Submitted:

23 May 2025

Posted:

26 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. First Visit—Instrumentation Phase

2.2. Second Visit—Obturation Phase

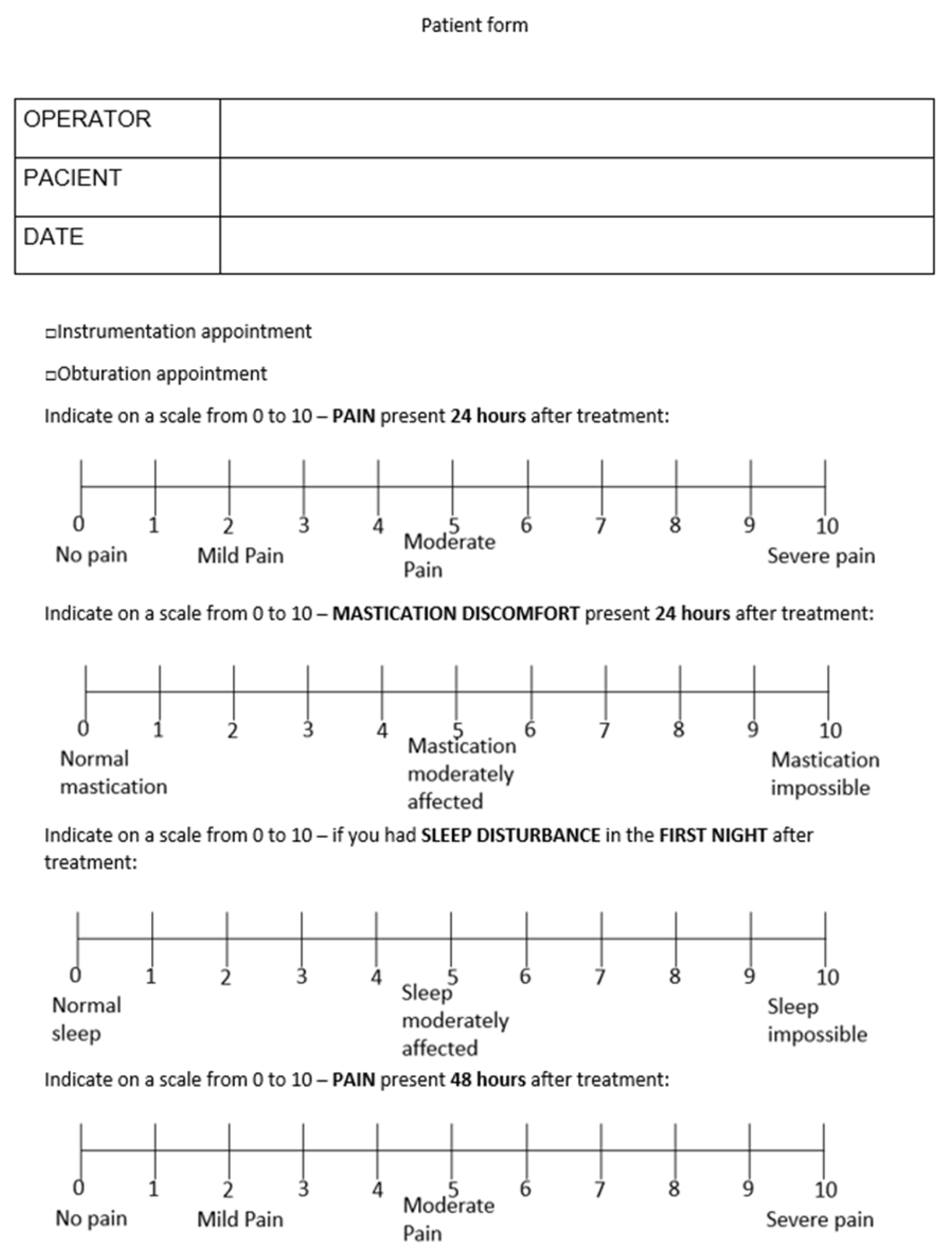

2.3. Post-Operative Pain Assessment

2.4. Statistical Analysis

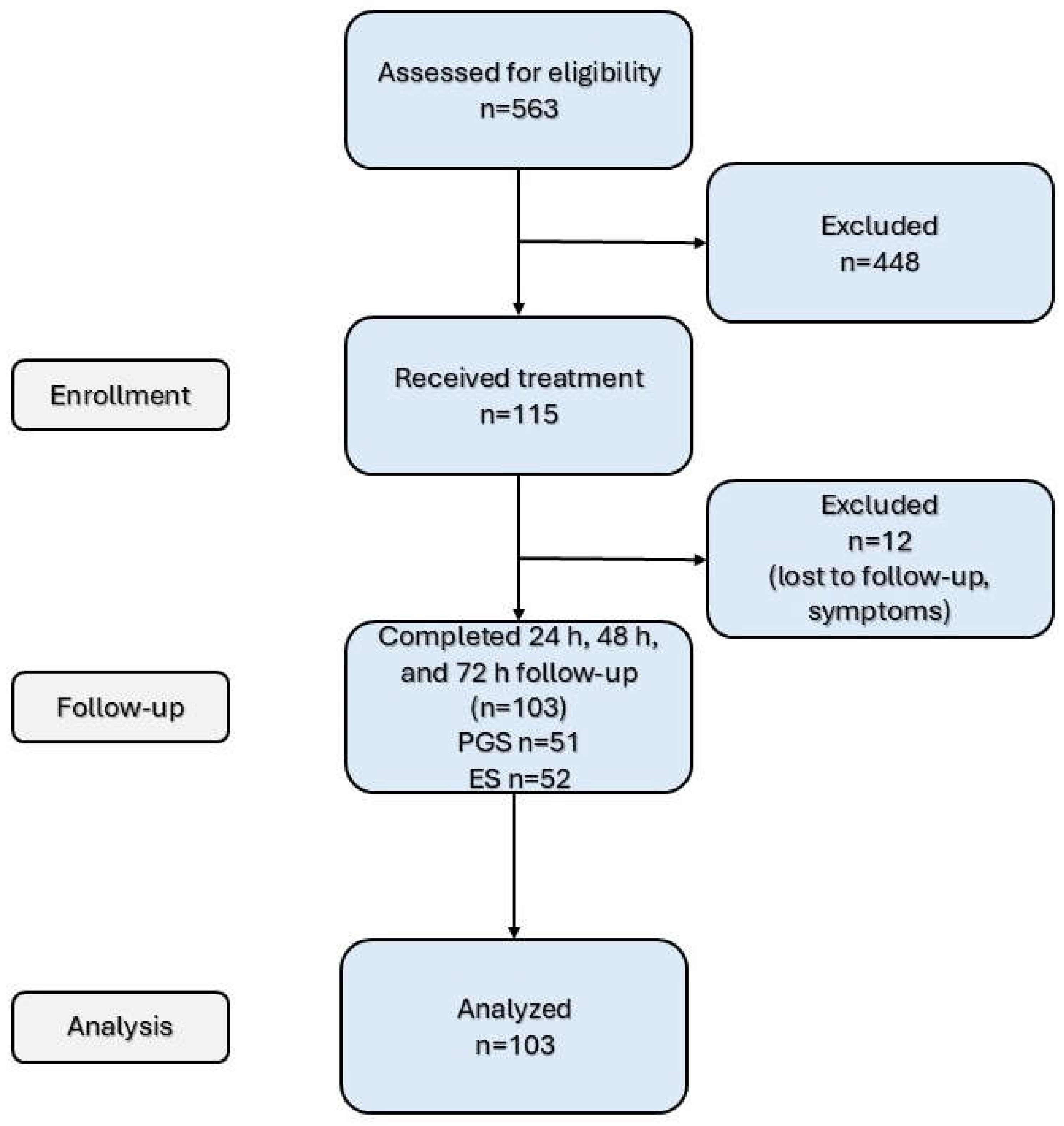

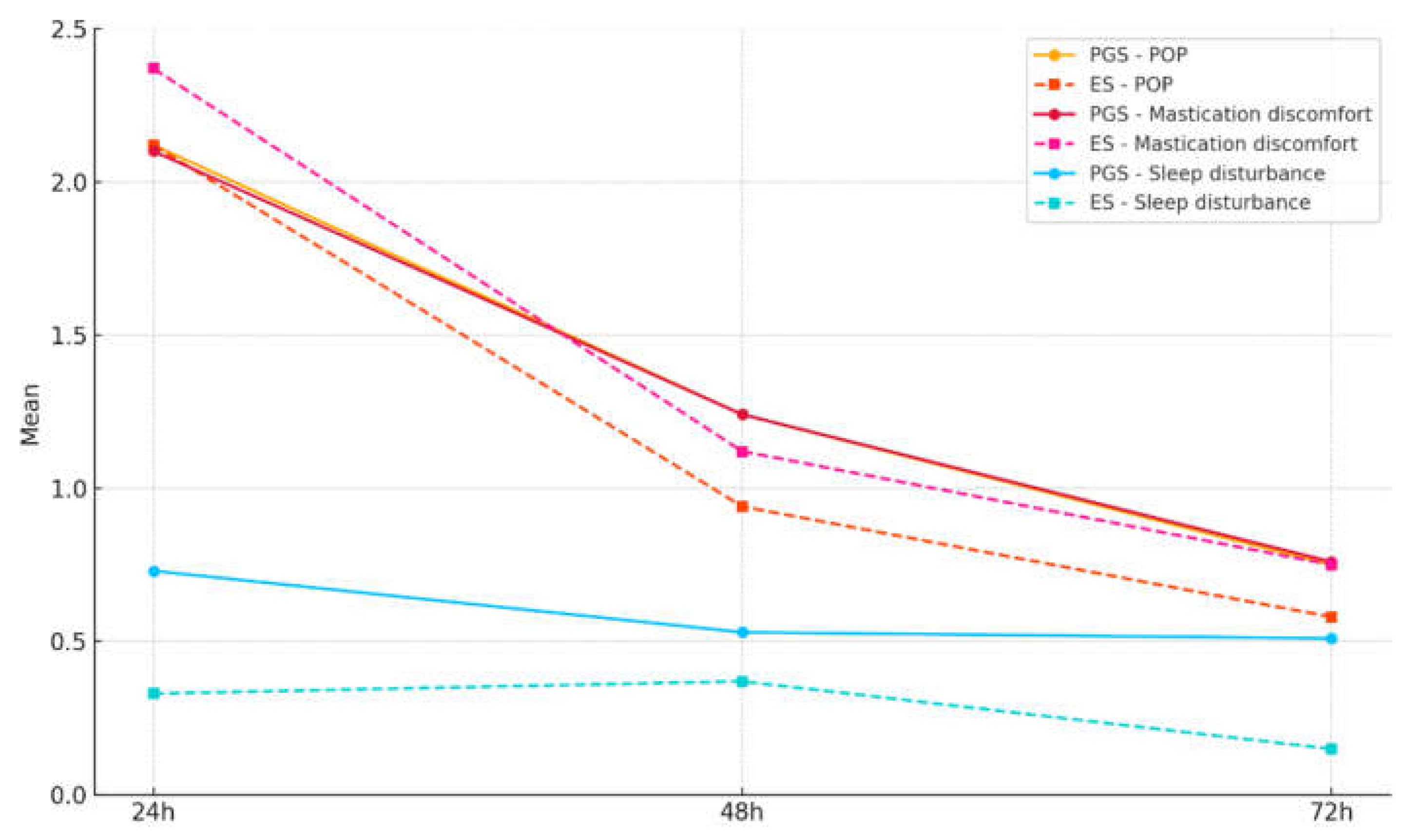

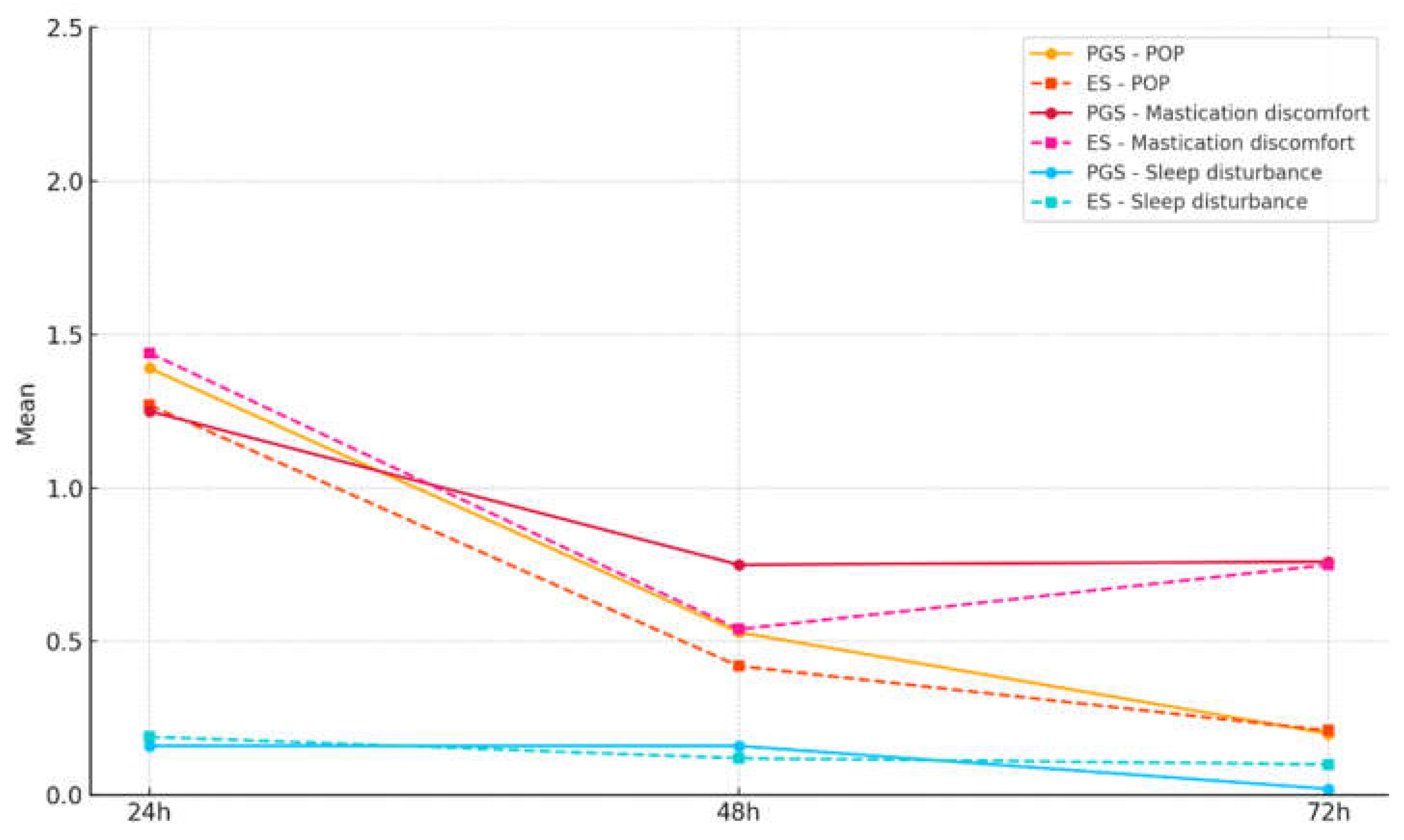

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAE | American Association of Endodontics |

| ESs | Endodontics specialists |

| CWC | Continuous wave condensation |

| LEO | Lesion of endodontic origin |

| NRS | Numeric rating scale |

| NSAID | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug |

| POP | Post-operative pain |

| PGSs | Postgraduate students |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| TFHF | Total Fill Hi-Flow BC Sealer |

Appendix A

| Item No | Recommendation | Article section | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Title and abstract | 1 | (a) Indicate the study’s design with a commonly used term in the title or the abstract | Abstract - material and methods |

| (b) Provide in the abstract an informative and balanced summary of what was done and what was found | Abstract | ||

| Introduction | |||

| Background/rationale | 2 | Explain the scientific background and rationale for the investigation being reported | 2nd, 6th paragraph |

| Objectives | 3 | State specific objectives, including any prespecified hypotheses | 7th, 8th paragraph |

| Methods | |||

| Study design | 4 | Present key elements of study design early in the paper | Patient selection – 1st, 3rd paragraph |

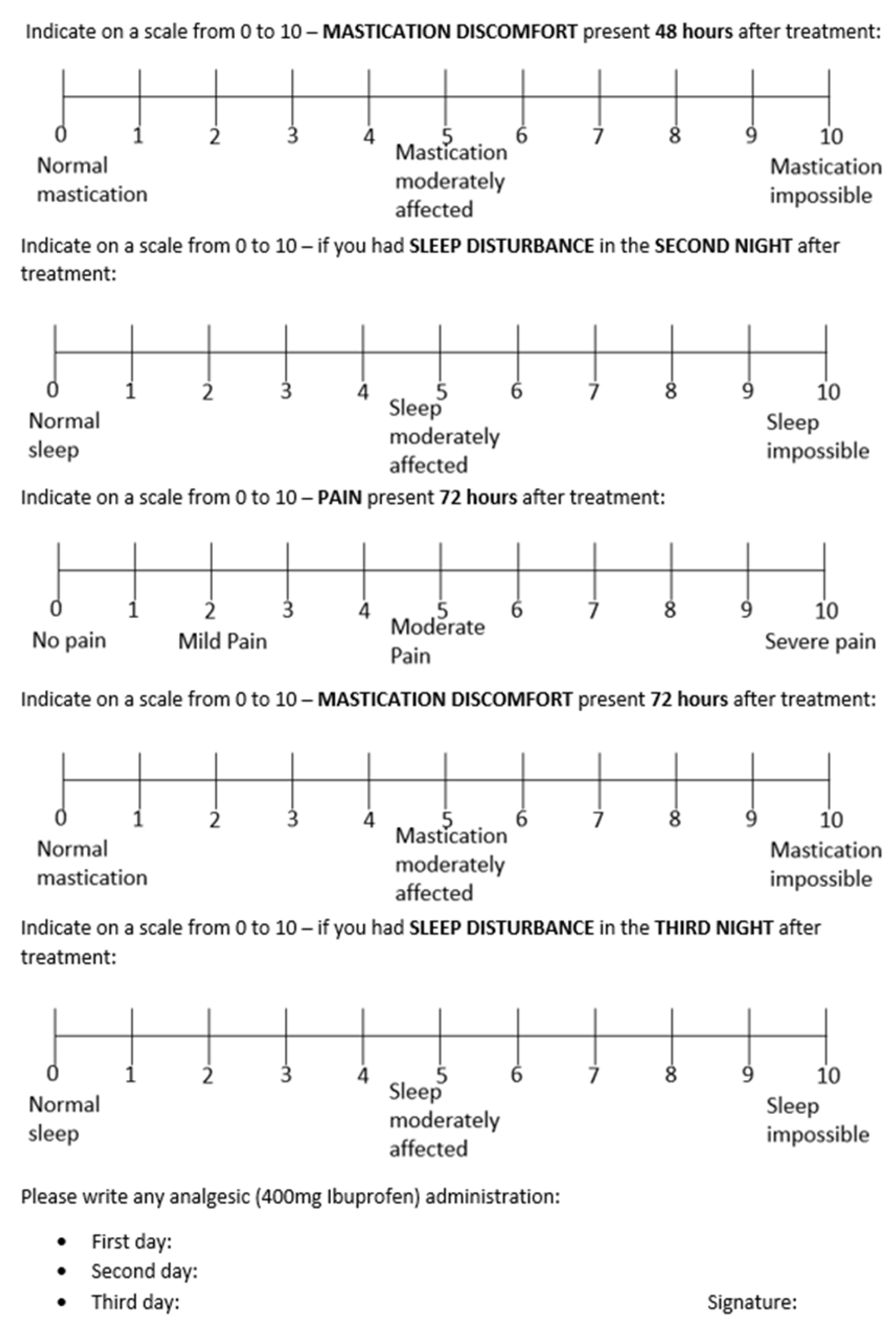

| Setting | 5 | Describe the setting, locations, and relevant dates, including periods of recruitment, exposure, follow-up, and data collection | Patient selection 2nd ;3rd paragraph; Figure 1 |

| Participants | 6 | (a) Give the eligibility criteria, and the sources and methods of selection of participants. Describe methods of follow-up | Patient selection – 2nd paragraph; POP assessment form |

| (b) For matched studies, give matching criteria and number of exposed and unexposed | n/a | ||

| Variables | 7 | Clearly define all outcomes, exposures, predictors, potential confounders, and effect modifiers. Give diagnostic criteria, if applicable | First visit; POP assessment form |

| Data sources/ measurement | 8* | For each variable of interest, give sources of data and details of methods of assessment (measurement). Describe comparability of assessment methods if there is more than one group | POP assessment form |

| Bias | 9 | Describe any efforts to address potential sources of bias | Patient selection – 3rd paragraph; Second visit; POP assessment form |

| Study size | 10 | Explain how the study size was arrived at | Patient selection – 3rd paragraph |

| Quantitative variables | 11 | Explain how quantitative variables were handled in the analyses. If applicable, describe which groupings were chosen and why | Statistical analysis |

| Statistical methods | 12 | (a) Describe all statistical methods, including those used to control for confounding | Statistical analysis |

| (b) Describe any methods used to examine subgroups and interactions | Statistical analysis | ||

| (c) Explain how missing data were addressed | No missing data | ||

| (d) If applicable, explain how loss to follow-up was addressed | Results – 1st paragraph | ||

| (e) Describe any sensitivity analyses | None (low N) | ||

| Results | |||

| Participants | 13* | (a) Report numbers of individuals at each stage of study—eg numbers potentially eligible, examined for eligibility, confirmed eligible, included in the study, completing follow-up, and analysed | Figure 1 |

| (b) Give reasons for non-participation at each stage | Results – 1st paragraph | ||

| (c) Consider use of a flow diagram | Figure 1 | ||

| Descriptive data | 14* | (a) Give characteristics of study participants (eg demographic, clinical, social) and information on exposures and potential confounders | Table 2 |

| (b) Indicate number of participants with missing data for each variable of interest | Results – 1st paragraph | ||

| (c) Summarise follow-up time (eg, average and total amount) | Figure 1 | ||

| Outcome data | 15* | Report numbers of outcome events or summary measures over time | Results – 2nd paragraph |

| Main results | 16 | (a) Give unadjusted estimates and, if applicable, confounder-adjusted estimates and their precision (eg, 95% confidence interval). Make clear which confounders were adjusted for and why they were included | No confounders/control variables. |

| (b) Report category boundaries when continuous variables were categorized | Results – 2nd paragraph | ||

| (c) If relevant, consider translating estimates of relative risk into absolute risk for a meaningful time period | |||

| Other analyses | 17 | Report other analyses done—eg analyses of subgroups and interactions, and sensitivity analyses | Patient selection – 3rd paragraph Power analysis |

| Discussion | |||

| Key results | 18 | Summarise key results with reference to study objectives | 1st paragraph; 5th paragraph |

| Limitations | 19 | Discuss limitations of the study, taking into account sources of potential bias or imprecision. Discuss both direction and magnitude of any potential bias | 13th paragraph |

| Interpretation | 20 | Give a cautious overall interpretation of results considering objectives, limitations, multiplicity of analyses, results from similar studies, and other relevant evidence | 1st paragraph; Conclusions |

| Generalisability | 21 | Discuss the generalisability (external validity) of the study results | Discussions – 13th paragraph; 14th paragraph |

| Other information | |||

| Funding | 22 | Give the source of funding and the role of the funders for the present study and, if applicable, for the original study on which the present article is based | None |

References

- Quality Guidelines for Endodontic Treatment: Consensus Report of the European Society of Endodontology - - 2006 - International Endodontic Journal - Wiley Online Library Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2591.2006.01180.x (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Baaij, A.; Kruse, C.; Whitworth, J.; Jarad, F. EUROPEAN SOCIETY OF ENDODONTOLOGY Undergraduate Curriculum Guidelines for Endodontology. International Endodontic Journal 2024, 57, 982–995. [CrossRef]

- Sathorn, C.; Parashos, P.; Messer, H. The Prevalence of Postoperative Pain and Flare-up in Single- and Multiple-Visit Endodontic Treatment: A Systematic Review. International Endodontic Journal 2008, 41, 91–99. [CrossRef]

- Law, A.S.; Nixdorf, D.R.; Aguirre, A.M.; Reams, G.J.; Tortomasi, A.J.; Manne, B.D.; Harris, D.R. Predicting Severe Pain after Root Canal Therapy in the National Dental PBRN. J Dent Res 2015, 94, 37S-43S. [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, J.F. Microbial Causes of Endodontic Flare-Ups. Int Endod J 2003, 36, 453–463. [CrossRef]

- Pasqualini, D.; Mollo, L.; Scotti, N.; Cantatore, G.; Castellucci, A.; Migliaretti, G.; Berutti, E. Postoperative Pain after Manual and Mechanical Glide Path: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of Endodontics 2012, 38, 32–36. [CrossRef]

- Pak, J.G.; White, S.N. Pain Prevalence and Severity before, during, and after Root Canal Treatment: A Systematic Review. Journal of Endodontics 2011, 37, 429–438. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xu, P.; Ren, L.; Dong, G.; Ye, L. Comparison of Post-obturation Pain Experience Following One-visit and Two-visit Root Canal Treatment on Teeth with Vital Pulps: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int Endodontic J 2010, 43, 692–697. [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.-E.; Kim, Y.; Kim, B.S. Influence of Preoperative Mechanical Allodynia on Predicting Postoperative Pain after Root Canal Treatment: A Prospective Clinical Study. Journal of Endodontics 2021, 47, 770-778.e1. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Sharma, R.; Sharma, M.; Jain, S.; Rai, A.; Gupta, S. Endodontic Flare-Ups: An Update. Cureus 2023, 15, e41438. [CrossRef]

- Parirokh, M.; Rekabi, A.R.; Ashouri, R.; Nakhaee, N.; Abbott, P.V.; Gorjestani, H. Effect of Occlusal Reduction on Postoperative Pain in Teeth with Irreversible Pulpitis and Mild Tenderness to Percussion. Journal of Endodontics 2013, 39, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Arias, A.; de la Macorra, J.C.; Hidalgo, J.J.; Azabal, M. Predictive Models of Pain Following Root Canal Treatment: A Prospective Clinical Study. Int Endod J 2013, 46, 784–793. [CrossRef]

- Schwendicke, F.; Göstemeyer, G. Single-Visit or Multiple-Visit Root Canal Treatment: Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis and Trial Sequential Analysis. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e013115. [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.W.; Zhang, C.; Chu, C.-H. A Systematic Review of Nonsurgical Single-Visit versus Multiple-Visit Endodontic Treatment. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent 2014, 6, 45–56. [CrossRef]

- Mergoni, G.; Ganim, M.; Lodi, G.; Figini, L.; Gagliani, M.; Manfredi, M. Single versus Multiple Visits for Endodontic Treatment of Permanent Teeth - Mergoni, G - 2022 | Cochrane Library.

- Ince, B.; Ercan, E.; Dalli, M.; Dulgergil, C.T.; Zorba, Y.O.; Colak, H. Incidence of Postoperative Pain after Single- and Multi-Visit Endodontic Treatment in Teeth with Vital and Non-Vital Pulp. European Journal of Dentistry 2019, 03, 273–279. [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Ezpeleta, L.-O.; Gasco-Garcia, C.; Castellanos-Cosano, L.; Martín-González, J.; López-Frías, F.-J.; Segura-Egea, J.-J. Postoperative Pain after One-Visit Root-Canal Treatment on Teeth with Vital Pulps: Comparison of Three Different Obturation Techniques. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2012, 17, e721-727. [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.M.C.; Martins, A.C.R.; Reis, A.; de Geus, J.L. Effect of Endodontic Sealer on Postoperative Pain: A Network Meta-Analysis. Restor Dent Endod 2023, 48, e5. [CrossRef]

- Nagendrababu, V.; Gutmann, J.L. Factors Associated with Postobturation Pain Following Single-Visit Nonsurgical Root Canal Treatment: A Systematic Review. Quintessence Int 2017, 48, 193–208. [CrossRef]

- Alí, A.; Olivieri, J.G.; Duran-Sindreu, F.; Abella, F.; Roig, M.; García-Font, M. Influence of Preoperative Pain Intensity on Postoperative Pain after Root Canal Treatment: A Prospective Clinical Study. Journal of Dentistry 2016, 45, 39–42. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.-H.; Kushnir, L.; Kohli, M.; Karabucak, B. Comparing the Incidence of Postoperative Pain after Root Canal Filling with Warm Vertical Obturation with Resin-Based Sealer and Sealer-Based Obturation with Calcium Silicate-Based Sealer: A Prospective Clinical Trial. Clin Oral Investig 2021, 25, 5033–5042. [CrossRef]

- Rosen, E.; Goldberger, T.; Taschieri, S.; Del Fabbro, M.; Corbella, S.; Tsesis, I. The Prognosis of Altered Sensation after Extrusion of Root Canal Filling Materials: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J Endod 2016, 42, 873–879. [CrossRef]

- Jaha, H.S. Hydraulic (Single Cone) Versus Thermogenic (Warm Vertical Compaction) Obturation Techniques: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e62925. [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Tian, J.; Huang, X.; Lei, S.; Cai, Y.; Xu, Z.; Wei, X. A Comparative Study of Dentinal Tubule Penetration and the Retreatability of EndoSequence BC Sealer HiFlow, iRoot SP, and AH Plus with Different Obturation Techniques. Clin Oral Invest 2021, 25, 4163–4173. [CrossRef]

- Moccia, E.; Carpegna, G.; Dell’Acqua, A.; Alovisi, M.; Comba, A.; Pasqualini, D.; Berutti, E. Evaluation of the Root Canal Tridimensional Filling with Warm Vertical Condensation, Carrier-Based Technique and Single Cone with Bioceramic Sealer: A Micro-CT Study. Giornale Italiano di Endodonzia 2020, 34. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, G.C.; Pinheiro, L.S.; Nunes, J.S.; de Almeida Mendes, R.; Schuster, C.D.; Soares, R.G.; Kopper, P.M.P.; de Figueiredo, J.A.P.; Grecca, F.S. Evaluation of the Biological and Physicochemical Properties of Calcium Silicate-Based and Epoxy Resin-Based Root Canal Sealers. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2022, 110, 1344–1353. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, L.H.S.; Moraes, R.R.; Morgental, R.D.; Pappen, F.G. Are Premixed Calcium Silicate–Based Endodontic Sealers Comparable to Conventional Materials? A Systematic Review of In Vitro Studies. Journal of Endodontics 2017, 43, 527–535. [CrossRef]

- Chybowski, E.A.; Glickman, G.N.; Patel, Y.; Fleury, A.; Solomon, E.; He, J. Clinical Outcome of Non-Surgical Root Canal Treatment Using a Single-Cone Technique with Endosequence Bioceramic Sealer: A Retrospective Analysis. Journal of Endodontics 2018, 44, 941–945. [CrossRef]

- Donnermeyer, D.; Dammaschke, T.; Schäfer, E. Hydraulic Calcium Silicate-Based Sealers: A Game Changer in Root Canal Obturation? 2020, 197–203.

- Rodríguez-Lozano, F.J.; López-García, S.; García-Bernal, D.; Tomás-Catalá, C.J.; Santos, J.M.; Llena, C.; Lozano, A.; Murcia, L.; Forner, L. Chemical Composition and Bioactivity Potential of the New Endosequence BC Sealer Formulation HiFlow. Int Endod J 2020, 53, 1216–1228. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Haapasalo, M.; Mobuchon, C.; Li, X.; Ma, J.; Shen, Y. Cytotoxicity and the Effect of Temperature on Physical Properties and Chemical Composition of a New Calcium Silicate–Based Root Canal Sealer. Journal of Endodontics 2020, 46, 531–538. [CrossRef]

- Mekhdieva, E.; Del Fabbro, M.; Alovisi, M.; Comba, A.; Scotti, N.; Tumedei, M.; Carossa, M.; Berutti, E.; Pasqualini, D. Postoperative Pain Following Root Canal Filling with Bioceramic vs. Traditional Filling Techniques: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Clin Med 2021, 10, 4509. [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.S.G.; Lim, K.C.; Lui, J.N.; Lai, W.M.C.; Yu, V.S.H. Postobturation Pain Associated with Tricalcium Silicate and Resin-Based Sealer Techniques: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Endod 2021, 47, 169–177. [CrossRef]

- Graunaite, I.; Skucaite, N.; Lodiene, G.; Agentiene, I.; Machiulskiene, V. Effect of Resin-Based and Bioceramic Root Canal Sealers on Postoperative Pain: A Split-Mouth Randomized Controlled Trial. J Endod 2018, 44, 689–693. [CrossRef]

- Aslan, T.; Dönmez Özkan, H. The Effect of Two Calcium Silicate-Based and One Epoxy Resin-Based Root Canal Sealer on Postoperative Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int Endod J 2021, 54, 190–197. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, B.; Coelho, M.S.; Bueno, C.E. da S.; Fontana, C.E.; Martin, A.S.D.; Rocha, D.G.P. Assessment of Extrusion and Postoperative Pain of a Bioceramic and Resin-Based Root Canal Sealer. Eur J Dent 2019, 13, 343–348. [CrossRef]

- García-Font, M.; Duran-Sindreu, F.; Calvo, C.; Basilio, J.; Abella, F.; Ali, A.; Roig, M.; Olivieri, J.-G. Comparison of Postoperative Pain after Root Canal Treatment Using Reciprocating Instruments Based on Operator’s Experience: A Prospective Clinical Study. J Clin Exp Dent 2017, 9, e869–e874. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, P.S.; Ferreira, M.C.; Paula, N.G.N.; Loguercio, A.D.; Grazziotin-Soares, R.; da Silva, G.R.; da Mata, H.C.S.; Bauer, J.; Carvalho, C.N. Postoperative Pain Following Root Canal Instrumentation Using ProTaper Next or Reciproc in Asymptomatic Molars: A Randomized Controlled Single-Blind Clinical Trial. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2022, 11, 3816. [CrossRef]

- STROBE Available online: https://www.strobe-statement.org/ (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Endodontic Diagnosis Clinical Newsletter. American Association of Endodontists.

- AAE Endodontic Case Difficulty Assessment Form and Guidelines.

- Buchanan, L.S. Management of the Curved Root Canal. J Calif Dent Assoc 1989, 17, 18–25, 27.

- Dillon, J.S.; Amita, null; Gill, B. To Determine Whether the First File to Bind at the Working Length Corresponds to the Apical Diameter in Roots with Apical Curvatures Both before and after Preflaring. J Conserv Dent 2012, 15, 363–366. [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, L.S. Continuous Wave of Condensation Technique. Endod Prac 1998, 1, 7–10, 13–16, 18 passim.

- Sirintawat, N.; Sawang, K.; Chaiyasamut, T.; Wongsirichat, N. Pain Measurement in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. Journal of Dental Anesthesia and Pain Medicine 2017, 17, 253–263. [CrossRef]

- Demenech, L.S.; Freitas, J.V. de; Tomazinho, F.S.F.; Baratto-Filho, F.; Gabardo, M.C.L. Postoperative Pain after Endodontic Treatment under Irrigation with 8.25% Sodium Hypochlorite and Other Solutions: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of Endodontics 2021, 47, 696–704. [CrossRef]

- Ng, Y.-L.; Glennon, J.P.; Setchell, D.J.; Gulabivala, K. Prevalence of and Factors Affecting Post-Obturation Pain in Patients Undergoing Root Canal Treatment. International Endodontic Journal 2004, 37, 381–391. [CrossRef]

- Drumond, J.P.S.C.; Maeda, W.; Nascimento, W.M.; Campos, D. de L.; Prado, M.C.; de-Jesus-Soares, A.; Frozoni, M. Comparison of Postobturation Pain Experience after Apical Extrusion of Calcium Silicate– and Resin–Based Root Canal Sealers. Journal of Endodontics 2021, 47, 1278–1284. [CrossRef]

- Olcay, K.; Eyüboglu, T.F.; Özcan, M. Clinical Outcomes of Non-Surgical Multiple-Visit Root Canal Retreatment: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Odontology 2019, 107, 536–545. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, G.P.; Delbem, A.C.B.; Gomes, J.M.L.; Lemos, C.A.A.; Pellizzer, E.P. Postoperative Pain in Endodontic Retreatment of One Visit versus Multiple Visits: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Clin Oral Invest 2021, 25, 455–468. [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, L.E.C.D.P. Fusobacterium Nucleatum in Endodontic Flare-Ups. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology 2002, 93, 179–183. [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M.E.H. a. A.; El-Shrief, Y. a. I.; Anous, W.I.O.; Hassan, M.W.; Salamah, F.T.A.; El Boghdadi, R.M.; El-Bayoumi, M. a. A.; Seyam, R.M.; Abd-El-Kader, K.G.; Amin, S. a. W. Postoperative Pain Following Endodontic Irrigation Using 1.3% versus 5.25% Sodium Hypochlorite in Mandibular Molars with Necrotic Pulps: A Randomized Double-Blind Clinical Trial. International Endodontic Journal 2020, 53, 154–166. [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.-M.; Su, Z.; Hou, B.-X. Post Endodontic Pain Following Single-Visit Root Canal Preparation with Rotary vs Reciprocating Instruments: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. BMC Oral Health 2017, 17, 86. [CrossRef]

- Segura-Egea, J.J.; Cisneros-Cabello, R.; Llamas-Carreras, J.M.; Velasco-Ortega, E. Pain Associated with Root Canal Treatment. International Endodontic Journal 2009, 42, 614–620. [CrossRef]

- Arias, A.; Azabal, M.; Hidalgo, J.J.; De La Macorra, J.C. Relationship between Postendodontic Pain, Tooth Diagnostic Factors, and Apical Patency. Journal of Endodontics 2009, 35, 189–192. [CrossRef]

- Gotler, M.; Bar-Gil, B.; Ashkenazi, M. Postoperative Pain after Root Canal Treatment: A Prospective Cohort Study. International Journal of Dentistry 2012, 2012, 310467. [CrossRef]

- Patro, S.; Meto, A.; Mohanty, A.; Chopra, V.; Miglani, S.; Das, A.; Luke, A.M.; Hadi, D.A.; Meto, A.; Fiorillo, L.; et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Pulp Vitality Tests and Pulp Sensibility Tests for Assessing Pulpal Health in Permanent Teeth: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 9599. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.; Kurtz, E.; Kohli, M. Incidence and Factors Related to Flare-Ups in a Graduate Endodontic Programme. International Endodontic Journal 2009, 42, 99–104. [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J.G.; Liesinger, A.W. Factors Associated with Endodontic Posttreatment Pain. Journal of Endodontics 1993, 19, 573–575. [CrossRef]

- Mc Cullagh, J.J.P.; Setchell, D.J.; Gulabivala, K.; Hussey, D.L.; Biagioni, P.; Lamey, P.-J.; Bailey, G. A Comparison of Thermocouple and Infrared Thermographic Analysis of Temperature Rise on the Root Surface during the Continuous Wave of Condensation Technique. International Endodontic Journal 2000, 33, 326–332. [CrossRef]

- Zamparini, F.; Lenzi, J.; Duncan, H.F.; Spinelli, A.; Gandolfi, M.G.; Prati, C. The Efficacy of Premixed Bioceramic Sealers versus Standard Sealers on Root Canal Treatment Outcome, Extrusion Rate and Post-Obturation Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int Endod J 2024, 57, 1021–1042. [CrossRef]

- Walton, R.; Fouad, A. Endodontic Interappointment Flare-Ups: A Prospective Study of Incidence and Related Factors. J Endod 1992, 18, 172–177. [CrossRef]

- Glennon, J.P.; Ng, Y.-L.; Setchell, D.J.; Gulabivala, K. Prevalence of and Factors Affecting Postpreparation Pain in Patients Undergoing Two-Visit Root Canal Treatment. Int Endod J 2004, 37, 29–37. [CrossRef]

- Llena, C.; Nicolescu, T.; Perez, S.; Gonzalez de Pereda, S.; Gonzalez, A.; Alarcon, I.; Monzo, A.; Sanz, J.L.; Melo, M.; Forner, L. Outcome of Root Canal Treatments Provided by Endodontic Postgraduate Students. A Retrospective Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2020, 9, 1994. [CrossRef]

- Bielewicz, J.; Daniluk, B.; Kamieniak, P. VAS and NRS, Same or Different? Are Visual Analog Scale Values and Numerical Rating Scale Equally Viable Tools for Assessing Patients after Microdiscectomy? Pain Res Manag 2022, 2022, 5337483. [CrossRef]

- Hawker, G.A.; Mian, S.; Kendzerska, T.; French, M. Measures of Adult Pain: Visual Analog Scale for Pain (VAS Pain), Numeric Rating Scale for Pain (NRS Pain), McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), Chronic Pain Grade Scale (CPGS), Short Form-36 Bodily Pain Scale (SF-36 BPS), and Measure of Intermittent and Constant Osteoarthritis Pain (ICOAP). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011, 63 Suppl 11, S240-252. [CrossRef]

- Pak, J.G.; White, S.N. Pain Prevalence and Severity before, during, and after Root Canal Treatment: A Systematic Review. J Endod 2011, 37, 429–438. [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, F.; Yazdi, K.; Mahabadi, A.M.; Modaresi, S.J.; Hamzeheil, Z. Effect of Premedication with Indomethacin and Ibuprofen on Postoperative Endodontic Pain: A Clinical Trial. Iran Endod J 2016, 11, 57–62. [CrossRef]

- Milani, A.S.; Froughreyhani, M.; Taghiloo, H.; Nouroloyouni, A.; Jafarabadi, M.A. The Effect of Antibiotic Use on Endodontic Post-Operative Pain and Flare-up Rate: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Evidence-Based Dentistry (EBD) 2022. [CrossRef]

| Factor | PGS | ES | Total | P a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age¹ | 42.3 ± 17.2 | 42.2 ± 15.3 | 42.3 ± 16.7 | 0.980 | |

| Gender | Female | 33 | 34 | 67 | 0.940 |

| Male | 18 | 18 | 36 | ||

| Tooth type | Anterior | 15 | 7 | 22 | 0.100 |

| Premolar | 10 | 9 | 19 | ||

| Molar | 26 | 36 | 62 | ||

| AAE Difficulty | Minimum | 19 | 14 | 33 | 0.500 |

| Moderate | 14 | 15 | 29 | ||

| High | 18 | 23 | 41 | ||

| Pulp status | Vital (healthy) | 8 | 8 | 16 | 0.990 |

| Pulpitis | 25 | 25 | 50 | ||

| Necrosis | 18 | 19 | 37 | ||

| Percussion | Positive | 15 | 20 | 35 | 0.330 |

| Negative | 36 | 32 | 68 | ||

| LEO | No | 34 | 34 | 68 | 0.700 |

| Leo < 2 mm | 9 | 12 | 10 | ||

| Leo > 2 mm | 8 | 6 | 14 | ||

| Extrusion | Yes | 11 | 20 | 31 | 0.060 |

| No | 40 | 32 | 72 | ||

| Obturation quality | Correct | 39 | 46 | 85 | 0.280 |

| Adequate | 8 | 3 | 11 | ||

| Short | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Overfilling | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| POP | PGS | ES | total | P1,a | |

| Instrumentation phase | No | 17 (34.0%) | 16 (30.7%) | 33 (32.3%) | 0.946 |

| Yes | 34 (66.0%) | 36 (69.2%) | 70 (67.6%) | ||

| Obturation phase | No | 23 (46.0%) | 30 (57.6%) | 53 (51.9%) | 0.279 |

| Yes | 28 (54.0%) | 22 (42.3%) | 50 (48.0%) | ||

| P2,a | 0.311 | 0.010 |

| Instrumentation phase | Obturation phase | ||

| POP | 24 h vs. 48 h | 1.03* | 0.85* |

| 24 h vs. 72 h | 1.46* | 1.13* | |

| 48 h vs. 72 h | 0.43*** | 0.27** | |

| Mastication discomfort | 24 h vs. 48 h | 1.06* | 0.71* |

| 24 h vs. 72 h | 1.48* | 1.14* | |

| 48 h vs. 72 h | 0.42*** | 0.43* | |

| Sleep disturbance | 24 h vs. 48 h | 0.08 | 0.04 |

| 24 h vs. 72 h | 0.19 | 0.12 | |

| 48 h vs. 72 h | 0.12 | 0.08 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).