1. Introduction

The modern technological world creates more and more conveniences for people by offering them wide range of various electronic devices, which emit radio- or micro-waves – non-ionizing electromagnetic fields (EMF). Even though carrying low energy, their elevated levels in the environment are known as electromagnetic pollution and constitute relatively new stress factor for the biosphere as a whole, and a potential health risk for the population in particular. Physical properties, that could determine the biological outcome of an EMF interaction, are the frequency of the EMF wave, its polarization, the exposure duration, the geometry and structure of the object and the absorbed dose. A major parameter used to quantify the radio- and microwave-frequency EMF energy intercepted by biological objects is the Specific Absorption Rate (SAR), W/kg, given as the electromagnetic wave power (in W) that have been absorbed by 1 kg of biological tissue. Another important parameter is the distance between the object and the emitting source not only because it determines the wave intensity at the spot of the object but due to the fact that the physical properties of the EMF are quite different close (near-field) and farther from it (far-field – classic electromagnetic wave).

There are a number of scientific studies on the effects of microwave EMF with different frequencies and intensities on microorganisms, plants, animals, and humans [

1]. The biological effects caused by microwave EMF can be divided into thermal and non-thermal. Thermal effects are a result of the absorption of microwaves at the molecular level, which leads to particle vibrations and consequently heats the matter [

2]. Evidence for non-thermal effects of electromagnetic radiation comes from studies with microorganisms, where a larger number of them was destroyed during irradiation than when heated conventionally (i.e. by heater) to the same temperature [

3]. There are also data showing increased growth of cultures not related to heating [

4]. The mechanisms behind these effects are not fully understood, but it is suggested that they are related to changes in the secondary and tertiary structure of functionally active proteins [

5,

6,

7].

One of the most commonly used frequency bands for domestic, industrial, scientific, and medical purposes is 2.45 GHz. The effect of 2.45 GHz microwave radiation on histology and lipid peroxidation levels in rats was studied [

8]. The animals were exposed to the radiation for 35 days, 2 hours per day with a SAR of 0.14 W/kg. Significant levels of lipid peroxidation were recorded in the liver, brain, and spleen. Histological changes were found in the brain, liver, testes, kidneys, and spleen compared to the control group. Karatopuk found that prolonged irradiation of rats (30 days for one hour per day) with 2.45 GHz EMF led to endothelial damage [

9]. Single- and double-stranded DNA breaks were detected by comet assay in brain cells from rats irradiated for two hours with 2.45 GHz EMF and SAR ranging from 0.6 to 1.2 W/kg [

10]. The effects were prevented by treatment with antioxidants, suggesting a free radical-related mechanism. The effects of 2.45 GHz electromagnetic radiation on the cell redox status were studied using human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells, which had been differentiated into neuron-like cells and peripheral blood mononuclear cells [

11]. They were treated for 2, 24, and 48 hours. Cell viability was reduced after 24-48 hours. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels were significantly increased in the exposed cells compared to the controls at each treatment period. The results showed that neuron-like cells were more prone to develop oxidative stress compared to PBMCs after exposure to 2.45 GHz EMF and undergo activation of an early antioxidant defense response.

The effect of EMF with a frequency band between 1 and 5.9 GHz on

Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast was monitored [

12]. A decrease in cell viability was observed at all applied frequencies. The effect of the treatment directly depended on the distance between the antenna and the sample, that is, the intensity of the radiation. Transmission electron microscopy showed that EMF led to a disruption of the integrity of the cell membrane. When exposing various microorganisms, including yeast, to EMF with a frequency of 2.45 GHz and an amplitude of the electric field of 9.3 kV/m, no effect on cell survival was observed [

13]. However, an increased permeability of the cell membrane for propidium iodide and dextran particles of different sizes was found. Propidium iodide entry was observed in microwave-treated Mycobacterium smegmatis cells, but not in cells conventionally heated to the same temperature as that reached by irradiation. Permeability to fluorescently labeled dextrans of 3 kDa was observed in all cell types, but larger dextran particles (70 kDa) were unable to enter the cells. DNA release from the cells was also observed. Abed et al. found that exposure of

S. cerevisiae cells to microwave radiation at a frequency of 2.45 GHz, 90 W for 1 minute resulted in cell deformation, delayed fermentation, and failure to synthesize toxins [

14]. Low-intensity microwave radiation (dose up to 1.6 W/g and duration up to 120 s) promoted the growth and caused reversible permeabilization of the cell membrane without damaging the cells of

Brettanomyces custersii yeast, isolated from spontaneously fermented rice paste [

15]. Higher intensities led to yeast death, mainly due to irreversible permeabilization and the release of electrolytes and larger vital molecules from the cells.

Yeast are widely used as a model organism, as they combine the experimental advantages of microorganisms and the characteristic features of higher eukaryotes. A comparative analysis of the yeast and human genomes shows conservatism in the genetic pathways responsible for the cellular response to various stress factors, including oxidative stress [

16].

The aim of our study was to explore the short-term effects of irradiation with 2.45 GHz EMF in the near-field, resembling the use of mobile devices, on yeast with a focus on the cell membrane permeability, antioxidant levels and DNA integrity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Yeast Culture Conditions and Sample Preparation

The biological object of this study was yeast cells of the species

Saccharomyces cerevisiae Meyen

ex E.C. Hansen, strain U1, reference number 584 of NBIMCC (National Bank for Industrial Microorganisms and Cell Cultures, University of Chemical Technology and Metallurgy, Sofia, Bulgaria) [

17]. The yeast cells were kindly provided as solid culture, whose medium contained 10 g Yeast extract, 20 g Peptone, 20 g Dextrose (YPD) and 15 g agar diluted in distilled water (d. w.) to 1000 ml, in test tubes by Department of General and Industrial Microbiology, Faculty of Biology, Sofia University “St. Kliment Ohridski”. A liquid culture was prepared by resuspending the agar culture with 1 mL YPD broth, same as above but without agar, followed by inoculating 0.5 mL of this suspension in 50 mL of the YPD medium and incubating at 30 °C, 250 RPM in orbital shaker-incubator ES-20 Grant-bio (Grant Instruments Europe B.V., Amsterdam, The Netherlands) for 24 h. That culture was used as the first inoculum (1.5 mL) in a consecutive series of 24 h cultivations in 60 mL YPD broth (30 °C, 250 RPM) to keep the yeast cells vital and in uniform physiological state throughout the experiments. All cultures were stored at 10 °C after cultivation. Before each experiment fresh cultures were prepared and used directly (without storing) as inoculum (1.5 mL) for the final cultivation (60 mL YPD broth, 30 °C, 250 RPM, 24 h) to obtain the yeast cells for treatment. The

S. cerevisiae cells from those cultures were washed with d. w. by centrifugation at 4200 RPM for 10 min (MPW-360, Mechanika Precyzyjna, Warsaw, Poland) and subsequent resuspending, three times at total, and concentrated finally to 100 mg FW/mL suspension (in d. w.). The prepared suspension was distributed in 2 mL tubes which were used as samples for treatment.

2.2. Treatment Conditions

The 2 mL 100 mg FW/mL yeast suspensions were transported to semi-anechoic chamber where they were irradiated with 2.45 GHz continuous wave EMF, emitted by a dipole antenna with length of 3 cm and output power level of −10 dBm (100 μW), at 2 distances from the antenna: 2 and 4 cm, and for 2 time periods: 20 and 60 min, in the following combinations:

2 cm and 20 min;

4 cm and 20 min;

4 cm and 60 min.

For antenna shorter than half of the EMF wavelength (λ) the near-field region extends up to a λ from it. It is further divided into two zones: reactive and radiative. The border between them lies λ/2π away from the antenna. This means that in the described setup both applied distances were in the near-field since for 2.45 GHz EMF wave λ in air is 12.23 cm, the antenna length (3 cm) being shorter than λ/2 = 6.12 cm, while the 2 cm spot is just at the transition between the reactive and radiative zones occurring at 1.95 cm, and the 4 cm spot fall well into the radiative zone of the near-field.

For each irradiation setup the absorbed EMF dose was estimated by calculating SAR from the microwave heating of the samples during short, 30-seconds exposure to minimize the effect of heat dissipation. The calculation takes into account the temperature difference (ΔT) between the temperature recorded right after the end of treatment (T

max) and the initial temperature – room temperature (RT), the time duration of the exposure in seconds (t = 30 s) and the specific heat capacity at constant pressure (c

p) value used in the calculations is that for liquid water – 4184 J·kg

−1·°C

−1, and is described by the formula:

where:

The sample temperatures were monitored by infrared camera FLIR E5 and the thermographs were analyzed by SmartView Classic 4.4 software (Teledyne FLIR LLC, VA, USA).

Samples that stayed in the semi-anechoic chamber but were wrapped in aluminum foil to shield them from the EMF were used as unexposed controls. Further, for each EMF irradiation variant two additional conditions were examined to account for the effect of microwave heating: samples held at RT and samples undergoing the temperature difference (ΔT), characteristic for the concrete full-term EMF treatment, by conventional heating in dry block PCH-2 Grant-bio (Grant Instruments Europe B.V.). In fact, for the irradiated samples the ΔT results from the balance between the energy inflow due to absorbed EMF and the outflow due to ambient heat transfer to the environment. The ΔT for the conventional heating was applied at equal portions per minute, that is a constant temperature gradient (ΔT/t) was used. Both sample variants were prepared right after the EMF exposure since Tmax could be obtained only at its end. Room temperature incubation and conventional heating were done for the time duration of the particular EMF treatment.

2.3. Determination of Cellular Effects of EMF and Heating

Effects of the EMF exposure and the corresponding conventional heating on

S. cerevisiae were examined by probing cell membrane permeability, antioxidant status and genetic material integrity. The permeability of the membrane was determined by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm (A

260) of the d. w. suspension medium after cell sedimentation by centrifugation at 12000 RPM for 2 min (Minispin, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). Thus measured A

260 corresponds to the magnitude of the leakage of UV-absorbing substances from the cells during and after treatment, more specifically – nucleic acids since A

260 is a measure of their relative concentration [

18].

The cell antioxidant status was evaluated by the reduced glutathione (GSH) content in and Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity (TEAC) of cell lysates. They were prepared by mechanical disintegration of the cells with 0.666 g quartz sand added to 1 mL of the yeast suspensions at 2700 RPM for 10 min in Digital Disruptor Genie (Scientific Industries Inc., Bohemia, NY, USA). The lysates were centrifuged at 12000 RPM for 2 min (Minispin) and the supernatant was extracted for analyses. GSH content was determined by A

412 of TNB chromophore produced by the reaction of GSH with DTNB (D8130, Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) [

19]. Reduced glutathione (120000050, Thermo Scientific Chemicals, MA, USA) was used as standard in 0-20 μg/mL concentration range. TEAC was established following the ABTS (194430, Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) radical cation decolorization assay improved by Re et al. measuring A

734 [

20]. Trolox (218940010, Thermo Scientific Chemicals, MA, USA) was used as standard in concentration 0-17.5 μmol/L concentration range. All photometric analyses were performed with ONDA UV-21 spectrophotometer (Giorgio Bormac S.r.l., Carpi, Italia).

DNA integrity were determined by single cell gel electrophoresis in alkaline conditions as per Azevedo et al. and defined as yeast comet assay [

21]. Images of the comets were obtained by Axioscope 5 microscope, provided with Colibri 3 imaging system and Axiocam 202 mono camera, and ZEN 3.4 (blue edition) program (Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany). The images were analyzed with CometScore 2.0 software (TriTek Corp., USA). The following parameters were chosen as measures of DNA damage:

comet tail length (TL, pixels) – comet head diameter subtracted from the overall comet length;

comet tail DNA percentage (TDC, %) – total comet tail intensity divided by the total comet intensity, multiplied by 100;

comet olive tail moment (OTM, arb. u.) – summation of each tail intensity integral value, multiplied by its relative distance from the center of the head (the point at which the head integral is mirrored), and divided by the total comet intensity [

22].

All analyses were performed 2 h after treatments finished.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

The data presented are mean with standard error of mean (SEM) values calculated from 4 independent experiments for the first EMF treatment setup, 2 – for the second and 3 – for the third. Two-way ANOVA with factors experimental variant and experimental repetition, followed by Holm-Sidak test, was used to differentiate the statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) among variants from those due to variations among individual experiments. SigmaPlot 11 program (Systat Software, Inc., USA) was used. The raw data can be found in

Table S1.

3. Results

3.1. SAR and Microwave Heating

The SAR along with information about the microwave heating of the 2 mL 100 mg FW/mL yeast suspensions treated with 2.45 GHz EMF for all the exposure conditions are presented in

Table 1.

The SAR at 4 cm was just 5 % lower than that at 2 cm – both around 130 W/kg. While the SAR was almost the same the microwave heating was significantly different among the applied setups. At the position nearest to the antenna the temperature rose the most – by 23 °C to Tmax of 44 °C which is well above the temperature optimum for growth of the yeast strain used (30 °C) and might have easily induced heat stress. When the distance increased twice while the duration stayed unchanged (20 min) the temperature difference dropped almost threefold to 8 °C and the reached Tmax (32.5 °C) was near the optimum. Increasing the treatment period three times at the 4 cm distance raised the temperature amplitude by 58 % to 12.5 °C. It is important to note that the room temperatures were practically the same for all setups.

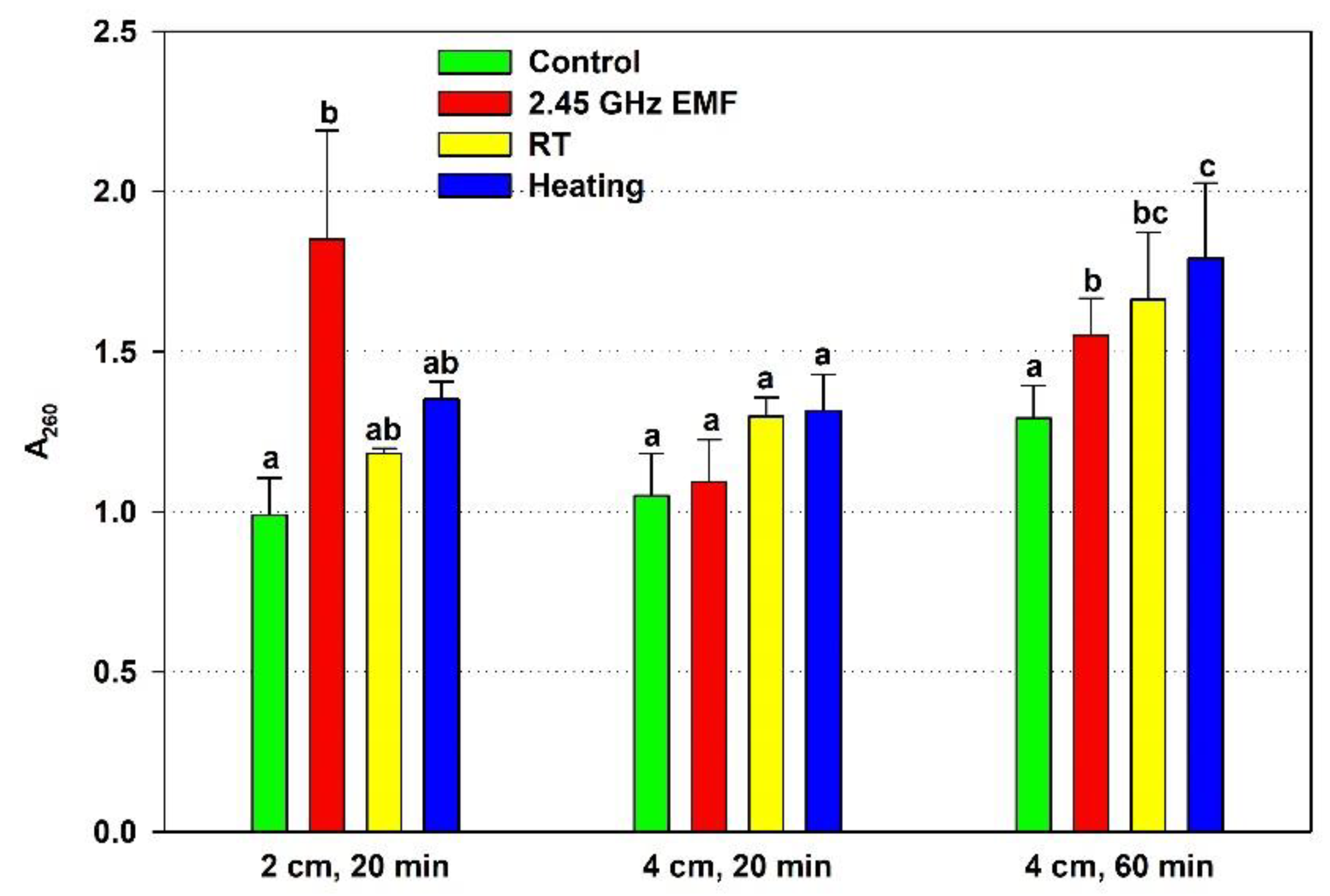

3.2. Cell Membrane Permeability

The effect of 2.45 GHz EMF on the yeast cell membrane permeability was assessed by the leaked from the cells nucleic acids, measured as A

260, and was compared to the effect of conventional heating causing the temperature rise registered for the particular exposure condition (

Figure 1). The 20-minute irradiation at 2 cm, having, increased the cell leakage almost two-fold (by 86 % on average) while the heating (ΔT = 22.8 °C) alone caused insignificant 16 % rise. The 4-cm, 20-minute EMF exposure did not change the membrane permeability relative to the not irradiated control, nor did the corresponding conventional heating (ΔT = 7.9 °C) compared to the RT sample. The 60-minute irradiation elevated the membrane permeability mildly but significantly by 15 % on average. The corresponding conventional heating (ΔT = 12.5 °C) failed to show significant rise – just 8 %.

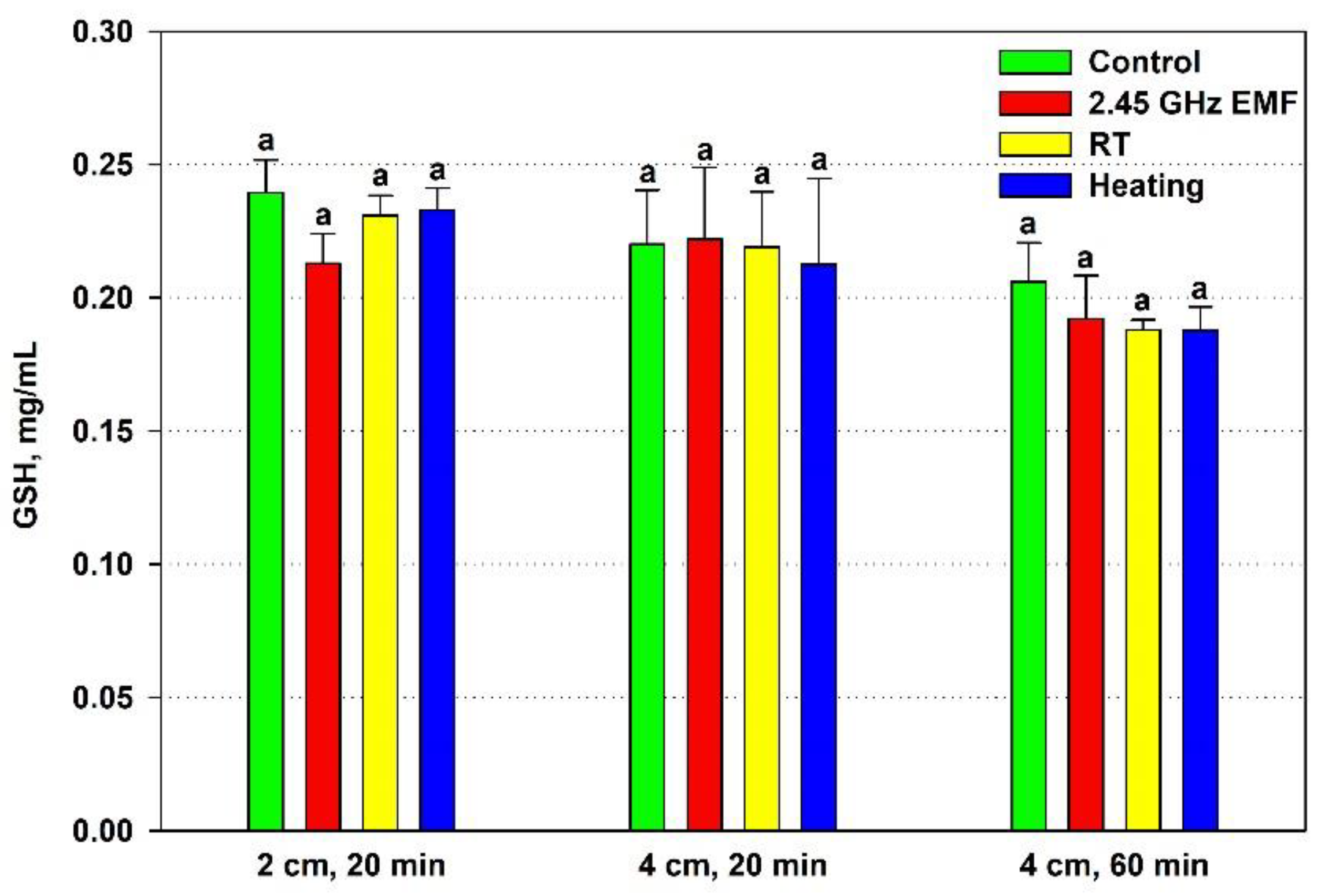

3.3. Cell Antioxidant Status

The effect of the EMF exposure on the yeast cell antioxidant status was assessed by the GSH content and TEAC comparing it to the effect of the conventional heating. GSH concentration did not change significantly at any of the applied experimental conditions (

Figure 2). Nonetheless, a clear deviation was registered after the 20-minute irradiation at 2 cm distance when GSH declined by 11 % on average relative to the control. For comparison, the corresponding heating lowered mean GSH value by just 1 % in relation to the RT sample.

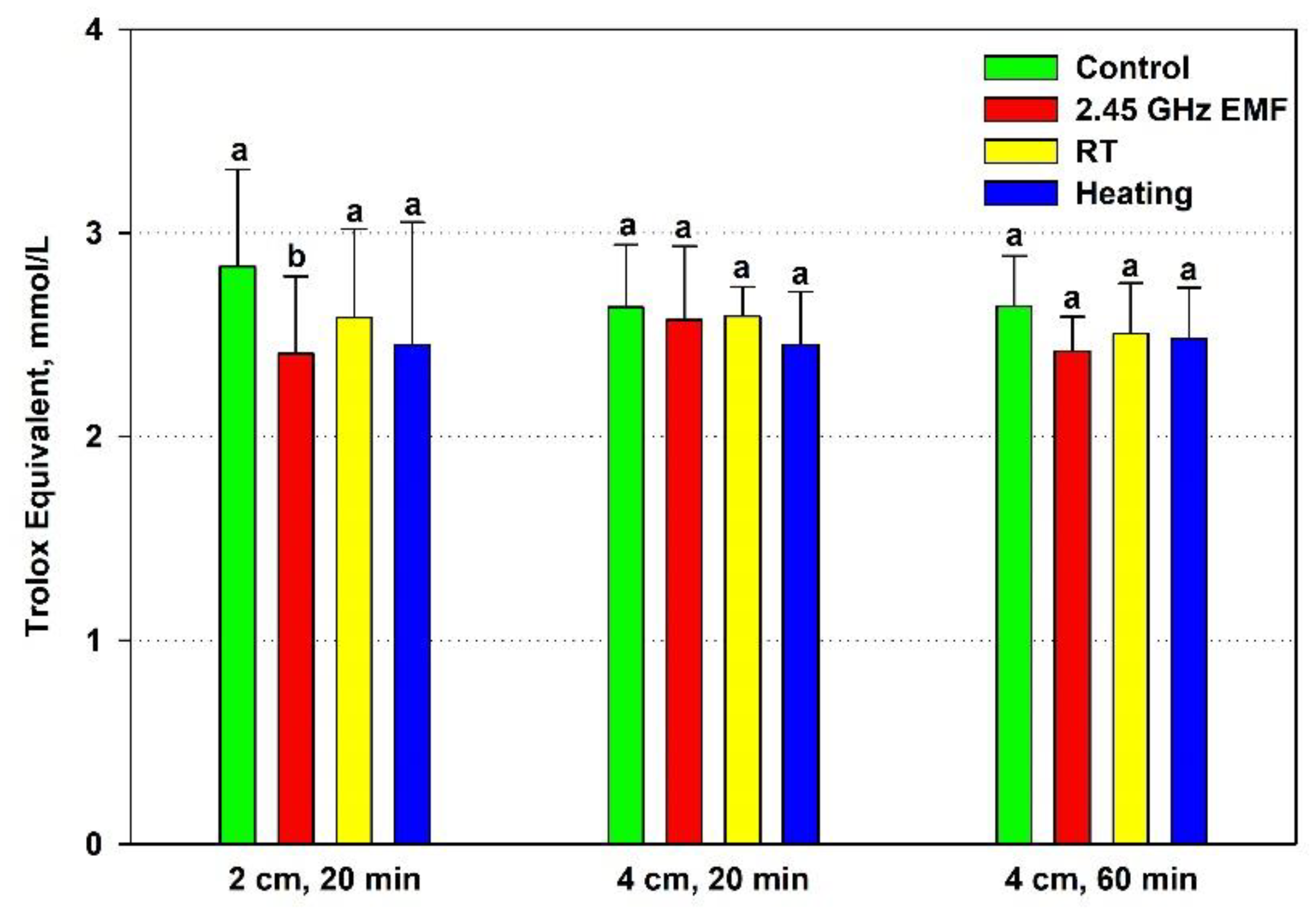

The TEAC of the yeast cells decreased significantly during the 2-cm, 20-minute irradiation (15 %) but not under heating by 22.8 °C (

Figure 3). The 4 cm distance and temperature rises by 7.9 °C and 12.5 °C did not alter antioxidant activity in a significant way.

There is a clear correlation between the lowered antioxidants and the increased permeability at the 2 cm (132 W/kg) EMF treatment for 20 minutes suggesting a common factor determining them. An oxidative stress could have occurred at that exposure. The generated oxidants partially depleted the antioxidants while simultaneously oxidizing lipids causing membrane fluidization or even disintegration leading to the high leakage. Furthermore, the suggested oxidative stress seems to be unrelated to the temperature rise during irradiation since it does not occur under conventional heating. Interestingly, the permeabilization at 4 cm (126 W/kg) exposure for 60 minutes seems to have different mechanism because it is not related to the antioxidant status but yet heating alone have not an influence on it.

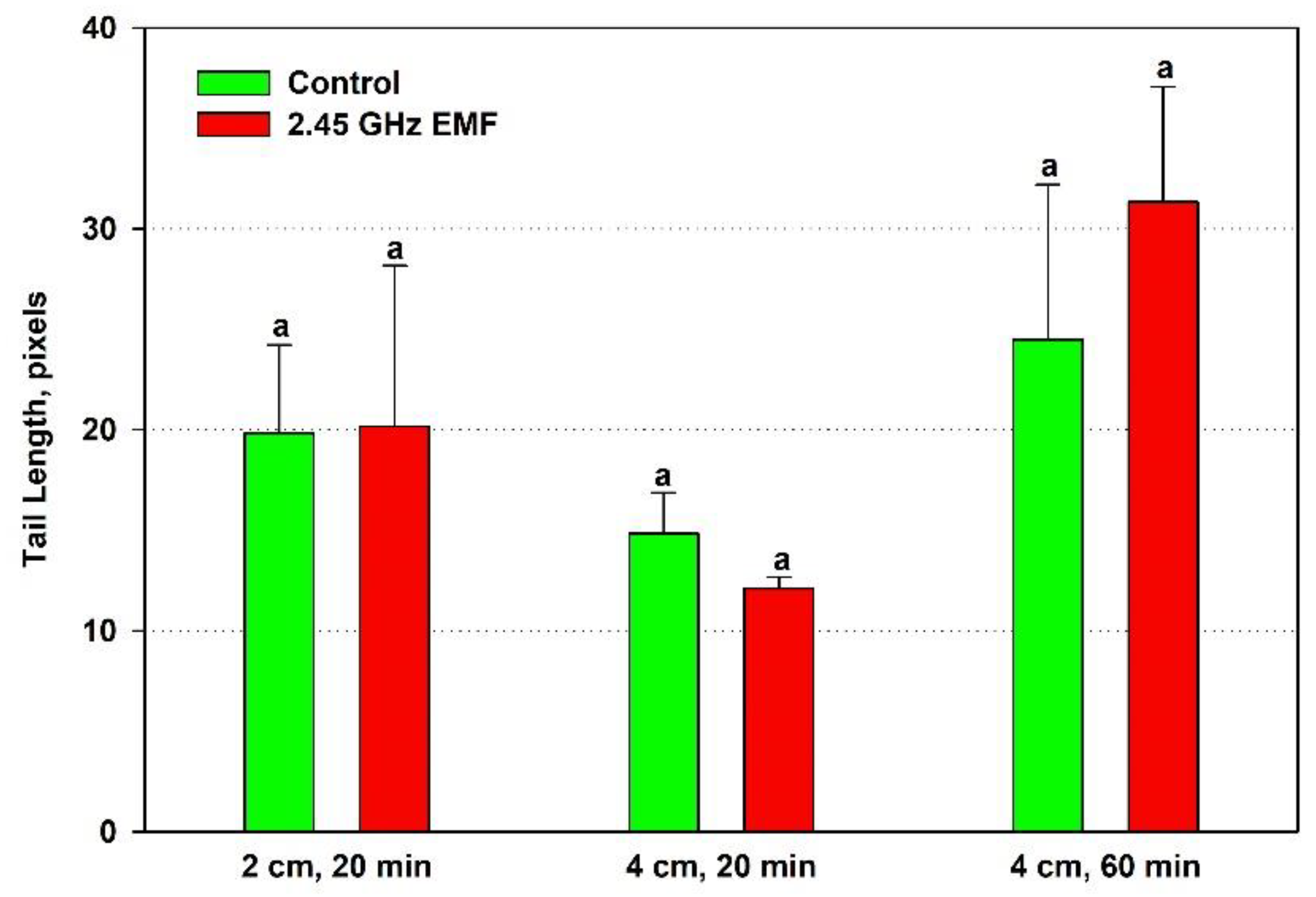

3.4. DNA Integrity

The effect of the EMF exposures on the yeast DNA was assessed by three comet assay parameters. Tail length increased just by 2 % from the control levels on average after the 20-minute treatment at 2 cm while at 4 cm it decreased by 19 % (

Figure 4). At the 60-minute exposure the biggest difference between the mean values for control and treated samples was observed – 28 % in favor of the EMF. However, all those changes were not statistically significant.

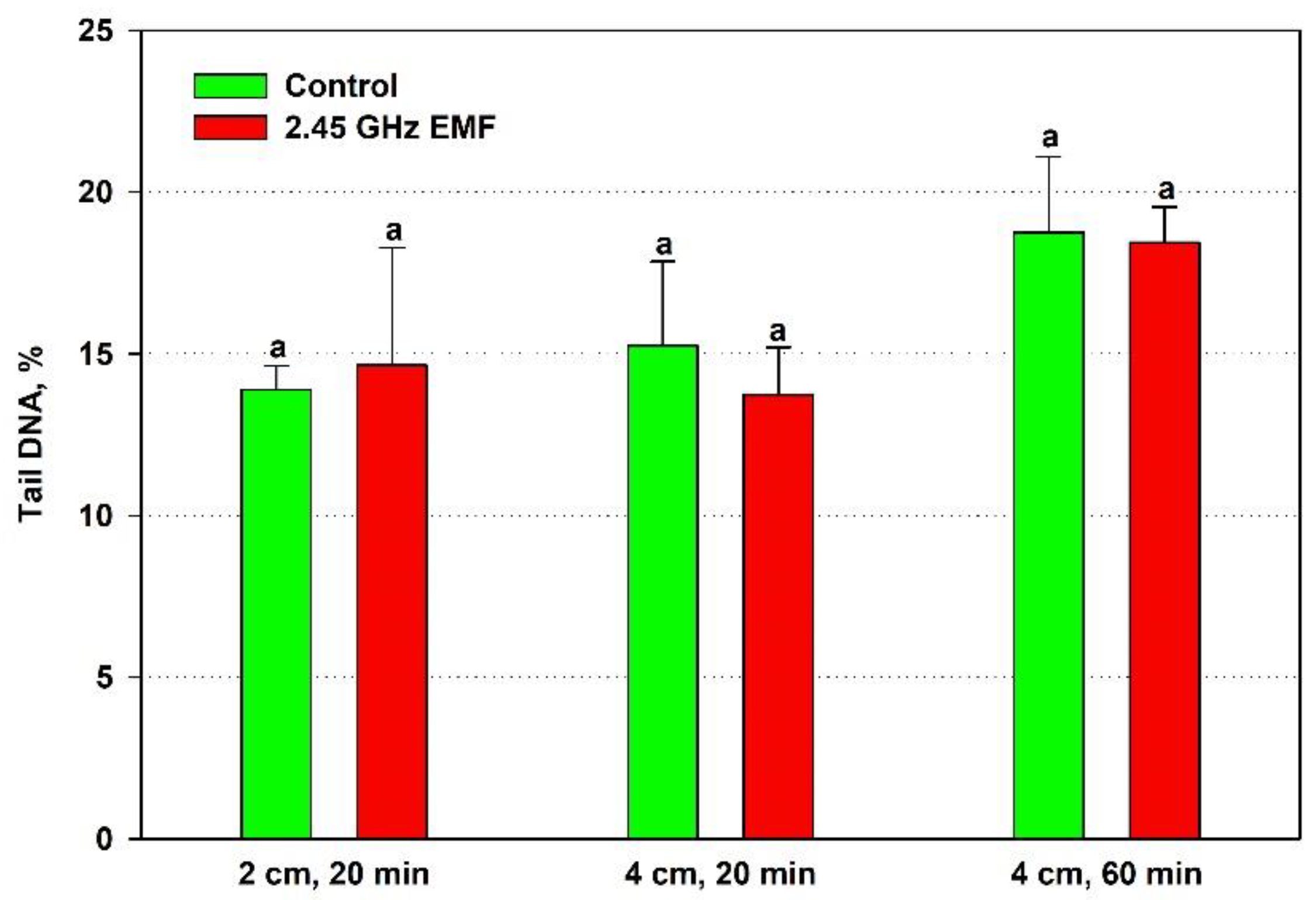

The alterations in relative DNA content in the comet tails were even less pronounced than those in tail length, so it is not surprising that no statistically significant differences were revealed for it either (

Figure 5). The biggest discrepancy was found at 2 cm, 20 min irradiation – the average levels of the EMF-exposed samples were 10 % lower than controls.

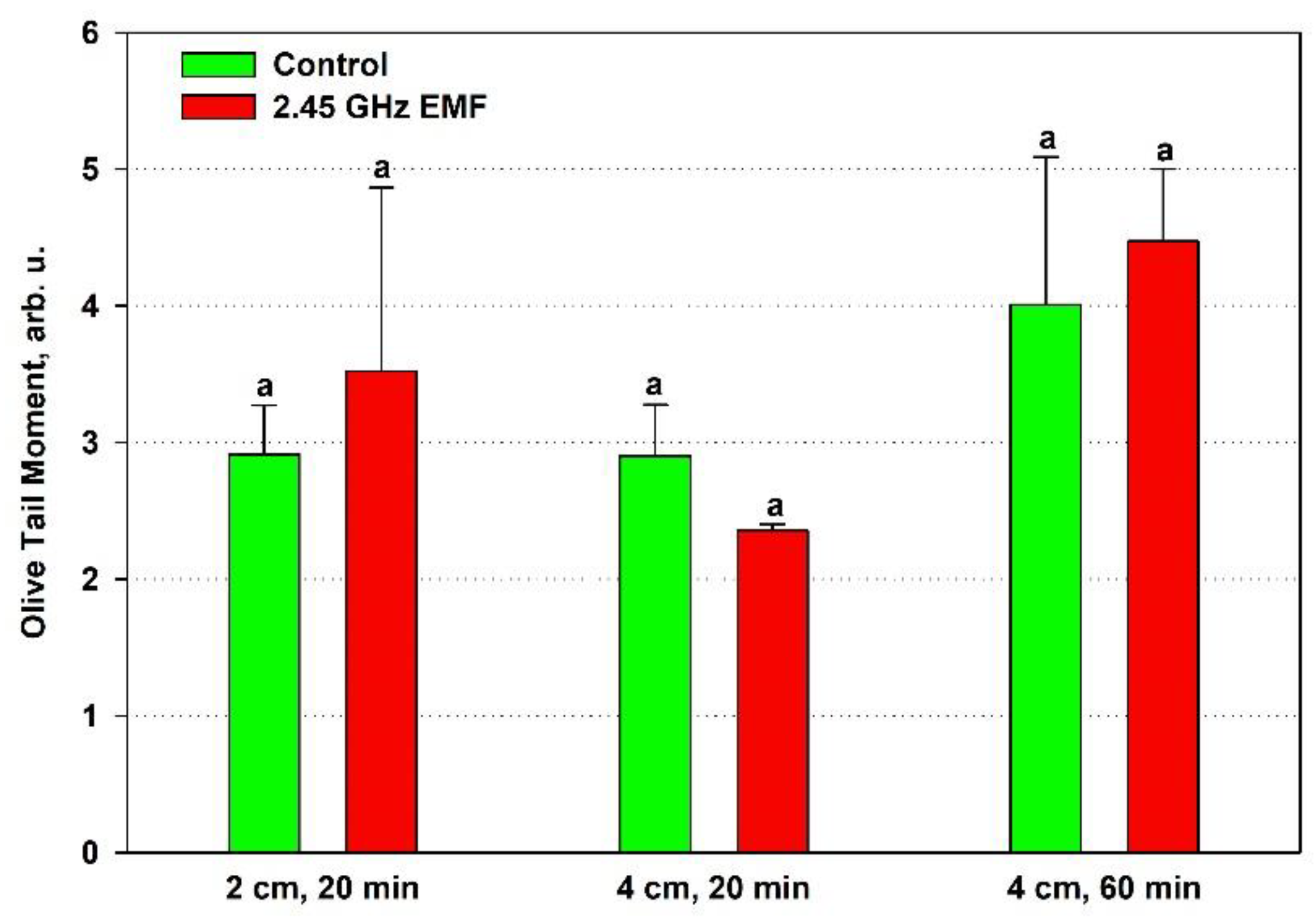

Olive tail moment displayed an average increase by 21 % at 2 cm and 12 % at 4 cm for the 60-min treatment but a decrease by 19 % at the shorter period comparing to the respective control (

Figure 6). Despite that OTM is expected to be the most sensitive of the three comet assay parameters since it summarizes information of the other two, the data variance was not improved and random sampling variability could not be excluded as a reason for the observed differences.

Despite the lack of statistical significance of the differences obtained in the studied comet assay parameters, a trend towards an increased amount of DNA damages was observed in the samples placed 2 cm away from the antenna that absorbed 132 W/kg during the shorter 20-min period and those at 4 cm distance (126 W/kg) for 60 minutes. In the first case, it was expected, as that was the only treatment condition in which strong oxidative stress was implied by the high membrane permeability and the antioxidant activity drop. It is interesting that at the lower SAR irradiation the shorter 20-min period indicated increased DNA integrity as if repair mechanisms were stimulated. However, that stimulation should have been transient since the longer period seemed to allow for accumulation of DNA breaks, that the cells' repair systems were unable to fix.

4. Discussion

The most profound EMF effect revealed by our study is the strong disruption of cell membrane integrity at 132 W/kg as demonstrated by the large nucleic acids release from the yeasts. It is known that significant release of intracellular substances can only be observed after reversible or irreversible permeabilization and that the type and amount of these substances depend on the defects in the cell membrane [

23,

24]. Our finding is in concordance with previous reports of increased membrane permeability under EMF irradiation [

12]. The corresponding conventional heating failed to demonstrate significant leakage hinting at non-thermal mechanism of EMF action on membrane integrity. Such mechanism was implied by Nguyen et al. describing a possible EMF-induced mechanical disturbance altering the membrane tension permeability, and thus enhancing degree of membrane trafficking through lipid bilayer [

25]. Researchers have reported non-thermal effects of EMF on other biological processes as well: glucose uptake by yeast cells [

26], cell proliferation [

4] and cell growth [

27].

Alternatively, the vast discrepancy between the observed results for heating and EMF might not reveal a presence of non-thermal effects under EMF, but could be explained by the lack of effects under conventional heating. The lack of significant permeabilization under heating to 44 °C might seem puzzling by itself since at that temperature protein denaturation and increased fluidity of cell membranes are highly plausible [

28,

29]. However, it should be reminded that the temperature gradient provided by the heater was constant leading to a linear temperature increase meaning that the 44 °C is reached just at the end of the treatment and not sustained for more than a minute. On the other hand, it is highly possible that the temperature rise caused by the EMF radiation was not linear throughout the exposure period – the maximal temperature could be reached until a thermal equilibrium with the environment is reached before the treatment end followed by a prolonged period during which that temperature is maintained. If that was the case the effective temperature during exposure is definitely higher than during conventional heating which could explain the strong EMF effect in terms of a thermal mechanism. It is well known that temperature increases membrane fluidity leading to defects through which substances are released [

30,

31,

32]. Another highly possible supposition is that yeast autolysis developed – a process characterized by a loss of cell membrane permeability at first, alteration of cell wall porosity, hydrolysis of cellular macromolecules by endogenous enzymes, and subsequent leakage of the breakdown products into the extracellular environment, known to be induced by elevated temperatures (40–60 °C) [

33]. Indeed, for a particular temperature difference microwave heating of a water-based solution is faster than conventional heating because it is based on direct transfer of EMF energy at the molecular and the nano-cluster scale of water structure without depending on heat transfer [

34]. That defines microwave heating as internal as opposed to the conventional external heating. Moreover, microwave heating has characteristic properties such as selectivity, hot spots formation, local effects, and nonuniformity. All those make imitating it by conventional methods, i.e. external heat transfer, practically impossible. However, in the irradiation setup applied in the study a relatively uniform EMF heating of the samples could be assumed since the tubes diameter (1 cm) was smaller than the penetration depth of the 2.45 GHz microwaves – 1.8 cm for water at 25 °C, and increasing with temperature. It was previously proposed that internal ‘micro’-thermal effects specific to microwave radiation may underpin specific biological effects on membranes, proteins, enzyme activity as well as cell death, that cannot be explained by virtue of temperature increases alone [

35].

The 60-min exposure with 126 W/kg led to a distinct increase in the release of UV-absorbing components from the cells, but much less pronounced than the 132 W/kg treatment, while the corresponding conventional heating did not cause significant leakage yet. The maximum temperature reached was 36.6 °C, which is within the physiological range for yeast growth not implying autolysis but specific EMF effect on the membrane. Similar finding was reported by Ahortor et al. when the electrical component of an electromagnetic field at a frequency of 2.45 GHz increased the membrane permeability of yeast cells to certain molecules, such as propidium iodide, but thermal treatment at 37 °C did not [

13]. However, the leakage under 60-min irradiation could also be explained by a higher effective temperature under microwave than conventional heating due to a faster temperature rise to maximal temperature. Moreover, even if the temperature rise could not induce membrane defects big enough to compromise integrity, it definitely can boost the quantity of the leaked substances since they are released by diffusion which depends exponentially on temperature [

36].

Stress at the cellular level is often manifested as imbalance between oxidants, mainly ROS, and antioxidants in favor of the former – oxidative stress [

37]. Therefore we examined the quantity of intracellular antioxidants – reduced glutathione and total antioxidant capacity of yeast cells. The only proven effect was observed for 132 W/kg EMF where TEAC dropped while a trend towards a decreased amount of GSH in the cells was also noticed. Both observations could be explained by oxidative stress developing under irradiation. On the other hand, the 44 °C temperature achieved during conventional heating did not affect neither TEAC, nor GSH despite the fact that increased levels of ROS have been observed in yeast cells subjected to heat stress [

38]. Elevated temperatures can impair mitochondrial function, leading to increased electron leakage from the respiratory chain and subsequent ROS production [

39]. Therefore, the observed antioxidant status changes in the yeast suspensions induced specifically by the EMF might be due to non-thermal effects. Indeed, oxidative stress is one of the proposed non-thermal mechanisms of action of EMF on organisms [

40]. However, a higher heating during irradiation could not be ruled out as a plausible cause for the effect yet.

Our study failed to demonstrate a clear genotoxic effect of the applied EMF. Just weak tendencies towards increased DNA damage at 132 W/kg for 20 min and at 126 W/kg for 60 min were indicated. Some previous studies have found potential genotoxicity of 2.45 GHz EMF under certain treatment conditions in specific cell types [

41], while others have not found a damaging effect [

42,

43]. The generated reactive oxygen species during irradiation might underlie such DNA damage [

44]. Different cell types exhibit different DNA sensitivity to EMF. Neuronal-like SH-SY5Y cells show increased levels of ROS and mitochondrial dysfunction under exposure, indicating increased sensitivity compared to peripheral blood mononuclear cells [

11]. In a study of 905 MHz radiation on different strains of

S. Cerevisiae, it was found that strains deficient in DNA repair mechanisms showed significantly reduced colony growth compared to wild-type strains, suggesting DNA breaks [

45]. There is evidence that carrier frequency EMF with a typical modulation structure of a GSM signal affect the DNA in the human trophoblast cells, causing a transient increase in the level of DNA fragmentation that disappears within 30 to 120 min [

46]. So since our samples were incubated for 2 h after irradiation at room temperature prior to analysis, transient DNA damages could have been fixed by the repair mechanisms thus explaining the inconclusive results obtained.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Raw data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.A.; methodology, B.A., M.P., M.K., G.A. and N.A.; software, M.P.; validation, B.A. and M.P.; formal analysis, M.P.; investigation, B.A., M.P., M.K., G.A. and N.A.; resources, B.A., M.K., G.A. and N.A.; data curation, M.P. and N.A.; writing—original draft preparation, B.A. and M.P.; writing—review and editing, B.A., M.P., M.K., G.A. and N.A.; visualization, M.P.; supervision, B.A.; project administration, B.A.; funding acquisition, B.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Bulgarian National Science Fund at the Ministry of Education and Science, Bulgaria, grant number KP-06-M61/2 from 13th December 2022 “Investigation of the mechanisms of impact of electromagnetic fields with a frequency of 2.45 GHz, emitted by wireless communication systems, on yeast” and Bulgarian Ministry of Education and Science under the National Program „Young Scientists and Posdoctoral Students – 2“. The APC was funded by KP-06-M61/2.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ventsislava Petrova from the Department of General and Industrial Microbiology, Faculty of Biology, Sofia University “St. Kliment Ohridski”, Bulgaria for kindly providing the yeast agar cultures and to Assist. Prof. Dr. Mariyana Georgieva from Department “Molecular Biology and Genetics”, Laboratory “Regulation of gene expression”, Institute of Plant Physiology and Genetics at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, Bulgaria for advising on the alkaline comet assay.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| A260

|

Absorbance at 260 nm |

| A412

|

Absorbance at 412 nm |

| A734

|

Absorbance at 734 nm |

| ABTS |

2,2'-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) |

| DTNB |

5,5-dithio-bis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (Ellman's Reagent) |

| d. w. |

Distilled Water |

| EMF |

Electromagnetic Field/s |

| FW |

Fresh Weight |

| GSH |

Glutathione (reduced form) |

| ROS |

Reactive oxygen species |

| RPM |

Revolutions Per Minute |

| RT |

Room temperature |

| SAR |

Specific Absorption Rate |

| TEAC |

Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity |

| Tmax

|

Temperature recorded right after the end of treatment |

| YPD |

Yeast extract, Peptone, Dextrose |

| ΔT |

Temperature difference between Tmax and RT |

| λ |

Wavelength |

References

- Wilke, I. Biological and Pathological Effects of 2.45 GHz Radiation on Cells, Fertility, Brain, and Behavior. Umwelt, Medizin, Gesellschaft 2018, 31, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Crouzier, D.; Perrin, A.; Torres, G.; Dabouis, V.; Debouzy, J.-C. Pulsed Electromagnetic Field at 9.71 GHz Increase Free Radical Production in Yeast (Saccharomyces Cerevisiae). Pathologie Biologie 2009, 57, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, P.; Kumar, N.; Mumtaz, S.; Lim, J.S.; Jang, J.H.; Kim, D.; Sahu, B.D.; Bogaerts, A.; Choi, E.H. Evaluation of Non-Thermal Effect of Microwave Radiation and Its Mode of Action in Bacterial Cell Inactivation. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 14003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsuhaim, H.; Vojisavljevic, V.; Pirogova, E. Effects of Non-Thermal Microwave Exposures on the Proliferation Rate of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Yeast. In Proceedings of the World Congress on Medical Physics and Biomedical Engineering May 26-31, Beijing, China; Long, M., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2012; pp. 48–51. [Google Scholar]

- Janković, S.M.; Milošev, M.Z.; Novaković, M.L. The Effects of Microwave Radiation on Microbial Cultures. Hospital Pharmacology-International Multidisciplinary Journal 2014, 1, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banik, S.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Ganguly, S. Bioeffects of Microwave––a Brief Review. Bioresource Technology 2003, 87, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio, C.; Deam, R.T. Can “Microwave Effects” Be Explained by Enhanced Diffusion? Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2007, 9, 2976–2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, P.; Verma,H. N.; Sisodia,Rashmi; and Kesari, K.K. Microwave Radiation (2.45 GHz)-Induced Oxidative Stress: Whole-Body Exposure Effect on Histopathology of Wistar Rats. Electromagnetic Biology and Medicine 2017, 36, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatopuk, D.U. Exploring the Effects of 2.45 GHz Electromagnetic Field Radiation in the Etiology of Endothelial Injury. PhD Thesis, Suleyman Demirel University, 2023.

- LAI, H. Single-and Double-Strand DNA Breaks in Rat Brain Cells after Acute Exposure to Radiofrequency Electromagnetic Radiation. International Journal of Radiation Biology 1996, 69, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertuccio, M.P.; Acri, G.; Ientile, R.; Caccamo, D.; Currò, M. The Exposure to 2.45 GHz Electromagnetic Radiation Induced Different Cell Responses in Neuron-like Cells and Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riffo, B.; Henríquez, C.; Chávez, R.; Peña, R.; Sangorrín, M.; Gil-Duran, C.; Rodríguez, A.; Ganga, M.A. Nonionizing Electromagnetic Field: A Promising Alternative for Growing Control Yeast. Journal of Fungi 2021, 7, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahortor, E.K.; Malyshev, D.; Williams, C.F.; Choi, H.; Lees, J.; Porch, A.; Baillie, L. The Biological Effect of 2.45 GHz Microwaves on the Viability and Permeability of Bacterial and Yeast Cells. Journal of Applied Physics 2020, 127, 204902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, F.N.A.M.; Gaddawi, F.Y.; Al-Shalash, H.T. Effect of Microwave Radiation on the Ability of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae to Produce Toxins. 2023.

- Zeng, S.-W.; Huang, Q.-L.; Zhao, S.-M. Effects of Microwave Irradiation Dose and Time on Yeast ZSM-001 Growth and Cell Membrane Permeability. Food Control 2014, 46, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeza, M.; Zúñiga, S.; Peragallo, V.; Barahona, S.; Alcaino, J.; Cifuentes, V. Identification of Stress-Related Genes and a Comparative Analysis of the Amino Acid Compositions of Translated Coding Sequences Based on Draft Genome Sequences of Antarctic Yeasts. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NBIMCC Available online:. Available online: https://www.nbimcc.org/www_2020/en/m_catalog.php?id=2 (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Cockrell, A.L.; Fitzgerald, L.A.; Cusick, K.D.; Barlow, D.E.; Tsoi, S.D.; Soto, C.M.; Baldwin, J.W.; Dale, J.R.; Morris, R.E.; Little, B.J.; et al. Differences in Physical and Biochemical Properties of Thermus Scotoductus SA-01 Cultured with Dielectric or Convection Heating. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2015, 81, 6285–6293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, I.; Kode, A.; Biswas, S.K. Assay for Quantitative Determination of Glutathione and Glutathione Disulfide Levels Using Enzymatic Recycling Method. Nat Protoc 2006, 1, 3159–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant Activity Applying an Improved ABTS Radical Cation Decolorization Assay. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, F.; Marques, F.; Fokt, H.; Oliveira, R.; Johansson, B. Measuring Oxidative DNA Damage and DNA Repair Using the Yeast Comet Assay. Yeast 2011, 28, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TriTek Corp. CometScore Tutorial.

- Barisch, C.; Holthuis, J.C.M.; Cosentino, K. Membrane Damage and Repair: A Thin Line between Life and Death. Biological Chemistry 2023, 404, 467–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rols, M.P.; Teissié, J. Electropermeabilization of Mammalian Cells. Quantitative Analysis of the Phenomenon. Biophysical Journal 1990, 58, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.P.; Pham, V.T.H.; Baulin, V.; Croft, R.J.; Crawford, R.J.; Ivanova, E.P. The Effect of a High Frequency Electromagnetic Field in the Microwave Range on Red Blood Cells. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 10798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanisavljev, D.; Gojgić-Cvijović, G.; Bubanja, I.N. Scrutinizing Microwave Effects on Glucose Uptake in Yeast Cells. Eur Biophys J 2017, 46, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbora, A.; Rajput, S.; Komoshvili, K.; Levitan, J.; Yahalom, A.; Liberman-Aronov, S. Non-Ionizing Millimeter Waves Non-Thermal Radiation of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae—Insights and Interactions. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 6635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, M.A.; Wagner, J.R.; Vasallo, M.C.; Añón, M.C.; García, L.; Jiménez, J.C.; López, J.C. Thermal Denaturation Kinetics of Yeast Proteins in Whole Cells of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae and Kluyveromyces Fragilis. Food sci. technol. int. 2002, 8, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munna, Md.S.; Humayun, S.; Noor, R. Influence of Heat Shock and Osmotic Stresses on the Growth and Viability of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae SUBSC01. BMC Res Notes 2015, 8, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Gallot, G. Dynamics of Cell Membrane Permeabilization by Saponins Using Terahertz Attenuated Total Reflection. Biophysical Journal 2020, 119, 749–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blicher, A.; Wodzinska, K.; Fidorra, M.; Winterhalter, M.; Heimburg, T. The Temperature Dependence of Lipid Membrane Permeability, Its Quantized Nature, and the Influence of Anesthetics. Biophysical Journal 2009, 96, 4581–4591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, P.J. Effects of Temperature on Cell Membranes. Symp Soc Exp Biol 1988, 42, 237–258. [Google Scholar]

- Alexandre, H. 2.45 - Autolysis of Yeasts. In Comprehensive Biotechnology (Second Edition); Moo-Young, M., Ed.; Academic Press: Burlington, 2011; ISBN 978-0-08-088504-9. [Google Scholar]

- Horikoshi, S.; Catalá-Civera, J.M.; Schiffmann, R.F.; Fukushima, J.; Mitani, T.; Serpone, N. Microwave Heating. In Microwave Chemical and Materials Processing: A Tutorial; Horikoshi, S., Catalá-Civera, J.M., Schiffmann, R.F., Fukushima, J., Mitani, T., Serpone, N., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; ISBN 978-981-97-5795-4. [Google Scholar]

- Shamis, Y.; Croft, R.; Taube, A.; Crawford, R.J.; Ivanova, E.P. Review of the Specific Effects of Microwave Radiation on Bacterial Cells. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2012, 96, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dependence of Diffusion on Temperature and Pressure. Diffusion in Solids: Fundamentals, Methods, Materials, Diffusion-Controlled Processes; Mehrer, H., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2007; ISBN 978-3-540-71488-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sies, H. Oxidative Stress: A Concept in Redox Biology and Medicine. Redox Biology 2015, 4, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, J.F.; Whyte, B.; Bissinger, P.H.; Schiestl, R.H. Oxidative Stress Is Involved in Heat-Induced Cell Death in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1996, 93, 5116–5121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhadj Slimen, I.; Najar,Taha; Ghram,Abdeljelil; Dabbebi,Hajer; Ben Mrad,Moncef; and Abdrabbah, M. Reactive Oxygen Species, Heat Stress and Oxidative-Induced Mitochondrial Damage. A Review. International Journal of Hyperthermia 2014, 30, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahin, S.; Singh, V.P.; Shukla, R.K.; Dhawan, A.; Gangwar, R.K.; Singh, S.P.; Chaturvedi, C.M. 2.45 GHz Microwave Irradiation-Induced Oxidative Stress Affects Implantation or Pregnancy in Mice, Mus Musculus. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2013, 169, 1727–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usikalu, M.R.; Obembe, O.O.; Akinyemi, M.L.; Zhu, J. Short-Duration Exposure to 2.45 GHz Microwave Radiation Induces DNA Damage in Sprague Dawley Rat’s Reproductive Systems. African Journal of Biotechnology 2013, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regalbuto, E.; Anselmo, A.; De Sanctis, S.; Franchini, V.; Lista, F.; Benvenuto, M.; Bei, R.; Masuelli, L.; D’Inzeo, G.; Paffi, A.; et al. Human Fibroblasts In Vitro Exposed to 2.45 GHz Continuous and Pulsed Wave Signals: Evaluation of Biological Effects with a Multimethodological Approach. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 7069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, S.; Isozumi, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; Taki, M.; Miyakoshi, J. Effects of 2.45-GHz Electromagnetic Fields with a Wide Range of SARs on Micronucleus Formation in CHO-K1 Cells. The Scientific World Journal 2004, 4, 743762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aweda, M.A.; Usikalu, M.R.; Wan, J.H.; Ding, N.; Zhu, J.Y. Genotoxic Effects of Low 2.45 GHz Microwave Radiation Exposures on Sprague Dawley Rats. International Journal of Genetics and Molecular Biology 2010, 2, 189–197. [Google Scholar]

- Vrhovac, I. a; Hrascan, R.; Franekic, J. Effect of 905 MHz Microwave Radiation on Colony Growth of the Yeast Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Strains FF18733, FF1481 and D7. Radiology and Oncology 2010, 44, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzellitti, S.; Valbonesi, P.; Ciancaglini, N.; Biondi, C.; Contin, A.; Bersani, F.; Fabbri, E. Transient DNA Damage Induced by High-Frequency Electromagnetic Fields (GSM 1.8GHz) in the Human Trophoblast HTR-8/SVneo Cell Line Evaluated with the Alkaline Comet Assay. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis 2010, 683, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Absorbance at 260 nm (A260) determined by the nucleic acids leaked from yeast cells: irradiated with 2.45 GHz microwave at three exposure conditions – 2 cm away from the antenna for 20 min, 4 cm for 20 min and 4 cm for 60 minutes (EMF), undergone the corresponding conventional heating (Heating), not irradiated (Control) or held at room temperature (RT) for the same periods of time. The values presented are mean ± SEM and distinct letters denote significantly different variants among each experimental setup (p < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Absorbance at 260 nm (A260) determined by the nucleic acids leaked from yeast cells: irradiated with 2.45 GHz microwave at three exposure conditions – 2 cm away from the antenna for 20 min, 4 cm for 20 min and 4 cm for 60 minutes (EMF), undergone the corresponding conventional heating (Heating), not irradiated (Control) or held at room temperature (RT) for the same periods of time. The values presented are mean ± SEM and distinct letters denote significantly different variants among each experimental setup (p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Reduced glutathione (GSH, mg/ml) content in yeast cells: irradiated with 2.45 GHz microwave at three exposure conditions – 2 cm away from the antenna for 20 min, 4 cm for 20 min and 4 cm for 60 minutes (EMF), undergone the corresponding conventional heating (Heating), not irradiated (Control) or held at room temperature (RT) for the same periods of time. The values presented are mean ± SEM and distinct letters denote significantly different variants among each experimental setup (p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Reduced glutathione (GSH, mg/ml) content in yeast cells: irradiated with 2.45 GHz microwave at three exposure conditions – 2 cm away from the antenna for 20 min, 4 cm for 20 min and 4 cm for 60 minutes (EMF), undergone the corresponding conventional heating (Heating), not irradiated (Control) or held at room temperature (RT) for the same periods of time. The values presented are mean ± SEM and distinct letters denote significantly different variants among each experimental setup (p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Antioxidant capacity, expressed as Trolox equivalent (mmol/L), of yeast cells: irradiated with 2.45 GHz microwave at three exposure conditions – 2 cm away from the antenna for 20 min, 4 cm for 20 min and 4 cm for 60 minutes (EMF), undergone the corresponding conventional heating (Heating), not irradiated (Control) or held at room temperature (RT) for the same periods of time. The values presented are mean ± SEM and distinct letters denote significantly different variants among each experimental setup (p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Antioxidant capacity, expressed as Trolox equivalent (mmol/L), of yeast cells: irradiated with 2.45 GHz microwave at three exposure conditions – 2 cm away from the antenna for 20 min, 4 cm for 20 min and 4 cm for 60 minutes (EMF), undergone the corresponding conventional heating (Heating), not irradiated (Control) or held at room temperature (RT) for the same periods of time. The values presented are mean ± SEM and distinct letters denote significantly different variants among each experimental setup (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Tail length (pixels) of comets determined by single cell gel electrophoresis of yeast cells irradiated with 2.45 GHz microwave at three exposure conditions – 2 cm away from the antenna for 20 min, 4 cm for 20 min and 4 cm for 60 minutes (EMF), or not irradiated (Control). The values presented are mean ± SEM and distinct letters denote significantly different variants among each experimental setup (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Tail length (pixels) of comets determined by single cell gel electrophoresis of yeast cells irradiated with 2.45 GHz microwave at three exposure conditions – 2 cm away from the antenna for 20 min, 4 cm for 20 min and 4 cm for 60 minutes (EMF), or not irradiated (Control). The values presented are mean ± SEM and distinct letters denote significantly different variants among each experimental setup (p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Tail DNA percentage of comets determined by single cell gel electrophoresis of yeast cells irradiated with 2.45 GHz microwave at three exposure conditions – 2 cm away from the antenna for 20 min, 4 cm for 20 min and 4 cm for 60 minutes (EMF), or not irradiated (Control). The values presented are mean ± SEM and distinct letters denote significantly different variants among each experimental setup (p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Tail DNA percentage of comets determined by single cell gel electrophoresis of yeast cells irradiated with 2.45 GHz microwave at three exposure conditions – 2 cm away from the antenna for 20 min, 4 cm for 20 min and 4 cm for 60 minutes (EMF), or not irradiated (Control). The values presented are mean ± SEM and distinct letters denote significantly different variants among each experimental setup (p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Olive tail moment of comets determined by single cell gel electrophoresis of yeast cells irradiated with 2.45 GHz microwave at three exposure conditions – 2 cm away from the antenna for 20 min, 4 cm for 20 min and 4 cm for 60 minutes (EMF), or not irradiated (Control). The values presented are mean ± SEM and distinct letters denote significantly different variants among each experimental setup (p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Olive tail moment of comets determined by single cell gel electrophoresis of yeast cells irradiated with 2.45 GHz microwave at three exposure conditions – 2 cm away from the antenna for 20 min, 4 cm for 20 min and 4 cm for 60 minutes (EMF), or not irradiated (Control). The values presented are mean ± SEM and distinct letters denote significantly different variants among each experimental setup (p < 0.05).

Table 1.

SAR and temperatures for yeast suspensions treated with 2.45 GHz EMF at different exposure conditions.

Table 1.

SAR and temperatures for yeast suspensions treated with 2.45 GHz EMF at different exposure conditions.

Exposure

setup |

Distance to antenna, cm |

t, min |

SAR, W/kg |

RT, °C * |

Tmax, °C * |

ΔT, °C * |

| 1 |

2 |

20 |

132 |

21.4 ± 0.8 a

|

44.2 ± 0.7 a

|

22.8 ± 1 a

|

| 2 |

4 |

20 |

126 |

24.6 ± 1.5 a

|

32.5 ± 2.3 b

|

7.9 ± 0.8 b

|

| 3 |

4 |

60 |

126 |

24.2 ± 0.7 a

|

36.6 ± 1.2 b

|

12.5 ± 0.4 c

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).