1. Introduction

Recombinant virus vector technology is an established vaccine “plug-and-play” platform that has successfully been used to develop a new generation of vaccines that utilise a subunit antigen over a more conventional whole pathogen approach [

1]. These recombinant vaccines offer many of the best features of whole pathogen-vaccines, including appropriate stimulation of innate and adaptive immune responses and benefit from cost-effective and reliable in vitro production at scale [

2]. Several of these virus vector systems have been shown to stimulate both antibody and cellular immune responses, as has been demonstrated for a number of commercial vaccines to COVID-19 during the recent pandemic [

3]. The safety of recombinant vectored vaccines has previously been identified as a potential barrier to deployment for both humans and animals [

4,

5], however, a number of poxvirus-based vaccines have already been commercialised for viral diseases of animals, including Newcastle Disease virus (Trovac

®-NDV, Vectormune

® ND), Fowl Pox virus and Infectious Laryngotracheitis (Vectormune FP LT), and avian influenza (Trovac

® Al H5 and Trovac Prime H7) for chickens, as reviewed by Wang

et al. [

6].

There is a notable gap in commercial vaccines for bacterial diseases adopting the virus vector technology [

7,

8]. To address this, we have used data for existing commercial bacterial vaccines (live, live-attenuated and whole pathogen inactivated preparations) to select a candidate protective antigen for deployment in virus vector platforms. This antigen is the major outer membrane protein (MOMP), present in Gram-negative bacteria including chlamydial species [

9]. There is a large body of evidence across human, farm animal and wildlife host species on the protective efficacy of this antigen [

10,

11,

12,

13]. We have selected the MOMP gene

ompA from

Chlamydia abortus, a major abortifacient pathogen of sheep, for incorporation into two virus vector systems we have developed. They are based on two viruses of sheep endemic to the UK, a sheep parapoxvirus Orf and a sheep lentivirus, that can be engineered for safely delivering potentially protective antigens.

Orf Virus has a large (~135 kbp) linear double-stranded DNA genome containing both genes that are essential to virus replication and those that are non-essential to replication but confer an advantage to the virus in the face of the host’s immune response. The engineering of poxviruses into vaccines has focussed on manipulation of regions of the genome less critical for virus fitness for insertion of foreign antigen(s) [

14,

15]. Poxvirus vaccines have a number of other important features, such as the ability to stimulate both antigen-specific humoral and cellular immunity, and exhibit limited short-lived anti-vector immunity that doesn’t appear to compromise vaccine antigen-induced immunity [

16]. Live poxvirus vaccines replicate in the cytosol of the recipient host cells, and therefore, reduces the opportunity to recombine with the DNA of the host organism [

6,

17]. To date most studies using Orf as a vaccine vector have been conducted in non-permissive hosts that include mice, cats and dogs. Relatively little data is known about vaccination in permissive hosts such as sheep. Using the sheep parapoxvirus Orf (ORFV), we have developed a modified ORFV-vectored vaccine (mORFV) with the NZ2 strain [

14] to develop a new prototype vaccine against OEA.

In comparison to poxviruses, lentiviruses are less well-established as vaccine vectors but several studies have shown that they are potent stimulators of protective immunity for vaccine targets [

18,

19]. For example, lentiviral vectors derived from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) are able to elicit protective responses to a variety of pathogens, including viruses (e.g., West Nile virus, Japanese encephalitis virus, papillomavirus and influenza virus) [

20,

21,

22,

23] and protozoa (e.g., malaria, Leishmania and Naegleria fowleri) [

24,

25,

26]. As with poxviral vectors, lentiviral vectors stimulate both cellular and humoral immune responses to the expressed transgene.

Lentiviruses offer a number of advantages as vaccine vectors. Firstly, they are capable of stable gene delivery to non-dividing cells, including antigen presenting cells. Secondly, lentiviral-mediated vaccine delivery does not result in expression of any viral genes within the targeted animal so there is negligible anti-vector immunity. Thirdly, the small genome size lentiviruses (~9.2 kbp) allows them to be readily manipulated in vitro such that incorporation of foreign (i.e., pathogen) antigen genes is straightforward and allows for rapid in vitro testing of transgene expression. Since HIV-based lentiviral vectors do not efficiently infect sheep antigen-presenting cells [

27,

28] we have developed a lentiviral vector system from the ovine lentivirus, maedi-visna virus (mMVV) which is able to transduce ovine macrophages and dendritic cells much more efficiently than vectors derived from HIV-1 in vitro [

29].

In the prototype vaccines, we have utilized the

C. abortus gene

ompA expressing the dominant immunogenic MOMP of the efficacious subcellular chlamydial outer membrane complex (COMC) prototype vaccine [

30,

31]. In a primary investigation we compared two groups of sheep immunised with the

ompA gene using the two vector systems, mORFV and mMVV, assessing their ability to stimulate MOMP-specific antibody and antigen-driven interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) responses. Based on the results observed, a follow-up study was conducted using the more promising platform technology to comprehensively assess its immunogenic capacity as a live or inactivated vaccine.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Project Overview

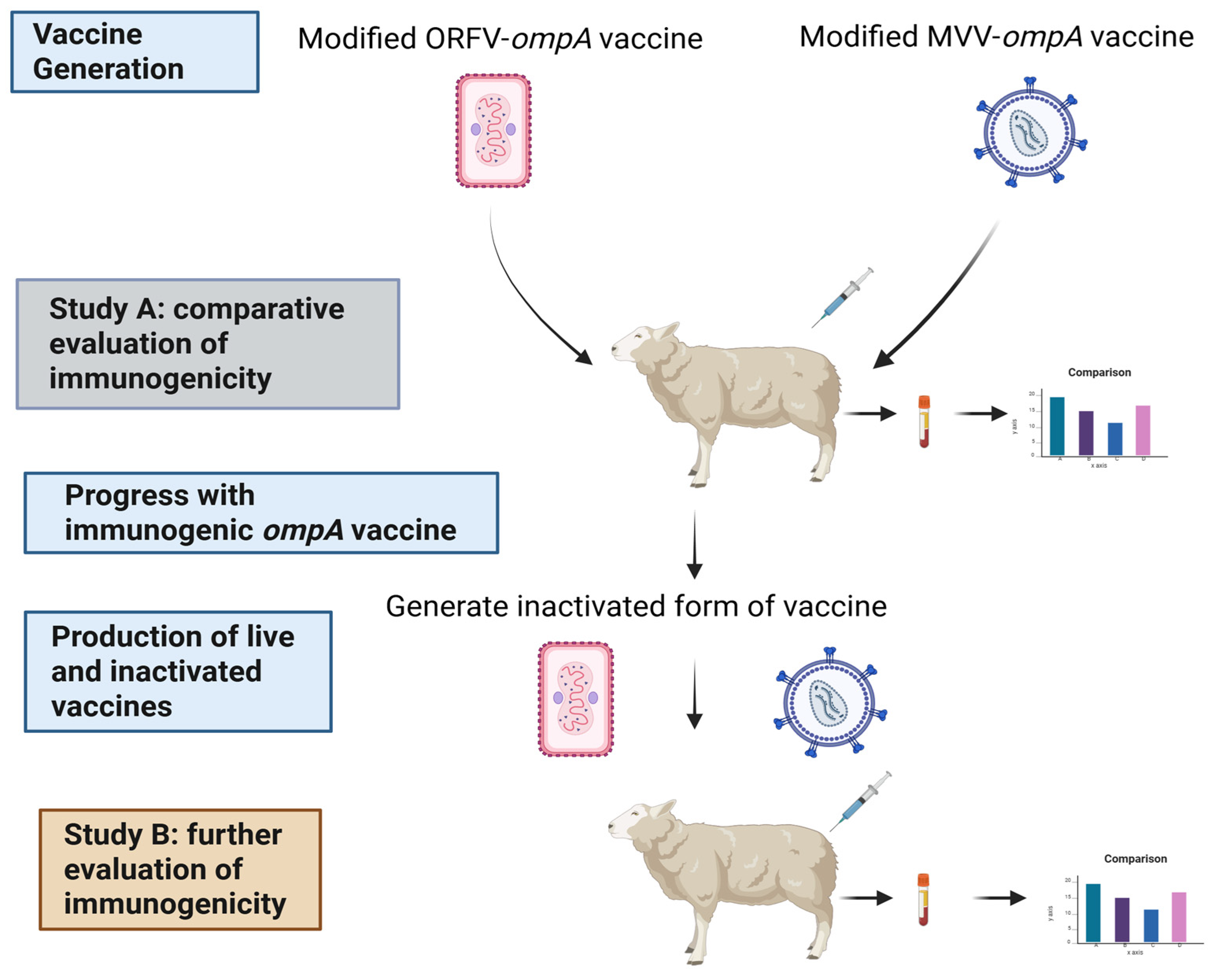

This project comprised two immunogenicity studies to identify and evaluate which of two virus vectors, mORFV and mMVV, that were engineered to express the recombinant protein product (MOMP) of the

ompA gene induced the most appropriate immune responses in sheep (

Figure 1).

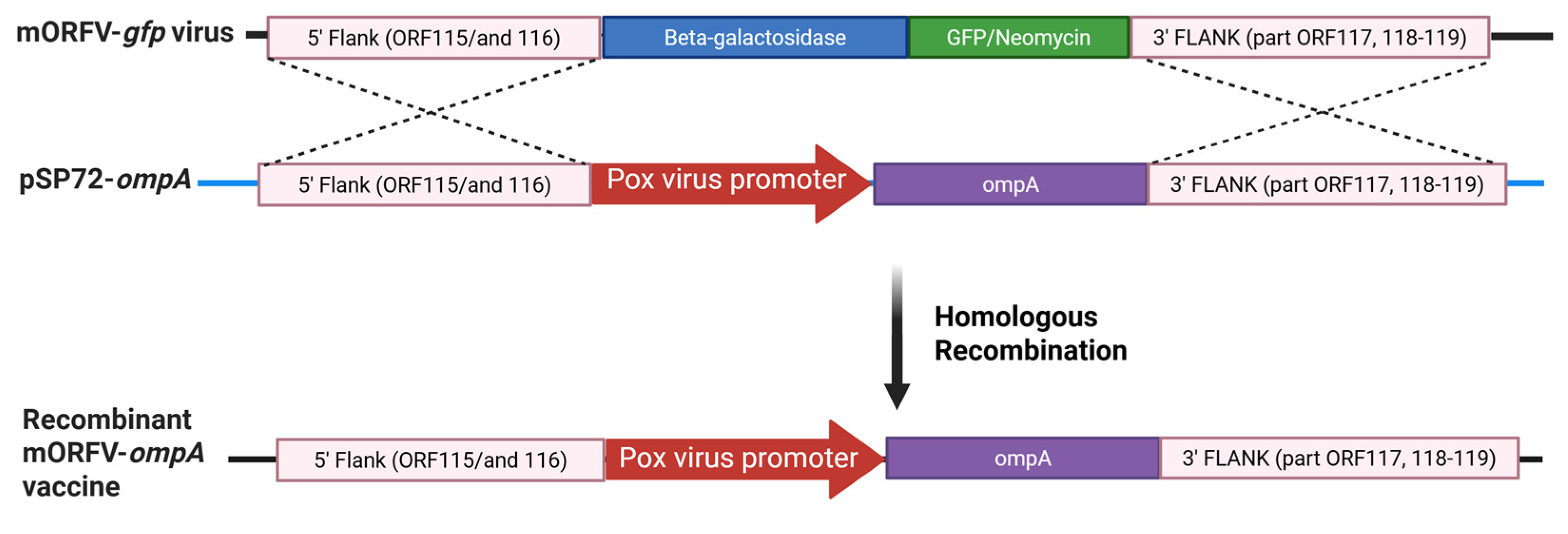

2.2. Production and Evaluation of the Recombinant Modified Orf Virus Encoding the ompA Gene of C. abortus (mORFV-ompA)

The mORFV-

ompA virus was generated by homologous recombination using the well-characterised ORFV NZ2 virus strain (Genbank accession no. DQ184476) [

14] that we had previously modified to express green fluorescent protein (gfp) (strain mORFV-

gfp; unpublished) and a plasmid construct containing the

C. abortus ompA gene (GenBank accession CR848038, gene CAB048) (

Figure 2), which encodes the 40 kDa MOMP. mORFV-

gfp was generated by replacing gene 117 of ORFV NZ2 with the

gfp gene and the neomycin resistance and β-galactosidase genes: gene 117 encodes a non-essential protein that has granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and interleukin (IL)-2 binding properties [

32]. The inclusion of the

gfp gene enabled differentiation of the ‘clear’ plaques produced by the modified virus from the ‘green’ plaques produced by the parent virus. The

ompA plasmid (pSP72-

ompA,

Figure 2) was constructed by cloning the left viral flanking region of ORFV (1499 bp; genes 115 and 116), an ORFV early/late promoter (42 bp), the

ompA gene (1170 bp) and the right viral flanking region of ORFV (1794 bp, comprising 150 bp from the 3′ end of gene 117 and complete genes 118 and 119) into commercial cloning vector pSP72 (Promega, Southampton, UK, # P2191) by PCR, targeting appropriate restriction enzyme sites and using standard cloning techniques. pSP72-

ompA was produced for use in transfections by transforming JM109 cells (Promega, #L2005) and culturing in successive rounds of L-broth culture at 37 °C (using standard techniques) and an endonuclease-free stock of plasmid DNA was prepared using an Endo-free Plasmid Maxiprep Kit (Qiagen, Germany, #12362).

To generate mORFV-

ompA, 1 µg pSP72-

ompA was transfected into foetal lamb skin (FLS) primary cells, in 6-well plates, using a Cell Line Nucleofector Kit L

®, Program T-030 (#VCA-1005, Lonza, Germany). After incubating for 3 h at 37 °C, the transfected cells were infected with parental virus (mORFV-

gfp) virus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 in Medium 199 (Merck, Dorset, UK, #M0650) supplemented with 2 % heat-inactivated (ΔH) foetal bovine serum (FBS, Merck, #F2442, USA origin), 2 mM l-glutamine (Merck,# 49419), 0.15 % sodium hydrogen carbonate (Merck, #6014) and 10 % tryptose phosphate broth (Merck, #T8159) and incubated at 37 °C/5 % CO

2 until plaques were observed (approximately 4 days). ‘Clear‘ plaques produced by the mORFV-

ompA recombinant virus, following the homologous recombination of mORFV-

gfp and the transfected pSP72-

ompA (

Figure 2), were isolated from the parental ’green‘ plaques by successive rounds of plaque purification. Determination of ‘clear’ plaques only was assessed by light microscopy and confirmed by specific PCR. Here, FLS cells infected with mORFV-

ompA was harvested at 3 days and 6 days post-infection. Cells were lysed into RLT solution (Qiagen, # 74104) containing beta-mercaptoethanol (Merck, #M6250) and RNA prepared using RNA prep kit with Qiashredder (Qiagen, #74104). A one-step RT-PCR and combined gDNA digestion was performed using the Superscript IV One-Step RT-PCR System and EZDNase (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Leicestershire, UK, # 12595025) to amplify

ompA fragment

Supplementary Figure S1A).

Viral DNA was isolated and sequenced using various sequencing primers corresponding to genes 116 and 118 of ORFV and the ompA gene to confirm that the recombined sequence was correct. A single viral plaque was then amplified to create virus stocks for downstream studies. The mORFV-ompA was titrated on FLS cells using twelve replicates from 10-2 to 10-8 alongside no virus control wells in tissue culture flatbottom plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #07-200-90) and allowed to incubate at 37 °C for 7-10 days for the determination of TCID50.

2.3. Production of the Recombinant Modified Maedi Visna Virus Encoding the ompA Gene of C. abortus (mMVV-ompA)

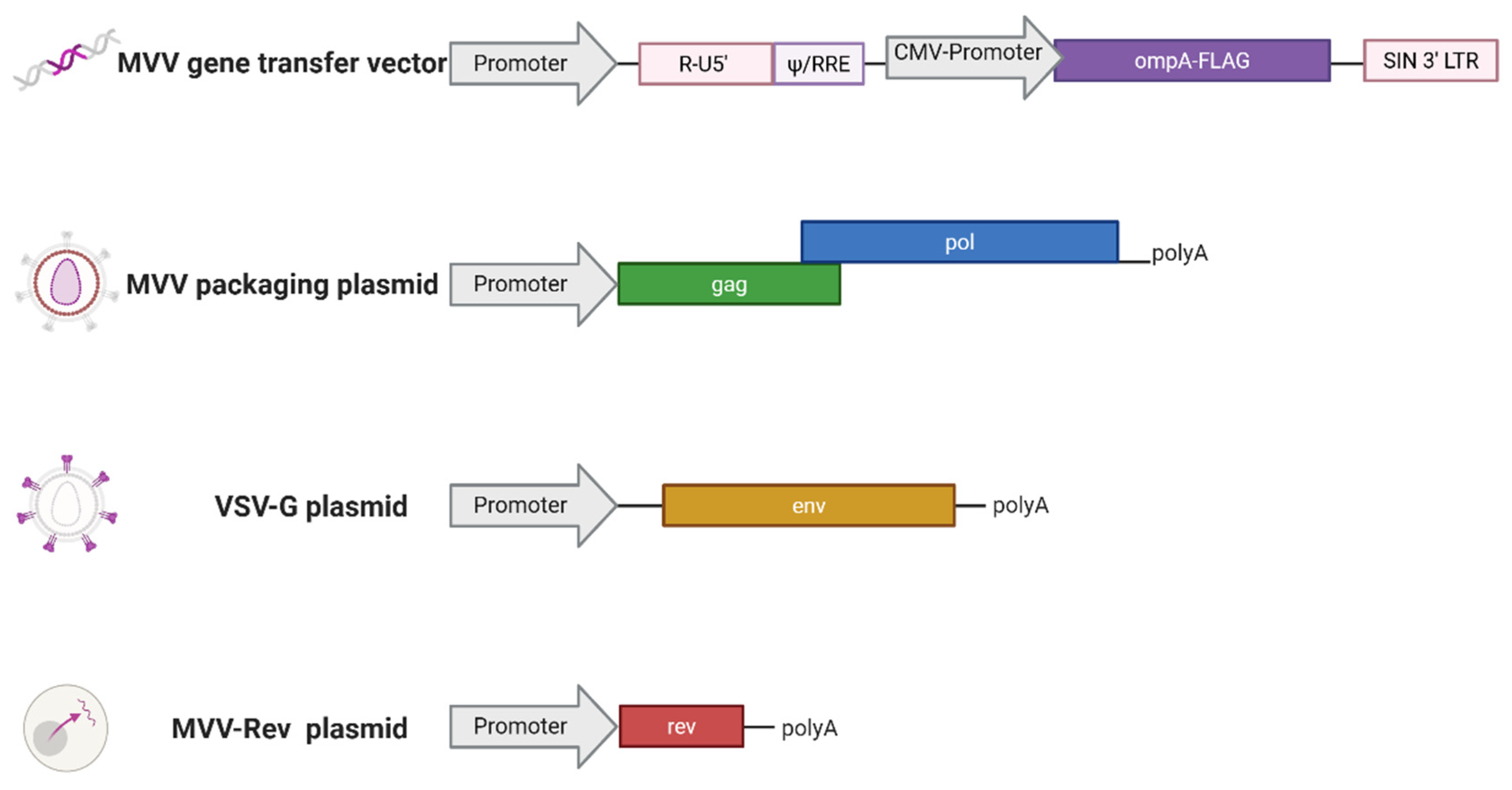

mMVV vaccine vectors utilised a four-plasmid MVV-derived lentiviral vector system comprising a MVV gene transfer vector, a MVV Gag-Pol packaging construct, and plasmids expressing MVV Rev and vesicular stomatitis glycoprotein G (VSV-G) [

29,

33,

34]. To construct the MVV transfer vector expressing

C. abortus MOMP,

ompA was isolated by PCR from

C. abortus DNA and inserted downstream of the human cytomegalovirus (CMV) immediate-early promoter (

Figure 3). An N-terminal signal peptide from the

Ovis aries immunoglobulin kappa-2.1 light chain was added to mediate membrane targeting in eukaryotic cells. A C-terminal FLAG epitope tag was added to aid detection of protein expression.

The mMVV-o

mpA vector particles were produced by co-transfection of human embryonic kidney 293T cells with the four vector plasmids (

Figure 3) using FuGENE-HD transfection reagent (Promega, #E2311), according to the manufacturers’ guidelines. 293T cells were cultured in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s Medium (Merck, #I3390), supplemented with 4 mM glutamine and 10% ΔH FBS. Briefly, 293T cells were plated in T75 tissue culture flasks to achieve approximately 80% confluency on the day of transfection. Transfection complexes were prepared by combining 3.6 μg MVV packaging construct (pCAG-MV-GagPol-CTE2X), 5.4 μg MVV transfer vector encoding

ompA (pCVW-CMV-

ompA), 1.2 μg MVV Rev expression construct (pCMV-Rev), and 1.8 μg VSV-G expression construct (pMD2.G: Addgene plasmid #12259; a gift from Didier Trono, EPFL, Lausanne, Switzerland), diluted in 1200 µL of serum-free medium (OptiMEM; Gibco, Fisher Scientific, Loughborough, UK; #51985026) and 36 µL of FuGENE-HD. Following incubation at RT for 15 min, FuGENE-DNA complexes were added to cells in 7 mL of fresh medium per flask and cells incubated at 37 °C for 16-18 h before medium was replaced with 10 mL fresh IMDM supplemented with 10% FBS. Cell culture supernatant containing vector particles was harvested 42 - 48 h post-transfection and centrifuged at 300 ×

g for 5 min before filtration through a 0.45 μm cellulose acetate filter (Sartorius, Gillingham, UK, # 11106-100------G). Viral particles were pelleted at 70,000 ×

g for 2 h at 4 °C in an Optima L-90K ultracentrifuge using an SW32 Ti rotor (Beckman Coulter, Buckinghamshire, UK) and resuspended at 100 × concentration in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and stored frozen in aliquots at –70 °C.

2.4. Evaluation of mMVV-ompA

2.4.1. Detection of Protein Expression

To confirm expression of MOMP protein from the mMVV-

ompA vector, the permissive cell line Crandell-Rees Feline Kidney (CRFK) (cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Earle’s medium supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 1% non-essential amino acids (Gibco) and 10% FBS) was transduced with mMVV-

ompA and cell lysates prepared 72 h post-transduction. Cell lysates were analysed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. Blots were probed with a monoclonal antibody (mAb) to the FLAG epitope (mouse anti-FLAG M2 mAb, Merck, #F1804, diluted 1:1000) and rabbit anti-mouse HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Dako, Agilent Technologies UK Ltd., Cheshire, UK, #P0266, 1:1000)- shown in

Supplementary Figure S1B.

2.4.2. Determination of mMVV-ompA Vector Titre

The infectious titre of vector mMVV-

ompA was determined by TCID50 assay. Briefly, CRFK cells were plated in 96-well plates (1 x 10

4 cells per well, Thermo Fisher Scientific, #07-200-90) and cultured overnight. Ten-fold serial dilutions (10

-1 - 10

-8) of mMVV-

ompA were then plated onto these cells (8 wells per dilution) in a final volume of 200 µL per well with 4 μg/mL Polybrene (Merck, #TR-1003) and cultured for 72 h. Medium was removed and cells washed once in PBS before fixing in ice cold methanol:actetone (1:1; 200 µL/well) for 15 min at RT and washed twice with PBS (200 µL/well). Cells were blocked with PBS/5% FBS for 1 h, and MOMP protein detected by immunocytochemistry using a primary antibody to the FLAG epitope tag (Merck #F1804, diluted 1:500) and secondary goat-anti-mouse IgG conjugated to beta-galactosidase (Southern Biotechnology, #1030-06 diluted 1:200). Beta-galactosidase activity was detected as described previously [

35]. Positive wells were scored as containing one or more positive cell foci, and TCID50 calculated using the Reed-Muench method [

36].

2.5. Experimental Animals and Ethics Statement

The Moredun Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Body approved the experimental protocols described for both of the in vivo vaccine immunogenicity studies (Study A permit number E52/18, approved 25th October 2018; and Study B E48/19, approved 22nd October 2019). All of the husbandry practices, welfare checks and animal procedures were carried out in strict accordance with the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986, as well as in compliance with all UK Home Office Inspectorate regulations and ARRIVE guidelines 2.0 [

37]. Sheep were monitored at least twice daily throughout the duration of the study for any clinical signs or welfare issues.

2.6. Selection of Sheep for the Immunogencity Studies

Sheep were obtained from the Moredun Research Institute breeding flock for Study A (6-month-old Texel-cross Scottish Mules: n = 30) or from disease-free OEA-accredited high health flocks (participating in Scotland’s Rural College Premium Sheep and Goat Health Schemes [

38]; 18 month old Scottish Mules; n = 50) for Study B. In both cases animals were pre-screened to ensure their OEA disease-free status and to ensure they were negative for other abortifacient agents, including pestiviruses bovine viral diarrhoea virus (types 1 and 2) and border disease virus. For each animal, two 10 mL diagnostic blood samples were taken for serological analysis into BD Vacutainer

® serum tubes (Fisher Scientific; #12957686) and BD Vacutainer

® heparin tubes (Fisher Scientific; #13171543) for peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) stimulation/ recall assays. Serum was screened by rOMP90-3 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), as previously described [

39]. Animals were excluded from the study if they had test values, normalised to positive and negative controls above 60%. In addition, cellular immune recall and stimulation assays were conducted on PBMC isolated from whole blood using standard protocols, as previously revised [

40]. Animals were excluded on the basis of low IFN-γ responses to the T cell mitogen Concanavalin A (ConA at 5 µg/ml, from

Canavalia ensiformis, Merck, #C0412) and high IFN-γ responses to COMC antigen (0.5 µg/ml) and

C. abortus elementary body (EB) antigen (1 µg/ml) for two cellular pre-vaccination sample points. A final group of twelve sheep were selected for study A (three groups of four sheep) and 30 sheep for study B (three groups of ten). Groups were balanced for their capacity to respond to ConA, as undertaken previously for a

C. abortus pathogenesis study [

40] (Wattegedera et al., 2020).

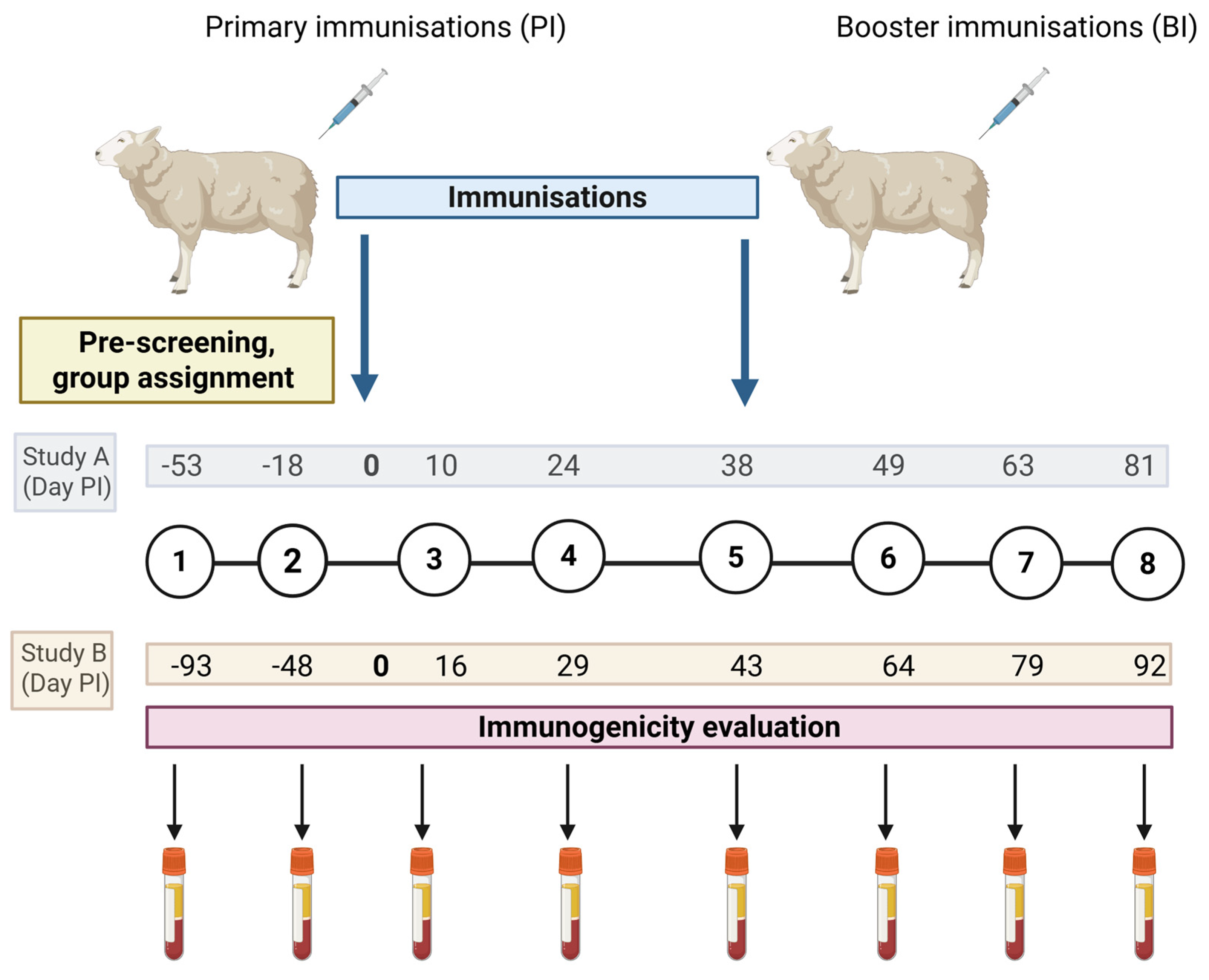

2.7. Preparation and Administration of the ompA Virus Vaccines and Blood Sample Schedules for Immunogenicity Studies A and B

For Study A, cell free supernatants containing mORFV-

ompA (10

7 TCID50 /ml) or mMVV-

ompA (10

6 TCID50/ml) were prepared in a volume of 1 mL for both primary and booster immunisations. The vaccines were delivered intramuscularly to two groups of four sheep (group 1, mORFV-

ompA; group 2, mMVV-

ompA) using a 19G 1” needle using a luer lock syringe to the right hind leg muscle over the prefemoral lymph node. This constituted day zero of the immunogenicity Study A (

Figure 4). Four sheep served as non-immunised negative controls (group 3). Booster immunisations (BI) were delivered 38 days later. Injection sites were monitored at day 1, 3 and 7 post primary immunisation (PI) for signs of any lesions.

The most promising virus vector from Study A was chosen for a more comprehensive assessment of immunogenicity in a larger sheep study (Study B), following delivery as either a live or inactivated vaccine. In order to derive the inactivated vaccine, the chosen live vaccine stock was divided, diluted to 107 TCID50/ml and then inactivated by treatment with 0.05 % v/v β-propiolactone (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #B23197,) for 16 h at 4 °C. Following inactivation of the vaccine virus, the beta-propriolactone was itself inactivated by incubation at 37 °C for 2 h. The beta-propriolactone-treated virus was assessed alongside the untreated live vaccine by three successive rounds of blind passaging in susceptible FLS cells to check for cytopathic effects (CPE). The β-propiolactone treated virus was given a second round of treatment and confirmed free of CPE in susceptible cells for three successive rounds of sub-culture. Cell lysates were collected and analysed by RT-PCR as described in 2.2 to determine ompA transcription.

The vaccines were prepared as undertaken for Study A with identified

ompA-vaccine (10

7 TCID50 /ml or 10

6 TCID50/ml) equivalent in a volume of 1mL for both primary and booster immunisations. The vaccines were delivered intramuscularly to two groups of ten sheep (group 1, inactivated vaccine; group 2, live vaccine) using a 19G 1” needle using a luer-lock syringe to the right hind leg muscle over the prefemoral lymph node (

Figure 4). Ten sheep served as non-immunised negative controls (group 3). Booster immunisations were delivered 38 days later.

For both studies, the primary immunisations were delivered on designated day zero. Blood samples were collected throughout both studies for humoral and cellular analyses, with some differences on timing (

Figure 4).

2.8. Serological Responses to C. abortus MOMP

Serum was collected from whole blood throughout both studies at the sample points highlighted in

Figure 4. Samples were analysed for the presence of antibodies to

C. abortus MOMP using an ID Screen

® Chlamydophila abortus Indirect Multi-species ELISA kit (Innovative Diagnostics Vet, Grabels, France, # CHLMS-MS-5P), following manufacturer’s instructions. Serum samples from a challenge control post-abortion sheep from a previous experimental study served as additional positive control samples in the ELISAs.

2.9. Cellular Analysis

PBMC isolated at the sample points outlined in

Figure 4 were used for antigen-recall assays, as previously described [

40], where cells were adjusted to 2 x 10

6 cells/mL in IMDM supplemented with 10 % ΔH FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, gentamicin (50 µg/mL), 100 IU/mL penicillin, 50 μg/ mL streptomycin and 50 µM beta-mercaptoethanol (all Merck, #59202C, #G1522, # P4458 and #M6250). 100 µL of PBMC were added to U-bottom ELISA plates (Fisher Scientific, Loughborough, UK, #TKT-180-050D) with 100 µL of

C. abortus EBs (1 µg/mL) or COMC (0.5 µg/mL) in lymphocyte stimulation assays (LSAs) for 96 h in a humidified incubator (ThermoScientific, Heracell™ 150i CO

2 Incubator) at 37 °C, 5% CO

2. The T cell mitogen control, Con A (5 µg/mL) and medium alone were also included as positive and negative controls, respectively. Culture supernatants from quadruplicate wells for each stimulation condition and animal were pooled and stored at -20° C prior to cytokine analyses.

A specific IFN-γ cytokine ELISA was conducted as a representation of the key cluster of differentiation (CD)4 T cell subset T-helper (Th)-1 response signature cytokines, as previously described [

40] for Studies A and B. Interleukin (IL)-10, IL-4 and IL-17A were assessed as representative CD4 T cell signature cytokines in quantifiable sandwich ELISAs as previously described [

40] with the exception of using a quantifiable recombinant ovine IL-17A set of standards in the Kingfisher Biotech ovine IL-17A ELISA (# cat number DIY0925V, Kingfisher Biotech, St. Paul, MN, USA) for culture supernatant samples for Study B only.

2.10. Assessment of Humoral Responses to ORFV

Serum was analysed for presence of ORFV-specific immunoglobulin (Ig)-G using an in-house ELISA previously adapted [

41] using the previously published generic protocol [

42]. In brief, high binding serological plates (Griener-Bio One #M129B, Glasgow, UK) were coated with 50 µL/well of cell-culture derived Orf virus antigen or foetal lamb muscle cell culture supernatant at a 1:500 dilution in 0.1 M carbonate buffer, pH 9.6 overnight at 4 °C. Plates were washed 6 times in PBS with 0.05% Tween 20 (Merck, # P4474, # P1379) (wash buffer) prior to blocking in 4% Infasoy (Cow & Gate, Wiltshire, UK, # COW495N) diluted in PBS for 1 h at RT. Plates were washed twice and then 50 µL/well of diluted serum test samples (at 1:200 and 1:500 in 2% Infasoy/PBS), were added in duplicate for each of the positive and negative antigens alongside known positive and negative control sera for 1.5 h at RT. Plates were washed six times and the 50 µL/well of detection antibody donkey anti-sheep IgG-horseradish peroxidase (Binding Site, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat no: 258122B), at a 1:2000 dilution for 1 h at RT. Plates were washed six times and then 50 µL/well of tetramethylbenzidine ELISA substrate was added for 5 min for development prior to reaction termination with 50 µL/well of 0.2 M hydrochloric acid. Plates were read by spectrophotometer (Dynex MRX II, Dynex Technologies, Virginia, USA) at 450 nm using the Revelation™ software. Corrected the sample optical density (OD) values by the subtraction OD value of test sera bound to negative FLM antigen.

2.11. Statistical Analyses

Cytokine responses to each stimulation condition measured over bleeds for each vaccine and unvaccinated control group were modelled using linear mixed models fitted by restricted maximum likelihood to

transformed data. Analogous models were fitted to log-transformed cellular immune responses and humoral responses to MOMP and the vaccine backbone ORFV. All models included treatment group, bleed and their interaction as fixed effects and animal ID as random effect. Statistical significance of model coefficients was based on conditional

F-tests. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were based on

t-tests from estimated marginal means. Whenever multiple statistical comparisons over treatment groups or bleeds were performed, the resulting

p-values were adjusted to control for false discovery rate using the Benjamini-Hochberg method [

43].

Statistical modelling and associated comparisons were conducted on the R system for statistical computing version 4.4.1 [

44]. Statistical significance was concluded at the ordinary 5% level.

3. Results

3.1. Confirmation of ompA Gene mRNA/MOMP Protein from Vaccine Constructs In Vitro

The sequencing of the products of specific PCRs from FLS cells infected with the mORFV-

ompA vaccine revealed that the recombinant virus was transcribing the RNA and this was not derived from

gDNA (

Supplementary Figure S1A). The protein expression of MOMP from the mMVV-

ompA vaccine was determined by transduction of cultured CRFK cells and immunoblot analysis of cell lysates. Immunoblotting showed the presence of the expected 40 kDa MOMP-FLAG protein (

Supplementary Figure S1B).

3.2. Screening of Antigen Reactivity to MOMP in Sheep Cohort for Study A

3.2.1. Antibody Responses to MOMP

Serum samples from day -10 (

Figure 4) were assessed for the cohort of sheep identified for the comparative immunogenicity Study A. Sheep were selected for the

ompA-vaccine groups that met the criteria of IgG-MOMP responses under the designated kit cut-off of positivity, under 50% S/P ratio (

Supplementary Table S1). There was one animal #30 that had a baseline value of 72.38, and deemed to be positive, so that animal was kept in the final cohort of 12 within the unvaccinated control group. The three other sheep in the unvaccinated group had baseline values of 34.61, 16.48 and 23.74.

3.2.2. Screening of Sheep Cohort for Assignment of Vaccine and Control Groups by Evaluation of Cellular Baseline Responses to Concanavalin A and Recall Responses to Chlamydial Antigens

PBMC responses of LSAs to baseline bleeds at days -94 and -48 were used to identify suitable sheep for Study A. Sheep were selected based on high responses to ConA, low responses to COMC and EBs and negligible responses to media alone (

Supplementary Table S2). On the basis of the baseline serological MOMP and cellular IFN-γ response data, a suitable cohort of sheep was identified and assigned into experimental groups as described in section 2.6.

3.3. Humoral and Cellular Antigen-Driven Responses to MOMP Following Immunisation with ompA vaccines

3.3.1. Anti-MOMP IgG Responses

There were negligible anti-MOMP responses following PI (bleed 3,

Supplementary Table S1) for sheep in the mORFV-o

mpA group and the mMVV-

ompA group. However, at bleed 6 following the BI, three of the four mORFV-

ompA sheep had strong antibody titres of 157.96 %, 136.54 and 248.76 % S/P ratios. In the mMVV-

ompA group antibodies were elevated in two of the four sheep but only deemed to be borderline positive in a single animal with an S/P ratio of 57.11 % just below the 60 % S/P cut-off for positivity. The antibody level (expressed as S/P) of the post-abortion

C. abortus positive sheep was consistently over 400% (496.32, 498.58 and 439%).

3.3.2. Cellular IFN-γ Responses Following Vaccine-Delivered ompA

The responses across the groups were generally high for responses to the mitogen ConA and negligible to media alone (

Supplementary Table S2). Chlamydial antigen responses, where present, were generally stronger to the COMC antigen rather than the whole EB antigen throughout Study A. Following PI, two of the four mORFV-

ompA sheep had elevated IFN-γ responses to COMC beyond baseline values, whereas only one of the mMVV-

ompA sheep (#27) had such elevated responses. Consistently, two sheep in the mORFV-

ompA had elevated COMC responses but just a single mMVV-

ompA animal showed elevated responses inconsistently over the study from PI. Following the booster immunisation (BI), all four mORFV-

ompA sheep had elevated COMC-driven IFN-γ (

Supplementary table S2) at bleed 7 but just a single mMVV-

ompA sheep (#26) showed elevated responses over baseline levels.

Following analysis of the IgG-MOMP (

Supplementary Table S1) and COMC-specific IFN-γ responses (

Supplementary Table S2), the mORFV-

ompA group had a higher proportion of sheep (three of four; 75%) responding to the vaccine antigen post-booster immunisation (antibody and cellular responses in combination) than the mMVV-

ompA group (only one of four sheep responded with either elevated antibody or cellular IFN-γ). The magnitude of these humoral and cellular antigen-driven responses was also greater in the mORFV-

ompA group (

Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). Given these results, it was decided to progress with the mORFV-

ompA vaccine in a new cohort of sheep. Given that both live and inactivated parapox virus preparations are known to stimulate vaccine induced responses, we decided to assess β-propiolactone inactivated mORFV-

ompA alongside the live vector in the comprehensive follow-up immunogenicity Study B (

Figure 5).

3.4. Evaluation of mORFV-ompA Inactivation

The absence of CPE following three rounds of successive sub-culture of the inactivated virus in FLS cells was noted. Analyses of RNA from these cultured cells from three subcultures revealed specific mRNA, in the absence of gDNA, of transcripts encoding ompA from sub-culture round one only. This suggests that no viable mORFV-ompA was present following two rounds of β-propiolactone inactivation. It was not possible to titrate the inactivated mORFV-ompA. The live mORFV-ompA was titrated as previously described (in section 2.3 above).

3.5. Comprehensive Immunogenicity Evaluation of Live and Inactivated mORFV-ompA In Vivo in Sheep

3.5.1. Screening of Sheep Cohort for the Comprehensive Immunogenicity Study B Comparing Live and Inactivated mORFV-ompA

The final three groups of 10 sheep were identified from a cohort of 50 sheep on the basis of negative test results to the pestivirus screen (MRI Virus Surveillance Unit), negative MOMP-IgG responses (

Figure 5, bleeds 1 and 2) and specific PBMC IFN-γ responses across bleeds 1 and 2 (high to ConA, low/ negligible to COMC, EB and medium alone,

Supplementary Figures S2A-C and Table S4, bleeds 1 and 2).

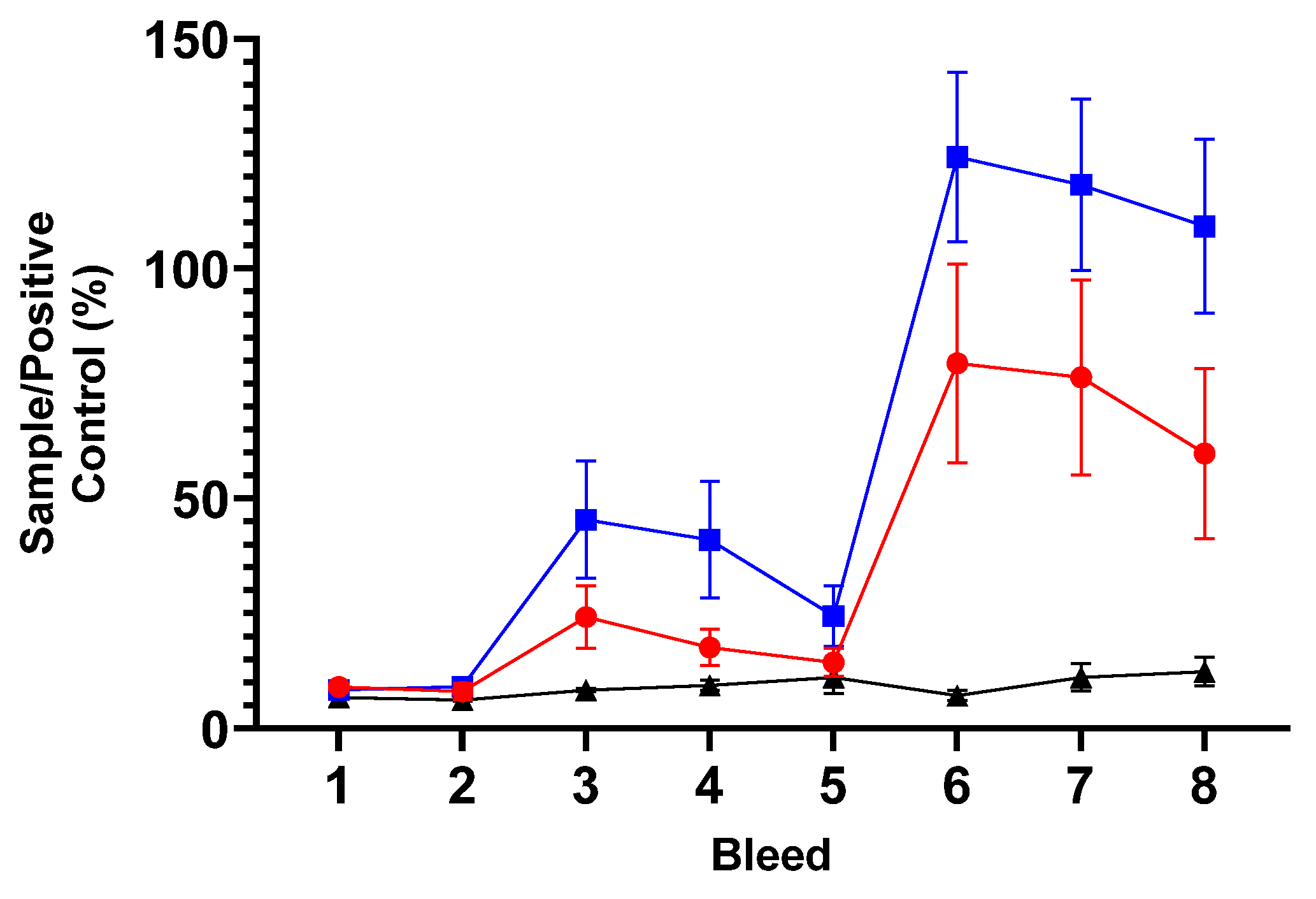

3.5.2. Humoral Responses to MOMP in ORFV-ompA Immunisation Study B

The mean antibody (whole IgG) response presented as S/P ratio for each vaccine group and control group are presented in

Figure 5 (raw data presented in

Supplementary Table S3). There were no responses across the groups pre-immunisation (bleeds 1 and 2) but an immediate significant increase observed in both vaccine groups PI (p< 0.0001, bleed 3,

Figure 5). The magnitude of the antibody response of the live vaccine was stronger than the inactivated vaccine but these were not significantly different to each other (p=0.0747). The response of the vaccine groups (Live and Inactivated mORFV-

ompA) started to drop slightly at bleed 4. At bleed 5, following the BI, there was a strong vaccine antigen-specific IgG response to both vaccines and again the magnitude of these responses in the Live Group was greater and this was maintained for the duration of the study (

Figure 5, bleeds 6-8). Again there is a significant increase in these vaccine responses (bleed 5 vs bleeds 6-8, p<0.0001) but not significantly different to each other (Live vs Inactivated mORFV-

ompA bleeds 6-8 p=0.5289).

3.5.3. Cellular Immune Responses

The mean cellular cytokine responses of IFN-γ, IL-17A, IL-10 and IL-4 for each vaccine and unvaccinated control group data are collated according to antigen and recall assay stimulation condition (medium, COMC, EB and ConA) in

Supplementary Tables S4 (IFN-γ), S5 γ (IL-17A), S6 (IL-10) and S7 (IL-4) with only the medium and ConA are presented in bar graphs for each cytokine in separate

Supplementary Figures (IFN-γ,

Figure S2; IL-17A,

Figure S3; IL-10,

Figure S4 and IL-4,

Figure S5). Pre-immunisation sample point (bleeds 1 and 2) were negligible for medium alone and the chlamydial antigen whole EBs and strong consistent ConA responses across groups for IFN-γ, IL-17A, IL-10 and IL-4 except for isolated IL-4 response to media alone sample point bleed 2 for the Live mORV-

ompA group (

Supplementary Tables S4–S7). This showed that the cohort of sheep in each group had appropriate baseline responses to the vaccine antigen and capability to respond strongly to the T cell mitogen ConA (

Supplementary Figures S2–S5).

Across Study B responses to medium alone remained at baseline levels broadly for all sample points for each cytokine (

Supplementary Figures: S2 for IFN-γ,

S3 for IL-17A,

S4 for IL-10 and

S5 for IL-4). The polyclonal T cell responses to ConA served as a positive control in the lymphocyte stimulation assays and have shown consistent cytokine production between the vaccine and unvaccinated groups (

Supplementary Figures: S2 for IFN-γ; p=0.3639,

S3 for IL-17A; p=0.2095;

S4 for IL-10, p=0.2177; and

S5 for IL-4, p=0.2095) but marginal variable responses between groups over time for IFN-γ (p=0.0464) but not the other cytokines (IL-17A, p= 0.2019; IL-10=0.7726 and IL-4, p= 0.1819).

3.5.4. Cellular Immune Responses to the MOMP Antigen in Sheep Following Immunisation with mORFV-ompA

The mean cellular IFN-γ, IL-17A, IL-10 and IL-4 responses to the chlamydial antigens COMC and whole EB both showed vaccine-induced responses but there was a level of background for EB IFN-γ responses, prior to PI. No EB responses above baseline across the groups and time were observed for IL-17A, IL-10 and IL-4. For these reasons the EB response has been presented as raw data (

Supplementary Tables only:

S4 for IFN-γ,

S5 for IL-17A,

S6 for IL-10 and

S7 for IL-4).

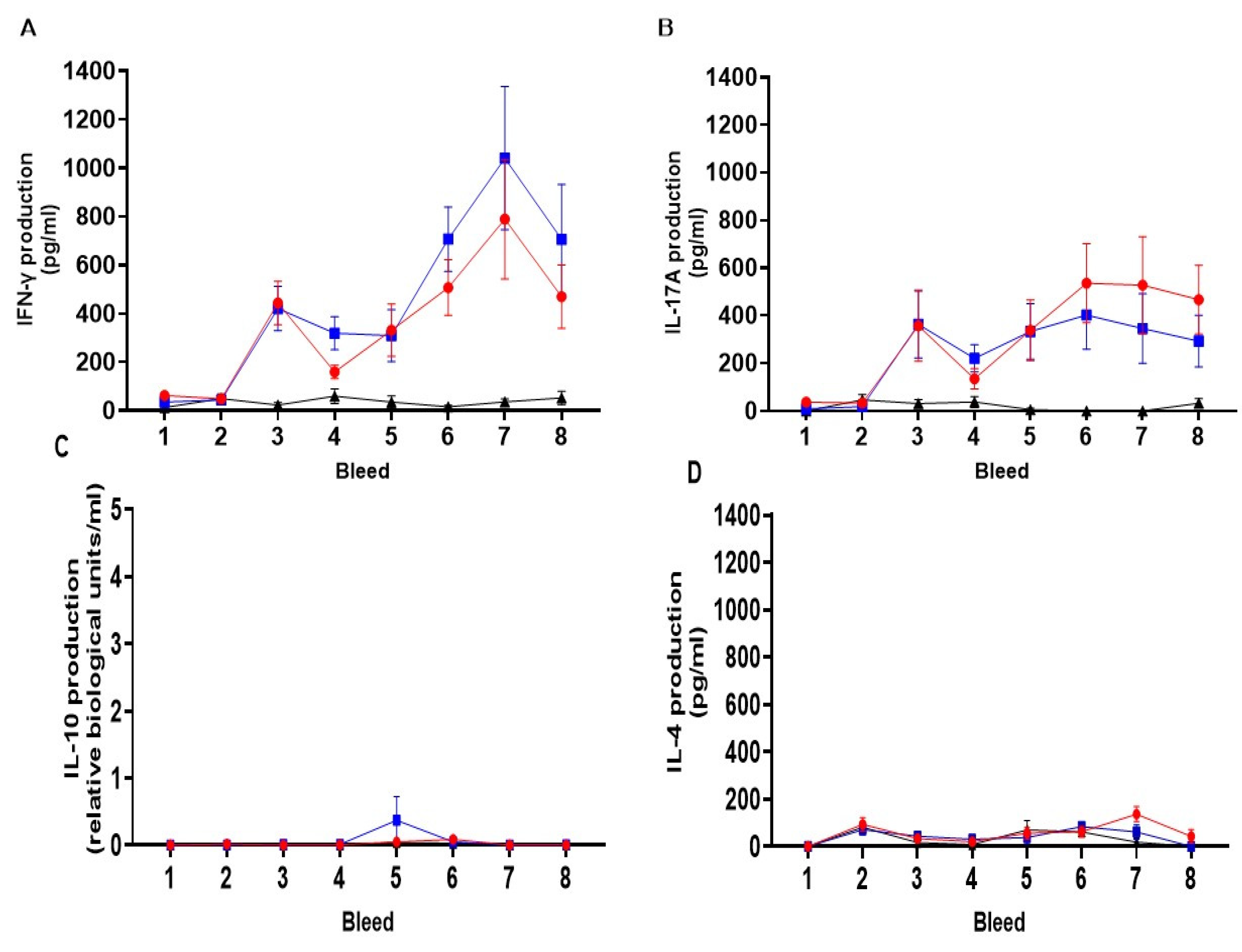

The mean cellular IFN-γ responses to the chlamydial antigen COMC for each vaccine group and control group are presented in

Figure 6A. There was a difference between the experimental groups (p<0.0001), in the responses observed over time (p<0.0001) and divergence of responses to vaccinations over time over the unvaccinated control group (p<0.0001). There were no COMC-specific responses detected across the groups pre-immunisation (

Figure 6A-D, bleeds 1 and 2). Within two weeks of PI, there was a significant upregulation of COMC-IFN-γ response observed in both vaccine groups over the unvaccinated control group (

Figure 6A, bleed 3, Live and Inactivated Group vs unvaccinated control group p< 0.001). These elevated vaccine-antigen recall responses were broadly maintained in the Live group but responses were more variable in the inactivated group (bleeds 3, 4 and 5, Live vs Inactivated mORFV-

ompA Groups). In response to BI, there was a gradual but significant increase in the COMC-IFN-γ response in the vaccine groups peaking at bleed 7 (approx. 4 weeks BI). The Live mORFV-

ompA Group had a stronger mean response BI than the Inactivated ORFV-

ompA Group but the levels were not significantly different to each other. Over the entire study, there was no difference in the COMC-IFN-γ response between the Live and Inactivated Groups (p=0.9391).

The mean cellular IL-17A response to COMC from all groups is presented in

Figure 6B above. There was a significant difference between the groups (p<0.0039) overall that is in response to the vaccinations over time (p<0.0001). Again there was divergence over time between the vaccine groups and the unvaccinated group (p=0.0002). The responses pre-immunisation were negligible (

Figure 6B, bleeds 1 and 2) but following PI, IL-17A is primed in both Live and Inactivated mORFV-

ompA groups (Bleeds 1, 2 vs 3 p=0.0002) to a similar level as the IFN-γ response (Bleed 3

Figure 6A, B). A consistent pattern of the PI IL-17A responses were observed, similar to the between PI and BI IFN-γ responses in both vaccine groups (Bleeds 3-5,

Figure 6B, A). Following BI, the IL-17A response in the Live group is maintained and slightly elevated in the Inactivated group but no significant difference between vaccine groups over time were determined (p=0.332).

Analysis of the mean regulatory IL-10 group responses (

Figure 6C) and the mean anti-inflammatory IL-4 responses (

Figure 6D) to the COMC antigen revealed no elevation of responses to both immunisations in each Live or inactivated vaccine group above those observed to prior to immunisation (IL-10 between group comparison,

Figure 6C, p=0.501; IL-4 between group comparison,

Figure 6D, p= 0.1299). Incidentally, the magnitude of these responses was at the sensitivity limit of both IL-10 and IL-4 ELISAs.

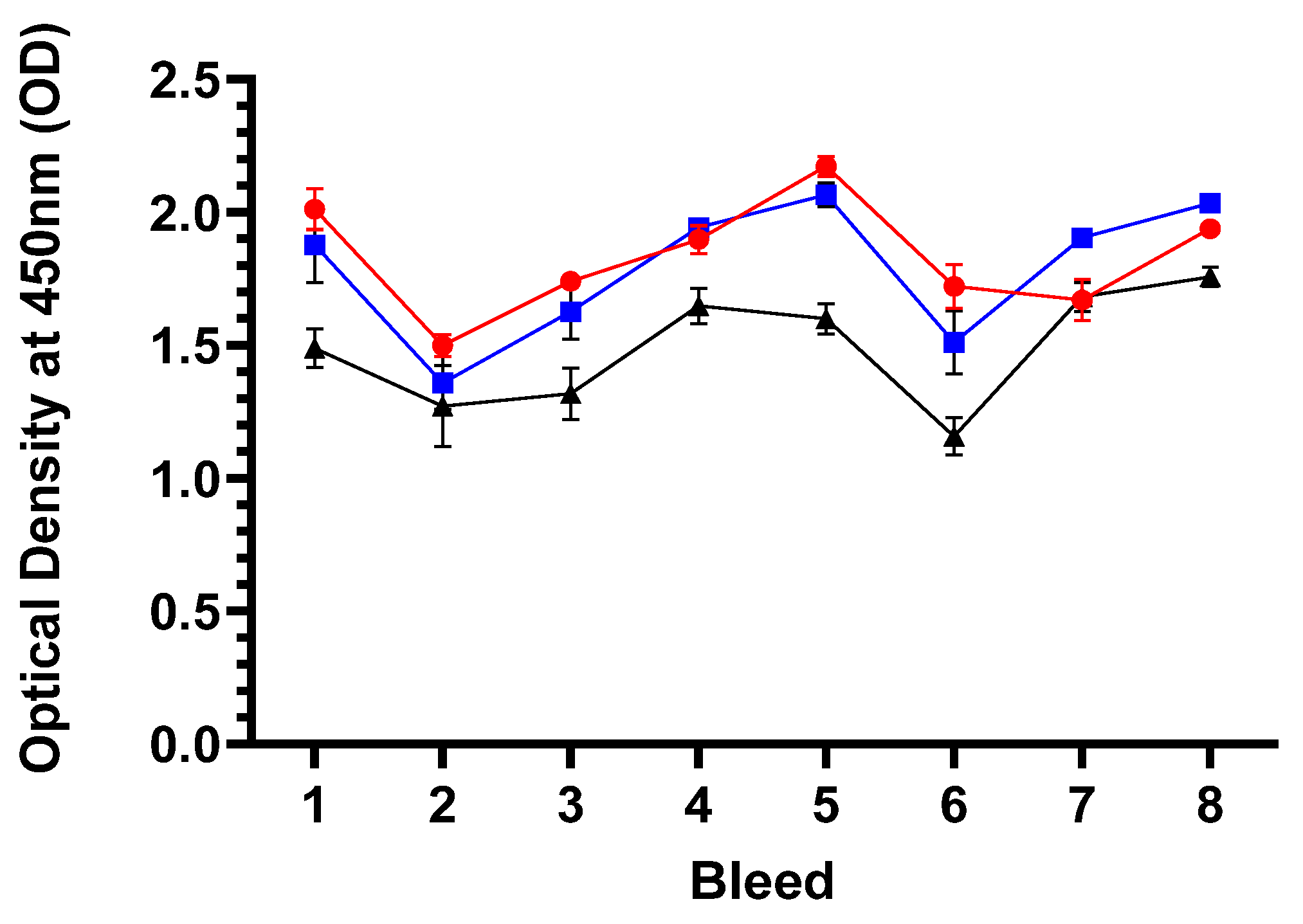

3.5.5. Humoral Responses to the Vaccine Backbone, ORFV

The mean specific antibody (IgG) responses to ORFV for each group are presented in

Figure 7 and the raw data is included in

Supplementary Table S8. Analyses of the IgG responses to ORFV revealed a high degree of variability between all three groups (both vaccine groups and unvaccinated control, p=0.0005) and between the groups for the duration of the study (p< 0.0001). Analysis of the pre-immunisation bleeds 1 and 2 revealed that all sheep across the three groups had antibodies to ORFV and this is suggestive of prior exposure to the virus. It seems that the unvaccinated group had slightly lower responses in these pre-immunisation sample points than the Live and Inactivated vaccine groups. This response was around an OD of 1.5 and remained fairly constant over the duration of the study apart from a transient drop at bleed 6 found also across the vaccine groups as well. For the Live and Inactivated groups the responses started at around an OD of 1.9 to 2.1 and deviated by ODs of 0.5 over time. There was no consistent additive response to ORFV following immunisations (PI and BI) of both vaccine groups suggesting the vaccines are not stimulating responses to the Live or Inactivated mORFV vector backbone. Overall, there was no divergent responses between the Live and Inactivated vaccine group responses over the study (p=0.5543) or indeed between the three groups together over time (p=0.7743) and are quite different to the antibody response to the MOMP antigen post immunisation(s).

4. Discussion

The aims of this project were to develop prototype vaccines using modified virus vector platform technologies, derived from ORFV and MVV to determine their potential utility in delivering a bacterial

C. abortus protein as a transgene product and stimulate potentially protective immune responses in sheep. The MOMP protective antigen has formed the basis of many prototype chlamydial vaccines across human, farm animal and wildlife developmental vaccines. It comprises approximately 60% by protein weight of the outer surface of known adjuvanted experimental COMC-based vaccines [

30,

31]. The prototype mORFV-

ompA and mMVV-

ompA vaccines were both shown to incorporate the

ompA gene with demonstrable expression of MOMP in vitro in susceptible cells. A direct comparison of these vaccines in sheep showed that they both stimulated antigen-specific IgG and cellular IFN-γ in at least 50% of the immunised sheep. This is the first report of a direct comparison of modified endemic UK sheep viruses (ORFV and MVV) stimulating immune responses to foreign transgenes in vivo in sheep. The humoral responses were stronger to the ORFV-based vaccine following the BI in the primary Study A, but wider conclusions about relative vaccine platform performance should be drawn with caution given the group sizes here. This is especially the case for sheep antibody responses to the MOMP vaccine antigen used in this project, since it has been previously reported that not all post-abortion sheep respond to MOMP, following experimental inoculation with

C. abortus [

45,

46,

47].

The cellular IFN-γ response to immunisation with mORFV-

ompA was again stronger than the mMVV-

ompA response for the number of responding animals and magnitude of this response. For mMVV-

ompA the cellular IFN-γ response was rather limited and highly variable. This could be a reflection of the cellular assay system used to assess the cellular immune responses and/or a reflection of differences in the capacity of each platform to stimulate responses to the vaccine antigen here. Both ORF and MVV are known to target different cells in sheep. ORF is epitheliotrophic and MVV is known to target antigen presenting cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells [

48,

49]. It could be that one or both vaccine platforms are more suited to stimulating CD8 T cell responses rather than the predominant responses measured in a PBMC restimulation assay such as CD4 T, natural killer and gamma-delta T cells. Amann et al. has shown ORFV to stimulate both CD4 and CD8 T cell responses in non-permissive hosts [

50]. Further investigations are required to fully evaluate the relative capacities of these platforms for stimulating immune responses in a larger cohort of animals. This dataset demonstrates that both vaccine platforms are able to deliver a bacterial antigen that primes an antigen-driven immune response in vivo. The mMVV-

ompA system has been shown to transduce ovine monocyte-derived dendritic cells in vitro leading to release of IL-1beta and production of apoptotic bodies. Immature dendritic cells have then been capable of stimulating IFN-γ production in T cells [

29].

Following on from the promising results of the mORFV-

ompA in Study A, where there had been some evidence of prior

C. abortus exposure within the cohort of sheep used, a wider investigation of the utility of this parapox-based vaccine in a new cohort of sheep, derived from OEA-free Scottish Premium Health Scheme flocks was undertaken. Here in a larger cohort of sheep the capacity of both Live and Inactivated vaccines to stimulate MOMP-antibody and the quality of the antigen-driven CD4 T cell responses was evaluated. The vaccines stimulated a humoral response to MOMP observed PI but much stronger post BI. The Live vaccine elicited a higher observed response following immunisation but this was not statistically significant. In terms of utility as a vaccine platform, the ability to stimulate antibody responses using inactivated preparations adds to the safety profile of this type of vaccine, especially increasing potential opportunities for deployment. Incidentally, for the control of

C. abortus in ovine chlamydiosis (ovine enzootic abortion), antibody responses are considered to play a minor role in control in sheep but could be important in preventing re-infection [

47].

The evaluation of the quality or balance of the antigen-driven cellular immune response to these vaccines was undertaken to determine the comprehensive balance of the CD4 T cell signature cytokines stimulated. The Live vaccine stimulated a strong balance of IFN-γ and IL-17A following the two-dose regimen with no observable production of IL-10 or IL-4. This type of dominant T-helper (Th)-1/Th-17 biased response has been associated with host responses to chlamydial infections at various levels of disease severity across human, farm animal and wildlife hosts [

40,

51,

52]. IFN-γ is well regarded as the key cytokine responsible for controlling chlamydial species and within a Th-1 targeted vaccine-induced response to the current live

C. abortus vaccines [

11,

31].

Emerging evidence has identified that IL-17A in isolation can be partially protective in a rodent vaccine-challenge model of

C. trachomatis on Th-1 deficient background [

53]. In addition, an immunogenicity trial using an adjuvanted

C. trachomatis chlamydial protease activity factor vaccine showed elevated IFN-γ and IL-17A in immunised pigs [

54]. Together with recently published vaccine-challenge study data from our group, where we showed that the prototype COMC vaccine adjuvanted with ISA VG 70 (Seppic, Paris, France) stimulated IFN-γ, negligible IL-10 and IL-4 in cellular assays to COMC antigen in sheep protected from OEA [

31], this suggests that this platform may be useful for the development of a next generation vaccine to OEA.

Both the Live and Inactivated vaccines in this study stimulated a similar cellular immune response with subtle differences in the relative levels of IFN-γ and IL-17A post BI. Further investigations are required to determine what the alterations in these levels could mean for potential protection against OEA. If efficacious, the use of an inactivated ORFV-ompA vaccine has the potential to increase the safety profile of this virus vector construct-based type of vaccine.

One of the major features of using ORFV-based vaccines is that previous exposure does not prevent re-infection with virus. Therefore, it is believed that any ORFV-specific responses induced could be less problematic than other viral vaccine vectors where the immune response to the vector could inhibit it from expressing the ‘vaccine/foreign antigen’ [

15,

16]. In this study, the vaccine-induced humoral and cellular immune responses were conferred in sheep despite prior exposure to ORFV and systemic IgG-ORFV. Valuable immunogenicity data is presented here that adds to the portfolio of information available on parapox vaccine platforms for the magnitude and quality of vaccine-induced immune responses. This contributes valuable data and knowledge towards a dossier of information contributing to a Platform Technology Master File. This would accelerate the route to market for vaccines based on known platform technologies for future next generation vaccine registration through the European Medicines Agency [

11,

55]. Such a platform technology could be helpful for tackling new and emerging chlamydial strains that may cause issues in pregnant animals or be potentially zoonotic such as the intermediate avian

C. abortus strains [

56].

The utility of poxvirus-based vaccines is already widely adopted in commercial vaccines for pets and food animals, including the trivalent vaccine to myxomatosis and rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus genotypes 1 and 2 [

57]. Therefore, many of the potential barriers to commercialisation of such a vaccine platform for use in veterinary species such as scalability, formulation and purification have already been evaluated [

58,

59,

60].

5. Conclusions

A mORFV-ompA vaccine delivered as a live or inactivated preparation has the ability to stimulate MOMP bacterial antigen expression in sheep despite prior exposure to ORFV. The presence of vector-specific immunity (ORFV-specific IgG) did not change following immunisation and did not prevent responses to the vaccine antigen MOMP. Immunisation following a two-dose regimen stimulated both systemic IgG to MOMP and antigen-specific cellular responses dominated by IFN-γ and IL-17A production, immune response signatures shown previously to be protective against chlamydial disease in representative vaccine-challenge models. These mORFV-ompA prototype vaccines offer the possibility of a new generation of vaccines to bacterial pathogens for sheep. If efficacious the inactivated vaccines offer enhanced levels of safety providing greater opportunities for potential deployment.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Figure S1: OmpA (mRNA) and OmpA-Flag protein expression of ompA-based vaccines in vitro; Table S1: Study A MOMP antibody data for three bleeds; Table S2: Cellular IFN-γ immune antigen recall responses, Study A; Figure S2: IFN-γ responses of PBMC from sheep grouped by vaccination group in Study B; Table S3: MOMP antibody data, Study B; Table S4: IFN-γ responses of PBMC, Study B; Table S5: IL-17A responses of PBMC, Study B; Table S6: IL-10 responses of PBMC, Study B; Table S7: IL-4 responses of PBMC, Study B; Figure S3: IL-17A responses of PBMC from sheep grouped by vaccination group in Study B; Figure S4: IL-10 responses of PBMC from sheep grouped by vaccination group in Study B; Figure S5: IL-4 responses of PBMC from sheep grouped by vaccination group in Study B.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.R.W., G.E., D.L, D.J.G., and C.J.M.; methodology, S.R.W., J.T., D.J.G., and C.J.M.; validation, S.R.W. and J.P.-A.; formal analysis, S.R.W., J.P.-A., C.J.M.; investigation, S.R.W., J.T., L.C., A.W., H.H., C.C., K.S., R.K.M., A.P., G.E., D.J.G., and C.J.M.; data curation, S.R.W., J.T., L.C., A.W., A.P., H.H., R.K.M. and C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, S.R.W., D.L., J.P.-A., D.J.G., and C.J.M.; writing—review and editing, S.R.W., D.L., G.E., J.P.-A., D.J.G., and C.J.M.; visualization, S.R.W., D.J.G., and C.J.M.; supervision, S.R.W., D.J.G., and C.J.M.; project administration, S.R.W., D.J.G., and C.J.M.; funding acquisition, S.R.W., G.E., D.J.G., and C.J.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Scottish Government Rural and Environment Science and Analytical Services (RESAS) division. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, in strict accordance with the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986, in compliance with all UK Home Office Inspectorate regulations and ARRIVE guidelines 2.0 and was approved by the Institutional Animal Welfare Ethical Review Body of Moredun Research Institute (permit number: E52/18; date of approval: 25th October 2018 and permit number: E48/19; date of approval: 22nd October 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article or

supplementary material. The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/

supplementary material, and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Moredun Bioservices for their expert handling, care and welfare of the animals in this study. Images in Figures 1-4 in this manuscript were created using BioRender.

Conflicts of Interest

D.J.G. and R.K.M. are named as inventors on a patent application relating to the use of the MVV vectors described in this study.

References

- Draper, S.J.; Heeney, J.L. Viruses as vaccine vectors for infectious diseases and cancer. Nat Rev Microbiol 2010, 8, 62-73. [CrossRef]

- Ghattas, M.; Dwivedi, G.; Lavertu, M.; Alameh, M.G. Vaccine Technologies and Platforms for Infectious Diseases: Current Progress, Challenges, and Opportunities. Vaccines (Basel) 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- Yong, L.; Hutchings, C.; Barnes, E.; Klenerman, P.; Provine, N.M. Distinct Requirements for CD4(+) T Cell Help for Immune Responses Induced by mRNA and Adenovirus-Vector SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines. European journal of immunology 2025, 55, e202451142. [CrossRef]

- Condit, R.C.; Williamson, A.-L.; Sheets, R.; Seligman, S.J.; Monath, T.P.; Excler, J.-L.; Gurwith, M.; Bok, K.; Robertson, J.S.; Kim, D.; et al. Unique safety issues associated with virus-vectored vaccines: Potential for and theoretical consequences of recombination with wild type virus strains. Vaccine 2016, 34, 6610-6616. [CrossRef]

- McCann, N.; O’Connor, D.; Lambe, T.; Pollard, A.J. Viral vector vaccines. Curr Opin Immunol 2022, 77, 102210. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tian, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, H.; Zhang, G. Current Status of Poultry Recombinant Virus Vector Vaccine Development. Vaccines 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Entrican, G.; Bredell, H.; Charlier, J.; Cunningham, A.F.; Jarvis, M.A.; Wood, P.R.; Wren, B.W.; Hope, J.C. Opportunities and challenges for the adoption of novel platform technologies to develop veterinary bacterial vaccines. Vaccine 2025, 54, 127117. [CrossRef]

- Health, S.-I.I.R.C.o.A. Global Veterinary Vaccinology Research and Innovation Landscape Survey Report; 2022.

- Confer, A.W.; Ayalew, S. The OmpA family of proteins: Roles in bacterial pathogenesis and immunity. Veterinary Microbiology 2013, 163, 207-222. [CrossRef]

- Olsen, A.W.; Rosenkrands, I.; Holland, M.J.; Andersen, P.; Follmann, F. A Chlamydia trachomatis VD1-MOMP vaccine elicits cross-neutralizing and protective antibodies against C/C-related complex serovars. NPJ Vaccines 2021, 6, 58. [CrossRef]

- Entrican, G.; Wheelhouse, N.; Wattegedera, S.R.; Longbottom, D. New challenges for vaccination to prevent chlamydial abortion in sheep. Comp Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis 2012, 35, 271-276. [CrossRef]

- Desclozeaux, M.; Robbins, A.; Jelocnik, M.; Khan, S.A.; Hanger, J.; Gerdts, V.; Potter, A.; Polkinghorne, A.; Timms, P. Immunization of a wild koala population with a recombinant Chlamydia pecorum Major Outer Membrane Protein (MOMP) or Polymorphic Membrane Protein (PMP) based vaccine: New insights into immune response, protection and clearance. PloS one 2017, 12, e0178786. [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.W.; Herring, A.J.; Anderson, I.E.; Jones, G.E. Protection of sheep against Chlamydia psittaci infection with a subcellular vaccine containing the major outer membrane protein. Infection and immunity 1990, 58, 3101-3108. [CrossRef]

- Mercer, A.A.; Norihito, U.A.; Sonja-Maria, F.B.; Hofmann, K.; Fraser, K.M.; Bateman, T.; Fleming, S.B. Comparative analysis of genome sequences of three isolates of Orf virus reveals unexpected sequence variation. Virus Research 2006, 116, 146-158. [CrossRef]

- Haig, D.M.; McInnes, C.J. Immunity and counter-immunity during infection with the parapoxvirus orf virus. Virus research 2002, 88, 3-16. [CrossRef]

- Travieso, T.; Li, J.; Mahesh, S.; Mello, J.; Blasi, M. The use of viral vectors in vaccine development. NPJ Vaccines 2022, 7, 75. [CrossRef]

- Moss, B. Poxvirus DNA replication. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 2013, 5. [CrossRef]

- Pincha, M.; Sundarasetty, B.S.; Stripecke, R. Lentiviral vectors for immunization: an inflammatory field. Expert Rev Vaccines 2010, 9, 309-321. [CrossRef]

- Shaw, A.; Cornetta, K. Design and Potential of Non-Integrating Lentiviral Vectors. Biomedicines 2014, 2, 14-35. [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, M.C.; Frenkiel, M.P.; Mollier, K.; Souque, P.; Despres, P.; Charneau, P. A single immunization with a minute dose of a lentiviral vector-based vaccine is highly effective at eliciting protective humoral immunity against West Nile virus. J Gene Med 2006, 8, 265-274. [CrossRef]

- García-Nicolás, O.; Ricklin, M.E.; Liniger, M.; Vielle, N.J.; Python, S.; Souque, P.; Charneau, P.; Summerfield, A. A Japanese Encephalitis Virus Vaccine Inducing Antibodies Strongly Enhancing In Vitro Infection Is Protective in Pigs. Viruses 2017, 9. [CrossRef]

- Gallinaro, A.; Borghi, M.; Bona, R.; Grasso, F.; Calzoletti, L.; Palladino, L.; Cecchetti, S.; Vescio, M.F.; Macchia, D.; Morante, V.; et al. Integrase Defective Lentiviral Vector as a Vaccine Platform for Delivering Influenza Antigens. Frontiers in immunology 2018, 9, 171. [CrossRef]

- Grasso, F.; Negri, D.R.; Mochi, S.; Rossi, A.; Cesolini, A.; Giovannelli, A.; Chiantore, M.V.; Leone, P.; Giorgi, C.; Cara, A. Successful therapeutic vaccination with integrase defective lentiviral vector expressing nononcogenic human papillomavirus E7 protein. Int J Cancer 2013, 132, 335-344. [CrossRef]

- Coutant, F.; Sanchez David, R.Y.; Félix, T.; Boulay, A.; Caleechurn, L.; Souque, P.; Thouvenot, C.; Bourgouin, C.; Beignon, A.S.; Charneau, P. A nonintegrative lentiviral vector-based vaccine provides long-term sterile protection against malaria. PloS one 2012, 7, e48644. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Sohn, H.J.; Lee, J.; Yang, H.J.; Chwae, Y.J.; Kim, K.; Park, S.; Shin, H.J. Vaccination with lentiviral vector expressing the nfa1 gene confers a protective immune response to mice infected with Naegleria fowleri. Clinical and vaccine immunology: CVI 2013, 20, 1055-1060. [CrossRef]

- Mortazavidehkordi, N.; Fallah, A.; Abdollahi, A.; Kia, V.; Khanahmad, H.; Najafabadi, Z.G.; Hashemi, N.; Estiri, B.; Roudbari, Z.; Najafi, A.; et al. A lentiviral vaccine expressing KMP11-HASPB fusion protein increases immune response to Leishmania major in BALB/C. Parasitol Res 2018, 117, 2265-2273. [CrossRef]

- Karponi, G.; Kritas, S.; Petridou, E.; Papanikolaou, E. Efficient Transduction and Expansion of Ovine Macrophages for Gene Therapy Implementations. Vet Sci 2018, 5. [CrossRef]

- Braun, M.J.; Clements, J.E.; Gonda, M.A. The visna virus genome: evidence for a hypervariable site in the env gene and sequence homology among lentivirus envelope proteins. J Virol 1987, 61, 4046-4054. [CrossRef]

- McLean, R.K. Development of a novel lentiviral vaccine vector and characterisation of in vitro immune responses. The University of Edinburgh, 2018.

- Longbottom, D.; Livingstone, M.; Aitchison, K.D.; Imrie, L.; Manson, E.; Wheelhouse, N.; Inglis, N.F. Proteomic characterisation of the Chlamydia abortus outer membrane complex (COMC) using combined rapid monolithic column liquid chromatography and fast MS/MS scanning. PloS one 2019, 14, e0224070. [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, M.; Aitchison, K.; Palarea-Albaladejo, J.; Ciampi, F.; Underwood, C.; Paladino, A.; Chianini, F.; Entrican, G.; Wattegedera, S.R.; Longbottom, D. Protective Efficacy of Decreasing Antigen Doses of a Chlamydia abortus Subcellular Vaccine Against Ovine Enzootic Abortion in a Pregnant Sheep Challenge Model. Vaccines (Basel) 2025, 13. [CrossRef]

- Deane, D.; McInnes, C.J.; Percival, A.; Wood, A.; Thomson, J.; Lear, A.; Gilray, J.; Fleming, S.; Mercer, A.; Haig, D. Orf virus encodes a novel secreted protein inhibitor of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-2. J Virol 2000, 74, 1313-1320. [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, D.J.M., Rebecca Kathryn. Small ruminant lentivirus vector. World patent application WO2020225150A1 patent. 2020.

- Ballandras-Colas, A.; Chivukula, V.; Gruszka, D.T.; Shan, Z.; Singh, P.K.; Pye, V.E.; McLean, R.K.; Bedwell, G.J.; Li, W.; Nans, A.; et al. Multivalent interactions essential for lentiviral integrase function. Nature communications 2022, 13, 2416. [CrossRef]

- Clapham, P.R.; McKnight, A.; Weiss, R.A. Human immunodeficiency virus type 2 infection and fusion of CD4-negative human cell lines: induction and enhancement by soluble CD4. J Virol 1992, 66, 3531-3537. [CrossRef]

- Reed, L.J.; Muench, H. A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints. 1938.

- Percie du Sert, N.; Hurst, V.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.C.; Dirnagl, U.; et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: updated guidelines for reporting animal research. J Physiol 2020, 598, 3793-3801. [CrossRef]

- SRUC. Premium Sheep & Goat Health Scheme. Available online: https://www.sruc.ac.uk/business-services/veterinary-laboratory-services/premium-sheep-goat-health-scheme/ (accessed on 13/05/2025).

- Wilson, K.; Livingstone, M.; Longbottom, D. Comparative evaluation of eight serological assays for diagnosing Chlamydophila abortus infection in sheep. Vet Microbiol 2009, 135, 38-45. [CrossRef]

- Wattegedera, S.R.; Livingstone, M.; Maley, S.; Rocchi, M.; Lee, S.; Pang, Y.; Wheelhouse, N.M.; Aitchison, K.; Palarea-Albaladejo, J.; Buxton, D.; et al. Defining immune correlates during latent and active chlamydial infection in sheep. Veterinary research 2020, 51, 75. [CrossRef]

- McKeever, D.J.; Reid, H.W.; Inglis, N.F.; Herring, A.J. A qualitative and quantitative assessment of the humoral antibody response of the sheep to orf virus infection. Vet Microbiol 1987, 15, 229-241. [CrossRef]

- Donachie, W.a.J., G.E. The use of ELISA to detect antibodies to Pasteurella haemolytica A2 and Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae in sheep with experimental chronic pneumonia. In The ELISA: Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay in Veterinary Research and Diagnosis, Wardley, R.C.a.C., J.R., Ed.; MArtinus Nijhoff: The Hague/Boston/London, 1982; pp. 102-110.

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. B 1995, 57, 289-300. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. The R Project for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.r-project.org (accessed on 08 October 2024).

- Huang, H.S.; Tan, T.W.; Buxton, D.; Anderson, I.E.; Herring, A.J. Antibody response of the ovine lymph node to experimental infection with an ovine abortion strain of Chlamydia psittaci. Vet Microbiol 1990, 21, 345-351. [CrossRef]

- Longbottom, D.; Russell, M.; Dunbar, S.M.; Jones, G.E.; Herring, A.J. Molecular cloning and characterization of the genes coding for the highly immunogenic cluster of 90-kilodalton envelope proteins from the Chlamydia psittaci subtype that causes abortion in sheep. Infection and immunity 1998, 66, 1317-1324. [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, M.; Entrican, G.; Wattegedera, S.; Buxton, D.; McKendrick, I.J.; Longbottom, D. Antibody responses to recombinant protein fragments of the major outer membrane protein and polymorphic outer membrane protein POMP90 in Chlamydophila abortus-infected pregnant sheep. Clin. Diagn. Lab Immunol 2005, 12, 770-777.

- Gorrell, M.D.; Brandon, M.R.; Sheffer, D.; Adams, R.J.; Narayan, O. Ovine lentivirus is macrophagetropic and does not replicate productively in T lymphocytes. J Virol 1992, 66, 2679-2688. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, S.; Tiley, L.; McConnell, I.; Blacklaws, B. Infection of dendritic cells by the Maedi-Visna lentivirus. J Virol 2000, 74, 10096-10103. [CrossRef]

- Amann, R.; Rohde, J.; Wulle, U.; Conlee, D.; Raue, R.; Martinon, O.; Rziha, H.J. A new rabies vaccine based on a recombinant ORF virus (parapoxvirus) expressing the rabies virus glycoprotein. J Virol 2013, 87, 1618-1630. [CrossRef]

- Jha, R.; Srivastava, P.; Salhan, S.; Finckh, A.; Gabay, C.; Mittal, A.; Bas, S. Spontaneous secretion of interleukin-17 and -22 by human cervical cells in Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Microbes and infection / Institut Pasteur 2011, 13, 167-178. [CrossRef]

- Mathew, M.; Waugh, C.; Beagley, K.W.; Timms, P.; Polkinghorne, A. Interleukin 17A is an immune marker for chlamydial disease severity and pathogenesis in the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus). Developmental and comparative immunology 2014, 46, 423-429. [CrossRef]

- Olsen, A.W.; Rosenkrands, I.; Jacobsen, C.S.; Cheeseman, H.M.; Kristiansen, M.P.; Dietrich, J.; Shattock, R.J.; Follmann, F. Immune signature of Chlamydia vaccine CTH522/CAF®01 translates from mouse-to-human and induces durable protection in mice. Nature communications 2024, 15, 1665. [CrossRef]

- Proctor, J.; Stadler, M.; Cortes, L.M.; Brodsky, D.; Poisson, L.; Gerdts, V.; Smirnov, A.I.; Smirnova, T.I.; Barua, S.; Leahy, D.; et al. A TriAdj-Adjuvanted Chlamydia trachomatis CPAF Protein Vaccine Is Highly Immunogenic in Pigs. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Entrican, G.; Francis, M.J. Applications of platform technologies in veterinary vaccinology and the benefits for one health. Vaccine 2022, 40, 2833-2840. [CrossRef]

- De Meyst, A.; Aaziz, R.; Pex, J.; Braeckman, L.; Livingstone, M.; Longbottom, D.; Laroucau, K.; Vanrompay, D. Prevalence of New and Established Avian Chlamydial Species in Humans and Their Psittacine Pet Birds in Belgium. Microorganisms 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Reemers, S.; Peeters, L.; van Schijndel, J.; Bruton, B.; Sutton, D.; van der Waart, L.; van de Zande, S. Novel Trivalent Vectored Vaccine for Control of Myxomatosis and Disease Caused by Classical and a New Genotype of Rabbit Haemorrhagic Disease Virus. Vaccines (Basel) 2020, 8. [CrossRef]

- Pagallies, F.; Labisch, J.J.; Wronska, M.; Pflanz, K.; Amann, R. Efficient and scalable clarification of Orf virus from HEK suspension for vaccine development. Vaccine: X 2024, 18, 100474. [CrossRef]

- Eilts, F.; Labisch, J.J.; Orbay, S.; Harsy, Y.M.J.; Steger, M.; Pagallies, F.; Amann, R.; Pflanz, K.; Wolff, M.W. Stability studies for the identification of critical process parameters for a pharmaceutical production of the Orf virus. Vaccine 2023, 41, 4731-4742. [CrossRef]

- Lothert, K.; Pagallies, F.; Eilts, F.; Sivanesapillai, A.; Hardt, M.; Moebus, A.; Feger, T.; Amann, R.; Wolff, M.W. A scalable downstream process for the purification of the cell culture-derived Orf virus for human or veterinary applications. J Biotechnol 2020, 323, 221-230. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).