Submitted:

22 May 2025

Posted:

22 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

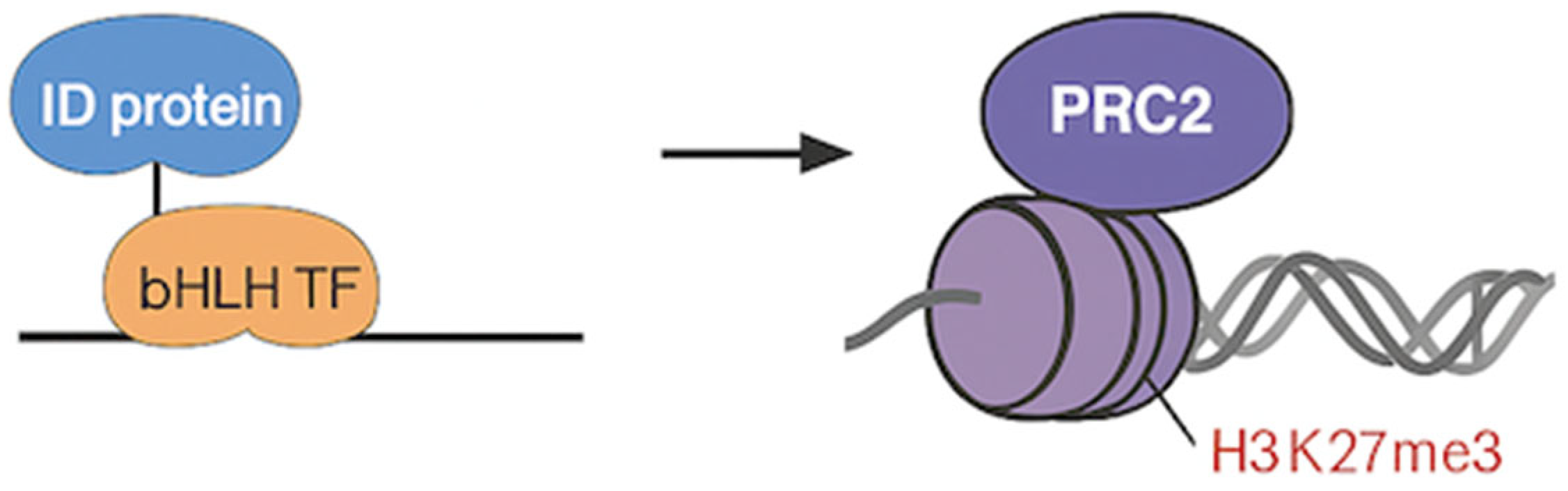

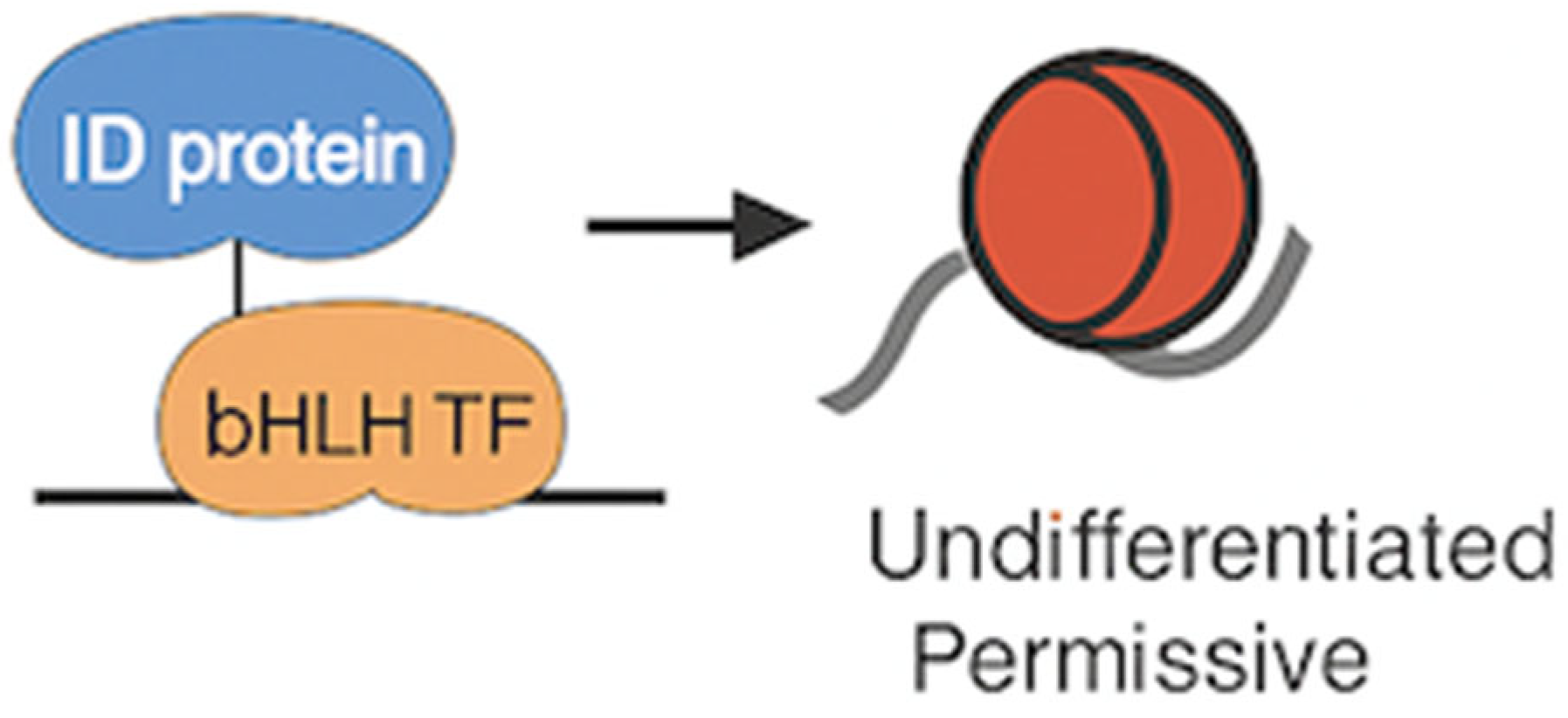

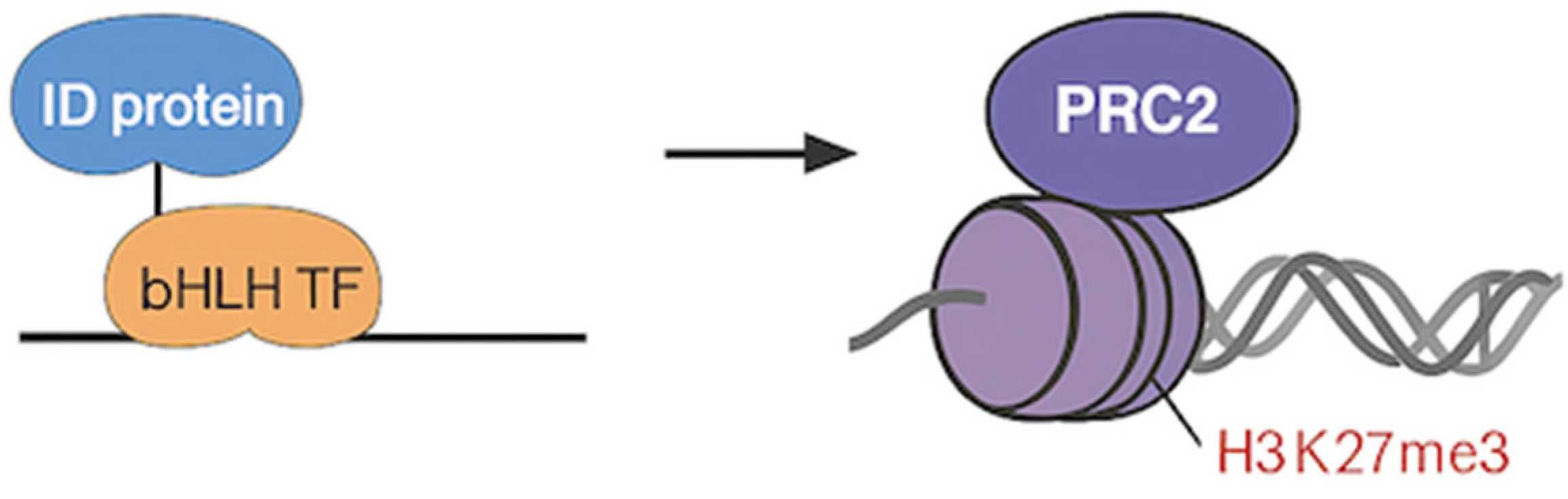

1. ID Proteins Promote an Undifferentiated, Permissive Chromatin State

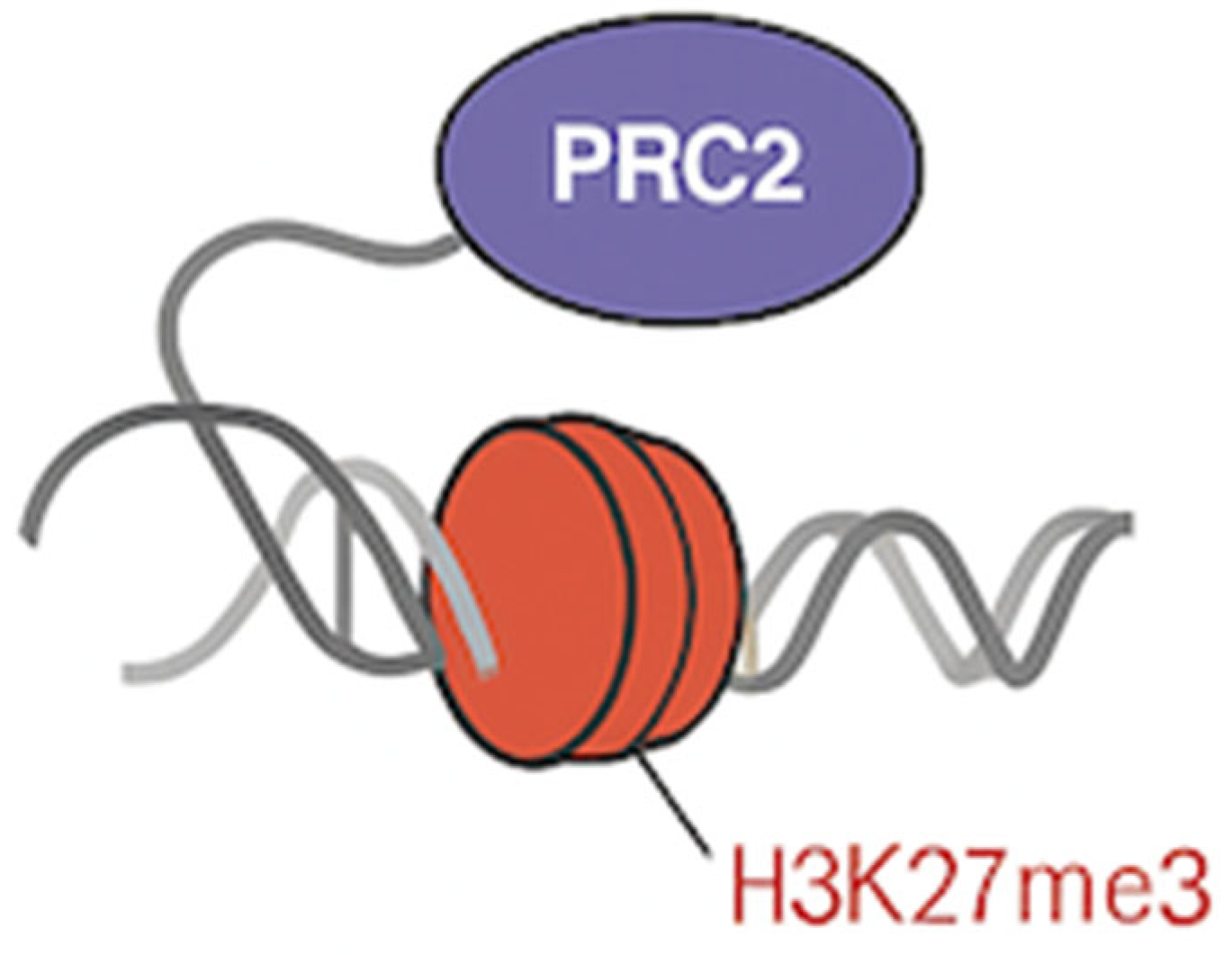

2. PRC2 Requires Pre-patterned Chromatin for Efficient Targeting

3. Co-occurrence in Stem and Cancer Contexts

4. Functional Cross-Talk Between Chromatin Regulators

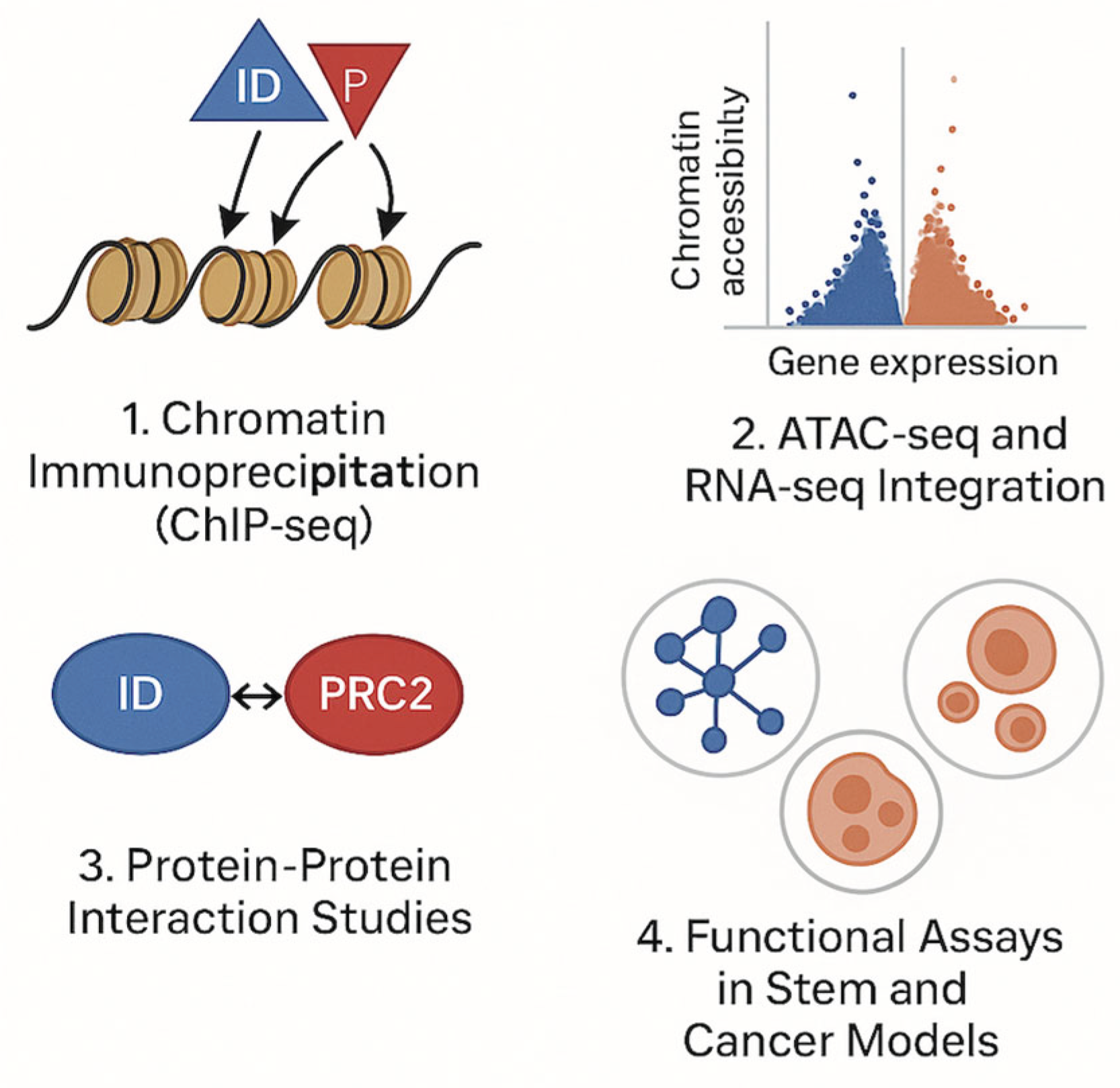

Proposed Experimental Approach:

1. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-seq)

2. Integrated ATAC-seq and RNA-seq Analysis

3. Protein-Protein Interaction Studies

4. Functional Assays in Stem and Cancer Models

Conclusions

Data Availability

Statement of Ethics

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflict of Interest

References

- Norton, J.D. ID helix-loop-helix proteins in cell growth, differentiation and tumorigenesis. J Cell Sci. 2000, 113, 3897–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasorella, A.; et al. Id proteins at the cross-road of development and cancer. Oncogene. 2014, 33, 4659–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avecilla, V. Effect of Transcriptional Regulator ID3 on Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension and Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia. Int J Vasc Med. 2019, 2019, 2123906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ling, F.; et al. Id proteins: small molecules, mighty regulators. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2014, 110, 189–229. [Google Scholar]

- Yokota, Y. Id and development. Oncogene. 2001, 20, 8290–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzinova, M.B.; Benezra, R. Id proteins in development, cell cycle and cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 2003, 13, 410–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankovic, V.; et al. Id1 restrains myeloid commitment, maintaining the self-renewal capacity of hematopoietic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007, 104, 12682–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niola, F.; et al. Id proteins synchronize stemness and anchorage to the niche of neural stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2012, 14, 477–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perk, J.; et al. Id family of helix-loop-helix proteins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005, 5, 603–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anido, J.; et al. TGF-beta Receptor Inhibitors Target the CD44(high)/Id1(high) Glioma-Initiating Cell Population in Human Glioblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2010, 18, 655–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.H.; et al. The role of ID1 in cancer progression and therapy resistance. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020, 8:186.

- Avecilla, V.; Doke, M.; Das, M.; Alcazar, O.; Appunni, S.; Rech Tondin, A.; Watts, B.; Ramamoorthy, V.; Rubens, M.; Das, J.K. Integrative Bioinformatics-Gene Network Approach Reveals Linkage between Estrogenic Endocrine Disruptors and Vascular Remodeling in Peripheral Arterial Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 4502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Avecilla, V.; Doke, M.; Appunni, S.; Rubens, M.; Ramamoorthy, V.; Das, J.K. Pathophysiological Features of Remodeling in Vascular Diseases: Impact of Inhibitor of DNA-Binding/Differentiation-3 and Estrogenic Endocrine Disruptors. Med Sci (Basel). 13, 2. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Avecilla, V. Microarray Analysis Shows Important ID3 – BMP9 Driven Gene Signatures. Preprints 2025, 2025041283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avecilla, V. Gene Interactions in Cerebral Cavernous Malformations: A Brief Report. Preprints 2024, 2024050746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankic, M.; et al. TGF-β–Id1 signaling opposes Twist1 and promotes metastatic colonization via a mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition. Cell Reports. 2013, 5, 1228–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niola, F.; et al. Id2 mediates tumor initiation, proliferation, and angiogenesis in glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 3611–21. [Google Scholar]

- Benezra, R. The elusive tumor suppressor function of ID proteins. Oncogene. 2014, 33, 5564–5. [Google Scholar]

- Margueron, R.; Reinberg, D. The Polycomb complex PRC2 and its mark in life. Nature. 2011, 469, 343–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuettengruber, B.; et al. Genome regulation by Polycomb and Trithorax proteins. Cell. 2007, 128, 735–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.; Zhang, Y. SUZ12 is required for both the histone methyltransferase activity and the silencing function of the EED-EZH2 complex. Mol Cell. 2004, 15, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, L.A.; et al. Polycomb complexes repress developmental regulators in murine embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2006, 441, 349–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.I.; et al. Control of developmental regulators by Polycomb in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2006, 125, 301–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Roberts, C.W. Targeting EZH2 in cancer. Nat Med. 2016, 22, 128–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, R.D.; et al. Somatic mutations altering EZH2 (Tyr641) in follicular and diffuse large B-cell lymphomas of germinal-center origin. Nat Genet. 2010, 42, 181–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.; et al. Epigenetic regulation of cancer progression by EZH2: from biological insights to therapeutic potential. Biomark Res. 2018, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; et al. ID1 cooperates with oncogenic Ras to inhibit senescence in primary murine fibroblasts by antagonizing p16INK4a expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2004, 24, 2570–82. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, D.A.; et al. Single-cell analysis reveals a stem-cell program in human metastatic breast cancer cells. Nature. 2015, 526, 131–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksuz, O.; et al. Capturing the onset of PRC2-mediated repressive domain formation. Mol Cell. 2018, 70, 1149–1162e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; et al. Molecular analysis of PRC2 recruitment to DNA in chromatin and its inhibition by RNA. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2017, 24, 1028–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendenhall, E.M.; et al. GC-rich sequence elements recruit PRC2 in mammalian ES cells. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6(12)\:e1001244.

- Wilson, B.G.; Roberts, C.W. SWI/SNF nucleosome remodellers and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011, 11, 481–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadoch, C.; et al. Dynamics of BAF–Polycomb complex opposition on heterochromatin in normal and malignant pediatric brain tumors. Cell. 2017, 171, 216–229e19. [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien, C.A.; et al. The E2A gene is required for normal B-cell development and suppresses alternative lineage development. Immunity. 2004, 20, 349–60. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; et al. Chromatin accessibility dynamics reveal novel functional enhancers in response to IL-4 stimulation in macrophages. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, e27. [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko, S.; et al. Interactions between JARID2 and noncoding RNAs regulate PRC2 recruitment to chromatin. Mol Cell. 2014, 53, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riising, E.M.; et al. Gene silencing triggers Polycomb repressive complex 2 recruitment to CpG islands genome wide. Mol Cell. 2014, 55, 347–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Y.B.; Pirrotta, V. Polycomb complexes and epigenetic states. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008, 20, 266–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, R.; et al. NeuroD1 coordinates chromatin remodeling and transcription factor recruitment to regulate differentiation of granule cells. Sci Rep. 2017, 7, 6136. [Google Scholar]

- Maves, L.; et al. The BAF complex interacts with Pax7 in myogenic progenitors. Development. 2007, 134, 859–69. [Google Scholar]

- Hnisz, D.; et al. Transcriptional super-enhancers are linked to cell identity and disease. Cell. 2013, 155, 934–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; et al. Histone demethylase KDM6B regulates the timing of neural differentiation in human ESCs. Cell Stem Cell. 2015, 16, 249–60. [Google Scholar]

- Pasini, D.; et al. Coordinated regulation of transcriptional repression by the RBP2 H3K4 demethylase and Polycomb Repressive Complex 2. Genes Dev. 2008, 22, 1345–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buenrostro, J.D.; et al. Transposition of native chromatin for fast and sensitive epigenomic profiling of open chromatin. Nat Methods. 2013, 10, 1213–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lareau, C.A.; et al. Chromatin accessibility dynamics reveal novel functional enhancers in response to hypoxia. Mol Cell. 2019, 75, 865–878e8. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.I.; et al. Probing nuclear pore complex architecture with proximity-dependent biotinylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014, 111, E2453–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackledge, N.P.; et al. PRC1 catalyzes monoubiquitylation of histone H2A to promote H3K27 methylation by PRC2. Mol Cell. 2014, 53, 644–57. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe, M.T.; et al. EZH2 inhibition as a therapeutic strategy for lymphoma with EZH2-activating mutations. Nature. 2012, 492, 108–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvà, M.L.; et al. Reconstructing and reprogramming the tumor-propagating potential of glioblastoma stem-like cells. Cell. 2014, 157, 580–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).