1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a prevalent malignancy globally[

1]; however, its incidence can be mitigated through risk factor modification and removal of precancerous lesions[2-4]. Incorporating Artificial Intelligence (AI), especially deep learning, into digestive endoscopy significantly advances early CRC diagnosis and treatment, particularly in polyp detection. AI systems enhance diagnostic capabilities by analyzing large datasets of annotated images using deep neural networks [

5].

High adenoma miss rates in endoscopy are a critical issue, as studies show many polyps are overlooked even by skilled endoscopists. While additional colonoscopies might reduce miss rates, conducting more than two procedures is impractical due to logistical and ethical concerns, increased patient risk, discomfort, and strain on healthcare resources [6-9].

These limitations highlight the need for new techniques like AI to address these challenges. AI-assisted colonoscopy can enhance polyp detection rates, compensating for human error and variability [10-13]. However, developing these tools involves challenges, including ethical considerations of data collection, patient privacy, and adherence to data protection laws when using patient data for AI training [

14].

For the training of recent AI image recognition algorithms [

15], we utilized not only real images and datasets but also incorporated synthetic datasets generated through advanced techniques such as GANs [16-17] and diffusion models [

18]. Furthermore, we introduced an innovative concept: “pseudosynthetic” data. This data is derived from original datasets and enhanced through augmentation techniques such as flipping, rotating, and contrast adjustment. Pseudosynthetic data is different than augmented data as it replaces the need of repeating the medical procedure – a practice generally not recommended – that leads to generation of data, in our case – colonoscopies – and it can be traced to source, addressing also ethical concerns on data collection[

19,

20].

The variability in patient presentations, equipment, and clinical scenarios are essential for training robust AI models by adding complexity to the development of effective diagnostic tools. Thus, AI holds the potential to significantly reduce adenoma miss rates and improve outcomes for CRC screening. By augmenting existing data, we simulate repeated endoscopic procedures without subjecting patients to multiple colonoscopies, which is impractical in clinical settings. Pseudosynthetic data offers a novel approach where augmented data can be traced back to its original form, unlike fully synthetic data that is often disconnected from real clinical inputs. This traceability significantly benefits result validation and ensures the reproducibility of AI models, especially in critical tasks like polyp detection and reducing adenoma miss rates.

Pseudosynthetic data is promising because it simulates additional colonoscopy results and can be extended to other endoscopic procedures and medical data types, including numerical datasets.

While deep learning in medical imaging is well-studied, the role of augmented and synthetic data in improving diagnostic accuracy for colon polyps remains underexplored. This research aims to evaluate whether training models on real images, pseudosynthetic data, synthetic data, and their combinations can enhance colon polyp detection accuracy in endoscopic procedures. By incorporating these datasets, we address challenges of limited availability and diversity in real-world data, enhancing data volume and improving the model's generalization ability. Utilizing synthetic data also mitigates ethical concerns related to patient privacy and consent, as these datasets do not contain personal health information.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data sources, preprocessing and augmentation

We conducted our experiements using real and synthetic polyp datasets, along with pseudosynthetic datasets as detailed below.

Kvasir-SEG contains 1,000 polyp images with corresponding ground truth masks, with resolutions ranging from 332×487 to 1920×1072 pixels [

21]. PolypGen includes colonoscopy images from six centers, involving over 300 patients, totaling 3,762 annotated polyp labels verified by six senior gastroenterologists, and features both single-frame and sequential data [

22].

We made use of Synth-Colon, a synthetic dataset comprising 20,017 realistic images generated using CycleGAN in conjunction with the Kvasir dataset[16-17]. Additionally, we generated synthetic datasets of 20,000 polyp images using a diffusion-based semantic polyp synthesis method (DDPM) guided by 5,000 masks. These synthetic images augment both the volume and diversity of the training data, aiding in the development of robust and generalizable models [

18,

23].

Before training the U-Net model, several pre-processing steps were implemented. To maintain consistency in input dimensions, all images are resized to 256×256. Images are normalized by dividing the pixel values by 255.0, scaling the pixel values to the range of [0, 1]. All masks are converted to single-channel grayscale so that pixel values above 127 are considered as belonging to the polyp class and values below 127 are considered background. Since this is known to lead to class imbalance and to enhance the model's generalizability and robustness, the image-mask pairs in the real datasets[

21,

22] underwent augmentation techniques presented below:

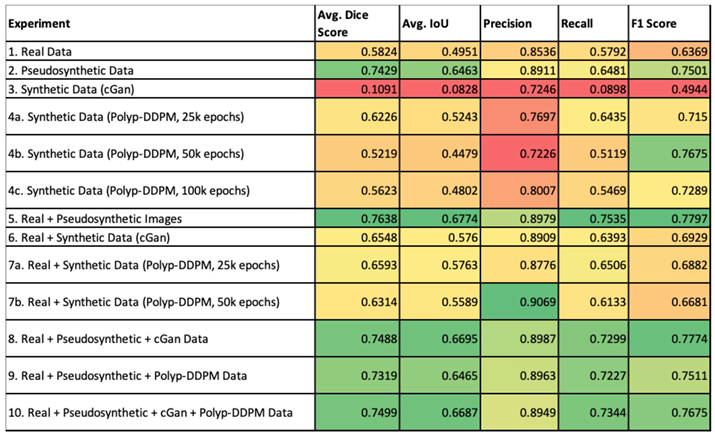

a) Spatial transformations - both images and masks

Random flips: Horizontal and vertical flips that allows for orientation variance.

Random rotation: A rotation of up to ±10 degrees that introduces geometric diversity.

Random resized crop: Randomly scales and crops the image. The scale (0.8, 1.0) parameter ensures that the crop covers between 80–100% of the original image area.

b) Color jittering – applicable only to images

Adjusts brightness (±20%), contrast (±20%), saturation (±20%), and hue (±10%). These adjustments diversify the color distribution, helping the model generalize to different lighting conditions and color variations existing in endoscopic imagery.

Seed synchronization was implemented so that image and mask undergo the same spatial transforms by resetting the random seed. This, in turn, preserves alignment between the polyp region in the mask and its corresponding region in the image.

This augmented dataset, called pseudosynthetic data, provides a more comprehensive representation of possible variations in the input data. Finally, both images and masks are converted into tensors to match the input requirements of the deep learning framework. This step preserves the alignment and dimensions needed by the U-Net model.

2.2. Model Training and Evaluation

The data was split into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets to ensure a thorough evaluation of the model's performance [

24]. The split was performed by setting a specific random seed for every experiment, making it easier to compare results and reproduce experiments. We employ a modified U-Net architecture designed for 256×256 RGB inputs, composed of an encoder, a bottleneck layer, and a symmetric decoder with skip connections. In the encoder, each level consists of two 3×3 convolution layers, each followed by a batch normalization layer—a modification compared to the original U-Net that stabilizes and accelerates training by normalizing the activations within each batch. [

15]. The model was compiled using the Adam optimizer [

25], with binary cross-entropy as the loss function [

26]. Metrics including accuracy, precision, recall, dice coefficient, IoU, and F1 score were used to evaluate the model's performance [

24].

Callbacks for model checkpointing, early stopping, and TensorBoard logging were implemented to monitor and enhance the training process [

24]. The trained model's performance was evaluated on the test set to assess its generalizability and effectiveness in segmenting unseen data.

In this study, we place particular emphasis on the importance of precision-recall as a key metric in model evaluation, in addition to more traditional metrics. Given the clinical significance of accurately detecting polyps while minimizing false positives and false negatives, precision-recall offers valuable insight into model performance, particularly in scenarios with imbalanced data, where accuracy alone may not provide a comprehensive assessment of the model's effectiveness [

27].

2.3. Qualitative Evaluation

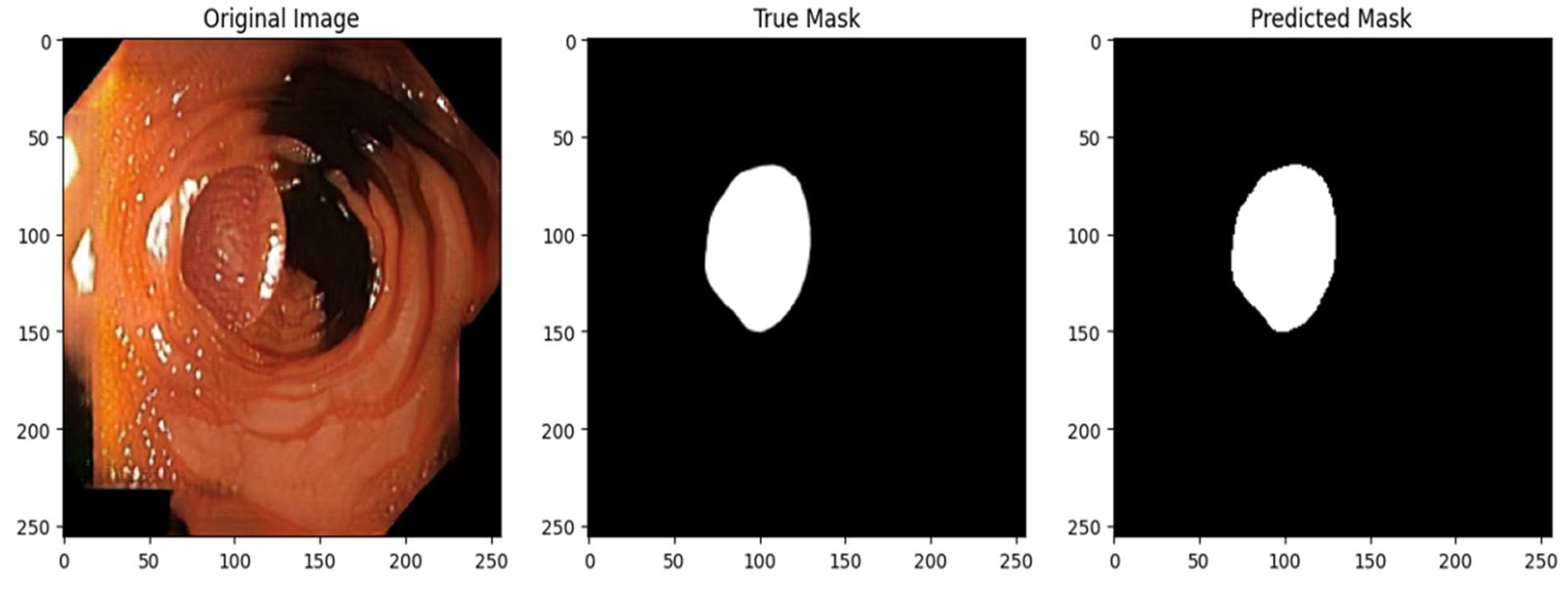

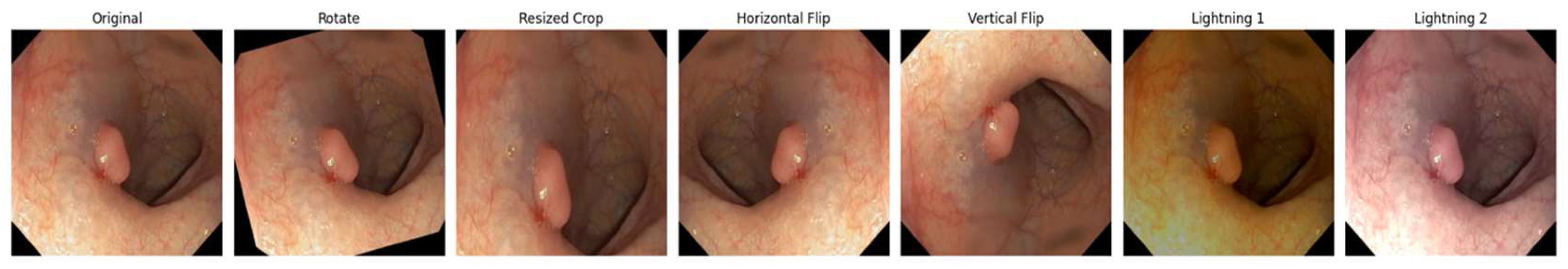

In addition to quantitative metrics, the model's segmentation accuracy was qualitatively evaluated by a gastroenterologist through visual comparison of predicted polyp masks with actual masks on part of the test set. Predictions from randomly selected test images were thresholded to create binary masks for direct comparison. Visualizations were created for five test images, displaying the original image, the ground truth mask, and the model's predicted mask side by side.

2.4. Experiments

All experiments were performed using Python as programming language, Google Colab environment for implementation. Training was performed on Nvidia A100 High-RAM GPU. After training, all resulting models were submitted to external validation using CVC-Colon-DB dataset comprising of 612 image-mask pairs [

28]. We validated dataset realism and diagnostic utility using performance metrics (precision, recall, Dice coefficient, IoU, and F1 score) and external validation on the CVC-Colon-DB dataset (612 image-mask pairs). A gastroenterologist visually assessed segmentation accuracy to ensure clinical relevance. Pseudosynthetic data preserved traceability through controlled augmentations, while synthetic data underwent visual checks for anatomical plausibility.

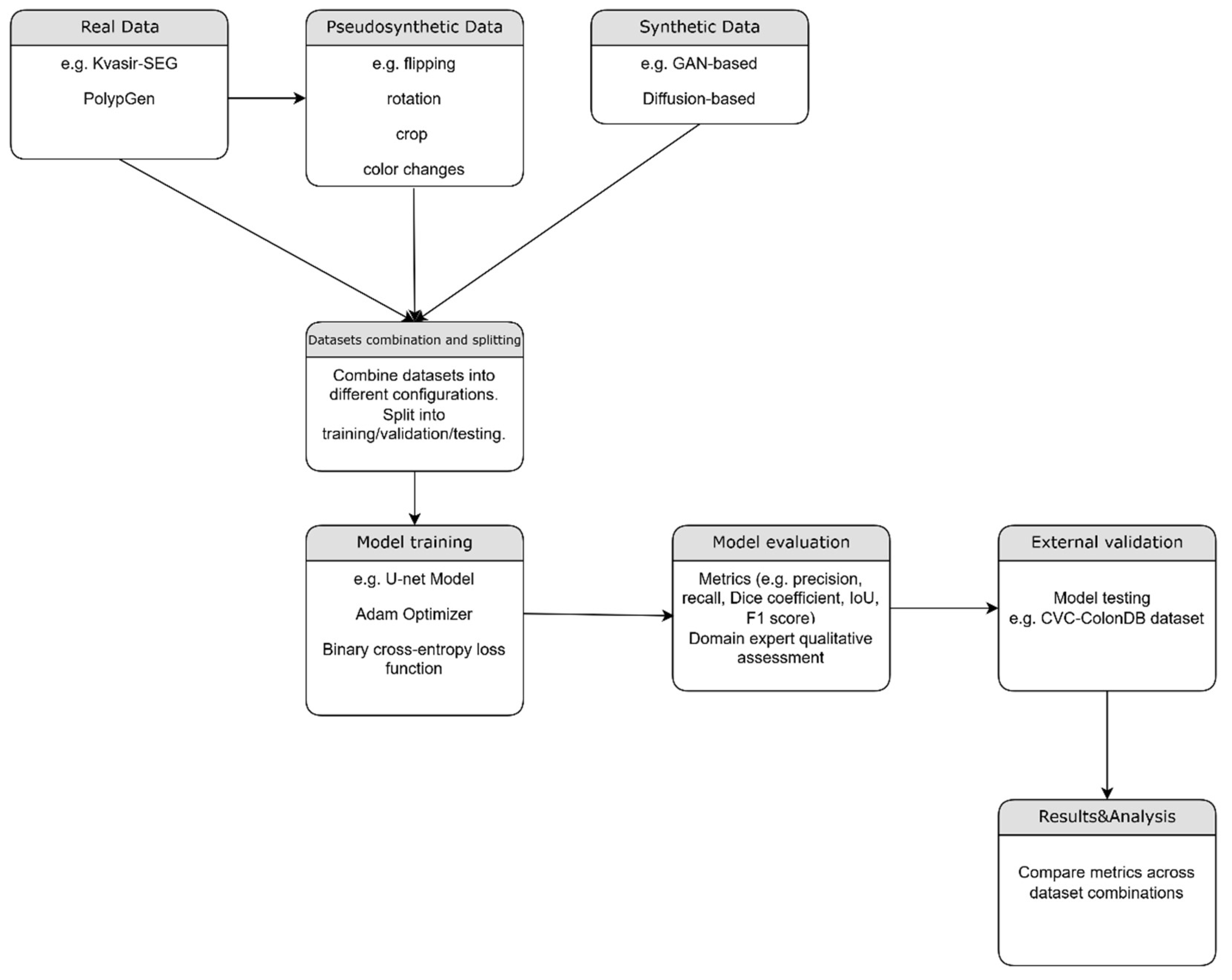

Figure 2.

– Flowchart of the proposed method.

Figure 2.

– Flowchart of the proposed method.

2.4.1. Real Data (Baseline)

We aimed to establish a baseline performance using real-world data, serving as a foundation for comparison with subsequent experimental setups. This experiment included a total of 4762 real images, combining 1000 images from the Kvasir-SEG dataset and 3762 images from the PolypGen dataset.

2.4.2. Pseudosynthetic Data

Our objective was to assess the model's ability to generalize from an augmented dataset reflecting a broader spectrum of conditions than the original. We applied six augmentations to each image from the combined Kvasir-SEG and PolypGen datasets, resulting in 28,572 images. Spatial transformations—flips, rotations, and resized crops—were applied to both images and masks to mimic variations in polyp appearance. Color transformations, adjusting brightness, contrast, saturation, and hue, were applied only to images to simulate different lighting conditions. A custom data generator managed image loading, preprocessing (resizing and normalization), and batch creation for model training.

2.4.3. Synthetic Data (CycleGAN and Polyp-DDPM

Our aim was to assess the model's performance when trained exclusively on synthetic data, exploring whether it can supplement or replace real data when it is scarce or incomplete. We used the Synth-Colon dataset, comprising 20,017 synthetic images generated using the CycleGAN model based on the Kvasir dataset. Afterwards, we evaluated the U-Net model trained exclusively on synthetic data generated using Polyp-DDPM, a diffusion-based semantic polyp synthesis method, by training on the Kvasir dataset of 1,000 image-mask pairs for 25,000, 50,000, and 100,000 epochs. Using 5,000 masks, we generated 20,000 new image-mask pairs, which were then used to train the U-Net model.

2.4.4. Experiments using combinations of datasets

a. Real and pseudosynthetic data

To assess the expected improvement from adding pseudosynthetic data to real data, we trained the U-Net model using a total of 33,334 image-mask pairs—comprising 4,762 real pairs and 28,572 pseudosynthetic pairs.

b. Real and synthetic data (cGan)

In this experiment the U-Net model was trained using real image dataset and the cGan synthetic dataset, for a total of 24779 pairs of images and masks.

c. Real and synthetic data (Polyp-DDPM)

We conducted two experiments using both real and Polyp-DDPM generated datasets. In the first experiment, we combined the real dataset with synthetic data generated by a model trained for 25,000 epochs. In the second experiment, we used the real dataset along with synthetic data from a model trained for 50,000 epochs. In both experiments, the datasets consisted of 4,762 real images and 20,000 synthetic images.

d. Real, pseudosynthetic and synthetic data(cGan)

We evaluated the model's performance when trained on a dataset consisting in 4762 real Images, 28572 pseudosynthetic Images and 20017 synthetic images generated using CycleGAN.

e. Real, pseudosynthetic and synthetic data (Polyp-DDPM)

In this experiment, we used Polyp-DDPM generated dataset (image generation model trained for 25000 epochs) along with real and pseudosynthetic datasets.

f. Real, pseudosynthetic and all synthetic data(cGan + Polyp-DDPM)

Finally, we combined the real dataset with pseudosynthetic images and synthetic data generated by both CycleGAN and Polyp-DDPM models (the latter trained for 25,000 epochs). This resulted in a total of 73,351 image-mask pairs, which were used to train the U-Net segmentation model.

3. Results

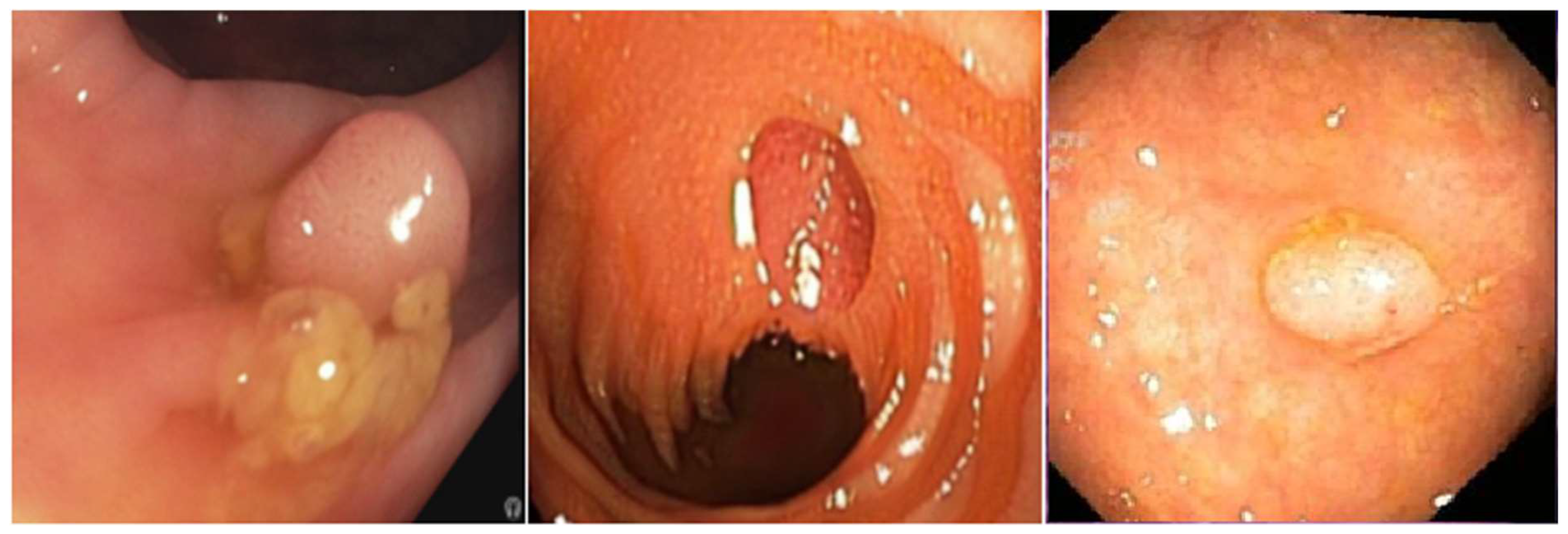

Figure 3.

– Examples of datasets used: Pseudosynthetic data (left). Synthetic-CycleGAN (middle); Synthetic-DDPM (right);.

Figure 3.

– Examples of datasets used: Pseudosynthetic data (left). Synthetic-CycleGAN (middle); Synthetic-DDPM (right);.

3.1. Training on Real data

The model was set for training for 40 epochs, with early stopping activated at epoch 24 to prevent overfitting. The final test metrics included a loss of 0.1289, accuracy of 0.9709, precision of 0.9003, recall of 0.7307, Dice coefficient of 0.7911, IoU of 0.6593, and F1 score of 0.7903.

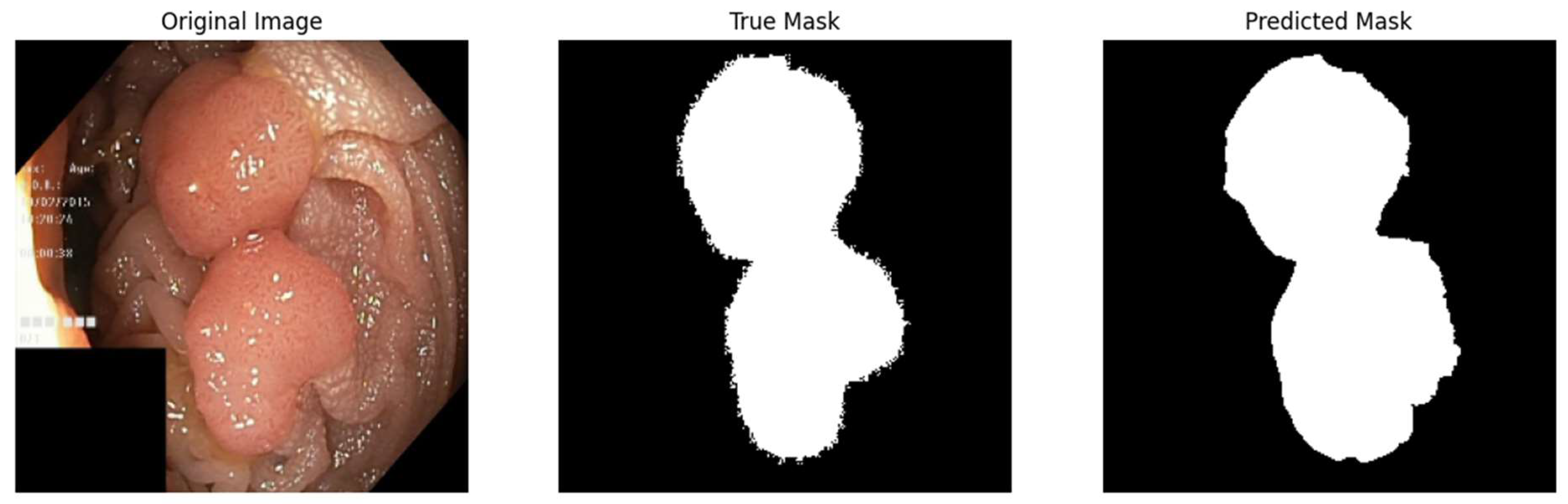

Figure 4.

– Qualitative assessment of segmentation accuracy – true vs predicted mask.

Figure 4.

– Qualitative assessment of segmentation accuracy – true vs predicted mask.

3.2. Training on pseudosynthetic data

When training on pseudosynthetic data, early stopping was activated at epoch 24 during the training. The model's evaluation results show a test loss of 0.1045, a test accuracy of 0.9787, precision of 0.9212, recall of 0.8672, a dice coefficient of 0.8847, IoU of 0.7948, and an F1 score of 0.8950.

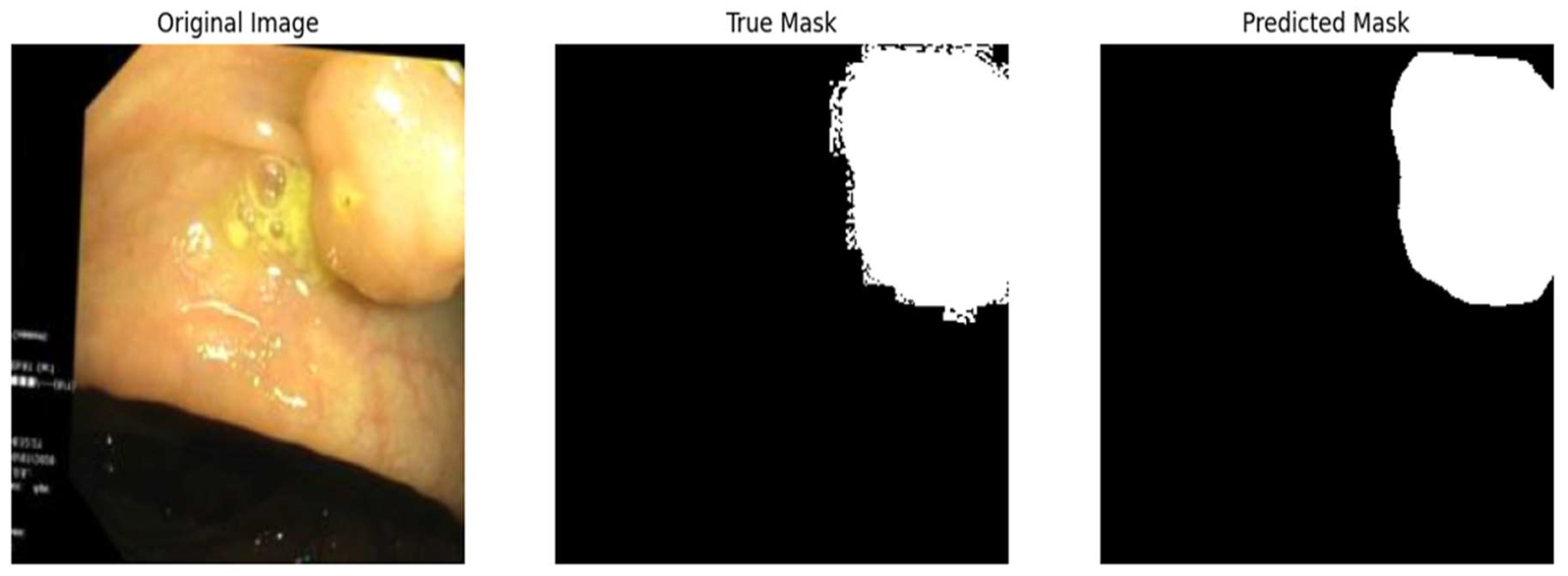

Figure 5.

– Qualitative assessment of segmentation accuracy – true vs. predicted mask.

Figure 5.

– Qualitative assessment of segmentation accuracy – true vs. predicted mask.

3.3. Training on synthetic data (cGan)

Experiment 3 focused on training the model exclusively on synthetic data over 20 epochs. On the test set, the model achieved a loss of 0.0045, accuracy of 0.9950, precision of 0.9954, recall of 0.9631, Dice coefficient of 0.9809, and IoU of 0.9625.

Figure 6.

– Qualitative assessment of segmentation accuracy – true vs. predicted mask.

Figure 6.

– Qualitative assessment of segmentation accuracy – true vs. predicted mask.

3.4. Training on synthetic data (Polyp-DDPM)

We trained a model to generate synthetic images using three different settings and then trained the U-Net with each generated dataset. Results are as follows:

Test metrics (25,000 epochs): loss of 0.0259, accuracy of 0.9915, precision of 0.9301, recall of 0.9218, Dice coefficient of 0.9061, IoU of 0.8289, and F1 score of 0.9253.

Test metrics (50,000 epochs): loss of 0.0158, accuracy of 0.9952, precision of 0.9675, recall of 0.9496, Dice coefficient of 0.9521, IoU of 0.9087, and F1 score of 0.9589

Test metrics (100,000 epochs): loss of 0.0112, accuracy of 0.9962, precision of 0.9714, recall of 0.9633, Dice coefficient of 0.9607, IoU of 0.9245, and F1 score of 0.9672.

Figure 7.

– Qualitative assessment of segmentation accuracy – true vs. predicted mask.

Figure 7.

– Qualitative assessment of segmentation accuracy – true vs. predicted mask.

3.5. Real and pseudosynthetic images

For real and pseudosynthetic images, the test metrics included a loss of 0.1078, accuracy of 0.9783, precision of 0.9349, recall of 0.8480, Dice coefficient of 0.8799, IoU of 0.7875, and F1 score of 0.8832.

3.6. Real and synthetic data (cGan, Polyp-DDPM )

For the experiment using real and cGan generated datasets, the test metrics: loss of 0.0518, accuracy of 0.9807, precision of 0.9305, recall of 0.7284, Dice coefficient of 0.7312, IoU of 0.6559, and F1 score of 0.7745.

For real and synthetic data (Polyp-DDPM), the model was trained using two different settings:

Test metrics (25,000 epochs model): loss of 0.0593, accuracy of 0.9863, precision of 0.9249, recall of 0.8546, Dice coefficient of 0.8739, IoU of 0.7778, and F1 score of 0.8908.

Test metrics(50,000 epochs model): loss of 0.0415, accuracy of 0.9899, precision of 0.9503, recall of 0.8888, Dice coefficient of 0.9075, IoU of 0.8326, and F1 score of 0.9142.

3.7. Real, pseudosynthetic, synthetic

For the combination of real, pseudosynthetic, and cGan data, the test metrics included: loss of 0.0589, accuracy of 0.9869, precision of 0.9509, recall of 0.8918, Dice coefficient of 0.9114, IoU of 0.8386, and F1 score of 0.9197.

For the experiment using real, pseudosynthetic, Polyp-DDPM data, the test metrics included: loss of 0.0776, accuracy of 0.9811, precision of 0.9243, recall of 0.8450, Dice coefficient of 0.8667, IoU of 0.7681, and F1 score of 0.8850.

For real, pseudosynthetic, and synthetic (cGan + Polyp-DDPM) data, test metrics included: loss of 0.0508, accuracy of 0.9872, precision of 0.9389, recall of 0.8904, Dice coefficient of 0.9018, IoU of 0.8228, and F1 score of 0.9116.

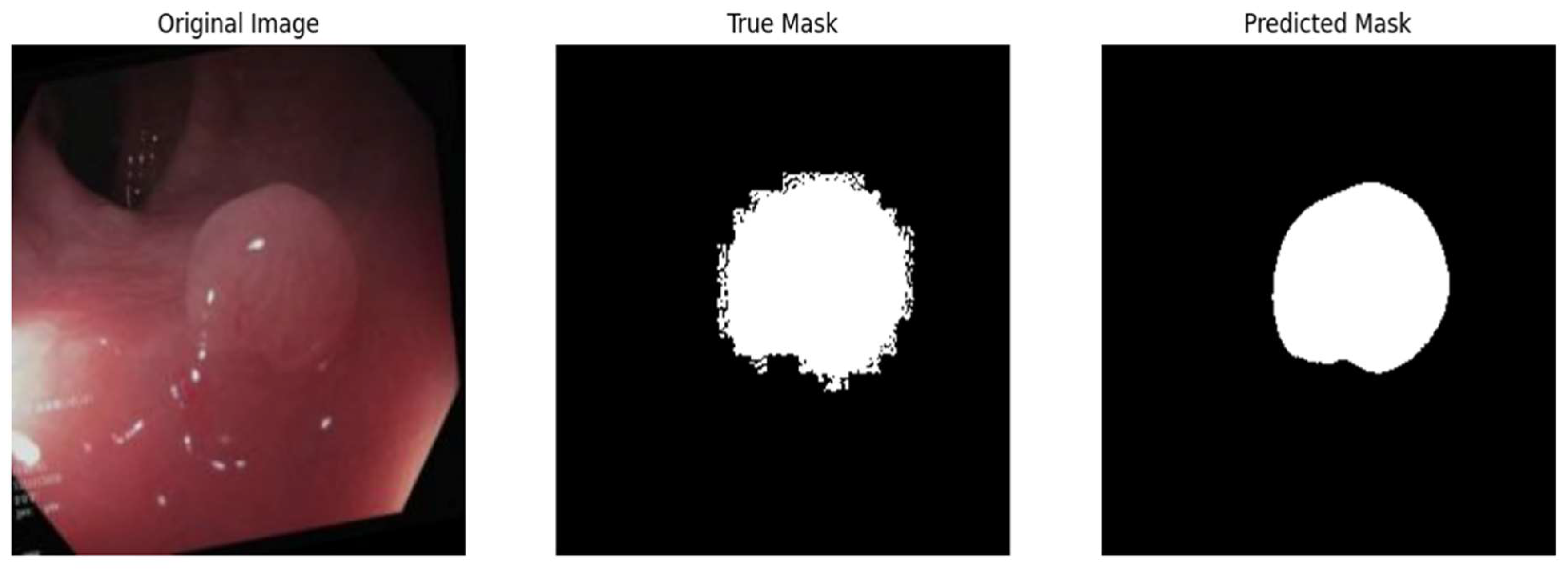

The external validation data for all experiments is summarised in the table below. It employs a color gradient to visually represent the performance of various experiments across different metrics.

Table 1.

External validation metrics for all experiments. Color map: red is worse performance, green means better performance.

Table 1.

External validation metrics for all experiments. Color map: red is worse performance, green means better performance.

4. Discussions

Performing multiple colonoscopies on the same patient within short intervals is impractical due to ethical concerns, patient safety, and the invasive nature of the procedure. Frequent colonoscopies carry risks like bowel perforation, infection, and patient discomfort. Moreover, there's limited clinical need for rapid repeat colonoscopies, as significant pathological changes, such as polyp growth or morphological alterations, typically occur over longer periods[

29,

30]. While back-to-back colonoscopies are occasionally performed for immediate reassessment, images from successive procedures often show minimal differences, leading to limited dataset variability. Since polyp morphology and surrounding mucosa remain largely unchanged over short times, this redundancy can hinder the development of machine learning models, which require diverse and representative datasets to perform accurately. Pseudosynthetic data, derived from augmentation of real-world colonoscopy images, provides a solution to this challenge. By applying augmentation techniques, pseudosynthetic data introduces controlled variations to the original images while preserving the clinical characteristics of the source data. This process enhances the diversity of the dataset, simulating conditions that could occur in future colonoscopies without requiring additional invasive procedures on patients. Consequently, pseudosynthetic data allows for the creation of robust models that are trained to recognize a broader range of polyp appearances, while maintaining the traceability and clinical relevance of the original images. Conversely, synthetic data generated using GANs or diffusion models, though effective in increasing the diversity of datasets, lacks this traceability. Such models are trained on real data but produce entirely novel images that cannot be traced back to specific instances in the original dataset. This decoupling from the source data raises concerns about the interpretability and validation of the generated data, as it cannot be directly attributed to any real-world image or clinical case. Pseudosynthetic data offers a distinct advantage over purely synthetic data due to traceability which allows direct reference to original clinical images. Optimal traceability facilitates regulatory approval, transparency in data origins, reproducibility of results, and accountability in model validation. It also supports clinical adoption by improving trust in AI outputs, as models trained with traceable data can be validated against real-world scenarios, addressing key compliance and ethical concerns in AI assisted diagnostics .

The choice between pseudosynthetic and synthetic data depends largely on the application. If traceability, clinical relevance, and regulatory approval are priorities, then pseudosynthetic data is preferable due to its verifiable connection to real-world images. It’s safer and more reliable when clinical decision-making is at stake because you can always refer back to the original patient data. On the other hand, if the goal is to build robust machine learning models that can handle a wide variety of cases, including rare or extreme examples, synthetic data can be very valuable. It allows for broader generalization and better model training, but with the risk that some of the generated data may not be clinically relevant or reliable. There are multiple models that can be trained to detect polyps from colonoscopy images. We chose U-net as it was specifically designed for medical image segmentation. Its architecture, with a contracting path for context capture and a symmetric expanding path for precise localization, is well suited for tasks like polyp detection where both the global context and local details are important. It can be trained with a relatively small amount of images and still produce high-quality results, mitigating an important aspect in medical imaging tasks where annotated data can be scarce and expensive to obtain, such as the case of digestive endoscopy. U-Net has a strong track record of successful applications in medical image segmentation tasks as It has been widely used and validated in various studies[31-33]. Overfitting is a concern in deep learning, especially when dealing with limited datasets typical in the medical imaging domain. It occurs when a model learns the details and noise in the training data to an extent that it negatively impacts the performance of the model on new data. This is particularly problematic for tasks like polyp detection from colonoscopy images, where the model's ability to generalize to unseen data is required for its clinical utility. Pseudosynthetic and synthetic data were used to combat overfitting by introducing more variability that mimicked real-world conditions. This variability prevented the model from memorizing specific image patterns, which led to promoting the learning of more general features that are indicative of polyps. The implementation of early stopping mechanisms was another way to limit overfitting. By monitoring the validation loss and halting the training process when no improvement was observed for 10 epochs, the model was protected from the risk of becoming overly attuned to the training data and obtaining the right balance between learning from the data and maintaining the ability to perform well on new, unseen data.

The model trained on pseudosynthetic data showed good generalization capabilities and was able to capture the essential features of the polyps effectively, even on unseen data. Training solely on CycleGAN-generated synthetic data leads to high test performance, but poor generalization to external validation data indicates a severe overfitting issue. The model likely learns artifacts specific to synthetic images and struggles to translate this knowledge to real-world data. The diffusion-based synthetic data led to better generalization than CycleGAN, but still underperforms on external validation compared to real or augmented data. This suggests diffusion models create higher-quality synthetic images, but further tuning might be needed to ensure the synthetic data mimics real-world variability more accurately. The inclusion of synthetic data allows for significant improvement in both training and generalization compared to baseline, whereas combining real and pseudosynthetic data outperforms the other training experiments. Synthetic data helps enhance performance, but cannot replace real data alone. While synthetic data is useful for improving training performance, care must be taken to avoid overfitting to synthetic features, as seen in the external validation results of CycleGAN-only training. Further research should explore refining synthetic data generation techniques to better reflect real-world variability.

Mode collapse is a common issue in Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) where the generator, instead of producing diverse outputs, repeatedly generates limited variations of a few specific outputs. This occurs because the generator learns to focus on producing examples that repeatedly fool the discriminator, but these examples represent only a small portion of the overall data distribution. As a result, the generator fails to capture the full diversity of the target data, leading to outputs that lack variety. This problem can be particularly detrimental in tasks where diversity is essential, such as image generation or data synthesis. When mode collapse happens, the model essentially "cheats" by sticking to a few types of data points that consistently trick the discriminator, rather than learning the complete distribution of the dataset. Several techniques, such as improving the training dynamics between the generator and discriminator, using regularization, or employing different loss functions, have been proposed to mitigate mode collapse, but it remains a challenge in GAN development [

34]. In our analysis, CycleGAN-generated data faced challenges related to mode collapse, producing limited variations that reduced dataset diversity and led to overfitting. This lack of variability caused the model to learn synthetic artifacts and not clinically relevant features, weakening generalization to external datasets. In contrast, diffusion-based models generated more diverse and anatomically realistic samples and better mimicking real-world variability. These improvements enhanced model robustness and supported more reliable performance in external validation. Recent progress in diffusion-based models has overcome the mode collapse issue, producing diverse, high-quality images that outperform GANs. Despite its effectiveness in generating varied images, this method incurs high computational costs for training and inference [

35]. Diffusion based data generation required approximately 2 times more computational resources (determined time-wise) than GANs due to iterative denoising steps involved in sample generation. To scale this method in resource constrained environments, we suggest making use of pre-trained diffusion models for transfer learning, reduced resolution training, and distributed computing frameworks. These approaches can lower computational costs while preserving performance.

The external validation dataset CVC-Colon-DB was selected due to its widespread use in polyp segmentation research and its inclusion of diverse polyp shapes, sizes, and textures. However, it may not fully capture the heterogeneity observed in clinical settings, particularly variations related to patient demographics, endoscopic equipment, or imaging protocols. This limitation highlights the need for future studies to validate models using multicenter datasets to ensure broader generalizability and clinical applicability.

Our work made use of a modified U-Net architecture, chosen for its proven efficacy in medical image segmentation. Although suitable as a baseline, other architectures (e.g., transformers or attention-based models – attention-based U-nets) might achieve better performance or show different responses to synthetic and pseudosynthetic data. The choice for this model is to emphasise the differences in the techniques used, as using a more complex architecture can only exhibit minor differences in the techniques. Comparing multiple architectures would be a valuable step toward more complex conclusions, which are architecture-neutral [

36].

Future research should focus on integrating additional capabilities into U-Net models, such as real-time pathology detection when incorporated into endoscopy systems. This would enable endoscopists to receive immediate feedback or alerts for detected polyps during live procedures, significantly enhancing clinical workflow. Beyond detection, there is a substantial opportunity to extend the application of AI models to post-detection tasks, including polyp classification (e.g., benign vs. malignant), size estimation, and even recommending optimal treatment pathways based on detected abnormalities.

5. Conclusion

This study is among the first to systematically evaluate the impact of synthetic data and pseudosynthetic data—our coined term for data that simulates image variability as if obtained from multiple endoscopies—on enhancing the diagnostic accuracy of deep learning models for colon polyp detection. We investigated and confirmed the potential of pseudosynthetic and synthetic data as effective tools to address the scarcity and lack of diversity in real-world datasets, enhance model generalization through data augmentation, and address ethical issues related to patient privacy in AI-assisted diagnostic environments. Our experiments demonstrated that the U-Net model performs better when trained on synthetic and pseudosynthetic data than when trained solely on real data, highlighting the importance of extensive and diverse training datasets in the field of digestive endoscopy. Notably, models trained exclusively on pseudosynthetic data outperformed those trained on a mix of synthetic and pseudosynthetic sources.

Furthermore, aligning with findings from other studies, models trained on synthetic data generated using diffusion algorithms showed superior performance compared to those trained on data produced by GANs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.-Ș.M. and D.-E.D.; methodology, A.-C.I. and M.-Ș.M.; software, A.-C.I.; formal analysis, D.-E.D.; investigation, A.M.F.; resources, I.I. and A.M.F.; data curation, I.I.; writing—original draft preparation, A.-C.I.; writing—review and editing, I.I. and A.M.F.; supervision, M.-Ș.M. and D.-E.D.; project administration, A.-C.I.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All datasets used in this study were curated, deidentified by the publisher, and appropriately cited within the text. The datasets, including the open source resources PolypGen and Kvasir-SEG, were utilized in accordance with their respective usage guidelines.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Morgan, E.; Arnold, M.; Gini, A.; Lorenzoni, V.; Cabasag, C.J.; Laversanne, M.; Vignat, J.; Ferlay, J.; Murphy, N.; Bray, F. Global burden of colorectal cancer in 2020 and 2040: Incidence and mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN. Gut 2023, 72, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrow, L.; Greenwald, B. Healthy food choices, physical activity, and screening reduce the risk of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterol Nurs 2022, 45, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelmi, M.; Burkhart, A.; Netzer, P. Kolonkarzinom: How can we improve prevention? Ther Umsch 2021, 78, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, B.A.; Noujaim, M.; Roper, J. Cause, epidemiology, and histology of polyps and pathways to colorectal cancer. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2022, 32, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, O.F.; Soares, A.S.; Mazomenos, E.; Brandao, P.; Vega, R.; Seward, E.; Stoyanov, D.; Chand, M.; Lovat, L.B. Artificial intelligence and computer-aided diagnosis in colonoscopy: Current evidence and future directions. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019, 4, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Xin, L.; Zhu, S.; et al. Risk factors related to polyp miss rate of short-term repeated colonoscopy. Dig Dis Sci 2023, 68, 2040–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heresbach, D.; Barrioz, T.; Lapalus, M.G.; et al. Miss rate for colorectal neoplastic polyps: A prospective multicenter study of back-to-back video colonoscopies. Endoscopy 2008, 40, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leufkens, A.M.; van Oijen, M.G.; Vleggaar, F.P.; et al. Factors influencing the miss rate of polyps in a back-to-back colonoscopy study. Endoscopy 2012, 44, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herszényi, L. The "difficult" colorectal polyps and adenomas: Practical aspects. Dig Dis 2019, 37, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glissen Brown, J.R.; Mansour, N.M.; Wang, P.; Chuchuca, M.A.; Minchenberg, S.B.; Chandnani, M.; Liu, L.; Gross, S.A.; Sengupta, N.; Berzin, T.M. Deep learning computer-aided polyp detection reduces adenoma miss rate: A United States multicenter randomized tandem colonoscopy study (CADeT-CS trial). Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022, 20, 1499–1507e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, I.; Vinsard, D.G.; Jodal, H.C.; Løberg, M.; Kalager, M.; Holme, Ø.; Misawa, M.; Bretthauer, M.; Mori, Y. Artificial intelligence for polyp detection during colonoscopy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy 2021, 53, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, L.; Yan, X.; Liu, C.; Guo, C.; Cai, B. Effects of AI-assisted colonoscopy on adenoma miss rate/adenoma detection rate: A protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2022, 101, e31945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagström, R.M.; Bulut, M. Artificial intelligence-assisted detection and characterization of colorectal polyps. Ugeskr Laeger 2023, 185, V09220521. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Williamson, S.M.; Prybutok, V. Balancing privacy and progress: A review of privacy challenges, systemic oversight, and patient perceptions in AI-driven healthcare. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaf, R.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. Springer 2015, 234, 241. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.Y.; Park, T.; Isola, P.; Efros, A.A. Unpaired image-to-image translation using cycle-consistent adversarial networks. IEEE Int Conf Computer Vision (ICCV) 2017, 2223, 2232. [Google Scholar]

- Isola, P.; Zhu, J.Y.; Zhou, T.; Efros, A.A. Image-to-image translation with conditional adversarial networks. IEEE Conf Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 2017, 1125, 1134. [Google Scholar]

- Jha, D.; et al. Polyp-DDPM: A diffusion probabilistic model for polyp detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.04031, 2024.

- van Liere, E.L.S.A.; Jacobs, I.L.; Dekker, E.; Jacobs, M.A.J.M.; de Boer, N.K.H.; Ramsoekh, D. Colonoscopy surveillance in Lynch syndrome is burdensome and frequently delayed. Fam Cancer 2023, 22, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.Z.; Devan Nair, H.; Saboo, A.; Lee, S.C.L.; Gu, X.; Auckloo, S.M.A.; Tamang, S.; Chen, S.J.; Lowe, R.W.; Strugnell, N. A single-centre audit: Repeat pre-operative colonoscopy. ANZ J Surg 2022, 92, 2571–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, D.; Ali, S.; Johansen, H.D.; et al. Kvasir-SEG: A segmented polyp dataset. arXiv preprint arXiv:1911.07069v1, 2019.

- Jha, D.; Riegler, M.A.; Johansen, H.D.; Halvorsen, P.; de Lange, T. PolypGen: A large-scale polyp generation dataset. arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.04463, 2021.

- Ho, J.; Jain, A.; Abbeel, P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.11239, 2020.

- Keras API Documentation. Available online: https://keras.io/api/ (accessed on [insert date]).

- Kingma, D.P. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6980, 2014.

- Ruby, U.; Yendapalli, V. Binary cross entropy with deep learning technique for image classification. Int J Adv Trends Comput Sci Eng 2020, 9, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson, B.J.; Kitamura, F. Magician’s corner: Performance metrics for machine learning models. Radiology: Artificial Intelligence 2021, 3, e200126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, J.; Sánchez, J.; Vilarino, F. Towards automatic polyp detection with a polyp appearance model. Pattern Recognition 2012, 45, 3166–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rognstad, Ø.B.; Botteri, E.; Hoff, G.; Bretthauer, M.; Gulichsen, E.; Frigstad, S.O.; Holme, Ø.; Randel, K.R. Adverse events after colonoscopy in a randomized colorectal cancer screening trial. BMJ Open Gastroenterol 2024, 11, e001471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Shen, Y.; Xu, J.; Gao, P.; Bing, H. Clear colonoscopy as a surveillance tool in the prediction and reduction of advanced neoplasms: A randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc 2021, 35, 4501–4510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreu, E.; McGuinness, K.; O'Connor, N.E. Synthetic data for unsupervised polyp segmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.08680, 2022.

- Ozkaya, B.; et al. Development and validation of deep learning models for automated polyp segmentation in colonoscopy images. J Digit Imaging 2022. [CrossRef]

- Yousef, R.; Khan, S.; Gupta, G.; Siddiqui, T.; Albahlal, B.M.; Alajlan, S.A.; Haq, M.A. U-Net-based models towards optimal MR brain image segmentation. Diagnostics (Basel) 2023, 13, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, R.; Zhang, D.; Liu, J.; Cheng, C. MSU-Net: Multi-scale U-Net for 2D medical image segmentation. Front Genet 2021, 12, 639930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durall, R.; Chatzimichailidis, A.; Labus, P.; Keuper, J. Combating mode collapse in GAN training: An empirical analysis using Hessian eigenvalues. arXiv preprint arXiv:2012.09673, 2020.

- https://paperswithcode.com/sota/medical-image-segmentation-on-cvc-clinicdb.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).