Submitted:

23 May 2025

Posted:

26 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material and Methods

2.2. Patient Selection

2.3. Ethical Consideration

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

| Hemodialysis | Peritoneal dialysis | Total | p-Value | ||||

| N/Mean | N%/SD | N/Mean | N%/SD | N/Mean | N%/SD | ||

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 21 | 38.2% | 15 | 44.1% | 36 | 40.4% | 0.579 |

| Male | 34 | 61.8% | 19 | 55.9% | 53 | 59.6% | |

| Age | |||||||

| Years | 58 | 17 | 48 | 20 | 54 | 19 | 0.499 |

3.2. Baseline Biochemical and Hematological Parameters

| Tests of Normality | |||||||

| Kolmogorov-Smirnova | Shapiro-Wilk | ||||||

| Statistic | df | Sig. | Statistic | df | Sig. | ||

| Hgb | .074 | 97 | .200* | .986 | 97 | .407 | |

| Ferritin | .193 | 97 | <.001 | .699 | 97 | <.001 | |

| Tsat | .240 | 97 | <.001 | .439 | 97 | <.001 | |

| Ca | .124 | 97 | <.001 | .878 | 97 | <.001 | |

| Phos | .518 | 97 | <.001 | .135 | 97 | <.001 | |

| PTH | .168 | 97 | <.001 | .868 | 97 | <.001 | |

| Vit D | .120 | 97 | .002 | .910 | 97 | <.001 | |

| BUN | .286 | 97 | <.001 | .387 | 97 | <.001 | |

| K | .097 | 97 | .025 | .977 | 97 | .085 | |

| HCO3 | .075 | 97 | .200* | .976 | 97 | .072 | |

| Na | .117 | 97 | .002 | .944 | 97 | <.001 | |

3.3. Anemia and Iron Status

3.5. Biochemical Markers

3.6. Subgroup Analysis by Gender

3.7. Age Correlation

| Haemodialysis | Peritoneal dialysis | ||

| Age | Age | ||

| Anemia | |||

| Hgb | Pearson Correlation | -.076 | .233 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .582 | .184 | |

| Ferritin | Pearson Correlation | .022 | -.008 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .878 | .966 | |

| Tsat | Pearson Correlation | -.077 | .044 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .590 | .819 | |

| Bone profile | |||

| Ca | Pearson Correlation | .062 | -.306 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .656 | .078 | |

| Phos | Pearson Correlation | -.179 | -.388 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .190 | .023 | |

| PTH | Pearson Correlation | -.232 | -.352 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .098 | .052 | |

| Vit D | Pearson Correlation | .180 | .840 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .222 | .160 | |

| Biochemical | |||

| BUN | Pearson Correlation | .109 | -.034 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .427 | .850 | |

| K | Pearson Correlation | .080 | .020 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .561 | .909 | |

| HCO3 | Pearson Correlation | -.174 | -.033 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .209 | .855 | |

| Na | Pearson Correlation | -.189 | .323 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .167 | .062 | |

4. Discussion

4.1. Anemia Management

4.2. Bone Mineral Metabolism and CKD-MBD

4.3. Biochemical Parameters

4.4. Gender-Based Insights

4.5. Age-Related Correlations

4.6. Clinical Implications

4.7. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ESRD | End-Stage Renal Disease |

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

| HD | Hemodialysis |

| PD | Peritoneal Dialysis |

| HRQoL | Health-Related Quality of Life |

| GFR | Glomerular Filtration Rate |

| PTH | Parathyroid hormone |

| Hb/Hgb | Hemoglobin |

| Na | Sodium |

| Ca | Calcium |

| K | Potassium |

| Phos | Phosphate |

| Vit D | Vitamin D |

| BUN | Blood Urea Nitrogen |

| HCO3 | Bicarbonate |

| Tsat | Transferrin Saturation |

| CRF | Case Report Form |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

References

- Yılmaz, Z., Yıldırım, Y., Aydın, F. Y., Aydın, E., Kadiroğlu, A. K., Yılmaz, M. E., & Acet, H. (2014). Evaluation of fluid status related parameters in hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients: Clinical usefulness of bioimpedance analysis. Medicina, 50(5), 269–274. [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, Y., Higuchi, C., Io, H., Wakabayashi, K., Tsujimoto, H., Tsujimoto, Y., Yuasa, H., Ryuzaki, M., Ito, Y., & Nakamoto, H. (2019). Comparison of peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis as first renal replacement therapy in patients with end-stage renal disease and diabetes: a systematic review. Renal Replacement Therapy, 5(1). [CrossRef]

- Hu, L., Napoletano, A., Provenzano, M., Garofalo, C., Bini, C., Comai, G., & La Manna, G. (2022). Mineral bone Disorders in kidney Disease Patients: The Ever-Current Topic. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(20), 12223. [CrossRef]

- Chuasuwan, A., Pooripussarakul, S., Thakkinstian, A., Ingsathit, A., & Pattanaprateep, O. (2020). Comparisons of quality of life between patients underwent peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 18(1). [CrossRef]

- Xu, X., Han, X., Yang, Y., & Li, X. (2020). Comparative study on the efficacy of peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis in patients with end-stage diabetic nephropathy. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 36(7). [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. (2023). Comparison of the effect of hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis in the treatment of end-stage renal disease. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 39(6). [CrossRef]

- Bello, A. K., Okpechi, I. G., Osman, M. A., Cho, Y., Htay, H., Jha, V., Wainstein, M., & Johnson, D. W. (2022). Epidemiology of haemodialysis outcomes. Nature Reviews Nephrology, 18(6), 378–395. [CrossRef]

- Jin, H., Fang, W., Zhu, M., Yu, Z., Fang, Y., Yan, H., Zhang, M., Wang, Q., Che, X., Xie, Y., Huang, J., Hu, C., Zhang, H., Mou, S., & Ni, Z. (2016). Urgent-Start Peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis in ESRD patients: Complications and outcomes. [CrossRef]

- Treacy, O., Brown, N. N., & Dimeski, G. (2019). Biochemical evaluation of kidney disease. Translational Andrology and Urology, 8(S2), S214–S223. [CrossRef]

- Van Lieshout, T. S., Klerks, A. K., Mahic, O., Vernooij, R. W. M., Eisenga, M. F., Van Jaarsveld, B. C., & Abrahams, A. C. (2024). Comparative iron management in hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients: a systematic review. Frontiers in Nephrology, 4. [CrossRef]

- Ewedah, A., Kora, M. E., Zahran, A., & El-Zorkany, K. A. (2019). Hemodialysis versus peritoneal dialysis: a comparative study Menoufia Medical Journal. Menoufia Medical Journal. [CrossRef]

- Abe, M., Okada, K., & Soma, M. (2013). Mineral metabolic abnormalities and mortality in dialysis patients. Nutrients, 5(3), 1002–1023. [CrossRef]

- Moldovan, D., Rusu, C., Kacso, I. M., Potra, A., Patiu, I. M., & Gherman-Caprioara, M. (2015). Mineral and bone disorders, morbidity and mortality in end-stage renal failure patients on chronic dialysis. Medicine and Pharmacy Reports, 89(1), 94–103. [CrossRef]

- Dang, Z., Tang, C., Li, G., Luobu, C., Qing, D., Ma, Z., Qu, J., Suolang, L., & Liu, L. (2019). Mineral and bone disorder in hemodialysis patients in the Tibetan Plateau: a multicenter cross-sectional study. Renal Failure, 41(1), 636–643. [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, A., Ersoy, F., Passadakis, P., Tam, P., Evaggelos, D., Katopodis, K., Özener, Ç., Akçiçek, F., Çamsari, T., Ateş, K., Ataman, R., Vlachojannis, G., Dombros, N., Utaş, C., Akpolat, T., Bozfakioğlu, S., Wu, G., Karayaylali, I., Arinsoy, T., . . . Oreopoulos, D. (2008). Phosphorus control in peritoneal dialysis patients. Kidney International, 73, S152–S158. [CrossRef]

- Tamimi, R., Bdair, A., Shratih, A., Abdalla, M., Sarsour, A., Hamdan, Z., & Nazzal, Z. (2024). Bone mineral density and related clinical and laboratory factors in peritoneal dialysis patients: Implications for bone health management. PLoS ONE, 19(5), e0301814. [CrossRef]

- National Kidney Foundation. KDOQI clinical practice guideline for hemodialysis adequacy: 2015 update. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66(5):884-930. [CrossRef]

- Albalawi, A. M., Dera, A. A., Rajagopalan, P., Maqsood, S., Kashif, F. S., & Mansoor, N. (2023). Effect of dialysis on biochemical parameters in chronic renal failure patients: a cross-sectional study. International Journal of Biochemistry Research & Review, 32(2), 32–37. [CrossRef]

- Sanabria, M., Muñoz, J., Trillos, C., Hernández, G., Latorre, C., Díaz, C., Murad, S., Rodríguez, K., Rivera, Á., Amador, A., Ardila, F., Caicedo, A., Camargo, D., Díaz, A., González, J., Leguizamón, H., Lopera, P., Marín, L., Nieto, I., & Vargas, E. (2008). Dialysis outcomes in Colombia (DOC) study: A comparison of patient survival on peritoneal dialysis vs hemodialysis in Colombia. Kidney International, 73, S165–S172. [CrossRef]

| a) | |||||

| Hemodialysis | Peritoneal dialysis | p-Value | |||

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | |

| Anemia | |||||

| Hgb | 9.2 (2.0) | 8.9 (7.8–10.8) | 9.5 (1.8) | 9.4 (8.1–10.8) | 0.449 |

| Ferritin | 429.07 (302.59) | 353.00 (211.90–560.60) | 471.08 (931.59) | 263.00 (136.30–402.00) | 0.077 |

| Tsat | 32.19 (40.36) | 24.10 (17.20–29.00) | 32.28 (24.15) | 26.00 (21.30–37.90) | 0.342 |

| Bone profile | |||||

| Ca | 2.17 (.37) | 2.26 (1.97–2.39) | 2.16 (.21) | 2.19 (2.03–2.33) | 0.618 |

| Phos | 6.79 (38.90) | 1.59 (1.05–1.99) | 1.87 (.50) | 1.78 (1.49–2.20) | 0.026 |

| PTH | 56.82 (39.44) | 46.00 (31.40–79.20) | 66.34 (70.13) | 46.00 (31.00–83.00) | 0.724 |

| Vit D | 46.83 (30.07) | 40.42 (25.87–56.90) | 35.18 (18.14) | 28.00 (26.00–35.90) | 0.468 |

| Biochemical | |||||

| BUN | 39.3 (86.6) | 20.6 (13.0–31.1) | 26.7 (9.0) | 27.0 (20.0–32.0) | 0.060 |

| K | 4.26 (.77) | 4.30 (3.60–4.70) | 4.53 (.57) | 4.50 (4.30–4.90) | 0.061 |

| HCO3 | 22.1 (6.0) | 22.0 (19.0–26.0) | 27.1 (36.4) | 21.5 (19.0–24.0) | 0.324 |

| Na | 135.1 (4.2) | 135.0 (133.1–138.0) | 136.7 (3.6) | 138.0 (134.0–139.0) | 0.082 |

| b) | |||||

| Hemodialysis | Peritoneal dialysis | p-Value | |||

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | |

| Anemia | |||||

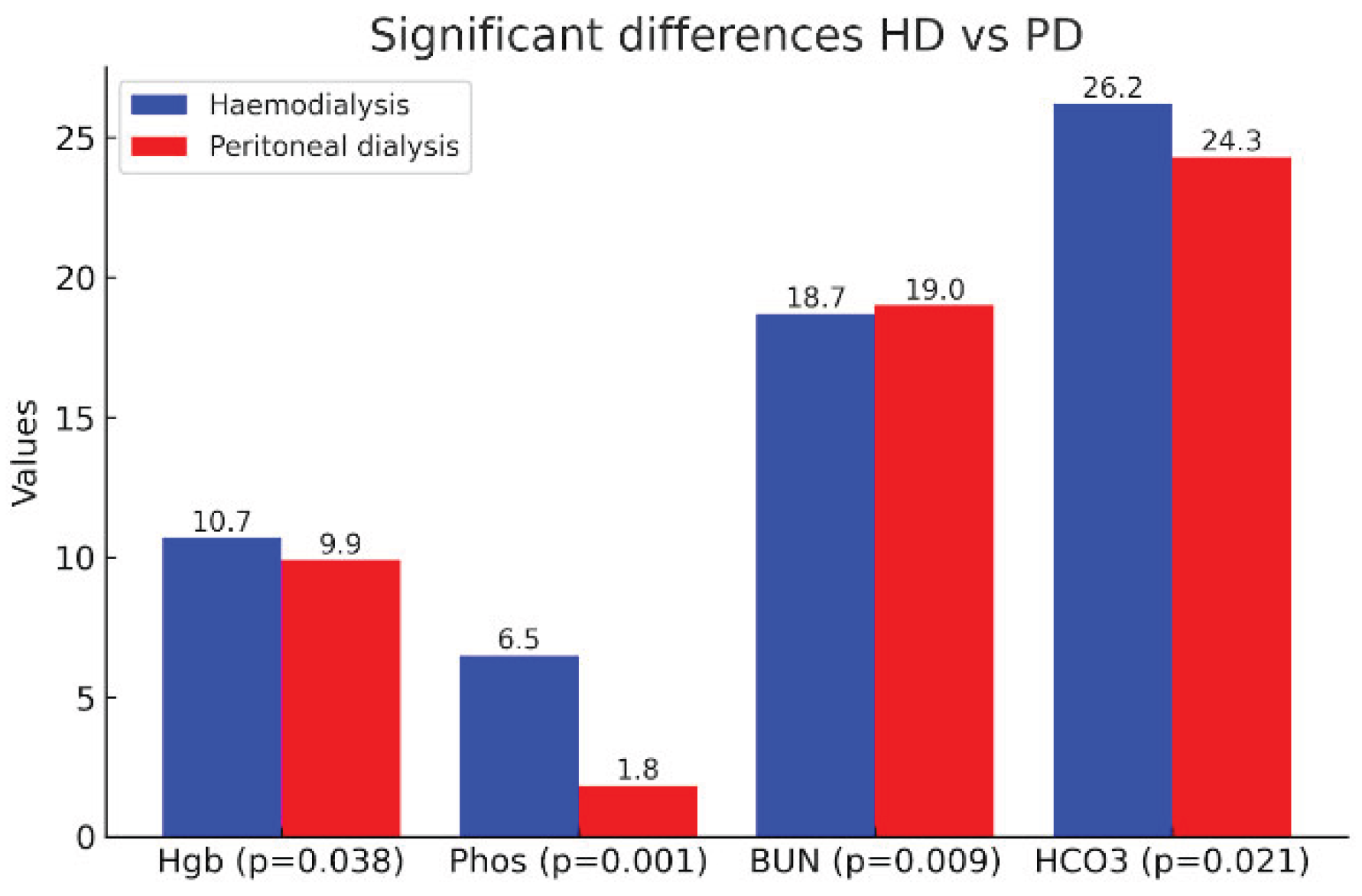

| Hgb | 10.7 (1.7) | 10.8 (9.4–11.7) | 9.9 (1.8) | 9.8 (8.6–11.4) | 0.038 |

| Ferritin | 381.10 (420.29) | 301.95 (186.05–429.50) | 536.82 (813.42) | 392.00 (183.00–589.00) | 0.303 |

| Tsat | 29.19 (12.63) | 27.80 (19.70–36.90) | 27.73 (13.21) | 27.90 (20.00–35.00) | 0.775 |

| Bone Profile | |||||

| Ca | 2.21 (.29) | 2.19 (2.06–2.33) | 2.20 (.19) | 2.20 (2.05–2.30) | 0.911 |

| Phos | 6.48 (39.21) | 1.26 (.75–1.65) | 1.84 (.43) | 1.84 (1.67–2.03) | <0.001 |

| PTH | 59.37 (43.29) | 47.30 (31.15–79.20) | 71.29 (75.90) | 45.00 (26.00–85.00) | 0.906 |

| Vit D | 49.05 (22.91) | 46.50 (29.75–62.00) | 41.00 (18.60) | 38.50 (29.50–52.50) | 0.562 |

| Biochemical | |||||

| BUN | 18.7 (28.8) | 13.7 (7.8–21.0) | 19.0 (5.6) | 17.6 (15.5–21.0) | 0.009 |

| K | 4.10 (.83) | 4.10 (3.40–4.60) | 4.31 (.48) | 4.25 (3.99–4.53) | 0.135 |

| HCO3 | 26.2 (4.5) | 26.9 (24.0–29.0) | 24.3 (3.2) | 24.0 (22.8–26.0) | 0.021 |

| Na | 136.6 (3.8) | 137.0 (134.0–138.0) | 136.6 (3.9) | 137.5 (134.0–139.0) | 0.879 |

| a) | |||||

| Hemodialysis | Peritoneal dialysis | p-Value | |||

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | |

| Anemia | |||||

| Hgb | 10.8 (1.6) | 10.8 (9.6–11.6) | 10.0 (1.6) | 10.1 (9.0–11.4) | 0.121 |

| Ferritin | 488.57 (614.47) | 354.00 (223.00–538.00) | 453.55 (359.46) | 533.00 (121.00–703.00) | 0.767 |

| Tsat | 29.45 (12.60) | 29.50 (21.90–34.00) | 24.68 (8.83) | 25.60 (19.40–31.10) | 0.412 |

| Bone profile | |||||

| Ca | 2.17 (.22) | 2.17 (2.06–2.30) | 2.21 (.19) | 2.25 (2.11–2.30) | 0.526 |

| Phos | 1.08 (.49) | .99 (.67–1.40) | 1.82 (.35) | 1.84 (1.45–1.97) | <0.001 |

| PTH | 57.90 (27.92) | 47.60 (41.10–80.40) | 114.42 (106.35) | 92.00 (33.50–154.00) | 0.252 |

| Vit D | 47.94 (22.74) | 40.40 (28.90–74.00) | 21.00 (0) | 21.00 (21.00–21.00) | 0.200 |

| Biochemical | |||||

| BUN | 21.0 (45.6) | 10.6 (4.3–16.8) | 15.5 (2.9) | 15.8 (14.0–18.0) | 0.058 |

| K | 4.04 (.84) | 3.80 (3.40–4.60) | 4.32 (.52) | 4.30 (4.00–4.50) | 0.240 |

| HCO3 | 27.5 (4.3) | 28.0 (25.0–30.3) | 24.9 (3.9) | 25.0 (22.0–28.0) | 0.066 |

| Na | 136.2 (5.0) | 137.0 (135.0–138.0) | 137.3 (4.3) | 138.0 (135.0–140.0) | 0.202 |

| b) | |||||

| Hemodialysis | Peritoneal dialysis | p-Value | |||

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | |

| Anemia | |||||

| Hgb | 10.6 (1.8) | 10.3 (9.4–11.7) | 9.8 (2.0) | 9.6 (8.3–11.6) | 0.150 |

| Ferritin | 319.22 (241.53) | 297.00 (184.00–391.60) | 585.03 (993.74) | 340.00 (207.00–558.00) | 0.258 |

| Tsat | 29.05 (12.84) | 27.10 (19.70–36.90) | 29.59 (15.23) | 29.00 (20.00–39.70) | 0.708 |

| Bone profile | |||||

| Ca | 2.23 (.33) | 2.20 (2.07–2.33) | 2.19 (.19) | 2.17 (2.05–2.32) | 0.754 |

| Phos | 9.82 (49.86) | 1.34 (.92–1.74) | 1.86 (.49) | 1.83 (1.67–2.11) | 0.001 |

| PTH | 60.22 (50.46) | 44.80 (27.00–69.80) | 44.05 (25.82) | 38.00 (25.00–56.00) | 0.430 |

| Vit D | 49.78 (23.39) | 47.00 (34.20–59.27) | 47.67 (15.89) | 39.00 (38.00–66.00) | 1.000 |

| Biochemical | |||||

| BUN | 17.3 (9.7) | 15.5 (10.2–23.0) | 21.7 (5.8) | 21.0 (16.2–27.0) | 0.019 |

| K | 4.14 (.84) | 4.18 (3.50–4.60) | 4.31 (.47) | 4.20 (3.90–4.60) | 0.341 |

| HCO3 | 25.5 (4.5) | 26.0 (24.0–27.9) | 23.9 (2.5) | 24.0 (23.0–25.0) | 0.116 |

| Na | 136.9 (3.0) | 137.0 (134.0–139.0) | 135.9 (3.5) | 136.0 (132.0–139.0) | 0.356 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).