1. Introduction

Huntington’s disease (HD) is a debilitating neurodegenerative genetic disorder caused by the expansion of polyglutamine (polyQ) repeat in the Huntingtin (Htt) gene[

1,

2,

3]. In particular, this expansion occurs in the coding region of the first exon of the Htt gene (Htt Exon-1). In physiological conditions, the polyQ region consists of a variable number of glutamines, from 9 to 34 residues, while under pathological conditions, the polyQ tract is longer than 35 residues of glutamine. The resultant pathological protein, mutant Htt (mHtt), undergoes misfolding and aggregation in neural cells, particularly affecting neurons in the striatum and cortex, leading to neuronal toxicity and cellular death[

4].

Recent studies suggest that mHtt exhibits prion-like properties[

5,

6,

7], capable of templating its misfolded state onto normal Htt and spreading between cells. In this respect, prion-like propagation has emerged as a unifying theory to explain the progressive and spatially distributed pathology observed in HD[

6,

8,

9,

10] and other neurodegenerative diseases. The first evidence of the prion-like propagation of mHtt originates from studies in vitro. For example, Ren et al showed that mHtt-expressing cells release aggregates that can be internalized by neighboring cells, inducing further aggregation of endogenous Htt. Seeding and templating activity in vitro studies with recombinant mHtt fibrils have shown that they can seed the aggregation of wild-type Htt. This templated misfolding is a hallmark of prion-like behavior and further supports the propagation hypothesis. Moreover, in vivo evidence was also obtained in animal models expressing mHtt in localized brain regions, which show the spreading of aggregates to distant areas over time, indicating a non-cell-autonomous mechanism of pathology. This supports the idea that mHtt can propagate through neural circuits[

10].

Prion-like propagation of mHtt may explain the sequential and regional development of neuropathology in HD. It also raises the possibility that early focal aggregation events could trigger widespread neurodegeneration. Mechanistically, several pathways have been proposed to mediate the intercellular spread of mHtt: direct cell-to-cell contact and tunneling nanotubes[

11,

12,

13], endocytosis of released aggregates, transport within exosomes[

14], and other extracellular vesicles.

In previous work, we discovered that Htt Exon-1 showed a propensity to form Coiled-Coil (Cc) structures[

15]. A coiled-coil domain is a structural motif where 2–7 alpha-helices twist around each other[

16,

17]. This facilitates protein-protein interactions by promoting oligomerization and assembling protein monomers into complexes[

18,

19]. We found that Cc motifs promote oligomerization and self-association of mHtt, increase the likelihood of forming amyloid-like aggregates, and interact with other proteins through these domains, often sequestering essential cellular components[

15]. Our initial findings were confirmed by other groups[

20] and extended to other polyQ rich proteins[

21]. Interestingly, Cc domains are present in wide variety of proteins, and are often associated with membrane interactions[

22,

23]. Cc are also present in several proteins involved in the formation and release of exosome, such as Alix and Tsg101[

24]. Thus, we hypothesized that Htt Cc structures might promote the aberrant interaction of mHtt with these proteins and possibly contribute to the exosome-mediated intercellular propagation of mHtt. In the present study, we tested our hypothesis using human cell lines expressing Htt proteins with different probabilities to acquire Cc fold. We assessed their ability to interact with Alix, to be released from transfected cells, and to be internalized by recipient cells using a combination of techniques (western blot, FACS, flow cytometry and confocal imaging). We found that Cc structures are critically involved in all these processes. Therefore, this study contributes meaningfully to the expanding literature on prion-like spread by identifying a structural determinant that regulates multiple steps in the life cycle of pathogenic mHtt.

2. Results

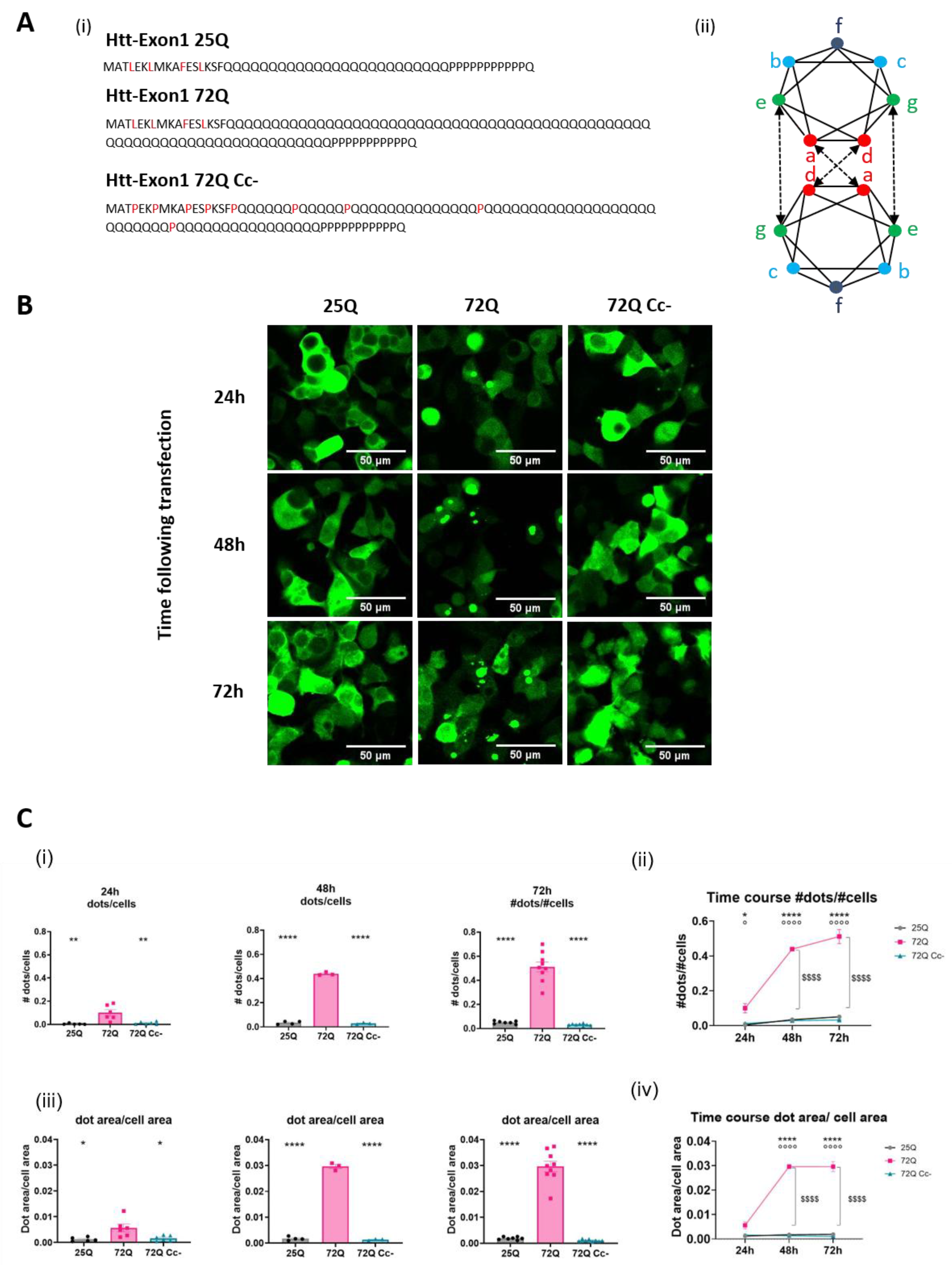

2.1. PolyQ Expanded Huntingtin Achieves the Aggregation Plateau at 48 Hours Following Transfection

We previously reported that overexpression of mHtt fragments in HEK293 for 96 hours induced the formation of large, toxic aggregates[

15]. Here, we performed a time course analysis to better understand the kinetics of mHtt aggregation. We transfected HEK293 cells with constructs carrying Htt Exon-1 fragments (

Figure 1A i). We used Htt Exon-1 with 25Q flagged with GFP (25Q), Htt Exon-1 with 72Q flagged with GFP (72Q) or Htt Exon-1 with 72Q coiled-coil–defective (Cc-) mutant, in which residues in a/d position (

Figure 1A (ii)) have been substituted with prolines[

25]. 72Q forms cytoplasmic aggregates which are visible starting at 24 hours after transfection, while the 72Q Cc- has a diffused distribution, like the physiologic construct 25Q (

Figure 1B). We quantified: 1) the number of dots (single aggregates) normalized on the number of cells (

Figure 1C (i and ii)), 2) the area occupied by dots normalized on the area of transfected cells (

Figure 1C (iii and (iv)).

We found that 24 hours after transfection, the 72Q protein forms higher number and bigger dots per cell compared to 25Q (

Figure 1C (i, iii)). In cells transfected with 72Q, the number and the size of the dots increase further at 48 and 72 hours after transfection (

Figure 1B, and C). 25Q forms small aggregates with no increase in the number and in the dimension over time. 72Q Cc-, which has a reduced ability to form Cc structures, produces lower number and smaller aggregates compared to 72Q protein, like the 25Q protein did (

Figure 1C). This confirms our previously published data that substitution of specific aminoacidic residues with prolines in 72Q (

Figure 1A) can prevent aggregation of PolyQ-expanded Huntingtin[

15] and establish a kinetic profile of the aggregation of 72Q.

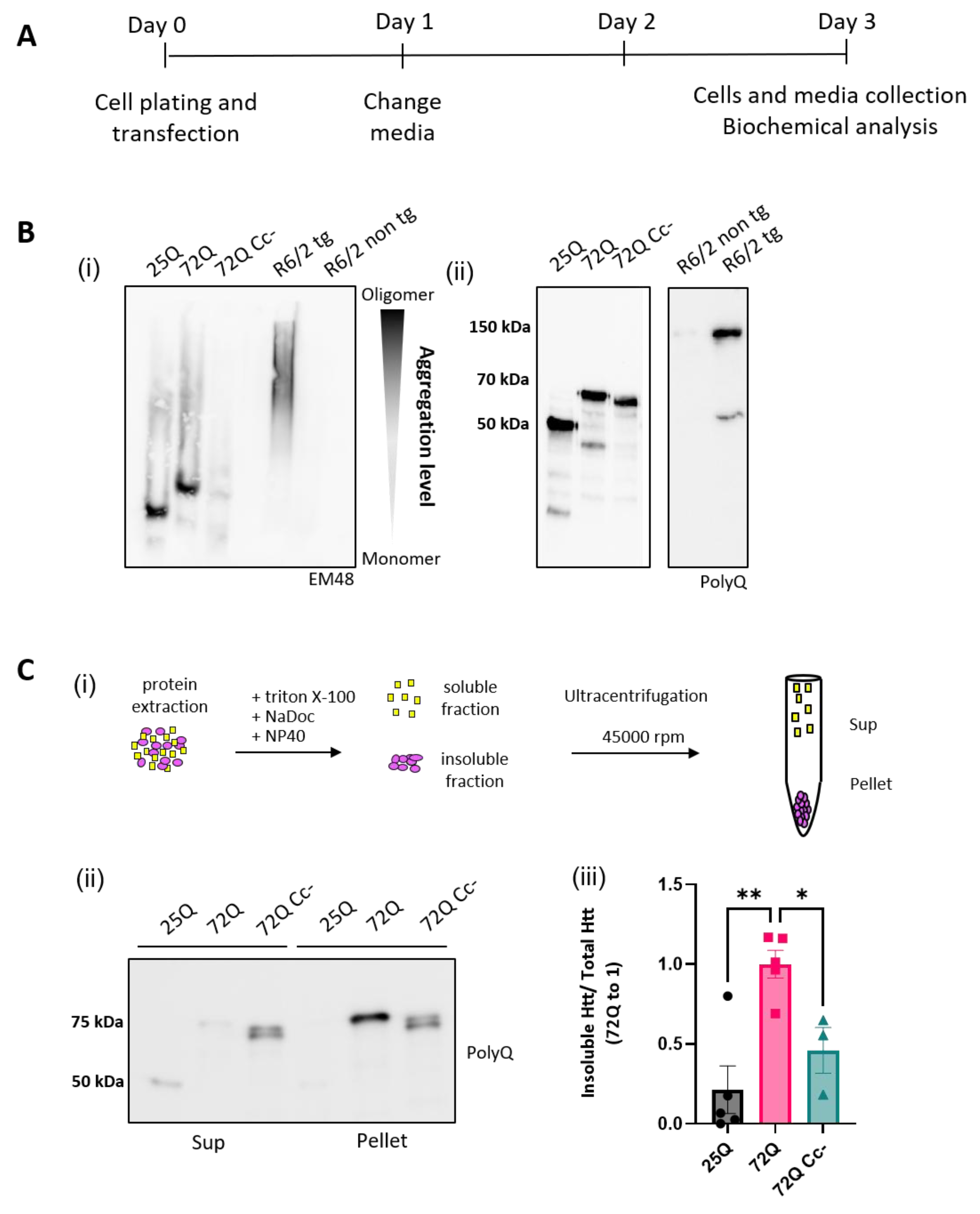

2.2. The Coiled-Coil Structure of Htt Exon-1 Mediates the Formation of Htt Insoluble Oligomers

To biochemically characterize the aggregation of Htt Exon-1 fragments, we performed Semi-Denaturing Detergent Agarose gel electrophoresis (SDD-AGE) on HEK293 lysates 72h after transfection (

Figure 2A). With this technique, polymeric and insoluble proteins can be visualized as high molecular weight species compared to the monomeric protein[

26,

27,

28]. Brain homogenates from 14-week-old B6CBA-R6/2 transgenic mice, carrying 160 CAG repetitions[

29], and their non-transgenic littermates were also analyzed as controls. We found that 72Q protein forms large aggregates, which appear as a smear in the gel, above the expected size of the monomeric protein. This aggregation profile was similar to 160Q Htt expressed by R6/2 transgenic mice (

Figure 2B (i)). 25Q and 72Q Cc- proteins, instead, did not form large aggregates. The difference cannot be explained by a different amount of protein, as equal loading was confirmed in regular SDS-PAGE blots (

Figure 2B (ii)). Aggregated proteins can be insoluble to certain detergents[

15,

26,

28,

30,

31]. This biochemical property can be studied in cell lysates using ultracentrifugation to separate detergent-insoluble aggregates from the soluble species. We collected lysates of HEK293 cells overexpressing Htt variants for 72h treated with nonionic detergents and performed ultracentrifugation experiments (

Figure 2C (i)). We found that 72Q was enriched in the insoluble fraction compared to the soluble one (

Figure 2C (ii)). Instead 25Q and 72Q Cc- mutants displayed opposite pattern with a remarkable reduction of the insoluble fraction. The insolubility was quantified in three independent experiments and like 25Q, the 72Q Cc- showed a significant reduction of protein insolubility compared to 72Q (

Figure 2C (iii)). Thus, the detergent insolubility correlated with Cc propensity, closely paralleling the aggregation phenotypes.

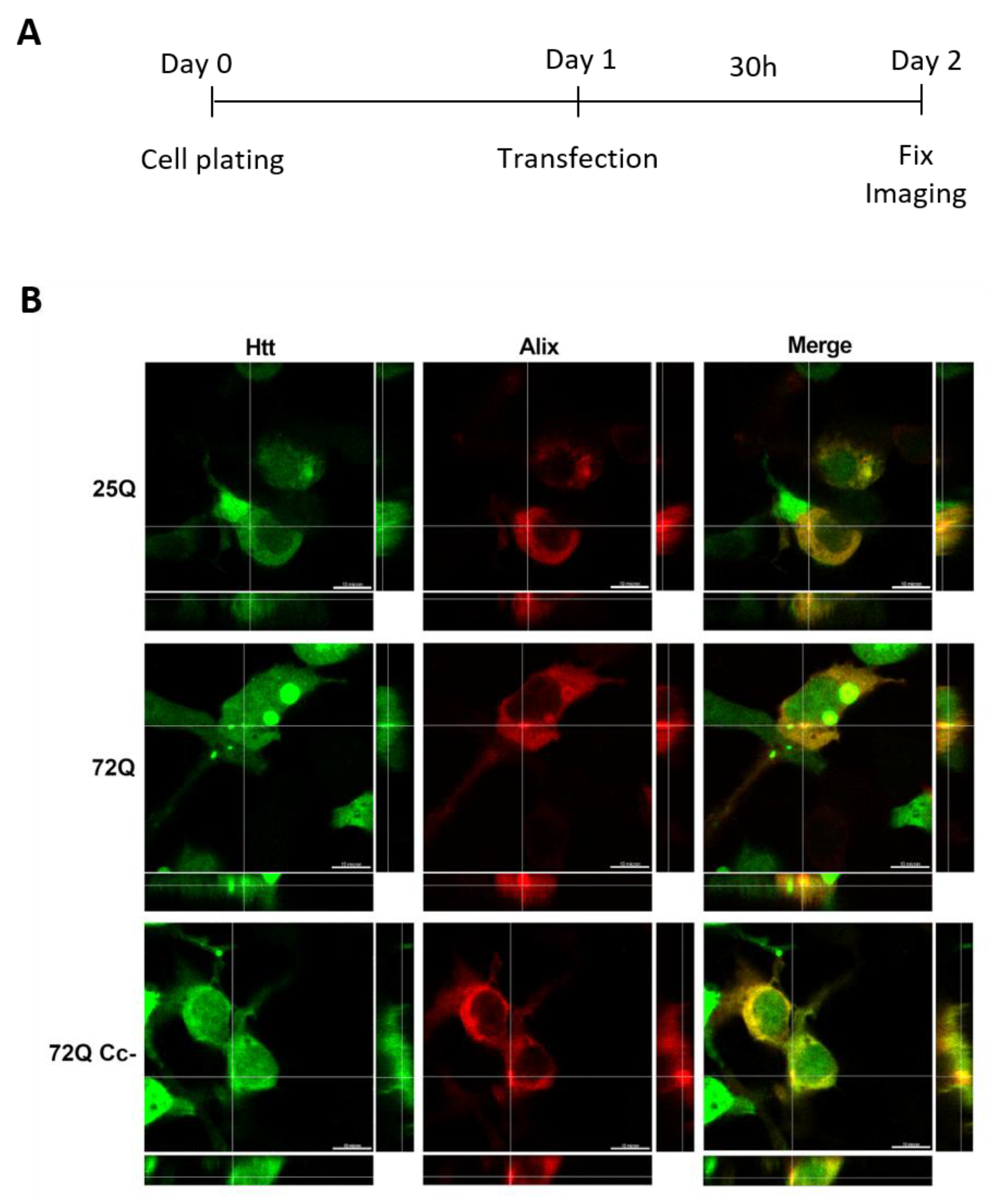

2.3. Htt Exon-1 Colocalizes with Alix

Next, we performed co-transfection experiments to evaluate the co-presence of Htt Exon-1 proteins with an exosomal marker. To do this, we transfected HEK293 cells with plasmids encoding the 25Q, 72Q and 72Q Cc- Htt Exon-1 fragments together with a plasmid encoding Alix, ALG-2 interacting protein X, a cytoplasmic protein present on exosomal membranes[

32,

33,

34](

Figure 3A). We used a plasmid expressing Alix fused with red fluorescent protein (RFP) in the carboxy-terminal portion to visualize it. After 30 hours of transfection, we observed that Alix generally had a diffused distribution but with areas where the signal was more concentrated. In cells transfected with 72Q, we observed a colocalization between Alix and 72Q aggregates as well as in their close proximity, as shown in

Figure 3B. However, when Cc structures are impaired, this phenomenon was reduced. These results suggest that Cc structures may be implicated in the release of Htt, by promoting the interaction with exosome-associated proteins.

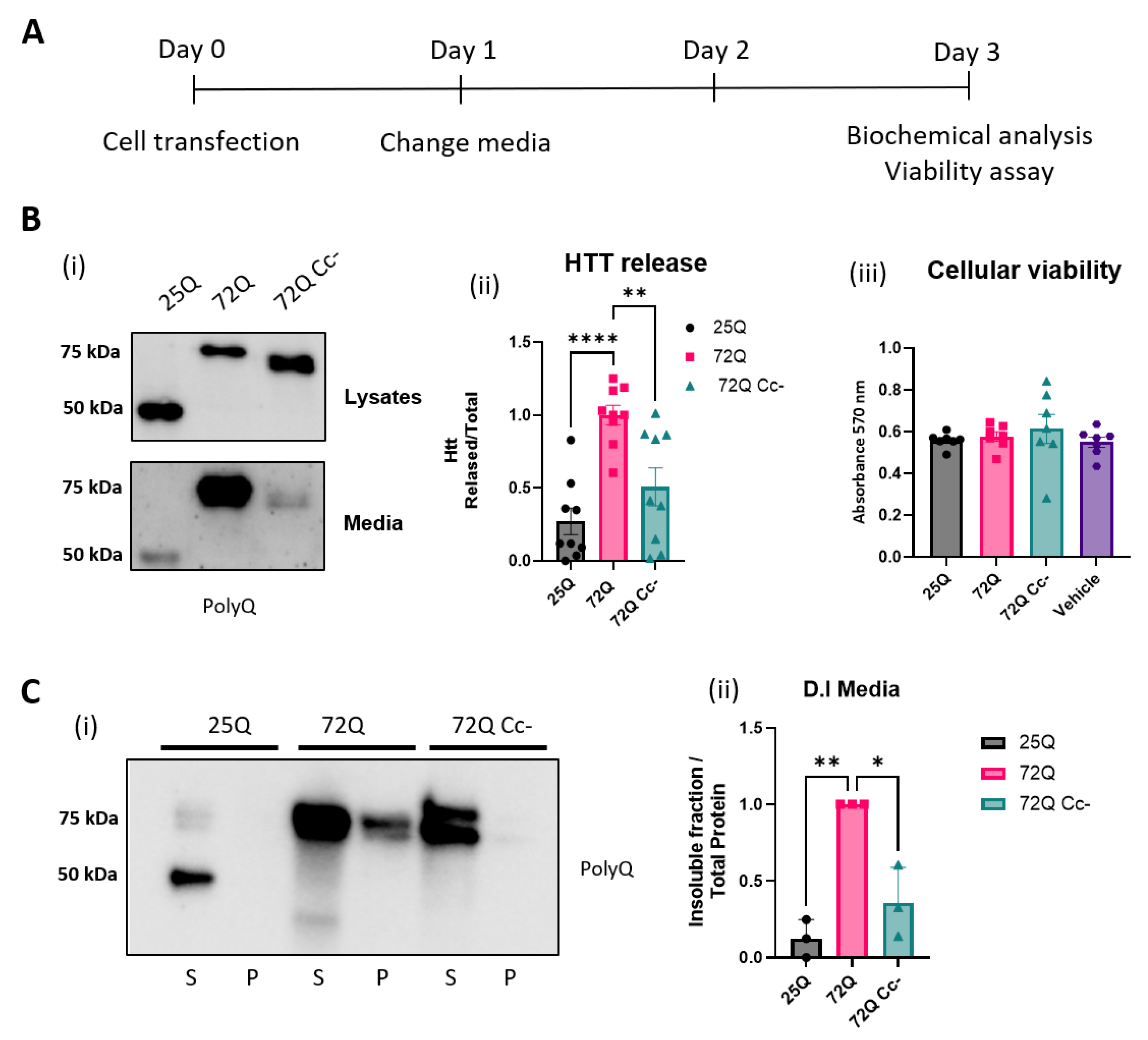

2.4. Htt 72Q Secretion Is Reduced When the Coiled-Coil Structure Is Hampered

Next, we conducted biochemical analyses to determine more directly a possible involvement of Cc structures in the release of Htt proteins in the media of HEK293 transfected cells. As shown in the experimental design (

Figure 4A), 24h after transfection, the media was replaced to remove plasmid DNA. Forty-eight hours later, the media was collected, and the cells were harvested and lysed. Proteins in the media were concentrated and loaded for SDS-PAGE western blot (

Figure 4A) along with protein cellular extracts. We found that all Htt proteins were released in the medium, as shown in

Figure 4B (i). The ratio of released protein to intracellular protein was calculated (

Figure 4B (ii)) and we found that 72Q protein was released significantly more into the media compared to 25Q. We also found that the release of the 72Q Cc- was significantly lower than that of 72Q. Our data, therefore, suggest that the presence of the extended polyQ sequence in mHtt leads to an increase in its release, and that this phenomenon is, at least in part, dependent on the presence of an intact Coiled-coil structure in 72Q.

To exclude that the presence of polyQ tract in the media was due to release from dying cells, we performed an Alamar blue viability assay. We found that expression of the constructs for up to 72h did not induce any evidence of cellular toxicity (

Figure 4B (iii)), confirming that the presence of Htt fragments in the culture media was likely due to an active process of protein release from living cells. Next, we evaluated the solubility of the released proteins by D.I. analysis. Given the difference in the amount of protein released, we balanced the volume of each sample in order to have the same amount of protein for each condition and separated the soluble protein fraction from the insoluble fraction. The soluble and insoluble fractions were analyzed by western blot (

Figure 4C (i)). The quantification of the insoluble Htt showed that 72Q had significantly higher values compared to both 25Q and 72Q Cc- (

Figure 4C (ii)), similarly to what we found in cellular extracts (

Figure 2C (iii)). These results highlight the relevance of Cc structure in determining the biophysical properties of Htt.

2.5. Htt 72Q Uptake is Reduced When the Coiled-Coil Structure is Hampered in Cell-to-Cell Contact Conditions

After we established the role of the Cc structure in the release of the Htt Exon-1 fragment, we investigated the role of Cc in the process of uptake from recipient cells. In the following experiments, we focused our attention on the 72Q and 72Q Cc- defective mutant. We transfected HEK293 cells with Htt constructs (donor cells), and 24 hours later we co-plated them with cells labelled with cell Tracker DiD (recipient cells) (

Figure 5A). We chose this dye because once incorporated into cells, it is retained at least for 72 hours (

Supplementary Figures S1). Donor and recipient cells were sorted by Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) in order to co-plate the same amount of donor and recipient cells in each condition. After 72 hours in co-culture, cells were harvested and fluorescence was assessed by flow cytometry (

Figure 5B (i and ii). Our analysis allowed us to identify four populations: Htt Exon-1 positive (lower-right box in figure), DiD positive (upper-left box in figure), Htt Exon-1 / DiD double positive (upper-right box in figure), and double negative (lower-left box in figure). The double positive cells represent recipient cells, initially labeled only with DiD, that internalized Htt Exon-1 during the 72h co-plating time. We found that both 72Q and 72Q Cc- proteins can be internalized by recipient cells. However, the internalization of the 72Q Cc- protein in recipient cells was significantly reduced compared to 72Q under these conditions (

Figure 5 B (iii)). The results were also confirmed by confocal imaging analyses (

Figure 5 C).

2.6. Coiled-Coil Structure Promotes the Uptake of 72Q Htt Present in the Medium

The greater ability of 72Q to be internalized by recipient cells might be partially due to the fact that it is released in greater amount (

Figure 2) compared to 72Q Cc- defective mutant. To exclude this possible confounding effect, we performed another set of experiments in which recipient cells were exposed to media containing the same amount of 72Q or 72Q Cc (

Figure 6A).

To achieve this, first cells were transfected with 72Q or 72Q Cc. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the media was replaced and cells washed, to remove any possible trace of plasmid DNA. 72 h after media replacement, conditioned media were collected, and the amount of Htt fragments were quantified by western blot. This allowed us to estimate the volume of conditioned media derived from cells transfected with 72Q or 72Q Cc to be used from the different samples before applying them to naive recipient cells. 96 hours after exposure to the media, cells were harvested and fluorescence was assessed by flow cytometry analysis. We found that cells internalized 72Q significantly more than 72 Cc- (

Figure 6B). Confocal analysis (

Figure 6C) further demonstrated the internalization of Htt proteins contained in the media by naïve cells.

These results, together with previous results in cell-to-cell contact conditions, suggest that the Coiled coil structure directly influences both the release of the Htt fragments and the uptake process by recipient cells.

3. Discussion

This study explores the role of polyglutamine (PolyQ) expansion and coiled-coil (Cc) structural elements in the aggregation, secretion, and intercellular transfer of mutant Huntingtin (mHtt) Exon-1 fragments, using HEK293 cells as a model system. The investigation builds on our prior findings that overexpression of mHtt fragments results in large, toxic aggregates forming over time[

15]. In this work, we focused on understanding the kinetics of mHtt aggregation and the molecular determinants driving its spread between cells.

The concept that mutant Huntingtin (mHtt) might spread from cell to cell in a prion-like fashion has gained substantial traction over the past decade[

5,

8,

14], drawing parallels to what has been observed in diseases like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and ALS. Prion-like propagation describes the phenomenon by which misfolded proteins can act as seeds, converting normally folded counterparts into pathological conformers, thereby enabling the spread of pathology across brain regions[

12,

35,

36].

Early foundational work by Ren et al. (2009) and Pecho-Vrieseling et al. (2014) provided the first experimental evidence that mHtt can be transmitted between neurons and from neurons to glia, with consequent toxicity. These studies laid the groundwork for the idea that mHtt aggregates can move beyond their cell of origin, contributing to Huntington’s disease’s progressive, region-specific neurodegeneration.

Subsequent research, such as Pearce et al. (2015)[

37] and Babcock & Gan (2021)[

6], explored potential mechanisms for this intercellular transfer. They proposed pathways involving tunneling nanotubes, synaptic transmission, and, more recently, extracellular vesicle (EV) such as exosomes. Studies by Jeon et al. (2016)[

14] and Trajkovic et al. (2017)[

38] demonstrated that mHtt can be incorporated into exosomes and released into the extracellular space, where it may be taken up by neighboring cells, suggesting a role for the endosomal-lysosomal system in disease spread. Our data on the colocalization between mHtt and Alix, a marker of exosomes, further suggest that mHtt might be released by exosome by interacting with critical components of the exosome machinery.

Our study builds on this body of work by identifying a key structural motif—the coiled-coil (Cc) domain—as a critical mediator of this prion-like behavior[

39]. While many prior studies focused on polyQ length as the primary determinant of aggregation and toxicity, our work adds a new layer by showing that the Cc structure actively facilitates aggregation, secretion, and uptake of mHtt. This structural insight refines our understanding of what makes particular Htt species more prone to propagation.

Importantly, this study uses a Cc-deficient mutant of Htt-72Q to show that disruption of this domain impairs nearly every step of the prion-like process: aggregation, association with exosomal machinery (via ALIX), secretion into the medium, and uptake by neighboring cells. The use of both cell-contact and conditioned media experiments confirms that the Cc motif enhances intracellular aggregation and functions as a facilitator for efficient intercellular trafficking.

This ties in with growing interest in the biophysical properties of aggregating proteins, such as their ability to form specific interaction domains[

19,

20,

21,

40], undergo phase separation[

41,

42], or hijack vesicular transport systems. For instance, similar motifs have been implicated in tau and α-synuclein propagation. Thus, this study positions mHtt—and specifically its Cc structure—within the broader framework of molecular features driving pathogenic spread.

These findings are highly relevant from a therapeutic standpoint. Much like work targeting seeding and spread in Alzheimer’s (anti-tau or anti-Aβ antibodies), this research opens up the possibility that disrupting the Cc structure might mitigate the cell-to-cell transmission of mHtt[

43]. While earlier strategies focused on silencing or degrading the mutant transcript, this work suggests that blocking intercellular propagation could be an effective adjunct or alternative approach.

4. Materials and Methods

HEK 293 Cell Culture

Cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified medium (DMEM) with 10% Fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2

Plasmids and Transient Transfection

The Htt plasmid used in this work were previously described[

15]. pDEST-EGFP-Htt25Q-Exon1 encodes the physiological human Htt Exon 1, which contains 25 Glutamines (25Q). pDEST-EGFP-Htt72Q-Exon1 and pDEST-RFP-Htt72Q-Exon1 were used to express a pathological form of human Htt that contains an expansion of the PolyQ stretch to 72 Glutamines (72Q). pDEST-EGFP-Htt72Q-Exon1-Cc- was used to express the Htt pathological sequence (Htt72Q-Exon1) (

Figure 1A (i)) with reduced Cc propensity (72Q Cc)[

15] (

Figure 1A (ii)). ALG-2 interacting protein X (Alix) plasmid was also used in co-transfection experiments (Addgene #21504).

Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine™ 3000 (#L3000-015, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) diluted in serum-free media. The following quantities of total DNA were used: 250 ng/well for the µ-Slide 8 Well imaging chamber; 500 ng/well for the 24-well culture plate; 1 µg/well for the 12-well culture plate; and 1.5 µg/well for the 6-well culture plate.

Viability Assays

The cell’s viability was detected using Alamar Blue (Invitrogen Alamar Blue Cell Viability Reagent, DAL1025) 72 hours after transfection. The fluorescence intensity was quantified with the spectrophotometer TECAN plate reader M200, using λ excitation of 560 nm and λ emission of 590 nm.

Biochemical Assays

Cell Lysis and Protein Extraction

Cells were lysed in extraction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 50 mM KCl, and 10 mM MgCl2) supplemented with complete protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (Roche Applied Science). Cellular debris were removed by centrifugation at 7000× g rpm for 10 min. The proteins contained in the media were precipitated with four volumes of methanol overnight at -20°C and separated by centrifugation at 13000 rpm for 30’ at 4°C.

Detergent Insolubility (D.I)

D.I was carried out adding 20 μL of D.I buffer 2X (1% Triton, 1% NP 40, 1% Sodium deoxycholate (SOD), 20 mM Tris-HCl- pH 7.5 In PBS 1X) to 20 μL of cell extracts and incubated for 30’ at 4°C in continuous rotation. After rotation, samples were centrifuged at 45’000 rpm for 45’ at 4°C. The pellets (P) were collected and the proteins of the supernatants (S) were precipitated with four volumes of methanol overnight at -20°C and separated by centrifugation at 13000 rpm for 30’ at 4°C. Both S and P fractions were resuspended in Laemmli Sample Buffer (LMSB)-2X with 100mM Dithiothreitol (DTT), boiled for 10’ at 95°C at 300 rpm, and loaded in a 10% acrylamide gel.

D.I was also carried out on Htt proteins released in the media. Collected Media was incubated with 10X D.I buffer (5% Triton, 5% NP 40, 5% Sodium deoxycholate (SOD), 100 mM Tris-HCl- pH 7.5 In PBS 1X) at 4°C in continuous rotation for 30 minutes and then centrifuged at 45’000 rpm for 45’ at 4°C. The pellets (P) were collected and the proteins of the supernatants (S) were precipitated with four volumes of methanol overnight at -20°C and separated by centrifugation at 13000 rpm for 30’ at 4°C. At the end of the procedures total protein homogenates and D.I. samples were suspended LMSB-2X with 100mM Dithiothreitol (DTT), boiled for 10’ at 95°C at 300 rpm. Protein samples were then loaded in a 10% acrylamide using Laemmli running buffer (192 mmol/L Tris-base, 78 mmol/L Tris-base, 0.1% SDS) and transferred on PVDF membranes using a semidry Trans-Blot® Turbo™ Transfer System (Bio-Rad, USA) with Mixed molecular weight program for mini membranes (1.3 A, 25V,7 minutes)

Semi-Denaturing Detergent Agarose Gel Electrophoresis (SDD-AGE)

Protein samples from in vitro experiments were obtained as described above and mixed with agarose loading buffer 2x (150mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) 2% Glycerol 33%, Bromophenol Blue 0.025%). Protein extracts from cortical tissues of R6/2 transgenic and non-transgenic littermates were obtained by homogenization in 10 volumes (w/v) of tris-saline (100 mmol/L Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mmol/L NaCl) supplemented with complete protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (Roche Applied Science). Samples were further sonicated by 10 ultrasound pulses with a Branson sonifier. The homogenates were then mixed in agarose loading buffer 2x, and samples are loaded in 1.5% agarose gel containing 375 mmol/L Tris–HCl, pH 8.8, and SDS 0.1%. Samples were run in SDD-Age running buffer (20mM Tris-base, 200 mM Glycine and 0.1% SDS).

After the electrophoretic run, proteins were transferred on PVDF membranes using wettank transfer system at 100 V for 90’ with a Biorad 200 power supply (transfer buffer: 20mM Tris-base, 200 mM Glycine 0.1% SDS, 15% methanol). All the membranes were blocked in 3% BSA for 1 h at RT and then probed with primary antibodies (see

Table 1) overnight at 4 ◦C, followed by HRP secondary antibodies (see

Table 2). Western blot images were acquired with a ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad, USA) and quantified using the Image Lab software 6.0.

Huntingtin Uptake in Co-Plating Conditions

Donor cells were transfected with Htt Exon1 constructs and cultured for 24 h. Recipient cells were labelled with Cell Tracker deep red (Invitrogen, C34565) as follow. Hek 293 Cells (10 6 cells/ mL) were incubated for 1 h with the dye using the final concentration of 25 μM in serum-free DMEM. The tubes were inverted in the middle of the protocol to guarantee proper mixing during the incubation. After incubation, cells were centrifuged 5’ at 1000 rpm and the supernatant was replaced with DMEM Phenol-Red Free (Thermofisher, 31053028). After staining, both donor and recipient cells were sorted, and the positive cells were plated at a ratio of 1:1 and cultured for additional 72 h, after which cells were harvested in D-PBS and analyzed through flow cytometer.

Cell Sorting

FACS sorting was carried out on a MoFlo Astrios cell sorter (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL, USA), using an average sorting rate of 2500–3000 events per second at a sorting pressure of 25 psi with a 100 μm nozzle was maintained. Cells were identified by size and granularity using FSC-A versus SSC-A. Single cells were identified and gated using FSC-A versus FSC-H. The cells with the highest fluorescence intensity of GFP (72Q Cc), RFP (72Q), or Far Red (Cell Tracker labelled cells) were isolated. Post sort analysis was performed using Kaluza 1.2 software (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL, USA).

Flow Cytometry Analysis

Cells were analyzed with Cytoflex LX flow cytometer equipped with CytExpert Acquisition software (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL, USA) based on fluorescence intensity. The cells with the highest fluorescence intensity of GFP (72Q Cc), RFP (72Q) and Far Red (Cell Tracker labelled cells) were assessed. The acquisition process was stopped when all events were collected in the population gate. Offline analysis was performed using Kaluza 1.2 software (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL, USA). A conventional gating strategy was used to remove aggregates, and the percentages of GFP and/or RFP positive cells were quantified.

Immunofluorescence Assays

Media was removed, cells were washed with room temperature PBS, and cells were fixed in 4% Paraformaldehyde and 4% Sucrose in PBS for 10’.

After 3 washes with PBS, cells were permeabilized 5 minutes with PBS 0,5% Triton and blocked 1 hour with PBS 5% NGS. Cells were incubated with Phalloidin Alexa fluor 647 conjugated (1:20 dilution in PBS) for 20 minutes. After 3 washes with PBS, cells were incubated with DAPI (1μg/mL) for 10’, and left in PBS until confocal microscope acquisition.

Confocal Microscope Acquisition

Images were acquired using a confocal A1 system (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a confocal scan unit with 405 nm, 488 nm, 561 nm, and 640 nm laser lines with a scanning sequential mode to avoid bleed-through effects. For Htt granules quantification images were acquired using a 20x objective. For Htt internalization higher-magnification images were acquired using a 60X or 100X objectives over a 9- or 4.5- μm z axis with a pixel size of 0.21μm or 0.12-μm and processed by using Imaris software (Bitplane). Three-dimensional acquisitions were displayed as volumes and as x,y single plane image with z-projections.

Huntingtin Granules Quantification

To quantify Htt granules, 3–5 images totaling >100 cells per sample were acquired using a 20× objective. The granules were analyzed automatically with the Image J plugin “Particle analysis”. A random selection of images was hand-verified. The Htt granule’s average size was analyzed by the Image J software version 1.53C using the ‘analyze particles’ instrument with the threshold “size = 0.00–100.00”.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a compelling picture of how coiled-coil motifs drive a cascade of pathological behaviors in Htt Exon-1 fragments. These include enhanced aggregation, increased detergent insolubility, interaction with exosomal markers, elevated secretion, and facilitated uptake by other cells. These processes mirror features of prion-like spreading observed in other neurodegenerative diseases and suggest that the coiled-coil domain may be a critical regulator of mHtt propagation. Targeting this structural feature could offer a novel approach to slowing the progression of Huntington’s disease by interfering with the intercellular transfer of toxic Htt species.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.F.; methodology, L.F.; validation, M.B., C.G. and F.O.; formal analysis, M.B., C.G, F.O., L.F.; investigation, M.B., C.G, A.P. and L.F.; data curation, M.B., C.G., F.O. and L.F.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B. and L.F.; writing—review and editing, M.B., C.G., A.P., F.O. and L.F.; visualization, M.B., C.G., F.O. and L.F.; supervision, L.F. and C.G.; project administration, L.F.; funding acquisition, L.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Telethon, grant number TCP15011, to LF

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri IRCCS in compliance with national (D.lgs 26/2014; authorization no. 19/2008-A issued 6 March 2008, by the Ministry of Health) and international laws and policies (EEC Council Directive 2010/63/UE; the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 2011 edition).

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are contained within the article. The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Laura Colombo and Monica Favagrossa for providing cortical tissue of Htt transgenic mice R6/2.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.” The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Aziz NA, Jurgens CK, Landwehrmeyer GB, van Roon-Mom WMC, van Ommen GJB, Stijnen T, et al. Normal and mutant HTT interact to affect clinical severity and progression in Huntington disease. Neurology [Internet]. 2009 Sep 23 [cited 2009 Oct 11]; Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19776381. [CrossRef]

- Bates GP, Dorsey R, Gusella JF, Hayden MR, Kay C, Leavitt BR, et al. Huntington disease. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2015 Apr 23;15005.

- Hoffner G, Souès S, Djian P. Aggregation of Expanded Huntingtin in the Brains of Patients With Huntington Disease. Prion. 2007;1(1):26–31. [CrossRef]

- DiFiglia M, Sapp E, Chase KO, Davies SW, Bates GP, Vonsattel JP, et al. Aggregation of huntingtin in neuronal intranuclear inclusions and dystrophic neurites in brain. Science. 1997 Sep 26;277(5334):1990–3. [CrossRef]

- Alpaugh M, Cicchetti F. Huntington’s disease: lessons from prion disorders. J Neurol [Internet]. 2021 Feb 24 [cited 2021 Apr 20]; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-021-10418-8. [CrossRef]

- Babcock DT, Ganetzky B. Transcellular spreading of huntingtin aggregates in the Drosophila brain. PNAS. 2015 Sep 29;112(39):E5427–33.

- Ren PH, Lauckner JE, Kachirskaia I, Heuser JE, Melki R, Kopito RR. Cytoplasmic penetration and persistent infection of mammalian cells by polyglutamine aggregates. Nat Cell Biol. 2009 Feb;11(2):219–25. [CrossRef]

- Cicchetti F, Soulet D, Freeman TB. Neuronal degeneration in striatal transplants and Huntington’s disease: potential mechanisms and clinical implications. Brain. 2011 Mar 1;134(3):641–52. [CrossRef]

- Ehrlich ME. Huntington’s Disease and the Striatal Medium Spiny Neuron: Cell-Autonomous and Non-Cell-Autonomous Mechanisms of Disease. Neurotherapeutics. 2012 Mar 23;9(2):270–84. [CrossRef]

- Pecho-Vrieseling E, Rieker C, Fuchs S, Bleckmann D, Esposito MS, Botta P, et al. Transneuronal propagation of mutant huntingtin contributes to non-cell autonomous pathology in neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2014 Aug;17(8):1064–72. [CrossRef]

- Abounit S, Delage E, Zurzolo C. Identification and Characterization of Tunneling Nanotubes for Intercellular Trafficking. In: Current Protocols in Cell Biology [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2001 [cited 2015 Jun 25]. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/doi/10.1002/0471143030.cb1210s67/abstract. [CrossRef]

- Costanzo M, Zurzolo C. The cell biology of prion-like spread of protein aggregates: mechanisms and implication in neurodegeneration. Biochem J. 2013 May 15;452(1):1–17. [CrossRef]

- Costanzo M, Abounit S, Marzo L, Danckaert A, Chamoun Z, Roux P, et al. Transfer of polyglutamine aggregates in neuronal cells occurs in tunneling nanotubes. J Cell Sci. 2013 Jun 18. [CrossRef]

- Jeon I, Cicchetti F, Cisbani G, Lee S, Li E, Bae J, et al. Human-to-mouse prion-like propagation of mutant huntingtin protein. Acta Neuropathol. 2016 May 24;132(4):577–92. [CrossRef]

- Fiumara F, Fioriti L, Kandel ER, Hendrickson WA. Essential role of coiled coils for aggregation and activity of Q/N-rich prions and PolyQ proteins. Cell. 2010 Dec 23;143(7):1121–35. [CrossRef]

- Mason JM, Arndt KM. Coiled Coil Domains: Stability, Specificity, and Biological Implications. ChemBioChem. 2004 Feb 6;5(2):170–6.

- Parry DAD, Fraser RDB, Squire JM. Fifty years of coiled-coils and α-helical bundles: A close relationship between sequence and structure. Journal of Structural Biology. 2008 Sep;163(3):258–69. [CrossRef]

- Kwok SC, Hodges RS. Stabilizing and Destabilizing Clusters in the Hydrophobic Core of Long Two-stranded α-Helical Coiled-coils. J Biol Chem. 2004 May 14;279(20):21576–88. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki K, Mizuno T, Tanaka T. Regulation of protein-protein interaction via assembly of coiled-coil domain. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser (Oxf). 2008;(52):461. [CrossRef]

- Kokona B, Rosenthal ZP, Fairman R. Role of the Coiled-Coil Structural Motif in Polyglutamine Aggregation. Biochemistry. 2014 Nov 4;53(43):6738–46. [CrossRef]

- Petrakis S, Schaefer MH, Wanker EE, Andrade-Navarro MA. Aggregation of polyQ-extended proteins is promoted by interaction with their natural coiled-coil partners: Insights & Perspectives. BioEssays. 2013 Jun;35(6):503–7.

- Versluis F, Voskuhl J, Vos J, Friedrich H, Ravoo BJ, Bomans PHH, et al. Coiled coil driven membrane fusion between cyclodextrin vesicles and liposomes. Soft Matter. 2014 Nov 19;10(48):9746–51. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang M, Wang W, De Feo CJ, Vassell R, Weiss CD. Trimeric, coiled-coil extension on peptide fusion inhibitor of HIV-1 influences selection of resistance pathways. J Biol Chem. 2012 Mar 9;287(11):8297–309. [CrossRef]

- Administrator ER. Biogenesis and secretion of exosomes | Exosome RNA [Internet]. [cited 2016 Feb 6]. Available from: http://www.exosome-rna.com/biogenesis-and-secretion-of-exosomes/.

- Chang DK, Cheng SF, Trivedi VD, Lin KL. Proline Affects Oligomerization of a Coiled Coil by Inducing a Kink in a Long Helix. Journal of Structural Biology. 1999 Dec 30;128(3):270–9. [CrossRef]

- Fioriti L, Myers C, Huang YY, Li X, Stephan JS, Trifilieff P, et al. The Persistence of Hippocampal-Based Memory Requires Protein Synthesis Mediated by the Prion-like Protein CPEB3. Neuron. 2015 Jun 17;86(6):1433–48. [CrossRef]

- Drisaldi B, Colnaghi L, Fioriti L, Rao N, Myers C, Snyder AM, et al. SUMOylation Is an Inhibitory Constraint that Regulates the Prion-like Aggregation and Activity of CPEB3. Cell Rep. 2015 Jun 23;11(11):1694–702. [CrossRef]

- Stephan JS, Fioriti L, Lamba N, Colnaghi L, Karl K, Derkatch IL, et al. The CPEB3 Protein Is a Functional Prion that Interacts with the Actin Cytoskeleton. Cell Rep. 2015 Jun 23;11(11):1772–85. [CrossRef]

- Weiss A, Abramowski D, Bibel M, Bodner R, Chopra V, DiFiglia M, et al. Single-step detection of mutant huntingtin in animal and human tissues: a bioassay for Huntington’s disease. Anal Biochem. 2009 Dec 1;395(1):8–15. [CrossRef]

- Fioriti L, Quaglio E, Massignan T, Colombo L, Stewart RS, Salmona M, et al. The neurotoxicity of prion protein (PrP) peptide 106-126 is independent of the expression level of PrP and is not mediated by abnormal PrP species. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005 Jan;28(1):165–76. [CrossRef]

- Fioriti L, Dossena S, Stewart LR, Stewart RS, Harris DA, Forloni G, et al. Cytosolic prion protein (PrP) is not toxic in N2a cells and primary neurons expressing pathogenic PrP mutations. J Biol Chem. 2005 Mar 25;280(12):11320–8. [CrossRef]

- Février B, Vilette D, Laude H, Raposo G. Exosomes: a bubble ride for prions? Traffic. 2005 Jan;6(1):10–7.

- Chivet M, Hemming F, Pernet-Gallay karin, Fraboulet S, Sadoul R. Emerging Role of Neuronal Exosomes in the Central Nervous System. Front Physio. 2012;3:145. [CrossRef]

- Chivet M, Javalet C, Hemming F, Pernet-Gallay K, Laulagnier K, Fraboulet S, et al. Exosomes as a novel way of interneuronal communication. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2013 Feb 1;41(1):241–4. [CrossRef]

- Abounit S, Wu JW, Duff K, Victoria GS, Zurzolo C. Tunneling nanotubes: A possible highway in the spreading of tau and other prion-like proteins in neurodegenerative diseases. Prion. 2016 Sep 2;10(5):344–51. [CrossRef]

- Garden GA, La Spada AR. Intercellular (Mis)communication in Neurodegenerative Disease. Neuron. 2012 Mar 8;73(5):886–901.

- Pearce MMP, Spartz EJ, Hong W, Luo L, Kopito RR. Prion-like transmission of neuronal huntingtin aggregates to phagocytic glia in the Drosophila brain. Nat Commun [Internet]. 2015 Apr 13 [cited 2015 Apr 23];6. Available from: http://www.nature.com/ncomms/2015/150413/ncomms7768/full/ncomms7768.html. [CrossRef]

- Gosset P, Maxan A, Alpaugh M, Breger L, Dehay B, Tao Z, et al. Evidence for the spread of human-derived mutant huntingtin protein in mice and non-human primates. Neurobiol Dis. 2020 Jul;141:104941. [CrossRef]

- Batlle C, Calvo I, Iglesias V, J Lynch C, Gil-Garcia M, Serrano M, et al. MED15 prion-like domain forms a coiled-coil responsible for its amyloid conversion and propagation. Commun Biol. 2021 Mar 26;4(1):414. [CrossRef]

- Cheng H, Sablitzky F. The coiled coil domain of DEF6 facilitates formation of large vesicle-like, cytoplasmic aggregates that trap the P-body marker DCP1 and exhibit prion-like features [Internet]. bioRxiv; 2019 [cited 2022 May 10]. p. 538082. Available from: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/538082v1.

- Gerlich DW. Cell organization by liquid phase separation. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2017 Sep 6;18(10):nrm.2017.93. [CrossRef]

- Hayashi Y, Ford LK, Fioriti L, McGurk L, Zhang M. Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation in Physiology and Pathophysiology of the Nervous System. J Neurosci. 2021 Feb 3;41(5):834. [CrossRef]

- Strauss HM, Keller S. Pharmacological interference with protein-protein interactions mediated by coiled-coil motifs. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2008;(186):461–82.

Figure 1.

Time course of Htt aggregates formation. (A) In (i) are shown the aminoacidic sequences of the Htt constructs used: Htt-25Q, Htt-72Q, and Htt-72Q Coiled coil mutant. In (ii) a schematic representation of zenithal view of two coiled helices is shown. Red circles= heptad positions a/d, green circles= g/e, and cyan-to-blue circles=b, c and f. (B) Representative images of fluorescence micrographs of HEK293 cells overexpressing either Htt 25Q, 72Q, or its Cc defective mutants acquired with 20X magnification at three different time points (24h, 48h, and 72 h); scale bar: 50 μm. (C) Aggregation rate of the 3 Htt constructs. (i) Quantification of the number of aggregates per cell. The analyses were carried out at 24h (n=5-6), 48h (n=3-4) and 72h (n= 8-9). One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test; **p< 0.001, ****p<0.00001. (ii) Time course of the number of aggregates per cell. Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test; *p<0.05, ****p<0.00001 72Q vs 25Q; °p<0.05, °°°°p<0.00001 72Q vs 72Q Cc-; $$$$ p<0.00001 72Q 24h vs 48h and 72h. (iii) Quantification of the area occupied by aggregates on the area occupied by the transfected cells. The analyses were carried out at 24h (n=5-6), 48h (n=3-4) and 72h (n= 8-9). One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test; *p< 0.05, ****p<0.00001. (iv) Time course of the area occupied by aggregates, normalized on the cell’s transfection area. The area of Htt 72Q dots increased at 48 and 72h after transfection. Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test, ****p<0.00001 72Q vs 25Q; °°°°p<0.00001 72Q vs 72Q Cc; $$$$ p<0.00001 72Q 24h vs 48h and 72h.

Figure 1.

Time course of Htt aggregates formation. (A) In (i) are shown the aminoacidic sequences of the Htt constructs used: Htt-25Q, Htt-72Q, and Htt-72Q Coiled coil mutant. In (ii) a schematic representation of zenithal view of two coiled helices is shown. Red circles= heptad positions a/d, green circles= g/e, and cyan-to-blue circles=b, c and f. (B) Representative images of fluorescence micrographs of HEK293 cells overexpressing either Htt 25Q, 72Q, or its Cc defective mutants acquired with 20X magnification at three different time points (24h, 48h, and 72 h); scale bar: 50 μm. (C) Aggregation rate of the 3 Htt constructs. (i) Quantification of the number of aggregates per cell. The analyses were carried out at 24h (n=5-6), 48h (n=3-4) and 72h (n= 8-9). One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test; **p< 0.001, ****p<0.00001. (ii) Time course of the number of aggregates per cell. Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test; *p<0.05, ****p<0.00001 72Q vs 25Q; °p<0.05, °°°°p<0.00001 72Q vs 72Q Cc-; $$$$ p<0.00001 72Q 24h vs 48h and 72h. (iii) Quantification of the area occupied by aggregates on the area occupied by the transfected cells. The analyses were carried out at 24h (n=5-6), 48h (n=3-4) and 72h (n= 8-9). One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test; *p< 0.05, ****p<0.00001. (iv) Time course of the area occupied by aggregates, normalized on the cell’s transfection area. The area of Htt 72Q dots increased at 48 and 72h after transfection. Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test, ****p<0.00001 72Q vs 25Q; °°°°p<0.00001 72Q vs 72Q Cc; $$$$ p<0.00001 72Q 24h vs 48h and 72h.

Figure 2.

Coiled-coil abolition reduces aggregation and insolubility of Htt Exon-1 72Q. (A) Experimental Design. (B) (i) Representative image of Htt constructs aggregation via Semi-Denaturing Detergent Agarose Gel Electrophoresis (SDD-AGE). As positive control we used R6/2 transgenic mice brain samples, overexpressing the first exon of the human mutant huntingtin gene with approximately 160 CAG repeats, and their non-transgenic littermate as negative control. (ii) Representative image of WB analysis to demonstrate equal expression. (C) (i) Schematic representation of Detergent insolubility assay obtained by ultracentrifugation. (ii) Western blots of ultracentrifugation assays on lysates of HEK293 cells overexpressing of 25Q, 72Q or 72Q Cc defective mutant. Soluble (S) and insoluble pellet (P) fractions were incubated with primary antibody selective for Poly-Q sequence. (iii) Quantification of the Pellet insoluble fraction over the total (S+P) Htt protein in ultracentrifugation assay. 72Q was enriched in the insoluble fraction compared to the soluble one. Then, 25Q and 72Q Cc- mutants displayed opposite pattern with a remarkable reduction of the insoluble fraction. One-way ANOVA, followed by the Tukey’s test * p< 0.05, **p<0.01. Bars represent mean ± SEM (n = 3-5 from three independent experiments).

Figure 2.

Coiled-coil abolition reduces aggregation and insolubility of Htt Exon-1 72Q. (A) Experimental Design. (B) (i) Representative image of Htt constructs aggregation via Semi-Denaturing Detergent Agarose Gel Electrophoresis (SDD-AGE). As positive control we used R6/2 transgenic mice brain samples, overexpressing the first exon of the human mutant huntingtin gene with approximately 160 CAG repeats, and their non-transgenic littermate as negative control. (ii) Representative image of WB analysis to demonstrate equal expression. (C) (i) Schematic representation of Detergent insolubility assay obtained by ultracentrifugation. (ii) Western blots of ultracentrifugation assays on lysates of HEK293 cells overexpressing of 25Q, 72Q or 72Q Cc defective mutant. Soluble (S) and insoluble pellet (P) fractions were incubated with primary antibody selective for Poly-Q sequence. (iii) Quantification of the Pellet insoluble fraction over the total (S+P) Htt protein in ultracentrifugation assay. 72Q was enriched in the insoluble fraction compared to the soluble one. Then, 25Q and 72Q Cc- mutants displayed opposite pattern with a remarkable reduction of the insoluble fraction. One-way ANOVA, followed by the Tukey’s test * p< 0.05, **p<0.01. Bars represent mean ± SEM (n = 3-5 from three independent experiments).

Figure 3.

Htt 72Q colocalizes with exosome marker Alix. (A) Experimental design. (B) Representative images of Htt Exon-1 constructs (green) co-transfected with exosomal marker Alix (red), acquired 30 h after transfection using 100X objective. Alix signal was diffused throughout the cytosol but it also colocalized with 72Q aggregates. In cells transfected with 25Q and 72Q Cc-, the Alix signal was more diffuse. Scale bar: 10 μm.

Figure 3.

Htt 72Q colocalizes with exosome marker Alix. (A) Experimental design. (B) Representative images of Htt Exon-1 constructs (green) co-transfected with exosomal marker Alix (red), acquired 30 h after transfection using 100X objective. Alix signal was diffused throughout the cytosol but it also colocalized with 72Q aggregates. In cells transfected with 25Q and 72Q Cc-, the Alix signal was more diffuse. Scale bar: 10 μm.

Figure 4.

Htt 72Q is released in insoluble form in culture media, and its secretion is reduced if the Coiled-coil structure is hampered. (A) Experimental design. (B) (i) Representative WB images of lysates and cell media incubated with primary antibody selective for the sequence Poly-Q. (ii) Quantification of the proteins released in the media, in relation to the total Htt expression (lysate+media). All Htt proteins were released in the medium. 72Q protein is released significantly more compared to 25Q and 72Q Cc-. One-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s test, ** p< 0.01 ***p<0.001 (n=7-9 replicates from 3 independent experiments). Bars represent mean ± SEM. (iii) Alamar Blue viability test carried out at 72h post transfection showed that expression of the constructs for up to 72h did not induce cellular toxicity. One-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s test. No significant difference between the groups was found. Bars represent mean ± SEM. (C) Quantification of Htt insoluble fraction released in the media. (i) Western blot of DI assays on the media of HEK293 cells overexpressing 25Q, 72Q, or 72Q Cc defective mutant. Soluble (S) and insoluble pellet (P) fractions were incubated with anti Poly-Q antibody. (ii) Quantification of DI assays. 72Q released in the medium was significantly more insoluble compared to both 25Q and 72Q Cc-. (n=3-5 from three independent experiments). One-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s test; * p< 0.05 **p<0.01. Bars represent mean ± SEM (n=3 from three independent experiments).

Figure 4.

Htt 72Q is released in insoluble form in culture media, and its secretion is reduced if the Coiled-coil structure is hampered. (A) Experimental design. (B) (i) Representative WB images of lysates and cell media incubated with primary antibody selective for the sequence Poly-Q. (ii) Quantification of the proteins released in the media, in relation to the total Htt expression (lysate+media). All Htt proteins were released in the medium. 72Q protein is released significantly more compared to 25Q and 72Q Cc-. One-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s test, ** p< 0.01 ***p<0.001 (n=7-9 replicates from 3 independent experiments). Bars represent mean ± SEM. (iii) Alamar Blue viability test carried out at 72h post transfection showed that expression of the constructs for up to 72h did not induce cellular toxicity. One-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s test. No significant difference between the groups was found. Bars represent mean ± SEM. (C) Quantification of Htt insoluble fraction released in the media. (i) Western blot of DI assays on the media of HEK293 cells overexpressing 25Q, 72Q, or 72Q Cc defective mutant. Soluble (S) and insoluble pellet (P) fractions were incubated with anti Poly-Q antibody. (ii) Quantification of DI assays. 72Q released in the medium was significantly more insoluble compared to both 25Q and 72Q Cc-. (n=3-5 from three independent experiments). One-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s test; * p< 0.05 **p<0.01. Bars represent mean ± SEM (n=3 from three independent experiments).

Figure 5.

Uptake of Htt in co-culture experiments. (A) Experimental design. Hek293 cells expressing 72Q or 72Q Cc- and HEK293 cells labelled with DiD tracker were sorted and co-plated 1:1. (B) Detection of Htt Exon-1 fragments in DiD Cell Tracker labeled recipient cells by flow cytometry. (i) Positive counts 72Q RFP and Cell Tracker DiD far red Signal, (ii) Positive counts 72Q Cc-GFP and Cell Tracker DiD far red Signal. Both 72Q and 72Q Cc- proteins were internalized by recipient cells. (iii) Statistical analysis of positive recipient cells on donor cells obtained from 3 independent experiments (n=3 per condition) showing that the internalization of the 72Q Cc- protein in recipient cells was significantly reduced compared to 72Q in cell-to-cell contact conditions. One-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s test, ****p<0.0001. Bars represent mean ± SEM. C. Hek293 cells expressing Htt Exon-1 72Q or 72Q Cc- and Cell tracker labelled cells were sorted and co-plated in the ratio 1:1. after 72 hours in co-plating cells were fixed. Images are acquired with 60X objective. Both 72Q and 72Q Cc- proteins can be internalized by recipient cells, as shown by x, y single-plane image with z-projections. Scale bar: 10 µm.

Figure 5.

Uptake of Htt in co-culture experiments. (A) Experimental design. Hek293 cells expressing 72Q or 72Q Cc- and HEK293 cells labelled with DiD tracker were sorted and co-plated 1:1. (B) Detection of Htt Exon-1 fragments in DiD Cell Tracker labeled recipient cells by flow cytometry. (i) Positive counts 72Q RFP and Cell Tracker DiD far red Signal, (ii) Positive counts 72Q Cc-GFP and Cell Tracker DiD far red Signal. Both 72Q and 72Q Cc- proteins were internalized by recipient cells. (iii) Statistical analysis of positive recipient cells on donor cells obtained from 3 independent experiments (n=3 per condition) showing that the internalization of the 72Q Cc- protein in recipient cells was significantly reduced compared to 72Q in cell-to-cell contact conditions. One-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s test, ****p<0.0001. Bars represent mean ± SEM. C. Hek293 cells expressing Htt Exon-1 72Q or 72Q Cc- and Cell tracker labelled cells were sorted and co-plated in the ratio 1:1. after 72 hours in co-plating cells were fixed. Images are acquired with 60X objective. Both 72Q and 72Q Cc- proteins can be internalized by recipient cells, as shown by x, y single-plane image with z-projections. Scale bar: 10 µm.

Figure 6.

Uptake of Htt in cells exposed to media containing Htt. (A) Experimental design. 72 h after transfection with 72Q or 72Q Cc-, culture media was collected and the amount of Htt was quantified by Western blot analysis. Hek293 naïve cells were exposed for 96 h to conditioned media containing the same amount of 72Q or 72Q Cc-. (B) Detection of Htt in recipient cells by flow cytometry analysis. (i) Cells positive for 72Q, (ii) cells positive for 72Q Cc-. (iii) Statistical analysis of positive recipient cells obtained from 4 independent experiments (n=4 per condition). One-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s test, *p<0.05. Bars represent mean ± SEM. The internalization of the 72Q Cc- protein in recipient cells was significantly reduced compared to 72Q after exposure to conditioned media. (C) Confocal images of cells exposed to media collected from 72Q or 72Q Cc- transfected cells. Cells were fixed after 96 h of incubation with the media and stained with Phalloidin dye. Images were acquired with 100X objective. Both 72Q and 72Q Cc- proteins can be internalized by recipient cells as shown by x, y single-plane image with z-projections, however 72Q was internalized more than 72Q Cc-. Scale bar: 10 µm.

Figure 6.

Uptake of Htt in cells exposed to media containing Htt. (A) Experimental design. 72 h after transfection with 72Q or 72Q Cc-, culture media was collected and the amount of Htt was quantified by Western blot analysis. Hek293 naïve cells were exposed for 96 h to conditioned media containing the same amount of 72Q or 72Q Cc-. (B) Detection of Htt in recipient cells by flow cytometry analysis. (i) Cells positive for 72Q, (ii) cells positive for 72Q Cc-. (iii) Statistical analysis of positive recipient cells obtained from 4 independent experiments (n=4 per condition). One-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s test, *p<0.05. Bars represent mean ± SEM. The internalization of the 72Q Cc- protein in recipient cells was significantly reduced compared to 72Q after exposure to conditioned media. (C) Confocal images of cells exposed to media collected from 72Q or 72Q Cc- transfected cells. Cells were fixed after 96 h of incubation with the media and stained with Phalloidin dye. Images were acquired with 100X objective. Both 72Q and 72Q Cc- proteins can be internalized by recipient cells as shown by x, y single-plane image with z-projections, however 72Q was internalized more than 72Q Cc-. Scale bar: 10 µm.

Table 1.

Caption.

Antibody

(Clone) |

Host Animal |

Dilution for

Western Blot |

Distributor,

Catalogue number |

| PolyQ (3B5H10) |

Monoclonal Mouse |

1:1000 |

Sigma, P1874 |

| Huntingtin (EM-48) |

Monoclonal Mouse |

1:500 |

Merk Millipore, MAB5374 |

| GAPDH (FL-335) |

Polyclonal Rabbit |

1:1000 |

Santacruz, sc-25778 |

Table 2.

Caption.

Antibody

(Clone) |

Host Animal |

Dilution for

Western Blot |

Distributor,

Catalogue number |

| Anti HRP |

Mouse |

1:10000 |

Jackson Immunoresearch, #115-035-174 |

| Anti HRP |

Rabbit |

1:10000 |

GE Healthcare, NA934 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).