Submitted:

26 May 2025

Posted:

26 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Stressors in Aquaculture

3. Neurotransmitters and Neuroendocrine Systems Respond to Stress in Fish

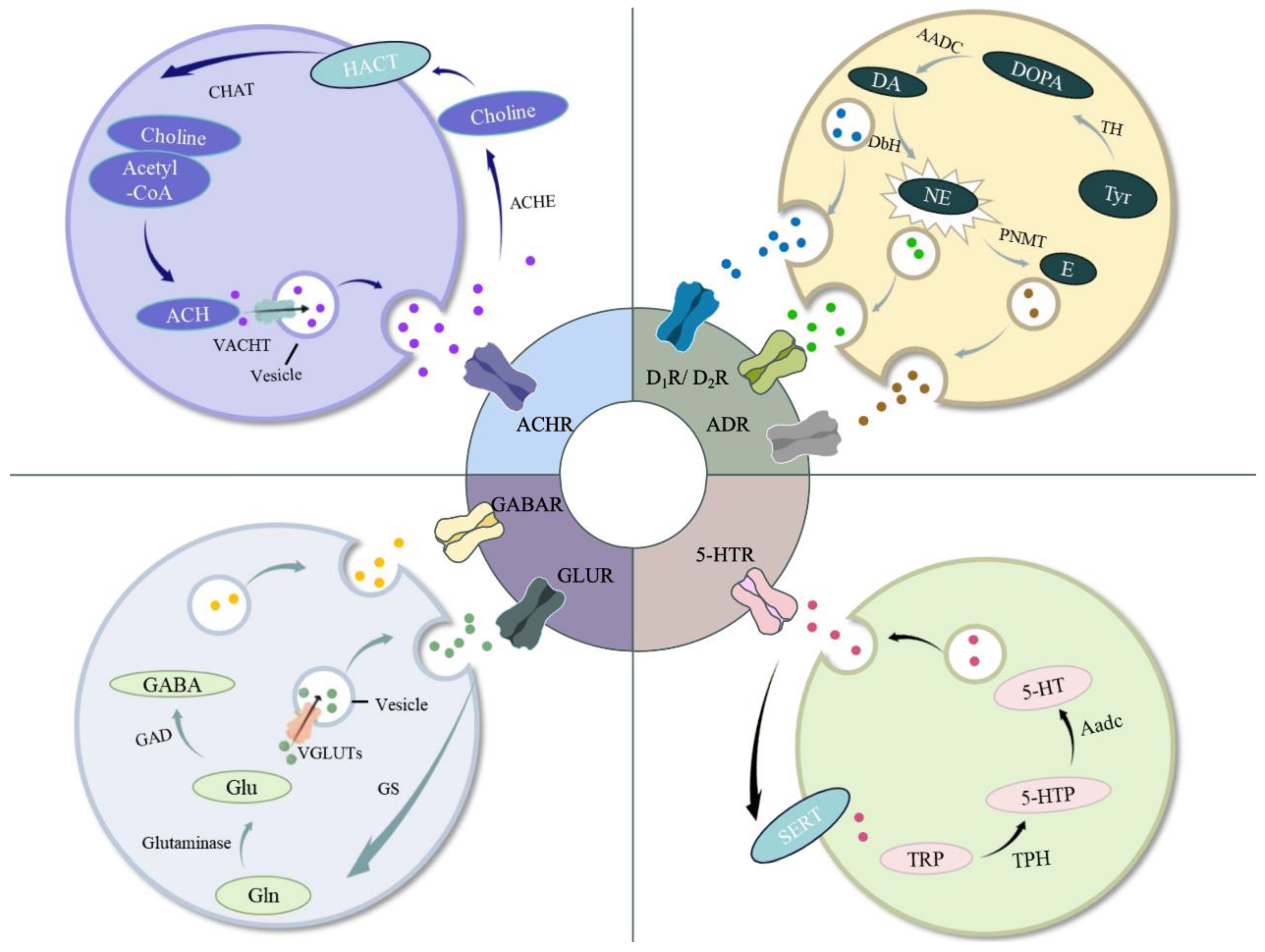

3.1. Neurotransmitters During Stress

3.1.1. Acetylcholine (ACh)

3.1.2. Glutamate (Glu) and Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA)

3.1.3. Catecholamine (CA)

3.1.4. Serotonin

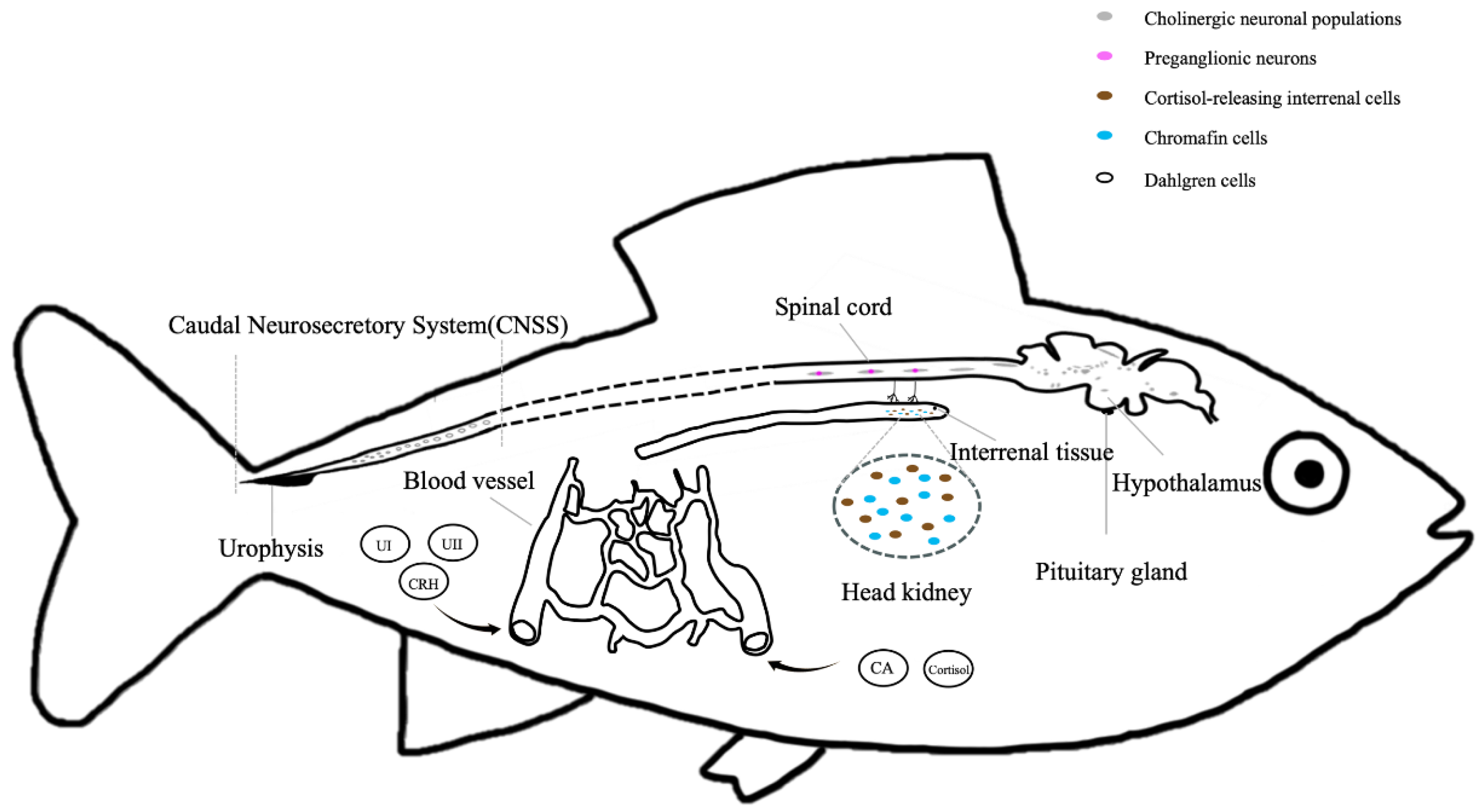

3.2. Neuroendocrine Systems During Stress

Brain-Sympathetic-Chromaffin Cells (BSC) Axis

3.3. Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Interrenal (HPI) Axis

3.4. Caudal Neurosecretory System (CNSS)

4. Dietary Supplements on Stress Mitigation Through Neuroendocrine and Neurotransmitters Regulations

4.1. Nutritional Supplements

4.2. Non-Nutritional Supplements

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Data availability statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest Statement

References

- C. E. Boyd, A.A. McNevin, R.P. Davis, The contribution of fisheries and aquaculture to the global protein supply. Food Secur 2022, 14, 805–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R. L. Naylor, R.W. Hardy, A.H. Buschmann, S.R. Bush, L. Cao, D.H. Klinger, D.C. Little, J. Lubchenco, S.E. Shumway, M. Troell, A 20-year retrospective review of global aquaculture. Nature 2021, 591, 551–563. [Google Scholar]

- Agorastos, G.P. Chrousos, The neuroendocrinology of stress: the stress-related continuum of chronic disease development. Mol Psychiatry 2022, 27, 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. M. Koolhaas, A. Bartolomucci, B. Buwalda, S.F. de Boer, G. Flugge, S.M. Korte, P. Meerlo, R. Murison, B. Olivier, P. Palanza, G. Richter-Levin, A. Sgoifo, T. Steimer, O. Stiedl, G. van Dijk, M. Wohr, E. Fuchs, Stress revisited: a critical evaluation of the stress concept. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2011, 35, 1291–1301. [Google Scholar]

- E.C. Urbinati, F.S. E.C. Urbinati, F.S. Zanuzzo, J.D. Biller, Stress and immune system in fish, Biology and physiology of freshwater neotropical fish, Elsevier2020, pp. 93-114.

- G. Nardocci, C. Navarro, P.P. Cortes, M. Imarai, M. Montoya, B. Valenzuela, P. Jara, C. Acuna-Castillo, R. Fernandez, Neuroendocrine mechanisms for immune system regulation during stress in fish. Fish & shellfish immunology 2014, 40, 531–538. [Google Scholar]

- F. S. Dhabhar, The short-term stress response - Mother nature’s mechanism for enhancing protection and performance under conditions of threat, challenge, and opportunity. Front Neuroendocrinol 2018, 49, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Boonstra, C. Fox, Reality as the leading cause of stress: rethinking the impact of chronic stress in nature. Functional Ecology 2012, 27, 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- D.H. Evans, J.B. D.H. Evans, J.B. Claiborne, S. Currie, The physiology of fishes: Fourth edition, CRC Press, New York, 2013.

- R. Raman, C. Prakash, M. Makesh, N. Pawar, Environmental stress mediated diseases of fish: an overview. Adv Fish Res 2013, 5, 141–158. [Google Scholar]

- S. S.U.H. Kazmi, Y.Y.L. Wang, Y.-E. Cai, Z. Wang, Temperature effects in single or combined with chemicals to the aquatic organisms: An overview of thermo-chemical stress. Ecological Indicators 2022, 143, 109354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. L. Pfau, S.J. Russo, Peripheral and Central Mechanisms of Stress Resilience. Neurobiol Stress 2015, 1, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Rima, Y. Lattouf, M. Abi Younes, E. Bullier, P. Legendre, J.M. Mangin, E. Hong, Dynamic regulation of the cholinergic system in the spinal central nervous system. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 15338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- X. Gu, X. Wang, An overview of recent analysis and detection of acetylcholine. Anal Biochem 2021, 632, 114381. [Google Scholar]

- Y. S. Mineur, T.N. Mose, L. Vanopdenbosch, I.M. Etherington, C. Ogbejesi, A. Islam, C.M. Pineda, R.B. Crouse, W. Zhou, D.C. Thompson, M.P. Bentham, M.R. Picciotto, Hippocampal acetylcholine modulates stress-related behaviors independent of specific cholinergic inputs. Mol Psychiatry 2022, 27, 1829–1838. [Google Scholar]

- S. Yang, T. Yan, L. Zhao, H. Wu, Z. Du, T. Yan, Q. Xiao, Effects of temperature on activities of antioxidant enzymes and Na(+)/K(+)-ATPase, and hormone levels in Schizothorax prenanti. J Therm Biol 2018, 72, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Sarasamma, G. S. Sarasamma, G. Audira, S. Juniardi, B.P. Sampurna, S.-T. Liang, E. Hao, Y.-H. Lai, C.-D. Hsiao, Zinc Chloride Exposure Inhibits Brain Acetylcholine Levels, Produces Neurotoxic Signatures, and Diminishes Memory and Motor Activities in Adult Zebrafish. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2018.

- Szabo, J. Nemcsok, P. Kasa, D. Budai, Comparative study of acetylcholine synthesis in organs of freshwater teleosts. Fish Physiol Biochem 1991, 9, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Bejaoui, I. Chetoui, F. Ghribi, D. Belhassen, B.B. Abdallah, C.B. Fayala, S. Boubaker, S. Mili, N. Soudani, Exposure to different cobalt chloride levels produces oxidative stress and lipidomic changes and affects the liver structure of Cyprinus carpio juveniles. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2024, 31, 51658–51672. [Google Scholar]

- S. J. Woo, J.K. Chung, Effects of trichlorfon on oxidative stress, neurotoxicity, and cortisol levels in common carp, Cyprinus carpio L., at different temperatures. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol 2020, 229, 108698. [Google Scholar]

- S. Ghosh, R. Bhattacharya, S. Pal, N.C. Saha, Benzalkonium chloride induced acute toxicity and its multifaceted implications on growth, hematological metrics, biochemical profiles, and stress-responsive biomarkers in tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus). Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2024, 31, 52147–52170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Deb, S. Das, Acetylcholine esterase and antioxidant responses in freshwater teleost, Channa punctata exposed to chlorpyrifos and urea. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol 2021, 240, 108912. [Google Scholar]

- V. C. Renick, K. Weinersmith, D.E. Vidal-Dorsch, T.W. Anderson, Effects of a pesticide and a parasite on neurological, endocrine, and behavioral responses of an estuarine fish. Aquat Toxicol 2016, 170, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. M. Villalba, A. De la Llave-Propin, J. De la Fuente, C. Perez, E.G. de Chavarri, M.T. Diaz, A. Cabezas, R. Gonzalez-Garoz, F. Torrent, M. Villarroel, R. Bermejo-Poza, Using underwater currents as an occupational enrichment method to improve the stress status in rainbow trout. Fish Physiol Biochem 2024, 50, 463–475. [Google Scholar]

- S. Kar, B. Senthilkumaran, Recent advances in understanding neurotoxicity, behavior and neurodegeneration in siluriformes. Aquaculture and Fisheries 2024, 9, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Jifa, Z. Yu, S. Xiuxian, W. You, Response of integrated biomarkers of fish (Lateolabrax japonicus) exposed to benzo[a]pyrene and sodium dodecylbenzene sulfonate. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2006, 65, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H.F. Olivares-Rubio, J.J. H.F. Olivares-Rubio, J.J. Espinosa-Aguirre, Acetylcholinesterase activity in fish species exposed to crude oil hydrocarbons: A review and new perspectives. Chemosphere, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- T. Zhao, L. Zheng, Q. Zhang, S. Wang, Q. Zhao, G. Su, M. Zhao, Stability towards the gastrointestinal simulated digestion and bioactivity of PAYCS and its digestive product PAY with cognitive improving properties. Food Funct 2019, 10, 2439–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzualde, O. Jaka, D. Latino, O. Alijevic, I. Iturria, J.H. de Mendoza, P. Pospisil, S. Frentzel, M.C. Peitsch, J. Hoeng, K. Koshibu, Effects of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor-activating alkaloids on anxiety-like behavior in zebrafish. J Nat Med 2021, 75, 926–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. G. Santos da Rosa, H.H. Alcantara Barcellos, M. Fagundes, C. Variani, M. Rossini, F. Kalichak, G. Koakoski, T. Acosta Oliveira, R. Idalencio, R. Frandoloso, A.L. Piato, L. Jose Gil Barcellos, Muscarinic receptors mediate the endocrine-disrupting effects of an organophosphorus insecticide in zebrafish. Environ Toxicol 2017, 32, 1964–1972. [Google Scholar]

- J. Du, X.H. Li, Y.J. Li, Glutamate in peripheral organs: Biology and pharmacology. Eur J Pharmacol 2016, 784, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Harada, H. Matsuoka, H. Fujihara, Y. Ueta, Y. Yanagawa, M. Inoue, GABA Signaling and Neuroactive Steroids in Adrenal Medullary Chromaffin Cells. Front Cell Neurosci 2016, 10, 100. [Google Scholar]

- D. Zhang, Z. Hua, Z. Li, The role of glutamate and glutamine metabolism and related transporters in nerve cells. CNS Neurosci Ther 2024, 30, e14617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Sprengel, A. R. Sprengel, A. Eltokhi, Ionotropic Glutamate Receptors (and Their Role in Health and Disease), in: D.W. Pfaff, N.D. Volkow, J.L. Rubenstein (Eds.), Neuroscience in the 21st Century, Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2022, pp. 57-86.

- K. T. Lee, H.S. Liao, M.H. Hsieh, Glutamine Metabolism, Sensing and Signaling in Plants. Plant Cell Physiol 2023, 64, 1466–1481. [Google Scholar]

- Z. Heli, C. Hongyu, B. Dapeng, T. Yee Shin, Z. Yejun, Z. Xi, W. Yingying, Recent advances of gamma-aminobutyric acid: Physiological and immunity function, enrichment, and metabolic pathway. Front Nutr 2022, 9, 1076223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- N. Hossein-Javaheri, L.T. Buck, GABA receptor inhibition and severe hypoxia induce a paroxysmal depolarization shift in goldfish neurons. J Neurophysiol 2021, 125, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- N. J. Allen, D. Attwell, The effect of simulated ischaemia on spontaneous GABA release in area CA1 of the juvenile rat hippocampus. J Physiol 2004, 561, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. Jiang, X.Y. Wu, X.Q. Zhou, L. Feng, Y. Liu, W.D. Jiang, P. Wu, Y. Zhao, Glutamate ameliorates copper-induced oxidative injury by regulating antioxidant defences in fish intestine. Br J Nutr 2016, 116, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Wang, E. Li, Y. Huang, W. Liu, S. Wang, W. Li, L. Chen, X. Wang, Dietary supplementation with glutamate enhanced antioxidant capacity, ammonia detoxification and ion regulation ability in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) exposed to acute alkalinity stress. Aquaculture 2025, 594, 741360. [Google Scholar]

- L. Li, Z. Liu, J. Quan, J. Lu, G. Zhao, J. Sun, Metabonomics analysis reveals the protective effect of nano-selenium against heat stress of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). J Proteomics 2022, 259, 104545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Sun, C. Y. Sun, C. Geng, W. Liu, Y. Liu, L. Ding, P. Wang, Investigating the Impact of Disrupting the Glutamine Metabolism Pathway on Ammonia Excretion in Crucian Carp (Carassius auratus) under Carbonate Alkaline Stress Using Metabolomics Techniques, Antioxidants (Basel) 13(2) (2024).

- K. El-Naggar, S. El-Kassas, S.E. Abdo, A.A.K. Kirrella, R.A. Al Wakeel, Role of gamma-aminobutyric acid in regulating feed intake in commercial broilers reared under normal and heat stress conditions. J Therm Biol 2019, 84, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Sohrabipour, M.R. Sharifi, A. Talebi, M. Sharifi, N. Soltani, GABA dramatically improves glucose tolerance in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats fed with high-fat diet. Eur J Pharmacol 2018, 826, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Zhang, X. Wang, C. Wang, Y. Song, J. Pan, Q. Shi, J. Qin, L. Chen, Gamma-aminobutyric acid regulates glucose homeostasis and enhances the hepatopancreas health of juvenile Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis) under fasting stress. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2021, 303, 113704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. M. Ncho, A. Goel, V. Gupta, C.M. Jeong, Y.H. Choi, Embryonic manipulations modulate differential expressions of heat shock protein, fatty acid metabolism, and antioxidant-related genes in the liver of heat-stressed broilers. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0269748. [Google Scholar]

- J. Motiejunaite, L. Amar, E. Vidal-Petiot, Adrenergic receptors and cardiovascular effects of catecholamines. Ann Endocrinol 2021, 82, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- V. G. Barsagade, Dopamine system in the fish brain: A review on current knowledge. J Entomol Zool Stud 2020, 8, 2549–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Joyce, J. Warwicker, H.A. Shiels, S.F. Perry, Evolution and divergence of teleost adrenergic receptors: why sometimes ’the drugs don’t work’ in fish. J Exp Biol 2023, 226, jeb245859. [Google Scholar]

- C. C. Lapish, S. Ahn, L.M. Evangelista, K. So, J.K. Seamans, A.G. Phillips, Tolcapone enhances food-evoked dopamine efflux and executive memory processes mediated by the rat prefrontal cortex. Psychopharmacology 2009, 202, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. C. Jhou, Dopamine and anti-dopamine systems: polar opposite roles in behavior. The FASEB Journal 2013, 27, 80.2–802. [Google Scholar]

- K. Domschke, B. Winter, A. Gajewska, S. Unterecker, B. Warrings, A. Dlugos, S. Notzon, K. Nienhaus, F. Markulin, A. Gieselmann, C. Jacob, M.J. Herrmann, V. Arolt, A. Muhlberger, A. Reif, P. Pauli, J. Deckert, P. Zwanzger, Multilevel impact of the dopamine system on the emotion-potentiated startle reflex. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2015, 232, 1983–1993. [Google Scholar]

- J. Aerts, Quantification of a Glucocorticoid Profile in Non-pooled Samples Is Pivotal in Stress Research Across Vertebrates. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018, 9, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Vargas-Chacoff, J.L.P. Muñoz, D. Ocampo, K. Paschke, J.M. Navarro, The effect of alterations in salinity and temperature on neuroendocrine responses of the Antarctic fish Harpagifer antarcticus. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology 2019, 235, 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- S. Sreelekshmi, K. Manish, M.C. Subhash Peter, R. Moses Inbaraj, Analysis of neuroendocrine factors in response to conditional stress in zebrafish Danio rerio (Cypriniformes: Cyprinidae). Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol 2022, 252, 109242. [Google Scholar]

- W. Joyce, C.J.A. Williams, S. Iversen, P.G. Henriksen, M. Bayley, T. Wang, The effects of endogenous and exogenous catecholamines on hypoxic cardiac performance in red-bellied piranhas. J Exp Zool A Ecol Integr Physiol 2019, 331, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. N. Schoen, A.M. Weinrauch, I.A. Bouyoucos, J.R. Treberg, W. Gary Anderson, Hormonal effects on glucose and ketone metabolism in a perfused liver of an elasmobranch, the North Pacific spiny dogfish, Squalus suckleyi. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2024, 352, 114514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M.A. Lopez-Patino, A.K. M.A. Lopez-Patino, A.K. Skrzynska, F. Naderi, J.M. Mancera, J.M. Miguez, J.A. Martos-Sitcha, High Stocking Density and Food Deprivation Increase Brain Monoaminergic Activity in Gilthead Sea Bream (Sparus aurata). Animals (Basel) 11(6) (2021).

- J. Roy, F. J. Roy, F. Terrier, M. Marchand, A. Herman, C. Heraud, A. Surget, A. Lanuque, F. Sandres, L. Marandel, Effects of Low Stocking Densities on Zootechnical Parameters and Physiological Responses of Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Juveniles, Biology (Basel) 10(10) (2021).

- K. Kaur, R.K. Narang, S. Singh, AlCl(3) induced learning and memory deficit in zebrafish. Neurotoxicology 2022, 92, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. Bedrossiantz, M. Bellot, P. Dominguez-Garcia, M. Faria, E. Prats, C. Gomez-Canela, R. Lopez-Arnau, E. Escubedo, D. Raldua, A Zebrafish Model of Neurotoxicity by Binge-Like Methamphetamine Exposure. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 770319. [Google Scholar]

- M. H.B. Amador, M.D. McDonald, Is serotonin uptake by peripheral tissues sensitive to hypoxia exposure?. Fish Physiol Biochem 2022, 48, 617–630.

- Mardones, R. Oyarzun-Salazar, B.S. Labbe, J.M. Miguez, L. Vargas-Chacoff, J.L.P. Munoz, Intestinal variation of serotonin, melatonin, and digestive enzymes activities along food passage time through GIT in Salmo salar fed with supplemented diets with tryptophan and melatonin. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 2022, 266, 111159. [Google Scholar]

- E. Hoglund, O. Overli, S. Winberg, Tryptophan Metabolic Pathways and Brain Serotonergic Activity: A Comparative Review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019, 10, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Lillesaar, The serotonergic system in fish. J Chem Neuroanat 2011, 41, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Backstrom, S. Winberg, Serotonin Coordinates Responses to Social Stress-What We Can Learn from Fish. Front Neurosci 2017, 11, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Khan, P. Deschaux, Role of serotonin in fish immunomodulation. J Exp Biol 1997, 200, 1833–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. H. Lim, T. Soga, I.S. Parhar, Social stress-induced serotonin dysfunction activates spexin in male Nile tilapia (Oreochromis Niloticus). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2023, 120, e2117547120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Shams, D. Seguin, A. Facciol, D. Chatterjee, R. Gerlai, Effect of social isolation on anxiety-related behaviors, cortisol, and monoamines in adult zebrafish. Behav Neurosci 2017, 131, 492–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Y. Higuchi, T. Soga, I.S. Parhar, Social Defeat Stress Decreases mRNA for Monoamine Oxidase A and Increases 5-HT Turnover in the Brain of Male Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Front Pharmacol 2018, 9, 1549. [Google Scholar]

- D. Santos, A. Luzio, L. Felix, J. Bellas, S.M. Monteiro, Oxidative stress, apoptosis and serotonergic system changes in zebrafish (Danio rerio) gills after long-term exposure to microplastics and copper. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol 2022, 258, 109363. [Google Scholar]

- X. Gao, X. Wang, X. Wang, Y. Fang, S. Cao, B. Huang, H. Chen, R. Xing, B. Liu, Toxicity in Takifugu rubripes exposed to acute ammonia: Effects on immune responses, brain neurotransmitter levels, and thyroid endocrine hormones. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2022, 244, 114050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Shimomura, M. Inahata, M. Komori, N. Kagawa, Reduction of Tryptophan Hydroxylase Expression in the Brain of Medaka Fish After Repeated Heat Stress. Zoolog Sci 2019, 36, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Schjolden, K.G. Pulman, T.G. Pottinger, O. Tottmar, S. Winberg, Serotonergic characteristics of rainbow trout divergent in stress responsiveness. Physiol Behav 2006, 87, 938–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. S. Hou, M.Q. Liu, H.S. Wen, Q.F. Gao, Z. Li, X.D. Yang, K.W. Xiang, Q. Yang, X. Hu, M.Z. Qian, J.F. Li, Identification, characterization, and transcription of serotonin receptors in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in response to bacterial infection and salinity changes. Int J Biol Macromol 2023, 249, 125930. [Google Scholar]

- J. Martorell-Ribera, M.T. Venuto, W. Otten, R.M. Brunner, T. Goldammer, A. Rebl, U. Gimsa, Time-Dependent Effects of Acute Handling on the Brain Monoamine System of the Salmonid Coregonus maraena. Front Neurosci 2020, 14, 591738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Shi, E.J. Rupia, P. Jiang, W. Lu, Switch from fight-flight to freeze-hide: The impacts of severe stress and brain serotonin on behavioral adaptations in flatfish. Fish Physiol Biochem 2024, 50, 891–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Shapouri, A. Sharifi, O. Folkedal, T.W.K. Fraser, M.A. Vindas, Behavioral and neurophysiological effects of buspirone in healthy and depression-like state juvenile salmon. Front Behav Neurosci 2024, 18, 1285413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. X. do Carmo Silva, B.G. do Nascimento, G.C.V. Gomes, N.A.H. da Silva, J.S. Pinheiro, S.N. da Silva Chaves, A.F.N. Pimentel, B.P.D. Costa, A.M. Herculano, M. Lima-Maximino, C. Maximino, 5-HT2C agonists and antagonists block different components of behavioral responses to potential, distal, and proximal threat in zebrafish. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2021, 210, 173276. [Google Scholar]

- L. R. Medeiros, M.C. Cartolano, M.D. McDonald, Crowding stress inhibits serotonin 1A receptor-mediated increases in corticotropin-releasing factor mRNA expression and adrenocorticotropin hormone secretion in the Gulf toadfish. J Comp Physiol B 2014, 184, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Z. K. Varga, D. Pejtsik, L. Biro, A. Zsigmond, M. Varga, B. Toth, V. Salamon, T. Annus, E. Mikics, M. Aliczki, Conserved Serotonergic Background of Experience-Dependent Behavioral Responsiveness in Zebrafish (Danio rerio). J Neurosci 2020, 40, 4551–4564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E. Hoglund, M. Moltesen, M.F. Castanheira, P.O. Thornqvist, P.I.M. Silva, O. Overli, C. Martins, S. Winberg, Contrasting neurochemical and behavioral profiles reflects stress coping styles but not stress responsiveness in farmed gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata). Physiol Behav 2020, 214, 112759. [Google Scholar]

- Y. M. Ulrich-Lai, J.P. Herman, Neural regulation of endocrine and autonomic stress responses. Nat Rev Neurosci 2009, 10, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Scott-Solomon, E. Boehm, R. Kuruvilla, The sympathetic nervous system in development and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 2021, 22, 685–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Won, Y.K. Kim, Stress, the Autonomic Nervous System, and the Immune-kynurenine Pathway in the Etiology of Depression. Curr Neuropharmacol 2016, 14, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. S. Kulkarni, N.A. Mischel, P.J. Mueller, Revisiting differential control of sympathetic outflow by the rostral ventrolateral medulla. Front Physiol 2022, 13, 1099513. [Google Scholar]

- J. J. Zhou, J. Pachuau, D.P. Li, S.R. Chen, H.L. Pan, Group III metabotropic glutamate receptors regulate hypothalamic presympathetic neurons through opposing presynaptic and postsynaptic actions in hypertension. Neuropharmacology 2020, 174, 108159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. J. Wang, Q.H. Zeng, W.Z. Wang, W. Wang, GABA(A) and GABA(B) receptor-mediated inhibition of sympathetic outflow in the paraventricular nucleus is blunted in chronic heart failure. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2009, 36, 516–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Perez-Rodriguez, A.M. Olivan, C. Roncero, J. Moron-Oset, M.P. Gonzalez, M.J. Oset-Gasque, Glutamate triggers neurosecretion and apoptosis in bovine chromaffin cells through a mechanism involving NO production by neuronal NO synthase activation. Free Radic Biol Med 2014, 69, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. Inoue, K. Harada, H. Matsuoka, A. Warashina, Paracrine role of GABA in adrenal chromaffin cells. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2010, 30, 1217–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R. L. Brindley, M.B. Bauer, R.D. Blakely, K.P.M. Currie, Serotonin and Serotonin Transporters in the Adrenal Medulla: A Potential Hub for Modulation of the Sympathetic Stress Response. ACS Chem Neurosci 2017, 8, 943–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. B. Bauer, R.L. Brindley, K.P. Currie, Serotonergic regulation of catecholamine exocytosis from adrenal chromaffin cells involves two mechanistically and temporally distinct pathways. Biophysical Journal 2024, 123, 382a. [Google Scholar]

- H. Kalamarz-Kubiak, Cortisol in Correlation to Other Indicators of Fish Welfare, Corticosteroids, IntechOpen, London, UK, 2018, pp. 155-183.

- A. K. Skrzynska, E. Maiorano, M. Bastaroli, F. Naderi, J.M. Miguez, G. Martinez-Rodriguez, J.M. Mancera, J.A. Martos-Sitcha, Impact of Air Exposure on Vasotocinergic and Isotocinergic Systems in Gilthead Sea Bream (Sparus aurata): New Insights on Fish Stress Response. Front Physiol 2018, 9, 96. [Google Scholar]

- E. S. Chelebieva, E.S. Kladchenko, I.V. Mindukshev, S. Gambaryan, A.Y. Andreyeva, ROS formation, mitochondrial potential and osmotic stability of the lamprey red blood cells: effect of adrenergic stimulation and hypoosmotic stress. Fish Physiol Biochem 2024, 50, 1341–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Zhao, K. Jiang, X. Ge, J. Huang, C. Wu, S.X. Chen, Neurotransmitter norepinephrine regulates chromatosomes aggregation and the formation of blotches in coral trout Plectropomus leopardus. Fish Physiol Biochem 2024, 50, 705–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. A. Shaughnessy, V.D. Myhre, D.J. Hall, S.D. McCormick, R.M. Dores, Hypothalamus-pituitary-interrenal (HPI) axis signaling in Atlantic sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus) and sterlet (Acipenser ruthenus). Gen Comp Endocrinol 2023, 339, 114290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Faught, M.J.M. Schaaf, Molecular mechanisms of the stress-induced regulation of the inflammatory response in fish. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2024, 345, 114387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Martinez, R.S. Hattori, J.I. Fernandino, G.M. Somoza, S.D. Hung, Y. Masuda, Y. Yamamoto, C.A. Strussmann, Temperature- and genotype-dependent stress response and activation of the hypothalamus-pituitary-interrenal axis during temperature-induced sex reversal in pejerrey Odontesthes bonariensis, a species with genotypic and environmental sex determination. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2024, 582, 112114. [Google Scholar]

- M. I. Virtanen, M.H. Iversen, D.M. Patel, M.F. Brinchmann, Daily crowding stress has limited, yet detectable effects on skin and head kidney gene expression in surgically tagged atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Fish & shellfish immunology 2024, 152, 109794. [Google Scholar]

- L. M. Whitehouse, E. Faught, M.M. Vijayan, R.G. Manzon, Hypoxia affects the ontogeny of the hypothalamus-pituitary-interrenal axis functioning in the lake whitefish (Coregonus clupeaformis). Gen Comp Endocrinol 2020, 295, 113524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- N. Saiz, M. N. Saiz, M. Gomez-Boronat, N. De Pedro, M.J. Delgado, E. Isorna, The Lack of Light-Dark and Feeding-Fasting Cycles Alters Temporal Events in the Goldfish (Carassius auratus) Stress Axis, Animals (Basel) 11(3) (2021).

- G. Ghaedi, B. Falahatkar, V. Yavari, M.T. Sheibani, G.N. Broujeni, The onset of stress response in rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss embryos subjected to density and handling. Fish Physiol Biochem 2015, 41, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaro, R.E. Olsen, T.S. Kristiansen, L.O. Ebbesson, T.O. Nilsen, G. Flik, M. Gorissen, Stress in Atlantic salmon: response to unpredictable chronic stress. J Exp Biol 2015, 218, 2538–2550. [Google Scholar]

- Z. Arab-Bafrani, E. Zabihi, S.M. Hoseini, H. Sepehri, M. Khalili, Silver nanoparticles modify the hypothalamic-pituitary-interrenal axis and block cortisol response to an acute stress in zebrafish, Danio rerio. Toxicol Ind Health 2022, 38, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. S. Tellis, D. Alsop, C.M. Wood, Effects of copper on the acute cortisol response and associated physiology in rainbow trout. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol 2012, 155, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Q. Zhuo, X. Chen, L. Gao, H.T. Zhang, Q.L. Zhu, J.L. Zheng, Y. Liu, Early life stage exposure to cadmium and zinc within hour affected GH/IGF axis, Nrf2 signaling and HPI axis in unexposed offspring of marine medaka Oryzias melastigma. Aquat Toxicol 2023, 261, 106628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Nesan, M.M. Vijayan, Maternal Cortisol Mediates Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Interrenal Axis Development in Zebrafish. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 22582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. M. Plotsky, E.T. Cunningham, Jr., E.P. Widmaier, Catecholaminergic modulation of corticotropin-releasing factor and adrenocorticotropin secretion. Endocr Rev 1989, 10, 437–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. W. Walker, M.W. Strachan, E.R. Lightly, B.C. Williams, I.M. Bird, Acetylcholine stimulates cortisol secretion through the M3 muscarinic receptor linked to a polyphosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C in bovine adrenal fasciculata/reticularis cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 1990, 72, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y.M. Ulrich-Lai, W.C. Y.M. Ulrich-Lai, W.C. Engeland, Sympatho-adrenal activity and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis regulation, in: T. Steckler, N.H. Kalin, J.M.H.M. Reul (Eds.), Handbook of Stress and the Brain - Part 1: The Neurobiology of Stress, Elsevier2005, pp. 419-435.

- E.B. Ormaechea, M.E. E.B. Ormaechea, M.E. Cornide-Petronio, E. Negrete-Sánchez, C.G.Á. De León, A.I. Álvarez-Mercado, J. Gulfo, M.B. Jiménez Castro, J. Gracia-Sancho, C. Peralta, Effects of Cortisol-Induced Acetylcholine Accumulation on Tissue Damage and Regeneration in Steatotic Livers in the Context of Partial Hepatectomy Under Vascular Occlusion, Transplantation 102 (2018).

- Y. M. Ulrich-Lai, K.R. Jones, D.R. Ziegler, W.E. Cullinan, J.P. Herman, Forebrain origins of glutamatergic innervation to the rat paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus: differential inputs to the anterior versus posterior subregions. J Comp Neurol 2011, 519, 1301–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- N. K. Evanson, J.P. Herman, Role of Paraventricular Nucleus Glutamate Signaling in Regulation of HPA Axis Stress Responses. Interdiscip Inf Sci 2015, 21, 253–260. [Google Scholar]

- Sewanu Stephen Godonu, N. Francis-Lyons, Role Of Cortisol in The Synthesis of Glutamate During Oxidative Stress. Int. J. Sci. R. Tech. 2025, 2, 100–104. [Google Scholar]

- D. Jezova, E. Jurankova, M. Vigas, [Glutamate neurotransmission, stress and hormone secretion]. Bratisl Lek Listy 1995, 96, 588–596.

- J. Maguire, The relationship between GABA and stress: ’it’s complicated’. J Physiol 2018, 596, 1781–1782.

- P. L.W. Colmers, J.S. Bains, Balancing tonic and phasic inhibition in hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone neurons. J Physiol 2018, 596, 1919–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. L. Kaminski, A.G. Watts, Intact catecholamine inputs to the forebrain are required for appropriate regulation of corticotrophin-releasing hormone and vasopressin gene expression by corticosterone in the rat paraventricular nucleus. J Neuroendocrinol 2012, 24, 1517–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. H. Douma, E.R. de Kloet, Stress-induced plasticity and functioning of ventral tegmental dopamine neurons. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2020, 108, 48–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G.D. Stanwood, Dopamine and Stress, in: G. Fink (Ed.), Stress: Physiology, Biochemistry, and Pathology, Academic Press2019, pp. 105-114.

- N. R. Hanley, L.D. Van de Kar, Serotonin and the neuroendocrine regulation of the hypothalamic--pituitary-adrenal axis in health and disease. Vitam Horm 2003, 66, 189–255. [Google Scholar]

- H. Jorgensen, U. Knigge, A. Kjaer, M. Moller, J. Warberg, Serotonergic stimulation of corticotropin-releasing hormone and pro-opiomelanocortin gene expression. J Neuroendocrinol 2002, 14, 788–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. V. Wu, P.Q. Yuan, J. Lai, K. Wong, M.C. Chen, G.V. Ohning, Y. Tache, Activation of Type 1 CRH receptor isoforms induces serotonin release from human carcinoid BON-1N cells: an enterochromaffin cell model. Endocrinology 2011, 152, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- N. C. Donner, P.H. Siebler, D.T. Johnson, M.D. Villarreal, S. Mani, A.J. Matti, C.A. Lowry, Serotonergic systems in the balance: CRHR1 and CRHR2 differentially control stress-induced serotonin synthesis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016, 63, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U. Dahlgren, THE ELECTRIC MOTOR NERVE CENTERS IN THE SKATES (RAJIDAe). Science 1914, 40, 862–863.

- C. Cioni, E. C. Cioni, E. Angiulli, M. Toni, Nitric Oxide and the Neuroendocrine Control of the Osmotic Stress Response in Teleosts, Int J Mol Sci 20(3) (2019).

- M. Yuan, X. Li, W. Lu, The caudal neurosecretory system: A novel thermosensitive tissue and its signal pathway in olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus). J Neuroendocrinol 2020, 32, e12876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. J. Bernier, S.L. Alderman, E.N. Bristow, Heads or tails? Stressor-specific expression of corticotropin-releasing factor and urotensin I in the preoptic area and caudal neurosecretory system of rainbow trout. J Endocrinol 2008, 196, 637–648. [Google Scholar]

- J. P. O’Brien, R.M. Kriebel, Brain stem innervation of the caudal neurosecretory system. Cell Tissue Res 1982, 227, 153–160. [Google Scholar]

- Z. Lan, W. Zhang, J. Xu, M. Zhou, Y. Chen, H. Zou, W. Lu, Modulatory effect of dopamine receptor 5 on the neurosecretory Dahlgren cells of the olive flounder, Paralichthys olivaceus. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2018, 266, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Shi, C. Liu, Y. Qin, L. Yv, W. Lu, alpha1 and beta3 adrenergic receptor-mediated excitatory effects of adrenaline on the caudal neurosecretory system (CNSS) in olive flounder, Paralichthys olivaceus. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2024, 349, 114468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Jiang, S. Fang, N. Huang, W. Lu, The excitatory effect of 5-HT(1A) and 5-HT(2B) receptors on the caudal neurosecretory system Dahlgren cells in olive flounder, Paralichthys olivaceus. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 2023, 283, 111457. [Google Scholar]

- W. Zhang, Z. Lan, K. Li, C. Liu, P. Jiang, W. Lu, Inhibitory role of taurine in the caudal neurosecretory Dahlgren cells of the olive flounder, Paralichthys olivaceus. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2020, 299, 113613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. Lan, J. Xu, Y. Wang, W. Lu, Modulatory effect of glutamate GluR2 receptor on the caudal neurosecretory Dahlgren cells of the olive flounder, Paralichthys olivaceus. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2018, 261, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Z. Lan, W. Zhang, J. Xu, W. Lu, GABA(A) receptor-mediated inhibition of Dahlgren cells electrical activity in the olive flounder, Paralichthys olivaceus. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2021, 306, 113753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. Gozdowska, M. Slebioda, E. Kulczykowska, Neuropeptides isotocin and arginine vasotocin in urophysis of three fish species. Fish Physiol Biochem 2013, 39, 863–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Zhou, C. Ge, A. Chen, W. Lu, Dynamic Expression and Regulation of Urotensin I and Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone Receptors in Ovary of Olive Flounder Paralichthys olivaceus. Front Physiol 2019, 10, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- X. Li, H. Zhou, C. Ge, K. Li, A. Chen, W. Lu, Dynamic changes of urotensin II and its receptor during ovarian development of olive flounder Paralichthys olivaceus. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol 2023, 263, 110782. [Google Scholar]

- W. Lu, Y. Jin, J. Xu, M.P. Greenwood, R.J. Balment, Molecular characterisation and expression of parathyroid hormone-related protein in the caudal neurosecretory system of the euryhaline flounder, Platichthys flesus. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2017, 249, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Lu, L. Dow, S. Gumusgoz, M.J. Brierley, J.M. Warne, C.R. McCrohan, R.J. Balment, D. Riccardi, Coexpression of corticotropin-releasing hormone and urotensin i precursor genes in the caudal neurosecretory system of the euryhaline flounder (Platichthys flesus): a possible shared role in peripheral regulation. Endocrinology 2004, 145, 5786–5797. [Google Scholar]

- W. Lu, M. Greenwood, L. Dow, J. Yuill, J. Worthington, M.J. Brierley, C.R. McCrohan, D. Riccardi, R.J. Balment, Molecular characterization and expression of urotensin II and its receptor in the flounder (Platichthys flesus): a hormone system supporting body fluid homeostasis in euryhaline fish. Endocrinology 2006, 147, 3692–3708. [Google Scholar]

- Y. Qin, M. Shi, Y. Wei, W. Lu, The role of NMDA receptors in fish stress response: Assessments based on physiology of the caudal neurosecretory system and defensive behavior. J Neuroendocrinol 2024, 36, e13448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Yuan, X. Li, T. Long, Y. Chen, W. Lu, Dynamic Responses of the Caudal Neurosecretory System (CNSS) Under Thermal Stress in Olive Flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus). Front Physiol 2019, 10, 1560. [Google Scholar]

- W. Lu, G. Zhu, A. Chen, X. Li, C.R. McCrohan, R. Balment, Gene expression and hormone secretion profile of urotensin I associated with osmotic challenge in caudal neurosecretory system of the euryhaline flounder, Platichthys flesus. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2019, 277, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- C. J. Kelsall, R.J. Balment, Native urotensins influence cortisol secretion and plasma cortisol concentration in the euryhaline flounder, platichthys flesus. Gen Comp Endocrinol 1998, 112, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. E. Arnold-Reed, R.J. Balment, Peptide hormones influence in vitro interrenal secretion of cortisol in the trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss. Gen Comp Endocrinol 1994, 96, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- K. Rousseau, F. Girardot, C. Parmentier, H. Tostivint, The Caudal Neurosecretory System: A Still Enigmatic Second Neuroendocrine Complex in Fish. Neuroendocrinology 2025, 115, 154–194. [Google Scholar]

- M. Herrera, J.M. Mancera, B. Costas, The Use of Dietary Additives in Fish Stress Mitigation: Comparative Endocrine and Physiological Responses. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019, 10, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Herrera, M.A. Herves, I. Giraldez, K. Skar, H. Mogren, A. Mortensen, V. Puvanendran, Effects of amino acid supplementations on metabolic and physiological parameters in Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) under stress. Fish Physiol Biochem 2017, 43, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. M. Hoseini, M. Ahmad Khan, M. Yousefi, B. Costas, Roles of arginine in fish nutrition and health: insights for future researches. Reviews in Aquaculture 2020, 12, 2091–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Salamanca, I. N. Salamanca, I. Giráldez, E. Morales, I. de La Rosa, M. Herrera, Phenylalanine and Tyrosine as Feed Additives for Reducing Stress and Enhancing Welfare in Gilthead Seabream and Meagre, Animals, 2021.

- B. Costas, C. Aragao, J.L. Soengas, J.M. Miguez, P. Rema, J. Dias, A. Afonso, L.E. Conceicao, Effects of dietary amino acids and repeated handling on stress response and brain monoaminergic neurotransmitters in Senegalese sole (Solea senegalensis) juveniles. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 2012, 161, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Salamanca, I. Giráldez, E. Morales, I. de La Rosa, M. Herrera, Phenylalanine and Tyrosine as Feed Additives for Reducing Stress and Enhancing Welfare in Gilthead Seabream and Meagre. Animals-Basel 2021, 11, 45. [Google Scholar]

- N. Salamanca, O. Moreno, I. Giraldez, E. Morales, I. de la Rosa, M. Herrera, Effects of Dietary Phenylalanine and Tyrosine Supplements on the Chronic Stress Response in the Seabream (Sparus aurata). Front Physiol 2021, 12, 775771. [Google Scholar]

- W. Li, L. Feng, Y. Liu, W.D. Jiang, S.Y. Kuang, J. Jiang, S.H. Li, L. Tang, X.Q. Zhou, Effects of dietary phenylalanine on growth, digestive and brush border enzyme activities and antioxidant capacity in the hepatopancreas and intestine of young grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Aquaculture Nutrition 2015, 21, 913–925. [Google Scholar]

- P. Kumar, S. Saurabh, A.K. Pal, N.P. Sahu, A.R. Arasu, Stress mitigating and growth enhancing effect of dietary tryptophan in rohu (Labeo rohita, Hamilton, 1822) fingerlings. Fish Physiol Biochem 2014, 40, 1325–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. M. Hoseini, M. Yousefi, A. Taheri Mirghaed, B.A. Paray, S.H. Hoseinifar, H. Van Doan, Effects of rearing density and dietary tryptophan supplementation on intestinal immune and antioxidant responses in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Aquaculture 2020, 528, 735537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Peixoto, I. Carvalho, M. Machado, C. Aragao, B. Costas, R. Azeredo, Dietary tryptophan intervention counteracts stress-induced transcriptional changes in a teleost fish HPI axis during inflammation. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 7354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, B. Lahlou, J. Botella, J. Porthe-Nibelle, In vivo and in vitro studies on the release of cortisol from interrenal tissue in trout. I. Effects of ACTH and prostaglandins. Exp Biol 1985, 43, 201–212. [Google Scholar]

- J. Niu, L.X. Tian, Y.J. Liu, K.S. Mai, H.J. Yang, C.X. Ye, W. Gao, Nutrient values of dietary ascorbic acid (l-ascorbyl-2-polyphosphate) on growth, survival and stress tolerance of larval shrimp,Litopenaeus vannamei. Aquaculture Nutrition 2009, 15, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Ming, J. Xie, P. Xu, X. Ge, W. Liu, J. Ye, Effects of emodin and vitamin C on growth performance, biochemical parameters and two HSP70s mRNA expression of Wuchang bream (Megalobrama amblycephala Yih) under high temperature stress. Fish & shellfish immunology 2012, 32, 651–661. [Google Scholar]

- B. Liu, P. Xu, J. Xie, X. Ge, S. Xia, C. Song, Q. Zhou, L. Miao, M. Ren, L. Pan, R. Chen, Effects of emodin and vitamin E on the growth and crowding stress of Wuchang bream (Megalobrama amblycephala). Fish & shellfish immunology 2014, 40, 595–602. [Google Scholar]

- M. A.O. Dawood, S. Koshio, Vitamin C supplementation to optimize growth, health and stress resistance in aquatic animals. Reviews in Aquaculture 2016, 10, 334–350. [Google Scholar]

- Ciji, M.S. Akhtar, Stress management in aquaculture: a review of dietary interventions. Reviews in Aquaculture 2021, 13, 2190–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. H. Sherif, M.E. Mahfouz, Immune status of Oreochromis niloticus experimentally infected with Aeromonas hydrophila following feeding with 1, 3 β-glucan and levamisole immunostimulants. Aquaculture 2019, 509, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Meshkini, N. Delirezh, A.A. Tafi, Effects of levamisole on immune responses and resistance against density stress in rainbow trout fingerling (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Journal of Veterinary Research 2017, 72, 129–136. [Google Scholar]

- E. Pahor-Filho, A.S.C. Castillo, N.L. Pereira, F. Pilarski, E.C. Urbinati, Levamisole enhances the innate immune response and prevents increased cortisol levels in stressed pacu (Piaractus mesopotamicus). Fish & shellfish immunology 2017, 65, 96–102. [Google Scholar]

- L. Jiang, I. Dasgupta, J.A. Hurcombe, H.F. Colyer, P.W. Mathieson, G.I. Welsh, Levamisole in steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome: usefulness in adult patients and laboratory insights into mechanisms of action via direct action on the kidney podocyte. Clin Sci (Lond) 2015, 128, 883–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Shukry, T. Kamal, R. Ali, F. Farrag, E. Almadaly, A.A. Saleh, M. Abu El-Magd, Pinacidil and levamisole prevent glutamate-induced death of hippocampal neuronal cells through reducing ROS production. Neurol Res 2015, 37, 916–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. A.O. Dawood, N.M. Eweedah, E.M. Moustafa, E.M. Farahat, Probiotic effects of Aspergillus oryzae on the oxidative status, heat shock protein, and immune related gene expression of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) under hypoxia challenge. Aquaculture 2020, 520, 734669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudzik, A. Orzylowska, R. Rola, G.J. Stanisz, Probiotics, Prebiotics and Postbiotics on Mitigation of Depression Symptoms: Modulation of the Brain-Gut-Microbiome Axis. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. C. Gomes, R.P. Brinn, J.L. Marcon, L.A. Dantas, F.R. Brandão, J.S. de Abreu, P.E.M. Lemos, D.M. McComb, B. Baldisserotto, Benefits of using the probiotic Efinol®L during transportation of cardinal tetra,Paracheirodon axelrodi(Schultz), in the Amazon. Aquaculture Research 2009, 40, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Eissa, H.P. Wang, H. Yao, E. Abou-ElGheit, Mixed Bacillus Species Enhance the Innate Immune Response and Stress Tolerance in Yellow Perch Subjected to Hypoxia and Air-Exposure Stress. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 6891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Xie, B. Liu, Q. Zhou, Y. Su, Y. He, L. Pan, X. Ge, P. Xu, Effects of anthraquinone extract from rhubarb Rheum officinale Bail on the crowding stress response and growth of common carp Cyprinus carpio var. Jian. Aquaculture 2008, 281, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Song, B. Liu, J. Xie, X. Ge, Z. Zhao, Y. Zhang, H. Zhang, M. Ren, Q. Zhou, L. Miao, P. Xu, Y. Lin, Comparative proteomic analysis of liver antioxidant mechanisms in Megalobrama amblycephala stimulated with dietary emodin. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 40356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D. A. Tadese, C. Song, C. Sun, B. Liu, B. Liu, Q. Zhou, P. Xu, X. Ge, M. Liu, X. Xu, M. Tamiru, Z. Zhou, A. Lakew, N.T. Kevin, The role of currently used medicinal plants in aquaculture and their action mechanisms: A review. Reviews in Aquaculture 2021, 14, 816–847. [Google Scholar]

- S. M. Hoseini, S.K. Gupta, M. Yousefi, E.V. Kulikov, S.G. Drukovsky, A.K. Petrov, A. Taheri Mirghaed, S.H. Hoseinifar, H. Van Doan, Mitigation of transportation stress in common carp, Cyprinus carpio, by dietary administration of turmeric. Aquaculture 2022, 546, 737380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C.-H. Chang, Y.-C. C.-H. Chang, Y.-C. Wang, T.-H. Lee, Hypothermal stress-induced salinity-dependent oxidative stress and apoptosis in the livers of euryhaline milkfish, Chanos chanos, Aquaculture 534 (2021).

- C. Hassenruck, H. C. Hassenruck, H. Reinwald, A. Kunzmann, I. Tiedemann, A. Gardes, Effects of Thermal Stress on the Gut Microbiome of Juvenile Milkfish (Chanos chanos), Microorganisms 9(1) (2020).

- Topal, S. Ozdemir, H. Arslan, S. Comakli, How does elevated water temperature affect fish brain? (A neurophysiological and experimental study: Assessment of brain derived neurotrophic factor, cFOS, apoptotic genes, heat shock genes, ER-stress genes and oxidative stress genes). Fish & shellfish immunology 2021, 115, 198–204. [Google Scholar]

- X. Li, P. X. Li, P. Wei, S. Liu, Y. Tian, H. Ma, Y. Liu, Photoperiods affect growth, food intake and physiological metabolism of juvenile European Sea Bass (Dicentrachus labrax L.). Aquacult Rep 20 (2021).

- P. Konkal, C.B. Ganesh, Continuous Exposure to Light Suppresses the Testicular Activity in Mozambique Tilapia Oreochromis mossambicus (Cichlidae). J Ichthyol+ 2020, 60, 660–667.

- S. Suzuki, E. S. Suzuki, E. Takahashi, T.O. Nilsen, N. Kaneko, H. Urabe, Y. Ugachi, E. Yamaha, M. Shimizu, Physiological changes in off-season smolts induced by photoperiod manipulation in masu salmon (Oncorhynchus masou), Aquaculture 526 (2020).

- Y. P. Sapozhnikova, A.G. Koroleva, V.M. Yakhnenko, M.L. Tyagun, O.Y. Glyzina, A.B. Coffin, M.M. Makarov, A.N. Shagun, V.A. Kulikov, P.V. Gasarov, S.V. Kirilchik, I.V. Klimenkov, N.P. Sudakov, P.N. Anoshko, N.A. Kurashova, L.V. Sukhanova, Molecular and cellular responses to long-term sound exposure in peled (Coregonus peled). J Acoust Soc Am 2020, 148, 895. [Google Scholar]

- H. Kusku, S. Ergun, S. Yilmaz, B. Guroy, M. Yigit, Impacts of Urban Noise and Musical Stimuli on Growth Performance and Feed Utilization of Koi fish (Cyprinus carpio) in Recirculating Water Conditions. Turk J Fish Aquat Sc 2019, 19, 513–523. [Google Scholar]

- H. Kusku, Ü. Yigit, S. Yilmaz, M. Yigit, S. Ergün, Acoustic effects of underwater drilling and piling noise on growth and physiological response of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquaculture Research 2020, 51, 3166–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. Falahatkar, A.S. Amlashi, M. Kabir, Ventilation frequency in juvenile beluga sturgeon Huso huso L. exposed to clay turbidity. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 2019, 513, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. C.T. Phan, A.V. Manuel, N. Tsutsui, T. Yoshimatsu, Impacts of short-term salinity and turbidity stress on the embryonic stage of red sea bream Pagrus major. Fisheries Sci 2019, 86, 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- M. Hasenbein, N.A. Fangue, J. Geist, L.M. Komoroske, J. Truong, R. McPherson, R.E. Connon, Assessments at multiple levels of biological organization allow for an integrative determination of physiological tolerances to turbidity in an endangered fish species. Conserv Physiol 2016, 4, cow004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. D.D. Carneiro, L.C. Maltez, R.V. Rodrigues, M. Planas, L.A. Sampaio, Does acidification lead to impairments on oxidative status and survival of orange clownfish Amphiprion percula juveniles?. Fish Physiol Biochem 2021, 47, 841–848.

- M. D.D. Carneiro, S. Garcia-Mesa, L.A. Sampaio, M. Planas, Primary, secondary, and tertiary stress responses of juvenile seahorse Hippocampus reidi exposed to acute acid stress in brackish and seawater. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol 2021, 255, 110592. [Google Scholar]

- L. Pellegrin, L.F. L. Pellegrin, L.F. Nitz, L.C. Maltez, C.E. Copatti, L. Garcia, Alkaline water improves the growth and antioxidant responses of pacu juveniles (Piaractus mesopotamicus), Aquaculture 519 (2020).

- Bal, S.G. Pati, F. Panda, L. Mohanty, B. Paital, Low salinity induced challenges in the hardy fish Heteropneustes fossilis; future prospective of aquaculture in near coastal zones, Aquaculture 543 (2021).

- M. A.O. Dawood, A.E. Noreldin, H. Sewilam, Long term salinity disrupts the hepatic function, intestinal health, and gills antioxidative status in Nile tilapia stressed with hypoxia. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2021, 220, 112412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N.A. Mohamed, M.F. N.A. Mohamed, M.F. Saad, M. Shukry, A.M.S. El-Keredy, O. Nasif, H. Van Doan, M.A.O. Dawood, Physiological and ion changes of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) under the effect of salinity stress, Aquacult Rep 19 (2021).

- J. Zeng, N.A. Herbert, W. Lu, Differential Coping Strategies in Response to Salinity Challenge in Olive Flounder. Front Physiol 2019, 10, 1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J.-s. Huang, Z.-x. J.-s. Huang, Z.-x. Guo, J.-d. Zhang, W.-z. Wang, Z.-l. Wang, E. Amenyogbe, G. Chen, Effects of hypoxia-reoxygenation conditions on serum chemistry indicators and gill and liver tissues of cobia (Rachycentron canadum), Aquacult Rep 20 (2021).

- N. Schafer, J. N. Schafer, J. Matousek, A. Rebl, V. Stejskal, R.M. Brunner, T. Goldammer, M. Verleih, T. Korytar, Effects of Chronic Hypoxia on the Immune Status of Pikeperch (Sander lucioperca Linnaeus, 1758), Biology (Basel) 10(7) (2021).

- X. Zheng, D. X. Zheng, D. Fu, J. Cheng, R. Tang, M. Chu, P. Chu, T. Wang, S. Yin, Effects of hypoxic stress and recovery on oxidative stress, apoptosis, and intestinal microorganisms in Pelteobagrus vachelli, Aquaculture 543 (2021).

- H. Su, D. Ma, H. Zhu, Z. Liu, F. Gao, Transcriptomic response to three osmotic stresses in gills of hybrid tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus female x O. urolepis hornorum male). Bmc Genomics 2020, 21, 110. [Google Scholar]

- Y. Zhao, C. Zhang, H. Zhou, L. Song, J. Wang, J. Zhao, Transcriptome changes for Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) in response to alkalinity stress. Comp Biochem Physiol Part D Genomics Proteomics 2020, 33, 100651. [Google Scholar]

- N. M. Noor, M. De, Z.C. Cob, S.K. Das, Welfare of scaleless fish, Sagor catfish ( Hexanematichthys sagor) juveniles under different carbon dioxide concentrations. Aquaculture Research 2021, 52, 2980–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V.C. Mota, T.O. V.C. Mota, T.O. Nilsen, J. Gerwins, M. Gallo, J. Kolarevic, A. Krasnov, B.F. Terjesen, Molecular and physiological responses to long-term carbon dioxide exposure in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar), Aquaculture 519 (2020).

- M. Machado, F. Arenas, J.C. Svendsen, R. Azeredo, L.J. Pfeifer, J.M. Wilson, B. Costas, Effects of Water Acidification on Senegalese Sole Solea senegalensis Health Status and Metabolic Rate: Implications for Immune Responses and Energy Use. Front Physiol 2020, 11, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, X.-F. Y. Zhang, X.-F. Liang, S. He, L. Li, Effects of long-term low-concentration nitrite exposure and detoxification on growth performance, antioxidant capacities, and immune responses in Chinese perch (Siniperca chuatsi), Aquaculture 533 (2021).

- J. Yu, Y. Xiao, Y. Wang, S. Xu, L. Zhou, J. Li, X. Li, Chronic nitrate exposure cause alteration of blood physiological parameters, redox status and apoptosis of juvenile turbot (Scophthalmus maximus). Environ Pollut 2021, 283, 117103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- X. Q. Gao, F. Fei, H.H. Huo, B. Huang, X.S. Meng, T. Zhang, B.L. Liu, Impact of nitrite exposure on plasma biochemical parameters and immune-related responses in Takifugu rubripes. Aquat Toxicol 2020, 218, 105362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Xue, J. Lin, Y. Han, Y. Han, Ammonia stress–induced apoptosis by p53–BAX/BCL-2 signal pathway in hepatopancreas of common carp (Cyprinus carpio). Aquacult Int 2021, 29, 1895–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Xue, J. S. Xue, J. Lin, Q. Zhou, H. Wang, Y. Han, Effect of ammonia stress on transcriptome and endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway for common carp (Cyprinus carpio) hepatopancreas, Aquacult Rep 20 (2021).

- S. Cao, D. S. Cao, D. Zhao, R. Huang, Y. Xiao, W. Xu, X. Liu, Y. Gui, S. Li, J. Xu, J. Tang, F. Qu, Z. Liu, S. Liu, The influence of acute ammonia stress on intestinal oxidative stress, histology, digestive enzymatic activities and PepT1 activity of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella), Aquacult Rep 20 (2021).

- M. C.B. Kiemer, K.D. Black, D. Lussot, A.M. Bullock, I. Ezzi, The effects of chronic and acute exposure to hydrogen sulphide on Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.). Aquaculture 1995, 135, 311–327.

- T. Bagarinao, I. Lantin-Olaguer, The sulfide tolerance of milkfish and tilapia in relation to fish kills in farms and natural waters in the Philippines, Hydrobiologia 1998, 382, 137–150.

- V. Valenzuela-Muñoz, D. V. Valenzuela-Muñoz, D. Valenzuela-Miranda, A.T. Gonçalves, B. Novoa, A. Figueras, C. Gallardo-Escárate, Induced-iron overdose modulate the immune response in Atlantic salmon increasing the susceptibility to Piscirickettsia salmonis infection, Aquaculture 521 (2020).

- M. Singh, A.S. Barman, A.L. Devi, A.G. Devi, P.K. Pandey, Iron mediated hematological, oxidative and histological alterations in freshwater fish Labeo rohita. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2019, 170, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Asif, M. Javed, S. Abbas, F. Ambreen, S. Iqbal, Growth responses of carnivorous fish species under the chronic stress of water-borne copper. Iran J Fish Sci 2021, 20, 773–788. [Google Scholar]

- J. S. Paul, B.C. Small, Chronic exposure to environmental cadmium affects growth and survival, cellular stress, and glucose metabolism in juvenile channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus). Aquat Toxicol 2021, 230, 105705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakade, E.S. Salama, F. Pengya, P. Liu, X. Li, Long-term exposure of high concentration heavy metals induced toxicity, fatality, and gut microbial dysbiosis in common carp, Cyprinus carpio. Environ Pollut 2020, 266, 115293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Kong, M. Li, X. Shan, G. Wang, G. Han, Effects of deltamethrin subacute exposure in snakehead fish, Channa argus: Biochemicals, antioxidants and immune responses. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2021, 209, 111821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Zhao, G. Tang, C. Xiong, S. Han, C. Yang, K. He, Q. Liu, J. Luo, W. Luo, Y. Wang, Z. Li, S. Yang, Chronic chlorpyrifos exposure induces oxidative stress, apoptosis and immune dysfunction in largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Environ Pollut 2021, 282, 117010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. D. Baldissera, C.F. Souza, R. Zanella, O.D. Prestes, A.D. Meinhart, A.S. Da Silva, B. Baldisserotto, Behavioral impairment and neurotoxic responses of silver catfish Rhamdia quelen exposed to organophosphate pesticide trichlorfon: Protective effects of diet containing rutin. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol 2021, 239, 108871. [Google Scholar]

- P. V. Zimba, L. Khoo, P.S. Gaunt, S. Brittain, W.W. Carmichael, Confirmation of catfish, Ictalurus punctatus (Rafinesque), mortality from Microcystis toxins. J Fish Dis 2008, 24, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- M. J. Bakke, T.E. Horsberg, Effects of algal-produced neurotoxins on metabolic activity in telencephalon, optic tectum and cerebellum of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Aquat Toxicol 2007, 85, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. A.O. Dawood, E.M. Moustafa, M.S. Gewaily, S.E. Abdo, M.F. AbdEl-Kader, M.S. SaadAllah, A.H. Hamouda, Ameliorative effects of Lactobacillus plantarum L-137 on Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) exposed to deltamethrin toxicity in rearing water. Aquat Toxicol 2020, 219, 105377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- X. Chen, H. X. Chen, H. Yi, S. Liu, Y. Zhang, Y. Su, X. Liu, S. Bi, H. Lai, Z. Zeng, G. Li, Promotion of pellet-feed feeding in mandarin fish (Siniperca chuatsi) by Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus is influenced by immune and intestinal flora, Aquaculture 542 (2021).

- A. I. Zaineldin, S. Hegazi, S. Koshio, M. Ishikawa, M.A.O. Dawood, S. Dossou, Z. Yukun, K. Mzengereza, Singular effects of Bacillus subtilis C-3102 or Saccharomyces cerevisiae type 1 on the growth, gut morphology, immunity, and stress resistance of red sea bream (Pagrus major). Ann Anim Sci 2021, 21, 589–608. [Google Scholar]

- L. Kolek, J. L. Kolek, J. Szczygieł, Ł. Napora-Rutkowski, I. Irnazarow, Effect of Trypanoplasma borreli infection on sperm quality and reproductive success of common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.) males, Aquaculture 539 (2021).

- X. Xie, J. Kong, J. Huang, L. Zhou, Y. Jiang, R. Miao, F. Yin, Integration of metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses to characterize the influence of the gill metabolism of Nibea albiflora on the response to Cryptocaryon irritans infection. Vet Parasitol 2021, 298, 109533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M.P. Gonzalez, S.L. M.P. Gonzalez, S.L. Marin, M. Mancilla, H. Canon-Jones, L. Vargas-Chacoff, Fin Erosion of Salmo salar (Linnaeus 1758) Infested with the Parasite Caligus rogercresseyi (Boxshall & Bravo 2000), Animals (Basel) 10(7) (2020).

- K. Filipsson, E. Bergman, L. Greenberg, M. Osterling, J. Watz, A. Erlandsson, Temperature and predator-mediated regulation of plasma cortisol and brain gene expression in juvenile brown trout (Salmo trutta). Front Zool 2020, 17, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Kortet, M.V.M. Laakkonen, J. Tikkanen, A. Vainikka, H. Hirvonen, Size-dependent stress response in juvenile Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus) under prolonged predator conditioning. Aquaculture Research 2019, 50, 1482–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Ling, S.J. Fu, L.Q. Zeng, Predator stress decreases standard metabolic rate and growth in juvenile crucian carp under changing food availability. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 2019, 231, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. N. Barreto, C.N.P. Boscolo, E. Gonçalves-de-Freitas, Homogeneously sized groups increase aggressive interaction and affect social stress in Thai strain Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Mar Freshw Behav Phy 2015, 48, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. M. Gomez-Laplaza, E. Morgan, The influence of social rank in the angelfish, Pterophyllum scalare, on locomotor and feeding activities in a novel environment. Lab Anim 2003, 37, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. A. Sloman, K.M. Gilmour, A.C. Taylor, N.B. Metcalfe, Physiological effects of dominance hierarchies within groups of brown trout, Salmo trutta, held under simulated natural conditions. Fish Physiology and Biochemistry 2000, 22, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhang, Y. Z. Zhang, Y. Fu, H. Guo, X. Zhang, Effect of environmental enrichment on the stress response of juvenile black rockfish Sebastes schlegelii, Aquaculture 533 (2021).

- Z. Zhang, Y. Z. Zhang, Y. Fu, Z. Zhang, X. Zhang, S. Chen, A Comparative Study on Two Territorial Fishes: The Influence of Physical Enrichment on Aggressive Behavior, Animals (Basel) 11(7) (2021).

- Z. Zhang, X. Z. Zhang, X. Xu, Y. Wang, X. Zhang, Effects of environmental enrichment on growth performance, aggressive behavior and stress-induced changes in cortisol release and neurogenesis of black rockfish Sebastes schlegelii, Aquaculture 528 (2020).

- L. Li, Y. L. Li, Y. Shen, W. Yang, X. Xu, J. Li, Effect of different stocking densities on fish growth performance: A meta-analysis, Aquaculture 544 (2021).

- C. Poltronieri, R. Laura, D. Bertotto, E. Negrato, C. Simontacchi, M.C. Guerrera, G. Radaelli, Effects of exposure to overcrowding on rodlet cells of the teleost fish Dicentrarchus labrax (L.). Vet Res Commun 2009, 33, 619–629.

- C. M.A. Caipang, M.F. Brinchmann, I. Berg, M. Iversen, R. Eliassen, V. Kiron, Changes in selected stress and immune-related genes in Atlantic cod,Gadus morhua, following overcrowding. Aquaculture Research 2008, 39, 1533–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M.D. Baldissera, C. M.D. Baldissera, C. de Freitas Souza, A.L. Val, B. Baldisserotto, Involvement of purinergic signaling in the Amazon fish Pterygoplichthys pardalis subjected to handling stress: Relationship with immune response, Aquaculture 514 (2020).

- P. Sun, F. Yin, B. Tang, Effects of Acute Handling Stress on Expression of Growth-Related Genes in Pampus argenteus. J World Aquacult Soc 2016, 48, 166–179. [Google Scholar]

- J. Zhao, Y. Zhu, D. Yang, J. Chen, Y. He, X. Li, X. Feng, B. Xiong, Cage-cultured Largemouth Bronze Gudgeon, Coreius guichenoti: Biochemical Profile of Plasma and Physiological Response to Acute Handling Stress. J World Aquacult Soc 2013, 44, 628–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Raposo de Magalhães, D. C. Raposo de Magalhães, D. Schrama, C. Nakharuthai, S. Boonanuntanasarn, D. Revets, S. Planchon, A. Kuehn, M. Cerqueira, R. Carrilho, A.P. Farinha, P.M. Rodrigues, Metabolic Plasticity of Gilthead Seabream Under Different Stressors: Analysis of the Stress Responsive Hepatic Proteome and Gene Expression, Front Mar Sci 8 (2021).

- K. Takahashi, R. Masuda, Net-chasing training improves the behavioral characteristics of hatchery-reared red sea bream (Pagrus major) juveniles. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 2018, 75, 861–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegelbecker, K.M. Sefc, Growth, body condition and contest performance after early-life food restriction in a long-lived tropical fish. Ecol Evol 2021, 11, 10904–10916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Su, S. Luo, N. Qiu, X. Xiong, J. Wang, The Reproductive Strategy of the Rare Minnow (Gobiocypris rarus) in Response to Starvation Stress. Zool Stud 2020, 59, e1. [Google Scholar]

- M. Varju-Katona, T. Muller, Z. Bokor, K. Balogh, M. Mezes, Effects of various lengths of starvation on body parameters and meat composition in intensively reared pikeperch (Sander lucioperca L.). Iran J Fish Sci 2020, 19, 2062–2076.

- M. Bortoletti, L. M. Bortoletti, L. Maccatrozzo, G. Radaelli, S. Caberlotto, D. Bertotto, Muscle Cortisol Levels, Expression of Glucocorticoid Receptor and Oxidative Stress Markers in the Teleost Fish Argyrosomus regius Exposed to Transport Stress, Animals (Basel) 11(4) (2021).

- M. Vanderzwalmen, J. M. Vanderzwalmen, J. McNeill, D. Delieuvin, S. Senes, D. Sanchez-Lacalle, C. Mullen, I. McLellan, P. Carey, D. Snellgrove, A. Foggo, M.E. Alexander, F.L. Henriquez, K.A. Sloman, Monitoring water quality changes and ornamental fish behaviour during commercial transport, Aquaculture 531 (2021).

- E. E. Grausgruber, M.J. Weber, Effects of Stocking Transport Duration on Age-0 Walleye. J Fish Wildl Manag 2021, 12, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of stressors | Examples | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Physical | Water temperature; Photoperiod; Sound; Turbidity … |

[179,180,181] [182,183,184] [185,186,187] [188,189,190] |

| Chemical | pH; Salinity; Dissolved Oxygen; Alkalinity; Carbon dioxide complexities; Nitrite; Ammonia; Hydrogen sulfide; Iron; Heavy metal; Pesticides … |

[191,192,193] [194,195,196,197] [198,199,200] [201,202] [203,204,205] [206,207,208] [209,210,211] [212,213] [214,215] [216,217,218] [219,220,221] |

| Biological | Algal toxicosis; Microorganisms; Parasites; Predators; Social rank; Environmental enrichment … |

[222,223] [224,225,226] [227,228,229] [230,231,232] [233,234,235] [236,237,238] |

| Procedural | Overcrowding; Handling; Netting Feeding; Transportation … |

[239,240,241] [242,243,244] [245,246] [247,248,249] [250,251,252] |

| System | Primary Components | Response Timing | Magnitude/Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brain-Sympathetic-Chromaffin Cells (BSC) Axis | Brain (sympathetic neurons); Sympathetic nerves; Chromaffin cells (in head kidney; catecholamines) |

Immediate (<1 min to hours) | Rapid onset; Short duration (minutes to hours); High peak magnitude |

| Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Interrenal (HPI) Axis | Hypothalamus (CRH/ACTH-releasing factors); Pituitary (ACTH); Interrenal tissue (cortisol/corticosterone) |

Delayed (hours to days) | Slower onset; Long-lasting (days to weeks); Moderate to high magnitude (sustained) |

| Caudal Neurosecretory System (CNSS) | Dahlgren cell (urotensins, isotocin, CRH); Urophysis; |

Variable (minutes to hours, depending on stimulus) | Moderate onset; Moderate duration (hours); Target-specific magnitude |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).