Submitted:

21 May 2025

Posted:

22 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

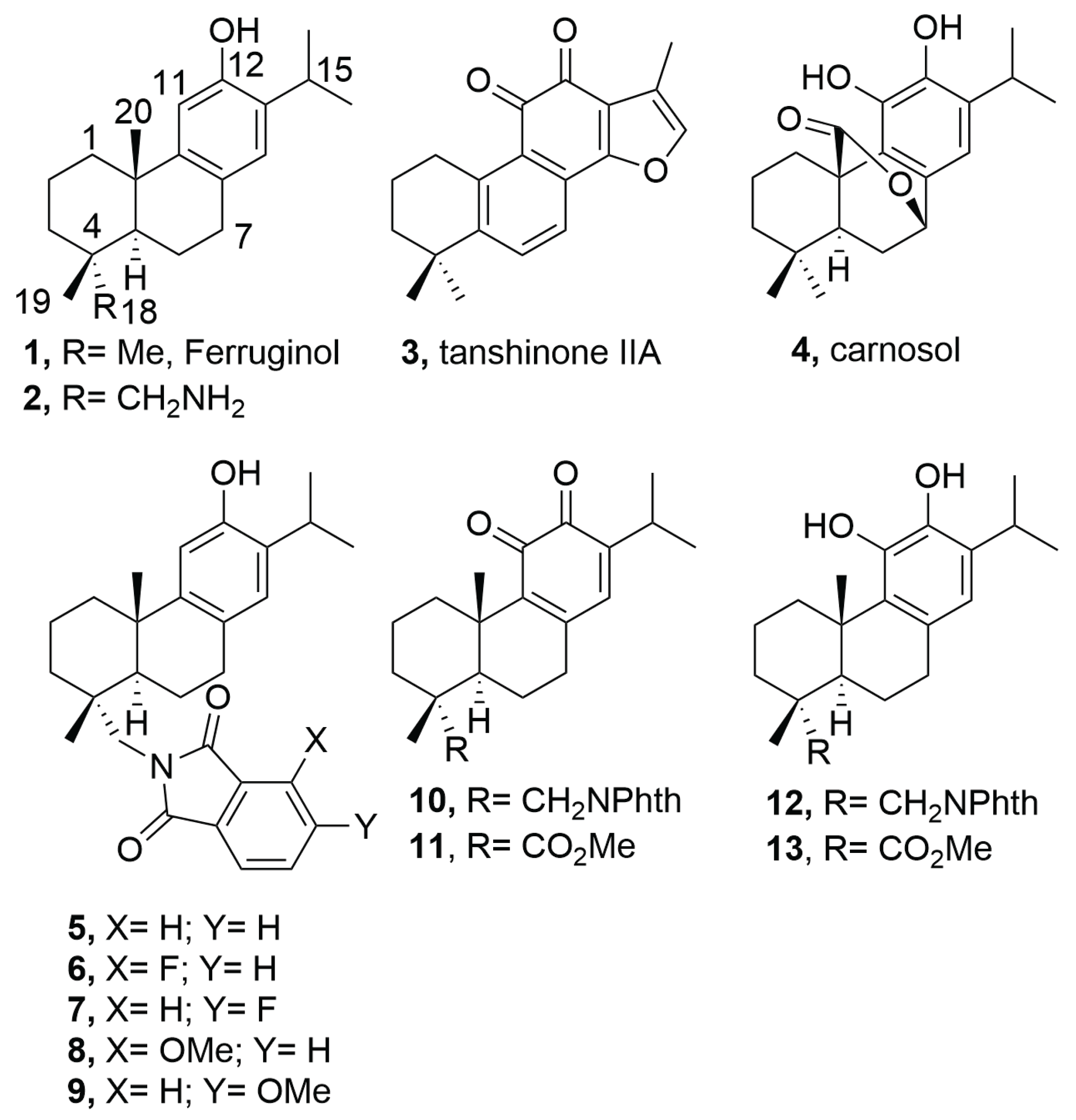

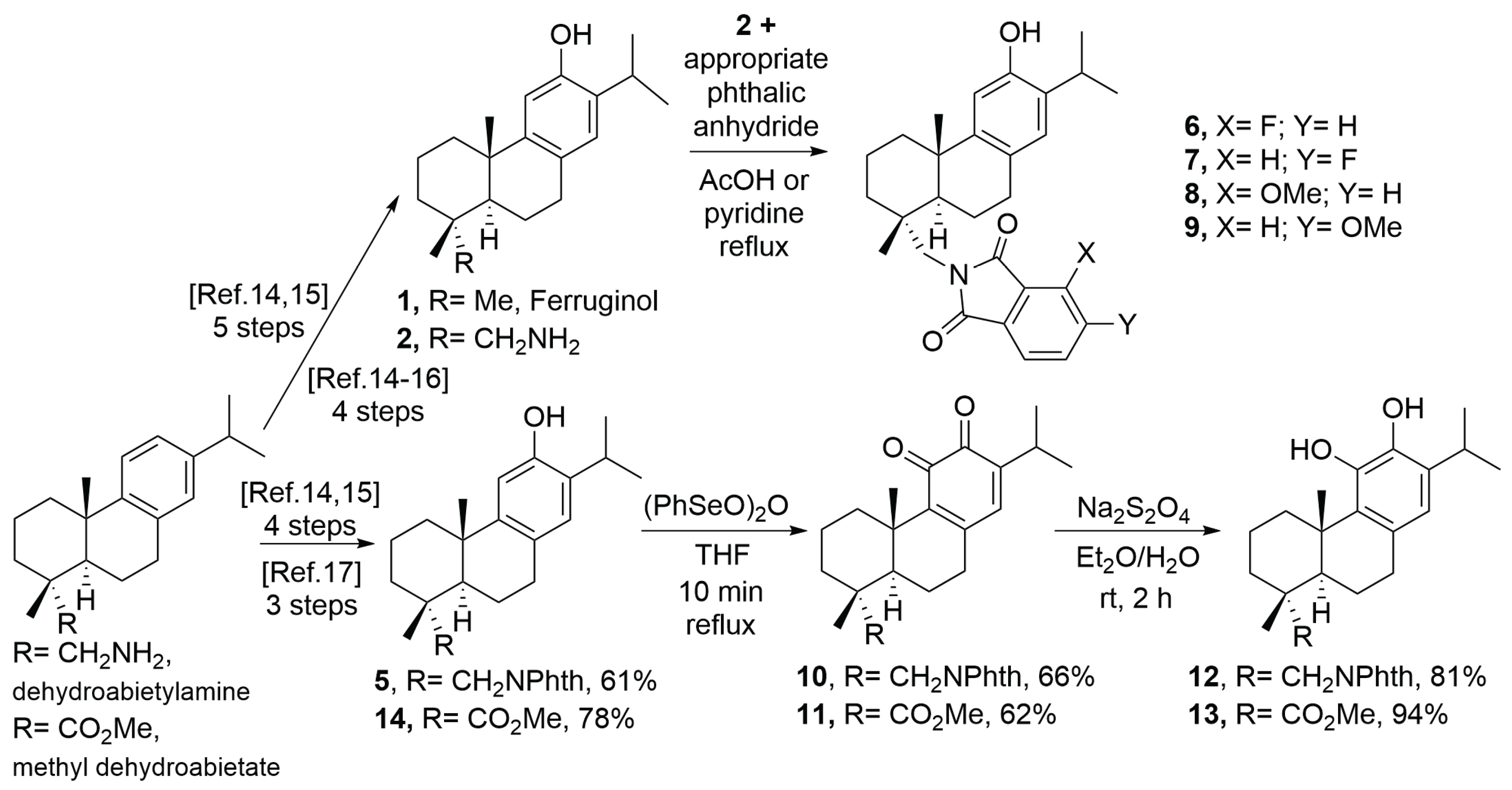

2.1. Chemistry

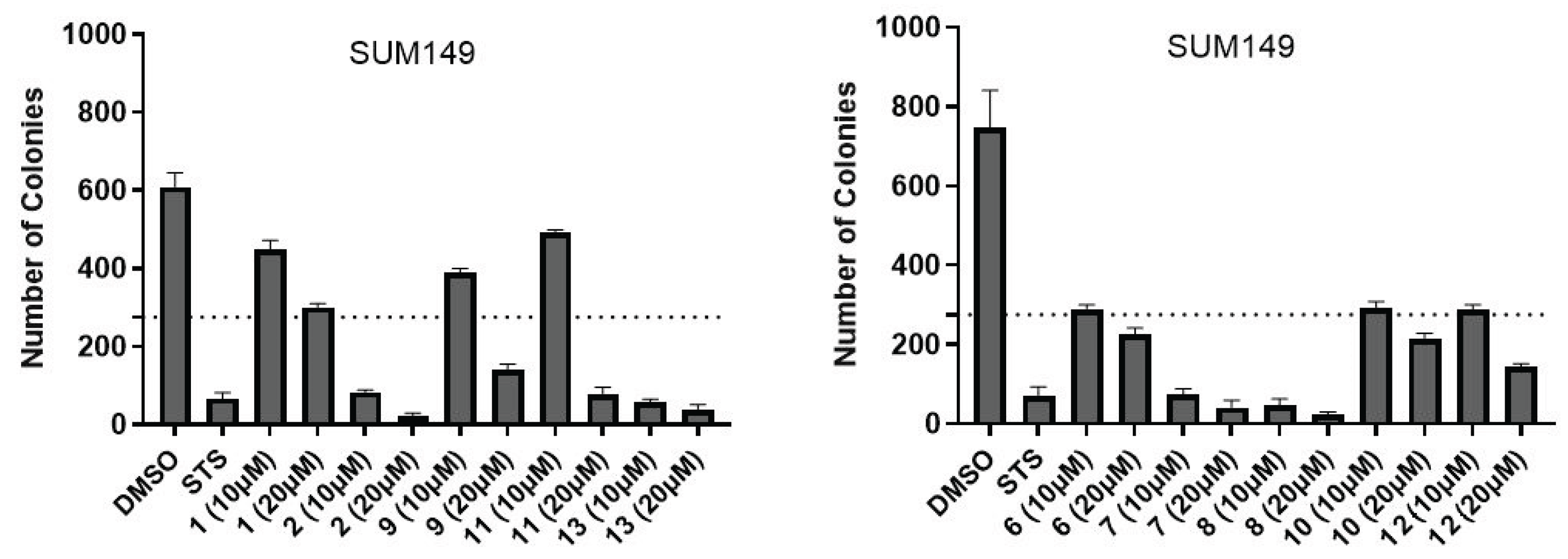

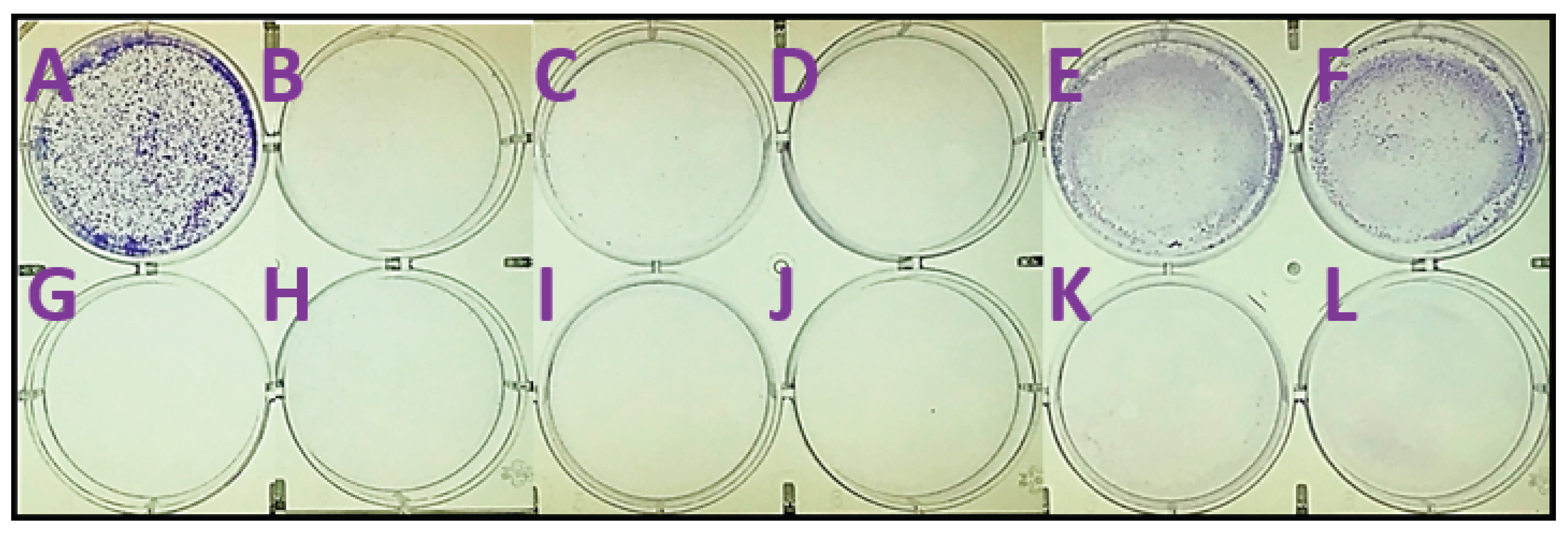

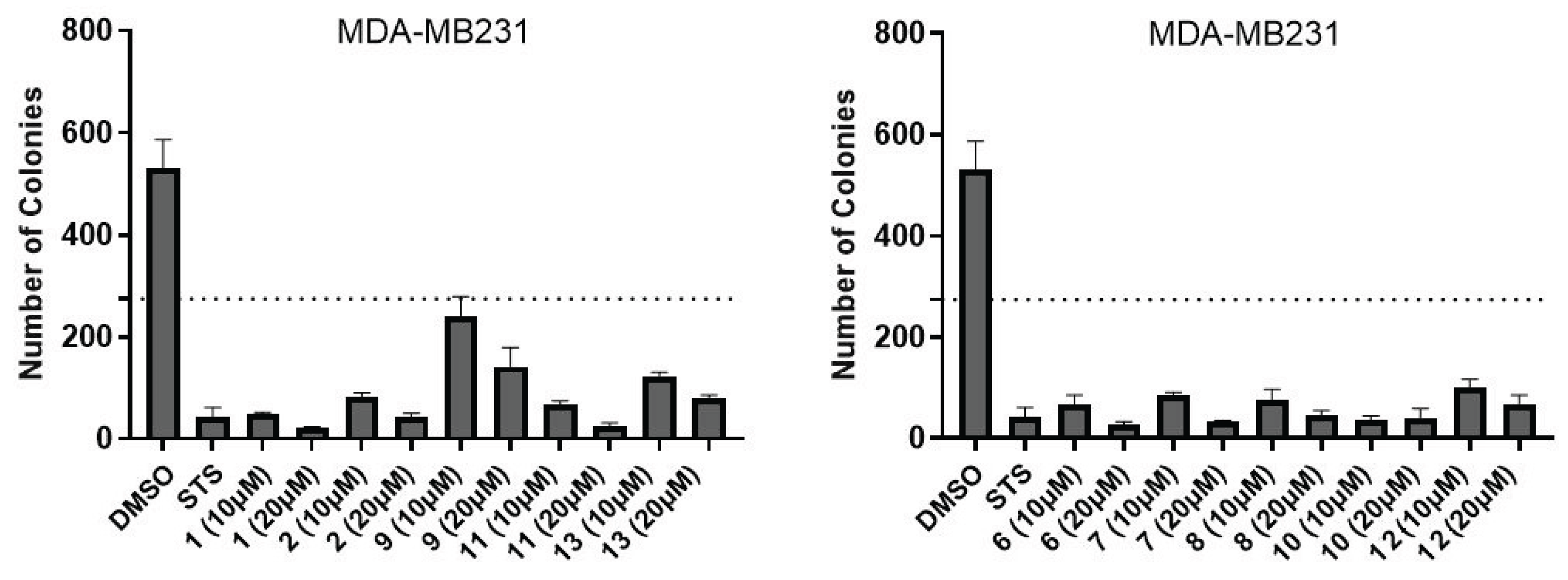

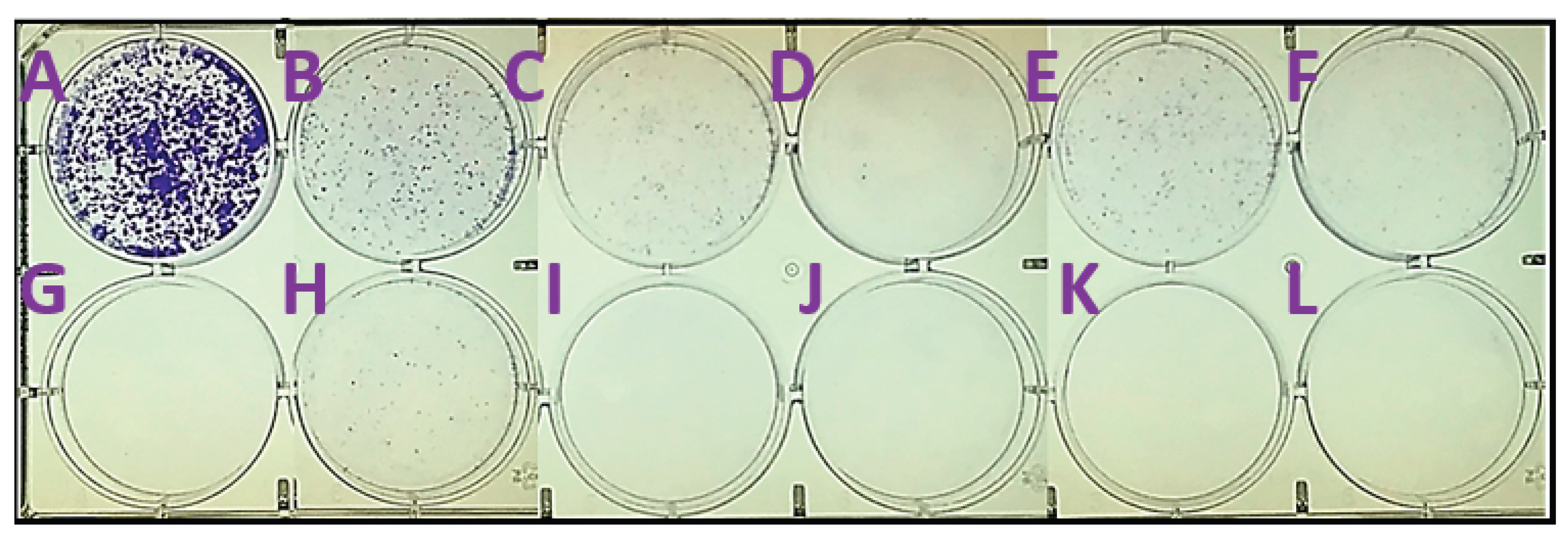

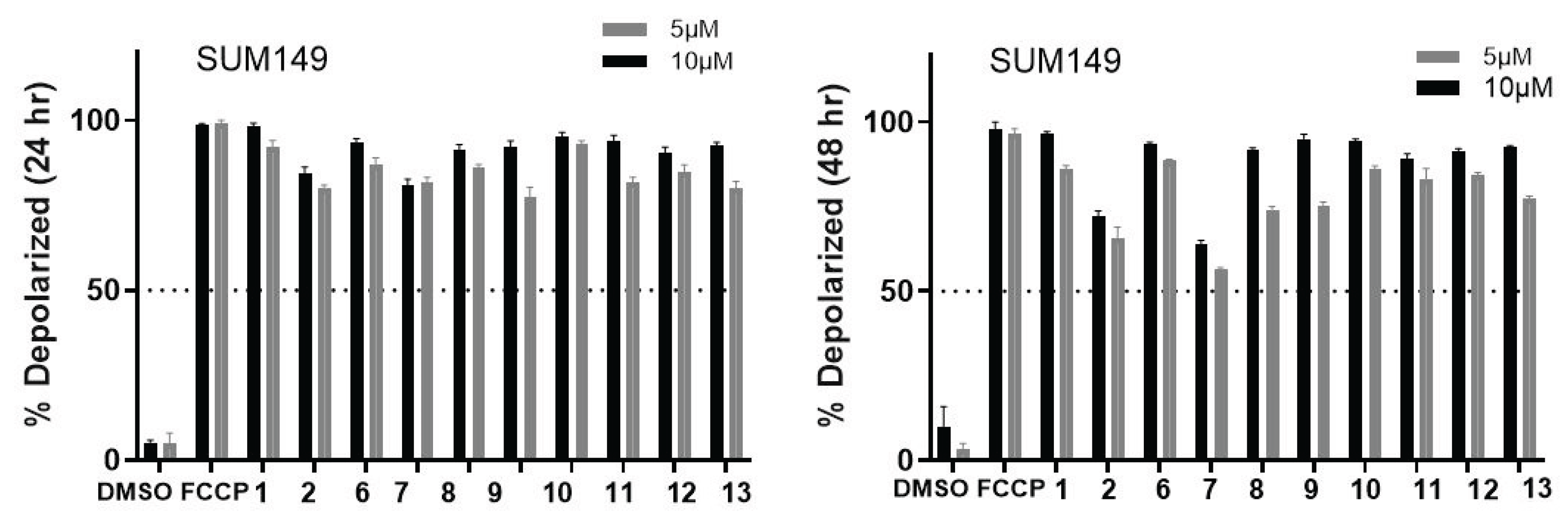

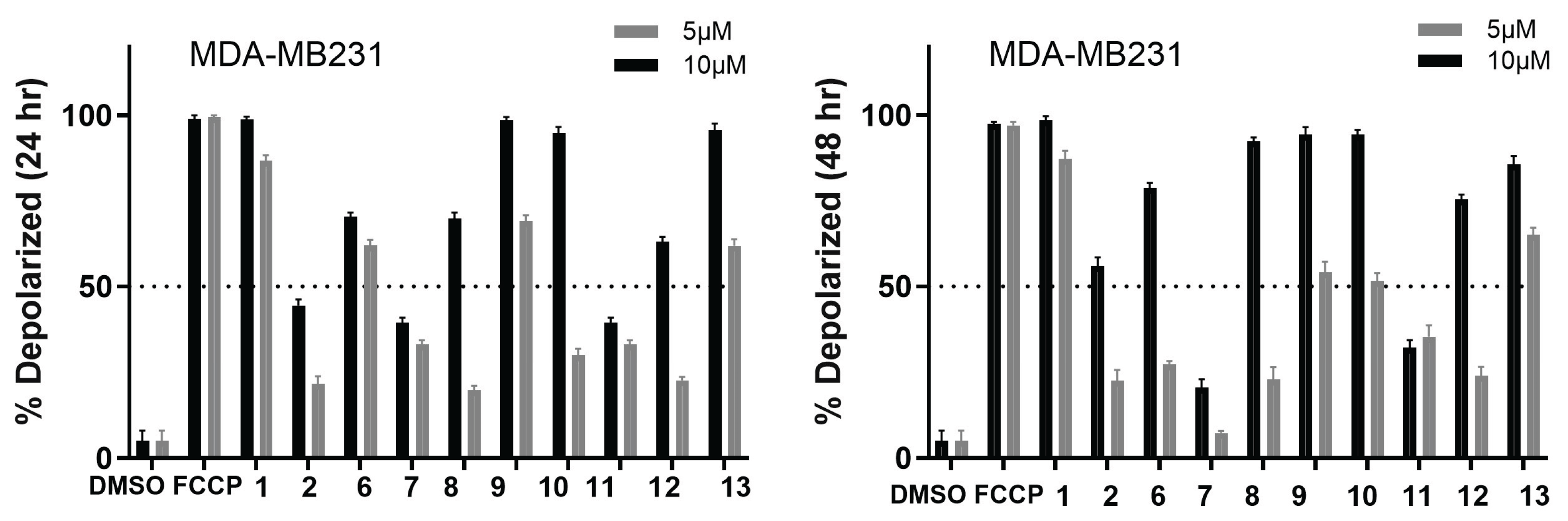

2.2. Biology

2.3. In Silico Calculations

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemistry: General Experimental Procedures

4.2. Synthesis

4.3. Cells

4.4. Cell Viabiliy (CellTiterGlo) Assay

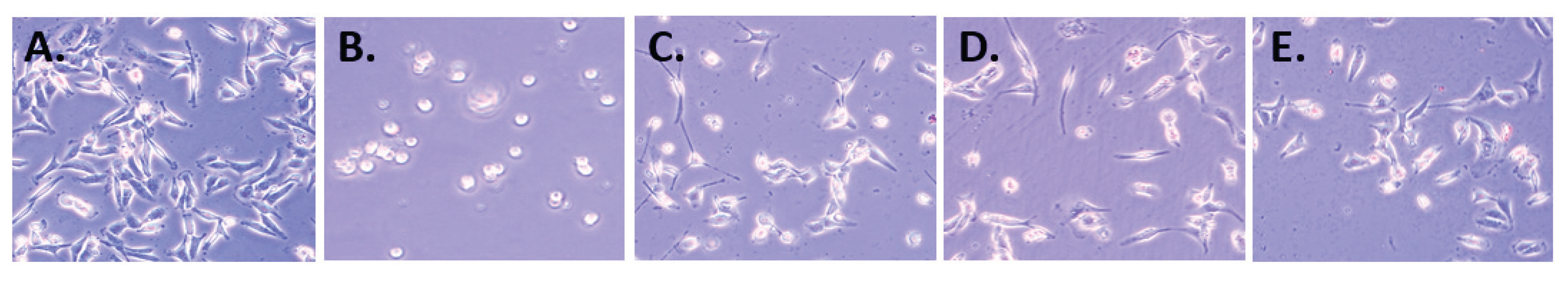

4.5. Cell Morphology

4.6. Colony Formation Assay

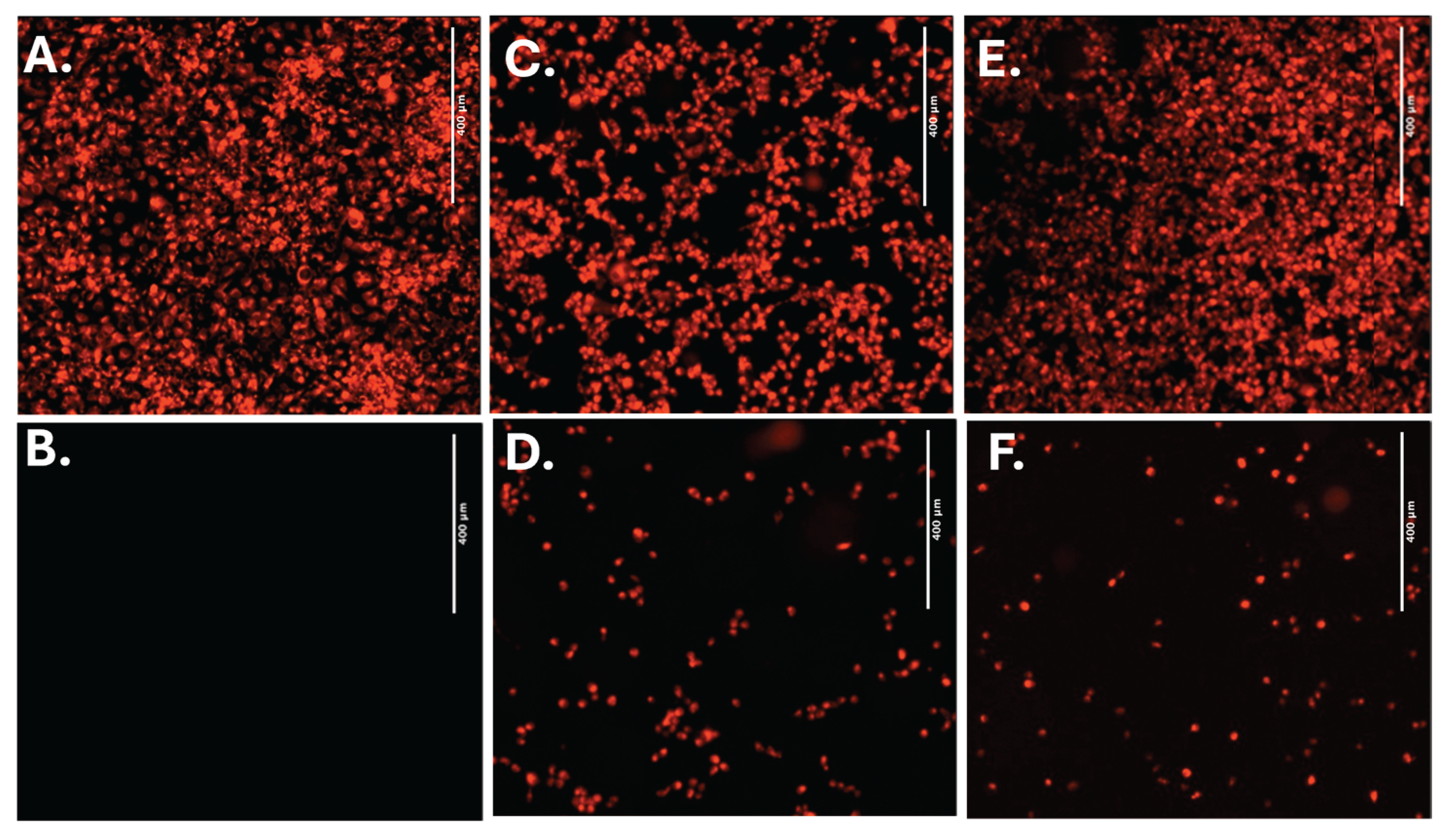

4.7. Tetramethylrhodamine Methyl Ester Perchlorate (TMRM) Assay

4.8. Statistical Analysis

4.9. ADMET and Drug-Likeness Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guida, F.; Kidman, R.; Ferlay, J.; et al. Global and regional estimates of orphans attributed to maternal cancer mortality in 2020. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 2563–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vagia, E.; Mahalingam, D.; Cristofanilli, M. The Landscape of Targeted Therapies in TNBC. Cancers 2020, 12, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D. J.; Cragg, G. M. Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs over the Nearly Four Decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 770–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargazifar, Z.; Charami, D.G.; Kashi, M.E.; Asili, J.; Shakeri, A. Abietane-Type Diterpenoids: Insights into Structural Diversity and Therapeutic Potential. Chem. Biodiversity 2024, 21, e202400808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, M.A. Aromatic abietane diterpenoids: their biological activity and synthesis. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2015, 32, 684–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, B.; Tian, C.; Tang, J.-X.; Dumbuya, J.S.; Li, W.; Lu, J. Anticancer activities of natural abietic acid. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1392203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.W.C.; Wong, S.K.; Chan, H.T. Ferruginol and Sugiol: A Short Review of their Chemistry, Sources, Contents, Pharmacological Properties and Patents. Trop. J. Nat. Prod. Res. TJNPR 2023, 7, 2325–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; González-Cardenete, M.A.; Prieto-Garcia, J.M. In Vitro Cytotoxic Effects of Ferruginol Analogues in Sk-MEL28 Human Melanoma Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrokhi, H.; Asili, J.; Tayarani-najaran, Z.; Boozari, M. Signaling pathways behind the biological effects of tanshinone IIA for the prevention of cancer and cardiovascular diseases. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsamri, H.; Al Dhaheri, Y.; Iratni, R. Targeting Triple-Negative Breast Cancer by the Phytopolyphenol Carnosol: ROS-Dependent Mechanisms. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroemer, G.; Pouyssegur, J. Tumor cell metabolism: cancer’s Achilles’ heel. Cancer Cell 2008, 13, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Cardenete, M.A.; González-Zapata, N.; Boyd, L.; Rivas, F. Discovery of Novel Bioactive Tanshinones and Carnosol Analogues against Breast Cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, M. A.; Pérez-Guaita, D. Short syntheses of (+)-ferruginol from (+)-dehydroabietylamine. Tetrahedron 2012, 68, 9612–9615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Cardenete, M.A.; Hamulić, D.; Miquel-Leal, F.J.; González-Zapata, N.; Jimenez-Jarava, O.J.; Brand, Y.M.; Restrepo-Mendez, L.C.; Martinez-Gutierrez, M.; Betancur-Galvis, L.A.; Marín, M.L. Antiviral Profiling of C-18- or C-19-Functionalized Semisynthetic Abietane Diterpenoids. J. Nat. Prod. 2022, 85, 2044–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varbanov, M.; Philippot, S.; González-Cardenete, M.A. Anticoronavirus Evaluation of Antimicrobial Diterpenoids: Application of New Ferruginol Analogues. Viruses 2023, 15, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamulić, D.; Stadler, M.; Hering, S.; Padrón, J.M.; Bassett, R.; Rivas, F.; Loza-Mejía, M.A.; Dea-Ayuela, M.A.; González-Cardenete, M.A. Synthesis and Biological Studies of (+)-Liquiditerpenoic Acid A (Abietopinoic Acid) and Representative Analogues: SAR Studies. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riss, T.L.; Moravec, R.A.; Niles, A.L., et al. Cell Viability Assays. 2013 May 1 [Updated 2016 Jul 1]. In: Markossian S, Grossman A, Baskir H, et al., editors. Assay Guidance Manual [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; 2004-. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK144065/.

- Ling, T.; Lang, W. H.; Craig, J.; Potts, M. B.; Budhraja, A.; Opferman, J.; Bollinger, J.; Maier, J.; Marsico, T. D.; Rivas, F. Studies of Jatrogossone A as a Reactive Oxygen Species Inducer in Cancer Cellular Models. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 1301–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, T.; Lang, W.H.; Maier, J.; Quintana Centurion, M.; Rivas, F. Cytostatic and Cytotoxic Natural Products against Cancer Cell Models. Molecules 2019, 24, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, C. A.; Lombardo, F.; Dominy, B.W.; Feeney, P. J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1997, 23, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigante, B.; Santos, C.; Silva, A. M.; Curto, M. J. M.; Nascimento, M. S. J.; et al. Catechols from Abietic acid: synthesis and evaluation as bioactive compounds. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2003, 11, 1631–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyajima, Y.; Saito, Y.; Takeya, M.; Goto, M.; Nakagawa-Goto, K. Synthesis of 4-epi-parviflorons A, C, and E: structure-activity relationship study of antiproliferative abietane derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 3239–3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hay, R.J.; Caputo, J.L.; Macy, M.L. ATCC Quality Control Methods for Cell Lines, 2nd ed.; ATCC: Manassas, VA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- González, M. A. Synthetic derivatives of aromatic abietane diterpenoids and their biological activities. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 87, 834–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniuk, O.; Maranha, A.; Salvador, J.A.R.; Empadinhas, N.; Moreira, V.M. Bi- and tricyclic diterpenoids: Landmarks from a decade (2013–2023) in search of leads against infectious diseases. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2024, 21, 1858–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Le, T.Q.; Oh, C.H. Recent Advances in Abietane/Icetexane Synthesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 2022, 108, 154133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roa-Linares, V.C.; Betancur-Galvis, L.A.; González-Cardenete, M.A.; Garcia-Blanco, M.A.; Gallego-Gomez, J.C. Broad-spectrum antiviral ferruginol analog affects the viral proteins translation and actin remodeling during dengue virus infection. Antiviral Research 2025, 237, 106139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisio, A.; Pedrelli, F.; D’Ambola, M.; Labanca, F.; Schito, A.M.; Govaerts, R.; De Tommasi, N. Quinone diterpenes from Salvia species: chemistry, botany, and biological activity. Phytochem. Rev. 2019, 18, 665–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait El Had, M.; Zentar, H.; Ruiz-Muñoz, B.; Sainz, J.; Guardia, J.J.; Fernández, A.; Justicia, J.; Alvarez-Manzaneda, E.; Reyes-Zurita, F.J.; Chahboun, R. Evaluation of Anticancer and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Some Synthetic Rearranged Abietanes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound | SUM149 | TI | MDA-MB231 | TI | MCF07 | TI | BJ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1b | >50 | >1 | 8.3 ± 1.4 | >6 | 19.0 ± 1.5 | >3 | >50 |

| 2b | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 17 | 5.1 ± 0.6 | 15 | 10.0 ± 1.5 | 7 | 75.0 ± 6.2 |

| 5b | 4.4 ± 0.2 | 17 | 8.2 ± 0.5 | 9 | 13.0 ± 0.6 | 6 | 74.8 ± 5.3 |

| 6 | 4.8 ± 0.2 | 13 | 9.4 ± 0.9 | 7 | 5.4 ± 0.6 | 12 | 63.5 ± 6.3 |

| 7 | 4.3 ± 0.1 | >12 | 7.6 ± 0.2 | >7 | 7.0 ± 0.6 | >7 | >50 |

| 8 | 5.3 ± 0.1 | 12 | 54.6 ± 5.0 | ≈1 | 11.0 ± 1.4 | 6 | 61.2 ± 5.4 |

| 9 | 4.3 ± 0.2 | 14 | 8.2 ± 0.8 | 7 | 12.0 ± 1.2 | 5 | 58.9 ± 5.7 |

| 10b | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 24 | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 13 | 2.3 ± 1.1 | 15 | 35.4 ± 5.0 |

| 11b | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 43 | 3.9 ± 0.8 | 15 | 8.3 ± 0.9 | 7 | 56.5 ± 6.1 |

| 12b | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 18 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 12 | 4.6 ± 0.6 | 7 | 32.5 ± 5.0 |

| 13b | >50 | ≈1 | 9.4 ± 0.4 | 6 | >50 | ≈1 | 57.6 ± 3.0 |

| Compound | Consensus Log P | MW | n-HBA | n-HBD | TPSA | Lipinski’s violation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5.50 | 286.45 | 1 | 1 | 20.23 | 1 |

| 2 | 4.65 | 301.47 | 2 | 2 | 46.25 | 0 |

| 3 | 5.37 | 294.34 | 3 | 0 | 47.28 | 1 |

| 4 | 4.05 | 330.42 | 4 | 2 | 66.76 | 0 |

| 5 | 6.00 | 431.57 | 3 | 1 | 57.61 | 1 |

| 6 | 6.42 | 449.56 | 4 | 1 | 57.61 | 1 |

| 7 | 6.42 | 449.56 | 4 | 1 | 57.61 | 1 |

| 8 | 6.08 | 461.59 | 4 | 1 | 66.84 | 1 |

| 9 | 6.08 | 461.59 | 4 | 1 | 66.84 | 1 |

| 10 | 5.51 | 445.55 | 4 | 0 | 71.52 | 1 |

| 11 | 4.48 | 344.44 | 4 | 0 | 60.44 | 0 |

| 12 | 5.52 | 447.57 | 4 | 2 | 77.84 | 1 |

| 13 | 4.50 | 346.46 | 4 | 2 | 66.76 | 0 |

| Rule of five | not >5 | <500 | not >10 | not >5 | 1 violation allowed |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).