Submitted:

22 May 2025

Posted:

24 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Collection

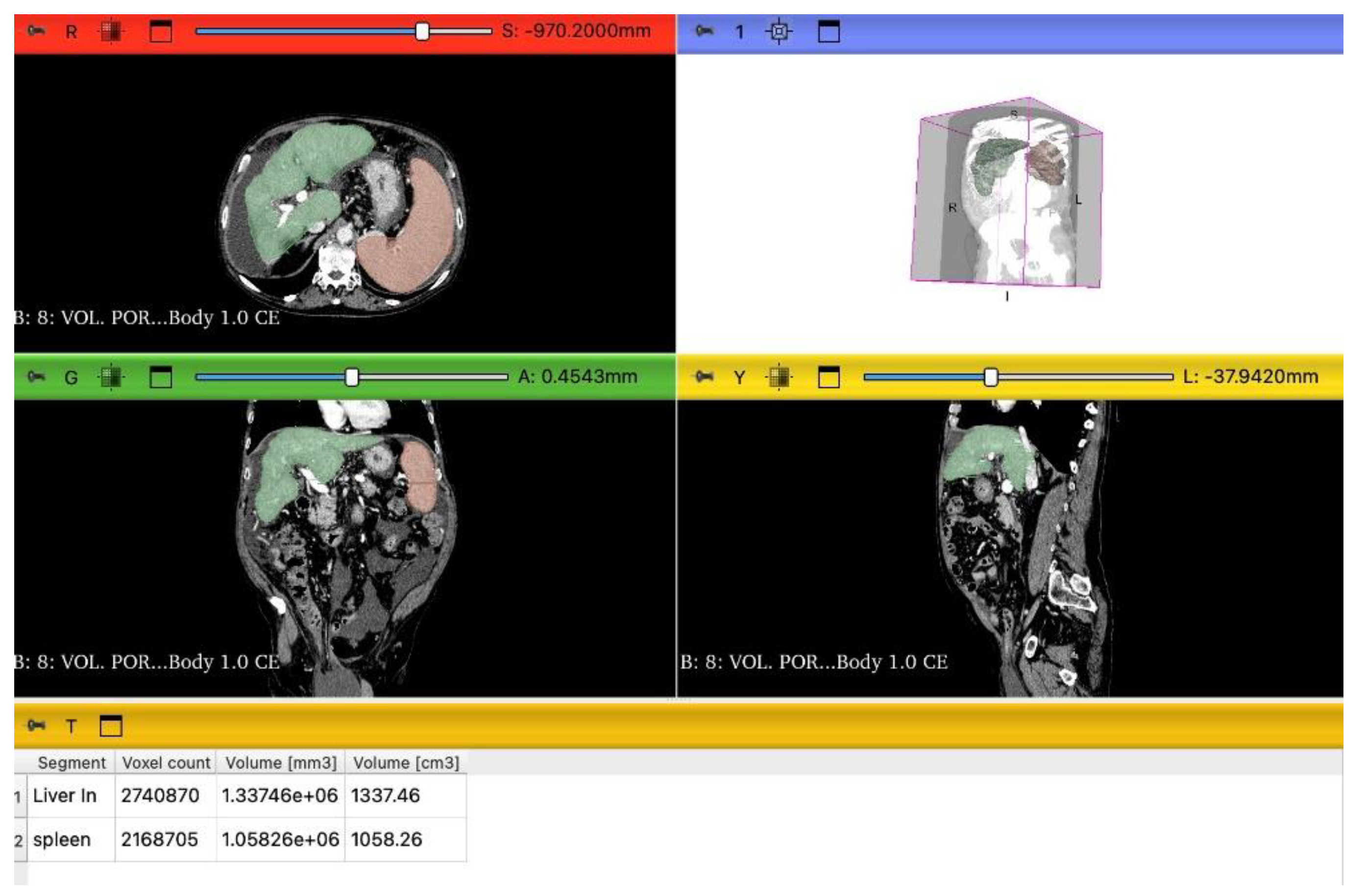

2.3. LSVR and LVCA Calculation

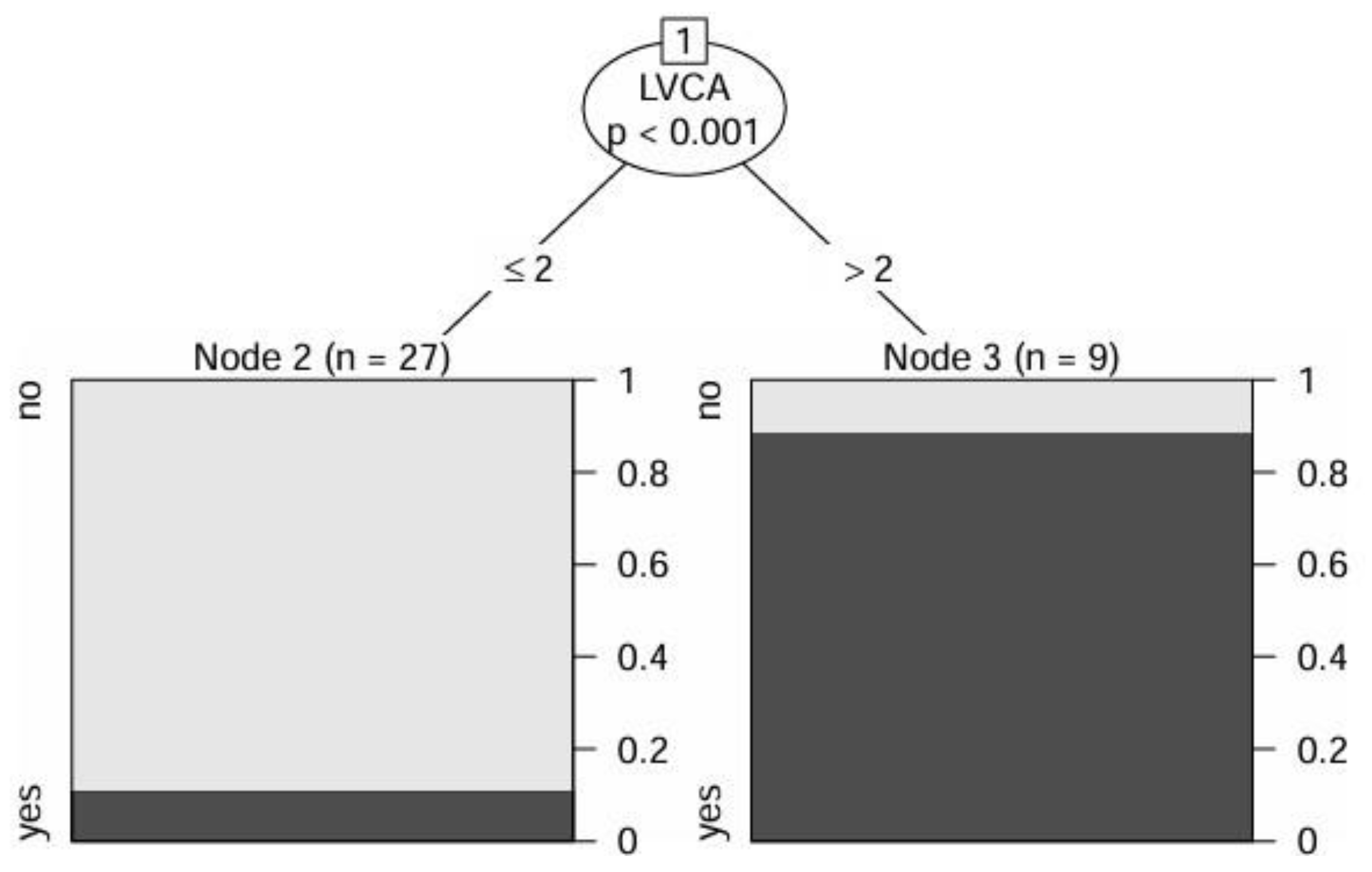

2.4. Statistical Analysis

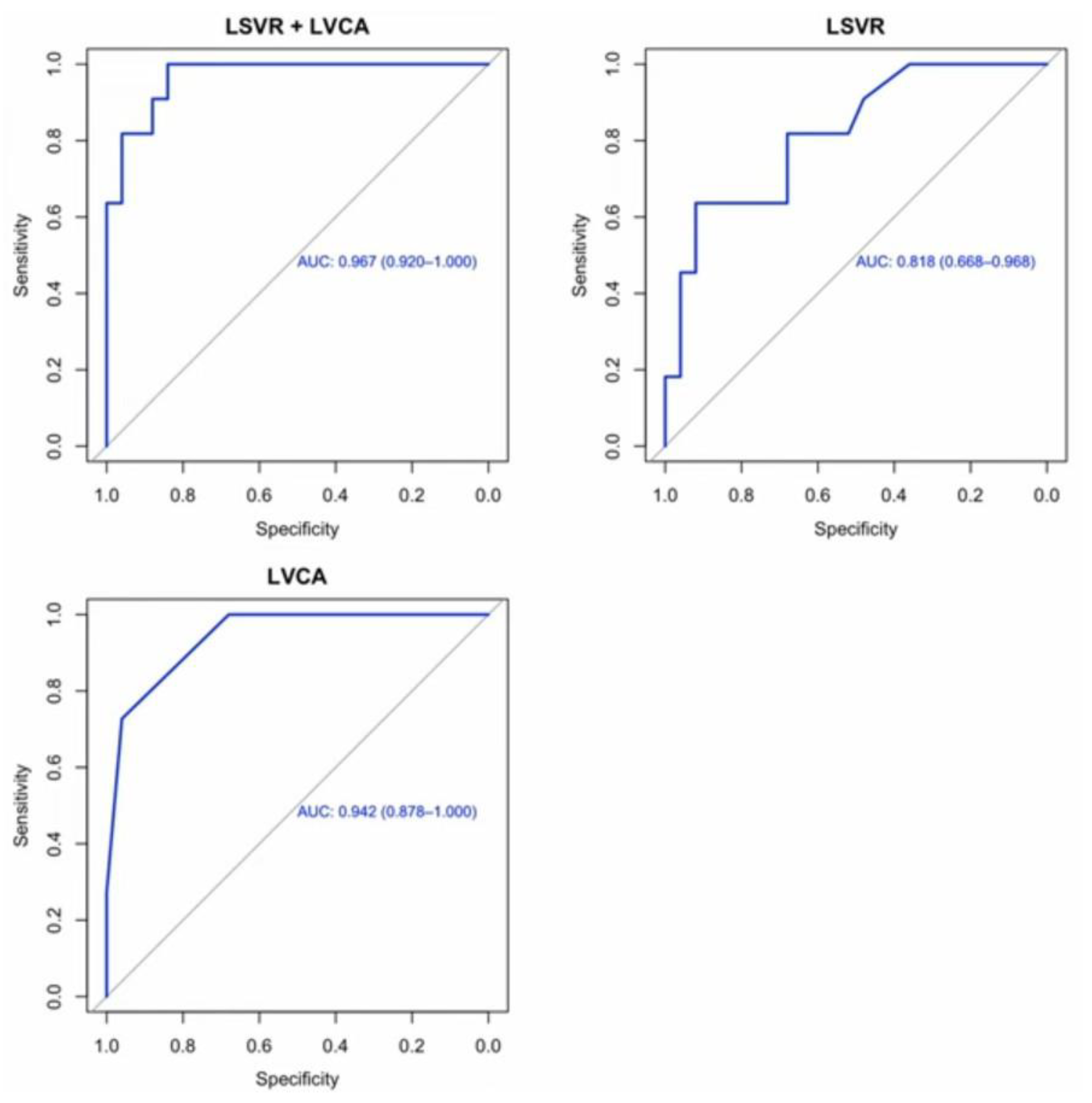

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFP | Alpha-fetoprotein |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| ALP | Alkaline Phosphatase |

| ALT | Alanine Aminotransferase |

| aPTT | Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time |

| AST | Aspartate Aminotransferase |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| GGT | Gamma-glutamyl Transferase |

| HBV | Hepatitis B Virus |

| HCC | Hepatocellular Carcinoma |

| HCV | Hepatitis C Virus |

| INR | International Normalized Ratio |

| LC | Liver Cirrhosis |

| LDL | Low-Density Lipoprotein |

| LSVR | Liver Segmental Volume Ratio |

| LVCA | Liver Vein to Cava Attenuation |

| MELD | Model for End-Stage Liver Disease |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| PT | Prothrombin Time |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

References

- Scarlata, G.G.M. , Cicino, C., Spagnuolo, R., Marascio, N., Quirino, A., Matera, G., Dumitrașcu, D.L., Luzza, F., Abenavoli, L. Impact of diet and gut microbiota changes in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatoma Res 2024, 10, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Koshy, A. Evolving Global Etiology of Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC): Insights and Trends for 2024. J Clin Exp Hepatol 2025, 15, 102406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.D. , Hainaut, P., Gores, G.J., Amadou, A., Plymoth, A., Roberts, L.R. A global view of hepatocellular carcinoma: trends, risk, prevention and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019, 16, 589–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phoolchund, A.G.S. , Khakoo, S.I. MASLD and the Development of HCC: Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Challenges. Cancers (Basel) 2024, 16, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, H. , Zhao, Y., He, C., Qian, L., Huang, P. Ultrasonography of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: From Diagnosis to Prognosis. J Clin Transl Hepatol 2024, 12, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif-Tiwari, H. , Kalb, B., Chundru, S., Sharma, P., Costello, J., Guessner, R.W., Martin, D.R. MRI of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update of current practices. Diagn Interv Radiol 2014, 20, 209–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada, M.; Aoki, R.; Nakazawa, Y.; Tago, K.; Numata, K. CT and MR Imaging of Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Liver Cirrhosis. Gastroenterol. Insights 2024, 15, 976–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samban, S.S. , Hari, A., Nair, B., Kumar, A.R., Meyer, B.S., Valsan, A., Vijayakurup, V., Nath, L.R. An Insight Into the Role of Alpha-Fetoprotein (AFP) in the Development and Progression of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Mol Biotechnol 2024, 66, 2697–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. , Jiang, W., Li, X., Zhao, H., Wang, S. The Diagnostic Performance of AFP, AFP-L3, DCP, CA199, and Their Combination for Primary Liver Cancer. J Hepatocell Carcinoma 2025, 12, 513–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosser, S. , Tümen, D., Volz, B., Neumeyer, K., Egler, N., Kunst, C., Tews, H.C., Schmid, S., Kandulski, A., Müller, M., et al. HCC biomarkers - state of the old and outlook to future promising biomarkers and their potential in everyday clinical practice. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 1016952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarlata, G.G.M. , Ismaiel, A., Gambardella, M.L., Leucuta, D.C., Luzza, F., Dumitrascu, D.L., Abenavoli, L. Use of Non-Invasive Biomarkers and Clinical Scores to Predict the Complications of Liver Cirrhosis: A Bicentric Experience. Medicina (Kaunas) 2024, 60, 1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismaiel, A.; Katell, E.; Leucuta, D.C.; Popa, S.L.; Catana, C.S.; Dumitrascu, D.L.; Surdea-Blaga, T. The Impact of Non-Invasive Scores and Hemogram-Derived Ratios in Differentiating Chronic Liver Disease from Cirrhosis. J. Clin. Med 2025, 14, 3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. , Wei, C. Advances in the early diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Genes Dis 2020, 7, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, S.H. , Hong, S.B., Han, K., Seo, N., Choi, J.Y., Lee, J.H., Park, S., Lim, Y.S., Kim, D.Y., Kim, S.Y., et al. A New Reporting System for Diagnosis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Chronic Hepatitis B With Clinical and Gadoxetic Acid-Enhanced MRI Features. J Magn Reson Imaging 2022, 55, 1877–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshiji, H. , Nagoshi S., Akahane T., Asaoka Y., Ueno Y., Ogawa K., Kawaguchi T., Kurosaki M., Sakaida I., Shimizu M., et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for Liver Cirrhosis 2020. J. Gastroenterol 2021, 56, 593–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2025, 82, 315–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Franchis, R. , Bosch, J., Garcia-Tsao G., Reiberger T., Ripoll C., Abraldes J.G., Albillos A., Baiges A., Bajaj J., Bañares R., et al. Baveno VII—Renewing consensus in portal hypertension. J. Hepatol 2022, 76, 959–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajiri, T. , Yoshida, H., Obara, K., Onji, M., Kage, M., Kitano, S., Kokudo, N., Kokubu, S., Sakaida, I., Sata M., et al. General Rules for Recording Endoscopic Findings of Esophagogastric Varices. 2nd ed. Volume 22. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2010. pp. 1–9.

- Villa, E. , Bianchini M., Blasi A., Denys A., Giannini E.G., de Gottardi A., Lisman T., de Raucourt E., Ripoll C., Rautou P.E. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on prevention and management of bleeding and thrombosis in patients with cirrhosis. J. Hepatol 2022, 76, 1151–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reig, M. , Forner, A., Rimola, J., Ferrer-Fàbrega, J., Burrel, M., Garcia-Criado, Á., Kelley, R.K., Galle, P.R., Mazzaferro, V., Salem, R., et al. BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: The 2022 update. J Hepatol 2022, 76, 681–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y. , Qi X., Guo X. Child-Pugh Versus MELD Score for the Assessment of Prognosis in Liver Cirrhosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Medicine 2016, 95, e2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon JH, Lee SS, Yoon JS, Suk HI, Sung YS, Kim HS, Lee CM, Kim KM, Lee SJ, Kim SY. Liver-to-Spleen Volume Ratio Automatically Measured on CT Predicts Decompensation in Patients with B Viral Compensated Cirrhosis. Korean J Radiol 2021, 22, 1985–1995. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obmann VC, Marx C, Hrycyk J, Berzigotti A, Ebner L, Mertineit N, Gräni C, Heverhagen JT, Christe A, Huber AT. Liver segmental volume and attenuation ratio (LSVAR) on portal venous CT scans improves the detection of clinically significant liver fibrosis compared to liver segmental volume ratio (LSVR). Abdom Radiol (NY) 2021, 46, 1912–1921.

- Hothorn, T. , Hornik, K, Zeileis, A. Unbiased recursive partitioning: A conditional inference framework. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. 2006, 15, 651–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hothorn, T. , Hornik, K., Strobl, C., Zeileis, A. party: A Laboratory for Recursive Partytioning. R package version 1.3-13; 2023. Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=party.

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; 2024. Available from: https://www.R-project.org/.

- Scarpellini, E. , Scarlata, G.G.M., Santori, V., Scarcella, M., Kobyliak, N., Abenavoli, L. Gut Microbiota, Deranged Immunity, and Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W. , Wei, C. Advances in the early diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Genes Dis 2020, 7, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asrani, S.K. , Devarbhavi, H., Eaton, J., Kamath, P.S. Burden of liver diseases in the world. J Hepatol 2019, 70, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M. , Koenig, A.B., Abdelatif, D., Fazel, Y., Henry, L., Wymer, M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology 2016, 64, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.J. Hepatitis B virus infection and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2011, 17, 4853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, A.M. , Rezaee-Zavareh, M.S., Hwang, S.Y., Kim, N., Adetyan, H., Yalda, T., Chen, P.J., Koltsova, E.K., Yang, J.D. Novel Biomarkers for Early Detection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Diagnostics (Basel) 2024, 14, 2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oura, K.; Morishita, A.; Tani, J.; Masaki, T. Tumor Immune Microenvironment and Immunosuppressive Therapy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2021, 22, 5801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, G.Q. , Jiao, Y., Meng, G.X., Dong, Z.R., Li, T. The relationship between the serum lipid profile and hepatocellular carcinoma in east Asian population: A mendelian randomization study. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, T. , Long, G., Mi, X., Su, W., Mo, L., Zhou, L. Splenic Volume, an Easy-To-Use Predictor of HCC Late Recurrence for HCC Patients After Hepatectomy. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 876668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takase, K. , Ueno, T., Matsuki, K., Todo, M., Iwasaki, S., Deguchi, K., Masahata, K., Nomura, M., Watanabe, M., Kamiyama, M., et al. Liver-Spleen Volume Ratio as a Predictor of Native Liver Survival in Patients with Biliary Atresia. Transplant Proc 2023, 55, 872–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Cristóbal, M. , Clemente-Sánchez, A., Ramón, E., Téllez, L., Canales, E., Ortega-Lobete, O., Velilla-Aparicio, E., Catalina, M.V., Ibáñez-Samaniego, L., Alonso, S., et al. CT-derived liver and spleen volume accurately diagnose clinically significant portal hypertension in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. JHEP Rep 2022, 5, 100645. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shah, S. , Shukla, A., Paunipagar, B. Radiological features of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Exp Hepatol 2014, 4, S63–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, R.E. , Yu, L. Safety Considerations in MRI and CT. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2023, 29, 27–53. [Google Scholar]

- Najjar, R. Redefining Radiology: A Review of Artificial Intelligence Integration in Medical Imaging. Diagnostics (Basel) 2023, 13, 2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| LC+HCC (n=36) |

|

|---|---|

| Demographic data | |

| Age (years), mean±SD | 62±11 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 28 (78) |

| Clinical data, n (%) | |

| Alcoholic | 17 (47) |

| Autoimmune | 1 (3) |

| Cryptogenic | 3 (8) |

| Dysmetabolic | 8 (22) |

| Infective | 8 (22) |

| HBV-related | 4 (11) |

| HCV-related | 4 (11) |

| Mixed | 1 (3) |

| Presence of complications | 33 (92) |

| Number of complications (mean±SD) | 2±1 |

| Ascites | 26 (72) |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 19 (53) |

| Esophageal and gastric varices | 5 (14) |

| Esophageal varices F1 | 12 (33) |

| Esophageal varices F2 | 7 (19) |

| Esophageal varices F3 | 1 (3) |

| Gastric varices | 4 (11) |

| Hepato-renal syndrome | 5 (14) |

| Portal hypertensive gastropathy | 17 (47) |

| Portal vein ectasia | 4 (11) |

| Portal vein thrombosis | 3 (8) |

| Splenomegaly | 22 (61) |

| Monofocal HCC | 10 (28) |

| Multifocal HCC | 1 (3) |

| Size of the nodules (cm), mean±SD | 4±2 |

| Laboratory parameters and scores, mean±SD | |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4±0.5 |

| ALP (UI/L) | 114±54 |

| AST (UI/L) | 48±44 |

| ALT (UI/L) | 38±61 |

| GGT (UI/L) | 88±86 |

| AFP (ng/mL) | 232±1356 |

| Platelets (103/μL) | 125±66 |

| PT (s) | 14±3 |

| aPTT (s) | 36±10 |

| INR | 1.3±0.4 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 269±95 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1±0.3 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 4±0.5 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 138±4 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.4±0.9 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.7±0.5 |

| Neutrophils (109/L) | 3±1.5 |

| Lymphocytes (109/L) | 1±0.5 |

| Leucocytes (109/L) | 5±2 |

| Monocytes (109/L) | 0.4±0.2 |

| Basophils (109/L) | 0.02±0.01 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 109±64 |

| Glycemia (mg/dL) | 120±42 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 132±38 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 42±17 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 76±32 |

| Child-Pugh A, n (%) | 12 (33) |

| Child-Pugh B, n (%) | 21 (58) |

| Child-Pugh C, n (%) | 3 (8) |

| MELD score, | 12±4 |

| MELD Na | 11±6 |

| Liver volume (cm3) | 1500±335 |

| Spleen volume (cm3) | 685±437 |

| LSVR | 0.5±0.3 |

| Liver right lobe diameter (cm) | 15±1.5 |

| Spleen diameter (cm) | 14±3 |

| LVCA | 2±1 |

| LC (n=25) |

HCC (n=11) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | |||

| Age (years), mean±SD | 63±12 | 61±10 | 0.535 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 18 (72) | 7 (64) | 0.209 |

| Clinical data, n (%) | |||

| Alcoholic | 12 (48) | 5 (45) | 0.888 |

| Autoimmune | 1 (4) | 0 | 0.501 |

| Cryptogenic | 2 (8) | 1 (9) | 0.913 |

| Dysmetabolic | 7 (28) | 1 (9) | 0.209 |

| Infective | 4 (16) | 4 (36) | 0.176 |

| HBV-related | 1 (4) | 3 (26) | 0.041 |

| HCV-related | 3 (12) | 1 (9) | 0.798 |

| Mixed | 1 (4) | 0 | 0.501 |

| Presence of complications | 22 (88) | 11 (100) | 0.230 |

| Number of complications (mean±SD) | 2±1 | 3±1 | 0.068 |

| Ascites | 17 (68) | 9 (81) | 0.394 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 13 (52) | 6 (54) | 0.888 |

| Esophageal and gastric varices | 1 (4) | 4 (36) | 0.010 |

| Esophageal varices F1 | 10 (40) | 2 (18) | 0.201 |

| Esophageal varices F2 | 2 (8) | 5 (45) | 0.009 |

| Esophageal varices F3 | 1 (4) | 0 | 0.501 |

| Gastric varices | 1 (4) | 3 (27) | 0.041 |

| Hepato-renal syndrome | 3 (12) | 2 (18) | 0.621 |

| Portal hypertensive gastropathy | 11 (44) | 6 (54) | 0.559 |

| Portal vein ectasia | 8 (32) | 4 (36) | 0.798 |

| Portal vein thrombosis | 1 (4) | 2 (18) | 0.156 |

| Splenomegaly | 16 (64) | 6 (54) | 0.592 |

| Laboratory parameters and scores), mean±SD | |||

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.8±0.4 | 3.6±0.7 | 0.239 |

| ALP (UI/L) | 111±59 | 121±41 | 0.611 |

| AST (UI/L) | 48±51 | 47±23 | 0.372 |

| ALT (UI/L) | 42±73 | 29±16 | 0.986 |

| GGT (UI/L) | 87±97 | 90±61 | 0.410 |

| AFP (ng/mL) | 4±3 | 750±2452 | 0.013 |

| Platelets (103/μL) | 140±71 | 91±40 | 0.054 |

| PT (s) | 14±3 | 15±3 | 0.249 |

| aPTT (s) | 35±9 | 38±11 | 0.352 |

| INR | 1.3±0.5 | 1.4±0.2 | 0.126 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 282±98 | 238±85 | 0.223 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.9±0.3 | 1±0.4 | 0.409 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 4±0.6 | 4±05 | 0.334 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 138±4 | 137±3 | 0.277 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.4±1 | 1.5±1 | 0.503 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.6±0.5 | 0.7±0.4 | 0.488 |

| Neutrophils (109/L) | 4±1.3 | 3±1.8 | 0.106 |

| Lymphocytes (109/L) | 1.3±0.5 | 0.9±0.5 | 0.030 |

| Leucocytes (109/L) | 6±1.6 | 4±1.9 | 0.024 |

| Monocytes (109/L) | 0.4±0.2 | 0.3±0.1 | 0.026 |

| Basophils (109/L) | 0.02±0.01 | 0.01±0.01 | 0.165 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 121±74 | 83±21 | 0.057 |

| Glycemia (mg/dL) | 113±29 | 134±62 | 0.594 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 140±40 | 113±23 | 0.043 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 44±18 | 38±17 | 0.341 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 84±32 | 60±26 | 0.035 |

| Child-Pugh A, n (%) | 10 (40) | 2 (18) | 0.435 |

| Child-Pugh B, n (%) | 13 (52) | 8 (72) | |

| Child-Pugh C, n (%) | 2 (8) | 1 (9) | |

| MELD score, | 11±4 | 13±4 | 0.204 |

| MELD Na | 10±6 | 13±5 | 0.133 |

| Liver volume (cm3) | 1461±337 | 1585±328 | 0.314 |

| Spleen volume (cm3) | 507±211 | 1088±552 | <0.001 |

| LSVR | 0.4±0.2 | 0.7±0.3 | <0.001 |

| Liver right lobe diameter (cm) | 15±1.5 | 15±1.5 | 0.694 |

| Spleen diameter (cm) | 12±2 | 17±3 | <0.001 |

| LVCA | 1.3±0.5 | 3±0.8 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).