 proteinopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2009, 118, 633–645. [CrossRef]

- Spillantini, M.G.; Van Swieten, J.; Goedert, M. Tau gene mutations in frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17). neurogenetics 2000, 2, 0193–0205. [CrossRef]

- Hanan, M., H. Soreq and S. Kadener (2017). "CircRNAs in the brain." RNA Biol 14(8): 1028-1034.

- Hansen, T.B.; Jensen, T.I.; Clausen, B.H.; Bramsen, J.B.; Finsen, B.; Damgaard, C.K.; Kjems, J. Natural RNA circles function as efficient microRNA sponges. Nature 2013, 495, 384–388. [CrossRef]

- Haraguchi, T., S. Terada, H. Ishizu, O. Yokota, H. Yoshida, N. Takeda, Y. Kishimoto, N. Katayama, H. Takata, M. Akagi, S. Kuroda, Y. Ihara and Y. Uchitomi (2011). "Coexistence of TDP-43 and tau pathology in neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation type 1 (NBIA-1, formerly Hallervorden-Spatz syndrome)." Neuropathology 31(5): 531-539.

- Hardy, J. Alzheimer's disease: The amyloid cascade hypothesis: An update and reappraisal. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2006, 9, 151–153. [CrossRef]

- He, T.-T.; Xu, Y.-F.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Li, J.-Y.; Ou-Yang, D.; Cheng, H.-S.; Li, H.-Y.; Qin, J.; Huang, Y.; et al. A linear and circular dual-conformation noncoding RNA involved in oxidative stress tolerance in Bacillus altitudinis. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Higashi, S., E. Iseki, R. Yamamoto, M. Minegishi, H. Hino, K. Fujisawa, T. Togo, O. Katsuse, H. Uchikado, Y. Furukawa, K. Kosaka and H. Arai (2007). "Concurrence of TDP-43, tau and alpha-synuclein pathology in brains of Alzheimer's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies." Brain Res 1184: 284-294.

- Hsiao, K.-Y.; Sun, H.S.; Tsai, S.-J. Circular RNA – New member of noncoding RNA with novel functions. Exp. Biol. Med. 2017, 242, 1136–1141. [CrossRef]

- Huang, A., H. Zheng, Z. Wu, M. Chen and Y. Huang (2020). "Circular RNA-protein interactions: functions, mechanisms, and identification." Theranostics 10(8): 3503-3517.

- Hutton, M.; Lendon, C.L.; Rizzu, P.; Baker, M.; Froelich, S.; Houlden, H.; Pickering-Brown, S.; Chakraverty, S.; Isaacs, A.; Grover, A.; et al. Association of missense and 5′-splice-site mutations in tau with the inherited dementia FTDP-17. Nature 1998, 393, 702–705. [CrossRef]

- Irwin, D. J., V. M. Lee and J. Q. Trojanowski (2013). "Parkinson's disease dementia: convergence of alpha-synuclein, tau and amyloid-beta pathologies." Nat Rev Neurosci 14(9): 626-636.

- Jain, N. and A. S. Chen-Plotkin (2018). "Genetic Modifiers in Neurodegeneration." Curr Genet Med Rep 6(1): 11-19.

- Jarlstad Olesen, M. T. and S. K. L (2021). "Circular RNAs as microRNA sponges: evidence and controversies." Essays Biochem 65(4): 685-696.

- Jeck, W. R., J. A. Sorrentino, K. Wang, M. K. Slevin, C. E. Burd, J. Liu, W. F. Marzluff and N. E. Sharpless (2013). "Circular RNAs are abundant, conserved, and associated with ALU repeats." Rna 19(2): 141-157.

- Kertesz, A.; Finger, E.; Murrell, J.; Chertkow, H.; Ang, L.; Baker, M.; Ravenscroft, T.; Rademakers, R.; Munoz, D. Progressive Supranuclear Palsy in a family with TDP-43 pathology. Neurocase 2014, 21, 178–184. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.F.; Reckman, Y.J.; Aufiero, S.; van den Hoogenhof, M.M.; van der Made, I.; Beqqali, A.; Koolbergen, D.R.; Rasmussen, T.B.; van der Velden, J.; Creemers, E.E.; et al. RBM20 Regulates Circular RNA Production From the Titin Gene. Circ. Res. 2016, 119, 996–1003. [CrossRef]

- Kouri, N.; Oshima, K.; Takahashi, M.; Murray, M.E.; Ahmed, Z.; Parisi, J.E.; Yen, S.-H.C.; Dickson, D.W. Corticobasal degeneration with olivopontocerebellar atrophy and TDP-43 pathology: an unusual clinicopathologic variant of CBD. Acta Neuropathol. 2013, 125, 741–752. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Rio, D.C. Mechanisms and Regulation of Alternative Pre-mRNA Splicing. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2015, 84, 291–323. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., C. X. Liu, W. Xue, Y. Zhang, S. Jiang, Q. F. Yin, J. Wei, R. W. Yao, L. Yang and L. L. Chen (2017). "Coordinated circRNA Biogenesis and Function with NF90/NF110 in Viral Infection." Mol Cell 67(2): 214-227 e217.

- Liang, L.; Cao, C.; Ji, L.; Cai, Z.; Wang, D.; Ye, R.; Chen, J.; Yu, X.; Zhou, J.; Bai, Z.; et al. Complementary Alu sequences mediate enhancer–promoter selectivity. Nature 2023, 619, 868–875. [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-H.; Chang, C.-Y.; Huang, Y.-R.; Shen, C.-H.; Wu, Y.-C.; Chang, K.-L.; Lee, Y.-C.; Lin, Y.-C.; Ting, W.-C.; Chien, H.-J.; et al. Exon Junction Complex Mediates the Cap-Independent Translation of Circular RNA. Mol. Cancer Res. 2023, 21, 1220–1233. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y., E. B. Dammer, D. Felsky, D. M. Duong, H. U. Klein, C. C. White, M. Zhou, B. A. Logsdon, C. McCabe, J. Xu, M. Wang, T. S. Wingo, J. J. Lah, B. Zhang, J. Schneider, M. Allen, X. Wang, N. Ertekin-Taner, N. T. Seyfried, A. I. Levey, D. A. Bennett and P. L. De Jager (2021). "Atlas of RNA editing events affecting protein expression in aged and Alzheimer's disease human brain tissue." Nat Commun 12(1): 7035.

- Margvelani, G.; Maquera, K.A.A.; Welden, J.R.; Rodgers, D.W.; Stamm, S. Translation of circular RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 53. [CrossRef]

- Margvelani, G., J. R. Welden, A. A. Maquera, J. E. Van Eyk, C. Murray, S. C. Miranda Sardon and S. Stamm (2024). "Influence of FTDP-17 mutants on circular tau RNAs." Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 1870(4): 167036.

- Mehta, S.L.; Dempsey, R.J.; Vemuganti, R. Role of circular RNAs in brain development and CNS diseases. Prog. Neurobiol. 2020, 186, 101746–101746. [CrossRef]

- Memczak, S.; Jens, M.; Elefsinioti, A.; Torti, F.; Krueger, J.; Rybak, A.; Maier, L.; Mackowiak, S.D.; Gregersen, L.H.; Munschauer, M.; et al. Circular RNAs are a large class of animal RNAs with regulatory potency. Nature 2013, 495, 333–338. [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.; Zhou, H.; Feng, Z.; Xu, Z.; Tang, Y.; Wu, M. Epigenetics in Neurodevelopment: Emerging Role of Circular RNA. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 327. [CrossRef]

- Mishima, T.; Koga, S.; Lin, W.-L.; Kasanuki, K.; Castanedes-Casey, M.; Wszolek, Z.K.; Oh, S.J.; Tsuboi, Y.; Dickson, D.W. Perry Syndrome: A Distinctive Type of TDP-43 Proteinopathy. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2017, 76, 676–682. [CrossRef]

- Morera, A.A.; Ahmed, N.S.; Schwartz, J.C. TDP-43 regulates transcription at protein-coding genes and Alu retrotransposons. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Gene Regul. Mech. 2019, 1862, 194434–194434. [CrossRef]

- Mudge, J.M.; Carbonell-Sala, S.; Diekhans, M.; Martinez, J.G.; Hunt, T.; Jungreis, I.; E Loveland, J.; Arnan, C.; Barnes, I.; Bennett, R.; et al. GENCODE 2025: reference gene annotation for human and mouse. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 53, D966–D975. [CrossRef]

- Murray, H.L.; Mikheeva, S.; Coljee, V.W.; Turczyk, B.M.; Donahue, W.F.; Bar-Shalom, A.; Jarrell, K.A. Excision of Group II Introns as Circles. Mol. Cell 2001, 8, 201–211. [CrossRef]

- Nag, S.; Schneider, J.A. Limbic-predominant age-related TDP43 encephalopathy (LATE) neuropathological change in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2023, 19, 525–541. [CrossRef]

- Neeman, Y.; Levanon, E.Y.; Jantsch, M.F.; Eisenberg, E. RNA editing level in the mouse is determined by the genomic repeat repertoire. RNA 2006, 12, 1802–1809. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, P.T.; Abner, E.L.; Patel, E.; Anderson, S.; Wilcock, D.M.; Kryscio, R.J.; Van Eldik, L.J.; A Jicha, G.; Gal, Z.; Nelson, R.S.; et al. The Amygdala as a Locus of Pathologic Misfolding in Neurodegenerative Diseases. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2017, 77, 2–20. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, P.T.; Abner, E.L.; Schmitt, F.A.; Kryscio, R.J.; Jicha, G.A.; Smith, C.D.; Davis, D.G.; Poduska, J.W.; Patel, E.; Mendiondo, M.S.; et al. Modeling the Association between 43 Different Clinical and Pathological Variables and the Severity of Cognitive Impairment in a Large Autopsy Cohort of Elderly Persons. Brain Pathol. 2009, 20, 66–79. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, P.T.; Brayne, C.; Flanagan, M.E.; Abner, E.L.; Agrawal, S.; Attems, J.; Castellani, R.J.; Corrada, M.M.; Cykowski, M.D.; Di, J.; et al. Frequency of LATE neuropathologic change across the spectrum of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology: combined data from 13 community-based or population-based autopsy cohorts. Acta Neuropathol. 2022, 144, 27–44. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, P. T., D. W. Dickson, J. Q. Trojanowski, C. R. Jack, P. A. Boyle, K. Arfanakis, R. Rademakers, I. Alafuzoff, J. Attems, C. Brayne, I. T. S. Coyle-Gilchrist, H. C. Chui, D. W. Fardo, M. E. Flanagan, G. Halliday, S. R. K. Hokkanen, S. Hunter, G. A. Jicha, Y. Katsumata, C. H. Kawas, C. D. Keene, G. G. Kovacs, W. A. Kukull, A. I. Levey, N. Makkinejad, T. J. Montine, S. Murayama, M. E. Murray, S. Nag, R. A. Rissman, W. W. Seeley, R. A. Sperling, C. L. White, 3rd, L. Yu and J. A. Schneider (2019). "Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE): consensus working group report." Brain 142(6): 1503-1527.

- Nelson, P. T., J. A. Schneider, G. A. Jicha, M. T. Duong and D. A. Wolk (2023). "When Alzheimer's is LATE: Why Does it Matter?" Ann Neurol 94(2): 211-222.

- Nelson, P.T.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Abner, E.L.; Al-Janabi, O.M.; Jicha, G.A.; Schmitt, F.A.; Smith, C.D.; Fardo, D.W.; Wang, W.-X.; Kryscio, R.J.; et al. “New Old Pathologies”: AD, PART, and Cerebral Age-Related TDP-43 With Sclerosis (CARTS). J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2016, 75, 482–498. [CrossRef]

- Neumann, M.; Sampathu, D.M.; Kwong, L.K.; Truax, A.C.; Micsenyi, M.C.; Chou, T.T.; Bruce, J.; Schuck, T.; Grossman, M.; Clark, C.M.; et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Science 2006, 314, 130–133. [CrossRef]

- Nigro, J. M., K. R. Cho, E. R. Fearon, S. E. Kern, J. M. Ruppert, J. D. Oliner, K. W. Kinzler and B. Vogelstein (1991). "Scrambled exons." Cell 64(3): 607-613.

- Noto, J.J.; Schmidt, C.A.; Matera, A.G. Engineering and expressing circular RNAs via tRNA splicing. RNA Biol. 2017, 14, 978–984. [CrossRef]

- Panda, A. C. (2018). "Circular RNAs Act as miRNA Sponges." Adv Exp Med Biol 1087: 67-79.

- Patop, I. L., S. Wust and S. Kadener (2019). "Past, present, and future of circRNAs." EMBO J 38(16): e100836.

- Paz-Yaacov, N.; Levanon, E.Y.; Nevo, E.; Kinar, Y.; Harmelin, A.; Jacob-Hirsch, J.; Amariglio, N.; Eisenberg, E.; Rechavi, G. Adenosine-to-inosine RNA editing shapes transcriptome diversity in primates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010, 107, 12174–12179. [CrossRef]

- Piwecka, M.; Glažar, P.; Hernandez-Miranda, L.R.; Memczak, S.; Wolf, S.A.; Rybak-Wolf, A.; Filipchyk, A.; Klironomos, F.; Cerda Jara, C.A.; Fenske, P.; et al. Loss of a mammalian circular RNA locus causes miRNA deregulation and affects brain function. Science 2017, 357, eaam8526. [CrossRef]

- Puttaraju, M. and M. D. Been (1992). "Group I permuted intron-exon (PIE) sequences self-splice to produce circular exons." Nucleic Acids Res 20(20): 5357-5364.

- Rahimi, K., M. T. Veno, D. M. Dupont and J. Kjems (2021). "Nanopore sequencing of brain-derived full-length circRNAs reveals circRNA-specific exon usage, intron retention and microexons." Nat Commun 12(1): 4825.

- Ramanan, V. K. and A. J. Saykin (2013). "Pathways to neurodegeneration: mechanistic insights from GWAS in Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and related disorders." Am J Neurodegener Dis 2(3): 145-175.

- Roy, E.R.; Wang, B.; Wan, Y.-W.; Chiu, G.; Cole, A.; Yin, Z.; Propson, N.E.; Xu, Y.; Jankowsky, J.L.; Liu, Z.; et al. Type I interferon response drives neuroinflammation and synapse loss in Alzheimer disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 1912–1930. [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, A.; Makioka, K.; Fukuda, T.; Takatama, M.; Okamoto, K. Accumulation of phosphorylated TDP-43 in the CNS of a patient with Cockayne syndrome. Neuropathology 2013, 33, 673–677. [CrossRef]

- Samuel, C. E. (2019). "Adenosine deaminase acting on RNA (ADAR1), a suppressor of double-stranded RNA-triggered innate immune responses." J Biol Chem 294(5): 1710-1720.

- Sanger, H.L.; Klotz, G.; Riesner, D.; Gross, H.J.; Kleinschmidt, A.K. Viroids are single-stranded covalently closed circular RNA molecules existing as highly base-paired rod-like structures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1976, 73, 3852–3856. [CrossRef]

- Shenouda, M.; Xiao, S.; MacNair, L.; Lau, A.; Robertson, J. A C-Terminally Truncated TDP-43 Splice Isoform Exhibits Neuronal Specific Cytoplasmic Aggregation and Contributes to TDP-43 Pathology in ALS. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 868556. [CrossRef]

- Smith, V.D.; Bachstetter, A.D.; Ighodaro, E.; Roberts, K.; Abner, E.L.; Fardo, D.W.; Nelson, P.T. Overlapping but distinct TDP-43 and tau pathologic patterns in aged hippocampi. Brain Pathol. 2017, 28, 264–273. [CrossRef]

- Spillantini, M. G. and M. Goedert (2013). "Tau pathology and neurodegeneration." Lancet Neurol 12(6): 609-622.

- Spina, S., D. R. Schonhaut, B. F. Boeve, W. W. Seeley, R. Ossenkoppele, J. P. O'Neil, A. Lazaris, H. J. Rosen, A. L. Boxer, D. C. Perry, B. L. Miller, D. W. Dickson, J. E. Parisi, W. J. Jagust, M. E. Murray and G. D. Rabinovici (2017). "Frontotemporal dementia with the V337M MAPT mutation: Tau-PET and pathology correlations." Neurology 88(8): 758-766.

- Spires-Jones, T.L.; Attems, J.; Thal, D.R. Interactions of pathological proteins in neurodegenerative diseases. Acta Neuropathol. 2017, 134, 187–205. [CrossRef]

- Sreedharan, J.; Blair, I.P.; Tripathi, V.B.; Hu, X.; Vance, C.; Rogelj, B.; Ackerley, S.; Durnall, J.C.; Williams, K.L.; Buratti, E.; et al. TDP-43 Mutations in Familial and Sporadic Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Science 2008, 319, 1668–1672. [CrossRef]

- Takashima, A. Hyperphosphorylated Tau is a Cause of Neuronal Dysfunction in Tauopathy. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2008, 14, 371–375. [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Xie, Y.; Yu, T.; Liu, N.; Wang, Z.; Woolsey, R.J.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Qin, W.; Zhang, Y.; et al. m6A-dependent biogenesis of circular RNAs in male germ cells. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 211–228. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.M.; Minter, M.R.; Newman, A.G.; Zhang, M.; Adlard, P.A.; Crack, P.J. Type-1 interferon signaling mediates neuro-inflammatory events in models of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2014, 35, 1012–1023. [CrossRef]

- Tollervey, J.R.; Curk, T.; Rogelj, B.; Briese, M.; Cereda, M.; Kayikci, M.; König, J.; Hortobágyi, T.; Nishimura, A.L.; Župunski, V.; et al. Characterizing the RNA targets and position-dependent splicing regulation by TDP-43. Nat. Neurosci. 2011, 14, 452–458. [CrossRef]

- Trojanowski, J.Q.; Lee, V.M. “Fatal Attractions” of Proteins: A Comprehensive Hypothetical Mechanism Underlying Alzheimer's Disease and Other Neurodegenerative Disorders. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2000, 924, 62–67. [CrossRef]

- Van Deerlin, V.M.; Leverenz, J.B.; Bekris, L.M.; Bird, T.D.; Yuan, W.; Elman, L.B.; Clay, D.; Wood, E.M.; Chen-Plotkin, A.S.; Martinez-Lage, M.; et al. TARDBP mutations in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with TDP-43 neuropathology: a genetic and histopathological analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2008, 7, 409–416. [CrossRef]

- Vesely, C.; Jantsch, M.F. An I for an A: Dynamic Regulation of Adenosine Deamination-Mediated RNA Editing. Genes 2021, 12, 1026. [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.K.; Daniels, C.M.L.; Goldman, J.E.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Lee, V.M.-Y.; Messing, A. Astrocytic TDP-43 Pathology in Alexander Disease. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 6448–6458. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-Y.; Wang, I.-F.; Bose, J.; Shen, C.-K. Structural diversity and functional implications of the eukaryotic TDP gene family. Genomics 2004, 83, 130–139. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.L.; Bao, Y.; Yee, M.-C.; Barrett, S.P.; Hogan, G.J.; Olsen, M.N.; Dinneny, J.R.; Brown, P.O.; Salzman, J. Circular RNA Is Expressed across the Eukaryotic Tree of Life. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e90859. [CrossRef]

- Weihl, C.C.; Temiz, P.; E Miller, S.; Watts, G.; Smith, C.; Forman, M.; I Hanson, P.; Kimonis, V.; Pestronk, A. TDP-43 accumulation in inclusion body myopathy muscle suggests a common pathogenic mechanism with frontotemporal dementia. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2008, 79, 1186–1189. [CrossRef]

- Welden, J.R.; Margvelani, G.; Maquera, K.A.A.; Gudlavalleti, B.; Sardón, S.C.M.; Campos, A.R.; Robil, N.; Lee, D.C.; Hernandez, A.G.; Wang, W.-X.; et al. RNA editing of microtubule-associated protein tau circular RNAs promotes their translation and tau tangle formation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, 12979–12996. [CrossRef]

- Welden, J.R.; Margvelani, G.; Maquera, K.A.A.; Gudlavalleti, B.; Sardón, S.C.M.; Campos, A.R.; Robil, N.; Lee, D.C.; Hernandez, A.G.; Wang, W.-X.; et al. RNA editing of microtubule-associated protein tau circular RNAs promotes their translation and tau tangle formation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, 12979–12996. [CrossRef]

- Welden, J.R.; van Doorn, J.; Nelson, P.T.; Stamm, S. The human MAPT locus generates circular RNAs. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Basis Dis. 2018, 1864, 2753–2760. [CrossRef]

- Weskamp, K.; Tank, E.M.; Miguez, R.; McBride, J.P.; Gómez, N.B.; White, M.; Lin, Z.; Gonzalez, C.M.; Serio, A.; Sreedharan, J.; et al. Shortened TDP43 isoforms upregulated by neuronal hyperactivity drive TDP43 pathology in ALS. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 1139–1155. [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R. Tauopathies: classification and clinical update on neurodegenerative diseases associated with microtubule-associated protein tau. Intern. Med. J. 2006, 36, 652–660. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.; Liu, H.-S.; Zhou, C.; Yang, X.; Huang, L.; Jie, H.-Q.; Zeng, Z.-W.; Zheng, X.-B.; Li, W.-X.; Liu, Z.-Z.; et al. A novel protein encoded by circINSIG1 reprograms cholesterol metabolism by promoting the ubiquitin-dependent degradation of INSIG1 in colorectal cancer. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wilusz, J.E.; Chen, L.-L. Biogenesis and Regulatory Roles of Circular RNAs. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 38, 263–289. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Fan, X.; Mao, M.; Song, X.; Wu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, Y.; Yang, Y.; Chen, L.-L.; Wang, Y.; et al. Extensive translation of circular RNAs driven by N6-methyladenosine. Cell Res. 2017, 27, 626–641. [CrossRef]

- Yokota, O.; Davidson, Y.; Bigio, E.H.; Ishizu, H.; Terada, S.; Arai, T.; Hasegawa, M.; Akiyama, H.; Sikkink, S.; Pickering-Brown, S.; et al. Phosphorylated TDP-43 pathology and hippocampal sclerosis in progressive supranuclear palsy. Acta Neuropathol. 2010, 120, 55–66. [CrossRef]

- Zarranz, J.J.; Ferrer, I.; Lezcano, E.; Forcadas, M.I.; Eizaguirre, B.; Atarés, B.; Puig, B.; Gómez-Esteban, J.C.; Fernández-Maiztegui, C.; Rouco, I.; et al. A novel mutation (K317M) in the MAPT gene causes FTDP and motor neuron disease. Neurology 2005, 64, 1578–1585. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).