Submitted:

11 August 2025

Posted:

11 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

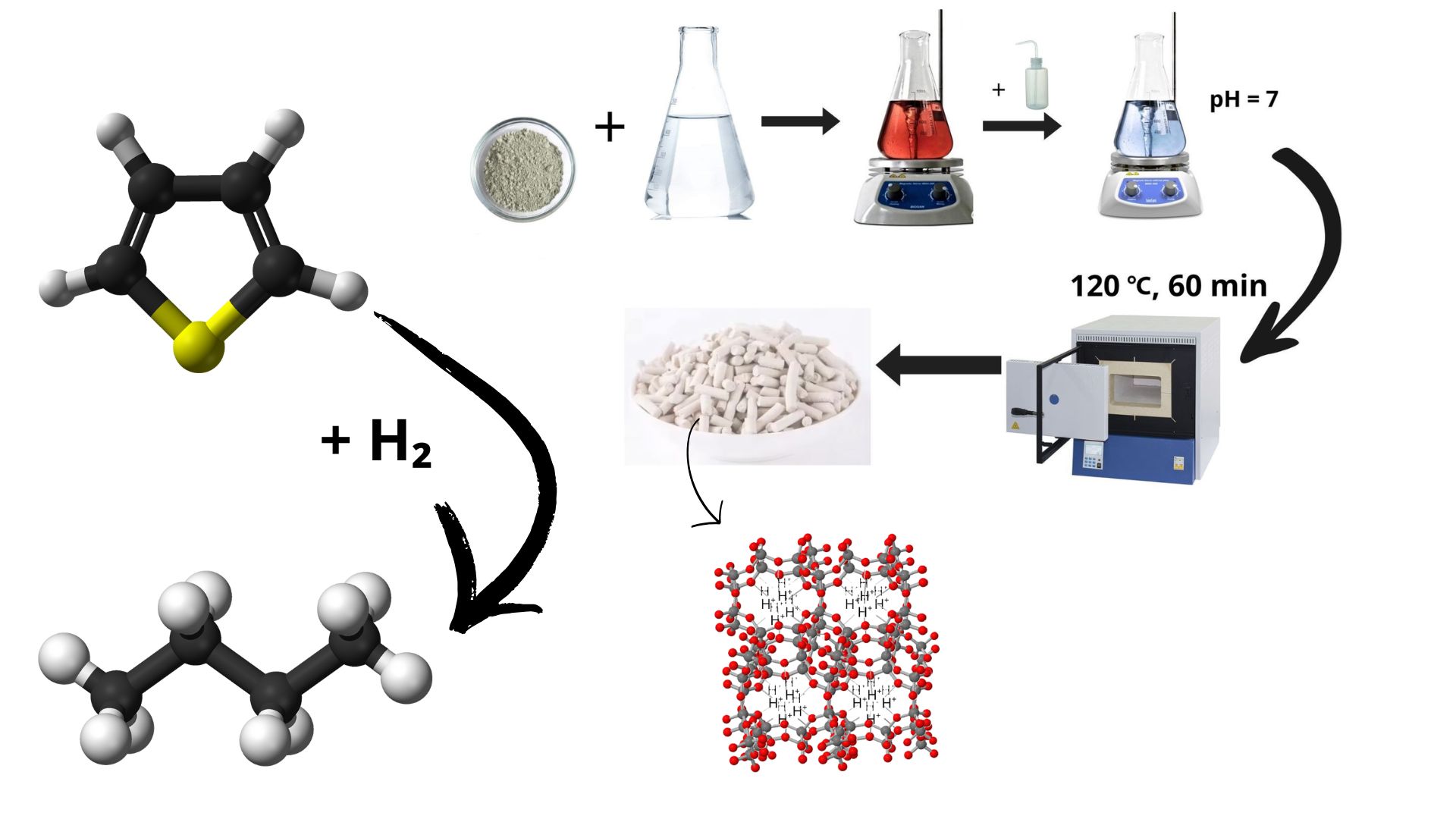

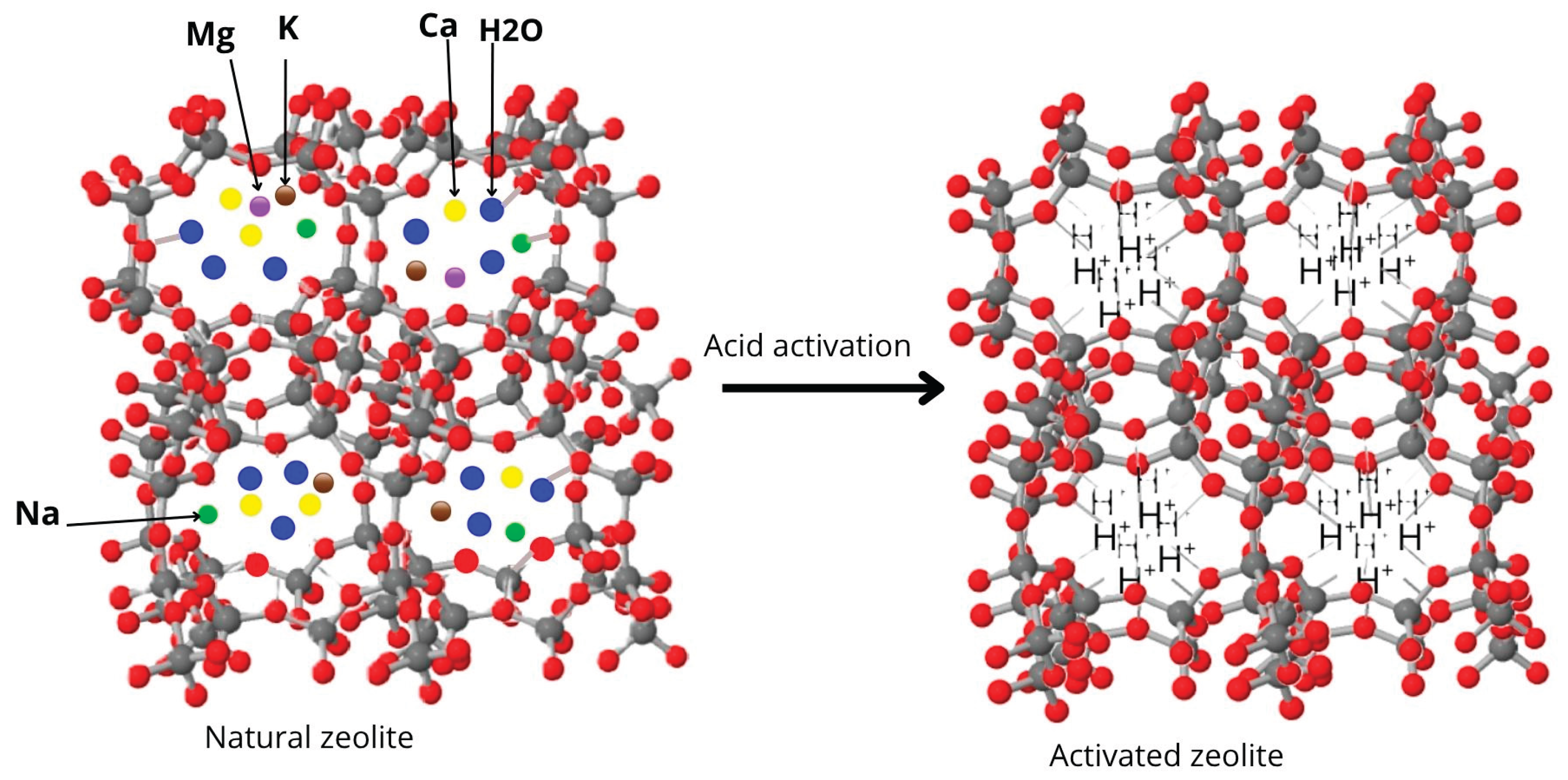

2.1. Acid Activation of Natural Zeolite

2.2. Thermal Treatment of Activated Zeolite

2.3. Characterization Techniques

2.4. Catalytic Activity

3. Results

3.1. Physicochemical Characterization of Zeolite (Clinoptilolite) from the Shankhanai Deposit

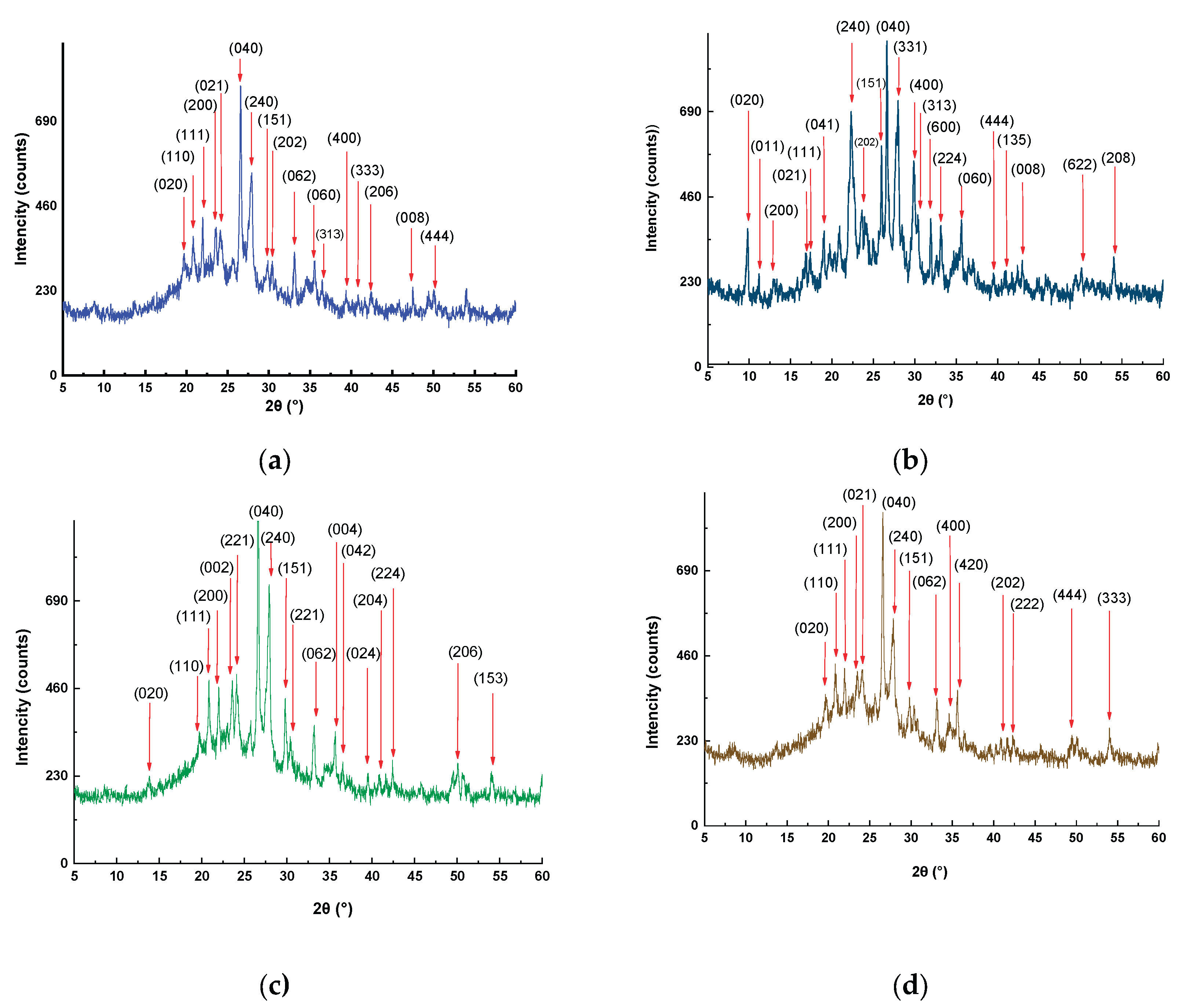

3.1.1. X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

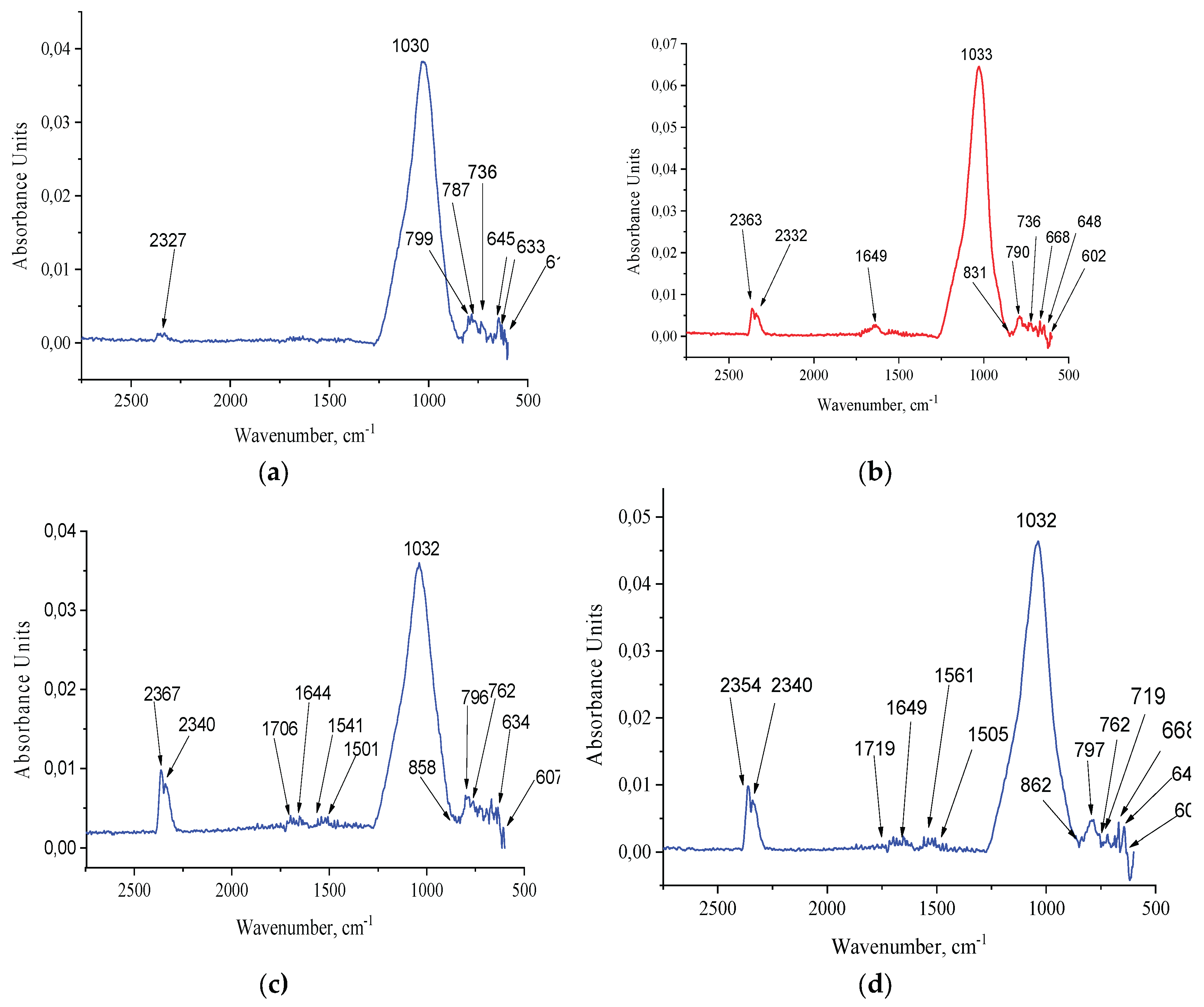

3.1.2. FTIR Analysis

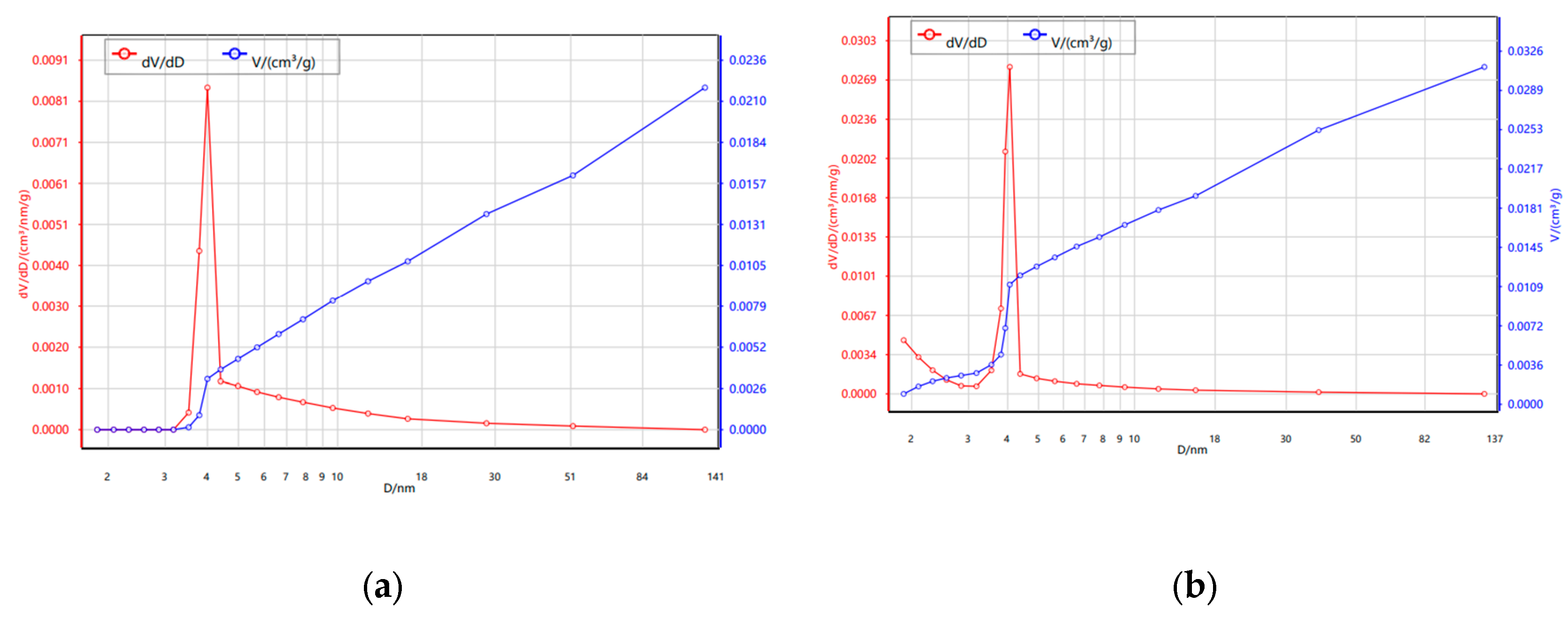

3.1.3. N₂ Adsorption–Desorption Isotherms (BET)

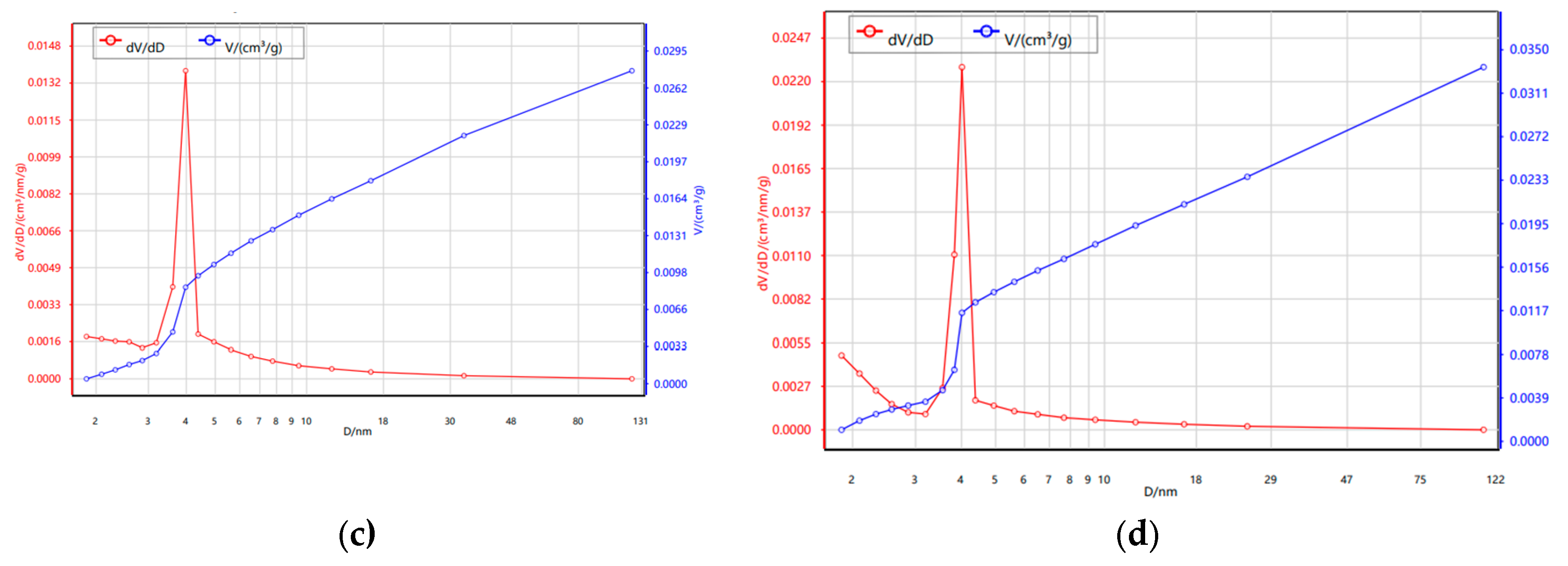

3.1.4. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

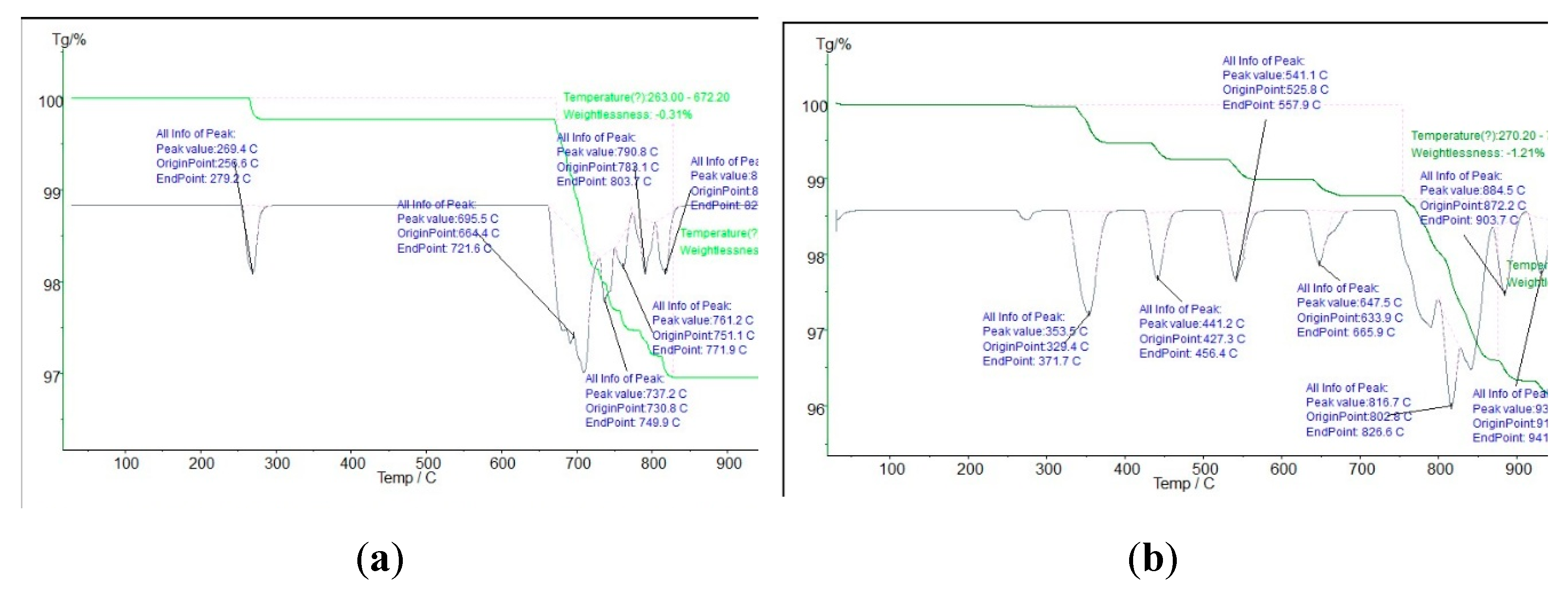

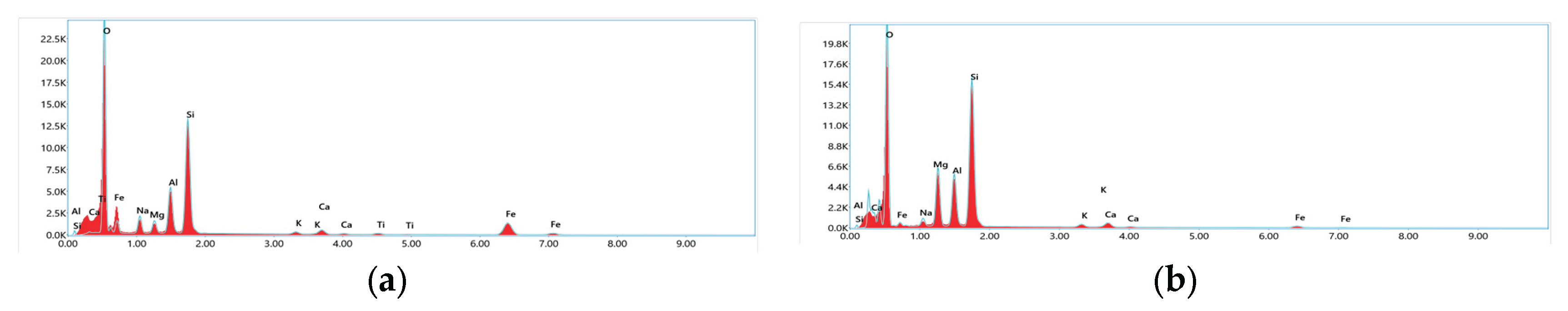

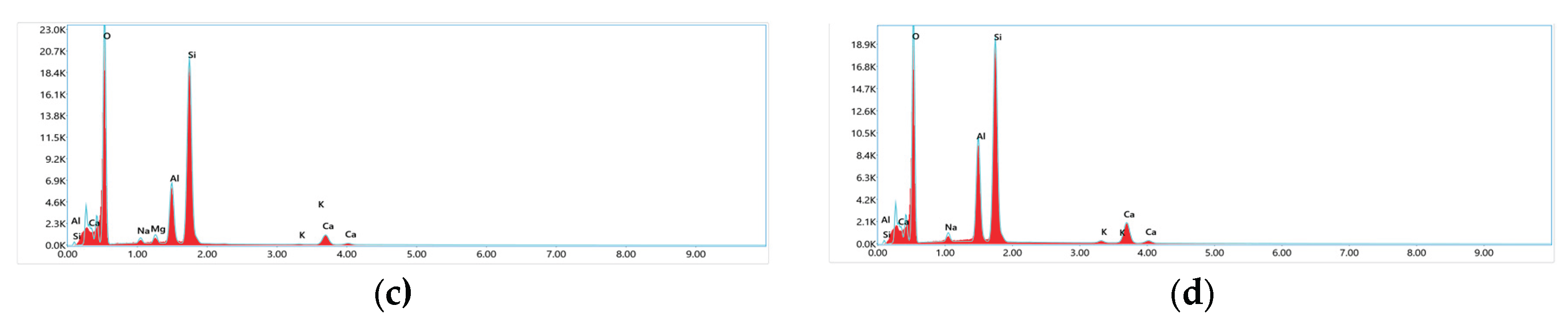

3.1.5. SEM and EDX Analysis

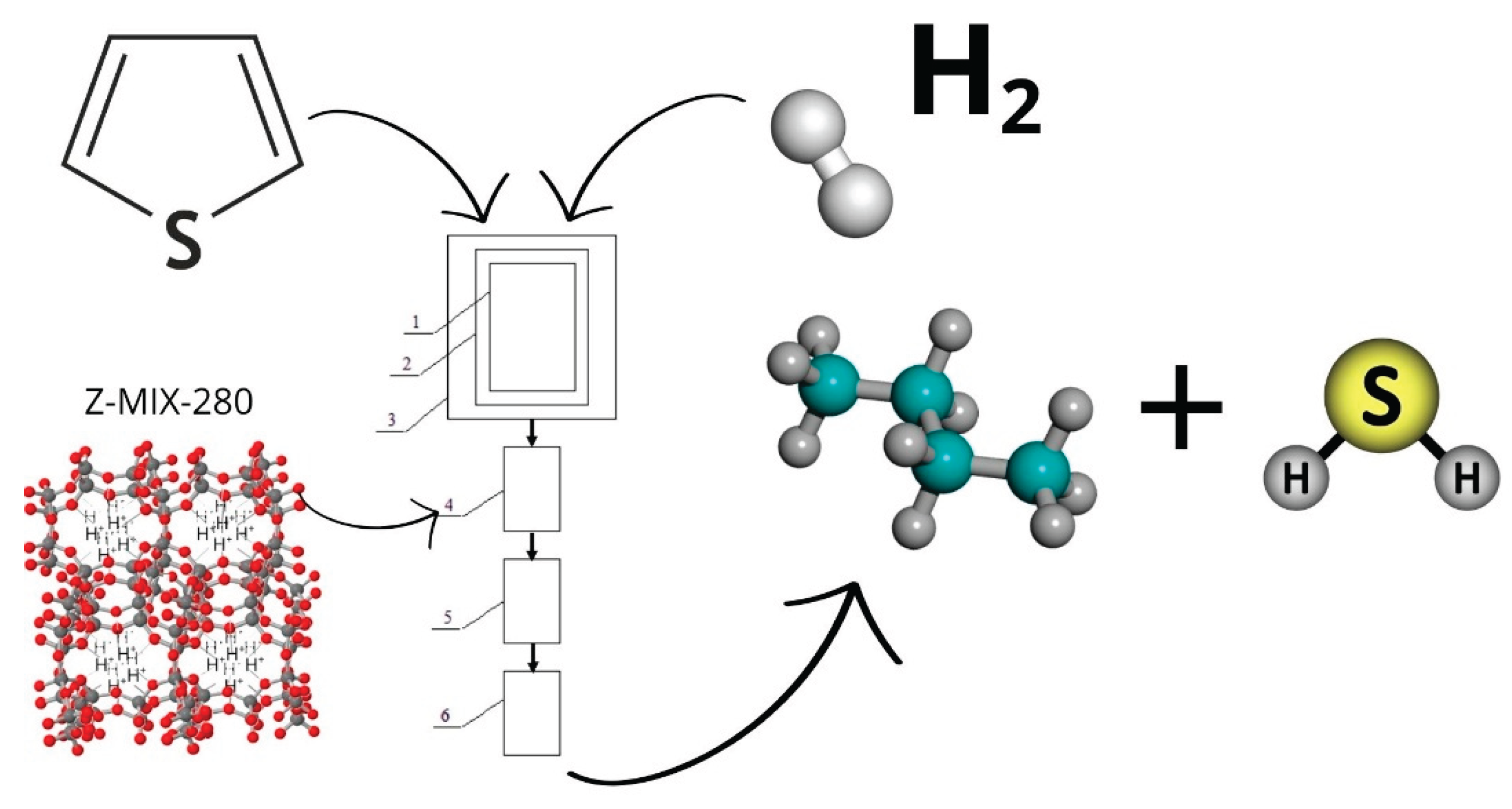

3.2. Catalytic Activity of Zeolite

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| XRD | X-ray Diffraction |

| EDAX | Energy Dispersive X-ray Analysis |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

References

- European Parliament and Council. Directive 2009/30/EC amending Directive 98/70/EC as regards the specification of petrol, diesel and gas-oil and introducing a mechanism to monitor and reduce greenhouse gas emissions; Official Journal of the European Union, 2009.

- International Maritime Organization (IMO). IMO 2020 – Reducing Sulphur Oxide Emissions.

- Shafiq, I.; Shafique, S.; Akhter, P.; Alazmi, A.; Naqvi, S.A.R. Recent Developments in Alumina-Supported Hydrodesulfurization Catalysts. Catal. Rev. 2020, 62, 96–164. [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Wang, Q.; Wei, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, X. Tuning Effect of Brønsted Acidity on FeZn Bimetallic HDS Catalyst with Y Zeolite/γ-Al₂O₃ Support. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 6482–6491. [CrossRef]

- Al-Otaibi, R.M.; Al-Malki, A.L.; Hossain, M.M. Modification of ZSM-5 Mesoporosity for Enhanced Hydrodesulfurization of DBT. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105593. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Li, M.; Li, Y.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, J. Adsorption of Sulfur Compounds on AgX Hierarchical Zeolite. Environ. Sci.: Atmos. 2021, 1, 377–387. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Li, L.; Chen, Y. TiO₂ Modified HY Zeolite for Oxidative Desulfurization. Silicon 2024, 16, 867–875. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, D.; Park, J. GO-Modified TiO₂ and Al₂O₃ Supports for NiMo Hydrodesulfurization Catalysts. MRS Adv. 2025, 10, 215–224. [CrossRef]

- Khrysonidi, V.A.; Kirilenko, V.A.; Khoruzhiy, K.I.; Shatokhina, E.M. Hierarchical zeolites and modern methods of their synthesis. Sci. Herit. 2021, 71(1), 10–14.

- Spiridonov, A.M.; et al. Prospects for the use of acid-activated natural zeolite from the Khonguruu deposit (Yakutia) for filling polymers. Vestn. Sev.-Vost. Fed. Univ. im. M.K. Ammosova 2014, 11(3), 7–12.

- Razmakhnin, K.K.; Khat’kova, A.N. Modification of zeolite properties to expand their application areas. Gorn. Inf.-Analit. Byul. 2011, 4, 246–252.

- Abdulina, S.A.; et al. Features of the mineral composition of zeolite from the Taizhuzgen deposit. Vestn. Kazakhst. Gos. Tekh. Univ. 2014, 2, 48.

- Vasilina, G.K.; Moisa, R.M.; Abildin, T.S.; Yesemaliyeva, A.S.; Kuanyshova, S.D. Influence of the structure of natural zeolites on their acidic characteristics. Izv. NAN RK. Ser. Khimii i Tekhnologii 2017, 6, 81–85.

- Mambetova, M.; Yergaziyeva, G.Y.; Zhoketayeva, A.B. Physicochemical characteristics and carbon dioxide sorption properties of natural zeolites. Gorenie i Plazmokhimiya 2022.

- Akhalbedashvili, L.G. Catalytic and Ion-Exchange Properties of Modified Zeolites and Superconducting Cuprates. Ph.D. Thesis, Tbilisi, Georgia, 2006.

- Koval’, L.M.; Korobitsyna, L.L.; Vosmerikov, A.V. Synthesis, Physicochemical and Catalytic Properties of High-Silica Zeolites, 3rd ed.; TGU: Tomsk, Russia, 2001; pp. 50.

- Sultanbaeva, G.Sh.; et al. Physicochemical studies of zeolite activated with hydrochloric acid. Izv. Nats. Akad. Nauk Resp. Kazakhstan, Ser. Khim. 2006, 4, 68.

- Mamedova, G.A. Influence of boiling acids on the structure of natural Nakhchivan mordenite. Bashk. Khim. Zh. 2016, 23(3), 20–27.

- Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, J. Modification of natural zeolites for enhanced catalytic activity: A review. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2023, 347, 112364. [CrossRef]

- Chizallet, C.; Bouchy, C.; Larmier, K. Molecular views on mechanisms of Brønsted acid catalyzed reactions in zeolites. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123(9), 6107–6196. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Yang, M. Acid-modified clinoptilolite for ammonia removal and catalytic applications. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9(5), 105927. [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.T.; et al. Acid-modified zeolite for removal of environmental pollutants: Mechanism and efficiency. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27(3), 3155–3170. [CrossRef]

- Celik, G.; Patel, A.; Choudhary, V. Tailoring the surface acidity of clinoptilolite for catalytic applications: A comparative study of HCl and NH₄Cl treatments. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2022, 342, 111591. [CrossRef]

- Teshima, K.; Kinoshita, K.; Tanaka, K. Structural evolution of clinoptilolite upon acid treatment. Appl. Clay Sci. 2020, 184, 105402. [CrossRef]

- Miądlicki, P.; Wróblewska, A.; Kiełbasa, K.; Koren, Z.C.; Michalkiewicz, B. Sulfuric acid modified clinoptilolite as a solid green catalyst for solvent-free α-pinene isomerization process. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2021, 324, 111266. [CrossRef]

- Tanirbergenova, S.; Tagayeva, A.; Rossi, C.O.; Porto, M.; Caputo, P.; Kanzharkan, E.; Tugelbayeva, D.; Zhylybayeva, N.; Tazhu, K.; Tileuberdi, Y. Studying the Characteristics of Tank Oil Sludge. Processes 2024, 12(9), 2007. [CrossRef]

- Sadenova, M.A.; Abdulina, S.A.; Tungatarova, S.A.; et al. The use of natural Kazakhstan zeolites for the development of gas purification catalysts. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2016, 18(2), 449–459. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Shang, X.; Zhang, T.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, H.; Lu, X. Study on the Pyrolysis Characteristics and Kinetics of Lignite Blended with Biomass. Molecules 2020, 25(11), 2570. https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/25/11/2570.

- Aitugan, A.N.; Tanirbergenova, S.K.; Tileuberdi, Ye.; Yucel, O.; Tugelbayeva, D.; Mansurov, Z.; Ongarbayev, Ye.K. A carbonised cobalt catalyst supported by acid-activated clay for the selective hydrogenation of acetylene. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 2021, 133(1), 277–292.

- Khalid, M.; et al. Natural zeolites in water treatment: Potentials and limitations. Chemosphere 2020, 245, 125624. [CrossRef]

- Zahid, M.; Doszhanov, Y.; Saurykova, K.; et al. Modification and Application of Natural Clinoptilolite and Mordenite from Almaty Region for Drinking Water Purification. Molecules 2025, 30(9), 2021. [CrossRef]

- Velichkina, L.; Barbashin, Yu.; Vosmerikov, A. Effect of Acid Treatment on the Properties of Zeolite Catalyst for Straight-Run Gasoline Upgrading. Catal. Res. 2021, 1(4), 16. https://www.lidsen.com/journals/cr/cr-01-04-016.

- Tsitsishvili, V.; et al. Acid treatment of Georgian, Kazakhstani and Armenian natural heulandite-clinoptilolites II. Adsorption and porous structure. InterConf. 2023, March. [CrossRef]

| Sample | BET SSA (m²/g) |

DR Micropore SSA (m²/g) |

DA Micropore Volume (cm³/g) |

DR Avg. Pore Diameter (nm) |

Average Pore Diameter (4V/A, nm) |

| NZ | 4.95 | 5.91 | 0.0054 | 2.09 | 15.99 |

| Z- HNO₃ | 59.86 | 67.98 | 0.0330 | 1.36 | 3.26 |

| Z- HNO₃-600 | 19.39 | 21.09 | 0.0151 | 1.75 | 6.21 |

| Z-MIX-280 | 48.07 | 54.50 | 0.0276 | 1.52 | 3.84 |

| Sample | phase composition, mass.% | ||||||||

| Al2O3 | SiO2 | Fe2O3 | MgO | Na2О | K2O | CaO | TiO2 | H2O | |

| NZ | 15.1 | 62.2 | 5.8 | 3.6 | 5.8 | 2.1 | 4.1 | 0.7 | 0.6 |

| Z- HNO₃ | 16.7 | 71.4 | 2.9 | 2.28 | 2.6 | 1.5 | 2.1 | 0.02 | 0.5 |

| Z- HNO₃-600 | 18.2 | 73.5 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 0.01 | 0.09 |

| Z-MIX-280 | 20.2 | 76.04 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).