Submitted:

22 May 2025

Posted:

23 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

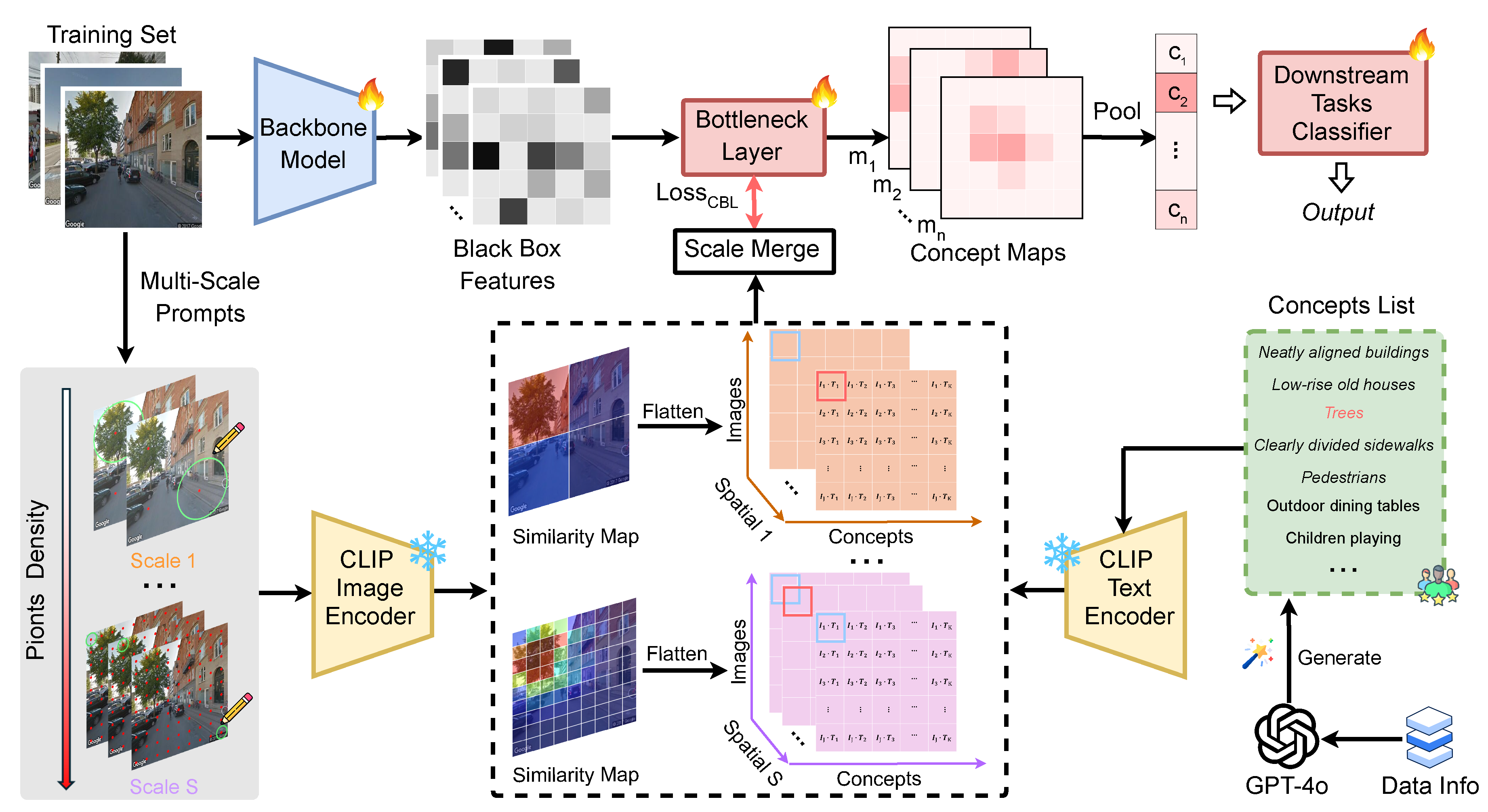

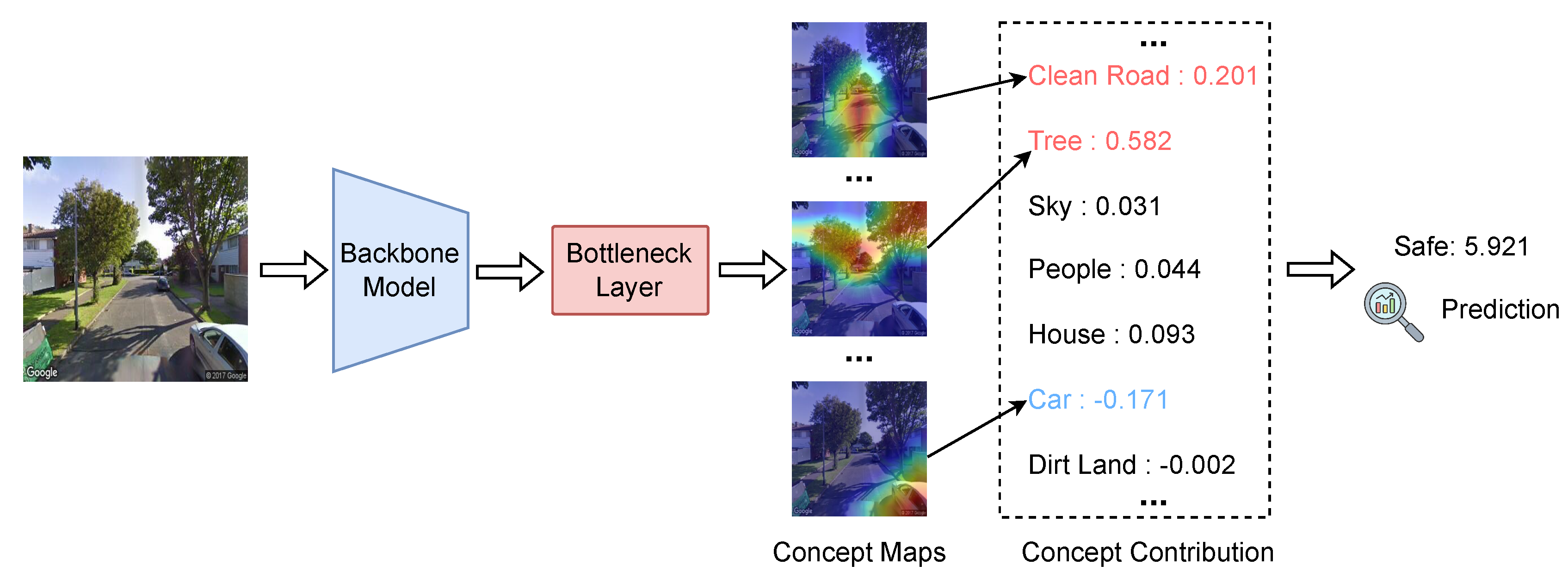

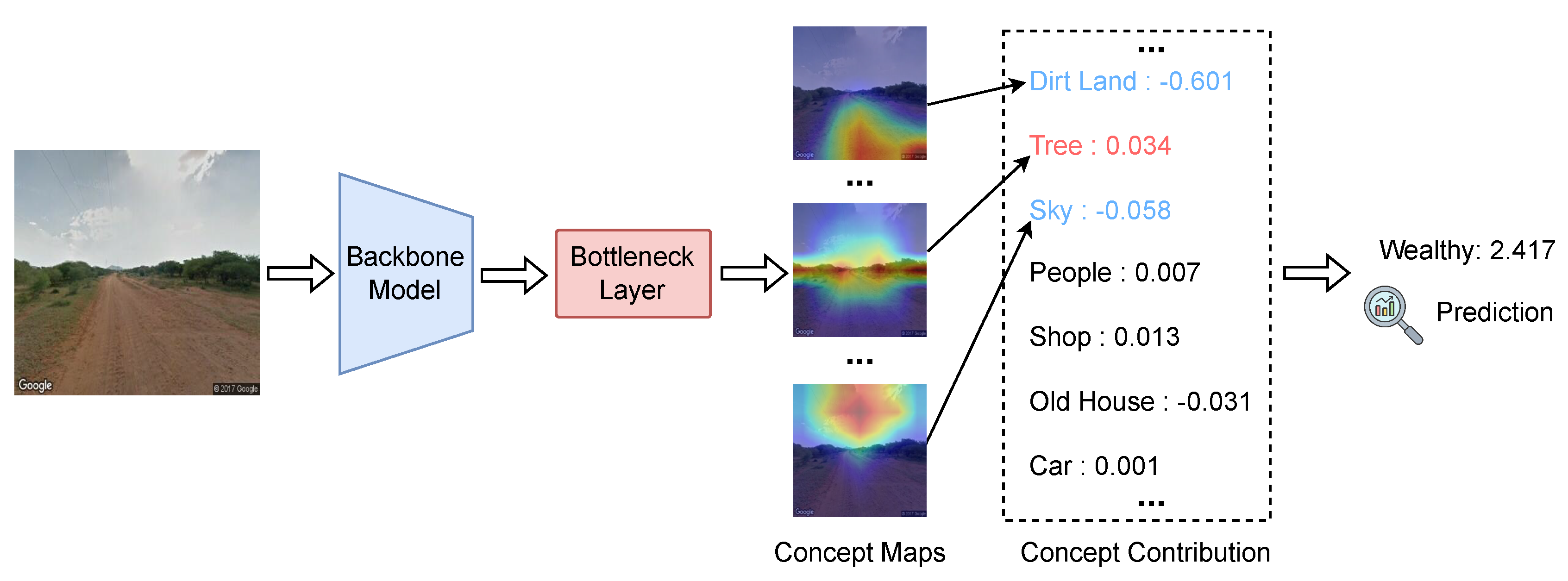

- A interpretable urban perception pipeline that explicitly models perceptual reasoning through human-understandable visual concepts is proposed. Our approach introduces a concept bottleneck layer aligned with CLIP-derived similarity maps, enabling transparent and controllable perception prediction.

- We design a class-free concept discovery mechanism using GPT-4o, generating task-specific visual concepts without relying on predefined categories. This allows the model to flexibly adapt to perception tasks with subjective or continuous labels, such as safety or walkability.

- A multi-scale prompting strategy to spatially probe and localize perceptual concepts in street view images is designed for better concept extraction, achieving both accurate and interpretable predictions across multiple datasets.

2. Related work

2.1. Visual Foundation Models

2.2. Quantifying Urban Perception via Foundation Models

2.3. Concept-Based Explanation

3. Method

3.1. Concept Generation

- Overly long or ambiguous descriptions (e.g., “a sense of openness and connectedness”),

- Semantically overlapping entries (e.g., “car” and “vehicle”),

- Items that are not visually grounded in the dataset (e.g., abstract concepts like “justice”).

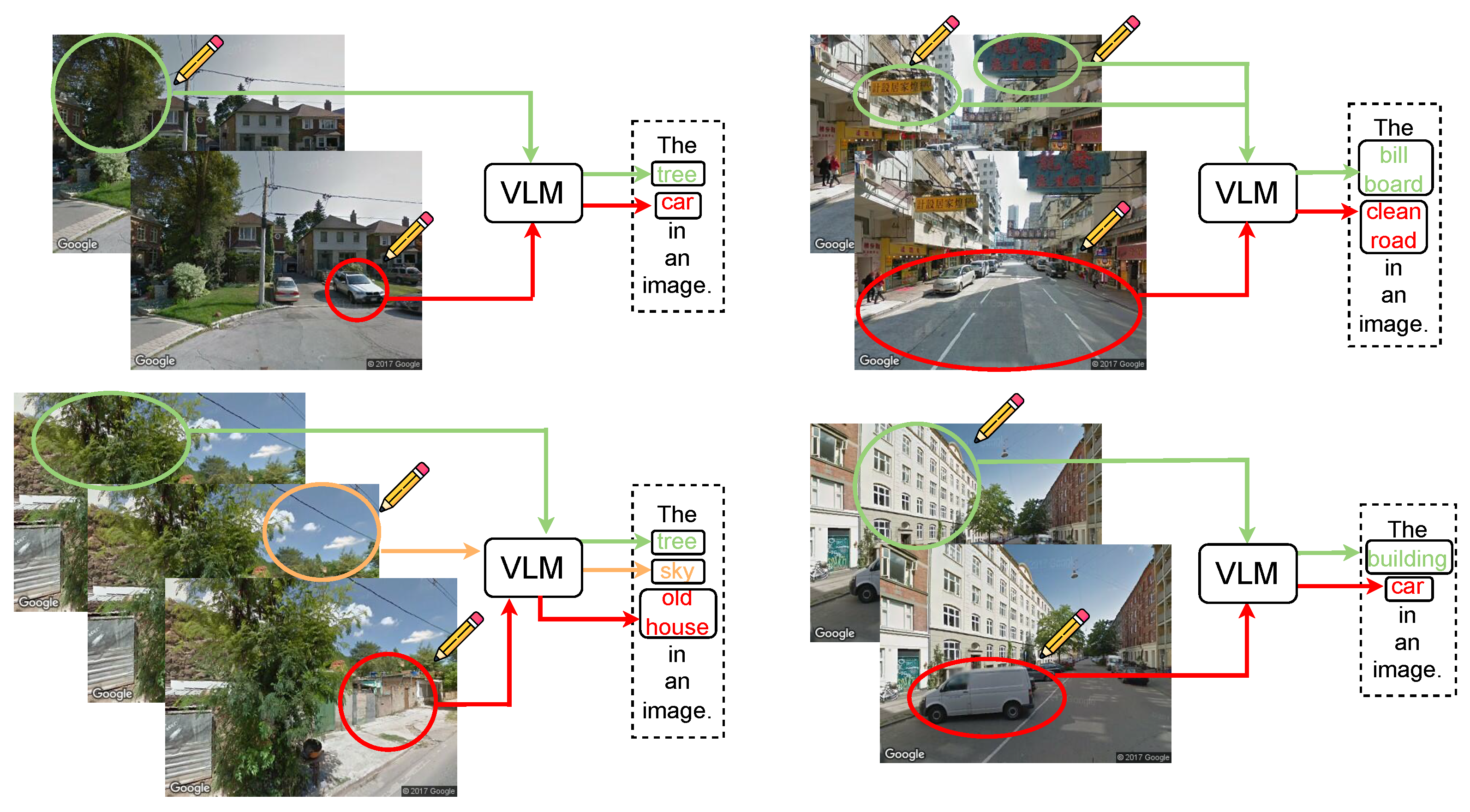

3.2. Fine-Grained Image-Concept Similarities

3.3. Bottleneck Layer for Concept Alignment

3.4. Downstream Prediction Using Concepts

3.5. Evaluation Metrics

4. Experiment

4.1. Datasets

4.2. Implementation Details

4.3. Comparison to Existing Methods

| Models | Walkability | Feasibility | Accessibility | Safety | Comfort | Pleasurability | Overall |

| ResNet50 [63] | .8652 | .9084 | .7561 | .7984 | .8950 | .8549 | .8497 |

| ViT-Base [64] | .8915 | .9321 | .7894 | .8361 | .9173 | .8805 | .8728 |

| ProtoPNet [17] | .8601 | .9001 | .7550 | .8002 | .8925 | .8508 | .8440 |

| SENN [65] | .8530 | .9019 | .7423 | .7820 | .8861 | .8427 | .8346 |

| P-CBM [66] | .8794 | .9206 | .7722 | .8189 | .9080 | .8655 | .8608 |

| BotCL [16] | .8743 | .9198 | .7705 | .8127 | .9042 | .8630 | .8574 |

| LF-CBM [67] | .8880 | .9297 | .7846 | .8295 | .9150 | .8780 | .8647 |

| UP-CBM RN50 (Ours) | .8825 | .9260 | .7790 | .8242 | .9192 | .8701 | .8655 |

| UP-CBM ViT-B (Ours) | .9021 | .9405 | .7980 | .8452 | .9253 | .8899 | .8835 |

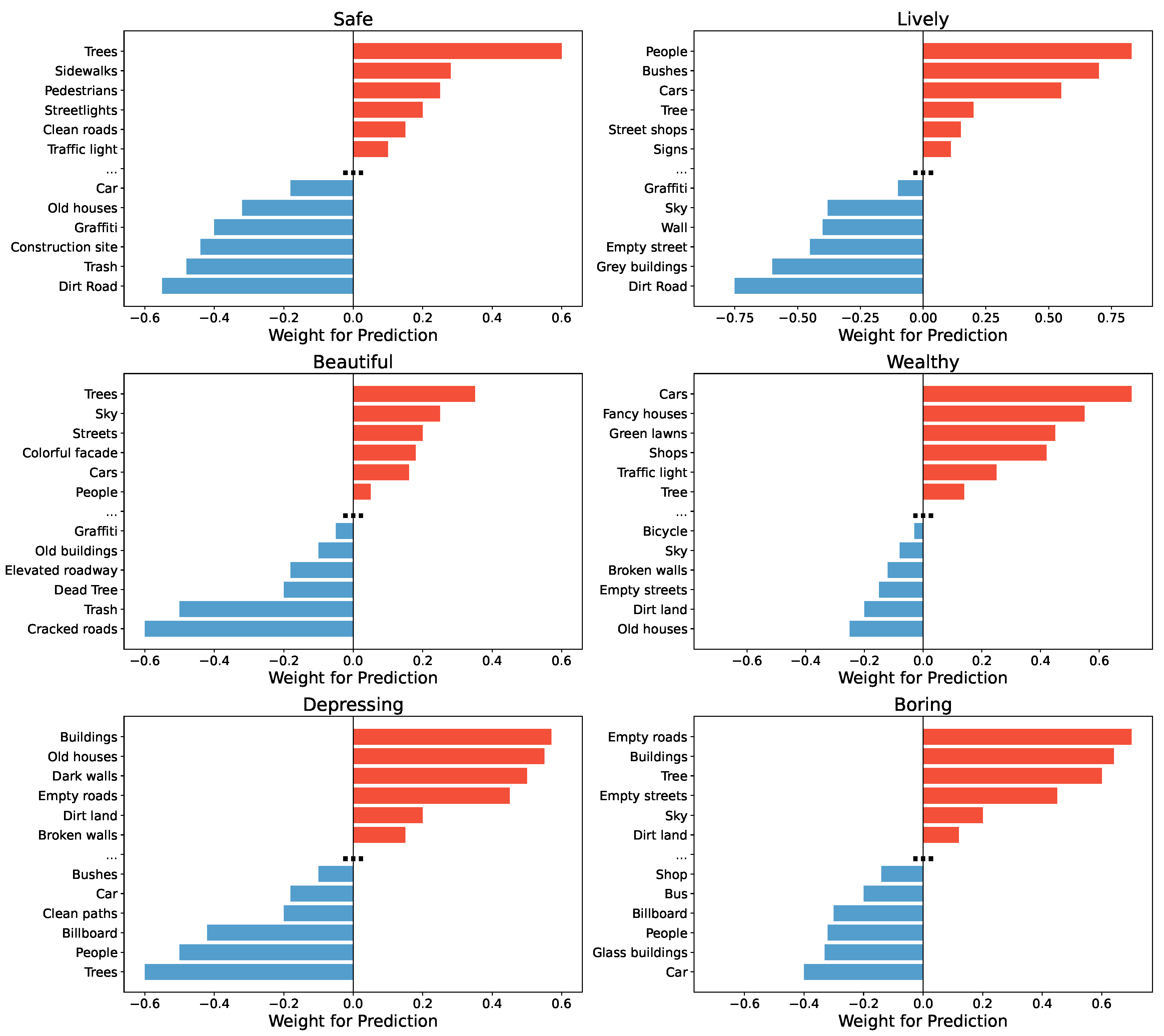

4.4. Concept Analysis

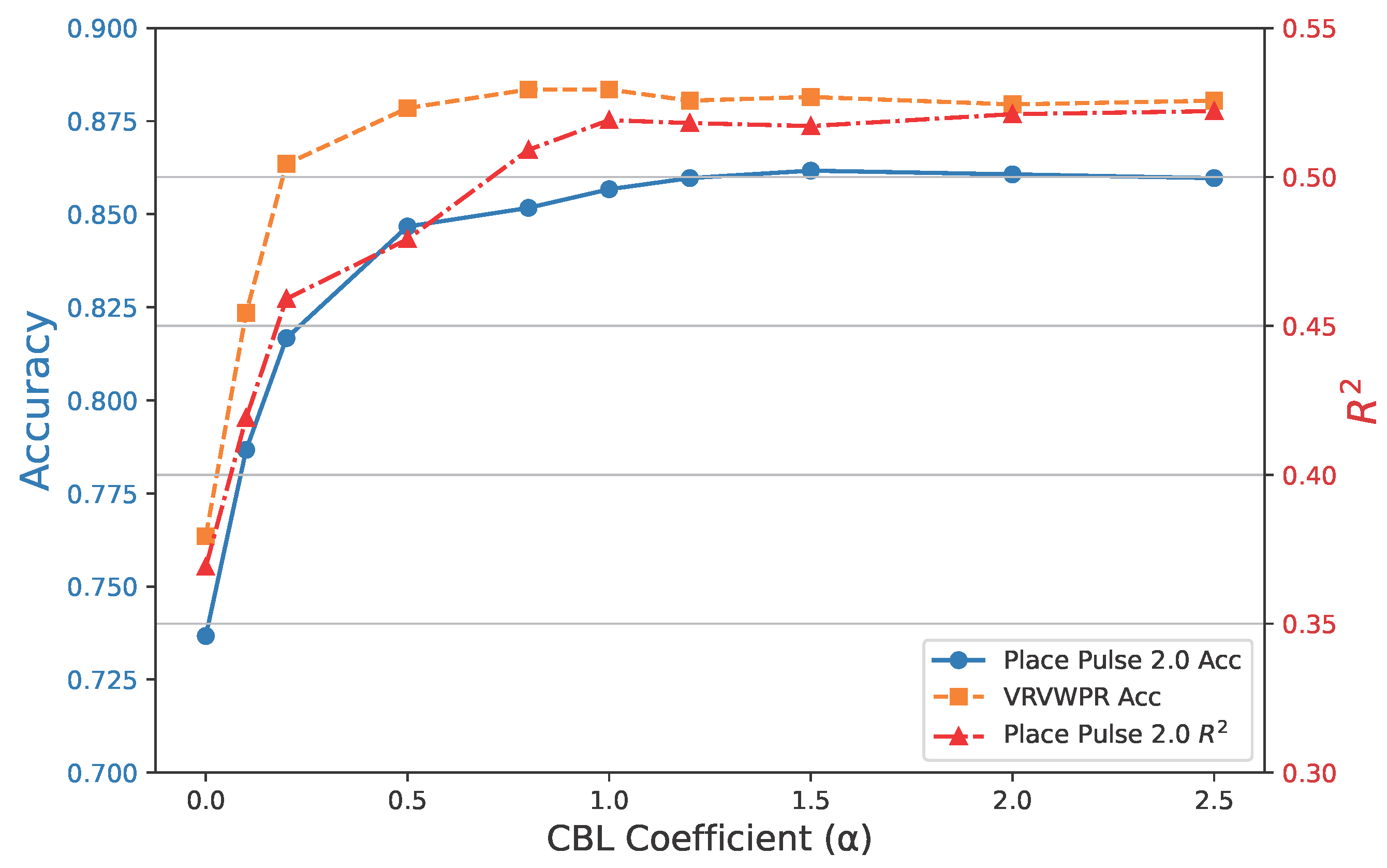

4.5. Ablation Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Advantages and Potential Application of the Proposed Method

5.2. Limitations and Future Work

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qiu, W.; Li, W.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Huang, X. Subjective and objective measures of streetscape perceptions: Relationships with property value in Shanghai. Cities 2023, 132, 104037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Han, X.; He, J.; Jung, T. Measuring residents’ perceptions of city streets to inform better street planning through deep learning and space syntax. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2022, 190, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keizer, K.; Lindenberg, S.; Steg, L. The spreading of disorder. science 2008, 322, 1681–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelling, G.L.; Wilson, J.Q.; et al. Broken windows. Atlantic monthly 1982, 249, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Y.; Li, C. Extracting Chinese geographic data from Baidu map API. The Stata Journal 2020, 20, 805–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, R.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Nakashima, Y. Improving facade parsing with vision transformers and line integration. Advanced Engineering Informatics 2024, 60, 102463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Zhang, F.; Loo, B.P.; Ratti, C. Urban visual intelligence: Uncovering hidden city profiles with street view images. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2023, 120, e2220417120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasar, J.L. The evaluative image of the city. Journal of the American Planning Association 1990, 56, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Liang, Z.; Yuan, Z.; Liu, P.; Bie, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, R.; Wang, J.; Guan, Q. A human-machine adversarial scoring framework for urban perception assessment using street-view images. International Journal of Geographical Information Science 2019, 33, 2363–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salesses, M.P. Place Pulse: Measuring the Collaborative Image of the City. Masters thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, 2012.

- Salesses, P.; Schechtner, K.; Hidalgo, C.A. The collaborative image of the city: mapping the inequality of urban perception. PloS one 2013, 8, e68400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awais, M.; Naseer, M.; Khan, S.; Anwer, R.M.; Cholakkal, H.; Shah, M.; Yang, M.H.; Khan, F.S. Foundation Models Defining a New Era in Vision: a Survey and Outlook. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR; 2021; pp. 8748–8763. [Google Scholar]

- Oquab, M.; Darcet, T.; Moutakanni, T.; Vo, H.; Szafraniec, M.; Khalidov, V.; Fernandez, P.; Haziza, D.; Massa, F.; El-Nouby, A.; et al. Dinov2: Learning robust visual features without supervision. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.07193 2023.

- Koh, P.W.; Nguyen, T.; Pierson, E.; et al. Concept Bottleneck Models. ICML 2020.

- Wang, B.; Li, L.; Nakashima, Y.; Nagahara, H. Learning Bottleneck Concepts in Image Classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2023.

- Chen, C.; Li, O.; Tao, D.; Barnett, A.; Rudin, C.; Su, J.K. This looks like that: deep learning for interpretable image recognition. Advances in neural information processing systems 2019, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Shtedritski, A.; Rupprecht, C.; Vedaldi, A. What does clip know about a red circle? visual prompt engineering for vlms. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 11987–11997.

- Benou, N.; Chen, L.; Gao, X. SALF-CBM: Spatially-Aware and Label-Free Concept Bottleneck Models. ICLR 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S.; et al. GPT-4 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.08774 2023.

- Devlin, J. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.04805 2018.

- Zhong, N.; Jiang, X.; Yao, Y. From Detection to Explanation: Integrating Temporal and Spatial Features for Rumor Detection and Explaining Results Using LLMs. Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 82. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.J.; Liu, X.F. Learning Temporal User Features for Repost Prediction with Large Language Models. Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 82. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Yabuki, N.; Fukuda, T. Measuring visual walkability perception using panoramic street view images, virtual reality, and deep learning. Sustainable Cities and Society 2022, 86, 104140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Chang, J.; Qian, Y.; Chen, G.; Chen, J.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Nakashima, Y.; Nagahara, H. DiReCT: Diagnostic Reasoning for Clinical Notes via Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2024, Vol. 37, pp. 74999–75011.

- Brown, T.B. Language models are few-shot learners. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.14165 2020.

- Chen, J.; Wang, B.; Jiang, Z.; Nakashima, Y. Putting People in LLMs’ Shoes: Generating Better Answers via Question Rewriter. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2025, Vol. 39, pp. 23577–23585.

- Liu, J.; Li, L.; Xiang, T.; Wang, B.; Qian, Y. Tcra-llm: Token compression retrieval augmented large language model for inference cost reduction. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.15556 2023.

- Cheng, Y.; Li, L.; Xu, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, Z.; Wang, W.; Yang, Y. Segment and track anything. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.06558 2023.

- Andriiashen, V.; van Liere, R.; van Leeuwen, T.; Batenburg, K.J. Unsupervised foreign object detection based on dual-energy absorptiometry in the food industry. Journal of Imaging 2021, 7, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Gao, M.; Li, Z.; Gao, S.; Wang, F.; Zheng, F. Track anything: Segment anything meets videos. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.11968 2023.

- Zhu, J.; Chen, Z.; Hao, Z.; Chang, S.; Zhang, L.; Wang, D.; Lu, H.; Luo, B.; He, J.Y.; Lan, J.P.; et al. Tracking anything in high quality. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.13974 2023.

- Park, W.; Choi, Y.; Mekala, M.S.; SangChoi, G.; Yoo, K.Y.; Jung, H.y. A latency-efficient integration of channel attention for ConvNets. Computers, materials and continua 2025, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, C. YOLO-LFD: A Lightweight and Fast Model for Forest Fire Detection. Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 82. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Liu, D. Customized segment anything model for medical image segmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.13785 2023.

- Chen, T.; Mai, Z.; Li, R.; Chao, W.l. Segment anything model (sam) enhanced pseudo labels for weakly supervised semantic segmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.05803 2023.

- Myers, J.; Najafian, K.; Maleki, F.; Ovens, K. Efficient Wheat Head Segmentation with Minimal Annotation: A Generative Approach. Journal of Imaging 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boston, T.; Van Dijk, A.; Thackway, R. U-Net Convolutional Neural Network for Mapping Natural Vegetation and Forest Types from Landsat Imagery in Southeastern Australia. Journal of Imaging 2024, 10, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwenda, C.; Gwetu, M.; Fonou-Dombeu, J.V. Hybridizing Deep Neural Networks and Machine Learning Models for Aerial Satellite Forest Image Segmentation. Journal of Imaging 2024, 10, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, H.; Park, H.; Jung, H.S.; Lee, K. Enhancing Building Facade Image Segmentation via Object-Wise Processing and Cascade U-Net. Computers, Materials & Continua 2024, 81. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Q.; Yang, X.; Wang, X. Anything-3d: Towards single-view anything reconstruction in the wild. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.10261 2023.

- He, K.; Chen, X.; Xie, S.; Li, Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Masked autoencoders are scalable vision learners. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2022, pp. 16000–16009.

- Zhang, J.; Wang, B.; Li, L.; Nakashima, Y.; Nagahara, H. Instruct me more! random prompting for visual in-context learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, 2024, pp. 2597–2606.

- Yan, Y.; Wen, H.; Zhong, S.; Chen, W.; Chen, H.; Wen, Q.; Zimmermann, R.; Liang, Y. Urbanclip: Learning text-enhanced urban region profiling with contrastive language-image pretraining from the web. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2024, 2024, pp. 4006–4017. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, X.; Chen, W.; Yan, Y.; Zhong, S.; Wang, K.; Wen, Q.; Liang, Y. UrbanVLP: Multi-granularity vision-language pretraining for urban socioeconomic indicator prediction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2025, Vol. 39, pp. 28061–28069.

- Yang, J.; Ding, R.; Brown, E.; Qi, X.; Xie, S. V-irl: Grounding virtual intelligence in real life. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer, 2024, pp. 36–55.

- Naik, N.; Philipoom, J.; Raskar, R.; Hidalgo, C. Streetscore-predicting the perceived safety of one million streetscapes. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition workshops, 2014, pp. 779–785.

- Naik, N.; Raskar, R.; Hidalgo, C.A. Cities are physical too: Using computer vision to measure the quality and impact of urban appearance. American Economic Review 2016, 106, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griew, P.; Hillsdon, M.; Foster, C.; Coombes, E.; Jones, A.; Wilkinson, P. Developing and testing a street audit tool using Google Street View to measure environmental supportiveness for physical activity. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2013, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halpern, D. Mental health and the built environment: more than bricks and mortar?; Routledge, 2014.

- Wang, B.; Li, L.; Verma, M.; Nakashima, Y.; Kawasaki, R.; Nagahara, H. Match them up: visually explainable few-shot image classification. Applied Intelligence 2023, 53, 10956–10977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Melis, D.; Jaakkola, T. Robust and interpretable models via probabilistic modeling of sparse structures. In Proceedings of the ICML, 2018.

- Ghorbani, A.; Wexler, J.; Zou, J.; Kim, B. Towards Automatic Concept-based Explanations. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, S.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Q. Robust Concept-based Interpretability with Variational Concept Embedding. NeurIPS 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Li, L.; Verma, M.; Nakashima, Y.; Kawasaki, R.; Nagahara, H. MTUNet: Few-shot Image Classification with Visual Explanations. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshop, 2021.

- Laugel, T.; Lesot, M.J.; Marsala, C.; et al. The Dangers of Post-hoc Interpretability: Unjustified Counterfactual Explanations. In Proceedings of the IJCAI, 2019.

- Zhang, Q.; Zhu, Y.N. Visual Interpretability for Deep Learning: A Survey. In Proceedings of the Frontiers of Information Technology & Electronic Engineering; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. Decoupled weight decay regularization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1711.05101 2017.

- Zhou, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zuo, H.; Chen, W. Ranking Enhanced Supervised Contrastive Learning for Regression. In Proceedings of the Advances in Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; 2024; pp. 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, W.; Li, X.; Chiu, W.H.K.; Kuo, M.D.; Cheng, K.T. Adaptive contrast for image regression in computer-aided disease assessment. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2021, 41, 1255–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Li, X.; Cheng, K.T. Semi-supervised deep regression with uncertainty consistency and variational model ensembling via bayesian neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2023, Vol. 37, pp. 7304–7313.

- Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Fukuda, T.; Wang, B. Revolutionizing urban safety perception assessments: Integrating multimodal large language models with street view images. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.19719 2024.

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 770–778.

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, 2021.

- Alvarez Melis, D.; Jaakkola, T. Towards robust interpretability with self-explaining neural networks. Advances in neural information processing systems 2018, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Yuksekgonul, M.; Wang, M.; Zou, J. Post-hoc concept bottleneck models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.15480 2022.

- Oikarinen, T.; Das, S.; Nguyen, L.M.; Weng, T.W. Label-free concept bottleneck models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.06129 2023.

| Prompt | Content |

|---|---|

| Prompt 1 | List the most important visual features that influence a person’s perception of urban {requirement} in street view images. |

| Prompt 2 | What visual elements in a city scene make people feel {requirement}? |

| Prompt 3 | List common objects, layouts, or attributes visible in urban street-view images that could impact how people feel about the place. |

| Dataset | Number of Concepts | Example Concepts |

|---|---|---|

| Place Pulse 2.0 [10] | 317 | Trees, Sidewalks, Pedestrians, Streetlights, Clean roads, Car, |

| Trash, Construction site, Graffiti, Old houses, Road, ... | ||

| VRVWPR [24] | 195 | People, Bicycles, Crosswalk, Bike Lane, Traffic Light, Shop, |

| Empty roads, Dirt land, Wall, Billboard, Bus, ... |

| Method | Safe | Lively | Beautiful | Wealthy | Boring | Depressing | ||||||

| Acc. | Acc. | Acc. | Acc. | Acc. | Acc. | |||||||

| RN-50 [63] | .8120 | .4551 | .7289 | .3522 | .8443 | .5090 | .6937 | .3227 | .6451 | .2789 | .6720 | .3136 |

| RN-101 [63] | .8605 | .5182 | .7778 | .4174 | .8912 | .5783 | .7482 | .3921 | .6958 | .3386 | .7225 | .3784 |

| ViT-S [64] | .8473 | .4989 | .7831 | .4292 | .8576 | .5374 | .7344 | .3740 | .7042 | .3417 | .7103 | .3599 |

| ViT-B [64] | .8695 | .5381 | .7967 | .4352 | .8732 | .5479 | .7521 | .3996 | .7603 | .4113 | .7294 | .3832 |

| Streetscore [47] | .8120 | .4510 | .7290 | .3510 | .8430 | .5010 | .6920 | .3240 | .6440 | .2770 | .6700 | .3120 |

| UCVME [61] | .8450 | .4920 | .7750 | .4210 | .8590 | .5390 | .7370 | .3760 | .7030 | .3390 | .7090 | .3580 |

| Adaptive Contrast [60] | .7980 | .4420 | .7150 | .3390 | .8320 | .4950 | .6810 | .3080 | .6330 | .2650 | .6600 | .3020 |

| CLIP+KNN [62] | .9060 | .5791 | .8415 | .4796 | .9012 | .5741 | .7867 | .4412 | .7951 | .4456 | .7475 | .4008 |

| RESupCon [59] | .8842 | .5583 | .8155 | .4546 | .8831 | .5580 | .7649 | .4180 | .7724 | .4193 | .7381 | .3939 |

| UP-CBM RN-101 (Ours) | .9150 | .5852 | .8480 | .5012 | .9154 | .5823 | .7845 | .4401 | .8052 | .4587 | .7550 | .4170 |

| UP-CBM ViT-B (Ours) | .9352 | .6038 | .8661 | .5239 | .9487 | .6174 | .7893 | .4483 | .8294 | .4827 | .7718 | .4385 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).