1. Introduction

Precise, non-invasive, and three-dimensional optical measurement is critical across a wide range of scientific and engineering disciplines, including thermal management in microfluidic devices [

1], diagnostics in combustion systems [

2], and biomedical imaging [

3]. Precise thickness and surface profiling of transparent and semi-transparent materials is critical for quality control, material characterization, and performance optimization across several applications [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Traditional contact-based methods, including micrometer, caliper, and contact profilometer for thickness measurement for a thin transparent film and thermocouples or resistance temperature detectors (RTDs) [

8] for temperature measurement, often disrupt the surface/thermal field they aim to measure and do not provide full-field information and are limited by spatial resolution and response time. These methods are often unsuitable for environments with rapid temporal or spatial temperature fluctuations [

8]. Consequently, there has been a growing demand for non-invasive optical techniques capable of measuring physical parameters with high accuracy, resolution, and temporal fidelity.

Among the non-invasive techniques, infrared (IR) thermography has gained prominence due to its ease of use and capability for real-time surface temperature monitoring [

9]. However, IR thermography is inherently limited to surface measurements and is sensitive to emissivity variations and environmental interferences. Optical interferometric techniques offer full-field and three-dimensional measurements, high resolution, and extremely high sensitivity to refractive index changes induced by temperature gradients [

10]. Digital holography [

11,

12,

13,

14] has emerged as a powerful tool for non-contact, full-field measurement of physical parameters, including thickness, deformation, displacement, vibration, refractive index, and temperature, due to its ability to record both the amplitude and phase of a light field in a single exposure. The phase information encodes optical path length changes, which can be directly related to refractive index variations caused by temperature gradients in a transparent or semi-transparent medium. Despite its advantages, the technique faces several limitations, typically it requires highly stable environmental conditions, complex optical alignments, and a limited field of view (FOV), therefore, limiting its applicability in dynamic or field environments. Therefore, the limited FOV is one of the inherent limitations of digital holography, primarily dictated by the trade-off between spatial resolution and detector size. Since digital holography relies on recording interference fringes on a pixelated sensor array, the maximum recoverable field is limited by the pixel pitch and the total number of pixels available [

15]. A general formula for the FOV can be derived considering the relationship between the sensor dimensions, pixel size, and the magnification factor:

Consequently, conventional digital holography systems often face a performance bottleneck where achieving both high resolution and wide FOV simultaneously becomes challenging. These limitations are particularly problematic for applications such as full-field thickness profiling, deformation, displacement, vibration, refractive index measurement, temperature mapping, large-scale biological imaging, and industrial inspection, where both high-resolution and wide-area coverage are essential.

However, several strategies have been proposed and developed to address the limited FOV in digital holography. Some of these methods are: multi-view holography [

16], synthetic aperture digital holography [

17], multiplexed digital holography [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33], computational methods [

34,

35], lens-based digital holography [

36,

37], etc. In multi-view digital holography [

16], by capturing holograms from multiple angles, either by sequentially moving the object or the image sensor, it is possible to stitch together a larger FOV without sacrificing resolution. This approach requires expensive mechanical equipment and time-consuming computations, making it unsuitable for investigating quick transient events. In synthetic aperture techniques [

17], holograms are captured at different positions, and the Fourier spectra are combined to effectively "synthesize" a larger aperture, extending both resolution and FOV beyond the physical sensor limits. Synthetic aperture digital holography can achieve ultra-high resolution imaging, though it typically requires mechanical scanning or precise stage control. Lens-based methods [

15,

37] for increasing the field of view require certain parameters such as focal length, location, and diameters, resulting in introducing the aberrations and making a bulkier system configuration.

In multiplexed holography, several wavefronts, often from different angles or wavelengths, are encoded onto a single hologram by careful carrier frequency design. This enables the simultaneous recovery of multiple fields, effectively expanding the observable FOV without increasing acquisition time. Continued improvements in detector technology, computational power, and optical system design are expected to further bridge the gap between high-resolution, wide-FOV imaging and real-time, robust holographic measurement for complex, dynamic systems such as turbulent thermal fields and biological tissues.

In this work, we experimentally demonstrated the application of a recently developed double FOV holographic system [

28] by our group for enhanced imaging, thickness measurement of glass plate, and phase mapping of candle flame. By simultaneously capturing holographic information from two distinct flames in a single-shot acquisition, we significantly increase the system's information capacity and spatial frequency coverage, resulting in improved object information characterization. The incorporation of high SBU ensures that the captured data fully exploits the available spatial frequencies, maximizing the effective resolution without necessitating complex optical setups or extensive computational post-processing.

This paper details the experimental setup and phase reconstruction methodology for the proposed system. Furthermore, the experimental results demonstrate its capability to achieve high-fidelity thickness measurement and phase mapping of candle flame. This multiplexing digital holographic approach provides a scalable, robust, and versatile solution for advanced optical metrology applications, extending the frontiers of digital holography-based surface profiling and temperature sensing.

2. Materials and Methods

Thickness measurement and surface profiling are essential for quality control, performance optimization, and material characterization in advanced manufacturing and research. They ensure precision and reliability in applications ranging from thin films to photonic and biomedical devices. Similarly, temperature measurement and optimization are crucial for quality control in various industries, such as plastic, automotive, food, ceramics, and textile. Optical methods are more appropriate and have been extensively employed for non-invasive deformation, surface profiling, refractive index, and temperature measurements by exploiting the dependence of phase. The non-contact techniques enable accurate characterization of transparent or delicate materials without physical interference, making them ideal for thin films, coatings, and photonic devices. Optical methods offer high resolution, speed, and repeatability, supporting innovation and reliability across industries such as semiconductors, optics, biomedical engineering, and materials science. Phase can be visualized optically via the Schlieren method and shadowgraph [

38]. These techniques work well for visualizing the phase object, however, it is challenging to measure phases quantitatively. Various optical methods, including holographic interferometry [

39,

40,

41], Moiré deflectometry [

42], laser speckle photography [

43], shearing interferometry [

44,

45], speckle interferometry [

46], digital holographic interferometry [

47,

48,

49,

50,

51] etc. are commonly employed to measure phase or phase difference and associated parameters such as deformation, displacement, strain, refractive index, density, and temperature. Digital holography-based optical methods for optical metrology are more appropriate than other optical methods because they are easier to implement, faster in operation, more resilient, and more precise and accurate. However, the limited FOV of the digital holographic systems is one of the major issues. Recently, we have developed a single-shot double FOV digital holographic approach for biomedical applications. In this work, the developed single-shot digital holographic system is verified for a scientific or industrial application by measuring the thickness of the glass plate and phase distribution of candle flame.

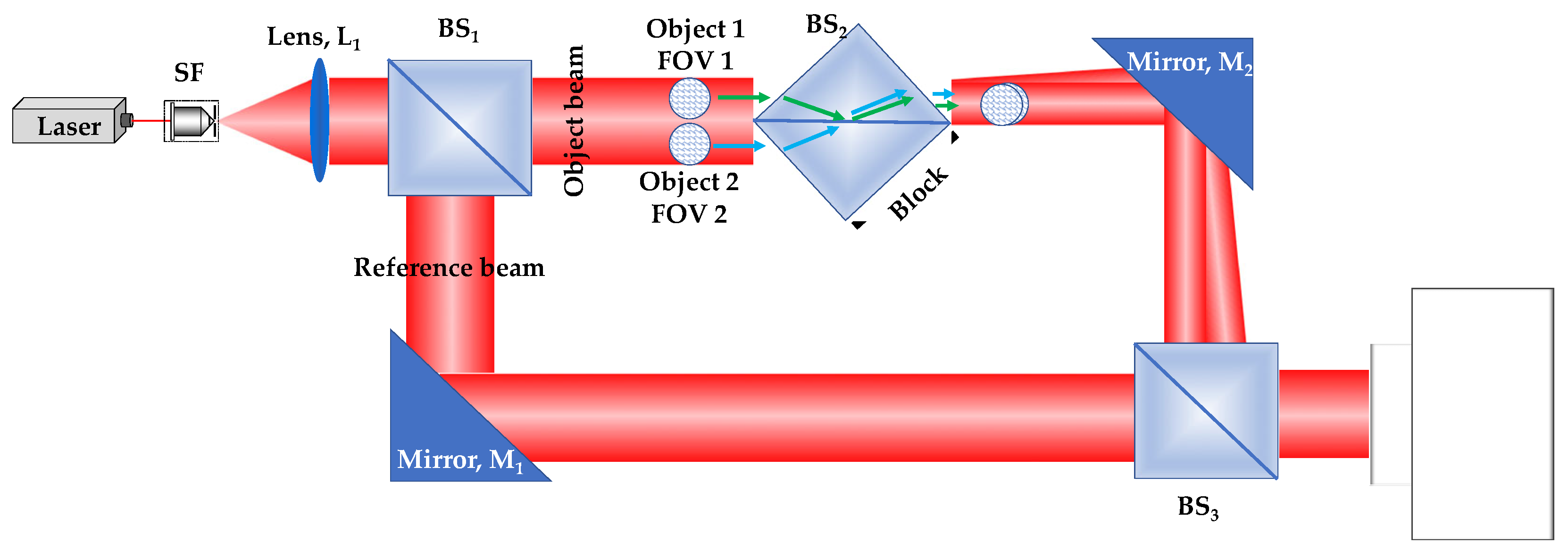

Figure 1 depicts the schematic of the single-shot double FOV digital holographic system. A He-Ne laser is used as the light source. The laser is spatially filtered by a spatial filter assembly with a microscope objective of 40

and a pinhole of 5

m. The spatially filtered laser light is collimated by a lens of focal length 100 mm and diameter of 50 mm. The collimated light beam is divided into the object and reference beams by using a cube beam splitter (BS

1). The object beam of diameter

50mm is allowed to pass through two objects (say Object 1 and Object 2) placed side-by-side. The object light transmitted through these objects is then allowed to pass through a cube beam splitter (BS

2) oriented at

45

0 with respect to the optical axis. The object diffraction wavefields corresponding to the two objects are allowed to pass through the two different prisms of BS

2. The diffracted object wavefield corresponding to Object 1 is 50% transmitted and 50% reflected through BS

2; and the same is happened for the diffracted object wavefield corresponding to Object 2. Therefore, at the exit of the BS

2, two sets of overlapped object wavefields corresponding to Object 1 and Object 2 are obtained. One set of these overlapped object wavefields is allowed to incident on the faceplate of the image sensor. This overlapped object wavefield carrying the object information of both objects is then allowed to interfere with the reference beam. This interference is accomplished by introducing another cube beam splitter (BS

3) in between BS

2 and the image sensor. Therefore, a multiplexed digital hologram is recorded by the image sensor carrying the two object information in the single recorded hologram. The image sensor used in the experiment is a Sony Pregius IMX 249 model with a pixel number of 1920 × 1200 and a pixel size of 5.86 μm.

Since in the holographic multiplexing approach, a single exposure allows for comprehensive reconstruction of the complicated wavefront. There is no overlap between the AC spectrum and conjugation spectra in the multichannel wavefronts' spatial spectra. Therefore, the sensor's redundant space-bandwidth enhances spatial bandwidth utilization (SBU). The SBU is defined by

, where

is the bandwidth of the object wavefield,

is the pixel size of the image sensor. The digital hologram took up

M × N pixels in the spatial frequency domain. Each conjugate term has a bandwidth

B0 of

M/4 in the horizontal direction and

N/4 in the vertical direction. Its area is π(

M/8)

× (

N/8). In this work, the multiplex hologram uses 4π (

MN/64)/

MN = 19.63% of the bandwidth. On the other hand, a conventional off-axis digital holography has only 16.1% SBU, which eventually leads to a limited imaging FOV with the same NA. However, a spectrum usage limit of 58.9% is possible due to the multiplexing limit of six channels in a single off-axis multiplexing hologram [

21], but at the cost of very complex system configuration.

3. Results

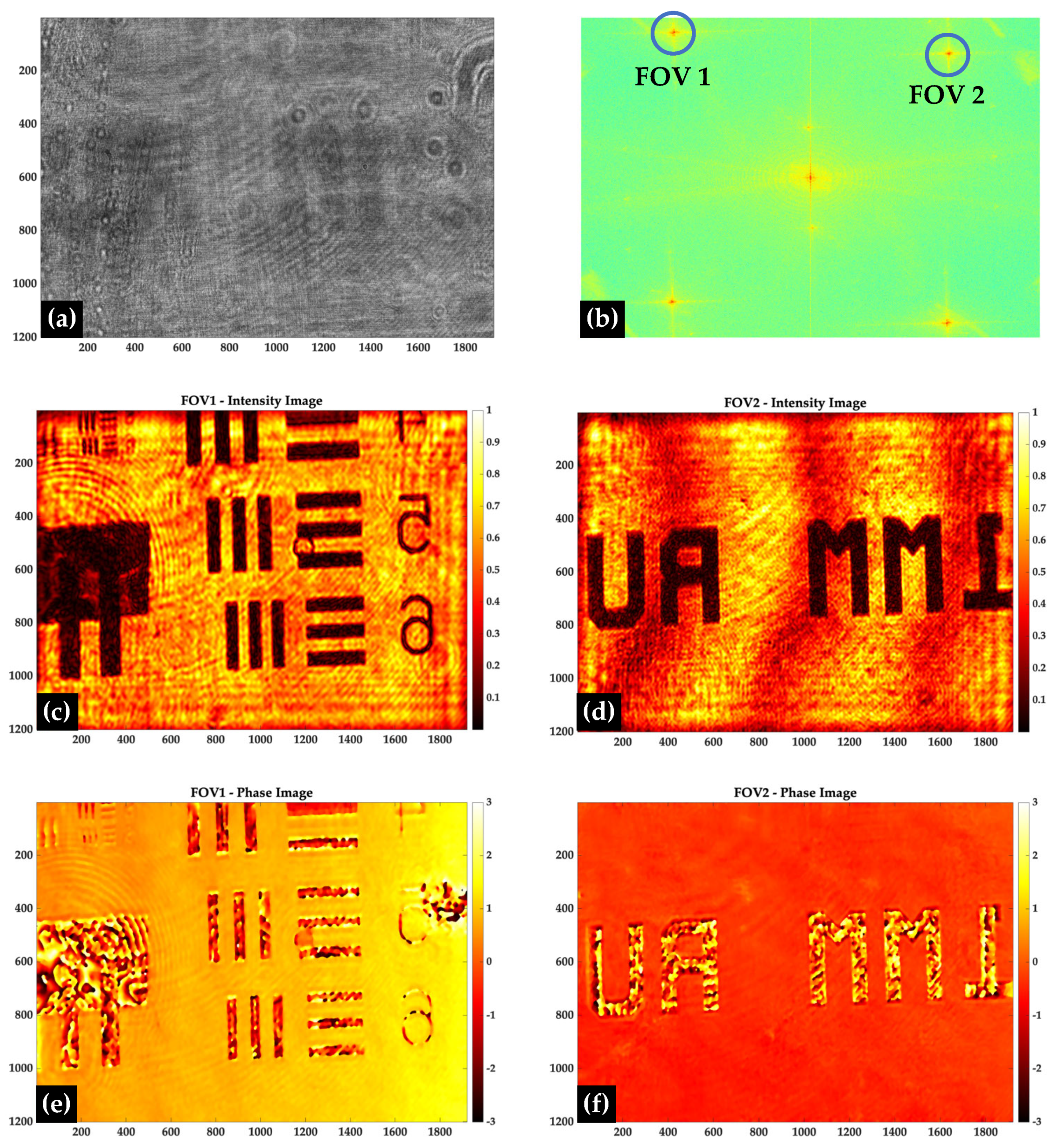

First, the experiment is performed on a United States Air Force (USAF) resolution target, in order to optimize the associated parameters of the holographic system and verify its double FOV imaging capability. The USAF resolution target (Edmund Optics, USAF 1951 1X) and Thorlabs test target R1L3S2P are placed side-by-side in the object wavefield, and a multiplexed digital hologram is recorded, which carries the object information corresponding to these two FOVs of the resolution target.

Figure 2(a) shows the recorded multiplexed digital hologram. The intensity distribution of the multiplexed digital hologram is represented by

where,

,

, represent respectively the complex amplitude of the object beams for the two FOVs and

represent the reference beam. * represents the complex conjugation.

The first three terms of Eq. (1) contribute to the auto-correlation (AC) term. The other six terms are the cross-correlation terms, as depicted in the Fourier spectrum of the multiplexed digital hologram in Fig. 2(b). The complex amplitudes (amplitude and phase) corresponding to the two FOVs are obtained by spatially filtering the C terms-

and

by following the Fresnel diffraction reconstruction method [

11]. Figures 2(c) and 2(d) show the retrieved amplitude distribution corresponding to the two FOVs, and Figs. 2(e) and (f) show their corresponding phase distributions.

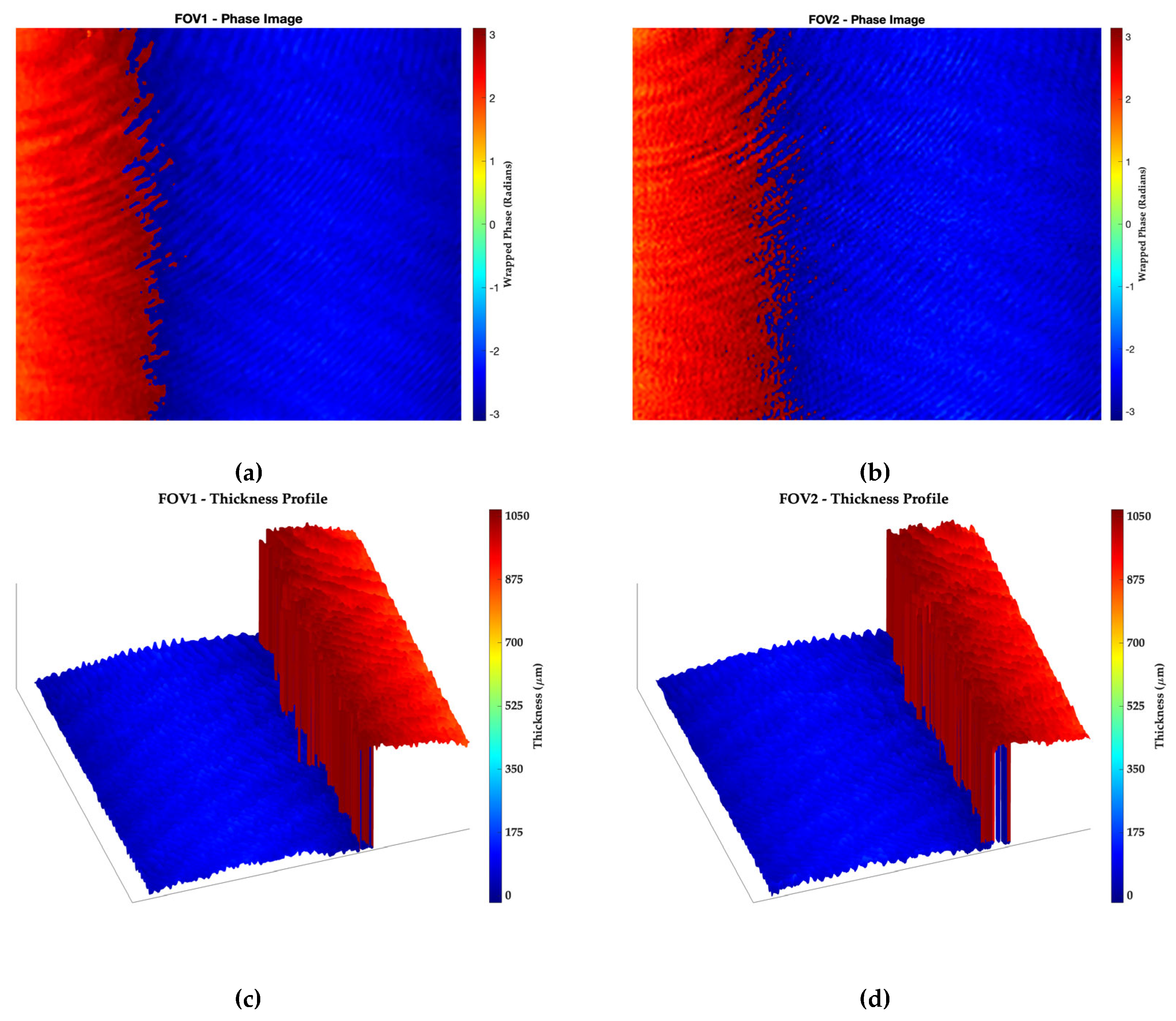

In the next experiment, a step object is created by two glass plates (of dimensions -76

26

1 mm

3) by placing one onto the another and then this step object is placed in the object beam and two multiplexed digital hologram are recorded: in the presence of the glass plate (object hologram) and in the absence of the glass plate (reference hologram). The multiplexed digital hologram carries the complex amplitude information of two objects at the same time in a single shot acquisition. The object and reference multiplexed digital holograms are processed to obtain the phase distributions (

and

). The phase distribution of the reference hologram (

) is subtracted from the phase distribution of the object hologram (

) to obtain the phase difference information (

). Further, this phase difference is related to the thickness,

by the following expression,

where,

is the wavelength of the light source used and

is the refractive index difference between the object and the surrounding medium.

The obtained phase difference distributions corresponding to the two FOVs are shown in

Figure 3(a) and (b), respectively. The measured thickness profiles from the obtained phase distributions by using Eq. (2) corresponding to the two FOVs are shown in Figs. 3(c) and (d).

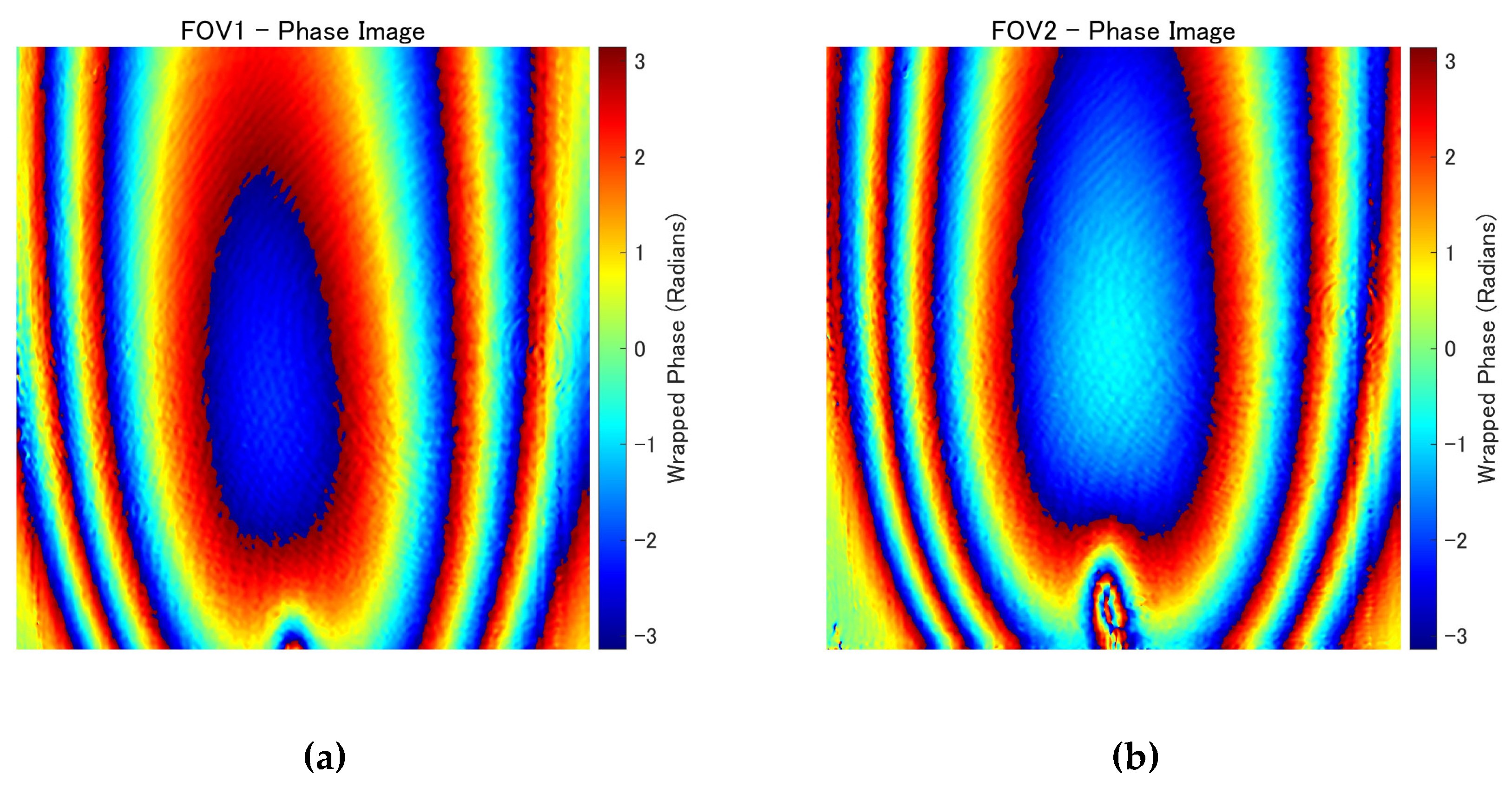

Further, an experiment is performed for the dynamic phase visualization of two candle flames, where two multiplexed digital holograms are recorded: one in the presence of the candle flames and another without the candle flames. These two multiplexed holograms are processed and phase difference distributions corresponding to the two FOVs are obtained. The phase difference distributions for the two FOVs are depicted in

Figure 4(a) and (b), respectively. The obtained phase distributions corresponding to the two FOVs can further be used for the measurements of refractive index and temperature, similarly to our previous works [

49,

50,

51] by using the following mathematical expressions for refractive index and temperature connected to the obtained phase distribution,

where,

is the refractive index of air,

.

4. Conclusions

The continual evolution of optical metrology has led to remarkable strides in high-bandwidth digital holography, particularly for the analysis of transparent objects where traditional measurement techniques often fall short. This article has explored the limitations of conventional digital holography, especially in terms of the field of view. In this work, the double FOV is achieved by employing a cube beam splitter in the object beam with the orientation of 450 with respect to the optical axis, which strategically folds the two distinct FOVs onto the active area of the image sensor. Therefore, this configuration enables to record two different areas of the object in a single-shot, hence extends the FOV by double that of a digital holographic system. The proof of the concept is experimentally demonstrated on different objects. Further, some optical metrological applications are experimentally demonstrated by performing the experiments on measuring the glass plate thickness and phase imaging of candle flame with double FOV. Therefore, this digital holographic system, leveraged with single-shot double FOV capability, can effectively be used for the analysis of scientific and industrial measurement applications.

Through this advancement—developing a single-shot double FOV configuration, digital holography has transitioned from a laboratory tool to a versatile, high-precision imaging modality. This method has enabled real-time, non-invasive optical measurement applications, including surface profiling, temperature mapping, and refractive index profiling in transparent media with improved object information.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K.; methodology, M.K. and L.P.; software, M.K., L.P., and R.J.; validation, M.K., L.P., R.J., R.K., Y.A., and O.M.; formal analysis, M.K.; investigation, M.K., L.P., R.J., R.K., Y.A., and O.M.; data curation, M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K.; writing—review and editing, M.K., L.P., R.J., R.K., Y.A., and O.M.; visualization, M.K., L.P., R.J., R.K., Y.A., and O.M.; supervision, M.K. and O.M.; project administration, M.K., Y.A., and O.M.; funding acquisition, M.K., Y.A., and O.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by ANRF, grant number RJF/2023/000048.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data underlying the results presented in this paper are not publicly available at this time but may be obtained from the authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Santiago, J.G.; Wereley, S.T.; Meinhart, C.D.; Beebe, D.J.; Adrian, R.J. A Particle Image Velocimetry System for Microfluidics. Experiments in Fluids 1998, 25, 316–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Docquier, N.; Candel, S. Combustion Control and Sensors: A Review. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 2002, 28, 107–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.V.; Hu, S. Photoacoustic Tomography: In Vivo Imaging from Organelles to Organs. Science 2012, 335, 1458–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Wang, Y.; Tan, D.Q. A Review of Surface Roughness Impact on Dielectric Film Properties. IET Nanodielectrics 2022, 5, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Choi, S.; Sasaki, O.; Luo, S.; Suzuki, T.; Liu, Y.; Pu, J. Large Thickness Measurement of Glass Plates with a Spectrally Resolved Interferometer Using Variable Signal Positions. OSA Continuum 2021, 4, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Y.P.; Chatterjee, S. Thickness Measurement of Transparent Glass Plates Using a Lateral Shearing Cyclic Path Optical Configuration Setup and Polarization Phase Shifting Interferometry. Appl. Opt. 2010, 49, 6552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Kim, Y.; Shin, S.-C.; Hibino, K.; Sugita, N. Interferometric Thickness Measurement of Glass Plate by Phase-Shifting Analysis Using Wavelength Scanning with Elimination of Bias Phase Error. Opt Rev 2021, 28, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Omega Engineering. (1995). Temperature Measurement Handbook. Omega Press.

- Maldague, X.P. Theory and Practice of Infrared Technology for Nondestructive Testing; Wiley series in microwave and optical engineering; Wiley: New York Weinheim, 2001; ISBN 978-0-471-18190-3. [Google Scholar]

- P. Hariharan Optical Interferometry; Elsevier, 2003; ISBN 978-0-12-311630-7.

- Schnars, U.; Jüptner, W. Direct Recording of Holograms by a CCD Target and Numerical Reconstruction. Appl. Opt. 1994, 33, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, J.T.; Kostuk, R.K.; Gil, A.F.; Wang, Y.; Lu, W.; Zhong, H.; Tomita, Y.; Neipp, C.; Francés, J.; Gallego, S.; et al. Roadmap on Holography. J. Opt. 2020, 22, 123002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pensia, L.; Dwivedi, G.; Kumar, R. Non-Destructive Inspection and Quantification of Defects in Plywood Using a Portable Digital Holographic Camera. Wood Sci Technol 2021, 55, 873–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pensia, L.; Dwivedi, G.; Singh, O.; Kumar, R. Noise Free Defect Detection in Ceramic Tableware Using a Portable Digital Holographic Camera. Appl. Opt. 2022, 61, B181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreis, T.M. Frequency Analysis of Digital Holography. Opt. Eng 2002, 41, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stępień, P.; Korbuszewski, D.; Kujawińska, M. Digital Holographic Microscopy with Extended Field of View Using Tool for Generic Image Stitching. ETRI Journal 2019, 41, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, J.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, P.; Fan, Q.; Sun, W. High Resolution Digital Holographic Microscopy with a Wide Field of View Based on a Synthetic Aperture Technique and Use of Linear CCD Scanning. Appl. Opt. 2008, 47, 5654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, B.; Liu, X.; Ge, X.-L.; Guo, C.-S. Fast Reconstruction of Off-Axis Digital Holograms Based on Digital Spatial Multiplexing. Opt. Express 2014, 22, 23066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girshovitz, P.; Shaked, N.T. Doubling the Field of View in Off-Axis Low-Coherence Interferometric Imaging. Light Sci Appl 2014, 3, e151–e151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaked, N.T.; Micó, V.; Trusiak, M.; Kuś, A.; Mirsky, S.K. Off-Axis Digital Holographic Multiplexing for Rapid Wavefront Acquisition and Processing. Adv. Opt. Photon. 2020, 12, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, M.; Dardikman, G.; Mirsky, S.K.; Turko, N.A.; Shaked, N.T. Six-Pack off-Axis Holography. Opt. Lett. 2017, 42, 4611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tayebi, B.; Sharif, F.; Jafarfard, M.R.; Kim, D.Y. Double-Field-of-View, Quasi-Common-Path Interferometer Using Fourier Domain Multiplexing. Opt. Express 2015, 23, 26825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayebi, B.; Kim, W.; Yoon, B.-J.; Han, J.-H. Real-Time Triple Field of View Interferometry for Scan-Free Monitoring of Multiple Objects. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2018, 23, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Cao, L.; Jin, G.; Brady, D. Full Field-of-View Digital Lens-Free Holography for Weak-Scattering Objects Based on Grating Modulation. Appl. Opt. 2018, 57, A164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.; Jang, C.; Kim, D.; Lee, B. Single Grating Reflective Digital Holography With Double Field of View. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 2019, 15, 6155–6161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Pensia, L.; Kumar, R. Single-Shot off-Axis Digital Holographic System with Extended Field-of-View by Using Multiplexing Method. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 16462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pensia, L.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, R. Dual Field-of-View Off-Axis Spatially Multiplexed Digital Holography Using Fresnel’s Bi-Mirror. Sensors 2024, 24, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Yoneda, N.; Pensia, L.; Muniraj, I.; Anand, V.; Kumar, R.; Murata, T.; Awatsuji, Y.; Matoba, O. Light Origami Multi-Beam Interference Digital Holographic Microscope for Live Cell Imaging. Optics & Laser Technology 2024, 176, 110961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Murata, T.; Matoba, O. Double Field-of-View Single-Shot Common-Path off-Axis Reflective Digital Holographic Microscope. Applied Physics Letters 2023, 123, 223702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pensia, L.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, R. A Compact Digital Holographic System Based on a Multifunctional Holographic Optical Element with Improved Resolution and Field of View. Optics and Lasers in Engineering 2023, 169, 107744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Matoba, O. 2D Full-Field Displacement and Vibration Measurements of Specularly Reflecting Surfaces by Two-Beam Common-Path Digital Holography. Opt. Lett. 2021, 46, 5966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Pensia, L.; Kumar, R.; Matoba, O. Lensless Fourier Transform Multiplexed Digital Holography. Opt. Lett. 2025, 50, 1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Pensia, L.; Kumar, R.; Matoba, O. Vibration Measurement of 3-D Objects With Single-Shot Double Field-of-View High-Speed Digital Holography. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Xie, H.; Yang, L. Learned Large Field-of-View Imager with a Simple Spherical Optical Module. Optics Communications 2023, 526, 128918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Cao, L. High Bandwidth-Utilization Digital Holographic Multiplexing: An Approach Using Kramers–Kronig Relations. Advanced Photonics Research 2022, 3, 2100273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundt, J.; Kreis, T.M. Digital Holographic Recording and Reconstruction of Large Scale Objects for Metrology and Display. Opt. Eng 2010, 49, 125801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Dwivedi, G.; Singh, O. Portable Digital Holographic Camera Featuring Enhanced Field of View and Reduced Exposure Time. Optics and Lasers in Engineering 2021, 137, 106359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settles, G.S.; Hargather, M.J. A Review of Recent Developments in Schlieren and Shadowgraph Techniques. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2017, 28, 042001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, D.W.; Vest, C.M. Measurement of Three-Dimensional Temperature Fields above Heated Surfaces by Holographic Interferometry. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 1974, 17, 1443–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, P.V.; Springer, G.S.; Vest, C.M. Heterodyne Holographic Interferometry: Concentration and Temperature Measurements in Gas Mixtures. Appl. Opt. 1982, 21, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuss, D.L. Temperature Measurements in a Radially Symmetric Flame Using Holographic Interferometry. Combustion and Flame 1983, 49, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keren, E.; Bar-Ziv, E.; Glatt, I.; Kafri, O. Measurements of Temperature Distribution of Flames by Moire Deflectometry. Appl. Opt. 1981, 20, 4263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, P.V.; Hofeldt, D.L. Temperature Measurement in Gases Using Speckle Photography. Appl. Opt. 1984, 23, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, A.; Guj, G.; Giammartini, S. Measurement of Axisymmetric Temperature Fields Using Reference Beam and Shearing Interferometry for Application to Flames. Experiments in Fluids 2000, 29, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Shakher, C. Measurement of Temperature and Temperature Distribution in Gaseous Flames by Digital Speckle Pattern Shearing Interferometry Using Holographic Optical Element. Optics and Lasers in Engineering 2015, 73, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Agarwal, S.; Kumar, V.; Khan, G.S.; Shakher, C. Experimental Investigation on Butane Diffusion Flames under the Influence of Magnetic Field by Using Digital Speckle Pattern Interferometry. Appl. Opt. 2015, 54, 2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doleček, R.; Psota, P.; Lédl, V.; Vít, T.; Václavík, J.; Kopecký, V. General Temperature Field Measurement by Digital Holography. Appl. Opt. 2013, 52, A319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Mendez, C.; Anaya, T.S.; Araiza-Esquivel, M.; Balderas-Navarro, R.E.; Aranda-Espinoza, S.; López-Martínez, A.; Olvera-Olvera, C. Real-Time Measurement of the Average Temperature Profiles in Liquid Cooling Using Digital Holographic Interferometry. Opt. Eng 2016, 55, 121730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Matoba, O.; Quan, X.; Rajput, S.K.; Awatsuji, Y.; Tamada, Y. Single-Shot Common-Path off-Axis Digital Holography: Applications in Bioimaging and Optical Metrology [Invited]. Appl. Opt. 2021, 60, A195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumon, Y.; Hashimoto, S.; Inoue, T.; Nishio, K.; Kumar, M.; Matoba, O.; Xia, P.; Rajput, S.K.; Awatsuji, Y. Three-Dimensional Video Imaging of Dynamic Temperature Field of Transparent Objects Recorded by a Single-View Parallel Phase-Shifting Digital Holography. Optics & Laser Technology 2023, 167, 109808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, P.; Ri, S.; Inoue, T.; Awatsuji, Y.; Matoba, O. Three-Dimensional Dynamic Measurement of Unstable Temperature Fields by Multi-View Single-Shot Phase-Shifting Digital Holography. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 37760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).