Submitted:

22 May 2025

Posted:

23 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

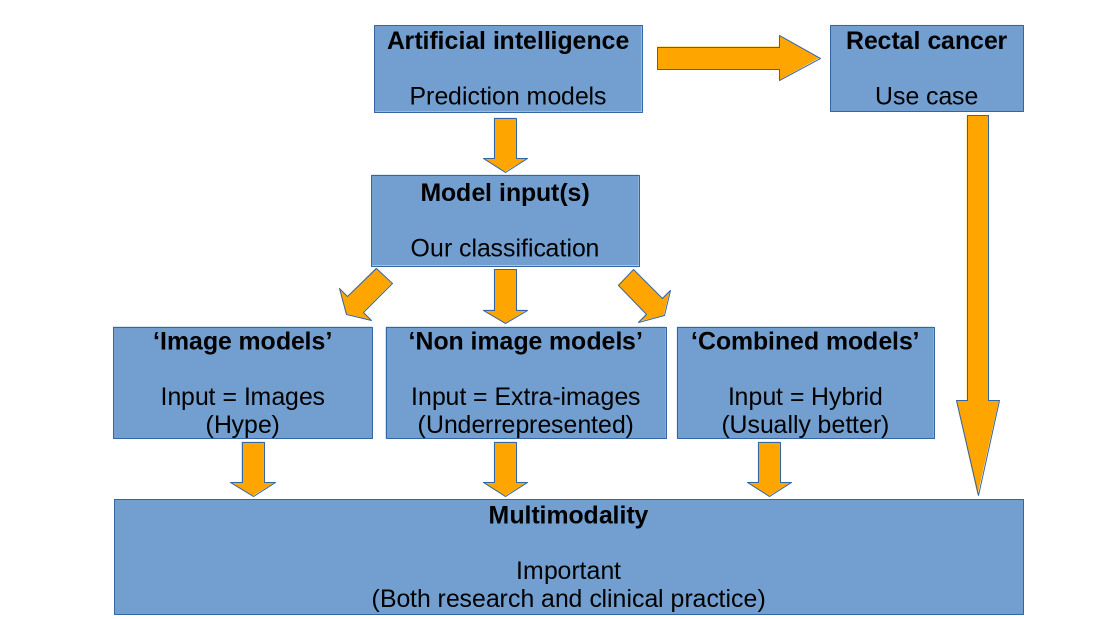

2. Results and Discussion

3. Conclusion

4. Methods

References

- Sung H et al 2021. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 71(3): 209–49. [CrossRef]

- Vos T et al 2020. Global Burden of 369 Diseases and Injuries in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990–2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet 396(10258): 1204–22. [CrossRef]

- Li A et al 2020. Clinical Trial Design: Past, Present, and Future in the Context of Big Data and Precision Medicine. Cancer 126(22): 4838–46. [CrossRef]

- Damiani A et al 2018. Large Databases (Big Data) and Evidence-Based Medicine. European Journal of Internal Medicine 53: 1–2. [CrossRef]

- De Maria Marchiano R et al 2021. Translational Research in the Era of Precision Medicine: Where We Are and Where We Will Go. Journal of Personalized Medicine 11(3): 216. [CrossRef]

- Acosta JN et al 2022. Multimodal Biomedical AI. Nature Medicine 28(9): 1773–84. [CrossRef]

- Lambin P et al 2013. Predicting Outcomes in Radiation Oncology—Multifactorial Decision Support Systems. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 10(1): 27–40. [CrossRef]

- Elmore JG et al 2021. Data Quality, Data Sharing, and Moving Artificial Intelligence Forward. JAMA Network Open 4(8): e2119345. [CrossRef]

- Torkamani A et al 2017. High-Definition Medicine. Cell 170(5): 828–843. [CrossRef]

- Cuocolo R et al 2020. Machine Learning in oncology: A clinical appraisal. Cancer Letters 481: 55–62. [CrossRef]

- Lambin P et al 2017. Radiomics: The Bridge between Medical Imaging and Personalized Medicine. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 14(12): 749–62. [CrossRef]

- Meldolesi E et al 2016. Standardized Data Collection to Build Prediction Models in Oncology: A Prototype for Rectal Cancer. Future Oncology 12(1): 119–36. [CrossRef]

- Cusumano D et al 2021. A field strength independent MR radiomics model to predict pathological complete response in locally advanced rectal cancer. Radiol Med. 126(3): 421–429. [CrossRef]

- Valentini V et al 2024. Four steps in the evolution of rectal cancer managements through 40 years of clinical practice: Pioneering, standardization, challenges and personalization. Radiother Oncol. 194: 110190. [CrossRef]

- Savino M et al 2023. A process mining approach for clinical guidelines compliance: real-world application in rectal cancer. Front Oncol. 13: 1090076. [CrossRef]

- Ramagopalan SV et al 2020. Can Real-World Data Really Replace Randomised Clinical Trials? BMC Medicine 18(1): 13. [CrossRef]

- Penberthy LT et al 2022. An Overview of Real-world Data Sources for Oncology and Considerations for Research. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 72(3): 287–300. [CrossRef]

- Morin O et al 2021. An Artificial Intelligence Framework Integrating Longitudinal Electronic Health Records with Real-World Data Enables Continuous Pan-Cancer Prognostication. Nature Cancer 2(7): 709–22. [CrossRef]

- Bi WL et al 2019. Artificial Intelligence in Cancer Imaging: Clinical Challenges and Applications. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians caac.21552. [CrossRef]

- Jia LL et al 2022. Artificial Intelligence with Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Prediction of Pathological Complete Response to Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy in Rectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Oncology 12: 1026216. [CrossRef]

- Bedrikovetski S et al 2021. Artificial Intelligence for Pre-Operative Lymph Node Staging in Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Cancer 21(1): 1058. [CrossRef]

- Coppola F et al 2021. Radiomics and Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Rectal Cancer: From Engineering to Clinical Practice. Diagnostics 11(5): 756. [CrossRef]

- Kalantar R et al 2021. Automatic Segmentation of Pelvic Cancers Using Deep Learning: State-of-the-Art Approaches and Challenges. Diagnostics 11(11): 1964. [CrossRef]

- Kuntz S et al 2021. Gastrointestinal Cancer Classification and Prognostication from Histology Using Deep Learning: Systematic Review. European Journal of Cancer 155: 200–215. [CrossRef]

- Kwok HC et al 2022. Rectal MRI Radiomics Inter- and Intra-Reader Reliability: Should We Worry about That? Abdominal Radiology 47(6): 2004–13. [CrossRef]

- Miranda J et al 2022. Rectal MRI Radiomics for Predicting Pathological Complete Response: Where We Are. Clinical Imaging 82: 141–49. [CrossRef]

- Namikawa K et al 2020. Utilizing Artificial Intelligence in Endoscopy: A Clinician’s Guide. Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology 14(8): 689–706. [CrossRef]

- Pacal I et al 2020. A Comprehensive Review of Deep Learning in Colon Cancer. Computers in Biology and Medicine 126: 104003. [CrossRef]

- Qin Y et al 2022. Review of Radiomics- and Dosiomics-Based Predicting Models for Rectal Cancer. Frontiers in Oncology 12: 913683. [CrossRef]

- Reginelli A et al 2021. Radiomics as a New Frontier of Imaging for Cancer Prognosis: A Narrative Review. Diagnostics 11(10): 1796. [CrossRef]

- Staal FCR et al 2021. Radiomics for the Prediction of Treatment Outcome and Survival in Patients With Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review. Clinical Colorectal Cancer 20(1): 52–71. [CrossRef]

- Stanzione A et al 2021. Radiomics and Machine Learning Applications in Rectal Cancer: Current Update and Future Perspectives. World Journal of Gastroenterology 27(32): 5306–21. [CrossRef]

- Tabari A et al 2022. Role of Machine Learning in Precision Oncology: Applications in Gastrointestinal Cancers. Cancers 15(1): 63. [CrossRef]

- Wang PP et al 2021. Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Based Artificial Intelligence Model in Rectal Cancer. World Journal of Gastroenterology 27(18): 2122–30. [CrossRef]

- Wong C et al 2023. MRI-Based Artificial Intelligence in Rectal Cancer. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 57(1): 45–56. [CrossRef]

- Xu Q et al 2021. MRI Evaluation of Complete Response of Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer After Neoadjuvant Therapy: Current Status and Future Trends. Cancer Management and Research 13: 4317–28. [CrossRef]

- Peng J et al 2014. Prognostic Nomograms for Predicting Survival and Distant Metastases in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancers. PLoS ONE 9(8): e106344. [CrossRef]

- Sun Y et al 2017. A Nomogram to Predict Distant Metastasis after Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy and Radical Surgery in Patients with Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. Journal of Surgical Oncology 115(4): 462–69. [CrossRef]

- Valentini V et al 2011. Nomograms for Predicting Local Recurrence, Distant Metastases, and Overall Survival for Patients With Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer on the Basis of European Randomized Clinical Trials. Journal of Clinical Oncology 29(23): 3163–72. [CrossRef]

- Chen LD et al 2020. Preoperative Prediction of Tumour Deposits in Rectal Cancer by an Artificial Neural Network–Based US Radiomics Model. European Radiology 30(4): 1969–79. [CrossRef]

- Cheng Y et al 2021. Multiparametric MRI-Based Radiomics Approaches on Predicting Response to Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy (NCRT) in Patients with Rectal Cancer. Abdominal Radiology 46(11): 5072–85. [CrossRef]

- Cui Y et al 2019. Radiomics Analysis of Multiparametric MRI for Prediction of Pathological Complete Response to Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. European Radiology 29(3): 1211–20. [CrossRef]

- Dinapoli N et al 2018. Magnetic Resonance, Vendor-Independent, Intensity Histogram Analysis Predicting Pathologic Complete Response After Radiochemotherapy of Rectal Cancer. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics 102(4): 765–74. [CrossRef]

- Ding L et al 2020. A Deep Learning Nomogram Kit for Predicting Metastatic Lymph Nodes in Rectal Cancer. Cancer Medicine 9(23): 8809–20. [CrossRef]

- Huang YQ et al 2016. Development and Validation of a Radiomics Nomogram for Preoperative Prediction of Lymph Node Metastasis in Colorectal Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 34(18): 2157–64. [CrossRef]

- Jin C et al 2021. Predicting Treatment Response from Longitudinal Images Using Multi-Task Deep Learning. Nature Communications 12(1): 1851. [CrossRef]

- Kleppe A et al 2022. A Clinical Decision Support System Optimising Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Colorectal Cancers by Integrating Deep Learning and Pathological Staging Markers: A Development and Validation Study. The Lancet Oncology 23(9): 1221–32. [CrossRef]

- Li M et al 2021. Radiomics for Predicting Perineural Invasion Status in Rectal Cancer. World Journal of Gastroenterology 27(33): 5610–21. [CrossRef]

- Liu H et al 2022. A Deep Learning Model Based on MRI and Clinical Factors Facilitates Noninvasive Evaluation of KRAS Mutation in Rectal Cancer. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 56(6): 1659–68. [CrossRef]

- Liu S et al 2021. Machine Learning-Based Radiomics Nomogram for Detecting Extramural Venous Invasion in Rectal Cancer. Frontiers in Oncology 11: 610338. [CrossRef]

- Liu X et al 2021. Deep Learning Radiomics-Based Prediction of Distant Metastasis in Patients with Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer after Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy: A Multicentre Study. eBioMedicine 69: 103442. [CrossRef]

- Mao Y et al 2022. Pre-Treatment Computed Tomography Radiomics for Predicting the Response to Neoadjuvant Chemoradiation in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer: A Retrospective Study. Frontiers in Oncology 12: 850774. [CrossRef]

- Peterson KJ et al 2023. Predicting Neoadjuvant Treatment Response in Rectal Cancer Using Machine Learning: Evaluation of MRI-Based Radiomic and Clinical Models. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery 27(1): 122–30. [CrossRef]

- van Stiphout RGPM et al 2011. Development and External Validation of a Predictive Model for Pathological Complete Response of Rectal Cancer Patients Including Sequential PET-CT Imaging. Radiotherapy and Oncology 98(1): 126–33. [CrossRef]

- van Stiphout RGPM et al 2014. Nomogram Predicting Response after Chemoradiotherapy in Rectal Cancer Using Sequential PETCT Imaging: A Multicentric Prospective Study with External Validation. Radiotherapy and Oncology 113(2): 215–22. [CrossRef]

- Wan L et al 2019. Developing a Prediction Model Based on MRI for Pathological Complete Response after Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. Abdominal Radiology 44(9): 2978–87. [CrossRef]

- Wei Q et al 2023. External Validation and Comparison of MR-Based Radiomics Models for Predicting Pathological Complete Response in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer: A Two-Centre, Multi-Vendor Study. European Radiology 33(3): 1906–17. [CrossRef]

- Wei Q et al 2023. Preoperative MR Radiomics Based on High-Resolution T2-Weighted Images and Amide Proton Transfer-Weighted Imaging for Predicting Lymph Node Metastasis in Rectal Adenocarcinoma. Abdominal Radiology 48(2): 458–70. [CrossRef]

- Yi X et al 2019. MRI-Based Radiomics Predicts Tumor Response to Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. Frontiers in Oncology 9: 552. [CrossRef]

- Roselló S et al 2018. Integrating Downstaging in the Risk Assessment of Patients With Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer Treated With Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy: Validation of Valentini’s Nomograms and the Neoadjuvant Rectal Score. Clinical Colorectal Cancer 17(2): 104–112.e2. [CrossRef]

- Tang B et al 2022. Local Tuning of Radiomics-Based Model for Predicting Pathological Response to Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. BMC Medical Imaging 22(1): 44. [CrossRef]

- Collins GS et al 2015. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. BMJ 350, g7594–g7594. [CrossRef]

- Montesinos-López OA et al 2022. Accounting for Correlation Between Traits in Genomic Prediction. Methods in Molecular Biology 2467: 285–327. [CrossRef]

- Lipkova J et al 2022. Artificial Intelligence for Multimodal Data Integration in Oncology. Cancer Cell 40(10): 1095–1110. [CrossRef]

- Feng L et al 2022. Development and Validation of a Radiopathomics Model to Predict Pathological Complete Response to Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer: A Multicentre Observational Study. The Lancet Digital Health 4(1): e8–17. [CrossRef]

- Kim DW et al 2019. Design Characteristics of Studies Reporting the Performance of Artificial Intelligence Algorithms for Diagnostic Analysis of Medical Images: Results from Recently Published Papers. Korean Journal of Radiology 20(3): 405. [CrossRef]

| Reference | First author | Year | Journal | Aim | Number of patients | TRIPOD | AI model(s) | ||

| Total | Training | Validation | |||||||

| NIMs | |||||||||

| 37 | Peng J | 2014 | PLOS One | Predict OS, DMs (and LR) | 917 | 833 | 84 | 2b | Cox regression |

| 38 | Sun Y | 2017 | Journal of Surgical Oncology | Predict DMs after nCRT | 522 | 425 | 97 | 2b | Cox regression |

| 39 | Valentini V | 2011 | Journal of Clinical Oncology | Predict OS, LR, DMs | 2795 | 2242 | 553 | 3 | Cox regression |

| CMs | |||||||||

| 40 | Chen LD | 2020 | European Radiology | Predict TDs | 127 | 87 | 40 | 2b | ANN |

| 41 | Cheng Y | 2021 | Abdominal Radiology | Predict response (particularly, pCR) to nCRT | 193 | 128 | 65 | 2a | Logistic regression |

| 42 | Cui Y | 2019 | European Radiology | Predict response (particularly, pCR) to nCRT | 186 | 131 | 55 | 2a | Logistic regression |

| 43 | Dinapoli N | 2018 | International Journal of Radiation Oncology | Predict response (particularly, pCR) to nCRT | 221 | 162 | 59 | 3 | GLM |

| 44 | Ding L | 2020 | Cancer Medicine | Predict preoperative LN metastases | 545 | 362 | 183 | 2a | Logistic regression, DL |

| 45 | Huang YQ | 2016 | Journal of Clinical Oncology | Predict preoperative LN metastases | 526 | 326 | 200 | 2b | Logistic regression |

| 46 | Jin C | 2021 | Nature Communications | Predict response (particularly, pCR) to nCRT | 622 | 321 | 301 | 3 | DL |

| 47 | Kleppe A | 2022 | Lancet Oncology | Optimize adjuvant therapy | 2072 | 997 | 1075 | 3 | Cox regression, DL |

| 48 | Li M | 2021 | World Journal of Gastroenterology | Predict PNI | 303 | 242 | 61 | 2a | Logistic regression |

| 49 | Liu H | 2022 | Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging | Evaluate KRAS mutation | 376 | 288 | 88 | 2a | Logistic regression, DL |

| 50 | Liu S | 2021 | Frontiers in Oncology | Detect preoperative EMVI | 281 | 198 | 83 | 2b | Logistic regression |

| 51 | Liu X | 2021 | Lancet EBioMedicine | Predict DMs after nCRT | 235 | 170 | 65 | 3 | DL |

| 52 | Mao Y | 2022 | Frontiers in Oncology | Predict response (particularly, pCR) to nCRT | 216 | 151 | 65 | 2a | Logistic regression |

| 53 | Peterson KJ | 2023 | Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery | Predict response (particularly, pCR) to nCRT | 131 | 111 | 20 | 2a | Logistic regression |

| 54 | van Stiphout RGPM | 2011 | Radiotherapy & Oncology | Predict response (particularly, pCR) to nCRT | 953 | Various groupings | 3 | SVM | |

| 55 | van Stiphout RGPM | 2014 | Radiotherapy & Oncology | Predict response (particularly, pCR) to nCRT | 190 | 112 | 78 | 3 | Logistic regression |

| 56 | Wan L | 2019 | Abdominal Radiology | Predict response (particularly, pCR) to nCRT | 120 | 84 | 36 | 2b | Logistic regression |

| 57 | Wei Q | 2023 | European Radiology | Predict response (particularly, pCR) to nCRT | 151 | 100 | 51 | 3 (plus 2a) | RF |

| 58 | Wei Q | 2023 | Abdominal Radiology | Predict preoperative LN metastases | 125 | 80 | 45 | 2a | Logistic regression |

| 59 | Yi X | 2019 | Frontiers in Oncology | Predict response (particularly, pCR) to nCRT | 134 | 101 | 33 | 2a | SVM, RF, LASSO |

| Reference | First author | Year | Model input(s) | Performance | Number of centers | External validation(s)? | Note | ||

| Non images? | Images? | CM better? | |||||||

| NIMs | |||||||||

| [37] | Peng J | 2014 | Yes (demographic and clinicopathological) | C-Index = 0.73–0.76 | 1 | No | |||

| [38] | Sun Y | 2017 | Yes (clinicopathological) |

C-Index = 0.71 | 1 | No | |||

| [39] | Valentini V | 2011 | Yes | C-Index = 0.68–0.73 | 5 | Yes | Subsequently re-validated by Reference [60] | ||

| CMs | |||||||||

| [40] | Chen LD | 2020 | Yes (clinical) | Yes (radiomics, ANN, US) | Yes | AUC = 0.80 | 1 | No | |

| [41] | Cheng Y | 2021 | Yes | Yes (radiomics, MRI) | Yes | AUC = 0.91–0.94 | 1 | No | |

| [42] | Cui Y | 2019 | Yes (from EHRs) | Yes (radiomics, MRI) | Yes | AUC = 0.97 | 1 | No | |

| [43] | Dinapoli N | 2018 | Yes (clinical) | Yes (radiomics, MRI) | AUC = 0.75 | 3 | Yes | Subsequently re-validated by Reference [61] | |

| [44] | Ding L | 2020 | Yes | Yes (DL, MRI) | AUC = 0.89–0.92 | 1 | No | ||

| [45] | Huang YQ | 2016 | Yes (clinicopathological) |

Yes (radiomics, CT) | C-Index = 0.78 | 1 | No | ||

| [46] | Jin C | 2021 | Yes (blood tumor markers) | Yes (DL, MRI) | Yes | AUC = 0.97 | 3 | Yes | |

| [47] | Kleppe A | 2022 | Yes (markers) | Yes (DL, histopathology) | Yes | HR = 3.06–10.71 | 3 | Yes | |

| [48] | Li M | 2021 | Yes (clinical) | Yes (radiomics, CT) | Yes | AUC = 0.80 | 1 | No | |

| [49] | Liu H | 2022 | Yes (clinical) | Yes (DL, MRI) | Yes | AUC = 0.84 | 1 | No | |

| [50] | Liu S | 2021 | Yes (clinical) | Yes (radiomics, MRI) | Yes | AUC = 0.86 | 1 | No | |

| [51] | Liu X | 2021 | Yes (clinicopathological) |

Yes (radiomics, DL, MRI) | Yes | C-Index = 0.78 | 3 | Yes | |

| [52] | Mao Y | 2022 | Yes (clinicopathological) |

Yes (radiomics, CT) | Yes | AUC = 0.87 | 1 | No | |

| [53] | Peterson KJ | 2023 | Yes (clinical [from EHRs]) | Yes (radiomics, MRI) | Yes | AUC = 0.73 | 1 | No | |

| [54] | van Stiphout RGPM | 2011 | Yes (clinical) | Yes (PET-CT) | Yes | AUC = 0.86 | 4 | Yes | |

| [55] | van Stiphout RGPM | 2014 | Yes (clinical) | Yes (PET-CT) | AUC = 0.70 | 2 | Yes | ||

| [56] | Wan L | 2019 | Yes (clinical) | Yes (MRI) | Yes | AUC = 0.84 | 1 | No | |

| [57] | Wei Q | 2023 | Yes (clinical) | Yes (radiomics, MRI) | Yes | AUC = 0.87 | 2 | Yes | |

| [58] | Wei Q | 2023 | Yes (clinical) | Yes (radiomics, MRI) | Yes | AUC = 0.85 | 1 | No | |

| [59] | Yi X | 2019 | Yes (radiological, clinicopathological) |

Yes (radiomics, MRI) | AUC = 0.90–0.93 | 1 | No | ||

| Reference | First author | Year | Journal | IMs | CMs | NIMs | Notes |

| [11] | Lambin P | 2017 | Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology | Main focus | Briefly mentioned | Not present | Radiomics |

| [12] | Meldolesi E | 2016 | Future Oncology | ||||

| [20] | Jia LL | 2022 | Frontiers in Oncology | Systematic review (with meta-analysis) | |||

| [21] | Bedrikovetski S | 2021 | BMC Cancer | ||||

| [22] | Coppola F | 2021 | Diagnostics | Radiomics | |||

| [23] | Kalantar R | 2021 | Diagnostics | Deep learning | |||

| [24] | Kuntz S | 2021 | European Journal of Cancer | Deep learning; Systematic review | |||

| [25] | Kwok HC | 2022 | Abdominal Radiology | Radiomics | |||

| [26] | Miranda J | 2022 | Clinical Imaging | ||||

| [27] | Namikawa K | 2020 | Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology | ||||

| [28] | Pacal I | 2020 | Computers in Biology and Medicine | Deep learning | |||

| [29] | Qin Y | 2022 | Frontiers in Oncology | Radiomics | |||

| [30] | Reginelli A | 2021 | Diagnostics | ||||

| [31] | Staal FCR | 2021 | Clinical Colorectal Cancer | Radiomics; Systematic review | |||

| [32] | Stanzione A | 2021 | World Journal of Gastroenterology | Radiomics | |||

| [33] | Tabari A | 2022 | Cancers | ||||

| [34] | Wang PP | 2021 | World Journal of Gastroenterology | ||||

| [35] | Wong C | 2023 | Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging | ||||

| [36] | Xu Q | 2021 | Cancer Management and Research |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).