Submitted:

23 June 2023

Posted:

23 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Combine the Kalman filter and the optical flow to predict the motion state of the object to improve the prediction accuracy.

- A low confidence tracking filtering extension was added to the Deep SORT tracking algorithm to reduce false positive tracks.

- Use the visual servo controller to assist the UAV to automatically complete the tracking task, and has no negative impact on other controllers.

2. Materials and Methods

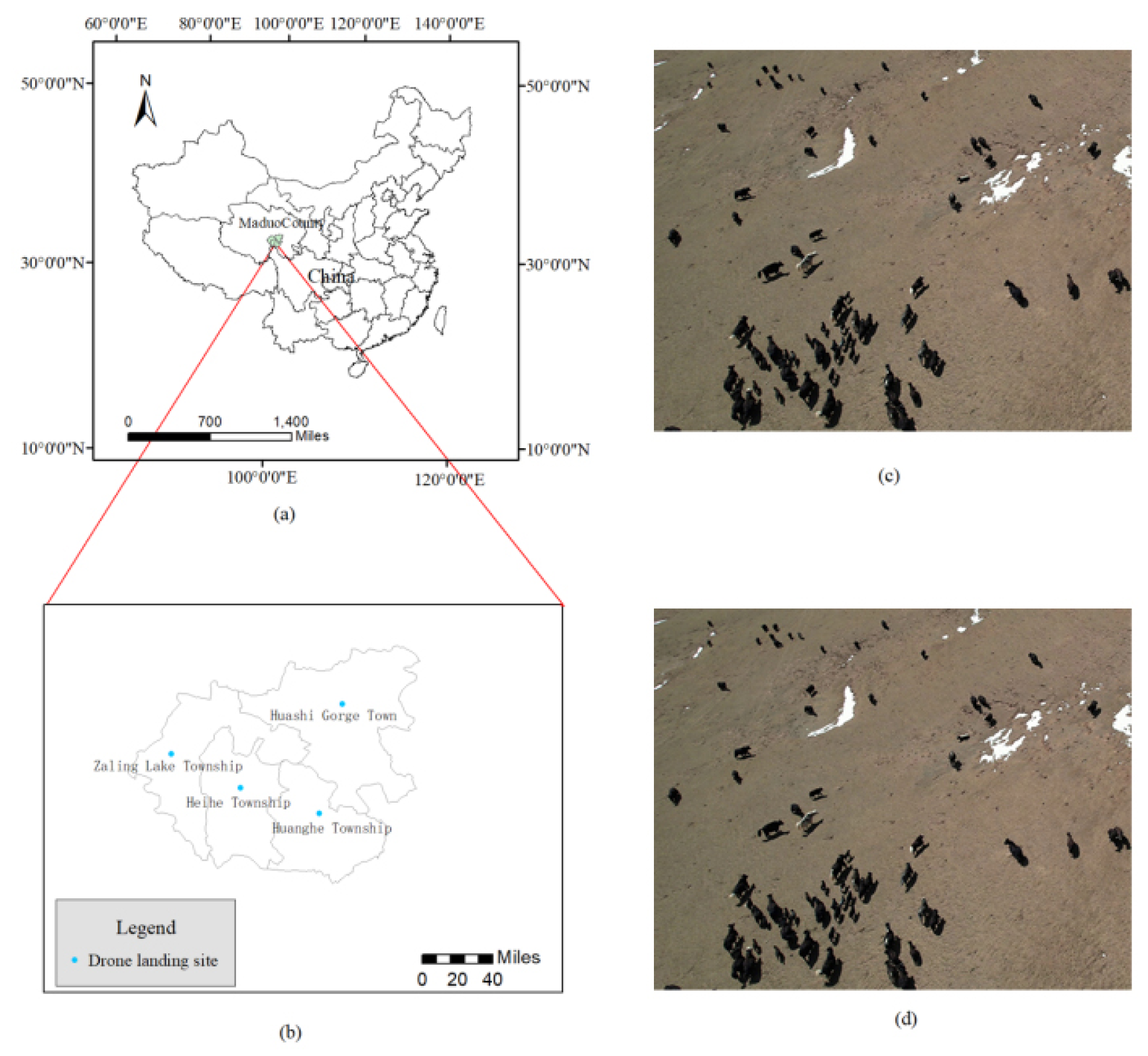

2.1. Area and objects of study

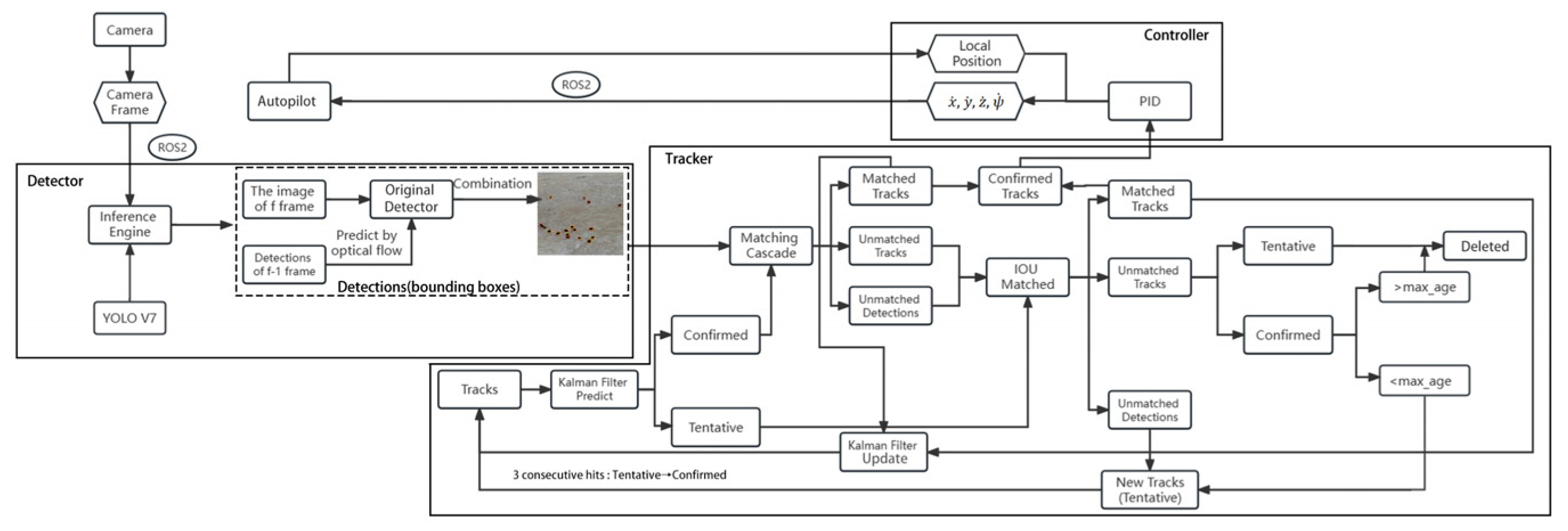

2.2. System overview

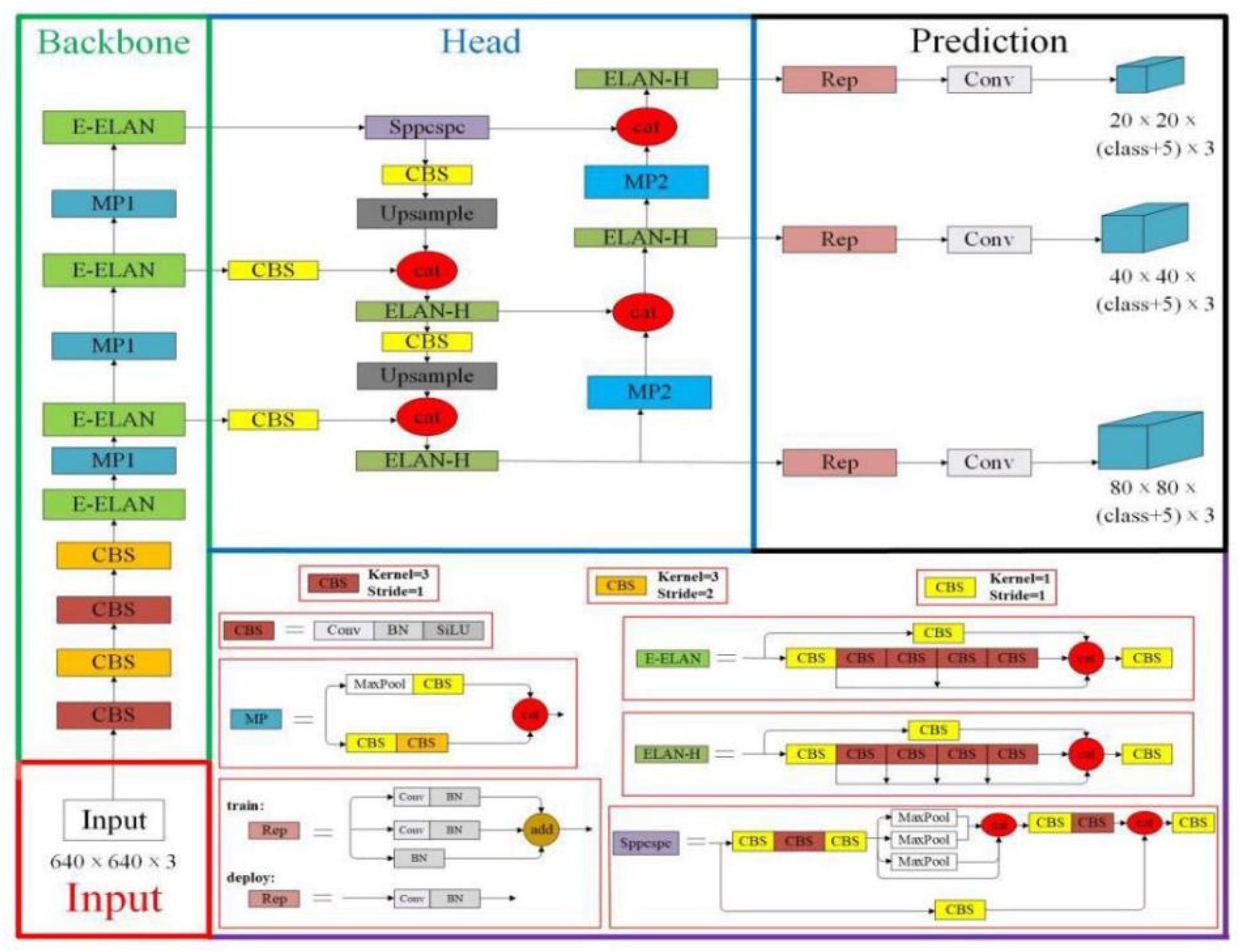

2.3. Detector

2.4. Tracker

2.4.1. Object tracking method

2.4.2. Combination of KF and optical flow

2.4.3. Filtering of low confidence tracks

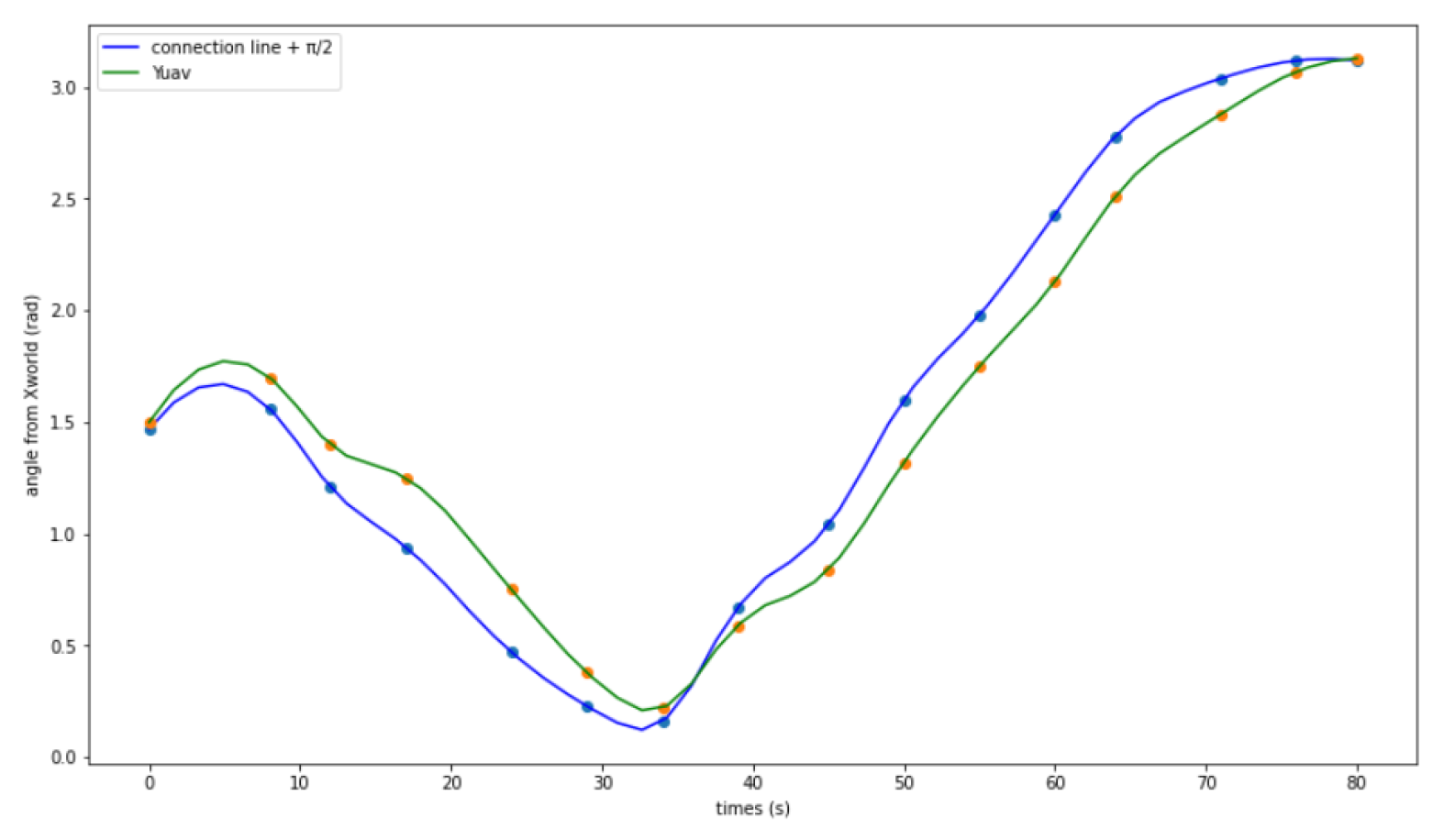

2.5. Visual servo control

3. Results

3.1. Metrics for tracking

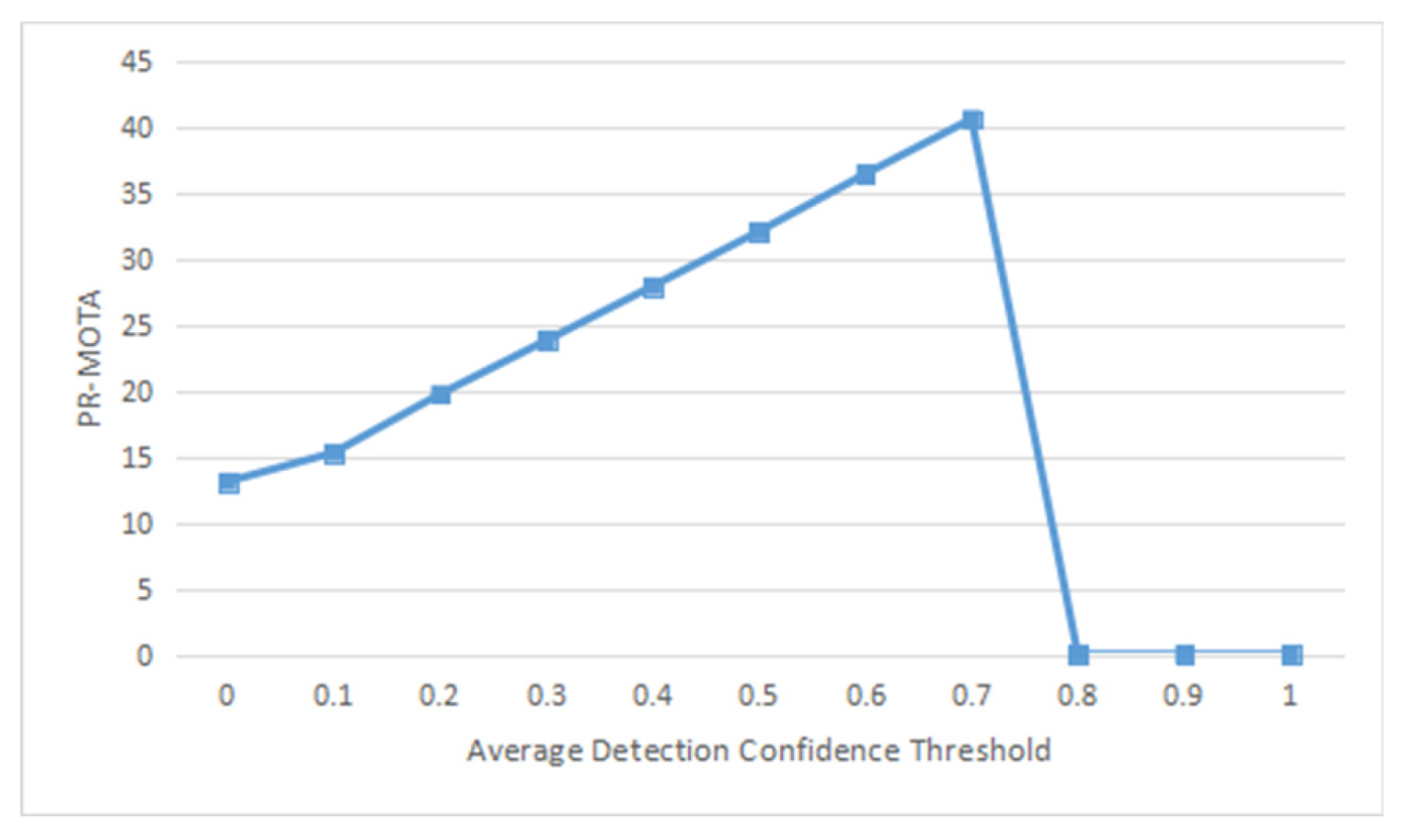

- PR-MOTP: It is derived from the values of precision and recall under different confidence thresholds. MOTP is the multi-target tracking accuracy , which is a measure of the tracker's ability to estimate the target position.

- PR-MT: It is originated from the values of precision and recall for different confidence thresholds. MT is the number of primary tracking traces that are successfully tracked during at least 80% of the target’s lifetime.

- PR-ML: It is derived from the values of precision and recall under different confidence thresholds. ML is the quantity of the mostly lost tracks that are not successfully tracked during minimum 20% of the target's lifetime.

- PR-FP: It is the total quantity of FPs.

- PR-FN: It means total quantity of FNs (target not met).

- PR-FM: With different confidence thresholds, the PR-FM is derived from the values of precision and recall. FM is the times of interruption for a track due to missing detection.

- PR-IDSw: It is found under different confidence thresholds based on the values of precision and recall. IDSw, also known as IDs, is the times of the IDs switch for the same target due to misjudgment of the tracking algorithm. The ideal IDs in the tracking algorithm should be 0. It is the total number of identity switches.

3.2. Evaluation of benchmarks

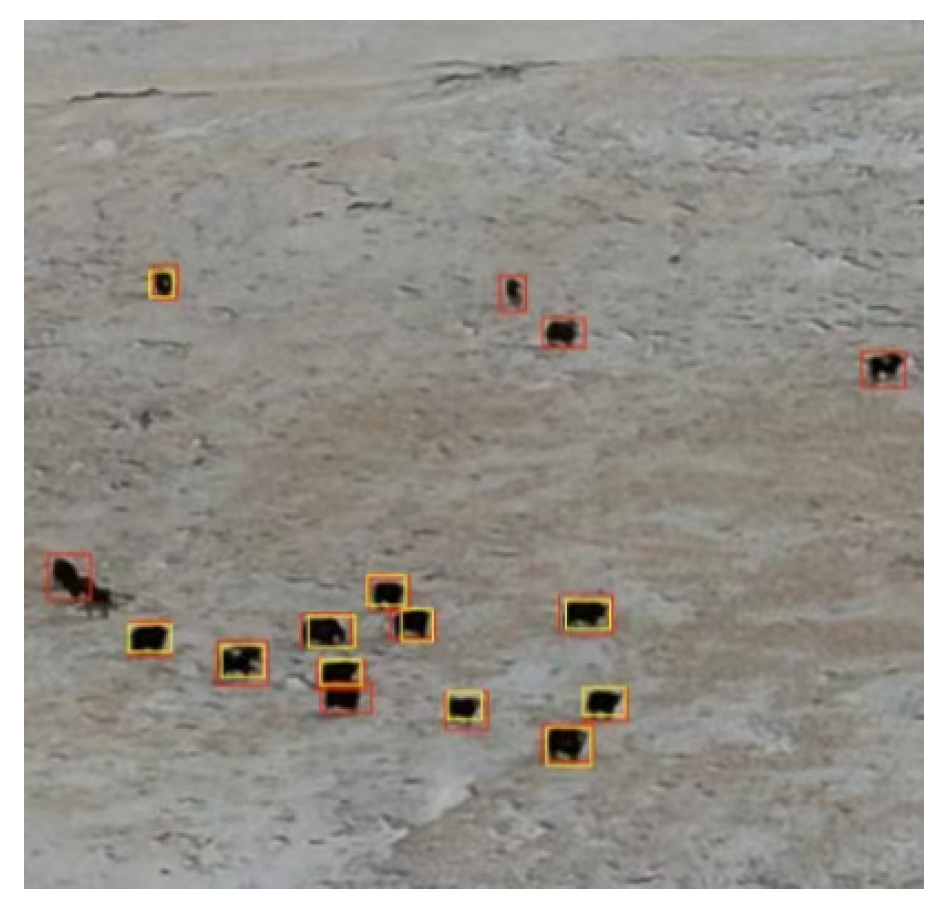

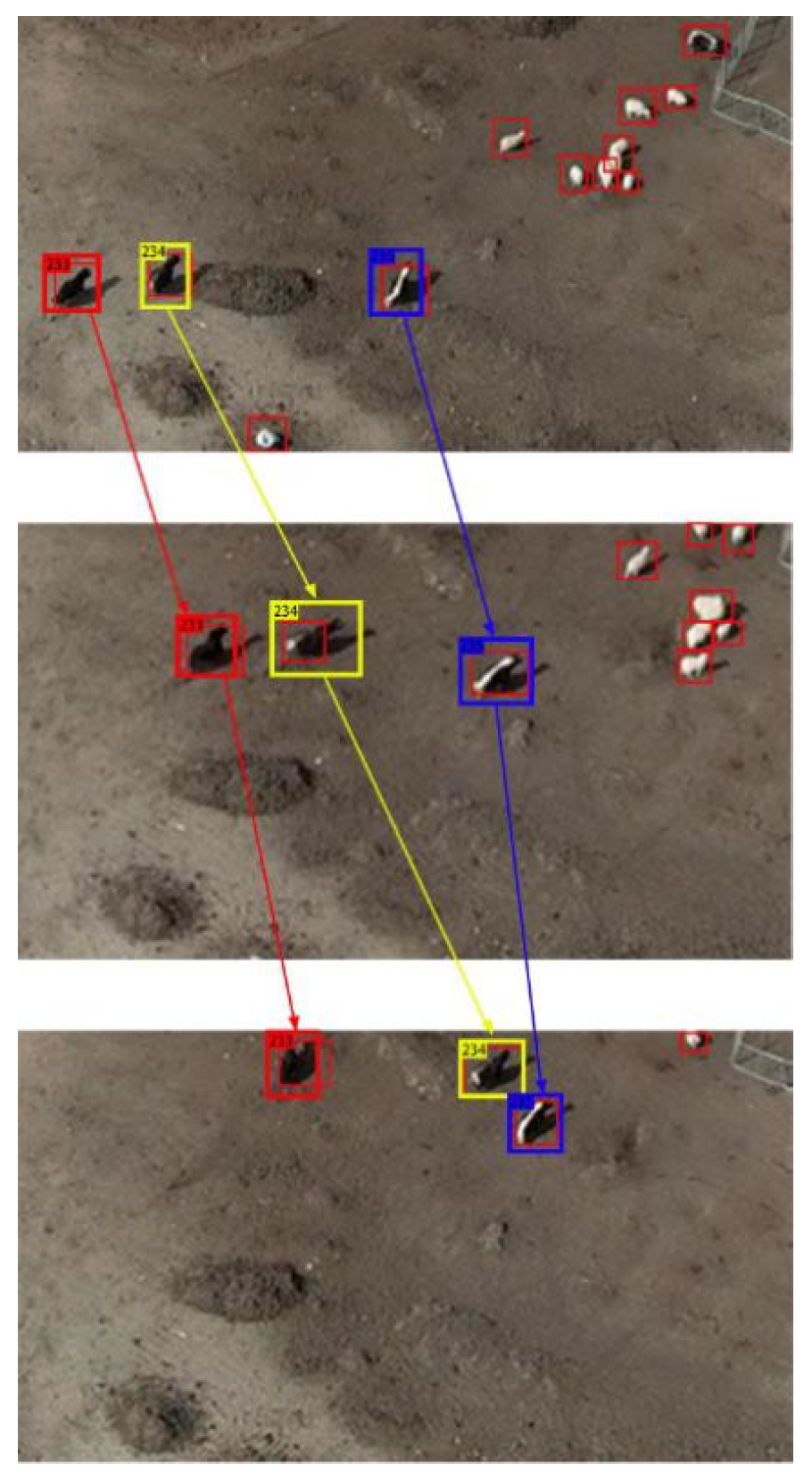

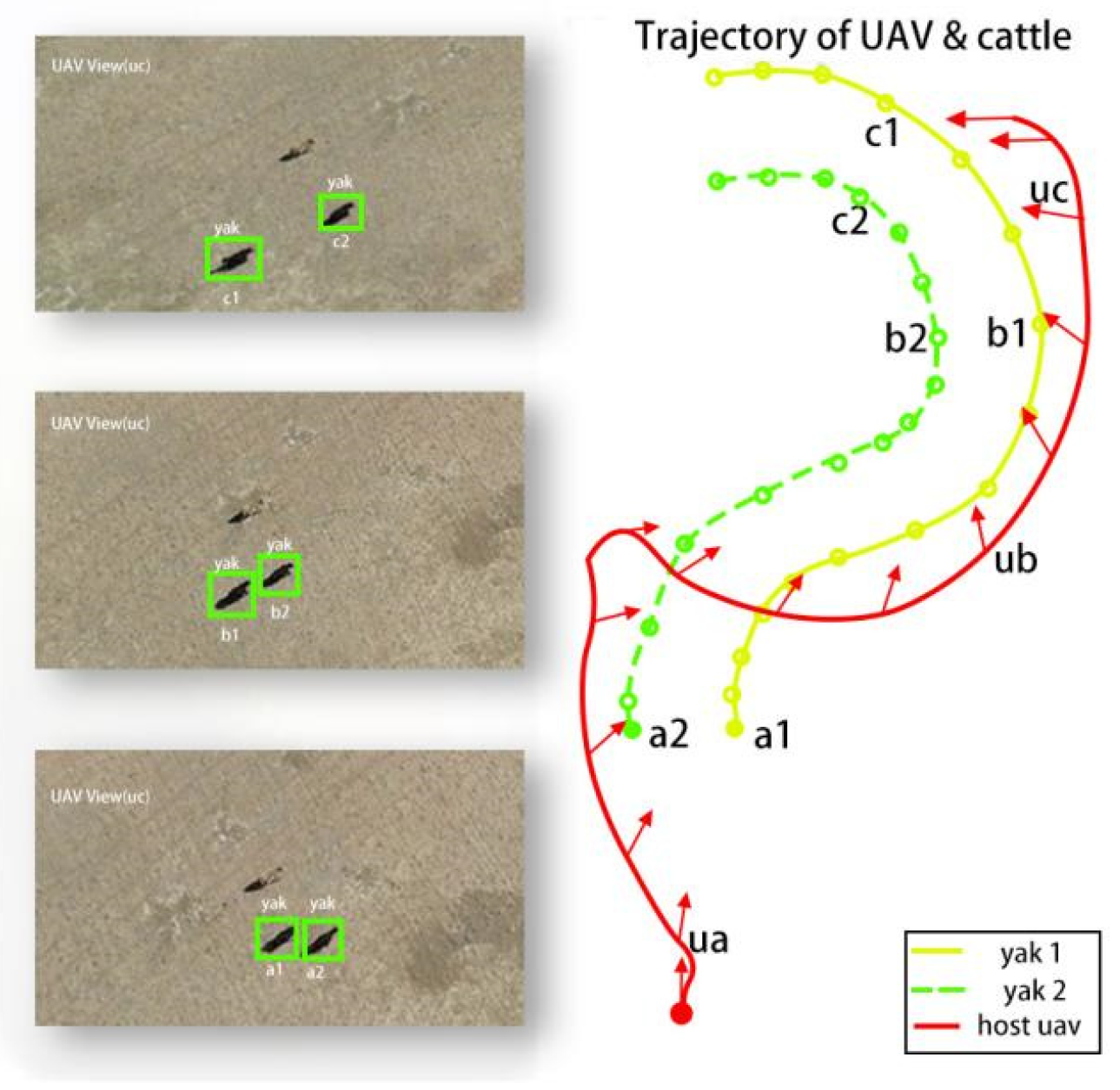

3.3. Validation in actual scenarios

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Data availability

Acknowledgments

Declaration of competing interest

Appendix A

| Algorithm Low Confidence Track Filtering |

|

; . . 1: for sequential frames do 2: do 3: if then 4: hits = 0 5: total_prob = 0 6: hits = hits + 1 7: 8: then 9: then 10: 11: else 12: |

References

- Andrew William, Gao Jing, Mullan Siobhan, Campbell Neill, Dowsey Andrew W., Burghardt Tilo. Visual identification of individual Holstein-Friesian cattle via deep metric learning. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2021, 185. [CrossRef]

- Altuˇg, E., Ostrowski, J.P., Mahony, R.: Control of a quadrotor helicopter using visual feedback. In: Proceedings of the 2002 IEEE International Conference on Robotics & Automation. Washington, DC, 2002. [CrossRef]

- Altuˇg, E., Ostrowski, J.P., Taylor, J.: Control of a quadrotor helicopter using dual camera visual feedback. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2005, 24, 329–341. [CrossRef]

- Ardö, H.; Guzhva, O.; Nilsson, M. A CNN-based cow interaction watchdog. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference Pattern Recognition, Cancun, Mexico, 4–8 December 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Azinheira, J.R., Rives, P., Carvalho, J.R.H., Silveira, G.F., de Paiva, E.D., Bueno, S.S.: Visual servo control for the hovering of an outdoor robotic airship. ICRA 2002, 3, 2787–2792. [CrossRef]

- Baraniuk, R., Donoho, D., & Gavish, M. The science of deep learning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2020, 117, 30029–30032. [CrossRef]

- Barrett H., & Rose D.C. Perceptions of the fourth agricultural revolution: What’s in, what’s out, and what consequences are anticipated? Sociologia Ruralis 2020, 60, 631–652. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/soru.12324. [CrossRef]

- Behrendt, K.; Novak, L.; Botros, R. A Deep Learning Approach to Traffic Lights: Detection, Tracking, and Classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Singapore, 29 May–3 June 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewley, A.; Ge, Z.; Ott, L.; Ramos, F.; Upcroft, B. Simple online and realtime tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Phoenix, AZ, USA, 25–28 September 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourquardez, O., Chaumette, F. Visual Servoing of an Airplane for Auto-landing. IROS, San Diego, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Chabot, D., & Bird, D. M. Wildlife research and management methods in the 21st century: Where do unmanned aircraft fit in? Journal of Unmanned Vehicle Systems 2015, 3, 137–155. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ai, H.; Zhuang, Z.; Shang, C. Real-Time Multiple People Tracking with Deeply Learned Candidate Selection and Person Re-Identification. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME), San Diego, CA, USA, 23–27 July 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaparrone, G.; Sánchez, F.L.; Tabik, S.; Troiano, L.; Tagliaferri, R.; Herrera, F. Deep learning in video multi-object tracking: A survey. Neurocomputing 2020, 381, 61–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, E., Winsen, M., Sudholz, A., & Hamilton, G. Automated detection of wildlife using drones: Synthesis, opportunities and constraints. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2021, 12, 674–687. [CrossRef]

- David Christian Rose, Rebecca Wheeler, Michael Winter, Matt Lobley, Charlotte-Anne Chivers, Agriculture 4.0: Making it work for people, production, and the planet. Land Use Policy 2021, 100, 104933. [CrossRef]

- Dollár, Piotr.; Mannat, Singh.; Ross, Girshick. Fast and accurate model scaling. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2021; pp. 924-932. [CrossRef]

- E. Bochinski, V. E. Bochinski, V. Eiselein, and T. Sikora. High-speed tracking-by-detection without using image information. In International Workshop on Traffic and Street Surveillance for Safety and Security at IEEE AVSS 2017, Lecce, Italy, Aug. 2017. 1, 5.

- Ess, A.; Schindler, K.; Leibe, B.; Gool, L.V. Object Detection and Tracking for Autonomous Navigation in Dynamic Environments. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2010, 29, 1707–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J., Burghardt, T., Andrew, W., Dowsey, A. W., & Campbell, N. W. Towards Self-Supervision for Video Identification of Individual Holstein-Friesian Cattle: The Cows2021 Dataset. Paper presented at Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshop on Computer Vision for Animal Behavior Tracking and Modeling (CV4Animals). 2021. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2105.01938. [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Lu, J.; Li, H.; Mottaghi, R.; Kembhavi, A. Container: Context aggregation network. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.01401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z., Pan, Y., Sun, T., Zhang, Y., and Xiao, X., “Adaptive neural network control of serial variable stiffness actuators,” Complexity 2017, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Hamel, T., Mahony, R.: Visual servoing of an under actuated dynamic rigid-body system: An image-based approach. IEEE Trans. Robot. Autom. 2002, 18, 187–198. [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Tao, P.; Martin, R.R. Livestock detection in aerial images using a fully convolutional network. Comput. Vis. Media 2019, 5, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Huang, Z.; Wang, N.; Zhang, Z. Learnable Graph Matching: Incorporating Graph Partitioning with Deep Feature Learning for Multiple Object Tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Pirsiavash, D. Ramanan, and C. C. Fowlkes. Globally-optimal greedy algorithms for tracking a variable number of objects. In CVPR 2011, pages 1201–1208, June 2011. 5. 20 June. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Hong, J.; Sattar, J. Person-following by autonomous robots: A categorical overview. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2019, 38, 1581–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jellason, N.P.; Robinson, E.J.Z.; Ogbaga, C.C. Agriculture 4.0: Is Sub-Saharan Africa Ready? Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez López, J., & Mulero-Pázmány, M. Drones for conservation in protected areas: Present and future. Drones 2019, 3, 10. [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Guan, S. Online Multi-object Tracking with Siamese Network and Optical Flow. In Proceedings of the IEEE 5th International Conference on Image, Vision and Computing (ICIVC), Beijing, China, 10–12 July 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, R.; Chemmanam, A.J.; Jose, B.; Mathews, S.; Varghese, E. Construction Safety Surveillance Using Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Networks, Computers and Communications (ISNCC), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–22 October 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kershenbaum, A., Blumstein, D. T., Roch, M. A., Akçay Ç., Backus G., Bee MA., Bohn K., Cao Y., Carter G., Cäsar C., Coen M., DeRuiter SL., Doyle L., Edelman S., Ferrer-i-Cancho R., Freeberg TM., Garland EC., Gustison ML., Harley HE., Huetz C., Hughes M., Bruno JHJr.. Ilany A., Jin DZ., Johnson M., Ju C., Karnowski J., Lohr B., Manser MB., McCowan B., Mercado E III.. Narins PM.. Piel A.. Rice M.. Salmi R.. Sasahara K.. Sayigh L.. Shiu Y.. Taylor C.. Vallejo EE.. Waller S.& Zamora-Gutierrez V. Acoustic sequences in non-human animals: A tutorial review and prospectus. Biological Reviews, 2020; 95, 13–52. [CrossRef]

- K. He, G. Gkioxari, P. Doll´ar, and R. B. Girshick.Mask R-CNN. CoRR, abs/1703.06870, 2017. 4, 5. 4.

- Krul, S.; Pantos, C.; Frangulea, M.; Valente, J. Visual SLAM for Indoor Livestock and Farming Using a Small Drone with a Monocular Camera: A Feasibility Study. Drones 2021, 5, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, H.W. The Hungarian method for the assignment problem. Nav. Res. Logist. Q. 1955, 2, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, E. Multiple Object Tracking via Feature Pyramid Siamese Networks. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 8181–8194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Chesser, G.D., Jr.; Purswell, J.L.; Linhoss, J.; Zhao, Y. Practices and Applications of Convolutional Neural Network-Based Computer Vision Systems in Animal Farming: A Review. Sensors 2021, 21, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, T.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.B.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature Pyramid Networks for Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. and Yuqiang Yao. “Real-time Multiple Objects Following Using a UAV.” AIAA SCITECH 2023 Forum 2023: n. pag. [CrossRef]

- Lo, S.; Yamane, K.; Sugiyama, K. Perception of Pedestrian Avoidance Strategies of a Self-Balancing Mobile Robot. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Macau, China, 4–8 November 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, B.; Kanade, T. An Iterative Image Registration Technique with an Application to Stereo Vision. In Proceedings of the 7th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–28 August 1981. [Google Scholar]

- L. Wang, Y. Lu, H. Wang, Y. Zheng, H. Ye, and X. Xue. Evolving boxes for fast vehicle detection. In IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME), 2017, 1135–1140. [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Li, X.; Zhang, G.; Shao, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Li, D.; Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, Y.; et al. High-Accuracy and Low-Latency Tracker for UAVs Monitoring Tibetan Antelopes. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Zhao, Y.; Shao, Q.; Li, X.; Wang, D.; Zhang, T.; Liu, F.; Duan, L.; He, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Procapra Przewalskii Tracking Autonomous Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Based on Improved Long and Short-Term Memory Kalman Filters. Sensors 2023, 23, 3948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, P.; Wei, G.; Wang, D.; Li, X.; Shao, Q.; He, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Z.; et al. Intelligent Grazing UAV Based on Airborne Depth Reasoning. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie Weygandt Mathis, Alexander Mathis, Deep learning tools for the measurement of animal behavior in neuroscience, Current Opinion in Neurobiology 2020, 60, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z., and Sun, G., Dual terminal sliding mode control design for rigid robotic manipulator. Journal ofthe Franklin Institute 2018, 355, 9127–9149. [CrossRef]

- Milan, A.; Leal-Taixé, L.; Reid, I.D.; Roth, S.; Schindler, K. MOT16: A benchmark for multi-object tracking. arXiv arXiv:1603.00831, 2016.

- Mohd Javaid, Abid Haleem, Ravi Pratap Singh, Rajiv Suman, Enhancing smart farming through the applications of Agriculture 4.0 technologies. International Journal of Intelligent Networks 2022, 3, 150–164. [CrossRef]

- Norouzzadeh, M. S., Nguyen, A., Kosmala, M., Swanson, A., Palmer, M. S., Packer, C., & Clune, J. Automatically identifying, counting, and describing wild animals in camera-trap images with deep learning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115, E5716–E5725. [CrossRef]

- NVIDIA, “NVIDIA TensorRT”, 2021. Available online: https://developer.nvidia.com/tensorrt.

- Pereira, T. D., Aldarondo, D. E., Willmore, L., Kislin, M., Wang, S. S.-H., Murthy, M., & Shaevitz, J. W. Fast animal pose estimation using deep neural networks. Nature Methods 2020, 17, 59–62. [CrossRef]

- Proctor, A.A., Johnson, E.N., Apker, T.B.: Visiononly control and guidance for aircraft. J. Field Robot. 2006, 23, 863–890. [CrossRef]

- R. B. Girshick, J. Donahue, T. Darrell, and J. Malik.Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. CoRR, abs/1311.2524,2013. 5. [CrossRef]

- Romero, H., Benosman, R., Lozano, R.: Stabilizational Location of a Four Rotor Helicopter Applying Vision, pp. 3930–3936. ACC, Minneapolis 2006.

- Schad, L., & Fischer, J. Opportunities and risks in the use of drones for studying animal behaviour. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2022, 13, 3–16. [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, R. G., Elumalai, V. K., Karuppusamy, S., and Canchi, V. K., “Uniform ultimate bounded robust model reference adaptive PID control scheme for visual servoing. Journal ofthe Franklin Institute 2017, 354, 1741–1758. [CrossRef]

- Sukhatme, G.S., Mejias, L., Saripalli, S., Campoy, P.: Visual servoing of an autonomous helicopter in urban areas using feature tracking. J. Field Robot. 2006, 23, 185–199. [CrossRef]

- Vasu, P.K.A.; Gabriel, J.; Zhu, J.; Tuzel, O.; Ranjan, A. An improved one millisecond mobile backbone. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.04040, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. “TensorRTx”, 2021. Available online: https://github.com/wang-xinyu/tensorrtx.

- W. Andrew, C. Greatwood and T. Burghardt, "Aerial Animal Biometrics: Individual Friesian Cattle Recovery and Visual Identification via an Autonomous UAV with Onboard Deep Inference," 2019 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Macau, China, 2019, pp. 237-243. [CrossRef]

- W. Andrew, C. Greatwood and T. Burghardt, "Deep Learning for Exploration and Recovery of Uncharted and Dynamic Targets from UAV-like Vision," 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Madrid, Spain, 2018, pp. 1124-1131. [CrossRef]

- W. Andrew, C. Greatwood and T. Burghardt, "Visual Localisation and Individual Identification of Holstein Friesian Cattle via Deep Learning," 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW), Venice, Italy, 2017, pp. 2850-2859. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Bertinetto, L.; Hu, W.; Torr, P.H. Fast Online Object Tracking and Segmentation: A Unifying Approach. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–20 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wojke, N.; Bewley, A.; Paulus, D. Simple Online and Realtime Tracking with a Deep Association Metric. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Beijing, China, 17–20 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, A.D., Johnson, E.N., Proctor, A.A.: Vision-aided inertial navigation for flight control. In: AIAA Guidance, Navigation and Control Conf. and Exhibit, San Francisco, USA, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Xiaohui Li, Li Xing, Use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles for Livestock Monitoring based on Streaming K-Means Clustering. 6th IFAC Conference on Sensing, Control and Automation Technologies for Agriculture AGRICONTROL 2019, Volume 52, Issue 30, 2019, 324-329. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Osep, A.; Ban, Y.; Horaud, R.; Leal-Taixe, L.; Alameda-Pineda, X. How To Train Your Deep Multi-Object Tracker. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Z. Cai, M. J. Saberian, and N. Vasconcelos. Learning complexity-aware cascades for deep pedestrian detection. CoRR, abs/1507.05348, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D., and Wei, B., “A review on model reference adaptive control of robotic manipulators. Annual Reviews in Control 2017, 43, 188–198. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cai, J.; Xiao, D.; Li, Z.; Xiong, B. Real-time sow behavior detection based on deep learning. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 163, 104884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Elmore, J.A.; Samiappan, S.; Evans, K.O.; Pfeiffer, M.B.; Blackwell, B.F.; Iglay, R.B. Improving Animal Monitoring Using Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems (sUAS) and Deep Learning Networks. Sensors 2021, 21, 5697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Chen, C.; Zheng, B.; Yang, X.; Gan, H.; Zheng, C.; Yang, A.; Mao, L.; Xue, Y. Automatic recognition of lactating sow postures by refifined two-stream RGB-D faster R-CNN. Biosyst. Eng. 2020, 189, 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tracker | Detector | Method | PR-MOTA | PR-MOTP | PR-MT | PR-ML | PR-FM | PR-FP | PR-FN | PR-IDs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOU [17] | R-CNN [53] | Batch | 18.3% | 41.9% | 14.3% | 20.6% | 523 | 2313.5 | 19845.1 | 513 |

| IOU [17] | Comp ACT [68] | Batch | 18.4% | 41.3% | 14.7% | 20.1% | 379 | 2459.2 | 17125.6 | 245 |

| IOU [17] | EB [41] | Batch | 23.5% | 33.2% | 17.5% | 16..7 | 248 | 1456.6 | 17054.4 | 233 |

| IOU [17] | YOLOv7 | Batch | 33.8% | 40.2% | 34.6% | 19.4% | 88 | 1731.5 | 17945.5 | 70 |

| Deep SORT | EB [41] | Online | 20.6% | 45.3% | 18.1% | 17.2% | 201 | 3501.9 | 16874.5 | 180 |

| Ours | EB [41] | Online | 22.9% | 45.3% | 17.8% | 17.3% | 205 | 2009.7 | 17012.4 | 166 |

| Deep SORT | YOLOv7 | Online | 30.4% | 39.1% | 34.3% | 18.5% | 159 | 6456.6 | 16456.7 | 245 |

| Ours | YOLOv7 | Online | 33.6% | 39.2% | 32.9% | 19.7% | 126 | 2013.1 | 17913.2 | 198 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).