Submitted:

25 May 2025

Posted:

26 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

The Case

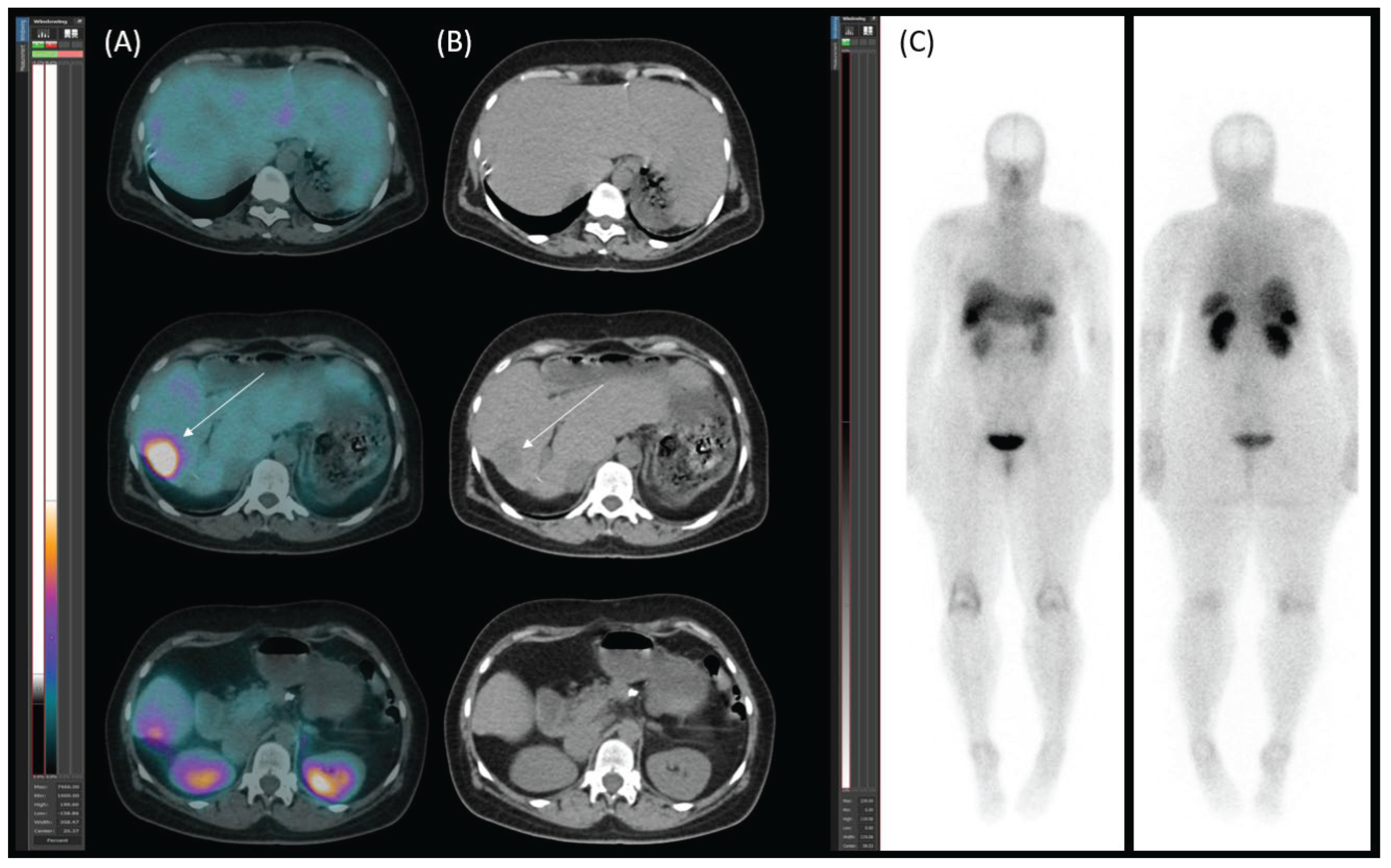

Diagnostic Procedures

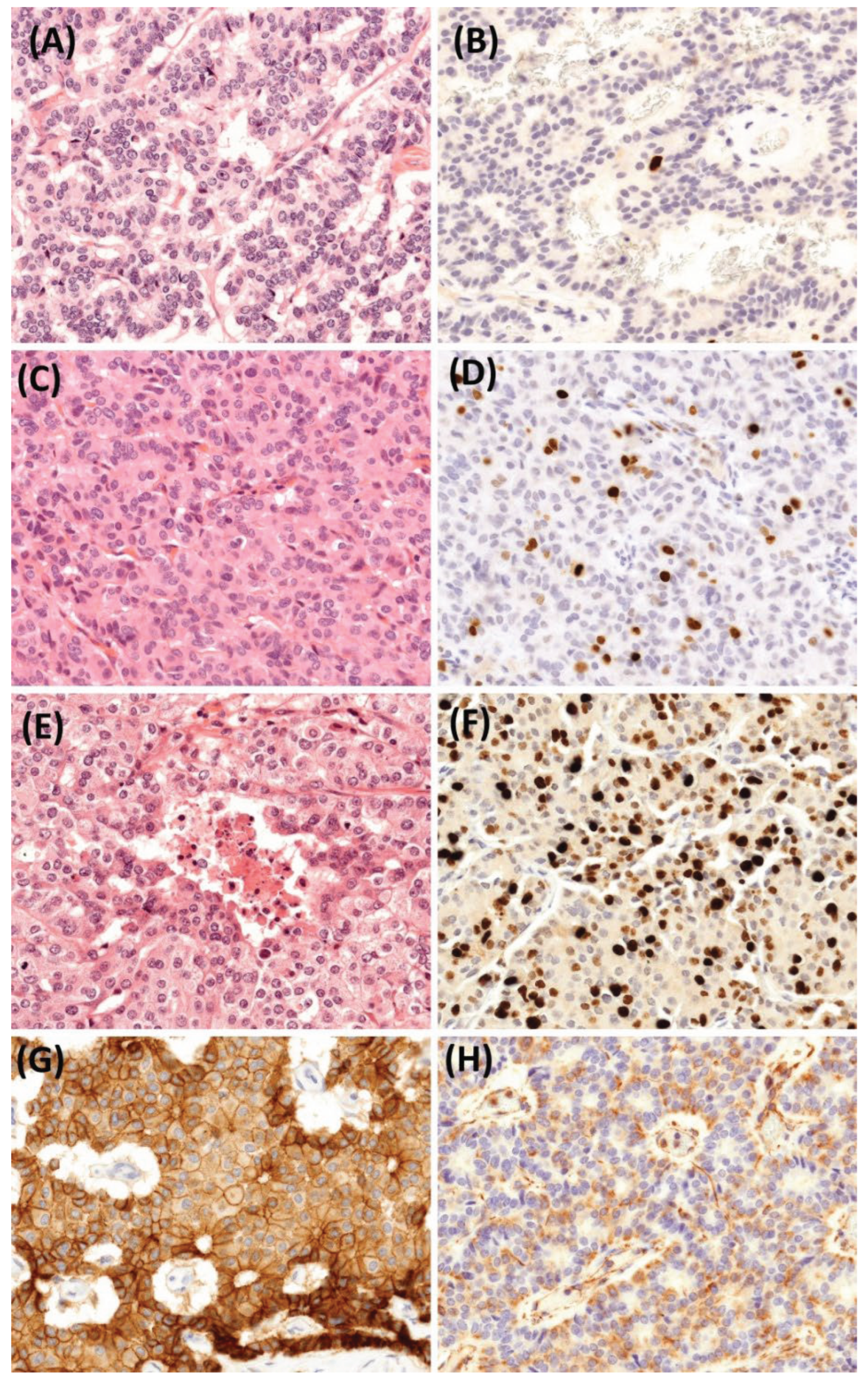

Histology

Discussion

Limitation

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Consent for Publication

Availability of Data and Material

Aknowledgments

Competing Interests

References

- Fraenkel M, Kim M, Faggiano A, de Herder WW, Valk GD; Knowledge NETwork. Incidence of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours: a systematic review of the literature. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21(3):R153-R163. Published 2014 May 6. [CrossRef]

- Leoncini E, Boffetta P, Shafir M, Aleksovska K, Boccia S, Rindi G. Increased incidence trend of low-grade and high-grade neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocrine. 2017;58(2):368-379. [CrossRef]

- Huguet I, Grossman AB, O’Toole D. Changes in the Epidemiology of Neuroendocrine Tumours. Neuroendocrinology. 2017;104(2):105-111. [CrossRef]

- Niederle MB, Hackl M, Kaserer K, Niederle B. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours: the current incidence and staging based on the WHO and European Neuroendocrine Tumour Society classification: an analysis based on prospectively collected parameters. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17(4):909-918. Published 2010 Oct 5. [CrossRef]

- Pavel M, Öberg K, Falconi M, et al. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(7):844-860. [CrossRef]

- Fischer L, Bergmann F, Schimmack S, et al. Outcome of surgery for pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Br J Surg. 2014;101(11):1405-1412. [CrossRef]

- Frilling A, Modlin IM, Kidd M, et al. Recommendations for management of patients with neuroendocrine liver metastases. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(1):e8-e21. [CrossRef]

- Primavesi F, Maglione M, Cipriani F, et al. E-AHPBA-ESSO-ESSR Innsbruck consensus guidelines for preoperative liver function assessment before hepatectomy. Br J Surg. 2023;110(10):1331-1347. [CrossRef]

- Tada T, Kumada T, Toyoda H, et al. Utility of real-time shear wave elastography for assessing liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C infection without cirrhosis: Comparison of liver fibrosis indices. Hepatol Res. 2015;45(10):E122-E129. [CrossRef]

- Bakos A, Libor L, Urbán S, et al. Dynamic [99mTc]Tc-mebrofenin SPECT/CT in preoperative planning of liver resection: a prospective study. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):30305. Published 2024 Dec 5. [CrossRef]

- Zhou B, Xiang J, Jin M, Zheng X, Li G, Yan S. High vimentin expression with E-cadherin expression loss predicts a poor prognosis after resection of grade 1 and 2 pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. BMC Cancer. 2021;21(1):334. Published 2021 Mar 31. [CrossRef]

- Guo Y, Jiang Y, Rose JB, et al. Protein Kinase D1 Signaling in Cancer Stem Cells with Epithelial-Mesenchymal Plasticity. Cells. 2022;11(23):3885. Published 2022 Dec 1. [CrossRef]

- Alexandraki KI, Spyroglou A, Kykalos S, et al. Changing biological behaviour of NETs during the evolution of the disease: progress on progression. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2021;28(5):R121-R140. Published 2021 Apr 29. [CrossRef]

- Singh S, Halperin D, Myrehaug S, et al. [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-TATE plus long-acting octreotide versus high-dose long-acting octreotide for the treatment of newly diagnosed, advanced grade 2-3, well-differentiated, gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (NETTER-2): an open-label, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2024;403(10446):2807-2817. [CrossRef]

- Arntz PJW, Deroose CM, Marcus C, et al. Joint EANM/SNMMI/IHPBA procedure guideline for [99mTc]Tc-mebrofenin hepatobiliary scintigraphy SPECT/CT in the quantitative assessment of the future liver remnant function. HPB (Oxford). 2023;25(10):1131-1144. [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner R, Gilg S, Björnsson B, et al. Impact of post-hepatectomy liver failure on morbidity and short- and long-term survival after major hepatectomy. BJS Open. 2022;6(4):zrac097. [CrossRef]

- Kim RD, Kim JS, Watanabe G, Mohuczy D, Behrns KE. Liver regeneration and the atrophy-hypertrophy complex. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2008;25(2):92-103. [CrossRef]

- Garcovich M, Paratore M, Riccardi L, et al. Correlation between a New Point-Shear Wave Elastography Device (X+pSWE) with Liver Histology and 2D-SWE (SSI) for Liver Stiffness Quantification in Chronic Liver Disease. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13(10):1743. Published 2023 May 15. [CrossRef]

- Mariën L, Islam O, Van Mileghem L, Lybaert W, Peeters M, Vandamme T. Pathophysiology and Treatment of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms (PNENS): New Developments. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, et al., eds. Endotext. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; April 8, 2022.

- Nobels FR, Kwekkeboom DJ, Coopmans W, et al. Chromogranin A as serum marker for neuroendocrine neoplasia: comparison with neuron-sp ecific enolase and the alpha-subunit of glycoprotein hormones. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82(8):2622-2628. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).