Submitted:

25 May 2025

Posted:

26 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Subjects | Side | Anatomic regions | MNI Coordinates | T-score | Cluster size (# of voxel) | ||

| x | y | z | |||||

| SBJ1 | L | Inferior frontal gyrus | -30 | 28 | -7 | 3.84 | 170 |

| L | Middle frontal gyrus | -38 | 40 | -9 | 4.89 | 154 | |

| L | BA 47 | -33 | 31 | -6 | 3.28 | 53 | |

| L | Insula | -34 | 11 | -3 | 3.17 | 23 | |

| L | Putamen | -23 | -3 | -1 | 3.93 | 22 | |

| L | Lateral globus pallidus | -19 | -3 | -6 | 3.52 | 13 | |

| L | Insula | -41 | -1 | 1 | 3.35 | 10 | |

| SBJ2 | L | Insula/BA 13 | -34 | 13 | -9 | 3.27 | 67 |

| L | Temporal pole | -46 | 8 | -8 | 3.32 | 50 | |

| L | Superior temporal gyrus | -43 | 13 | -9 | 3.32 | 45 | |

| SBJ3 | L | Midbrain | -1 | -31 | -15 | 4.44 | 340 |

| L | Insula (middle) | -39 | -1 | -2 | 3.32 | 34 | |

| R | Insula (middle-inferior) | 39 | -12 | -3 | 2.73 | 47 | |

| L | Parahippocampal gyrus | -15 | -40 | -5 | 3.06 | 212 | |

| R | Putamen | 27 | -17 | 1 | 2.72 | 56 | |

| L | Putamen | -28 | -15 | -2 | 2.76 | 57 | |

| R | Globus pallidus | 22 | -17 | 1 | 2.7 | 67 | |

| R | Supramarginal gyrus | 37 | -48 | 29 | 3.31 | 33 | |

| R | Post-central gyrus | 53 | -17 | 28 | 2.92 | 26 | |

| SBJ4 | L | Superior temporal gyrus * | -47 | -11 | -1 | 3.47 | 27 |

| L | Insula (middle-inferior) * | -35 | -4 | -7 | 2.36 | 20 | |

| R | Inferior frontal gyrus | -43 | 20 | -15 | 2.90 | 534 | |

| R | BA 41 | 47 | -36 | 13 | 2.95 | 86 | |

| L | Superior temporal gyrus | -38 | -40 | 5 | 3.02 | 358 | |

| R | Insula (pI) | 39 | -25 | 4 | 2.18 | 131 | |

| L | Insula (pI) | -36 | -18 | 6 | 1.88 | 134 | |

| L | Insula (aI) | -34 | 11 | -14 | 2.56 | 189 | |

| R | Globus pallidus | 25 | -12 | 1 | 1.91 | 81 | |

| SBJ6 | L | Insula (pI) | -43 | -25 | 16 | 3.22 | 54 |

| R | Posterior cingulate | 5 | -51 | 23 | 4.57 | 173 | |

| L | Superior temporal gyrus | -37 | -45 | 15 | 2.81 | 24 | |

References

- Kurth, F.; Zilles, K.; Fox, P.T.; Laird, A.R.; Eickhoff, S.B. , A link between the systems: functional differentiation and integration within the human insula revealed by meta-analysis. Brain Struct Funct 2010, 214, 519–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ture, U.; Yasargil, D.C.; Al-Mefty, O.; Yasargil, M.G. , Topographic anatomy of the insular region. J Neurosurg 1999, 90, 720–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avery, J.A.; Kerr, K.L.; Ingeholm, J.E.; Burrows, K.; Bodurka, J.; Simmons, W.K. , A common gustatory and interoceptive representation in the human mid-insula. Hum Brain Mapp 2015, 36, 2996–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, A. , How do you feel—now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nature reviews neuroscience 2009, 10, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, A.D. , Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2003, 13, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, A.D. , Emotional moments across time: a possible neural basis for time perception in the anterior insula. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2009, 364, 1933–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogolla, N. , The insular cortex. Curr Biol 2017, 27, R580–R586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, L.Q.; Nomi, J.S.; Hebert-Seropian, B.; Ghaziri, J.; Boucher, O. , Structure and Function of the Human Insula. J Clin Neurophysiol 2017, 34, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaziri, J.; Tucholka, A.; Girard, G.; Houde, J.C.; Boucher, O.; Gilbert, G.; Descoteaux, M.; Lippe, S.; Rainville, P.; Nguyen, D.K. , The Corticocortical Structural Connectivity of the Human Insula. Cereb Cortex 2017, 27, 1216–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, S.; Kullmann, S.; Veit, R. , Food related processes in the insular cortex. Front Hum Neurosci 2013, 7, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, W.K.; DeVille, D.C. , Interoceptive contributions to healthy eating and obesity. Curr Opin Psychol 2017, 17, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, S.; Lee, S.; Preissl, H.; Schultes, B.; Birbaumer, N.; Veit, R. , The obese brain athlete: self-regulation of the anterior insula in adiposity. PLoS One 2012, 7, e42570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Garcia, I.; Jurado, M.A.; Garolera, M.; Segura, B.; Sala-Llonch, R.; Marques-Iturria, I.; Pueyo, R.; Sender-Palacios, M.J.; Vernet-Vernet, M.; Narberhaus, A.; Ariza, M.; Junque, C. , Alterations of the salience network in obesity: a resting-state fMRI study. Hum Brain Mapp 2013, 34, 2786–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makaronidis, J.M.; Batterham, R.L. , Obesity, body weight regulation and the brain: insights from fMRI. Br J Radiol 2018, 91, 20170910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzola, L.; Mauguiere, F.; Isnard, J. , Electrical Stimulations of the Human Insula: Their Contribution to the Ictal Semiology of Insular Seizures. J Clin Neurophysiol 2017, 34, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugnaghi, M.; Meletti, S.; Castana, L.; Francione, S.; Nobili, L.; Mai, R.; Tassi, L. , Features of somatosensory manifestations induced by intracranial electrical stimulations of the human insula. Clin Neurophysiol 2011, 122, 2049–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephani, C.; Fernandez-Baca Vaca, G.; Maciunas, R.; Koubeissi, M.; Luders, H.O. , Functional neuroanatomy of the insular lobe. Brain Struct Funct 2011, 216, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geuter, S.; Boll, S.; Eippert, F.; Buchel, C. , Functional dissociation of stimulus intensity encoding and predictive coding of pain in the insula. Elife 2017, 6, e24770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.; White, N.S.; Kwong, K.K.; Vangel, M.G.; Rosman, I.S.; Gracely, R.H.; Gollub, R.L. , Using fMRI to dissociate sensory encoding from cognitive evaluation of heat pain intensity. Hum Brain Mapp 2006, 27, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Yang, T.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, M.; Meng, F.; Fu, H.; Xie, Y.; Xu, H. , Insular cortex is critical for the perception, modulation, and chronification of pain. J Neuroscience bulletin 2016, 32, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzola, L.; Faillenot, I.; Barral, F.G.; Mauguiere, F.; Peyron, R. , Spatial segregation of somato-sensory and pain activations in the human operculo-insular cortex. Neuroimage 2012, 60, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moayedi, M.; Weissman-Fogel, I. , Is the insula the "how much" intensity coder? J Neurophysiol 2009, 102, 1345–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oshiro, Y.; Quevedo, A.S.; McHaffie, J.G.; Kraft, R.A.; Coghill, R.C. , Brain mechanisms supporting discrimination of sensory features of pain: a new model. J Neurosci 2009, 29, 14924–14931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.; Piche, M.; Chen, J.I.; Peretz, I.; Rainville, P. , Cerebral and spinal modulation of pain by emotions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 20900–20905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, E.; Stankewitz, A.; Witkovsky, V.; Winkler, A.M.; Tracey, I. , Strategy-dependent modulation of cortical pain circuits for the attenuation of pain. Cortex 2019, 113, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, T.; Seymour, B.; O'Doherty, J.; Kaube, H.; Dolan, R.J.; Frith, C.D. , Empathy for pain involves the affective but not sensory components of pain. Science 2004, 303, 1157–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starr, C.J.; Sawaki, L.; Wittenberg, G.F.; Burdette, J.H.; Oshiro, Y.; Quevedo, A.S.; Coghill, R.C. , Roles of the insular cortex in the modulation of pain: insights from brain lesions. J Neurosci 2009, 29, 2684–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apkarian, A.V.; Bushnell, M.C.; Treede, R.D.; Zubieta, J.K. , Human brain mechanisms of pain perception and regulation in health and disease. Eur J Pain 2005, 9, 463–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baliki, M.N.; Geha, P.Y.; Jabakhanji, R.; Harden, N.; Schnitzer, T.J.; Apkarian, A.V. , A preliminary fMRI study of analgesic treatment in chronic back pain and knee osteoarthritis. Mol Pain 2008, 4, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauda, F.; Palermo, S.; Costa, T.; Torta, R.; Duca, S.; Vercelli, U.; Geminiani, G.; Torta, D.M. , Gray matter alterations in chronic pain: A network-oriented meta-analytic approach. Neuroimage Clin 2014, 4, 676–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandloi, S.; Syed, M.; Shoraka, O.; Ailes, I.; Kang, K.C.; Sathe, A.; Heller, J.; Thalheimer, S.; Mohamed, F.B.; Sharan, A.; Harrop, J.; Krisa, L.; Matias, C.; Alizadeh, M. , The role of the insula in chronic pain following spinal cord injury: A resting-state fMRI study. J Neuroimaging 2023, 33, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labrakakis, C. , The Role of the Insular Cortex in Pain. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 5736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frot, M.; Magnin, M.; Mauguiere, F.; Garcia-Larrea, L. , Human SII and posterior insula differently encode thermal laser stimuli. Cereb Cortex 2007, 17, 610–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frot, M.; Mauguiere, F. , Dual representation of pain in the operculo-insular cortex in humans. Brain 2003, 126 Pt 2, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, D.J.; Marouf, R.; Rainville, P.; Bouthillier, A.; Nguyen, D.K. , Effects of insular stimulation on thermal nociception. Eur J Pain 2016, 20, 800–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, D.; Obaid, S.; Fournier-Gosselin, M.P.; Bouthillier, A.; Nguyen, D.K. , Deep Brain Stimulation of the Posterior Insula in Chronic Pain: A Theoretical Framework. Brain Sci 2021, 11, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, S.; Hallett, M.; Rossini, P.M.; Pascual-Leone, A.; Safety of, T.M.S.C.G. , Safety, ethical considerations, and application guidelines for the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation in clinical practice and research. Clin Neurophysiol 2009, 120, 2008–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaster, T.S.; Daskalakis, Z.J.; Noda, Y.; Knyahnytska, Y.; Downar, J.; Rajji, T.K.; Levkovitz, Y.; Zangen, A.; Butters, M.A.; Mulsant, B.H.; Blumberger, D.M. , Efficacy, tolerability, and cognitive effects of deep transcranial magnetic stimulation for late-life depression: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 2018, 43, 2231–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levkovitz, Y.; Isserles, M.; Padberg, F.; Lisanby, S.H.; Bystritsky, A.; Xia, G.; Tendler, A.; Daskalakis, Z.J.; Winston, J.L.; Dannon, P.; Hafez, H.M.; Reti, I.M.; Morales, O.G.; Schlaepfer, T.E.; Hollander, E.; Berman, J.A.; Husain, M.M.; Sofer, U.; Stein, A.; Adler, S.; Deutsch, L.; Deutsch, F.; Roth, Y.; George, M.S.; Zangen, A. , Efficacy and safety of deep transcranial magnetic stimulation for major depression: a prospective multicenter randomized controlled trial. World Psychiatry 2015, 14, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modirrousta, M.; Meek, B.P.; Wikstrom, S.L. , Efficacy of twice-daily vs once-daily sessions of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of major depressive disorder: a retrospective study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2018, 14, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, D.F.; Myczkowski, M.L.; Alberto, R.L.; Valiengo, L.; Rios, R.M.; Gordon, P.; de Sampaio-Junior, B.; Klein, I.; Mansur, C.G.; Marcolin, M.A.; Lafer, B.; Moreno, R.A.; Gattaz, W.; Daskalakis, Z.J.; Brunoni, A.R. , Treatment of Bipolar Depression with Deep TMS: Results from a Double-Blind, Randomized, Parallel Group, Sham-Controlled Clinical Trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 2017, 42, 2593–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ridder, D.; Vanneste, S.; Kovacs, S.; Sunaert, S.; Dom, G. , Transient alcohol craving suppression by rTMS of dorsal anterior cingulate: an fMRI and LORETA EEG study. Neurosci Lett 2011, 496, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekhtiari, H.; Tavakoli, H.; Addolorato, G.; Baeken, C.; Bonci, A.; Campanella, S.; Castelo-Branco, L.; Challet-Bouju, G.; Clark, V.P.; Claus, E.J.N. , Transcranial electrical and magnetic stimulation (tES and TMS) for addiction medicine: a consensus paper on the present state of the science and the road ahead. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2019, 104, 118–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppner, J.; Broese, T.; Wendler, L.; Berger, C.; Thome, J. , Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) for treatment of alcohol dependence. World J Biol Psychiatry 2011, 12 Suppl 1 (sup1), 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makani, R.; Pradhan, B.; Shah, U.; Parikh, T. , Role of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS) in Treatment of Addiction and Related Disorders: A Systematic Review. Curr Drug Abuse Rev 2017, 10, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, D.; Urban, N.; Grassetti, A.; Chang, D.; Hu, M.-C.; Zangen, A.; Levin, F.R.; Foltin, R.; Nunes, E.V.J. , Transcranial magnetic stimulation of medial prefrontal and cingulate cortices reduces cocaine self-administration: a pilot study. Front Psychiatry 2018, 9, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, B.R.; Nizamie, S.H.; Das, B.; Praharaj, S.K. , Efficacy of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in alcohol dependence: a sham-controlled study. Addiction 2009, 105, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Politi, E.; Fauci, E.; Santoro, A.; Smeraldi, E. , Daily sessions of transcranial magnetic stimulation to the left prefrontal cortex gradually reduce cocaine craving. Am J Addict 2008, 17, 345–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapinesi, C.; Del Casale, A.; Di Pietro, S.; Ferri, V.R.; Piacentino, D.; Sani, G.; Raccah, R.N.; Zangen, A.; Ferracuti, S.; Vento, A.E.; Angeletti, G.; Brugnoli, R.; Kotzalidis, G.D.; Girardi, P. , Add-on high frequency deep transcranial magnetic stimulation (dTMS) to bilateral prefrontal cortex reduces cocaine craving in patients with cocaine use disorder. Neurosci Lett 2016, 629, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Zhong, N.; Gan, H.; Wang, J.; Han, H.; Chen, T.; Li, X.; Ruan, X.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, H.; Zhao, M. , High frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex for methamphetamine use disorders: A randomised clinical trial. Drug Alcohol Depend 2017, 175, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terraneo, A.; Leggio, L.; Saladini, M.; Ermani, M.; Bonci, A.; Gallimberti, L. , Transcranial magnetic stimulation of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex reduces cocaine use: A pilot study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2016, 26, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wing, V.C.; Barr, M.S.; Wass, C.E.; Lipsman, N.; Lozano, A.M.; Daskalakis, Z.J.; George, T.P. , Brain stimulation methods to treat tobacco addiction. Brain Stimul 2013, 6, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangen, A.; Moshe, H.; Martinez, D.; Barnea-Ygael, N.; Vapnik, T.; Bystritsky, A.; Duffy, W.; Toder, D.; Casuto, L.; Grosz, M.L. , Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for smoking cessation: a pivotal multicenter double-blind randomized controlled trial. J World Psychiatry 2021, 20, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Larrea, L. , Non-invasive cortical stimulation for drug-resistant pain. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2023, 17, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, B.Y.; Zeng, B.S.; Chen, Y.W.; Hung, C.M.; Sun, C.K.; Cheng, Y.S.; Stubbs, B.; Carvalho, A.F.; Brunoni, A.R.; Su, K.P.; Tu, Y.K.; Wu, Y.C.; Chen, T.Y.; Lin, P.Y.; Liang, C.S.; Hsu, C.W.; Tseng, P.T.; Li, C.T. , Efficacy and acceptability of noninvasive brain stimulation interventions for weight reduction in obesity: a pilot network meta-analysis. Int J Obes (Lond) 2021, 45, 1705–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnolo, P.A.; Wang, H.; Srivanitchapoom, P.; Schwandt, M.; Heilig, M.; Hallett, M. , Lack of Target Engagement Following Low-Frequency Deep Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation of the Anterior Insula. Neuromodulation 2019, 22, 877–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, S.; Jacobs, M.; Cho, S.S.; Boileau, I.; Blumberger, D.; Heilig, M.; Wilson, A.; Daskalakis, Z.J.; Strafella, A.P.; Zangen, A.; Le Foll, B. , Deep TMS of the insula using the H-coil modulates dopamine release: a crossover [(11)C] PHNO-PET pilot trial in healthy humans. Brain Imaging Behav 2018, 12, 1306–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinur-Klein, L.; Dannon, P.; Hadar, A.; Rosenberg, O.; Roth, Y.; Kotler, M.; Zangen, A. , Smoking cessation induced by deep repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the prefrontal and insular cortices: a prospective, randomized controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry 2014, 76, 742–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, C.; Tang, V.M.; Blumberger, D.M.; Malik, S.; Tyndale, R.F.; Trevizol, A.P.; Barr, M.S.; Daskalakis, Z.J.; Zangen, A.; Le Foll, B. , Efficacy of insula deep repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation combined with varenicline for smoking cessation: A randomized, double-blind, sham controlled trial. Brain Stimul 2023, 16, 1501–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenoir, C.; Algoet, M.; Mouraux, A. , Deep continuous theta burst stimulation of the operculo-insular cortex selectively affects Adelta-fibre heat pain. J Physiol 2018, 596, 4767–4787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciampi de Andrade, D.; Galhardoni, R.; Pinto, L.F.; Lancelotti, R.; Rosi, J., Jr.; Marcolin, M.A.; Teixeira, M.J. , Into the island: a new technique of non-invasive cortical stimulation of the insula. Neurophysiol Clin 2012, 42, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dongyang, L.; Fernandes, A.M.; da Cunha, P.H.M.; Tibes, R.; Sato, J.; Listik, C.; Dale, C.; Kubota, G.T.; Galhardoni, R.; Teixeira, M.J.; Aparecida da Silva, V.; Rosi, J.; Ciampi de Andrade, D. , Posterior-superior insular deep transcranial magnetic stimulation alleviates peripheral neuropathic pain - A pilot double-blind, randomized cross-over study. Neurophysiol Clin 2021, 51, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knyahnytska, Y.O.; Blumberger, D.M.; Daskalakis, Z.J.; Zomorrodi, R.; Kaplan, A.S. , Insula H-coil deep transcranial magnetic stimulation in severe and enduring anorexia nervosa (SE-AN): a pilot study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2019, 15, 2247–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bestmann, S.; Ruff, C.C.; Blankenburg, F.; Weiskopf, N.; Driver, J.; Rothwell, J.C. , Mapping causal interregional influences with concurrent TMS-fMRI. Exp Brain Res 2008, 191, 383–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwabuchi, S.J.; Raschke, F.; Auer, D.P.; Liddle, P.F.; Lankappa, S.T.; Palaniyappan, L. , Targeted transcranial theta-burst stimulation alters fronto-insular network and prefrontal GABA. Neuroimage 2017, 146, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addicott, M.A.; Luber, B.; Nguyen, D.; Palmer, H.; Lisanby, S.H.; Appelbaum, L.G. , Low-and high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation effects on resting-state functional connectivity between the postcentral gyrus and the insula. J Brain connectivity 2019, 9, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Small, D.M. , Taste representation in the human insula. Brain Struct Funct 2010, 214, (5–6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avery, J.A.; Gotts, S.J.; Kerr, K.L.; Burrows, K.; Ingeholm, J.E.; Bodurka, J.; Martin, A.; Kyle Simmons, W. , Convergent gustatory and viscerosensory processing in the human dorsal mid-insula. Hum Brain Mapp 2017, 38, 2150–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolls, E.T. , Functions of the anterior insula in taste, autonomic, and related functions. Brain Cogn 2016, 110, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, D.M.; Gregory, M.D.; Mak, Y.E.; Gitelman, D.; Mesulam, M.M.; Parrish, T. , Dissociation of neural representation of intensity and affective valuation in human gustation. Neuron 2003, 39, 701–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jesus, D.R.; de Souza Favalli, G.P.; Hoppenbrouwers, S.S.; Barr, M.S.; Chen, R.; Fitzgerald, P.B.; Daskalakis, Z.J. , Determining optimal rTMS parameters through changes in cortical inhibition. J Clinical Neurophysiology 2014, 125, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzgerald, P.B.; Fountain, S.; Daskalakis, Z.J. , A comprehensive review of the effects of rTMS on motor cortical excitability and inhibition. Clin Neurophysiol 2006, 117, 2584–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, F.; Keenan, J.P.; Tormos, J.M.; Topka, H.; Pascual-Leone, A. , Interindividual variability of the modulatory effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on cortical excitability. Exp Brain Res 2000, 133, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.H.; Tang, C.C.; Eidelberg, D. , Brain stimulation and functional imaging with fMRI and PET. Handb Clin Neurol 2013, 116, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pascual-Leone, A.; Valls-Sole, J.; Wassermann, E.M.; Hallett, M. , Responses to rapid-rate transcranial magnetic stimulation of the human motor cortex. Brain 1994, 117 Pt 4, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaziri, J.; Fei, P.; Tucholka, A.; Obaid, S.; Boucher, O.; Rouleau, I.; Nguyen, D.K. , Resting-State Functional Connectivity Profile of Insular Subregions. Brain Sci 2024, 14, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimomura, T.; Fujiki, M.; Ohba, H.; Kochiyma, T.; Sugita, K.; Matsuta, H.; Kawasaki, Y.; Oonishi, K.; Fudaba, H.; Kamida, T.J.J.N.N., Contralateral negative bold responses in the motor network during subthreshold high-frequency interleaved TMS-fMRI over the human primary motor cortex. 2018, 9, 1–8.

- Tian, D.; Izumi, S.I. , Interhemispheric Facilitatory Effect of High-Frequency rTMS: Perspective from Intracortical Facilitation and Inhibition. Brain Sci 2022, 12, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, T.; Hanajima, R.; Shirota, Y.; Ohminami, S.; Tsutsumi, R.; Terao, Y.; Ugawa, Y.; Hirose, S.; Miyashita, Y.; Konishi, S.; Kunimatsu, A.; Ohtomo, K. , Bidirectional effects on interhemispheric resting-state functional connectivity induced by excitatory and inhibitory repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. Hum Brain Mapp 2014, 35, 1896–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plow, E.B.; Cattaneo, Z.; Carlson, T.A.; Alvarez, G.A.; Pascual-Leone, A.; Battelli, L. , The compensatory dynamic of inter-hemispheric interactions in visuospatial attention revealed using rTMS and fMRI. Front Hum Neurosci 2014, 8, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Ueno, S. , Comparison of the induced fields using different coil configurations during deep transcranial magnetic stimulation. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0178422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.R.; Caparelli, E.C.; Leff, M.; Steele, V.R.; Maxwell, A.M.; McCullough, K.; Salmeron, B.J.J.N.T. a. t. N. I., Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation delivered with an H-coil to the right insula reduces functional connectivity between insula and medial prefrontal cortex. 2020, 23, 384–392.

- Perini, I.; Kampe, R.; Arlestig, T.; Karlsson, H.; Lofberg, A.; Pietrzak, M.; Zangen, A.; Heilig, M. , Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation targeting the insular cortex for reduction of heavy drinking in treatment-seeking alcohol-dependent subjects: a randomized controlled trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 2020, 45, 842–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodkinson, D.J.; Bungert, A.; Bowtell, R.; Jackson, S.R.; Jung, J. , Operculo-insular and anterior cingulate plasticity induced by transcranial magnetic stimulation in the human motor cortex: a dynamic casual modeling study. J Neurophysiol 2021, 125, 1180–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moeller, S.J.; Gil, R.; Weinstein, J.J.; Baumvoll, T.; Wengler, K.; Fallon, N.; Van Snellenberg, J.X.; Abeykoon, S.; Perlman, G.; Williams, J.; Manu, L.; Slifstein, M.; Cassidy, C.M.; Martinez, D.M.; Abi-Dargham, A., Deep rTMS of the insula and prefrontal cortex in smokers with schizophrenia: Proof-of-concept study. Schizophrenia (Heidelb) 2022, 8, 6.

- Rossi, S.; Antal, A.; Bestmann, S.; Bikson, M.; Brewer, C.; Brockmoller, J.; Carpenter, L.L.; Cincotta, M.; Chen, R.; Daskalakis, J.D.; Di Lazzaro, V.; Fox, M.D.; George, M.S.; Gilbert, D.; Kimiskidis, V.K.; Koch, G.; Ilmoniemi, R.J.; Lefaucheur, J.P.; Leocani, L.; Lisanby, S.H.; Miniussi, C.; Padberg, F.; Pascual-Leone, A.; Paulus, W.; Peterchev, A.V.; Quartarone, A.; Rotenberg, A.; Rothwell, J.; Rossini, P.M.; Santarnecchi, E.; Shafi, M.M.; Siebner, H.R.; Ugawa, Y.; Wassermann, E.M.; Zangen, A.; Ziemann, U.; Hallett, M.; basis of this article began with a Consensus Statement from the Ifcn Workshop on "Present, F. o. T. M. S. S. E. G. S. O. u. t. A., Safety and recommendations for TMS use in healthy subjects and patient populations, with updates on training, ethical and regulatory issues: Expert Guidelines. Clin Neurophysiol 2021, 132, 269–306.

- Koponen, L.M.; Nieminen, J.O.; Ilmoniemi, R.J. , Multi-locus transcranial magnetic stimulation-theory and implementation. Brain Stimul 2018, 11, 849–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieminen, J.O.; Koponen, L.M.; Ilmoniemi, R.J. , Experimental Characterization of the Electric Field Distribution Induced by TMS Devices. Brain Stimul 2015, 8, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebner, H.R.; Bergmann, T.O.; Bestmann, S.; Massimini, M.; Johansen-Berg, H.; Mochizuki, H.; Bohning, D.E.; Boorman, E.D.; Groppa, S.; Miniussi, C.; Pascual-Leone, A.; Huber, R.; Taylor, P.C.; Ilmoniemi, R.J.; De Gennaro, L.; Strafella, A.P.; Kahkonen, S.; Kloppel, S.; Frisoni, G.B.; George, M.S.; Hallett, M.; Brandt, S.A.; Rushworth, M.F.; Ziemann, U.; Rothwell, J.C.; Ward, N.; Cohen, L.G.; Baudewig, J.; Paus, T.; Ugawa, Y.; Rossini, P.M., Consensus paper: combining transcranial stimulation with neuroimaging. Brain Stimul 2009, 2, 58–80.

| Subjects | Sex | Motor threshold parameters | Reason of exclusion | ||

| Stimulation threshold | Stimulation intensity | Stimulation amplitude | |||

| SBJ1 | F | 69 | 75% | 52 | - |

| SBJ2 | F | 69 | 75% | 52 | - |

| SBJ3 | M | 77 | 60% | 50 | - |

| SBJ4 | F | 63 | 70% | 45 | - |

| SBJ5 | M | 60 | 60% | 36 | Stimulation interrupted: Pain at right temple |

| SBJ6 | M | 55 | 70% | 39 | - |

| SBJ7 | F | - | - | - | Participation declined |

| SBJ8 | M | - | - | - | Exclusion: Contraindication for rTMS-MRI |

| SBJ9 | F | 69 | 75% | 52 | - |

| SBJ10 | M | - | - | - | Technical issue: rTMS coil malfunction |

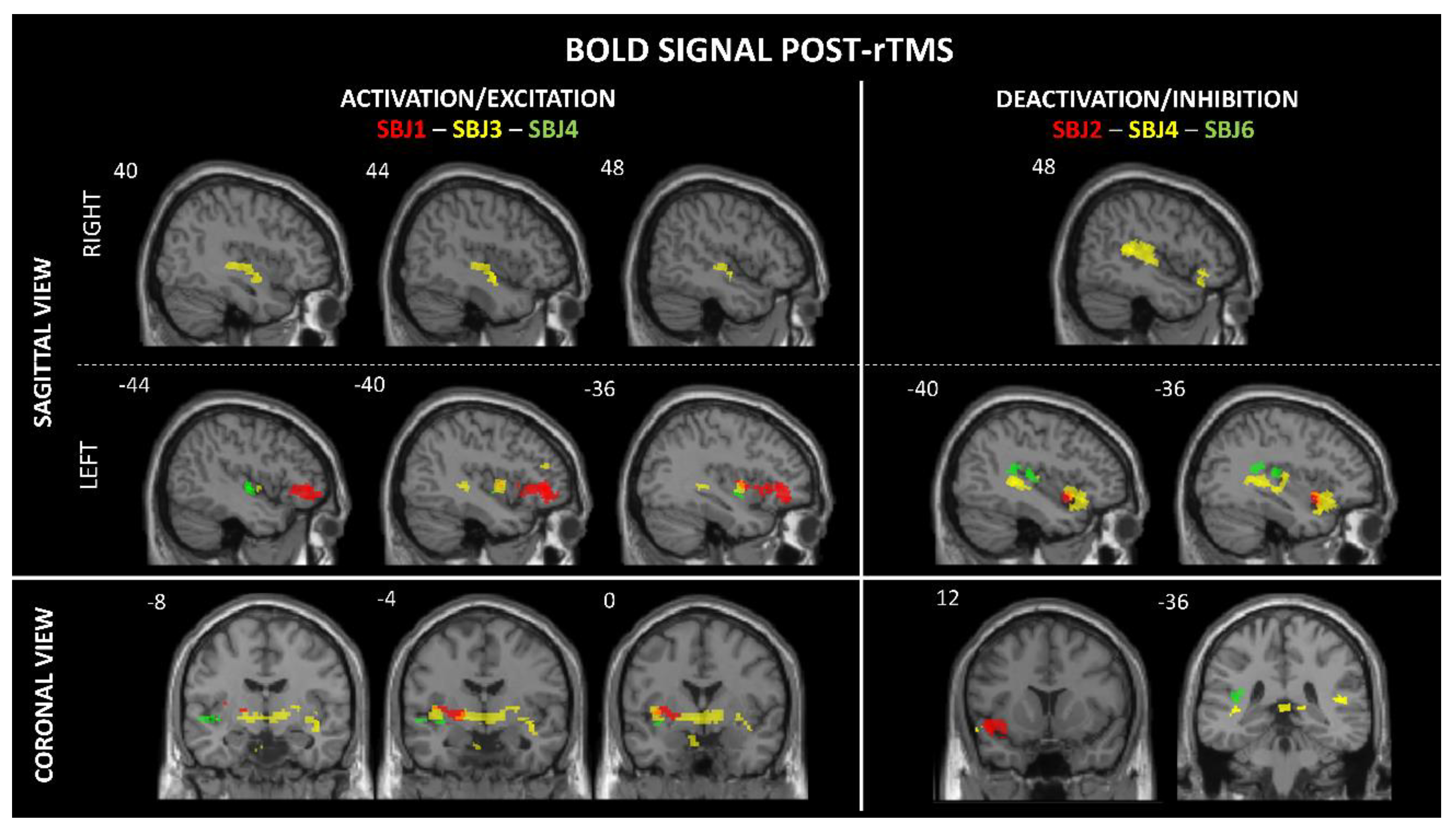

| Brainsight parameters | MNI coordinates | BOLD signal activity |

Side | T-Value | Cluster size | FDR- correction |

Sensory responses induced by rTMS |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Targeted insular subregions | Significant BOLD changes in the insular subregions |

x | y | z | |||||||

| SBJ1 | mid-pI | middle/aI | -34 | 11 | -3 | A | L | 3.17 | 23 | < 0.001 | Metallic taste |

| middle | -41 | -1 | 1 | A | L | 3.35 | 10 | < 0.001 | |||

| SBJ2 | ventral aI | ventral aI | -34 | 12 | -15 | D | L | 3.27 | 67 | < 0.001 | - |

| SBJ3 | aI | middle | -39 | -1 | -2 | A | L | 3.32 | 34 | < 0.001 | - |

| mid-inferior | 39 | -12 | -3 | A | R | 2.73 | 47 | < 0.001 | |||

| SBJ4 | Inferior pI | mid-inferior | -35 | -4 | -7 | A | L | 2.36 | 20 | 0.05 * | Metallic taste |

| pI | 39 | -25 | 4 | D | R | 2.18 | 131 | < 0.01 | |||

| pI | -36 | -18 | 6 | D | L | 1.88 | 134 | < 0.01 | |||

| aI | -34 | 11 | -14 | D | L | 2.56 | 189 | < 0.01 | |||

| SBJ6 | Superior pI | pI | -43 | -25 | 16 | A | L | 3.22 | 54 | < 0.001 | - |

| SBJ9 | Inferior pI | Excluded from analysis due to excessive noise contamination | |||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).