1. Introduction

The inventory lot-sizing problem remains a topic of continuous interest in both scientific and industrial fields. According to Hoseini et al. [

1], the optimal lot-sizing policy in the supply chain plays an important role in industrial operations. Optimal lot sizes allow companies to reduce costs and deliver additional value to customers. Woarawichai and Naenna [

2] minimized total costs by using models for a multi-product and multi-period inventory lot-sizing problem. They also considered supplier quantity discounts and vehicle capacity. Bahroun et al. [

3] conducted a case-specific study aimed at solving a particular problem. Their approach focused on designing and implementing a solution strategy that accounted for real-world processes. This strategy needed to ensure that decision-making explored the trade-off between order size, lead times, and performance.

More recently, Randa et al. [

4] addressed a lot-sizing problem in a single-item, single-stage production system facing non-stationary stochastic demand over a finite planning horizon. They explored the complementary behavior of two classes of heuristics by examining all pairwise combinations of dynamic programming and search-based heuristics with reasonable computational times. As observed, heuristic methodologies have been employed to address these types of problems; however, theoretical approaches and detailed models are essential for further advancing the resolution of this issue.

From the perspective of system periods and a trained inventory system, Tai et al. [

5] proposed a model to determine inventory management performance, inventory stock, and existing excess stock. They accounted for demand delay and lead times, finding that a period-based model yields better results than average-based models. Different replenishment solutions can also be characterized by considering the optimal inventory control model. Chen and Rossi [

6] developed a stochastic dynamic programming model for a dynamic inventory management problem. In their model, a small cash-constrained retailer periodically purchases an item from a supplier and sells it to customers with non-stationary demand. The authors identified certain characteristics of the optimal ordering pattern.

In a recent study, Jeenanunta et al. [

7] investigated inventory optimization and presented a simulation optimization technique to determine the optimal order level for a single-product inventory system. Wisniewski and Szymanski [

8] proposed a practical methodology for decision-making in inventory replenishment aimed at reducing holding costs. They presented a case study in which the results demonstrated the validity of the proposed method.

On the other hand, entropy has garnered increasing interest across various scientific and management disciplines. In industrial engineering, the concept of entropy has been applied to cases such as decision tree analysis [

9], workforce systems [

10], logistics management [

11], business process management [

12], product life cycles [

13], price-quality relationships [

14], and the instantiation and execution of business processes [

15].

In particular, within management science/operations research, some researchers have applied entropy-based approaches to account for disorder when modeling the behavior of production systems. Jaber et al. [

16] proposed that the behavior of production systems closely resembles that of physical systems. This parallel suggests that improvements in production systems could be achieved by applying the first and second laws of thermodynamics to reduce system entropy (or disorder). To demonstrate the applicability of these laws, they used the economic order quantity (EOQ) model for production as an illustrative example.

Jaber [

17] introduced an analogy between the behavior of production systems and physical systems by applying the concept of entropy cost to estimate some hidden or difficult-to-measure costs. This work incorporated the entropy cost concept developed in Jaber et al. [

16] into the EOQ problem with permissible payment delays, based on the Goyal model [

18]. Later, Jaber et al. [

19] investigated the lot-sizing problem with learning and forgetting, incorporating the entropy cost concept into the work of Jaber and Bonney [

20], who examined the effects of learning and forgetting in production lot-sizing problems with infinite and finite planning horizons.

Castellano [

21] presented a study considering the continuous review reorder lot-sizing inventory model

under stochastic demand, accounting for a mix of backorders and lost sales. The study explored the performance of the maximum entropy principle to approximate the actual demand distribution during lead times.

You et al. [

22] investigated the lot-sizing problem with time-variable capacity in a rapidly changing production environment. In this setting, production factors such as setup costs, inventory holding costs, production capacities, and even material prices could be subject to continuous changes throughout the planning horizon. The quality of the solution was evaluated in terms of entropy, and they proposed a preliminary method to calculate system entropy. They assumed that system entropy was the product of product structure complexity, the number of products produced, and the objective cost. However, they noted that future studies could develop a more reasonable and precise method for calculating system entropy.

Although many aspects of the problem have been addressed in the studies mentioned in the previous paragraphs, we propose an innovative approach to the order lot-sizing problem. In the new theoretical framework introduced in this work, ordering options are treated as thermodynamic states, enabling a configurational mapping from the original order lot-sizing model to an effective lattice-gas model. Thus, the supply model, characterized by N orders in a planning horizon of M periods and with a unit order preparation cost , is transformed into a one-dimensional system with M distinguishable sites where N monomers will be adsorbed at chemical potential . Taking advantage of this strategy, the extensive expertise and developments associated with lattice gas models can be applied to enhance the understanding of the order lot-sizing problem. Of particular interest is the concept of configurational entropy, which, as we will demonstrate, can provide valuable insights for optimizing the selection of order lot sizes.

By integrating concepts derived from lattice-gas model theory into the decision-making process for material supply planning, we aim to provide a methodology grounded in solid scientific principles to improve order lot-sizing decisions. This scientific approach offers a structured and quantifiable way to evaluate and optimize planning processes. As a result, tangible benefits, such as cost reduction and increased efficiency in logistics and production operations, can be achieved. Moreover, by applying concepts such as entropy in a practical business context, this work contributes to the development and application of scientific knowledge in the fields of management and supply chain operations.

Over the last three decades, our research group has contributed to the study of lattice-gas models, particularly in the development of exhaustive state enumeration strategies for complex problems involving particles with a spectrum of spatially correlated states in general [

23,

24,

25]. The present study is a natural continuation of our previous work and extends the application field of lattice-gas models to the analysis of planning and material supply processes. This opens a new line of theoretical development, with implications that go beyond the scope of the present work.

The counting of states will be performed using the cluster approximation. This approach is a brute-force approximation to the system’s partition function, based on the exact calculation of configurations within small cells [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. Cluster approximation has been successfully applied in a wide range of fields, including adsorption [

26,

27,

28,

29], percolation [

30], magnetism [

31], and others.

The paper is organized as follows: the new approach linking a physical system with an optimization model is given in

Section 2. In this section, the configurational mapping is introduced, establishing a transformation rule between the parameters involved in a one-dimensional lattice gas model with lateral interactions and those appearing in a self-developed model for determining the optimal order lot size. The basis of the cluster approximation is also provided in

Section 2. The results, presented in

Section 3, include classical quantities from adsorption theory, such as adsorption isotherms and configurational entropy of the adsorbed phase, now interpreted from the perspective of an order lot-sizing model. A new strategy for managing resources (monomers on adsorption sites or orders in planning periods) in response to environmental changes (chemical potential or unit order cost) is presented and discussed. Finally, the conclusions are drawn in

Section 4.

2. Theory

2.1. Lot-sizing model: basic definitions

We study a single-item, M-period economic lot-sizing model. Let N denote the number of orders placed over the M periods, the fixed ordering cost per order, and the fixed holding cost per period for the quantity of material required for one period. The simplest strategy to meet the demand for the M periods consists of ordering the required quantity for each period at the beginning of that period (). In this case, the order is consumed within the same period, resulting in no holding cost and a total cost of .

Introducing inventory storage (

) opens up various lot-sizing strategies. Identifying the optimal strategy that minimizes total cost is particularly valuable. Each strategy begins by ordering the material required for

periods. After

periods, these supplies are depleted, and additional material for

periods is ordered. This process repeats iteratively until the

M periods are covered. Therefore, each strategy can be represented by a set of

N integers

(

), satisfying:

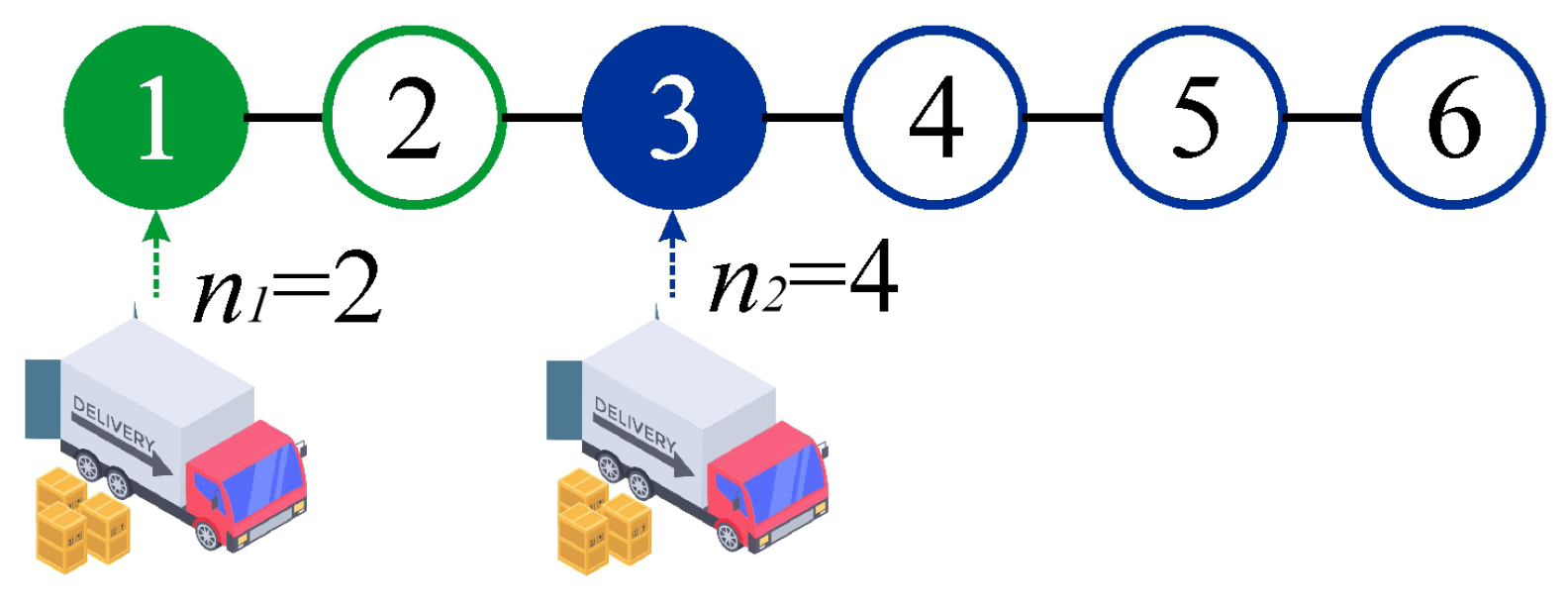

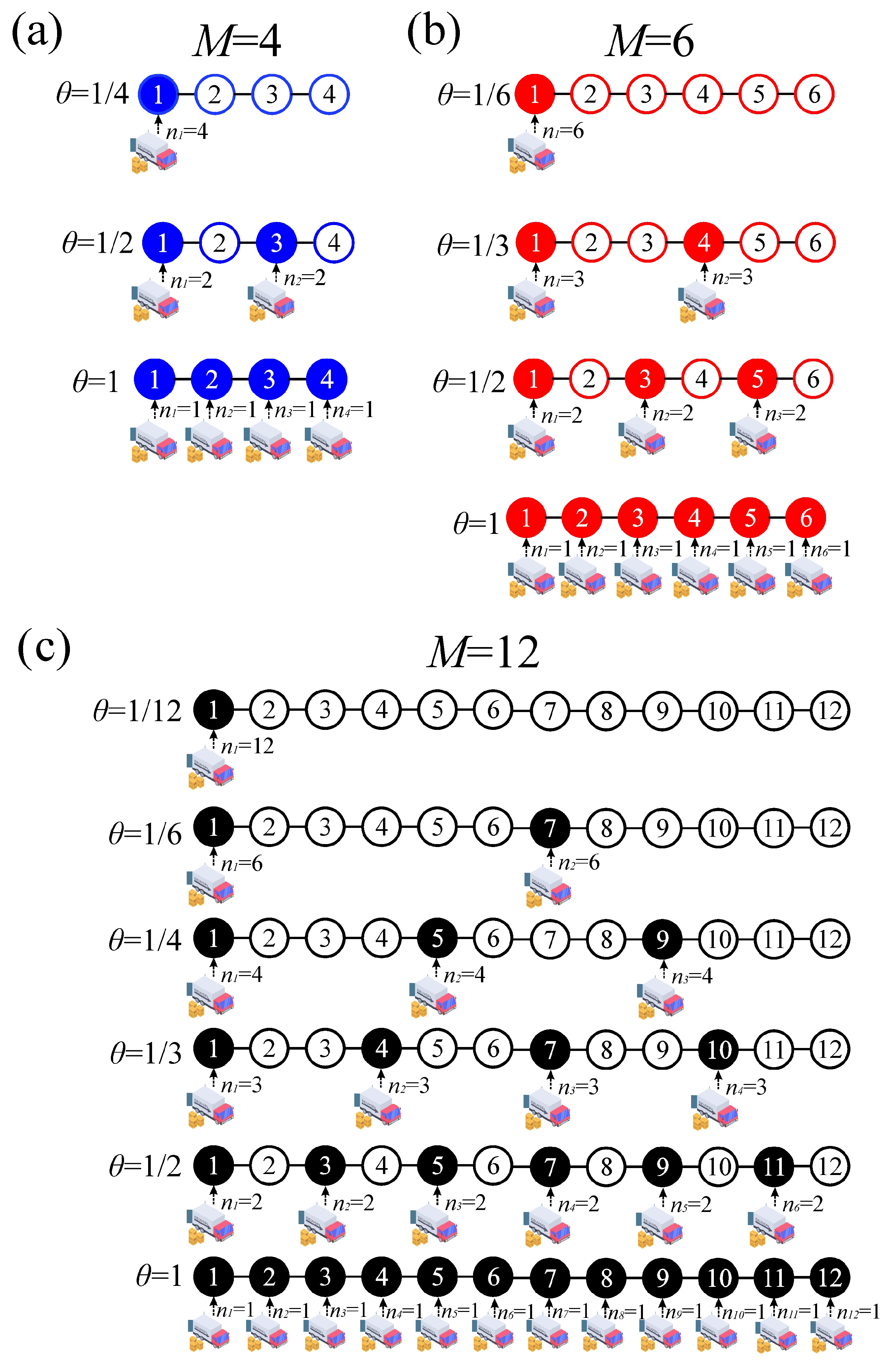

As an illustrative example, in

Figure 1 we analyze in detail a system with a planning horizon of

and two orders (

). The first order satisfies the demands for periods 1 and 2 (

), while the second order fulfills the requirements for periods 3, 4, 5, and 6 (

). The total cost associated with this strategy is given by:

On the right-hand side of Equation (

2), the first term,

, represents the total ordering cost. The second term,

, corresponds to the holding cost of the material ordered at the beginning of the first period, stored during that first period, and consumed in the second period. The third term,

, represents the holding cost of the material ordered at the beginning of the third period, stored during that period, and consumed in the fourth period. The fourth term,

, accounts for the holding cost of the material ordered at the beginning of the third period, stored during both the third and fourth periods, and consumed in the fifth period. Finally, the fifth term,

, accounts for the holding cost of the material ordered at the beginning of the third period, stored during the third, fourth and fifth periods, and consumed in the sixth period.

In general, for a strategy involving

N orders and a set

, the total cost is expressed as:

2.2. Equivalence between lot-sizing model and lattice-gas model

In the framework of the lattice-gas approximation, we assume that the surface is represented by a discrete lattice of M distinguishable sites. A lattice site represents an adsorptive potential minimum, where particles from a gas phase will be allocated upon adsorption.

The substrate is exposed to an ideal gas phase at temperature T and chemical potential . Particles can be adsorbed on the substrate with the restriction of at most one adsorbed particle per site and we consider a nearest-neighbor () interaction energy w among them.

In order to describe a system of

N particles adsorbed on

M sites, we introduce the occupancy variable

which can take the values

if the site

i is empty, and

if the site

i is occupied by a particle. Under these considerations, the adsorbed phase is characterized by the Hamiltonian:

where

is interaction energy between a particle and a lattice site; the factor of

is introduced to avoid double-counting; and “

" means that for a given site

i, the sum runs over its

sites.

Let us now return to the lot-sizing problem and consider each operating period as a site in a lattice of size

M, where a variable

indicates whether an order is received in period (site)

i. Specifically,

if no order is received in period

i, and

if an order is received. We also introduce the variable

, associated with site

i, defined as follows: if

, then

; if

, then

represents the number of periods in which no orders were received between order

i and the next period with an order, or, if order

i is the last order placed, between order

i and the end of the planning horizon. Using these newly introduced variables, the total cost function in Equation (

3) can be rewritten as follows:

As an example, let us revisit the case shown in

Figure 1 using the variables

and

. It is straightforward to deduce that

,

,

,

and

. Thus, applying Equation (

5), we obtain

consistent with the previously derived result in Equation (

2).

By comparing the Hamiltonian in Equation (

4) with the total cost function in Equation (

5), it becomes clear that an isomorphism exists between the lattice-gas model and the lot-sizing model. Specifically, the first term of the total cost function, which accounts for the ordering costs, can be identified with the adsorbate-substrate adsorption energy in the lattice-gas model. On the other hand, the second term of the total cost function, which represents holding costs, corresponds to the lateral adsorbate-adsorbate interaction energy in the lattice-gas model. The complete mapping between the lattice-gas and lot-sizing models is presented in

Table 1.

The lattice-gas model, along with its equivalent Ising model for magnetism, has been extensively studied in the literature, with its results validated across a wide range of systems [

32,

33,

34]. Our goal is to incorporate the lot-sizing model into this well-established framework, leveraging its solid and validated library of results. This not only enhances the theoretical foundation of the model presented here but also provides a framework for generalizing studies to multi-item lot-sizing problems, cases of variable material requirement per period, and other related extensions.

2.3. Cluster approximation

As we mentioned at the end of the previous section, there are proven theories for studying the Ising model and the lattice-gas model [

32,

33,

34]. One of them is called the cluster approximation (CA) [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31], and it is the approximation that will be used here.

The fundamental assumption on which CA is based is that the system can be considered as a repetition of identical small subsystems or clusters. Then, the solution of the system in the thermodynamic limit is constructed from the exact solution of a small lattice (cluster). The application of this approximation can be visualized as follows: an image of the initial lattice is constructed through its partition into a set of clusters, where each cluster is a subset of m sites. Then, with an adequate choice of the size and shape of the cluster, the log of the grand partition function per spin of the complete system can be well approximated by the log of the grand partition function of the cluster.

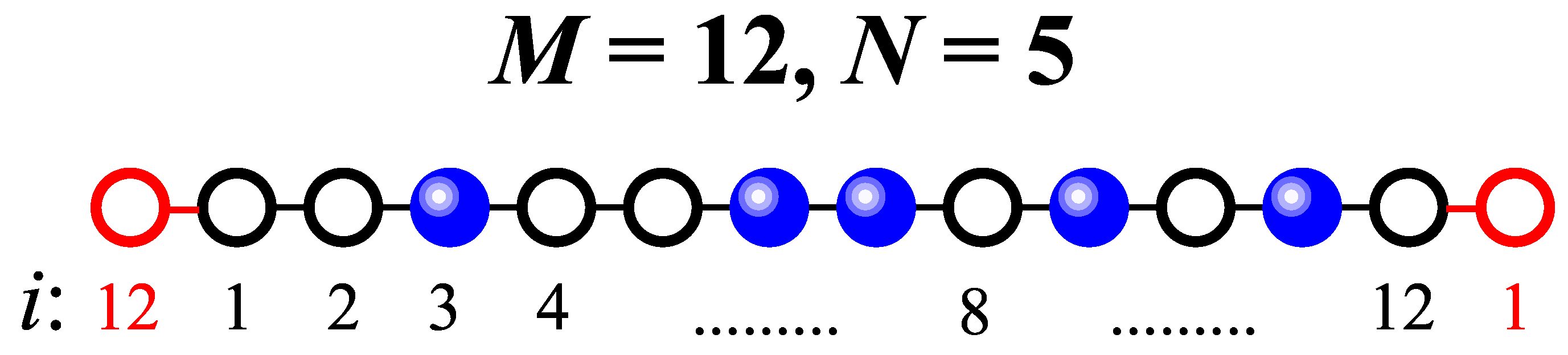

Building on the reasoning introduced in the previous paragraph, and considering a lattice-gas model of interacting particles, we assume that deposition occurs on a small one-dimensional lattice (the cluster) consisting of

M sites. Additionally, periodic boundary conditions are applied. As an example,

Figure 2 illustrates a cluster with

adsorption sites (black circles) and

adsorbed particles (blue spheres). Periodic boundary conditions are implemented by adding an extra neighboring site at each end of the lattice, as indicated by the red circles.

The grand partition function of a cluster of size

M is given by:

where

is the activity of the adsorbed species;

is the Boltzmann constant and

is the number of configurations corresponding to the

N adsorbed particles having the same energy

E (

E depends on

N and the number of interaction pairs on the cluster).

can be calculated exactly using a computer algorithm.

The adsorption isotherm and the configurational entropy per site of the adsorbed phase

s can be calculated from Equation (

7) [

33],

and

where

is called as the surface coverage in the language of the lattice-gas model. Using the mapping rules in

Table 1, the quantities defined in Equations (

8) and (

9) can be reinterpreted in terms of the lot-sizing model. This point will be discussed in detail in the next section.

Before concluding this section, we would like to highlight a couple of points. First, and as mentioned above, in a lattice gas with M distinguishable sites, between 1 and N monomers can be adsorbed. Similarly, in the supply model with a planning horizon M, between 1 and N orders can be placed. To count the possible configurations of the system, the following considerations must be taken into account.

The requirement to have raw materials available from the first execution period imposes a condition on the system’s possible configurations. In the language of the lattice-gas model, this condition implies that the first site of the system must be occupied. Thus, in the case of a single order (), where the order size includes the material required for all periods in the system, there will be only one possible configuration for this case: the first site is occupied, and the rest of the sites are empty. In the general case of N orders (with ), the count of possible configurations arises by placing the first order at the first site of the lattice (first site occupied), while the remaining orders can be distributed among the remaining periods or available sites. The total number of possible configurations is then given by .

Second, we emphasize that, in the lot-sizing problem, the system is inherently discrete, and the planning horizon typically ranges from to . This characteristic makes the cluster approximation particularly well-suited for this problem, leading to exact results.

3. Results

In this section, the cluster approximation will be applied to the lot-sizing model to analyze its behavior from a statistical mechanical perspective.

In the standard lattice-gas model, one of the most extensively studied quantities is the so-called adsorption isotherm

, which describes the coverage as a function of the chemical potential, as given in Equation (

8) [

33]. This quantity is not only of theoretical interest but also represents the most frequently measured property in experimental studies of surface physics. For this reason, we begin by analyzing the equivalent of the adsorption isotherm in the context of the lot-sizing problem. In this case, following historical precedent, we examine

, where

is a characteristic parameter in lot-sizing theory [

35].

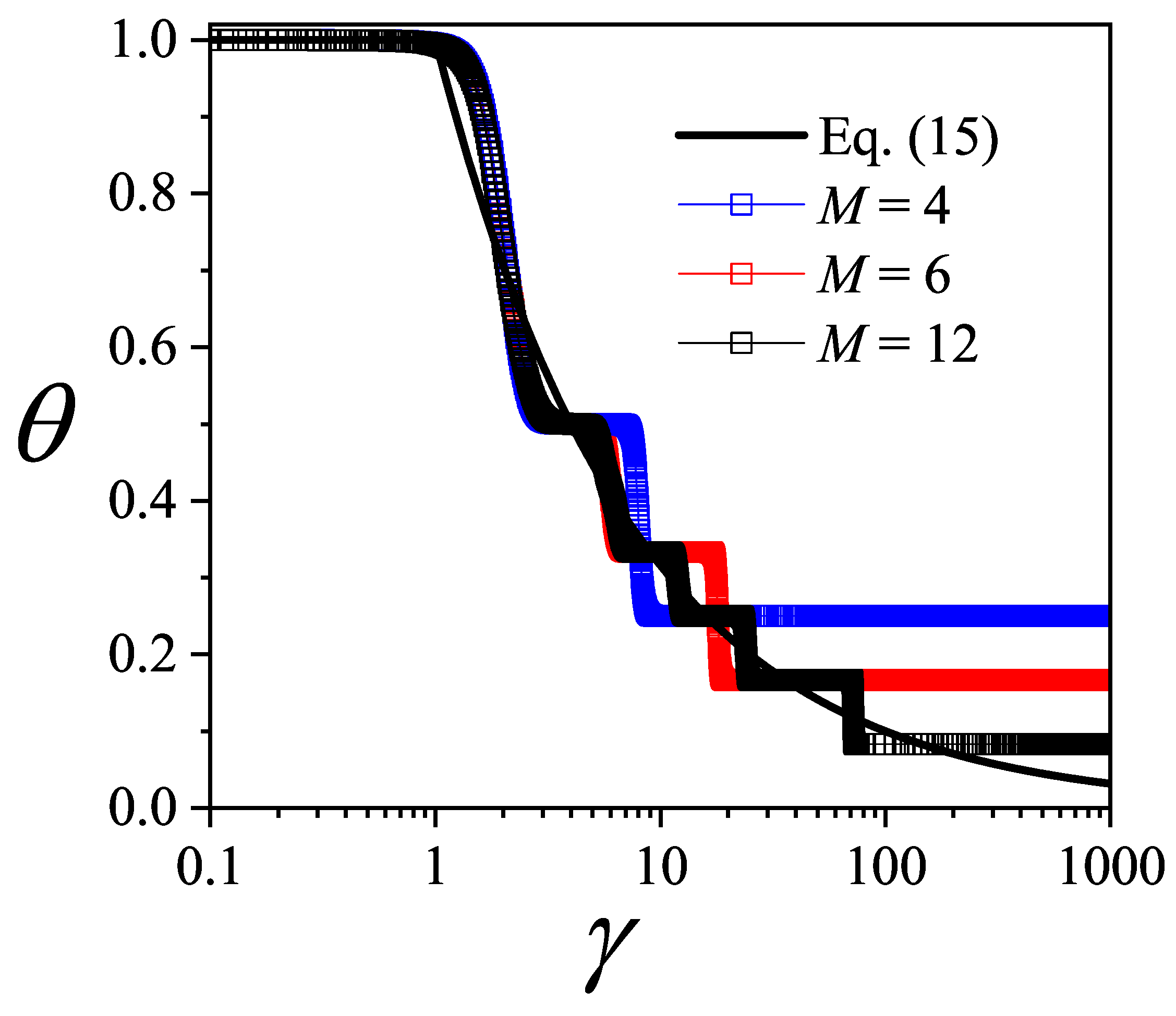

In

Figure 3,

is plotted as a function of

(in log scale) for three different values of

M: 4 (blue squares); 6 (red squares); and 12 (black squares). Symbols joined by lines represent analytical CA results. In our calculations, we set

(in arb. units) and vary

.

The overall behavior of the curves in

Figure 3 can be explained as follows: at very low values of

, the ordering cost is negligible compared to the holding cost, which leads to the maximum number of orders (

) and, accordingly,

. This trend persists until approximately

, where the ordering cost becomes significant, causing the number of orders to decrease. In the opposite limit, when

is very large, the ordering cost is significantly higher than the holding cost. As a result, the number of orders reaches its minimum (

), leading to

for

. As observed in the different curves, the intermediate regime of

values is characterized by the presence of plateaus in the function

. We will refer to these singularities below.

The plateaus observed in

Figure 3 have precedents in classical problems of surface physical chemistry [

36,

37]. Specifically, in the case of a one-dimensional lattice-gas model with repulsively interacting adsorbates, the resulting adsorption isotherms are characterized by the presence of plateaus corresponding to the formation of distinct adsorbate structures [

36,

37]. These structures depend on the shape of the adsorbate and the characteristics of lateral interactions, such as their range, additivity, and other factors.

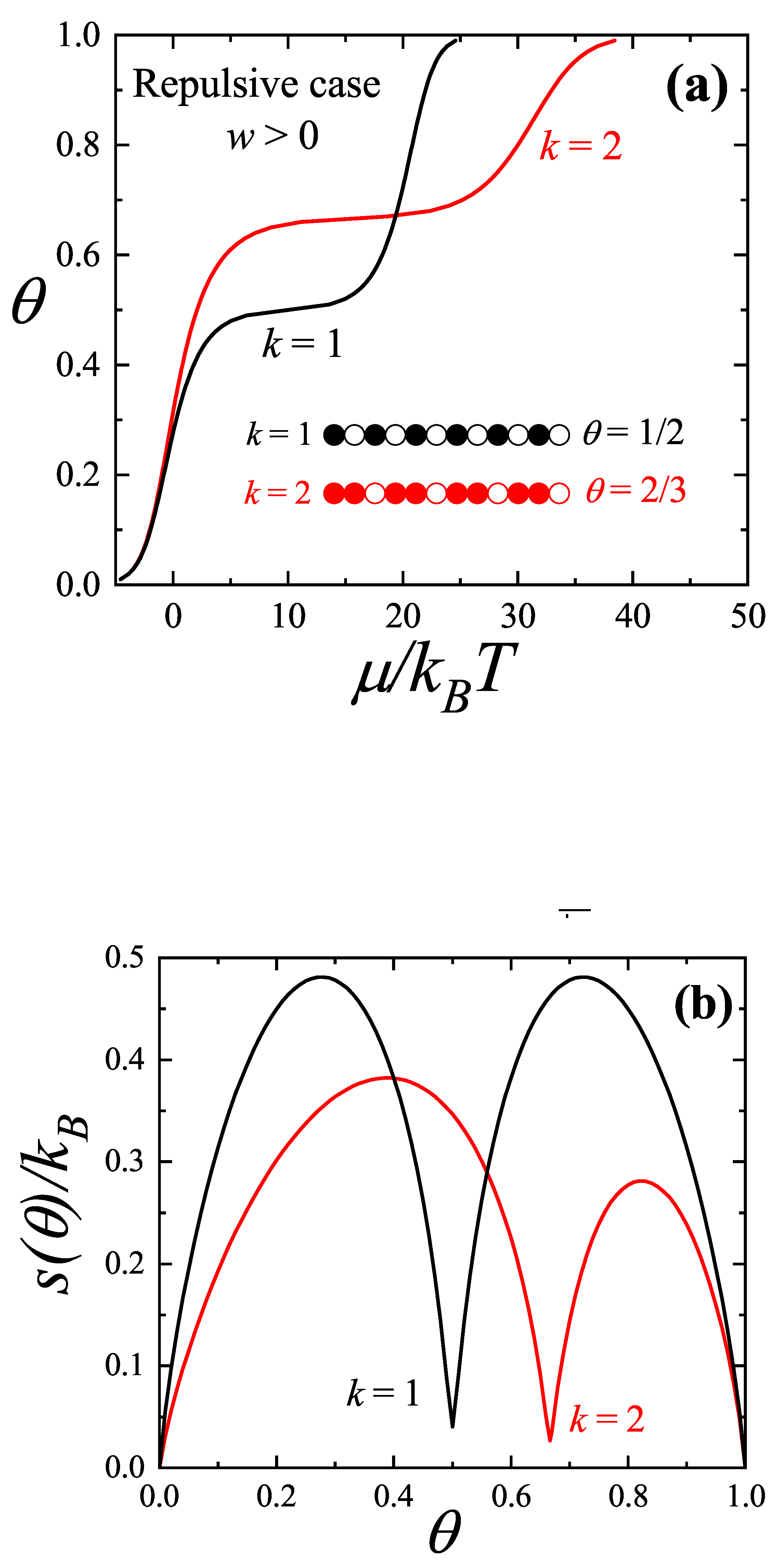

As an illustrative example,

Figure 4(a) depicts the adsorption isotherms of repulsive monomers and dimers in a one-dimensional system at low temperature regime, highlighting the different phases that emerge. The problem of

N adsorbed

k-mers on a one-dimensional lattice with

M sites, including a nearest-neighbor interaction energy

w between the ends of adjacent

k-mers, has been exactly solved [

36]. As shown in Ref. [

36]. the coverage dependence of the chemical potential and the entropy per site,

s, can be expressed as follows:

where

is given by

and

.

The curves in

Figure 4 were obtained from Equations (

10) and (

11) with

. In the case of the adsorption isotherm for monomers (

, black line in

Figure 4(a)), particles avoiding configurations with repulsive nearest neighbors order in a structure of alternating adatoms separated by an empty site at

. The width of the step is directly proportional to the energy per particle necessary to alter such an ordered structure. As the size of adparticles increases, the step shifts to higher coverages. Based on analogous arguments to the ones given for monomers, it is straightforward that steps are located at

for dimers (

, red line) in

Figure 4(a)).

On the other hand, the configurational entropy curves of the adsorbed phase (see

Figure 4(b)) exhibit local minima at

for monomers and

for dimers. These entropy minima originate from the specific structural arrangements associated with the adsorption isotherms, as discussed above and illustrated in the inset of

Figure 4(a).

Let us now return to the curves shown in

Figure 3 and examine the plateaus that appear, along with their connection to the formation of ordered structures in the equivalent lattice-gas model. We begin with the case of

. In addition to the trivial cases observed at

(

) and

(

), a distinct plateau is observed at intermediate coverage, specifically at

(

). This plateau corresponds to the ordered configuration illustrated in

Figure 5(a). For

, no other value of

N yields a configuration with evenly spaced adsorbates. In the case of

, intermediate plateaus emerge at

(

) and

(

), as shown in

Figure 5(b). Finally, for

, plateaus are observed at

(

),

(

),

(

), and

(

). Representative snapshots of the corresponding ordered structures are presented in

Figure 5(c).

In a recent study by our group [

35], an optimization model for the lot-sizing problem was introduced based on a physical system approach. By establishing that the material supply problem is isomorphic to a one-dimensional mechanical system of point particles connected by elastic elements, an exact solution was obtained, and the cost optimization conditions emerged naturally. The results indicate that, for a given

N, the optimal strategy to minimize the total cost involves placing the

N orders at equal intervals. In the context of the lattice-gas model, this prediction aligns with the structures derived from the isotherms in

Figure 3.

To further support the arguments presented in the previous paragraph, we computed the adsorption energy of the adsorbed layer in the lattice-gas model for each coverage where plateaus form. These energies are equivalent to the total cost in the terminology of the lot-sizing model. For simplicity, we restrict our analysis to the energy component that accounts only for lateral interactions (holding costs in the lot-sizing model). The total cost and holding cost differ only by an additive term equal to

. The results are reported in

Table 2. The values in the table, obtained using CA from the equivalent lattice-gas model, match exactly with the exact values derived from the equation:

where

represents the minimum holding cost for a given

(

N). Equation (

13) was obtained in Ref. [

35] considering equally spaced orders.

In Ref. [

35], the optimal number of orders,

, for which the total cost reaches a minimum was exactly calculated as a function of

:

By normalizing with the planning horizon

M, we obtain:

The function

(Equation (

15)) is shown in

Figure 3 as a black solid line. As can be observed, the curves obtained for discrete values of

M converge to the exact solution given by Equation (

15) in the limit of

. This result indicates that the curves presented in

Figure 3 provide the optimal value of

N for each

, thus completing the interpretation of the function

derived from the thermodynamic analogy with the lattice-gas model.

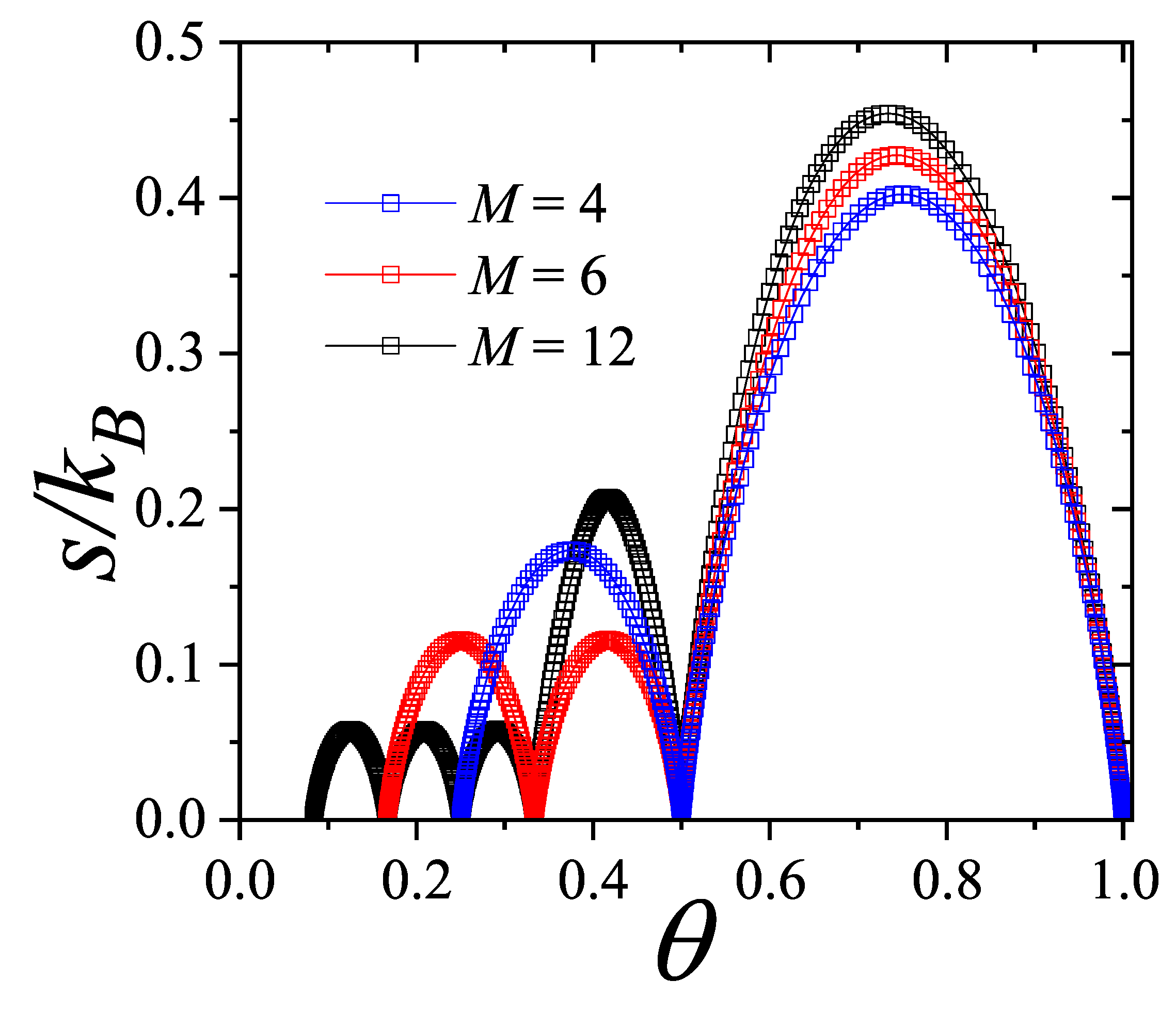

The structures discussed in terms of the function

can also be analyzed from an entropy perspective. To this end, using CA theory, we computed the entropy as a function of coverage (Equation (

9)) for the same cases reported in

Figure 3. The results are shown in

Figure 6, with the same symbology as in

Figure 3. The pronounced minima observed in the entropy curves are consistent with the formation of the ordered structures discussed earlier, corroborating the arguments presented in Ref. [

35]. These findings further support the conclusion that, for a fixed

N, the most cost-effective strategy consists of distributing the

N orders at equal intervals. In other words, the structures emerging from the plateaus of the isotherms, or equivalently, from the minima of the entropy per site (see

Figure 5), arise from the minimization criteria imposed by thermodynamics, and correspond to the optimal purchasing and storage strategies in the associated lot-sizing model [

35].

The results presented in this section demonstrate that mapping the lot-sizing problem onto a lattice-gas model, in conjunction with the well-established cluster approximation, offers a powerful and consistent framework for tackling supply-related challenges. More importantly, this approach introduces a completely novel perspective on the problem. The implications are profound: it invites us to reinterpret purchasing and storage strategies as thermodynamic states of a physical system. This innovative viewpoint brings into play fundamental physical concepts, such as energy and entropy, that have not been previously considered in this class of models. By framing the problem in this way, we open the door to a new line of research, potentially enabling the extension of this framework to more complex and realistic supply chain scenarios. This promising direction will be explored further in the following section.

4. Conclusions

In this work, we have introduced a novel framework for analyzing the classical lot-sizing problem by mapping it onto a lattice-gas model. This mapping allows us to leverage the formalism of statistical mechanics, traditionally used to study thermodynamic systems, in the context of supply chain optimization.

The core of our approach lies in characterizing the state of each period within the planning horizon using a discrete variable , where indicates no order is received in period i, and indicates that an order is placed. Building on this representation, we demonstrated that it is possible to construct a Hamiltonian for the lot-sizing problem and establish an isomorphism with well-known models in statistical mechanics, such as the lattice-gas model of particles adsorbed on a surface and the Ising model of spins on a lattice. In this study, we focused primarily on the lattice-gas formulation, given our group’s long-standing expertise in adsorption phenomena within this modeling framework.

This creative and interdisciplinary perspective enables the reinterpretation of purchasing strategies as thermodynamic states, from which thermodynamic quantities such as energy and entropy can be derived—quantities that, until now, were absent from the vocabulary of classical supply models. The relevance of these quantities was validated by comparing the predictions of the lattice-gas model with the exact results recently reported in Ref. [

35].

From an applied standpoint, our results show that the theoretical framework developed over decades to study adsorption (or magnetism) using lattice-gas-type models provides a simple yet powerful tool for identifying optimal strategies in supply planning problems. This contribution is particularly valuable, as it brings to the field of supply chain management a rich set of analytical tools developed within the realm of statistical physics. As a concrete example, we showed that the use of CA theory not only highlights the structure of optimal strategies but also proves particularly effective given the discrete nature of the planning horizon M.

From a theoretical perspective, we found that optimal supply strategies naturally emerge from the minimization of a free energy function, mirroring the principle by which equilibrium states are determined in thermodynamic systems. We believe this insight has significant implications and may pave the way for a new line of research at the interface between statistical physics and supply chain optimization.

Future work will focus on extending this theoretical framework to more complex settings, including multi-item lot-sizing problems and scenarios with time-dependent demand. In the former case, the problem will be mapped onto a multicomponent lattice-gas model, with each species representing a distinct product. In the latter, we will consider lattice-gas models with non-additive interactions to account for the temporal variability in material requirements.