Submitted:

21 May 2025

Posted:

26 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Highlights What are the main findings?

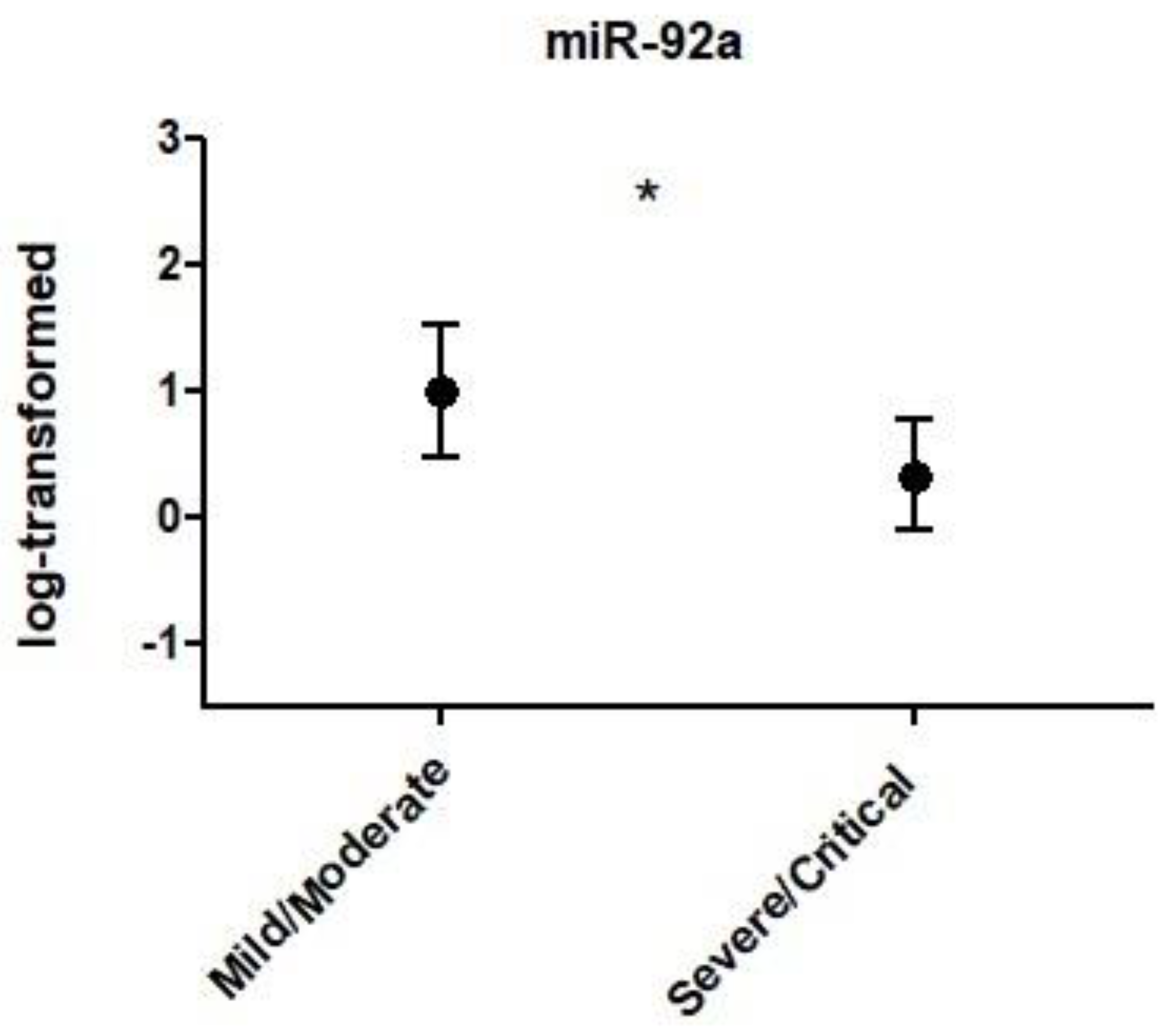

- Individuals with severity of COVID-19 is associated with differences in the expression of miR-92a.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- It is important to study the role of circulating miRNAs as agents or markers of severe immune/thrombotic dysfunction and clinical response to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Introduction

Methods

Experimental Design and Sample

PBMCs Extraction

Extraction of Low Molecular Weight RNA

MicroRNA Selection

Relative Quantification of MiRNAs by qPCR Analysis

Statistical Analyses

Results

Discussion

Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- da Silva, S.J.R.; do Nascimento, J.C.F.; Germano Mendes, R.P.; Guarines, K.M.; Targino Alves da Silva, C.; da Silva, P.G.; et al. Two Years into the COVID-19 Pandemic: Lessons Learned. ACS Infect Dis. 2022, 8, 1758–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, T.; Kumar, S.; Mishra, G.; Saxena, S.K. Tracking the COVID-19 vaccines: The global landscape. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2023, 19, 2191577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Amahong, K.; Sun, X.; Lian, X.; Liu, J.; Sun, H.; et al. The miRNA: a small but powerful RNA for COVID-19. Brief Bioinform. 2021, 22, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.L.; Wang, X.G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.F.; Yuan, S.; Kok, K.H.; To, K.K.; Chu, H.; Yang, J.; et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020, 395, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirzaei, R.; Goodarzi, P.; Asadi, M.; Soltani, A.; Aljanabi, H.A.A.; Jeda, A.S.; et al. Bacterial co-infections with SARS-CoV-2. IUBMB Life. 2020, 72, 2097–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canatan, D.; De Sanctis, V. The impact of MicroRNAs (miRNAs) on the genotype of coronaviruses. Acta Biomed. 2020, 91, 195–198. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.; Tiwari, S.; Deb, M.K.; Marty, J.L. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2): a global pandemic and treatment strategies. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020, 56, 106054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini Rad Sm, A.; McLellan, A.D. Implications of SARS-CoV-2 Mutations for Genomic RNA Structure and Host microRNA Targeting. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliminejad, K.; Khorram Khorshid, H.R.; Soleymani Fard, S.; Ghaffari, S.H. An overview of microRNAs: Biology, functions, therapeutics, and analysis methods. J Cell Physiol. 2019, 234, 5451–5465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, k.; Weng, H.; Naito, Y.; Sasaoka, T.; Takahashi, A.; Fukushima, Y.; et al. Classification of various muscular tissues using miRNA profiling. Biomedical Research. 2013, 34, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernier, A.; Sagan, S.M. The Diverse Roles of microRNAs at the Host(-)Virus Interface. Viruses. 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardi, E.; Lopez, P.; Pfeffer, S. On the Importance of Host MicroRNAs During Viral Infection. Front Genet. 2018, 9, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbu, M.G.; Condrat, C.E.; Thompson, D.C.; Bugnar, O.L.; Cretoiu, D.; Toader, O.D.; et al. MicroRNA Involvement in Signaling Pathways During Viral Infection. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020, 8, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarinejad-Farsangi, S.; Jazi, M.M.; Rostamzadeh, F.; Hadizadeh, M. High affinity of host human microRNAs to SARS-CoV-2 genome: An in silico analysis. Noncoding RNA Res. 2020, 5, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi-Dehcheshmeh, M.; Moghbeli, S.M.; Rahimirad, S.; Alanazi, I.O.; Shehri, Z.S.A.; Ebrahimie, E. A Transcription Regulatory Sequence in the 5' Untranslated Region of SARS-CoV-2 Is Vital for Virus Replication with an Altered Evolutionary Pattern against Human Inhibitory MicroRNAs. Cells. 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurizky, P.; Nobrega, O.T.; Soares, A.; Aires, R.B.; Albuquerque, C.P.; Nicola, A.M.; et al. Molecular and Cellular Biomarkers of COVID-19 Prognosis: Protocol for the Prospective Cohort TARGET Study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2021, 10, e24211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, A.; Duyvejonck, H.; Van Belleghem, J.D.; Gryp, T.; Van Simaey, L.; Vermeulen, S.; et al. Comparison of procedures for RNA-extraction from peripheral blood mononuclear cells. PLoS One. 2020, 15, e0229423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuss, I.J.; Kanof, M.E.; Smith, P.D.; Zola, H. Isolation of whole mononuclear cells from peripheral blood and cord blood. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2009, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, V.C.; Morais, G.S., Jr.; Henriques, A.D.; Machado-Silva, W.; Perez, D.I.V.; Brito, C.J.; et al. Whole-Blood Levels of MicroRNA-9 Are Decreased in Patients With Late-Onset Alzheimer Disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2020, 35, 1533317520911573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, J.T.; Salmena, L. Prediction and Analysis of SARS-CoV-2-Targeting MicroRNA in Human Lung Epithelium. Genes (Basel). 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Gonzalo-Calvo, D.; Benitez, I.D.; Pinilla, L.; Carratala, A.; Moncusi-Moix, A.; Gort-Paniello, C.; et al. Circulating microRNA profiles predict the severity of COVID-19 in hospitalized patients. Transl Res. 2021, 236, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, A.; Seeliger, B.; Derda, A.A.; Xiao, K.; Gietz, A.; Scherf, K.; et al. Circulating cardiovascular microRNAs in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021, 23, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, S.; Made, A.; Gaetano, C.; Devaux, Y.; Emanueli, C.; Martelli, F. Noncoding RNAs implication in cardiovascular diseases in the COVID-19 era. J Transl Med. 2020, 18, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.K.; Zhang, Q.; Gao, L.; Li, N.; Chen, X.X.; Feng, W.H. Increasing expression of microRNA 181 inhibits porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus replication and has implications for controlling virus infection. J Virol. 2013, 87, 1159–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henzinger, H.; Barth, D.A.; Klec, C.; Pichler, M. Non-Coding RNAs and SARS-Related Coronaviruses. Viruses. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Du, J.; Yu, X.; Xu, J.; Huang, F.; Li, X.; et al. miRNA-200c-3p is crucial in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Cell Discov. 2017, 3, 17021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaiah, M.J. mTOR inhibition and p53 activation, microRNAs: The possible therapy against pandemic COVID-19. Gene Rep. 2020, 20, 100765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbatinelli, J.; Giuliani, A.; Matacchione, G.; Latini, S.; Laprovitera, N.; Pomponio, G.; et al. Decreased serum levels of the inflammaging marker miR-146a are associated with clinical non-response to tocilizumab in COVID-19 patients. Mech Ageing Dev. 2021, 193, 111413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Gao, Y.; Li, Z.; Miao, Y.; Huang, Z.; Liu, X.; et al. The noncoding and coding transcriptional landscape of the peripheral immune response in patients with COVID-19. Clin Transl Med. 2020, 10, e200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fata, U.H.; Febriana, L. Oxygen Saturation (SPO2) in Covid-19 Patients. Jurnal Ners dan Kebidanan (Journal of Ners and Midwifery). 2021, 8, 290–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Jiang, H.; Li, X.; Chen, X.; Huang, Y. MiR-92a regulates brown adipocytes differentiation, mitochondrial oxidative respiration, and heat generation by targeting SMAD7. J Cell Biochem. 2020, 121, 3825–3836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannella, A.; Riccetti, S.; Sinigaglia, A.; Piubelli, C.; Razzaboni, E.; Di Battista, P.; et al. Circulating microRNA signatures associated with disease severity and outcome in COVID-19 patients. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 968991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Liang, L.; Zhang, R.; Wei, Y.; Su, L.; Tejera, P.; et al. Whole blood microRNA markers are associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2017, 5, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loyer, X.; Potteaux, S.; Vion, A.C.; Guerin, C.L.; Boulkroun, S.; Rautou, P.E.; et al. Inhibition of microRNA-92a prevents endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis in mice. Circ Res. 2014, 114, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Chevillet, J.R.; Liu, G.; Kim, T.K.; Wang, K. The effects of microRNA on the absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion of drugs. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2015, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molitoris, J.K.; McColl, K.S.; Distelhorst, C.W. Glucocorticoid-mediated repression of the oncogenic microRNA cluster miR-17~92 contributes to the induction of Bim and initiation of apoptosis. Mol Endocrinol. 2011, 25, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tie, K.; Zhao, Z.; Wu, Z.; Qin, J.; Zhang, J.; Pei, L.; et al. Low miR-92a-3p in oocytes mediates the multigenerational and transgenerational inheritance of poor cartilage quality in rat induced by prenatal dexamethasone exposure. Biochem Pharmacol. 2022, 203, 115196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.Y.; Kweon, O.J.; Cha, M.J.; Baek, M.S.; Choi, S.H. Dexamethasone may improve severe COVID-19 via ameliorating endothelial injury and inflammation: A preliminary pilot study. PLoS One. 2021, 16, e0254167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Mild/Moderate (n = 9) |

Severe/Critical (n = 24) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | 39.1 ± 17.8 | 51.8 ± 14.7 | 0.044 |

| DS (Days)* | 20.7 ± 5.7 | 17.4 ± 6.5 | 0.205 |

| AS** | 3.0 (3.0 - 3.7) | 4.5 (3.6 - 5.7) | 0.024 |

| SpO2 (%)* | 95.0 ± 2.5 | 88.5 ± 4.7 | 0.001 |

| AD (qty)** | 3.0 (1.0 - 4.0) | 5.0 (3.0 - 5.0) | 0.045 |

| MV (%)† | 0.0 | 16.7 | 0.191 |

| Current SAH (%)† | 11.1 | 45.8 | 0.065 |

| Current T2DM (%)† | 0.0 | 6.5 | 0.031 |

| Current Asthma (%)† | 0.0 | 4.2 | 0.534 |

| Hystory of Cancer (%)† | 0.0 | 4.2 | 0.534 |

| Current Depression (%)† | 0.0 | 4.2 | 0.534 |

| Deaths (%)† | 0.0 | 12.5 | 0.266 |

| miR-1-2 | miR-10a | miR-92a | miR-100 | miR-145 | miR-146a | miR-155 | miR-181a | miR-200a | miR-221 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | -.049; .868 | .179; .579 | .084; .648 | -.453; .120 | -.368; .101 | -.312; .082 | .101; .576 | -.356; .088 | -.441; .174 | .038; .834 |

| T2DM | -.235; .418 | -.169; ,581 | -.102; .580 | .165; .590 | .154; .505 | .200; .274 | .129; .476 | .147; .493 | .150; .660 | .079; .664 |

| Sex§ | .072; .808 | .042; .891 | .091; .908 | .082; .789 | .008; .972 | -.075; .684 | .034; .852 | -.057; .790 | .231; .493 | -.061; .737 |

| DS§ | -.388; .239 | -.297; .404 | -.179; .363 | .243; .499 | .262; .310 | .252; .196 | .007; .971 | .265; .259 | .224; .594 | .025; .899 |

| AS§ | -314; .296 | -.169; .599 | -.072; .699 | -.360; .250 | -.217; .357 | -.127; .495 | .060; .746 | -.168; .443 | -.362; .303 | .151; .411 |

| SpO2§ | .174; .570 | -.543; .068 | -.377; .048* | .220; .493 | .102; .668 | .098; .619 | -.080; .679 | .089; .687 | .290; .416 | .002; .990 |

| MV§ | -.513; .073 | -.139; .666 | .135; .471 | -.251; .432 | .255; .278 | -.097; .604 | .225; .215 | .097; 659 | -.393; .261 | .092; .616 |

| AD§ | .239; .455 | .357; .281 | .181; .348 | .121; .723 | .082; .739 | .031; .873 | .292; .118 | .047; .836 | .197; .612 | .055; .774 |

| SAH§ | .251; .387 | -.042; .891 | .042; 820 | .041; .894 | -.056; .811 | .231; .204 | .218; .222 | -.036; .866 | -.120; .726 | .225; .208 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).