Submitted:

25 May 2025

Posted:

26 May 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

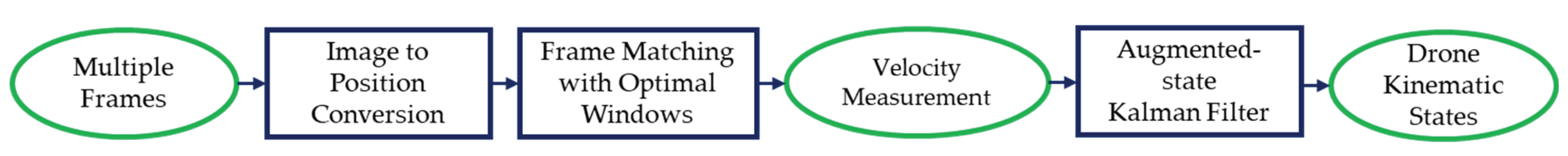

2. Drone Velocity Measurement

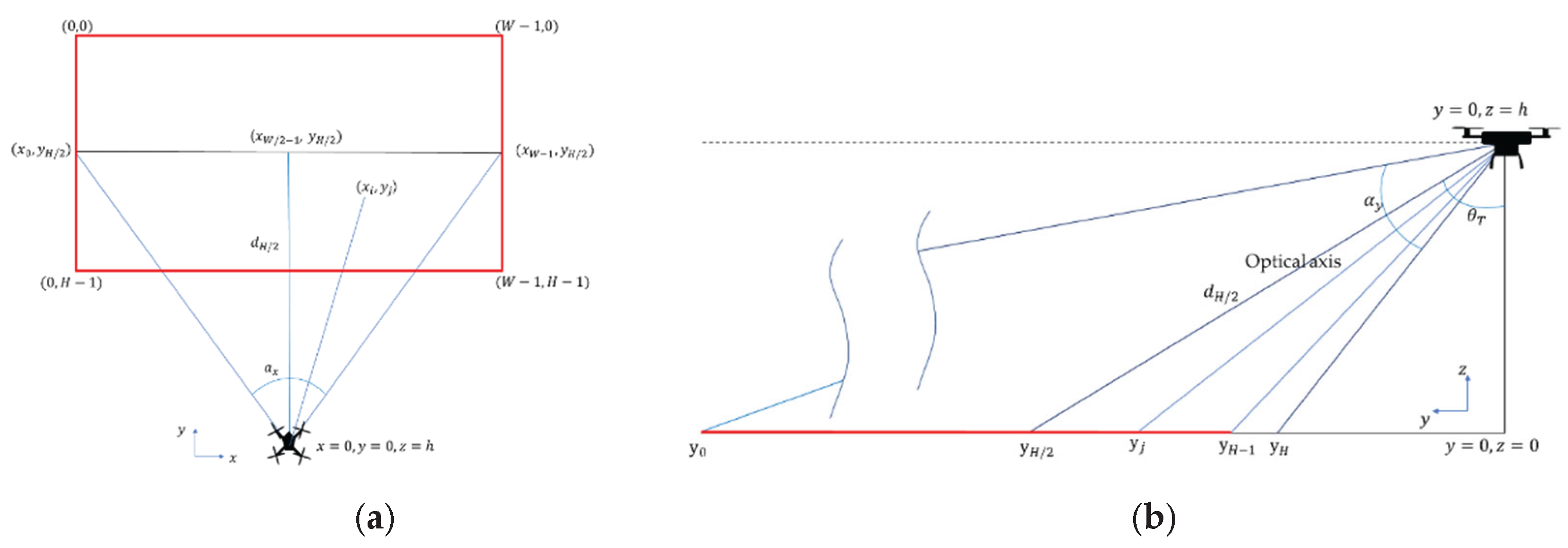

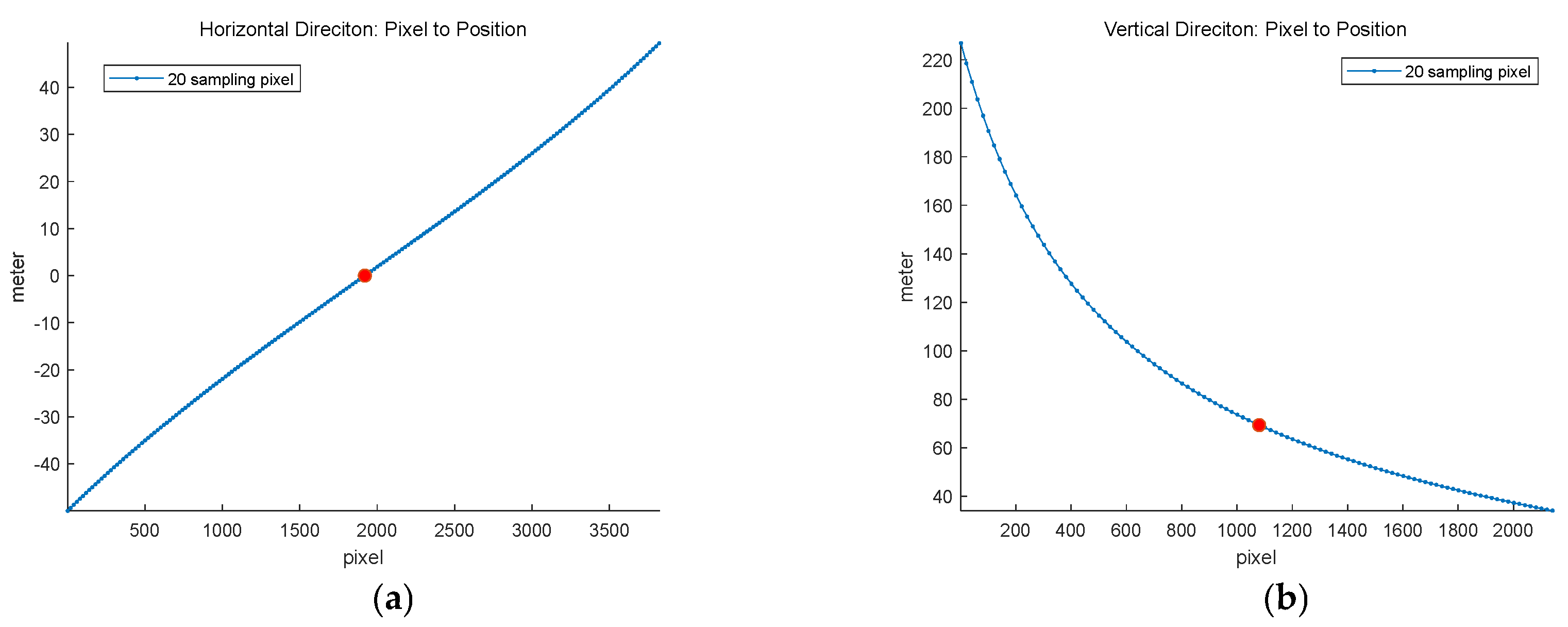

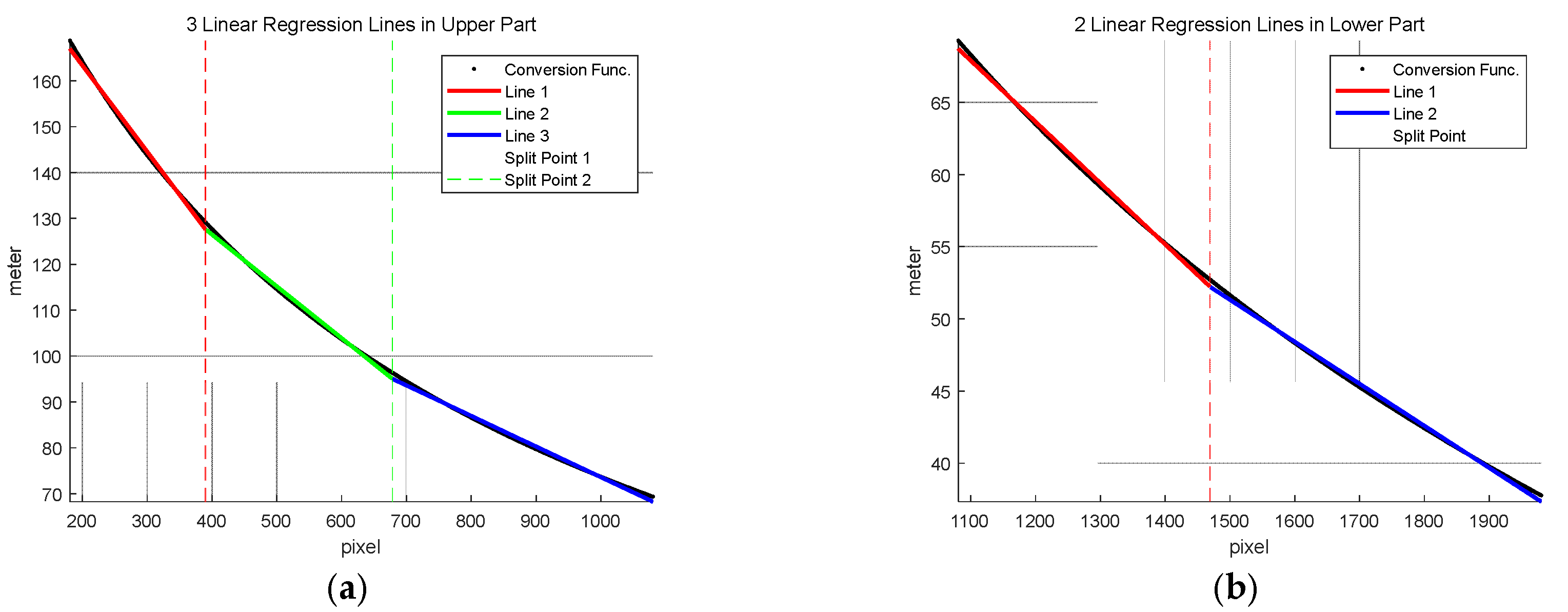

2.1. Image-to-Position Conversion

2.2. Frame-to-Frame Template Matching with Optimal Windows

3. Drone State Estimation

3.1. System Modeling

3.2. Kalman Filtering

4. Results

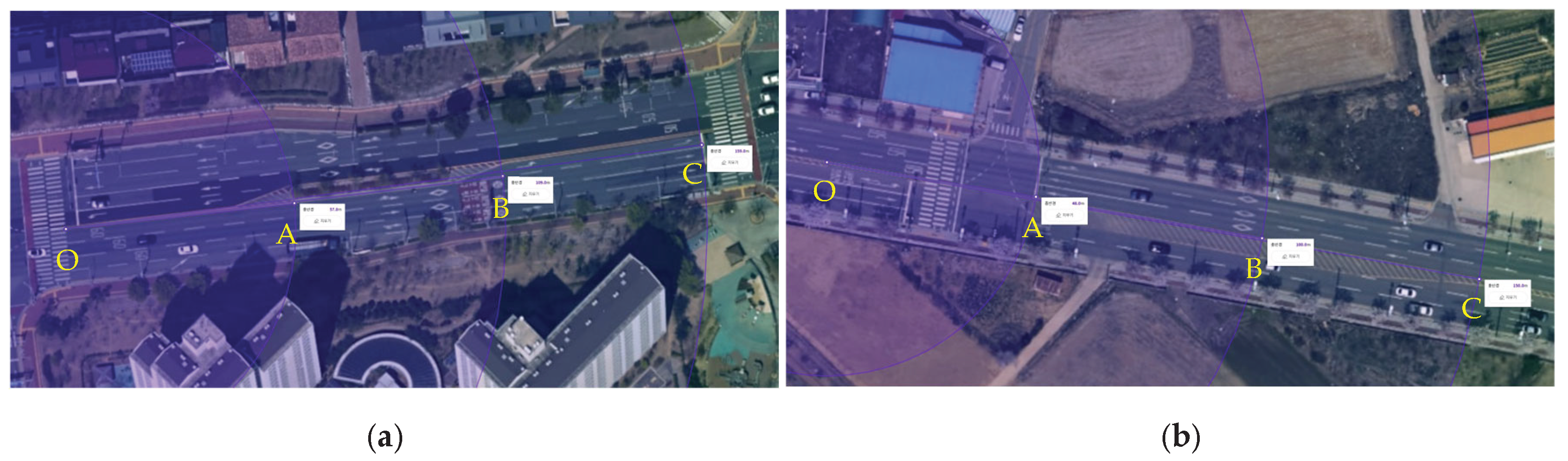

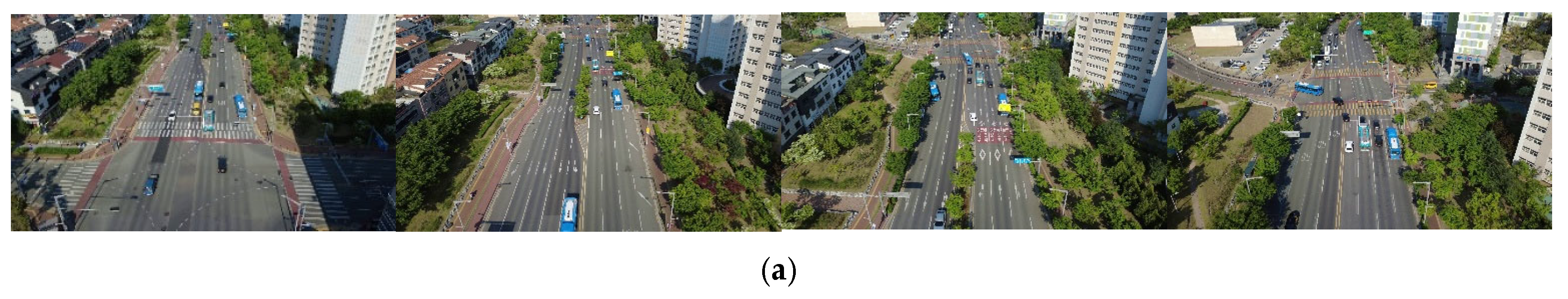

4.1. Scenario Description

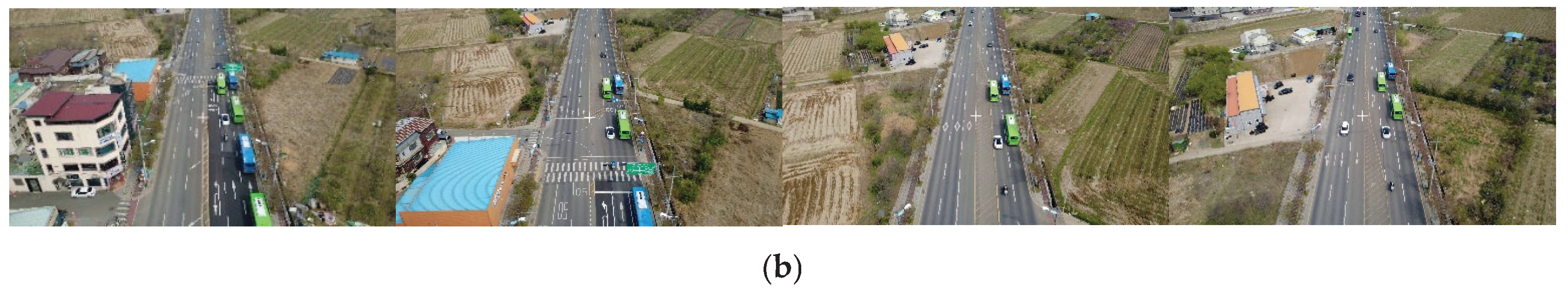

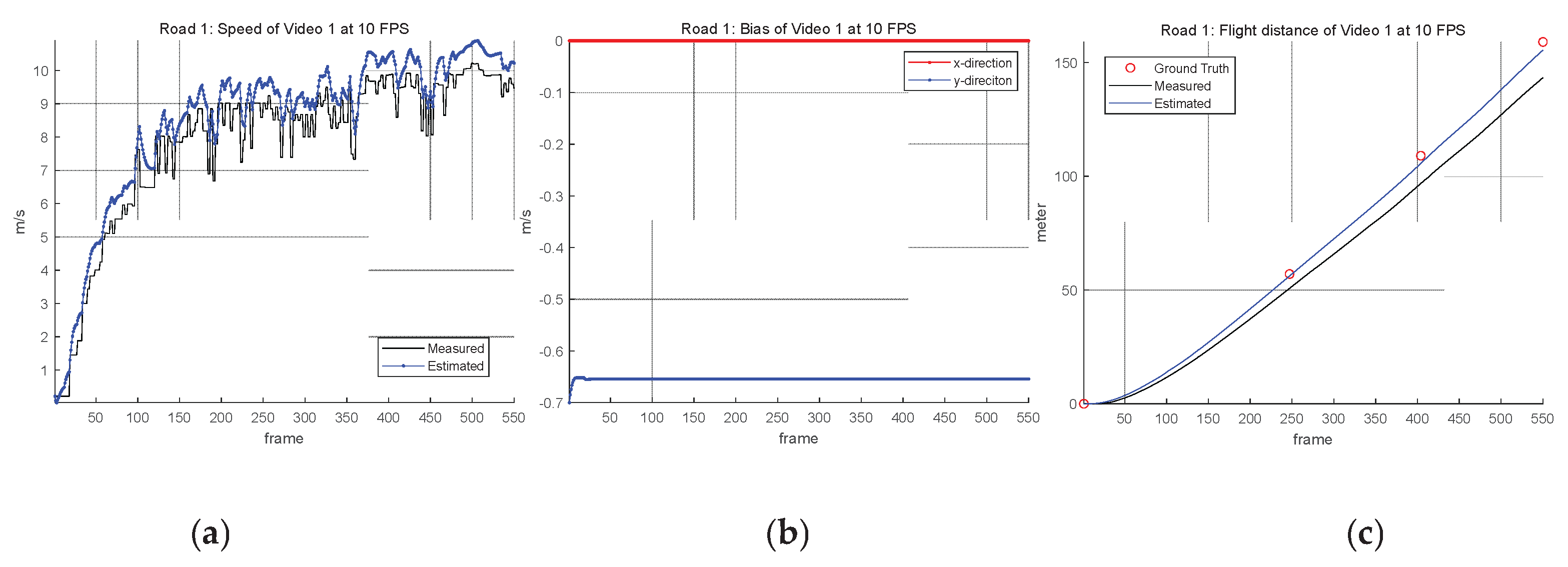

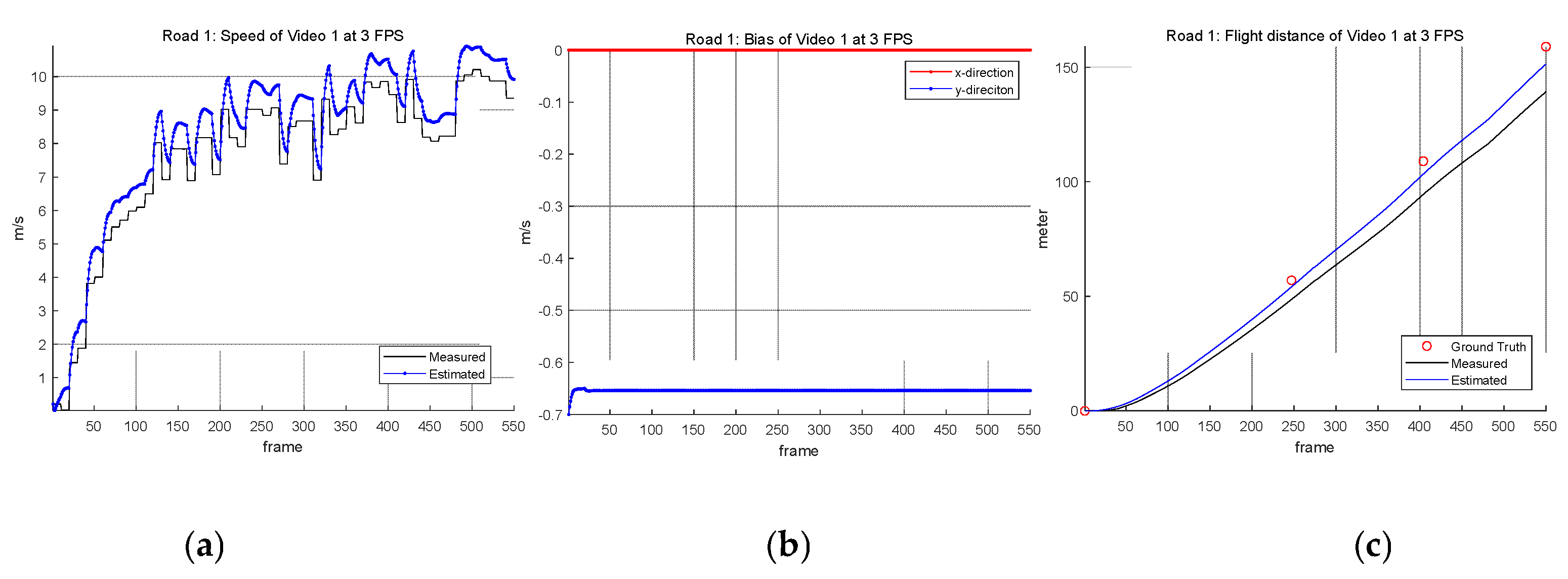

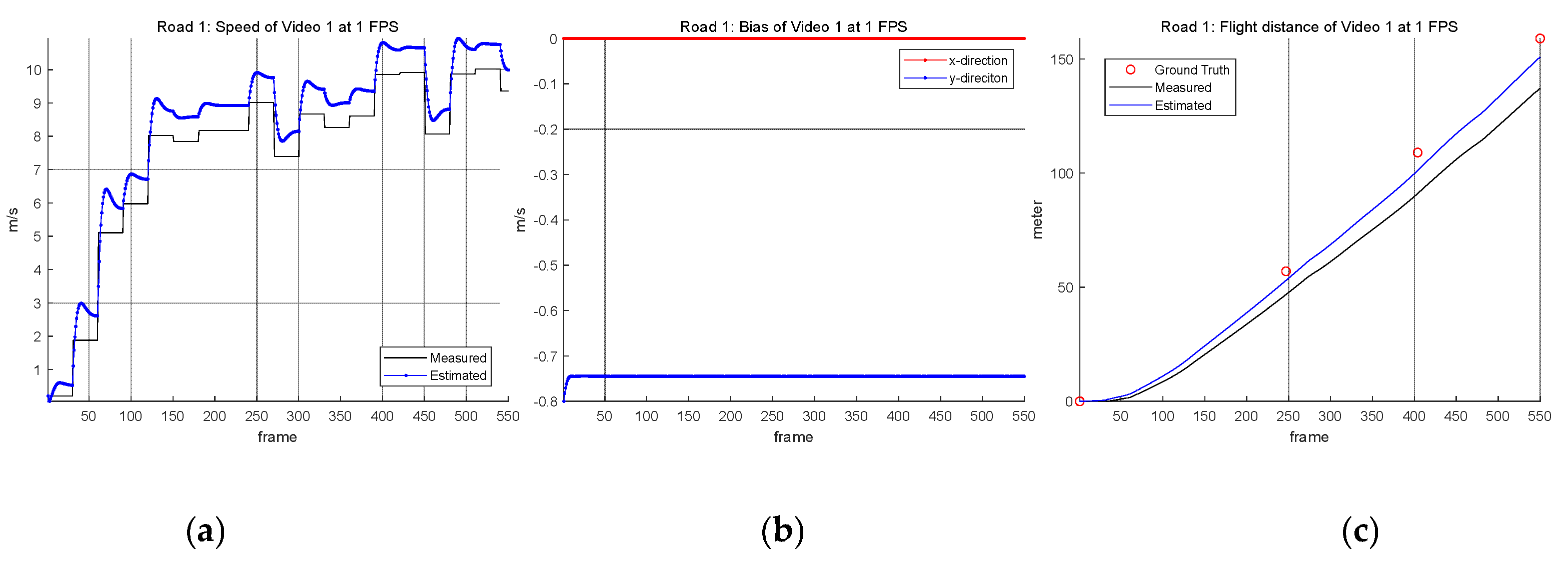

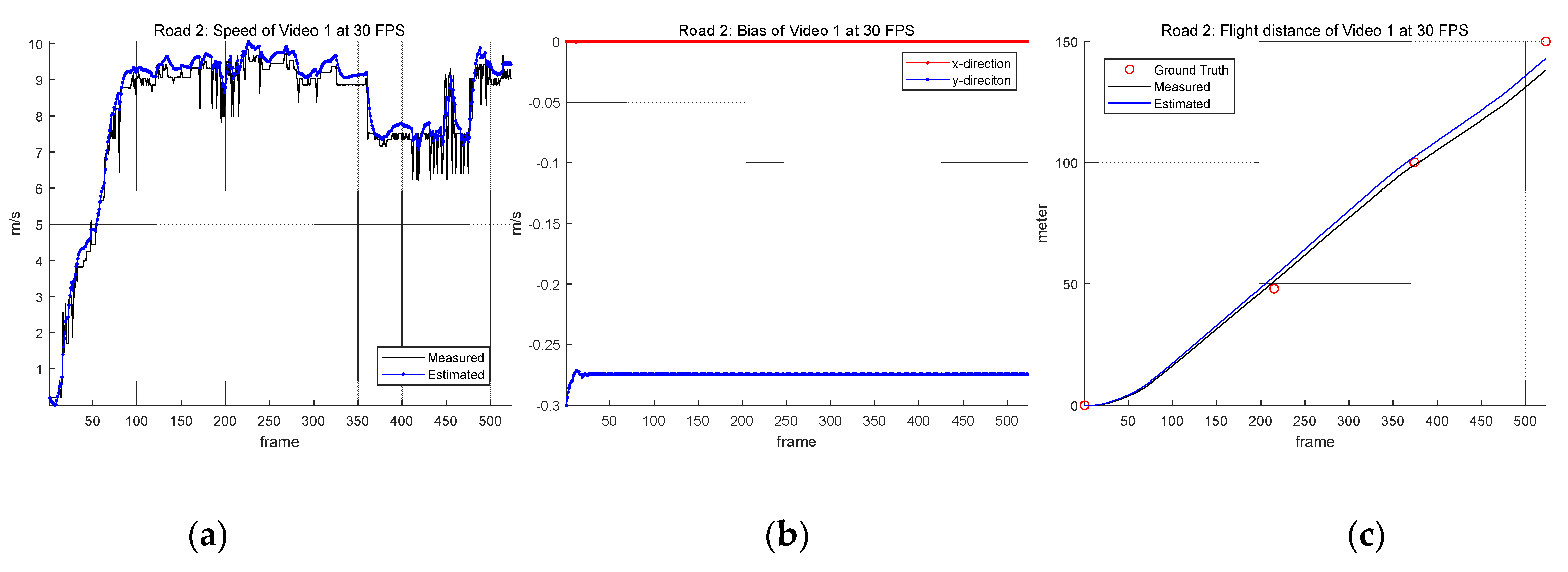

4.2. Drone State Estimation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zaheer, Z.; Usmani, A.; Khan, E.; Qadeer, M.A. , "Aerial surveillance system using UAV," 2016 Thirteenth International Conference on Wireless and Optical Communications Networks (WOCN), Hyderabad, India, 2016, pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Vohra, D.; Garg, P.; Ghosh, S. (2023). Usage of UAVs/Drones Based on Their Categorisation: A Review. Journal of Aerospace Science and Technology, 74, 90–101. [CrossRef]

- Osmani, K.; Schulz, D. Comprehensive Investigation of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs): An In-Depth Analysis of Avionics Systems. Sensors 2024, 24, 3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Würbel, Heike. (2017). Framework for the evaluation of cost-effectiveness of drone use for the last-mile delivery of vaccines.

- Zhang, Z.; Zhu, L. A Review on Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Remote Sensing: Platforms, Sensors, Data Processing Methods, and Applications. Drones 2023, 7, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, F. , Idries, A., Mohamed, N., Al-Jaroodi, J., and Jawhar, I. (2014). UAVs for smart cities: Opportunities and challenges. Future Generation Computer Systems, 93, 880–893. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Tian, Y.; Lin, L.; Chen, S.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Su, K. Obtaining World Coordinate Information of UAV in GNSS Denied Environments. Sensors 2020, 20, 2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokhamad Nur Cahyadi, Tahiyatul Asfihani, Ronny Mardiyanto, Risa Erfianti, Performance of GPS and IMU sensor fusion using unscented Kalman filter for precise i-Boat navigation in infinite wide waters, Geodesy and Geodynamics, Volume 14, Issue 3, 2023, Pages 265-274. [CrossRef]

- Kovanič, Ľ.; Topitzer, B.; Peťovský, P.; Blišťan, P.; Gergeľová, M.B.; Blišťanová, M. Review of Photogrammetric and Lidar Applications of UAV. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrlik, M.; Spurny, V.; Vonasek, V.; Faigl, J.; Preucil, L. LiDAR-Based Stabilization, Navigation and Localization for UAVs. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Athens, Greece, 15–18 June 2021; p. 1220. Available online: https://aerial-core.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/ICUAS_2021_Matej.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Gaigalas, J.; Perkauskas, L.; Gricius, H.; Kanapickas, T.; Kriščiūnas, A. A Framework for Autonomous UAV Navigation Based on Monocular Depth Estimation. Drones 2025, 9, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yingxiu Chang, Yongqiang Cheng, Umar Manzoor, John Murray, A review of UAV autonomous navigation in GPS-denied environments, Robotics and Autonomous Systems, Volume 170, 2023, 104533. [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Yang, E. A Survey on Radio Frequency Based Precise Localisation Technology for UAV in GPS-Denied Environment. Journal of Intelligent and Robotic Systems 2021, 101, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarraya, I. , Al-Batati, A., Kadri, M.B. et al. Gnss-denied unmanned aerial vehicle navigation: analyzing computational complexity, sensor fusion, and localization methodologies. Satell Navig 6, 9 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, R.C.; Woods, R.E. Digital Image Processing, 4th ed., Pearson, 2018.

- Brunelli, R. , “Template matching techniques in computer vision: a survey,” Pattern Recognition, vol. 38, no. 11, pp. 2011–2040, 2003. [CrossRef]

- Scaramuzza, D.; Fraundorfer, F. Visual Odometry [Tutorial]. IEEE Robotics and Automation Magazine 2011, 18, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauffer, C.; Grimson, W.E.L. Adaptive background mixture models for real-time tracking. CVPR 1999, 2, 246–252. [Google Scholar]

- Forster, C. , Pizzoli, M., and Scaramuzza, D. (2014). SVO: Fast semi-direct monocular visual odometry. IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), pp. 15–22. [CrossRef]

- Kalal, Z. , Mikolajczyk, K., and Matas, J. (2012). Tracking-Learning-Detection. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 34(7), 1409–1422. [CrossRef]

- Hecht, E. “Optics” 5nd edition (Pearson, 2017).

- Yeom, S. Long Distance Ground Target Tracking with Aerial Image-to-Position Conversion and Improved Track Association. Drones 2022, 6, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeom, S.; Nam, D.-H. Moving Vehicle Tracking with a Moving Drone Based on Track Association. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muggeo, V. M. R. (2003). Estimating regression models with unknown break-points. Statistics in Medicine, 22(19), 3055–3071. [CrossRef]

- Bishop, Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning, Springer.

- OpenCV Developers. (2024). Template Matching. OpenCV.org. https://docs.opencv.org/4.x/d4/dc6/tutorial_py_template_matching.html.

- Bar-Shalom, Y.; Li, X.R. Multitarget-Multisensor Tracking: Principles and Techniques; YBS Publishing: Storrs, CT, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, D. (2006). Optimal state estimation: Kalman, H∞, and nonlinear approaches. Wiley-Interscience.

- Anderson, B. D. O. , and Moore, J. B. (1979). Optimal Filtering. Prentice-Hall.

- https://dl.djicdn.com/downloads/DJI_Mini_4K/DJI_Mini_4K_User_Manual_v1.0_EN.pdf.

| Parameter (Unit) | Road 1 | Road 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Sampling Time (T) (second) | 1/30 | |

| Process Noise Std. () (m/s2) | (3, 3) | |

| Bias Noise Std. () (m/s) | (0.01,0.1) | |

| Measurement Noise Std. () (m/s) | (2,2) | |

| Initial Bias in x direction () (m/s) | 0 | |

| Initial Covariance for Bias () (m2 /s2) | (0.1, 0.1) | |

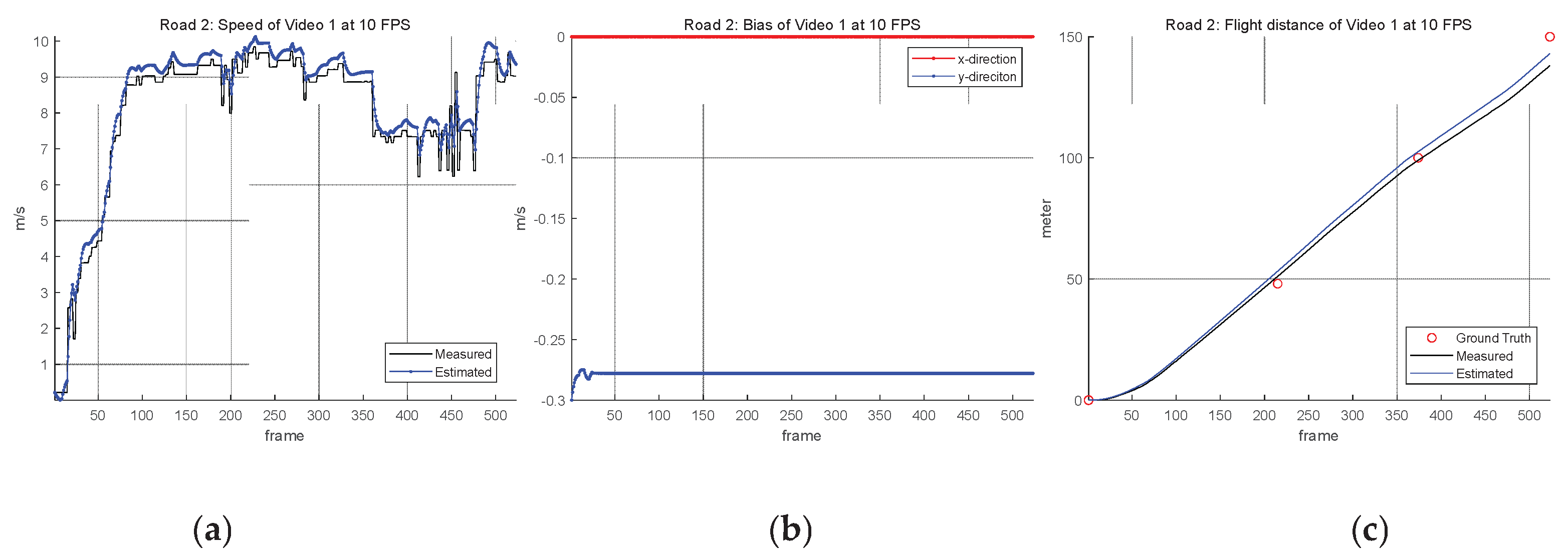

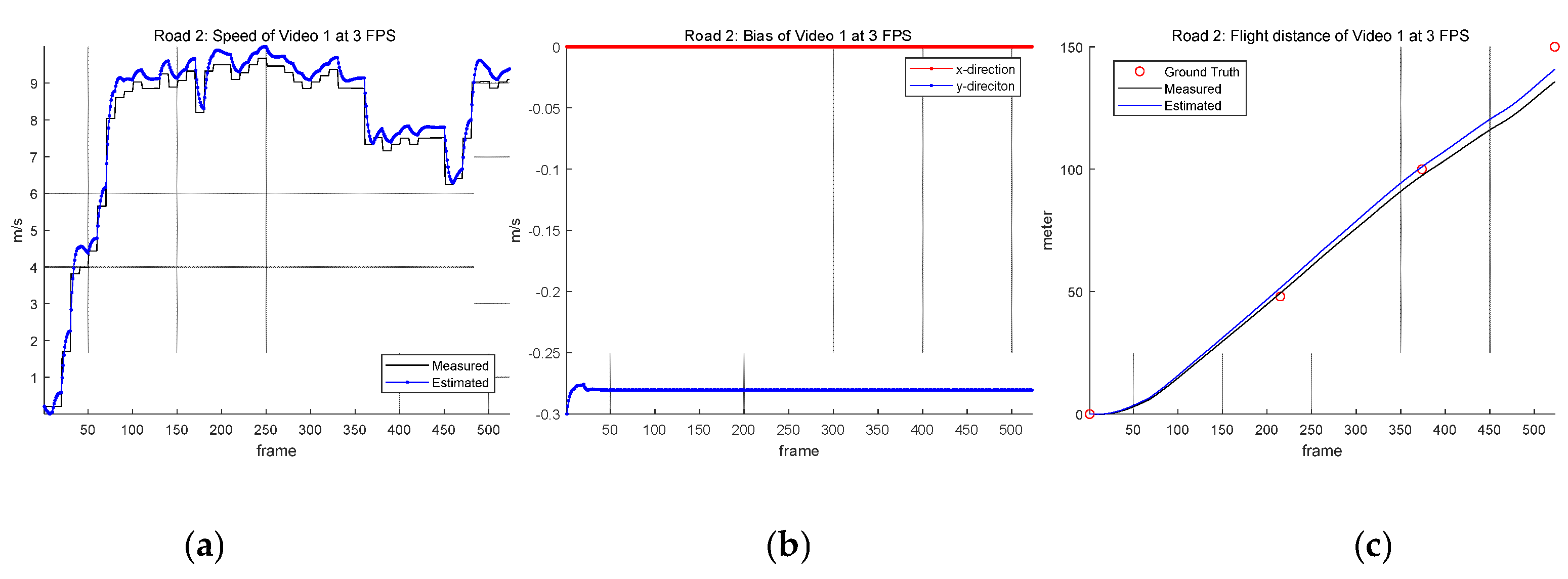

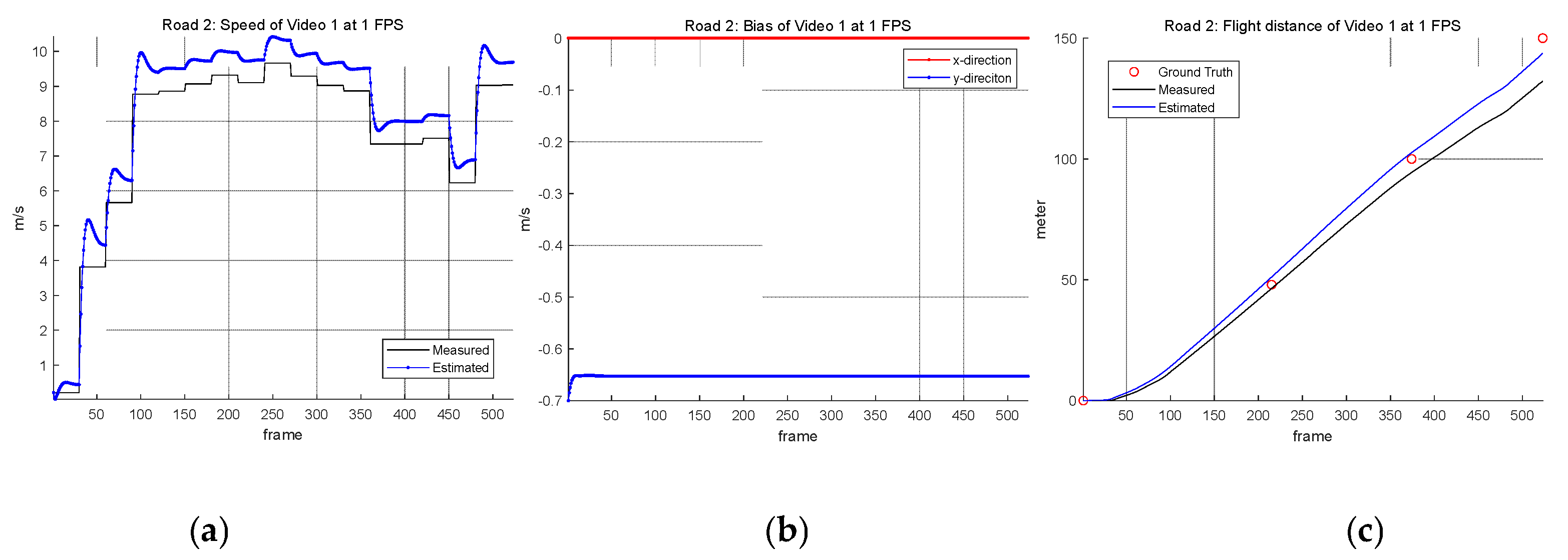

| Frame Matching Speed (FPS) | Road 1 | Road 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | ||

| 30 | -0.7 | |||

| 10 | -0.3 | 0 | 0.2 | |

| 3 | ||||

| 1 | -0.8 | -0.7 | -0.3 | -0.1 |

| FPS | Type | Video 1 | Video 2 | Video 3 | Video 4 | Video 5 | Video 6 | Video 7 | Video 8 | Video 9 | Video 10 | Avg. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | Meas. | 16.33 | 7.69 | 7.32 | 6.77 | 9.26 | 11.53 | 13.69 | 17.06 | 14.29 | 15.99 | 11.99 |

| Est. | 4.25 | 4.55 | 4.95 | 5.54 | 3.10 | 0.89 | 1.46 | 4.50 | 2.02 | 3.95 | 3.52 | |

| 10 | Meas. | 15.66 | 8.07 | 7.74 | 7.15 | 9.53 | 12.34 | 13.70 | 17.32 | 14.82 | 16.70 | 12.30 |

| Est. | 3.59 | 4.15 | 4.51 | 5.15 | 2.82 | 0.08 | 1.47 | 4.79 | 2.57 | 4.63 | 3.38 | |

| 3 | Meas. | 19.73 | 9.49 | 10.43 | 8.28 | 11.45 | 12.92 | 13.90 | 18.04 | 13.75 | 16.47 | 13.45 |

| Est. | 7.65 | 2.71 | 1.81 | 4.00 | 0.91 | 0.51 | 1.69 | 5.50 | 1.53 | 4.34 | 3.07 | |

| 1 | Meas. | 21.89 | 14.33 | 15.92 | 13.58 | 15.57 | 18.19 | 17.83 | 19.18 | 16.08 | 19.46 | 17.20 |

| Est. | 8.16 | 0.40 | 1.96 | 0.39 | 1.47 | 4.03 | 3.92 | 4.85 | 2.12 | 5.68 | 3.30 |

| FPS | Type | Video 1 | Video 2 | Video 3 | Video 4 | Video 5 | Video 6 | Video 7 | Video 8 | Video 9 | Video 10 | Avg. |

| 30 | Meas. | 11.96 | 4.60 | 5.47 | 0.35 | 0.46 | 3.94 | 4.84 | 5.10 | 4.21 | 11.96 | 5.29 |

| Est. | 7.04 | 1.39 | 0.69 | 0.22 | 0.31 | 0.71 | 1.66 | 1.78 | 1.22 | 8.83 | 2.39 | |

| 10 | Meas. | 12.00 | 5.37 | 5.55 | 0.87 | 0.74 | 3.56 | 4.39 | 4.65 | 4.22 | 11.16 | 5.25 |

| Est. | 7.02 | 1.99 | 0.63 | 0.70 | 0.57 | 0.33 | 1.22 | 1.33 | 1.20 | 8.03 | 2.30 | |

| 3 | Meas. | 14.32 | 6.09 | 5.89 | 2.23 | 1.91 | 2.30 | 2.48 | 3.09 | 2.63 | 8.56 | 4.95 |

| Est. | 9.31 | 1.58 | 0.92 | 2.06 | 1.76 | 0.93 | 0.71 | 0.22 | 0.46 | 5.40 | 2.33 | |

| 1 | Meas. | 17.78 | 8.45 | 11.18 | 5.73 | 4.31 | 1.15 | 1.26 | 1.46 | 1.41 | 5.18 | 5.79 |

| Est. | 6.33 | 2.59 | 0.22 | 0.49 | 0.89 | 0.72 | 0.60 | 0.46 | 0.44 | 7.01 | 1.97 |

| FPS | Type | Point A (57 m) | Point B (109 m) |

Point C (159 m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | Meas. | 5.17 | 9.58 | 11.99 |

| Est. | 1.68 | 2.35 | 3.52 | |

| 10 | Meas. | 5.47 | 9.93 | 12.30 |

| Est. | 1.68 | 2.34 | 3.38 | |

| 3 | Meas. | 6.52 | 11.24 | 13.45 |

| Est. | 1.51 | 2.39 | 3.07 | |

| 1 | Meas. | 10.16 | 15.12 | 17.20 |

| Est. | 3.74 | 4.81 | 3.30 |

| FPS | Type | Point A (48 m) |

Point B (100 m) |

Point C (150 m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | Meas. | 3.25 | 4.27 | 5.29 |

| Est. | 3.18 | 3.30 | 2.39 | |

| 10 | Meas. | 2.88 | 4.07 | 5.25 |

| Est. | 2.83 | 3.00 | 2.30 | |

| 3 | Meas. | 1.99 | 3.29 | 4.95 |

| Est. | 1.84 | 1.69 | 2.33 | |

| 1 | Meas. | 2.41 | 4.23 | 5.79 |

| Est. | 1.34 | 2.19 | 1.97 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).